- Get in touch

- Enterprise & IT

- Banking & Financial Services

- News media & Entertainment

- Healthcare & Lifesciences

- Networks and Smart Devices

- Education & EdTech

- Service Design

- UI UX Design

- Data Visualization & Design

- User & Design Research

- In the News

- Our Network

- Voice Experiences

- Golden grid

Critical Thinking

- Enterprise UX

- 20 Product performance metrics

- Types of Dashboards

- Interconnectivity and iOT

- Healthcare and Lifesciences

- Airtel XStream

- Case studies

Data Design

- UCD vs. Design Thinking

User & Design Research

Critical thinking is a method of analyzing ideas, concepts or data collected to evaluate the situation from different perspectives and arrive at an unbiased optimum solution. A critical thinker can anticipate the consequences of certain actions in advance. A researcher with the competency to critically think can reflect, think independently, stay objective, problem solve to deduce a solution. Therefore, critical thinking requires self-actuated discipline and correction to get one step closer to the solution iteratively.

Quick details: Critical Thinking

Structure: Unstructured

Preparation: Information needed to analyze

Deliverables: Inferences, Insights

More about Critical Thinking

Most research methods require experienced or trained researchers to define the design specifications for a project. The researcher employs different methods to collect data, analyze it and arrive at the solution that addresses user needs and expectations. One of the most important competencies that a researcher must have in order to arrive at an optimum solution is the ability to critically think and analyze.

Critical Thinking can also help identify gaps in reasoning and assumptions. Although, design researchers are expected to have this competency independently, critical thinking promotes group ideation and task execution as well. Though, it shouldn’t be seen as an opportunity to criticize someone else’s ideas or work. In that sense, the objective of critical thinking is to strengthen a theory, process, product or service and not to find unnecessary faults to ensure that the ideas or processes collapse. A mature critical thinker can define project goals, define timelines, set expectations, manage expectations, handle conflicts and work collaboratively with a team to accomplish the project goals. It is more and more evident that critical thinking, even though not given its due importance in organizations, is a critical competency that cannot be undermined.

Critical Thinking vs. Design Thinking

It is also important to discuss the difference between Design Thinking and Critical Thinking. Design Thinking is a process that involves stages of observation/interaction, empathy, problem formulation, solution deduction, testing, alteration and reiteration. Here, Critical Thinking is a part of every stage of the Design Thinking process. Essentially, effective Design Thinking cannot take place in the absence of critical or creative thinking. There is also a common misconception that critical and creative thinking are distinct from each other.

However, critical thinking requires some form as well as level of creativity. Critical and creative thinking go hand-in-hand and cannot be separated or distinguished using any formal criteria.

Advantages of Critical Thinking

1. design thinking.

Critical thinking is an important component that comes into play at every stage of the design thinking process .

2. Creative Problem Solving

Critical Thinking is not just rational and based on a set of logical rules. There is plenty of room for solid creativity to play a significant role in the critical thinking process .

3. Reflection

Critical thinking promotes independent and reflective thinking in the researcher to question and evaluate the solutions they have devised and reiterate for an optimum solution .

4. Objectivity

Effective use of this method ensures objectivity and therefore doesn’t leave much scope for biases .

5. Applications

Critical thinking is a competency and method that is applicable in all projects irrespective of the type of solution expected .

Disadvantages of Critical Thinking

1. researcher can introduce unnecessary complexity.

Too much thinking can also be detrimental to a project. Some researchers can complicate an otherwise simple project by overthinking critical and pose questions when not required .

2. Expensive researcher

A mature Critical thinking researcher can be very expensive for a low budget project. However, Critical thinking is not a competency that is extremely difficult to master .

Think Design's recommendation

It is difficult to separate reasoning from thinking and hence, this is the best context to introduce the three reasoning types: Deductive, Inductive and Abductive.

Deductive reasoning

Deductive reasoning starts with the assertion of a general rule and ends up in a guaranteed specific conclusion.

Inductive reasoning

Inductive reasoning begins with observations that are specific and ends up with a conclusion that is likely but not certain.

Abductive reasoning

Abductive reasoning starts with an incomplete set of observations and ends up with a most likely explanation.

It is believed that Design, in general is an activity that can complement abductive reasoning; that it is not very essential in the process of Design to come up with deductive or inductive reasoning. However, we wouldn’t want to generalize this at this moment but would suggest that proceeding with abductive reasoning saves a lot of time and effort if that is the objective.

Critical Thinking, when coupled with the types of reasoning above, can generate magical results. It is therefore advised to employ Critical thinking in situations where we may need abductive reasoning skills… There are chances we over-complicate things if we indulge in Critical thinking when we have clear conclusions or clear observations (Deductive and Inductive).

Was this Page helpful?

Related methods.

- Audio/ Video Analysis

- Document Research

- Heatmap Analysis

- Social Network Mapping

- Time Lapse Video

- Trend Analysis

- Usage Analytics

UI UX DESIGN

Service design.

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue we'll assume that you accept this. Learn more

Recent Tweets

Sign up for our newsletter.

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay updated with the latest insights in UX, CX, Data and Research.

Get in Touch

Thank you for subscribing.

You will be receive all future issues of our newsletter.

Thank you for Downloading.

One moment….

While the report downloads, could you tell us…

Smart. Open. Grounded. Inventive. Read our Ideas Made to Matter.

Which program is right for you?

Through intellectual rigor and experiential learning, this full-time, two-year MBA program develops leaders who make a difference in the world.

A rigorous, hands-on program that prepares adaptive problem solvers for premier finance careers.

A 12-month program focused on applying the tools of modern data science, optimization and machine learning to solve real-world business problems.

Earn your MBA and SM in engineering with this transformative two-year program.

Combine an international MBA with a deep dive into management science. A special opportunity for partner and affiliate schools only.

A doctoral program that produces outstanding scholars who are leading in their fields of research.

Bring a business perspective to your technical and quantitative expertise with a bachelor’s degree in management, business analytics, or finance.

A joint program for mid-career professionals that integrates engineering and systems thinking. Earn your master’s degree in engineering and management.

An interdisciplinary program that combines engineering, management, and design, leading to a master’s degree in engineering and management.

Executive Programs

A full-time MBA program for mid-career leaders eager to dedicate one year of discovery for a lifetime of impact.

This 20-month MBA program equips experienced executives to enhance their impact on their organizations and the world.

Non-degree programs for senior executives and high-potential managers.

A non-degree, customizable program for mid-career professionals.

2 from MIT Sloan named as Best 40-Under-40 MBA Professors

Sharper teeth, stronger bite needed for US minimum wage laws

Boston Fed CEO sees interest rates staying put for now

Credit: Mimi Phan

Ideas Made to Matter

Design thinking, explained

Rebecca Linke

Sep 14, 2017

What is design thinking?

Design thinking is an innovative problem-solving process rooted in a set of skills.The approach has been around for decades, but it only started gaining traction outside of the design community after the 2008 Harvard Business Review article [subscription required] titled “Design Thinking” by Tim Brown, CEO and president of design company IDEO.

Since then, the design thinking process has been applied to developing new products and services, and to a whole range of problems, from creating a business model for selling solar panels in Africa to the operation of Airbnb .

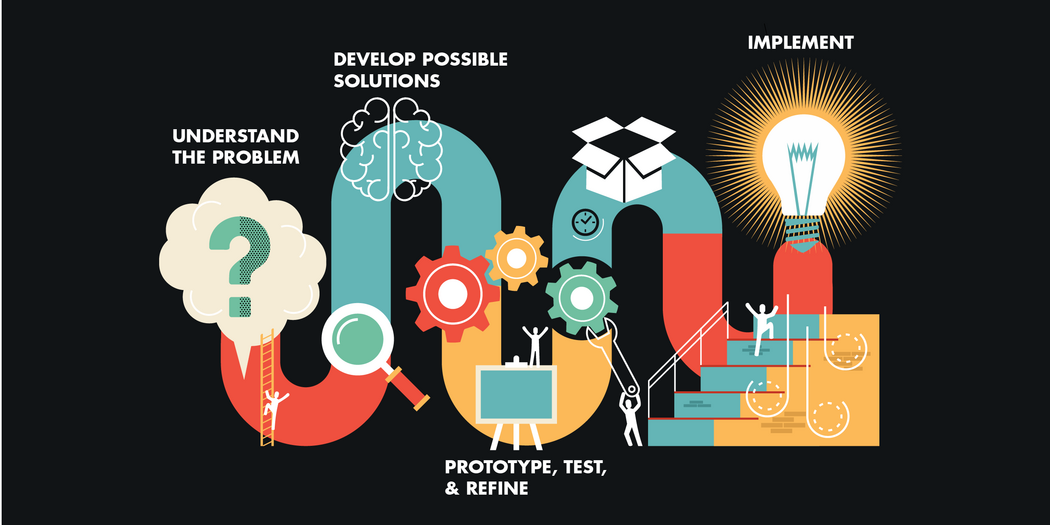

At a high level, the steps involved in the design thinking process are simple: first, fully understand the problem; second, explore a wide range of possible solutions; third, iterate extensively through prototyping and testing; and finally, implement through the customary deployment mechanisms.

The skills associated with these steps help people apply creativity to effectively solve real-world problems better than they otherwise would. They can be readily learned, but take effort. For instance, when trying to understand a problem, setting aside your own preconceptions is vital, but it’s hard.

Creative brainstorming is necessary for developing possible solutions, but many people don’t do it particularly well. And throughout the process it is critical to engage in modeling, analysis, prototyping, and testing, and to really learn from these many iterations.

Once you master the skills central to the design thinking approach, they can be applied to solve problems in daily life and any industry.

Here’s what you need to know to get started.

Understand the problem

The first step in design thinking is to understand the problem you are trying to solve before searching for solutions. Sometimes, the problem you need to address is not the one you originally set out to tackle.

“Most people don’t make much of an effort to explore the problem space before exploring the solution space,” said MIT Sloan professor Steve Eppinger. The mistake they make is to try and empathize, connecting the stated problem only to their own experiences. This falsely leads to the belief that you completely understand the situation. But the actual problem is always broader, more nuanced, or different than people originally assume.

Take the example of a meal delivery service in Holstebro, Denmark. When a team first began looking at the problem of poor nutrition and malnourishment among the elderly in the city, many of whom received meals from the service, it thought that simply updating the menu options would be a sufficient solution. But after closer observation, the team realized the scope of the problem was much larger , and that they would need to redesign the entire experience, not only for those receiving the meals, but for those preparing the meals as well. While the company changed almost everything about itself, including rebranding as The Good Kitchen, the most important change the company made when rethinking its business model was shifting how employees viewed themselves and their work. That, in turn, helped them create better meals (which were also drastically changed), yielding happier, better nourished customers.

Involve users

Imagine you are designing a new walker for rehabilitation patients and the elderly, but you have never used one. Could you fully understand what customers need? Certainly not, if you haven’t extensively observed and spoken with real customers. There is a reason that design thinking is often referred to as human-centered design.

“You have to immerse yourself in the problem,” Eppinger said.

How do you start to understand how to build a better walker? When a team from MIT’s Integrated Design and Management program together with the design firm Altitude took on that task, they met with walker users to interview them, observe them, and understand their experiences.

“We center the design process on human beings by understanding their needs at the beginning, and then include them throughout the development and testing process,” Eppinger said.

Central to the design thinking process is prototyping and testing (more on that later) which allows designers to try, to fail, and to learn what works. Testing also involves customers, and that continued involvement provides essential user feedback on potential designs and use cases. If the MIT-Altitude team studying walkers had ended user involvement after its initial interviews, it would likely have ended up with a walker that didn’t work very well for customers.

It is also important to interview and understand other stakeholders, like people selling the product, or those who are supporting the users throughout the product life cycle.

The second phase of design thinking is developing solutions to the problem (which you now fully understand). This begins with what most people know as brainstorming.

Hold nothing back during brainstorming sessions — except criticism. Infeasible ideas can generate useful solutions, but you’d never get there if you shoot down every impractical idea from the start.

“One of the key principles of brainstorming is to suspend judgment,” Eppinger said. “When we're exploring the solution space, we first broaden the search and generate lots of possibilities, including the wild and crazy ideas. Of course, the only way we're going to build on the wild and crazy ideas is if we consider them in the first place.”

That doesn’t mean you never judge the ideas, Eppinger said. That part comes later, in downselection. “But if we want 100 ideas to choose from, we can’t be very critical.”

In the case of The Good Kitchen, the kitchen employees were given new uniforms. Why? Uniforms don’t directly affect the competence of the cooks or the taste of the food.

But during interviews conducted with kitchen employees, designers realized that morale was low, in part because employees were bored preparing the same dishes over and over again, in part because they felt that others had a poor perception of them. The new, chef-style uniforms gave the cooks a greater sense of pride. It was only part of the solution, but if the idea had been rejected outright, or perhaps not even suggested, the company would have missed an important aspect of the solution.

Prototype and test. Repeat.

You’ve defined the problem. You’ve spoken to customers. You’ve brainstormed, come up with all sorts of ideas, and worked with your team to boil those ideas down to the ones you think may actually solve the problem you’ve defined.

“We don’t develop a good solution just by thinking about a list of ideas, bullet points and rough sketches,” Eppinger said. “We explore potential solutions through modeling and prototyping. We design, we build, we test, and repeat — this design iteration process is absolutely critical to effective design thinking.”

Repeating this loop of prototyping, testing, and gathering user feedback is crucial for making sure the design is right — that is, it works for customers, you can build it, and you can support it.

“After several iterations, we might get something that works, we validate it with real customers, and we often find that what we thought was a great solution is actually only just OK. But then we can make it a lot better through even just a few more iterations,” Eppinger said.

Implementation

The goal of all the steps that come before this is to have the best possible solution before you move into implementing the design. Your team will spend most of its time, its money, and its energy on this stage.

“Implementation involves detailed design, training, tooling, and ramping up. It is a huge amount of effort, so get it right before you expend that effort,” said Eppinger.

Design thinking isn’t just for “things.” If you are only applying the approach to physical products, you aren’t getting the most out of it. Design thinking can be applied to any problem that needs a creative solution. When Eppinger ran into a primary school educator who told him design thinking was big in his school, Eppinger thought he meant that they were teaching students the tenets of design thinking.

“It turns out they meant they were using design thinking in running their operations and improving the school programs. It’s being applied everywhere these days,” Eppinger said.

In another example from the education field, Peruvian entrepreneur Carlos Rodriguez-Pastor hired design consulting firm IDEO to redesign every aspect of the learning experience in a network of schools in Peru. The ultimate goal? To elevate Peru’s middle class.

As you’d expect, many large corporations have also adopted design thinking. IBM has adopted it at a company-wide level, training many of its nearly 400,000 employees in design thinking principles .

What can design thinking do for your business?

The impact of all the buzz around design thinking today is that people are realizing that “anybody who has a challenge that needs creative problem solving could benefit from this approach,” Eppinger said. That means that managers can use it, not only to design a new product or service, “but anytime they’ve got a challenge, a problem to solve.”

Applying design thinking techniques to business problems can help executives across industries rethink their product offerings, grow their markets, offer greater value to customers, or innovate and stay relevant. “I don’t know industries that can’t use design thinking,” said Eppinger.

Ready to go deeper?

Read “ The Designful Company ” by Marty Neumeier, a book that focuses on how businesses can benefit from design thinking, and “ Product Design and Development ,” co-authored by Eppinger, to better understand the detailed methods.

Register for an MIT Sloan Executive Education course:

Systematic Innovation of Products, Processes, and Services , a five-day course taught by Eppinger and other MIT professors.

- Leadership by Design: Innovation Process and Culture , a two-day course taught by MIT Integrated Design and Management director Matthew Kressy.

- Managing Complex Technical Projects , a two-day course taught by Eppinger.

- Apply for M astering Design Thinking , a 3-month online certificate course taught by Eppinger and MIT Sloan senior lecturers Renée Richardson Gosline and David Robertson.

Steve Eppinger is a professor of management science and innovation at MIT Sloan. He holds the General Motors Leaders for Global Operations Chair and has a PhD from MIT in engineering. He is the faculty co-director of MIT's System Design and Management program and Integrated Design and Management program, both master’s degrees joint between the MIT Sloan and Engineering schools. His research focuses on product development and technical project management, and has been applied to improving complex engineering processes in many industries.

Read next: 10 agile ideas worth sharing

Related Articles

A complete guide to the design thinking process

Learn the five stages of the design thinking process, get practical tips to apply them, and get templates to seamlessly run design thinking exercises.

How many projects have you worked on that stalled because your team couldn’t align on the best path forward? How many more got shelved because they didn’t meet user needs or expectations? And how many got delayed in rounds and rounds of never-ending feedback?

Thankfully, you don’t have to keep repeating those experiences month after month. The (not so) secret weapon: design thinking .

Design thinking gives teams a new way to approach their projects and overcome some of those well-known challenges. It can help teams understand their users' needs and challenges, then apply those learnings to solve problems in a creative, innovative way. Understanding design thinking can transform your team’s problem-solving approach — and how you work together.

What is design thinking?

Design thinking is an iterative process where teams seek to understand user needs, challenge assumptions, define complex problems to solve, and develop innovative solutions to prototype and test. The goal of design thinking is to come up with user-focused solutions tailored to the particular problem at hand.

While often used in product design, service design, and customer experience, you can use design thinking in virtually any situation, industry, or organization to create user-centric solutions to specific problems.

Design thinking process 101: Definitions and approaches

The design thinking process puts customers’ and users’ needs at the center and aims to solve challenges from their perspective.

Design thinking typically follows five distinct stages:

Empathize stage

The first stage of design thinking lays the foundation for the rest of the process because it focuses on the needs of the real people using your product. At this stage, you want to get familiar with the people experiencing the problems you’re trying to solve, understanding their point of view, and learning about their user experience. You want to understand their challenges and what they need from your product or company to address them.

The goal of this stage is for your team to develop a user-centered vision of the core problem you need to solve. The idea is to challenge any assumptions or biases teams have, instead using their customer perspective as a guiding source. This is important because it aligns the team on what needs to be considered during the rest of the design thinking process.

To help you get a solid understanding of the problems you’re solving, you can ask a lot of questions to build empathy with your users. These will invite people to share their experiences and observations to help your team better understand the problem. Then, you can move on to some specific exercises for the empathy stage of the process.

As you build up your understanding of your users, it's helpful to visualize their experience. A common way to do this is to assemble a customer journey map . This helps identify areas of friction and understand customer preferences.

Learn more: 7 types of questions to build empathy for design thinking

Ideate stage

Your priority here is to think outside the box and source as many ideas as possible from all areas of the business. Bring in people from different departments so you benefit from a wider range of experiences and perspectives during ideation sessions. Don’t worry about coming up with concrete solutions or how to implement each one — you’ll build on that later. The goal is to explore new and creative ideas rather than come up with an actual plan.

Key steps in the ideation phase:

- Define your problem : Creating a problem statement ensures that your team can focus on solving the right problem and staying aligned with your end-user or customer’s problem

- Start ideating : Choose a brainstorming technique to help organize team participation that fits your goal (More on that in the next section.)

- Prioritize your ideas : Once you have several ideas, prioritize them based on how well they take into account the customer’s needs

- Choose the best solution : Choose the best ideas to move forward to either the define stage or the prototype stage

Learn more: The ideation stage of design thinking: What you need to know

Your priority here is to generate as many ideas as possible, without judging or evaluating them. This step encourages designers to think creatively and push the boundaries of what's possible. We’ve put together a list of different brainstorming techniques to help your teams come up with creative new ideas.

Put it into practice: How to facilitate a brainstorming session

Prototyping stage

At this stage, your team’s goal is to remove uncertainty around your proposed solutions. This is where you start thinking about them in more detail, including how you’ll bring them to life. Your prototypes should help the team understand if the design or solution will work as it’s intended to.

Here, the focus is on speed and efficiency — you don’t want to invest a ton of time or resources into these solutions yet because you’re not sure they’re the best ones for the problem you’re trying to solve. You just need a functional, interactive prototype that can prove your concept. These are learning opportunities to help you spot any issues or opportunities before you take it any further.

Learn more: A guide to prototyping: the 4th stage of design thinking

Testing stage

The testing stage is normally one of the last stages of the design thinking process. After you’ve developed a concept or prototype, you need to test it in the real-world to understand its viability and usability. It’s where your product, design, or development teams evaluate the creative solutions they’ve come up with, to see how real users interact with them.

Testing your concepts and observing how people interact with them helps you understand whether or not the prototype solves real problems and meets their needs, before you invest in it fully.

However, design thinking is an iterative process: You may go through the ideation, prototyping, and testing phases multiple times to improve and refine your solutions as you learn more from your users.

Read the guide: Testing: A guide to the 5th stage of design thinking

The relationship between human-centered design and design thinking

These two terms are often used together, because they complement one another. However, they’re two different things, so understanding their differences is important.

Simply put, design thinking is a working process, while human-centered design is a mindset or approach.

The first step in finding success with design thinking is to foster a culture of human-centered design within your team. This is because design thinking focuses so heavily on the users and customers — the people using your product or service.

To inspire your team, we’ve put together four human-centered design examples — and explain why they work so well.

Benefits of design thinking

For organizations who’ve never run a design thinking workshop before, it can feel like a big change in how you approach the design process. But it can offer many benefits for your business.

Foster a true design culture within your organization

Design thinking is an iterative process — it’s not something you do once and call it done. The more you do it, the more you’ll see a design-focused culture emerge within your organization, which is much more effective than going to one-off creative retreats or setting up expensive innovation centers that no one ever uses.

This mindset and cultural shift can help scale design thinking within the business. But it’s important to know how to avoid some of the pitfalls companies can face when trying to create a design culture internally.

Learn more: How to use the LUMA System of Innovation for everyday design thinking

Encourage collaboration across departments

Design thinking isn’t just for the designers on the team. The earlier stages of the process — Empathize, Define, and Ideate — are perfect for bringing in people from across the business. In fact, bringing in varied viewpoints and perspectives can help you come up with more creative or effective solutions.

You can use the design thinking process to get more people involved, and help everyone contribute ideas.

Improve understanding of user needs

So many companies say they’re “customer focused,” but lack a clear understanding of what really matters most to their customers in the context of their product or service. Design thinking puts the user front and center, with the Empathize stage dedicated to understanding and discovering user needs.

Learn more: How to identify user needs and pain points

Skills and behaviors needed for successful design thinking

To get the most out of a design thinking exercise, you’ll need a collaborative and creative mindset within your team. The team needs to be willing to explore new ideas, and laser-focused on customer or user needs.

Here are some specific skills to help your design thinking process run smoothly.

Divergent and convergent thinking

Divergence and convergence is a human-centered design approach to problem-solving. It switches between expansive and focused thinking, giving you a process that balances understanding people’s problems and developing solutions.

It focuses on understanding a user's needs, behaviors, and motivations, to help you develop empathy for their problems. Then, it encourages experimentation and iteration to help you effectively design solutions to meet those needs.

Collaborative working

Design thinking isn’t a solo activity. You’ll bring in people from different teams or business areas. To get the most out of the process, everyone needs to collaborate and communicate effectively. Teams that are good at collaborating drive the best outcomes, while also making it an enjoyable experience working together.

There are several core collaboration skills your team needs to succeed:

- Open-mindedness

- Communication

- Adaptability

- Organization

- Time management

Learn more about why these skills are so important and how you can improve them individually or as a team: 7 collaboration skills your team needs to succeed

Participatory or collaborative design

For many design teams and creative folks, the idea of designing something with other people can be enough to make them shudder. “Design by committee” is their idea of a nightmare. But the design thinking process isn’t about “making the logo 10% bigger” or “using a different shade of blue.” It’s user- and solution-focused.

You’ll get the best outcomes if you bring insights, perspectives, and expertise from multiple stakeholders. That includes at the Prototype and Test stages, as everyone will have ideas to contribute to help you bring solutions to life.

Learn more: What is co-design? A primer on participatory design

Common challenges in design thinking

If your team hasn’t mastered or fully committed to each one of the design thinking steps, you may encounter problems that make it harder to reap the benefits of design thinking.

Here are 4 common challenges that teams face when implementing design thinking practices.

- A company culture that doesn't foster collaboration

- An inability to adjust to non-linear processes

- A lack of in-depth user research

- Getting too invested in a single idea

Learn how to address these in Mural's guide on design thinking challenges .

Design thinking tools and templates to help you get started

Using mural for design thinking.

There are lots of tools you can use to run design thinking workshops — including Mural. We help designers work as effectively as possible, so they can get to better solutions quicker. We’ve incorporated some design thinking shortcuts and “hidden” features into our application, making it perfect for in-person or remote (or even asynchronous) collaborative sessions. These include:

- Use the C-key shortcut to quickly connect ideas with arrows

- Seamlessly import existing information from spreadsheets

- Duplicate elements you already created for faster visualization

- Fit your canvas to your screen and zoom in

- Get even more options using the right-click menu

And to help you get started, we’ve hand-picked some Mural templates relevant to each stage of the design process below.

Templates for the Empathy stage

The empathy map template helps you visualize the thoughts, feelings, and actions of your customersto help you develop a better understanding of the their experiences. The map is divided into four quadrants, where you record the following:

- Thoughts: the customer’s internal dialogue and beliefs

- Feelings: the customer’s emotional responses

- Actions: the customer’s actions and behaviors

- Observations: what the customer is seeing and hearing.

Try Mural’s empathy map template

Templates for the Define stage

This exercise helps you understand a situation or problem by identifying what’s working, what’s not, and areas for improvement. You start by listing out the problem, then identifying the positive aspects (the rose), negatives (thorn), and possible solutions for improvement (the buds).

You can use this template to run the exercise individually or in groups. It gives you a way to gather new ideas and perspectives on the problem you’re solving in real-time.

Try Mural’s Rose, thorn, bud template

Templates for the Ideate stage

The round robin brainstorming exercise is a collaborative session where every person contributes multiple ideas. This is a great way to come up with lots of different ideas and solutions in the ideation stage of design thinking, where you’re focusing on quantity and creativity.

Bringing in ideas from every team member encourages people to share their unique perspectives, and can also help you avoid groupthink.

Try Mural’s Round robin template

Templates for the Prototype stage

This template helps you map out how an idea will work in practice, as a functional system. Schematic diagramming is very flexible, so it can be used in many types of projects to make sure your idea is structurally sound. It can help you map out workflows and identify any decisions you need to make to bring your idea to life.

Try Mural’s Schematic diagramming template

Templates for the Test stage

In think aloud testing, users test out a product or prototype and talk through the relevant tasks as they complete them. You can use this template to record the feedback, insights, and experiences of your testers, and identify the success and failure points in your proposed solution.

Try Mural’s Think aloud testing template

Design thinking examples: What it looks like in practice

Design thinking is a very flexible approach that works for companies of any size, from large enterprises to small startups.

Here are some examples of how companies use design thinking, for many types of creative projects.

IBM uses design thinking to design at scale

IBM was traditionally an engineering-led organization, but now it's shifting its focus onto design, working to spread a design culture throughout the business. One of the main ways of doing that is by launching IBM Design Camps.

These camps are comprehensive educational programs that help people understand the concept of design thinking and how it specifically works at IBM.

Learn more about how IBM runs design thinking workshops with remote or distributed teams .

Somersault Innovation uses design thinking to transform its sales process

Somersault Innovation has used design thinking methods to help their sales team co-create solutions with their customers. It’s helped sellers become more customer-centric.

Now, their sellers can create mutual success plans with their prospects, making it easier for them to find a path forward together.

Mural uses design thinking to drive growth

At Mural, our marketing team is constantly following new trends, evaluating metrics, and working to deliver the best experiences for our customers. Design thinking helps us adopt a customer-centric approach by ensuring that we're focused on the right problems. This helps us have the biggest impact on the company’s long-term growth while creating the most value for our users.

David J. Bland planned a book using the design thinking methodology

It’s not just visual creative projects that can benefit from the design thinking process. Founder, speaker, and author David J. Bland used the methodology to plan out his book and collaborate with other team members in the process. In addition to helping him refine and adjust the structure, Bland also used it to gather feedback from early readers and target audiences, which helped get the final product just right.

Support design thinking with tools that facilitate creative collaboration

While we’ve covered some of the skills and behaviors you need to successfully run design thinking exercises, having the right tools can help a lot, too. A collaborative platform helps teams communicate, share ideas, and turn those ideas into solutions together.

Mural helps teams visualize their ideas in a collaboration platform that unlocks teamwork . This helps everyone stay on the same page, while giving them the ability to add their own ideas freely and easily. Mural facilitates effective collaboration both in person and remotely, making it ideal for design thinking workshops for co-located and distributed teams. Plus, it has tons of ready-to-use templates (like the ones we listed above) to help you get started.

Ready to give it a try? Start your Free Forever account today, and run your next design thinking workshop in Mural.

About the authors

Bryan Kitch

Tagged Topics

Related blog posts

4 common challenges and pitfalls in design thinking

.jpg)

How to encourage thinking outside the box

What Is hybrid work? A primer on the new way of working

Related blog posts.

How to document a process: 9 steps and best practices

%20(2).jpg)

What is remote collaboration & how to make it work for your team

.jpg)

Understanding the 5 phases of project management

What is design thinking?

Design and conquer: in years past, the word “design” might have conjured images of expensive handbags or glossy coffee table books. Now, your mind might go straight to business. Design and design thinking are buzzing in the business community more than ever. Until now, design has focused largely on how something looks; these days, it’s a dynamic idea used to describe how organizations can adjust their problem-solving approaches to respond to rapidly changing environments—and create maximum impact and shareholder value. Design is a journey and a destination. Design thinking is a core way of starting the journey and arriving at the right destination at the right time.

Simply put, “design thinking is a methodology that we use to solve complex problems , and it’s a way of using systemic reasoning and intuition to explore ideal future states,” says McKinsey partner Jennifer Kilian. Design thinking, she continues, is “the single biggest competitive advantage that you can have, if your customers are loyal to you—because if you solve for their needs first, you’ll always win.”

Get to know and directly engage with senior McKinsey experts on design thinking

Tjark Freundt is a senior partner in McKinsey’s Hamburg office, Tomas Nauclér is a senior partner in the Stockholm office, Daniel Swan is a senior partner in the Stamford office, Warren Teichner is a senior partner in the New York office, Bill Wiseman is a senior partner in the Seattle office, and Kai Vollhardt is a senior partner in the Munich office.

And good design is good business. Kilian’s claim is backed up with data: McKinsey Design’s 2018 Business value of design report found that the best design performers increase their revenues and investor returns at nearly twice the rate of their industry competitors. What’s more, over a ten-year period, design-led companies outperformed the S&P 500 by 219 percent.

As you may have guessed by now, design thinking goes way beyond just the way something looks. And incorporating design thinking into your business is more than just creating a design studio and hiring designers. Design thinking means fundamentally changing how you develop your products, services, and, indeed, your organization itself.

Read on for a deep dive into the theory and practice of design thinking.

Learn more about McKinsey’s Design Practice , and check out McKinsey’s latest Business value of design report here .

How do companies build a design-driven company culture?

There’s more to succeeding in business than developing a great product or service that generates a financial return. Empathy and purpose are core business needs. Design thinking means putting customers, employees, and the planet at the center of problem solving.

McKinsey’s Design Practice has learned that design-led organizations start with design-driven cultures. Here are four steps to building success through the power of design:

Understand your audience. Design-driven companies go beyond asking what customers and employees want, to truly understanding why they want it. Frequently, design-driven companies will turn to cultural anthropologists and ethnographers to drill down into how their customers use and experience products, including what motivates them and what turns them away.

Makeup retailer Sephora provides an example. When marketing leaders actually watched shoppers using the Sephora website, they realized customers would frequently go to YouTube to watch videos of people using products before making a purchase. Using this information, the cosmetics retailer developed its own line of demonstration videos, keeping shoppers on the site and therefore more likely to make a purchase.

- Bring design to the executive table. This leader can be a chief design officer, a chief digital officer, or a chief marketing officer. Overall, this executive should be the best advocate for the company’s customers and employees, bringing the point of view of the people, the planet, and the company’s purpose into strategic business decisions. The design lead should also build bridges between multiple functions and stakeholders, bringing various groups into the design iteration process.

- Design in real time. To understand how and why people—both customers and employees—use processes, products, or services, organizations should develop a three-pronged design-thinking model that combines design, business strategy, and technology. This approach allows business leaders to spot trends, cocreate using feedback and data, prototype, validate, and build governance models for ongoing investment.

Act quickly. Good design depends on agility. That means getting a product to users quickly, then iterating based on customer feedback. In a design-driven culture, companies aren’t afraid to release products that aren’t quite perfect. Designers know there is no end to the design process. The power of design, instead, lies in the ability to adopt and adapt as needs change. When designers are embedded within teams, they are uniquely positioned to gather and digest feedback, which can lead to unexpected revelations. Ultimately, this approach creates more impactful and profitable results than following a prescribed path.

Consider Instagram. Having launched an initial product in 2010, Instagram’s founders paid attention to what the most popular features were: image sharing, commenting, and liking. They relaunched with a stripped-down version a few months later, resulting in 100,000 downloads in less than a week and over two million users in under two months —all without any strategic promotion.

Learn more about McKinsey’s Design Practice .

What’s the relationship between user-centered design and design thinking?

Both processes are design led. And they both emphasize listening to and deeply understanding users and continually gathering and implementing feedback to develop, refine, and improve a service.

Where they are different is scale. User-centered design focuses on improving a specific product or service . Design thinking takes a broader view as a way to creatively address complex problems—whether for a start-up, a large organization, or society as a whole.

User-centered design is great for developing a fantastic product or service. In the past, a company could coast on a superior process or product for years before competitors caught up. But now, as digitization drives more frequent and faster disruptions, users demand a dynamic mix of product and service. Emphasis has shifted firmly away from features and functions toward purpose, lifestyle, and simplicity of use.

Introducing McKinsey Explainers : Direct answers to complex questions

McKinsey analysis has found that some industries—such as telecommunications, automotive, and consumer product companies— have already made strides toward combining product and service into a unified customer experience . Read on for concrete examples of how companies have applied design thinking to offer innovative—and lucrative—customer experiences.

Learn more about our Operations Practice .

What is the design-thinking process?

McKinsey analysis has shown that the design-thinking approach creates more value than conventional approaches. The right design at the right price point spurs sustainability and resilience in a demonstrable way—a key driver of growth.

According to McKinsey’s Design Practice, there are two key steps to the design-thinking process:

- Developing an understanding of behavior and needs that goes beyond what people are doing right now to what they will need in the future and how to deliver that. The best way to develop this understanding is to spend time with people.

- “Concepting,” iterating, and testing . First start with pen and paper, sketching out concepts. Then quickly put these into rough prototypes—with an emphasis on quickly. Get feedback, refine, and test again. As American chemist Linus Pauling said : “The way to get good ideas is to get lots of ideas and throw the bad ones away.”

What is D4VG versus DTV?

For more than a decade, manufacturers have used a design-to-value (DTV) model to design and release products that have the features needed to be competitive at a low cost. During this time, DTV efforts were groundbreaking because they were based on data rather than experience. They also reached across functions, in contrast to the typical value-engineering approach.

The principles of DTV have evolved into design for value and growth (D4VG), a new way of creating products that provide exceptional customer experiences while driving both value and growth. Done right, D4VG efforts generate products with the features, form, and functionality that turn users into loyal fans .

D4VG products can cost more to build, but they can ultimately raise margins by delivering on a clear understanding of a product’s core brand attributes, insights into people’s motivations, and design thinking.

Learn more about our Consumer Packaged Goods Practice .

What is design for sustainability?

As consumers, companies, and regulators shift toward increased sustainability, design processes are coming under even more scrutiny. The challenge is that carbon-efficient production processes tend to be more complex and can require more carbon-intensive materials. The good news is that an increased focus on design for sustainability (DFS), especially at the research and development stage , can help mitigate some of these inefficiencies and ultimately create even more sustainable products.

For example, the transition from internal-combustion engines to electric-propulsion vehicles has highlighted emissions-intensive automobile production processes. One study found that around 20 percent of the carbon generated by a diesel vehicle comes from its production . If the vehicle ran on only renewable energy, production emissions would account for 85 percent of the total. With more sustainable design, electric-vehicle (EV) manufacturers stand to reduce the lifetime emissions of their products significantly.

To achieve design for sustainability at scale, companies can address three interrelated elements at the R&D stage:

- rethinking the way their products use resources, adapting them to changing regulations, adopting principles of circularity, and making use of customer insights

- understanding and tracking emissions and cost impact of design decisions in support of sustainability goals

- fostering the right mindsets and capabilities to integrate sustainability into every product and design decision

What is ‘skinny design’?

Skinny design is a less theoretical aspect of design thinking. It’s a method whereby consumer goods companies reassess the overall box size of products by reducing the total cubic volume of the package. According to McKinsey analysis , this can improve overall business performance in the following ways:

- Top-line growth of 4 to 5 percent through improvements in shelf and warehouse holding power. The ability to fit more stock into warehouses ultimately translates to growth.

- Bottom-line growth of more than 10 percent . Packing more product into containers and trucks creates the largest savings. Other cost reductions can come from designing packaging to minimize the labor required and facilitate automation.

- Sustainability improvements associated with reductions in carbon emissions through less diesel fuel burned per unit. Material choices can also confer improvements to the overall footprint.

Read more about skinny design and how it can help maximize the volume of consumer products that make it onto shelves.

Learn more about McKinsey’s Operations Practice .

How can a company become a top design performer?

The average person’s standard for design is higher than ever. Good design is no longer just a nice-to-have for a company. Customers now have extremely high expectations for design, whether it’s customer service, instant access to information, or clever products that are also aesthetically relevant in the current culture.

McKinsey tracked the design practices of 300 publicly listed companies over a five-year period in multiple countries. Advanced regression analysis of more than two million pieces of financial data and more than 100,000 design actions revealed 12 actions most correlated to improved financial performance. These were then clustered into the following four themes:

- Analytical leadership . For the best financial performers, design is a top management issue , and design performance is assessed with the same rigor these companies use to approach revenue and cost. The companies with the top financial returns have combined design and business leadership through bold, design-centric visions. These include a commitment to maintain a baseline level of customer understanding among all executives. The CEO of one of the world’s largest banks, for example, spends one day a month with the bank’s clients and encourages all members of the company’s C-suite to do the same.

- Cross-functional talent . Top-performing companies make user-centric design everyone’s responsibility, not a siloed function. Companies whose designers are embedded within cross-functional teams have better overall business performance . Further, the alignment of design metrics with functional business metrics (such as financial performance, user adoption rates, and satisfaction results) is also correlated to better business performance.

- Design with people, not for people . Design flourishes best, according to our research, in environments that encourage learning, testing, and iterating with users . These practices increase the odds of creating breakthrough products and services, while at the same time reducing the risk of costly missteps.

- User experience (UX) . Top-quartile companies embrace the full user experience by taking a broad-based view of where design can make a difference. Design approaches like mapping customer journeys can lead to more inclusive and sustainable solutions.

What are some real-world examples of how design thinking can improve efficiency and user experience?

Understanding the theory of design thinking is one thing. Seeing it work in practice is something else. Here are some examples of how elegant design created value for customers, a company, and shareholders:

- Stockholm’s international airport, Arlanda, used design thinking to address its air-traffic-control problem. The goal was to create a system that would make air traffic safer and more effective. By understanding the tasks and challenges of the air-traffic controllers, then collaboratively working on prototypes and iterating based on feedback, a working group was able to design a new departure-sequencing tool that helped air-traffic controllers do their jobs better. The new system greatly reduced the amount of time planes spent between leaving the terminal and being in the air, which in turn helped reduce fuel consumption.

- When Tesla creates its electric vehicles , the company closely considers not only aesthetics but also the overall driving experience .

- The consumer electronics industry has a long history of dramatic evolutions lead by design thinking. Since Apple debuted the iPhone in 2007, for example, each new generation has seen additional features, new customers, and lower costs—all driven by design-led value creation .

Learn more about our Consumer Packaged Goods and Sustainability Practices.

For a more in-depth exploration of these topics, see McKinsey’s Agile Organizations collection. Learn more about our Design Practice —and check out design-thinking-related job opportunities if you’re interested in working at McKinsey.

Articles referenced:

- “ Skinny design: Smaller is better ,” April 26, 2022, Dave Fedewa , Daniel Swan , Warren Teichner , and Bill Wiseman

- “ Product sustainability: Back to the drawing board ,” February 7, 2022, Stephan Fuchs, Stephan Mohr , Malin Orebäck, and Jan Rys

- “ Emerging from COVID-19: Australians embrace their values ,” May 11, 2020, Lloyd Colling, Rod Farmer , Jenny Child, Dan Feldman, and Jean-Baptiste Coumau

- “ The business value of design ,” McKinsey Quarterly , October 25, 2018, Benedict Sheppard , Hugo Sarrazin, Garen Kouyoumjian, and Fabricio Dore

- “ More than a feeling: Ten design practices to deliver business value ,” December 8, 2017, Benedict Sheppard , John Edson, and Garen Kouyoumjian

- “ Creating value through sustainable design ,” July 25, 2017, Sara Andersson, David Crafoord, and Tomas Nauclér

- “ The expanding role of design in creating an end-to-end customer experience ,” June 6, 2017, Raffaele Breschi, Tjark Freundt , Malin Orebäck, and Kai Vollhardt

- “ Design for value and growth in a new world ,” April 13, 2017, Ankur Agrawal , Mark Dziersk, Dave Subburaj, and Kieran West

- “ The power of design thinking ,” March 1, 2016, Jennifer Kilian , Hugo Sarrazin, and Barr Seitz

- “ Building a design-driven culture ,” September 1, 2015, Jennifer Kilian , Hugo Sarrazin, and Hyo Yeon

Want to know more about design thinking?

Related articles.

Skinny design: Smaller is better

The business value of design

More than a feeling: Ten design practices to deliver business value

Designorate

Design thinking, innovation, user experience and healthcare design

Guide for Critical Thinking for Designers

In every single day in our life, we are faced with a number of choices to make, problems to solve, and ideas to evaluate or analyze. However, these activities are affected by both internal and external factors such as biases, incomplete information, distortion, and prejudices. All these factors affect the process of choosing the right decision or find the proper solution for problems, which may lead to misleading solutions or choices. In order to escape this idea trap, critical thinking can provide a way to alter our mindset in order to improve the way we think of problem or situations which subsequently reflect positively on our decisions.

Critical thinking is a thinking method that aims to achieve objective evaluation and analysis of problems, ideas, or different situations in order to build a clear unbiased understanding about it over the course of reaching the optimal solution. The critical thinking is a self-disciplined, self-directed, self-monitored, and self-corrective way of thinking to improve how we communicate ideas and solve problems.

Critical thinking is a handy method to address any situation before jumping directly to the analysis phase in order to evaluate or find a solution for it. This type of thinking is commonly used in different fields of science and art in order to build a clear objective perception about different situations that face designers, engineers and researchers.

Related articles:

- 6 Steps for Effective Critical Thinking

- The Six Hats of Critical Thinking and How to Use Them

Principles of Critical Thinking

In order to achieve the target behind the critical thinking approach, the below principles were introduced by Professor Larry Larson, Ohio University, in his paper published in the Journal of Biological Education 1990. These principles provides guidelines for critical thinking before moving to the thinking steps:

- Collect all the necessary information about the situation in hand

- Understand and clearly, define all terms associated with the situation

- Question the methods used to collect the information and the current conclusions

- Understand the hidden assumptions and biases including your own biases and values

- Question the source of facts

- Don’t expect all the answers

- Look at the big picture of the situation rather than the parts

- Examine the multiples cause and effect

- Watch for thought stoppers

The above principles aim to free our mind from biases and ensure that the situation is clearly defined. Also, it aims to ensure that the source of the data collected, the methods used to collect the data are also free from mistakes, biases, and inaccuracy. This can help us to focus on the problem without any external factors.

Stages of Critical Thinking

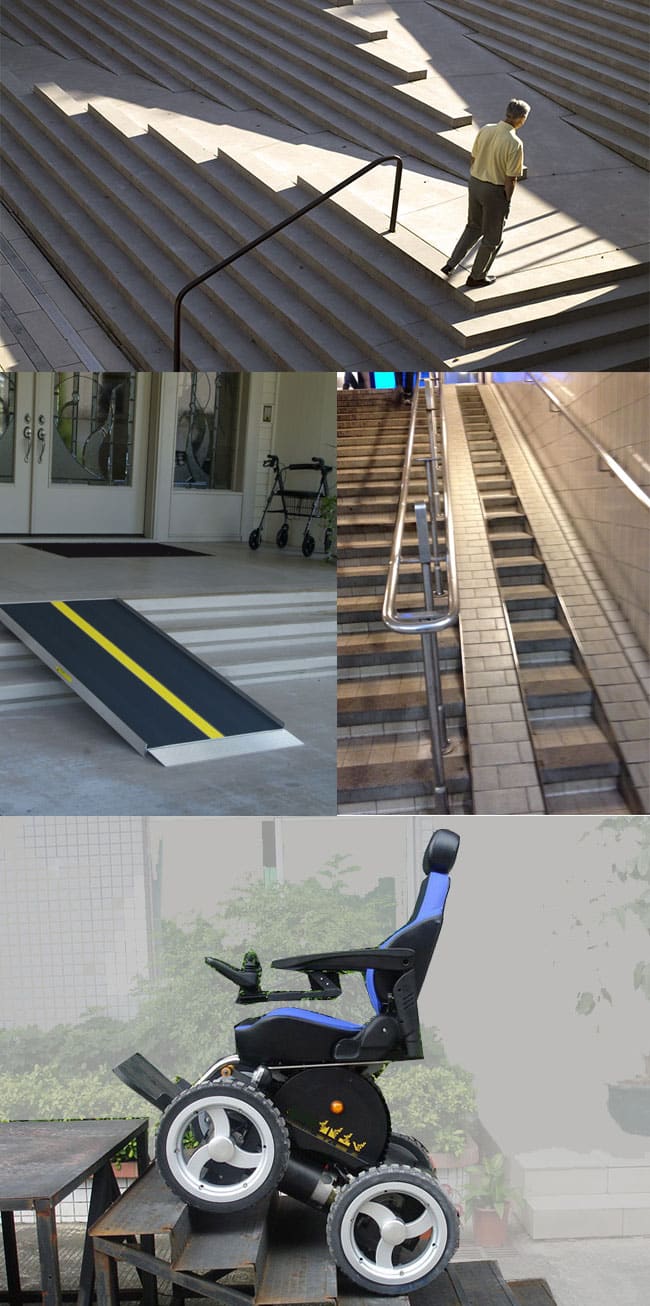

Based on the above principles, the critical thinking process should have three main stages; Observe, Question, and Answer . In order to clearly understand the three stages, we will use a design example: how people with wheelchair use the stairs to move from one level to another. Many places are still not accessible for people with physical disabilities due to the hard usage of stairs as they always seek support from others or search fo electric elevators. Based on this situation, we would like to explore how to address this problem with the critical thinking, we can use the stages as below:

Stage 1: Observe

In this stage, we observe the whole situation thoroughly in terms of how people with disabilities use the stairs, the problems they face, and how they currently deal with it. At this stage, we collect all the necessary information about the current situation and how other people tried to solve it and the methods they used to achieve this target. At this stage, no questions are asked as we only observe and record our observation for the next stages.

While collecting information and observing the situation, we should take notes of our findings with a clear definition of the problem in order to ensure that we are addressing the problem properly. Also, we need to understand the biases that may affect our decision and the biases that may affect other designers who tried to solve the problem. This can help us to put the biases or the assumption aside and focus on the situation.

In the example we have, designers should observe how people with wheelchairs use the stairs and exactly define the problem they face and how they are trying to solve it. Also, we need to explore the previous researchers or attempt that tried to solve the problem and their fingers.

Stage 2: Question

Based on the observation, we start to ask questions about the situation and the current solution. For example, what is the wrong with the current stars? why people find it hard to use? These questions help clearly define the right problem to address and subsequently finding the solution that can directly build a holistic solution that considers all the facts regarding the user experience, surrounded environment, and other users in the place.

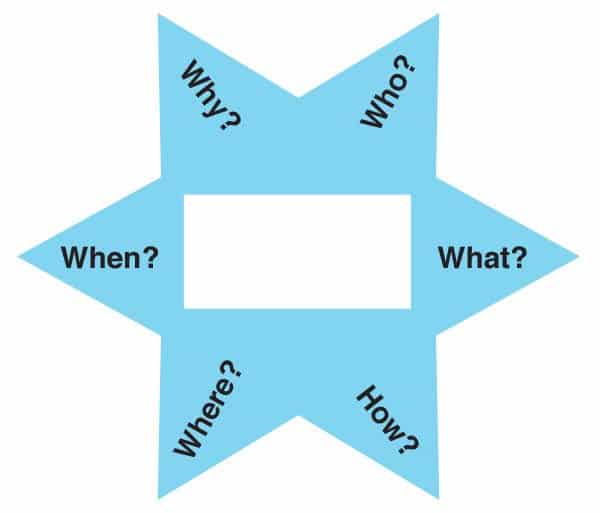

Asking the right questions contribute reaching a clear definition for the current situation and subsequently analyzing it properly. The questions may take different forms. One of the methods that can help exploring the situation from different aspects is the Starbursting method that allows you to cover the topic using five main types of questions; Why, Who, What, How, Where, and When. In this example, the questions can be organized as below:

- Who: Who is using the target user of the stairs?

- What: What is the current problem of using the stairs? What are the different approaches to solving the problem?

- How: How can we solve the problem? How can we make the stairs using experience easier for disabled people?

- Where: Where will the new idea be applied?

- When: When do disabled people use the stairs the most?

- Why: Why do we need to change the current stars design? Why disabled people suffer much from using the current stairs?

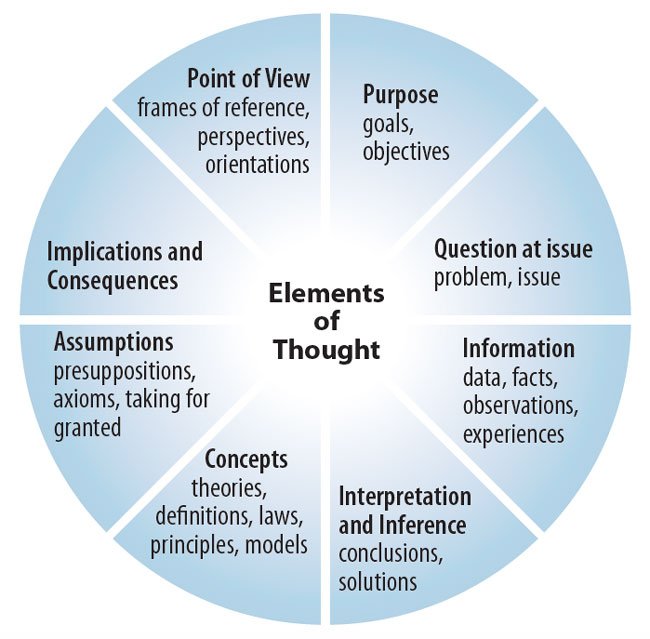

Another method to ask the right questions is to use the Elements of Thought, which reflect how we think about situations. The Elements of Thoughts include purpose, questions, information, concussions, concepts, assumptions, implications, and points of view.

These elements can form the way we think in situations. These elements can be used to form the right questions as following:

- Purpose: What are we trying to solve?

- Questions: What are the questions?

- Information: What is the information needed to understand the problem?

- Conclusions: How do other reached different solutions?

- Concepts: What is the main concept behind the current ideas?

- Assumptions: What is the assumption we have this problem?

- Implications: How can we implicate the new ideas?

- The point of View: What are the different point of views related to the problem?

The third step in the critical thinking is to answer all the raised questions without any biases, prejudices, or assumptions. At this stage, we build a deep understanding of the problem where we can move forward with the steps required to the find the solution for the problem. In the above example, the solution can include placing the elevator next to the stairs so disabled people can easily find it, or using sliding area next to the stairs so they can easily use their wheelchairs.

Designers are faced with daily challenges to explore problems, observe current situations, or find solutions to improve products and services. Critical thinking provides a method to explore different situations with eliminating any chances for biases, prejudice, or misleading information. The critical thinking is a great method to understand the situation in order to analyze it to define the problems and prototype solutions.

Wait, Join my Newsletters!

As always, I try to come to you with design ideas, tips, and tools for design and creative thinking. Subscribe to my newsletters to receive new updated design tools and tips!

Dr Rafiq Elmansy

As an academic and author, I've had the privilege of shaping the design landscape. I teach design at the University of Leeds and am the Programme Leader for the MA Design, focusing on design thinking, design for health, and behavioural design. I've developed and taught several innovative programmes at Wrexham Glyndwr University, Northumbria University, and The American University in Cairo. I'm also a published book author and the proud founder of Designorate.com, a platform that has been instrumental in fostering design innovation. My expertise in design has been recognised by prestigious organizations. I'm a fellow of the Higher Education Academy (HEA), the Design Research Society (FDRS), and an Adobe Education Leader. Over the course of 20 years, I've had the privilege of working with esteemed clients such as the UN, World Bank, Adobe, and Schneider, contributing to their design strategies. For more than 12 years, I collaborated closely with the Adobe team, playing a key role in the development of many Adobe applications.

You May Also Like

7 Steps to Create a Successful Journey Map

Webinar: Prototyping Using Adobe Experience Design

SWOT Analysis: Exploring Innovation and Creativity within Organizations

Creative Problem Solving: How to Turn Challenges into Opportunities

A Guide to the SCAMPER Technique for Design Thinking

Top Resources to Learn Design Thinking Online

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Sign me up for the newsletter!

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Right Way to Lead Design Thinking

- Christian Bason

- Robert D. Austin

The authors studied almost two dozen major design-thinking projects within large private- and public-sector organizations in five countries and found that effective leadership is critical to their success. They focused not on how individual design teams did their work but on how the senior executives who commissioned the work interacted with and enabled it. To employees accustomed to being told to be rational and objective, design-thinking methods can seem uncomfortably emotive. Being asked not to quickly converge on an answer can be difficult for people accustomed to valuing a clear direction, cost savings, and finishing sooner rather than later. Iterative prototyping and testing call on employees to repeatedly experience something they’ve historically tried to avoid: failure. Consequently, those who are unfamiliar with design thinking need guidance and support from leaders to navigate the landscape and productively channel their reactions to the approach. The authors have identified practices that executives can use to stay on top of such innovation projects and lead them to success.

How to help project teams overcome the inevitable inefficiencies, uncertainties, and emotional flare-ups

Idea in Brief

The challenge.

Design-thinking methods—such as empathizing with users and conducting experiments knowing many will fail—often seem subjective and personal to employees accustomed to being told to be rational and objective.

The Fallout

Employees can be shocked and dismayed by findings, feel like they are spinning their wheels, or find it difficult to shed preconceptions about the product or service they’ve been providing. Their anxieties may derail the project.

Leaders—without being heavy-handed—need to help teams make the space and time for new ideas to emerge and maintain an overall sense of direction and purpose.

Anne Lind, the head of the national agency in Denmark that evaluates the insurance claims of injured workers and decides on their compensation, had a crisis on her hands. Oddly, it emerged from a project that had seemed to be on a path to success. The project employed design thinking in an effort to improve the services delivered by her organization. The members of her project team immersed themselves in the experiences of clients, establishing rapport and empathizing with them in a bid to see the world through their eyes. The team interviewed and unobtrusively video-recorded clients as they described their situations and their experiences with the agency’s case management. The approach led to a surprising revelation: The agency’s processes were designed largely to serve its own wants and needs (to be efficient and to make claims assessment easy for the staff) rather than those of clients, who typically had gone through a traumatic event and were trying to return to a productive normal life.

- Christian Bason (@christianbason) was for eight years head of MindLab , a cross-governmental innovation unit in Denmark that involves citizens and businesses in developing new solutions for the public sector. Since November 2014 he has been chief executive of the Danish Design Centre .

- Robert D. Austin is a professor of information systems and the faculty director of the Learning Innovation Initiative at Ivey Business School. He is also a coauthor of The Adventures of an IT Leader (Harvard Business Review Press, 2016).

Partner Center

Advertisement

Mapping the Relationship Between Critical Thinking and Design Thinking

- Published: 02 February 2021

- Volume 13 , pages 406–429, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Jonathan D. Ericson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9076-0596 1

2526 Accesses

12 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Critical thinking has been a longstanding goal of education, while design thinking has gradually emerged as a popular method for supporting entrepreneurship, innovation, and problem solving in modern business. While some scholars have posited that design thinking may support critical thinking, empirical research examining the relationship between these two modes of thinking is lacking because their shared conceptual structure has not been articulated in detail and because they have remained siloed in practice. This essay maps eleven essential components of critical thinking to a variety of methods drawn from three popular design thinking frameworks. The mapping reveals that these seemingly unrelated modes of thinking share common features but also differ in important respects. A detailed comparison of the two modes of thinking suggests that design thinking methods have the potential to support and augment traditional critical thinking practices, and that design thinking frameworks could be modified to more explicitly incorporate critical thinking. The article concludes with a discussion of implications for the knowledge economy, and a research agenda for researchers, educators, and practitioners.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

When Does a Researcher Choose a Quantitative, Qualitative, or Mixed Research Approach?

Designing conceptual articles: four approaches, the theory contribution of case study research designs.

Aranda, M. L., Lie, R., & Guzey, S. (2019). Productive thinking in middle school science students’ design conversations in a design-based engineering challenge. International Journal of Technology and Design Education , (January). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-019-09498-5 .

Association for Computing Machinery. (2018). ACM Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct . Retrieved from https://www.acm.org/code-of-ethics .

Bailin, S. (1987). Critical and creative thinking. Informal Logic, 9 (1), 23–30.

Article Google Scholar

Bailin, S. (1988). Achieving extraordinary ends: An essay on creativity . Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Book Google Scholar

Banfield, R., Lombardo, C. T., & Wax, T. (2015). Design sprint: A practical guidebook for building great digital products . Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media Inc.

Google Scholar

Benson, J., & Dresdow, S. (2014). Design thinking: A fresh approach for transformative assessment practice. Journal of Management Education, 38 (3), 436–461. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562913507571 .

Bloom, B.S. (Ed.), Engelhart, M.D., Furst, E.J., Hill, W.H., & Krathwohl, D.R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay.

Wilner, S., & Micheli, P. (2015). Reconciling the tension between consistency and relevance: design thinking as a mechanism for brand ambidexterity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43 (5), 589–609.

Bonwell, C., & Eison, J. (1991). Active Learning: Creating excitement in the classroom (ASHEERIC Higher Education Report No. 1) . Washington, DC: George Washington University.

Brown, A. (2015). Developing career adaptability and innovative capabilities through learning and working in Norway and the United Kingdom. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 6 (2), 402–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-014-0215-6 .

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., Duguid, P., & Seely, J. (2007). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18 (1), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X018001032 .

Brown, T. (2021). Design thinking. Accessed 4 January 2021. http://www.ideou.com/pages/design-thinking

Callaway, M. R., & Esser, J. K. (1984). Groupthink: Effects of cohesiveness and problemsolving on group decision making. Social Behavior and Personality, 12, 157–164.

Carayannis, E. G., & Rakhmatullin, R. (2014). The quadruple/quintuple innovation helixes and smart specialisation strategies for sustainable and inclusive growth in Europe and beyond. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 5 (2), 212–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-014-0185-8 .

Churchman, C. W. (1967). Guest editorial: Wicked problems. Management Science, 14 (4), B141–B214.

Colzato, L. S., Szapora, A., Lippelt, D., & Hommel, B. (2017). Prior meditation practice modulates performance and strategy use in convergent- and divergent-thinking problems. Mindfulness, 8 (1), 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0352-9 .

Cropley, A. (2006). In praise of convergent thinking. Creativity Research Journal, 18 (3), 391–404. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326934crj1803_13 .

Cross, N, Dorst, K. & Roozenburg, N. (Ed.). (1992). Research in design thinking . Delft: Delft University Press.

Cross, N. (1993). A history of design methodology. In M. J. de Vries, N. Cross, & D. Grant (Eds.), Design methodology and relationships with science (pp. 15–27). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-8220-9_2 .

Crossan, M. M. (1998). Improvisation in action. Organization Science, 9 (5), 593–599. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.9.5.593 .

Davies, M. (2015). A model of critical thinking in higher education. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12835-1_2 .

Davis, C. M. (1990). What is empathy, and can empathy be taught. Physical Therapy, 70 (11), 707–711. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2011.3225 .

Dewey, J. (1910). How we think . Boston, MA: D.C. Health.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process . Lexington, MA: D.C. Health.

Dorst, K. (2011). The core of “design thinking” and its application. Design Studies, 32 (6), 521–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2011.07.006 .

Dym, C., Agogino, A., Erics, O., Frey, D., & Leifer, L. (2005). Engineering design thinking, teaching, and learning. Journal of Engineering Education, 94 (1), 103–120.

Ennis, R. H. (1962). A concept of critical thinking. Harvard Educational Review, 32 (1), 81–111.

Ennis, R. H. (1987a). A taxonomy of critical thinking dispositions and abilities. In Teaching Thinking Skills: Theory and practice . New York, NY: W. H. Freeman.

Ennis, R. H. (1987b). Critical thinking and the curriculum. Slomianko: In M. Heiman & J.(Eds.), Thinking skills instruction: Concepts and techniques. Building Students’ Thinking Skills Series. (pp. 40–48). National Education Association. https://doi.org/10.1177/019263658807250830 .

Ennis, R. H. (1991). Critical thinking: a streamlined conception. Teaching Philosophy, 14 (1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.5840/teachphil19911412 .

Eyler, J., & Giles, D. (1999). Where’s the learning in service-learning . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Facione, P. A. (1990). Critical thinking : A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction executive summary “ The Delphi Report. American Philosophical Association Delphi Research Report . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2009.07.002 .

Fisher, A., & Scriven, M. (1997). Critical thinking: Its definition and assessment . Norwich: Centre for Research in Critical Thinking, University of East Anglia.

Gibbons, S. (2018). Empathy Mapping: The first step in design thinking. Retrieved from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/empathy-mapping/ .

Glaser, E. M. (1941). An experiment in the development of critical thinking . New York: Columbia University Teacher’s College.

Gokhale, A. A. (1995). Collaborative learning enhances critical thinking. Journal of Technology Education , 7 (1), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.21061/jte.v7i1.a.2 .

Halonen, J. S. (1995). Demystifying critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22 (1), 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328023top2201_23 .

Halpern, D. F. (1998). Teaching critical thinking for transfer across domains. American Psychologist, 53 (4), 449–455. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.53.4.449 .

Haupt, G. (2015). Learning from experts: fostering extended thinking in the early phases of the design process. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 25 (4), 483–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-014-9295-7 .

Harley, A. (2018). UX Expert Reviews. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/ux-expert-reviews/

Haupt, G. (2018). Hierarchical thinking: a cognitive tool for guiding coherent decision making in design problem solving. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 28 (1), 207–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-016-9381-0 .

Hitchcock, D. (2018). Critical thinking. In E. Zalta (Ed.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2018). Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/critical-thinking/ .