Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Academic writing

- A step-by-step guide to the writing process

The Writing Process | 5 Steps with Examples & Tips

Published on April 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on December 8, 2023.

Good academic writing requires effective planning, drafting, and revision.

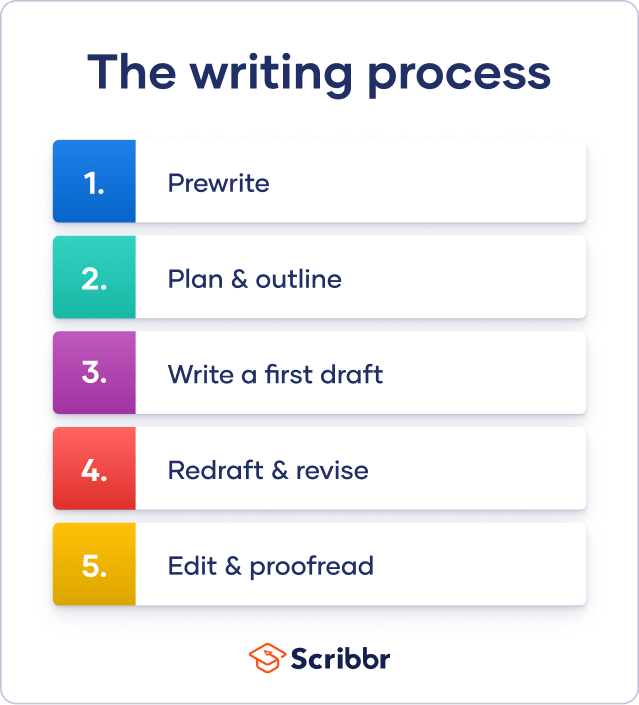

The writing process looks different for everyone, but there are five basic steps that will help you structure your time when writing any kind of text.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Table of contents

Step 1: prewriting, step 2: planning and outlining, step 3: writing a first draft, step 4: redrafting and revising, step 5: editing and proofreading, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about the writing process.

Before you start writing, you need to decide exactly what you’ll write about and do the necessary research.

Coming up with a topic

If you have to come up with your own topic for an assignment, think of what you’ve covered in class— is there a particular area that intrigued, interested, or even confused you? Topics that left you with additional questions are perfect, as these are questions you can explore in your writing.

The scope depends on what type of text you’re writing—for example, an essay or a research paper will be less in-depth than a dissertation topic . Don’t pick anything too ambitious to cover within the word count, or too limited for you to find much to say.

Narrow down your idea to a specific argument or question. For example, an appropriate topic for an essay might be narrowed down like this:

Doing the research

Once you know your topic, it’s time to search for relevant sources and gather the information you need. This process varies according to your field of study and the scope of the assignment. It might involve:

- Searching for primary and secondary sources .

- Reading the relevant texts closely (e.g. for literary analysis ).

- Collecting data using relevant research methods (e.g. experiments , interviews or surveys )

From a writing perspective, the important thing is to take plenty of notes while you do the research. Keep track of the titles, authors, publication dates, and relevant quotations from your sources; the data you gathered; and your initial analysis or interpretation of the questions you’re addressing.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

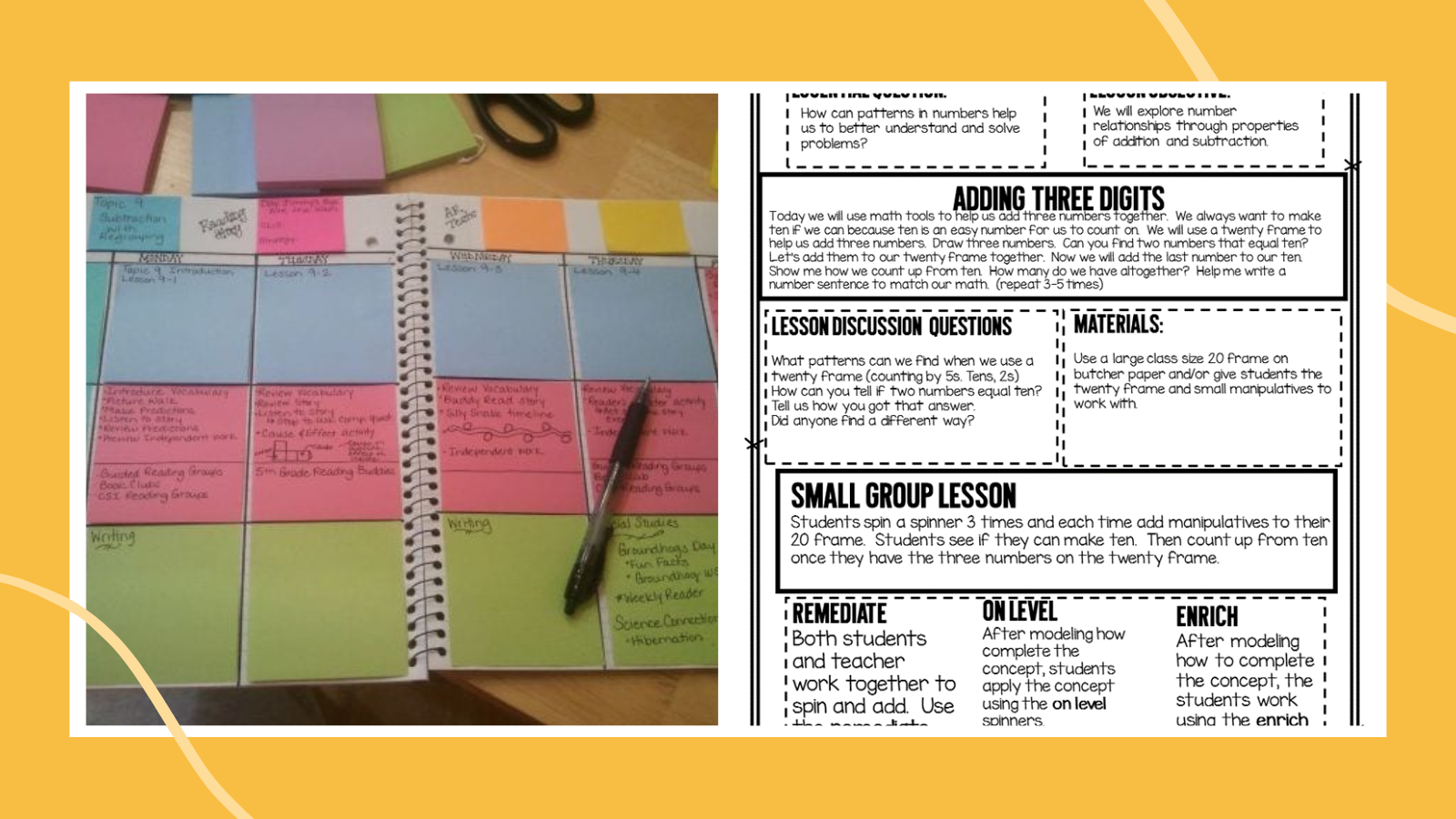

Especially in academic writing , it’s important to use a logical structure to convey information effectively. It’s far better to plan this out in advance than to try to work out your structure once you’ve already begun writing.

Creating an essay outline is a useful way to plan out your structure before you start writing. This should help you work out the main ideas you want to focus on and how you’ll organize them. The outline doesn’t have to be final—it’s okay if your structure changes throughout the writing process.

Use bullet points or numbering to make your structure clear at a glance. Even for a short text that won’t use headings, it’s useful to summarize what you’ll discuss in each paragraph.

An outline for a literary analysis essay might look something like this:

- Describe the theatricality of Austen’s works

- Outline the role theater plays in Mansfield Park

- Introduce the research question: How does Austen use theater to express the characters’ morality in Mansfield Park ?

- Discuss Austen’s depiction of the performance at the end of the first volume

- Discuss how Sir Bertram reacts to the acting scheme

- Introduce Austen’s use of stage direction–like details during dialogue

- Explore how these are deployed to show the characters’ self-absorption

- Discuss Austen’s description of Maria and Julia’s relationship as polite but affectionless

- Compare Mrs. Norris’s self-conceit as charitable despite her idleness

- Summarize the three themes: The acting scheme, stage directions, and the performance of morals

- Answer the research question

- Indicate areas for further study

Once you have a clear idea of your structure, it’s time to produce a full first draft.

This process can be quite non-linear. For example, it’s reasonable to begin writing with the main body of the text, saving the introduction for later once you have a clearer idea of the text you’re introducing.

To give structure to your writing, use your outline as a framework. Make sure that each paragraph has a clear central focus that relates to your overall argument.

Hover over the parts of the example, from a literary analysis essay on Mansfield Park , to see how a paragraph is constructed.

The character of Mrs. Norris provides another example of the performance of morals in Mansfield Park . Early in the novel, she is described in scathing terms as one who knows “how to dictate liberality to others: but her love of money was equal to her love of directing” (p. 7). This hypocrisy does not interfere with her self-conceit as “the most liberal-minded sister and aunt in the world” (p. 7). Mrs. Norris is strongly concerned with appearing charitable, but unwilling to make any personal sacrifices to accomplish this. Instead, she stage-manages the charitable actions of others, never acknowledging that her schemes do not put her own time or money on the line. In this way, Austen again shows us a character whose morally upright behavior is fundamentally a performance—for whom the goal of doing good is less important than the goal of seeming good.

When you move onto a different topic, start a new paragraph. Use appropriate transition words and phrases to show the connections between your ideas.

The goal at this stage is to get a draft completed, not to make everything perfect as you go along. Once you have a full draft in front of you, you’ll have a clearer idea of where improvement is needed.

Give yourself a first draft deadline that leaves you a reasonable length of time to revise, edit, and proofread before the final deadline. For a longer text like a dissertation, you and your supervisor might agree on deadlines for individual chapters.

Now it’s time to look critically at your first draft and find potential areas for improvement. Redrafting means substantially adding or removing content, while revising involves making changes to structure and reformulating arguments.

Evaluating the first draft

It can be difficult to look objectively at your own writing. Your perspective might be positively or negatively biased—especially if you try to assess your work shortly after finishing it.

It’s best to leave your work alone for at least a day or two after completing the first draft. Come back after a break to evaluate it with fresh eyes; you’ll spot things you wouldn’t have otherwise.

When evaluating your writing at this stage, you’re mainly looking for larger issues such as changes to your arguments or structure. Starting with bigger concerns saves you time—there’s no point perfecting the grammar of something you end up cutting out anyway.

Right now, you’re looking for:

- Arguments that are unclear or illogical.

- Areas where information would be better presented in a different order.

- Passages where additional information or explanation is needed.

- Passages that are irrelevant to your overall argument.

For example, in our paper on Mansfield Park , we might realize the argument would be stronger with more direct consideration of the protagonist Fanny Price, and decide to try to find space for this in paragraph IV.

For some assignments, you’ll receive feedback on your first draft from a supervisor or peer. Be sure to pay close attention to what they tell you, as their advice will usually give you a clearer sense of which aspects of your text need improvement.

Redrafting and revising

Once you’ve decided where changes are needed, make the big changes first, as these are likely to have knock-on effects on the rest. Depending on what your text needs, this step might involve:

- Making changes to your overall argument.

- Reordering the text.

- Cutting parts of the text.

- Adding new text.

You can go back and forth between writing, redrafting and revising several times until you have a final draft that you’re happy with.

Think about what changes you can realistically accomplish in the time you have. If you are running low on time, you don’t want to leave your text in a messy state halfway through redrafting, so make sure to prioritize the most important changes.

Check for common mistakes

Use the best grammar checker available to check for common mistakes in your text.

Fix mistakes for free

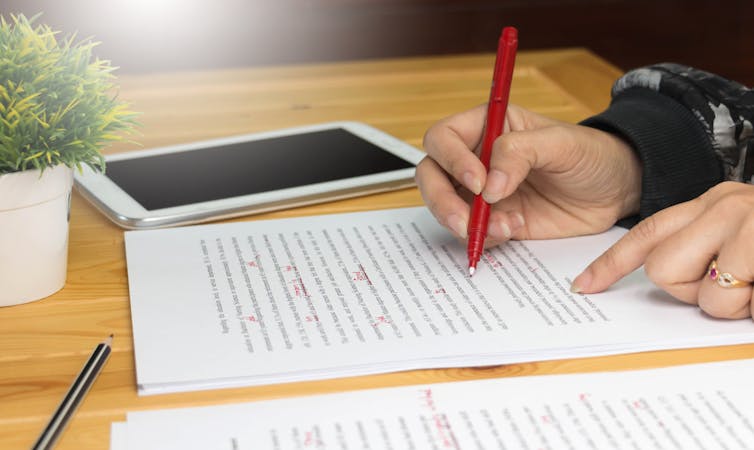

Editing focuses on local concerns like clarity and sentence structure. Proofreading involves reading the text closely to remove typos and ensure stylistic consistency. You can check all your drafts and texts in minutes with an AI proofreader .

Editing for grammar and clarity

When editing, you want to ensure your text is clear, concise, and grammatically correct. You’re looking out for:

- Grammatical errors.

- Ambiguous phrasings.

- Redundancy and repetition .

In your initial draft, it’s common to end up with a lot of sentences that are poorly formulated. Look critically at where your meaning could be conveyed in a more effective way or in fewer words, and watch out for common sentence structure mistakes like run-on sentences and sentence fragments:

- Austen’s style is frequently humorous, her characters are often described as “witty.” Although this is less true of Mansfield Park .

- Austen’s style is frequently humorous. Her characters are often described as “witty,” although this is less true of Mansfield Park .

To make your sentences run smoothly, you can always use a paraphrasing tool to rewrite them in a clearer way.

Proofreading for small mistakes and typos

When proofreading, first look out for typos in your text:

- Spelling errors.

- Missing words.

- Confused word choices .

- Punctuation errors .

- Missing or excess spaces.

Use a grammar checker , but be sure to do another manual check after. Read through your text line by line, watching out for problem areas highlighted by the software but also for any other issues it might have missed.

For example, in the following phrase we notice several errors:

- Mary Crawfords character is a complicate one and her relationships with Fanny and Edmund undergoes several transformations through out the novel.

- Mary Crawford’s character is a complicated one, and her relationships with both Fanny and Edmund undergo several transformations throughout the novel.

Proofreading for stylistic consistency

There are several issues in academic writing where you can choose between multiple different standards. For example:

- Whether you use the serial comma .

- Whether you use American or British spellings and punctuation (you can use a punctuation checker for this).

- Where you use numerals vs. words for numbers.

- How you capitalize your titles and headings.

Unless you’re given specific guidance on these issues, it’s your choice which standards you follow. The important thing is to consistently follow one standard for each issue. For example, don’t use a mixture of American and British spellings in your paper.

Additionally, you will probably be provided with specific guidelines for issues related to format (how your text is presented on the page) and citations (how you acknowledge your sources). Always follow these instructions carefully.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Revising, proofreading, and editing are different stages of the writing process .

- Revising is making structural and logical changes to your text—reformulating arguments and reordering information.

- Editing refers to making more local changes to things like sentence structure and phrasing to make sure your meaning is conveyed clearly and concisely.

- Proofreading involves looking at the text closely, line by line, to spot any typos and issues with consistency and correct them.

Whether you’re publishing a blog, submitting a research paper , or even just writing an important email, there are a few techniques you can use to make sure it’s error-free:

- Take a break : Set your work aside for at least a few hours so that you can look at it with fresh eyes.

- Proofread a printout : Staring at a screen for too long can cause fatigue – sit down with a pen and paper to check the final version.

- Use digital shortcuts : Take note of any recurring mistakes (for example, misspelling a particular word, switching between US and UK English , or inconsistently capitalizing a term), and use Find and Replace to fix it throughout the document.

If you want to be confident that an important text is error-free, it might be worth choosing a professional proofreading service instead.

If you’ve gone over the word limit set for your assignment, shorten your sentences and cut repetition and redundancy during the editing process. If you use a lot of long quotes , consider shortening them to just the essentials.

If you need to remove a lot of words, you may have to cut certain passages. Remember that everything in the text should be there to support your argument; look for any information that’s not essential to your point and remove it.

To make this process easier and faster, you can use a paraphrasing tool . With this tool, you can rewrite your text to make it simpler and shorter. If that’s not enough, you can copy-paste your paraphrased text into the summarizer . This tool will distill your text to its core message.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, December 08). The Writing Process | 5 Steps with Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved June 10, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-writing/writing-process/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to create a structured research paper outline | example, quick guide to proofreading | what, why and how to proofread, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- MyU : For Students, Faculty, and Staff

Writing Across the Curriculum

Ask a question

- Research & Assessment

- Writing Plans

- WEC Liaisons

- Academic Units

- Engage with WEC

- Teaching Resources

- Teaching Consultations

- Faculty Writing Resources

- Designing Effective Writing Assignments

One of the best ways for students to determine what they know, think, and believe about a given subject is to write about it. To support students in their writing, it is important to provide them with a meaningful writing task, one that has an authentic purpose, clear guidelines, and engages students in their learning. In this section, you can read about key principles of assignment design, review examples of effective writing assignments, and use a checklist to guide your own designs. You can also consult with a Writing Across the Curriculum Program team member . We’re happy to think with you about your writing assignment, whether it is in the inkling stage or undergoing a few minor tweaks.

What makes an assignment effective?

A good deal of educational research points to the benefits of writing assignments that exhibit the following features:

Meaningful tasks. A task is given meaning by its relevance to and alignment with the learning aims in the course. What counts as meaningful in one course context might not be meaningful in another. As Eodice, Geller, and Lerner (2016) have shown, meaningful writing assignments do occur across all disciplines and they are typically ones that “offer students opportunities to engage with instructors, peers, and texts and are relevant to past experiences and passions as well as to future aspirations and identities.”

Maximized learning time. As Linda Suskie argues, effectiveness is determined by the “learning payoff,” not by size of the assignment. Will students learn four times as much on an assignment that takes 20 hours outside of class than one that takes 5? Longer research-based assignments and elaborate class activities (mock conferences, debates, poster sessions, etc.) can greatly maximize learning, but there must be an appropriate level of writing and learning time built into the task. Term papers are much more effective when students have time to draft and revise stages of the assignment, rather than turning in one final product at the end.

Logical sequencing. A writing task that includes discrete stages (research, drafting, review, revising, etc.) is more likely to be an effective learning experience than one that only specifies the final product. Furthermore, these stages are more effective when they are scaffolded so simpler tasks precede more complex tasks. For example, a well-sequenced 10-12 page essay assignment might involve discrete segments where students generate a central inquiry question, draft and workshop a thesis statement, produce a first draft of the essay, give and receive feedback on drafts, and submit a revision. Read more about sequencing assignments .

Clear criteria will help students connect an assignment’s relevance to larger scale course outcomes. The literature on assignment design strongly encourages instructors to make the grading criteria explicit to students before the assignment is collected and assessed. A grading scheme or rubric that is handed out along with the assignment can provide students with a clear understanding of the weighted expectations and, thus help them decide what to focus on in the assignment. It becomes a teaching tool, not just an assessment tool.

Forward-thinking activities more than backward-thinking activities. Forward-thinking activities and assignments ask students to apply their learning rather than simply repeat it. The orientation of many writing prompts is often backward, asking students to show they learned X, Y, and Z. As L. Dee Fink (2013) points out, forward-thinking assignments and activities look ahead to what students will be able to do in the future having learned about X, Y, and Z. Such assignments often utilize real-world and scenario-based problems, requiring students to apply their learning to a new situation. For Grant Wiggins (1998) , questions, problems, tests, and assignments that are forward-thinking often:

- Require judgment and innovation. Students have to use knowledge and skills to solve unstructured problems, not just plug in a routine.

- Ask students to do the subject. Beyond recitation and replication, these tasks require students to carry out explorations, inquiry, and work within specific disciplines.

- Replicate workplace and civic contexts. These tasks provide specific constraints, purposes, and audiences that students will face in work and societal contexts.

- Involve a repertoire of skills and abilities rather than the isolation of individual skills.

Feel free to use this assignment checklist , which draws on the principles and research described on this page.

- African American & African Studies

- Agronomy and Plant Genetics

- Animal Science

- Anthropology

- Applied Economics

- Art History

- Carlson School of Management

- Chemical Engineering and Materials Science

- Civil, Environmental, and Geo-Engineering

- College of Biological Sciences

- Communication Studies

- Computer Science & Engineering

- Construction Management

- Curriculum and Instruction

- Dental Hygiene

- Apparel Design

- Graphic Design

- Product Design

- Retail Merchandising

- Earth Sciences

- Electrical and Computer Engineering

- Environmental Sciences, Policy and Management

- Family Social Science

- Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology

- Food Science and Nutrition

- Geography, Environment and Society

- German, Nordic, Slavic & Dutch

- Health Services Management

- Horticultural Science

- Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication

- Industrial and Systems Engineering

- Information Technology Infrastructure

- Mathematics

- Mechanical Engineering

- Medical Laboratory Sciences

- Mortuary Science

- Organizational Leadership, Policy, and Development

- Political Science

- School of Architecture

- School of Kinesiology

- School of Public Health

- Spanish and Portuguese Studies

- Speech-Language-Hearing Sciences

- Theatre Arts & Dance

- Youth Studies

- New Enrollments for Departments and Programs

- Legacy Program for Continuing Units

- Writing in Your Course Context

- Syllabus Matters

- Mid-Semester Feedback Strategies

- Writing Assignment Checklist

- Scaffolding and Sequencing Writing Assignments

- Informal, Exploratory Writing Activities

- 5-Minute Revision Workshops

- Reflective Memos

- Conducting In-Class Writing Activities: Notes on Procedures

- Now what? Responding to Informal Writing

- Teaching Writing with Quantitative Data

- Commenting on Student Writing

- Supporting Multilingual Learners

- Teaching with Effective Models of Writing

- Peer Response Protocols and Procedures

- Using Reflective Writing to Deepen Student Learning

- Conferencing with Student Writers

- Designing Inclusive Writing Assigments

- Addressing a Range of Writing Abilities in Your Courses

- Effective Grading Strategies

- Designing and Using Rubrics

- Running a Grade-Norming Session

- Working with Teaching Assistants

- Managing the Paper Load

- Teaching Writing with Sources

- Preventing Plagiarism

- Grammar Matters

- What is ChatGPT and how does it work?

- Incorporating ChatGPT into Classes with Writing Assignments: Policies, Syllabus Statements, and Recommendations

- Restricting ChatGPT Use in Classes with Writing Assignments: Policies, Syllabus Statements, and Recommendations

- What do we mean by "writing"?

- How can I teach writing effectively in an online course?

- What are the attributes of a "writing-intensive" course at the University of Minnesota?

- How can I talk with students about the use of artificial intelligence tools in their writing?

- How can I support inclusive participation on team-based writing projects?

- How can I design and assess reflective writing assignments?

- How can I use prewritten comments to give timely and thorough feedback on student writing?

- How can I use online discussion forums to support and engage students?

- How can I use and integrate the university libraries and academic librarians to support writing in my courses?

- How can I support students during the writing process?

- How can I use writing to help students develop self-regulated learning habits?

- Submit your own question

- Short Course: Teaching with Writing Online

- Five-Day Faculty Seminar

- Past Summer Hunker Participants

- Resources for Scholarly Writers

- Consultation Request

- Faculty Writing Groups

- Further Writing Resources

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that they will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove their point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, they still have to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and they already know everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality they expect.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Writing Assignments

Kate Derrington; Cristy Bartlett; and Sarah Irvine

Introduction

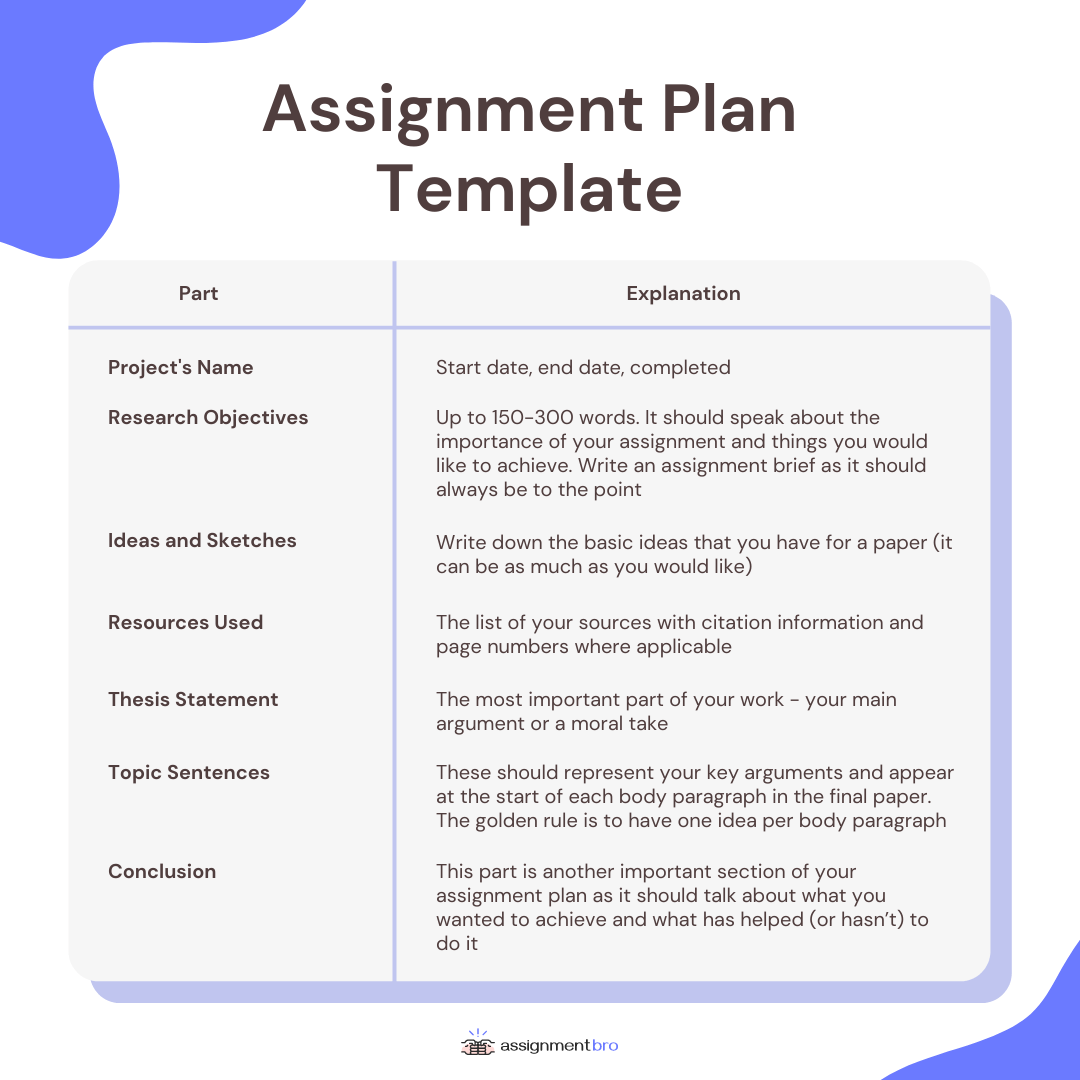

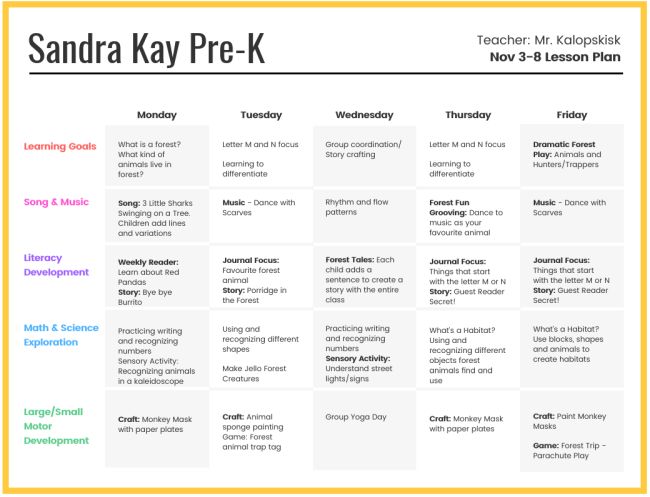

Assignments are a common method of assessment at university and require careful planning and good quality research. Developing critical thinking and writing skills are also necessary to demonstrate your ability to understand and apply information about your topic. It is not uncommon to be unsure about the processes of writing assignments at university.

- You may be returning to study after a break

- You may have come from an exam based assessment system and never written an assignment before

- Maybe you have written assignments but would like to improve your processes and strategies

This chapter has a collection of resources that will provide you with the skills and strategies to understand assignment requirements and effectively plan, research, write and edit your assignments. It begins with an explanation of how to analyse an assignment task and start putting your ideas together. It continues by breaking down the components of academic writing and exploring the elements you will need to master in your written assignments. This is followed by a discussion of paraphrasing and synthesis, and how you can use these strategies to create a strong, written argument. The chapter concludes with useful checklists for editing and proofreading to help you get the best possible mark for your work.

Task Analysis and Deconstructing an Assignment

It is important that before you begin researching and writing your assignments you spend sufficient time understanding all the requirements. This will help make your research process more efficient and effective. Check your subject information such as task sheets, criteria sheets and any additional information that may be in your subject portal online. Seek clarification from your lecturer or tutor if you are still unsure about how to begin your assignments.

The task sheet typically provides key information about an assessment including the assignment question. It can be helpful to scan this document for topic, task and limiting words to ensure that you fully understand the concepts you are required to research, how to approach the assignment, and the scope of the task you have been set. These words can typically be found in your assignment question and are outlined in more detail in the two tables below (see Table 19.1 and Table 19.2 ).

Table 19.1 Parts of an Assignment Question

| Topic words | These are words and concepts you have to research and write about. |

| Task words | These will tell you how to approach the assignment and structure the information you find in your research (e.g., discuss, analyse). |

| Limiting words | These words define the scope of the assignment, e.g., Australian perspectives, relevant codes or standards or a specific timeframe. |

Make sure you have a clear understanding of what the task word requires you to address.

Table 19.2 Task words

| Give reasons for or explain something has occurred. This task directs you to consider contributing factors to a certain situation or event. You are expected to make a decision about why these occurred, not just describe the events. | the factors that led to the global financial crisis. | |

| Consider the different elements of a concept, statement or situation. Show the different components and show how they connect or relate. Your structure and argument should be logical and methodical. | the political, social and economic impacts of climate change. | |

| Make a judgement on a topic or idea. Consider its reliability, truth and usefulness. In your judgement, consider both the strengths and weaknesses of the opposing arguments to determine your topic’s worth (similar to evaluate). | the efficacy of cogitative behavioural therapy (CBT) for the treatment of depression. | |

| Divide your topic into categories or sub-topics logically (could possibly be part of a more complex task). | the artists studied this semester according to the artistic periods they best represent. Then choose one artist and evaluate their impact on future artists. | |

| State your opinion on an issue or idea. You may explain the issue or idea in more detail. Be objective and support your opinion with reliable evidence. | the government’s proposal to legalise safe injecting rooms. | |

| Show the similarities and differences between two or more ideas, theories, systems, arguments or events. You are expected to provide a balanced response, highlighting similarities and differences. | the efficiency of wind and solar power generation for a construction site. | |

| Point out only the differences between two or more ideas, theories, systems, arguments or events. | virtue ethics and utilitarianism as models for ethical decision making. | |

| (this is often used with another task word, e.g. critically evaluate, critically analyse, critically discuss) | It does not mean to criticise, instead you are required to give a balanced account, highlighting strengths and weaknesses about the topic. Your overall judgment must be supported by reliable evidence and your interpretation of that evidence. | analyse the impacts of mental health on recidivism within youth justice. |

| Provide a precise meaning of a concept. You may need to include the limits or scope of the concept within a given context. | digital disruption as it relates to productivity. | |

| Provide a thorough description, emphasising the most important points. Use words to show appearance, function, process, events or systems. You are not required to make judgements. | the pathophysiology of Asthma. | |

| Highlight the differences between two (possibly confusing) items. | between exothermic and endothermic reactions. | |

| Provide an analysis of a topic. Use evidence to support your argument. Be logical and include different perspectives on the topic (This requires more than a description). | how Brofenbrenner’s ecological system’s theory applies to adolescence. | |

| Review both positive and negative aspects of a topic. You may need to provide an overall judgement regarding the value or usefulness of the topic. Evidence (referencing) must be included to support your writing. | the impact of inclusive early childhood education programs on subsequent high school completion rates for First Nations students. | |

| Describe and clarify the situation or topic. Depending on your discipline area and topic, this may include processes, pathways, cause and effect, impact, or outcomes. | the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the film industry in Australia. | |

| Clarify a point or argument with examples and evidence. | how society’s attitudes to disability have changed from a medical model to a wholistic model of disability. | |

| Give evidence which supports an argument or idea; show why a decision or conclusions were made. Justify may be used with other topic words, such as outline, argue. | Write a report outlining the key issues and implications of a welfare cashless debit card trial and make three recommendations for future improvements. your decision-making process for the recommendations. | |

| A comprehensive description of the situation or topic which provides a critical analysis of the key issues. | Provide a of Australia's asylum policies since the Pacific Solution in 2001. | |

| An overview or brief description of a topic. (This is likely to be part of a larger assessment task.) | the process for calculating the correct load for a plane. |

The criteria sheet , also known as the marking sheet or rubric, is another important document to look at before you begin your assignment. The criteria sheet outlines how your assignment will be marked and should be used as a checklist to make sure you have included all the information required.

The task or criteria sheet will also include the:

- Word limit (or word count)

- Referencing style and research expectations

- Formatting requirements

Task analysis and criteria sheets are also discussed in the chapter Managing Assessments for a more detailed discussion on task analysis, criteria sheets, and marking rubrics.

Preparing your ideas

Brainstorm or concept map: List possible ideas to address each part of the assignment task based on what you already know about the topic from lectures and weekly readings.

Finding appropriate information: Learn how to find scholarly information for your assignments which is

See the chapter Working With Information for a more detailed explanation .

What is academic writing?

Academic writing tone and style.

Many of the assessment pieces you prepare will require an academic writing style. This is sometimes called ‘academic tone’ or ‘academic voice’. This section will help you to identify what is required when you are writing academically (see Table 19.3 ). The best way to understand what academic writing looks like, is to read broadly in your discipline area. Look at how your course readings, or scholarly sources, are written. This will help you identify the language of your discipline field, as well as how other writers structure their work.

Table 19.3 Comparison of academic and non-academic writing

| Is clear, concise and well-structured | Is verbose and may use more words than are needed |

| Is formal. It writes numbers under twenty in full. | Writes numbers under twenty as numerals and uses symbols such as “&” instead of writing it in full |

| Is reasoned and supported (logically developed) | Uses humour (puns, sarcasm) |

| Is authoritative (writes in third person- This essay argues…) | Writes in first person (I think, I found) |

| Utilises the language of the field/industry/subject | Uses colloquial language e.g., mate |

Thesis statements

Essays are a common form of assessment that you will likely encounter during your university studies. You should apply an academic tone and style when writing an essay, just as you would in in your other assessment pieces. One of the most important steps in writing an essay is constructing your thesis statement. A thesis statement tells the reader the purpose, argument or direction you will take to answer your assignment question. A thesis statement may not be relevant for some questions, if you are unsure check with your lecturer. The thesis statement:

- Directly relates to the task . Your thesis statement may even contain some of the key words or synonyms from the task description.

- Does more than restate the question.

- Is specific and uses precise language.

- Let’s your reader know your position or the main argument that you will support with evidence throughout your assignment.

- The subject is the key content area you will be covering.

- The contention is the position you are taking in relation to the chosen content.

Your thesis statement helps you to structure your essay. It plays a part in each key section: introduction, body and conclusion.

Planning your assignment structure

When planning and drafting assignments, it is important to consider the structure of your writing. Academic writing should have clear and logical structure and incorporate academic research to support your ideas. It can be hard to get started and at first you may feel nervous about the size of the task, this is normal. If you break your assignment into smaller pieces, it will seem more manageable as you can approach the task in sections. Refer to your brainstorm or plan. These ideas should guide your research and will also inform what you write in your draft. It is sometimes easier to draft your assignment using the 2-3-1 approach, that is, write the body paragraphs first followed by the conclusion and finally the introduction.

Writing introductions and conclusions

Clear and purposeful introductions and conclusions in assignments are fundamental to effective academic writing. Your introduction should tell the reader what is going to be covered and how you intend to approach this. Your conclusion should summarise your argument or discussion and signal to the reader that you have come to a conclusion with a final statement. These tips below are based on the requirements usually needed for an essay assignment, however, they can be applied to other assignment types.

Writing introductions

Most writing at university will require a strong and logically structured introduction. An effective introduction should provide some background or context for your assignment, clearly state your thesis and include the key points you will cover in the body of the essay in order to prove your thesis.

Usually, your introduction is approximately 10% of your total assignment word count. It is much easier to write your introduction once you have drafted your body paragraphs and conclusion, as you know what your assignment is going to be about. An effective introduction needs to inform your reader by establishing what the paper is about and provide four basic things:

- A brief background or overview of your assignment topic

- A thesis statement (see section above)

- An outline of your essay structure

- An indication of any parameters or scope that will/ will not be covered, e.g. From an Australian perspective.

The below example demonstrates the four different elements of an introductory paragraph.

1) Information technology is having significant effects on the communication of individuals and organisations in different professions. 2) This essay will discuss the impact of information technology on the communication of health professionals. 3) First, the provision of information technology for the educational needs of nurses will be discussed. 4) This will be followed by an explanation of the significant effects that information technology can have on the role of general practitioner in the area of public health. 5) Considerations will then be made regarding the lack of knowledge about the potential of computers among hospital administrators and nursing executives. 6) The final section will explore how information technology assists health professionals in the delivery of services in rural areas . 7) It will be argued that information technology has significant potential to improve health care and medical education, but health professionals are reluctant to use it.

1 Brief background/ overview | 2 Indicates the scope of what will be covered | 3-6 Outline of the main ideas (structure) | 7 The thesis statement

Note : The examples in this document are taken from the University of Canberra and used under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 licence.

Writing conclusions

You should aim to end your assignments with a strong conclusion. Your conclusion should restate your thesis and summarise the key points you have used to prove this thesis. Finish with a key point as a final impactful statement. Similar to your introduction, your conclusion should be approximately 10% of the total assignment word length. If your assessment task asks you to make recommendations, you may need to allocate more words to the conclusion or add a separate recommendations section before the conclusion. Use the checklist below to check your conclusion is doing the right job.

Conclusion checklist

- Have you referred to the assignment question and restated your argument (or thesis statement), as outlined in the introduction?

- Have you pulled together all the threads of your essay into a logical ending and given it a sense of unity?

- Have you presented implications or recommendations in your conclusion? (if required by your task).

- Have you added to the overall quality and impact of your essay? This is your final statement about this topic; thus, a key take-away point can make a great impact on the reader.

- Remember, do not add any new material or direct quotes in your conclusion.

This below example demonstrates the different elements of a concluding paragraph.

1) It is evident, therefore, that not only do employees need to be trained for working in the Australian multicultural workplace, but managers also need to be trained. 2) Managers must ensure that effective in-house training programs are provided for migrant workers, so that they become more familiar with the English language, Australian communication norms and the Australian work culture. 3) In addition, Australian native English speakers need to be made aware of the differing cultural values of their workmates; particularly the different forms of non-verbal communication used by other cultures. 4) Furthermore, all employees must be provided with clear and detailed guidelines about company expectations. 5) Above all, in order to minimise communication problems and to maintain an atmosphere of tolerance, understanding and cooperation in the multicultural workplace, managers need to have an effective knowledge about their employees. This will help employers understand how their employee’s social conditioning affects their beliefs about work. It will develop their communication skills to develop confidence and self-esteem among diverse work groups. 6) The culturally diverse Australian workplace may never be completely free of communication problems, however, further studies to identify potential problems and solutions, as well as better training in cross cultural communication for managers and employees, should result in a much more understanding and cooperative environment.

1 Reference to thesis statement – In this essay the writer has taken the position that training is required for both employees and employers . | 2-5 Structure overview – Here the writer pulls together the main ideas in the essay. | 6 Final summary statement that is based on the evidence.

Note: The examples in this document are taken from the University of Canberra and used under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 licence.

Writing paragraphs

Paragraph writing is a key skill that enables you to incorporate your academic research into your written work. Each paragraph should have its own clearly identified topic sentence or main idea which relates to the argument or point (thesis) you are developing. This idea should then be explained by additional sentences which you have paraphrased from good quality sources and referenced according to the recommended guidelines of your subject (see the chapter Working with Information ). Paragraphs are characterised by increasing specificity; that is, they move from the general to the specific, increasingly refining the reader’s understanding. A common structure for paragraphs in academic writing is as follows.

Topic Sentence

This is the main idea of the paragraph and should relate to the overall issue or purpose of your assignment is addressing. Often it will be expressed as an assertion or claim which supports the overall argument or purpose of your writing.

Explanation/ Elaboration

The main idea must have its meaning explained and elaborated upon. Think critically, do not just describe the idea.

These explanations must include evidence to support your main idea. This information should be paraphrased and referenced according to the appropriate referencing style of your course.

Concluding sentence (critical thinking)

This should explain why the topic of the paragraph is relevant to the assignment question and link to the following paragraph.

Use the checklist below to check your paragraphs are clear and well formed.

Paragraph checklist

- Does your paragraph have a clear main idea?

- Is everything in the paragraph related to this main idea?

- Is the main idea adequately developed and explained?

- Do your sentences run together smoothly?

- Have you included evidence to support your ideas?

- Have you concluded the paragraph by connecting it to your overall topic?

Writing sentences

Make sure all the sentences in your paragraphs make sense. Each sentence must contain a verb to be a complete sentence. Avoid sentence fragments . These are incomplete sentences or ideas that are unfinished and create confusion for your reader. Avoid also run on sentences . This happens when you join two ideas or clauses without using the appropriate punctuation. This also confuses your meaning (See the chapter English Language Foundations for examples and further explanation).

Use transitions (linking words and phrases) to connect your ideas between paragraphs and make your writing flow. The order that you structure the ideas in your assignment should reflect the structure you have outlined in your introduction. Refer to transition words table in the chapter English Language Foundations.

Paraphrasing and Synthesising

Paraphrasing and synthesising are powerful tools that you can use to support the main idea of a paragraph. It is likely that you will regularly use these skills at university to incorporate evidence into explanatory sentences and strengthen your essay. It is important to paraphrase and synthesise because:

- Paraphrasing is regarded more highly at university than direct quoting.

- Paraphrasing can also help you better understand the material.

- Paraphrasing and synthesising demonstrate you have understood what you have read through your ability to summarise and combine arguments from the literature using your own words.

What is paraphrasing?

Paraphrasing is changing the writing of another author into your words while retaining the original meaning. You must acknowledge the original author as the source of the information in your citation. Follow the steps in this table to help you build your skills in paraphrasing (see Table 19.4 ).

Table 19.4 Paraphrasing techniques

| 1 | Make sure you understand what you are reading. Look up keywords to understand their meanings. |

| 2 | Record the details of the source so you will be able to cite it correctly in text and in your reference list. |

| 3 | Identify words that you can change to synonyms (but do not change the key/topic words). |

| 4 | Change the type of word in a sentence (for example change a noun to a verb or vice versa). |

| 5 | Eliminate unnecessary words or phrases from the original that you don’t need in your paraphrase. |

| 6 | Change the sentence structure (for example change a long sentence to several shorter ones or combine shorter sentences to form a longer sentence). |

Example of paraphrasing

Please note that these examples and in text citations are for instructional purposes only.

Original text

Health care professionals assist people often when they are at their most vulnerable . To provide the best care and understand their needs, workers must demonstrate good communication skills . They must develop patient trust and provide empathy to effectively work with patients who are experiencing a variety of situations including those who may be suffering from trauma or violence, physical or mental illness or substance abuse (French & Saunders, 2018).

Poor quality paraphrase example

This is a poor example of paraphrasing. Some synonyms have been used and the order of a few words changed within the sentences however the colours of the sentences indicate that the paragraph follows the same structure as the original text.

Health care sector workers are often responsible for vulnerable patients. To understand patients and deliver good service , they need to be excellent communicators . They must establish patient rapport and show empathy if they are to successfully care for patients from a variety of backgrounds and with different medical, psychological and social needs (French & Saunders, 2018).

A good quality paraphrase example

This example demonstrates a better quality paraphrase. The author has demonstrated more understanding of the overall concept in the text by using the keywords as the basis to reconstruct the paragraph. Note how the blocks of colour have been broken up to see how much the structure has changed from the original text.

Empathetic communication is a vital skill for health care workers. Professionals in these fields are often responsible for patients with complex medical, psychological and social needs. Empathetic communication assists in building rapport and gaining the necessary trust to assist these vulnerable patients by providing appropriate supportive care (French & Saunders, 2018).

The good quality paraphrase example demonstrates understanding of the overall concept in the text by using key words as the basis to reconstruct the paragraph. Note how the blocks of colour have been broken up, which indicates how much the structure has changed from the original text.

What is synthesising?

Synthesising means to bring together more than one source of information to strengthen your argument. Once you have learnt how to paraphrase the ideas of one source at a time, you can consider adding additional sources to support your argument. Synthesis demonstrates your understanding and ability to show connections between multiple pieces of evidence to support your ideas and is a more advanced academic thinking and writing skill.

Follow the steps in this table to improve your synthesis techniques (see Table 19.5 ).

Table 19.5 Synthesising techniques

| 1 | Check your referencing guide to learn how to correctly reference more than one author at a time in your paper. |

| 2 | While taking notes for your research, try organising your notes into themes. This way you can keep similar ideas from different authors together. |

| 3 | Identify similar language and tone used by authors so that you can group similar ideas together. |

| 4 | Synthesis can not only be about grouping ideas together that are similar, but also those that are different. See how you can contrast authors in your writing to also strengthen your argument. |

Example of synthesis

There is a relationship between academic procrastination and mental health outcomes. Procrastination has been found to have a negative effect on students’ well-being (Balkis, & Duru, 2016). Yerdelen, McCaffrey, and Klassens’ (2016) research results suggested that there was a positive association between procrastination and anxiety. This was corroborated by Custer’s (2018) findings which indicated that students with higher levels of procrastination also reported greater levels of the anxiety. Therefore, it could be argued that procrastination is an ineffective learning strategy that leads to increased levels of distress.

Topic sentence | Statements using paraphrased evidence | Critical thinking (student voice) | Concluding statement – linking to topic sentence

This example demonstrates a simple synthesis. The author has developed a paragraph with one central theme and included explanatory sentences complete with in-text citations from multiple sources. Note how the blocks of colour have been used to illustrate the paragraph structure and synthesis (i.e., statements using paraphrased evidence from several sources). A more complex synthesis may include more than one citation per sentence.

Creating an argument

What does this mean.

Throughout your university studies, you may be asked to ‘argue’ a particular point or position in your writing. You may already be familiar with the idea of an argument, which in general terms means to have a disagreement with someone. Similarly, in academic writing, if you are asked to create an argument, this means you are asked to have a position on a particular topic, and then justify your position using evidence.

What skills do you need to create an argument?

In order to create a good and effective argument, you need to be able to:

- Read critically to find evidence

- Plan your argument

- Think and write critically throughout your paper to enhance your argument

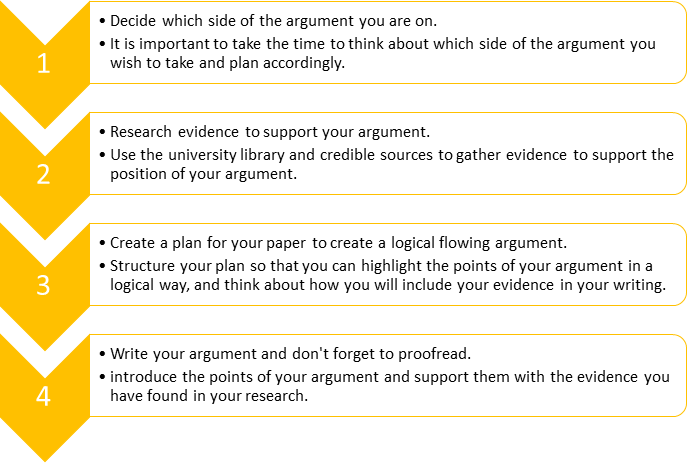

For tips on how to read and write critically, refer to the chapter Thinking for more information. A formula for developing a strong argument is presented below.

A formula for a good argument

What does an argument look like?

As can be seen from the figure above, including evidence is a key element of a good argument. While this may seem like a straightforward task, it can be difficult to think of wording to express your argument. The table below provides examples of how you can illustrate your argument in academic writing (see Table 19.6 ).

Table 19.6 Argument

| Introducing your argument | • This paper will argue/claim that... • ...is an important factor/concept/idea/ to consider because... • … will be argued/outlined in this paper. |

| Introducing evidence for your argument | • Smith (2014) outlines that.... • This evidence demonstrates that... • According to Smith (2014)… • For example, evidence/research provided by Smith (2014) indicates that... |

| Giving the reason why your point/evidence is important | • Therefore this indicates... • This evidence clearly demonstrates.... • This is important/significant because... • This data highlights... |

| Concluding a point | • Overall, it is clear that... • Therefore, … are reasons which should be considered because... • Consequently, this leads to.... • The research presented therefore indicates... |

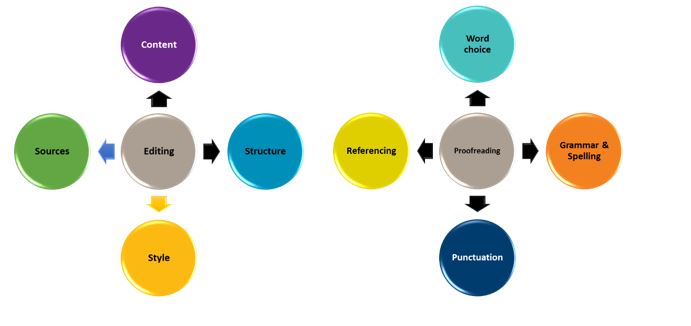

Editing and proofreading (reviewing)

Once you have finished writing your first draft it is recommended that you spend time revising your work. Proofreading and editing are two different stages of the revision process.

- Editing considers the overall focus or bigger picture of the assignment

- Proofreading considers the finer details

As can be seen in the figure above there are four main areas that you should review during the editing phase of the revision process. The main things to consider when editing include content, structure, style, and sources. It is important to check that all the content relates to the assignment task, the structure is appropriate for the purposes of the assignment, the writing is academic in style, and that sources have been adequately acknowledged. Use the checklist below when editing your work.

Editing checklist

- Have I answered the question accurately?

- Do I have enough credible, scholarly supporting evidence?

- Is my writing tone objective and formal enough or have I used emotive and informal language?

- Have I written in the third person not the first person?

- Do I have appropriate in-text citations for all my information?

- Have I included the full details for all my in-text citations in my reference list?

There are also several key things to look out for during the proofreading phase of the revision process. In this stage it is important to check your work for word choice, grammar and spelling, punctuation and referencing errors. It can be easy to mis-type words like ‘from’ and ‘form’ or mix up words like ‘trail’ and ‘trial’ when writing about research, apply American rather than Australian spelling, include unnecessary commas or incorrectly format your references list. The checklist below is a useful guide that you can use when proofreading your work.

Proofreading checklist

- Is my spelling and grammar accurate?

- Are they complete?

- Do they all make sense?

- Do they only contain only one idea?

- Do the different elements (subject, verb, nouns, pronouns) within my sentences agree?

- Are my sentences too long and complicated?

- Do they contain only one idea per sentence?

- Is my writing concise? Take out words that do not add meaning to your sentences.

- Have I used appropriate discipline specific language but avoided words I don’t know or understand that could possibly be out of context?

- Have I avoided discriminatory language and colloquial expressions (slang)?

- Is my referencing formatted correctly according to my assignment guidelines? (for more information on referencing refer to the Managing Assessment feedback section).

This chapter has examined the experience of writing assignments. It began by focusing on how to read and break down an assignment question, then highlighted the key components of essays. Next, it examined some techniques for paraphrasing and summarising, and how to build an argument. It concluded with a discussion on planning and structuring your assignment and giving it that essential polish with editing and proof-reading. Combining these skills and practising them, can greatly improve your success with this very common form of assessment.

- Academic writing requires clear and logical structure, critical thinking and the use of credible scholarly sources.

- A thesis statement is important as it tells the reader the position or argument you have adopted in your assignment. Not all assignments will require a thesis statement.

- Spending time analysing your task and planning your structure before you start to write your assignment is time well spent.

- Information you use in your assignment should come from credible scholarly sources such as textbooks and peer reviewed journals. This information needs to be paraphrased and referenced appropriately.

- Paraphrasing means putting something into your own words and synthesising means to bring together several ideas from sources.

- Creating an argument is a four step process and can be applied to all types of academic writing.

- Editing and proofreading are two separate processes.

Academic Skills Centre. (2013). Writing an introduction and conclusion . University of Canberra, accessed 13 August, 2013, http://www.canberra.edu.au/studyskills/writing/conclusions

Balkis, M., & Duru, E. (2016). Procrastination, self-regulation failure, academic life satisfaction, and affective well-being: underregulation or misregulation form. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 31 (3), 439-459.

Custer, N. (2018). Test anxiety and academic procrastination among prelicensure nursing students. Nursing education perspectives, 39 (3), 162-163.

Yerdelen, S., McCaffrey, A., & Klassen, R. M. (2016). Longitudinal examination of procrastination and anxiety, and their relation to self-efficacy for self-regulated learning: Latent growth curve modeling. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 16 (1).

Writing Assignments Copyright © 2021 by Kate Derrington; Cristy Bartlett; and Sarah Irvine is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Planning and Structuring Assignments

- Book a session

Steps to planning your writing

Understanding the assignment, planning your content, structuring your answer, writing your answer, signposting language.

- Quick resources (5-10 mins)

- e-learning and books (30 mins+)

- SkillsCheck This link opens in a new window

- ⬅ Back to Skills Centre This link opens in a new window

Looking for sessions and tutorials on this topic? Find out more about our session types and how to register to book for sessions. You can view our full and up-to-date availability in UniHub Appointments and Events .