Why Poverty Persists in America

A Pulitzer Prize-winning sociologist offers a new explanation for an intractable problem.

A mother and son living in a Walmart parking lot in North Dakota in 2012. Credit... Eugene Richards

Supported by

- Share full article

By Matthew Desmond

- Published March 9, 2023 Updated April 3, 2023

In the past 50 years, scientists have mapped the entire human genome and eradicated smallpox. Here in the United States, infant-mortality rates and deaths from heart disease have fallen by roughly 70 percent, and the average American has gained almost a decade of life. Climate change was recognized as an existential threat. The internet was invented.

On the problem of poverty, though, there has been no real improvement — just a long stasis. As estimated by the federal government’s poverty line, 12.6 percent of the U.S. population was poor in 1970; two decades later, it was 13.5 percent; in 2010, it was 15.1 percent; and in 2019, it was 10.5 percent. To graph the share of Americans living in poverty over the past half-century amounts to drawing a line that resembles gently rolling hills. The line curves slightly up, then slightly down, then back up again over the years, staying steady through Democratic and Republican administrations, rising in recessions and falling in boom years.

What accounts for this lack of progress? It cannot be chalked up to how the poor are counted: Different measures spit out the same embarrassing result. When the government began reporting the Supplemental Poverty Measure in 2011, designed to overcome many of the flaws of the Official Poverty Measure, including not accounting for regional differences in costs of living and government benefits, the United States officially gained three million more poor people. Possible reductions in poverty from counting aid like food stamps and tax benefits were more than offset by recognizing how low-income people were burdened by rising housing and health care costs.

The American poor have access to cheap, mass-produced goods, as every American does. But that doesn’t mean they can access what matters most.

Any fair assessment of poverty must confront the breathtaking march of material progress. But the fact that standards of living have risen across the board doesn’t mean that poverty itself has fallen. Forty years ago, only the rich could afford cellphones. But cellphones have become more affordable over the past few decades, and now most Americans have one, including many poor people. This has led observers like Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill, senior fellows at the Brookings Institution, to assert that “access to certain consumer goods,” like TVs, microwave ovens and cellphones, shows that “the poor are not quite so poor after all.”

No, it doesn’t. You can’t eat a cellphone. A cellphone doesn’t grant you stable housing, affordable medical and dental care or adequate child care. In fact, as things like cellphones have become cheaper, the cost of the most necessary of life’s necessities, like health care and rent, has increased. From 2000 to 2022 in the average American city, the cost of fuel and utilities increased by 115 percent. The American poor, living as they do in the center of global capitalism, have access to cheap, mass-produced goods, as every American does. But that doesn’t mean they can access what matters most. As Michael Harrington put it 60 years ago: “It is much easier in the United States to be decently dressed than it is to be decently housed, fed or doctored.”

Why, then, when it comes to poverty reduction, have we had 50 years of nothing? When I first started looking into this depressing state of affairs, I assumed America’s efforts to reduce poverty had stalled because we stopped trying to solve the problem. I bought into the idea, popular among progressives, that the election of President Ronald Reagan (as well as that of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom) marked the ascendancy of market fundamentalism, or “neoliberalism,” a time when governments cut aid to the poor, lowered taxes and slashed regulations. If American poverty persisted, I thought, it was because we had reduced our spending on the poor. But I was wrong.

Reagan expanded corporate power, deeply cut taxes on the rich and rolled back spending on some antipoverty initiatives, especially in housing. But he was unable to make large-scale, long-term cuts to many of the programs that make up the American welfare state. Throughout Reagan’s eight years as president, antipoverty spending grew, and it continued to grow after he left office. Spending on the nation’s 13 largest means-tested programs — aid reserved for Americans who fall below a certain income level — went from $1,015 a person the year Reagan was elected president to $3,419 a person one year into Donald Trump’s administration, a 237 percent increase.

Most of this increase was due to health care spending, and Medicaid in particular. But even if we exclude Medicaid from the calculation, we find that federal investments in means-tested programs increased by 130 percent from 1980 to 2018, from $630 to $1,448 per person.

“Neoliberalism” is now part of the left’s lexicon, but I looked in vain to find it in the plain print of federal budgets, at least as far as aid to the poor was concerned. There is no evidence that the United States has become stingier over time. The opposite is true.

This makes the country’s stalled progress on poverty even more baffling. Decade after decade, the poverty rate has remained flat even as federal relief has surged.

If we have more than doubled government spending on poverty and achieved so little, one reason is that the American welfare state is a leaky bucket. Take welfare, for example: When it was administered through the Aid to Families With Dependent Children program, almost all of its funds were used to provide single-parent families with cash assistance. But when President Bill Clinton reformed welfare in 1996, replacing the old model with Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), he transformed the program into a block grant that gives states considerable leeway in deciding how to distribute the money. As a result, states have come up with rather creative ways to spend TANF dollars. Arizona has used welfare money to pay for abstinence-only sex education. Pennsylvania diverted TANF funds to anti-abortion crisis-pregnancy centers. Maine used the money to support a Christian summer camp. Nationwide, for every dollar budgeted for TANF in 2020, poor families directly received just 22 cents.

We’ve approached the poverty question by pointing to poor people themselves, when we should have been focusing on exploitation.

A fair amount of government aid earmarked for the poor never reaches them. But this does not fully solve the puzzle of why poverty has been so stubbornly persistent, because many of the country’s largest social-welfare programs distribute funds directly to people. Roughly 85 percent of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program budget is dedicated to funding food stamps themselves, and almost 93 percent of Medicaid dollars flow directly to beneficiaries.

There are, it would seem, deeper structural forces at play, ones that have to do with the way the American poor are routinely taken advantage of. The primary reason for our stalled progress on poverty reduction has to do with the fact that we have not confronted the unrelenting exploitation of the poor in the labor, housing and financial markets.

As a theory of poverty, “exploitation” elicits a muddled response, causing us to think of course and but, no in the same instant. The word carries a moral charge, but social scientists have a fairly coolheaded way to measure exploitation: When we are underpaid relative to the value of what we produce, we experience labor exploitation; when we are overcharged relative to the value of something we purchase, we experience consumer exploitation. For example, if a family paid $1,000 a month to rent an apartment with a market value of $20,000, that family would experience a higher level of renter exploitation than a family who paid the same amount for an apartment with a market valuation of $100,000. When we don’t own property or can’t access credit, we become dependent on people who do and can, which in turn invites exploitation, because a bad deal for you is a good deal for me.

Our vulnerability to exploitation grows as our liberty shrinks. Because labor laws often fail to protect undocumented workers in practice, more than a third are paid below minimum wage, and nearly 85 percent are not paid overtime. Many of us who are U.S. citizens, or who crossed borders through official checkpoints, would not work for these wages. We don’t have to. If they migrate here as adults, those undocumented workers choose the terms of their arrangement. But just because desperate people accept and even seek out exploitative conditions doesn’t make those conditions any less exploitative. Sometimes exploitation is simply the best bad option.

Consider how many employers now get one over on American workers. The United States offers some of the lowest wages in the industrialized world. A larger share of workers in the United States make “low pay” — earning less than two-thirds of median wages — than in any other country belonging to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. According to the group, nearly 23 percent of American workers labor in low-paying jobs, compared with roughly 17 percent in Britain, 11 percent in Japan and 5 percent in Italy. Poverty wages have swollen the ranks of the American working poor, most of whom are 35 or older.

One popular theory for the loss of good jobs is deindustrialization, which caused the shuttering of factories and the hollowing out of communities that had sprung up around them. Such a passive word, “deindustrialization” — leaving the impression that it just happened somehow, as if the country got deindustrialization the way a forest gets infested by bark beetles. But economic forces framed as inexorable, like deindustrialization and the acceleration of global trade, are often helped along by policy decisions like the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement, which made it easier for companies to move their factories to Mexico and contributed to the loss of hundreds of thousands of American jobs. The world has changed, but it has changed for other economies as well. Yet Belgium and Canada and many other countries haven’t experienced the kind of wage stagnation and surge in income inequality that the United States has.

Those countries managed to keep their unions. We didn’t. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, nearly a third of all U.S. workers carried union cards. These were the days of the United Automobile Workers, led by Walter Reuther, once savagely beaten by Ford’s brass-knuckle boys, and of the mighty American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations that together represented around 15 million workers, more than the population of California at the time.

In their heyday, unions put up a fight. In 1970 alone, 2.4 million union members participated in work stoppages, wildcat strikes and tense standoffs with company heads. The labor movement fought for better pay and safer working conditions and supported antipoverty policies. Their efforts paid off for both unionized and nonunionized workers, as companies like Eastman Kodak were compelled to provide generous compensation and benefits to their workers to prevent them from organizing. By one estimate, the wages of nonunionized men without a college degree would be 8 percent higher today if union strength remained what it was in the late 1970s, a time when worker pay climbed, chief-executive compensation was reined in and the country experienced the most economically equitable period in modern history.

It is important to note that Old Labor was often a white man’s refuge. In the 1930s, many unions outwardly discriminated against Black workers or segregated them into Jim Crow local chapters. In the 1960s, unions like the Brotherhood of Railway and Steamship Clerks and the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America enforced segregation within their ranks. Unions harmed themselves through their self-defeating racism and were further weakened by a changing economy. But organized labor was also attacked by political adversaries. As unions flagged, business interests sensed an opportunity. Corporate lobbyists made deep inroads in both political parties, beginning a public-relations campaign that pressured policymakers to roll back worker protections.

A national litmus test arrived in 1981, when 13,000 unionized air traffic controllers left their posts after contract negotiations with the Federal Aviation Administration broke down. When the workers refused to return, Reagan fired all of them. The public’s response was muted, and corporate America learned that it could crush unions with minimal blowback. And so it went, in one industry after another.

Today almost all private-sector employees (94 percent) are without a union, though roughly half of nonunion workers say they would organize if given the chance. They rarely are. Employers have at their disposal an arsenal of tactics designed to prevent collective bargaining, from hiring union-busting firms to telling employees that they could lose their jobs if they vote yes. Those strategies are legal, but companies also make illegal moves to block unions, like disciplining workers for trying to organize or threatening to close facilities. In 2016 and 2017, the National Labor Relations Board charged 42 percent of employers with violating federal law during union campaigns. In nearly a third of cases, this involved illegally firing workers for organizing.

Corporate lobbyists told us that organized labor was a drag on the economy — that once the companies had cleared out all these fusty, lumbering unions, the economy would rev up, raising everyone’s fortunes. But that didn’t come to pass. The negative effects of unions have been wildly overstated, and there is now evidence that unions play a role in increasing company productivity, for example by reducing turnover. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics measures productivity as how efficiently companies turn inputs (like materials and labor) into outputs (like goods and services). Historically, productivity, wages and profits rise and fall in lock step. But the American economy is less productive today than it was in the post-World War II period, when unions were at peak strength. The economies of other rich countries have slowed as well, including those with more highly unionized work forces, but it is clear that diluting labor power in America did not unleash economic growth or deliver prosperity to more people. “We were promised economic dynamism in exchange for inequality,” Eric Posner and Glen Weyl write in their book “Radical Markets.” “We got the inequality, but dynamism is actually declining.”

As workers lost power, their jobs got worse. For several decades after World War II, ordinary workers’ inflation-adjusted wages (known as “real wages”) increased by 2 percent each year. But since 1979, real wages have grown by only 0.3 percent a year. Astonishingly, workers with a high school diploma made 2.7 percent less in 2017 than they would have in 1979, adjusting for inflation. Workers without a diploma made nearly 10 percent less.

Lousy, underpaid work is not an indispensable, if regrettable, byproduct of capitalism, as some business defenders claim today. (This notion would have scandalized capitalism’s earliest defenders. John Stuart Mill, arch advocate of free people and free markets, once said that if widespread scarcity was a hallmark of capitalism, he would become a communist.) But capitalism is inherently about owners trying to give as little, and workers trying to get as much, as possible. With unions largely out of the picture, corporations have chipped away at the conventional midcentury work arrangement, which involved steady employment, opportunities for advancement and raises and decent pay with some benefits.

As the sociologist Gerald Davis has put it: Our grandparents had careers. Our parents had jobs. We complete tasks. Or at least that has been the story of the American working class and working poor.

Poor Americans aren’t just exploited in the labor market. They face consumer exploitation in the housing and financial markets as well.

There is a long history of slum exploitation in America. Money made slums because slums made money. Rent has more than doubled over the past two decades, rising much faster than renters’ incomes. Median rent rose from $483 in 2000 to $1,216 in 2021. Why have rents shot up so fast? Experts tend to offer the same rote answers to this question. There’s not enough housing supply, they say, and too much demand. Landlords must charge more just to earn a decent rate of return. Must they? How do we know?

We need more housing; no one can deny that. But rents have jumped even in cities with plenty of apartments to go around. At the end of 2021, almost 19 percent of rental units in Birmingham, Ala., sat vacant, as did 12 percent of those in Syracuse, N.Y. Yet rent in those areas increased by roughly 14 percent and 8 percent, respectively, over the previous two years. National data also show that rental revenues have far outpaced property owners’ expenses in recent years, especially for multifamily properties in poor neighborhoods. Rising rents are not simply a reflection of rising operating costs. There’s another dynamic at work, one that has to do with the fact that poor people — and particularly poor Black families — don’t have much choice when it comes to where they can live. Because of that, landlords can overcharge them, and they do.

A study I published with Nathan Wilmers found that after accounting for all costs, landlords operating in poor neighborhoods typically take in profits that are double those of landlords operating in affluent communities. If down-market landlords make more, it’s because their regular expenses (especially their mortgages and property-tax bills) are considerably lower than those in upscale neighborhoods. But in many cities with average or below-average housing costs — think Buffalo, not Boston — rents in the poorest neighborhoods are not drastically lower than rents in the middle-class sections of town. From 2015 to 2019, median monthly rent for a two-bedroom apartment in the Indianapolis metropolitan area was $991; it was $816 in neighborhoods with poverty rates above 40 percent, just around 17 percent less. Rents are lower in extremely poor neighborhoods, but not by as much as you would think.

Yet where else can poor families live? They are shut out of homeownership because banks are disinclined to issue small-dollar mortgages, and they are also shut out of public housing, which now has waiting lists that stretch on for years and even decades. Struggling families looking for a safe, affordable place to live in America usually have but one choice: to rent from private landlords and fork over at least half their income to rent and utilities. If millions of poor renters accept this state of affairs, it’s not because they can’t afford better alternatives; it’s because they often aren’t offered any.

You can read injunctions against usury in the Vedic texts of ancient India, in the sutras of Buddhism and in the Torah. Aristotle and Aquinas both rebuked it. Dante sent moneylenders to the seventh circle of hell. None of these efforts did much to stem the practice, but they do reveal that the unprincipled act of trapping the poor in a cycle of debt has existed at least as long as the written word. It might be the oldest form of exploitation after slavery. Many writers have depicted America’s poor as unseen, shadowed and forgotten people: as “other” or “invisible.” But markets have never failed to notice the poor, and this has been particularly true of the market for money itself.

The deregulation of the banking system in the 1980s heightened competition among banks. Many responded by raising fees and requiring customers to carry minimum balances. In 1977, over a third of banks offered accounts with no service charge. By the early 1990s, only 5 percent did. Big banks grew bigger as community banks shuttered, and in 2021, the largest banks in America charged customers almost $11 billion in overdraft fees. Previous research showed that just 9 percent of account holders paid 84 percent of these fees. Who were the unlucky 9 percent? Customers who carried an average balance of less than $350. The poor were made to pay for their poverty.

In 2021, the average fee for overdrawing your account was $33.58. Because banks often issue multiple charges a day, it’s not uncommon to overdraw your account by $20 and end up paying $200 for it. Banks could (and do) deny accounts to people who have a history of overextending their money, but those customers also provide a steady revenue stream for some of the most powerful financial institutions in the world.

Every year: almost $11 billion in overdraft fees, $1.6 billion in check-cashing fees and up to $8.2 billion in payday-loan fees.

According to the F.D.I.C., one in 19 U.S. households had no bank account in 2019, amounting to more than seven million families. Compared with white families, Black and Hispanic families were nearly five times as likely to lack a bank account. Where there is exclusion, there is exploitation. Unbanked Americans have created a market, and thousands of check-cashing outlets now serve that market. Check-cashing stores generally charge from 1 to 10 percent of the total, depending on the type of check. That means that a worker who is paid $10 an hour and takes a $1,000 check to a check-cashing outlet will pay $10 to $100 just to receive the money he has earned, effectively losing one to 10 hours of work. (For many, this is preferable to the less-predictable exploitation by traditional banks, with their automatic overdraft fees. It’s the devil you know.) In 2020, Americans spent $1.6 billion just to cash checks. If the poor had a costless way to access their own money, over a billion dollars would have remained in their pockets during the pandemic-induced recession.

Poverty can mean missed payments, which can ruin your credit. But just as troublesome as bad credit is having no credit score at all, which is the case for 26 million adults in the United States. Another 19 million possess a credit history too thin or outdated to be scored. Having no credit (or bad credit) can prevent you from securing an apartment, buying insurance and even landing a job, as employers are increasingly relying on credit checks during the hiring process. And when the inevitable happens — when you lose hours at work or when the car refuses to start — the payday-loan industry steps in.

For most of American history, regulators prohibited lending institutions from charging exorbitant interest on loans. Because of these limits, banks kept interest rates between 6 and 12 percent and didn’t do much business with the poor, who in a pinch took their valuables to the pawnbroker or the loan shark. But the deregulation of the banking sector in the 1980s ushered the money changers back into the temple by removing strict usury limits. Interest rates soon reached 300 percent, then 500 percent, then 700 percent. Suddenly, some people were very interested in starting businesses that lent to the poor. In recent years, 17 states have brought back strong usury limits, capping interest rates and effectively prohibiting payday lending. But the trade thrives in most places. The annual percentage rate for a two-week $300 loan can reach 460 percent in California, 516 percent in Wisconsin and 664 percent in Texas.

Roughly a third of all payday loans are now issued online, and almost half of borrowers who have taken out online loans have had lenders overdraw their bank accounts. The average borrower stays indebted for five months, paying $520 in fees to borrow $375. Keeping people indebted is, of course, the ideal outcome for the payday lender. It’s how they turn a $15 profit into a $150 one. Payday lenders do not charge high fees because lending to the poor is risky — even after multiple extensions, most borrowers pay up. Lenders extort because they can.

Every year: almost $11 billion in overdraft fees, $1.6 billion in check-cashing fees and up to $8.2 billion in payday-loan fees. That’s more than $55 million in fees collected predominantly from low-income Americans each day — not even counting the annual revenue collected by pawnshops and title loan services and rent-to-own schemes. When James Baldwin remarked in 1961 how “extremely expensive it is to be poor,” he couldn’t have imagined these receipts.

“Predatory inclusion” is what the historian Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor calls it in her book “Race for Profit,” describing the longstanding American tradition of incorporating marginalized people into housing and financial schemes through bad deals when they are denied good ones. The exclusion of poor people from traditional banking and credit systems has forced them to find alternative ways to cash checks and secure loans, which has led to a normalization of their exploitation. This is all perfectly legal, after all, and subsidized by the nation’s richest commercial banks. The fringe banking sector would not exist without lines of credit extended by the conventional one. Wells Fargo and JPMorgan Chase bankroll payday lenders like Advance America and Cash America. Everybody gets a cut.

Poverty isn’t simply the condition of not having enough money. It’s the condition of not having enough choice and being taken advantage of because of that. When we ignore the role that exploitation plays in trapping people in poverty, we end up designing policy that is weak at best and ineffective at worst. For example, when legislation lifts incomes at the bottom without addressing the housing crisis, those gains are often realized instead by landlords, not wholly by the families the legislation was intended to help. A 2019 study conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia found that when states raised minimum wages, families initially found it easier to pay rent. But landlords quickly responded to the wage bumps by increasing rents, which diluted the effect of the policy. This happened after the pandemic rescue packages, too: When wages began to rise in 2021 after worker shortages, rents rose as well, and soon people found themselves back where they started or worse.

Antipoverty programs work. Each year, millions of families are spared the indignities and hardships of severe deprivation because of these government investments. But our current antipoverty programs cannot abolish poverty by themselves. The Johnson administration started the War on Poverty and the Great Society in 1964. These initiatives constituted a bundle of domestic programs that included the Food Stamp Act, which made food aid permanent; the Economic Opportunity Act, which created Job Corps and Head Start; and the Social Security Amendments of 1965, which founded Medicare and Medicaid and expanded Social Security benefits. Nearly 200 pieces of legislation were signed into law in President Lyndon B. Johnson’s first five years in office, a breathtaking level of activity. And the result? Ten years after the first of these programs were rolled out in 1964, the share of Americans living in poverty was half what it was in 1960.

But the War on Poverty and the Great Society were started during a time when organized labor was strong, incomes were climbing, rents were modest and the fringe banking industry as we know it today didn’t exist. Today multiple forms of exploitation have turned antipoverty programs into something like dialysis, a treatment designed to make poverty less lethal, not to make it disappear.

This means we don’t just need deeper antipoverty investments. We need different ones, policies that refuse to partner with poverty, policies that threaten its very survival. We need to ensure that aid directed at poor people stays in their pockets, instead of being captured by companies whose low wages are subsidized by government benefits, or by landlords who raise the rents as their tenants’ wages rise, or by banks and payday-loan outlets who issue exorbitant fines and fees. Unless we confront the many forms of exploitation that poor families face, we risk increasing government spending only to experience another 50 years of sclerosis in the fight against poverty.

The best way to address labor exploitation is to empower workers. A renewed contract with American workers should make organizing easy. As things currently stand, unionizing a workplace is incredibly difficult. Under current labor law, workers who want to organize must do so one Amazon warehouse or one Starbucks location at a time. We have little chance of empowering the nation’s warehouse workers and baristas this way. This is why many new labor movements are trying to organize entire sectors. The Fight for $15 campaign, led by the Service Employees International Union, doesn’t focus on a single franchise (a specific McDonald’s store) or even a single company (McDonald’s) but brings together workers from several fast-food chains. It’s a new kind of labor power, and one that could be expanded: If enough workers in a specific economic sector — retail, hotel services, nursing — voted for the measure, the secretary of labor could establish a bargaining panel made up of representatives elected by the workers. The panel could negotiate with companies to secure the best terms for workers across the industry. This is a way to organize all Amazon warehouses and all Starbucks locations in a single go.

Sectoral bargaining, as it’s called, would affect tens of millions of Americans who have never benefited from a union of their own, just as it has improved the lives of workers in Europe and Latin America. The idea has been criticized by members of the business community, like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which has raised concerns about the inflexibility and even the constitutionality of sectoral bargaining, as well as by labor advocates, who fear that industrywide policies could nullify gains that existing unions have made or could be achieved only if workers make other sacrifices. Proponents of the idea counter that sectoral bargaining could even the playing field, not only between workers and bosses, but also between companies in the same sector that would no longer be locked into a race to the bottom, with an incentive to shortchange their work force to gain a competitive edge. Instead, the companies would be forced to compete over the quality of the goods and services they offer. Maybe we would finally reap the benefits of all that economic productivity we were promised.

We must also expand the housing options for low-income families. There isn’t a single right way to do this, but there is clearly a wrong way: the way we’re doing it now. One straightforward approach is to strengthen our commitment to the housing programs we already have. Public housing provides affordable homes to millions of Americans, but it’s drastically underfunded relative to the need. When the wealthy township of Cherry Hill, N.J., opened applications for 29 affordable apartments in 2021, 9,309 people applied. The sky-high demand should tell us something, though: that affordable housing is a life changer, and families are desperate for it.

We could also pave the way for more Americans to become homeowners, an initiative that could benefit poor, working-class and middle-class families alike — as well as scores of young people. Banks generally avoid issuing small-dollar mortgages, not because they’re riskier — these mortgages have the same delinquency rates as larger mortgages — but because they’re less profitable. Over the life of a mortgage, interest on $1 million brings in a lot more money than interest on $75,000. This is where the federal government could step in, providing extra financing to build on-ramps to first-time homeownership. In fact, it already does so in rural America through the 502 Direct Loan Program, which has moved more than two million families into their own homes. These loans, fully guaranteed and serviced by the Department of Agriculture, come with low interest rates and, for very poor families, cover the entire cost of the mortgage, nullifying the need for a down payment. Last year, the average 502 Direct Loan was for $222,300 but cost the government only $10,370 per loan, chump change for such a durable intervention. Expanding a program like this into urban communities would provide even more low- and moderate-income families with homes of their own.

We should also ensure fair access to capital. Banks should stop robbing the poor and near-poor of billions of dollars each year, immediately ending exorbitant overdraft fees. As the legal scholar Mehrsa Baradaran has pointed out, when someone overdraws an account, banks could simply freeze the transaction or could clear a check with insufficient funds, providing customers a kind of short-term loan with a low interest rate of, say, 1 percent a day.

States should rein in payday-lending institutions and insist that lenders make it clear to potential borrowers what a loan is ultimately likely to cost them. Just as fast-food restaurants must now publish calorie counts next to their burgers and shakes, payday-loan stores should publish the average overall cost of different loans. When Texas adopted disclosure rules, residents took out considerably fewer bad loans. If Texas can do this, why not California or Wisconsin? Yet to stop financial exploitation, we need to expand, not limit, low-income Americans’ access to credit. Some have suggested that the government get involved by having the U.S. Postal Service or the Federal Reserve issue small-dollar loans. Others have argued that we should revise government regulations to entice commercial banks to pitch in. Whatever our approach, solutions should offer low-income Americans more choice, a way to end their reliance on predatory lending institutions that can get away with robbery because they are the only option available.

In Tommy Orange’s novel, “There There,” a man trying to describe the problem of suicides on Native American reservations says: “Kids are jumping out the windows of burning buildings, falling to their deaths. And we think the problem is that they’re jumping.” The poverty debate has suffered from a similar kind of myopia. For the past half-century, we’ve approached the poverty question by pointing to poor people themselves — posing questions about their work ethic, say, or their welfare benefits — when we should have been focusing on the fire. The question that should serve as a looping incantation, the one we should ask every time we drive past a tent encampment, those tarped American slums smelling of asphalt and bodies, or every time we see someone asleep on the bus, slumped over in work clothes, is simply: Who benefits? Not: Why don’t you find a better job? Or: Why don’t you move? Or: Why don’t you stop taking out payday loans? But: Who is feeding off this?

Those who have amassed the most power and capital bear the most responsibility for America’s vast poverty: political elites who have utterly failed low-income Americans over the past half-century; corporate bosses who have spent and schemed to prioritize profits over families; lobbyists blocking the will of the American people with their self-serving interests; property owners who have exiled the poor from entire cities and fueled the affordable-housing crisis. Acknowledging this is both crucial and deliciously absolving; it directs our attention upward and distracts us from all the ways (many unintentional) that we — we the secure, the insured, the housed, the college-educated, the protected, the lucky — also contribute to the problem.

Corporations benefit from worker exploitation, sure, but so do consumers, who buy the cheap goods and services the working poor produce, and so do those of us directly or indirectly invested in the stock market. Landlords are not the only ones who benefit from housing exploitation; many homeowners do, too, their property values propped up by the collective effort to make housing scarce and expensive. The banking and payday-lending industries profit from the financial exploitation of the poor, but so do those of us with free checking accounts, as those accounts are subsidized by billions of dollars in overdraft fees.

Living our daily lives in ways that express solidarity with the poor could mean we pay more; anti-exploitative investing could dampen our stock portfolios. By acknowledging those costs, we acknowledge our complicity. Unwinding ourselves from our neighbors’ deprivation and refusing to live as enemies of the poor will require us to pay a price. It’s the price of our restored humanity and renewed country.

Matthew Desmond is a professor of sociology at Princeton University and a contributing writer for the magazine. His latest book, “Poverty, by America,” from which this article is adapted, is being published on March 21 by Crown.

An earlier version of this article referred incorrectly to the legal protections for undocumented workers. They are afforded rights under U.S. labor laws, though in practice those laws often fail to protect them.

An earlier version of this article implied an incorrect date for a statistic about overdraft fees. The research was conducted between 2005 and 2012, not in 2021.

How we handle corrections

Advertisement

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2.4 The Consequences of Poverty

Learning objectives.

- Describe the family and housing problems associated with poverty.

- Explain how poverty affects health and educational attainment.

Regardless of its causes, poverty has devastating consequences for the people who live in it. Much research conducted and/or analyzed by scholars, government agencies, and nonprofit organizations has documented the effects of poverty (and near poverty) on the lives of the poor (Lindsey, 2009; Moore, et. al., 2009; Ratcliffe & McKernan, 2010; Sanders, 2011). Many of these studies focus on childhood poverty, and these studies make it very clear that childhood poverty has lifelong consequences. In general, poor children are more likely to be poor as adults, more likely to drop out of high school, more likely to become a teenaged parent, and more likely to have employment problems. Although only 1 percent of children who are never poor end up being poor as young adults, 32 percent of poor children become poor as young adults (Ratcliffe & McKernan, 2010).

Poor children are more likely to have inadequate nutrition and to experience health, behavioral, and cognitive problems.

Kelly Short – Poverty: “Damaged Child,” Oklahoma City, OK, USA, 1936. (Colorized). – CC BY-SA 2.0.

A recent study used government data to follow children born between 1968 and 1975 until they were ages 30 to 37 (Duncan & Magnuson, 2011). The researchers compared individuals who lived in poverty in early childhood to those whose families had incomes at least twice the poverty line in early childhood. Compared to the latter group, adults who were poor in early childhood

- had completed two fewer years of schooling on the average;

- had incomes that were less than half of those earned by adults who had wealthier childhoods;

- received $826 more annually in food stamps on the average;

- were almost three times more likely to report being in poor health;

- were twice as likely to have been arrested (males only); and

- were five times as likely to have borne a child (females only).

We discuss some of the major specific consequences of poverty here and will return to them in later chapters.

Family Problems

The poor are at greater risk for family problems, including divorce and domestic violence. As Chapter 9 “Sexual Behavior” explains, a major reason for many of the problems families experience is stress. Even in families that are not poor, running a household can cause stress, children can cause stress, and paying the bills can cause stress. Families that are poor have more stress because of their poverty, and the ordinary stresses of family life become even more intense in poor families. The various kinds of family problems thus happen more commonly in poor families than in wealthier families. Compounding this situation, when these problems occur, poor families have fewer resources than wealthier families to deal with these problems.

Children and Our Future

Getting under Children’s Skin: The Biological Effects of Childhood Poverty

As the text discusses, childhood poverty often has lifelong consequences. Poor children are more likely to be poor when they become adults, and they are at greater risk for antisocial behavior when young, and for unemployment, criminal behavior, and other problems when they reach adolescence and young adulthood.

According to growing evidence, one reason poverty has these consequences is that it has certain neural effects on poor children that impair their cognitive abilities and thus their behavior and learning potential. As Greg J. Duncan and Katherine Magnuson (Duncan & Magnuson, 2011, p. 23) observe, “Emerging research in neuroscience and developmental psychology suggests that poverty early in a child’s life may be particularly harmful because the astonishingly rapid development of young children’s brains leaves them sensitive (and vulnerable) to environmental conditions.”

In short, poverty can change the way the brain develops in young children. The major reason for this effect is stress. Children growing up in poverty experience multiple stressful events: neighborhood crime and drug use; divorce, parental conflict, and other family problems, including abuse and neglect by their parents; parental financial problems and unemployment; physical and mental health problems of one or more family members; and so forth. Their great levels of stress in turn affect their bodies in certain harmful ways. As two poverty scholars note, “It’s not just that poverty-induced stress is mentally taxing. If it’s experienced early enough in childhood, it can in fact get ‘under the skin’ and change the way in which the body copes with the environment and the way in which the brain develops. These deep, enduring, and sometimes irreversible physiological changes are the very human price of running a high-poverty society” (Grusky & Wimer, 2011, p. 2).

One way poverty gets “under children’s skin” is as follows (Evans, et. al., 2011). Poor children’s high levels of stress produce unusually high levels of stress hormones such as cortisol and higher levels of blood pressure. Because these high levels impair their neural development, their memory and language development skills suffer. This result in turn affects their behavior and learning potential. For other physiological reasons, high levels of stress also affect the immune system, so that poor children are more likely to develop various illnesses during childhood and to have high blood pressure and other health problems when they grow older, and cause other biological changes that make poor children more likely to end up being obese and to have drug and alcohol problems.

The policy implications of the scientific research on childhood poverty are clear. As public health scholar Jack P. Shonkoff (Shonkoff, 2011) explains, “Viewing this scientific evidence within a biodevelopmental framework points to the particular importance of addressing the needs of our most disadvantaged children at the earliest ages.” Duncan and Magnuson (Duncan & Magnuson, 2011) agree that “greater policy attention should be given to remediating situations involving deep and persistent poverty occurring early in childhood.” To reduce poverty’s harmful physiological effects on children, Skonkoff advocates efforts to promote strong, stable relationships among all members of poor families; to improve the quality of the home and neighborhood physical environments in which poor children grow; and to improve the nutrition of poor children. Duncan and Magnuson call for more generous income transfers to poor families with young children and note that many European democracies provide many kinds of support to such families. The recent scientific evidence on early childhood poverty underscores the importance of doing everything possible to reduce the harmful effects of poverty during the first few years of life.

Health, Illness, and Medical Care

The poor are also more likely to have many kinds of health problems, including infant mortality, earlier adulthood mortality, and mental illness, and they are also more likely to receive inadequate medical care. Poor children are more likely to have inadequate nutrition and, partly for this reason, to suffer health, behavioral, and cognitive problems. These problems in turn impair their ability to do well in school and land stable employment as adults, helping to ensure that poverty will persist across generations. Many poor people are uninsured or underinsured, at least until the US health-care reform legislation of 2010 takes full effect a few years from now, and many have to visit health clinics that are overcrowded and understaffed.

As Chapter 12 “Work and the Economy” discusses, it is unclear how much of poor people’s worse health stems from their lack of money and lack of good health care versus their own behavior such as smoking and eating unhealthy diets. Regardless of the exact reasons, however, the fact remains that poor health is a major consequence of poverty. According to recent research, this fact means that poverty is responsible for almost 150,000 deaths annually, a figure about equal to the number of deaths from lung cancer (Bakalar, 2011).

Poor children typically go to rundown schools with inadequate facilities where they receive inadequate schooling. They are much less likely than wealthier children to graduate from high school or to go to college. Their lack of education in turn restricts them and their own children to poverty, once again helping to ensure a vicious cycle of continuing poverty across generations. As Chapter 10 “The Changing Family” explains, scholars debate whether the poor school performance of poor children stems more from the inadequacy of their schools and schooling versus their own poverty. Regardless of exactly why poor children are more likely to do poorly in school and to have low educational attainment, these educational problems are another major consequence of poverty.

Housing and Homelessness

The poor are, not surprisingly, more likely to be homeless than the nonpoor but also more likely to live in dilapidated housing and unable to buy their own homes. Many poor families spend more than half their income on rent, and they tend to live in poor neighborhoods that lack job opportunities, good schools, and other features of modern life that wealthier people take for granted. The lack of adequate housing for the poor remains a major national problem. Even worse is outright homelessness. An estimated 1.6 million people, including more than 300,000 children, are homeless at least part of the year (Lee, et. al., 2010).

Crime and Victimization

As Chapter 7 “Alcohol and Other Drugs” discusses, poor (and near poor) people account for the bulk of our street crime (homicide, robbery, burglary, etc.), and they also account for the bulk of victims of street crime. That chapter will outline several reasons for this dual connection between poverty and street crime, but they include the deep frustration and stress of living in poverty and the fact that many poor people live in high-crime neighborhoods. In such neighborhoods, children are more likely to grow up under the influence of older peers who are already in gangs or otherwise committing crime, and people of any age are more likely to become crime victims. Moreover, because poor and near-poor people are more likely to commit street crime, they also comprise most of the people arrested for street crimes, convicted of street crime, and imprisoned for street crime. Most of the more than 2 million people now in the nation’s prisons and jails come from poor or near-poor backgrounds. Criminal behavior and criminal victimization, then, are other major consequences of poverty.

Lessons from Other Societies

Poverty and Poverty Policy in Other Western Democracies

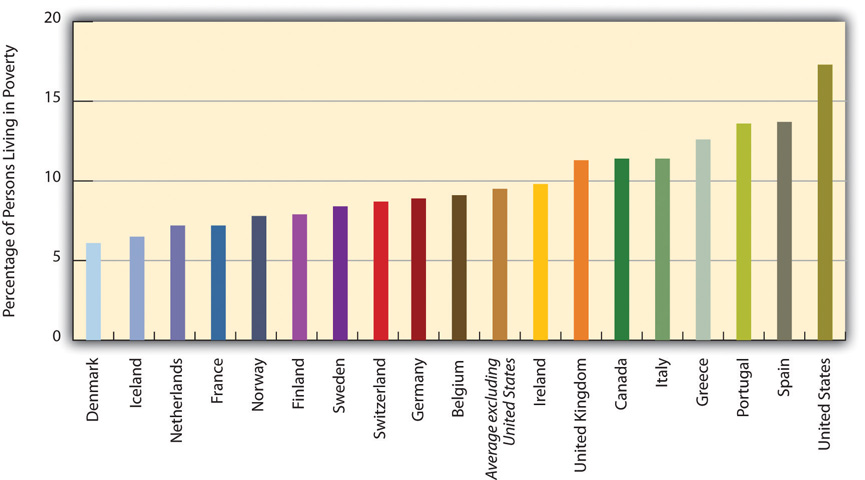

To compare international poverty rates, scholars commonly use a measure of the percentage of households in a nation that receive less than half of the nation’s median household income after taxes and cash transfers from the government. In data from the late 2000s, 17.3 percent of US households lived in poverty as defined by this measure. By comparison, other Western democracies had the rates depicted in the figure that follows. The average poverty rate of the nations in the figure excluding the United States is 9.5 percent. The US rate is thus almost twice as high as the average for all the other democracies.

This graph illustrates the poverty rates in western democracies (i.e., the percentage of persons living with less than half of the median household income) as of the late 2000s

Source: Data from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2011). Society at a glance 2011: OECD social indicators. Retrieved July 23, 2011, from http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/soc_glance-2011-en/06/02/index.html;jsessionid=erdqhbpb203ea.epsilon?contentType=&itemId=/content/chapter/soc_glance-2011-17-en&containerItemId=/content/se .

Why is there so much more poverty in the United States than in its Western counterparts? Several differences between the United States and the other nations stand out (Brady, 2009; Russell, 2011). First, other Western nations have higher minimum wages and stronger labor unions than the United States has, and these lead to incomes that help push people above poverty. Second, these other nations spend a much greater proportion of their gross domestic product on social expenditures (income support and social services such as child-care subsidies and housing allowances) than does the United States. As sociologist John Iceland (Iceland, 2006) notes, “Such countries often invest heavily in both universal benefits, such as maternity leave, child care, and medical care, and in promoting work among [poor] families…The United States, in comparison with other advanced nations, lacks national health insurance, provides less publicly supported housing, and spends less on job training and job creation.” Block and colleagues agree: “These other countries all take a more comprehensive government approach to combating poverty, and they assume that it is caused by economic and structural factors rather than bad behavior” (Block et, al., 2006).

The experience of the United Kingdom provides a striking contrast between the effectiveness of the expansive approach used in other wealthy democracies and the inadequacy of the American approach. In 1994, about 30 percent of British children lived in poverty; by 2009, that figure had fallen by more than half to 12 percent. Meanwhile, the US 2009 child poverty rate, was almost 21 percent.

Britain used three strategies to reduce its child poverty rate and to help poor children and their families in other ways. First, it induced more poor parents to work through a series of new measures, including a national minimum wage higher than its US counterpart and various tax savings for low-income workers. Because of these measures, the percentage of single parents who worked rose from 45 percent in 1997 to 57 percent in 2008. Second, Britain increased child welfare benefits regardless of whether a parent worked. Third, it increased paid maternity leave from four months to nine months, implemented two weeks of paid paternity leave, established universal preschool (which both helps children’s cognitive abilities and makes it easier for parents to afford to work), increased child-care aid, and made it possible for parents of young children to adjust their working hours to their parental responsibilities (Waldfogel, 2010). While the British child poverty rate fell dramatically because of these strategies, the US child poverty rate stagnated.

In short, the United States has so much more poverty than other democracies in part because it spends so much less than they do on helping the poor. The United States certainly has the wealth to follow their example, but it has chosen not to do so, and a high poverty rate is the unfortunate result. As the Nobel laureate economist Paul Krugman (2006, p. A25) summarizes this lesson, “Government truly can be a force for good. Decades of propaganda have conditioned many Americans to assume that government is always incompetent…But the [British experience has] shown that a government that seriously tries to reduce poverty can achieve a lot.”

Key Takeaways

- Poor people are more likely to have several kinds of family problems, including divorce and family conflict.

- Poor people are more likely to have several kinds of health problems.

- Children growing up in poverty are less likely to graduate high school or go to college, and they are more likely to commit street crime.

For Your Review

- Write a brief essay that summarizes the consequences of poverty.

- Why do you think poor children are more likely to develop health problems?

Bakalar, N. (2011, July 4). Researchers link deaths to social ills. New York Times , p. D5.

Block, F., Korteweg, A. C., & Woodward, K. (2006). The compassion gap in American poverty policy. Contexts, 5 (2), 14–20.

Brady, D. (2009). Rich democracies, poor people: How politics explain poverty . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Duncan, G. J., & Magnuson, K. (2011, winter). The long reach of early childhood poverty. Pathways: A Magazine on Poverty, Inequality, and Social Policy , 22–27.

Evans, G. W., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Klebanov, P. K. (2011, winter). Stressing out the poor: Chronic physiological stress and the income-achievement gap. Pathways: A Magazine on Poverty, Inequality, and Social Policy , 16–21.

Grusky, D., & Wimer, C.(Eds.). (2011, winter). Editors’ note. Pathways: A Magazine on Poverty, Inequality, and Social Policy , 2.

Iceland, J. (2006). Poverty in America: A handbook . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Krugman, P. (Krugman, 2006). Helping the poor, the British way. New York Times , p. A25.

Lee, B., Tyler, K. A., & Wright, J. D. ( 2010). The new homelessness revisited. Annual Review of Sociology, 36 , 501–521.

Lindsey, D. (2009). Child poverty and inequality: Securing a better future for America’s children . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Moore, K. A., Redd, Z., Burkhauser, M., Mbawa, K., & Collins, A. (2009). Children in poverty: Trends, consequences, and policy options . Washington, DC: Child Trends. Retrieved from http://www.childtrends.org/Files//Child_Trends-2009_04_07_RB_ChildreninPoverty.pdf .

Ratcliffe, C., & McKernan, S.-M. (2010). Childhood poverty persistence: Facts and consequences . Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Russell, J. W. ( 2011). Double standard: Social policy in Europe and the United States (2nd ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Sanders, L. (2011). Neuroscience exposes pernicious effects of poverty. Science News, 179 (3), 32.

Shonkoff, J. P. (2011, winter). Building a foundation for prosperity on the science of early childhood development. Pathways: A Magazine on Poverty, Inequality, and Social Policy , 10–14.

Waldfogel, J. (2010). Britain’s war on poverty . New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Social Problems Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Why poverty is not a personal choice, but a reflection of society

Research Investigator of Psychiatry, Public Health, and Poverty Solutions, University of Michigan

Disclosure statement

Shervin Assari does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Michigan provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

As the Senate prepares to modify its version of the health care bill, now is a good time to back up and examine why we as a nation are so divided about providing health care, especially to the poor.

I believe one reason the United States is cutting spending on health insurance and safety nets that protect poor and marginalized people is because of American culture, which overemphasizes individual responsibility. Our culture does this to the point that it ignores the effect of root causes shaped by society and beyond the control of the individual. How laypeople define and attribute poverty may not be that much different from the way U.S. policymakers in the Senate see poverty.

As someone who studies poverty solutions and social and health inequalities, I am convinced by the academic literature that the biggest reason for poverty is how a society is structured. Without structural changes, it may be very difficult if not impossible to eliminate disparities and poverty.

Social structure

About 13.5 percent of Americans are living in poverty. Many of these people do not have insurance, and efforts to help them gain insurance, be it through Medicaid or private insurance, have been stymied. Medicaid provides insurance for the disabled, people in nursing homes and the poor.

Four states recently asked the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for permission to require Medicaid recipients in their states who are not disabled or elderly to work.

This request is reflective of the fact that many Americans believe that poverty is, by and large, the result of laziness , immorality and irresponsibility.

In fact, poverty and other social miseries are in large part due to social structure , which is how society functions at a macro level. Some societal issues, such as racism, sexism and segregation, constantly cause disparities in education, employment and income for marginalized groups. The majority group naturally has a head start, relative to groups that deal with a wide range of societal barriers on a daily basis. This is what I mean by structural causes of poverty and inequality.

Poverty: Not just a state of mind

We have all heard that the poor and minorities need only make better choices – work hard, stay in school, get married, do not have children before they can afford them. If they did all this, they wouldn’t be poor.

Just a few weeks ago, Housing Secretary Ben Carson called poverty “ a state of mind .” At the same time, his budget to help low-income households could be cut by more than US$6 billion next year.

This is an example of a simplistic view toward the complex social phenomenon. It is minimizing the impact of a societal issue caused by structure – macro‐level labor market and societal conditions – on individuals’ behavior. Such claims also ignore a large body of sociological science.

American independence

Americans have one of the most independent cultures on Earth. A majority of Americans define people in terms of internal attributes such as choices , abilities, values, preferences, decisions and traits.

This is very different from interdependent cultures , such as eastern Asian countries where people are seen mainly in terms of their environment, context and relationships with others.

A direct consequence of independent mindsets and cognitive models is that one may ignore all the historical and environmental conditions, such as slavery, segregation and discrimination against women, that contribute to certain outcomes. When we ignore the historical context, it is easier to instead attribute an unfavorable outcome, such as poverty, to the person.

Views shaped by politics

Many Americans view poverty as an individual phenomenon and say that it’s primarily their own fault that people are poor. The alternative view is that poverty is a structural phenomenon. From this viewpoint, people are in poverty because they find themselves in holes in the economic system that deliver them inadequate income.

The fact is that people move in and out of poverty. Research has shown that 45 percent of poverty spells last no more than a year, 70 percent last no more than three years and only 12 percent stretch beyond a decade.

The Panel Study of Income Dynamics ( PSID ), a 50-year longitudinal study of 18,000 Americans, has shown that around four in 10 adults experience an entire year of poverty from the ages of 25 to 60. The last Survey of Income and Program Participation ( SIPP ), a longitudinal survey conducted by the U.S. Census, had about one-third of Americans in episodic poverty at some point in a three-year period, but just 3.5 percent in episodic poverty for all three years.

Why calling the poor ‘lazy’ is victim blaming

If one believes that poverty is related to historical and environmental events and not just to an individual, we should be careful about blaming the poor for their fates.

Victim blaming occurs when the victim of a crime or any wrongful act is held entirely or partially responsible for the harm that befell them. It is a common psychological and societal phenomenon. Victimology has shown that humans have a tendency to perceive victims at least partially responsible . This is true even in rape cases, where there is a considerable tendency to blame victims and is true particularly if the victim and perpetrator know each other.

I believe all our lives could be improved if we considered the structural influences as root causes of social problems such as poverty and inequality. Perhaps then, we could more easily agree on solutions.

- Social mobility

- Homelessness

- Health disparities

- Health gaps

- US Senate health care bill

- US health care reform

Head, School of Psychology

Lecturer In Arabic Studies - Teaching Specialist

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

5 Essays About Poverty Everyone Should Know

Poverty is one of the driving forces of inequality in the world. Between 1990-2015, much progress was made. The number of people living on less than $1.90 went from 36% to 10%. However, according to the World Bank , the COVID-19 pandemic represents a serious problem that disproportionately impacts the poor. Research released in February of 2020 shows that by 2030, up to ⅔ of the “global extreme poor” will be living in conflict-affected and fragile economies. Poverty will remain a major human rights issue for decades to come. Here are five essays about the issue that everyone should know:

“We need an economic bill of rights” – Martin Luther King Jr.

The Guardian published an abridged version of this essay in 2018, which was originally released in Look magazine just after Dr. King was killed. In this piece, Dr. King explains why an economic bill of rights is necessary. He points out that while mass unemployment within the black community is a “social problem,” it’s a “depression” in the white community. An economic bill of rights would give a job to everyone who wants one and who can work. It would also give an income to those who can’t work. Dr. King affirms his commitment to non-violence. He’s fully aware that tensions are high. He quotes a spiritual, writing “timing is winding up.” Even while the nation progresses, poverty is getting worse.

This essay was reprinted and abridged in The Guardian in an arrangement with The Heirs to the Estate of Martin Luther King. Jr. The most visible representative of the Civil Rights Movement beginning in 1955, Dr. King was assassinated in 1968. His essays and speeches remain timely.

“How Poverty Can Follow Children Into Adulthood” – Priyanka Boghani

This article is from 2017, but it’s more relevant than ever because it was written when 2012 was the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. That’s no longer the case. In 2012, around ¼ American children were in poverty. Five years later, children were still more likely than adults to be poor. This is especially true for children of colour. Consequences of poverty include anxiety, hunger, and homelessness. This essay also looks at the long-term consequences that come from growing up in poverty. A child can develop health problems that affect them in adulthood. Poverty can also harm a child’s brain development. Being aware of how poverty affects children and follows them into adulthood is essential as the world deals with the economic fallout from the pandemic.

Priyanka Boghani is a journalist at PBS Frontline. She focuses on U.S. foreign policy, humanitarian crises, and conflicts in the Middle East. She also assists in managing Frontline’s social accounts.

“5 Reasons COVID-19 Will Impact the Fight to End Extreme Poverty” – Leah Rodriguez

For decades, the UN has attempted to end extreme poverty. In the face of the novel coronavirus outbreak, new challenges threaten the fight against poverty. In this essay, Dr. Natalie Linos, a Harvard social epidemiologist, urges the world to have a “social conversation” about how the disease impacts poverty and inequality. If nothing is done, it’s unlikely that the UN will meet its Global Goals by 2030. Poverty and COVID-19 intersect in five key ways. For one, low-income people are more vulnerable to disease. They also don’t have equal access to healthcare or job stability. This piece provides a clear, concise summary of why this outbreak is especially concerning for the global poor.

Leah Rodriguez’s writing at Global Citizen focuses on women, girls, water, and sanitation. She’s also worked as a web producer and homepage editor for New York Magazine’s The Cut.

“Climate apartheid”: World’s poor to suffer most from disasters” – Al Jazeera and news Agencies

The consequences of climate change are well-known to experts like Philip Alston, the special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights. In 2019, he submitted a report to the UN Human Rights Council sounding the alarm on how climate change will devastate the poor. While the wealthy will be able to pay their way out of devastation, the poor will not. This will end up creating a “climate apartheid.” Alston states that if climate change isn’t addressed, it will undo the last five decades of progress in poverty education, as well as global health and development .

“Nickel and Dimed: On (not) getting by in America” – Barbara Ehrenreich

In this excerpt from her book Nickel and Dimed, Ehrenreich describes her experience choosing to live undercover as an “unskilled worker” in the US. She wanted to investigate the impact the 1996 welfare reform act had on the working poor. Released in 2001, the events take place between the spring of 1998 and the summer of 2000. Ehrenreich decided to live in a town close to her “real life” and finds a place to live and a job. She has her eyes opened to the challenges and “special costs” of being poor. In 2019, The Guardian ranked the book 13th on their list of 100 best books of the 21st century.

Barbara Ehrenreich is the author of 21 books and an activist. She’s worked as an award-winning columnist and essayist.

You may also like

16 Inspiring Civil Rights Leaders You Should Know

15 Trusted Charities Fighting for Housing Rights

15 Examples of Gender Inequality in Everyday Life

11 Approaches to Alleviate World Hunger

15 Facts About Malala Yousafzai

12 Ways Poverty Affects Society

15 Great Charities to Donate to in 2024

15 Quotes Exposing Injustice in Society

14 Trusted Charities Helping Civilians in Palestine

The Great Migration: History, Causes and Facts

Social Change 101: Meaning, Examples, Learning Opportunities

Rosa Parks: Biography, Quotes, Impact

About the author, emmaline soken-huberty.

Emmaline Soken-Huberty is a freelance writer based in Portland, Oregon. She started to become interested in human rights while attending college, eventually getting a concentration in human rights and humanitarianism. LGBTQ+ rights, women’s rights, and climate change are of special concern to her. In her spare time, she can be found reading or enjoying Oregon’s natural beauty with her husband and dog.

Poverty as a Social Problem

This free essay on poverty as a social problem looks at a grave problem that exists in America and in the world. It provides reasons why people are experiencing poverty as well as some solutions.

Introduction

Literature review, poverty as a social problem: reflection, solutions to poverty as a social problem, social problems: poverty essay conclusion.

Society often perceives poverty as an individualistic issue, believing it is a consequence of bad decisions. That is, people themselves are responsible for the level of income and financial stability of households. However, the subject is much more complex as poverty also results from inadequate structuring of the country’s economy, distribution of goods, and other sectors, making it a social problem. Failure to build a system that would help citizens become financially stable results in various issues associated with crime levels, education, health care, and others. The government is the one that should work to solve them.

There are numerous studies and publications researching the reasons behind poverty. E. Royce (2019) tries to explain in his book how the existing economic system in the United States prevents citizens from reaching an adequate level of income and financial support. The main idea is that the current structure of how goods are distributed across the population does not benefit a large portion of it. Few rich individuals grow wealthier yearly, while millions struggle to find a stable job with a minimum wage.

The inequality created by the government’s failure to build a fair economic system results in a range of social problems. The idea of a poverty line as a measure of well-being has not changed much since the 1960s despite the obvious changes in consumption patterns (Royce, 2019). It is calculated as the sum required for purchasing essential items for living, which does not include modern commodities such as computers, mobile phones, and others.

As a result, low-income people become socially isolated since they do not possess things essential for the modern lifestyle, like social networks. They may be excluded from a community for not corresponding with the public image of active individuals. These mechanisms, combined with the dominant idea of the necessity to achieve success, push poor people away from social life. This factor comes together with the inability to receive proper health care and education services.

The literature also contains studies on how poverty affects the behavior of individuals. For instance, children exposed to life in a low-income household are more likely to develop adverse reactions in the future due to strain resulting from the inability to receive wished items (McFarland, 2017). When placed in a densely populated neighborhood, they may later cause legal problems, creating delinquent areas.

It is easy to predict the social issues that poor people face daily. They cannot receive proper health care services as they are usually costly. Moreover, many commercial organizations offering low-paid jobs traditionally based on customer service may prevent employees from taking sick leaves. As a result, people suffer from various illnesses without attending a hospital, fearing to lose a work placement.

Another issue is the inability of poor people to send their children to high-performing schools, which are expensive as a rule. This factor causes youth to continue living with the same income level as their parents since the absence of quality education prevents them from receiving a decent job. Moreover, children who cannot acquire goods valued by their peers are likely to adopt criminal behavior to achieve success since community norms and morals do not help this purpose.

Summarizing all the above said, it becomes evident that changing the existing economic structure on the governmental level is the most appropriate solution to the issue of poverty. There should be a strategy covering all the aspects affected by this problem. The goal is to increase the level of financial support for disadvantaged groups and give more opportunities for people to grow their income.

Firstly, the social sector should be transformed to meet the needs of all citizens. The government should increase the financing of schools so that all children will have access to quality education. Also, various programs should engage youth in activities after classes. Another step is to make health care affordable for everyone, and there should be no pressure on workers when they decide to take sick leaves.

Secondly, the structure of budget spending should be redesigned. It is evident that social support programs require much financing from taxes. One of the possible strategies is to make the government spend less on other sectors. Also, solving the issue of delinquent behavior among youth by advancing social support may cut costs on police functioning as there will be a lower need for services such as patrolling.

Poverty is a structural problem resulting from a country’s inadequate economic system. It creates various social issues associated with poor health care services, low-quality education, criminal activity, and others. Poverty is a complex subject that cannot be resolved shortly. However, one of the possible strategies is to provide better financial and social support for the population, which will create more opportunities for people to increase their income level.

McFarland, M. (2017). Poverty and problem behaviors across the early life course: The role of sensitive period exposure. Population Research & Policy Review , 36 (5), 739-760.

Royce, E. (2019). Poverty and power: The problem of structural inequality (3rd ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2021, June 14). Poverty as a Social Problem. https://studycorgi.com/poverty-as-a-social-problem/

"Poverty as a Social Problem." StudyCorgi , 14 June 2021, studycorgi.com/poverty-as-a-social-problem/.

StudyCorgi . (2021) 'Poverty as a Social Problem'. 14 June.

1. StudyCorgi . "Poverty as a Social Problem." June 14, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/poverty-as-a-social-problem/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Poverty as a Social Problem." June 14, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/poverty-as-a-social-problem/.

StudyCorgi . 2021. "Poverty as a Social Problem." June 14, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/poverty-as-a-social-problem/.

This paper, “Poverty as a Social Problem”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: November 8, 2023 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

108 Social Issues Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Social issues are complex and multifaceted problems that affect individuals, communities, and societies as a whole. These issues can range from poverty and inequality to discrimination and environmental degradation. Writing an essay on a social issue can be a daunting task, but it can also be a rewarding experience that allows you to explore and analyze important topics that impact the world around you.

To help you get started, here are 108 social issues essay topic ideas and examples that you can use as inspiration for your next writing assignment:

- The impact of social media on mental health

- Income inequality and its effects on society

- Police brutality and the Black Lives Matter movement

- The rise of fake news and its impact on democracy

- Gender inequality in the workplace

- Climate change and its effects on vulnerable communities

- The opioid crisis and its impact on communities

- The criminal justice system and racial disparities

- Homelessness and poverty in America

- The refugee crisis and global migration patterns

- LGBTQ+ rights and discrimination

- The rise of nationalism and its impact on global politics

- Gun control and mass shootings in America

- Environmental racism and its effects on marginalized communities

- The impact of globalization on developing countries

- Mental health stigma and access to treatment

- Cyberbullying and online harassment

- The #MeToo movement and sexual harassment in the workplace

- Access to healthcare and the rising cost of medical care

- The impact of technology on social relationships

- Food insecurity and hunger in America

- The effects of gentrification on low-income communities

- Disability rights and accessibility

- The criminalization of poverty and homelessness

- Human trafficking and modern-day slavery

- The impact of colonialism on indigenous communities

- The rise of authoritarianism and threats to democracy

- The education achievement gap and disparities in schools

- Mental health challenges facing college students

- The impact of social isolation on mental health

- The influence of religion on social norms and values

- The effects of gentrification on cultural identity

- The impact of social media on political discourse

- The role of activism in social change

- Access to clean water and sanitation in developing countries

- The impact of social media on body image and self-esteem

- The effects of income inequality on public health

- The criminalization of drug addiction and mental illness