The Weeders (1868) by Jules Breton. Courtesy the Met Museum, New York

The enchanted vision

Love is much more than a mere emotion or moral ideal. it imbues the world itself and we should learn to move with its power.

by Mark Vernon + BIO

Most ancient traditions, not only Christianity, picture the universe as an involution of divine love. It emanates from an origin that precedes frail beings. According to a hymn of creation in the Rig Veda, love is a fundamental presence: ‘In the beginning arose Love’ – or Kāma in Sanskrit: the love that sparks desire and vitalises consciousness through practices of yogic attention. In mystical Islamic traditions, love is similarly comprehended as an external power more than an emotion. For the Sufi, love forces believers, who are called lovers, out of themselves towards the Beloved, who is God. Even Stoicism was originally a discipline for discovering that the world is shaped by the Logos, or active word of creative love.

Today, this appreciation of reality, with its ‘built-in significance’ and ‘admirable design’, to quote C S Lewis, has become a ‘discarded image’. Any curious person enquiring of the universe now, and inspired by science, might feel themselves to be confronted by a reality of unknown or unknowable significance, or of no significance at all. Moreover, such doubt or confusion seems to be the price of rejecting a fanciful worldview for a scientific one. Apprehending the universe no longer consists of an awesome realisation that your mind fits the divine mind to some degree, but becomes one of uncertain, probing wonder: intellectual humility threatened by cognitive humiliation. Nor can anyone who is suffering turn to myths and rituals conveying the purposes of a love that exceeds and might contain their afflictions; they must bear their woe alone or, if they are lucky, in solidarity with similarly isolated others.

As a psychotherapist, I feel sure this feeling of existential seclusion exacerbates distress as well as other symptoms, like excessive consumption or spiritual discontent. Although the prevalence of suffering is given as a prime reason to reject the existence of divine love, paradoxically, I suspect its dismissal has made suffering worse. The healing power of having suffering recognised and understood, even when its causes remain, is a phenomenon that anyone engaged in caring will know. To be with suffering, which is more than just to witness it, is to be vulnerable, which can in turn bring an awareness that love and connection are basic and immovable. This is why people attest to finding God in suffering, regardless of rational objections. That mystery is central to any sure – as opposed to merely asserted – conviction that there is divine love.

Love is the formidable helpmate of our attention. This was something on which the philosopher Simone Weil , who famously took upon herself the sufferings of others , insisted – refusing, for example, to consume more that the miserable rations allowed her compatriots in France, when she was confined to a hospital bed in London in 1943. ‘By loving the order of the world we imitate the divine love which created this universe of which we are a part,’ she wrote.

Put another way, love was considered a universal force and a matter for knowledge, integral to the warp and weft of reality, not just a beneficent feeling or costly duty, practised at a personal level in acts of compassion or charity. When someone received love or gave it, they aligned themselves with the fundamental vitality pulsing through them and everything else. Sun and moon, mountains and seas, plants and birds, beasts of water and land. Everything participated in a common movement of love that would eventually return them to their source and sustainer.

Human beings could intentionally attend to this dynamic and collaborate with it. But, if not, if love is demoted from this role it becomes, at best, a moral ideal or emotion, exapted from evolution and sustained by the brain. Metaphysical agnosticism has replaced ‘ontological rootedness’, to borrow from the philosopher Simon May. Little wonder people feel disorientated or worse. To misquote R D Laing: someone who describes love as an epiphenomenon might be a great scientist, but someone who lives as if love is so will need a good psychiatrist.

But might the older notion of love be returning, as Weil and others have hoped? Might we be moving past the Romantics, who strove to comfort modern minds disturbed by what William Wordsworth called the ‘still, sad music of humanity’ because we are coming to know once more of that ‘holier love’? Might love be not just all you need, but something precisely required to account for who we are and all that is?

P rovocative hints that challenge a reflexive discounting of the enchanted vision, and which might spur a shift by reorientating attention and re-opening avenues of perception, can be drawn from moral philosophy, trends in contemporary biology and by considering the nature of intelligence. Consider first the moral issue. It begins with the observation that uncoupling love from its divine telos, and redescribing it solely in terms of evolved behaviours and all-too-human desires, has had unintended consequences. In particular, the secular turn has inverted the dictum that God is love, and made love a god, encouraging a sentimentalisation of love – a sappy deity for an otherwise godless age. Worse, the reversal excites a demand that is impossible to meet, by tasking humans with offering the unconditional love that, until a couple of centuries ago, would have been taken as coming only from God.

When unconditional love was known as a divine emanation, to claim that capacity for oneself, or to ask it of another, was a form of madness or idolatry. But now everyone is supposed to deliver and receive it, and overlook that we mortals are flawed and floundering. For such reasons, the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan proposed that, in a world without God, love is more honestly defined as a pact. ‘To love is, essentially, to wish to be loved,’ he said: in other words, I’ll give you what we can call love, if you offer me the same. The trouble is, such deals undermine and destroy love, as the philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch realised. Compromise and trade-offs are part of life, yes, but love’s whole point is to draw us beyond the transactional and mediocre. Consider the nature of creativity, Murdoch writes in The Sovereignty of Good (1970): ‘The true artist is obedient to a conception of perfection to which his work is constantly related and re-related in what seems an external manner.’ Love is likewise not fired by injunctions such as ‘Improve a little’ but rather by the call ‘Be perfect!’

The transcendent end to which love leads needn’t be called God, Murdoch felt, though it must be recognised as superhuman and excellent. Following Plato, she called it the Good, ‘the magnetic centre towards which love naturally moves,’ which also reveals the nature of love’s energy. ‘Love is the tension between the imperfect soul and the magnetic perfection which is conceived of as lying beyond it,’ she continued. That ‘beyond’ is the key thought here, with its intuition that what is most longed for is independent of us. Love is active in the psyche that hopes to know more than is currently even conceivable. To foreclose that transformation not only thwarts love, it is dehumanising; since to be human is to yearn for contact with more.

This ‘sovereignty of good’ is impressive, given the way it appears to call us, make demands upon us, and not let us go. But is that the same as affirming love’s transcendent actuality? Some biologists, it seems, are developing a worldview that invites the possibility.

Instead of phrases like ‘the mating season’, Darwin prefers ‘the season of love’

The move is happening in two steps: a first that can be characterised as bottom-up; a second, top-down. The bottom-up element stems from the revised picture of the living world that has been emerging in recent years. This new thinking has left behind the reductive view of life, characterised by Richard Dawkins as driven by selfish genes , to appreciate that cooperative, holistic and interdependent creaturely processes operate at and between all levels of life, from proteins and genes to the organism as a whole – and beyond, including ecological interactions with the so-called external environment.

It’s a fractal picture, driven by the explanatory power derived from considering how wholes matter quite as much as parts. Patterns of interaction that are present at the micro-level are amplified and transformed at the macro-level, with that in turn affecting the granular. Homologous parallels can be detected across species, too. What manifests as attraction and cooperation in simpler organisms becomes altruism and empathy among the more complex, with love capping the pyramid. Building on the foundations laid by biologists like Lynn Margulis, who championed symbiosis in evolution, and developed in books such as Interdependence (2015) by the biologist Kriti Sharma, the new picture changes the status of love from epiphenomenon to an emergent quality, springing from antecedent forms discernible within all sorts of interactions and behaviour; if love in all its fullness is present only in creatures like us, capable of forming intentions and consciously acting sacrificially, then love’s forerunners run all the way down the chain of living entities.

This, incidentally, is akin to the opinion of Charles Darwin. In The Descent of Man (1871), he discusses the ‘love-antics’ of birds, alongside using functional terms such as ‘display’, and instead of phrases like ‘the mating season’, he prefers ‘the season of love’. But he proposes something else, too. While nascent forms of love might evolve alongside the practicalities of survival – caring for offspring, for example – others, such as meeting aggression with kindness or loving enemies, would need ‘the aid of reason, instruction, and the love or fear of God.’ Which brings us to the top-down revision within biology. It shares the vision of an interplay of life processes across levels. But where the bottom-up biologists detect empathy and its precursors in the behaviour of a range of animals, the top-down revisionists are sceptical that complex psychological capacities like empathy exist in any creatures except humans.

In From Extraterrestrials to Animal Minds: Six Myths of Evolution (2022), the evolutionary biologist Simon Conway Morris examines the evidence for empathy in creatures from crows to chimps, and finds the data wanting. The matter is subtle and often raises hackles, but the crucial point is that context matters. The environment in which animals live shapes how they behave, as it does with humans, but for nonhuman animals context radically determines what behaviour is possible in the first place. Empathy is a case in point, because being moved by the suffering of a stranger, for instance, is morally significant when it can happen regardless of context, which no other animal appears capable of. ‘It is far from clear that our nearest cousins are anywhere near a moral dimension,’ Conway Morris concludes.

His alternative proposal, in line with Darwin’s conclusion about what it takes to love enemies, is that humans can access and align with moral verities, by virtue of being aware of a transcendent dimension that has not emerged, but been discovered. The human capacity for emotional self-regulation, say, and the ability to have sympathy with radically diverse perspectives, means that we can be open to the revelation of moral features of reality, top-down. The implication is that, while there are certainly analogues to love in other parts of the animal kingdom, these do not form complete pathways for evolutionary development. Rather, our ancestors have readied us for the perception of a love that pre-exists us.

Needless to say, the top-down conclusion is controversial, given the overtone of human exceptionalism, to say nothing of the implication that the creatures we love may not equally love us back. But the enquiry can be nudged along by extending the matter of what we know and turning to the question of how we know anything at all. In this, what we attend to is crucial.

C onsider a delightful anecdote told to me by the astronomer Bernard Carr. A former colleague of Stephen Hawking, Carr joined him at the premiere of the film about Hawking’s life, The Theory of Everything (2014). Carr was paying attention and, as they watched, an irony dawned in his mind. ‘The film was primarily about Stephen’s personal relationship with Jane, his first wife,’ he explained, ‘even though personal relationships and emotions, indeed mind itself, will probably never be covered by any Theory of Everything.’ In short, the film gave the lie to the aspiration to derive a complete account of existence from physics alone, and the reason is obvious: love is real and routinely experienced by human minds; but scientifically speaking, love can be evidenced only indirectly, by measuring the after-effects it leaves in its often-turbulent wake.

That first-hand quality is a feature of many types of knowledge. You can learn a lot about swimming by reading about swimming, but you can never learn how to swim from books. Even knowledge that can be captured in words or equations has a participatory dimension, of which the words and equations are tokens. Humans don’t only calculate but also comprehend, which the philosopher Mary Midgley in Wisdom, Information and Wonder (1989) described as arising from ‘a loving union’. Her point is that knowledge is never merely information amassed, like a digital dataset, but involves an intentional engagement with whatever the information might be about, that latter element being the revelatory issue. Intelligence rests on a dialogue with the world; flow is the feeling of immersion in the exchange. And it is love that invites us in.

Love is an active ingredient of our intelligence in another way. Consider the welter of sense-perceptions that bombard us all day, every day. The cognitive psychologist John Vervaeke argues that we can make sense of the avalanche of what we see, hear, smell, taste and touch through what he calls ‘relevance realisation’; we do not sort through the data, as an AI might, but care for some things above others, and thereby spontaneously spot what matters through the maelstrom. With the exception of the occasional sociopath, people are drawn by what is good, beautiful or true; these qualities organise things for us, even when we are not entirely clear what the good, beautiful or true might be. The ‘transcendentals’, as they were traditionally known, therefore have an objective character, even leading us over current horizons of perception to discover new insights. Weil put it like this: ‘The beauty of the world is the order of the world that is loved.’

When a river enters a larger body of water, the words of Indigenous languages allude to love

Suffering is integral to a searching intelligence, too. Breakthroughs often occur after breakdowns because wisdom tends to arise not with the accumulation of knowledge, but when an old mindset or worldview gives way – a process that is typically troubling and traumatic. But in that transition we are met, which is why a discovery may be greeted with a delighted exclamation: Eureka! Our minds can knowingly resonate with a wider intelligence, in a way that’s seemingly unavailable to other creatures. The pattern of seeds on a sunflower’s head may manifest a Fibonacci sequence, but humans can spot the mathematical and almost musical regularity – and, driven by love, delight in it.

My suspicion is that noticing the felt experience of our connection with the natural world, the associated moments of beauty and revelation, and concluding that the resulting joy is given as a gift, is part of the reason that Indigenous ways of knowing are reviving. ‘Indigenous peoples live in relational worldviews,’ explains Melissa Nelson, a professor at Arizona State University, whose heritage includes Anishinaabe, Cree, Métis and Norwegian. Nelson refers to the notion of ‘original instructions’, which is the array of rituals, myths and patterns around which Indigenous ways of life are organised, together aimed at deepening communion between humans and the more-than-human. She tells me: ‘There is a nurturing quality to the universe that is for us like a natural law, a universal principle that we can tap into: this field of love that is the matrix of the universe.’ The significance for environmental and ecological concerns is obvious.

What’s particularly striking is that analogues of love are perceived in the interactions of the so-called inanimate world, too. For example, when a river enters a larger body of water, the word used in several Indigenous languages alludes to love, Nelson says. Alternatively, viewing the planets or stars can be experienced as a relationship: receiving a quality of light that simultaneously lights up the soul – an insight remembered in words like ‘influence’, which originally meant stellar inflow.

To my mind, there are implications, here, for re-envisioning the place of humans in the world: part of the distinctiveness of our task is to bring this richness to mind. That can make a difference insofar as it increases the attention afforded to love. ‘We live in dire poverty in many places,’ Nelson continues, referring to spiritual as well as material need. ‘But we have this profound understanding of love being a cosmic universal force, that comes to us from the natural world and from the universe as a whole. That really strengthens us in terms of our embodiment and survival, and to thrive and regenerate.’

This kind of awareness might be called a participatory consciousness, and it’s been part and parcel of Western ways of knowing, too. The reciprocity has tended to be discounted since the birth of modern science because of the way dispassionate objectivity is valued, a stance that has brought gains. But perhaps for not much longer. ‘We do not obtain the most precious gifts by going in search of them but by waiting for them,’ Weil observed, because gifts are given in love and spotted by the right quality of attention.

The ramifications of reincorporating something of the premodern view are far reaching. Existential loneliness can be tried, found wanting, and reframed: it’s not all in your head. Or there is the feeling of wonder and connectedness that comes with awareness of the extraordinary nature of reality. The experience is offered a rationale: our minds fit the intelligence that shapes the world. Maybe, too, a love recognised as drawing us can invite us to stop trying to turn our corner of the universe into a tortured, technological paradise, and instead consider how we might design ways of life that deepen our attention, better harmonise with the planet and our nonhuman fellows, and even raise awareness of its divine wellspring. We might want to attend to the best once more, and bear what it takes to commune with this abundance, because there is a cosmic love and we can move with its power, along with everything else that is.

Technology and the self

Tomorrow people

For the entire 20th century, it had felt like telepathy was just around the corner. Why is that especially true now?

Roger Luckhurst

Ageing and death

Peregrinations of grief

A friend and a falcon went missing. In pain, I turned to ‘Slaughterhouse-Five’ – and found a new vision of sorrow and time

Nations and empires

Chastising little brother

Why did Japanese Confucians enthusiastically support Imperial Japan’s murderous conquest of China, the homeland of Confucius?

Shaun O’Dwyer

Mental health

The last great stigma

Workers with mental illness experience discrimination that would be unthinkable for other health issues. Can this change?

Pernille Yilmam

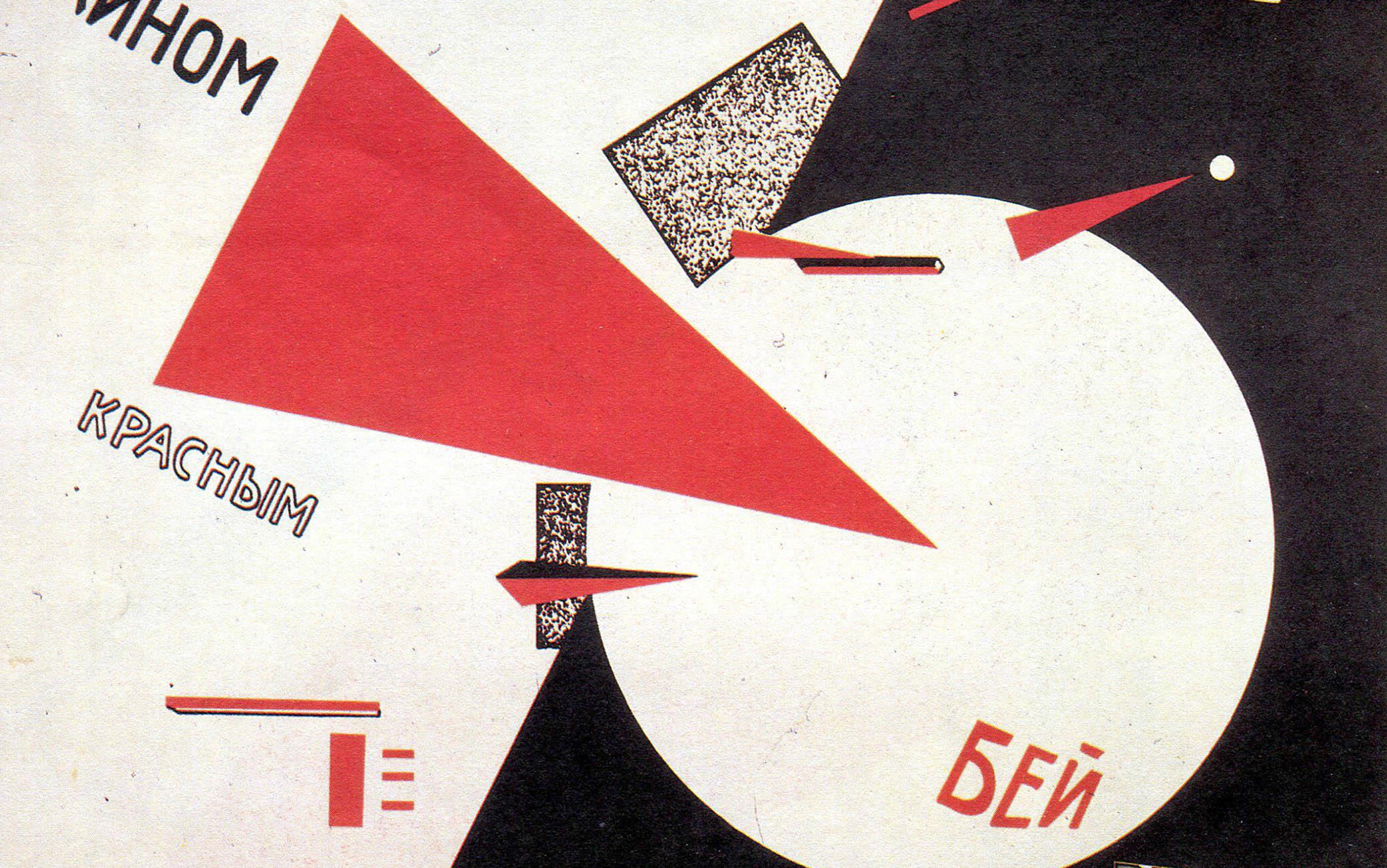

Quantum theory

Quantum dialectics

When quantum mechanics posed a threat to the Marxist doctrine of materialism, communist physicists sought to reconcile the two

Jim Baggott

A United States of Europe

A free and unified Europe was first imagined by Italian radicals in the 19th century. Could we yet see their dream made real?

Fernanda Gallo

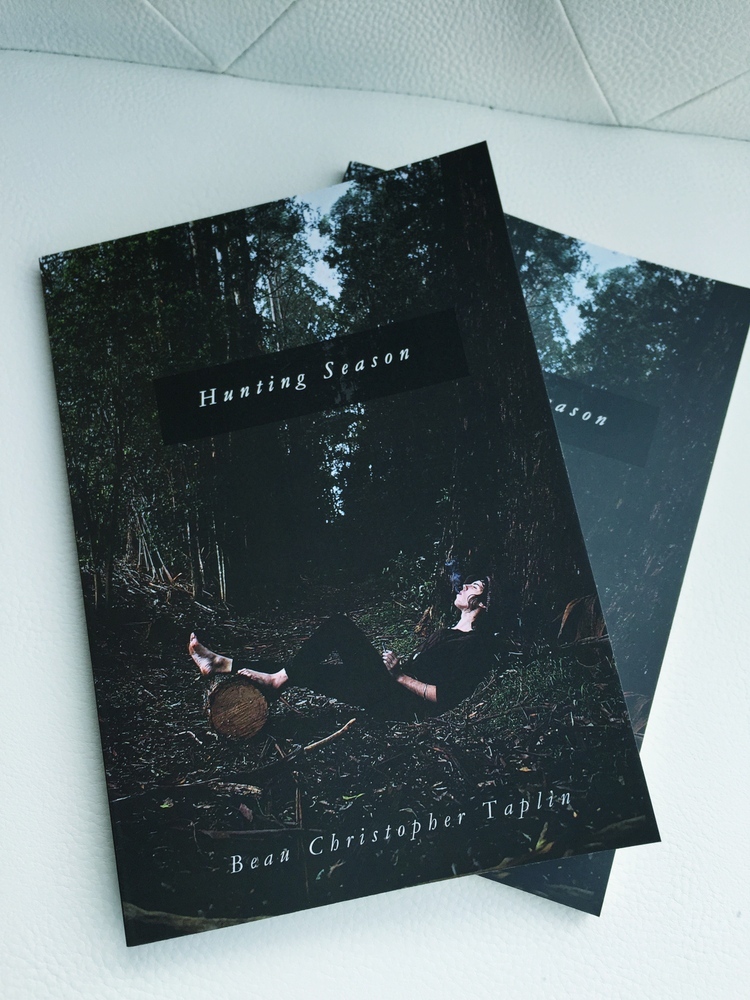

18 Of The Most Illuminating Literary Passages On Love, Life, And Romance By Beau Taplin

- https://thoughtcatalog.com/?p=484337

I can’t remember exactly when I first stumbled upon Beau Taplin’s writing. I suppose it was when I found myself in a used bookstore a few weeks ago with a copy of Hunting Season in my hands. Then I remembered, later, a friend from Australia had told me some time ago when we were in Nicaragua that he was one of her favorites. Beau’s work largely exists online, on posts that get reblogged thousands of times and on his website – the only place you can buy copies of his books. Here are a select few of some of the most beautiful and illuminating passages from his work.

“ Listen to me, your body is not a temple. Temples can be destroyed and desecrated. Your body is a forest—thick canopies of maple trees and sweet scented wildflowers sprouting in the under wood. You will grow back, over and over, no matter how badly you are devastated. ”

“ often, when we have a crush, when we lust for a person, we see only a small percentage of who they really are. the rest we make up for ourselves. rather than listen, or learn, we smother them in who we imagine them to be, what we desire for ourselves, we create little fantasies of people and let them grow in our hearts. and this is where the relationship fails. in time, the fiction we scribble onto a person falls away, the lies we tell ourselves unravel and soon the person standing in front of you is almost unrecognizable, you are now complete strangers in your own love. and what a terrible shame it is. my advice: pay attention to the small details of people, you will learn that the universe is far more spectacular an author than we could ever hope to be. ”, human beings are made of water–-, we were not designed to hold ourselves together, rather run freely like oceans like rivers, “ one day, whether you are 14, 28 or 65, you will stumble upon someone who will start a fire in you that cannot die. however, the saddest, most awful truth you will ever come to find – is they are not always with whom we spend our lives. ”, “ home is not where you are from, it is where you belong. some of us travel the whole world to find it. others, find it in a person.”, “ it’s 4am and i can’t remember how your voice sounds anymore. ”, “ it’s strange how your childhood sort of feels like forever. then suddenly you’re sixteen and the world becomes an hourglass and you’re watching the sand pile up at the wrong end. and you’re thinking of how when you were just a kid, your heartbeat was like a kick drum at a rock show, and now it’s just a time bomb ticking out. and it’s sad. and you want to forget about dying. but mostly you just want to forget about saying goodbye. ”, “ there was never going to be an “us” because you wanted to be missed more than you wanted to be loved. ”, “ it is a frightening thought, that in one fraction of a moment you can fall in the kind of love that takes a lifetime to get over. ”, “ the one thing i know for sure is that feelings are rarely mutual, so when they are, drop everything, forget belongings and expectations, forget the games, the two days between texts, the hard to gets because this is it, this is what the entire world is after and you’ve stumbled upon it by chance, by accident – so take a deep breath, take a step forward, now run, collide like planets in the system of a dying sun, embrace each other with both arms and let all the rules, the opinions and common sense crash down around you. because this is love kid, and it’s all yours. believe me, you’re in for one hell of a ride, after all – this is the one thing i know for sure. ”, “ the single greatest thing about love, in my experience, is the way it is doomed to pain and loss from its onset. whether it is the spouse that outlives their lover, or loses them to another, there is no escaping that most solemn of inevitabilities. that two people can commit themselves to all this sadness and heartache in the name of such brief happiness, the warm touch of familiar skin, the unrivalled pleasantness in waking up beside the same person you spent the entire night with in your dreams, is all the proof i need that insanity exists, and it is fucking beautiful. ”, “ it’s you. it’s been you for as long as i can remember. everyone else has just been another failed attempt at perfecting the art of pretending you’re not. i miss you. ”, “ i want somebody with a sharp intellect and a heart from hell. somebody with eyes like starfire and a mouth with a kiss like a bottomless well. but mostly i just want someone who will love me. when i do not know how to love myself. ”, “ do not call me perfect, a lie is never a compliment. call me an erratic damaged and insecure mess. then tell me that you love me for it. ”, “ the hours between 12am and 6am have a funny habit of making you feel like you’re either on top of the world, or under it. ”, “ my heart beats in almosts. it’s constantly in pursuit of those whom it desires but the moment it comes too close, it stops, turns, and bolts in the other direction. i hold onto what makes me miserable and i let the good things go. i’m self destructive.” i said. “it’s the way i’ve always been.” “and why do you think that is” “because it’s simpler to destroy something you love,” i said. “than it is to watch it leave. ”, “ i just want to be the person you miss at 3am. ”, “ she was unstoppable. not because she did not have failures or doubts, but because she continued on despite them. ”, for more from koty follow her on facebook ., koty neelis.

Former senior staff writer and producer at Thought Catalog.

Keep up with Koty on Twitter

More From Thought Catalog

Radiant Resilience: Navigating Beauty With Grace During A Crohn’s Flare-Up

5 Things That Actually Make A Woman “Wife Material” Only High-Quality Men Will Understand

Your Soulmate Will Never Do These 6 Toxic Things (But A Narcissist Will)

Love Without Limits: Dating With Inflammatory Bowel Disease

How To Create A More Friendly Workplace For Someone With Crohn’s Disease

7 Futuristic Sci-Fi Movies That Actually Predicted The Future

- Social Justice

- Environment

- Health & Happiness

- Get YES! Emails

- Teacher Resources

- Give A Gift Subscription

- Teaching Sustainability

- Teaching Social Justice

- Teaching Respect & Empathy

- Student Writing Lessons

- Visual Learning Lessons

- Tough Topics Discussion Guides

- About the YES! for Teachers Program

- Student Writing Contest

Follow YES! For Teachers

Eight brilliant student essays on what matters most in life.

Read winning essays from our spring 2019 student writing contest.

For the spring 2019 student writing contest, we invited students to read the YES! article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age” by Nancy Hill. Like the author, students interviewed someone significantly older than them about the three things that matter most in life. Students then wrote about what they learned, and about how their interviewees’ answers compare to their own top priorities.

The Winners

From the hundreds of essays written, these eight were chosen as winners. Be sure to read the author’s response to the essay winners and the literary gems that caught our eye. Plus, we share an essay from teacher Charles Sanderson, who also responded to the writing prompt.

Middle School Winner: Rory Leyva

High School Winner: Praethong Klomsum

University Winner: Emily Greenbaum

Powerful Voice Winner: Amanda Schwaben

Powerful Voice Winner: Antonia Mills

Powerful Voice Winner: Isaac Ziemba

Powerful Voice Winner: Lily Hersch

“Tell It Like It Is” Interview Winner: Jonas Buckner

From the Author: Response to Student Winners

Literary Gems

From A Teacher: Charles Sanderson

From the Author: Response to Charles Sanderson

Middle School Winner

Village Home Education Resource Center, Portland, Ore.

The Lessons Of Mortality

“As I’ve aged, things that are more personal to me have become somewhat less important. Perhaps I’ve become less self-centered with the awareness of mortality, how short one person’s life is.” This is how my 72-year-old grandma believes her values have changed over the course of her life. Even though I am only 12 years old, I know my life won’t last forever, and someday I, too, will reflect on my past decisions. We were all born to exist and eventually die, so we have evolved to value things in the context of mortality.

One of the ways I feel most alive is when I play roller derby. I started playing for the Rose City Rollers Juniors two years ago, and this year, I made the Rosebud All-Stars travel team. Roller derby is a fast-paced, full-contact sport. The physicality and intense training make me feel in control of and present in my body.

My roller derby team is like a second family to me. Adolescence is complicated. We understand each other in ways no one else can. I love my friends more than I love almost anything else. My family would have been higher on my list a few years ago, but as I’ve aged it has been important to make my own social connections.

Music led me to roller derby. I started out jam skating at the roller rink. Jam skating is all about feeling the music. It integrates gymnastics, breakdancing, figure skating, and modern dance with R & B and hip hop music. When I was younger, I once lay down in the DJ booth at the roller rink and was lulled to sleep by the drawl of wheels rolling in rhythm and people talking about the things they came there to escape. Sometimes, I go up on the roof of my house at night to listen to music and feel the wind rustle my hair. These unique sensations make me feel safe like nothing else ever has.

My grandma tells me, “Being close with family and friends is the most important thing because I haven’t

always had that.” When my grandma was two years old, her father died. Her mother became depressed and moved around a lot, which made it hard for my grandma to make friends. Once my grandma went to college, she made lots of friends. She met my grandfather, Joaquin Leyva when she was working as a park ranger and he was a surfer. They bought two acres of land on the edge of a redwood forest and had a son and a daughter. My grandma created a stable family that was missing throughout her early life.

My grandma is motivated to maintain good health so she can be there for her family. I can relate because I have to be fit and strong for my team. Since she lost my grandfather to cancer, she realizes how lucky she is to have a functional body and no life-threatening illnesses. My grandma tries to eat well and exercise, but she still struggles with depression. Over time, she has learned that reaching out to others is essential to her emotional wellbeing.

Caring for the earth is also a priority for my grandma I’ve been lucky to learn from my grandma. She’s taught me how to hunt for fossils in the desert and find shells on the beach. Although my grandma grew up with no access to the wilderness, she admired the green open areas of urban cemeteries. In college, she studied geology and hiked in the High Sierras. For years, she’s been an advocate for conserving wildlife habitat and open spaces.

Our priorities may seem different, but it all comes down to basic human needs. We all desire a purpose, strive to be happy, and need to be loved. Like Nancy Hill says in the YES! Magazine article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” it can be hard to decipher what is important in life. I believe that the constant search for satisfaction and meaning is the only thing everyone has in common. We all want to know what matters, and we walk around this confusing world trying to find it. The lessons I’ve learned from my grandma about forging connections, caring for my body, and getting out in the world inspire me to live my life my way before it’s gone.

Rory Leyva is a seventh-grader from Portland, Oregon. Rory skates for the Rosebuds All-Stars roller derby team. She loves listening to music and hanging out with her friends.

High School Winner

Praethong Klomsum

Santa Monica High School, Santa Monica, Calif.

Time Only Moves Forward

Sandra Hernandez gazed at the tiny house while her mother’s gentle hands caressed her shoulders. It wasn’t much, especially for a family of five. This was 1960, she was 17, and her family had just moved to Culver City.

Flash forward to 2019. Sandra sits in a rocking chair, knitting a blanket for her latest grandchild, in the same living room. Sandra remembers working hard to feed her eight children. She took many different jobs before settling behind the cash register at a Japanese restaurant called Magos. “It was a struggle, and my husband Augustine, was planning to join the military at that time, too.”

In the YES! Magazine article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” author Nancy Hill states that one of the most important things is “…connecting with others in general, but in particular with those who have lived long lives.” Sandra feels similarly. It’s been hard for Sandra to keep in contact with her family, which leaves her downhearted some days. “It’s important to maintain that connection you have with your family, not just next-door neighbors you talk to once a month.”

Despite her age, Sandra is a daring woman. Taking risks is important to her, and she’ll try anything—from skydiving to hiking. Sandra has some regrets from the past, but nowadays, she doesn’t wonder about the “would have, could have, should haves.” She just goes for it with a smile.

Sandra thought harder about her last important thing, the blue and green blanket now finished and covering

her lap. “I’ve definitely lived a longer life than most, and maybe this is just wishful thinking, but I hope I can see the day my great-grandchildren are born.” She’s laughing, but her eyes look beyond what’s in front of her. Maybe she is reminiscing about the day she held her son for the first time or thinking of her grandchildren becoming parents. I thank her for her time and she waves it off, offering me a styrofoam cup of lemonade before I head for the bus station.

The bus is sparsely filled. A voice in my head reminds me to finish my 10-page history research paper before spring break. I take a window seat and pull out my phone and earbuds. My playlist is already on shuffle, and I push away thoughts of that dreaded paper. Music has been a constant in my life—from singing my lungs out in kindergarten to Barbie’s “I Need To Know,” to jamming out to Taylor Swift’s “Blank Space” in sixth grade, to BTS’s “Intro: Never Mind” comforting me when I’m at my lowest. Music is my magic shop, a place where I can trade away my fears for calm.

I’ve always been afraid of doing something wrong—not finishing my homework or getting a C when I can do better. When I was 8, I wanted to be like the big kids. As I got older, I realized that I had exchanged my childhood longing for the 48 pack of crayons for bigger problems, balancing grades, a social life, and mental stability—all at once. I’m going to get older whether I like it or not, so there’s no point forcing myself to grow up faster. I’m learning to live in the moment.

The bus is approaching my apartment, where I know my comfy bed and a home-cooked meal from my mom are waiting. My mom is hard-working, confident, and very stubborn. I admire her strength of character. She always keeps me in line, even through my rebellious phases.

My best friend sends me a text—an update on how broken her laptop is. She is annoying. She says the stupidest things and loves to state the obvious. Despite this, she never fails to make me laugh until my cheeks feel numb. The rest of my friends are like that too—loud, talkative, and always brightening my day. Even friends I stopped talking to have a place in my heart. Recently, I’ve tried to reconnect with some of them. This interview was possible because a close friend from sixth grade offered to introduce me to Sandra, her grandmother.

I’m decades younger than Sandra, so my view of what’s important isn’t as broad as hers, but we share similar values, with friends and family at the top. I have a feeling that when Sandra was my age, she used to love music, too. Maybe in a few decades, when I’m sitting in my rocking chair, drawing in my sketchbook, I’ll remember this article and think back fondly to the days when life was simple.

Praethong Klomsum is a tenth-grader at Santa Monica High School in Santa Monica, California. Praethong has a strange affinity for rhyme games and is involved in her school’s dance team. She enjoys drawing and writing, hoping to impact people willing to listen to her thoughts and ideas.

University Winner

Emily Greenbaum

Kent State University, Kent, Ohio

The Life-Long War

Every morning we open our eyes, ready for a new day. Some immediately turn to their phones and social media. Others work out or do yoga. For a certain person, a deep breath and the morning sun ground him. He hears the clink-clank of his wife cooking low sodium meat for breakfast—doctor’s orders! He sees that the other side of the bed is already made, the dogs are no longer in the room, and his clothes are set out nicely on the loveseat.

Today, though, this man wakes up to something different: faded cream walls and jello. This person, my hero, is Master Chief Petty Officer Roger James.

I pulled up my chair close to Roger’s vinyl recliner so I could hear him above the noise of the beeping dialysis machine. I noticed Roger would occasionally glance at his wife Susan with sparkly eyes when he would recall memories of the war or their grandkids. He looked at Susan like she walked on water.

Roger James served his country for thirty years. Now, he has enlisted in another type of war. He suffers from a rare blood cancer—the result of the wars he fought in. Roger has good and bad days. He says, “The good outweighs the bad, so I have to be grateful for what I have on those good days.”

When Roger retired, he never thought the effects of the war would reach him. The once shallow wrinkles upon his face become deeper, as he tells me, “It’s just cancer. Others are suffering from far worse. I know I’ll make it.”

Like Nancy Hill did in her article “Three Things that Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” I asked Roger, “What are the three most important things to you?” James answered, “My wife Susan, my grandkids, and church.”

Roger and Susan served together in the Vietnam war. She was a nurse who treated his cuts and scrapes one day. I asked Roger why he chose Susan. He said, “Susan told me to look at her while she cleaned me up. ‘This may sting, but don’t be a baby.’ When I looked into her eyes, I felt like she was looking into my soul, and I didn’t want her to leave. She gave me this sense of home. Every day I wake up, she makes me feel the same way, and I fall in love with her all over again.”

Roger and Susan have two kids and four grandkids, with great-grandchildren on the way. He claims that his grandkids give him the youth that he feels slowly escaping from his body. This adoring grandfather is energized by coaching t-ball and playing evening card games with the grandkids.

The last thing on his list was church. His oldest daughter married a pastor. Together they founded a church. Roger said that the connection between his faith and family is important to him because it gave him a reason to want to live again. I learned from Roger that when you’re across the ocean, you tend to lose sight of why you are fighting. When Roger returned, he didn’t have the will to live. Most days were a struggle, adapting back into a society that lacked empathy for the injuries, pain, and psychological trauma carried by returning soldiers. Church changed that for Roger and gave him a sense of purpose.

When I began this project, my attitude was to just get the assignment done. I never thought I could view Master Chief Petty Officer Roger James as more than a role model, but he definitely changed my mind. It’s as if Roger magically lit a fire inside of me and showed me where one’s true passions should lie. I see our similarities and embrace our differences. We both value family and our own connections to home—his home being church and mine being where I can breathe the easiest.

Master Chief Petty Officer Roger James has shown me how to appreciate what I have around me and that every once in a while, I should step back and stop to smell the roses. As we concluded the interview, amidst squeaky clogs and the stale smell of bleach and bedpans, I looked to Roger, his kind, tired eyes, and weathered skin, with a deeper sense of admiration, knowing that his values still run true, no matter what he faces.

Emily Greenbaum is a senior at Kent State University, graduating with a major in Conflict Management and minor in Geography. Emily hopes to use her major to facilitate better conversations, while she works in the Washington, D.C. area.

Powerful Voice Winner

Amanda Schwaben

Wise Words From Winnie the Pooh

As I read through Nancy Hill’s article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” I was comforted by the similar responses given by both children and older adults. The emphasis participants placed on family, social connections, and love was not only heartwarming but hopeful. While the messages in the article filled me with warmth, I felt a twinge of guilt building within me. As a twenty-one-year-old college student weeks from graduation, I honestly don’t think much about the most important things in life. But if I was asked, I would most likely say family, friendship, and love. As much as I hate to admit it, I often find myself obsessing over achieving a successful career and finding a way to “save the world.”

A few weeks ago, I was at my family home watching the new Winnie the Pooh movie Christopher Robin with my mom and younger sister. Well, I wasn’t really watching. I had my laptop in front of me, and I was aggressively typing up an assignment. Halfway through the movie, I realized I left my laptop charger in my car. I walked outside into the brisk March air. Instinctively, I looked up. The sky was perfectly clear, revealing a beautiful array of stars. When my twin sister and I were in high school, we would always take a moment to look up at the sparkling night sky before we came into the house after soccer practice.

I think that was the last time I stood in my driveway and gazed at the stars. I did not get the laptop charger from

my car; instead, I turned around and went back inside. I shut my laptop and watched the rest of the movie. My twin sister loves Winnie the Pooh. So much so that my parents got her a stuffed animal version of him for Christmas. While I thought he was adorable and a token of my childhood, I did not really understand her obsession. However, it was clear to me after watching the movie. Winnie the Pooh certainly had it figured out. He believed that the simple things in life were the most important: love, friendship, and having fun.

I thought about asking my mom right then what the three most important things were to her, but I decided not to. I just wanted to be in the moment. I didn’t want to be doing homework. It was a beautiful thing to just sit there and be present with my mom and sister.

I did ask her, though, a couple of weeks later. Her response was simple. All she said was family, health, and happiness. When she told me this, I imagined Winnie the Pooh smiling. I think he would be proud of that answer.

I was not surprised by my mom’s reply. It suited her perfectly. I wonder if we relearn what is most important when we grow older—that the pressure to be successful subsides. Could it be that valuing family, health, and happiness is what ends up saving the world?

Amanda Schwaben is a graduating senior from Kent State University with a major in Applied Conflict Management. Amanda also has minors in Psychology and Interpersonal Communication. She hopes to further her education and focus on how museums not only preserve history but also promote peace.

Antonia Mills

Rachel Carson High School, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Decoding The Butterfly

For a caterpillar to become a butterfly, it must first digest itself. The caterpillar, overwhelmed by accumulating tissue, splits its skin open to form its protective shell, the chrysalis, and later becomes the pretty butterfly we all know and love. There are approximately 20,000 species of butterflies, and just as every species is different, so is the life of every butterfly. No matter how long and hard a caterpillar has strived to become the colorful and vibrant butterfly that we marvel at on a warm spring day, it does not live a long life. A butterfly can live for a year, six months, two weeks, and even as little as twenty-four hours.

I have often wondered if butterflies live long enough to be blissful of blue skies. Do they take time to feast upon the sweet nectar they crave, midst their hustling life of pollinating pretty flowers? Do they ever take a lull in their itineraries, or are they always rushing towards completing their four-stage metamorphosis? Has anyone asked the butterfly, “Who are you?” instead of “What are you”? Or, How did you get here, on my windowsill? How did you become ‘you’?

Humans are similar to butterflies. As a caterpillar

Suzanna Ruby/Getty Images

becomes a butterfly, a baby becomes an elder. As a butterfly soars through summer skies, an elder watches summer skies turn into cold winter nights and back toward summer skies yet again. And as a butterfly flits slowly by the porch light, a passerby makes assumptions about the wrinkled, slow-moving elder, who is sturdier than he appears. These creatures are not seen for who they are—who they were—because people have “better things to do” or they are too busy to ask, “How are you”?

Our world can be a lonely place. Pressured by expectations, haunted by dreams, overpowered by weakness, and drowned out by lofty goals, we tend to forget ourselves—and others. Rather than hang onto the strands of our diminishing sanity, we might benefit from listening to our elders. Many elders have experienced setbacks in their young lives. Overcoming hardship and surviving to old age is wisdom that they carry. We can learn from them—and can even make their day by taking the time to hear their stories.

Nancy Hill, who wrote the YES! Magazine article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” was right: “We live among such remarkable people, yet few know their stories.” I know a lot about my grandmother’s life, and it isn’t as serene as my own. My grandmother, Liza, who cooks every day, bakes bread on holidays for our neighbors, brings gifts to her doctor out of the kindness of her heart, and makes conversation with neighbors even though she is isn’t fluent in English—Russian is her first language—has struggled all her life. Her mother, Anna, a single parent, had tuberculosis, and even though she had an inviolable spirit, she was too frail to care for four children. She passed away when my grandmother was sixteen, so my grandmother and her siblings spent most of their childhood in an orphanage. My grandmother got married at nineteen to my grandfather, Pinhas. He was a man who loved her more than he loved himself and was a godsend to every person he met. Liza was—and still is—always quick to do what was best for others, even if that person treated her poorly. My grandmother has lived with physical pain all her life, yet she pushed herself to climb heights that she wasn’t ready for. Against all odds, she has lived to tell her story to people who are willing to listen. And I always am.

I asked my grandmother, “What are three things most important to you?” Her answer was one that I already expected: One, for everyone to live long healthy lives. Two, for you to graduate from college. Three, for you to always remember that I love you.

What may be basic to you means the world to my grandmother. She just wants what she never had the chance to experience: a healthy life, an education, and the chance to express love to the people she values. The three things that matter most to her may be so simple and ordinary to outsiders, but to her, it is so much more. And who could take that away?

Antonia Mills was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York and attends Rachel Carson High School. Antonia enjoys creative activities, including writing, painting, reading, and baking. She hopes to pursue culinary arts professionally in the future. One of her favorite quotes is, “When you start seeing your worth, you’ll find it harder to stay around people who don’t.” -Emily S.P.

Powerful Voice Winner

Isaac Ziemba

Odyssey Multiage Program, Bainbridge Island, Wash.

This Former State Trooper Has His Priorities Straight: Family, Climate Change, and Integrity

I have a personal connection to people who served in the military and first responders. My uncle is a first responder on the island I live on, and my dad retired from the Navy. That was what made a man named Glen Tyrell, a state trooper for 25 years, 2 months and 9 days, my first choice to interview about what three things matter in life. In the YES! Magazine article “The Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” I learned that old and young people have a great deal in common. I know that’s true because Glen and I care about a lot of the same things.

For Glen, family is at the top of his list of important things. “My wife was, and is, always there for me. My daughters mean the world to me, too, but Penny is my partner,” Glen said. I can understand why Glen’s wife is so important to him. She’s family. Family will always be there for you.

Glen loves his family, and so do I with all my heart. My dad especially means the world to me. He is my top supporter and tells me that if I need help, just “say the word.” When we are fishing or crabbing, sometimes I

think, what if these times were erased from my memory? I wouldn’t be able to describe the horrible feeling that would rush through my mind, and I’m sure that Glen would feel the same about his wife.

My uncle once told me that the world is always going to change over time. It’s what the world has turned out to be that worries me. Both Glen and I are extremely concerned about climate change and the effect that rising temperatures have on animals and their habitats. We’re driving them to extinction. Some people might say, “So what? Animals don’t pay taxes or do any of the things we do.” What we are doing to them is like the Black Death times 100.

Glen is also frustrated by how much plastic we use and where it ends up. He would be shocked that an explorer recently dived to the deepest part of the Pacific Ocean—seven miles!— and discovered a plastic bag and candy wrappers. Glen told me that, unfortunately, his generation did the damage and my generation is here to fix it. We need to take better care of Earth because if we don’t, we, as a species, will have failed.

Both Glen and I care deeply for our families and the earth, but for our third important value, I chose education and Glen chose integrity. My education is super important to me because without it, I would be a blank slate. I wouldn’t know how to figure out problems. I wouldn’t be able to tell right from wrong. I wouldn’t understand the Bill of Rights. I would be stuck. Everyone should be able to go to school, no matter where they’re from or who they are. It makes me angry and sad to think that some people, especially girls, get shot because they are trying to go to school. I understand how lucky I am.

Integrity is sacred to Glen—I could tell by the serious tone of Glen’s voice when he told me that integrity was the code he lived by as a former state trooper. He knew that he had the power to change a person’s life, and he was committed to not abusing that power. When Glen put someone under arrest—and my uncle says the same—his judgment and integrity were paramount. “Either you’re right or you’re wrong.” You can’t judge a person by what you think, you can only judge a person from what you know.”

I learned many things about Glen and what’s important in life, but there is one thing that stands out—something Glen always does and does well. Glen helps people. He did it as a state trooper, and he does it in our school, where he works on construction projects. Glen told me that he believes that our most powerful tools are writing and listening to others. I think those tools are important, too, but I also believe there are other tools to help solve many of our problems and create a better future: to be compassionate, to create caring relationships, and to help others. Just like Glen Tyrell does each and every day.

Isaac Ziemba is in seventh grade at the Odyssey Multiage Program on a small island called Bainbridge near Seattle, Washington. Isaac’s favorite subject in school is history because he has always been interested in how the past affects the future. In his spare time, you can find Isaac hunting for crab with his Dad, looking for artifacts around his house with his metal detector, and having fun with his younger cousin, Conner.

Lily Hersch

The Crest Academy, Salida, Colo.

The Phone Call

Dear Grandpa,

In my short span of life—12 years so far—you’ve taught me a lot of important life lessons that I’ll always have with me. Some of the values I talk about in this writing I’ve learned from you.

Dedicated to my Gramps.

In the YES! Magazine article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age,” author and photographer Nancy Hill asked people to name the three things that mattered most to them. After reading the essay prompt for the article, I immediately knew who I wanted to interview: my grandpa Gil.

My grandpa was born on January 25, 1942. He lived in a minuscule tenement in The Bronx with his mother,

father, and brother. His father wasn’t around much, and, when he was, he was reticent and would snap occasionally, revealing his constrained mental pain. My grandpa says this happened because my great grandfather did not have a father figure in his life. His mother was a classy, sharp lady who was the head secretary at a local police district station. My grandpa and his brother Larry did not care for each other. Gramps said he was very close to his mother, and Larry wasn’t. Perhaps Larry was envious for what he didn’t have.

Decades after little to no communication with his brother, my grandpa decided to spontaneously visit him in Florida, where he resided with his wife. Larry was taken aback at the sudden reappearance of his brother and told him to leave. Since then, the two brothers have not been in contact. My grandpa doesn’t even know if Larry is alive.

My grandpa is now a retired lawyer, married to my wonderful grandma, and living in a pretty house with an ugly dog named BoBo.

So, what’s important to you, Gramps?

He paused a second, then replied, “Family, kindness, and empathy.”

“Family, because it’s my family. It’s important to stay connected with your family. My brother, father, and I never connected in the way I wished, and sometimes I contemplated what could’ve happened. But you can’t change the past. So, that’s why family’s important to me.”

Family will always be on my “Top Three Most Important Things” list, too. I can’t imagine not having my older brother, Zeke, or my grandma in my life. I wonder how other kids feel about their families? How do kids trapped and separated from their families at the U.S.-Mexico border feel? What about orphans? Too many questions, too few answers.

“Kindness, because growing up and not seeing a lot of kindness made me realize how important it is to have that in the world. Kindness makes the world go round.”

What is kindness? Helping my brother, Eli, who has Down syndrome, get ready in the morning? Telling people what they need to hear, rather than what they want to hear? Maybe, for now, I’ll put wisdom, not kindness, on my list.

“Empathy, because of all the killings and shootings [in this country.] We also need to care for people—people who are not living in as good circumstances as I have. Donald Trump and other people I’ve met have no empathy. Empathy is very important.”

Empathy is something I’ve felt my whole life. It’ll always be important to me like it is important to my grandpa. My grandpa shows his empathy when he works with disabled children. Once he took a disabled child to a Christina Aguilera concert because that child was too young to go by himself. The moments I feel the most empathy are when Eli gets those looks from people. Seeing Eli wonder why people stare at him like he’s a freak makes me sad, and annoyed that they have the audacity to stare.

After this 2 minute and 36-second phone call, my grandpa has helped me define what’s most important to me at this time in my life: family, wisdom, and empathy. Although these things are important now, I realize they can change and most likely will.

When I’m an old woman, I envision myself scrambling through a stack of storage boxes and finding this paper. Perhaps after reading words from my 12-year-old self, I’ll ask myself “What’s important to me?”

Lily Hersch is a sixth-grader at Crest Academy in Salida, Colorado. Lily is an avid indoorsman, finding joy in competitive spelling, art, and of course, writing. She does not like Swiss cheese.

“Tell It Like It Is” Interview Winner

Jonas Buckner

KIPP: Gaston College Preparatory, Gaston, N.C.

Lessons My Nana Taught Me

I walked into the house. In the other room, I heard my cousin screaming at his game. There were a lot of Pioneer Woman dishes everywhere. The room had the television on max volume. The fan in the other room was on. I didn’t know it yet, but I was about to learn something powerful.

I was in my Nana’s house, and when I walked in, she said, “Hey Monkey Butt.”

I said, “Hey Nana.”

Before the interview, I was talking to her about what I was gonna interview her on. Also, I had asked her why I might have wanted to interview her, and she responded with, “Because you love me, and I love you too.”

Now, it was time to start the interview. The first

question I asked was the main and most important question ever: “What three things matter most to you and you only?”

She thought of it very thoughtfully and responded with, “My grandchildren, my children, and my health.”

Then, I said, “OK, can you please tell me more about your health?”

She responded with, “My health is bad right now. I have heart problems, blood sugar, and that’s about it.” When she said it, she looked at me and smiled because she loved me and was happy I chose her to interview.

I replied with, “K um, why is it important to you?”

She smiled and said, “Why is it…Why is my health important? Well, because I want to live a long time and see my grandchildren grow up.”

I was scared when she said that, but she still smiled. I was so happy, and then I said, “Has your health always been important to you.”

She responded with “Nah.”

Then, I asked, “Do you happen to have a story to help me understand your reasoning?”

She said, “No, not really.”

Now we were getting into the next set of questions. I said, “Remember how you said that your grandchildren matter to you? Can you please tell me why they matter to you?”

Then, she responded with, “So I can spend time with them, play with them, and everything.”

Next, I asked the same question I did before: “Have you always loved your grandchildren?”

She responded with, “Yes, they have always been important to me.”

Then, the next two questions I asked she had no response to at all. She was very happy until I asked, “Why do your children matter most to you?”

She had a frown on and responded, “My daughter Tammy died a long time ago.”

Then, at this point, the other questions were answered the same as the other ones. When I left to go home I was thinking about how her answers were similar to mine. She said health, and I care about my health a lot, and I didn’t say, but I wanted to. She also didn’t have answers for the last two questions on each thing, and I was like that too.

The lesson I learned was that no matter what, always keep pushing because even though my aunt or my Nana’s daughter died, she kept on pushing and loving everyone. I also learned that everything should matter to us. Once again, I chose to interview my Nana because she matters to me, and I know when she was younger she had a lot of things happen to her, so I wanted to know what she would say. The point I’m trying to make is that be grateful for what you have and what you have done in life.

Jonas Buckner is a sixth-grader at KIPP: Gaston College Preparatory in Gaston, North Carolina. Jonas’ favorite activities are drawing, writing, math, piano, and playing AltSpace VR. He found his passion for writing in fourth grade when he wrote a quick autobiography. Jonas hopes to become a horror writer someday.

From The Author: Responses to Student Winners

Dear Emily, Isaac, Antonia, Rory, Praethong, Amanda, Lily, and Jonas,

Your thought-provoking essays sent my head spinning. The more I read, the more impressed I was with the depth of thought, beauty of expression, and originality. It left me wondering just how to capture all of my reactions in a single letter. After multiple false starts, I’ve landed on this: I will stick to the theme of three most important things.

The three things I found most inspirational about your essays:

You listened.

You connected.

We live in troubled times. Tensions mount between countries, cultures, genders, religious beliefs, and generations. If we fail to find a way to understand each other, to see similarities between us, the future will be fraught with increased hostility.

You all took critical steps toward connecting with someone who might not value the same things you do by asking a person who is generations older than you what matters to them. Then, you listened to their answers. You saw connections between what is important to them and what is important to you. Many of you noted similarities, others wondered if your own list of the three most important things would change as you go through life. You all saw the validity of the responses you received and looked for reasons why your interviewees have come to value what they have.

It is through these things—asking, listening, and connecting—that we can begin to bridge the differences in experiences and beliefs that are currently dividing us.

Individual observations

Each one of you made observations that all of us, regardless of age or experience, would do well to keep in mind. I chose one quote from each person and trust those reading your essays will discover more valuable insights.

“Our priorities may seem different, but they come back to basic human needs. We all desire a purpose, strive to be happy, and work to make a positive impact.”

“You can’t judge a person by what you think , you can only judge a person by what you know .”

Emily (referencing your interviewee, who is battling cancer):

“Master Chief Petty Officer James has shown me how to appreciate what I have around me.”

Lily (quoting your grandfather):

“Kindness makes the world go round.”

“Everything should matter to us.”

Praethong (quoting your interviewee, Sandra, on the importance of family):

“It’s important to always maintain that connection you have with each other, your family, not just next-door neighbors you talk to once a month.”

“I wonder if maybe we relearn what is most important when we grow older. That the pressure to be successful subsides and that valuing family, health, and happiness is what ends up saving the world.”

“Listen to what others have to say. Listen to the people who have already experienced hardship. You will learn from them and you can even make their day by giving them a chance to voice their thoughts.”

I end this letter to you with the hope that you never stop asking others what is most important to them and that you to continue to take time to reflect on what matters most to you…and why. May you never stop asking, listening, and connecting with others, especially those who may seem to be unlike you. Keep writing, and keep sharing your thoughts and observations with others, for your ideas are awe-inspiring.

I also want to thank the more than 1,000 students who submitted essays. Together, by sharing what’s important to us with others, especially those who may believe or act differently, we can fill the world with joy, peace, beauty, and love.

We received many outstanding essays for the Winter 2019 Student Writing Competition. Though not every participant can win the contest, we’d like to share some excerpts that caught our eye:

Whether it is a painting on a milky canvas with watercolors or pasting photos onto a scrapbook with her granddaughters, it is always a piece of artwork to her. She values the things in life that keep her in the moment, while still exploring things she may not have initially thought would bring her joy.

—Ondine Grant-Krasno, Immaculate Heart Middle School, Los Angeles, Calif.

“Ganas”… It means “desire” in Spanish. My ganas is fueled by my family’s belief in me. I cannot and will not fail them.

—Adan Rios, Lane Community College, Eugene, Ore.

I hope when I grow up I can have the love for my kids like my grandma has for her kids. She makes being a mother even more of a beautiful thing than it already is.

—Ashley Shaw, Columbus City Prep School for Girls, Grove City, Ohio

You become a collage of little pieces of your friends and family. They also encourage you to be the best you can be. They lift you up onto the seat of your bike, they give you the first push, and they don’t hesitate to remind you that everything will be alright when you fall off and scrape your knee.

— Cecilia Stanton, Bellafonte Area Middle School, Bellafonte, Pa.

Without good friends, I wouldn’t know what I would do to endure the brutal machine of public education.

—Kenneth Jenkins, Garrison Middle School, Walla Walla, Wash.

My dog, as ridiculous as it may seem, is a beautiful example of what we all should aspire to be. We should live in the moment, not stress, and make it our goal to lift someone’s spirits, even just a little.

—Kate Garland, Immaculate Heart Middle School, Los Angeles, Calif.

I strongly hope that every child can spare more time to accompany their elderly parents when they are struggling, and moving forward, and give them more care and patience. so as to truly achieve the goal of “you accompany me to grow up, and I will accompany you to grow old.”

—Taiyi Li, Lane Community College, Eugene, Ore.

I have three cats, and they are my brothers and sisters. We share a special bond that I think would not be possible if they were human. Since they do not speak English, we have to find other ways to connect, and I think that those other ways can be more powerful than language.

—Maya Dombroskie, Delta Program Middle School, Boulsburg, Pa.

We are made to love and be loved. To have joy and be relational. As a member of the loneliest generation in possibly all of history, I feel keenly aware of the need for relationships and authentic connection. That is why I decided to talk to my grandmother.

—Luke Steinkamp, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio

After interviewing my grandma and writing my paper, I realized that as we grow older, the things that are important to us don’t change, what changes is why those things are important to us.

—Emily Giffer, Our Lady Star of the Sea, Grosse Pointe Woods, Mich.

The media works to marginalize elders, often isolating them and their stories, and the wealth of knowledge that comes with their additional years of lived experiences. It also undermines the depth of children’s curiosity and capacity to learn and understand. When the worlds of elders and children collide, a classroom opens.

—Cristina Reitano, City College of San Francisco, San Francisco, Calif.

My values, although similar to my dad, only looked the same in the sense that a shadow is similar to the object it was cast on.

—Timofey Lisenskiy, Santa Monica High School, Santa Monica, Calif.

I can release my anger through writing without having to take it out on someone. I can escape and be a different person; it feels good not to be myself for a while. I can make up my own characters, so I can be someone different every day, and I think that’s pretty cool.

—Jasua Carillo, Wellness, Business, and Sports School, Woodburn, Ore.

Notice how all the important things in his life are people: the people who he loves and who love him back. This is because “people are more important than things like money or possessions, and families are treasures,” says grandpa Pat. And I couldn’t agree more.

—Brody Hartley, Garrison Middle School, Walla Walla, Wash.

Curiosity for other people’s stories could be what is needed to save the world.

—Noah Smith, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio

Peace to me is a calm lake without a ripple in sight. It’s a starry night with a gentle breeze that pillows upon your face. It’s the absence of arguments, fighting, or war. It’s when egos stop working against each other and finally begin working with each other. Peace is free from fear, anxiety, and depression. To me, peace is an important ingredient in the recipe of life.

—JP Bogan, Lane Community College, Eugene, Ore.

From A Teacher

Charles Sanderson

Wellness, Business and Sports School, Woodburn, Ore.

The Birthday Gift

I’ve known Jodelle for years, watching her grow from a quiet and timid twelve-year-old to a young woman who just returned from India, where she played Kabaddi, a kind of rugby meets Red Rover.

One of my core beliefs as an educator is to show up for the things that matter to kids, so I go to their games, watch their plays, and eat the strawberry jam they make for the county fair. On this occasion, I met Jodelle at a robotics competition to watch her little sister Abby compete. Think Nerd Paradise: more hats made from traffic cones than Golden State Warrior ball caps, more unicorn capes than Nike swooshes, more fanny packs with Legos than clutches with eyeliner.

We started chatting as the crowd chanted and waved six-foot flags for teams like Mystic Biscuits, Shrek, and everyone’s nemesis The Mean Machine. Apparently, when it’s time for lunch at a robotics competition, they don’t mess around. The once-packed gym was left to Jodelle and me, and we kept talking and talking. I eventually asked her about the three things that matter to her most.

She told me about her mom, her sister, and her addiction—to horses. I’ve read enough of her writing to know that horses were her drug of choice and her mom and sister were her support network.

I learned about her desire to become a teacher and how hours at the barn with her horse, Heart, recharge her when she’s exhausted. At one point, our rambling conversation turned to a topic I’ve known far too well—her father.

Later that evening, I received an email from Jodelle, and she had a lot to say. One line really struck me: “In so many movies, I have seen a dad wanting to protect his daughter from the world, but I’ve only understood the scene cognitively. Yesterday, I felt it.”

Long ago, I decided that I would never be a dad. I had seen movies with fathers and daughters, and for me, those movies might as well have been Star Wars, ET, or Alien—worlds filled with creatures I’d never know. However, over the years, I’ve attended Jodelle’s parent-teacher conferences, gone to her graduation, and driven hours to watch her ride Heart at horse shows. Simply, I showed up. I listened. I supported.

Jodelle shared a series of dad poems, as well. I had read the first two poems in their original form when Jodelle was my student. The revised versions revealed new graphic details of her past. The third poem, however, was something entirely different.

She called the poems my early birthday present. When I read the lines “You are my father figure/Who I look up to/Without being looked down on,” I froze for an instant and had to reread the lines. After fifty years of consciously deciding not to be a dad, I was seen as one—and it felt incredible. Jodelle’s poem and recognition were two of the best presents I’ve ever received.

I know that I was the language arts teacher that Jodelle needed at the time, but her poem revealed things I never knew I taught her: “My father figure/ Who taught me/ That listening is for observing the world/ That listening is for learning/Not obeying/Writing is for connecting/Healing with others.”

Teaching is often a thankless job, one that frequently brings more stress and anxiety than joy and hope. Stress erodes my patience. Anxiety curtails my ability to enter each interaction with every student with the grace they deserve. However, my time with Jodelle reminds me of the importance of leaning in and listening.

In the article “Three Things That Matter Most in Youth and Old Age” by Nancy Hill, she illuminates how we “live among such remarkable people, yet few know their stories.” For the last twenty years, I’ve had the privilege to work with countless of these “remarkable people,” and I’ve done my best to listen, and, in so doing, I hope my students will realize what I’ve known for a long time; their voices matter and deserve to be heard, but the voices of their tias and abuelitos and babushkas are equally important. When we take the time to listen, I believe we do more than affirm the humanity of others; we affirm our own as well.

Charles Sanderson has grounded his nineteen-year teaching career in a philosophy he describes as “Mirror, Window, Bridge.” Charles seeks to ensure all students see themselves, see others, and begin to learn the skills to build bridges of empathy, affinity, and understanding between communities and cultures that may seem vastly different. He proudly teaches at the Wellness, Business and Sports School in Woodburn, Oregon, a school and community that brings him joy and hope on a daily basis.

From The Author: Response to Charles Sanderson

Dear Charles Sanderson,

Thank you for submitting an essay of your own in addition to encouraging your students to participate in YES! Magazine’s essay contest.

Your essay focused not on what is important to you, but rather on what is important to one of your students. You took what mattered to her to heart, acting upon it by going beyond the school day and creating a connection that has helped fill a huge gap in her life. Your efforts will affect her far beyond her years in school. It is clear that your involvement with this student is far from the only time you have gone beyond the classroom, and while you are not seeking personal acknowledgment, I cannot help but applaud you.

In an ideal world, every teacher, every adult, would show the same interest in our children and adolescents that you do. By taking the time to listen to what is important to our youth, we can help them grow into compassionate, caring adults, capable of making our world a better place.

Your concerted efforts to guide our youth to success not only as students but also as human beings is commendable. May others be inspired by your insights, concerns, and actions. You define excellence in teaching.

Get Stories of Solutions to Share with Your Classroom

Teachers save 50% on YES! Magazine.

Inspiration in Your Inbox

Get the free daily newsletter from YES! Magazine: Stories of people creating a better world to inspire you and your students.

Love: What Really Matters

A loving relationship can be an oasis in uncertain times. nurturing it requires attention, honesty, openness, vulnerability, and gratitude. here's a guide to important facets of intimacy..

By Psychology Today Contributors published August 19, 2020 - last reviewed on May 6, 2022

The Fundamentals of a Strong Relationship

by Amie M. Gordon, Ph.D.

Good relationships aren’t optional, and they aren’t what we do after we take care of everything else. Good relationships can determine who lives and who dies: One meta-analysis found that social relationships were more predictive of warding off mortality than quitting smoking or exercising. But it wasn’t just the presence of other people that mattered, it was the presence of supportive others—toxic relationships may be worse than no relationship at all.

In uncertain times, relationships matter even more. When the world is chaotic , we turn to our partners for security and stability. In a clever series of studies, Sandra Murray of the University at Buffalo and her colleagues found that on days when Google searches for terms like "terrorism," “recession,” “ global warming ,” “ racism ,” and “protest” were high in people’s zip codes, they were more likely to turn toward their closest relationships to satisfy their need for security, acceptance, and love. The world is certainly uncertain right now. A global pandemic, economic recession, and sociopolitical turmoil have been heaped onto all of our usual problems. But times of uncertainty can also represent opportunities for growth. Forced out of our usual routines, we can reassess and remember what is important. With global uncertainty, investing more in our relationships is a safe, practical, and healthy choice. We need love now, more than ever.

So how do we do it? First, we need to be open and honest with the people we care about. We need to share our thoughts and feelings with them. We need to ask for their support rather than always trying to go it alone. And we need to tell them what we appreciate about them.

Second, we need to be there for our partners. We need to listen and acknowledge what they are feeling. We need to provide support for them in both good times and in bad. We need to do it in ways that are helpful. And we need to allow ourselves to feel appreciated by them.