Introduction to Music Theory

Worksheet answers.

STUDENTS! Make sure you complete the assignments yourself before viewing the answers . Mastering these concepts takes time, so don’t cut corners.

Click to Toggle the Answers

Answers to the worksheets for Introduction to Music Theory can be viewed and downloaded by clicking on the links below. This section will be updated regularly as assignments are added.

Chapter 1: Pitch

1.1 – Notes on the staff 1.2 – The treble clef and supplemental worksheet 1.3 – The bass clef and supplemental worksheet 1.4 – Staff systems 1.5 – Octave registers 1.6 – Notes on the keyboard ( part 1 ) ( part 2 ) ( part 3 ) 1.7 – Accidentals 1.8 – Review and Exam 1 1.9 – Appendix 1: Alto and tenor clefs

Chapter 2: Rhythm and meter

2.1 – Introduction to rhythm 2.2 – Pulse, meter, and measures 2.3 – Common time 2.4 – 8th notes and 16th notes 2.5 – Dotted rhythms 2.6 – Ties 2.7 – Rests 2.8 – Dynamics 2.9 – Articulations 2.10 – 2/4 and 3/4 meter 2.11 – Different beat units 2.12 – 6/8 meter 2.13 – More compound meters 2.14 – Review and Exam 2 2.15 – Appendix 2: Asymmetrical meters

Chapter 3: Scales and keys

3.1 – The C major scale 3.2 – Other major scales 3.3 – Diatonic functions of the scale 3.4 – The circle of 5ths 3.5 – Major key signatures 3.6 – The natural minor scale 3.7 – Harmonic and melodic minor scales 3.8 – Major or minor? 3.9 – Modes 3.10 – Review and Exam 3

Chapter 4: Intervals

4.1 – Basic intervals 4.2 – Seconds and thirds ( Part 1 , Part 2 ) 4.3 – Perfect intervals and inversions 4.4 – 6ths, 7ths, and all inversions 4.5 – Intervals in the major scale 4.6 – Intervals in the minor scale 4.7 – Review and Exam 4 4.8 – Appendix 3: Frequency and consonance

Chapter 5: Chords

5.1 – Triads 5.2 – Triad alterations 5.3 – Triads in a key context 5.4 – Inversions and doubling 5.5 – 7th chords in the major key 5.6 – 7th chords in the minor key 5.7 – 7th chord inversions 5.8 – Analyzing arpeggios and doubled notes 5.9 – Non-chord tones 5.10 – Split-bass chords 5.11 – Review and Exam 5 5.12 – Appendix 4: Introduction to jazz chords

Chapter 6: Chord paradigms and song structure

6.1 – From chords to context 6.2 – Keyboard style and part-writing 6.3 – The tonic-dominant relationship 6.4 – The cadential 6/4 6.5 – The pre-dominant 6.6 – Tonic expansion 6.7 – Cadences 6.8 – Introduction to structure 6.9 – Song structure in contemporary music 6.10 – Review and Exam 6

Understanding Basic Music Theory

(25 reviews)

Catherine Schmidt-Jones

Copyright Year: 2013

Publisher: OpenStax CNX

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Rika Uchida, Associate Professor of Piano and Theory, Drake University on 12/30/21

The text covers various concepts in music theory, some of which are fundamental, and others are advanced and complex, such as form. Although it is written in user-friendly manner, I would like to have musical examples for most topics. For... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

The text covers various concepts in music theory, some of which are fundamental, and others are advanced and complex, such as form. Although it is written in user-friendly manner, I would like to have musical examples for most topics. For example, it would be difficult to introduce Rondo form without musical examples; verbal definition of form is simply insufficient, and students do not attain practical knowledge without reference to the music. In short, adding more musical examples and exercises would be beneficial.

Content Accuracy rating: 3

As other reviewers noted, there are numerous errors in musical examples. Notation and terminologies should be authentic, clear, and accurate.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

The text includes concepts that are not often found in most introductory music theory textbooks, such as sound wave, and standing waves in different instruments in Chapter 3 (Physical basics). It can be a useful online resource for those who are seeking for information or definition of particular topics.

Clarity rating: 4

The text is written in user-friendly manner and easy to follow. As stated above, definition of concepts with reference to more musical examples would be practical.

Consistency rating: 3

Some chapters cover concepts at advanced level (e.g., form) with oversimplification. Narrowing down to topics that are at basic level and presenting them comprehensively would make it more consistent.

Modularity rating: 4

Divisions and subdivisions are well organized for most part. I would categorize harmony and form in separate chapters (chapter 5), as this chapter seems incomplete.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The text is well organized in most part, but topics can be organized in a better order. For example, definition (Chapter 2) can be placed as a glossary at the end of the text, and it can be in alphabetical order.

Interface rating: 5

The online interface is easy to navigate. The PDF version worked well for iPad and MacBook.

Grammatical Errors rating: 4

The text is written in user-friendly manner; however, some of the definitions are oversimplified and vaguely written.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

The text covers music of diverse variety of styles and cultural backgrounds. Including standard repertoire as musical examples would be beneficial for some topics (e.g., form).

Balance among verbal definitions, musical examples and exercises could be improved. I would like to have more musical examples, and definition of concepts to be presented with reference to musical examples rather than verbal explanation. Implementation of more exercises would be helpful to use in music courses. I don't see application of Chapter 6.1, ear training in any music courses. Perhaps the author expects instructors to use another textbook for ear training, but the verbal description on this topic seems irrelevant and incomplete.

Reviewed by Derek Shapiro, Assistant Professor/Director of Bands, Virginia Tech on 12/13/21

The text covers all areas of what one would consider basic music theory and is geared truly for the beginner who has had experience in reading music on some level, but desires more comprehensive descriptions of the "why". I especially liked the... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

The text covers all areas of what one would consider basic music theory and is geared truly for the beginner who has had experience in reading music on some level, but desires more comprehensive descriptions of the "why". I especially liked the idea of the "Challenges" section at the end of the text which touched on some commonly found problems amateurs may find when dealing with music.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

I did not find any inaccurate material.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

The book does exactly as it postures itself to do, gives a fundamental explanation of the many aspects of basic music theory. It is slanted towards a western-classical music influence, which may find itself out of date in a few years time, depending on how musicological trends continue.

If I had any negative comment it would be the way things are laid out. The use of color is helpful but the presentation tends to be on the cluttered side. Admittedly, this is often the most difficult thing about a theory book as the layout needs doesn't conform to the way word processing software organizes content. Good use of both general and specific/real-world musical examples.

Consistency rating: 5

The book is consistent in style and layout. Once you understand the how the text is formatted it stays the same.

Modularity rating: 5

Well-laid out with a very clear table of contents.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

Anyone acquainted with a music theory text will understand how and why this book is laid out the way it is. This sticks to that formula which is progressive and scaffolds from the simple to the more complex.

Interface rating: 4

As I mentioned earlier, the layout is a little cluttered but it is more a victim of the way software works rather then the concept.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

Did not find any errors.

Perfectly acceptable in terms of western music theory and the way it has been taught, but may find itself lacking as musicology trends to be more inclusive of cultures outside the western-classical tradition.

This is great resource for students looking for a text to help them refresh or broaden their skills.

Reviewed by Salil Sachdev, Professor, Bridgewater State University on 6/2/21

A good concise introduction to music fundamentals. The textbook contains chapters on various aspects of music, not all of which may be necessary for a basic music theory course. However, instructors have much to pick and choose from and adapt the... read more

A good concise introduction to music fundamentals. The textbook contains chapters on various aspects of music, not all of which may be necessary for a basic music theory course. However, instructors have much to pick and choose from and adapt the material to their specific requirements. As well, the text serves as a springboard for learning beyond the introductory level.

Clarity rating: 5

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

The text is primarily on Western music theory.

Reviewed by Robert Wells, Assistant Professor of Music Theory; Director of Keyboard Studies, University of Mary Washington on 7/4/20

Given that this book is intended to be a fundamentals text (rather than a textbook for the entire music major theory sequence), it is fairly comprehensive. For the mathematically-based theory fundamentals course I teach, which is targeted to... read more

Given that this book is intended to be a fundamentals text (rather than a textbook for the entire music major theory sequence), it is fairly comprehensive. For the mathematically-based theory fundamentals course I teach, which is targeted to non-music majors, this is the perfect text, as it devotes equal attention to fundamentals and quantitative concerns such as tuning systems, interval ratios, and acoustics. Other topics that took this book well beyond the typical fundamentals text were introductory material about reading musical scores (repeat signs, dynamics, tempo markings, etc.), which are of great practical help if you plan to look at musical scores with your class; scales other than major and minor, such as whole-tone, pentatonic, modal, and jazz scales; and non-Western traditions, such as Hindustani music and Balinese gamelan. Additionally, there are links scattered throughout that go beyond the basic content (e.g., pages on tablature, transposing instruments, conducting, etc.). I also appreciated that the author does a good job of addressing common student questions such as, “What stem do I use for chords or groups of notes under the same beam?” or “Why would a composer choose 2/2 over 2/4?” For me, the biggest content omission is that there is no discussion of figured bass. This causes a bit of awkwardness in the chapter on harmonic analysis. For instance, in the analysis exercises in the Cadence section, inverted chords in the solution are labeled with root-position Roman numerals (i.e., no inversion figures). Additionally, if you are looking for part-writing training or post-tonal techniques, you will need to look elsewhere, as these topics are beyond the scope of this text.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

Most of the content is accurate, as far as I could tell. The most significant errors I found were in the section on chord additions/extensions. For instance, the author writes that labeling an added note as “sus” in a lead sheet symbol means it “replaces the chord tone immediately below it,” which is not true in the case of sus2. Moreover, in one of the charts, she labels a Cadd9 chord as “Csus9”. (To be fair, she does fix this label in the chart that follows.) Her explanation of Csus4 vs. C11 is also somewhat lacking, as she does not clarify that the latter has a chordal seventh while the former does not. Finally, in the section on Roman numerals, the author labels all chords very literally using Roman numerals where, in some cases, there should be labels in terms of applied chords/secondary dominants. Aside from these minor quibbles, I had few complaints, and I was impressed with all the physics and acoustics material, which was generally well handled. The bibliographic information scattered throughout also shows that the author has referenced a wide variety of scholarly musical sources in writing this text.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 3

In many ways, this book is very relevant to the needs of today’s musicians, as it is designed to serve as a starting point for musicians with widely ranging goals, from education to composition to performance. For instance, the author includes numerous activities with a music education bent, such as an activity to teach fractions to elementary-schoolers using musical rhythm, musical meter activities relevant to a wide variety of age groups (I used some of these for my college students), and an activity for children on the shape of a melody. There are also discussions of hands-on applications of music theory, such as methods for learning to improvise on one’s instrument and transposing music for a singer. My main complaints regarding relevance and longevity involve some outdated pedagogy and musical examples. In particular, I was bothered by the fact that this text exclusively teaches intervals using the half-step-counting method, which is now widely considered a sort of “last resort” for learning intervals. Inclusion of the white-note and scale methods for interval ID/construction would make this book much more in line with current pedagogy. Additionally, I was disappointed by the sparse musical examples, which are essential for helping students connect with the material. In many chapters, there are only one or two examples drawn from actual music, and when these appear, they are often somewhat dated (for instance, how many 21st-century students will be inspired by selections such as “And the Band Played On” or “The Girl I Left Behind”?). Perhaps this was due to copyright concerns, but it was an issue, nonetheless. On the plus side, the fact that this is an open music theory textbook gives it built-in longevity, as many of these complaints could be addressed in the future.

Overall, the text is very clear, and I have never received complaints from students about having to read the textbook. Sometimes there is a bit too much information, though, especially for beginners, as the author provides a lot of tangential material that may be overkill for a first fundamentals course. The weakest point, in terms of clarity, is probably scales/key signatures section, as key signatures are introduced way before scales/keys have been introduced. Major scales are then introduced several chapters later in terms of whole/half steps, but their relation to key signatures is treated cursorily. Relative minors are then introduced with respect to key signatures, which is confusing since we haven’t fully discussed key signatures yet. Moreover, there is an example of relative major/minor keys that references Eb being a “minor third higher than C,” but intervals haven’t been introduced at this point in the text. In the harmonic analysis section, there is no explanation of Roman numerals for seventh chords; the author simply begins using them. Finally, while there are good strategies for finding the key of a piece, there is no demonstration of harmonic analysis, which would have clarified the abstract suggestions. These points perhaps sound more critical than I intend, for by and large, the book is clearly and lucidly written.

Consistency rating: 4

The book seems to be mostly consistent, although the order of topics was sometimes illogical (see Organization/Structure/Flow below). When teaching with this book, I found myself having to jump around and assign readings out of order. However, the hyperlinks between different sections of the book are very helpful in preserving consistency between different parts of the text. The most concerning inconsistency was between the online and PDF/EPUB editions of the book, as chapter numbering and even some of the written material differs slightly. Thus, I had to be very explicit about which edition I was referring to when assigning readings.

The modularity factor is strong. In teaching using this text, I found it very easy to jump around between pitch/scale/harmony topics, rhythm/meter topics, and acoustics material. For instance, I was able to cover the first half of the rhythm/meter chapter early in the course, and came back to the latter, more advanced half of the chapter later in the course after introducing triads.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 3

Overall, a well-organized text, besides the aforementioned differences in organization between editions. However, topics are sometimes presented in a strange order. For instance, key signatures and the notion of major keys are introduced very early, before a scale has even been defined, as discussed above. While introducing the intuitive notion of key signatures this early was fine (i.e., a symbol that tells you which notes to play sharped or flatted throughout a piece), learning to identify the “key” was too abstract this early on (how can students understand what a key is if they don’t know what a scale is?). Relative minor keys are then introduced, making things even more abstract. Similarly, the notion of enharmonic keys/scales is introduced before the scale chapter. It also bothered me that enharmonic chords/intervals are introduced before students have any conception of what a chord/interval is. A careful instructor can get around these issues by simply skipping the confusing material and coming back to it later, but this does create some extra work for an instructor who wants to use this book.

Interface rating: 3

The online interface seemed to be the most user-friendly. The EPUB file worked well on my iPad, but had different chapter numbering from the online version (as previously noted). Many students liked the PDF version, as it could be used offline on just about any device, but hyperlinks in the PDF aren’t active. I ended up copying important links into our LMS when listing each day’s reading assignments, in case people were using the PDF/print version. I loved the links in the online and EPUB editions, which made the text very interactive. However, the audio for some examples included loud hissing or was very quiet, and some examples you have to directly download to hear. There were also broken links scattered throughout the text. I will say that the built-in exercises were helpful, but I ended up supplementing these with my own homework exercises.

I did not notice any grammatical errors, although there did seem to be a discrepancy between editions regarding “staffs” vs. “staves” in the first chapter.

The text references a wide variety of styles, including Western classical music, Indian classical music, Medieval music, popular music, and jazz. Hindustani music and Balinese gamelan music are discussed in some depth, which creates a more global perspective than most theory books exhibit. Additional musical examples, especially from the last few decades, could make the text even more culturally relevant, as most of the material is presented using out-of-context scales, chords, etc.

While not perfect, this textbook works very well as a completely free music theory text (and let’s face it—fundamentals texts can be very expensive). I would highly recommend it for a music theory for non-music majors course, as students won’t have to buy an expensive book they’ll never use again. Instructors should just be aware that the most effective use of this book is probably not in order, chapter by chapter, and the instructor will have to plan carefully before the semester begins to determine appropriate topics to include, omit, and reorder. Despite the book’s shortcomings, it is extremely valuable as one of the few open textbooks in music theory.

Reviewed by Matthew Svoboda, Music Instructor (Music Theory, Keyboard Skills, Choir), Lane Community College on 6/18/20

This music theory concepts taught are roughly equivalent to those covered in Fall term of the three-term Music Theory course I teach at Lane Community College (LCC). I couldn't use this book for that course because it doesn't go into enough depth... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 3 see less

This music theory concepts taught are roughly equivalent to those covered in Fall term of the three-term Music Theory course I teach at Lane Community College (LCC). I couldn't use this book for that course because it doesn't go into enough depth on subjects such as part writing, counterpoint, resolving chordal dissonances, etc., which I need to cover in the sequenced course I teach. That being said, I do think this would be a fine resource for a Music Fundamentals course. Also, there is some excellent information in chapter 7 on Ear Training, Tuning Systems, Modes and Ragas, and Transposition which far exceeds what is found in the textbook I currently use. This information is very valuable and I could see referring my students to it in the future.

Overall, I found the book to be accurate. However, I found the some information on intervals, sharps and flats, pentatonic scales, phrases, and the circle of fifths to be less than clear. Also, some of the musical examples presented for understanding meter were largely jazz-centric and not simple or straightforward enough for beginners or were classified incorrectly. I think this section could be improved by finding more straightforward listening examples that are more varied (not so often jazz centric.)

Generally speaking, the book's content is not obsolete. It seems that any improvements/updates could be done easily. One update that I think would be helpful would be to go beyond approaching interval identification by counting half steps so that students could learn to identify intervals without merely counting in this way.

The prose is clear and accessible. It does not rely heavily on overly "academic prose" and, for the most part, explains concepts clearly and sequentially.

I found the book to be internally consistent in terms of terminology and framework

The book is organized well and could be taught in smaller sections or modules.

The book is organized well and it is easy to navigate through various topics. I appreciate the searchable index, which I found very helpful.

I appreciated the links to musical examples, theory problems/solutions, and outside resources. Occasionally, some of the links presented in the book no longer opened as intended. These could be fixed in an update.

I did not find any grammatical errors in the book.

This book makes the point that a lot of the traditional music theory texts and terminology in use are Western/Euro centric. It does a nice job of introducing this point of critical thinking to students. While the Western/Euro centric approach is it's main focus, the the book does reference some other kinds of music/music traditions from around the world.

I appreciate this book and plan to use some of its contents in the future, particularly the material from Chapter 7: Ear Training, Tuning Systems, Modes and Ragas, and Transposition.

Reviewed by Craig LiaBraaten, Music Department, Mesabi Range College on 5/18/20

The text is "too complete" for a beginner level study of music theory. Much of the text can be deleted with no ill effect, for example Chapter 3 pp.95-116 and Chapter 6 pp. 218-258. read more

The text is "too complete" for a beginner level study of music theory. Much of the text can be deleted with no ill effect, for example Chapter 3 pp.95-116 and Chapter 6 pp. 218-258.

There are numerous errors and omissions, and other reviewers have correctly noticed a bias versus guitar players, where the author uses condescending tone on several occasions. Errors include listing the types of musical texture out of order: in order of complexity it should read 1. monophony 2. heterophony 3. homophony 4. polyphony. In addition, the definition of non-western music fails to recognize non-European styles in the western hemisphere. On p. 144 the statement "always classify the interval as it is written; the composer had a reason for writing it that way" is bad advice; rather this passage should read something like: "always use correct spelling for intervals, scales and triads."

All throughout the text, more current musical examples than art music of the 18th and 19th centuries should be cited to inspire and captivate the young reader. One other example, the content would be more relevant and interesting to beginner-level college students if the author emphasized references to topics such as "The Nashville System" and its impact on studio and recording musicians when discussing Roman Numerals.

Clarity rating: 3

The writing style is verbose - which frankly is not at all appealing to college-age students whose available time (due to work study and other commitments) is at a premium. The book should be edited and condensed by deleting and re-wording the superfluous language.

Consistency rating: 2

The text is consistently inconsistent. What is lacking is a glossary to tie the book together. The author made attempts at this (pp. 71-72, 83-86, 201-202, 209), but what is needed is to have an alphabetical listing (with cross-references) that includes every necessary term in the whole book.

Modularity rating: 3

The author has divided the chapters into sections, but the overall effect is too many words. Again lengthy explanations are unnecessary. Get to the point. Repeat the point. Move on.

The text should be re-organized into focused chapters of shorter length, each of which cover the single subject more concisely. A minimalist approach to writing style and a logical succession of chapter titles would help, instead of so many cross-references which usually take the reader hopping throughout the book. Sidebars with definitions can cut down this busywork.

Navigation problems include the references every chapter to citations in other chapters, which has the student leap frogging unnecessarily. Smart use of sidebars can minimize this interruption. The author does not need to "tie everything together".

The author's use of colloquial writing is an annoyance. The author is attempting a friendly discourse but it contradicts the lengthy verbose writing style everywhere else. While not technically grammatically in error, the end result is incongruent, wasting valuable time for any student (who may be working two jobs to help pay for their college textbooks).

When using foreign words and providing a pronunciation, make sure it is correct. For example: mezzo is not pronounced with a "t", but rather "MED-zo", using the thick Italian T which sounds to the American ear more like a D. Similarly fortissimo is not pronounced TISS as is suggested, but "for-TEE-see-moh". This may well offend any serious student of Latin or Italian.

Page 7 the author mentions Bass and Treble clef, but nowhere mentions F-clef or G-clef. Pages 13-14 are a good start; author needs to elaborate. Page 23 regarding the term "enharmonic" the author missed the opportunity to discuss CORRECT SPELLING with regard to intervals and scales (and later on, with triads). Page 29 author states: "may connect the notes that are all in the same beat" instead of teaching the student the correct approach is to "beam the beats". Page 42 missed the chance to discuss "anacrusis". Page 51 missed the definition of "rubato" as "steal time". Page 59 missed clear definitions of Legato (notes long and connected), Staccato (notes short and separated), and in between Portato (notes long but separated). Page 79 the quotation from the "Chorale" symphony contains an error at the end of line 3; the "E" is syncopated and tied to the next measure in the double bass solo. Page 128 missed the chance to teach that major scales are built from two identical TETRACHORDS separated by a half step. Page 153 the Circle of 5ths Ascends to the Right and Descends to the Left (it is an error to call the flat keys the "circle of 4ths"). Page 156 missed the chance to teach the Greek word "chromos" - meaning "all colors" - as the basis for "Chromatic Scale". Page 157 did not discuss "anhematonic pentatonic scale" - by definition, a five-note scale that has NO half-steps. P. 179 missed the opportunity to teach that, in a major and minor triad, it's the BOTTOM 3rd that names the triad. Fun reading. Best wishes.

Reviewed by Juliana Han, Assistant Professor, Augustana College on 6/26/19

This book is intended to cover the "bare essentials" of music theory, such as those covered in a fundamentals or prerequisite course at a high school or college level. The index includes the necessary topics at that level. However, the text... read more

This book is intended to cover the "bare essentials" of music theory, such as those covered in a fundamentals or prerequisite course at a high school or college level. The index includes the necessary topics at that level. However, the text emphasizes definitions and explanations, rather than exercises and examples, which makes it an insufficient text for the beginner learner.

The content is carefully written. However, in an attempt to be conversational and accessible, the author writes in oversimplifications that border on the inaccurate or misleading. Examples of this can be found in chapter 3.8 (Classifying Music), which defines entire eras of music or fields of musicological study (e.g., Western, non-Western, world music, classical music) with unwarranted certitude. I would not recommend anyone utilize this chapter.

Because it covers the most basic concepts, there is no issue with content becoming obsolete.

The book's strength is its conversational, accessible writing style. It is also clearly organized, and terms are highlighted and defined. In the online version of the text, hyperlinked terms make finding definitions easy.

The book is internally consistent in terms of terminology and framework.

Because of the clear division and subdivision of topics in the book's index, it is easy to identify modules relevant to a particular topic.

The book is organized clearly into topics and subtopics. The exception is Chapter 3 (Definitions), which only has one subheading each for such substantial topics as harmony and counterpoint. Even given that this is a basic text, more space could have been devoted to these topics, at the expense of others (e.g., tuning systems) that are not as useful for the beginning musician.

The online interface, hosted on the OpenStax CNX network, works fine.

The book is carefully edited.

Cultural Relevance rating: 2

In attempting to be basic and brief, the book does a disservice to the topic of music in non-Western cultures. For instance, the author states in Chapter 3.8 (Classifying Music): "The only easy-to-find items in [the non-Western classical] category are Indian Classical music, for example the performances of Ravi Shankar." This statement is unnecessarily definitive and narrow; the author could instead suggest recommendations and further reading in a less opinionated way. Another statement that generalizes to the point of misrepresentation is this statement: "If you live in a Western culture, it can be difficult to find recordings of non-Western folk music, since most Western listeners do not have a taste for it." Perhaps omitting this topic altogether would strengthen the credibility of this book, since it is often covered in history or other survey courses.

The author should be commended in attempting to create a very readable, organized, and accessible text to introduce new musicians to the most important topics. However, while some content may be useful as background reading at the most basic level, the book does not lend itself to use within a course. The language used is too general to be used in an academic setting, and the lack of exercises, exhibits, and musical examples leave the reader with little path to true comprehension or mastery of music theory skills. Perhaps the largest reason this book is unsuitable for use in a course is that its focus is misaligned to most music theory sequences. The book spends significant space on topics in the scientific basis of music, such as tuning systems, the physical basis of sound, and mathematical derivations. While these topics may be germane to the author's personal interests and training, they are not very important in the early stages of study for applied musicians such as those the author lists on the very first page of her book: "[a] trumpet player interested in jazz, a vocalist interested in early music, a pianist interested in classical composition, and a guitarist interested in world music ." Surely, a deeper look at harmony and counterpoint would be more useful. Overall, this text may be most useful simply as a glossary for definitions of musical terms.

Reviewed by Christopher Cook, Lecturer in Music, Oakland City University on 1/10/19

This book does include an index of terms, which can be quite helpful. It doesn't quite cover as much as is normally covered in a single text for music theory instruction in many college courses. Some topics are discussed well enough, while others... read more

This book does include an index of terms, which can be quite helpful. It doesn't quite cover as much as is normally covered in a single text for music theory instruction in many college courses. Some topics are discussed well enough, while others leave or gloss over standard sections. In other cases, the author chooses topics either adjacent to or nearly unrelated to standard music theory texts. i.e. music physics

The notation section, as others have reviewed, is considerably longer than any other theory text I have read. Indeed, I thought everyone was overstating the issue a bit until I checked it for myself. Far too long, with portions that could have been incorporated into other chapters in the book with ease.

The book is quite accurate. The information provided seems well researched and factual.

Considering the topic, most of the elements in a music theory text will remain relevant for a long period of time. Some texts include examples of music that are very current, but do not become irrelevant for those current examples. This book does a fine job of showing information that seems well researched with recent studies and long-established theory techniques.

I found the majority of the text very easy to understand, with exceptions during the physics chapter where a few of the sections were a bit unclear. Considering the content of this text and that it is intended as an introductory source for beginning students, I believe complete clarity should be the goal.

The terms and concepts presented in this text are consistent throughout.

While sections of this text could be subdivided for use in coursework, substantial page lengths on the very first chapter, along with the nearly as lengthy second chapter, cause this to rate lower. Those first two chapters are so long I know my students would despair any reading assignment solely on the basis of length.

As stated earlier, the definitions and terms presented in Chapter 2 could easily have been and should perhaps have been pieced out to different chapters covering those topics. I do not see a purpose why they should all be grouped together. Additionally, the break between learning about notation to then wait for two more chapters to learn about Notes and Scales seems illogical in the extreme.

No noticeable defects in the interface. Navigation would benefit from links to jump to chapters, but otherwise no issues.

I did not notice any grammatical errors.

The text is not culturally insensitive in any way, but does lack inclusion of non-Western music techniques. Considering some of the side topics presented in the text, inclusion of non-Western music would not be unfeasible to include.

Reviewed by Sarah Muehlbauer, Doctoral Student/Teaching Assistant, James Madison University on 11/17/18

I thought that this textbook covered too much for a music appreciation/intro to music theory non-music major course if the students had little to no background whatsoever in music reading, but far too little for any music major music theory... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 2 see less

I thought that this textbook covered too much for a music appreciation/intro to music theory non-music major course if the students had little to no background whatsoever in music reading, but far too little for any music major music theory sequence. For a music major, it would not be able to be used beyond the first semester of the music theory sequence and much of the first 90 pages would likely be skipped by music majors who already know how to read music, and typically schools adopt a textbook set that covers 3-5 semesters of music theory in the music major theory sequence. The textbook spends so much time on notation (60 pages) plus “definitions” (another 30+ pages), so 90+ pages is spent on introductory material, which would really only be helpful for someone who is just now learning to read music, so I cannot really see this effectively being used. A music major fundamentals course (prior to Theory I) would not need quite that much on notation, but too detailed for a non-music major music appreciation course.

This book goes on to spend a significant amount of time on tuning, harmonic series and acoustics, which would most likely be overwhelming to a non-music major. These topics are not always even included in standard music theory textbooks for music majors, or if they are, it does not have much time spent on it. Those topics are generally pretty confusing to freshmen/sophomores, even for music majors and I would not call them “basic” music theory, unless just introducing them in a few paragraphs, but this book spends half/full chapters/long sections on those topics.

For a music major theory sequence, it is missing a ton of expected topics (voice leading, part writing, secondary/applied chords, modal mixture, phrase model tonic-predominant-dominant progression, figured bass, non-chord tones, far too little on Roman numbers/analysis, modulation only gets a paragraph, sequences, an introduction to 20th century theoretical analysis and other topics, etc.), so it would not be usable for that. This book takes 136 pages in until it even gets to talking about intervals!

The book, however, does include a lot of definitions throughout the text, but at times can be overwhelming with just pages and pages of definitions without examples—just text, like a research paper.

The text includes a decently well detailed index at the end but no glossary.

It has links to an online website with more information, which is a good idea.

Overall, for the topics it chooses to present (although it lacks many topics or spends too much/too little time on many), it is mostly accurate as far as I could tell, but did find a handful of errors in my look-through of the book. My guess is there is more if you read it word for word. While I’m sure I missed some, here are the errors I found: • Double flat symbol is inaccurate- the two flats are on top of each other, rather than right beside each other (pg. 18) • Enharmonic scale example is technically “accurate,” but very poor in truly explaining it—uses E-flat major and D-sharp major scale as its example of enharmonic scales—do we really ever use D-sharp major, a scale with F-double sharp? Why not use a “real” example, such as G-flat and F-sharp major as an enharmonic scale? That would be much less confusing to someone reading this for the first time (pg. 24) • The meter/beats section (with duple simple, duple triple, etc. meters) ignores divisions of the beat—should have a chart for this, which is much clearer in other theory texts I’ve seen (pg. 37). • The suggested list of pieces to listen to for texture examples is not bad, and somewhat useful, but not the best examples for a student first learning about this—this could be easily improved (pg. 82). • Octaves- labels them as C1, C2, etc. on a piano which is correct, but then says, “many musicians use Helmholtz notation” system of “CC, C, c, c1, cii,…” (pg. 119-120) and is not a basic understanding of this • Scale degrees are simply listed as numbers under the scale (“1, 2, 3,…”) instead of with the little carrot-type symbol above them to indicate that they are a scale degree and not just a number (pg. 190) • Chord labeling (pg. 198)—ignores mentioning secondary dominants, and chose poor examples for Roman numeral chord analysis in a traditional textbook sense)

I don’t see relevance as a huge issue with a music theory textbook presenting “basic” or standard concepts. These don’t really change. If it was a textbook on 21st century or more modern music, that may be more of an issue.

The textbook is generally pretty clear in its explanations, although a bit wordy at times. It has long paragraphs of text sometimes without having any examples or anything to break up the textual information. It does explain all terminology/vocabulary words and has all of them bolded, which I found helpful. It seemed very definitions-based.

While there are other issues with this textbook, it is very consistent in its formatting. Terms are bolded, examples contain red and blue color highlighter, and sections are organized with headings. I found the “section citations” useful to go back if you need to, which I would say is incredibly helpful to a student rather than flipping through fretting when you forget something and going “now where was that information on inverting intervals again?” (i.e.: within the text for a particular topic when it references a formerly discussed topic, it puts “Section 1.2.3” in parentheses if you need to go back and review that information; it has basically in-text citations of topics rather than having to look at the index for a previously discussed topic).

Although the formatting is consistent with colors and all, I found it to be literally very “black and white,” and it could use some color or graphics to spice it up and keep a student interested.

Modularity rating: 2

The text is divided into a copious amount of sections within a chapter. That said, I think it would benefit from a greater number of chapters and lower number of divisions within each chapter. There are only 6 chapters within 270+ pages, which creates lengthy chapters. They are divided into very small sections, but the large number of divisions within a long chapter creates confusion when you have headings like 1.1, then 1.1.1, 1.1.1.1, 1.2, 1.3.1.2, 1.5.2.3, etc. (you get the idea)—too many decimal points for these mini-sections.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 2

Besides comprehensiveness or usefulness in a music major theory vs. non-major course, organization is the biggest drawback with this textbook.

60 pages on music notation….and another 30 pages on “definitions.” Harmony, form, cadences, and analysis together only comprise about 40 pages, and notes, scales, half/whole steps, and intervals together only get about 40 pages. I don’t understand this division of pages, unless you’re intending it for someone who does not read music, but then (as mentioned in “Comprehensiveness”) it would be too detailed in the latter sections on tuning, acoustics, and harmonic series for someone just learning to read music in the same semester. Acoustics is put before chords and scales, which I don’t think is needed first for a beginner. It will likely confuse them.

The book is more than half way through before it mentions key signatures and circle of 5ths. Acoustics and harmonic series are discussed before intervals and key signatures in a “basic” book. It has very long chapters (40-70 pages) with a copious number of subheadings rather than shorter chapters and less confusing subheadings (see “Modularity” comments). More of this supposedly “basic” book is devoted to acoustics, tuning, temperament, and harmonic series than to chords, intervals, harmony, and form. Form only gets about 6 pages. Scales are all mushed together, including pentatonic, 12 tone, whole tone, etc. with the more basic major and minor scales. The book is 175 pages in before harmony and triads are discussed (in other standard theory texts, I’ve seen this be about 30-80 pages in, for comparison). Transposition isn’t discussed until the very end, and the first suggestion is to “avoid it” if possible (pg. 242), yet transposition is mentioned in passing (pg. 157) before it is discussed later. Modulation only gets 2 paragraphs. Roman numerals are not thoroughly explained to do harmonic analysis if you did not already know this. Counterpoint only gets a short paragraph. Cadences are only very basically explained.

Ear Training is at the end and is not a thorough enough explanation to begin to learn that.

Some of this was mentioned in “Comprehensiveness,” but, in regarding use for a music major: the book’s organization lacks information on voice leading, part writing, figured bass, non-chord tones, chromatic chords/altered/applied chords (secondary dominants & secondary leading tones), modal mixture, phrase model (tonic-predominant-dominant phrase analysis), sequences, or an introduction to 20th century theoretical analysis.

I did not find errors or distortion of images/charts. My main issue with its presentation was the section headings and all the decimal points (under “Modularity”). I did not find the book’s text to be crammed in and was decently well spaced out on the page to read. However, I would appreciate greater variety of examples to keep the reader from getting bored. It does not have much other than examples with the picture of a keyboard or staff lines. I would also like to see something other than black text with red/blue text on examples to read, which are the prevailing colors and seems very much like a research paper to read since it has no color backgrounds or anything else to look at (very little else, maybe 2-3 pages had something else). Other pictures, graphics, charts, colors, text backgrounds, etc. would be useful to aid in understanding and keep a student more interested in reading.

I found it to be relatively free of errors. I have found wording/grammatical errors in expensive printed textbooks before, so I could forgive a few minor errors if the text is otherwise readable. This text seemed pretty good in that regard, other than some minor issues regarding word order or lacking spaces between some words, but you can understand it without significant problems. Some of the text/long paragraphs could be cut down, however.

I found no issues with this. (Similar to “relevance,” I don’t think cultural issues are a big issue in music theory textbooks, unless it had inaccurate examples for ethnic music/techniques.)

I found “Understanding Basic Music Theory” by Catherine Schmidt-Jones to be an average textbook. It does average or above in regard to accuracy of content, relevance, clarity, consistency, grammar, and cultural issues, but I found moderate problems with interface and modularity and discovered significant problems to be in regard to comprehensiveness/intended audience and organization. My review and opinions are based on what I know of standard music theory textbooks, which come from my own undergraduate theory courses, graduate level work in the pedagogy of music theory, and my own teaching as a DMA student.

I liked the worksheets at the ends of chapters to give the student a “trial run” on the topics, but again would prefer a greater number of chapters that are shorter compared to fewer chapters that are super long, and then insert mini worksheets at the ends of each chapter, or within a chapter.

At this point, I still see a value in purchasing a traditional textbook, if I am comparing this with many of the well-known, standard theory textbooks that I have looked at before.

Reviewed by Jacob Lee, Adjunct Professor, Southern Utah University on 6/19/18

For a book on basic music theory, this textbook is quite (if not excessively) comprehensive, covering much of what should or could be covered in a Theory Fundamentals or Remedial Theory course. read more

For a book on basic music theory, this textbook is quite (if not excessively) comprehensive, covering much of what should or could be covered in a Theory Fundamentals or Remedial Theory course.

The text approaches music theory from a physical (sound waves, overtones, and other physical science) and world perspective (attempting to integrate aspects of jazz and non-western music with typical western music theory). The content appears to be mostly error-free with a few exceptions that I found:

- Minor grammatical issues: nothing too serious. My favorite example, though was on pp. 28: "If a note does not have head...". - Theoretical disagreements that might be addressed: pp. 37: in Figure 1.53 the text says "how many downbeats in a measure". For consistency, the author could use what they wrote in Figure 1.55: "Beginning of beat". The argument that there are 4 downbeats in a 4/4 measure is misleading - there should be one downbeat per measure, the other beats being "weaker". Perhaps the author could say: "How many beats in a measure". Some small mention of hypermeter might do well here.

By involving non-Western music, jazz, and popular music alongside Western classical music, the text provides a resource that is relevant in modern society at large. Updates undoubtedly will need to occur as time goes on, but any relevant music theory book will have to do so.

Clarity rating: 2

Although the text often provides succinct definitions for musical terms, it does tend to be somewhat on the verbose side. With music being a somewhat difficult subject to capture verbally, I would have appreciated more visual and audio examples.

The formatting of the text could be improved so that it is more clear what is to be gained by reading the text (ie more use of bold and/or italic text; summary sections at the beginning or end of chapters; short definitions of vocabulary in the margins).

The text's framework and terminology is mostly consistent (see "accuracy" section for an example where the book is somewhat inconsistent).

The text, although at times quite wordy, are divided into units that could easily be addressed (perhaps at times with some pre-assigned reading) within a typical class period.

The flow of this text is where I take the most issue. Beginning with the chapter on notation requires the reader to look ahead from nearly every section in the chapter to fully understand each concept. Some examples: the section on sharps/flats (1.1.3) is addressed well before the section on half steps/whole steps (4.2); Enharmonic intervals and chords (1.1.5.3) is addressed before chords and intervals (4.5).

I understand with the larger organization of the text why these topics are not put close together, however, I would advise shifting chapters or sections around to avoid constantly flipping ahead in the book. It might be nice to move the chapter on definitions or the chapter on physical science to the beginning. In any case, the sections on tone and rhythm should occur before the sections on notation.

Interface rating: 2

Several of the hyperlinks are ineffective. On the positive side, the images are all free of distortion.

There are a few grammatical errors (see "Accuracy"). They are mostly minor issues that would not greatly distract from the subject at hand.

This is a huge bonus for this text. It makes a point to cover aspects of music involving jazz and popular music topics such as chord symbols, upper extensions, and swing, as well as world music topics such as exotic scales and ragas. Although based in Western theory, the text involves plenty of non-Western musical approaches.

This text would be ideal for a theory fundamentals or remedial theory course - especially if there is minimal teacher interaction available. Although at times the text diverges to topics arguably more advanced than basic (ie altered chords), with guided reading the student could fill gaps in their musical knowledge that would better prepare them for a collegiate music education.

One additional suggestion would be to have even more exercises available at the end of each section.

Reviewed by Keith Bradshaw, Associate Dean, College of Performing and Visual Arts, Southern Utah University on 6/19/18

The text is fairly comprehensive, a bit too comprehensive for a music fundamentals class. Sections of the book go a little too much in depth for a beginning music theory student with no experience. The index is useful and thorough. read more

The text is fairly comprehensive, a bit too comprehensive for a music fundamentals class. Sections of the book go a little too much in depth for a beginning music theory student with no experience. The index is useful and thorough.

The materials presented are accurate and presented well, though the sequence of materials is perhaps different than other similar texts. Explanations are sometimes too in depth and others too shallow.

The text is current and is not likely to lose its relevance. The elements of music are fairly constant, though teaching styles may vary. Updates should be simple to make.

The writing is accessible and reads well. At times, the explanations are too lengthy for a beginning fundamentals text and cover elements that are for more advanced study.

Consistency is appropriate for the subject. Terms and explanations are constant throughout the text.

The text is easily divisible into smaller sections. Instructors should be able to tailor the content to fit their desired teaching style and delivery method.

The flow can be a bit awkward at times, mentioning terms and concepts before an explanation has been provided. The text seems to wander as it covers a bit too much material for a fundamentals course.

I found no interface problems with the text.

The language of the text is appropriate and grammar is correct.

The text discusses western music and is not meant to be all-inclusive culturally. I discern nothing offensive in the text.

Though the text may be a bit too comprehensive, it can be a valuable resource for OER users.

Reviewed by Jason Heald, Associate Professor, Umpqua Community College on 6/19/18

This textbook is very comprehensive in the range of subjects it covers. In an effort to "cover all the bases", some of the most crucial skills necessary for understanding music theory receive relatively superficial treatment, while topics with... read more

This textbook is very comprehensive in the range of subjects it covers. In an effort to "cover all the bases", some of the most crucial skills necessary for understanding music theory receive relatively superficial treatment, while topics with less immediate application are covered in great detail. For example, one might question whether a student with no musical background could successfully learn to read music notation given the brief explanations and limited exercises presented in the opening chapter, and one might also be skeptical of the usefulness of such a detailed explanation of the physics of sound to the beginning musician. That said, the topics covered in the textbook represents a broad base of knowledge.

The book is generally quite accurate with occasional lapses. For example, on page 198, labeling a V7/vi as a III7 and a V7/IV as a I7 is incorrect, and is likely to cause confusion for the student when they study secondary dominants. It would be best if all musical examples could be explained accurately with the information presented in the textbook.

It is not likely that the subject matter will become out-dated, so this textbook should remain relevant for a long period of time. Supplementing the text with new information should be easy to incorporate.

The book is clear and well-written. Again, for the non-musician, the compressed presentation of some topics, e.g., notation, might be difficult to understand and quite daunting.

The book seems consistent in its use of language and accurate in its terminology.

One of the strengths of this book might be its modularity. Chapters are relatively self-contained and could be used to supplement other textbooks or course materials.

The organization of this textbook is somewhat baffling and, perhaps, its weakest attribute. For instance, it is perplexing that the concept of key signatures is introduced in the first 20 pages, yet intervals and the circle of fifths are not discussed until the second half of the book. if the topics were to be taught in the order presented in the book, instructors might find this book very difficult to use.

The textbook has rather primitive-looking graphics and notational examples. But it doesn't detract from the overall effectiveness of the textbook.

The text appears to have no grammatical errors.

The book is grounded in Western European tradition, but makes some effort to be culturally inclusive. Its language is in no way culturally insensitive.

This textbook is very intriguing and well-written. However, I would find it difficult to use as a primary textbook for either music majors or non-majors. It lacks the necessary depth in subjects like figured bass and harmonic analysis for music majors, and it covers too much ground for a music appreciation or music fundamentals classes. However, it might be an excellent supplemental textbook for all three of the prior courses and a host of other music classes.

Reviewed by Scott Ethier, Adjunct Lecturer, LaGuardia Community College, CUNY on 2/1/18

In some ways, this book is very comprehensive – maybe too comprehensive (do we really need 4000 words on tuning systems in an introductory text?). But it does cover all of the topics you could expect to get through in an introductory theory... read more

In some ways, this book is very comprehensive – maybe too comprehensive (do we really need 4000 words on tuning systems in an introductory text?). But it does cover all of the topics you could expect to get through in an introductory theory class.

In other ways, it’s missing some vital components. So much of introductory music theory is about mastering skills like reading music and building scales and chords. There are some exercises in this book, but there is no attempt at bridging the gap between the concepts being discussed and their practical application.

I found to book to be accurate throughout.

The core content of the book (such as notation, scales, and chords) is well-traveled ground. 80% of the material is identical to what a music student would have learned a century ago, and unless the priorities of music theory pedagogy change radically, it will be relevant for the foreseeable future.

What feels out of date to some degree is the nature of the project – a closed-source, PDF/HTML-based textbook. We live in an era where someone in a video will take you by the hand and show you how to voice an C7b9 chord, the best way to finger a Bach cello suite, or how to create the nastiest bass drop in your dubstep remix. There’s no way a single authored textbook could compete with resources that vast and accessible.

Perhaps the answer is a text that is open source, allowing many users to edit and contribute to the text?

This book is clear enough if you’ve already mastered the subject and just need a reference. If you don’t have a background in music theory, this book will be a dry and potentially confusing read.

It’s difficult to write clear and engaging prose about music theory. The best music theory writing emerges organically from a question or observation about a piece of music. Music must be at the center of any effective music theory discussion. This book takes the opposite approach, introducing many topics abstractly without any reference to an actual piece of music.

Take for example its discussion of the triad:

-------------------- 5.1 Triads

Harmony (Section 2.5) in Western music (Section 2.8) is based on triads. Triads are simple three note chords (Chords) built of thirds (pg 137).

[Fig 5.1 is here in the original]

The chords in Figure 5.1 are written in root position, which is the most basic way to write a triad. In root position, the root, which is the note that names the chord, is the lowest note. The third of the chord is written a third (Figure 4.26) higher than the root, and the fifth of the chord is written a fifth (Figure 4.26) higher than the root (which is also a third higher than the third of the chord). So the simplest way to write a triad is as a stack of thirds, in root position.

--------------------

This is all technically correct, but it’s not very helpful to the student who knows nothing about triads. And it’s dull. Learning how to build and play triads should be one of the great “aha” moments for a student in music theory. They’re so simple, yet so powerful and versatile. When you understand the triad, a whole world of harmony opens up to you.

A student may be able to decode (with some difficulty) the book’s instructions for building a triad, but they’ll have no sense of why the triad matters (here’s a place where examples of actual music could be helpful).

We generally don’t expect that an introductory music theory text will be a compelling book. But we really should (and this is a criticism I’d level against many commercially produced textbooks too). Some of our students are artists. Some of our students are civilians who are starting a potentially life- long engagement with the arts. If teaching music theory is important, we must get in the habit of writing our textbooks with clarity and passion.

The ideas and terminology seemed consistent from section to section.

It is as modular as an Intro to Theory text could be (although it’s not clear to me why modularity would be desirable in this case). When the book references material from other sections, it clearly points students in the direction of that material.

The organization of the topics made sense. The chapter on acoustics, while informative, seemed to disrupt the flow of the rest of the book a bit (although one could skip that chapter without any problem).

Interface rating: 1

The book’s interface is a real problem on several levels.

The book’s layout (at least the PDF version) is reminiscent of a journal article. The text is formatted in a clear but small font and densely packed with very little whitespace (we’re working in a virtual medium – please use all the whitespace you need!). Diagrams and musical examples are referenced (such as “Fig. 4.2.1”) rather that incorporated directly in the layout of the text. There are copious footnotes and headings are numbered four levels deep (“6.2.2.1 Pythagorean Intonation”).

All of this works to make entry-level music theory look as inviting as the instructions on your tax return. There are plenty of references to supplementary material, but those references are buried in footnotes that contain inactive web links (meaning you can’t just click on them, you need to copy the link and paste it in your web browser). And many of the links are broken.

The diagrams are unappealing and poorly laid out, making it difficult to understand the concepts they are trying to communicate (for example, the circle of fifths chart in Fig. 4.44). The book is set mostly in black and white, but every once in a while parts of the text in figures will be arbitrarily printed in red or blue (see Figure 1.74).

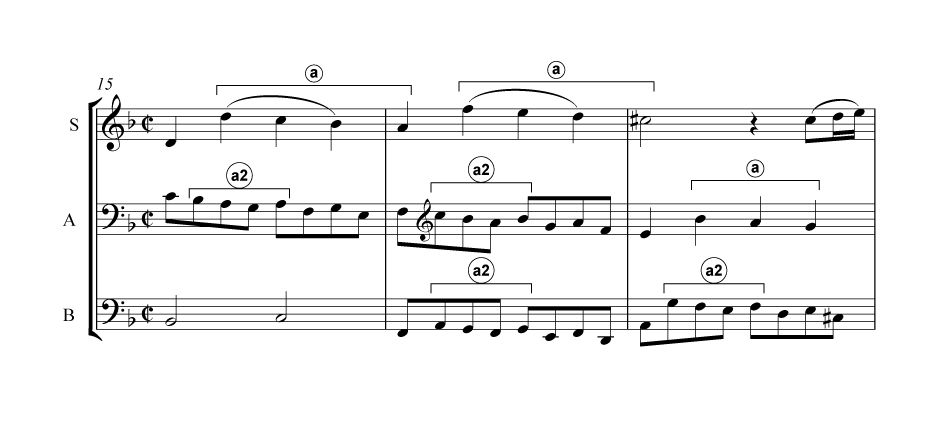

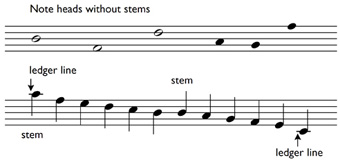

The most troubling element is that the musical examples themselves look amateurish. Music notation software capable of creating professional-looking music layouts has been widely accessible for decades. Some of the problems I have are quibbles (like the out-of –proportion bass clef in Fig. 1.1), but some are inexcusable (like the incorrect stemming of the bass clef line in Fig. 1.10), and some are just bizarre (like Fig. 4.9 where an un-metered musical example is given the time signature 8/4). But in an introductory theory class where learning to clearly and correctly notate music is a priority, sloppy musical examples are inexcusable.

Design may seem like a trivial thing to criticize in a textbook, poor layout and design can be a major impediment to effectively communicating a book’s ideas.

I didn’t find any problems with the grammar of this book.

There is very little actual music in this text, and as a result the book has almost entirely removed music theory from its cultural context. It equally ignores the actual music of most eras and cultures. There’s no Mozart, no Bach, no Gershwin, and no Stevie Wonder. It does deal with some theory topics outside of the realm of classical music, such as the blues scale. But there isn’t a single lick by Robert Johnson or Thelonious Monk to be found. In the places the book does use actual music, the choices lean in the public-domain folk direction (for instance, transposition is introduced via the sea-shanty “The Saucy Sailor”). I realize the nature of this project might limit it to public domain music, but that still includes a vast amount of repertoire. Also, there is some room under fair use for some use of copyrighted material (and maybe the Open Library Textbook project could guide authors on how to use that right to its fullest extent).

I’ve been critical of this text, but I’d like to acknowledge the enormous amount of work that Catherine Schmidt-Jones has put in to creating this book. Her task was not only to write a theory text from scratch, but also to make the case that an open textbook could be a viable alternative to commercially produced textbooks. This is a necessary and important first step. I’m grateful that she took it and I’m rooting for its ultimate success.

Reviewed by Sean Doyle, Professorial Lecturer, American University on 2/1/18

Overall, the text is a comprehensive approach to the fundamentals of music theory, with particular focus on the standards and conventions of music notation. There is a detailed index but no glossary. The addition of a glossary could be helpful,... read more

Overall, the text is a comprehensive approach to the fundamentals of music theory, with particular focus on the standards and conventions of music notation. There is a detailed index but no glossary. The addition of a glossary could be helpful, especially with regard to terminology that is often mixed-up or easily confused by students beginning to read music - "meter" vs. "time signature", for example. This is described in a note in the body of the text, but appearing in a glossary would make for a quicker, more straightforward delineation between the two concepts.

The content, in general, is accurate and unbiased. Some of the notational symbols are a bit of out the ordinary - the double-flat, for instance - is graphically not quite what one would see in printed music (the flat signs "smushed" together or overlapping). This may be a result of the unique notation program being used to render the musical examples. The inclusion of a more systematized approach to counting rhythms (rather than 1-&, 2&) would not only be more helpful but certainly appropriate to the learning abilities of the student for whom this text is intended.

Content is relevant and will not be obsolete, other than perhaps occasional references to specific technologies.

The tone of the text is straightforward and accessible. Concepts are expressed simply and directly. Longer sections/bodies of text (especially in later chapters pertaining to form) could be clarified by including more musical examples.

The text maintains a conscious, consistent use of terminology.

This is perhaps this text's greatest strength - the sectionalization and numbering of each concept. There is occasional self-reference, but entirely to the benefit of the reader in developing upon concepts and ideas. The text is very easily navigable and assigning discrete units to correspond with distinct sections of an assignment or course outline would be very easy for any instructor to manage.

Overall, the organization of the topics in this text is good. Perhaps the early, detailed introduction to acoustics (Ch. 3) would be better suited with the later discussion of those concepts within the context of hearing (ear-training), would form a more cohesive organization of that concept.

The interface of the text seems clear and easy to navigate. It took me a while to realized the linked content in footnotes was occasionally supplemental material and not just online access to the print material of the text - this could be made more explicit in the front matter of the book.

The grammar is accurate. Occasionally the tone of the text suggests a certain uncertainty (using colloquial terms like "pretty much", "tends to", etc.)

Although there are not many examples of notated musical works cited in the text (for reasons of copyright, presumably), there are mentions of musical examples from a diverse variety of cultural backgrounds.

Reviewed by Joshua Harris, Assistant Professor of Music, Sweet Briar College on 8/15/17

The title and introduction's stated objective ("to explore basic music theory so thoroughly that the interested student will then be able to easily pick up whatever further theory is wanted") are vague enough that the question of comprehensiveness... read more

The title and introduction's stated objective ("to explore basic music theory so thoroughly that the interested student will then be able to easily pick up whatever further theory is wanted") are vague enough that the question of comprehensiveness becomes difficult. There is in the book a comprehensive discussion of musical mechanics and notation, in some cases more than a "basic" course would require (specifically discussions of orchestration, acoustics, and temperament). However, these tangential topics are far from comprehensive themselves. Also, it is difficult to place this in a college music theory curriculum; it's too advanced at times to fit the rudiments or fundamental (i.e., preparatory) course, but it lacks any substantial discussion of counterpoint, voice-leading, modulation, or chromatic harmony, which are common to the typical four- or five-semester theory course, usually covered by a single text. As an introductory survey of music-theoretical concepts, however, I would call this very comprehensive.

The book is accurate for the most part, if imprecise at times. The discussion of time signatures, for example, is misleading but ultimately harmless (the old top number/bottom number rule about what note gets the beat, etc., doesn't apply to compound meters). Da capo and Dal segno are also translated incorrectly as "to" the head and sign, although the gist remains correct (i.e., one does, in fact, go back "to the head," etc.).

The basic mechanics of music and music notation are unlikely to change soon, but some broken links here--apparently intended to take the reader to online discussions about certain ideas--suggest that it might already be out of date. There is some indication on another website that updates are being made, or were intended to be made, by the author, but it isn't clear what the timeline for these updates is. The only date seems to be the original publication date of 2013.

The conversational style of the prose undermines the book's clarity. The technical terminology is adequately explained, although sometimes it is not well-defined at the time it is introduced. However, a hyperlink is always provided to a more complete definition.

The book is internally consistent. This is reinforced by hyperlinks throughout the epub version.

Generally, the book is modular enough to be useful. I can envision a teacher being able to easily realign the subunits without presenting disruption to the reader. However, the layout (of the epub version, especially) often detaches subheadings from text, causing some mild confusion.

It seems like modularity has won out over logical flow of ideas. Enharmonic intervals and chords are included in the discussion of enharmonic pitches, for example, well before the concept of chords is introduced. I like the idea of links, but they might be overdone. The structure of the text relies on students' ability to make good use of the links to follow threads of complementary and reinforcing ideas, but beginning students won't know what fits together, and they could get lost. Also, there are intrusive notes from the author regarding an online survey, which is now closed, throughout the text.

The layout (epub version) feels cluttered. I would appreciate more space between headings and text, as well as above and below musical examples. Musical examples were very amateurish, using an unusual music font that was difficult to read. There were also frequent collisions of musical symbols (especially double flats) and some superfluous symbols (for example, it's distracting and irrelevant to use an 8/4 time signature when discussing intervals).

The text contains no grammatical errors, though inconsistencies in style and fonts are distracting and imprecise.

The text does a good job including discussion of (or at least mentioning) music from a variety of cultures.

At the risk of criticizing the book for what it isn't instead of what it is, I would just say that for this reviewer, an introductory text that had less prose and more focused text, such as lists with key terms, definitions, etc., to accompany the already useful examples, would be more helpful.

Reviewed by Claire Boge, Associate Professor and Coordinator of Undergraduate Music Theory, MIami University (Oxford Ohio) on 6/20/17

The book covers material corresponding to what most call Basic Musicianship and Fundamentals of Music and Music Notation, as well as more general terminology that would apply to Music Appreciation. It also adds material introducing the basic... read more

The book covers material corresponding to what most call Basic Musicianship and Fundamentals of Music and Music Notation, as well as more general terminology that would apply to Music Appreciation. It also adds material introducing the basic concepts of the Physics of Music and how it works in various instruments. Despite showing modules on Form, Cadence, and Beginning Harmonic Analysis, the author makes it clear that many of these concepts are more advanced and recommends additional sources be used. The book could use a module covering figured bass -- and although there is a cross reference to other published software on this topic (ArsNova), that software requires purchase or a site license and is not accessible through the open source text.

The content is accurate but some of it needs to be updated. See below.

The text is written in a way that updates should be easy to implement, and the author is very conscientious to tell students in the preface that whenever multiple terms exist, they will be given. The current content is accurate but some of it needs new supplementary data: 1) Octave designations should also refer to include Acoustical Society names as well as Traditional names, and given the book's implied target audience, MIDI-standard might also be a good idea; and 2) Outside references should be maintained to make sure that the most recent editions are cited (such as Grout [Palisca/Burkholder] History of Western Music).

The text is clearly written. I particularly like that the author sometimes interrupts the "facts" by asking questions which take the reader to the next explanation. This begins to subconsciously set a theoretical mindset of looking for deeper explanations. I especially recommend that everyone read the Introduction before going into any of the modules! It is one of the best parts of the book, and not only sets the stage for what the book does, but also how it fits within the larger context of explanations.

The book is clear, with terminology consistent throughout. But, different modules seem to be written for different levels of students. The early chapters are presented very basically and are extremely thorough -- some even contain external lesson plans clearly written for beginning classroom teachers following national standards. Later chapters, such as those on acoustics and terminology, seem to be addressed to a college audience. This extends to methodology as well. Earlier content is more algorithmic in nature (teaching treble clef as EveryGoodBoyDoesFine instead of G-clef with the alphabet surrounding the G-line); later material is more linguistic (definitions of different textures and presentation of interval inversion, for example). It is not offensive, but it does make for some awkwardness if one jumps around in the modular sequence.

Modularity is one of the best aspects of this publication. Sections are clear; subheadings are frequent, examples are peppered throughout, and everything is graphically pleasing. It would be easy to use some modules and not others and maintain consistency.

The book generally follows an established pedagogical flow frequent in many similar presentations. The only interruption is with the Physics materials. It does make sense to introduce the scientific explanations when they are pertinent, but it would also be helpful to collect them all in one place. For thorough review readers, compile Module 3 with 4.6 for a complete unit.