- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

Capital punishment and death row inmates: A research roundup

Our newest research roundup examines capital punishment from multiple angles, including prisoner experiences, factors that affect sentencing and how effectively the death penalty deters crime.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Denise-Marie Ordway, The Journalist's Resource May 6, 2019

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/criminal-justice/capital-punishment-death-row-research/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

Legislators in several states have filed bills aimed at abolishing capital punishment in recent months, as the number of men and women facing death sentences continues to drop nationally and conservative U.S. Supreme Court justices have expressed frustration over delays in carrying out executions .

Meanwhile, several prisoners are scheduled to die this month, including Donnie Edward Johnson , on death row in Tennessee for suffocating his wife in 1984, and serial killer Robert “Bobby” Joe Long , who murdered at least eight women in Florida in the early 1980s.

While more than half of U.S. states and the federal government allow capital punishment, most executions between 1976 and 2017 occurred in five states — Florida, Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas and Virginia, according to the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Men receive the overwhelming majority of death sentences. But more than a dozen women have been executed since 1976, when the U.S. Supreme Court lifted a moratorium on capital punishment.

While most death row prisoners die by lethal injection, many states allow other methods such as electrocution, hanging and firing squad. All executions in 2017, the most recent year for which the federal government provides data, were by lethal injection. A 2018 report from the U.S. Department of Justice offers a broad overview of the nation’s various capital punishment policies as well as a state-by-state tally of death row inmates and executions.

States that authorize capital punishment often post online rosters of their death row inmates. The roster for the Florida Department of Corrections, for example, shows there were 342 people on death row there as of early May 2019. In Idaho, there were eight .

Below, we’ve summarized 14 academic studies about capital punishment to help journalists ground their coverage and better understand the issue. This sampling of peer-reviewed research looks at capital punishment from multiple angles, including inmate experiences on death row, factors that affect sentencing and shifts in public opinion about the death penalty. We’ve also included several studies on prisoners’ last words.

———-

Impact of the news media

Disentangling Victim Gender and Capital Punishment: The Role of Media Phillips, Scott; Haas, Laura Potter; Coverdill, James E. Feminist Criminology , 2012.

This study of capital punishment cases in Texas suggests that the Houston Chronicle ’s news coverage of murder cases influenced prosecutors’ decisions about whether or not to seek the death penalty.

The researchers analyzed the criminal cases of 504 defendants indicted for capital murder in Harris County, Texas between 1992 and 1999. They discovered that 139 of the victims were female, 31 of whom were subject to “sexual degradation,” meaning they were either raped or raped and also “disrobed.” They also examined the newspaper’s coverage of these cases.

The researchers find that “sexual degradation shapes media coverage.” Cases that did not involve sexual degradation prompted 2.8 news articles each, on average, prior to the defendant’s indictment. If a victim was raped but not disrobed, the case generated an average of 4.4 articles. If the victim was raped and disrobed, the newspaper published an average of 14.7 articles about each case.

The analysis, according to the authors, shows that the district attorney “sought death in 9 of the 19 sexual degradation cases that generated 0 to 3 newspaper articles, compared to 11 of the 12 sexual degradation cases that generated 4 or more newspaper articles. Thus, sexual degradation alone — in the absence of intense media coverage — does not necessarily move the DA [district attorney] to seek death. But sexual degradation cases that catch the eye of the media also catch the eye of the DA. The data strongly suggest that the DA is aware of, and responsive to, media coverage of pending capital murder cases.”

Factors affecting sentencing

How Defendants’ Legal Status and Ethnicity and Participants’ Political Orientation Relate to Death Penalty Sentencing Decisions Alvarez, Mauricio J.; Miller, Monica K. Translational Issues in Psychological Science , 2017.

For this study, researchers sought to determine whether U.S. adults would punish a criminal defendant differently based on characteristics such as the defendant’s race, ethnicity and immigration status. The researchers recruited 300 U.S. citizens to read a 2,500-word summary of a mock murder trial and then asked them to decide whether to sentence the mock defendant, already found guilty of murder, to death or life in prison. Each participant also answered questions aimed at measuring their political orientation and other factors that might influence their decision-making, including their level of anti-immigrant bias.

Overall, survey participants gave harsher sentences to immigrant defendants than they did to defendants described as being born in the U.S. But sentencing decisions were influenced by participants’ political orientation. “More liberal and middle of the road participants viewed documented immigrant defendants as more deserving of the death penalty, compared to U.S. born defendants,” the authors write. On the other hand, more conservative participants “viewed documented immigrant defendants as being similarly deserving of the death penalty compared to U.S. born defendants.”

The researchers note that when they compared documented immigrant mock defendants with those who were naturalized citizens, “more liberal participants viewed documented immigrant defendants as more deserving of the death penalty than naturalized citizen defendants, while middle of the road and more conservative participants viewed both defendants as being similarly deserving of the death penalty.”

Possibility of Death Sentence Has Divergent Effect on Verdicts for Black and White Defendants Glaser, Jack; Martin, Karin D.; Kahn, Kimberly B. Law and Human Behavior , 2015.

Researchers conducted a national, web-based survey of a random sample of 276 U.S. adults to determine whether respondents would choose harsher sentences for black or white defendants on trial for murder. Respondents were asked to read a 1,185-word, four-page trial summary outlining the facts of a mock murder case, which was based on transcripts from actual murder trials in California. Survey participants — half were women and the vast majority were white — had to choose to convict or acquit the defendant.

Participants were given a version of the trial summary, which differed in two ways. In some versions, the defendant faced a death sentence while in others, he faced life in prison without the possibility of parole. Defendants were given “first names stereotypically associated with Blacks (Darnel, Lamar, Terrell) or Whites (Andrew, Frank, Peter).”

The main takeaways: Participants chose to convict nearly 73.9% of defendants whose names were associated with black men and 60.9% of defendants with names associated with white men. When study participants read the version of the case featuring a defendant facing a death sentence, they chose to convict 80% of defendants with black-sounding names and 56.5% of defendants with white-sounding names.

The authors write that their findings “indicate that, not only are potential jurors influenced by punishment severity, but defendant race alters how they are swayed — with deleterious outcomes for Black defendants. The demonstration that sentence severity, specifically, the possibility of a death sentence, has a qualitatively different effect on verdicts for ostensibly Black and White defendants is novel.”

Predictors of Death Sentencing for Minority, Equal, and Majority Female Juries in Capital Murder Trials Richards, Tara N.; et al. Women & Criminal Justice , 2016.

This study looks at the link between jury decisions in capital offense cases and the sex composition of juries in North Carolina between 1977 and 2009. It finds that juries with an equal number of male and female members “were associated with a 65% increase in the odds of recommending the death penalty.” When juries had seven or more female members, the odds of recommending a death sentence fell by 32%. The researchers did not find a statistically significant relationship between male-majority juries and sentencing decisions.

No Sympathy for the Devil: Attributing Psychopathic Traits to Capital Murderers Also Predicts Support for Executing Them Edens, John F.; et al. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment , 2013.

The personality traits that defendants exhibit during capital murder trials influence whether or not laypeople think they deserve the death penalty, this study suggests. “A defendant’s perceived lack of remorse in particular was influential, although perceptions of grandiose self-worth and a manipulative interpersonal style also contributed incrementally to support for a death sentence,” the authors write.

Researchers examined data from three studies — two published and one unpublished — to determine whether defendants’ personality traits affect attitudes about capital punishment. In all three studies, students recruited from a university in the southern U.S. were asked to choose a criminal sentence for a mock defendant after reading a summary of a mock murder trial. The higher the students rated the defendant on a “global psychopathy” scale, the more likely they were to choose a death sentence.

The researchers write that the results “inform how perceptions of socially undesirable personality traits relate to attitudes about the sanctioning of criminals, particularly murderers facing a possible death sentence. Our findings converge with other research … suggesting that perceived lack of remorse carries considerable weight in terms of influencing legal decision-makers.”

Public support for capital punishment

Racial-Ethnic Intolerance and Support for Capital Punishment: A Cross-National Comparison Unnever, James D.; Cullen, Francis T. Criminology , 2010.

This study finds that citizens of several European countries, including France, Great Britain and Spain, were more likely to support capital punishment if they were intolerant of racial and ethnic minorities.

The researchers analyzed a variety of surveys conducted in European nations between 1992 and 2006.

The main takeaway: “In France, Belgium, the Netherlands, East and West Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Denmark, Great Britain, Greece, Spain, Finland, Sweden, Austria, and Canada, individuals who were racially and ethnically intolerant — expressing animus toward immigrants — were significantly and substantively more likely to support the death penalty. In two countries, Portugal and Ireland, racial-ethnic intolerance did not positively predict support for either the death penalty or more general punitive attitudes,” the authors write.

The researchers also find that European youth with anti-immigrant attitudes were more likely to support capital punishment.

To Execute or Not to Execute? Examining Public Support for Capital Punishment of Sex Offenders Mancini, Christina; Mears, Daniel P. Journal of Criminal Just ice, 2010.

In this study, researchers examine whether the public agreed with a move by states in the 1990s to extend the death penalty to convicted sex offenders.

The researchers find, based on an analysis of a 1991 national telephone poll of 1,101 people, that the public’s views on punishing sex crimes with the death penalty depended on whether the victim was an adult or child. According to the opinion poll, conducted by the Minneapolis Star Tribune , 27% of Americans supported capital punishment for offenders who raped an adult while 51% favored it for offenders who sexually abused a child.

The researchers also find that people who believe sex offenders are prone to recidivism and that the criminal justice system does not do enough to address sex crime were more likely to support the death penalty for sex offenders.

“Vicarious experiences with sexual victimization — that is, knowing someone who was victimized — was associated with decreased support for executing such offenders,” the authors write.

As a crime deterrent

What Do Panel Studies Tell Us About a Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment? A Critique of the Literature Chalfin, Aaron; Haviland, Amelia M.; Raphael, Steven. Journal of Quantitative Criminology , 2013.

Researchers analyzed multiple published studies to try to gauge how effectively capital punishment deters homicide. What they learned: the academic literature is inconclusive.

“First, we believe that the empirical research in these papers is under-theorized and difficult to interpret,” the authors write. “Second, many of the papers purporting to find strong effects of the death penalty on state-level murder rates suffer from basic methodological problems.”

The authors also note the difficulty of studying the effects of the death penalty, considering states generally execute only a few people per year.

Assumptions Matter: Model Uncertainty and the Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment Durlauf, Steven N.: Fu, Chao; Navarro, Salvador. American Economic Review , 2012.

In this article, researchers look at some of the reasons why it’s still unclear whether capital punishment policies deter homicide. They examine how previous researchers’ assumptions about homicide influenced estimates for the number of lives saved when a convicted murderer is executed.

The authors’ explanation is technical and focuses on statistical modeling. “Depending on the model, one can claim that an additional criminal executed induces 63 additional murders or that it saves 21 lives,” the authors write. “This demonstrates the ease with which a researcher can, through choice of modeling assumptions, produce evidence that each execution either costs many lives or saves many lives.”

Inmate experiences on death row

Suicide on Death Row Tartaro, Christine; Lester, David. Journal of Forensic Sciences , 2016.

While death row inmates in the U.S. are supposed to be closely supervised, they are more likely to commit suicide than male prisoners who aren’t serving death sentences. They also are more likely to commit suicide than males over age 15 who are not incarcerated, according to this study.

From 1977 to 2010, there were an average of 2.74 suicides a year on death row. The average suicide rate was 129.70 deaths per 100,000 death row inmates. For state prison inmates not facing execution, the suicide rate was 17.41 deaths per 100,000 inmates, on average. And for males over age 15, it was 24.62 deaths per 100,000 people.

The researchers note that suicide rates for death row inmates and males in the general prison population have fallen gradually since the late 1970s. They also note that the suicide rate among death row inmates is lower during years when a greater number of death row inmates are executed.

Wasted Resources and Gratuitous Suffering: The Failure of a Security Rationale for Death Row Cunningham, Mark D.; Reidy, Thomas J.; Sorensen, Jon R. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law , 2016.

This study focuses on the behavior of death row inmates who were “mainstreamed” into the general prison population at a high-security prison in Missouri between 1991 and 2015. Elsewhere in the U.S., prisoners with death sentences tend to be segregated from other prisoners and placed in “supermaximum confinement” at a high cost to taxpayers.

The key takeaways: Over the 25-year period, not only were death row inmates as likely as or less likely than other prisoners to be involved in “assaultive misconduct,” but rates of violence among death row inmates were lower after they were mainstreamed than they had been when prisoners were segregated on death row.

“Because the CP [Capital Punishment] inmate has a limited life expectancy, he is arguably particularly motivated to make those remaining days as positive for himself as possible,” the authors write. “Rather than having ‘nothing to lose,’ the CP inmate may pragmatically recognize he has more at stake in each day and thus more to gain or lose by his conduct.”

A Review on Time Perception of Death Row Inmates’ Denials in Their Last Statements in the Context of Forensic Linguistics: The Sample of Texas Huntsville Unit Uysal, Basak. Journal of Death and Dying , 2018.

This study examines the last statements of 537 death row inmates executed in Texas between 1982 and 2016. A key takeaway: Seventy inmates used their final words to deny they committed the crimes with which they’d been convicted while 108 chose not to say or write anything at all. “The main topics reflected by the denier offenders are defense, love, wishing, and sadness, and the topics reflected less are atonement, forgiveness, and ending,” the author writes.

Those who gave last statements used 102 words, on average. Inmates who denied their crimes used an average of 138 words. The shortest statement is one sentence while the longest comprises 134 sentences. The most educated inmates “talk less and use fewer words.”

The Functional Use of Religion When Faced with Imminent Death: An Analysis of Death Row Inmates’ Last Statements Smith, Ryan A. The Sociological Quarterly , 2018.

This analysis of death row inmates’ final statements focuses on the use of religious words and phrases. This researcher also examined the last words of the 537 death row inmates sentenced to die in Texas between 1982 and 2016. Of the 429 inmates who gave oral last statements, more than 6 out of 10 expressed themselves using religious sentiments, which “challenge the stereotyped image of the hardened, unrepentant death row inmate,” the author writes.

The author states that the study “deepens our understanding of the manner in which death row inmates use religion to cope with imminent death.” But he also points out that some people may question the authenticity of their final words, which are “solicited under artificial circumstances because statements are made moments before execution when the inmate is strapped to a gurney in front of witnesses.”

Of note: Inmates’ final statements became more religious after 1996, when Texas began allowing victims’ families and close friends to witness executions and hear last statements.

Forgiveness, Spirituality and Love: Thematic Analysis of Last Statements from Death Row, Texas (2002–17) Foley, S.R.; Kelly, B.D. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine , 2018.

For this study, researchers examined the final statements of the 70 inmates executed in Texas between 2011 and 2017, 61 of whom gave oral last statements. All Hispanic inmates made last statements, compared with 92% of black inmates and 70.8% of white inmates. On average, prisoners had less than 10 years of education and their median age was 40.5 years.

The most common theme in statements was love followed by spirituality, the researchers find. Third most common was an apology to the victim’s family, which was included in 30% of statements. Meanwhile, 16% of prisoners apologized to their own families, 11% asked for forgiveness and 10% denied committing the offense for which they were executed. Nobody quoted poetry or literature, the researchers note.

Less than half as many inmates asked for forgiveness in their final statements as had done so in earlier years. Between 2002 and 2006, according to the study, 32% of prisoners asked for forgiveness before their execution. Between 2006 and 2011, 25% did.

Looking for more research on prison inmates? Check out our collection of government reports and academic papers that help paint a picture of the men, women and children who are in custody nationwide. We’ve also summarized research that looks at private prisons , which inmates get the most visitors and whether more educated adults receive shorter prison sentences .

About The Author

Denise-Marie Ordway

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

student opinion

Should the Death Penalty Be Abolished?

In its last six months, the United States government has put 13 prisoners to death. Do you think capital punishment should end?

By Nicole Daniels

Students in U.S. high schools can get free digital access to The New York Times until Sept. 1, 2021.

In July, the United States carried out its first federal execution in 17 years. Since then, the Trump administration has executed 13 inmates, more than three times as many as the federal government had in the previous six decades.

The death penalty has been abolished in 22 states and 106 countries, yet it is still legal at the federal level in the United States. Does your state or country allow the death penalty?

Do you believe governments should be allowed to execute people who have been convicted of crimes? Is it ever justified, such as for the most heinous crimes? Or are you universally opposed to capital punishment?

In “ ‘Expedited Spree of Executions’ Faced Little Supreme Court Scrutiny ,” Adam Liptak writes about the recent federal executions:

In 2015, a few months before he died, Justice Antonin Scalia said he w o uld not be surprised if the Supreme Court did away with the death penalty. These days, after President Trump’s appointment of three justices, liberal members of the court have lost all hope of abolishing capital punishment. In the face of an extraordinary run of federal executions over the past six months, they have been left to wonder whether the court is prepared to play any role in capital cases beyond hastening executions. Until July, there had been no federal executions in 17 years . Since then, the Trump administration has executed 13 inmates, more than three times as many as the federal government had put to death in the previous six decades.

The article goes on to explain that Justice Stephen G. Breyer issued a dissent on Friday as the Supreme Court cleared the way for the last execution of the Trump era, complaining that it had not sufficiently resolved legal questions that inmates had asked. The article continues:

If Justice Breyer sounded rueful, it was because he had just a few years ago held out hope that the court would reconsider the constitutionality of capital punishment. He had set out his arguments in a major dissent in 2015 , one that must have been on Justice Scalia’s mind when he made his comments a few months later. Justice Breyer wrote in that 46-page dissent that he considered it “highly likely that the death penalty violates the Eighth Amendment,” which bars cruel and unusual punishments. He said that death row exonerations were frequent, that death sentences were imposed arbitrarily and that the capital justice system was marred by racial discrimination. Justice Breyer added that there was little reason to think that the death penalty deterred crime and that long delays between sentences and executions might themselves violate the Eighth Amendment. Most of the country did not use the death penalty, he said, and the United States was an international outlier in embracing it. Justice Ginsburg, who died in September, had joined the dissent. The two other liberals — Justices Sotomayor and Elena Kagan — were undoubtedly sympathetic. And Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, who held the decisive vote in many closely divided cases until his retirement in 2018, had written the majority opinions in several 5-to-4 decisions that imposed limits on the death penalty, including ones barring the execution of juvenile offenders and people convicted of crimes other than murder .

In the July Opinion essay “ The Death Penalty Can Ensure ‘Justice Is Being Done,’ ” Jeffrey A. Rosen, then acting deputy attorney general, makes a legal case for capital punishment:

The death penalty is a difficult issue for many Americans on moral, religious and policy grounds. But as a legal issue, it is straightforward. The United States Constitution expressly contemplates “capital” crimes, and Congress has authorized the death penalty for serious federal offenses since President George Washington signed the Crimes Act of 1790. The American people have repeatedly ratified that decision, including through the Federal Death Penalty Act of 1994 signed by President Bill Clinton, the federal execution of Timothy McVeigh under President George W. Bush and the decision by President Barack Obama’s Justice Department to seek the death penalty against the Boston Marathon bomber and Dylann Roof.

Students, read the entire article , then tell us:

Do you support the use of capital punishment? Or do you think it should be abolished? Why?

Do you think the death penalty serves a necessary purpose, like deterring crime, providing relief for victims’ families or imparting justice? Or is capital punishment “cruel and unusual” and therefore prohibited by the Constitution? Is it morally wrong?

Are there alternatives to the death penalty that you think would be more appropriate? For example, is life in prison without the possibility of parole a sufficient sentence? Or is that still too harsh? What about restorative justice , an approach that “considers harm done and strives for agreement from all concerned — the victims, the offender and the community — on making amends”? What other ideas do you have?

Vast racial disparities in the administration of the death penalty have been found. For example, Black people are overrepresented on death row, and a recent study found that “defendants convicted of killing white victims were executed at a rate 17 times greater than those convicted of killing Black victims.” Does this information change or reinforce your opinion of capital punishment? How so?

The Federal Death Penalty Act prohibits the government from executing an inmate who is mentally disabled; however, in the recent executions of Corey Johnson , Alfred Bourgeois and Lisa Montgomery , their defense teams, families and others argued that they had intellectual disabilities. What role do you think disability or trauma history should play in how someone is punished, or rehabilitated, after committing a crime?

How concerned should we be about wrongfully convicted people being executed? The Innocence Project has proved the innocence of 18 people on death row who were exonerated by DNA testing. Do you have worries about the fair application of the death penalty, or about the possibility of the criminal justice system executing an innocent person?

About Student Opinion

• Find all of our Student Opinion questions in this column . • Have an idea for a Student Opinion question? Tell us about it . • Learn more about how to use our free daily writing prompts for remote learning .

Students 13 and older in the United States and the United Kingdom, and 16 and older elsewhere, are invited to comment. All comments are moderated by the Learning Network staff, but please keep in mind that once your comment is accepted, it will be made public.

Nicole Daniels joined The Learning Network as a staff editor in 2019 after working in museum education, curriculum writing and bilingual education. More about Nicole Daniels

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Corrections

- Crime, Media, and Popular Culture

- Criminal Behavior

- Criminological Theory

- Critical Criminology

- Geography of Crime

- International Crime

- Juvenile Justice

- Prevention/Public Policy

- Race, Ethnicity, and Crime

- Research Methods

- Victimology/Criminal Victimization

- White Collar Crime

- Women, Crime, and Justice

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Capital punishment, closure, and media.

- Jody Madeira Jody Madeira Maurer School of Law, Indiana University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.20

- Published online: 22 November 2016

In contemporary society, “closure” refers to “end to a traumatic event or an emotional process” (Berns, 2011, pp. 18–19)—and, in the more specific context of capital punishment, controversy over what, if anything, is needed for murder victims’ families to attain healing and finality or move forward with their lives, including the execution of their loved one’s killer. The term is highly politicized, and is used by both death penalty advocates and its opponents to build arguments in favor of their respective positions. Closure has been indelibly linked to both capital punishment and media institutions since the late 1990s and early 2000s. The media’s penchant for covering emotional events and its role in informing the American public and recording newsworthy events make it perfectly suited to construct, publicize, and reinforce capital punishment’s alleged therapeutic consequences. Legal and political officials also reinforce the supposed link between closure and capital punishment, asking jurors to sentence offenders to death or upholding death sentences to provide victims’ families with a chance to heal. Such assertions are also closely related to beliefs that a particular offender is defiant or lacks remorse. Surprisingly, however, the association between closure and capital punishment has only recently been subjected to empirical scrutiny. Researchers have found that victims’ families deem closure a myth and often find executions themselves unsatisfying, provided that a perpetrator does not enjoy high media visibility so that the execution has a silencing effect, as did Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh’s execution by lethal injection in 2001. Recent empirical examinations of the link between capital punishment and closure prompt a redefinition of closure through which victims’ family members learn to cope with, work through, and tell the story of a murder and its impact. This redefinition is less sensational and thus perhaps less newsworthy, which may have the salubrious effect of discouraging extensive media emphasis on executions’ closure potential. Another way to decouple closure from capital punishment is for media organizations to change their practices of covering perpetrators, such as by not continually showing images of the perpetrator and by incorporating a more extensive focus on the victims and their families. While government officials have called for the media to exercise restraint in the wake of such events as the Oklahoma City bombing and 9/11, victims’ groups are now beginning to advocate for this same goal, with much success.

- capital punishment

- death penalty

The identification of closure with capital punishment is a fairly recent development, given the centuries-long history of the death penalty in the United States. As Armour and Umbreit ( 2012 ) observe, “although small in number, capital murder cases consume the attention of the public through mass media” (p. 4). Here, the term “media” is used to refer to the “main means of mass communication (esp. television, radio, newspapers, and the Internet) regarded collectively” (Media, n.d. ), including both those organizations that cover news and those focused on other forms of entertainment. The controversial coupling of closure with capital punishment (Armour & Umbreit, 2006 ) stems from both mass media coverage and criminal justice system practice, as prosecutors argue to juries that family members can gain closure from the execution of their loved ones’ killer, or that executions heal social or communal wounds (Meade, 1996 , pp. 743–744; Bandes, 2004 , pp. 592–595). Media institutions in particular have assumed a bullhorn role in broadcasting the association between capital punishment and closure, publicly articulating, circulating, and ultimately reinforcing this link. Although this oversimplifies the media’s role in the popular construction of the closure phenomenon, there is little doubt that the media has been instrumental. Death penalty researcher Frank Zimring reported that, before 1989 , closure was never mentioned by the media in conjunction with capital punishment; in 1989 , the two were mentioned in the same context only once (Zimring, 2003 , p. 60). Beginning in 1993 , however, the frequency with which closure was mentioned in the context of capital punishment grew with exponential frequency to 500 mentions in 2001 , when an ABC News/ Washington Post poll found that 60% of respondents strongly or moderately agreed with the statement that the death penalty was fair because it gave closure to murder victims’ family members (Zimring, 2003 , p. 60).

The Politicization of “Closure” Rhetoric

Closure concerns can appear in diverse social and cultural contexts, from adoption, personal injury, and death care to divorce, forensics, and memorialization (Berns, 2011 ). Closure concerns became highly visible in popular culture during the 1990s; Berns attributes this to “victims’ social movements; a rise in therapeutic language and goals; court decisions; and our cultural expectations for happy, inspiring, and quick resolutions” (Berns, 2011 , p. 8). Most scholarship addressing closure, however, has focused on its use as a justification for capital punishment (Kanwar, 2002 , p. 216). Scholars have observed that closure can be achieved through other means, including forgiveness, mercy, and alternative sentences such as life in prison without the possibility of parole. Kanwar and others have linked closure to the victims’ rights movement, making it increasingly “victim-centered”: “In political discourse, ‘closure’ is somehow presented as a rational and dispassionate matter of political concern, emptied of its emotional underpinnings and distanced from the viscerality of ‘satisfaction’” (Kanwar, 2002 , pp. 217, 222–237). Berns notes, “politicians and advocates use closure to talk about grief, victimization, justice, and healing” (Berns, 2011 , p. 118).

Both opponents and supporters of the death penalty have taken stances on the propriety of closure in connection with execution, from abolitionist organizations such as Murder Victims Families for Reconciliation to advocate organizations such as the National Organization of Parents of Murdered Children—but, in doing so, both stances have embraced and thus helped to legitimate the concept (Kanwar, 2002 , p. 249). On the one hand, those who disagree that capital punishment effects closure observe that legal proceedings are ill equipped to resolve grief and other emotions, focused as they are adjudicating guilt and allocating punishment (Kanwar, 2002 , pp. 241–242). Indeed, they argue, such contexts are more likely to exploit family members than to heal them, or at the very least produce many contradictory emotional responses (Kanwar, 2002 , pp. 242, 243). They also point to the possibilities of attaining closure through mercy and even forgiveness rather than vengeance, and to the fact that some victims who witness executions still feel hurt and anger, now compounded by disappointment and disillusionment (Berns, 2011 , p. 127; Goodwin, 1997 , p. 585). For example, numerous victims have attempted to decouple execution from closure expectations through “Not in My Name” movements that openly expose their refusal to allow states to use their stories to justify executions (King, 2003 ). On the other hand, supporters who believe capital punishment facilitates closure point not only to the recently extended “rights” to give victim impact evidence in capital sentencing proceedings and at times to witness executions, but also to individual family members’ public remarks preceding or following the execution of their loved ones’ killer that often emphasize relief and satisfaction. Much of the politicization of closure rhetoric has occurred through various forms of media, from news coverage of executions to interviews with victims’ families to online blogs and social media posts. The following, however, will focus not on the broader relationship between capital punishment and closure but on the media’s role in this relationship. More specifically, how do media representations of closure, perpetrators, and punishment reinforce the link between closure and capital punishment, and how have these representations affected victims’ families’ lived experience in the aftermath of mass murder and terrorism?

The Media Spotlight on Closure and Capital Punishment

As a phenomenon that is highly media-driven, closure illustrates how journalism can respond to traumatic events that seem to evade human understanding through facilitating the use of “simple narrative formats” (Sreberny, 2002 , p. 221). Thus, murders that trigger death sentences and closure claims may also in our “excessively mediated culture … encourage a kind of simulacrum of emotion and a form of affective manipulation by the culture industries”—which include the media (Sreberny, 2002 , p. 221). Media researchers such as Elayne Rapping have focused on television talk shows and their adoption of “a depoliticized, over-individualized approach to social problems,” an oversaturation of feelings (Rapping, 1994 ; Sreberny, 2002 , p. 221). Rapping explains that “television drama depends foremost on closure,” and argues this medium cultivated “an audience of viewer-citizens who were increasingly demanding a particular kind of closure: the conviction and punishment of the evil offender” (Rapping, 2003 , p. 10). This of course feeds into the current “soundbite culture,” characterized by “the rise of the image and the decline of the word,” facilitating superficial coverage instead of reasoned exchange (Slayden & Whillock, 1999 , pp. ix–x). It is especially ironic, then, that the US Supreme Court allowed cameras—the tools of an allegedly oversentimental medium—into criminal courtrooms to demonstrate the impartiality and efficacy of the criminal justice system, to “allay the fears … that the criminal justice system wasn’t ‘working,’ that it was too ‘soft on crime’ and that criminals were increasingly being allowed to go free” (Rapping, 2003 , p. 241). According to law professor Susan Bandes, the “law and media exist in a complex feedback loop,” with television, and perhaps now the Internet, “becom[ing] our culture’s principal storyteller, educator, and shaper of the popular imagination” (Bandes, 2004 , p. 585). Death-eligible crimes are highly newsworthy, in particular the “horse race” of the trial and the “minutiae of the execution” that mark those events as distinct (Bandes, 2004 , p. 587).

The media can effectively and consistently reinforce the association between closure and capital punishment because it plays key roles not only in broadcasting but in preserving historical perceptions and images, constructing American consciousness and contributing indelibly to American collective memory. Media focus our attention in both contemporary and historical ways. To these ends, Sontag ( 2003 ) has observed there is a common assumption that “public attention is steered by the attentions of the media—which means, most decisively, images,” highlighting “the determining influence of photographs in shaping what catastrophes and crises we pay attention to, what we care about, and ultimately what evaluations are attached to these conflicts” (p. 105).

But focusing Americans’ attention on some issues rather than others and prompting us to consider these issues in particular ways are processes that also carry normative and moral implications—what should citizens be looking at, and how ? Thus, the intersection between capital punishment, closure, and media also entails a debate over how American citizens and institutions should regard, react to, and reproduce images of and information about criminal perpetrators. Looking at perpetrators may feel somehow inappropriate in ways that gazing at images of their victims and rescuers does not, and may even approach a breach of moral propriety. Citizens become familiar with victims’ names to protest the anonymity of their deaths and to celebrate their humanity. But there can be less salubrious motives to learn about perpetrators, ranging from morbid curiosity to worshipful fascination. As Sontag ( 2003 ) eloquently noted in Regarding the Pain of Others , “[t]here is the satisfaction of being able to look at the image without flinching. There is the pleasure of flinching” (p. 41). Mitigating this visceral experience, however, is an awareness that preventing future violent acts may entail learning more, not less, about those who instigate them.

Closure’s popular appeal centers upon the cultural figure of the crime victim that has long maintained a hold upon the American public imagination. Contemporary interest in victims, their family members, and closure pursuits is often thought to be a reaction to the focus on criminal defendants and their rights that marked the “Warren Court” era of the US Supreme Court from 1953 to 1969 (Madeira, 2012 , p. 89). The ensuing crime victims’ rights movement casts crimes as transactions for which perpetrators must pay what they owe to both society and their victim(s) by serving their sentences and perhaps providing criminal restitution (Cole, 2007 , p. 35; Madeira, 2012 , p. 39). Prosecutors use victims and their family members largely as moral anchors that demand attention to the perpetrator’s infringement upon victims’ autonomy and dignity (Boutellier, 2000 , pp. 45–46). Significantly, in popular culture, closure needs are only attributed to victims’ families and sometimes rescuers, not the perpetrators’ family members.

Victims gained enhanced visibility in legal proceedings in 1991 when the US Supreme Court ruled in Payne v. Tennessee (505 U.S. 808, 825 ( 1991 )) that murder victims’ family members could deliver victim impact testimony at sentencing, extending new participative opportunities and symbolizing a legal focus on more therapeutic ends (Bandes, 2009 ). Thus, closure acquired a wide variety of dimensions; it became a procedural goal to give family members finality, an entitlement for victims’ families to a timely trial and punishment, and a therapeutic aspiration ensuring the inclusion of victims’ perspectives (Madeira, 2012 , p. 40). The media was ready to help to convey these conceptions of closure to a wider audience through such events as the televised trial of O. J. Simpson that captivated audiences, sowing the seeds for cultural connections between courtrooms, therapy, and victims. Richard Sherwin ( 2000 ) has described how such affairs may provide “hyper-catharsis,” “a spectacle that masks rather than reveals unconscious impulses and the fantasies they produce” and “exploits images—of victims and aggressors alike—for the sake of their emotional payoff” (p. 166).

Crucially, the media’s relationship with capital punishment and closure has always been at most indirect, surfacing in quotes or statements from journalists, government officials, attorneys, and victims’ families (Gross & Matheson, 2003 ; Vollum & Longmire, 2007 ). Family members interviewed in the news media often claim to experience closure from trials and executions—but that is the closest the media has come to investigating closure effects (Armour & Umbreit, 2006 ). American courts have vigorously resisted all attempts to broadcast executions, in large part because the execution image is thought to have a disruptive and disturbing potential, implicating both the inmate’s privacy and participants’ safety. The federal government, for example, prohibits photographic, audio, and visual recording devices at federal executions in 28 C.F.R. § 26.4(f). In cases addressing the media’s right to film an execution, judges have disputed the danger of the execution image, variously finding that it possesses no special qualities (Garrett vs. Estelle, 556 F.2d 1274, 1278 (C.A. Tex 1977 )) and that it is “qualitatively different from a mere verbal report about an execution” (Halquist vs. Department of Corrections, 732 P.2d 1065, 1067 (Wash. 1989 )). Oft-cited reasons for a ban on execution broadcasts are that such coverage would breach participating officials’ and inmates’ privacy, jeopardize security in the execution chamber, destroy execution solemnity, and introduce novel questions such as whether camera placement would disrupt execution routines (KQED vs. Vasquez, 1991 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 21163, p. 8 ( June 7, 1991 ); Entertainment Network vs. Lappin, 134 F. Supp. 2d 1002, 1018 (S.D. Ind. 2001 )). One court even proposed a “suicidal cameraman theory,” claiming a need to protect attendees from “heavy objects of any sort” such as news cameras that, if thrown in the witness room, might strike and break the window separating the witness room from the gas chamber (KQED vs. Vasquez, 1991 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 21163, p. 8 ( June 7, 1991 )).

A Case Study: The Oklahoma City Bombing

Extended empirical assessments of the relationship between capital punishment and closure can allow researchers to examine how particular murder victims’ family members experienced the relationship between capital punishment and closure. The 1995 Oklahoma City bombing offers an effective case study, since it had been the largest terrorist attack on American soil prior to 9/11; all legal proceedings are completed; and perpetrators Timothy McVeigh, Terry Nichols, and Michael Fortier all had differing levels of involvement and received wildly disparate sentences. Timothy McVeigh constructed and ignited a Ryder truck bomb outside the Murrah Federal Building on April 19, 1995 , and was executed on June 11, 2001 , in front of an unprecedented 242 individuals. His accomplice, Terry Nichols, had played a formative role in financing the project and constructing the truck bomb and is serving several life sentences in a federal Supermax penitentiary in Florence, Colorado. Michael Fortier, McVeigh’s former Army roommate who had known about the plans to construct the bomb, accepted a plea bargain and was sentenced to twelve years in prison, serving ten and a half years before being released early for good behavior and joining the federal Witness Protection Program.

Interviews with survivors and family members of the Oklahoma City bombing revealed that many spoke of McVeigh not as a perpetrator whom they had never met but as an involuntary presence in their lives who was forced upon them through an overbearing and seemingly ceaseless media presence. After McVeigh’s lawyer, Stephen Jones, allowed him to meet several journalists in an effort to find one who could write an effectively humanizing article (Madeira, 2012 , pp. 114, 204–205), McVeigh stayed in touch with several whom he had met until his execution in 2001 . There is no question that McVeigh became a media personality. Among his most noteworthy media appearances was the heavy media coverage and recirculation of images from his perpwalk, including his appearance in 1995 on the front cover of Time magazine, an Emmy award winning 60 Minutes death row interview by Ed Bradley in 2000 , and his collaboration on an authorized biography, American Terrorist: Timothy McVeigh and the Oklahoma City Bombing , authored by journalists Dan Herbeck and Lou Michel, that was published in April 2001 , shortly before his execution. Moreover, Attorney General John Ashcroft’s unprecedented decision to allow his execution in Terre Haute, Indiana, to be broadcast back to Oklahoma City via closed-circuit television ensured that he would be a leading media topic until his death was a fait accompli. As Bruce Shapiro noted on Salon.com , McVeigh’s closed-circuit execution broadcast ensured that “the press and pundits are talking about how big the crowd will be that gets to watch McVeigh … McVeigh is able to keep himself on the front page” (Shapiro, 2001 ).

Referencing media researchers Horton and Wohl’s concept of parasocial relationship, where media personalities such as sitcom characters or evening news anchors can come to feel like positive and familiar presences in a viewer’s social circle, it is possible that McVeigh had become a negative parasocial presence for survivors and family members, particularly those living in Oklahoma City, at the heart of the media maelstrom (Madeira, 2012 , p. 14). Several survivors and family members spoke of a need to execute McVeigh to “silence” him as well as to hold him accountable for his role in the bombing (Madeira, 2012 , p. 245). While many wanted Terry Nichols executed as well for his role in the bombing, their reasons for doing so did not have to do with silencing him, for he had remained quiet and out of the media limelight since his arrest. As family member Paul Howell stated,

McVeigh, even though he knew that he was getting the death sentence, he was defiant all the way up to the point where it actually happened, okay? He would speak out to the media. He would tell the families to grow up; it’s collateral damage that we killed your kids, you know. And everything that he did was doing nothing but hurting the family members here in Oklahoma. So the only way for us to have any kind of peace was to execute this man. Now on Nichols, Nichols is a little different because since he’s been tried and convicted, you don’t hear about him … I can live with him being in prison for the rest of his life, for the simple reason that he is not defiant and he’s not going out and getting on the news and so forth and trying to hurt the family members. (Madeira, 2012 , p. 246)

McVeigh was indeed aware that a handful of survivors and family members were very actively engaged in giving media interviews, and was determined to use his media access in turn to counter these voices, arguing that the bombing was justified as an act of war in retaliation for the United States government’s actions at Waco and Ruby Ridge (Madeira, 2012 , pp. 201–220).

Closure is not a popular term with most survivors and family members, and those in Oklahoma City were no exception. They almost unanimously denied that closure existed, lamenting the impossibility of finality or “getting over it” and speaking instead of the possibility of adjusting or “moving on” (Madeira, 2012 , pp. 41–45). Several termed closure a “media word” or “buzz term” (Madeira, 2012 , p. 42), and connected it to unrealistic expectations that those exposed to such trauma could rebound to “normal” within a matter of months—or indeed, unrealistic expectations that there was even a “normal” to which they could return (Madeira, 2012 , 41–45).

These findings prompt a redefinition of closure that considers the overlapping roles of both media institutions and capital legal proceedings. In contemporary media usage, closure most often refers to a state of being (“reaching closure”); in reality, however, it is “an interactive process by which individual family members and survivors construct meaningful narratives of the bombing and its impact upon their lives, and how they have moved on, dealt with, adjusted to, or healed from this culturally traumatic event” (Madeira, 2012 , pp. xxii–xxiv). This definition casts closure as a process comprising both intra personal and inter personal cycles. Closure requires both reflective behaviors of comprehension and self-adjustment, and more active interventions, from learning how to tell the story of a traumatic event to intervening to prevent other future events (Madeira, 2012 , pp. 50–53). Interventions might include participating in media interviews, helping to build the Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum, attending the trial and/or execution, or working toward legal reforms (Madeira, 2012 , p. 53). Instead of effecting a “closing,” then, closure is concerned with creating an opening—an expansion of awareness and engagement and a readiness to reencounter social relationships and roles.

Changes in media practices also affected survivors’ and family members’ attempts to work through their grief and cope with McVeigh’s visibility. Many journalists and reporters in Oklahoma City demonstrated a sensitivity to how their communications with McVeigh would impact survivors and family members, and sometimes modified journalistic practice so as to minimize surprise and harm. For example, Terri Watkins, a reporter for KOCO-TV in Oklahoma, would meet with interested survivors and family members after she received a letter from McVeigh, but before she broadcast its contents (Madeira, 2012 , p. 206). Many were actually quite interested in what McVeigh had to say, but did not relish learning about these matters from watching television. In this fashion, McVeigh’s communications became more educational than sensationalist or profiteering, as they revealed a glimpse into the mind of this young man who had committed such a heinous act.

But the relationship between capital punishment, closure, and the media is scarcely straightforward; the Oklahoma City bombing case study illustrates two compelling paradoxes that problematize the assumption that the news media coverage always supports a link between closure and capital punishment, or that all coverage of a perpetrator is traumatic to and undesired by victims’ family members and survivors.

The same news media organizations that popularize the coupling between closure and capital punishment can undermine this connection by helping to convey how victims’ families found witnessing an execution a less than satisfactory experience. For example, one news story addressing the question of whether executions provided closure quoted a victim’s son as stating that the execution was “anticlimactic” and the perpetrator’s death was “very easy and peaceful,” perhaps making him angrier (Montgomery, 2009 ). Another victim’s son stated, “It didn’t bring my brother back. It didn’t do nothing” (Montgomery, 2009 ). Witnesses to McVeigh’s execution also found the ease of his death disappointing; as one closed-circuit witness recalled, “I just thought it’d take a long time … It took me longer to get out of the restroom [beforehand] than it took for him to die” (Madeira, 2012 , p. 251). Another closed-circuit witness lamented, “I don’t think it was gruesome enough. I think it should have been more painful … He just went to sleep. That’s the easy way out” (Madeira, 2012 , p. 254). Denied a satisfying visual experience, witnesses must find solace instead in the fact that the death sentence has been carried out, and the process is complete.

Moreover, if Oklahoma City family members and survivors faulted the media for its seemingly ceaseless coverage of the perpetrators that often hampered their ability to heal, they also acknowledged that the media played a formative role in providing important information such as investigational and trial updates and details about the perpetrators’ upbringings and family lives. McVeigh’s father, Bill, in particular attracted much sympathy from family members and survivors; in contrast, Nichols’s brother attracted much more negative attention as family members and survivors felt that he was using the media to popularize his anti-governmental views (Madeira, 2012 , p. 111). A television interview with Bill McVeigh even led family member Bud Welch to perhaps his greatest moment of personal peace; Welch ultimately met with Bill and McVeigh’s sister Jennifer at their home in upstate New York, when Bud was able to tell them that the two men were living the same pain, that Bud cared how they felt, and did not blame them for Timothy McVeigh’s actions (Madeira, 2012 , pp. 111–112).

Other Illustrative Cases

The Oklahoma City bombing stands out in American history as a rather extreme example of the traumatic potential of a criminal perpetrator’s presence. However, other criminal perpetrators have also had a comparably toxic media presence, with traumatizing effects to victims’ family members. Daniel Rolling, the so-called Gainesville Ripper, maintained a particularly infamous media presence with similar consequences for the families of his victims. Rolling, a serial killer, murdered five University of Florida Students in Gainesville in 1990 , mutilating their bodies. When he was prosecuted for these crimes nearly four years later, Rolling claimed to want to be a criminal “superstar” (Associated Press, “Florida Executes Serial Killer,” 2006 ) like Ted Bundy and pled guilty to all charges; he was subsequently sentenced to death on each count. At trial, he sang gospel songs while he was sentenced (Fisher, 2006 ). He later collaborated with Sondra London on a book entitled The Making of a Serial Killer: The Real Story of the Gainesville Murders in the Killer’s Own Words (London, 1996 ). Rolling also gave London, who eventually became his fiancée, exclusive rights to any interviews and written material, and also asked her to market the many letters, songs and poems, and pictures he produced while on death row in Florida (Writer to marry Rolling, 1993 ). Like McVeigh, Rolling also wrote letters to news media organizations (Associated Press, “Serial Killer Danny Rolling Executed,” 2006 ). Following the execution, during which Rolling sang a gospel hymn, Chief Assistant State Attorney Jeanne Singer remarked that “it looked like a final stage performance” (Fisher, 2006 ).

The mass media may also exhibit what Susan Bandes terms “selective empathy”—disproportionately covering extremely sympathetic perpetrators, such as Karla Faye Tucker, who was executed in 1998 (Bandes, 2004 , p. 593). The first woman Texas had executed since the Civil War, Tucker had been sentenced to death for murdering two people in 1983 with a 3-foot pickax while engaging in a weekend-long party that included drug use (Grumman, 1998 ; Kudlac, 2007 ). After she was sentenced to death, news coverage chronicled her history of prostitution and drug abuse and the fact that she had become a fervent Christian and obtained her GED, even marrying her prison minister, Dana Brown (“Karla Faye Tucker’s Last Hours,” 1998 ). Again, coverage of Tucker’s impending execution became headline news. Larry King conducted an Emmy award-winning interview with Tucker approximately one month before her execution (King, 2007 ). She was on the cover of People Magazine , was a guest on Pat Roberson’s 700 Club , and Pope John Paul II sent her a letter of support (Kudlac, 2007 , p. 73). Yet, this omnipresent media coverage had not worn well with the family members of her victims; Richard Thornton, the husband of one of her victims, stated that “She finally said my wife’s name. It took her 14½ years to do it. We’ll begin tomorrow without the name Karla Faye Tucker stuck in our face every day” (Grumman, 1998 ).

If capital punishment is thought more likely to bring closure in cases where offenders appear disrespectful, defiant, and unrepentant, the news media is undoubtedly the chief means of publicizing these qualities, as well as others that can influence public opinion about whether executing a given offender will bring closure. Following the trial of Scott Peterson, charged and convicted of the murder of his wife, Lacie, and her unborn son, Connor, the media was saturated with references to Peterson’s conduct during trial, where he sat “defiantly still and tight-jawed” (Vries, 2004 ), and with jurors’ assertions that this lack of emotion was what finally pushed them toward a death sentence—particularly after he did not testify at trial (Vries, 2004 ). One juror interviewed on CBS News’s The Early Show stated that Peterson “is a cold blooded killer. He has no remorse” (Vries, 2004 ).

State Studies on Monetary Costs

- Facebook Share

- Tweet Tweet

- Email Email

Ohio AG Capital Crimes Annual Report (2022) cites the Ohio Legislative Service Commission’s statement that” “A mix of quantitative and qualitative studies of other states have found that the cost of a case in which a death penalty has been sought and imposed is higher, perhaps significantly so, than a murder case in which life imprisonment has been imposed.” These studies generally support the conclusion that the total amount expended in a capital case is between two and a half and five times as much as a noncapital case. The AG Report concludes that if these estimates apply to Ohio, then the extra cost of imposing the death penalty on the 128 inmates currently on death row might range between $128 million to $384 million.

A 2017 independent study—An Analysis of the Economic Costs of Capital Punishment in Oklahoma—estimated that an Oklahoma capital case cost $110,000 more on average than a non-capital case. 1

The study , prepared for the Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission researched the costs of seeking and imposing the death penalty in Oklahoma, and found that seeking the death penalty in Oklahoma “incurs significantly more time, effort, and costs on average, as compared to when the death penalty is not sought in first degree murder cases.” The study determined that Oklahoma capital cases cost 3.2 times more than non-capital cases on average. Reviewing 15 state studies of death-penalty costs conducted between 2000 and 2016, the study found that, across the country, seeking the death penalty imposes an average of approximately $700,000 more in costs than not seeking death. The researchers wrote that “all of these studies have found … that seeking and imposing the death penalty is more expensive than not seeking it.” The Oklahoma study also reviewed 184 first-degree murder cases from Oklahoma and Tulsa counties in the years 2004-2010 and analyzed costs incurred at the pre-trial, trial, sentencing, and post-sentencing (appeals and incarceration) stages. Oklahoma capital appeal proceedings cost between five-and-six times more than non-capital appeals of first-degree murder convictions. The researchers said their results were “consistent with all previous research on death-penalty costs, which have found that in comparing similar cases, seeking and imposing the death penalty is more expensive than not seeking it.” They concluded: “It is a simple fact that seeking the death penalty is more expensive. There is not one credible study, to our knowledge, that presents evidence to the contrary.”

A 2017 Fiscal Impact Report prepared by the Legislative Finance Committee of the New Mexico legislature estimated that bringing back the death penalty for three types of homicides in the state would cost as much as $7.2 million over the first three years. 2

The report notes that “[b]etween 1979 and 2007 when the death penalty was an option to prosecutors, there were over 200 death penalty cases filed, but only 15 men sentenced to death and only one execution.” The Law Offices of the Public Defender reports that the defense costs for the two New Mexico death-penalty cases that remain in the system following the prospective repeal of the state’s death-penalty statute have been $607, 400 for one case and $1.3 million for the other. The Fiscal Impact Report also contains a survey of costs incurred by a number of other states in administering their death-penalty statutes.

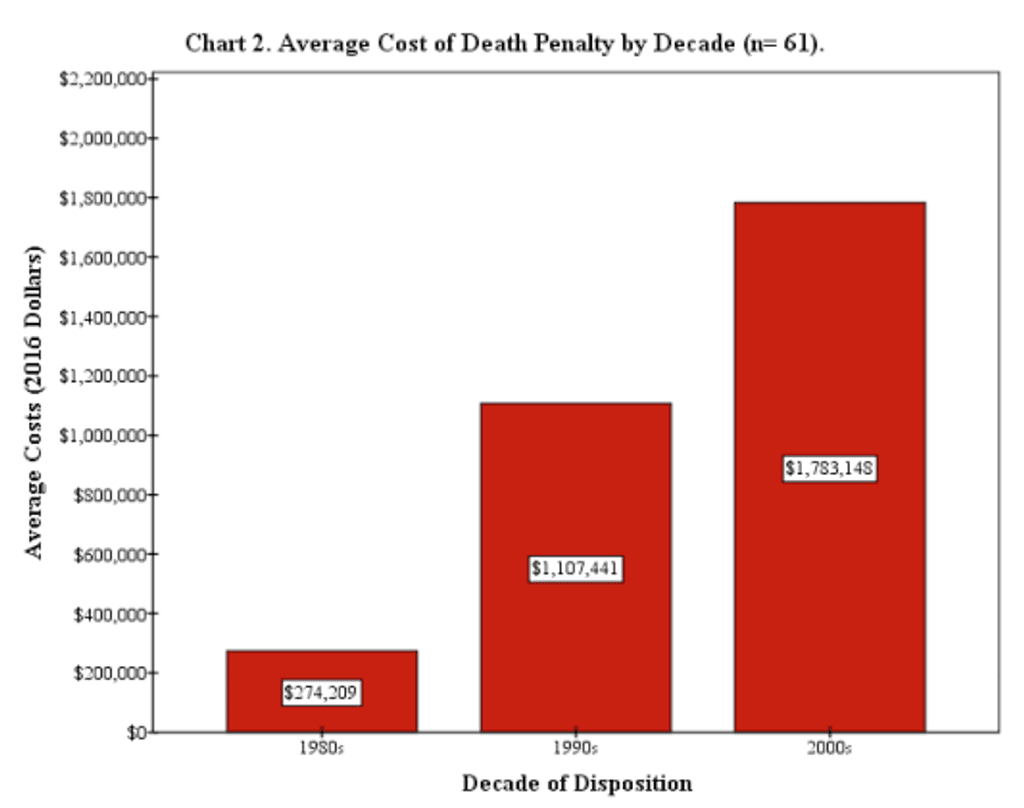

A 2016 study by Lewis & Clark Law School and Seattle University found that 61 death sentences handed down in Oregon cost taxpayers an average of $2.3 million, including incarceration costs, while 313 aggravated murder cases cost an average of $1.4 million. 3

The study , which examined the costs of hundreds of murder and aggravated murder cases in Oregon, concluded that “maintaining the death penalty incurs a significant financial burden on Oregon taxpayers.” The researchers found that the average trial and incarceration costs of an Oregon murder case that results in a death sentence are almost double those in a murder case that results in a sentence of life imprisonment or a term of years. Excluding state prison costs, the study found, cases that result in death sentences may be three-to-four times more expensive. Excluding state prison costs, the difference was even more stark: $1.1 million for death sentences vs. $315,159 for other non-capital cases. The study also found that death-penalty case costs have escalated over time, from $274,209 in the 1980s to $1,783,148 in the 2000s. The study examined cost data from local jails, the Oregon Department of Corrections, the Office of Public Defense Services, and the Department of Justice, each of which provided information on appeals costs. Prosecution costs were not included because the District Attorney’s Office budgets were not broken down by time spent on each case. Among the reasons cited for the higher cost in death-penalty cases were the requirement for appointment of death-qualified defense lawyers, more pre- and post-trial filings by both prosecutors and the defense, lengthier and more complicated jury-selection practices, the two-phase trial, and more extensive appeals once a death sentence had been imposed. Professor Aliza Kaplan, one of the authors of the study, said, “The decision makers, those involved in the criminal justice system, everyone, deserves to know how much we are currently spending on the death penalty, so that when stakeholders, citizens and policy-makers make these decisions, they have as much information as possible to decide what is best for Oregon.” Oregon has carried out only two executions since the death penalty was reinstated, both of prisoners who waived their appeals. The state currently has a moratorium on executions.

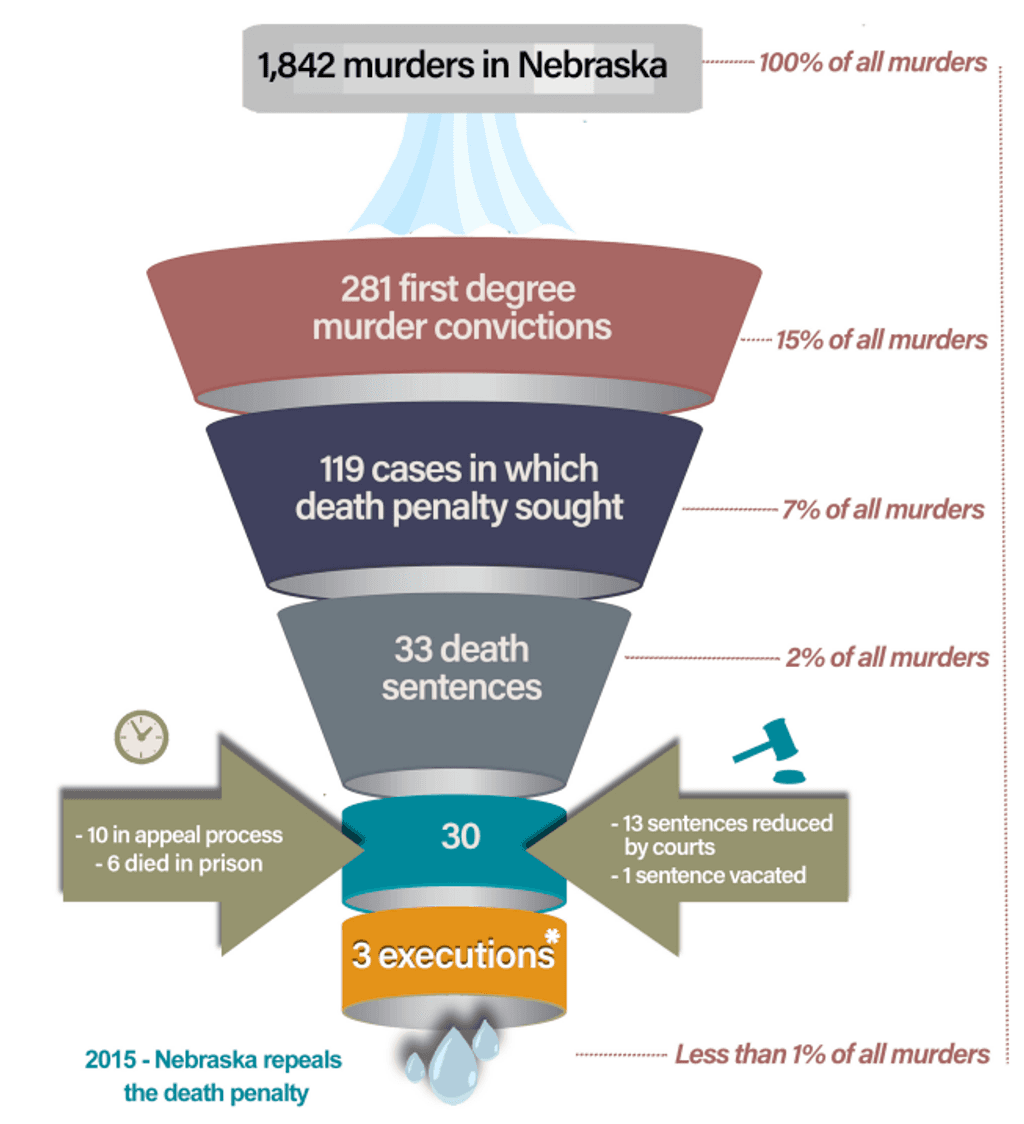

A 2016 study of the costs of Nebraska’s death penalty by Dr. Ernest Goss, a Creighton University economics professor who founded the conservative think tank, Goss & Associates, found that the state spends $14.6 million per year to maintain its capital punishment system. 4

The study “ The Economic Impact of the Death Penalty on the State of Nebraska: A Taxpayer Burden?” estimated that each death-penalty prosecution cost Nebraska’s taxpayers about $1.5 million more than a life-without-parole prosecution. Conducting a meta-analysis of cost studies conducted across the country, Dr. Goss estimated that the death penalty costs states with capital punishment an average of $23.2 million more per year than those with alternative sentencing. The study found that states with the death penalty spend about 3.54% of their overall state budgets on courts, corrections, and other criminal-justice functions associated with the death penalty, while states without the death penalty spend about 2.93% on those functions. 1,842 homicides were committed in Nebraska between 1973 and 2014, with prosecutors seeking death 119 times and obtaining 33 death sentences. Of those sentenced to death, the study found that 13 had their sentences reduced, six died in prison, three were executed, one sentence was vacated, and ten are still appealing their sentences. The study was commissioned by Retain a Just Nebraska, an organization advocating for Nebraskans to vote to retain the Nebraska legislature repeal of the state’s death penalty in the November 2016 election.

Pennsylvania

In a 2016 article, The Reading Eagle used data from a 2008 study by the Urban Institute to show that Pennsylvania has spent an estimated $272 million per execution since the Commonwealth reinstated its death penalty in 1978. 5

According to the article , the Eagle calculated that cost of sentencing 408 people to death was an estimated $816 million higher than the cost of life without parole. The estimate is conservative, the paper says, because it assumes only one capital trial for each defendant and it does not include the cost of cases in which the death penalty was sought but not imposed. An earlier investigation had estimated a cost of at least $350 million, based on the 185 prisoners who were on death row as of 2014, but additional research into the cases that had already been overturned, or in which prisoners died or were executed prior to 2014, revealed a total of 408 people who had been sentenced to death.

Two 2015 state analyses of the costs of the death penalty in Indiana found that “the out-of-pocket expenditures associated with death-penalty cases were significantly more expensive than cases for which prosecuting attorneys requested either life without parole or a term of years.”

The first analysis —prepared by the Legislative Services Agency for the General Assembly on April 13, 2015, as a cost assessment for a bill that would make more cases eligible for the death penalty—found that the average cost of a capital-murder case tried before a jury was $789,581, more than 4.25 times greater than the average cost of a murder case tried to a jury in which the prosecution sought life without parole ($185,422). The analysis also found that a death-penalty case resolved by guilty plea still cost more than 2.33 times as much ($433,702) as a life-without-parole case tried to a jury.

A second analysis —prepared on May 4, 2015, in connection with a bill to add another aggravating circumstance to the state’s death-penalty statute—found that the state share of out-of-pocket expenditures for death-penalty cases tried to a jury ($420,234) was 2.77 times greater than its share of expenditures in life-without-parole case tried to a jury ($151,890). It also found that death-penalty cases tried to a jury costs counties an average of $369,347 in out-of-pocket expenditures, 11 times more than the average county expenditure for a life-without-parole case tried to a jury ($33,532). The assessment found that death-penalty cases resolved by a plea agreement are still significantly more expensive than non-capital cases that go to trial. The $148,513 average expenditure counties paid for capital cases that were resolved by plea was 4.43 times more than their average expenditure for a life-without-parole case tried to a jury.

A 2015 Seattle University study examining the costs of the death penalty in Washington found that each death penalty case cost an average of $1 million more than a similar case where the death penalty was not sought. 6

The study found defense costs were about three times as high in death-penalty cases and prosecution costs were as much as four times higher than for non-death penalty cases. Criminal Justice Professor Peter Collins, the lead author of the study, said, “What this provides is evidence of the costs of death-penalty cases, empirical evidence. We went into it [the study] wanting to remain objective. This is purely about the economics; whether or not it’s worth the investment is up to the public, the voters of Washington and the people we elected.” (Although Washington’s death penalty was reinstated in 1981, the study examined cases from 1997 onwards. Using only cases in the study, the gross bill to taxpayers for the death penalty will be about $120 million. Washington has carried out five executions since reinstatement, implying a cost of $24 million per execution. In three of those five cases, the inmate waived parts of his appeals, thus reducing costs.) The study was not able to include the likely higher yearly incarceration costs for death row inmates versus those not on death row.

In 2014, the Nevada Legislative Auditor estimated the cost of a murder trial in which the death penalty was sought cost $1.03 to $1.3 million, whereas cases without the death penalty cost $775,000. 7

The study , commissioned by the Nevada legislature, found that the average death penalty case costs a half million dollars more than a case in which the death penalty is not sought. The auditor summarized the study’s findings, saying, “Adjudicating death-penalty cases takes more time and resources compared to murder cases where the death-penalty sentence is not pursued as an option. These cases are more costly because there are procedural safeguards in place to ensure the sentence is just and free from error.” The study noted that the extra costs of a death-penalty trial were still incurred even in cases where a jury chose a lesser sentence, with those cases costing $1.2 million. The study was based on a sample of Nevada murder cases and include the costs of incarceration. Because certain court and prosecution costs could not be obtained, the authors said the costs were, “understated,” and may be higher than the estimates given.

A 2014 Kansas Judicial Council study examining 34 potential death-penalty cases from 2004-2011 found that defense costs for death penalty trials averaged $395,762 per case, compared to $98,963 per case when the death penalty was not sought. 8

According to the study , defending a death-penalty case costs about four times as much as defending a case where the death-penalty is not sought. Costs incurred by the trial court showed a similar disparity: $72,530 for cases with the death penalty; $21,554 for those without. Even in cases that ended in a guilty plea and did not go to trial, cases where the death penalty was sought incurred about twice the costs for both defense ($130,595 v. $64,711) and courts ($16,263 v. $7,384), compared to cases where death was not sought. The time spent on death cases was also much higher. Jury trials averaged 40.13 days in cases where the death penalty was being sought, but only 16.79 days when it was not an option. Justices of the Kansas Supreme Court assigned to write opinions estimated they spent 20 times more hours on death-penalty appeals than on non-death appeals. The Department of Corrections said housing prisoners on death row cost more than twice as much per year ($49,380) as for prisoners in the general population ($24,690).

A 2012 study, conducted by Dr. Terance Miethe of the Department of Criminal Justice at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas concluded that the 80 pending capital murder cases in Clark County, Nevada would cost approximately $15 million more than if they were prosecuted without seeking the death penalty. 9

The study showed defense of the average capital murder case in Clark County cost $229,800 for a Public Defender or $287,250 for appointed counsel. The additional cost of capital murder cases was $170,000 to $212,000 per case compared to the cost of a non-capital murder case in the same county. The study did not include the costs of prosecution or all appellate expenses. The author noted: “It is important to note that this statistical extrapolation does not cover the full array of time spent in capital cases by other court officials (e.g. judges, prosecutors, jurors), staff and administrative personnel, mitigation specialists, investigators, and expert witnesses. It also does not take into account the additional costs of capital litigation that are associated with state/federal appeals and the extra costs of imprisonment of death-eligible inmates pending trial and sentencing.

The study’s findings include:

- Clark County public defense attorneys spent an average of 2,298 hours on a capital murder case compared to an average of 1,087 hours on a non-capital murder case—a difference of 1,211 hours, or 112%.

- Defending the average capital murder case in Clark County cost $229,800 for a Public Defender or $287,250 for appointed counsel. The additional cost of capital murder cases was $170,000 to $212,000 per case compared to the cost of a non-capital murder case in the same county.

- The 80 pending capital murder cases in Clark County will cost approximately $15 million more than if they were prosecuted without seeking the death penalty.

- Clark County cases that resulted in a death sentence that concluded between 2009 and 2011 took an average of 1,107 days, or just over 3 years, to go from initial filing to sentencing. In contrast, cases that resulted in life without parole took an average of 887 days (2.4 years) to go from initial filing to sentencing.

- Of the 35 completed cases in Clark County from 2009 to 2011 where a Notice of Intent to seek the death penalty was filed, 69% resulted in a life sentence. Nearly half (49%) ultimately resulted in a sentence of life without parole, and the next most common disposition was a sentence of life with parole (20%). Only 5 of the 35 cases (14%) resulted in a death sentence.

A 2011 assessment of costs by Judge Arthur Alarcon and Prof. Paula Mitchell, updated in 2012 revealed that, since 1978, California’s current system has cost the state’s taxpayers $4 billion more than a system that has life in prison without the possibility of parole (‘LWOP’) as its most severe penalty.

According to the assessment , the death penalty cost California $1.94 billion in additional pre-trial and trial costs from 1978-2011. The post-trial costs were almost as high- $925 million for automatic appeals and state habeas corpus petitions, and $775 million for federal habeas corpus appeals. Incarceration of death row inmates was also a significant factor, the “adjustment center” of California’s death row at San Quentin State Penitentiary cost an additional $1 billion. The authors calculated that, if the Governor commuted the sentences of those remaining on death row to life without parole, it would result in an immediate savings of $170 million per year, with a savings of $5 billion over the next 20 years.

See DPIC’s Summary of the 2011 California Cost Study .

Federal Death Penalty

A 2010 report to the Committee on Defender Services Judicial Conference of the United States

The average cost of defending a trial in a federal death case is $620,932, about 8 times that of a federal murder case in which the death penalty is not sought. A study found that those defendants whose representation was the least expensive, and thus who received the least amount of attorney and expert time, had an increased probability of receiving a death sentence.

A 2010 state analysis of the costs of the death penalty in Indiana

The average cost to a county for a trial and direct appeal in a capital case was more than ten times more than a life-without-parole case. The total cost of Indiana’s death penalty is 38% greater than the total cost of life without parole sentences.

North Carolina

A 2009 study published by a Duke University economist revealed North Carolina could save $11 million annually if it dropped the death penalty. 10