McCombs School of Business

- Español ( Spanish )

Videos Concepts Unwrapped View All 36 short illustrated videos explain behavioral ethics concepts and basic ethics principles. Concepts Unwrapped: Sports Edition View All 10 short videos introduce athletes to behavioral ethics concepts. Ethics Defined (Glossary) View All 58 animated videos - 1 to 2 minutes each - define key ethics terms and concepts. Ethics in Focus View All One-of-a-kind videos highlight the ethical aspects of current and historical subjects. Giving Voice To Values View All Eight short videos present the 7 principles of values-driven leadership from Gentile's Giving Voice to Values. In It To Win View All A documentary and six short videos reveal the behavioral ethics biases in super-lobbyist Jack Abramoff's story. Scandals Illustrated View All 30 videos - one minute each - introduce newsworthy scandals with ethical insights and case studies. Video Series

Case Studies UT Star Icon

Case Studies

More than 70 cases pair ethics concepts with real world situations. From journalism, performing arts, and scientific research to sports, law, and business, these case studies explore current and historic ethical dilemmas, their motivating biases, and their consequences. Each case includes discussion questions, related videos, and a bibliography.

A Million Little Pieces

James Frey’s popular memoir stirred controversy and media attention after it was revealed to contain numerous exaggerations and fabrications.

Abramoff: Lobbying Congress

Super-lobbyist Abramoff was caught in a scheme to lobby against his own clients. Was a corrupt individual or a corrupt system – or both – to blame?

Apple Suppliers & Labor Practices

Is tech company Apple, Inc. ethically obligated to oversee the questionable working conditions of other companies further down their supply chain?

Approaching the Presidency: Roosevelt & Taft

Some presidents view their responsibilities in strictly legal terms, others according to duty. Roosevelt and Taft took two extreme approaches.

Appropriating “Hope”

Fairey’s portrait of Barack Obama raised debate over the extent to which an artist can use and modify another’s artistic work, yet still call it one’s own.

Arctic Offshore Drilling

Competing groups frame the debate over oil drilling off Alaska’s coast in varying ways depending on their environmental and economic interests.

Banning Burkas: Freedom or Discrimination?

The French law banning women from wearing burkas in public sparked debate about discrimination and freedom of religion.

Birthing Vaccine Skepticism

Wakefield published an article riddled with inaccuracies and conflicts of interest that created significant vaccine hesitancy regarding the MMR vaccine.

Blurred Lines of Copyright

Marvin Gaye’s Estate won a lawsuit against Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams for the hit song “Blurred Lines,” which had a similar feel to one of his songs.

Bullfighting: Art or Not?

Bullfighting has been a prominent cultural and artistic event for centuries, but in recent decades it has faced increasing criticism for animal rights’ abuse.

Buying Green: Consumer Behavior

Do purchasing green products, such as organic foods and electric cars, give consumers the moral license to indulge in unethical behavior?

Cadavers in Car Safety Research

Engineers at Heidelberg University insist that the use of human cadavers in car safety research is ethical because their research can save lives.

Cardinals’ Computer Hacking

St. Louis Cardinals scouting director Chris Correa hacked into the Houston Astros’ webmail system, leading to legal repercussions and a lifetime ban from MLB.

Cheating: Atlanta’s School Scandal

Teachers and administrators at Parks Middle School adjust struggling students’ test scores in an effort to save their school from closure.

Cheating: Sign-Stealing in MLB

The Houston Astros’ sign-stealing scheme rocked the baseball world, leading to a game-changing MLB investigation and fallout.

Cheating: UNC’s Academic Fraud

UNC’s academic fraud scandal uncovered an 18-year scheme of unchecked coursework and fraudulent classes that enabled student-athletes to play sports.

Cheney v. U.S. District Court

A controversial case focuses on Justice Scalia’s personal friendship with Vice President Cheney and the possible conflict of interest it poses to the case.

Christina Fallin: “Appropriate Culturation?”

After Fallin posted a picture of herself wearing a Plain’s headdress on social media, uproar emerged over cultural appropriation and Fallin’s intentions.

Climate Change & the Paris Deal

While climate change poses many abstract problems, the actions (or inactions) of today’s populations will have tangible effects on future generations.

Cover-Up on Campus

While the Baylor University football team was winning on the field, university officials failed to take action when allegations of sexual assault by student athletes emerged.

Covering Female Athletes

Sports Illustrated stirs controversy when their cover photo of an Olympic skier seems to focus more on her physical appearance than her athletic abilities.

Covering Yourself? Journalists and the Bowl Championship

Can news outlets covering the Bowl Championship Series fairly report sports news if their own polls were used to create the news?

Cyber Harassment

After a student defames a middle school teacher on social media, the teacher confronts the student in class and posts a video of the confrontation online.

Defending Freedom of Tweets?

Running back Rashard Mendenhall receives backlash from fans after criticizing the celebration of the assassination of Osama Bin Laden in a tweet.

Dennis Kozlowski: Living Large

Dennis Kozlowski was an effective leader for Tyco in his first few years as CEO, but eventually faced criminal charges over his use of company assets.

Digital Downloads

File-sharing program Napster sparked debate over the legal and ethical dimensions of downloading unauthorized copies of copyrighted music.

Dr. V’s Magical Putter

Journalist Caleb Hannan outed Dr. V as a trans woman, sparking debate over the ethics of Hannan’s reporting, as well its role in Dr. V’s suicide.

East Germany’s Doping Machine

From 1968 to the late 1980s, East Germany (GDR) doped some 9,000 athletes to gain success in international athletic competitions despite being aware of the unfortunate side effects.

Ebola & American Intervention

Did the dispatch of U.S. military units to Liberia to aid in humanitarian relief during the Ebola epidemic help or hinder the process?

Edward Snowden: Traitor or Hero?

Was Edward Snowden’s release of confidential government documents ethically justifiable?

Ethical Pitfalls in Action

Why do good people do bad things? Behavioral ethics is the science of moral decision-making, which explores why and how people make the ethical (and unethical) decisions that they do.

Ethical Use of Home DNA Testing

The rising popularity of at-home DNA testing kits raises questions about privacy and consumer rights.

Flying the Confederate Flag

A heated debate ensues over whether or not the Confederate flag should be removed from the South Carolina State House grounds.

Freedom of Speech on Campus

In the wake of racially motivated offenses, student protests sparked debate over the roles of free speech, deliberation, and tolerance on campus.

Freedom vs. Duty in Clinical Social Work

What should social workers do when their personal values come in conflict with the clients they are meant to serve?

Full Disclosure: Manipulating Donors

When an intern witnesses a donor making a large gift to a non-profit organization under misleading circumstances, she struggles with what to do.

Gaming the System: The VA Scandal

The Veterans Administration’s incentives were meant to spur more efficient and productive healthcare, but not all administrators complied as intended.

German Police Battalion 101

During the Holocaust, ordinary Germans became willing killers even though they could have opted out from murdering their Jewish neighbors.

Head Injuries & American Football

Many studies have linked traumatic brain injuries and related conditions to American football, creating controversy around the safety of the sport.

Head Injuries & the NFL

American football is a rough and dangerous game and its impact on the players’ brain health has sparked a hotly contested debate.

Healthcare Obligations: Personal vs. Institutional

A medical doctor must make a difficult decision when informing patients of the effectiveness of flu shots while upholding institutional recommendations.

High Stakes Testing

In the wake of the No Child Left Behind Act, parents, teachers, and school administrators take different positions on how to assess student achievement.

In-FUR-mercials: Advertising & Adoption

When the Lied Animal Shelter faces a spike in animal intake, an advertising agency uses its moral imagination to increase pet adoptions.

Krogh & the Watergate Scandal

Egil Krogh was a young lawyer working for the Nixon Administration whose ethics faded from view when asked to play a part in the Watergate break-in.

Limbaugh on Drug Addiction

Radio talk show host Rush Limbaugh argued that drug abuse was a choice, not a disease. He later became addicted to painkillers.

U.S. Olympic swimmer Ryan Lochte’s “over-exaggeration” of an incident at the 2016 Rio Olympics led to very real consequences.

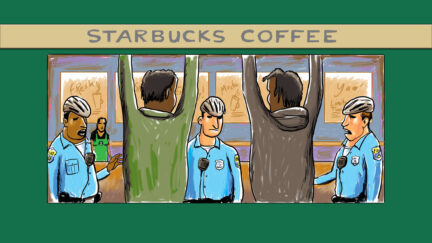

Meet Me at Starbucks

Two black men were arrested after an employee called the police on them, prompting Starbucks to implement “racial-bias” training across all its stores.

Myanmar Amber

Buying amber could potentially fund an ethnic civil war, but refraining allows collectors to acquire important specimens that could be used for research.

Negotiating Bankruptcy

Bankruptcy lawyer Gellene successfully represented a mining company during a major reorganization, but failed to disclose potential conflicts of interest.

Pao & Gender Bias

Ellen Pao stirred debate in the venture capital and tech industries when she filed a lawsuit against her employer on grounds of gender discrimination.

Pardoning Nixon

One month after Richard Nixon resigned from the presidency, Gerald Ford made the controversial decision to issue Nixon a full pardon.

Patient Autonomy & Informed Consent

Nursing staff and family members struggle with informed consent when taking care of a patient who has been deemed legally incompetent.

Prenatal Diagnosis & Parental Choice

Debate has emerged over the ethics of prenatal diagnosis and reproductive freedom in instances where testing has revealed genetic abnormalities.

Reporting on Robin Williams

After Robin Williams took his own life, news media covered the story in great detail, leading many to argue that such reporting violated the family’s privacy.

Responding to Child Migration

An influx of children migrants posed logistical and ethical dilemmas for U.S. authorities while intensifying ongoing debate about immigration.

Retracting Research: The Case of Chandok v. Klessig

A researcher makes the difficult decision to retract a published, peer-reviewed article after the original research results cannot be reproduced.

Sacking Social Media in College Sports

In the wake of questionable social media use by college athletes, the head coach at University of South Carolina bans his players from using Twitter.

Selling Enron

Following the deregulation of electricity markets in California, private energy company Enron profited greatly, but at a dire cost.

Snyder v. Phelps

Freedom of speech was put on trial in a case involving the Westboro Baptist Church and their protesting at the funeral of U.S. Marine Matthew Snyder.

Something Fishy at the Paralympics

Rampant cheating has plagued the Paralympics over the years, compromising the credibility and sportsmanship of Paralympian athletes.

Sports Blogs: The Wild West of Sports Journalism?

Deadspin pays an anonymous source for information related to NFL star Brett Favre, sparking debate over the ethics of “checkbook journalism.”

Stangl & the Holocaust

Franz Stangl was the most effective Nazi administrator in Poland, killing nearly one million Jews at Treblinka, but he claimed he was simply following orders.

Teaching Blackface: A Lesson on Stereotypes

A teacher was put on leave for showing a blackface video during a lesson on racial segregation, sparking discussion over how to teach about stereotypes.

The Astros’ Sign-Stealing Scandal

The Houston Astros rode a wave of success, culminating in a World Series win, but it all came crashing down when their sign-stealing scheme was revealed.

The Central Park Five

Despite the indisputable and overwhelming evidence of the innocence of the Central Park Five, some involved in the case refuse to believe it.

The CIA Leak

Legal and political fallout follows from the leak of classified information that led to the identification of CIA agent Valerie Plame.

The Collapse of Barings Bank

When faced with growing losses, investment banker Nick Leeson took big risks in an attempt to get out from under the losses. He lost.

The Costco Model

How can companies promote positive treatment of employees and benefit from leading with the best practices? Costco offers a model.

The FBI & Apple Security vs. Privacy

How can tech companies and government organizations strike a balance between maintaining national security and protecting user privacy?

The Miss Saigon Controversy

When a white actor was cast for the half-French, half-Vietnamese character in the Broadway production of Miss Saigon , debate ensued.

The Sandusky Scandal

Following the conviction of assistant coach Jerry Sandusky for sexual abuse, debate continues on how much university officials and head coach Joe Paterno knew of the crimes.

The Varsity Blues Scandal

A college admissions prep advisor told wealthy parents that while there were front doors into universities and back doors, he had created a side door that was worth exploring.

Providing radiation therapy to cancer patients, Therac-25 had malfunctions that resulted in 6 deaths. Who is accountable when technology causes harm?

Welfare Reform

The Welfare Reform Act changed how welfare operated, intensifying debate over the government’s role in supporting the poor through direct aid.

Wells Fargo and Moral Emotions

In a settlement with regulators, Wells Fargo Bank admitted that it had created as many as two million accounts for customers without their permission.

Stay Informed

Support our work.

Case Studies

Case study discussion.

Below is a list of the case study articles that have been published in NIB , each with keywords, a set of discussion questions, and further resources. To search page contents with keywords, select "Control-F" from a PC, or "Command-F" from a Mac.

- Accommodating Religious Beliefs in the ICU: A Narrative Account of a Disputed Death

- When Ethics Consultation and Courts Collide: A Case of Compelled Treatment of a Mature Minor

- Advance Directives, Preemptive Suicide, and Emergency Medicine Decision Making

- Healing the Physician’s Story: A Case of Narrative Medicine and End-of-Life Care

- The Efficacy of Ethics Discernment in the Organizational Context: The Case of Post-Offer Nicotine Screening

- Can We Talk About Sex?

- Should We Tell Annie?: Preparing for Death at the Intersection of Parental Authority and Adolescent Autonomy

- A Case of Deceptive Mastectomy

- Do Everything

- Responding to the Refusal of Care in the Emergency Department

- I Don’t Know Why I Called You

- Undocumented and at the End of Life

- Dax’s Case Redux: When Comes the End of the Day?

- Desperately Seeking a Surrogate— For a Patient Lacking Decision-Making Capacity

- What to Say When: Responding to a Suicide Attempt in the Acute Care Setting

- Conversation and the Jehovah’s Witness Dying From Blood Loss

- Caregivers’ Role in Maternal-Fetal Conflict

- The Surgeon as Stakeholder: Making the Case Not to Operate

- The Enduring Case

- Military Health Care Dilemmas and Genetic Discrimination: A Family’s Experience with Whole Exome Sequencing

- Conflicting Values: A Case Study in Patient Choice and Caregiver Perspectives

- Ethical Dilemmas Relating to the Management of a Newborn with Down Syndrome and Severe Congenital Heart Disease in a Resource-Poor Setting

- System Failure: No Surgeon To Be Found

- Ethical Challenges in the Care of the Inpatient with Morbid Obesity

- A Life Below the Threshold? Examining Conflict Between Ethical Principles and Parental Values in Neonatal Treatment Decision Making

- The Clinical Bioethicist’s Role: Should We Aim to Relieve Suffering?

- To Enroll or Not to Enroll?: A Researcher Struggles with the Decision to Involve Study Participants in a Clinical Trial That Could Save Their Lives

- Sometimes Those Hoofbeats Are Zebras: A Narrative Analysis

- A Jehovah’s Witness Adolescent in the Labor and Delivery Unit: Should Patient and Parental Refusals of Blood Transfusions for Adolescents Be Honored?

- Reframing Medical Appropriateness: A Case Study Concerning the Use of Life-Sustaining Technologies for a Patient With Profoundly Diminished Quality of Life

- "We Didn't Consent to This"

- Screen Shots: When Patients and Families Publish Negative Health Care Narratives Online

- A Personal Narrative on Living and Dealing with Psychiatric Symptoms after DBS Surgery

- The Will Reconsidered: Hard Choices in Living Organ Donation

- Malleable Transplant Criteria: At What Cost?

- Responding to Requests for Aid-in-Dying: Rethinking the Role of Conscience

- Getting to the Heart of the Matter: Navigating Narrative Intersections in Ethics Consultation

- Speaking for Our Father

- Forcible Amputation in Delusional Patients: A Narrative Analysis of Decisional Capacity

- A Health Care Systems Approach to Improving Care for Seriously Ill Patients

- An Ethics of Unknowing: Discerning Ethical Patient-Provider Interactions in Clinical Decision-Making

- How Should Physicians Manage Neuro-prognosis with ECPR?

- The Ethics of Choosing a Surrogate Decision Maker When Equal-Priority Surrogates Disagree

- A Gay Epidemiologist and the DC Commission of Public Health AIDS Advisory Committee

- Shared Decision-Making in Palliative Care: A Maternalistic Approach

- Phantom Physicians and Medical Catfishing: A Narrative Ethics Approach to Ghost Surgery

- It Takes Time to Let Go

- An American’s Experience with End-of-Life Care in Japan: Comparing Brain Death, Limiting and Withdrawing Life-Prolonging Interventions, and Healthcare Ethics Consultation Practices in Japan and the United States

- The Sword of King Solomon

- Appreciating the Dynamicity of Values at the End of Life: A Psychological and Ethical Analysis

- Serendipity and Social Justice: How Someone with a Physical Disability Succeeds in Clinical Bioethics

- The Right to Be Childfree

- Undisclosed Placebo Trials in Clinical Practice: Undercover Beneficence or Unwarranted Deception?

- What Do We Owe to Patients Who Leave Against Medical Advice? The Ethics of AMA Discharges?

- "Jehovah's Witnesses and the Normative Function of Indirect Consent"

- "Parental Refusals of Blood Transfusions from COVID-19 Vaccinated Donors for Children Needing Cardiac Surgery"

- "Withdrawing Life Support After Attempted Suicide: A Case Study and Review of Ethical Consideration"

1. Accommodating Religious Beliefs in the ICU: A Narrative Account of a Disputed Death

Martin L. Smith, Anne Lederman Flamm

Abstract: Despite widespread acceptance in the United States of neurological criteria to determine death, clinicians encounter families who object, often on religious grounds, to the categorization of their loved ones as “brain dead.” The concept of “reasonable accommodation” of objections to brain death, promulgated in both state statutes and the bioethics literature, suggests the possibility of compromise between the family’s deeply held beliefs and the legal, professional and moral values otherwise directing clinicians to withdraw medical interventions. Relying on narrative to convey the experience of a family and clinical caregivers embroiled in this complex dilemma, the case analyzed here explores the practical challenges and moral ambiguities presented by the concept of reasonable accommodation. Clarifying the term’s meaning and boundaries, and identifying guidelines for its clinical implementation, could help to reduce uncertainty for both health care professionals and families and, thereby, the incremental moral distress such uncertainty creates.

Keywords: Brain death, clinical ethics, ethics consultation, reasonable accommodation, religious conflict

Link to Case on MUSE

Reflection Questions:

- How might have the nurses’ and physicians’ initial frank commentary about Sarah’s condition affected the family’s interpretation of the clinicians’ opinions later on in the care process?

- In what ways might the new hospital have provided support to Sarah’s family in order to avoid the religion vs. medicine standoff that eventually developed?

- How much patience are physicians obligated to have with family members who extensively question the medical decision-making process? Was the hospital staff correct in labeling Rebekah as “manipulative”?

- Is it ethically appropriate for financial considerations to affect the family’s decision-making? Why or why not? To what extent should the healthcare team discuss the financial impact of decisions with families?

Web Resources:

- New York State Department of Health Guidelines for Determining Brain Death. (2011). Retrieved from: http://www.health.ny.gov/professionals/hospital_administrator/letters/2011/brain_death_guidelines.pdf

- Olick, RS, Braun, EA, and Potash, J. (2009). Accommodating Religious and Moral Objections to Neurological Death. The Journal of Clinical Ethics. Retrieved from: http://www.upstate.edu/bioethics/pdf/faculty/olick_accommodating-religious-and-moral-objections-to-neurological-death.pdf

- Breitowitz, YA. Jewish Medical Ethics: The Brain Death Controversy in Jewish Law. Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved from: https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Judaism/braindead.html

2. When Ethics Consultation and Courts Collide: A Case of Compelled Treatment of a Mature Minor

Jeffrey P. Spike

Abstract: A fourteen year old is diagnosed with aplastic anemia. The teen and his parents are Jehovah’s Witnesses. An ethics consult is called on the day of admission by an ethically sophisticated social worker and attending. The patient and his parents see this diagnosis as “a test of their faith.” The ethical analysis focuses on the mature minor doctrine, i.e. whether the teen has the capacity to make this decision. The hospital chooses to take the case to court, with a result that is at odds with the ethics consultation recommendations. Ethics was never deposed or otherwise invited to be involved with the hearing. Thus the larger question of the relation of ethics and law was brought into stark relief.

Keywords: Adolescent, Capacity, Child Neglect, Decision-making Capacity, Ethics Consultation, Informed Consent, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Mature Minor, Religion, Religious Belief, Right to Refuse Treatment, Teen, Teenager

- What is the relationship between law and ethics? When they conflict, which should prevail?

- At one point, the author of this case study says, of trying to convince his young patient of the benefit of treatment: “…but that seemed coercive. In fact, far too many patients act out of fear and accept treatment that has virtually no choice of benefit.” In this case, where Luke would have greatly benefitted from treatment, where is the line to be drawn between thoroughly informing him and coercing him?

- Are there ever circumstances where it might be disadvantageous to have an ethics consultation?

- Anderson & Associates, P.C. (2015). Illinois Recognizes the “Mature Minor Doctrine” in Some Cases. Retrieved from: http://www.andersondivorcelawchicago.com/chicagodivorceattorney/2015/01/29/illinois-mature-minor-doctrine-states/

Pauley, M. (2011). National Health Care Decisions Day, Jehovah’s Witnesses & Mature Minors. Marquette University Law School Faculty Blog. Retrieved from: http://law.marquette.edu/facultyblog/2011/04/14/national-health-care-decisions-day-jehovahs-witnesses-mature-minors/

- Jehovah’s Witnesses: The Surgical/Ethical Challenge. (1981). JW.org. Retrieved from: http://www.jw.org/en/publications/books/blood/jehovahs-witnesses-the-surgical-ethical-challenge/

3. Advance Directives, Preemptive Suicide, and Emergency Medicine Decision Making

Richard L. Heinrich, Marshall T. Morgan, Steven J. Rottman

Abstract: As the United States population ages, there is a growing group of aging, elderly, individuals who may consider "preemptive suicide"(Prado, 1998). Healthy aging patients who preemptively attempt to end their life by suicide and who have clearly expressed a desire not to have life -sustaining treatment present a clinical and public policy challenge. We describe the clinical, ethical, and medical-legal decision making issues that were raised in such a case that presented to an academic emergency department. We also review and evaluate a decision making process that emergency physicians confront when faced with such a challenging and unusual situation.

Keywords: Aging, Autonomy, Advance Directives, Emergency Department, Preemptive Suicide

- Can we rely on the perspective of a patient to trust that a logical decision about preemptive suicide is being made?

- In this case, the family supported the patient’s decision, and thus gave it more credence. When the patient and family disagree, which view should prevail?

- What could the medical team have done prior to providing treatment in order to clarify their patient’s DNR wishes?

- Suicide is currently illegal in the United States. Does the fact that it is illegal mean that it is wrong? Is there an ethical right to suicide, despite the fact that it is illegal?

- Gabbatt, A. (2009). Doctors acted legally in ‘living will’ suicide case. The Guardian. Retrieved from: http://www.theguardian.com/society/2009/oct/01/living-will-suicide-legal

- Tolchin, M. (1989). When long life is too much: suicide rises among elderly. The New York Times. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/1989/07/19/us/when-long-life-is-too-much-suicide-rises-among-elderly.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

- Appleby, J. (2014). ‘Prophylactic’ Suicide. The New York Times, Sunday Review. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/16/opinion/sunday/prophylactic-suicide.html

4. Healing the Physician’s Story: A Case of Narrative Medicine and End-of-Life Care

Lori A. Roscoe

Abstract: Telling stories after a loved one’s death helps surviving family members to find meaning in the experience and share perceptions about whether the death was consistent with the deceased person’s values and preferences. Opportunities for physicians to evaluate the experience of a patient’s death and to expose the ethical concerns that care for the dying often raises are rare. Narrative medicine is a theoretical perspective that provides tools to extend the benefits of storytelling and narrative sense–making to physicians. This case study describes narrative writing workshops attended by physicians who care for dying patients. The narratives created revealed the physicians’ concerns about ethics and their emotional connection with patients. This case study demonstrates that even one–time reflective writing workshops might create important opportunities for physicians to evaluate their experiences with dying patients and families.

Keywords: Death and Dying, End–of–Life Issues, Healthcare Professionals, Narrative Inquiry, Stories, Storytelling

- This piece extensively discusses the effects that narrative medicine can have for a practicing physician. What potential effects can it have on the other side of the doctor-patient interaction?

- What does the Japanese physician’s story suggest about the role that culture plays in the doctor-patient experience?

- Is it possible for a physician to be truly empathetic with his or her patients? Why or why not?

- Should medical schools across the country include narrative medicine in their curriculum? Why or why not?

- Chen, PW. (2008). Stories in the Service of Making a Better Doctor. The New York Times. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/24/health/chen10-23.html?pagewanted=all

- Geisler, SL. (2006). The Value of Narrative Ethics to Medicine. The Journal of Physician Assistant Education. Retrieved from: http://www2.paeaonline.org/index.php?ht=action/GetDocumentAction/i/25232

5. The Efficacy of Ethics Discernment in the Organizational Context: The Case of Post-Offer Nicotine Screening

David M. Belde

Abstract: This article examines the efficacy of an ethics discernment process in the organizational context, a practice referred to in the paper as "mission due diligence." This type of ethics discernment is a structured process intended to awaken the ethical concerns that a particular issue raises within moral agents and to give voice, directly and indirectly, to those who will be impacted by, and responsible for, strategic decision-making. The efficacy of this particular ethics discernment practice is contingent upon several realities, including, but not limited to 1) the timing in which it is undertaken, 2) the degree of importance and relevance attributed to it, and 3) the skills of the person leading it. This case report examines how this process was used to highlight and address the ethical issues related to a new hiring policy, namely, a mandatory nicotine screening test for prospective employees in the healthcare context. Framed by the Bon Secours Virginia Health System hiring process, the author explores the importance of diligently focusing on ethical considerations in the organizational realm while still maintaining true to the virtues of the network.

Keywords: Ethics Discernment, Nicotine Screening, Organizational Ethics

- The author says, “Virtually all organizational ethics programs have to grapple with their overall importance and relevance within an organization.” How much authority should an ethics program within a hospital be afforded?

- If an employer can show sufficient empirical results for why a drug test is necessary, is it warranted? Do the sufficient reasons have to be related to the patients’ best interests?

- What are the different ways that Catholicism affects the ethical considerations in this case? What role does religion play in ethical consultations in general?

- Why does the author say balancing advocacy and inquiry are so important?

- Tucker, M & Salazar, L. (2014). Cotinine testing may violate the American with Disabilities Act (ADA), the ADA Amendments Act (ADAAA), and state laws. Wells Fargo Insights. Retrieved from: https://wfis.wellsfargo.com/insights/clientadvisories/pages/cotininetestingmayviolateadaandotherlaws.aspx

- Our Values. Bons Secours Health System. Retrieved from: http://hso.bonsecours.com/about-us-our-mission-our-values.html

- Framework for Ethical Discernment. (2014). The Taylor University Center for Ethics. Retrieved from: http://ethics.taylor.edu/framework-for-ethical-discernment/

6. Can We Talk About Sex?

Mindy B. Statter

Abstract: A three–year–old female undergoes elective inguinal hernia repair and unexpectedly is found to have testes in the hernia sacs. A recommendation is made not to disclose the patient’s genotype to her mother. This case study addresses the ethical conflict of whether to disclose the patient’s male genotype to the parent that has been raising the child as female.

Keywords: Autonomy, Beneficence, Complete Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome, Disclosure, Informed Consent, Intersex, Nonmaleficence

- In what—if any—circumstances is it ethically acceptable to withhold medical information about a child from the primary caretaker?

- Now that disclosure of a CAIS diagnosis is mandatory, what responsibility would a parent potentially have to override a doctor’s recommendations for gender maintenance?

- This case highlights the ethical risks and potential consequences later in life of not disclosing a patient’s CAIS diagnosis and treatment. Conversely, what would the consequences be for disclosing?

- Ignoring the medical precedents set now, do you believe the doctor in this case should have felt remorse for not disclosing the full nature of the girl’s condition to her mother? Would her mother have been equipped to handle that knowledge at that time?

- Dreger, AD. (1998). “Ambiguous Sex”—or Ambivalent Medicine? The Hastings Center Report. Retrieved from: http://www.isna.org/articles/ambivalent_medicine

- Intersex Conditions, Human Diversity Resources. UConn Health Center. http://uchc.libguides.com/humandiversity/intersex

- Georgiann Davis. "Normalizing Intersex: The Transformative Power of Stories." Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics 5.2 (2015): 87-89. Project MUSE. Web. 8 Dec. 2015

7. Should We Tell Annie?: Preparing for Death at the Intersection of Parental Authority and Adolescent Autonomy

Erica K. Salter

Abstract: This case analysis examines the pediatric clinical ethics issues of adolescent autonomy and parental authority in medical decision–making. The case involves a dying adolescent whose parents request that the medical team withhold diagnosis and prognosis information from the patient. The analysis engages two related ethical questions: Should Annie be given information about her medical condition? And, who is the proper decision–maker in Annie’s case? Ultimately, four practical recommendations are offered.

Keywords: Adolescent, Decision-making Capacity, End of Life Care, Mature Minor, Parental Consent

- At what age do teens develop the ability to make autonomous decisions for themselves? What factors unique to adolescence might enhance or detract from this ability?

- What factors should be considered in deciding whether an adolescent should be given decision-making authority? Why?

- Is it ever appropriate for medical practitioners to lie to a child (or actively conceal the truth from a child)? Why or why not?

- Was it appropriate of the new attending doctor to call the palliative care physician? How could that miscommunication have been prevented?

- Hill, JB. (2012). Medical Decision Making by and on Behalf of Adolescents: Reconsidering First Principles. Faculty Publications. Retrieved from: http://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1081&context=faculty_publications

- Leonard, K. (2015). Case Sparks Debate About Teen Decision Making in Health. U.S. News and World Report. Retrieved from: http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2015/01/22/case-sparks-debate-about-teen-decision-making-in-health

8. A Case of Deceptive Mastectomy

Rebecca Volpe, Maria Baker, George F. Blackall, Gordon Kauffman, Michael J. Green

Abstract: This paper poses the question, “what are providers’ obligations to patients who lie?” This question is explored through the lens of a specific case: a 26–year–old woman who requests prophylactic bilateral mastectomy with reconstruction reports a significant and dramatic family history, but does not want to undergo genetic testing. Using a conversational–style discussion, the case is explored by a breast surgeon, genetic counselor/medical geneticist, clinical psychologist, chair of a hospital ethics committee and director of a clinical ethics consultation service.

Keywords: Clinical Ethics, Deceit, Lying, Provider/Patient Relationship, Providers’ Obligations

- Do you believe that the patient-doctor relationship should be reciprocal? Does the Hippocratic Oath mandate that doctors uphold their duties regardless of patient behavior?

- This case study asks us to consider typical signals that the doctors relied on when initially deciding whether or not to trust the patient. They cite qualities like her attractiveness, her maturity, and her husband’s support in order to explain their initial trust. Should they have been more skeptical in the beginning? Why were they so willing to believe the patient’s story at face value?

- Aside from the guilt that the surgeon himself would likely have felt, what might have been some potential consequences for the ethics team and hospital in general if the surgery had been successfully performed? What if it had gone badly?

- Polta, A. (2014). Lying to the Doctor. Center for Advancing Health, Prepared Patient Blog. Retrieved from: http://www.cfah.org/blog/2014/lying-to-the-doctor

- Ludwig, M & Burke, W. (2013). Physician-Patient Relationship. Ethics in Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine. Retrieved from: http://depts.washington.edu/bioethx/topics/physpt.html

- Observer Staff. (2000). What Should Plastic Surgeons Do When Crazy Patients Demand Work? Observer. Retrieved from: http://observer.com/2000/07/what-should-plastic-surgeons-do-when-crazy-patients-demand-work/

9. Do Everything

H. Rex Greene

Abstract: A 57–year–old with an incurable cancer suffered an abdominal catastrophe, putting him in the ICU, comatose with no chance of survival. His attending oncologist had only met him once and had no knowledge of his goals of care. Lacking an advance directive the staff turned to his family, who said, “Do everything.” This loaded statement was thought to be a demand for futile care even though it ultimately proved a reflection of their emotional response to a terrible, unanticipated event, not an irrational demand for useless care. A sympathetic exploration of the patient’s goals and expectations with his family using Buckman’s SPIKES format disclosed that their major concern was that he not die on his wife’s birthday. The family agreed to withdraw him from ventilator support the following day. Unraveling a medical conflict requires a sensitive process of shared decision–making based on a transparent process of clinical reasoning that synthesizes patient and family values with medical knowledge and ethical duties. Properly done, the outcome usually is a satisfactory experience for all concerned.

Keywords: Abandonment, Advance directives, Catastrophic Illness, Clinical Reasoning, Conflict Resolution, Decisional Capacity, Do Everything, Futility, Paternalism, Shared Decision Making, SPIKES, Substituted Judgment

- This case explains that responding appropriately to a request to “do everything” requires doctors to ensure that patients’ families “know the medical facts, delivered in a kind, caring fashion.” Sometimes, it can take many meetings over several days for the family to absorb the medical facts. How should decisions be made in the meantime?

- The conclusion of this case seems to reaffirm that emotion is more important than reason when approaching difficult conversations with patients’ families. Should emotion-based education and empathy training be offered in the modern medical school curriculum? Is it even possible to train physicians to be more emotionally intelligent?

- Why is the establishment of the goal of treatment so important to the unity of a patient, their family, and their doctor? What are the barriers to establishing goals of care?

- Baile, WF. et al. (2000). SPIKES—A Six Step Protocol for Delivering Bad News: Application to the Patient with Cancer. The Oncologist. Retrieved from: http://theoncologist.alphamedpress.org/content/5/4/302.full

- Medical Futility. (2007). ACOG Committee Opinion No. 362. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. Retrieved from: http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Ethics/Medical-Futility

- Enhancing Communication and Coordination of Care. (2013). Cardinal Glennon. Retrieved from: http://www.cardinalglennon.com/Documents/Forms/AllItems.aspx?RootFolder=http%3a%2f%2fwww%2ecardinalglennon%2ecom%2fDocuments%2femergency-medicine&FolderCTID=0x0120000161C93D9B68B34BA6E74A98204CE2A1

10. Responding to the Refusal of Care in the Emergency Department

Jennifer Nelson, Arvind Venkat, Moira Davenport

Abstract: The emergency department (ED) serves as the primary gateway for acute care and the source of health care of last resort. Emergency physicians are commonly expected to rapidly assess and treat patients with a variety of life–threatening conditions. However, patients do refuse recommended therapy, even when the consequences are significant morbidity and even mortality. This raises the ethical dilemma of how emergency physicians and ED staff can rapidly determine whether patient refusal of treatment recommendations is based on intact decision–making capacity and how to respond in an appropriate manner when the declining of necessary care by the patient is lacking a basis in informed judgment. This article presents a case that illustrates the ethical tensions raised by the refusal of life–sustaining care in the ED and how such situations can be approached in an ethically appropriate manner.

Keywords: Decision–making Capacity, Emergency Department, Emergency Physician, Informed Consent, Treatment Refusal

- Does coming to the Emergency Department constitute implied consent to treatment? Why would a patient come to the ED if not to receive potentially life-sustaining treatments at a physician’s recommendation?

- If it is evident that a patient lacks decision-making capacity, is it paternalistic to administer life-saving treatment even if the patient refuses?

- In this case, would it be ethically appropriate for the physicians to consult the patient’s family, in order to bring in one more agent of authority?

- Cooper, S. (2010). Taking No for an Answer—Refusal of Life-Sustaining Treatment. AMA Journal of Ethics/Virtual Mentor. Retrieved from: http://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/2010/06/ccas2-1006.html

- ACEP Code of Ethics for Emergency Physicians. (2008). Retrieved from: https://www.acep.org/Clinical---Practice-Management/Code-of-Ethics-for-Emergency-Physicians/

11. I Don’t Know Why I Called You

Jeffrey S. Farroni, Colleen M. Gallagher

Abstract: This case study details a request from a patient family member who calls our service without an articulated ethical dilemma. The issue that arose involved the conflict between continuing further medical interventions versus transitioning to supportive or palliative care and transferring the patient home. Beyond the resolution of the ethical dilemma, this narrative illustrates an approach to ethics consultation that seeks practical resolution of ethical dilemmas in alignment with patient goals and values. Importantly, the family’s suffering is addressed through a relationship driven, humanistic approach that incorporates elements of compassion, empathy and dialog.

Keywords: End of life, Empathy, Relationships, Clinical Ethics

- How can healthcare providers and ethicists strike a balanced middle-ground between being too detached and too empathetic? Which side of this split should they err on? Why?

- In this case, how did the patient’s family’s expectations influence the decision-making of the ethicist and the doctors?

- How can an ethicist’s varied background bring new knowledge and insight to a collaborative ethical deliberation?

- Shelton, WN & White, BD. (2015). Realistic Goals and Expectations for Clinical Ethics Consultations: We Should Not Overstate What We Can Deliver. The American Journal of Bioethics. Retrieved from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/15265161.2014.974773

- American Society for Bioethics and Humanities Clinical Ethics Task Force. Improving Competence in Clinical Ethics Consultation: A Learner’s Guide. Retrieved from: http://www-3.unipv.it/centrodibioetica/resources/Improving_Competence_in_Ethics.pdf

12. Undocumented and at the End of Life

Annette Mendola

Abstract: Three of the most contentious issues in contemporary American society—allocation of medical resources, end of life care, and immigration—converge when undocumented immigrant patients are facing the terminal phase of chronic illness. The lack of consistent, pragmatic policy in each of these spheres leaves us with little guidance for how to advocate for undocumented patients at the end of life. Limited resources and growing need compound the problem. Care for patients in this unfortunate situation should be grounded in clinical and economic reality as well as respect for the dignity of the individual to avoid exacerbating inequalities.

Keywords: Allocation of Resources, Dialysis, ESRD, End–of–Life Care, Undocumented Patients

- How does Henri’s lack of citizenship or permanent residence in the United States limit not only his access to, but his knowledge of, the full range of medical options available to him? Does this make him vulnerable, and therefore deserving of increased protections, in a way that other patients are not?

- Was it Henri’s right to refuse hospice, considering the lack of other options available? Why or why not?

- Should the ethics consulting team have made more of an effort to communicate to Henri that Lucia was no longer willing to be his caregiver? Why would this matter?

- Is a partial treatment of a severely ill patient worth the effort, or just a waste of time and resources? What is the apparent stance of the ethics committee on this question?

- Kimball, C. “End-of-Life Health Care Disparity: A Case Study”. Nursing Economics. Retrieved from: https://www.nursingeconomics.net/necfiles/news/End-Of-Life_Care_Kimball.pdf

- Ortega, AM. (2014). “Stay or Go? Terminally Ill Undocumented Immigrants Face Dilemma”. New America Media. Retrieved from: http://newamericamedia.org/2014/01/undocumented-and-dying-latinos-may-find-comfort-in-final-journey-home.php

13. Dax’s Case Redux: When Comes the End of the Day?

Ashley R. Hurst, Dea Mahanes, Mary Faith Marshall

Abstract: Forty years after Dax Cowart fought to have his voice heard regarding his medical treatment, patient autonomy and rights are at the heart of patient care today. Yet, despite its centrality in patient care, the tension between a severely burned patient’s right to stop treatment and the physician’s role in saving a life has not abated. As this case study explores, barriers remain to hearing and respecting a patient’s treatment decisions. Dismantling these barriers involves dispelling the myths that burn patients must grin and bear intense pain to recover and that a patient’s choice to discontinue treatment equals physician failure. Moreover, in these situations, sustained, direct engagement between physician and patient can reduce the moral distress of all involved and enable physicians to hear and better accept when a patient is calling for the end of the day.

Keywords: Dax Cowart, Ethics Consultation, Moral Distress, Palliative Care, Patient Autonomy

- Communication between a patient and his or her care team is crucial in cases like this. Why did the avenues of communication break down in this piece? What could have been done to improve the relationship between the patient and the medical team?

- What obligation did the physicians have to be visiting the patient and witnessing the implications of his wound care? If their behavior had been different, how might that have changed the course of treatment for the patient?

- Was the sheer number of people in the room for the patient’s first consult coercive? What could have been done differently to understand both the patient’s wishes and the team’s perspective earlier in the process?

- Does the possibility of a high quality of life post-treatment warrant or justify doctors’ prescribing painful treatment over a patient’s objections?

- “Dax’s Case” preview. (1984). Retrieved from: http://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/1630976

- Kavan, MG, Elsasser, GN, Barone, EJ. (2012). The Physician’s Role in Managing Acute Stress Disorder. Am Fam Physician. Retrieved from: http://www.aafp.org/afp/2012/1001/p643.html

- Requests to Die: Non-Terminal Patients. Mhhe. Retrieved from: http://novella.mhhe.com/sites/dl/free/0078038456/1037408/Pen38456_Ch02.pdf

14. Desperately Seeking a Surrogate— For a Patient Lacking Decision-Making Capacity

Martin L. Smith, Catherine L. Luck

Abstract: Our hospital’s policy and procedures for “Patients Without Surrogates” provides for gradated safeguards for managing patients’ treatment and care when they lack decision–making capacity, have no advance directives, and no surrogate decision makers are available. The safeguards increase as clinical decisions become more significant and have greater consequences for the patient. The policy also directs social workers to engage in “rigorous efforts” to search for surrogates who can potentially provide substituted judgments for such patients. We describe and illustrate the policy, procedures, and kinds of expected rigorous efforts through our narration of an actual but disguised case for which we provided clinical ethics guidance and social work expertise. Our experience with and reflection on this case resulted in four recommendations we make for health care facilities and organizations that aim to provide quality care for their own patients without surrogates.

Keywords: Clinical Ethics, Decision–Making Capacity, End–of–Life Decisions, Ethics Committee, Ethics Consultation Service, Patients Without Surrogates, Rigorous Efforts, Social Work, Surrogate Decision Maker, Unbefriended Patient, Unrepresented Patient

- While this author cautions against using social media to determine a surrogate, do you think it could be a reliable method of determining a close relationship?

- Does your state allow non-family members to serve in the role of surrogate decision-maker?

- If there had been sufficient grounds for Sally to be Jacob’s surrogate, do you think she would have come to the same conclusions as Jacob’s brother? Could the process have been expedited, and yet be just as reliable?

- Stanford Hospitals and Clinics. (2009). Health Care Decisions for Patients Who Lack Capacity and Lack Surrogates. Retrieved from: http://www.thaddeuspope.com/images/Stanford_Health_Care_Decisions_For_Patients_Who_Lack_Capacity_and_Surrogates_7_09.pdf

- Varma, S & Wendler, D. (2007). “Medical Decision Making for Patients Without Surrogates”. Arch Intern Med. Retrieved from: http://ogg.osu.edu/site_documents/sage/course3/wk8_varma.pdf

15. What to Say When: Responding to a Suicide Attempt in the Acute Care Setting

Arvind Venkat, Jonathan Drori

Abstract: Attempted suicide represents a personal tragedy for the patient and their loved ones and can be a challenge for acute care physicians. Medical professionals generally view it as their obligation to aggressively treat patients who are critically ill after a suicide attempt, on the presumption that a suicidal patient lacks decision making capacity from severe psychiatric impairment. However, physicians may be confronted by deliberative patient statements, advanced directives or surrogate decision makers who urge the withholding or withdrawal of life sustaining treatments based on the patient’s underlying medical condition or life experience. How acute care providers weigh these expressions of patient wishes versus their own views of beneficence, non–maleficence and professional integrity poses a significant ethical challenge. This article presents a case that exemplifies the medical and ethical tensions that can arise in treating a patient following a suicide attempt and how to approach their resolution.

Keywords: Advanced Directives, Critical Care, Life–sustaining Treatment, Suicide, Surrogate Decision Maker

- Can suicide ever be a rational, autonomous decision? Why or why not?

- How can patient/family relationships pose a challenge for doctors trying to establish the best course of action for a patient?

- How did the family’s perspective affect the patients’ treatment in this case? Was the outcome of their input positive or negative?

- In the absence of both a clear patient advance directive and familial knowledge of patient preferences, how should medical decisions be made? What did the doctors do in this case?

Web resources:

- Carrigan, CG & Lynch, DJ. (2003). Managing Suicide Attempts: Guidelines for the Primary Care Physician. Primary Care Comparnion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. Retrieved from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC419387/

- Sokol, D et al. (2011). Ethical dilemmas in the acute setting: a framework for clinicians. BMJ. Retrieved from: http://www.medicalethicist.net/documents/Tattoo%20BMJ%20PDF.pdf

- Forster, PL & Wu, LH. Assessment and Treatment of Suicidal Patients in an Emergency Setting. Gateway Psychiatric Services. Retrieved from: https://www.gatewaypsychiatric.com/pdf/Assessment%20and%20Treatment%20of%20Suicidal%20Patients%20in%20an%20Emergency%20Setting.pdf

16. Conversation and the Jehovah’s Witness Dying From Blood Loss

D. Malcolm Shaner, Jateen Prema

Abstract: Religious belief can complicate the usual management of seriously ill patients when the patient is a Jehovah’s Witness and the treatment is a blood transfusion. This narrative highlights critical points in a discussion of two cases wherein the process to promote an exercise of free will also becomes an exercise for the ethics consultant and healthcare team. Despite a medical care program’s carefully considered additions to an electronic healthcare record, additional conversation, investigation, preparation, and an open mind are required. Helping conflicted family members and considering whether and in what context to contact the Jehovah’s Witness Hospital Liaison Committee complicates the approach.

Keywords: Blood Transfusion, Jehovah’s Witness, Religious Rights

- Consider the differences between the two cases with regard to how the hospital handled the patient requests. What did the hospital do well, and what could it have improved?

- In Case 1, what was the effect of attempting the surgery once the patient had changed his mind? How did that change influence the perspective of both the doctors and the patient’s mother?

- In Case 1, was the medical officer’s frankness with the patient appropriate, taking into consideration the beliefs that the patient already expressed?

- How did the doctors in Case 2 actively facilitate moral decision making on the part of the patient?

- Panico, ML et al. (2011). “When a Patient Refuses Life Saving Care”. Am J Kidney Dis. Retrieved from: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/751273

- Robinson, BA. (2010). “Jehovah’s Witnesses’ (WTS) opposition to blood transfusions”. Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance. Retrieved from: http://www.religioustolerance.org/witness11.htm

17. Caregivers’ Role in Maternal-Fetal Conflict

Abstract: The case, which occurred in a public hospital in Turkey in 2005, exhibits a striking dilemma between a mother’s and her fetus’ interests. For a number of reasons, the mother refused to cooperate with the midwives and obstetrician in the process of giving birth, and wanted to leave the hospital. The care providers evaluated the case as a matter of maternal autonomy and asked the mother to give her consent to be discharged from the hospital, which she did despite the fact that her cervix was fully open. She left the hospital and gave birth shortly thereafter. Subsequently, the baby died two days later. In light of contemporary ethical principles, the mother’s competency could be debatable due to the physical and psychological conditions the mother confronted. Furthermore, protection of the fetus’ life should have been taken into account by the caregivers when making a decision concerning discharging of the mother.

Keywords: Ability to Consent, Autonomy, Beneficence, Decision Making Capacity, Ethical Dilemma, Fetal Beneficence, Fetal Rights, Maternal Autonomy, Maternal–Fetal Conflict, Pregnancy

- Did the mother have the right to demand to leave? Would your answer to this question change if discharging the mother endangered the fetus? Why or why not?

- Was the mother in a position to make an autonomous choice? Other than autonomous patient decision-making, are there models of decision-making that might have been considered in this case? How might they be applied?

- How could the care team have done better? Should a hospital have policies to help prevent or address such a situation? If so, what would these policies look like?

- Schetter, CD & Tanner, L. (2012). Anxiety, depression, and stress in pregnancy: Implication for mothers, children, research, and practice. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. Retrieved from: http://health.psych.ucla.edu/CDS/documents/DunkelSchetterTanner-2012COPsychiatry.pdf

- Post, LF. (1996). Bioethical Consideration of Maternal-Fetal Issues. Fordham Urban Law Journal. Retrieved from: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2171&context=ulj

18. The Surgeon as Stakeholder: Making the Case Not to Operate

Abstract: Surgeons are in a unique position, serving as gatekeepers to the operating room. They determine if operations are possible, are indicated, and have a reasonable risk–to–benefit profile. When an operation is indicated and the patient is amenable to it, the conversation between surgeon and patient is usually straightforward. On the other hand, when a patient’s co–morbidities substantially increase the risk of operative intervention, surgeons often question the utility of offering their services. These situations become immensely more difficult when patients have the expectation of being offered surgical treatment. This case describes the clinical encounter between an endocrine surgeon and an 83–year–old woman who has been incidentally found to have adrenal metastasis from melanoma. The patient wants an operation that the surgeon is reluctant to offer because of her frailty and high operative risk. The case focuses on the ethical dilemma that arises when a patient wants an operation that a surgeon does not want to perform.

Keywords: Metastatic Melanoma, Palliative Care, Respect for Autonomy, Shared Decision–Making, Surgical Ethics

- What reasons are acceptable for refusing to operate on a patient? Why?

- How should surgeons approach situations in which they are consulted for operative interventions that they do not want to provide?

- When surgeons think the risk of surgery is too great and not justified but patients think the risks are worthwhile, whose assessment should prevail? Why?

- Louden, K. (2015).“Risk Calculator Does Not Alter Surgeons’ Choice to Operate". Medscape. Retrieved from: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/852708

- Kasman, DL. (2004).“When is Medical Treatment Futile?: A Guide for Students, Residents, and Physicians." Journal of General Internal Medicine. Retrieved from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1492577/

19. The Enduring Case

Craig M. Nelson

Abstract: In clinical ethics an enduring case takes on a life of its own and comes to closure over a long period of time. This essay describes the evolution of such a case over a 1–year period. The case involves a 90–year old male patient with multiple chronic medical conditions who lacked decision–making capacity, was a resident of a long–term care facility, and did not have known previously expressed wishes regarding medical treatment. The ethics consultation initially revolved around this question: What method or process must be employed so that medical treatment decisions could be ethically reviewed and could include a shared decision–making process for Mr. Smith? This case analysis describes the evolution of this case and argues that the good of the patient must remain paramount throughout an enduring case.

Keywords: Ethical Appropriateness, Ethical Process, Moral Community, Treatment Planning

- What kinds of processes might help an incapacitated patient’s voice be heard, especially when the patient’s values were never formally documented?

- Why might it be important to try to give voice to an incapacitated patient’s values?

- What went well with the process in this clinical ethics consultation? Might there be opportunities for improving the processes deployed in this case, and if so, what might they be?

- Ten Myths About Decision-Making Capacity: A Report by the Natioanl Ethics Committee Of the Veterans Health Administration. (2002). Retrieved from: http://www.ethics.va.gov/docs/necrpts/nec_report_20020201_ten_myths_about_dmc.pdf

- California Advance Health Care Directive Probate Code Section 4701. Retrieved from: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displayText.xhtml?lawCode=PROB&division=4.7.&title=&part=2.&chapter=2.&article=

20. Military Health Care Dilemmas and Genetic Discrimination: A Family’s Experience with Whole Exome Sequencing

Benjamin M. Helm, Katherine Langley, Brooke B. Spangler, Samantha A. Schrier Vergano

Abstract: Whole–exome sequencing (WES) has increased our ability to analyze large parts of the human genome, bringing with it a plethora of ethical, legal, and social implications. A topic dominating discussion of WES is identification of “secondary findings" (SFs), defined as the identification of risk in an asymptomatic individual unrelated to the indication for the test. SFs can have considerable psychosocial impact on patients and families, and patients with an SF may have concerns regarding genomic privacy and genetic discrimination. The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 (GINA) currently excludes protections for members of the military. This may cause concern in military members and families regarding genetic discrimination when considering genetic testing. In this report, we discuss a case involving a patient and family in which a secondary finding was discovered by WES. The family members have careers in the U.S. military, and a risk–predisposing condition could negatively affect employment. While beneficial medical management changes were made, the information placed exceptional stress on the family, who were forced to navigate career–sensitive “extra–medical" issues, to consider the impacts of uncovering risk–predisposition, and to manage the privacy of their genetic information. We highlight how information obtained from WES may collide with these issues and emphasize the importance of genetic counseling for anyone undergoing WES.

Keywords: Genetic Discrimination, Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 (GINA), Genetic Testing, Incidental Findings, Military, Secondary Findings

- It is clear that this type of genetic testing is revolutionizing diagnoses, but it comes with ethical concerns. Do the advantages of WES outweigh the possible disadvantages? Why or why not?

- Do you agree that pre–test conversations should be required in every scenario? Why or why not?

- When the SCN5A gene mutation was found, should the father have told his superiors? Why or why not?

- The SCN5A mutation is probabilistic–not all individuals who have the mutation will develop symptoms. However for some patients, the only presenting feature is sudden cardiac death. What are some reasons patients might have for—and against—wanting this information?

- National Human Genome Research Institute. (2014a). Fact sheet: Genetic discrimination. Retrieved from: http://www.genome.gov/10002077

- Majewski, J. et al., (2011). What Can Exome Sequencing Do For You? Journal of Medical Genetics. Retrieved from: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/749695_1

- Collins, F. (2007). The threat of genetic discrimination to the promise of personality medicine. Testimony to the United States House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means. Retrieved from: http://waysandmeans.house.gov/Media/pdf/110/3-14-07/CollinsTestimony.pdf

21. Conflicting Values: A Case Study in Patient Choice and Caregiver Perspectives

Margot Eves, Phoebe Day Danziger, Ruth M. Farrell, Cristie M. Cole

Abstract: Decisions related to births in the “gray zone" of periviability are particularly challenging. Despite published management guidelines, clinicians and families struggle to negotiate care management plans. Stakeholders must reconcile conflicting values in the context of evolving circumstances with a high degree of uncertainty within a short time period. Even skilled clinicians may struggle to guide the patient in making value–laden decisions without imposing their own values. Exploring the experiences of one pregnant woman and her caregivers, this case study highlights how bias may undermine caregivers’ ability to meet their obligation to enhance patient autonomy and the moral distress they may experience when a patient’s values do not align with their own. Management strategies to mitigate the potential impact of bias and related moral distress are identified. The authors then describe one management strategy used in this case, facilitated ethics consultation, which is focused on thoughtful consideration of the patient’s perspective.

Keywords: Bias, Ethics Consultation, “Gray Zone", Moral Distress, Perspective–Taking

- How can we distinguish between concerns that reflect bias versus concerns that reflect legitimate differences in values?

- Does it matter if a patient’s choices reflect bias, or do patients have the right to have their decisions respected even if they are based on potentially unsubstantiated biases or beliefs?

- Given the controversial nature of the patient’s viewpoint regarding life with disabilities, did the providers have an obligation to try to mitigate the patient’s bias? Why or why not?

- What are some of the ways that the providers could have tried to address the patient’s biases regarding life with a disability? For example, should the patient have been offered the opportunity to speak to parents of children with disabilities, specifically those disabilities more likely to be a result of complications from prematurity? Would it be ethically permissible to require that she do so?

- Are there other, more effective ways to support professionals who take care of patients whose values and choices differ so significantly from their own?

- Lyerly, AD. (2008). Reframing neutral counseling. Virtual Mentor. Retrieved from: http://virtualmentor.ama–assn.org/2008/10/ccas3–0810.html

- Guttmacher Institute. (2015). State policies in brief: An overview of abortion laws. New York: Guttmacher Institute. Retrieved from: http://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_OAL.pdf

22. Ethical Dilemmas Relating to the Management of a Newborn with Down Syndrome and Severe Congenital Heart Disease in a Resource-Poor Setting

Ama K. Edwin, Frank Edwin, Summer J. McGee

Abstract: Decision-making regarding treatment for newborns with disabilities in resource-poor settings is a diffi cult process that can put parents and caregivers in confl ict. Despite several guidelines that have helped to clarify some of the medical decision-making in Ghana, there is still no clear consensus on the specifi c moral criteria to be used. This article presents the case of a mother who expressed her wish that her child with Down syndrome should not have been resuscitated at birth. It explores the ethical issues at stake in both her misgivings about the resuscitation and her unwillingness to consider surgical repair of an atrioventricular (AV) canal defect. Knowing that children born with Down syndrome are able to pursue life’s goals, should our treatment of complete AV canal defect in such children be considered morally obligatory, even in resource-poor settings like Ghana?

Keywords: Atrioventricular Septal Defect, Down Syndrome, Ethical Duty, Newborn, Withholding Treatment

- What is the difference between a substantiated concern and one that reflects bias? How can providers assess the difference?

- The mother’s views about the relative lack of value of a person with disabilities are controversial and seem to reflect an unfair or unfounded bias. In light of this, did the provider have an obligation to try to address the mother’s bias?

- If health care providers had an obligation to try to mitigate or address the mother’s bias, how should they have attempted to do so? Should the mother have been required to speak to other parents of children with disabilities?

23. System Failure: No Surgeon To Be Found

Carol Bayley

Abstract: A woman admitted to the emergency room of a hospital died because no surgeon could be found to stop the bleeding from injuries she sustained in a farming accident. The case points to ethical shortcomings both institutionally and professionally. The call system is inadequate, and physician fears of being sued or insufficiently compensated contribute to the overall problem. Potential responses include the institutional equivalent of a root cause analysis and an understanding of the pressures brought to bear on physicians to treat emergencies.

Keywords: Emergency Call, Institutional Ethics, John Glaser, Organizational Ethics, Root Cause Analysis

- Do you think a physician has an ethical obligation to try to help a patient who will otherwise die, even when the patient’s problem is not within the physician’s specialty? If so, how do you ground this obligation? If not, why not?

- If physicians have such an obligation, what ought they to do when they face barriers to fulfilling it?

- People often see themselves in the best light; it’s very human to see one’s self favorably, and to try to explain away one’s own responsibility when an error occurs. In light of this natural tendency, what structures could be set into place to help physicians and other stakeholders take responsibility in these types of situations?

24. A Life Below the Threshold?: Examining Conflict Between Ethical Principles and Parental Values in Neonatal Treatment Decision Making

Thomas V. Cunningham

Abstract: Three common ethical principles for establishing the limits of parental authority in pediatric treatment decision–making are the harm principle, the principle of best interest, and the threshold view. This paper considers how these principles apply to a case of a premature neonate with multiple significant co-morbidities whose mother wanted all possible treatments, and whose health care providers wondered whether it would be ethically permissible to allow him to die comfortably despite her wishes. Whether and how these principles help in understanding what was morally right for the child is questioned. The paper concludes that the principles were of some value in understanding the moral geography of the case; however, this case reveals that common bioethical principles for medical decision–making are problematically value-laden because they are inconsistent with the widespread moral value of medical vitalism.

Keywords: Harm Principle, Best Interests, Threshold View, Neonatal Decision Making, Values, Medical Vitalism

- How should the ethicist think through the relationship between apparently competing bioethical views in particular clinical circumstances?

- Should there be a competency evaluation for parents, guardians, surrogates, or other proxy medical decision makers?

- Should society develop policies to limit health care in circumstances where there is an appreciable likelihood of extremely poor outcomes?

25. Ethical Challenges in the Care of the Inpatient with Morbid Obesity

Paul L. Schneider, Zhaoping Li

Abstract: Objective: To provide a thorough analysis of the range of ethical concerns that may present in relation to the care of the morbidly obese inpatient over the course of several years of care. Methods: A narrative of the patient’s complex medical care is given, with particular attention to the recommendations of three separate ethics committee consultations that were sought by his health care providers. An ethical analysis of the relevant issues is given within the Principles of Biomedical Ethics framework, highlighting the principles of autonomy, beneficence, non–maleficence, and justice. Results: The case study presents a patient with morbid obesity, obesity hypoventilation syndrome, and numerous ICU admissions. The first ethics consultation was requested regarding the permissibility of forcing bariatric surgery on him against his will. The second consultation was regarding a request by nursing staff to no longer attempt to mobilize him. The third was regarding the patient’s refusal to be discharged. Conclusions and Recommendations: The care of inpatients with morbid obesity presents a unique set of practical and ethical challenges to health care personnel. A disciplined approach to ethical analysis using the Principles of Biomedical Ethics framework may be helpful in dealing with these challenges. Recommendations for improvement are made for the individual and local settings, as well as nationally.

Keywords: Autonomy, Beneficence, Ethics, Justice, Morbid Obesity, Non–Maleficence, Paternalism, Professionalism

- Sometimes in health care there is a mismatch between a units’ ideal admission criteria and the actual patients admitted. Is it appropriate to try to help health care workers feel more comfortable with patients who are not ideal in some way? If so, are there limits to this approach?

- A “hard paternalism” approach in this case might have involved placing this patient on a locked unit so that he could not have restaurant deliveries. Given his dire clinical circumstances, could this have been ethically supported?

- Do you agree that providers were overly reliant on the principle of autonomy in allowing this patient to be poorly compliant with dietary therapy in the on–campus nursing home? If not, can you suggest alternate rationales?

26. The Clinical Bioethicist’s Role: Should We Aim to Relieve Suffering?

Deborah L. Kasman

Abstract: Bioethics consultants arrive at their profession from a variety of prior experiences (e.g., as physicians, nurses, or social workers), yet all clarify ethical issues in the care of patients. The integrated bioethicist’s role often extends beyond case consultations. This case presents a young person suffering a prolonged and gruesome end–of–life journey, which raised questions regarding the bioethicist’s role in alleviating suffering as part of the health care team. The case is used to illuminate forms of suffering experienced by patients, families, and health care providers. The question arises as to whether it is in the ethicist’s jurisdiction to alleviate suffering, and if the answer is “yes,” then whose suffering should be addressed? The discussion addresses one approach taken by an integrated bioethicist toward promoting delivery of ethical and compassionate care to the patient.

Keywords: Clinical Ethics Consultation, Healing, Meaning in Death, Provider Well–Being, Suffering

- Is relief of suffering part of a clinical ethics consultation? Should it be? Why or why not?

- How do you respond to suffering? What are your most productive responses? Unproductive responses?

- Should a clinical ethicist be involved in clinical care without maintaining direct patient contact? If patients/families refuse ethics involvement, what role can the clinical ethicist play in promoting ethical medical decision–making?

- When a clinical ethicist is also trained as a licensed health provider (e.g., physician, nurse, chaplain, or social worker), can prior clinical experience affect the ethicist’s role in responding to suffering? Can this be an advantage, a hindrance, or both?

27. To Enroll or Not to Enroll?: A Researcher Struggles with the Decision to Involve Study Participants in a Clinical Trial That Could Save Their Lives

Roberto Abadie

Abstract: Hundreds of thousands of clinical trials are conducted annually around the world, working to further scientific knowledge and expand medical treatment. At the same time, clinical trials also present novel challenges to researchers who have access to large pools of research participants and are routinely approached by pharmaceutical companies seeking to recruit subjects for clinical trials. This case study discusses the ethical dilemmas faced by a community health investigator who received an invitation to enroll people who inject drugs (PWID) into a clinical trial of a drug that promised a new treatment option for Hepatitis C. The author elaborates on the ethical tensions that he confronted between “doing good” and “avoiding harm. The paper suggests that issues of distributive justice should also be considered, particularly when the drugs being tested might eventually command prices that place them out of reach of the population enrolled in the trial. This case does not attempt to provide an ethical road map to assist researchers in similar circumstances, but rather to illustrate some of the considerations involved in making a decision about whether or not to participate in clinical trials research.

Keywords: Beneficence, Clinical Trials, Enrollment, Justice, Non-Maleficence

- Since they were originally formulated a few decades ago, the principle of respect for autonomy seems to have gained priority in detriment of the principle of justice. With drug prices reaching exorbitant levels—more than eighty thousand dollars for a full HCV treatment—placing access beyond the reach of many, shouldn’t bioethicists reconsider the way we think about justice?

- The principle of beneficence establishes the requirement of a social good, as one of if its main criteria. But drug prices seem to benefit the pharmaceutical industry while depriving many of much needed drugs. With this in mind, how do you think we should interpret this principle?