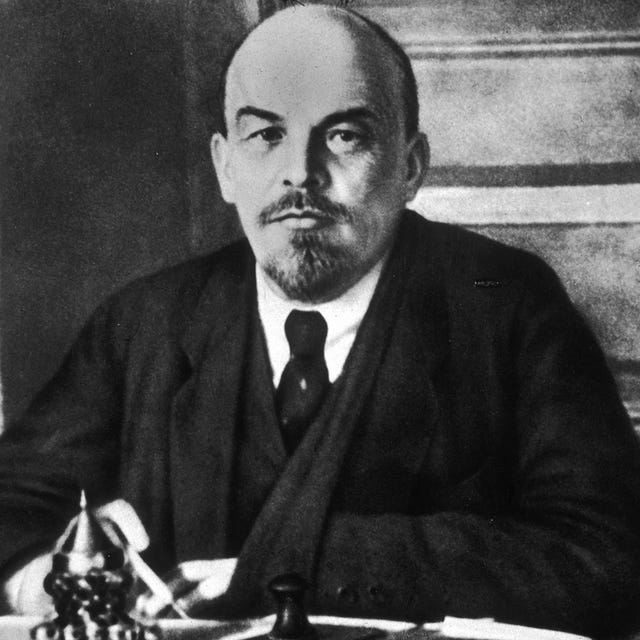

Vladimir Lenin

(1870-1924)

Who Was Vladimir Lenin?

Vladimir Lenin founded the Russian Communist Party, led the Bolshevik Revolution and was the architect of the Soviet state. He was the posthumous source of "Leninism," the doctrine codified and conjoined with Marx's works by Lenin’s successors to form Marxism-Leninism, which became the Communist worldview. He has been regarded as the greatest revolutionary leader and thinker since Marx.

Early Years

Widely considered one of the most influential and controversial political figures of the 20th century, Vladimir Lenin engineered the Bolshevik revolution in Russia in 1917 and later took over as the first leader of the newly formed Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

He was born Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov on April 22, 1870, in Simbirsk, Russia, which was later renamed Ulyanovsk in his honor. In 1901, he adopted the last name Lenin while doing underground party work. His family was well-educated, and Lenin, the third of six children, was close to his parents and siblings.

School was a central part of Lenin’s childhood. His parents, both educated and highly cultured, invoked a passion for learning in their children, especially Vladimir. A voracious reader, Lenin went on to finish first in his high school class, showing a particular gift for Latin and Greek.

But not all of life was easy for Lenin and his family. Two situations, in particular, shaped his life. The first came when Lenin was a boy and his father, an inspector of schools, was threatened with early retirement by a suspicious government nervous about the influence public school had on Russian society.

The more significant and more tragic situation came in 1887, when Lenin’s older brother, Aleksandr, a university student at the time, was arrested and executed for being a part of a group planning to assassinate Emperor Alexander III. With his father already dead, Lenin now became the man of the family.

Aleksandr’s involvement in oppositional politics was not an isolated incident in Lenin’s family. In fact, all of Lenin’s siblings would take part to some degree in revolutionary activities.

Young Revolutionary

The year of his brother’s execution, Lenin enrolled at Kazan University to study law. His time there was cut short, however, when, during his first term, he was expelled for taking part in a student demonstration.

Exiled to his grandfather’s estate in the village of Kokushkino, Lenin took up residence with his sister Anna, whom police had ordered to live there as a result of her own suspicious activities.

There, Lenin immersed himself in a host of radical literature, including the novel What Is To Be Done? by Nikolai Chernyshevsky, which tells the tale of a character named Rakhmetov, who carries a single-minded devotion to revolutionary politics. Lenin also soaked up the writing of Karl Marx, the German philosopher whose famous book Das Kapital would have a huge impact on Lenin’s thinking. In January 1889, Lenin declared himself a Marxist.

Eventually, Lenin received his law degree, finishing his schoolwork in 1892. He moved to the city of Samara, where his client base was largely composed of Russian peasants. Their struggles against what Lenin saw as a class-biased legal system only reinforced his Marxist beliefs.

In time, Lenin focused more of his energy on revolutionary politics. He left Samara in the mid-1890s for a new life in St. Petersburg, the Russian capital at the time. There, Lenin connected with other like-minded Marxists and began to take an increasingly active role in their activities.

The work did not go unnoticed, and in December 1895 Lenin and several other Marxist leaders were arrested. Lenin was exiled to Siberia for three years. His fiancée and future wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, joined him.

Following his release from exile and then a stint in Munich, where Lenin and others co-founded a newspaper, Iskra, to unify Russian and European Marxists, he returned to St. Petersburg and stepped up his leadership role in the revolutionary movement.

At the Second Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party in 1903, a forceful Lenin argued for a streamlined party leadership community, one that would lead a network of lower party organizations and their workers. “Give us an organization of revolutionaries,” Lenin said, “and we will overturn Russia!”

The Revolution of 1905 and WWI

Lenin’s call was soon supported by events on the ground. In 1904 Russia went to war with Japan. The conflict had a profound impact on Russian society. After a number of defeats put a strain on the country’s domestic budget, citizens from all walks of life began to vocalize their discontent over the country’s political structure and called for reform.

The situation was heightened on January 9, 1905, when a group of unarmed workers in St. Petersburg took their concerns directly to the city’s palace to submit a petition to Emperor Nicholas II. They were met by security forces, who fired on the group, killing and wounding hundreds. The crisis set the stage for what would be called the Russian Revolution of 1905.

Hoping to placate his citizens, the emperor issued his October Manifesto, offering up several political concessions, most notably the creation of an elected legislative assembly known as the Duma.

But Lenin was far from satisfied. His frustrations extended to his fellow Marxists, in particular, the group calling itself the Mensheviks, led by Julius Martov. The issues centered around party structure and the driving forces of a revolution to fully seize control of Russia. While his comrades believed that the power must reside with the bourgeoisie, Lenin passionately distrusted that segment of the population. Instead, he argued, a real and complete revolution, one that could lead to the Socialist Revolution that could spread outside of Russia, must be led by the workers, the country’s proletariat.

From the Mensheviks’ point of view, however, Lenin’s ideas really paved the way for a one-man dictatorship over the people he claimed he wanted to empower. The two groups had sparred since party’s Second Congress, which had handed Lenin’s group, known as the Bolsheviks, a slim majority. The fighting would continue until a 1912 party conference in Prague, when Lenin formally split to create a new, separate entity.

During World War I Lenin went into exile again, this time taking up residence in Switzerland. As always, his mind stayed focus on revolutionary politics. During this period he wrote and published Imperialism, The Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916), a defining work for the future leader, in which he argued that war was the natural result of international capitalism.

Russian Leader

In 1917, a tired, hungry and war-weary Russia deposed the tsars. Lenin quickly returned home and, perhaps sensing his own path to power, quickly denounced the country’s newly formed Provisional Government, which had been assembled by a group of leaders of the bourgeois liberal parties. Lenin instead called for a Soviet government, one that would be ruled directly by soldiers, peasants and workers.

In late 1917 Lenin led what was soon to be known as the October Revolution, but was essentially a coup d’état. Three years of civil war followed. The Lenin-led Soviet government faced incredible odds. The anti-Soviet forces headed mainly by former tsarist generals and admirals, fought desperately to overthrow Lenin’s Red regime. They were aided by World War I Allies, who supplied the group with money and troops.

Determined to win at any cost, Lenin showed himself to be ruthless in his push to secure power. He launched what came to be known as the Red Terror, a vicious campaign Lenin used to eliminate the opposition within the civilian population.

In August 1918 Lenin narrowly escaped an assassination attempt, when he was severely wounded with a pair of bullets from a political opponent. His recovery only reinforced his larger-than-life presence among his countrymen, though his health was never truly the same.

Despite the breadth of the opposition, Lenin came out victorious. But the kind of country he hoped to lead never came to fruition. His defeat of an opposition that wished to keep Russia tethered to Europe’s capitalist system, ushered in an era of international retreat for the Lenin-led government. Russia, as he saw it, would be void of class conflict and the international wars it fostered.

But the Russia he presided over was reeling from the bloody civil war he’d helped instigate. Famine and poverty shaped much of society. In 1921, Lenin now faced the same kind of peasant uprising he’d ridden to power. Widespread strikes in cities and in rural sections of the country broke out, threatening the stability of Lenin’s government.

To ease the tension, Lenin introduced the New Economic Policy, which allowed workers to sell their grain on the open market.

Later Years and Death

Lenin suffered a stroke in May 1922, and then a second one in December of that year. With his health in obvious decline, Lenin turned his thoughts to how the newly formed USSR would be governed after he was gone.

Increasingly, he saw a party and government that had strayed far from its revolutionary goals. In early 1923 he issued what came to be called as his Testament, in which a regretful Lenin expressed remorse over the dictatorial power that dominated Soviet government. He was particularly disappointed with Joseph Stalin, the general secretary of the Communist Party, who had begun to amass great power.

On March 10, 1923, Lenin’s health was dealt another severe blow when he suffered an additional stroke, this one taking away his ability to speak and concluding his political work. Nearly 10 months later, on January 21, 1924, he passed away in the village now known as Gorki Leninskiye. In a testament to his standing in Russian society, his corpse was embalmed and placed in a mausoleum on Moscow’s Red Square.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Vladimir Lenin

- Birth Year: 1870

- Birth date: April 22, 1870

- Birth City: Simbirsk

- Birth Country: Russia

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Vladimir Lenin was founder of the Russian Communist Party, leader of the Bolshevik Revolution and architect and first head of the Soviet state.

- World Politics

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Astrological Sign: Taurus

- Kazan University

- Death Year: 1924

- Death date: January 21, 1924

- Death City: Gorki

- Death Country: Russia

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Vladimir Lenin Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/political-figures/vladimir-lenin

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: May 7, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Famous Political Figures

Julius Caesar

10 of the First Black Women in Congress

Kamala Harris

Deb Haaland

Why Lewis Strauss Didn’t Like Oppenheimer

Madeleine Albright

These Are the Major 2024 Presidential Candidates

Hillary Clinton

Indira Gandhi

Toussaint L'Ouverture

Vladimir Putin

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Vladimir Lenin

By: History.com Editors

Updated: May 3, 2024 | Original: November 9, 2009

Vladimir Lenin was a Russian communist revolutionary and head of the Bolshevik Party who rose to prominence during the Russian Revolution of 1917, one of the most explosive political events of the 20th century. The bloody upheaval marked the end of the oppressive Romanov dynasty and centuries of imperial rule in Russia. The Bolsheviks would later become the Communist Party, making Lenin leader of the Soviet Union, the world’s first communist state.

Who Was Vladimir Lenin?

Vladimir Lenin was born Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov in 1870 into a middle-class family in Ulyanovsk, Russia. The son of Ilya Ulyanov and Maria Alexandrovna Ulyanova, he was the third of six siblings in an educated family and would go on to become first in his class in high school.

But it was exactly their educational background that made the family a target of the government; his father, an inspector of schools, was threatened with early retirement by officials wary of public education. As a teenager, Lenin became politically radicalized after his older brother was executed in 1887 for plotting to assassinate Czar Alexander III.

Later that year, 17-year-old Lenin—still known as Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov—was expelled from Kazan Imperial University, where he was studying law, for taking part in an illegal student protest. After his expulsion, Lenin immersed himself in radical political literature, including the writings of German philosopher and socialist Karl Marx , author of Das Kapital .

In 1889, Lenin declared himself a Marxist. He later finished college and received a law degree. Lenin practiced law briefly in St. Petersburg in the mid-1890s.

He soon was arrested for engaging in Marxist activities and exiled to Siberia. His fiancée and future wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, joined him there. The two would marry on July 22, 1898.

Lenin later moved to Germany and then Switzerland, where he met other European Marxists. During this time, he adopted the pseudonym Lenin and established the Bolshevik Party .

Russia in World War I

Russia entered World War I in August 1914 in support of the Serbs and their French and British allies. Militarily, imperial Russia was no match for modern, industrialized Germany. Russian participation in the war was disastrous: Russian casualties were greater than those sustained by any other nation, and food and fuel shortages soon plagued the vast country.

Lenin advocated for Russian defeat in World War I, arguing that it would hasten the political revolution he desired. It was during this time that he wrote and published Imperialism, The Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916) in which he argued that war was the natural result of international capitalism.

Hoping that Lenin could further destabilize their foe, the Germans arranged for Lenin and other Russian revolutionaries living in exile in Europe to return to Russia. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill later summed up the move by the Germans: “They turned upon Russia the most grisly of weapons. They transported Lenin in a sealed truck like a plague bacillus.”

HISTORY Vault: Vladimir Lenin: Voice of Revolution

Called treacherous, deluded, out-of-touch, insane, Lenin might have been a minor historical footnote but for the Russian Revolution, which catapulted him into the headlines of the 20th century.

Russian Revolution

When Lenin returned home to Russia in April 1917, the Russian Revolution was already beginning. Strikes over food shortages in March had forced the abdication of the inept Czar Nicholas II , ending centuries of imperial rule.

Russia came under the command of a Provisional Government, which opposed violent social reform and continued Russian involvement in World War I.

Lenin began plotting an overthrow of the Provisional Government. To Lenin, the provisional government was a “dictatorship of the bourgeoisie.” He advocated instead for direct rule by the workers and peasants in a “dictatorship of the proletariat.”

By fall of 1917, Russians had become even more war weary. Peasants, workers and soldiers demanded immediate change in what became known as the October Revolution.

Lenin, aware of the leadership vacuum plaguing Russia, decided to seize power. He secretly organized factory workers, peasants, soldiers and sailors into Red Guards—a volunteer paramilitary force. On November 7 and 8, 1917, Red Guards captured Provisional Government buildings in a bloodless coup d’état.

The Bolsheviks seized power of the government and proclaimed Soviet rule, making Lenin leader of the world’s first communist state. The new Soviet government ended Russian involvement in World War I with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk .

War Communism

The Bolshevik Revolution plunged Russia into a three-year civil war. The Red Army—backed by Lenin’s newly formed Russian Communist Party—fought the White Army, a loose coalition of monarchists, capitalists and supporters of democratic socialism.

During this time, Lenin enacted a series of economic policies dubbed “War Communism.” These were temporary measures to help Lenin consolidate power and defeat the White Army.

Under war communism, Lenin quickly nationalized all manufacturing and industry throughout Soviet Russia. He requisitioned surplus grain from peasant farmers to feed his Red Army.

These measures proved disastrous. Under the new state-owned economy, both industrial and agricultural output plummeted. An estimated five million Russians died of famine in 1921 and living standards across Russia plunged into abject poverty.

Mass unrest threatened the Soviet government. As a result, Lenin instituted his New Economic Policy, a temporary retreat from the complete nationalization of War Communism. The New Economic Policy created a more market-oriented economic system, “a free market and capitalism, both subject to state control.”

Soon after the Bolshevik Revolution, Lenin established the Cheka, Russia’s first secret police.

As the economy deteriorated during the Russian Civil War , Lenin used the Cheka to silence political opposition, both from his opponents and challengers within his own political party.

But these measures did not go unchallenged: Fanya Kaplan, a member of a rival socialist party, shot Lenin in the shoulder and neck as he was leaving a Moscow factory in August 1918, badly injuring him.

After the assassination attempt, the Cheka instituted a period known as the Red Terror, a campaign of mass executions against supporters of the czarist regime, Russia’s upper classes and any socialists who weren’t loyal to Lenin’s Communist Party.

By some estimates, the Cheka may have executed as many as 100,000 so-called “class enemies” during the Red Terror between September and October 1918.

Lenin Creates the U.S.S.R.

Lenin’s Red Army eventually won Russia’s civil war. In 1922, a treaty between Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and the Transcaucasus (now Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan) formed the Union of Soviet Republics (U.S.S.R. ).

Lenin became the first head of the U.S.S.R., but by that time, his health was declining. Between 1922 and his death in 1924, Lenin suffered a series of strokes which compromised his ability to speak, let alone govern.

His absence paved the way for Joseph Stalin , the Communist Party’s new General Secretary, to begin consolidating power. Lenin resented Stalin’s growing political power and saw his ascendency as a threat to the U.S.S.R.

Lenin dictated a number of predictive essays about corruption of power in the Communist Party while he was recovering from a stroke in late 1922 and early 1923. The documents, sometimes referred to as Lenin’s “Testament,” proposed changes to the Soviet political system and recommended that Stalin be removed from his position.

Lenin's Death and Tomb

Lenin died on January 21, 1924, in Gorki Leninskiye near Moscow. He was 53 years old. By that time, Stalin had already come to power—power he would do anything to keep, as evidenced by the Great Purge of 1936-38.

About a million people braved the cold Russian winter to stand in line for hours before paying their respects to Lenin, who was lying in state at the House of Trade Unions in Moscow.

Lenin’s body was moved several times following his death, from a mausoleum in Moscow’s Red Square to the distant city of Tyumen, Russia, for safekeeping during World War II . His embalmed body remains on display in Lenin’s tomb in Red Square.

Vladimir Lenin; PBS . Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924); BBC . Vladimir Lenin’s Return Journey to Russia Changed the World Forever; Smithsonian Magazine .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Biography Online

Lenin Biography

“We want to achieve a new and better order of society: in this new and better society there must be neither rich nor poor; all will have to work. Not a handful of rich people, but all the working people must enjoy the fruits of their common labour. Machines and other improvements must serve to ease the work of all and not to enable a few to grow rich at the expense of millions and tens of millions of people. This new and better society is called socialist society.”

Lenin’s Collected Works, Vol 6, p.366

Early Life – Lenin

Lenin was an able student, learning Latin and Greek. In 1887, he was thrown out of Kazan State University because he protested against the Tsar who was the king of the Russian Empire. He continued to read books and study ideas by himself, and in 1891 he got a license to become a lawyer.

In the same year that Lenin was expelled from University, his brother Alexander was hanged for his part in a bomb plot to kill Tsar Alexander III, and their sister Anna was sent to Tatarstan. This made Lenin furious, and he promised to get revenge for his brother’s death.

Lenin before the Revolution

Whilst studying law in St. Petersburg he learned about the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, both radical Marxist philosophers from Germany. Lenin developed a lifelong philosophy of seeking to overthrow Capitalist society and replace it with a fairer Communist society. He saw existing Capitalist society as inherently unjust.

“Freedom in capitalist society always remains about the same as it was in the ancient Greek republics: freedom for the slave-owners.”

– Lenin

For becoming involved and writing about Marxism, Lenin was arrested and sent to prison in Siberia.

In July 1898, when he was still in Siberia, Lenin married Nadezhda Krupskaya. In 1899 he wrote a book called The Development of Capitalism in Russia” . In 1900, Lenin was set free from prison and allowed to go back home. He then travelled around Europe. He began to publish a Marxist newspaper called Iskra, the Russian word for “spark” or “lightning”. He also became an important member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party or RSDLP.

In 1903, Lenin had a major argument with another leader of the party, Julius Martov, which divided the party in two. Lenin wanted a strict system where power would only be given to the government. Martov disagreed, and wanted the government to give power to ordinary people. People who agreed with Martov were called Mensheviks (meaning “the minority”). The people who agreed with Lenin were called Bolsheviks. (“the majority”)

In 1907 he travelled around Europe and visited many socialist meetings and events. During World War I, he lived in big European cities like London, Paris and Geneva. At the beginning of the war, he represented the Bolsheviks at the Second International which was formed of left-wing parties. However, the meeting was shut down when the disparate factions disagreed about whether to support or oppose the First World War. Lenin and the Bolsheviks were one of only a few groups who were against the war because of their Marxist ideas.

1917 Revolution

In 1917, people started rumours that Lenin had received money from the Germans. That made him look bad because a lot of Russians had died fighting Germany in the war. The rumours were so bad he was afraid he could get arrested or even killed. He left Russia and went to Finland, a country right next to Russia, where he could hide and carry on with his work on Communism.

After Tsar Nicholas II gave up his throne during the February Revolution, Germany hoped that they could persuade Russia to leave the war. The German government helped Lenin to secretly return to Russia, in the hope that Lenin would help end Russia’s involvement in the war. Lenin was still considered to be a very important Bolshevik leader, and he saw the great discontent of the population giving a unique opportunity for revolution. He wrote that he wanted a revolution by ordinary workers to overthrow the government that had replaced Nicholas.

In October 1917, the Bolsheviks, led by Lenin and Trotsky, headed the Petrograd Soviet and other Soviets all over Russia in a revolution against Kerensky’s government, which was known as the October Revolution. The revolution was successful as the army was unwilling to turn on the people. Lenin announced that Russia was now a Communist country and by November, Lenin was chosen as its leader.

Because Lenin wanted an end to World War One in Russia, he signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany in February 1918. While the treaty ended the war with Germany, Russia paid a high price in terms of lost land. But to Lenin ending the war was critical.

“The government considers it the greatest of crimes against humanity to continue this war over the issue of how to divide among the strong and rich nations the weak nationalities they have conquered, and solemnly announces its determination immediately to sign terms of peace to stop this war on the terms indicated, which are equally just for all nationalities without exception.”

Report on Peace (8 November 1917), Lenin’s Collected Works, Volume 26

The Russian treaty with Germany made the Allied powers, e.g. Great Britain and France displeased. Also, the great powers feared that if a Communist revolution could happen in Russia, it could happen elsewhere in Europe. Allied governments sent support to ‘White’ Russians – people loyal to the Tsar or Kerensky’s government. There was an on-going civil war, with the Bolsheviks having to fight across the country. Lenin made rules that as much food as possible was to be given to Communist soldiers in Russia’s new Red Army. This was a factor in winning the civil war, but, during this period, many ordinary many died of hunger or disease.

After the war, Lenin brought in the New Economic Policy to try and make things better for the country. Some private enterprise was allowed, but not much. Businessmen, known as nepmen, could only own small industries, not factories.

After a woman named Fanny Kaplan shot Lenin in 1918, he started having strokes. By May 1922, he was badly paralysed. After another stroke in March 1923, he could not speak or move. Lenin’s fourth stroke killed him in January 1924. Just before he died, Lenin had wanted to get rid of Stalin because he thought he was dangerous to the country and the government.

The city of St. Petersburg had been renamed Petrograd by the Tsar in 1914, but was renamed Leningrad in memory of Lenin in 1924.

Before Lenin died, he said he wished to be buried beside his mother. When he died, Stalin decided to let the people in Russia come and look at his body. Because so many people kept coming, they decided not to bury him and preserved his body instead. A building was built in Red Square, Moscow over the body so that people could see it. It is called the Lenin Mausoleum. Many Russians and tourists still go there to see his body today.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Lenin ”, Oxford, www.biographyonline.net 23 August 2009. Updated 2 February 2018.

Lenin: A Biography

- Lenin: A Biography at Amazon

Related pages

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

Early Life and Education

- Vladimir Lenin FAQs

The Bottom Line

- Government & Policy

Who Was Vladimir Lenin? His Life, Beliefs, Deeds, and Legacy

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/wk_headshot_aug_2018_02__william_kenton-5bfc261446e0fb005118afc9.jpg)

Erika Rasure is globally-recognized as a leading consumer economics subject matter expert, researcher, and educator. She is a financial therapist and transformational coach, with a special interest in helping women learn how to invest.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/CSP_ER9-ErikaR.-dce5c7e19ef04426804e6b611fb1b1b4.jpg)

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov "Lenin" was the architect of Russia’s 1917 Bolshevik revolution and the first leader of what became the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

Through violent means, he established a system of Marxist socialism called communism in the former Russian Empire, which attempted to impose collective control over the means of production, redistribute wealth, abolish the aristocracy, and create a more equitable society for the masses.

Key Takeaways

- Vladimir Ilyich "Lenin" Ulyanov was a principal ringleader of Russia's communist revolution, which led to the founding of the USSR.

- Lenin was the son of a well-off, upper middle-class family who rose to power by exploiting the dissatisfaction of the urban working poor and rural peasants.

- Lenin's revolution, the resulting civil war and famines, and the brutal domestic repression that he led against dissidents and scapegoats directly led to the deaths of over 8 million citizens of the Russian Empire, many by starvation, torture, or summary execution.

Investopedia / Bailey Mariner

Lenin spent his adult life agitating for and leading revolutionary communist activities in Russia. This culminated in the 1917 October Revolution, which brought Lenin's Bolshevik faction to power. In the wake of the Revolution, the reign of the Bolshevik regime under Lenin was marked by economic chaos and deprivation; bloody civil war; massive (sometimes deliberate) famines among the rural working class ; and brutal repression, torture, and murder of those suspected or accused of dissent, insufficient loyalty to the Revolution, or of holding out food or other goods.

Despite these crimes, Lenin is still revered among some communists, communist sympathizers, and citizens of former USSR republics. A 2017 Russian poll done by the Levada Center found that Lenin’s reputation as the father of his country is diminished but by no means undone. Fifty-six percent of Russians believe that he played an entirely or mostly positive role in Russian history, up from 40% in 2006; however, many of those polled couldn’t be specific about what he had done.

Lenin was born in 1870 in what was then Simbirsk, about 450 miles east of Moscow. His family, with the last name Ulyanov, was middle class and prosperous. Two 1887 events shaped his revolutionary beliefs: the execution of his older brother, Alexandr for an attempt to murder the Russian Tsar; and his expulsion from Kazan University for being the ringleader of a student uprising.

While becoming a Marxist in 1889, he later was allowed to sit for his law examinations and earned a law degree from St. Petersburg University. He became a public defender and part of a group of revolutionary Marxists.

Eventually, his activities got him exiled to Siberia for three years, from 1897 to 1900. After that he adopted the pseudonym, "Lenin", and moved to Europe, to continue his revolutionary activities. He returned to Russia to agitate for the, ultimately failed, Revolution of 1905, then returned abroad to Europe in 1907.

The Russian Revolution

Lenin returned to Russia in April 1917 after the czar had abdicated and the Soviet Revolution was underway. The country was being run by a provisional government, which Lenin termed “a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie .” He envisioned a “dictatorship of the proletariat,” in which workers and peasants ruled.

Russians were in despair over the toll that World War I was taking on the country and wanted change, and that war-weariness allowed Lenin and his Red Guards, a secretly organized army of peasants, workers, and disaffected Russian military men, to seize control of the government in a nearly bloodless coup d'état in November 1917.

The Russian Civil War

Once in power, Lenin withdrew Russia from WWI, but his Red Army ended up fighting a three-year civil war with the White Army, a coalition of monarchists, capitalists , and democratic socialists . To fund the war, Lenin instituted something called “War Communism,” which nationalized all manufacturing and industry and requisitioned grain from farmers to feed the troops and sell abroad to raise cash for the government.

Socialism is considered to be the stepping stone from capitalism to communism. Communism involves complete control of economic resources by the state, while under socialism, citizens equally share economic resources that are distributed by a democratically elected government.

After an attempted assassination in 1918 in which he was seriously wounded, Lenin waged the Red Terror through the Bolshevik secret police, known as the Cheka. By some estimates, more than 100,000 people thought to be against the aims of the revolution, (known as “counterrevolutionaries”) or simply related to those who were in opposition, were murdered.

The Red Army vanquished the final remnants of the White Army in Crimea in November 1920. Between the Red Terror, the Russian Civil War, and the resulting famines due to War Communism, an estimated 1.5 million combatants and 8 million civilians were killed by Lenin's revolutionary efforts during this period.

Forming the USSR

Lenin’s War Communism eventually ruined the economy. After the Russian famine of 1921, which killed at least five million people, he introduced his New Economic Policy in an attempt to prevent a second revolution. It permitted some private enterprise , introduced a wage system, and let peasants sell produce and other goods on the open market while having to pay tax on any earnings, either in money or raw goods . State-owned enterprises such as steel operated on a for-profit basis.

Lenin suffered a series of strokes between 1922 and 1924 that made speaking and governing difficult. He died on Jan. 21, 1924, barely a year after the Bolsheviks finally established the USSR, on Dec. 30, 1922, through a treaty among Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and the Transcaucasian Federation (later Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan). His body was embalmed and put on display in a mausoleum in Moscow’s Red Square, where it still is today.

The legacy of Lenin is a complicated one. He sought to improve the lives of the peasants, the working class, and the poor of Russia, who were suffering under the aristocratic ways of the Russian Empire. Though he ushered in a revolution and a new form of government , his tactics were brutal, resulting in the deaths of millions.

In addition, he created the USSR, which under Stalin became an even more brutal regime, resulting in the deaths of millions more, and complicating geopolitical affairs throughout the 20th century and even the 21st century after its collapse.

The initial goal of Lenin's revolution was never quite achieved. Though the Russian aristocracy was destroyed, the lives of many did not improve.

Lenin published many writings on his thoughts about Marxism, capitalism, the Russian empire, and revolution. Some of his most important works covering these topics include the April Theses , The Development of Capitalism in Russia, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism , What Is to Be Done? Burning Questions of Our Movement , and The Three Sources and Three Component Parts of Marxism ."

What Happened to Vladimir Lenin?

Vladimir Lenin died in 1924 at the age of 54 due to a brain hemorrhage. He had suffered strokes before this. Upon his death, Stalin became the leader of the Soviet Union.

What Did Vladimir Lenin Accomplish?

Lenin led the revolutionary uprising that brought the Bolshevik faction of communism to power in Russia and across the territories of the old Russian Empire. This was one of the major events of world history in the 20th century, which would influence the course of economic, political, and strategic trends all over the world. Lenin's revolution and establishment of the Soviet Union resulted in the deaths of many millions of Russians and others, and it drove the world into a century of episodic wars and diplomatic conflicts known as the Cold War.

What Did Vladimir Lenin Want in World War I?

At the time of World War I, Russia was still an empire ruled by a monarch; Czar Nicholas II. Lenin wanted Russia to lose in World War I as he believed it would bring about the political revolution he had been hoping for. He wrote and published various works during this time. Lenin was not in Russia during the war but did return to further flame the revolution that had already started.

Vladimir Lenin was one of the most influential people in history who brought about significant change in his country that reverberated around the world and impacted the lives of millions. Though his thoughts on Marxism and capitalism are read to this day and influence many individuals and nations, his legacy will also be remembered for his brutal regime and the deaths of millions.

BBC - History. " Vladimir Lenin (1870 -1924) ."

PBS. " Vladimir Lenin ."

Levada Center. " Vladimir Lenin ."

Guinness Book of World Records. " Highest Death Toll From A Civil War ."

Alpha History. " The Great Famine of 1921 ."

Biography. " Vladimir Lenin ."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Communism_Final_4199095-8df1cde2ab814aa1942ff1b970e36074.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

- World Biography

Vladimir Lenin Biography

Born: April 10, 1870 Ulianovsk, Russia Died: January 21, 1924 Moscow, Russia Russian statesman

The Russian statesman Vladimir Lenin was a profoundly influential figure in world history. As the founder of the Bolshevik political party, he was a successful revolutionary leader who presided over Russia's transformation from a country ruled by czars (emperors) to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.), the name of the communist Russian state from 1922 to 1991.

Early years

Vladimir Ilich Lenin was born in Simbirsk (today Ulianovsk), Russia, on April 10, 1870. His real family name was Ulianov, and his father, Ilia Nikolaevich Ulianov, was a high official in the area's educational system. Because Lenin's father had risen into the ranks of the Russian nobility, Lenin grew up in fairly privileged circumstances. Although he would fight as an adult for a revolution by the working lower classes, he did not come from such a hard-working background himself.

Lenin received the typical education given to the sons of the Russian upper class. Nevertheless, as a young man he began to develop radical (extreme) political views in disagreement with the existing Russian form of government. Russia at this time was ruled by emperors known as czars who inherited their positions, and Lenin's shift to radical views was probably fueled by the execution by hanging of his older brother Alexander in 1887 after Alexander and others had plotted to kill the czar. Lenin graduated from secondary school with high honors and enrolled at Kazan University, but he was expelled after participating in a demonstration. He retired to the family estate but was permitted to continue his studies away from the university. He obtained a law degree in 1891.

In 1893 Lenin moved to St. Petersburg, Russia. By this time he was already a Marxist—an admirer of the German writer Karl Marx (1818–1883). Marx (and his associate Friedrich Engels [1820–1895]) had believed in an international revolution (overthrow of the government) of the poor and lower-class workers (called the proletariat) who would lead the way to a new system of power. Under this new system, Marx argued, property would be owned communally (as a group) and work would be distributed equally. By 1893 Lenin had also become a revolutionary by profession. He wrote controversial papers and articles and tried to organize workers. The St. Petersburg Union for the Struggle for the Liberation of Labor, which Lenin helped create, was one of the seeds that started the Russian Marxist movement.

In 1897 Lenin was arrested, spent some months in jail, and was finally sentenced to three years of exile (forced absence from one's native country or region) in the remote area of Siberia. He was joined there by a fellow Marxist, Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya (1869–1939), whom he married in 1898. During his Siberian exile he produced a major study of the Russian economy, The Development of Capitalism in Russia.

Emigration to Europe

Not long after Lenin was released from Siberia in the summer of 1900, he moved to Europe. He spent most of the next seventeen years there, moving from one country to another frequently. His first step was to join the editorial board of Iskra (The Spark), the central newspaper of Russian Marxism at the time. After parting from Iskra, he edited a series of papers of his own and contributed to other journals promoting socialism (a version of Marxism). His journalistic activity was closely linked with efforts to organize revolutionary groups, partly because the illegal organizational network within Russia was partly based on the distribution of illegal literature.

Organizational activity, in turn, was linked with the selection and training of people who would work for the cause. For some time Lenin conducted a training school for Russian revolutionaries at Longjumeau, a suburb of Paris, France. Finding funds for the movement and its leaders' activities in Europe was also a problem. Lenin could usually depend on financial support from his mother for personal use, but she could not pay for his political activities.

Lenin's ideas

A Marxist movement had developed in Russia during the last decade of the nineteenth century. It was a response to the rapid growth of industry, cities, and the proletariat (a group of lower-class workers, especially in industry). Its first intellectual spokesmen were people who had turned away from relying on the peasants (rural poor people) of the Russian villages and countryside, and they placed their hopes on the proletariat. They aimed for a revolution that would transform Russia into a democratic republic. Lenin's writings and work focused on the role of the proletariat as promoters of this revolution. However, he also stressed the role of intellectuals (people engaged in thinking) who would provide the movement with the theories that would guide the revolution's progress.

Lenin expressed these ideas in his important book What's to Be Done? in 1902. When the leaders of Russian Marxism gathered for the first important party meeting in 1903, these ideas clashed with the idea of a looser, more democratic workers' party that was promoted by Lenin's old friend Iuli Martov (1873–1923). This disagreement over the nature and organization of the party was complicated by many other conflicts, and from its first important gathering Russian Marxism split into two factions (opposing groups). The one led by Lenin called itself the majority faction (bolsheviki, or the Bolsheviks), while the other took the name of minority faction (mensheviki, or the Mensheviks). The Bolsheviks and Mensheviks disagreed not only over how to organize the movement but also over most other political problems.

Bolshevism and Marxism

Over the next twelve years bolshevism, which had begun as a faction within the Russian Social-Democratic Workers party, gradually emerged as an independent party that had cut its ties with all other Russian Marxists. The process involved long and bitter arguments against Mensheviks as well as against all those who worked to reunite the factions. It involved fights over funds, struggles for control of newspapers, the development of rival organizations, and meetings of rival groups. Disputes concerned many questions about the goals and strategies of Marxism and the role of national (rather than international) struggles within Marxism.

Since about 1905 the international socialist movement had begun also to discuss the possibility of a major war breaking out among European nations. In 1907 and 1912, members met and condemned such wars in advance, pledging not to support them. Lenin had wanted to go further than that. He had urged active opposition to the war effort and a transformation of any war into a proletarian revolution. When World War I (1914–1918; a conflict involving most European nations, as well as Russia, the United States, and Japan) broke out, most socialist leaders in the countries involved supported the war effort. For Lenin, this was proof that he and the other leaders shared no common aims or views. The break between the two schools of Marxism could not be fixed.

During World War I (1914–18) Lenin lived in Switzerland. He attended several conferences of radical socialists opposed to the war. He read a large amount of literature on the Marxist idea of state government and wrote a first draft for a book on the subject, The State and Revolution. He also studied literature dealing with world politics of the time and wrote an important book, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, in 1916. By the beginning of 1917 he had fits of depression and wrote to a close friend that he thought he would never see another revolution. This was about a month before the overthrow of the Russian czar in the winter of 1917, which marked the beginning of the 1917 Russian Revolution.

Lenin in 1917

It took a good deal of negotiation and courage for Lenin and a group of like-minded Russian revolutionaries to travel from Switzerland back to Russia through the enemy country of Germany. The man who returned to Russia in the spring of 1917 was of medium height, quite bald, except for the back of his head, with a reddish beard. The features of his face were striking—slanted eyes that looked piercingly at others, and high cheek-bones under a towering forehead. The rest of his appearance was deceptively ordinary.

Fluent in many languages, Lenin spoke Russian with a slight speech defect but was a powerful public speaker in small groups as well as before large audiences. A tireless worker, he made others work tirelessly. He tried to push those who worked with him to devote every ounce of their energy to the revolutionary task at hand. He was impatient with any other activities, including small talk and discussions of political theories. Indeed, he was suspicious of intellectuals and felt most at home in the company of simple folk. Having been brought up in the tradition of the Russian nobility, Lenin loved hunting, hiking, horseback riding, boating, mushroom hunting, and the outdoor life in general.

Once he had returned to Russia, Lenin worked constantly to use the revolutionary situation that had been created by the fall of the czar and convert it into a proletarian revolution that would bring his own party into power. As a result of his activities, opinions in Russia quickly became more and more sharply at odds. Moderate forces found themselves less and less able to maintain any control. In the end, by October 1917 power fell into the hands of the Bolsheviks. As a result of the so-called October Revolution, Lenin found himself not only the leader of his party but also the chairman of the Council of People's Commissars (equivalent to prime minister) of the newly proclaimed Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic (the basis for the future Union of Soviet Socialist Republics).

Ruler of Russia

During the next few years Lenin was essentially dictator (a ruler with unquestionable authority) of Russia. The major task he faced was establishing this authority for himself and his party in the country. Most of his policies can be understood in this light, even though he angered some elements in the population while satisfying others. Examples of such policies include the government's seizing of land from its owners and redistributing it to the peasants, forming a peace treaty with Germany, and the nationalization (putting under central governmental control) of banks and industry.

From 1918 to 1921 a fierce civil war raged, which the Bolsheviks finally won against seemingly overwhelming odds. During the civil war Lenin tightened his party's dictatorship and eventually eliminated all rival political parties. Lenin had to create an entirely new political system with the help of inexperienced people. He was also heading a failing economy and had to create desperate means for putting people to work. He also created the Third (Communist) International, an association of parties that promoted the spread of the revolution to other countries and that enforced the Soviet system as a model for this movement. Meanwhile he had to cope with conflict and criticism from his own party colleagues.

When the civil war had been won and the regime firmly established, the economy was ruined, and much of the population was bitterly opposed to the regime. At this point Lenin reversed many of his policies and instituted a reform called the New Economic Policy. It was a temporary retreat from the goal of establishing socialism at once. Instead, the stress of the party's policies would be on economic rebuilding and on the education of a peasant population for life in the twentieth century. In the long run, Lenin hoped both these policies would make the benefits of socialism obvious to all, so the country would gradually grow into socialism.

On May 26, 1922, Lenin suffered a serious stroke (a loss of consciousness due to the rupture or blockage of an artery in the brain). After recovering from this first stroke, he suffered a second on December 16. He was so seriously ill that he could participate in political matters only occasionally. He moved to a country home at Gorki, Russia, near Moscow, where he died on January 21, 1924.

For More Information

Carrère d'Encausse, Hélène. Lenin. New York: Holmes & Meier, 2001.

Cliff, Tony. Lenin. London: Pluto Press, 1979.

Service, Robert. Lenin—A Biography. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Volkogonov, Dmitri. Lenin: A New Biography. New York: Free Press, 1994.

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- Journal of Interdisciplinary History

Lenin: A Biography (review)

- Tsuyoshi Hasegawa

- The MIT Press

- Volume 33, Number 3, Winter 2003

- pp. 482-484

- View Citation

Additional Information

Project MUSE Mission

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

Search the Holocaust Encyclopedia

- Animated Map

- Discussion Question

- Media Essay

- Oral History

- Timeline Event

- Clear Selections

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Português do Brasil

Featured Content

Find topics of interest and explore encyclopedia content related to those topics

Find articles, photos, maps, films, and more listed alphabetically

For Teachers

Recommended resources and topics if you have limited time to teach about the Holocaust

Explore the ID Cards to learn more about personal experiences during the Holocaust

Timeline of Events

Explore a timeline of events that occurred before, during, and after the Holocaust.

- Introduction to the Holocaust

- Antisemitism

- How Many People did the Nazis Murder?

- Book Burning

- German Invasion of Western Europe, May 1940

- Voyage of the St. Louis

- Genocide of European Roma (Gypsies), 1939–1945

- The Holocaust and World War II: Key Dates

- Liberation of Nazi Camps

Vladimir Lenin

In 1933, Nazi students at more than 30 German universities pillaged libraries in search of books they considered to be "un-German." Among the literary and political writings they threw into the flames were the works of Vladimir Lenin.

- book burning

While the state exists, there will be no freedom. When freedom exists, there will be no state. — The State and Revolution , Vladimir Lenin, 1919

Which of Vladimir Lenin's Works were Burned?

All, with the exception of Der Radikalismus die Kinderkrankheit des Kommunismus (Left-wing Communism, an Infantile Disorder: A Popular Essay in Marxian Strategy and Tactics) and Die Revolution von 1917 (The Revolution of 1917)

Who was Vladimir Lenin?

Lenin was a radical Marxist throughout most of his career. He left Russia to continue his revolutionary activities abroad. Lenin opposed World War I , which he saw as an imperialist struggle. He encouraged the proletariat to rise up and rebel against the capitalist society at home. Lenin returned to Russia after the Russian Revolution broke out in February 1917, and became the virtual dictator of the new Soviet government. Lenin died, after a stroke, in January 1924.

The Nazis had declared themselves the sworn enemies of Bolshevik Russia, its architect and dictator Vladimir Lenin, and his successor Josef Stalin . Lenin's writings, advocating a worldwide revolution of the proletariat under a highly disciplined cadre of leaders, made most of his books immediate targets for burning .

Thank you for supporting our work

We would like to thank Crown Family Philanthropies and the Abe and Ida Cooper Foundation for supporting the ongoing work to create content and resources for the Holocaust Encyclopedia. View the list of all donors .

Vladimir Lenin

- Occupation: Chairman of the Soviet Union, Revolutionary

- Born: April 22, 1870 at Simbirsk, Russian Empire

- Died: January 21, 1924 at Gorki, Soviet Union

- Best known for: Leading the Russian Revolution and establishing the Soviet Union

- Lenin's birth city of Simbirsk was renamed Ulyanovsk in his honor (his birth name).

- In 1922 Lenin wrote his Testament . In this document he raised concerns about Joseph Stalin and thought he should be removed from office. Stalin, however, was already too powerful and succeeded Lenin after his death.

- He married fellow revolutionary Nadya Krupskaya in 1898.

- He took the name "Lenin" in 1901. This likely came from the River Lena where he was exiled for three years in Siberia.

- Lenin founded and managed the communist newspaper called Iskra in 1900.

- Listen to a recorded reading of this page:

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Slovenščina

- Science & Tech

- Russian Kitchen

How Lenin was once robbed

The scandalous incident occurred in Moscow on January 6, 1919 - Vladimir Lenin was already at the head of the young Soviet state.

The attack on the leader’s car was committed by a gang of a well-known robber named Yakov Koshelkov. The criminals had no idea whose car it was - they just needed transport that night.

The gang rushed in front of the car shouting: "Stop! We'll shoot!" In the thickening dusk, Lenin confused it with a patrol.

Lenin's Rolls-Royce.

When the car stopped, the criminals dragged out the Soviet leader, along with his guard. A stunned Vladimir uttered: "What are you doing? I am Lenin. Here are my documents."

Because of the engine noise, the ringleader misheard his last name: "To hell with you, that you are Levin! And I am Koshelkov, the master of the city at night." With these words he took the documents, money and the Soviet leader's personal Browning pistol.

The criminals drove away a few hundred meters and began to examine their spoils. It was only then that they realized who they could take hostage and what a huge ransom they could get for him. They immediately rushed back, but there was no one there.

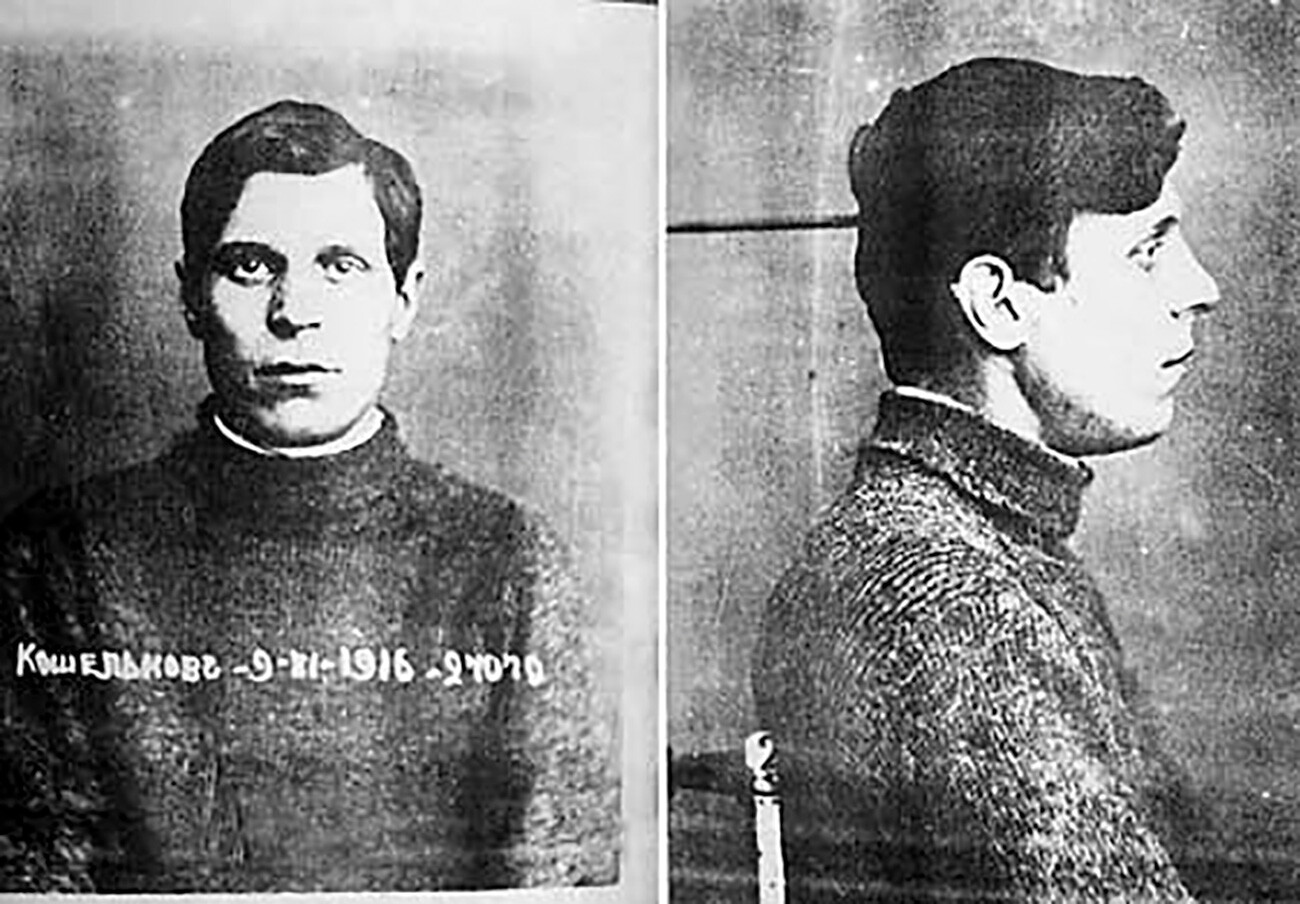

Yakov Koshelkov.

The city was in turmoil: Lenin's personal security was strengthened and all city police and special service forces were mobilized. In the end, 200 people were detained, but the attackers were not among them.

Nevertheless, by the Summer of 1919, one by one, all members of Koshelkov's gang were captured, convicted and shot. The ringleader himself was killed during his arrest on July 26.

Lenin's Browning was found on him, but whether it was returned to the Soviet leader remains unknown.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox

- How did Vladimir Lenin die?

- Everything you need to know about Lenin

- Vladimir Lenin’s life in 13 PHOTOS

This website uses cookies. Click here to find out more.

The Point Conversations and insights about the moment.

- Share full article

Paul Krugman

Opinion Columnist

Is Disinflation Back on Track?

The latest news on inflation has been pretty good. It has also been extremely weird. And that weirdness is, in a way, the message.

With underlying inflation fairly low but probably still above the Fed’s 2 percent target and people still worried that it might go back up, quirky measurement issues can lead to big mood swings that are quickly reversed when the next numbers come in — or sometimes even a few hours after the initial announcement, once knowledgeable people have had some time to dig into the details.

There were two big official inflation reports in the past couple of days: the Producer Price Index (what we used to call wholesale prices) on Tuesday and the Consumer Price Index on Wednesday morning . There was also a private survey from the National Federation of Independent Business that may add some clarity.

So what do I mean by “weirdness”? On Tuesday I was busy most of the day with plumbers and dentists, so I was able to check in on events and commentary only once in a while. But this enforced limitation on the information flow might actually have given me more perspective. The first thing I saw was a hot P.P.I., with inflation coming in well above expectations. There was much wailing and rending of garments. Then, as the analysts I follow had time to parse the details, they started to declare that this was actually a good report.

Financial markets seemed to agree. One quick and dirty way to judge how markets view inflation data is to look at the yield on two-year U.S. Treasuries, which largely reflects what people think the Fed is going to do. If inflation looks hot, they expect the Fed to keep rates high and maybe even increase them; if it looks cool, they expect the opposite.

And if you look at two-year yields over the past few days, you see the market reaction matching my sense of the commentary:

Yields spiked when the P.P.I. report was released, then fell back once there was time to dig into the numbers, ending the day lower than they started.

On the other hand, markets from the get-go liked the C.P.I., which seemed to show inflation resuming its downward trend, with yields falling sharply. But as I write, analysts are still digging into the details. Will they be less optimistic by evening? Probably not: Early commentary seems, if anything, to be saying that the numbers were even better than they first appeared. But after yesterday, I’m going to wait and see.

I also mentioned the survey from the N.F.I.B., which represents small and medium businesses. One question it asks is whether businesses are planning to raise or lower prices over the next three months; the percentage difference from current numbers is often a useful indicator of inflation trends. And that spread is currently close to what it was before the pandemic, although slightly higher:

So my best guess? The acceleration in measured inflation over the past few months was probably a statistical illusion; inflation wasn’t as low as it seemed in late 2023 but probably hasn’t risen much, if at all. Underlying annual inflation is probably around 2.5 percent, maybe even less. So my guess is that we’ve already won this war — that we have basically achieved a soft landing, with low unemployment and acceptably low inflation.

But I could be wrong, and even if I’m right, it’s going to take at least a few more months of good inflation news before this happy reality sinks in.

Frank Bruni

Contributing Opinion Writer

Biden’s Daring Debate Proposal Could Recharge His Campaign

I’ve been waiting and hoping — no, I’ve been desperate — for President Biden to do two things. One, boldly project strength. Two, recognize that he cannot coast to re-election and that he needs to shake up the state of the presidential race.

With his offer on Wednesday to debate Donald Trump at least twice before the election and as early as next month, he has done just that.

The Biden campaign’s proposal came with the condition that the debates be in a television studio and there be no audience present to hoot, holler and otherwise interrupt. Trump subsequently indicated that he was onboard, though it wasn’t clear if he would agree to Biden’s terms.

By emphasizing debates and suggesting that they start soon, Biden is taking a risk. But it’s a necessary one. Trump and his supporters lean hard on the charge that Biden is too rickety — in terms of both energy and intellect — to face off against Trump, and they have sold that idea skillfully and mercilessly, with the help of right-wing news organizations that portray Biden as a doddering wreck. It’s selective and often malicious stuff, but that doesn’t mean that Biden can ignore it. He must refute it. Signaling an eagerness to debate is the crucial first step.

The next one is performing well in those debates, should they happen, and that’s where the risk comes in. Some Democrats who’ve spent time with Biden over the past year privately express concerns about his sharpness and stamina, and a debate is less scripted — and arguably more draining — than a State of the Union speech read from a teleprompter. But a reluctance or refusal to debate could be as damaging to Biden as half a dozen terrible moments at the lectern.

Besides which, Trump could have scores of such moments, to go by his bizarro stump speeches of late. That’s where the rewards that Biden could reap come in. Do I think that he will turn in debate performances for the ages? No. Do I think that Trump will have a harder time insisting on Biden’s wobbliness if he has demonstrated his own profound unsteadiness on the same stage where Biden is standing, with plenty of swing voters watching? Yes.

I also think that it’s past time for Biden to pivot from caution to daring. Maybe that pivot is finally here.

Advertisement

Serge Schmemann

Editorial Board Member

Putin’s Defense Shake-Up Is a Danger for Ukraine

With Vladimir Putin’s revival of Soviet-style centralized and secretive rule, the old art of Kremlinology is making a comeback. It’s not quite the same as when the lineup atop Lenin’s mausoleum on May Day was scrutinized for signs of who was on the way up or down, but Putin’s abrupt replacement of the long-serving Sergei Shoigu as defense minister last Sunday was still a distinct blast from that dismal past.

Technically, Shoigu was kicked upstairs, to head up the national security council. Putin is not given to publicly punishing loyal courtiers, and Shoigu was about as loyal as they come, even going fishing and hunting with the boss. Still, Kremlin-watchers have long expected his ouster, given the sloppiness of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the widespread corruption in the military-industrial complex, and Shoigu’s reported unpopularity with the generals. There was also the dramatic rebellion of the mercenary commander Yevgeny Prigozhin, who marched on Moscow last June demanding Shoigu’s head (only to lose his own in a plane crash broadly presumed to have been an assassination).

So, very briefly, here are the questions and speculation now keeping Kremlinologists busy:

Shoigu’s replacement at the Defense Ministry is Andrei Belousov, a senior Kremlin economist. That he is not a military man is not surprising; neither was Shoigu, a former construction foreman, nor his two predecessors. Military matters are handled by the generals of the General Staff; the defense minister looks after the military-industrial base. The thinking is that Belousov’s task will be to manage the rapid growth in Russia’s military spending and to clean up the corruption that is siphoning off huge amounts of the money earmarked for the Ukraine war.

How long Shoigu will be allowed to survive remains an open question. One of his top deputies, Timur Ivanov, was arrested on bribery charges in April. One of Ivanov’s nicknames was “Shoigu’s wallet.” And on Tuesday morning, government investigators announced that a senior general on the General Staff, Lt. Gen. Yuri Kuznetsov, had been detained on suspicion of “large-scale” bribe-taking.

A big question is what happens to Nikolai Patrushev, who is being displaced by Shoigu at the helm of the Russian security council. Patrushev, like Putin a former K.G.B. official, is among the oldest and closest members of Putin’s ruling clique, and among the most hawkish. Where he lands — or fails to land — will say a lot about where Putin is headed.

On balance, the musical chairs point to a major overhaul of the military as Russia moves toward what is basically a war economy. Russia is making incremental but steady advances in Ukraine, albeit at an astounding cost in casualties and armaments. Putin’s plan is to press on at any cost, squeezing Ukraine and its ever more reluctant Western backers, and keeping China on board as a major supplier. None of that bodes well for Ukraine.

Jonathan Alter

Where’s the Devastating Takedown of Michael Cohen That Trump Needs?

For months, we’ve known that the cross-examination of Michael Cohen would be the decisive moment of Donald Trump’s New York felony trial — the day we learned whether his defense team could plant reasonable doubt in the minds of jurors.

On Tuesday it became clear that the team was struggling with its most important task.

Todd Blanche, Trump’s lead defense lawyer, was like a baseball pitcher assigned to start Game 7 of the World Series after only two or three wins in his major-league career. Though a seasoned former federal prosecutor, he has little experience as a defense attorney — and it showed.

We’re only about a third of the way through Blanche’s cross, but so far, he’s too meandering and pleasant for the sharp-toned, rat-a-tat style necessary for the role.

Blanche spent more than an hour showing that Cohen, like Stormy Daniels last week, despises Trump, and this line of inquiry was entertaining if not informative. When he quoted Cohen calling Trump a “boorish cartoon misogynist,” Cohen wielded the same mild and effective rejoinder he used twice earlier: “Sounds like something I would say.” My kids would like to see me in that T-shirt.

Blanche spent a long time depicting Cohen as a publicity hound cashing in on his decision to flip on Trump. Guilty as charged. But Cohen’s unwise decision to make sport of Trump in an orange jumpsuit (and worse) earlier in the trial, while angering both the prosecution and defense, doesn’t relate to the falsification of business records at issue in the case. And Cohen made it clear that he was merely responding in kind to Trump’s childish posts, a few of which jurors have seen more than once. All told, an annoying waste of the jury’s time.

Blanche had trouble finding a rhythm. For instance, he asked Cohen if he had appeared on MSNBC shows anchored by Ali Velshi and Joy Reid. When Cohen said yes, Blanche had no follow-up.

But his real problem is that he has so little to work with. Cohen delivered devastating direct testimony all day Monday and again Tuesday morning, and he has been careful and low-key on cross.

Instead of attacking the prosecution’s case head-on, Blanche has been handcuffed by a client nursing a perverse desire to see Cohen’s insults — and his own — aired in open court.

At around 4 p.m. Tuesday, shortly before court adjourned for the day, Blanche began delving into why other prosecutors have passed on this case. That could be promising for him. But after all the runs the prosecution has already scored, he’ll have to strike Cohen out with the bases loaded to get back into the game.

Michelle Goldberg

Top Republicans Come Face to Face With Trump’s Seamy Past

On a day when Michael Cohen, Donald Trump’s former fixer, testified about the price of loyalty to Trump, a group of Republicans, including House Speaker Mike Johnson, Gov. Doug Burgum of North Dakota and Vivek Ramaswamy, a former presidential candidate, showed up at the courthouse to demonstrate their loyalty to Trump.

Sitting in the courtroom on Tuesday on my first day at the trial, I kept wondering what they were thinking as they heard Cohen, seeming every bit the weary, reluctantly reformed TV gangster, testify about his mafia-like interactions with Trumpworld.

He described how, after his home and office were raided by the F.B.I., Trump encouraged him, both through a “really sketchy” lawyer and through his own Twitter posts, to, in Cohen’s words, “Stay in the fold, stay loyal, don’t flip.” He described how once he decided “not to lie for President Trump any longer,” the then-president publicly attacked him.

Cohen now seems like a man whose life has been essentially wrecked — he went to prison, lost his law license, had to sell his New York and Chicago taxi medallions and is still on supervised release. Though his implosion has been particularly severe, he is far from alone; many people who’ve served Trump, no matter how faithfully, have been ruined in various ways by the experience.

Nevertheless, as Trump runs for re-election, Republicans are climbing over one another to get as close to him as possible. Toward the end of his testimony for the prosecution, Cohen was asked about his regrets.

“To keep the loyalty and to do things that he had asked me to do, I violated my moral compass, and I suffered the penalty,” he said. I’d like to know if Johnson, hearing this, had even a flicker of foreboding.

The Increase in Drowning Deaths Should Be a National Priority

Drowning deaths in the United States rose by more than 12 percent to an estimated 4,500 per year during the pandemic, according to grim new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The increase, from 4,000 per year in 2019, comes as this long-neglected public health crisis is slowly beginning to draw some attention from government policymakers.

“It’s moving in the wrong direction,” the C.D.C. director, Dr. Mandy Cohen, told The Times. The agency said more than half of Americans had never taken a swimming lesson.

The sobering data is an opportunity for President Biden and health officials to finally make drowning prevention a national priority.

Drowning is the leading cause of death for children ages 1 to 4 in the United States and the second leading cause of death by accidental injury for children 5 to 14. Tackling the issue has clear bipartisan appeal and would improve quality of life in every American community.

Despite the obvious need for action, federal, state and local governments in the United States have invested very little to prevent these deaths.

The rise in deaths has caught the eye of former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, whose philanthropy told The Times this week it plans for the first time to direct millions of dollars to drowning prevention efforts within the United States to improve data collection and help fund swimming lessons in 10 states where drowning rates are highest: Alaska, Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Michigan, New York, Oklahoma and Texas.

The planned $17.6 million investment by Bloomberg Philanthropies is modest compared with the $104 million it is spending globally on preventing drownings. But the focus by Bloomberg, whose prominent public health campaigns helped ban smoking in bars and restaurants in New York, could help raise the profile of this issue. Executives at the philanthropy said they planned to work with the C.D.C.

Many Americans of even wealthy backgrounds have lost children to drowning. But drowning is also an issue of equity. Black people and Native Americans are at substantially increased risk of drowning. So are teenage boys. The C.D.C. report found that these trends have continued. In 2020, they said, Black Americans saw the greatest increase in fatal drownings.

Red Cross surveys suggest that a majority of Americans lack basic swimming abilities. With C.D.C. data showing the existence of more than 10 million private pools in the United States and fewer than 309,000 public ones, it’s clear that large numbers of Americans lack access to basic information about water safety, as well as safe places to learn to swim. Instead of a public health issue, drowning is treated as a private matter and swimming as a luxury. To save lives, this needs to change.

David Brooks

Why Trump Is Ahead in So Many Swing States

What do American voters want? The latest New York Times/Siena polls of swing states offer some confusing evidence on this point. Some of the polling results suggest that Americans are in a revolutionary frame of mind: Asked whether the political and economic systems need major changes, 69 percent of respondents said those systems need major changes or should be entirely torn down.

On the other hand, when the pollsters gave voters a choice between a candidate who would bring the country back to normal and one who would bring major changes, 51 percent said they would prefer the back-to-normal candidate and only 40 percent would prefer the major-changes candidate.

So which is it? Is 2024 a change election in which people want someone who will shake things up, or is this a stability election in which people are going to vote for the candidate of order over the candidate of chaos?

Well, different voters want different things. But if I had to write a single sentence that reconciled these diverse findings, it would be this: The people who run America’s systems have led the country seriously astray; we need a president who will shake things up and lead the country back to normal.

When they hear “systems,” I assume voters are thinking of the network of institutions run by America’s elite — corporations, governing agencies, higher education, the news media and so on. If voters believe one thing about Donald Trump it’s that he’s against these systems and these systems are against him.

Voters clearly see President Biden implicated in these systems. The heart of his problem heaves into view when people are asked which candidate will bring about change. Seventy percent of voters said that Trump would bring about major changes or tear down the system entirely if elected. And 71 percent of voters said that little or nothing would change if Biden was re-elected.

In other words, the evidence suggests that the swing voter wants reactionary change, not revolutionary change. The mood suggested by the evidence is angry nostalgia. That would be my explanation for why Trump is so convincingly ahead in most of the swing states.

Trump Told Cohen Disclosure of His Fling Would Be a ‘Total Disaster’

When Michael Cohen took the stand for the first time in Donald Trump’s hush-money trial on Monday morning, he almost accidentally sat down without taking the oath. But after he raised his hand and swore to tell the truth, he seemed to do so.

In dry language, with his impulse-control problems nowhere in sight, he landed blow after blow on the former president.

Cohen, Trump’s former lawyer and fixer, is willing to look like a stooge — pathetically eager for any praise from the boss — to implant in jurors’ minds that even in the absence of incriminating emails, he should be believed because of all the time he spent looking for Brownie points from Trump. When he did so, he was implicating Trump.

Cohen’s testimony about the Playboy model Karen McDougal, who says she had a nine-month affair with Trump, is important beyond Trump describing her to Cohen as “beautiful.” It cemented Trump’s attention to detail, which we’ve heard a lot about already. He constantly asked for updates on the hush money that American Media Inc., publisher of The National Enquirer, was paying at his direction to McDougal, replying, “Great!” or “Fantastic,” when Cohen delivered them.

Cohen’s tape of Trump discussing that deal landed hard when it was played, and not just because it was Trump’s voice talking about “150” — a clear reference to the $150,000 in hush money that Trump — through Cohen and A.M.I. — was originally going to pay McDougal. Trump’s micromanaging, which we’ve heard about for two weeks, came to life in a way that didn’t help him. And when Cohen dissected practically every moment of the call, there was no mistaking the meaning of the brief conversation.

When Cohen told Trump that Stormy Daniels was shopping her story, “Trump was really angry with me,” he said. Trump told Cohen: “‘I thought you had this under control, I thought you took care of this! … Just take care of it!’”