Confirmation Bias In Psychology: Definition & Examples

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

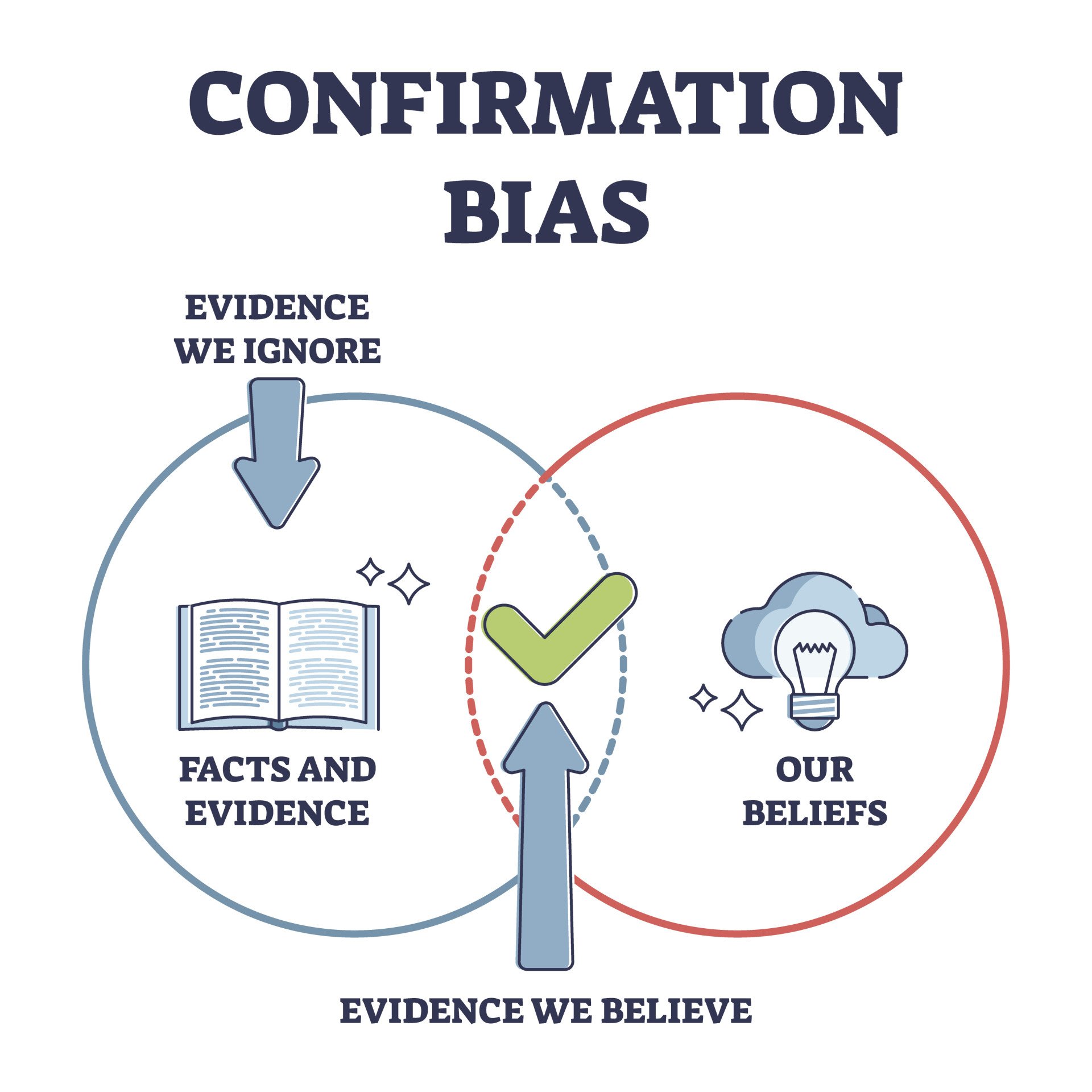

Confirmation Bias is the tendency to look for information that supports, rather than rejects, one’s preconceptions, typically by interpreting evidence to confirm existing beliefs while rejecting or ignoring any conflicting data (American Psychological Association).

One of the early demonstrations of confirmation bias appeared in an experiment by Peter Watson (1960) in which the subjects were to find the experimenter’s rule for sequencing numbers.

Its results showed that the subjects chose responses that supported their hypotheses while rejecting contradictory evidence, and even though their hypotheses were incorrect, they became confident in them quickly (Gray, 2010, p. 356).

Though such evidence of confirmation bias has appeared in psychological literature throughout history, the term ‘confirmation bias’ was first used in a 1977 paper detailing an experimental study on the topic (Mynatt, Doherty, & Tweney, 1977).

Biased Search for Information

This type of confirmation bias explains people’s search for evidence in a one-sided way to support their hypotheses or theories.

Experiments have shown that people provide tests/questions designed to yield “yes” if their favored hypothesis is true and ignore alternative hypotheses that are likely to give the same result.

This is also known as the congruence heuristic (Baron, 2000, p.162-64). Though the preference for affirmative questions itself may not be biased, there are experiments that have shown that congruence bias does exist.

For Example:

If you were to search “Are cats better than dogs?” in Google, all you would get are sites listing the reasons why cats are better.

However, if you were to search “Are dogs better than cats?” google will only provide you with sites that believe dogs are better than cats.

This shows that phrasing questions in a one-sided way (i.e., affirmative manner) will assist you in obtaining evidence consistent with your hypothesis.

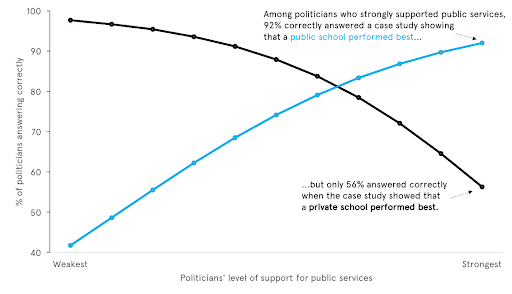

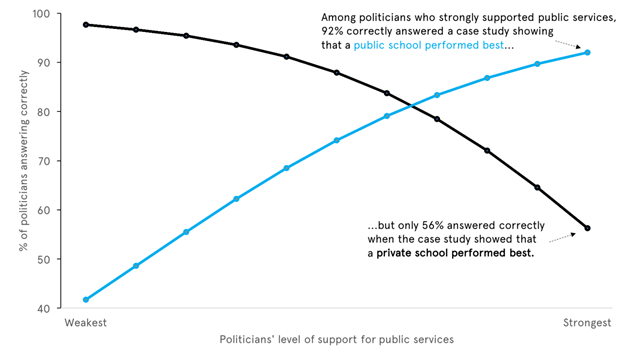

Biased Interpretation

This type of bias explains that people interpret evidence concerning their existing beliefs by evaluating confirming evidence differently than evidence that challenges their preconceptions.

Various experiments have shown that people tend not to change their beliefs on complex issues even after being provided with research because of the way they interpret the evidence.

Additionally, people accept “confirming” evidence more easily and critically evaluate the “disconfirming” evidence (this is known as disconfirmation bias) (Taber & Lodge, 2006).

When provided with the same evidence, people’s interpretations could still be biased.

For example:

Biased interpretation is shown in an experiment conducted by Stanford University on the topic of capital punishment. It included participants who were in support of and others who were against capital punishment.

All subjects were provided with the same two studies.

After reading the detailed descriptions of the studies, participants still held their initial beliefs and supported their reasoning by providing “confirming” evidence from the studies and rejecting any contradictory evidence or considering it inferior to the “confirming” evidence (Lord, Ross, & Lepper, 1979).

Biased Memory

To confirm their current beliefs, people may remember/recall information selectively. Psychological theories vary in defining memory bias.

Some theories state that information confirming prior beliefs is stored in the memory while contradictory evidence is not (i.e., Schema theory). Some others claim that striking information is remembered best (i.e., humor effect).

Memory confirmation bias also serves a role in stereotype maintenance. Experiments have shown that the mental association between expectancy-confirming information and the group label strongly affects recall and recognition memory.

Though a certain stereotype about a social group might not be true for an individual, people tend to remember the stereotype-consistent information better than any disconfirming evidence (Fyock & Stangor, 1994).

In one experimental study, participants were asked to read a woman’s profile (detailing her extroverted and introverted skills) and assess her for either a job of a librarian or real-estate salesperson.

Those assessing her as a salesperson better recalled extroverted traits, while the other group recalled more examples of introversion (Snyder & Cantor, 1979).

These experiments, along with others, have offered an insight into selective memory and provided evidence for biased memory, proving that one searches for and better remembers confirming evidence.

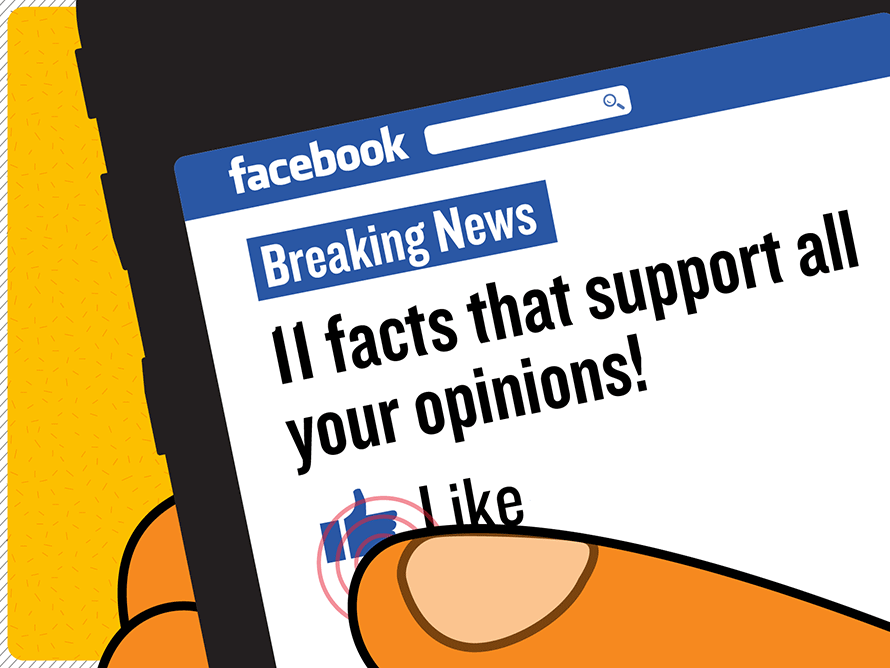

Social Media

Information we are presented on social media is not only reflective of what the users want to see but also of the designers’ beliefs and values. Today, people are exposed to an overwhelming number of news sources, each varying in their credibility.

To form conclusions, people tend to read the news that aligns with their perspectives. For instance, new channels provide information (even the same news) differently from each other on complex issues (i.e., racism, political parties, etc.), with some using sensational headlines/pictures and one-sided information.

Due to the biased coverage of topics, people only utilize certain channels/sites to obtain their information to make biased conclusions.

Religious Faith

People also tend to search for and interpret evidence with respect to their religious beliefs (if any).

For instance, on the topics of abortion and transgender rights, people whose religions are against such things will interpret this information differently than others and will look for evidence to validate what they believe.

Similarly, those who religiously reject the theory of evolution will either gather information disproving evolution or hold no official stance on the topic.

Also, irreligious people might perceive events that are considered “miracles” and “test of faiths” by religious people to be a reinforcement of their lack of faith in a religion.

when Does The Confirmation Bias Occur?

There are several explanations why humans possess confirmation bias, including this tendency being an efficient way to process information, protect self-esteem, and minimize cognitive dissonance.

Information Processing

Confirmation bias serves as an efficient way to process information because of the limitless information humans are exposed to.

To form an unbiased decision, one would have to critically evaluate every piece of information present, which is unfeasible. Therefore, people only tend to look for information desired to form their conclusions (Casad, 2019).

Protect Self-esteem

People are susceptible to confirmation bias to protect their self-esteem (to know that their beliefs are accurate).

To make themselves feel confident, they tend to look for information that supports their existing beliefs (Casad, 2019).

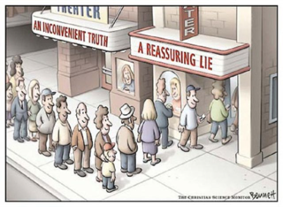

Minimize Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance also explains why confirmation bias is adaptive.

Cognitive dissonance is a mental conflict that occurs when a person holds two contradictory beliefs and causes psychological stress/unease in a person.

To minimize this dissonance, people adapt to confirmation bias by avoiding information that is contradictory to their views and seeking evidence confirming their beliefs.

Challenge avoidance and reinforcement seeking to affect people’s thoughts/reactions differently since exposure to disconfirming information results in negative emotions, something that is nonexistent when seeking reinforcing evidence (“The Confirmation Bias: Why People See What They Want to See”).

Implications

Confirmation bias consistently shapes the way we look for and interpret information that influences our decisions in this society, ranging from homes to global platforms. This bias prevents people from gathering information objectively.

During the election campaign, people tend to look for information confirming their perspectives on different candidates while ignoring any information contradictory to their views.

This subjective manner of obtaining information can lead to overconfidence in a candidate, and misinterpretation/overlooking of important information, thus influencing their voting decision and, eventually country’s leadership (Cherry, 2020).

Recruitment and Selection

Confirmation bias also affects employment diversity because preconceived ideas about different social groups can introduce discrimination (though it might be unconscious) and impact the recruitment process (Agarwal, 2018).

Existing beliefs of a certain group being more competent than the other is the reason why particular races and gender are represented the most in companies today. This bias can hamper the company’s attempt at diversifying its employees.

Mitigating Confirmation Bias

Change in intrapersonal thought:.

To avoid being susceptible to confirmation bias, start questioning your research methods, and sources used to obtain their information.

Expanding the types of sources used in searching for information could provide different aspects of a particular topic and offer levels of credibility.

- Read entire articles rather than forming conclusions based on the headlines and pictures. – Search for credible evidence presented in the article.

- Analyze if the statements being asserted are backed up by trustworthy evidence (tracking the source of evidence could prove its credibility). – Encourage yourself and others to gather information in a conscious manner.

Alternative hypothesis:

Confirmation bias occurs when people tend to look for information that confirms their beliefs/hypotheses, but this bias can be reduced by taking into alternative hypotheses and their consequences.

Considering the possibility of beliefs/hypotheses other than one’s own could help you gather information in a more dynamic manner (rather than a one-sided way).

Related Cognitive Biases

There are many cognitive biases that characterize as subtypes of confirmation bias. Following are two of the subtypes:

Backfire Effect

The backfire effect occurs when people’s preexisting beliefs strengthen when challenged by contradictory evidence (Silverman, 2011).

- Therefore, disproving a misconception can actually strengthen a person’s belief in that misconception.

One piece of disconfirming evidence does not change people’s views, but a constant flow of credible refutations could correct misinformation/misconceptions.

This effect is considered a subtype of confirmation bias because it explains people’s reactions to new information based on their preexisting hypotheses.

A study by Brendan Nyhan and Jason Reifler (two researchers on political misinformation) explored the effects of different types of statements on people’s beliefs.

While examining two statements, “I am not a Muslim, Obama says.” and “I am a Christian, Obama says,” they concluded that the latter statement is more persuasive and resulted in people’s change of beliefs, thus affirming statements are more effective at correcting incorrect views (Silverman, 2011).

Halo Effect

The halo effect occurs when people use impressions from a single trait to form conclusions about other unrelated attributes. It is heavily influenced by the first impression.

Research on this effect was pioneered by American psychologist Edward Thorndike who, in 1920, described ways officers rated their soldiers on different traits based on first impressions (Neugaard, 2019).

Experiments have shown that when positive attributes are presented first, a person is judged more favorably than when negative traits are shown first. This is a subtype of confirmation bias because it allows us to structure our thinking about other information using only initial evidence.

Learning Check

When does the confirmation bias occur.

- When an individual only researches information that is consistent with personal beliefs.

- When an individual only makes a decision after all perspectives have been evaluated.

- When an individual becomes more confident in one’s judgments after researching alternative perspectives.

- When an individual believes that the odds of an event occurring increase if the event hasn’t occurred recently.

The correct answer is A. Confirmation bias occurs when an individual only researches information consistent with personal beliefs. This bias leads people to favor information that confirms their preconceptions or hypotheses, regardless of whether the information is true.

Take-home Messages

- Confirmation bias is the tendency of people to favor information that confirms their existing beliefs or hypotheses.

- Confirmation bias happens when a person gives more weight to evidence that confirms their beliefs and undervalues evidence that could disprove it.

- People display this bias when they gather or recall information selectively or when they interpret it in a biased way.

- The effect is stronger for emotionally charged issues and for deeply entrenched beliefs.

Agarwal, P., Dr. (2018, October 19). Here Is How Bias Can Affect Recruitment In Your Organisation. https://www.forbes.com/sites/pragyaagarwaleurope/2018/10/19/how-can-bias-during-interviewsaffect-recruitment-in-your-organisation

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org/confirmation-bias

Baron, J. (2000). Thinking and Deciding (Third ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Casad, B. (2019, October 09). Confirmation bias . https://www.britannica.com/science/confirmation-bias

Cherry, K. (2020, February 19). Why Do We Favor Information That Confirms Our Existing Beliefs? https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-a-confirmation-bias-2795024

Fyock, J., & Stangor, C. (1994). The role of memory biases in stereotype maintenance. The British journal of social psychology, 33 (3), 331–343.

Gray, P. O. (2010). Psychology . New York: Worth Publishers.

Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37 (11), 2098–2109.

Mynatt, C. R., Doherty, M. E., & Tweney, R. D. (1977). Confirmation bias in a simulated research environment: An experimental study of scientific inference. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 29 (1), 85-95.

Neugaard, B. (2019, October 09). Halo effect. https://www.britannica.com/science/halo-effect

Silverman, C. (2011, June 17). The Backfire Effect . https://archives.cjr.org/behind_the_news/the_backfire_effect.php

Snyder, M., & Cantor, N. (1979). Testing hypotheses about other people: The use of historical knowledge. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 15 (4), 330–342.

Further Information

- What Is Confirmation Bias and When Do People Actually Have It?

- Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises

- The importance of making assumptions: why confirmation is not necessarily a bias

- Decision Making Is Caused By Information Processing And Emotion: A Synthesis Of Two Approaches To Explain The Phenomenon Of Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias occurs when individuals selectively collect, interpret, or remember information that confirms their existing beliefs or ideas, while ignoring or discounting evidence that contradicts these beliefs.

This bias can happen unconsciously and can influence decision-making and reasoning in various contexts, such as research, politics, or everyday decision-making.

What is confirmation bias in psychology?

Confirmation bias in psychology is the tendency to favor information that confirms existing beliefs or values. People exhibiting this bias are likely to seek out, interpret, remember, and give more weight to evidence that supports their views, while ignoring, dismissing, or undervaluing the relevance of evidence that contradicts them.

This can lead to faulty decision-making because one-sided information doesn’t provide a full picture.

Related Articles

Cognitive Psychology

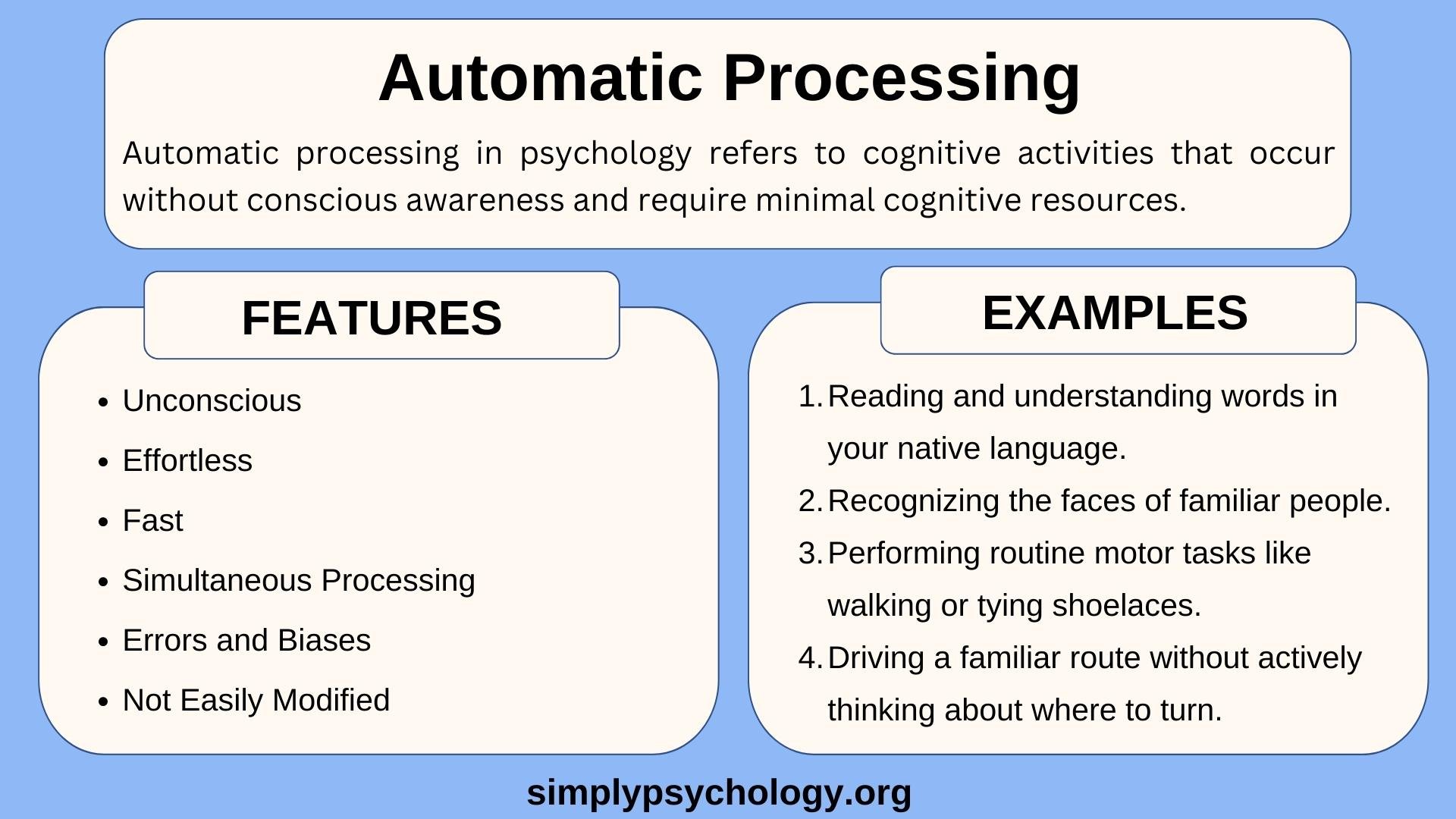

Automatic Processing in Psychology: Definition & Examples

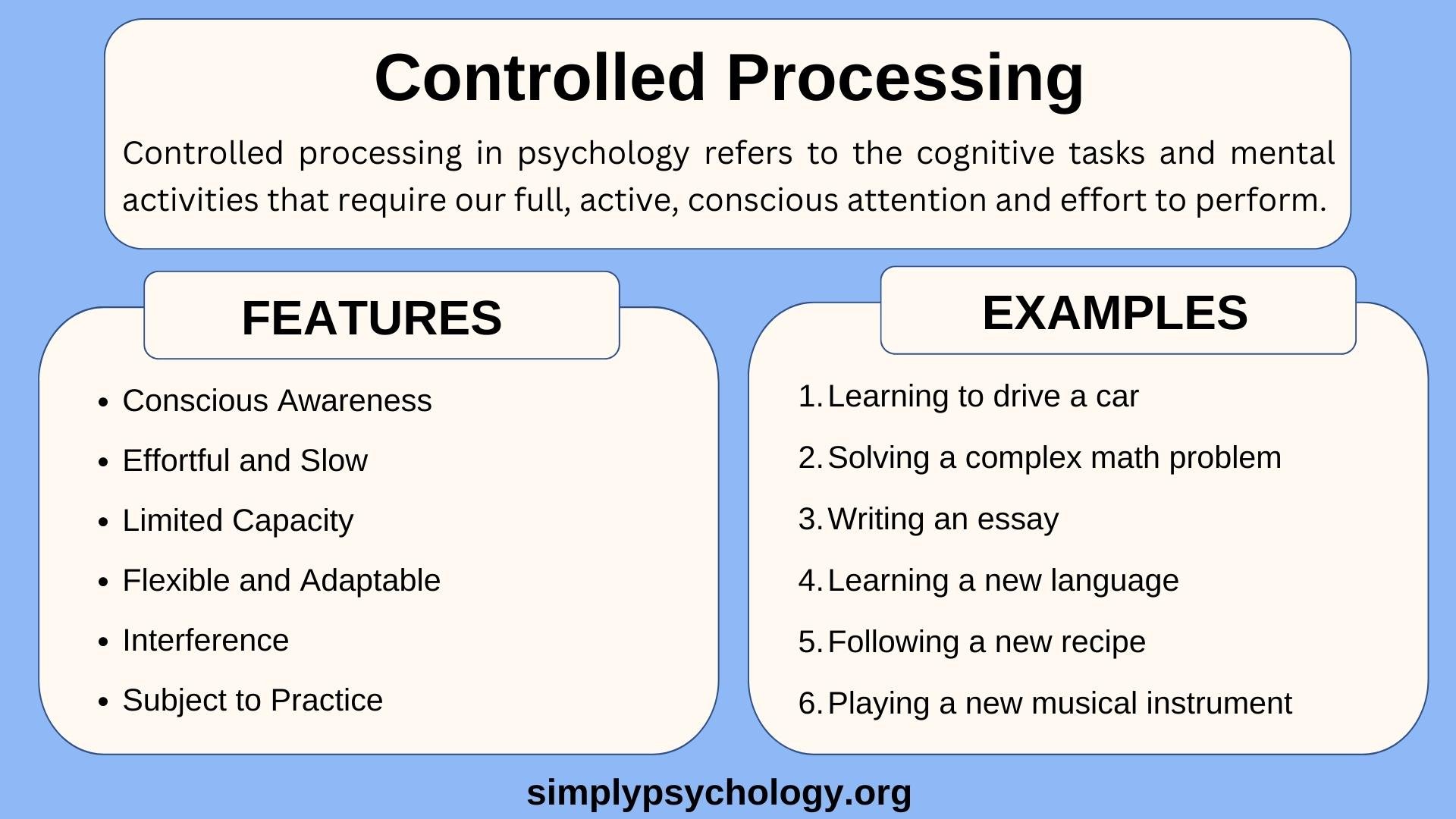

Controlled Processing in Psychology: Definition & Examples

How Ego Depletion Can Drain Your Willpower

What is the Default Mode Network?

Theories of Selective Attention in Psychology

Availability Heuristic and Decision Making

Confirmation Bias: Seeing What We Want to Believe

Confirmation bias is a widely recognized phenomenon and refers to our tendency to seek out evidence in line with our current beliefs and stick to ideas even when the data contradicts them (Lidén, 2023).

Evolutionary and cognitive psychologists agree that we naturally tend to be selective and look for information we already know (Buss, 2016).

This article explores this tendency, how it happens, why it matters, and what we can do to get better at recognizing it and reducing its impact.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive CBT Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will provide you with detailed insight into positive Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and give you the tools to apply it in your therapy or coaching.

This Article Contains

Understanding confirmation bias, fascinating confirmation bias examples, 10 reasons we fall for it, 10 steps to recognizing and reducing confirmation bias, how confirmation bias impacts research, can confirmation bias be good, resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message.

We can understand the confirmation bias definition as the human tendency “to seek out, to interpret, to favor, and to selectively recall information that confirms beliefs they already hold, while avoiding or ignoring information that disconfirms these beliefs” (Gabriel & O’Connor, 2024, p. 1).

While it has been known and accepted since at least the 17th century that humans are inclined to form and hold on to ideas and beliefs — often tenaciously — even when faced with contradictory evidence, the term “confirmation bias” only became popular in the 1960s with the work of cognitive psychologist Peter Cathcart Wason (Lidén, 2023).

Wason’s (1960) famous 2–4–6 experiment was devised to investigate the nature of hypothesis testing.

Participants were given the numbers 2, 4, and 6 and told the numbers adhered to a rule.

They were then asked to arrive at a hypothesis explaining the sequence and try a new three-number series to test their rule (Wason, 1960; Lidén, 2023).

For example, if a participant thought the second number was twice that of the first and the third number was three times greater, they might suggest the numbers 10, 20, and 30.

However, if another participant thought it was a simple series increasing by two each time, they might suggest 13, 15, and 17 (Wason, 1960; Lidén, 2023).

The actual rule is more straightforward; the numbers are in ascending order. That’s all.

As we typically offer tests that confirm our initial beliefs, both example hypotheses appear to work, even if they are not the answer (Wason, 1960; Lidén, 2023).

The experiment demonstrates our confirmation bias; we seek information confirming our existing beliefs or hypotheses rather than challenging or disproving them (Lidén, 2023).

In the decades since, and with developments in cognitive science, we have come to understand that people don’t typically have everything they need, “and even if they did, they would not be able to use all the information due to constraints in the environment, attention, or memory” (Lidén, 2023, p. 8).

Instead, we rely on heuristics. Such “rules of thumb” are easy to apply and fairly accurate, yet they can potentially result in systematic and serious biases and errors in judgment (Lidén, 2023; Eysenck & Keane, 2015).

Confirmation bias in context

Confirmation bias is one of several cognitive biases ’(Lidén, 2023).

They are important because researchers have recognized that “vulnerability to clinical anxiety and depression depends in part on various cognitive biases” and that mental health treatments such as CBT should support the goals of reducing them (Eysenck & Keane, 2015, p. 668).

Cognitive biases include (Eysenck & Keane, 2015):

- Attentional bias Attending to threat-related stimuli more than neutral stimuli

- Interpretive bias Interpreting ambiguous stimuli, situations, and events as threatening

- Explicit memory bias The likelihood of retrieving mostly unpleasant thoughts rather than positive ones

- Implicit memory bias The tendency to perform better for negative or threatening information on memory tests

Individuals possessing all four biases focus too much on environmental threats, interpret most incidents as concerning, and identify themselves as having experienced mostly unpleasant past events (Eysenck & Keane, 2015).

Similarly, confirmation bias means that individuals give too much weight to evidence that confirms their preconceptions or hypotheses, even incorrect and unhelpful ones. It can lead to poor decision-making because it limits their ability to consider alternative viewpoints or evidence that contradicts their beliefs (Lidén, 2023).

Unsurprisingly, such a negative outlook or bias will lead to unhealthy outcomes, including anxiety and depression (Eysenck & Keane, 2015).

Check out Tali Sharot’s video for a deeper dive.

Confirmation bias is commonplace and typically has a low impact, yet there are times when it is significant and newsworthy (Eysenck & Keane, 2015; Lidén, 2023).

Limits of information

In 2005, terrorists detonated four bombs in London (three on the London Underground and one on a bus), killing 52 and injuring 700 civilians. In the chaotic weeks that followed, a further attempt failed to detonate a suicide bomb, and the individual got away (Lidén, 2023).

Unsurprisingly, a mass hunt was launched to capture the escaped bomber, and many suspects came under surveillance. Yet, the security services made several significant mistakes.

On July 22, 2005, a man living in the same house as two suspects and bearing a resemblance to one of them was shot dead on an Underground train by officers.

“The context with the previous bombings, the available intelligence, and the pre-operation briefings, created expectations that the surveillance team would spot a suicide bomber leaving the doorway” (Lidén, 2023, p. 37).

The wrong man died because the officers involved failed to see the limits of the information available to them at the time.

Witness identification

In 1976, factory worker John Demjanjuk from Cleveland, Ohio, was identified as a Nazi war criminal known as Ivan the Terrible, perpetrator of many killings within prison camps in the Second World War (Lidén, 2023).

Due to the individual’s denial and limited evidence, the case rested on proof of identity via a photo line-up. However, it became known that “Ivan the Terrible” had a round face and was bald.

As the defendant was the only individual who matched the description, he was chosen by all the witnesses (Lidén, 2023).

Whether or not the witnesses were genuinely able to identify the factory worker as the criminal became irrelevant. The case centered around the unfairness of the line-up and the confirmation bias that resulted from the information they had been given (Lidén, 2023).

Years later, in 2012, following continuing challenges to his identity, John Demjanjuk died pending an appeal for his conviction in a German court. His identity remained unclear as the confirmation bias remained (“Ivan the Terrible,” 2024).

Download 3 Free Positive CBT Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to find new pathways to reduce suffering and more effectively cope with life stressors.

Download 3 Free Positive CBT Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Confirmation bias can significantly impact our own and others’ lives (Lidén, 2023; Kappes et al., 2020).

For that reason, it is helpful to understand why it happens and the psychological factors involved. Research confirms that people (Lidén, 2023; Kappes et al., 2020; Eysenck & Keane, 2015):

- Don’t like to let go of their initial hypothesis

- Prefer to use as much information as is initially available, often resulting in a too specific hypothesis

- Show confirmation bias more on their hypothesis than others

- Are more likely to adopt a confirmation bias when under high cognitive load

- With a lower degree of intelligence are more likely to engage in confirmation bias (most likely due to being less able to manage higher cognitive loads and see the overall picture)

- With cognitive impairments are more impacted by confirmation bias

- Are often unable to actively consider and understand all relevant information to challenge the existing hypothesis or make a new one

- Are influenced by their emotions and motivations and potentially “blinded” to the facts

- Are biased by existing thoughts and beliefs (sometimes cultural), even if incorrect

- Are influenced by the beliefs and arguments of those around them

- Recognize that confirmation bias exists and understand its impact on decision-making and how you interpret information.

- Actively seek out and consider different viewpoints, opinions, and sources of information that challenge your existing beliefs and hypotheses.

- Develop critical thinking skills that evaluate evidence and arguments objectively without favoring preconceived notions or desired outcomes.

- Be aware of your biases and open to questioning your beliefs and assumptions.

- Explore alternative explanations or hypotheses that may contradict your initial beliefs or interpretations.

- Welcome feedback and criticism from others, even if they challenge your ideas; recognize it as an opportunity to learn and grow.

- Apply systematic and rigorous methods to gather and analyze data, ensuring your conclusions are evidence-based rather than a result of personal biases.

- Engage in collaborative discussions and debates with individuals with different perspectives to help see other viewpoints and challenge your biases.

- Continuously seek new information and update your knowledge base to avoid becoming entrenched and support more-informed decision-making.

- Practice analytical thinking, questioning assumptions, evaluating evidence objectively, and considering alternate explanations.

As far back as 1968, Karl Popper recognized that falsifiability (being able to prove that something can be incorrect or false) is crucial to all scientific inquiry, impacting researchers’ behavior and experimental outcomes.

As scientists, Popper argued, we should focus on looking for examples of why a theory does not work instead of seeking confirmation of its correctness. More recently, researchers have also considered that when findings suggest a theory is false, it may be due to issues with the experimental design or data accuracy (Eysenck & Keane, 2015).

Yet, confirmation bias has been an issue for a long time in scientific discovery and remains a challenge.

When researchers looked back at the work of Alexander Graham Bell in developing the telephone, they found that, due to confirmation bias, he ignored promising new approaches in favor of his tried-and-tested ones. It ultimately led to Thomas Edison being the first to develop the forerunner of today’s telephone (Eysenck & Keane, 2015).

More recently, a study showed that 88% of professional scientists working on issues in molecular biology responded to unexpected and inconsistent findings by blaming their experimental methods; they ignored the suggestion that they may need to modify, or even replace, their theories (Eysenck & Keane, 2015).

However, when those same scientists changed their approach yet obtained similarly inconsistent results, 61% revisited their theoretical assumptions (Eysenck & Keane, 2015).

Failure to report null research findings is also a problem. It is known as the “file drawer problem” because data remains unseen in the bottom drawer as the researcher does not attempt to get findings published or because journals show no interest in them (Lidén, 2023).

Researchers have recognized several potential benefits that arise from our natural inclination to seek out confirmation that we are right, including (Peters, 2022; Gabriel & O’Connor, 2024; Bergerot et al., 2023):

- Assisting in the personal development of individuals by reinforcing their positive self-conceptions and traits

- Helping individuals shape social structures by persuading others to adopt their viewpoints

- Supporting increased confidence by reinforcing individuals’ beliefs and ignoring contradictory evidence

- Contributing to social conformity and stability by reinforcing shared beliefs and values within a group, potentially boosting cooperation and coordination

- Encouraging decision-making by removing uncertainty and doubt

- Increasing the knowledge-producing capacity of a group by supporting a deeper exploration of individual members’ perspectives

It’s vital to note that the possible benefits also have their limitations. They potentially favor the individual at the cost of others’ needs while potentially distorting and hindering the formation of well-founded beliefs (Peters, 2022).

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

We have many resources for coaches and therapists to help individuals and groups understand and manage their biases.

Why not download our free 3 Positive CBT Exercises Pack and try out the powerful tools contained within? Some examples include the following:

- Re-Framing Critical Self-Talk Self-criticism typically involves judgment and self-blame regarding our shortcomings (real or imagined), such as our inability to accomplish personal goals and meet others’ expectations. In this exercise, we use self-talk to help us reduce self-criticism and cultivate a kinder, compassionate relationship with ourselves.

- Solution-Focused Guided Imagery Solution-focused therapy assumes we have the resources required to resolve our issues. Here, we learn how to connect with our strengths and overcome the challenges we face.

Other free resources include:

- The What-If Bias We often get caught up in our negative biases, thinking about potentially dire outcomes rather than adopting rational beliefs. This exercise helps us regain a more realistic and balanced perspective.

- Becoming Aware of Assumptions We all bring biases into our daily lives, particularly conversations. In this helpful exercise , we picture how things might be in five years to put them into context.

More extensive versions of the following tools are available with a subscription to the Positive Psychology Toolkit© , but they are described briefly below.

- Increasing Awareness of Cognitive Distortions

Cognitive distortions refer to our biased thinking about ourselves and our environment. This tool helps reduce the effect of the distortions by dismantling them.

- Step one – Begin by exploring cognitive distortions, such as all-or-nothing thinking, jumping to conclusions, and catastrophizing .

- Step two – Next, identify the cognitive distortions relevant to your situation.

- Step three – Reflect on your thinking patterns, how they could harm you, and how you interact with others.

- Finding Silver Linings

We tend to dwell on the things that go wrong in our lives. We may even begin to think our days are filled with mishaps and disappointments.

Rather than solely focusing on things that have gone wrong, it can help to look on the bright side. Try the following:

- Step one – Create a list of things that make you feel life is worthwhile, enjoyable, and meaningful.

- Step two – Think of a time when things didn’t go how you wanted them to.

- Step three – Reflect on what this difficulty cost you.

- Step four – Finally, consider what you may have gained from the experience. Write down three positives.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others through CBT, check out this collection of 17 validated positive CBT tools for practitioners. Use them to help others overcome unhelpful thoughts and feelings and develop more positive behaviors.

We can’t always trust what we hear or see because our beliefs and expectations influence so much of how we interact with the world.

Confirmation bias refers to our natural inclination to seek out and focus on what confirms our beliefs, often ignoring anything that contradicts them.

While we have known of its effect for over 200 years, it still receives considerable research focus because of its impact on us individually and as a society, often causing us to make poor decisions and leading to damaging outcomes.

Confirmation bias has several sources and triggers, including our unwillingness to relinquish our initial beliefs (even when incorrect), preference for personal hypotheses, cognitive load, and cognitive impairments.

However, most of us can reduce confirmation bias with practice and training. We can become more aware of such inclinations and seek out challenges or alternate explanations for our beliefs.

It matters because confirmation bias can influence how we work, the research we base decisions on, and how our clients manage their relationships with others and their environments.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. For more information, don’t forget to download our three Positive CBT Exercises for free .

- Bergerot, C., Barfuss, W., & Romanczuk, P. (2023). Moderate confirmation bias enhances collective decision-making . biorXiv. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.11.21.568073v1.full

- Buss, D. M. (2016). Evolutionary psychology: The new science of the mind . Routledge.

- Eysenck, M. W., & Keane, M. T. (2015). Cognitive psychology: A student’s handbook . Psychology Press.

- Gabriel, N., & O’Connor, C. (2024). Can confirmation bias improve group learning? PhilSci Archive. https://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/20528/

- Ivan the Terrible (Treblinka guard). (2024). In Wikipedia . https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivan_the_Terrible_(Treblinka_guard)

- Kappes, A., Harvey, A. H., Lohrenz, T., Montague, P. R., & Sharot, T. (2020). Confirmation bias in the utilization of others’ opinion strength. Nature Neuroscience , 23 (1), 130–137.

- Lidén, M. (2023). Confirmation bias in criminal cases . Oxford University Press.

- Peters, U. (2022). What is the function of confirmation bias? Erkenntnis , 87 , 1351–1376.

- Popper, K. R. (1968). The logic of scientific discovery . Hutchinson.

- Rist, T. (2023). Confirmation bias studies: Towards a scientific theory in the humanities. SN Social Sciences , 3 (8).

- Wason, P. C. (1960). On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology , 12 (3), 129–140.

Share this article:

Article feedback

Let us know your thoughts cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Fundamental Attribution Error: Shifting the Blame Game

We all try to make sense of the behaviors we observe in ourselves and others. However, sometimes this process can be marred by cognitive biases [...]

Halo Effect: Why We Judge a Book by Its Cover

Even though we may consider ourselves logical and rational, it appears we are easily biased by a single incident or individual characteristic (Nicolau, Mellinas, & [...]

Sunk Cost Fallacy: Why We Can’t Let Go

If you’ve continued with a decision or an investment of time, money, or resources long after you should have stopped, you’ve succumbed to the ‘sunk [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (22)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (19)

- Positive Parenting (16)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (18)

- Relationships (43)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Positive CBT Exercises (PDF)

7.3 Problem-Solving

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe problem solving strategies

- Define algorithm and heuristic

- Explain some common roadblocks to effective problem solving

People face problems every day—usually, multiple problems throughout the day. Sometimes these problems are straightforward: To double a recipe for pizza dough, for example, all that is required is that each ingredient in the recipe be doubled. Sometimes, however, the problems we encounter are more complex. For example, say you have a work deadline, and you must mail a printed copy of a report to your supervisor by the end of the business day. The report is time-sensitive and must be sent overnight. You finished the report last night, but your printer will not work today. What should you do? First, you need to identify the problem and then apply a strategy for solving the problem.

The study of human and animal problem solving processes has provided much insight toward the understanding of our conscious experience and led to advancements in computer science and artificial intelligence. Essentially much of cognitive science today represents studies of how we consciously and unconsciously make decisions and solve problems. For instance, when encountered with a large amount of information, how do we go about making decisions about the most efficient way of sorting and analyzing all the information in order to find what you are looking for as in visual search paradigms in cognitive psychology. Or in a situation where a piece of machinery is not working properly, how do we go about organizing how to address the issue and understand what the cause of the problem might be. How do we sort the procedures that will be needed and focus attention on what is important in order to solve problems efficiently. Within this section we will discuss some of these issues and examine processes related to human, animal and computer problem solving.

PROBLEM-SOLVING STRATEGIES

When people are presented with a problem—whether it is a complex mathematical problem or a broken printer, how do you solve it? Before finding a solution to the problem, the problem must first be clearly identified. After that, one of many problem solving strategies can be applied, hopefully resulting in a solution.

Problems themselves can be classified into two different categories known as ill-defined and well-defined problems (Schacter, 2009). Ill-defined problems represent issues that do not have clear goals, solution paths, or expected solutions whereas well-defined problems have specific goals, clearly defined solutions, and clear expected solutions. Problem solving often incorporates pragmatics (logical reasoning) and semantics (interpretation of meanings behind the problem), and also in many cases require abstract thinking and creativity in order to find novel solutions. Within psychology, problem solving refers to a motivational drive for reading a definite “goal” from a present situation or condition that is either not moving toward that goal, is distant from it, or requires more complex logical analysis for finding a missing description of conditions or steps toward that goal. Processes relating to problem solving include problem finding also known as problem analysis, problem shaping where the organization of the problem occurs, generating alternative strategies, implementation of attempted solutions, and verification of the selected solution. Various methods of studying problem solving exist within the field of psychology including introspection, behavior analysis and behaviorism, simulation, computer modeling, and experimentation.

A problem-solving strategy is a plan of action used to find a solution. Different strategies have different action plans associated with them (table below). For example, a well-known strategy is trial and error. The old adage, “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again” describes trial and error. In terms of your broken printer, you could try checking the ink levels, and if that doesn’t work, you could check to make sure the paper tray isn’t jammed. Or maybe the printer isn’t actually connected to your laptop. When using trial and error, you would continue to try different solutions until you solved your problem. Although trial and error is not typically one of the most time-efficient strategies, it is a commonly used one.

Another type of strategy is an algorithm. An algorithm is a problem-solving formula that provides you with step-by-step instructions used to achieve a desired outcome (Kahneman, 2011). You can think of an algorithm as a recipe with highly detailed instructions that produce the same result every time they are performed. Algorithms are used frequently in our everyday lives, especially in computer science. When you run a search on the Internet, search engines like Google use algorithms to decide which entries will appear first in your list of results. Facebook also uses algorithms to decide which posts to display on your newsfeed. Can you identify other situations in which algorithms are used?

A heuristic is another type of problem solving strategy. While an algorithm must be followed exactly to produce a correct result, a heuristic is a general problem-solving framework (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). You can think of these as mental shortcuts that are used to solve problems. A “rule of thumb” is an example of a heuristic. Such a rule saves the person time and energy when making a decision, but despite its time-saving characteristics, it is not always the best method for making a rational decision. Different types of heuristics are used in different types of situations, but the impulse to use a heuristic occurs when one of five conditions is met (Pratkanis, 1989):

- When one is faced with too much information

- When the time to make a decision is limited

- When the decision to be made is unimportant

- When there is access to very little information to use in making the decision

- When an appropriate heuristic happens to come to mind in the same moment

Working backwards is a useful heuristic in which you begin solving the problem by focusing on the end result. Consider this example: You live in Washington, D.C. and have been invited to a wedding at 4 PM on Saturday in Philadelphia. Knowing that Interstate 95 tends to back up any day of the week, you need to plan your route and time your departure accordingly. If you want to be at the wedding service by 3:30 PM, and it takes 2.5 hours to get to Philadelphia without traffic, what time should you leave your house? You use the working backwards heuristic to plan the events of your day on a regular basis, probably without even thinking about it.

Another useful heuristic is the practice of accomplishing a large goal or task by breaking it into a series of smaller steps. Students often use this common method to complete a large research project or long essay for school. For example, students typically brainstorm, develop a thesis or main topic, research the chosen topic, organize their information into an outline, write a rough draft, revise and edit the rough draft, develop a final draft, organize the references list, and proofread their work before turning in the project. The large task becomes less overwhelming when it is broken down into a series of small steps.

Further problem solving strategies have been identified (listed below) that incorporate flexible and creative thinking in order to reach solutions efficiently.

Additional Problem Solving Strategies :

- Abstraction – refers to solving the problem within a model of the situation before applying it to reality.

- Analogy – is using a solution that solves a similar problem.

- Brainstorming – refers to collecting an analyzing a large amount of solutions, especially within a group of people, to combine the solutions and developing them until an optimal solution is reached.

- Divide and conquer – breaking down large complex problems into smaller more manageable problems.

- Hypothesis testing – method used in experimentation where an assumption about what would happen in response to manipulating an independent variable is made, and analysis of the affects of the manipulation are made and compared to the original hypothesis.

- Lateral thinking – approaching problems indirectly and creatively by viewing the problem in a new and unusual light.

- Means-ends analysis – choosing and analyzing an action at a series of smaller steps to move closer to the goal.

- Method of focal objects – putting seemingly non-matching characteristics of different procedures together to make something new that will get you closer to the goal.

- Morphological analysis – analyzing the outputs of and interactions of many pieces that together make up a whole system.

- Proof – trying to prove that a problem cannot be solved. Where the proof fails becomes the starting point or solving the problem.

- Reduction – adapting the problem to be as similar problems where a solution exists.

- Research – using existing knowledge or solutions to similar problems to solve the problem.

- Root cause analysis – trying to identify the cause of the problem.

The strategies listed above outline a short summary of methods we use in working toward solutions and also demonstrate how the mind works when being faced with barriers preventing goals to be reached.

One example of means-end analysis can be found by using the Tower of Hanoi paradigm . This paradigm can be modeled as a word problems as demonstrated by the Missionary-Cannibal Problem :

Missionary-Cannibal Problem

Three missionaries and three cannibals are on one side of a river and need to cross to the other side. The only means of crossing is a boat, and the boat can only hold two people at a time. Your goal is to devise a set of moves that will transport all six of the people across the river, being in mind the following constraint: The number of cannibals can never exceed the number of missionaries in any location. Remember that someone will have to also row that boat back across each time.

Hint : At one point in your solution, you will have to send more people back to the original side than you just sent to the destination.

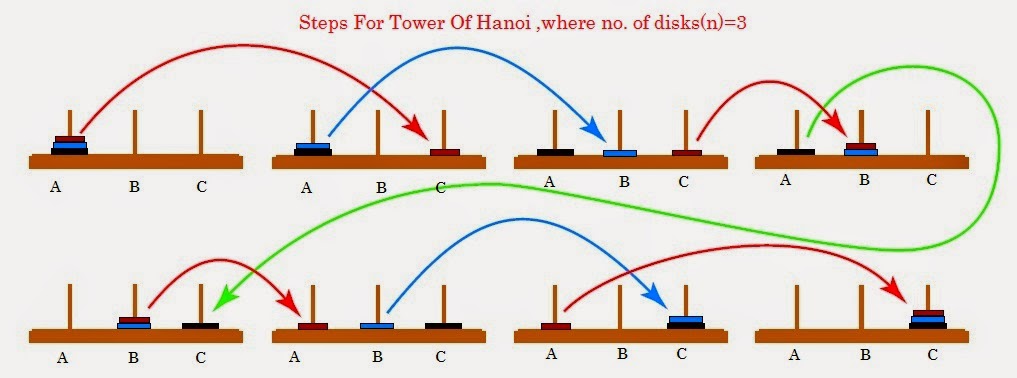

The actual Tower of Hanoi problem consists of three rods sitting vertically on a base with a number of disks of different sizes that can slide onto any rod. The puzzle starts with the disks in a neat stack in ascending order of size on one rod, the smallest at the top making a conical shape. The objective of the puzzle is to move the entire stack to another rod obeying the following rules:

- 1. Only one disk can be moved at a time.

- 2. Each move consists of taking the upper disk from one of the stacks and placing it on top of another stack or on an empty rod.

- 3. No disc may be placed on top of a smaller disk.

Figure 7.02. Steps for solving the Tower of Hanoi in the minimum number of moves when there are 3 disks.

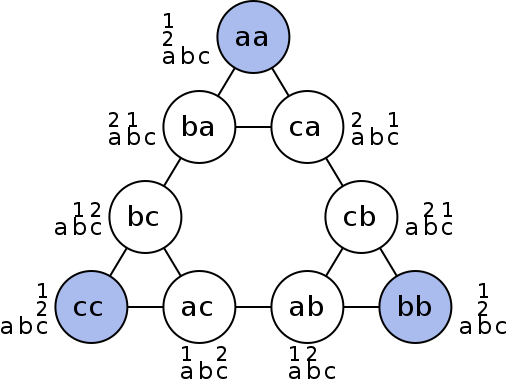

Figure 7.03. Graphical representation of nodes (circles) and moves (lines) of Tower of Hanoi.

The Tower of Hanoi is a frequently used psychological technique to study problem solving and procedure analysis. A variation of the Tower of Hanoi known as the Tower of London has been developed which has been an important tool in the neuropsychological diagnosis of executive function disorders and their treatment.

GESTALT PSYCHOLOGY AND PROBLEM SOLVING

As you may recall from the sensation and perception chapter, Gestalt psychology describes whole patterns, forms and configurations of perception and cognition such as closure, good continuation, and figure-ground. In addition to patterns of perception, Wolfgang Kohler, a German Gestalt psychologist traveled to the Spanish island of Tenerife in order to study animals behavior and problem solving in the anthropoid ape.

As an interesting side note to Kohler’s studies of chimp problem solving, Dr. Ronald Ley, professor of psychology at State University of New York provides evidence in his book A Whisper of Espionage (1990) suggesting that while collecting data for what would later be his book The Mentality of Apes (1925) on Tenerife in the Canary Islands between 1914 and 1920, Kohler was additionally an active spy for the German government alerting Germany to ships that were sailing around the Canary Islands. Ley suggests his investigations in England, Germany and elsewhere in Europe confirm that Kohler had served in the German military by building, maintaining and operating a concealed radio that contributed to Germany’s war effort acting as a strategic outpost in the Canary Islands that could monitor naval military activity approaching the north African coast.

While trapped on the island over the course of World War 1, Kohler applied Gestalt principles to animal perception in order to understand how they solve problems. He recognized that the apes on the islands also perceive relations between stimuli and the environment in Gestalt patterns and understand these patterns as wholes as opposed to pieces that make up a whole. Kohler based his theories of animal intelligence on the ability to understand relations between stimuli, and spent much of his time while trapped on the island investigation what he described as insight , the sudden perception of useful or proper relations. In order to study insight in animals, Kohler would present problems to chimpanzee’s by hanging some banana’s or some kind of food so it was suspended higher than the apes could reach. Within the room, Kohler would arrange a variety of boxes, sticks or other tools the chimpanzees could use by combining in patterns or organizing in a way that would allow them to obtain the food (Kohler & Winter, 1925).

While viewing the chimpanzee’s, Kohler noticed one chimp that was more efficient at solving problems than some of the others. The chimp, named Sultan, was able to use long poles to reach through bars and organize objects in specific patterns to obtain food or other desirables that were originally out of reach. In order to study insight within these chimps, Kohler would remove objects from the room to systematically make the food more difficult to obtain. As the story goes, after removing many of the objects Sultan was used to using to obtain the food, he sat down ad sulked for a while, and then suddenly got up going over to two poles lying on the ground. Without hesitation Sultan put one pole inside the end of the other creating a longer pole that he could use to obtain the food demonstrating an ideal example of what Kohler described as insight. In another situation, Sultan discovered how to stand on a box to reach a banana that was suspended from the rafters illustrating Sultan’s perception of relations and the importance of insight in problem solving.

Grande (another chimp in the group studied by Kohler) builds a three-box structure to reach the bananas, while Sultan watches from the ground. Insight , sometimes referred to as an “Ah-ha” experience, was the term Kohler used for the sudden perception of useful relations among objects during problem solving (Kohler, 1927; Radvansky & Ashcraft, 2013).

Solving puzzles.

Problem-solving abilities can improve with practice. Many people challenge themselves every day with puzzles and other mental exercises to sharpen their problem-solving skills. Sudoku puzzles appear daily in most newspapers. Typically, a sudoku puzzle is a 9×9 grid. The simple sudoku below (see figure) is a 4×4 grid. To solve the puzzle, fill in the empty boxes with a single digit: 1, 2, 3, or 4. Here are the rules: The numbers must total 10 in each bolded box, each row, and each column; however, each digit can only appear once in a bolded box, row, and column. Time yourself as you solve this puzzle and compare your time with a classmate.

How long did it take you to solve this sudoku puzzle? (You can see the answer at the end of this section.)

Here is another popular type of puzzle (figure below) that challenges your spatial reasoning skills. Connect all nine dots with four connecting straight lines without lifting your pencil from the paper:

Did you figure it out? (The answer is at the end of this section.) Once you understand how to crack this puzzle, you won’t forget.

Take a look at the “Puzzling Scales” logic puzzle below (figure below). Sam Loyd, a well-known puzzle master, created and refined countless puzzles throughout his lifetime (Cyclopedia of Puzzles, n.d.).

What steps did you take to solve this puzzle? You can read the solution at the end of this section.

Pitfalls to problem solving.

Not all problems are successfully solved, however. What challenges stop us from successfully solving a problem? Albert Einstein once said, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.” Imagine a person in a room that has four doorways. One doorway that has always been open in the past is now locked. The person, accustomed to exiting the room by that particular doorway, keeps trying to get out through the same doorway even though the other three doorways are open. The person is stuck—but she just needs to go to another doorway, instead of trying to get out through the locked doorway. A mental set is where you persist in approaching a problem in a way that has worked in the past but is clearly not working now.

Functional fixedness is a type of mental set where you cannot perceive an object being used for something other than what it was designed for. During the Apollo 13 mission to the moon, NASA engineers at Mission Control had to overcome functional fixedness to save the lives of the astronauts aboard the spacecraft. An explosion in a module of the spacecraft damaged multiple systems. The astronauts were in danger of being poisoned by rising levels of carbon dioxide because of problems with the carbon dioxide filters. The engineers found a way for the astronauts to use spare plastic bags, tape, and air hoses to create a makeshift air filter, which saved the lives of the astronauts.

Researchers have investigated whether functional fixedness is affected by culture. In one experiment, individuals from the Shuar group in Ecuador were asked to use an object for a purpose other than that for which the object was originally intended. For example, the participants were told a story about a bear and a rabbit that were separated by a river and asked to select among various objects, including a spoon, a cup, erasers, and so on, to help the animals. The spoon was the only object long enough to span the imaginary river, but if the spoon was presented in a way that reflected its normal usage, it took participants longer to choose the spoon to solve the problem. (German & Barrett, 2005). The researchers wanted to know if exposure to highly specialized tools, as occurs with individuals in industrialized nations, affects their ability to transcend functional fixedness. It was determined that functional fixedness is experienced in both industrialized and nonindustrialized cultures (German & Barrett, 2005).

In order to make good decisions, we use our knowledge and our reasoning. Often, this knowledge and reasoning is sound and solid. Sometimes, however, we are swayed by biases or by others manipulating a situation. For example, let’s say you and three friends wanted to rent a house and had a combined target budget of $1,600. The realtor shows you only very run-down houses for $1,600 and then shows you a very nice house for $2,000. Might you ask each person to pay more in rent to get the $2,000 home? Why would the realtor show you the run-down houses and the nice house? The realtor may be challenging your anchoring bias. An anchoring bias occurs when you focus on one piece of information when making a decision or solving a problem. In this case, you’re so focused on the amount of money you are willing to spend that you may not recognize what kinds of houses are available at that price point.

The confirmation bias is the tendency to focus on information that confirms your existing beliefs. For example, if you think that your professor is not very nice, you notice all of the instances of rude behavior exhibited by the professor while ignoring the countless pleasant interactions he is involved in on a daily basis. Hindsight bias leads you to believe that the event you just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t. In other words, you knew all along that things would turn out the way they did. Representative bias describes a faulty way of thinking, in which you unintentionally stereotype someone or something; for example, you may assume that your professors spend their free time reading books and engaging in intellectual conversation, because the idea of them spending their time playing volleyball or visiting an amusement park does not fit in with your stereotypes of professors.

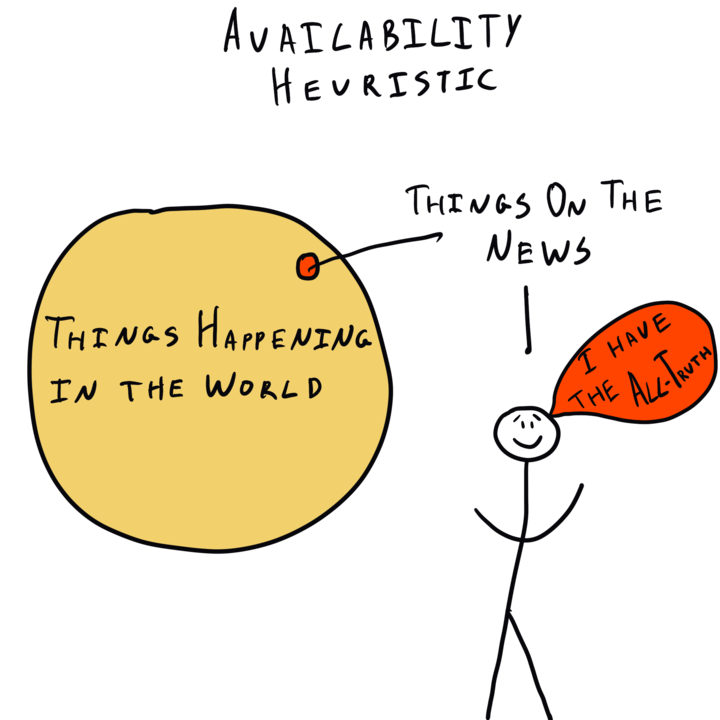

Finally, the availability heuristic is a heuristic in which you make a decision based on an example, information, or recent experience that is that readily available to you, even though it may not be the best example to inform your decision . Biases tend to “preserve that which is already established—to maintain our preexisting knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and hypotheses” (Aronson, 1995; Kahneman, 2011). These biases are summarized in the table below.

Were you able to determine how many marbles are needed to balance the scales in the figure below? You need nine. Were you able to solve the problems in the figures above? Here are the answers.

Many different strategies exist for solving problems. Typical strategies include trial and error, applying algorithms, and using heuristics. To solve a large, complicated problem, it often helps to break the problem into smaller steps that can be accomplished individually, leading to an overall solution. Roadblocks to problem solving include a mental set, functional fixedness, and various biases that can cloud decision making skills.

References:

Openstax Psychology text by Kathryn Dumper, William Jenkins, Arlene Lacombe, Marilyn Lovett and Marion Perlmutter licensed under CC BY v4.0. https://openstax.org/details/books/psychology

Review Questions:

1. A specific formula for solving a problem is called ________.

a. an algorithm

b. a heuristic

c. a mental set

d. trial and error

2. Solving the Tower of Hanoi problem tends to utilize a ________ strategy of problem solving.

a. divide and conquer

b. means-end analysis

d. experiment

3. A mental shortcut in the form of a general problem-solving framework is called ________.

4. Which type of bias involves becoming fixated on a single trait of a problem?

a. anchoring bias

b. confirmation bias

c. representative bias

d. availability bias

5. Which type of bias involves relying on a false stereotype to make a decision?

6. Wolfgang Kohler analyzed behavior of chimpanzees by applying Gestalt principles to describe ________.

a. social adjustment

b. student load payment options

c. emotional learning

d. insight learning

7. ________ is a type of mental set where you cannot perceive an object being used for something other than what it was designed for.

a. functional fixedness

c. working memory

Critical Thinking Questions:

1. What is functional fixedness and how can overcoming it help you solve problems?

2. How does an algorithm save you time and energy when solving a problem?

Personal Application Question:

1. Which type of bias do you recognize in your own decision making processes? How has this bias affected how you’ve made decisions in the past and how can you use your awareness of it to improve your decisions making skills in the future?

anchoring bias

availability heuristic

confirmation bias

functional fixedness

hindsight bias

problem-solving strategy

representative bias

trial and error

working backwards

Answers to Exercises

algorithm: problem-solving strategy characterized by a specific set of instructions

anchoring bias: faulty heuristic in which you fixate on a single aspect of a problem to find a solution

availability heuristic: faulty heuristic in which you make a decision based on information readily available to you

confirmation bias: faulty heuristic in which you focus on information that confirms your beliefs

functional fixedness: inability to see an object as useful for any other use other than the one for which it was intended

heuristic: mental shortcut that saves time when solving a problem

hindsight bias: belief that the event just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t

mental set: continually using an old solution to a problem without results

problem-solving strategy: method for solving problems

representative bias: faulty heuristic in which you stereotype someone or something without a valid basis for your judgment

trial and error: problem-solving strategy in which multiple solutions are attempted until the correct one is found

working backwards: heuristic in which you begin to solve a problem by focusing on the end result

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

What Is the Function of Confirmation Bias?

- Original Research

- Open access

- Published: 20 April 2020

- Volume 87 , pages 1351–1376, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Uwe Peters 1 , 2

75k Accesses

43 Citations

183 Altmetric

19 Mentions

Explore all metrics

Confirmation bias is one of the most widely discussed epistemically problematic cognitions, challenging reliable belief formation and the correction of inaccurate views. Given its problematic nature, it remains unclear why the bias evolved and is still with us today. To offer an explanation, several philosophers and scientists have argued that the bias is in fact adaptive. I critically discuss three recent proposals of this kind before developing a novel alternative, what I call the ‘reality-matching account’. According to the account, confirmation bias evolved because it helps us influence people and social structures so that they come to match our beliefs about them. This can result in significant developmental and epistemic benefits for us and other people, ensuring that over time we don’t become epistemically disconnected from social reality but can navigate it more easily. While that might not be the only evolved function of confirmation bias, it is an important one that has so far been neglected in the theorizing on the bias.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Relationship Between Social Media Use and Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories and Misinformation

Conformity in groups: the effects of others’ views on expressed attitudes and attitude change.

An evolutionary perspective on Kohlberg’s theory of moral development

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In recent years, confirmation bias (or ‘myside bias’), Footnote 1 that is, people’s tendency to search for information that supports their beliefs and ignore or distort data contradicting them (Nickerson 1998 ; Myers and DeWall 2015 : 357), has frequently been discussed in the media, the sciences, and philosophy. The bias has, for example, been mentioned in debates on the spread of “fake news” (Stibel 2018 ), on the “replication crisis” in the sciences (Ball 2017 ; Lilienfeld 2017 ), the impact of cognitive diversity in philosophy (Peters 2019a ; Peters et al. forthcoming; Draper and Nichols 2013 ; De Cruz and De Smedt 2016 ), the role of values in inquiry (Steel 2018 ; Peters 2018 ), and the evolution of human reasoning (Norman 2016 ; Mercier and Sperber 2017 ; Sterelny 2018 ; Dutilh Novaes 2018 ).

Confirmation bias is typically viewed as an epistemically pernicious tendency. For instance, Mercier and Sperber ( 2017 : 215) maintain that the bias impedes the formation of well-founded beliefs, reduces people’s ability to correct their mistaken views, and makes them, when they reason on their own, “become overconfident” (Mercier 2016 : 110). In the same vein, Steel ( 2018 ) holds that the bias involves an “epistemic distortion [that] consists of unjustifiably favoring supporting evidence for [one’s] belief, which can result in the belief becoming unreasonably confident or extreme” (897). Similarly, Peters ( 2018 ) writes that confirmation bias “leads to partial, and therewith for the individual less reliable, information processing” (15).

The bias is not only taken to be epistemically problematic, but also thought to be a “ubiquitous” (Nickerson 1998 : 208), “built-in feature of the mind” (Haidt 2012 : 105), found in both everyday and abstract reasoning tasks (Evans 1996 ), independently of subjects’ intelligence, cognitive ability, or motivation to avoid it (Stanovich et al. 2013 ; Lord et al. 1984 ). Given its seemingly dysfunctional character, the apparent pervasiveness of confirmation bias raises a puzzle: If the bias is indeed epistemically problematic, why is it still with us today? By definition, dysfunctional traits should be more prone to extinction than functional ones (Nickerson 1998 ). Might confirmation bias be or have been adaptive ?

Some philosophers are optimistic, arguing that the bias has in fact significant advantages for the individual, groups, or both (Mercier and Sperber 2017 ; Norman 2016 ; Smart 2018 ; Peters 2018 ). Others are pessimistic. For instance, Dutilh Novaes ( 2018 ) maintains that confirmation bias makes subjects less able to anticipate other people’s viewpoints, and so, “given the importance of being able to appreciate one’s interlocutor’s perspective for social interaction”, is “best not seen as an adaptation” (520).

In the following, I discuss three recent proposals of the adaptationist kind, mention reservations about them, and develop a novel account of the evolution of confirmation bias that challenges a key assumption underlying current research on the bias, namely that the bias thwarts reliable belief formation and truth tracking. The account holds that while searching for information supporting one’s pre-existing beliefs and ignoring contradictory data is disadvantageous when that what one takes to be reality is and stays different from what one believes it to be, it is beneficial when, as the result of one’s processing information in that way, that reality is changed so that it matches one’s beliefs. I call this process reality matching and contend that it frequently occurs when the beliefs at issue are about people and social structures (i.e., relationships between individuals, groups, and socio-political institutions). In these situations, confirmation bias is highly effective for us to be confident about our beliefs even when there is insufficient evidence or subjective motivation available to us to support them. This helps us influence and ‘mould’ people and social structures so that they fit our beliefs, Footnote 2 which is an adaptive property of confirmation bias. It can result in significant developmental and epistemic benefits for us and other people, ensuring that over time we don’t become epistemically disconnected from social reality but can navigate it more easily.

I shall not argue that the adaptive function of confirmation bias that this reality-matching account highlights is the only evolved function of the bias. Rather, I propose that it is one important function that has so far been neglected in the theorizing on the bias.

In Sects. 1 and 2 , I distinguish confirmation bias from related cognitions before briefly introducing some recent empirical evidence supporting the existence of the bias. In Sect. 3 , I motivate the search for an evolutionary explanation of confirmation bias and critically discuss three recent proposals. In Sects. 4 and 5 , I then develop and support the reality-matching account as an alternative.

1 Confirmation Bias and Friends

The term ‘confirmation bias’ has been used to refer to various distinct ways in which beliefs and expectations can influence the selection, retention, and evaluation of evidence (Klayman 1995 ; Nickerson 1998 ). Hahn and Harris ( 2014 ) offer a list of them including four types of cognitions: (1) hypothesis-determined information seeking and interpretation, (2) failures to pursue a falsificationist strategy in contexts of conditional reasoning, (3) a resistance to change a belief or opinion once formed, and (4) overconfidence or an illusion of validity of one’s own view.

Hahn and Harries note that while all of these cognitions have been labeled ‘confirmation bias’, (1)–(4) are also sometimes viewed as components of ‘motivated reasoning’ (or ‘wishful thinking’) (ibid: 45), i.e., information processing that leads people to arrive at the conclusions they favor (Kunda 1990 ). In fact, as Nickerson ( 1998 : 176) notes, confirmation bias comes in two different flavors: “motivated” and “unmotivated” confirmation bias. And the operation of the former can be understood as motivated reasoning itself, because it too involves partial information processing to buttress a view that one wants to be true (ibid). Unmotivated confirmation bias, however, operates when people process data in one-sided, partial ways that support their predetermined views no matter whether they favor them. So confirmation bias is also importantly different from motivated reasoning, as it can take effect in the absence of a preferred view and might lead one to support even beliefs that one wants to be false (e.g., when one believes the catastrophic effects of climate change are unavoidable; Steel 2018 ).

Despite overlapping with motivated reasoning, confirmation bias can thus plausibly be (and typically is) construed as a distinctive cognition. It is thought to be a subject’s largely automatic and unconscious tendency to (i) seek support for her pre-existing, favored or not favored beliefs and (ii) ignore or distort information compromising them (Klayman 1995 : 406; Nickerson 1998 : 175; Myers and DeWall 2015 : 357; Palminteri et al. 2017 : 14). I here endorse this standard, functional concept of confirmation bias.

2 Is Confirmation Bias Real?

Many psychologists hold that the bias is a “pervasive” (Nickerson 1998 : 175; Palminteri et al. 2017 : 14), “ineradicable” feature of human reasoning (Haidt 2012 : 105). Such strong claims are problematic, however. For there is evidence that, for instance, disrupting the fluency in information processing (Hernandez and Preston 2013 ) or priming subjects for distrust (Mayo et al. 2014 ) reduces the bias. Moreover, some researchers have recently re-examined the relevant studies and found that confirmation bias is in fact less common and the evidence of it less robust than often assumed (Mercier 2016 ; Whittlestone 2017 ). These researchers grant, however, the weaker claim that the bias is real and often, in some domains more than in others, operative in human cognition (Mercier 2016 : 100, 108; Whittlestone 2017 : 199, 207). I shall only rely on this modest view here. To motivate it a bit more, consider the following two studies.

Hall et al. ( 2012 ) gave their participants (N = 160) a questionnaire, asking them about their opinion on moral principles such as ‘Even if an action might harm the innocent, it can still be morally permissible to perform it’. After the subjects had indicated their view using a scale ranging from ‘completely disagree’ to ‘completely agree’, the experimenter performed a sleight of hand, inverting the meaning of some of the statements so that the question then read, for instance, ‘If an action might harm the innocent, then it is not morally permissible to perform it’. The answer scales, however, were not altered. So if a subject had agreed with the first claim, she then agreed with the opposite one. Surprisingly, 69% of the study participants failed to detect at least one of the changes. Moreover, they subsequently tended to justify positions they thought they held despite just having chosen the opposite . Presumably, subjects accepted that they favored a particular position, didn’t know the reasons, and so were now looking for support that would justify their position. They displayed a confirmation bias. Footnote 3

Using a similar experimental set-up, Trouche et al. ( 2016 ) found that subjects also tend to exhibit a selective ‘laziness’ in their critical thinking: they are more likely to avoid raising objections to their own positions than to other people’s. Trouche et al. first asked their test participants to produce arguments in response to a set of simple reasoning problems. Directly afterwards, they had them assess other subjects’ arguments concerning the same problems. About half of the participants didn’t notice that by the experimenter’s intervention, in some trials, they were in fact presented with their own arguments again; the arguments appeared to these participants as if they were someone else’s. Furthermore, more than half of the subjects who believed they were assessing someone else’s arguments now rejected those that were in fact their own, and were more likely to do so for invalid than for valid ones. This suggests that subjects are less critical of their own arguments than of other people’s, indicating that confirmation bias is real and perhaps often operative when we are considering our own claims and arguments.

3 Evolutionary Accounts of the Bias

Confirmation bias is typically taken to be epistemically problematic, as it leads to partial and therewith for the individual less reliable information processing and contributes to failures in, for instance, perspective-taking with clear costs for social and other types of cognition (Mercier and Sperber 2017 : 215; Steel 2018 ; Peters 2018 ; Dutilh Novaes 2018 ). Prima facie , the bias thus seems maladaptive.

But then why does it still exist? Granted, even if the bias isn’t an adaptation, we might still be able to explain why it is with us today. We might, for instance, argue that it is a “spandrel”, a by-product of the evolution of another trait that is an adaptation (Gould and Lewontin 1979 ). Or we may abandon the evolutionary approach to the bias altogether and hold that it emerged by chance.

However, evolutionary explanations of psychological traits are often fruitful. They can create new perspectives on these traits that may allow developing means to reduce the traits’ potential negative effects (Roberts et al. 2012 ; Johnson et al. 2013 ). Evolutionary explanations might also stimulate novel, testable predictions that researchers who aren’t evolutionarily minded would overlook (Ketelaar and Ellis 2000 ; De Bruine 2009 ). Moreover, they typically involve integrating diverse data from different disciplines (e.g., psychology, biology, anthropology etc.), and thereby contribute to the development of a more complete understanding of the traits at play and human cognition, in general (Tooby and Cosmides 2015 ). These points equally apply when it comes to considering the origin of confirmation bias. They provide good reasons for searching for an evolutionary account of the bias.

Different proposals can be discerned in the literature. I will discuss three recent ones, what I shall call (1) the argumentative - function account, (2) the group - cognition account, and the (3) intention – alignment account. I won’t offer conclusive arguments against them here. The aim is just to introduce some reservations about these proposals to motivate the exploration of an alternative.

3.1 The Argumentative-Function Account

Mercier and Sperber ( 2011 , 2017 ) hold that human reasoning didn’t evolve for truth tracking but for making us better at convincing other people and evaluating their arguments so as to be convinced only when their points are compelling. In this context, when persuasion is paramount, the tendency to look for material supporting our preconceptions and to discount contradictory data allows us to accumulate argumentative ammunition, which strengthens our argumentative skill, Mercier and Sperber maintain. They suggest that confirmation bias thus evolved to “serve the goal of convincing others” ( 2011 : 63).