Ohio State nav bar

Ohio state navigation bar.

- BuckeyeLink

- Search Ohio State

Editorial Cartoons: An Introduction

What is an editorial cartoon.

- Newspaper editorial cartoons are graphic expressions of their creator’s ideas and opinions. In addition, the editorial cartoon usually, but not always, reflects the publication’s viewpoint.

- Editorial cartoons are based on current events. That means that they are produced under restricted time conditions in order to meet publication deadlines (often 5 or 6 per week).

- Editorial cartoons, like written editorials, have an educational purpose. They are intended to make readers think about current political issues.

- Editorial cartoons must use a visual and verbal vocabulary that is familiar to readers.

- Editorial cartoons are part of a business, which means that editors and/or managers may have an impact on what is published.

- Editorial cartoons are published in a mass medium, such as a newspaper, news magazine, or the Web.

- Editorial cartoons are tied to the technology that produces them, whether it is a printing press or the Internet. For printed cartoons, their size at the time of publication and their placement (on the front page, editorial page, or as the centerfold) affects their impact on readers. The addition of color may also change how readers respond to them.

- Editorial cartoons differ from comic strips. Editorial cartoons appear on the newspaper’s editorial or front page, not on the comics page. They usually employ a single-panel format and do not feature continuing characters in the way that comic strips do.

- Editorial cartoons are sometimes referred to as political cartoons, because they often deal with political issues.

What tools does the editorial cartoonist use to communicate ideas and opinions with readers?

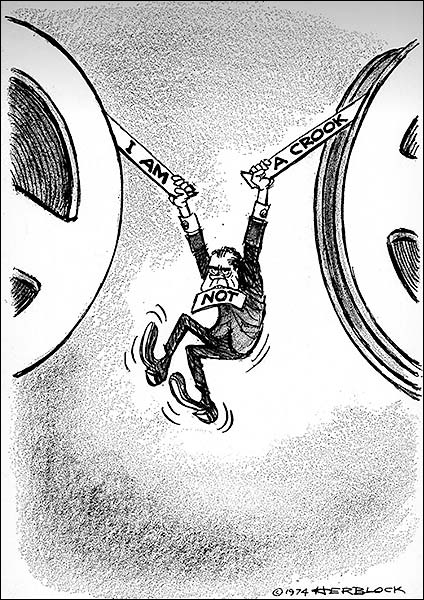

- Caricatures are drawings of public figures in which certain physical features are exaggerated. Caricatures of Richard M. Nixon often show him as needing to shave.

- Stereotypes are formulaic images used to represent particular groups. A stereotypical cartoon mother might have messy hair, wear an apron, and hold a screaming baby in her arms.

- Symbols are pictures that represent something else by tradition. A dove is a symbol for peace.

- Analogies are comparisons that suggest that one thing is similar to something else. The title of a popular song or film might be used by a cartoonist to comment on a current political event.

- Humor is the power to evoke laughter or to express what is amusing, comical or absurd.

How can an editorial cartoon be evaluated?

- A good editorial cartoon combines a clear drawing and good writing.

- A good editorial cartoon expresses a recognizable point-of-view or opinion.

- In the best instances, the cartoon cannot be read or understood by only looking at the words or only looking at the picture. Both the words and the pictures must be read together in order to understand the cartoonist’s message.

- Not all editorial cartoons are meant to be funny. Some of the most effective editorial cartoons are not humorous at all. Humor is only one tool available to editorial cartoonists.

Editorial cartoons provide a window into history by showing us what people were thinking and talking about at a given time and place. Today’s editorial cartoons will provide the same record of our own time.

- Grant Programs

- Defending Basic Freedoms

- Pathways Out of Poverty

- Encouraging Citizen Involvement

- Scholarships

- Scholarship Highlights

- The Scholarship Application

- Videos / Testimonials

- Prize & Lecture

- Prize Winners

- The Lectures

- Rules & Eligibility

- Press Releases

Editorial Cartooning

- Scholastic Art & Writing Awards

- How to Analyze an Editorial Cartoon

- Lesson Plans

- The Cartoon

- Traveling Exhibits

- Report on Editorial Cartooning

- The Foundation

- Foundation News

- Board of Directors

- Herblock Gallery

- Library of Congress

- Order Cartoon Reprints

- Washington Post

- Documentary

An Editorial Cartoon, also known as a political cartoon, is an illustration containing a commentary that usually relates to current events or personalities. An artist who draws such images is known as an editorial cartoonist. - www.en.wikipedia.org

“No cartoonist or commentator in America did more to educate and inform the American public than Herblock. Political cartoons represent the freedom of expression inherent in American democracy, a powerful symbol of its strength and resilience. In the new millennium Herblock's drawings forcefully bring back the principal issues and events that shaped our world during the past century.”

—from the Preface by James H. Billington, Librarian of Congress for HERBLOCK: The Life and Work of the Great Political Cartoonist (published 2009)

“Herb Block indelibly depicted villains and rogues, corrupt officials and corporate polluters, racists and demagogues. He relentlessly attacked the gun lobby, segregationists, government secrecy, abuses of power, religious bigots, sexism, racism and, always, public hipocrisy wherever and whenever it arose. At the same time he ardently fought for civil liberties, for the poor and the oppressed. He always stood for the underdog, and for the everyman and everywoman among us trapped in, or frustrated by, the ever more complicate nature of modern life.”

—Haynes Johnson, The Age of Herblock. Excerpted from HERBLOCK: The Life and Work of the Great Political Cartoonist.

The first editorial cartoon was drawn by Benjamin Franklin, and appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette on May 9, 1754 entitled "Join, or Die." Franklin saw the colonies as dangerously fragmented, and hoped, with the cartoon and an article, to convince colonists they would have great power if they united. Franklin used symbolism and labeling to present an opinion based on current events and politics. Cartoons throughout history have made use of similar techniques of caricature, analogy, irony, juxtaposition and exaggeration to educate and influence their audience.

Editorial cartoons provide a rich landscape for educators to teach any number of subjects (English, History, Social Studies, Art, ect..) while engaging students to use critical thinking in any number of learning styles (cooperative, inquiry-based, individualized, ect..). We provide our own lesson plans and links to others, for teachers and students to teach and learn from the art of editorial cartooning.

In the meantime, look at the Herblock Prize winners' work and other current editorial cartoonists , as well as Herblock's, to get excited about the possibilities.

Video - How to Make an Editorial Cartoon - The Learning Network by The New York Times

The Conscience of the Country: Herblock's Influencial Ink Bottle - Winner of 2014 National History Day, Senior Group Website by Aditi Dinakar and Andrew Boge from Johnston High School in Johnston, Iowa

Lesson Plans - including a collaboration between Scholastic Inc and The Herb Block Foundation

The Cartoon - an essay by Herb Block

About Herb Block

Our Commitment

The Herb Block Foundation is committed to defending the basic freedoms guaranteed all Americans, combating all forms of discrimination and prejudice and improving the conditions of the poor and underprivileged through the creation or support of charitable and educational programs with the same goals.

The Foundation is also committed to providing educational opportunity to deserving students through post-secondary education scholarships and to promoting editorial cartooning through continued research. All efforts of the Foundation shall be in keeping with the spirit of Herblock, America's great cartoonist in his life long fight against abuses by the powerful.

Editorial Cartoons: The Easiest Way To Make Editorial Cartoons, FREE

Editorial cartoons always catch the eye. When you get them in an email — you stop what you’re doing and take a peak. When you see one on Facebook or Twitter — you stop scrolling and start laughing.

They’re what you share, what you love, and what you can’t get enough of. But the biggest problem with editorial cartoons is that they’re limited to professionals. Imagine if you had an idea to make some hilarious ones yourself – how on earth would you be able to make one?

Here’s the great news: With Powtoon — you can make as many editorial cartoons as your heart desires. You can make one to stand out on your next blog post, in an email to your subscribers, as an in-office joke or just to share with your social media followers.

How To Make Editorial Cartoons With Powtoon… In Just 3 Steps

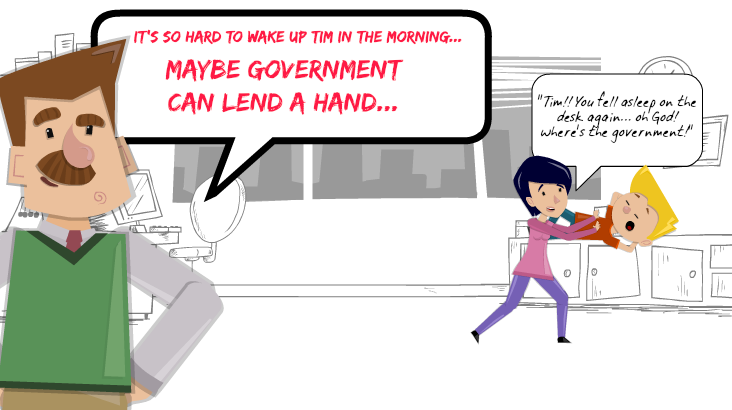

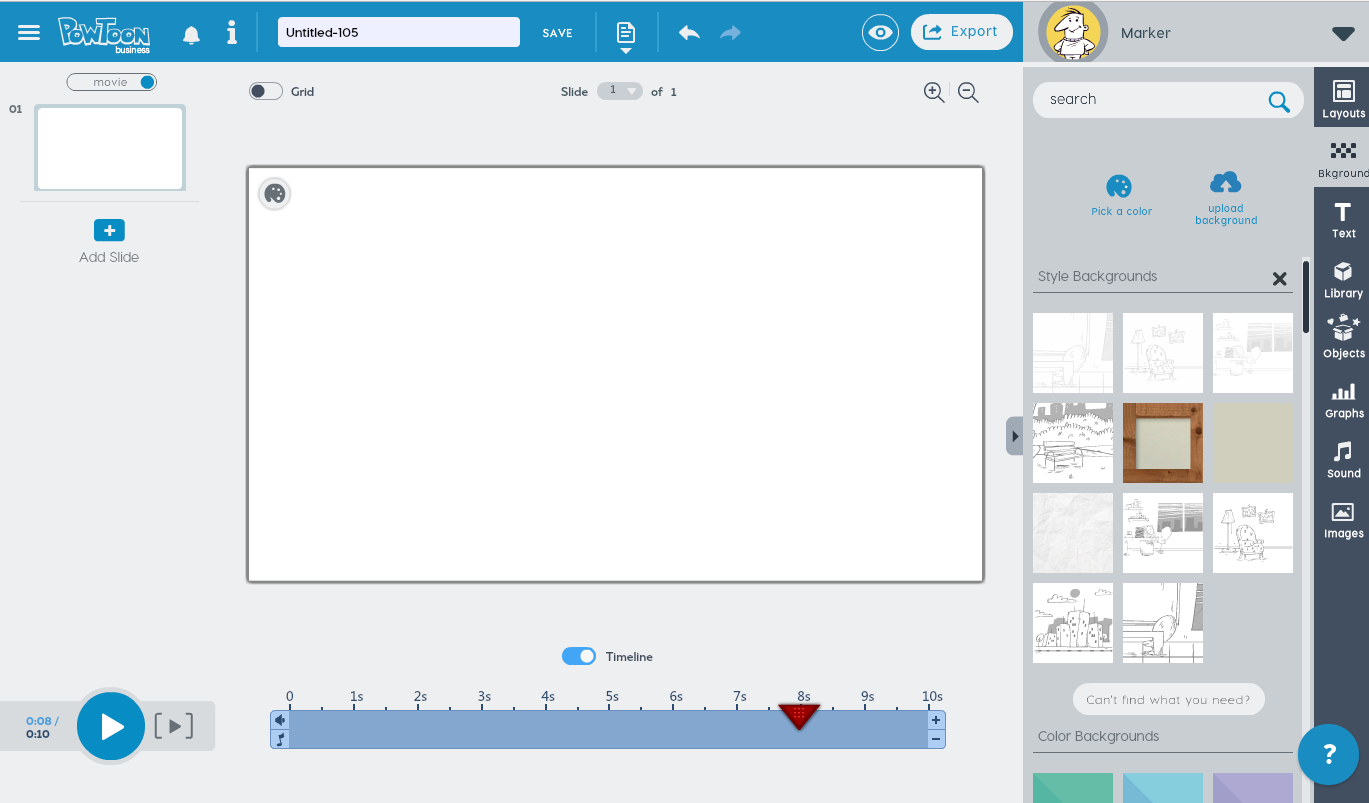

1. choose your scene.

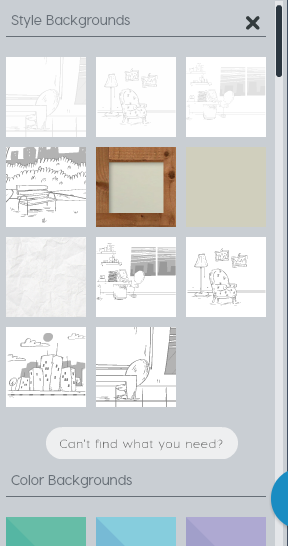

For the first one I did, I chose a background found in the ‘Marker’ style, to set the scene. So, inside of Powtoon Studio (as you see below) just click “Backgrounds” on the side panel and you’ll discover a library full of gorgeous backgrounds to choose from.

Then, just click the background you want and…

…boom, it appears:

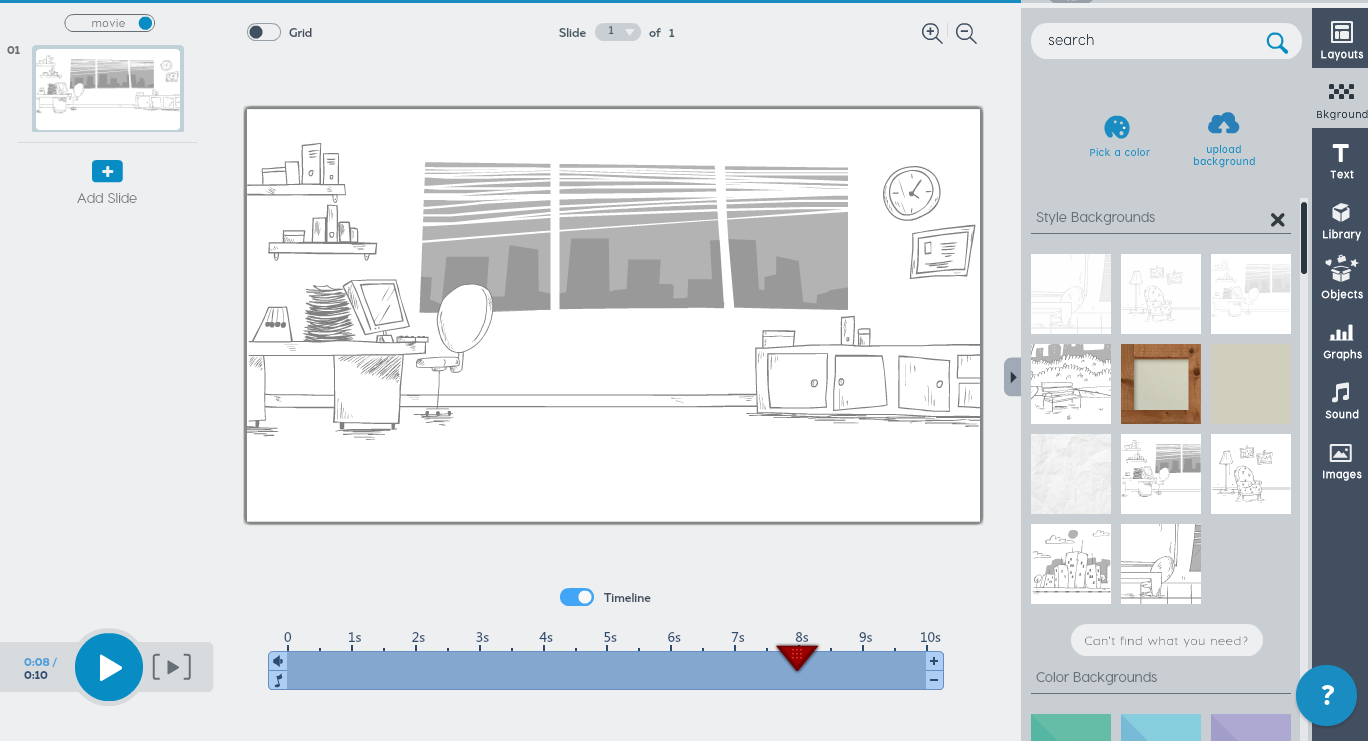

2. Choose your character

Once you choose your background for your scene, the next step is to choose a character. All you have to do is click on the ‘Animated Character’ or ‘Character’ menu and choose the one you want. I chose the Animated Character above, from the ‘Paper Cut’ template.

3. Choose Your Text

I chose to use a ‘Quote Box’ which you can find in the ‘Objects’ section in the sidebar. Then I clicked to add ‘Text’ on the menu at the top and you can edit your text instantly.

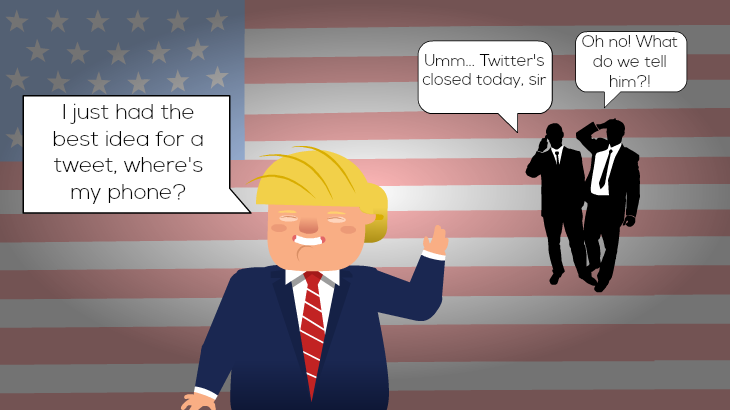

Always Be Timely — Editorial Cartoons in a Snap

Here’s another quick one I made — just by using the Donald Trump character we created for the 2016 election campaign. I also chose a background appropriate for a president. You can create any editorial cartoon you like, using it in as many creative and strategic ways you can dream of 🙂

We all know how quickly the news can change. The thing that was timely and engaging a week ago might be all but forgotten today. So use this easy hack to churn out tons of timely and relevant editorial cartoons for your audience. They’ll think you have a team of artists backing you up!

These are the only 3 steps you need to make editorial cartoons with Powtoon, for FREE.

We have a library full of characters, backgrounds, fonts, hundreds of props and objects and a ton more for you to use. So go on an unleash your own creative genius with Powtoon right now. Click here to sign up for your free account and start making as many editorial cartoons as your heart desires 🙂

This post has been updated for clarity and accuracy.

- Latest Posts

Nick Liebman

Latest posts by nick liebman ( see all ).

- Course Authoring & Video in 2022: How to Build a Stronger Remote Work Learning Culture - January 25, 2022

- When Is Black Friday?! A Beginner’s Guide to Video Ads [3 Quick Steps] - September 8, 2021

- Turn Static Canva Designs into Video in Just 3 Steps - January 25, 2021

- What Happened in 2020? The Year of Visual Communication - December 14, 2020

You’ll Change Your Marketing Strategy After Seeing This!

How to Increase Video Retention Rates with Storytelling [Video Influencer Interview]

Viral Video Marketing: Make Your Mark On The World

How to Write Content For B2B Marketing on LinkedIn

Embedding Social Media Content on Your Website: The Why and How

3 Psychological Techniques To Get People Addicted To Your Videos

Thank you for your interest in Powtoon Enterprise!

A solution expert will be in touch with you soon via phone or email.

Request a demo

By submitting, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Finance and Business

How to Analyze Political Cartoons

Last Updated: January 16, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was reviewed by Gerald Posner . Gerald Posner is an Author & Journalist based in Miami, Florida. With over 35 years of experience, he specializes in investigative journalism, nonfiction books, and editorials. He holds a law degree from UC College of the Law, San Francisco, and a BA in Political Science from the University of California-Berkeley. He’s the author of thirteen books, including several New York Times bestsellers, the winner of the Florida Book Award for General Nonfiction, and has been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in History. He was also shortlisted for the Best Business Book of 2020 by the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing. There are 8 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 581,165 times.

Political cartoons use imagery and text to comment on a contemporary social issue. They may contain a caricature of a well-known person or an allusion to a contemporary event or trend. [1] X Research source By examining the image and text elements of the cartoon, you can start to understand its deeper message and evaluate its effectiveness.

Examining the Image and Text

Common Symbols in Political Cartoons

Uncle Sam or an eagle for the United States John Bull, Britannia or a lion for the United Kingdom A beaver for Canada A bear for Russia A dragon for China A sun for Japan A kangaroo for Australia A donkey for the US Democratic Party An elephant for the US Republican Party

- Many political cartoonists will include caricatures of well-known politicians, which means they’ll exaggerate their features or bodies for humor, easy identification, or to emphasize a point. For example, an artist might make an overweight politician even larger to emphasize their greed or power.

- For example, if the cartoonist shows wealthy people receiving money while poorer people beg them for change, they’re using irony to show the viewer how wrong they believe the situation to be.

- For example, the stereotype of a fat man in a suit often stands for business interests.

- If you’re analyzing a historical political cartoon, take its time period into account. Was this kind of stereotype the norm for this time? How is the artist challenging or supporting it?

Text in Political Cartoons

Labels might be written on people, objects or places. For example, a person in a suit might be labeled “Congress,” or a briefcase might be labeled with a company’s name.

Text bubbles might come from one or more of the characters to show dialogue. They’re represented by solid circles or boxes around text.

Thought bubbles show what a character is thinking. They usually look like small clouds.

Captions or titles are text outside of the cartoon, either below or above it. They give more information or interpretation to what is happening in the cartoon itself.

- For example, a cartoon about voting might include a voting ballot with political candidates and celebrities, indicating that more people may be interested in voting for celebrities than government officials.

- The effectiveness of allusions often diminishes over time, as people forget about the trends or events.

Analyzing the Issue and Message

- If you need help, google the terms, people, or places that you recognize and see what they’ve been in the news for recently. Do some background research and see if the themes and events seem to connect to what you saw in the cartoon.

- The view might be complex, but do your best to parse it out. For example, an anti-war cartoon might portray the soldiers as heroes, but the government ordering them into battle as selfish or wrong.

- For example, a political cartoon in a more conservative publication will convey a different message, and use different means of conveying it, than one in a liberal publication.

Rhetorical Devices

Pathos: An emotional appeal that tries to engage the reader on an emotional level. For example, the cartoonist might show helpless citizens being tricked by corporations to pique your pity and sense of injustice.

Ethos: An ethical appeal meant to demonstrate the author’s legitimacy as someone who can comment on the issue. This might be shown through the author’s byline, which could say something like, “by Tim Carter, journalist specializing in economics.”

Logos: A rational appeal that uses logical evidence to support an argument, like facts or statistics. For example, a caption or label in the cartoon might cite statistics like the unemployment rate or number of casualties in a war.

- Does it make a sound argument?

- Does it use appropriate and meaningful symbols and words to convey a viewpoint?

- Do the people and objects in the cartoon adequately represent the issue?

Community Q&A

- Keep yourself informed on current events in order to more clearly understand contemporary political cartoons. Thanks Helpful 6 Not Helpful 0

- If you are having trouble discerning the meaning of a political cartoon, try talking with friends, classmates, or colleagues. Thanks Helpful 3 Not Helpful 3

- Historical context: When?

- Intended audience: For who?

- Point of view: Author's POV.

- Purpose: Why?

- Significance: For what reason?

- Political cartoons are oftentimes meant to be funny and occasionally disregard political correctness. If you are offended by a cartoon, think about the reasons why a cartoonist would use certain politically incorrect symbols to describe an issue. Thanks Helpful 14 Not Helpful 2

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://teachinghistory.org/teaching-materials/teaching-guides/21733

- ↑ https://teachinghistory.org/sites/default/files/2018-08/Cartoon_Analysis_0.pdf

- ↑ https://www.metaphorandart.com/articles/exampleirony.html

- ↑ https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/globalconnections/mideast/educators/types/lesson3.html

- ↑ https://www.writerswrite.co.za/the-12-common-archetypes/

- ↑ https://www.lsu.edu/hss/english/files/university_writing_files/item35402.pdf

- ↑ https://www.mindtools.com/axggxkv/paraphrasing-and-summarizing

- ↑ http://www.ysmithcpallen.com/sites/default/files/Analyzing-and-Interpreting-Political-Cartoons1.ppt

About This Article

To analyze political cartoons, start by looking at the picture and identifying the main focus of the cartoon, which will normally be exaggerated for comic effect. Then, look for popular symbols, like Uncle Sam, who represents the United States, or famous political figures. Make note of which parts of the symbols are exaggerated, and note any stereotypes that the artists is playing with. Once you’ve identified the main point, look for subtle details that create the rest of the story. For tips on understanding and recognizing persuasive techniques used in illustration, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Sep 5, 2017

Did this article help you?

Ben Garrison

Jan 1, 2018

Julian Goytia

Nov 4, 2016

Jordy Mc'donald

Oct 29, 2016

Shane Connell

Jun 9, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

Advanced Search (Items only)

- Browse Exhibits

- Browse Items

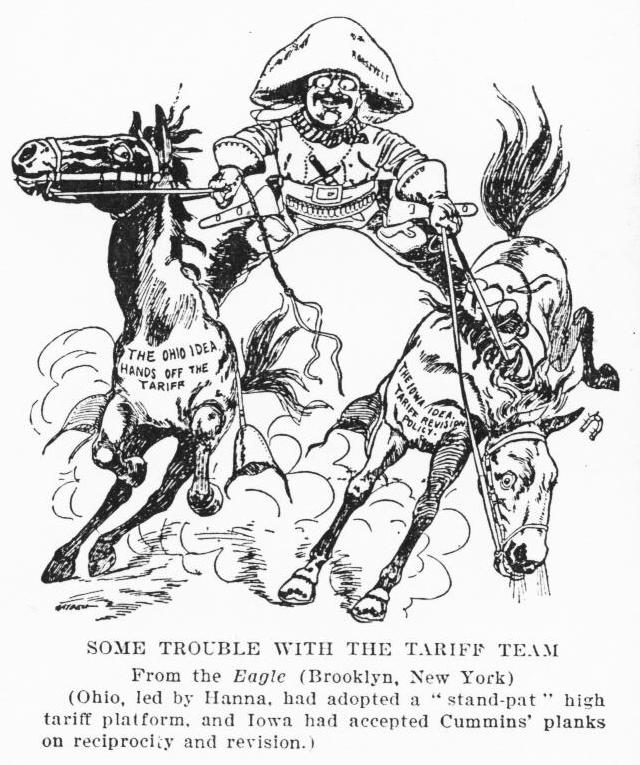

Brief History of the Editorial Cartoon

Melissa corcoran hopkins community member and donor.

This historical sketch of the editorial cartoon considers terminology; evolving technology; the risks, rewards, and restrictions in news media; and the reach and role of the art form today.

Terminology

Editorial and political cartoons derive from satirical art, which may be as old as humanity. Some prehistoric cave art features irreverent human forms (Hess, p. 15); in ancient Egypt an anonymous artist mocked King Tutankhamen’s unpopular father-in-law; later artists criticized Cleopatra (Danjoux 2007); Greek plays and vases anthropomorphized human excess, as in lecherous satyrs; Roman art lampooned behaviors in real or mythical characters like Bacchus, the debauched wine god; in Pompeii, a Roman soldier drew graffiti on his barracks wall mocking a centurion (Hess, p.15); in ancient India, caricatures attacked political elites as well as Hindu gods (Danjoux 2007); Gothic gargoyles decorating medieval churches present caricatures exaggerating human traits.

Whatever the label or medium, satire questions motives, skewers hubris, and invites others to do the same.

In art history, the word cartoon is a noun or verb tracing to the Renaissance, deriving from the Italian word la carta for paper or map. An artist made a full-scale preparatory sketch, or cartoon, for any medium: sculpture, tapestry, mosaic, stained glass work, or painting. Michelangelo made cartoons before painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling in Rome.

The Oxford English Dictionary (1971) records a reference to the noun in 1863 as “a paper comic of current events,” and as a verb in 1887,” to caricature or to hold up to ridicule.”

In modern journalism, the editor of the Columbia Encyclopedia , Paul Lagasse, defines a cartoon as “a single humorous or satirical drawing, employing distortion for emphasis, often accompanied by a caption.” The editorial – or political – cartoon relies on caricature, stock characters, and cultural symbols to become a “propaganda weapon with social implications” (p.486) — a tool to influence public opinion. The measure of a cartoon’s success is the force of its idea, rendered clearly and resonating beyond its subject of the moment. The artistry is secondary to the message, which should lay bare behavior and character (Press, p.19). In the 18th century, Johnathan Swift wrote advice in a poem to fellow-satirist William Hogarth, “Draw them so that we may trace/All the soul in every face” (Hess, p.16).

Artists were always free to draw their own ideas on hand-printed single sheet cartoons. They were independent and could reach a limited and random audience, yet their offended victims could easily destroy single sheets. The 15th century brought a pivotal change: the Gutenberg printing press in Mainz, Germany facilitated printing large volumes of news sheets and images, instead of one painstaking original. The resulting term, the press, became an agent of mass communication and signaled danger to those in power.

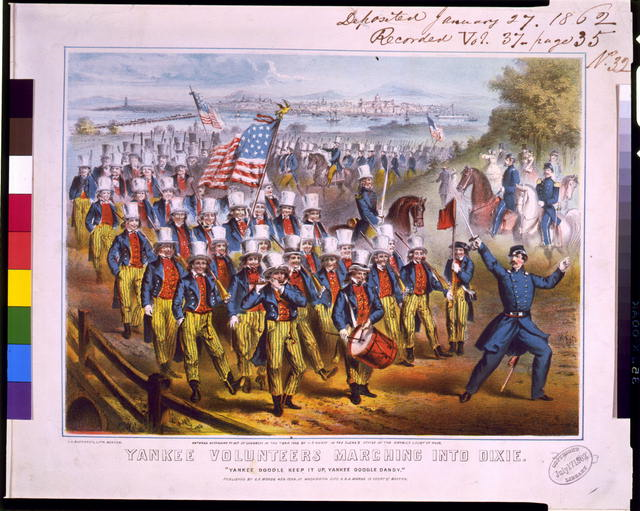

In Renaissance times, the press produced so-called broadsheets for wide distribution, conveying news and commentary through metaphor and caricature (Danjoux, 2007), accessible even to illiterate audiences. Political cartoons had the power to incite revolution. Radical ideas could transcend borders and compel the masses to challenge religious authorities – like the 16th century German Reformation breaking from the Catholic Church – and political rule – like the 18th century American colonies revolting against the English King George III. By the 19th century, broadsheets evolved to newspapers circulating throughout Europe and the US (Ibid.).

Risks and Reach

Independent voices are vital to a democracy, and editorial cartoons provide a way to dress down the powerful and challenge the status quo. Yet, politics is a risky realm, and editorial cartoonists risk reprisal in all settings.

In early 19th century France, the lithographer Honore Daumier was an ardent champion for the oppressed peasant class. Publishing his editorial cartoons in numerous publications, Daumier repeatedly lambasted King Louis-Phillippe for exploiting laborers. His cartoons portrayed the King as a bloated pear, and a grotesque giant “Gargantua,” feeding off the toil of his people. The king first fined, then imprisoned the artist, and finally banned political cartoons altogether (Cronin, 2008).

An independent artist was vulnerable financially and politically, but a publication could provide more security. By the mid-19th century in America, newspapers regularly featured editorial cartoons to engage readers and influence public opinion. Major political newspapers featured cartoons expressing publisher’s views. As artists welcomed a steady paycheck, they also sacrificed independence and deferred to the editors’ direction. Consequently, artists shared the risk of reprisal yet broadened their reach through editors and publications.

Around the Civil War, Harper’s Weekly hired political illustrator Thomas Nast, who is sometimes called the "Father of the American Cartoon." Nast pitched a campaign via cartoon to expose William M. “Boss” Tweed, and his corrupt Democratic New York City political machine known as Tammany Hall. Nast’s drawings rendered the Boss’ portly figure, tweedy suit, and signature diamond stickpin, with a sack of money in place of his head. Tweed’s giant figure towered over police who couldn’t touch him. The public was blasé, trusting the government to manage crime.

Tweed, who routinely bribed officials to indulge his crimes, recognized Nast posed a threat: “Stop Them Damn Pictures. I don’t care so much what the papers write about me. My constituents can’t read. But, damn it, they can see pictures.”

Boss Tweed’s henchmen tried to bribe Nast – offering him $100,000 to study art in Europe – but Nast continued his attach until his cartoons incited the public to vote Tweed’s cronies out of power. Tween died in prison in 1878 (Hess, p.13).

On a darker level, editorial cartoonists’ barbs can imperil the publication and human life. The Paris-based satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo has published cartoons mocking celebrities and religions of all kinds, including the Muslim Prophet Muhammad. Those cartoons prompted protests from Muslims around the world — and ultimately violent retaliation.

In 2011, the office was firebombed. Then, in early January 2015, terrorists stormed the office firing automatic assault rifles, killing 12 people, including the editor and two police officers. The assailants shouted, " Allahu Akbar !" God is most great , a Muslim declaration of faith.

French President Francois Hollande called for national unity, increased security for media organizations, and vowed, “Freedom is always bigger than barbarism. Vive La France” (Vinograd, Jamieson, Viala & Smith, 2015).

Benjamin Franklin, Join, or Die. 1754

Tools of the trade: characters and symbols

Artists not only drew actual people, but also created stock characters and relied on symbols to convey their message. Benjamin Franklin created the first American newspaper cartoon in 1754, entitled “Join, or Die,” depicting the eight colonies as a snake divided in eight pieces. The snake image reappears in every conflict through the Revolutionary War. The Virginia Colony’s Culpepper Minutemen also employed a snake as an emblem of unity, “Liberty or Death. Don’t tread on me” (Press, p. 209).

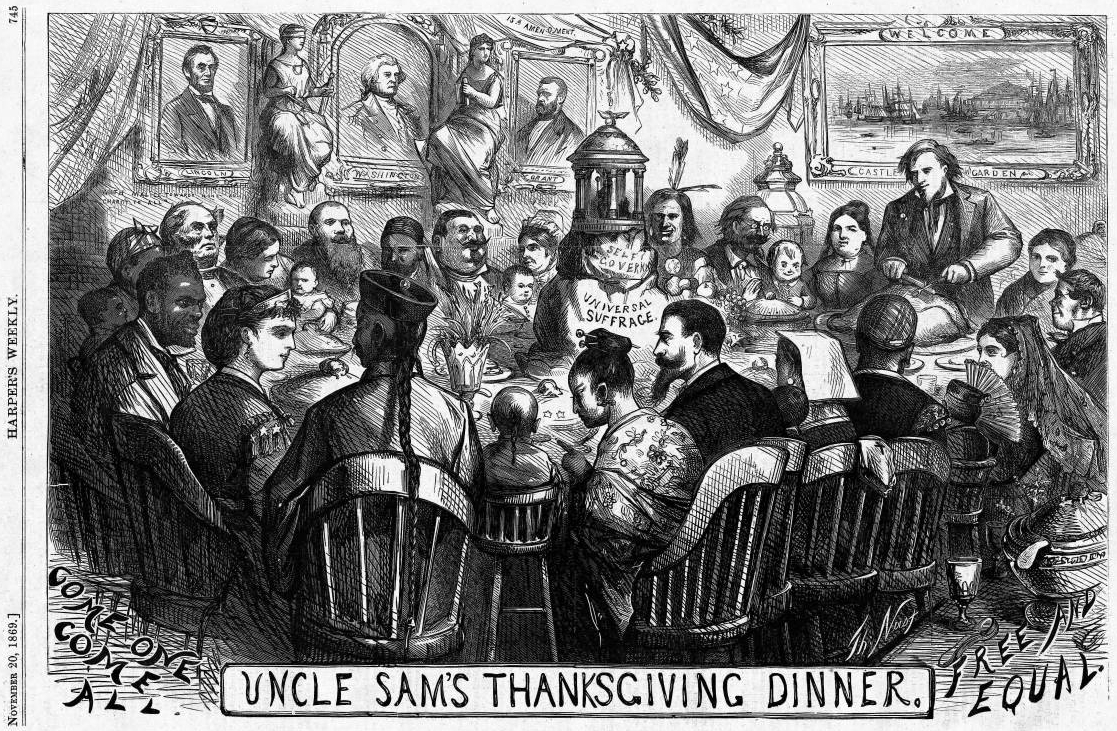

A century later in the 1870s, Thomas Nast popularized the US political symbols of Democratic donkey and Republican elephant (Stamp, 2012). America has been portrayed as a native-American Indian, an eagle (Press, p.212), leggy Uncle Sam, or stalwart Lady Liberty; England as a lion (Press, p. 210), or a jovial character named John Bull (Press, p.214); the Red Cross has been personified as a goddess-like nurturing woman; the New Year as an infant.

In early 20th century Rochester, New York, John Scott Clubb invented Joel Baggs to render a humble citizen, an elderly hayseed, while Clubb and colleague Elmer Messner both conjured a broader world view through their figure Globe Head.

20th century British artist Carl Giles ran political cartoons in the Daily Express newspaper, featuring a fictional family whose quirky Grandma comments on contemporary national and world politics.

Recognition and role today

The Pulitzer Prize, established in 1917, first awarded a prize for current efforts for Editorial Cartoons in 1922, to Rollin Kirby of New York World (Press, p.196).

The 19th and early 20th century was a golden age of newspapers, before they faced competition from new media like radio and television (Clune, p.241). Multiple papers favored different political parties. The press offered partisan, editorial commentary through word and illustration by paid staff.

As papers grew – through takeovers like Frank Gannett’s emerging empire in New York – so did their readership broaden, shifting the media’s mission to objective news reporting, with less editorializing and more entertainment. To avoid offending a widening, multi-cultural audience, publications grew more commercial, so as to sell the news rather than comment on it (Danjoux, 2007).

In the 1930s, syndication allowed editorial cartoonists to broaden their range again. A publication, an independent writer, or artist could sell work to other publications.

By the 1990s, the digital age opened a new frontier to the media, to quickly and cheaply reach a limitless audience. Editorial cartoonists stepped away from the editor's edict. Through the World Wide Web, artists reclaimed their independent voice and emerged as global freelancers.

Today, amidst a plethora of views and voices on the Web, some besieged leaders dismiss an inconvenient challenge as fake news. Yet, whatever the platform and perils, editorial cartoons have the power to deflate hubris, uncover deceit, incite revolution, dethrone a bully. Whether addressing epidemics, economics, or elections, editorial cartoons surmount language and cultural barriers to speak truth to power.

As history repeats and patterns emerge, two maxims fortify the independent voice: The pen is mightier that the sword, and, a picture is worth a thousand words.

Cronin, B. (2008, Oct 2). Stars of Political Cartooning - Honore Daumier. Retrieved from https://cbr.com

Danjoux, I. Reconsidering the Decline of the Editorial Cartoon. Political Science and Politics. (2007, Apr.). American Political Science Association, 40 (2), 245-248. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.com/stable/20451928

Hess, S. Kaplan, M. (1975). The Ungentlemanly Art: A History of American Political Cartoons . New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.

Lagasse, P. (Ed). (2000). The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). Madison, WI: Columbia University Press, 486.

Miranda, L-M. (2019, Dec.). “What Art Can Do: The Power of Stories That are Unshakably True.” The Atlantic. 112- 114.

The Oxford English Dictionary (1971). New York: Oxford University Press

Press, C. (1981). The Political Cartoon . London: Associated University Presses, Inc.

Stamp, J. (2012, October 23). “Political Animals: Republican Elephants and Democratic Donkeys.” Retrieved from http://www.smithsonianmag.com

Vinograd, C., Jamieson, A., Viala, F. & Smith, A. (2015, Jan 7). Paris Magazine Attack. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com

- Ethics & Leadership

- Fact-Checking

- Media Literacy

- The Craig Newmark Center

- Reporting & Editing

- Ethics & Trust

- Tech & Tools

- Business & Work

- Educators & Students

- Training Catalog

- Custom Teaching

- For ACES Members

- All Categories

- Broadcast & Visual Journalism

- Fact-Checking & Media Literacy

- In-newsroom

- Memphis, Tenn.

- Minneapolis, Minn.

- St. Petersburg, Fla.

- Washington, D.C.

- Poynter ACES Introductory Certificate in Editing

- Poynter ACES Intermediate Certificate in Editing

- Ethics & Trust Articles

- Get Ethics Advice

- Fact-Checking Articles

- International Fact-Checking Day

- Teen Fact-Checking Network

- International

- Media Literacy Training

- MediaWise Resources

- Ambassadors

- MediaWise in the News

Support responsible news and fact-based information today!

Here are the 2020 Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoons

If you read The New Yorker, you’ve probably already seen this year’s Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoons.

On Monday, Barry Blitt won a Pulitzer for his political illustrations, which frequently criticize President Donald Trump and his administration. Blitt’s work regularly appears on the cover of The New Yorker and the op-ed page of The New York Times.

Since 1992, Blitt has contributed more than 100 covers to The New Yorker, where he’s a contributing cartoonist and illustrator. Some of his most iconic work uses humor to criticize the Trump administration, such as illustrations that show the president belly-flopping into a pool and giving a press briefing in the nude.

But Blitt’s success as a cartoonist goes back further than Trump.

His illustrations for The New Yorker were named Cover of the Year by the American Society of Magazine Editors in 2006 and 2009. The first award was for a cover called “Deluged,” which was published in September 2005 — a month after Hurricane Katrina — and shows members of the George W. Bush administration meeting during a flood in the Oval Office. The second award was for a July 2008 cover called “The Politics of Fear,” which portrays Barack and Michelle Obama dressed as Islamic extremists to satirize the political attacks against them during the presidential election.

There were three finalists for this year’s Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning. They include Lalo Alcaraz for his Latinx perspective on local and national issues, Matt Bors of The Nib for criticism of the Trump administration and moderate Democrats, and Kevin “Kal” Kallaugher for a portfolio that addresses Trump and Baltimore politics. Bors and Kallaugher were previously named Pulitzer finalists in 2012 and 2015, respectively.

Below are a few examples of Blitt’s work for The New Yorker over the past year. For more, check out his website and book .

A cartoon by Barry Blitt. https://t.co/jiicJy3TUR pic.twitter.com/umG7cfjaJq — The New Yorker (@NewYorker) August 12, 2019

“Donald Trump Dreams of Golf in Greenland” by Barry Blitt. https://t.co/0QqfKW8UcI pic.twitter.com/0G8KVfZF17 — The New Yorker (@NewYorker) August 24, 2019

An early look at next week’s cover, “Whack Job,” by Barry Blitt. https://t.co/BeqIKP0Xwh pic.twitter.com/CyFUGQxGxO — The New Yorker (@NewYorker) September 27, 2019

In today’s cartoon by Barry Blitt, the aftermath of the Mueller report: https://t.co/qmOXDgxar2 pic.twitter.com/0EvwswVCaT — The New Yorker (@NewYorker) March 25, 2019

An early look at next week’s cover, “The Shining,” by Barry Blitt. https://t.co/KVWteOZfAX pic.twitter.com/FsevJqnTq9 — The New Yorker (@NewYorker) May 23, 2019

Barry Blitt’s guide to shadow puppetry in 2020. pic.twitter.com/EZzaRD3HFk — The New Yorker (@NewYorker) January 24, 2020

In the latest installment of Barry Blitt’s Kvetchbook, Donald Trump’s new rank. pic.twitter.com/Y46bvsjO6c — The New Yorker (@NewYorker) October 25, 2019

An early look at next week’s cover, “All That Money Can Buy,” by Barry Blitt: https://t.co/zKFwmlHNgP pic.twitter.com/pPuB0tuGHH — The New Yorker (@NewYorker) February 21, 2020

In the newest installment of Blitt’s Kvetchbook, Barry Blitt illustrates some scenes from the Trump impeachment hearings. https://t.co/bqXxfz5m5s pic.twitter.com/51Bq3kT3Rn — The New Yorker (@NewYorker) November 22, 2019

In this week’s installment of Barry Blitt’s Kvetchbook, a State of the Union surprise from Donald Trump. pic.twitter.com/5IPIVZdiSG — The New Yorker (@NewYorker) February 4, 2020

The cover for this year’s Anniversary Issue, “Origin Story,” by Barry Blitt: https://t.co/xDobncvGl7 pic.twitter.com/ssZzcm6ZcW — The New Yorker (@NewYorker) February 10, 2020

The latest installment of Barry Blitt’s Kvetchbook features a really enhanced interrogation. pic.twitter.com/AzcdAw30aM — The New Yorker (@NewYorker) May 1, 2020

Daniel Funke is a staff writer covering online misinformation for PolitiFact. Reach him at [email protected] or on Twitter @dpfunke.

More Pulitzer coverage from Poynter

- With most newsrooms closed, Pulitzer Prize celebrations were a little different this year

- Here are the winners of the 2020 Pulitzer Prizes

- Pulitzers honor Ida B. Wells, an early pioneer of investigative journalism and civil rights icon

- Nikole Hannah-Jones’ essay from ‘The 1619 Project’ wins commentary Pulitzer

- Reporting about climate change was a winner in this year’s Pulitzers

- ‘Lawless,’ an expose of villages without police protection, wins Anchorage Daily News its third Public Service Pulitzer

- The iconic ‘This American Life’ won the first-ever ‘Audio Reporting’ Pulitzer

- The Washington Post won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting for a novel climate change story

CNN mourns the loss of commentator Alice Stewart

Stewart, a veteran political adviser who worked on several Republican presidential campaigns, was 58.

The best Pulitzer leads (or ledes) in 2024

Longtime writing coach Roy Peter Clark gives this year’s award to a gripping narrative about two octogenarians who died in a hurricane

Benny Johnson’s claim that Joe Biden set up Donald Trump with classified documents is false

The conservative podcaster claimed the Biden administration framed former President Donald Trump by shipping boxes of classified documents to his home

Opinion | We’re set for the presidential debates. Now what?

The first debate is set for June 27, much earlier than usual. It will appear on CNN. Jake Tapper and Dana Bash will moderate.

The World Health Organization’s pandemic plan won’t end free speech

A draft of the WHO’s pandemic accord says that the document will be used with respect to individual’s personal freedoms

Start your day informed and inspired.

Get the Poynter newsletter that's right for you.

Advanced Composition Editorial Cartoon

We will write several of these brief papers on editorial cartoons or other graphics during the course. There is a cartoon at the bottom of this page. Look at it quickly, then read the instructions here, then go back and examine the cartoon carefully and write the paper. It should be from 500-750 words.

Editorial Cartooning: Unlike the comics on the "funny pages," political or editorial cartoons have, for well over a century, been a respected means for expressing opinions on events, personalities, and issues in the public debate. Today a Pulitzer Prize is awarded annually for Editorial Cartooning. Such cartoons are not meant primarily to entertain or to generate humor. Rather, their purpose is to make pointed commentaries on subjects of public interest in an interesting and arresting manner. Thus, they appear on the editorial pages of newspapers, magazines, and other publications rather than in pages devoted to entertainment.

Generally we think of editorials as being text, but the political cartoon makes its editorial comment with a graphical display, primarily with pictures, usually including some text either as a caption or as dialogue. The effective cartoonist provides enough information in the cartoon to give the viewer a clear idea of the subject or issue and what the view on that subject the cartoonist has. The cartoonist has a topic and a thesis. In other words, the cartoon provides the answers to the questions, "What’s the topic?" and "What’s the point?"

The Essay: For this essay, your task is to define the topic and the point of a political cartoon. You will write an essay explaining the point of the cartoon and how the cartoon expresses the opinion of the cartoonist—What does the cartoon "say"? How does it "say" it? Having done that basic task, the most effective essays may go beyond those minimum expectations and provide some commentary and context for the discussion. That is, having defined the position of the cartoonist, you may want to define your own position on the subject and support and explain that.

There are some minimum expectations for the essay itself. It should have a title. It should begin with an introduction that generates interest and identifies your topic. It should make a clear statement of your thesis (for example, "The cartoonist suggests that people don’t care as much as they claim to about violence in the media.") It should include a detailed description of the cartoon in order to support your thesis. It should mention the name of the cartoonist. If you include your own views on the subject, they should appear separate from the description and not detract from it. The ending should provide a sense of closure. The essay should have few, if any, grammatical or mechanical errors. The best essays will show evidence of planning and display a variety of sentence types and a careful attitude about word choice and phrasing.

Assume that your audience is a general reader who has not seen the cartoon . Begin by examining the cartoon carefully and making notes on what you plan to cover in the essay. Make a plan! Keep it between 500 and 750 words.

Write the essay in the word processor, save it to your hard drive, and copy the essay into an email message to me (no attachments) before midnight.

Home Page | Schedule | Nelson's Home Page | Email Nelson | Pluto | Discussion Board | Mundt Library | Tutorial

- Varsity Tutors

- K-5 Subjects

- Study Skills

- All AP Subjects

- AP Calculus

- AP Chemistry

- AP Computer Science

- AP Human Geography

- AP Macroeconomics

- AP Microeconomics

- AP Statistics

- AP US History

- AP World History

- All Business

- Business Calculus

- Microsoft Excel

- Supply Chain Management

- All Humanities

- Essay Editing

- All Languages

- Mandarin Chinese

- Portuguese Chinese

- Sign Language

- All Learning Differences

- Learning Disabilities

- Special Education

- College Math

- Common Core Math

- Elementary School Math

- High School Math

- Middle School Math

- Pre-Calculus

- Trigonometry

- All Science

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- All Engineering

- Chemical Engineering

- Civil Engineering

- Computer Science

- Electrical Engineering

- Industrial Engineering

- Materials Science & Engineering

- Mechanical Engineering

- Thermodynamics

- Biostatistics

- College Essays

- High School

- College & Adult

- 1-on-1 Private Tutoring

- Online Tutoring

- Instant Tutoring

- Pricing Info

- All AP Exams

- ACT Tutoring

- ACT Reading

- ACT Science

- ACT Writing

- SAT Tutoring

- SAT Reading

- SAT Writing

- GRE Tutoring

- NCLEX Tutoring

- Real Estate License

- And more...

- StarCourses

- Beginners Coding

- Early Childhood

- For Schools Overview

- High-Dosage Tutoring

- Free 24/7 Tutoring & Classes

- Live Learning Platform

- Learning Outcomes

- About The Tutors

- Talk with Our Team

- Reviews & Testimonials

- Press & Media Coverage

- Tutor/Instructor Jobs

- Corporate Solutions

- About Nerdy

- Become a Tutor

- Book Reports

- Children’s Literature

- Interdisciplinary

- Just for Fun

- Literature (Prose)

- Professional Resources

- Reading/Literacy

- Shakespeare

- Study Guides

- Technology Integration

- Young Adult Literature

Editorial Writing & Cartooning

Analyzing Political Cartoons This 1-page teacher guide offers questions for students who are analyzing political cartoons. From the U. S. Library of Congress, requires Adobe Reader for access.

Captions: Pictures Are Worth A Thousand Words Students analyze a variety of political cartoons and examine their impact as a persuasive medium. This unit plan includes assessment.

Creating Cartoons: Art and Controversy Introduction and samples of political cartoons from the U. S. Library of Congress.

A "defining moment" in editorial writing Students will be introduced to the definition mode of writing. Students will learn to define a particular subject by responding in an editorial format. Students will first compose an editorial graphic organizer, which will aid in composing a completed editorial using the writing process. This lesson includes modifications for a Novice Low Limited English student.

Double Take Toons This cartoon series from NPR offers a conservative and a liberal editorial cartoon on the same current event. Students can compare and contrast use of detail, point of view, and more.

Enduring Outrage: Editorial Cartoons by Herblock Herbert Block published his first cartoon in 1929, starting a career that continued until 2001. This online exhibit features both rough sketches and finished cartoons with a variety of themes.

Herblock and Editorial Cartooning Lesson plans and student handouts related to democracy, education in America, presidents, the environment, and civil rights.

It's No Laughing Matter: Analyzing Political Cartoons Political cartoonist Bill Mauldin's career spanned more than 50 years. Here, students use his cartoons about World War II and the Civil Rights Movement to develop skills of analysis.

Daryl Cagle's Professional Cartoonists' Index A lively site with links for editorial cartoons from around the world.

TIME Cartoons of the Week Cartoons for the week, links to Quotes of the Week, Pictures of the Week, and Photo Essays.

- Accessibility Statement

- Introduction, Awards, and Recognitions

- Table of Contents with Critical Media Literacy Connections

- Updates & Latest Additions

- Learning Pathway: Racial Justice and Black Lives Matter

- Learning Pathway: Influential Women and Women's History/Herstory

- Learning Pathway: Student Rights in School and Society

- Learning Pathway: Elections 2024, 2022, & 2020

- Learning Pathway: Current Events

- Learning Pathway: Critical Media Literacy

- Teacher-Designed Learning Plans

- Topic 1. The Philosophical Foundations of the United States Political System

- 1.1. The Government of Ancient Athens

- 1.2. The Government of the Roman Republic

- 1.3. Enlightenment Thinkers and Democratic Government

- 1.4. British Influences on American Government

- 1.5. Native American Influences on U.S. Government

- Topic 2. The Development of the United States Government

- 2.1. The Revolutionary Era and the Declaration of Independence

- 2.2. The Articles of Confederation

- 2.3. The Constitutional Convention

- 2.4. Debates between Federalists and Anti-Federalists

- 2.5. Articles of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights

- Topic 3. Institutions of United States Government

- 3.1. Branches of the Government and the Separation of Powers

- 3.2. Checks and Balances Between the Branches of Government

- 3.3. The Roles of the Congress, the President, and the Courts

- 3.4. Elections and Nominations

- 3.5. The Role of Political Parties

- Topic 4. The Rights and Responsibilities of Citizens

- 4.1. Becoming a Citizen

- 4.2. Rights and Responsibilities of Citizens and Non-Citizens

- 4.3. Civic, Political, and Private Life

- 4.4. Fundamental Principles and Values of American Political and Civic Life

- 4.5. Voting and Citizen Participation in the Political Process

- 4.6. Election Information

- 4.7. Leadership and the Qualities of Political Leaders

- 4.8. Cooperation Between Individuals and Elected Leaders

- 4.9. Public Service as a Career

- 4.10. Liberty in Conflict with Equality or Authority

- 4.11. Political Courage and Those Who Affirmed or Denied Democratic Ideals

- 4.12. The Role of Political Protest

- 4.13. Public and Private Interest Groups, PACs, and Labor Unions

- Topic 5. The Constitution, Amendments, and Supreme Court Decisions

- 5.1. The Necessary and Proper Clause

- 5.2. Amendments to the Constitution

- 5.3. Constitutional Issues Related to the Civil War, Federal Power, and Individual Civil Rights

- 5.4. Civil Rights and Equal Protection for Race, Gender, and Disability

- 5.5. Marbury v. Madison and the Principle of Judicial Review

- 5.6. Significant Supreme Court Decisions

- Topic 6. The Structure of Massachusetts State and Local Government

- 6.1. Functions of State and National Government

- 6.2. United States and Massachusetts Constitutions

- 6.3. Enumerated and Implied Powers

- 6.4. Core Documents: The Protection of Individual Rights

- 6.5. 10th Amendment to the Constitution

- 6.6. Additional Provisions of the Massachusetts Constitution

- 6.7. Responsibilities of Federal, State and Local Government

- 6.8. Leadership Structure of the Massachusetts Government

- 6.9. Tax-Supported Facilities and Services

- 6.10. Components of Local Government

- Topic 7. Freedom of the Press and News/Media Literacy

- 7.1. Freedom of the Press

- 7.2. Competing Information in a Free Press

- 7.3. Writing the News: Different Formats and Their Functions

- 7.4. Digital News and Social Media

- 7.5. Evaluating Print and Online Media

- 7.6. Analyzing Editorials, Editorial Cartoons, or Op-Ed Commentaries

- Index of Terms

- Translations

Analyzing Editorials, Editorial Cartoons, or Op-Ed Commentaries

Choose a sign-in option.

Tools and Settings

Questions and Tasks

Citation and Embed Code

Standard 7.6: Analyzing Editorials, Editorial Cartoons, or Op-Ed Commentaries

Analyze the point of view and evaluate the claims of an editorial, editorial cartoon, or op-ed commentary on a public issue at the local, state or national level. (Massachusetts Curriculum Framework for History and Social Studies) [8.T7.6]

FOCUS QUESTION: How Do Writers Express Opinions through Editorials, Editorial Cartoons, and Op-Ed Commentaries in Print and Online?

Modules for this standard include:.

- MEDIA LITERACY CONNECTIONS: Memes and TikToks as Political Cartoons

- UNCOVER: Deepfakes, Fake Profiles, and Political Messaging

- ENGAGE: Should Facebook and Other Technology Companies Be Required to Regulate Political Content on their Social Media Platforms?

1. INVESTIGATE: Evaluating Editorials, Editorial Cartoons, and Op-Ed Commentaries

Being able to critically evaluate editorials, editorial cartoons, and Op-Ed commentaries requires an understanding that all three are forms of persuasive writing . Writers use these genres (forms of writing) to influence how readers think and act about a topic or an issue . Editorials and Op-Ed commentaries rely mainly on words, while editorial cartoons combine limited text with memorable visual images. But the intent is the same for all three - to motivate, persuade, and convince readers.

Many times, writers use editorials, editorial cartoons, and Op-Ed commentaries to argue for progressive social and political change. Fighting for the Vote with Cartoons shows how cartoonists used the genre to build support for women's suffrage (The New York Times , August 19, 2020).

Another example is Thomas Nast's 1869 " Uncle Sam's Thanksgiving Dinner " cartoon that argues that everyone should have the right to vote - published at a time when African Americans, Native Americans, and women could not. Nast constructs a powerful appeal using few words and an emotionally-charged image.

But these same forms of writing can be used by individuals and groups who seek to spread disinformation and untruths .

Large numbers of teens and tweens tend to trust what they find on the web as accurate and unbiased (NPR, 2016). They are unskilled in separating sponsored content or political commentary from actual news when viewing a webpage or a print publication. In online settings, they can be easily drawn off-topic by clickbait links and deliberately misrepresented information.

The writing of Op-Ed commentaries achieved national prominence at the beginning of June 2020 when the New York Times published an opinion piece written by Arkansas Senator Tom Cotton in which he urged the President to send in armed regular duty American military troops to break up street protests across the nation that followed the death of George Floyd while in the custody of Minneapolis police officers.

Many staffers at the Times publicly dissented about publishing Cotton's piece entitled "Send in the Troops," citing that the views expressed by the Senator put journalists, especially journalists of color, in danger. James Bennett, the Times Editorial Page editor defended the decision to publish , stating if editors only published views that editors agreed with, it would "undermine the integrity and independence of the New York Times." The editor reaffirmed that the fundamental purpose of newspapers and their editorial pages is "not to tell you what to think, but help you to think for yourself."

The situation raised unresolved questions about the place of Op-Ed commentaries in newspapers and other media outlets in a digital age when the material can be accessed online around the country and the world. Should any viewpoint, no matter how extreme or inflammatory, be given a forum for publication such as that provided by the Op-Ed section of a major newspaper's editorial page?

Many journalists as well as James Bennett urge newspapers to not only publish wide viewpoints, but provide context and clarification about the issues being discussed. Readers and viewers need to have links to multiple resources so they can more fully understand what is being said while assessing for themselves the accuracy and appropriateness of the remarks.

Media Literacy Connections: Memes and TikToks as Political Cartoons

Political cartoons and comics as well as memes and Tik Toks are pictures with a purpose. Writers and artists use these genres to entertain, persuade, inform, and express fiction and nonfiction ideas creatively and imaginatively.

Like political cartoons and comics, memes and Tik Toks have the potential to provide engaging and memorable messages that can influence the political thinking and actions of voters regarding local, state, and national issues.

In this activity, you will evaluate the design and impact of political memes, Tik Toks , editorial cartoons, and political comics and then create your own to influence others about a public issue.

- Activity: Analyze Political Cartoons, Memes, and TikToks

Suggested Learning Activities

- Review the articles Op-Ed? Editorial? & Op Ed Elements . What do all these terms really mean?

- Have students write two editorial commentaries about a public issue - one with accurate and truthful information; the other using deliberate misinformation and exaggeration.

- Students review their peers' work to examine how information is being conveyed, evaluate the language and imagery used, and investigate how much truth and accuracy is being maintained by the author(s).

- As a class, discuss and vote on which commentaries are "fake news."

- Have students draw editorial cartoons about a school, community or national issue.

- Post the cartoons on the walls around the classroom and host a gallery walk.

- Ask the class to evaluate the accuracy and truthfulness of each cartoon.

- Choose a political cartoon from a newspaper or online source.

- Use the Cartoon Analysis Guide from the Library of Congress or a Cartoon Analysis Checklist from TeachingHistory.org to examine its point of view.

Online Resources for Evaluating Information and Analyzing Online Claims

- Do the Facts Hold Up? NewseumEd

- The Fake News Fallacy , The New Yorker (September 4, 2017)

- Lesson Plan from Common Sense Education for evaluating fake websites which look credible

- Check, Please! Starter Course - a free online course to develop information literacy skills

- Interpreting Political Cartoons in the History Classroom , TeachingHistory.org

2. UNCOVER: Deepfakes, Fake Profiles, and Political Messaging

Deepfakes, fake profiles, and fake images are a new dimension of political messaging on social media. In December 2019, Facebook announced it was removing 900 accounts from its network because the accounts were using fake profile photos of people who did not exist. Pictures of people were generated by an AI (artificial intelligence) software program (Graphika & the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensics Lab, 2019). All of the accounts were associated with a politically conservative, pro-Donald Trump news publisher, The Epoch Times .

The People in These Photos Do Not Exist; Their Pictures Were Generated by an Artificial Intelligence Program Images on Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

Deepfakes are digitally manipulated videos and pictures that produce images and sounds that appear to be real (Shao, 2019). They can be used to spread misinformation and influence voters. In December 2020, there were more than 85,000 deepfake videos online, and the number was doubling every six months.(Thompson, 2021, p. 16).

Researchers and cybersecurity experts warn that it is possible to manipulate digital content - facial expressions, voice, lip movements - so that was it being seen is "indistinguishable from reality to human eyes and ears" (Patrini, et. al., 2018). For example, you can watch a video of George W. Bush, Donald Trump, and Barack Obama saying things that they never would (and never did) say, but that looks authentic (Link here to Watch a man manipulate George Bush's face in real time ).

Journalist Michael Tomasky, writing about the 2020 election outcomes in the New York Review of Books , cited a New York Times report that fake videos of Joe Biden "admitting to voter fraud" had been viewed 17 million times before Americans voted on election day ( What Did the Democrats Win? , December 17, 2020, p. 36).

To recognize deepfakes, technology experts advise viewers to look for face discolorations, poor lightning, badly synced sound and video, and blurriness between face, hair and neck ( Deepfake Video Explained: What They Are and How to Recognize Them , Salon, September 15, 2019). To combat deepfakes, Dutch researchers have proposed that organizations make digital forgery more difficult with techniques that are now used to identify real currency from fake money and to invest in building fake detection technologies (Patrini, et.al., 2018).

The presence of fake images are an enormous problem for today's social media companies. On the one hand, they are committed to allowing people to freely share materials. On the other hand, they face a seemingly endless flow of Photoshopped materials that have potentially harmful impacts on people and policies. In 2019 alone, reported The Washington Post , Facebook eliminated some three billion fake accounts during one six month time period.

You can learn about Facebook's current efforts at regulating fake content by linking to its regularly updated Community Standards Enforcement Report . You can also explore the topic more deeply in the book Deepfakes: The Coming Infocalypse by Nina Schick (2020).

Photo Tampering in History

Photo tampering for political or commercial purposes happened long before modern-day digital tools made possible deepfakes and other cleverly manipulated images.

- The Library of Congress has documented how a famous photo of Abraham Lincoln is a composite of Lincoln's head superimposed on the body of the southern politician and former vice-president John C. Calhoun.

- In the early decades of the 20th century, the photographer Edward S. Curtis, who took more than 40,000 pictures of Native Americans over 30 years, staged and retouched his photos to try and show native life and culture before the arrival of Europeans. The Library of Congress has the famous photos in which Curtis removed a clock from between two Native men who were sitting in a hunting lodge dressed in traditional clothing that they hardly ever wore at the time (Jones, 2015).

- The Depression-era photographer Dorothea Lange staged her iconic "Migrant Mother" photograph, although the staging captured the depths of poverty and sacrifice faced by so many displaced Americans during the 1930s. You can analyze in photo in more detail in this site from the The Kennedy Center .

- It is now known that the famous 1934 Loch Ness Monster photograph was a staged photo of a toy drifting in the water.

You can find more examples of fake photos in the collection Photo Tampering Through History and at the Hoax Museum's Hoax Photo Archive.

- Show the video Can You Spot a Phony Video? from Above the Noise , KQED San Francisco.

- Then, ask students to create an editorial cartoon about deepfakes.

- Write an Op-Ed commentary about fake profiles and fake images on social media and how that impacts people's political views.

- Take a public domain historical photo and edit it using SumoPaint (free online) or Photoshop to change the context or meaning of the image.

- Showcase the fake and real photos side by side and ask students to vote on which one is real and justify their reasoning.

3. ENGAGE: Should Facebook and Other Technology Companies Be Required to Regulate Political Content on their Social Media Platforms?

Social media and technology companies generate huge amounts of revenue from advertisements on their sites. 98.5% of Facebook’s $55.8 billion in revenue in 2018 was from digital ads ( Investopedia, 2020 ). Like Facebook, YouTube earns most of its revenue from ads through sponsored videos, ads embedded in videos, and sponsored content on YouTube’s landing page ( How Does YouTube Make Money? ). With all this money to be made, selling space for politically-themed ads has become a major part of social media companies’ business models.

Political Ads

Political ads are a huge part of the larger problem of fake news on social media platforms like Facebook. Researchers found that "politically relevant disinformation" reached over 158 million views in the first 10 months of 2019, enough to reach every registered voter in the country at least once ( Ingram, 2019, para. 2 ). Nearly all fake news (91%) is negative and a majority (62%) is about Democrats and liberals (Legum, 2019, para. 5 ).

But political ads are complicated matters, especially when the advertisements themselves may not be factually accurate or are posted by extremist political groups promoting hateful and anti-democratic agendas. In late 2019, Twitter announced it will stop accepting political ads in advance of the 2020 Presidential election (CNN Business, 2019). Pinterest, TikTok, and Twitch also have policies blocking political ads —although 2020 Presidential candidates including Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders have channels on Twitch. Early in 2020, YouTube announced that it intends to remove from its site misleading content that can cause "serious risk of egregious harm." More than 500 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute.

Facebook has made changes to its policy about who can run political ads on the site, but stopped short of banning or fact-checking political content. An individual or organization must now be “authorized” to post material on the site. Ads now include text telling readers who paid for it and that the material is “sponsored” (meaning paid for). The company has maintained a broad definition of what counts as political content, stating that political refers to topics of “public importance” such as social issues, elections, or politics.

Read official statements by Facebook about online content, politics, and political ads:

- Facebook Community Standards

- Facebook Policy on Ads Related to Politics or Issues of National Importance

- Political Content Authorization Guide

- Facebook and Government

- How Is Facebook Addressing False News Through Third-Party Fact-Checkers

Misinformation about Politics and Public Health

In addition to political ads, there is a huge question of what to do about the deliberate posting of misinformation and outright lies on social media by political leaders and unscrupulous individuals. The CEOs of technology firms have been reluctant to fact check statements by politicians, fearing their companies would be accused of censoring the free flow of information in democratic societies.

On January 8, 2021, two days after a violent rampage by a pro-Trump mob at the nation's Capitol, Twitter took the extraordinary step of permanently suspending the personal account of Donald Trump, citing the risk of further incitement of violence. You can read the text of the ban here: Permanent Suspension of @realDonaldTrump .Google and Apple soon followed by removing the right-wing site Parler from their app stores (Parler is seen as an alternative platform for extremist viewpoints and harmful misinformation).

Social media platforms had already begun removing or labeling tweets by the President as containing false and misleading information. At the beginning of August 2020, Facebook and Twitter took down a video of the President claiming children were "almost immune" to coronavirus as a violation of their dangerous COVID-19 misinformation policies ( NPR, August 5, 2020 ). Earlier in 2020, Twitter for the first time added a fact check to one of the President's posts about mail-in voting.

Misinformation and lies have been an ongoing feature of Trump's online statements as President and former President. The Washington Post Fact Checker reported that as of November, 5, 2020, Trump had made 29,508 false or misleading statements in 1,386 days in office as President. Then in Fall 2021, after analyzing 38 million English language articles about the pandemic, researchers at Cornell University declared that Trump was the largest driver of COVID misinformation ( Coronavirus Misinformation: Quantifying Sources and Themes in COVID -19 infodemic ).

During this same time period, Facebook was also dealing with a major report from the international technology watchdog organization, Avaaz, that held the spread health-related misinformation on Facebook was a major threat to users health and well-being ( Facebook's Algorithm: A Major Threat to Public Health , August 19, 2020). Avaaz researchers found that only 16% of health misinformation on Facebook carried a warning label, estimating that misinformation had received an estimated 3.8 billion views in the past year. Facebook responded by claiming it placed warning labels on 98 million pieces of COVID-19 misinformation.

The extensive reach of social media raises the question of just how much influence should Facebook, Twitter, and other powerful technology companies have on political information, elections and/or public policy?

Policymakers and citizens alike must decide whether Facebook and other social media companies are organizations like the telephone company which does not monitor what is being said or are they a media company, like a newspaper or magazine, that has a responsibility to monitor and control the truthfulness of what it posts online.

- Students design a political ad to post on different social media sites: Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, and TikTok.

- As a class vote on the most influential ads.

- Discuss as a group what made the ad so influential?

- What responsibility do technology companies have to evaluate the political content that appears on their social media platforms?

- What responsibility do major companies and firms have when ads for their products run on the YouTube channels or Twitter feeds of extremist political groups? Should they pull those ads from those sites?

- Should technology companies post fact-checks of ads running on their platforms?

Online Resources for Political Content on Social Media Sites

- Facebook Scrutinized Over Its 2016's Presidential Election Role , NPR (September 26, 2017)

- Facebook Haunted by Its Handling of 2016 Election Meddling , Hartmann, 2018

- Facebook Has You Labelled as Liberal or Conservative. Here's How to See It

- Facebook Political Ad Collector: How Political Advertisers Target You

- To shine a light on targeted political advertising on Facebook, ProPublica built a browser plugin that allows Facebook users to automatically send them the ads that are displayed in their News Feeds, along with their targeting information.

Standard 7.6 Conclusion

To support media literacy learning, INVESTIGATE asked students to analyze the point of view and evaluate the claims of an opinion piece about a public issue—many of which are published on social media platforms. UNCOVER explored the emergence of deepfakes and fake profiles as features of political messaging. ENGAGE examined issues related to regulating the political content posted on Facebook and other social media sites. These modules highlight the complexity that under the principle of free speech on which our democratic system is based, people are free to express their views. At the same time, hateful language, deliberately false information, and extremist political views and policies cannot be accepted as true and factual by a civil society and its online media.

This content is provided to you freely by EdTech Books.

Access it online or download it at https://edtechbooks.org/democracy/analyzing_editorials .

Analyzing the Purpose and Meaning of Political Cartoons

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

The decisions students make about social and political issues are often influenced by what they hear, see, and read in the news. For this reason, it is important for them to learn about the techniques used to convey political messages and attitudes. In this lesson, high school students learn to evaluate political cartoons for their meaning, message, and persuasiveness. Students first develop critical questions about political cartoons. They then access an online activity to learn about the artistic techniques cartoonists frequently use. As a final project, students work in small groups to analyze a political cartoon and determine whether they agree or disagree with the author's message.

Featured Resources

It’s No Laughing Matter: Analyzing Political Cartoons : This interactive activity has students explore the different persuasive techniques political cartoonists use and includes guidelines for analysis.

From Theory to Practice

- Question-finding strategies are techniques provided by the teacher, to the students, in order to further develop questions often hidden in texts. The strategies are known to assist learners with unusual or perplexing subject materials that conflict with prior knowledge.

- Use of this inquiry strategy is designed to enhance curiosity and promote students to search for answers to gain new knowledge or a deeper understanding of controversial material. There are two pathways of questioning available to students. Convergent questioning refers to questions that lead to an ultimate solution. Divergent questioning refers to alternative questions that lead to hypotheses instead of answers.

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 1. Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- 6. Students apply knowledge of language structure, language conventions (e.g., spelling and punctuation), media techniques, figurative language, and genre to create, critique, and discuss print and nonprint texts.

- 8. Students use a variety of technological and information resources (e.g., libraries, databases, computer networks, video) to gather and synthesize information and to create and communicate knowledge.

- 11. Students participate as knowledgeable, reflective, creative, and critical members of a variety of literacy communities.

Materials and Technology

- Computers with Internet access and printing capability

- Several clips of recent political cartoons from a local newspaper

- Overhead projector or computer with projection capability

- Editorial Cartoon Analysis

- Presentation Evaluation Rubric

Preparation

Student objectives.

Students will

- Develop critical question to explore the artistic techniques used in political cartoons and how these techniques impact a cartoon's message

- Evaluate an author or artist's meaning by identifying his or her point of view

- Identify and explain the artistic techniques used in political cartoons

- Analyze political cartoons by using the artistic techniques and evidence from the cartoon to support their interpretations

Session 2 (may need 2 sessions, depending on computer access)

Sessions 3 and 4.

- Daryl Cagle's Professional Cartoonist Index and The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists: Cartoons for the Classroom both provide additional lesson plans and activities for using political cartoons as a teaching tool. Students can also access these online political cartoons for additional practice in evaluating their meaning, message, and persuasiveness.

- Students can create their own political cartoons, making sure to incorporate a few of the artistic techniques learned in this lesson. Give students an opportunity to share their cartoons with the class, and invite classmates to analyze the cartoonist's message and voice their own opinions about the issue.

- This lesson can be a launching activity for several units: a newspaper unit, a unit on writing persuasive essays, or a unit on evaluating various types of propaganda. The ReadWriteThink lesson "Propaganda Techniques in Literature and Online Political Ads" may be of interest.

Student Assessment / Reflections

Assessment for this lesson is based on the following components:

- The students' involvement in generating critical questions about political cartoons in Lesson 1, and then using what they have learned from an online activity to answer these questions in Lesson 2.

- Class and group discussions in which students practice identifying the techniques used in political cartoons and how these techniques can help them to identify an author's message.

- The students' responses to the self-reflection questions in Lesson 4, whereby they demonstrate an understanding of the purpose of political cartoons and the artistic techniques used to persuade a viewer.

- The final class presentation in which students demonstrate an ability to identify the artistic techniques used in political cartoons, to interpret an author's message, and to support their interpretation with specific details from the cartoon. The Presentation Evaluation Rubric provides a general framework for this assessment.

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

Jump to navigation

- Inside Writing

- Teacher's Guides

- Student Models

- Writing Topics

- Minilessons

- Shopping Cart

- Inside Grammar

- Grammar Adventures

- CCSS Correlations

- Infographics

Get a free Grammar Adventure! Choose a single Adventure and add coupon code ADVENTURE during checkout. (All-Adventure licenses aren’t included.)

Sign up or login to use the bookmarking feature.

- 29 Writing Editorials and Cartoons

Start-Up Activity

Bring to class an interesting editorial from your local newspaper. Read it aloud, or distribute copies for students to read silently. Afterward, ask students whether or not they agree with the writer and why. Ask what the writer's strongest reason is, and what parts might not be as convincing.

Then let your students know they are about to become editorial writers themselves. And some of them may become editorial cartoonists. (See the quotation below.)

Think About It

“An illustration is a visual editorial—it's just as nuanced. Everything that goes into it is a call you make: every color, every line weight, every angle.”

—Charles M. Blow

State Standards Covered in This Chapter

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.6.1

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.6.2

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.6.3

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.6.6

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.6.8

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.7.1

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.7.2

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.7.3

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.7.6

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.7.8

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.8.1

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.8.2

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.8.3

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.8.6

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.8.8