- Library Catalogue

Templates for structuring argumentative essays with practice exercises and solutions

On this page, thesis statement, referring to others’ work.

- Using impersonal language

Agreeing with what you’ve reviewed in the “They say” section

Disagreeing with what you’ve reviewed in the “they say” section.

- Agreeing and disagreeing simultaneously

My critics say

This page introduces a framework for writing argumentative/analytical essays, following a structure dubbed “They Say, I Say, My Critics Say, I Respond.” [1]

This page also includes a number of templates [2] or examples that you may find helpful for writing argumentative/analytical essays. Keep in mind that it is possible to change the sequence of the framework sections. Also, the templates can be used interchangeably.

A principal element of an argumentative/analytical essay is the thesis statement.

A thesis statement is one or two sentences (maybe more in longer essays) typically occurring near the end of an essay introduction; it shows your position regarding the topic you are investigating or your answer(s) to the question(s) that you are responding to.

Here are some templates that may help you write an effective thesis statement:

- In this paper, I argue that .......... because ..........

- In the pages that follow, I will argue that .......... because ..........

- Although/Even though .......... this essay argues that/I will argue that .......... because ..........

- This paper attempts to show that ..........

- This paper contests the claim that ..........

- This paper argues that ..........

- The central thesis of this paper is ..........

- In this essay, I attempt to defend the view that ..........

Thesis statement exercise and solutions

Imagine that you have been asked to write an argumentative essay about physical education in the Canadian high school system. Use one of the templates suggested to write a thesis statement about this topic.

- In the pages that follow, I will argue that physical education in the Canadian high school system has been largely ineffective because it has remained limited in its range of exercises and has failed to connect with students’ actual interests, such a dance and martial arts.

- This paper attempts to show that physical education is a crucial aspect of the Canadian high school system because many teenagers do not experience encouragement to do physical activity outside of school and contemporary life is increasingly sedentary for people of all ages.

The body of an essay usually begins by providing a background of the topic or a summary of the resources that you have reviewed (this is sometimes called a literature review). Here, you bring other people’s views into the paper. You want to show your readers what other scholars say (“they say”) about the topic, using techniques like paraphrasing, summarizing, and direct quotation.

You can start this section using one the following templates or examples to delve into the topic.

They say exercise and solutions

Imagine that you are now trying to incorporate some sources into your academic paper about physical education in the Canadian high school system. Try using a couple of templates from the “They Say” section of the handout.

Bonus exercise: See if you can identify the “template” structure that each of the sentences below is using (hint, they are different from the templates provided above).

- Brown (2018) rejects the idea that the levels of climate change we are currently seeing can be considered “natural” or “cyclical” (p. 108).

- According to Marshall (2017), we can see evidence of both code-switching and code-meshing in students’ reflective essay writing (p. 88).

- Previous studies of physical education have revealed that teenagers experience a significant degree of dissatisfaction with their gym classes (Wilson, 2010; Vowel et al, 1999; Mossman, 1986).

- A number of studies conducted prior to the 1990s have demonstrated that teenagers used to experience more encouragement to engage in physical activities outside of school hours (Sohal, 1954; Silverman, 1965; Lu, 1970; Mossman, 1986).

- Jones’ (2017) investigations of sedentariness among young people have shown significant increases in illness among teenagers who do not engage in regular physical activity.

After the background section (e.g., summary or literature review), you need to include your own position on the topic (“I say”). Tell your reader if, for instance, you agree, disagree, or even both agree and disagree with the work you have reviewed.

You can use one of the following templates or samples to bring your voice in:

- It could be argued that ..........

- It is evident/clear/obvious that the role of modern arts is ..........

- Clearly/Evidently, the role of education is ..........

- There is no little doubt that ..........

- I agree (that) ..........

- I support the view that ...........

- I concur with the view that ..........

- I disagree (that) ..........

- I disagree with the view that ..........

- I challenge/contest the view that ..........

- I oppose/am opposed to ..........

- I disagree with X’s view that .......... because, as recent research has shown, ..........

- X contradicts herself/can’t have it both ways. On the one hand, she argues ........... On the other hand, she also says ..........

- By focusing on .........., X overlooks the deeper problem of ..........

- Although I agree with X up to a point, I cannot accept his overriding assumption that ..........

- Although I disagree with much that X says, I fully endorse his final conclusion that ..........

- Though I concede that .........., I still insist that ..........

- X is right that .........., but she seems on more dubious ground that when she claims that ..........

- While X is probably wrong when she claims tha ..........., she is right that ..........

- Whereas X provides ample evidence that .........., Y and Z’s research on .......... and .......... convinces me that .......... instead.

- I’m of two minds about X’s claim that ........... On the one hand, I agree that .......... On the other hand, I’m not sure if ..........

- My feelings on the issue are mixed. I do support X’s position that .........., but I find Y’s argument about .......... and Z’s research on .......... to be equally persuasive.

I say exercises and solutions

Try using a template from each of the sections below to bring your own position into your writing:

- Agreeing with what you’ve reviewed

- Disagreeing with that you’ve reviewed

Using impersonal language There is little doubt that the teenage years are important for establishing life-long habits.

Agreeing with what you’ve reviewed in the “They say” section I support the view, presented by Vowel et al (1999) that effective physical education needs to consider the heightened self-consciousness that many teenagers experience and, in particular, needs to be sensitive to the body image issues that can be pervasive among young people.

Disagreeing with what you’ve reviewed in the “They say” section By focusing on school physical education programs and their shortcomings, Wilson (2010) overlooks the deeper problem that young people are experiencing a lack of motivation to incorporate healthy exercise into their daily lives.

Agreeing and Disagreeing simultaneously Though I concede that school physical education programs are valuable, I still insist that they cannot be the sole or even the primary way that we promote an active lifestyle among young people.

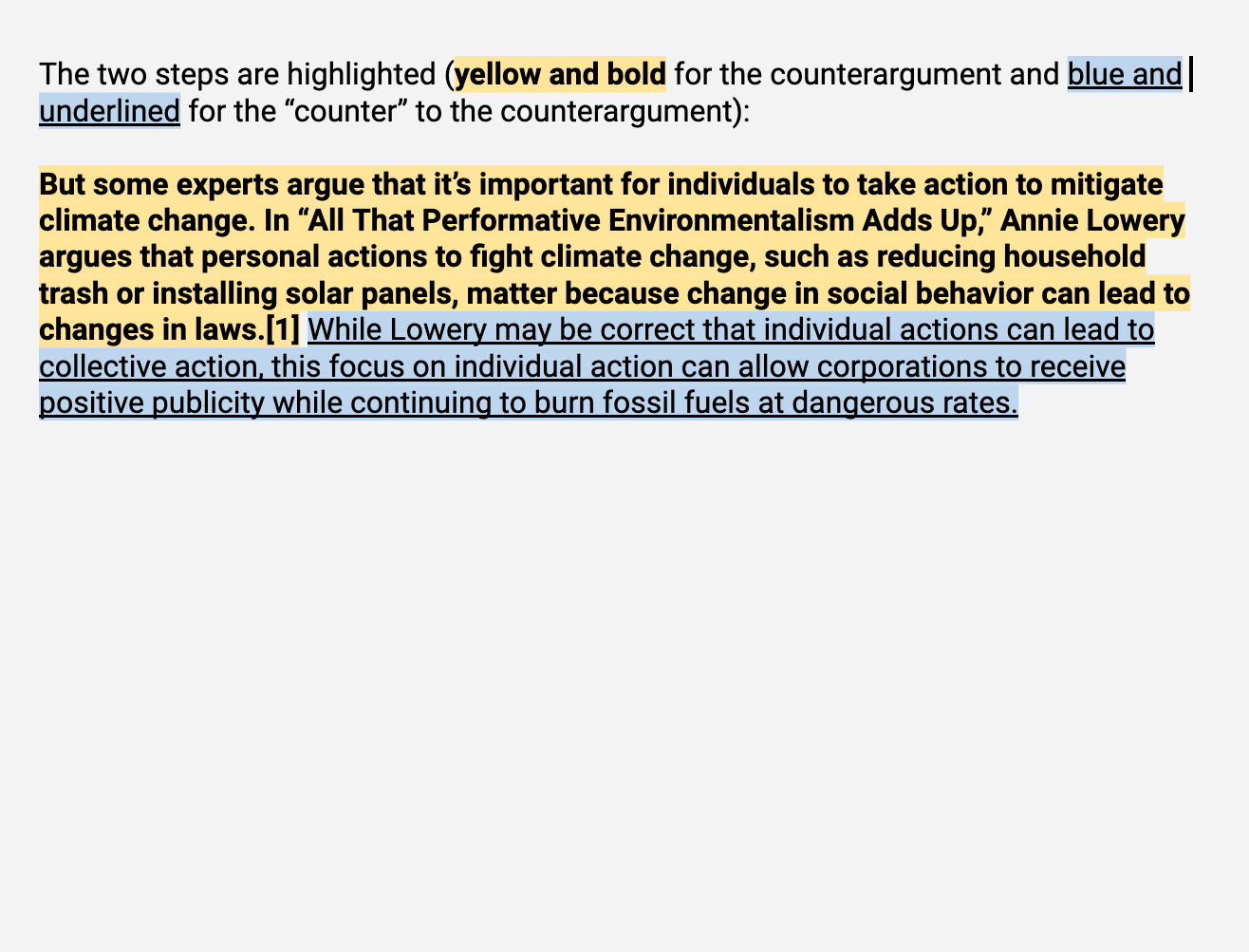

In a good argumentative essay, in addition to expressing your position and argument, you should consider possible opposing views to your argument: refer to what your opponents say (“my critics say”) and why they may disagree with your argument.

Including the ideas of those who may disagree with you makes up the counterargument section of your paper. You can refer to actual people, including other research scholars who may disagree with you, or try and imagine what those who disagree with you might say.

Remember, a thesis should be debatable, so you should be able to imagine someone disagreeing you’re your position. Here are some templates that may help you in writing counterargument:

My critics say exercise and solutions

Using one of the templates, try imagining a counterargument for the thesis you drafted earlier.

Sociocultural theorists used to believe that adolescence was a time of “natural defiance” (Fung, 1995) and therefore discounted the role of educational programs aimed at supporting teenagers to form healthy habits. Much of the focus of schooling therefore became about teaching specific content and skills.

Critics may call into question my assumption that effective physical education can help establish life-long healthy living habits.

After explaining what your opponents say, you have to refute them. This is sometimes called the rebuttal. Here, you can show your readers that your opponents either fail to provide enough evidence to support their argument or their evidence lacks credibility and/or is flawed.

Alternatively, you may argue that your opponents’ argument is valid, but not persuasive enough to be used in your study, or that their argument could be valid in a different context.

Don’t forget that for each part of your argument, you must provide enough evidence for the claims that you make. This means that if you include one of these templates in your essays, you have to explain the evidence it presents in a way that is clear and convincing for your reader.

I respond exercise and solutions

Using one of the templates, craft a rebuttal to the counterargument you just created.

Sociocultural theorists used to believe that adolescence was a time of “natural defiance” (Fung, 1995) and therefore discounted the role of educational programs aimed at supporting teenagers to form healthy habits. Much of the focus of schooling therefore became about teaching specific content and skills. However, this argument fails to demonstrate that the defiance observed during adolescence was “natural” or inherent and not a product of a specific cultural environment. It therefore does not convince me that education during the adolescent years needs to remain rigidly focused on content and skills.

Critics may call into question my assumption that effective physical education can help establish life-long healthy living habits. While it is true that we cannot assume that physical education will automatically lead to the establishment of healthy habits, I maintain that the creation of such habits, rather than simply teaching specific physical education content or skills, should be the central goal of an effective physical education program.

Graff, G., & Birkenstein, C. (2017). They say / I say: The moves that matter in academic writing, with readings (3rd ed.). New York: Norton W. W. Company.

Marshall, S. (2017). Advance in academic writing: Integrating research, critical thinking, academic reading and writing. Toronto, Canada: Pearson Education ESL.

Morley, J. (2014). Academic phrasebank. Retrieved from http://www.phrasebank.manchester.ac.uk/

[1] Adapted from Graff and Birkenstein (2016).

[2] The templates used in this handout are adapted from Morley (2014), Marshall (2017), and Graff and Birkenstein (2016).

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Praxis Core Writing

Course: praxis core writing > unit 1, argumentative essay | quick guide.

- Source-based essay | Quick guide

- Revision in context | Quick guide

- Within-sentence punctuation | Quick guide

- Subordination and coordination | Quick guide

- Independent and dependent Clauses | Video lesson

- Parallel structure | Quick guide

- Modifier placement | Quick guide

- Shifts in verb tense | Quick guide

- Pronoun clarity | Quick guide

- Pronoun agreement | Quick guide

- Subject-verb agreement | Quick guide

- Noun agreement | Quick guide

- Frequently confused words | Quick guide

- Conventional expressions | Quick guide

- Logical comparison | Quick guide

- Concision | Quick guide

- Adjective/adverb confusion | Quick guide

- Negation | Quick guide

- Capitalization | Quick guide

- Apostrophe use | Quick guide

- Research skills | Quick guide

Argumentative essay (30 minutes)

- states or clearly implies the writer’s position or thesis

- organizes and develops ideas logically, making insightful connections between them

- clearly explains key ideas, supporting them with well-chosen reasons, examples, or details

- displays effective sentence variety

- clearly displays facility in the use of language

- is generally free from errors in grammar, usage, and mechanics

- organizes and develops ideas clearly, making connections between them

- explains key ideas, supporting them with relevant reasons, examples, or details

- displays some sentence variety

- displays facility in the use of language

- states or implies the writer’s position or thesis

- shows control in the organization and development of ideas

- explains some key ideas, supporting them with adequate reasons, examples, or details

- displays adequate use of language

- shows control of grammar, usage, and mechanics, but may display errors

- limited in stating or implying a position or thesis

- limited control in the organization and development of ideas

- inadequate reasons, examples, or details to explain key ideas

- an accumulation of errors in the use of language

- an accumulation of errors in grammar, usage, and mechanics

- no clear position or thesis

- weak organization or very little development

- few or no relevant reasons, examples, or details

- frequent serious errors in the use of language

- frequent serious errors in grammar, usage, and mechanics

- contains serious and persistent writing errors or

- is incoherent or

- is undeveloped or

- is off-topic

How should I build a thesis?

- (Choice A) Kids should find role models that are worthier than celebrities because celebrities may be famous for reasons that aren't admirable. A Kids should find role models that are worthier than celebrities because celebrities may be famous for reasons that aren't admirable.

- (Choice B) Because they profit from the admiration of youths, celebrities have a moral responsibility for the reactions their behaviors provoke in fans. B Because they profit from the admiration of youths, celebrities have a moral responsibility for the reactions their behaviors provoke in fans.

- (Choice C) Celebrities may have more imitators than most people, but they hold no more responsibility over the example they set than the average person. C Celebrities may have more imitators than most people, but they hold no more responsibility over the example they set than the average person.

- (Choice D) Notoriety is not always a choice, and some celebrities may not want to be role models. D Notoriety is not always a choice, and some celebrities may not want to be role models.

- (Choice E) Parents have a moral responsibility to serve as immediate role models for their children. E Parents have a moral responsibility to serve as immediate role models for their children.

How should I support my thesis?

- (Choice A) As basketball star Charles Barkley stated in a famous advertising campaign for Nike, he was paid to dominate on the basketball court, not to raise your kids. A As basketball star Charles Barkley stated in a famous advertising campaign for Nike, he was paid to dominate on the basketball court, not to raise your kids.

- (Choice B) Many celebrities do consider themselves responsible for setting a good example and create non-profit organizations through which they can benefit youths. B Many celebrities do consider themselves responsible for setting a good example and create non-profit organizations through which they can benefit youths.

- (Choice C) Many celebrities, like Kylie Jenner with her billion-dollar cosmetics company, profit directly from being imitated by fans who purchase sponsored products. C Many celebrities, like Kylie Jenner with her billion-dollar cosmetics company, profit directly from being imitated by fans who purchase sponsored products.

- (Choice D) My ten-year-old nephew may love Drake's music, but his behaviors are more similar to those of the adults he interacts with on a daily basis, like his parents and teachers. D My ten-year-old nephew may love Drake's music, but his behaviors are more similar to those of the adults he interacts with on a daily basis, like his parents and teachers.

- (Choice E) It's very common for young people to wear fashions similar to those of their favorite celebrities. E It's very common for young people to wear fashions similar to those of their favorite celebrities.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, how to write an a+ argumentative essay.

Miscellaneous

You'll no doubt have to write a number of argumentative essays in both high school and college, but what, exactly, is an argumentative essay and how do you write the best one possible? Let's take a look.

A great argumentative essay always combines the same basic elements: approaching an argument from a rational perspective, researching sources, supporting your claims using facts rather than opinion, and articulating your reasoning into the most cogent and reasoned points. Argumentative essays are great building blocks for all sorts of research and rhetoric, so your teachers will expect you to master the technique before long.

But if this sounds daunting, never fear! We'll show how an argumentative essay differs from other kinds of papers, how to research and write them, how to pick an argumentative essay topic, and where to find example essays. So let's get started.

What Is an Argumentative Essay? How Is it Different from Other Kinds of Essays?

There are two basic requirements for any and all essays: to state a claim (a thesis statement) and to support that claim with evidence.

Though every essay is founded on these two ideas, there are several different types of essays, differentiated by the style of the writing, how the writer presents the thesis, and the types of evidence used to support the thesis statement.

Essays can be roughly divided into four different types:

#1: Argumentative #2: Persuasive #3: Expository #4: Analytical

So let's look at each type and what the differences are between them before we focus the rest of our time to argumentative essays.

Argumentative Essay

Argumentative essays are what this article is all about, so let's talk about them first.

An argumentative essay attempts to convince a reader to agree with a particular argument (the writer's thesis statement). The writer takes a firm stand one way or another on a topic and then uses hard evidence to support that stance.

An argumentative essay seeks to prove to the reader that one argument —the writer's argument— is the factually and logically correct one. This means that an argumentative essay must use only evidence-based support to back up a claim , rather than emotional or philosophical reasoning (which is often allowed in other types of essays). Thus, an argumentative essay has a burden of substantiated proof and sources , whereas some other types of essays (namely persuasive essays) do not.

You can write an argumentative essay on any topic, so long as there's room for argument. Generally, you can use the same topics for both a persuasive essay or an argumentative one, so long as you support the argumentative essay with hard evidence.

Example topics of an argumentative essay:

- "Should farmers be allowed to shoot wolves if those wolves injure or kill farm animals?"

- "Should the drinking age be lowered in the United States?"

- "Are alternatives to democracy effective and/or feasible to implement?"

The next three types of essays are not argumentative essays, but you may have written them in school. We're going to cover them so you know what not to do for your argumentative essay.

Persuasive Essay

Persuasive essays are similar to argumentative essays, so it can be easy to get them confused. But knowing what makes an argumentative essay different than a persuasive essay can often mean the difference between an excellent grade and an average one.

Persuasive essays seek to persuade a reader to agree with the point of view of the writer, whether that point of view is based on factual evidence or not. The writer has much more flexibility in the evidence they can use, with the ability to use moral, cultural, or opinion-based reasoning as well as factual reasoning to persuade the reader to agree the writer's side of a given issue.

Instead of being forced to use "pure" reason as one would in an argumentative essay, the writer of a persuasive essay can manipulate or appeal to the reader's emotions. So long as the writer attempts to steer the readers into agreeing with the thesis statement, the writer doesn't necessarily need hard evidence in favor of the argument.

Often, you can use the same topics for both a persuasive essay or an argumentative one—the difference is all in the approach and the evidence you present.

Example topics of a persuasive essay:

- "Should children be responsible for their parents' debts?"

- "Should cheating on a test be automatic grounds for expulsion?"

- "How much should sports leagues be held accountable for player injuries and the long-term consequences of those injuries?"

Expository Essay

An expository essay is typically a short essay in which the writer explains an idea, issue, or theme , or discusses the history of a person, place, or idea.

This is typically a fact-forward essay with little argument or opinion one way or the other.

Example topics of an expository essay:

- "The History of the Philadelphia Liberty Bell"

- "The Reasons I Always Wanted to be a Doctor"

- "The Meaning Behind the Colloquialism ‘People in Glass Houses Shouldn't Throw Stones'"

Analytical Essay

An analytical essay seeks to delve into the deeper meaning of a text or work of art, or unpack a complicated idea . These kinds of essays closely interpret a source and look into its meaning by analyzing it at both a macro and micro level.

This type of analysis can be augmented by historical context or other expert or widely-regarded opinions on the subject, but is mainly supported directly through the original source (the piece or art or text being analyzed) .

Example topics of an analytical essay:

- "Victory Gin in Place of Water: The Symbolism Behind Gin as the Only Potable Substance in George Orwell's 1984"

- "Amarna Period Art: The Meaning Behind the Shift from Rigid to Fluid Poses"

- "Adultery During WWII, as Told Through a Series of Letters to and from Soldiers"

There are many different types of essay and, over time, you'll be able to master them all.

A Typical Argumentative Essay Assignment

The average argumentative essay is between three to five pages, and will require at least three or four separate sources with which to back your claims . As for the essay topic , you'll most often be asked to write an argumentative essay in an English class on a "general" topic of your choice, ranging the gamut from science, to history, to literature.

But while the topics of an argumentative essay can span several different fields, the structure of an argumentative essay is always the same: you must support a claim—a claim that can reasonably have multiple sides—using multiple sources and using a standard essay format (which we'll talk about later on).

This is why many argumentative essay topics begin with the word "should," as in:

- "Should all students be required to learn chemistry in high school?"

- "Should children be required to learn a second language?"

- "Should schools or governments be allowed to ban books?"

These topics all have at least two sides of the argument: Yes or no. And you must support the side you choose with evidence as to why your side is the correct one.

But there are also plenty of other ways to frame an argumentative essay as well:

- "Does using social media do more to benefit or harm people?"

- "Does the legal status of artwork or its creators—graffiti and vandalism, pirated media, a creator who's in jail—have an impact on the art itself?"

- "Is or should anyone ever be ‘above the law?'"

Though these are worded differently than the first three, you're still essentially forced to pick between two sides of an issue: yes or no, for or against, benefit or detriment. Though your argument might not fall entirely into one side of the divide or another—for instance, you could claim that social media has positively impacted some aspects of modern life while being a detriment to others—your essay should still support one side of the argument above all. Your final stance would be that overall , social media is beneficial or overall , social media is harmful.

If your argument is one that is mostly text-based or backed by a single source (e.g., "How does Salinger show that Holden Caulfield is an unreliable narrator?" or "Does Gatsby personify the American Dream?"), then it's an analytical essay, rather than an argumentative essay. An argumentative essay will always be focused on more general topics so that you can use multiple sources to back up your claims.

Good Argumentative Essay Topics

So you know the basic idea behind an argumentative essay, but what topic should you write about?

Again, almost always, you'll be asked to write an argumentative essay on a free topic of your choice, or you'll be asked to select between a few given topics . If you're given complete free reign of topics, then it'll be up to you to find an essay topic that no only appeals to you, but that you can turn into an A+ argumentative essay.

What makes a "good" argumentative essay topic depends on both the subject matter and your personal interest —it can be hard to give your best effort on something that bores you to tears! But it can also be near impossible to write an argumentative essay on a topic that has no room for debate.

As we said earlier, a good argumentative essay topic will be one that has the potential to reasonably go in at least two directions—for or against, yes or no, and why . For example, it's pretty hard to write an argumentative essay on whether or not people should be allowed to murder one another—not a whole lot of debate there for most people!—but writing an essay for or against the death penalty has a lot more wiggle room for evidence and argument.

A good topic is also one that can be substantiated through hard evidence and relevant sources . So be sure to pick a topic that other people have studied (or at least studied elements of) so that you can use their data in your argument. For example, if you're arguing that it should be mandatory for all middle school children to play a sport, you might have to apply smaller scientific data points to the larger picture you're trying to justify. There are probably several studies you could cite on the benefits of physical activity and the positive effect structure and teamwork has on young minds, but there's probably no study you could use where a group of scientists put all middle-schoolers in one jurisdiction into a mandatory sports program (since that's probably never happened). So long as your evidence is relevant to your point and you can extrapolate from it to form a larger whole, you can use it as a part of your resource material.

And if you need ideas on where to get started, or just want to see sample argumentative essay topics, then check out these links for hundreds of potential argumentative essay topics.

101 Persuasive (or Argumentative) Essay and Speech Topics

301 Prompts for Argumentative Writing

Top 50 Ideas for Argumentative/Persuasive Essay Writing

[Note: some of these say "persuasive essay topics," but just remember that the same topic can often be used for both a persuasive essay and an argumentative essay; the difference is in your writing style and the evidence you use to support your claims.]

KO! Find that one argumentative essay topic you can absolutely conquer.

Argumentative Essay Format

Argumentative Essays are composed of four main elements:

- A position (your argument)

- Your reasons

- Supporting evidence for those reasons (from reliable sources)

- Counterargument(s) (possible opposing arguments and reasons why those arguments are incorrect)

If you're familiar with essay writing in general, then you're also probably familiar with the five paragraph essay structure . This structure is a simple tool to show how one outlines an essay and breaks it down into its component parts, although it can be expanded into as many paragraphs as you want beyond the core five.

The standard argumentative essay is often 3-5 pages, which will usually mean a lot more than five paragraphs, but your overall structure will look the same as a much shorter essay.

An argumentative essay at its simplest structure will look like:

Paragraph 1: Intro

- Set up the story/problem/issue

- Thesis/claim

Paragraph 2: Support

- Reason #1 claim is correct

- Supporting evidence with sources

Paragraph 3: Support

- Reason #2 claim is correct

Paragraph 4: Counterargument

- Explanation of argument for the other side

- Refutation of opposing argument with supporting evidence

Paragraph 5: Conclusion

- Re-state claim

- Sum up reasons and support of claim from the essay to prove claim is correct

Now let's unpack each of these paragraph types to see how they work (with examples!), what goes into them, and why.

Paragraph 1—Set Up and Claim

Your first task is to introduce the reader to the topic at hand so they'll be prepared for your claim. Give a little background information, set the scene, and give the reader some stakes so that they care about the issue you're going to discuss.

Next, you absolutely must have a position on an argument and make that position clear to the readers. It's not an argumentative essay unless you're arguing for a specific claim, and this claim will be your thesis statement.

Your thesis CANNOT be a mere statement of fact (e.g., "Washington DC is the capital of the United States"). Your thesis must instead be an opinion which can be backed up with evidence and has the potential to be argued against (e.g., "New York should be the capital of the United States").

Paragraphs 2 and 3—Your Evidence

These are your body paragraphs in which you give the reasons why your argument is the best one and back up this reasoning with concrete evidence .

The argument supporting the thesis of an argumentative essay should be one that can be supported by facts and evidence, rather than personal opinion or cultural or religious mores.

For example, if you're arguing that New York should be the new capital of the US, you would have to back up that fact by discussing the factual contrasts between New York and DC in terms of location, population, revenue, and laws. You would then have to talk about the precedents for what makes for a good capital city and why New York fits the bill more than DC does.

Your argument can't simply be that a lot of people think New York is the best city ever and that you agree.

In addition to using concrete evidence, you always want to keep the tone of your essay passionate, but impersonal . Even though you're writing your argument from a single opinion, don't use first person language—"I think," "I feel," "I believe,"—to present your claims. Doing so is repetitive, since by writing the essay you're already telling the audience what you feel, and using first person language weakens your writing voice.

For example,

"I think that Washington DC is no longer suited to be the capital city of the United States."

"Washington DC is no longer suited to be the capital city of the United States."

The second statement sounds far stronger and more analytical.

Paragraph 4—Argument for the Other Side and Refutation

Even without a counter argument, you can make a pretty persuasive claim, but a counterargument will round out your essay into one that is much more persuasive and substantial.

By anticipating an argument against your claim and taking the initiative to counter it, you're allowing yourself to get ahead of the game. This way, you show that you've given great thought to all sides of the issue before choosing your position, and you demonstrate in multiple ways how yours is the more reasoned and supported side.

Paragraph 5—Conclusion

This paragraph is where you re-state your argument and summarize why it's the best claim.

Briefly touch on your supporting evidence and voila! A finished argumentative essay.

Your essay should have just as awesome a skeleton as this plesiosaur does. (In other words: a ridiculously awesome skeleton)

Argumentative Essay Example: 5-Paragraph Style

It always helps to have an example to learn from. I've written a full 5-paragraph argumentative essay here. Look at how I state my thesis in paragraph 1, give supporting evidence in paragraphs 2 and 3, address a counterargument in paragraph 4, and conclude in paragraph 5.

Topic: Is it possible to maintain conflicting loyalties?

Paragraph 1

It is almost impossible to go through life without encountering a situation where your loyalties to different people or causes come into conflict with each other. Maybe you have a loving relationship with your sister, but she disagrees with your decision to join the army, or you find yourself torn between your cultural beliefs and your scientific ones. These conflicting loyalties can often be maintained for a time, but as examples from both history and psychological theory illustrate, sooner or later, people have to make a choice between competing loyalties, as no one can maintain a conflicting loyalty or belief system forever.

The first two sentences set the scene and give some hypothetical examples and stakes for the reader to care about.

The third sentence finishes off the intro with the thesis statement, making very clear how the author stands on the issue ("people have to make a choice between competing loyalties, as no one can maintain a conflicting loyalty or belief system forever." )

Paragraphs 2 and 3

Psychological theory states that human beings are not equipped to maintain conflicting loyalties indefinitely and that attempting to do so leads to a state called "cognitive dissonance." Cognitive dissonance theory is the psychological idea that people undergo tremendous mental stress or anxiety when holding contradictory beliefs, values, or loyalties (Festinger, 1957). Even if human beings initially hold a conflicting loyalty, they will do their best to find a mental equilibrium by making a choice between those loyalties—stay stalwart to a belief system or change their beliefs. One of the earliest formal examples of cognitive dissonance theory comes from Leon Festinger's When Prophesy Fails . Members of an apocalyptic cult are told that the end of the world will occur on a specific date and that they alone will be spared the Earth's destruction. When that day comes and goes with no apocalypse, the cult members face a cognitive dissonance between what they see and what they've been led to believe (Festinger, 1956). Some choose to believe that the cult's beliefs are still correct, but that the Earth was simply spared from destruction by mercy, while others choose to believe that they were lied to and that the cult was fraudulent all along. Both beliefs cannot be correct at the same time, and so the cult members are forced to make their choice.

But even when conflicting loyalties can lead to potentially physical, rather than just mental, consequences, people will always make a choice to fall on one side or other of a dividing line. Take, for instance, Nicolaus Copernicus, a man born and raised in Catholic Poland (and educated in Catholic Italy). Though the Catholic church dictated specific scientific teachings, Copernicus' loyalty to his own observations and scientific evidence won out over his loyalty to his country's government and belief system. When he published his heliocentric model of the solar system--in opposition to the geocentric model that had been widely accepted for hundreds of years (Hannam, 2011)-- Copernicus was making a choice between his loyalties. In an attempt t o maintain his fealty both to the established system and to what he believed, h e sat on his findings for a number of years (Fantoli, 1994). But, ultimately, Copernicus made the choice to side with his beliefs and observations above all and published his work for the world to see (even though, in doing so, he risked both his reputation and personal freedoms).

These two paragraphs provide the reasons why the author supports the main argument and uses substantiated sources to back those reasons.

The paragraph on cognitive dissonance theory gives both broad supporting evidence and more narrow, detailed supporting evidence to show why the thesis statement is correct not just anecdotally but also scientifically and psychologically. First, we see why people in general have a difficult time accepting conflicting loyalties and desires and then how this applies to individuals through the example of the cult members from the Dr. Festinger's research.

The next paragraph continues to use more detailed examples from history to provide further evidence of why the thesis that people cannot indefinitely maintain conflicting loyalties is true.

Paragraph 4

Some will claim that it is possible to maintain conflicting beliefs or loyalties permanently, but this is often more a matter of people deluding themselves and still making a choice for one side or the other, rather than truly maintaining loyalty to both sides equally. For example, Lancelot du Lac typifies a person who claims to maintain a balanced loyalty between to two parties, but his attempt to do so fails (as all attempts to permanently maintain conflicting loyalties must). Lancelot tells himself and others that he is equally devoted to both King Arthur and his court and to being Queen Guinevere's knight (Malory, 2008). But he can neither be in two places at once to protect both the king and queen, nor can he help but let his romantic feelings for the queen to interfere with his duties to the king and the kingdom. Ultimately, he and Queen Guinevere give into their feelings for one another and Lancelot—though he denies it—chooses his loyalty to her over his loyalty to Arthur. This decision plunges the kingdom into a civil war, ages Lancelot prematurely, and ultimately leads to Camelot's ruin (Raabe, 1987). Though Lancelot claimed to have been loyal to both the king and the queen, this loyalty was ultimately in conflict, and he could not maintain it.

Here we have the acknowledgement of a potential counter-argument and the evidence as to why it isn't true.

The argument is that some people (or literary characters) have asserted that they give equal weight to their conflicting loyalties. The refutation is that, though some may claim to be able to maintain conflicting loyalties, they're either lying to others or deceiving themselves. The paragraph shows why this is true by providing an example of this in action.

Paragraph 5

Whether it be through literature or history, time and time again, people demonstrate the challenges of trying to manage conflicting loyalties and the inevitable consequences of doing so. Though belief systems are malleable and will often change over time, it is not possible to maintain two mutually exclusive loyalties or beliefs at once. In the end, people always make a choice, and loyalty for one party or one side of an issue will always trump loyalty to the other.

The concluding paragraph summarizes the essay, touches on the evidence presented, and re-states the thesis statement.

How to Write an Argumentative Essay: 8 Steps

Writing the best argumentative essay is all about the preparation, so let's talk steps:

#1: Preliminary Research

If you have the option to pick your own argumentative essay topic (which you most likely will), then choose one or two topics you find the most intriguing or that you have a vested interest in and do some preliminary research on both sides of the debate.

Do an open internet search just to see what the general chatter is on the topic and what the research trends are.

Did your preliminary reading influence you to pick a side or change your side? Without diving into all the scholarly articles at length, do you believe there's enough evidence to support your claim? Have there been scientific studies? Experiments? Does a noted scholar in the field agree with you? If not, you may need to pick another topic or side of the argument to support.

#2: Pick Your Side and Form Your Thesis

Now's the time to pick the side of the argument you feel you can support the best and summarize your main point into your thesis statement.

Your thesis will be the basis of your entire essay, so make sure you know which side you're on, that you've stated it clearly, and that you stick by your argument throughout the entire essay .

#3: Heavy-Duty Research Time

You've taken a gander at what the internet at large has to say on your argument, but now's the time to actually read those sources and take notes.

Check scholarly journals online at Google Scholar , the Directory of Open Access Journals , or JStor . You can also search individual university or school libraries and websites to see what kinds of academic articles you can access for free. Keep track of your important quotes and page numbers and put them somewhere that's easy to find later.

And don't forget to check your school or local libraries as well!

#4: Outline

Follow the five-paragraph outline structure from the previous section.

Fill in your topic, your reasons, and your supporting evidence into each of the categories.

Before you begin to flesh out the essay, take a look at what you've got. Is your thesis statement in the first paragraph? Is it clear? Is your argument logical? Does your supporting evidence support your reasoning?

By outlining your essay, you streamline your process and take care of any logic gaps before you dive headfirst into the writing. This will save you a lot of grief later on if you need to change your sources or your structure, so don't get too trigger-happy and skip this step.

Now that you've laid out exactly what you'll need for your essay and where, it's time to fill in all the gaps by writing it out.

Take it one step at a time and expand your ideas into complete sentences and substantiated claims. It may feel daunting to turn an outline into a complete draft, but just remember that you've already laid out all the groundwork; now you're just filling in the gaps.

If you have the time before deadline, give yourself a day or two (or even just an hour!) away from your essay . Looking it over with fresh eyes will allow you to see errors, both minor and major, that you likely would have missed had you tried to edit when it was still raw.

Take a first pass over the entire essay and try your best to ignore any minor spelling or grammar mistakes—you're just looking at the big picture right now. Does it make sense as a whole? Did the essay succeed in making an argument and backing that argument up logically? (Do you feel persuaded?)

If not, go back and make notes so that you can fix it for your final draft.

Once you've made your revisions to the overall structure, mark all your small errors and grammar problems so you can fix them in the next draft.

#7: Final Draft

Use the notes you made on the rough draft and go in and hack and smooth away until you're satisfied with the final result.

A checklist for your final draft:

- Formatting is correct according to your teacher's standards

- No errors in spelling, grammar, and punctuation

- Essay is the right length and size for the assignment

- The argument is present, consistent, and concise

- Each reason is supported by relevant evidence

- The essay makes sense overall

#8: Celebrate!

Once you've brought that final draft to a perfect polish and turned in your assignment, you're done! Go you!

Be prepared and ♪ you'll never go hungry again ♪, *cough*, or struggle with your argumentative essay-writing again. (Walt Disney Studios)

Good Examples of Argumentative Essays Online

Theory is all well and good, but examples are key. Just to get you started on what a fully-fleshed out argumentative essay looks like, let's see some examples in action.

Check out these two argumentative essay examples on the use of landmines and freons (and note the excellent use of concrete sources to back up their arguments!).

The Use of Landmines

A Shattered Sky

The Take-Aways: Keys to Writing an Argumentative Essay

At first, writing an argumentative essay may seem like a monstrous hurdle to overcome, but with the proper preparation and understanding, you'll be able to knock yours out of the park.

Remember the differences between a persuasive essay and an argumentative one, make sure your thesis is clear, and double-check that your supporting evidence is both relevant to your point and well-sourced . Pick your topic, do your research, make your outline, and fill in the gaps. Before you know it, you'll have yourself an A+ argumentative essay there, my friend.

What's Next?

Now you know the ins and outs of an argumentative essay, but how comfortable are you writing in other styles? Learn more about the four writing styles and when it makes sense to use each .

Understand how to make an argument, but still having trouble organizing your thoughts? Check out our guide to three popular essay formats and choose which one is right for you.

Ready to make your case, but not sure what to write about? We've created a list of 50 potential argumentative essay topics to spark your imagination.

Courtney scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT in high school and went on to graduate from Stanford University with a degree in Cultural and Social Anthropology. She is passionate about bringing education and the tools to succeed to students from all backgrounds and walks of life, as she believes open education is one of the great societal equalizers. She has years of tutoring experience and writes creative works in her free time.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

9.3: The Argumentative Essay

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 58378

- Lumen Learning

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Examine types of argumentative essays

Argumentative Essays

You may have heard it said that all writing is an argument of some kind. Even if you’re writing an informative essay, you still have the job of trying to convince your audience that the information is important. However, there are times you’ll be asked to write an essay that is specifically an argumentative piece.

An argumentative essay is one that makes a clear assertion or argument about some topic or issue. When you’re writing an argumentative essay, it’s important to remember that an academic argument is quite different from a regular, emotional argument. Note that sometimes students forget the academic aspect of an argumentative essay and write essays that are much too emotional for an academic audience. It’s important for you to choose a topic you feel passionately about (if you’re allowed to pick your topic), but you have to be sure you aren’t too emotionally attached to a topic. In an academic argument, you’ll have a lot more constraints you have to consider, and you’ll focus much more on logic and reasoning than emotions.

Argumentative essays are quite common in academic writing and are often an important part of writing in all disciplines. You may be asked to take a stand on a social issue in your introduction to writing course, but you could also be asked to take a stand on an issue related to health care in your nursing courses or make a case for solving a local environmental problem in your biology class. And, since argument is such a common essay assignment, it’s important to be aware of some basic elements of a good argumentative essay.

When your professor asks you to write an argumentative essay, you’ll often be given something specific to write about. For example, you may be asked to take a stand on an issue you have been discussing in class. Perhaps, in your education class, you would be asked to write about standardized testing in public schools. Or, in your literature class, you might be asked to argue the effects of protest literature on public policy in the United States.

However, there are times when you’ll be given a choice of topics. You might even be asked to write an argumentative essay on any topic related to your field of study or a topic you feel that is important personally.

Whatever the case, having some knowledge of some basic argumentative techniques or strategies will be helpful as you write. Below are some common types of arguments.

Causal Arguments

- In this type of argument, you argue that something has caused something else. For example, you might explore the causes of the decline of large mammals in the world’s ocean and make a case for your cause.

Evaluation Arguments

- In this type of argument, you make an argumentative evaluation of something as “good” or “bad,” but you need to establish the criteria for “good” or “bad.” For example, you might evaluate a children’s book for your education class, but you would need to establish clear criteria for your evaluation for your audience.

Proposal Arguments

- In this type of argument, you must propose a solution to a problem. First, you must establish a clear problem and then propose a specific solution to that problem. For example, you might argue for a proposal that would increase retention rates at your college.

Narrative Arguments

- In this type of argument, you make your case by telling a story with a clear point related to your argument. For example, you might write a narrative about your experiences with standardized testing in order to make a case for reform.

Rebuttal Arguments

- In a rebuttal argument, you build your case around refuting an idea or ideas that have come before. In other words, your starting point is to challenge the ideas of the past.

Definition Arguments

- In this type of argument, you use a definition as the starting point for making your case. For example, in a definition argument, you might argue that NCAA basketball players should be defined as professional players and, therefore, should be paid.

https://assessments.lumenlearning.co...essments/20277

Essay Examples

- Click here to read an argumentative essay on the consequences of fast fashion . Read it and look at the comments to recognize strategies and techniques the author uses to convey her ideas.

- In this example, you’ll see a sample argumentative paper from a psychology class submitted in APA format. Key parts of the argumentative structure have been noted for you in the sample.

Link to Learning

For more examples of types of argumentative essays, visit the Argumentative Purposes section of the Excelsior OWL .

Contributors and Attributions

- Argumentative Essay. Provided by : Excelsior OWL. Located at : https://owl.excelsior.edu/rhetorical-styles/argumentative-essay/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of a man with a heart and a brain. Authored by : Mohamed Hassan. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : pixabay.com/illustrations/decision-brain-heart-mind-4083469/. License : Other . License Terms : pixabay.com/service/terms/#license

10.5 Writing Process: Creating a Position Argument

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Demonstrate brainstorming processes and tools as means to discover topics, ideas, positions, and details.

- Apply recursive strategies for organizing drafting, collaborating, peer reviewing, revising, rewriting, and editing.

- Compose a position argument that integrates the writer’s ideas with those from appropriate sources.

- Give and act on productive feedback to works in progress.

- Apply or challenge common conventions of language or grammar in composing and revising.

Now is the time to try your hand at writing a position argument. Your instructor may provide some possible topics or a singular topic. If your instructor allows you to choose your own topic, consider a general subject you feel strongly about and whether you can provide enough support to develop that subject into an essay. For instance, suppose you think about a general subject such as “adulting.” In looking back at what you have learned while becoming an adult, you think of what you wish you had known during your early teenage years. These thoughts might lead you to brainstorm about details of the effects of money in your life or your friends’ lives. In reviewing your brainstorming, you might zero in on one topic you feel strongly about and think it provides enough depth to develop into a position argument. Suppose your brainstorming leads you to think about negative financial concerns you or some of your friends have encountered. Thinking about what could have helped address those concerns, you decide that a mandated high school course in financial literacy would have been useful. This idea might lead you to formulate your working thesis statement —first draft of your thesis statement—like this: To help students learn how to make sensible financial decisions, a mandatory class in financial literacy should be offered in high schools throughout the country.

Once you decide on a topic and begin moving through the writing process, you may need to fine-tune or even change the topic and rework your initial idea. This fine-tuning may come as you brainstorm, later when you begin drafting, or after you have completed a draft and submitted it to your peers for constructive criticism. These possibilities occur because the writing process is recursive —that is, it moves back and forth almost simultaneously and maybe even haphazardly at times, from planning to revising to editing to drafting, back to planning, and so on.

Summary of Assignment

Write a position argument on a controversial issue that you choose or that your instructor assigns to you. If you are free to choose your own topic, consider one of the following:

- The legal system would be strengthened if ______________________.

- The growing use of technology in college classrooms is weakening _____________.

- For safety reasons, public signage should be _________________.

- For entrance into college, standardized testing _________________________.

- In relation to the cost of living, the current minimum wage _______________________.

- During a pandemic, America __________________________.

- As a requirement to graduate, college students __________________________.

- To guarantee truthfulness of their content, social media platforms have the right to _________________.

- To ensure inclusive and diverse representation of people of all races, learning via virtual classrooms _________________.

- Segments of American cultures have differing rules of acceptable grammar, so in a college classroom ___________________.

In addition, if you have the opportunity to choose your own topic and wish to search further, take the lead from trailblazer Charles Blow and look to media for newsworthy “trends.” Find a controversial issue that affects you or people you know, and take a position on it. As you craft your argument, identify a position opposing yours, and then refute it with reasoning and evidence. Be sure to gather information on the issue so that you can support your position sensibly with well-developed ideas and evidence.

Another Lens. To gain a different perspective on your issue, consider again the people affected by it. Your position probably affects different people in different ways. For example, if you are writing that the minimum wage should be raised, then you might easily view the issue through the lens of minimum-wage workers, especially those who struggle to make ends meet. However, if you look at the issue through the lens of those who employ minimum-wage workers, your viewpoint might change. Depending on your topic and thesis, you may need to use print or online sources to gain insight into different perspectives.

For additional information about minimum-wage workers, you could consult

- printed material available in your college library;

- databases in your college library; and

- pros and cons of raising the minimum wage;

- what happens after the minimum wage is raised;

- how to live on a minimum-wage salary;

- how a raise in minimum wage is funded; and

- minimum wage in various U.S. states.

To gain more insight about your topic, adopt a stance that opposes your original position and brainstorm ideas from that viewpoint. Begin by gathering evidence that would help you refute your previous stance and appeal to your audience.

Quick Launch: Working Thesis Frames and Organization of Ideas

After you have decided on your topic, the next step is to arrive at your working thesis. You probably have a good idea of the direction your working thesis will take. That is, you know where you stand on the issue or problem, but you are not quite sure of how to word your stance to share it with readers. At this point, then, use brainstorming to think critically about your position and to discover the best way to phrase your statement.

For example, after reading an article discussing different state-funded community college programs, one student thought that a similar program was needed in Alabama, her state. However, she was not sure how the program worked. To begin, she composed and answered “ reporters’ questions ” such as these:

- What does a state-funded community college program do? pays for part or all of the tuition of a two-year college student

- Who qualifies for the program? high school graduates and GED holders

- Who benefits from this? students needing financial assistance, employers, and Alabama residents

- Why is this needed? some can’t afford to go to college; tuition goes up every year; colleges would be more diverse if everyone who wanted to go could afford to go

- Where would the program be available? at all public community colleges

- When could someone apply for the program? any time

- How can the state fund this ? use lottery income, like other states

The student then reviewed her responses, altered her original idea to include funding through a lottery, and composed this working thesis:

student sample text To provide equal educational opportunities for all residents, the state of Alabama should create a lottery to completely fund tuition at community colleges. end student sample text

Remember that a strong thesis for a position should

- state your stance on a debatable issue;

- reflect your purpose of persuasion; and

- be based on your opinion or observation.

When you first consider your topic for an argumentative work, think about the reasoning for your position and the evidence you will need—that is, think about the “because” part of your argument. For instance, if you want to argue that your college should provide free Wi-Fi for every student, extend your stance to include “because” and then develop your reasoning and evidence. In that case, your argument might read like this: Ervin Community College should provide free Wi-Fi for all students because students may not have Internet access at home.

Note that the “because” part of your argument may come at the beginning or the end and may be implied in your wording.

As you develop your thesis, you may need help funneling all of your ideas. Return to the possibilities you have in mind, and select the ideas that you think are strongest, that recur most often, or that you have the most to say about. Then use those ideas to fill in one of the following sentence frames to develop your working thesis. Feel free to alter the frame as necessary to fit your position. While there is no limit to the frames that are possible, these may help get you started.

________________ is caused/is not caused by ________________, and _____________ should be done.

Example: A declining enrollment rate in college is caused by high tuition rates, and an immediate freeze on the cost of tuition should be applied.

______________ should/should not be allowed (to) ________________ for a number of reasons.

Example: People who do not wear masks during a pandemic should not be allowed to enter public buildings for a number of reasons.

Because (of) ________________, ___________________ will happen/continue to happen.

Example: Because of a lack of emphasis on STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, the Arts, and Mathematics) education in public schools, America will continue to lag behind many other countries.

_____________ is similar to/nothing like ________________ because ______________.

Example: College classes are nothing like high school classes because in college, more responsibility is on the student, the classes are less frequent but more intense, and the work outside class takes more time to complete.

______________ can be/cannot be thought of as __________________ because ______________.

Example: The Black Lives Matter movement can be thought of as an extension of the Civil Rights movement from the 1950s and 1960s because it shares the same mission of fighting racism and ending violence against Black people.

Next, consider the details you will need to support your thesis. The Aristotelian argument structure, named for the Greek philosopher Aristotle , is one that may help you frame the draft of your position argument. For this method, use something like the following chart. In Writing Process: Creating a Position Argument, you will find a similar organizer that you can copy and use for your assignment.

Drafting: Rhetorical Appeals and Types of Supporting Evidence

To persuade your audience to support your position or argument, consider various rhetorical appeals— ethos, logos, pathos, and kairos—and the types of evidence to support your sound reasoning. See Reasoning Strategies: Improving Critical Thinking for more information on reasoning strategies and types of evidence.

Rhetorical Appeals

To establish your credibility, to show readers you are trustworthy, to win over their hearts, and to set your issue in an appropriate time frame to influence readers, consider how you present and discuss your evidence throughout the paper.

- Appeal to ethos . To establish credibility in her paper arguing for expanded mental health services, a student writer used these reliable sources: a student survey on mental health issues, data from the International Association of Counseling Services (a professional organization), and information from an interview with a campus mental health counselor.

- Appeal to logos . To support her sound reasoning, the student writer approached the issue rationally, using data and credible evidence to explain the current situation and its effects.

- Appeal to pathos . To show compassion and arouse audience empathy, the student writer shared the experience of a student on her campus who struggled with anxiety and depression.

- Appeal to kairos . To appeal to kairos, the student emphasized the immediate need for these services, as more students are now aware of their particular mental health issues and trying to deal with them.

The way in which you present and discuss your evidence will reflect the appeals you use. Consider using sentence frames to reflect specific appeals. Remember, too, that sentence frames can be composed in countless ways. Here are a few frames to get you thinking critically about how to phrase your ideas while considering different types of appeals.

Appeal to ethos: According to __________________, an expert in ______________, __________________ should/should not happen because ________________________.

Appeal to ethos: Although ___________________is not an ideal situation for _________________, it does have its benefits.

Appeal to logos: If ____________________ is/is not done, then understandably, _________________ will happen.

Appeal to logos: This information suggests that ____________________ needs to be investigated further because ____________________________.

Appeal to pathos: The story of _____________________ is uplifting/heartbreaking/hopeful/tragic and illustrates the need for ____________________.

Appeal to pathos: ___________________ is/are suffering from ________________, and that is something no one wants.

Appeal to kairos: _________________ must be addressed now because ________________ .

Appeal to kairos: These are times when ______________ ; therefore, _____________ is appropriate/necessary.

Types of Supporting Evidence

Depending on the point you are making to support your position or argument, certain types of evidence may be more effective than others. Also, your instructor may require you to include a certain type of evidence. Choose the evidence that will be most effective to support the reasoning behind each point you make to support your thesis statement. Common types of evidence are these:

Renada G., a junior at Powell College South, worked as a waitress for 15 hours a week during her first three semesters of college. But in her sophomore year, when her parents were laid off during the pandemic, Renada had to increase her hours to 35 per week and sell her car to stay in school. Her grades started slipping, and she began experiencing symptoms of depression and anxiety. When she called the campus health center to make an appointment for counseling, Renada was told she would have to wait two weeks before she could be seen.

Here is part of how Lyndon B. Johnson defined the Great Society: “But most of all, the Great Society is not a safe harbor, a resting place, a final objective, a finished work. It is a challenge constantly renewed, beckoning us toward a destiny where the meaning of our lives matches the marvelous products of our labor.”

Bowen Lake is nestled in verdant foothills, lush with tall grasses speckled with wildflowers. Around the lake, the sweet scent of the purple and yellow flowers fills the air, and the fragrance of the hearty pines sweeps down the hillsides in a westerly breeze. Wood frogs’ and crickets’ songs suddenly stop, as the blowing of moose calling their calves echoes across the lake’s soundless surface. Or this was the scene before the deadly destruction of fires caused by climate change.

When elaborating on America’s beauty being in danger, Johnson says, “The water we drink, the food we eat, the very air that we breathe, are threatened with pollution. Our parks are overcrowded, our seashores overburdened. Green fields and dense forests are disappearing.”

Speaking about President Lyndon B. Johnson and the Vietnam War, noted historian and Johnson biographer Doris Kearns Goodwin said, “It seemed the hole in his heart from the loss of work was too big to fill.”

Charles Blow has worked at the Shreveport Times , The Detroit News , National Geographic , and The New York Times .

When interviewed by George Rorick and asked about the identities of his readers, Charles Blow said that readers’ emails do not elaborate on descriptions of who the people are. However, “the kinds of comments that they offer are very much on the thesis of the essay.”

In his speech, Lyndon B. Johnson says, “The Great Society is a place where every child can find knowledge to enrich his mind and to enlarge his talents.”

To support the need for change in classrooms, Johnson uses these statistics: “Each year more than 100,000 high school graduates, with proved ability, do not enter college because they cannot afford it. And if we cannot educate today’s youth, what will we do in 1970 when elementary school enrollment will be five million greater than 1960?”

- Visuals : graphs, photographs, charts, or maps used in addition to written or spoken information.

Brainstorm for Supporting Points

Use one or more brainstorming techniques, such as a web diagram as shown in Figure 10.8 or the details generated from “because” statements, to develop ideas or particular points in support of your thesis. Your goal is to get as many ideas as possible. At this time, do not be concerned about how ideas flow, whether you will ultimately use an idea (you want more ideas than will end up in your finished paper), spelling, or punctuation.

When you have finished, look over your brainstorming. Then circle three to five points to incorporate into your draft. Also, plan to answer “ reporters’ questions ” to provide readers with any needed background information. For example, the student writing about the need for more mental health counselors on her campus created and answered these questions:

What is needed? More mental health counseling is needed for Powell College South.

Who would benefit from this? The students and faculty would benefit.

- Why is this needed? The college does not have enough counselors to meet all students’ needs.

- Where are more counselors needed? More counselors are needed at the south campus.

- When are the counselors needed? Counselors need to be hired now and be available both day and night to accommodate students’ schedules.

- How can the college afford this ? Instead of hiring daycare workers, the college could use students and faculty from the Early Childhood Education program to run the program and use the extra money to pay the counselors.

Using Logic

In a position argument, the appropriate use of logic is especially important for readers to trust what you write. It is also important to look for logic in material you read and possibly cite in your paper so that you can determine whether writers’ claims are reasonable. Two main categories of logical thought are inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning .

- Inductive reasoning moves from specific to broad ideas. You begin by collecting details, observations, incidents, or facts; examining them; and drawing a conclusion from them. Suppose, for example, you are writing about attendance in college classes. For three weeks, you note the attendance numbers in all your Monday, Wednesday, and Friday classes (specific details), and you note that attendance is lower on Friday than on the other days (a specific detail). From these observations, you determine that many students prefer not to attend classes on Fridays (your conclusion).

- Deductive reasoning moves from general to specific ideas. You begin with a hypothesis or premise , a general concept, and then examine possibilities that would lead to a specific and logical conclusion. For instance, suppose you think that opportunities for foreign students at your college are inadequate (general concept). You examine the specific parts of that concept (e.g., whether your college provides multicultural clubs, help with language skills, or work-study opportunities) and determine that those opportunities are not available. You then determine that opportunities for foreign students are lacking at your college.

Logical Fallacies and Propaganda

Fallacies are mistakes in logic. Readers and writers should be aware of these when they creep into writing, indicating that the points the writers make may not be valid. Two common fallacies are hasty generalizations and circular arguments. See Glance at Genre: Rhetorical Strategies for more on logical fallacies.

- A hasty generalization is a conclusion based on either inadequate or biased evidence. Consider this statement: “Two students in Math 103 were nervous before their recent test; therefore, all students in that class must have text anxiety.” This is a hasty generalization because the second part of the statement (the generalization about all students in the class) is inadequate to support what the writer noted about only two students.

- A circular argument is one that merely restates what has already been said. Consider this statement: “ The Hate U Give is a well-written book because Angie Thomas, its author, is a good novelist.” The statement that Thomas is a good novelist does not explain why her book is well written.

In addition to checking work for fallacies, consider propaganda , information worded so that it endorses a particular viewpoint, often of a political nature. Two common types of propaganda are bandwagon and fear .

- In getting on the bandwagon , the writer encourages readers to conform to a popular trend and endorse an opinion, a movement, or a person because everyone else is doing so. Consider this statement: “Everyone is behind the idea that 7 a.m. classes are too early and should be changed to at least 8 a.m. Shouldn’t you endorse this sensible idea, too?”