What is self-plagiarism and what does it have to do with academic integrity?

Emerging trends series

By completing this form, you agree to Turnitin's Privacy Policy . Turnitin uses the information you provide to contact you with relevant information. You may unsubscribe from these communications at any time.

Self-plagiarism—sometimes known as “ duplicate plagiarism ”—is a term for when a writer recycles work for a different assignment or publication and represents it as new.

For students, this may involve recycling an essay or large portions of text written for a prior course and resubmitting it to fulfill a different assignment in a different course. For researchers, this involves recycling prior published work and submitting it for publication to another journal without quotes or citation or acknowledgment of the prior work. Duplicate plagiarism, or “Submitting the same manuscript to multiple journals is widely considered unethical and would also likely constitute copyright infringement and violate the author-publisher contract of most journals” ( Moskowitz, 2021 ).

The broader act of recycling one’s own work in some areas like scientific research, which the Text Recycling Project expands upon, is more nuanced; in research, work is often cumulative and builds on prior research. In those cases, researchers may engage in developmental recycling, generative recycling, or adaptive publication to publish later work or revise the writing for a broader audience—all while citing prior publication ( Moskowitz, 2019 ).

Students who aren’t as familiar with this form of academic misconduct often don’t have a deeper understanding of academic integrity. Because they are reusing their own work, they may feel that this isn’t plagiarism or misconduct at all.

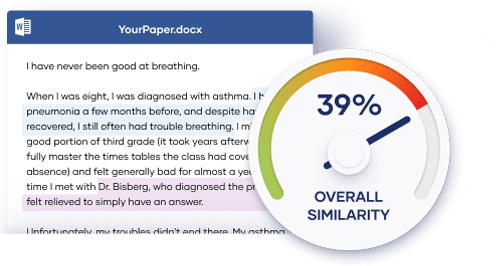

They may be stunned to find that they have, for instance, a higher similarity score when submitting to Turnitin, as it will match against a prior submission (their own). Students may then ask for that older paper to be deleted, not knowing they have engaged in duplicate plagiarism. In many cases, this is an opportunity to increase student understanding of academic integrity.

Academic integrity entails honesty and original work. But it also includes a deep understanding of the importance of citation and academic respect. Even if the paper is the student’s own, the work ought to be original for that particular assignment; duplicate plagiarism is a short-cut solution that hampers learning.

For researchers, duplicate plagiarism (wholesale republication of entire papers without citation) violates copyright and can affect the i mpact factor of both journals and researchers . A decrease in the impact factor detrimentally affects academic reputation and future publication possibilities.

While there are many instances of intentional duplicate plagiarism, most cases of self-plagiarism are unintentional and can be remedied with explicit instruction on the core principles of academic integrity, citation, and the prioritization of original work.

Many similarity check tools like iThenticate and Feedback Studio curtail self-plagiarism and also present learning opportunities to transform instances of plagiarism into teachable moments .

A more sophisticated understanding of academic integrity will help curtail self-plagiarism for both students and researchers. Researchers can mitigate the consequences of duplicate plagiarism by citing their previously published work. Having a deeper understanding of academic integrity avoids embarrassment and upholds learning as well as academic reputations.

Furthermore, designing assessments specific to your classroom can also help curtail self-plagiarism; when essay prompts are tailored to your classroom discussion, prior student work will likely not be relevant and be avoided.

We hope this post helps you on your academic integrity journey.

Self-Plagiarism: How to Define It and Why You Should Avoid It

What is self-plagiarism, and why is self-plagiarism wrong? Understand the ethical (and practical) reasons to avoid this behavior in your research writing.

Updated on February 21, 2024

In the process of publishing, each new paper builds on previous work. However, it's important to note that rules about quoting and citing previous work (to avoid plagiarism ) apply equally to one's own writing. The concept of self-plagiarism can lead to many questions , but here is a definition and three reasons to avoid it in your research papers.

What is self-plagiarism?

Self-plagiarism is commonly described as recycling or reusing one's own specific words from previously published texts. While it doesn't cross the line of true theft of others' ideas, it nonetheless can create issues in the scholarly publishing world. Beyond verbatim sections of text, self-plagiarism can also refer to the publication of identical papers in two places (sometimes called "duplicate publication"). Moreover, it is best practice to cite your previous work thoroughly, even if you are simply revisiting an old idea or a previously published observation.

In short, self-plagiarism is any attempt to take any of your own previously published text, papers, or research results and make it appear brand new.

"Self-plagiarism is not usually an accident so much as a misunderstanding of journal copyrights," says Kim Yasutis, Ph.d. "Authors, particularly in certain fields and certain cultures, tend to think of text they have written as theirs in perpetuity. However, once they publish in a journal, they have almost always transferred copyright to another journal. At such a time, that text is no longer theirs from a right to publish perspective. So while authors might not think there’s anything ethically wrong with using “their own” text, a journal puts itself in legal jeopardy if it publishes text that another journal owns the copyright to."

Why is self-plagiarism wrong?

Although some forms of self-plagiarism may seem harmless, the rationale for avoiding this practice is threefold, ranging from the philosophical to the practical:

1. The fundamental role of research papers

The broadest reason to avoid self-plagiarism deals with the integrity of the research record, and of scientific discovery as a whole. It is widely understood that each published manuscript will include new knowledge and results that advance our understanding of the world. When your manuscript contains uncited recycled information, you are countering the unspoken assumption that you are presenting entirely new discoveries.

"Salami slicing" data, reusing old material to publish again, and duplicate publication erode your standing in your field and also the public's trust in research and science more broadly.

2. Publisher copyright - your own words may not belong to you

It is important to note that the standard process of publication in many journals includes ceding copyright of the finished paper to the publisher. While you are still the intellectual owner of the ideas and results, the publication is property of the journal. As such, reuse of that material without citation and/or permission is not acceptable. While this is counterintuitive, in the eyes of the law, reusing your own words is copyright infringement, even if you wrote them.

Open access journals commonly use Creative Commons licenses allowing for reuse with attribution. In these cases, reuse of your own words is acceptable, but it is always necessary to cite the original publication.

3. Journals will catch it and your publication process will be delayed or blocked

The vast majority of scholarly journals use software like iThenticate® to screen for plagiarized work upon submission. If you have copied text from a previously published paper, it will be flagged during this process. Even if you are not rejected for the issue, it will cause a delay as the editor asks you questions and you rewrite or otherwise more clearly identify reused material.

The most practical reason to avoid self-plagiarism is actually the most common reason it occurs in the first place: to save you time while trying to get published.

How to avoid self-plagiarism

Luckily, self-plagiarism can be easily avoided. Instead of repeating what you've already stated in another manuscript, just reference your previous work.

"Mostly avoiding self plagiarism can be done by referencing previous papers rather than recycling text (most commonly in sciences in the methods section)," says Yasutis. "Second tip is simply to open an entirely new document when writing each paper, rather than starting from a previous draft of something else"

At AJE, we know ethical reporting of new results is fundamental to the advancement of knowledge. Please contact us with any questions.

Ben Mudrak, PhD

Kimberly Yasutis, PhD

Research Communication Partner II

See our "Privacy Policy"

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Biochem Med (Zagreb)

- v.23(2); 2013 Jun

How do we handle self-plagiarism in submitted manuscripts?

Vesna Šupak-smolčić.

1 Clinical Institute of Laboratory Diagnostics, Rijeka Clinical Hospital Center, Rijeka, Croatia

Lidija Bilić-Zulle

2 Department of Medical Informatics, Rijeka University School of Medicine, Rijeka, Croatia

Self-plagiarism is a controversial issue in scientific writing and presentation of research data. Unlike plagiarism, self-plagiarism is difficult to interpret as intellectual theft under the justification that one cannot steal from oneself. However, academics are concerned, as self-plagiarized papers mislead readers, do not contribute to science, and bring undeserved credit to authors. As such, it should be considered a form of scientific misconduct. In this paper, we explain different forms of self-plagiarism in scientific writing and then present good editorial policy toward questionable material. The importance of dealing with self-plagiarism is emphasized by the recently published proposal of Text Recycling Guidelines by the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

Introduction

In terms of research integrity, journal editors very often find themselves in the gray zone of publication ethics. In fact, black-and-white situations are rare in responsible decision making. Self-plagiarism is one of those kinds of issues that can vary from being a clear algorithm-based situation to a complex and undefined case. If plagiarism means stealing other people’s ideas or words and presenting them as one’s own, does self-plagiarism mean stealing one’s own words? If the words were a researcher’s in the first place, how can the use of one’s own prior published words be defined as intellectual theft? Generally, self-plagiarism is a form of plagiarism, and it should be treated as one. However, the absurd notion of stealing from oneself can provoke such a peculiar feeling that it should be treated differently. Self-plagiarized publications do not contribute scientific value, they merely increase the number of papers published without justification in scientific research and gain undeserved benefit to authors in the form of artificially increased number of published papers. For perspective, the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) recently proposed new guidelines for dealing with the delicate issue of self-plagiarism ( 1 ).

Forms of self-plagiarism

To clarify the ethical complexities of self-plagiarism and explain the ways to avoid it, scientists have been trying to define self-plagiarism and to describe its possible forms ( 2 , 3 ). Miguel Roig published a paper in Biochemia Medica with an emphasis on self-plagiarism; he distinguished four types of self-plagiarism: duplicate (redundant) publication, augmented publication, segmented publication, and text recycling ( 2 ). However, cases of suspected self-plagiarism do not always fall into one specific group, and unfortunately, universal rules have not been established for each group. The given systematization of self-plagiarism forms is only for the academic purpose of easier interpretation. Moreover, in some sources text-recycling and self-plagiarism are considered synonyms ( 1 ). Editors treat each case individually, but proposed guidelines, such as those in COPE flowcharts, offer great help. This paper intends to describe possible journal policies for each of those four potential groups, anchored on the new COPE guidelines.

Duplicate publication

Duplicate or redundant publication occurs when an author submits identical or almost identical manuscripts to two different journals. During the submission process, most journals request that authors clearly state whether they have already published this or a similar manuscript or whether this manuscript is currently being considered for publication in another journal. If further analysis reveals a major overlap with an author’s former work, then such a submitted manuscript can be considered a duplicate publication (same data, results, discussion). Editors can deal with such a case following the COPE flowchart for handling a submitted manuscript suspected of being a duplicate (redundant) publication ( 4 ). COPE flowcharts can be accessed from the official COPE web page ( http://www.publicationethics.org ) and are available to both editors and authors.

Augmented publication

Augmented publication occurs when authors add additional data to already published data and submit the new manuscript with new, recalculated results, often with a different title and adjusted study aims. This kind of self-plagiarism is difficult to detect because it is usually not a case of verbatim word plagiarism, which can be easily detected by plagiarism detection software. In most cases of augmented manuscripts, the major overlap is seen within the methods section. As such, editors and readers can be misled to consider it as technical (self) plagiarism, which is usually not sanctioned with the same strictness as plagiarism of other parts of the paper. Nevertheless, if a submitted manuscript shows substantial overlap in the methods section with the author’s previous work, then the editor can consider this manuscript for publication only under the following circumstances:

- the author refers to his previous work,

- methods cannot be written in any other form without altering comprehensibility,

- the author clearly states that the new manuscript contains data from a previous publication.

Segmented publication

Segmented or “salami-sliced” publication refers to the case where two or more papers are derived from the same experiment. Similar to augmented publications, salami-sliced publications are also difficult to detect, and revelation of such act, absent text similarity, is possible only on the hint of reviewers or editors. From the research integrity point of view, this kind of publication generally misleads readers as it prevents them from appreciating the big picture of the overall study, which might be completely different from that seen in the presented segment. Final decision on manuscript acceptance is again on the editor’s shoulders but must also be anchored on the condition of inevitable revision, e.g., the author must be asked to refer to his previous publication and explain reasonably the connection of the segmented paper to his previously published work.

Text recycling

Text recycling is exactly what it says: using large portions of one’s own already published text in a new manuscript. This kind of self-plagiarism is easily detected by plagiarism detection software. Despite all alleged reasons that perpetrators of such misconduct give to justify their actions, in most cases it is simply “intellectual laziness”, as proposed by Roig ( 2 ). For journal editors, this kind of situation can be handled following COPE guidelines ( 4 ).

Copyright terms

An additional issue important for dealing with cases of self-plagiarism is the authors’ conscious violation of copyright terms. In most cases, authors sign statements of copyright transfer to journal publishers. Thus, aside from being ethically questionable, self-plagiarism involves a legal issue. To simplify, an author’s words, once published, do not belong to him anymore. However, cases of legal prosecution of self-plagiarists have been few ( 3 ).

Editor’s decision

Ultimately, the editor decides how much similarity between a submitted manuscript and a prior one is too much. Apart from the similarity percentage, the citation of the original article could be helpful for decision making. Omitting the original article from the list of references implies an author’s intention to withhold information and conceal mis-behavior. In any case, self-plagiarized material should not be published.

The proposed new COPE guidelines define two distinct situations: when to propose revision and when to reject a submitted manuscript ( 1 ).

Based on the editorial policy of Biochemia Medica , upon detection of self-plagiarism, a submitted manuscript can be considered for publication only if it contains relevant new data and will contribute to overall scientific knowledge. Additional conditions have to be met:

- When text similarity is observed with an author’s previous publication, and the original publication is cited, the submitted manuscript has to be revised, with the questionable parts corrected. Overlaps within the methods section can be tolerated, but the cut-off percentage is for the editor to decide. Similarities in the introduction section can be approached differently from the treatment of overlaps in the discussion and conclusion sections.

- When text similarity with an author’s previous publication is seen, and the original publication is not cited, editors will oblige the author to correct the plagiarized text in the submitted manuscript and to cite the original article, as well as to point out new information in the submitted article.

Editors should reject the submitted manuscript when:

- There are significant portions of self-plagiarized text. The value of “significant” is determined by each editor and re-evaluated on a case-to-case basis.

- Plagiarized text contains already published data (not only methods section), and additional or relevant new data are absent. Publishing such manuscripts offers no scientific contribution.

- Self-plagiarized text covers major sections of the discussion and conclusion.

- There is obvious violation of copyright transfer.

Similar actions are proposed when self-plagiarism is detected after publication. Editors should analyze the published paper and decide whether a corrected article or retraction needs to be published. An additional consideration has to be made on the article’s publication date, as approaches toward self-plagiarism have been developing through the years. In general, corrective actions need not be taken if the article in question does not present duplicated data and has been published before 2004 ( 1 ). More detailed information on how to deal with cases of already published self-plagiarized articles are available from “COPE flowcharts for dealing with duplicate publications in a published article” and “COPE retraction guidelines” ( 5 , 6 ).

Editors in Biochemia Medica embrace the highest standards of research integrity and good editorial practice and will process all submitted manuscripts in order to detect all forms of plagiarism and self-plagiarism. Introducing research integrity editor and the strict policy of checking all submitted manuscripts were recently established ( 7 ). The high quality of the journal is our obligation toward our readers. Thus, we call upon all authors and future authors to ensure responsible writing and check with their conscience as well as their manuscripts prior to submission.

Potential conflict of interest

None declared.

UCL Doctoral School

- Self-Plagiarism

Guidance on incorporating published work in your thesis

How you can include published work in your thesis and avoid self-plagiarism

Doctoral candidates who are worried about what they can include in their thesis can follow this guidance. It covers the inclusion of previously published papers and how to integrate them properly.

Publishing first, then submitting thesis for examination

If you've published before submitting your thesis:

- an appropriate citation of the original source in the relevant Chapter; and

- completing the UCL Research Paper Declaration form – this should be embedded after the Acknowledgments page in the thesis.

- Before using figures, table sheets, or parts of the text, find out from the editor of the journal if you transferred the copyrights when you submitted the paper.

- When in doubt, when you do not own copyright, get formal approval from copyright owners to re-use the material (this is frequently done for previously published data and figures to be included in a doctoral thesis; please see more information on the UCL Copyright advice website ).

- ensure the style matches that of the rest of the thesis, both in formatting and content,

- add additional information/context where beneficial, such as additional background/relevant literature, more detailed methods,

- offer additional data not included in the publication, such as preliminary data, null findings, anything included in supplementary materials.

- If you worked together with co-authors, your (and their) contributions to the publication should be specified in the UCL Research Paper Declaration form.

Examples of including previously published work in your thesis

After gaining approval from the copyright holder, you would be allowed to copy and paste sections from the published paper into your thesis.

You might make minor edits to the text to ensure that it fits the overall style of your thesis (e.g. changing “We” to “I”, where appropriate) and that it is written in your voice (see bullet point on ‘Initial drafts of papers’ below).

You might also incorporate additional text/figures/Tables that did not appear in the original publication.

Unacceptable

You cannot embed the unedited pdf of the published paper into your thesis.

You also cannot copy and paste the entire paper without making any attempt to match the style to the rest of the thesis.

Submitting thesis first (and the degree is successfully awarded) and published after

If your thesis is published first, then this must be declared to a journal publisher so that you can check with the editor about the acceptability of including part of your thesis.

You must make sure that you have cited the original source correctly (your thesis for example) and acknowledged yourself as author. Where possible, you could also provide a link.

This applies not just to reproducing your own material but also to ideas which you have previously published elsewhere.

Tips for reusing material in final thesis

We strongly recommend you write your upgrade document (and/or any progression documents) in the same style and format as you would your final thesis. This will help you plan the format of your final thesis early and you can then reuse as much of your upgrade material in your final thesis as makes sense.

Initial drafts of papers

We strongly recommend you keep your initial drafts of papers for use in your final thesis; this way it is written in your voice (not that of your supervisors, co-authors, or journal editor) and will be less likely to affect any copyright issues with the publisher. This does not mean you cannot incorporate supervisor corrections; however, all text should be written by you and not subject to vast rewriting/editing by others as is often the case with journal publications. You should still cite your published work where relevant.

Plan your thesis structure and project timings carefully from the start

This means considering thesis structure, time of upgrade/progression reviews, and, if appropriate, which chapters might be turned into publications and when.

Prioritise the thesis over any other priorities

Furthermore, as you approach the final months before your submission deadline (which you should check carefully with your supervisory team and funder as expectations may vary), we strongly encourage you to prioritise the thesis over any other conflicting priorities, e.g. internships, publications, etc…

Remember to follow these guidelines to ensure the appropriate use of published work in your doctoral thesis while avoiding self-plagiarism.

What is Self-Plagiarism

The UCL Academic Manual describes self-plagiarism as:

“The reproduction or resubmission of a student’s own work which has been submitted for assessment at UCL or any other institution. This does not include earlier formative drafts of the particular assessment, or instances where the department has explicitly permitted the re-use of formative assessments but does include all other formative work except where permitted.”

Read about this in more detail in Chapter 6, Section 9.2d of the UCL Academic Manual page .

How self-plagiarism applies to Doctoral Students

Re-use of material already used for a previous degree.

A research student commits self-plagiarism if they incorporate material (text, data, ideas) from a previous academic degree (e.g., Master's of Undergraduate) submission, whether at UCL or another institution, into their final these without explicit declaration.

Note on Upgrades

The upgrade report is not published nor is it used to confer a degree, and is therefore excluded from the above definition of “material”.

In effect, the upgrade report (and any other progression reviews) is a form of “thesis draft” owned by the student and we encourage the reuse of material in the upgrade report in the final thesis where relevant.

As a result, material written by yourself can be used both in publications and your final thesis, and the self-plagiarism rule does not apply here. However, since your final thesis will be ‘published’ online, there are several rules you must follow.

For additonal detail, visit the UCL Discovery web page .

Links to forms

UCL Research Paper Declaration Form for including published material in your thesis (to be embedded after the Acknowledgements page).

- Form in MS Word format (DOCX)

- Form in LaTeX format (TEX) , thanks to David Sheard, Dept of Mathematics

- Form in PDF preview (PDF)

Helpful resources

- Step-by-step guide and FAQs on publishing doctoral work

- Information about your own copyright

- Information on online copy of your thesis

Prevent plagiarism, run a free plagiarism check.

- Knowledge Base

- What Is Self-Plagiarism? | Definition & How to Avoid It

What Is Self-Plagiarism? | Definition & How to Avoid It

Published on 9 December 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on 26 July 2022.

Plagiarism often involves using someone else’s words or ideas without proper citation , but you can also plagiarise yourself. Self-plagiarism means reusing work that you have already published or submitted for a class. It can involve:

- Resubmitting an entire paper

- Copying or paraphrasing passages from your previous work

- Recycling previously collected data

- Separately publishing multiple articles about the same research

Self-plagiarism misleads your readers by presenting previous work as completely new and original. If you want to include any text, ideas, or data that you already submitted in a previous assignment, be sure to inform your readers by citing yourself .

Table of contents

Examples of self-plagiarism, why is self-plagiarism wrong, how to cite yourself, how do educational institutions detect self-plagiarism, frequently asked questions about plagiarism.

You may be committing self-plagiarism if you:

- Submit an assignment from a previous academic year to a current class

- Recycle parts of an old assignment without citing it (e.g., copy-pasting sections or paragraphs from previously submitted work)

- Use a dataset from a previous study (published or not) without letting your reader know

- Submit a manuscript for publication containing data, conclusions, or passages that have already been published without citing your previous publication

- Publish multiple similar papers about the same study in different journals

Examples: Self-plagiarism

- Reusing text from previous papers

- Simultaneous submission

- Recycling data

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

While self-plagiarism may not be considered as serious as plagiarising someone else’s work, it’s still a form of academic dishonesty and can have the same consequences as other forms of plagiarism. Self-plagiarism:

- Shows a lack of interest in producing new work

- Can involve copyright infringement if you reuse published work

- Means you’re not making a new and original contribution to knowledge

- Undermines academic integrity, as you’re misrepresenting your research

It can still be legitimate to reuse your previous work in some contexts, but you need to acknowledge you’re doing so by citing yourself.

It can be legitimate to reuse pieces of your previous work, but you need to ensure you have explicit permission from your instructor before doing so, and you must cite yourself .

You can cite yourself just like you would cite any other source. The examples below show how you could cite your own unpublished thesis or dissertation in various styles.

Example: Citing an unpublished thesis or dissertation

- Chicago style

In addition to plagiarism software databases, many educational institutions keep databases of submitted assignments. Sometimes, they even have access to databases at other institutions. If you hand in even a portion of an old assignment a second time, the plagiarism software will flag it as self-plagiarism.

Online plagiarism checkers not affiliated with a university don’t have access to the internal databases of educational institutions, and therefore their software cannot check your document for self-plagiarism.

In addition to our Plagiarism Checker, Scribbr also offers a Self-Plagiarism Checker . This unique tool allows you to upload your own original sources and compare them with your new assignment. It will flag any unintentional self-plagiarism, in addition to other forms of plagiarism, and helps ensure that you add the correct citations before submitting your assignment.

Scribbr’s Self-Plagiarism Checker

Online plagiarism scanners do not have access to internal university databases, and therefore cannot check your document for self-plagiarism.

Using Scribbr’s Self-Plagiarism Checker , you can upload your previous work and compare it to your current document:

- Your thesis or dissertation

- Your papers or essays

- Any other published or unpublished documents

The checker will scan the texts for similarities and flag any passages where you might have self-plagiarised.

Yes, reusing your own work without citation is considered self-plagiarism . This can range from resubmitting an entire assignment to reusing passages or data from something you’ve handed in previously.

Self-plagiarism often has the same consequences as other types of plagiarism . If you want to reuse content you wrote in the past, make sure to check your university’s policy or consult your professor.

If you are reusing content or data you used in a previous assignment, make sure to cite yourself. You can cite yourself the same way you would cite any other source: simply follow the directions for the citation style you are using.

Keep in mind that reusing prior content can be considered self-plagiarism , so make sure you ask your instructor or consult your university’s handbook prior to doing so.

Most institutions have an internal database of previously submitted student assignments. Turnitin can check for self-plagiarism by comparing your paper against this database. If you’ve reused parts of an assignment you already submitted, it will flag any similarities as potential plagiarism.

Online plagiarism checkers don’t have access to your institution’s database, so they can’t detect self-plagiarism of unpublished work. If you’re worried about accidentally self-plagiarising, you can use Scribbr’s Self-Plagiarism Checker to upload your unpublished documents and check them for similarities.

The consequences of plagiarism vary depending on the type of plagiarism and the context in which it occurs. For example, submitting a whole paper by someone else will have the most severe consequences, while accidental citation errors are considered less serious.

If you’re a student, then you might fail the course, be suspended or expelled, or be obligated to attend a workshop on plagiarism. It depends on whether it’s your first offence or you’ve done it before.

As an academic or professional, plagiarising seriously damages your reputation. You might also lose your research funding or your job, and you could even face legal consequences for copyright infringement.

Most online plagiarism checkers only have access to public databases, whose software doesn’t allow you to compare two documents for plagiarism.

However, in addition to our Plagiarism Checker , Scribbr also offers an Self-Plagiarism Checker . This is an add-on tool that lets you compare your paper with unpublished or private documents. This way you can rest assured that you haven’t unintentionally plagiarised or self-plagiarised .

Compare two sources for plagiarism

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2022, July 26). What Is Self-Plagiarism? | Definition & How to Avoid It. Scribbr. Retrieved 31 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/preventing-plagiarism/self-plagiarism/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, the 5 types of plagiarism | explanations & examples, how to avoid plagiarism | tips on citing sources, consequences of mild, moderate & severe plagiarism.

Self-Plagiarism or Appropriate Textual Re-use?

- Published: 02 September 2009

- Volume 7 , pages 193–205, ( 2009 )

Cite this article

- Tracey Bretag 1 &

- Saadia Mahmud 1

4082 Accesses

62 Citations

13 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Self-plagiarism requires clear definition within an environment that places integrity at the heart of the research enterprise. This paper explores the whole notion of self-plagiarism by academics and distinguishes between appropriate and inappropriate textual re-use in academic publications, while considering research on other forms of plagiarism such as student plagiarism. Based on the practical experience of the authors in identifying academics’ self-plagiarism using both electronic detection and manual analysis, a simple model is proposed for identifying self-plagiarism by academics.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Cheating is in the Eye of the Beholder: an Evolving Understanding of Academic Misconduct

Balancing AI and academic integrity: what are the positions of academic publishers and universities?

Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice

An extensive discussion on this topic can be found on the Discussion List of the World Association of Medical Editors (WAME 2007 ).

These guidelines adhere to those provided by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE 2008 ) and also recommended by the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE 2006 ).

Turnitin is an electronic text-matching program used as a plagiarism detection tool. Electronic copies of text are submitted to the program’s ever-expanding database of electronic articles and students’ assignments. The program produces an ‘Overall Similarity Index’ with a percentage score and links to identified copied sources.

See for example, Cheah and Bretag ( 2008 ).

As our original research on academics’ self-plagiarism was based on a sample of published work by Australian authors, it was appropriate to refer to Australian Copyright Law for guidance. We recognise that Copyright Law in other countries does not necessarily provide such specific guidelines. In the United States, for example, the Copyright Act gives four non-exclusive factors to consider in a fair use analysis, including the need to take into account “the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole”. The Act does not however, provide specific guidance on how to interpret what a substantial amount might equal in percentage terms (Copyright Law of the United States 2008 ).

The authors thank an anonymous reviewer for drawing our attention to this issue.

Please refer to earlier comments regarding ongoing controversy in the United States about the use of Turnitin .

Amarnath, R. (2006). Mount St Vincent bans Turnitin.com, The Gazette , Wednesday 15 March, http://www.gazette.uwo.ca/article.cfm?section=News&articleID=632&month=3&day=15&year=2006 . Accessed 13 August 2009.

Bailey, B. J. (2002). Duplicate publication in the field of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery, 126 (3), 211–216.

Article Google Scholar

Barnard, H. & Overbeke, A. J. (1993). Duplicate publication of original manuscripts in and from the Nederlands. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd, 137 (12), 593–597.

Google Scholar

Barrett, R. & Malcolm, J. (2006). Embedding plagiarism education in the assessment process. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 2 (1), 38–45.

Blancett, S. S. Flanagan, A. & Young, R. K. (1995). Duplicate publication in the nursing literature. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 27 (1), 51–56.

Bloemenkamp, D. G. Walvoort, H. C. Hart, W. & Overbeke, A. J. (1999). Duplicate publication of articles in the Dutch Journal of Medicine in 1996. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd, 143 (43), 2150–2153.

Boisvert, R. F. & Irwin, M. J. (2006). Plagiarism on the rise. Communications of the ACM, 49 (6), 23–24.

Bretag, T. (2005). Developing internationalism in the internationalised university: A practitioner research project. University of South Australia Adelaide.

Bretag, T. (2007). The Emperor’s new clothes: yes, there is a link between English language competence and academic standards. People and Place, 15 (1), 13–21.

Bretag, T. & Carapiet, S. (2007a). A preliminary study to determine the extent of self-plagiarism in Australian academic research. Plagiary: Cross-Disciplinary Studies in Plagiarism, Fabrication and Falsification, 2 (5), 1–15.

Bretag, T., & Carapiet, S. (2007b). Self-plagiarism in Australian academic research: Identifying a gap in codes of ethical conduct. In Bretag, T. (Ed.). Refereed proceedings of the 3rd Asia-Pacific Conference on Educational Integrity: Creating a Culture of Integrity . University of South Australia, 7–8 December 2007.

Bretag, T., & Mahmud, S. (2009). A model for determining student plagiarism: electronic detection and academic judgement. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice , 6 (2), forthcoming.

British Medical Journal. (n.d.). Redundant publication. http://resources.bmj.com/bmj/authors/article-submission/publication . Accessed 2 July 2009.

Broome, M. E. (2004). Self-plagiarism: oxymoron, fair use, or scientific misconduct? Nursing Outlook, 52 (6), 273–274.

Carroll, J. (2003). Six things I did not know four years ago about dealing with plagiarism. Paper presented at the Asia-Pacific Educational Integrity Conference: Plagiarism and Other Perplexities. University of South Australia, Adelaide, 21–22 November.

Carroll, J., & Appleton, J. (2001). Plagiarism: A good practice guide. http://www.leeds.ac.uk/candit/plagiarism/brookes.pdf . Accessed 6 February 2008.

Cheah, S. W., & Bretag, T. (2008). Making technology work for academic integrity in Malaysia. Paper presented at the 3rd International Plagiarism Conference. Northumbria University, UK, 21–23 June.

Collberg, C. & Kobourov, S. (2005). Self-plagiarism in computer science. Communications of the ACM, 48 (4), 88–94.

COPE. (2006). Committee on publication ethics, Flowcharts. http://publicationethics.org/flowcharts . Accessed 16 July 2009.

Copyright Law of the United States. (2008). U.S. copyright office, http://www.copyright.gov/title17/ . Accessed 13 August 2009.

Davis, S. F. Drinan, P. F. & Bertram Gallant, T. (2009). Cheating in school: What we know and what we can do . Malden: Wiley Blackwell. forthcoming.

Devlin, M. (2003). Policy, preparation, prevention and punishment—One faculty’s holistic approach to minimising plagiarism. Paper presented at the Asia-Pacific Educational Integrity Conference: Plagiarism and Other Perplexities Conference. University of South Australia, Adelaide, 21–22 November.

Donnelly, M., Ingalis, R., Morse, T. A., Castner, J., & Stockdell-Giesler, A. M. (2006). (Mis)Trusting technology that polices integrity: a critical assessment of Turnitin.com. Inventio: Creative Thinking about Learning and Teaching , 8 (1). http://www.doit.gmu.edu/inventio/issues/Fall_2006/Donnelly_10.html . Accessed 4 February 2008.

Errami, M. Hicks, J. M. Fisher, W. Trusty, D. Wren, J. D. & Long, T. C. (2007). Deja vu—a study of duplicate citations in medline. Bioinformatics Advance Access, 24 (2), 243–249. PMID 18056062, published in Bioinformatics, 2008 Jan 15.

Errami, M. Sun, Z. Long, T. C. George, A. C. & Garner, H. R. (2008). Déjà vu: A database of highly similar citations in the scientific literature. Nucleic Acids Research, 37 , D921–D924. database issue.

Fulda, J. S. (1998). Multiple publication reconsidered. Journal of Information Ethics, 7 (2), 47–53.

Green, L. (2005). Reviewing the scourge of self-plagiarism. M/C Journal , 8 .

Griffin, G. C. (1991). Don’t plagarise—even from yourself!. Postgraduate Medicine, 89 , 15–16.

Gwilym, S. E. Swan, M. C. & Giele, H. (2004). One in 13 ‘original’ articles in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery are duplicate or fragmented publications. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 86-B (5), 743–745.

Hauptman, R. (1997). Publishing ethics. Journal of Information Ethics, 6 (1), 3.

Hiller, M. D. & Peters, T. D. (2005). The ethics of opinion in academe: questions for an ethical and administrative dilemma. Journal of Academic Ethics, 3 , 183–203.

Hinz, E. J. (1997). ‘It’s not the principle, it’s the money!’ An economic revisioning of publishing ethics. Journal of Information Ethics, 6 (1), 22–232.

Horowitz, I. L. (1997). Publishing programs and moral dilemmas. Journal of Information Ethics, 6 (1), 13–21.

Howard, R. M. (1999). Standing in the shadow of giants: Plagiarists, authors and collaborators (Vol. 2). Stamford: Perspectives on writing: Theory, Research and Practice, Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Howard, R. M. & Robillard, A. E. (eds). (2008). Pluralizing plagiarisms: Identities, contexts, pedagogies . Portsmouth: Boynton/Cook, Heineman.

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. (2008). Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedial journals: Writing and editing for biomedical publication. http://www.icmje.org/ . Accessed 2 July 2009.

Ireland, R. D. (2009). From the editors: when is a ‘new’ paper really new? Academy of Management Journal, 52 (1), 9–10.

James, R., McInnes, C., & Devlin, M. (2002). Assessing learning in Australian universities [Electronic Version]. http://www.cshe.unimelb.edu.au/assessinglearning . Accessed 18 August 2004.

Jawaid, S. A. (2005). Simultaneous submission and duplicate publication: curse and a menace which needs to be checked. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 21 (3), 1–5.

Kassirer, J. P. & Angell, M. (1995). Redundant publication: a reminder. The New England Journal of Medicine, 333 , 449–450.

Keuskamp, D. & Sliuzas, R. (2007). Plagiarism prevention or detection? The contribution of text-matching software to education about academic integrity. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 1 (1), A91–A99.

Langdon-Neuner, E. (2008). Publication more than once: duplicate publication and reuse of text. The Journal of Tehran University Heart Centre, 3 (1), 1–4.

Lowe, N. K. (2003). Publication ethics: copyright and self-plagiarism. Journal of Obstetic, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 32 , 145–146.

McCabe, D. (2005). Cheating among college and university students: A North American perspective. International Journal for Educational Integrity , 1 (1).

McKeever, L. (2006). Online plagiarism detection services—saviour or scourge? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 31 (2), 155–165.

Monash University. (2006). Citing your own work. http://calt.monash.edu.au/staff-teaching/plagiarism/acknowledgement/module2/sc/intro.html . Accessed 20 March 2007.

Murdoch University. (2007). Dishonesty in assessment. http://www.murdoch.edu.au/admin/policies/assessmentlinks.html#18 . Accessed 7 June 2007.

Purdy, J. P. (2005). Calling off the hounds: technology and the visibility of plagiarism. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture, 5 (2), 275–295.

Rees, M. & Emerson, L. (2009). The impact that Turnitin has had on text-based assessment practice. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 5 (1), 20–29.

Roig, M. (2006). Avoiding plagiarism, self-plagiarism, and other questionable writing practices: A guide to ethical writing. http://facpub.stjohns.edu/~roigm/plagiarism/Index.html . Accessed 29 January 2008.

Samuelson, P. (1994). Self-plagiarism or fair use? Communications of the ACM, 37 (8), 21–25.

Scanlon, P. (2007). Song from myself: an anatomy of self-plagiarism. Plagiary: Cross-disciplinary Studies in Plagiarism, Fabrication, and Falsification, 2 , 57–66.

Schein, M. & Paladugu, R. (2001). Redundant surgical publications: tip of the iceberg? Surgery, 129 (6), 655–661.

Twomey, T. White, H. & Sagendorf, K. (eds). (2009). Pedagogy, not policing: Positive approaches to academic integrity at the University . New York: The Graduate School Press, Syracuse University.

University of Adelaide. (2007). Academic integrity policy principles. http://www.adelaide.edu.au/policies/?230 . Accessed 7 June 2007

University of Western Australia. (2007). Academic dishonesty. http://www.arts.uwa.edu.au/studentnet/policies/dishonesty . Accessed 7 June 2007.

WAME. (2007). Sanctioning an author who has plagiarised; What is self-plagiarism? March 12, 2007–April 11, 2007. http://www.wame.org/wame-listserve-discussions/sanctioning-an-author-who-has-plagiarized-what-is-self-plagiarism . Accessed 17 July 2009.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to our colleagues in the School of Management, Associate Professor Chris Provis and Dr Howard Harris, who have contributed greatly to our thinking about appropriate textual re-use through extensive discussion on this topic throughout 2008. We thank them for their insights. Thanks also to the anonymous reviewers for providing valuable feedback.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Management, University of South Australia, GPO Box 2471, Adelaide, South Australia, 5001, Australia

Tracey Bretag & Saadia Mahmud

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tracey Bretag .

Additional information

An earlier, oral version of this paper was originally presented at the 3rd International Plagiarism Conference , Northumbria University, UK, 21–23 June 2008.

Madmud, previously known as Carapiet.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Bretag, T., Mahmud, S. Self-Plagiarism or Appropriate Textual Re-use?. J Acad Ethics 7 , 193–205 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-009-9092-1

Download citation

Received : 23 July 2009

Accepted : 25 August 2009

Published : 02 September 2009

Issue Date : September 2009

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-009-9092-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Self-plagiarism

- Textual re-use

- Electronic detection

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Plagiarism and duplicate publication

On this page, plagiarism and fabrication, due credit for others' work, nature portfolio journals' policy on duplicate publication, nature portfolio journals' editorials.

Plagiarism is unacknowledged copying or an attempt to misattribute original authorship, whether of ideas, text or results. As defined by the ORI (Office of Research Integrity), plagiarism can include, "theft or misappropriation of intellectual property and the substantial unattributed textual copying of another's work". Plagiarism can be said to have clearly occurred when large chunks of text have been cut-and-pasted without appropriate and unambiguous attribution. Such manuscripts would not be considered for publication in a Nature Portfolio journal. Aside from wholesale verbatim reuse of text, due care must be taken to ensure appropriate attribution and citation when paraphrasing and summarising the work of others. "Text recycling" or reuse of parts of text from an author's previous research publication is a form of self-plagiarism. Here too, due caution must be exercised. When reusing text, whether from the author's own publication or that of others, appropriate attribution and citation is necessary to avoid creating a misleading perception of unique contribution for the reader.

Duplicate (or redundant) publication occurs when an author reuses substantial parts of their own published work without providing the appropriate references. This can range from publishing an identical paper in multiple journals, to only adding a small amount of new data to a previously published paper.

Nature Portfolio journal editors assess all such cases on their individual merits. When plagiarism becomes evident post-publication, we may correct,retract or otherwise amend the original publication depending on the degree of plagiarism, context within the published article and its impact on the overall integrity of the published study. Nature Portfolio is part of Similarity Check , a service that uses software tools to screen submitted manuscripts for text overlap.

Top of page ⤴

Discussion of unpublished work

Manuscripts are sent out for review on the condition that any unpublished data cited within are properly credited and the appropriate permission has been attained. Where licenced data are cited, authors must include at submission a written assurance that they are complying with originators' data-licencing agreements.

Discussion of published work

When discussing the published work of others, authors must properly describe the contribution of the earlier work. Both intellectual contributions and technical developments must be acknowledged as such and appropriately cited.

Material submitted to a Nature Portfolio journal must be original and not published or concurrently submitted for publication elsewhere.

Authors submitting a contribution to a Nature Portfolio journal who have related material under consideration or in press elsewhere should upload a clearly marked copy at the time of submission, and draw the editors' attention to it in their cover letter. Authors must disclose any such information while their contributions are under consideration by a Nature Portfolio journal - for example, if they submit a related manuscript elsewhere that was not written at the time of the original Nature Portfolio journal submission.

If part of a contribution that an author wishes to submit to a Nature Portfolio journal has appeared or will appear elsewhere, the author must specify the details in the covering letter accompanying the Nature Portfolio submission. Consideration by the Nature Portfolio journal is possible if the main result, conclusion, or implications are not apparent from the other work, or if there are other factors, for example if the other work is published in a language other than English.

Nature Portfolio will consider submissions containing material that has previously formed part of a PhD or other academic thesis which has been published according to the requirements of the institution awarding the qualification.

The Nature Portfolio journals support prior publication on recognized community preprint servers for review by other scientists in the field before formal submission to a journal. More information about our policies on preprints can be found here .

Nature Portfolio journals allow publication of meeting abstracts before the full contribution is submitted. Such abstracts should be included with the Nature Portfolio journal submission and referred to in the cover letter accompanying the manuscript.

In case of any doubt, authors should seek advice from the editor handling their contribution.

If an author of a submission is re-using a figure or figures published elsewhere, or that is copyrighted, the author must provide documentation that the previous publisher or copyright holder has given permission for the figure to be re-published. The Nature Portfolio journal editors consider all material in good faith that their journals have full permission to publish every part of the submitted material, including illustrations.

- There are tools to detect non-originality in articles, but instilling ethical norms remains essential. Nature . Plagiarism pinioned, 7 July 2010.

- Scientific plagiarism—a problem as serious as fraud—has not received all the attention it deserves. Nature Medicine . The insider’s guide to plagiarism , July 2009.

- Tackling plagiarism is becoming an easier fight. Nature Physics. The truth will out , July 2009.

- Accountability of coauthors for scientific misconduct, guest authorship and deliberate or negligent citation plagiarism, highlight the need for accurate author contribution statements. Nature Photonics. Combating plagiarism , May 2009.

- Plagiarism is on the rise, thanks to the Internet. Universities and journals need to take action. Nature . Clamp down on copycats , 3 November 2005.

Fraud and replication

- When it comes to research misconduct, burying one's head in the sand and pretending it doesn't exist is the worst possible plan. Nature Chemistry. They did a bad bad thing, May 2011.

- Commit to promoting best practice in research and education in research ethics. Nature Cell Biology . Combating scientific misconduct, January 2011.

- Scientific misconduct may be more prevalent than most researchers would like to admit. The solution needs to be wide-ranging yet nuanced. Nature . Solutions, not scapegoats, 19 June 2008.

- Related Commentary by S. Titus et al. in the same issue of Nature: Repairing research integrity .

- The use of electronic laboratory notebooks should be supported by all concerned. Nature . Share your lab notes, 3 May 2007.

- Record-keeping in the lab has stayed unchanged for hundreds of years, but today's experiments are putting huge pressure on the old ways. Nature News Feature. Electronic notebooks: a new leaf, 7 July 2005.

- The true extent of plagiarism is unknown, but rising cases of suspect submissions are forcing editors to take action. Nature special report. Taking on the cheats , 19 May 2005.

Duplicate publication

- Clarifying journal policies on overlapping or concurrent submissions and embargo. Nature Neuroscience . Navigating issues of related submission and embargo, July 2014.

- Duplicate publication dilutes science. Nature Photonics. Quality over quantity , September 2011.

- On fragmenting one coherent body of research into as many publications as possible. Nature Materials . The cost of salami slicing , January 2005.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- my research

- contributions and comments

recycling your thesis text – is it self plagiarism?

The term self-plagiarism is usually associated with re-using your own work, recycling slabs of material already published, cutting and pasting from one text to another, producing something which duplicates something that has already appeared elsewhere.

Self-plagiarism is not the same as stealing someone else’s work and passing it off as your own, that’s plagiarism. Nor is it the same as violating copyright – using other people’s text without permission, or even re-using your own work when the copyright has been signed over to someone else. We all know these practices are wrong, so if self plagiarism is like these, it must be too.

The idea of self-plagiarism is scary. We all know that plagiarists get punished if they are found out. They can be sacked, their work pulped or retracted. And universities and publishers are increasingly on the lookout for plagiarism, using automatic software to detect it. So the notion of plagiarising your own work carries with it the spectre of the surveillance and punishment.

But recycling your own work is more often discussed as an ethical question not a legal one. A question of deliberate deceit perhaps. Reuse of your own writing can be regarded as a form of ‘cheating’ – you’ve written something which is published and then you don’t do the hard work of writing something new, you take the easy way out by dragging and dropping the text you made earlier. You aren’t producing something new or original, this version of recycling goes, and to make things worse, you’re tricking the reader into thinking that the work is new. You’re double-dipping – writing without integrity. Some people even see such recycling of text as a form of academic fraud.

But the reuse situation isn’t that straightforward. There may well be circumstances where recycling doesn’t seem unethical, but sensible. Where it’s not simply a question of saving the effort of producing a new version of material.

Think of descriptions of research projects which appear in methods sections of journal articles and in books. It’s not just that there are only so many ways that you can present the same information about the one research project – it’s more that you actually want the way in which you report your project, and its design and processes, to be consistent across publications. Similarly, if you have developed a novel interpretation or heuristic or model which you then use as the basis of future work, you also want there to be a through line from the initial work to the latter. While some of this origin tracing can and should be done via citation, there may also be some common wording that you want to use, something longer than a quotation, perhaps something more like a big chunk of a chapter. Re-use is often key to iterative knowledge-building.

Duplicating thesis text, repurposing it for publication often bothers PhDers. Sometimes a lot. That’s understandable. The PhD is most often now a digital text and is a publication in its own right, but the PhD is also the basis for papers and perhaps a book. Let me explain the most common examples of re-use.

Publishing before the thesis and then reusing it in the thesis text. Publishing prior to the PhD being finalised is quite common and is often done as disciplinary convention, as reputational move and/or as a means of developing a line of argument for the thesis itself. This isn’t a huge issue.

In the PhD by publication, the papers are by definition part of the thesis text. They often appear in their final published form, which may be copyrighted to a journal, not the final author version. I am not aware than any publisher has taken issue with the practice of using the final copyrighted version. But they could I guess. In which case you’d use the final author version as is often now done in university repositories.

By contrast, in the monograph PhD, the text of a previously published paper is usually incorporated into the text and an acknowledgement made, either at the beginning of the text or when the text appears, that some of the material has been published elsewhere. There are however some disciplinary differences here about how acceptable this practice is, and it is always worth checking out rules and conventions with your supervisor and/or your university librarian.

Publishing after the thesis is completed and publicly available. The situation is a little different when the thesis becomes the basis for post-graduation publications. Here the question is how much you can cut and paste from the digital thesis into another, usually shorter, form. There is an a priori question of course about how much you should recycle given that the thesis is written for a different audience and a particular purpose. Most books of the PhD are actually very substantially rewritten. Put that issue aside for a moment. The question is how much should, and can you, re-use of the thesis? What are the risks and wrongs?

Theres a lot of rumour about cutting and pasting from your big book. Everyone seems to have heard of the publisher who refuses a book proposal on the grounds that it will be substantially the same as an e-thesis. However, there seems little actual evidence of this happening. A study by UCL librarians Brown and Sadler found no cases of this happening in the UK, although fears and worries about the possibility were rife particularly among PhDers and their supervisors. But…

Because no one is quite sure about recycling from the thesis you may get various forms of advice. If you want to re-use substantial thesis extracts for a book you may be advised to restrict access to your thesis for a period of time so that the new publication become the major source. Embargo to avoid problems. Or you may be advised to discuss the re-use of thesis material with the publisher if you are writing the-book-of-the-thesis. Or you may be encouraged to learn about open access so that you can have a conversation with an editor about the benefits of having both the thesis and a new book version of the work available at the same time.

Maybe you’re not writing a book but journal articles and book chapters. Reuse here is different. You aren’t very likely to be carrying over thesis literature work – too long. Your methods chapter will be too big. So we are probably talking about bits of what appears in your thesis as results and discussion. For example, there may be tables, graphs or diagrammes. There may be descriptions of participants or places. Most likely there are chunks of worked analyses that you want to cut and paste. Usually it seems to be enough to say in the text of the paper or chapter that the material is based on doctoral work, providing a citation to the thesis online. But there’s always the possibility of something more sinister happening. Again loads of urban myths here.

So is recycling a real problem? Are we just getting worked up over not very much? The first problem seems to be that we don’t even agree on what self plagiarism is, let alone whether it’s a serious issue or not.

My own view, which won’t be everyone’s, is that provided you recycle thesis material in ways that are acknowledged, then some re-use in journal papers and book chapters is not only acceptable but also sensible. After all, you slogged over these chunks for quite some time and worked hard on making them as good as you could. You may find of course when you revisit them that you do still want to tinker with the wording, or add a bit more/cut some things out. For me, the key thing is to own up to this re-use and not to try to hide it. As long as you make sure to check with the relevant editors and journal rules then transposing some text from a thesis or research report to book or journal seems to me to be quite in keeping with the spirit of scholarly publication ethics.

But, as always, do check this out. If in doubt who to ask, start with your university library.

And help may be at hand. Do look at this research project on text recycling which offers some very helpful guidelines for how to steer through murky re-use territory. One of the things the project suggests is doing away with the ambiguous term self plagiarism – Yes!!!- and adopting a more specific set of terms – see the note at the end of this post.

Recognising the reality of text re-use, the project’s guidelines for researchers say:

- Authors should recycle text where consistency of language is needed for accurate communication. This consistency can be especially important when describing methods and instrumentation that are common across studies. If the amount of recycled material is substantial, authors should determine whether permissions are needed (see Recycling Text Legally) and whether it is acceptable for the outlet (see Recycling Text Transparently).

- Authors may recycle text so long as the recycled material is accurate and appropriate for the new work and does not infringe copyright or violate publisher policies.

- Authors should be careful not to recycle text in ways that might mislead readers or editors about the novelty of the new work.

Sounds good to me. Can we all decide this is the way to go?

The Text Recycling Project is based at Duke University and is directed by Cary Moskowitz. It is primarily concerned with practices in STEM but is of much wider interest and application. The project has produced a number of scholarly papers on reuse .

A recent and open access paper written by Moskowitz proposes a new taxonomy for re-use – developmental recycling, generative recycling, adaptive publication and duplicate publication. The paper is open access and well worth reading. I for one will be adopting his terms.

Image by Sigmund on Unsplash

Share this:

About pat thomson

4 responses to recycling your thesis text – is it self plagiarism.

Anonymous My supervisor hired me to write a paper with him and his wife and another academic and advised me to copy paragraphs from my thesis. When I questioned if I needed to cite my work he advised that it was standard practice and “as co-author it was my writing therefore it should not make a difference”. They’ve since dropped my name but the published paper still contains the paragraphs (and then some). Is this plagiarism?

I reckon it is, but I’m no authority on the finer legal points. I would contact the journal editor in chief of the journal, if that’s where it’s published,and tell them what has happened. You might also try your university library and or current employer or union for advice and support. If they agree it’s misuse of your work, they should help you to take action.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Search for:

Follow Blog via Email

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address:

patter on facebook

Recent Posts

- do you read – or talk – your conference paper?

- your conference paper – already published or work in progress?

- a musing on email signatures

- creativity and giving up on knowing it all

- white ants and research education

- Anticipation

- research as creative practice – possibility thinking

- research as – is – creative practice

- On MAL-attribution

- a brief word on academic mobility

- Key word – claim

- key words – contribution

SEE MY CURATED POSTS ON WAKELET

Top posts & pages.

- do you read - or talk - your conference paper?

- aims and objectives - what's the difference?

- five ways to structure a literature review

- writing a bio-note

- I can't find anything written on my topic... really?

- 20 reading journal prompts

- tiny texts - small is powerful

- headings and subheadings – it helps to be specific

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.com

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Sep 1, 2013 at 17:48. 1. Correction: you are mostly right about plagiarism issues, but not about copyright. Self-plagiarism is a real thing (and misconduct in some cases)—but reusing your papers in your thesis (with citation!) is completely fine.

Self-plagiarism means reusing work that you have already published or submitted for a class. It can involve: Self-plagiarism misleads your readers by presenting previous work as completely new and original. If you want to include any text, ideas, or data that you already submitted in a previous assignment, be sure to inform your readers by ...

Self-plagiarism—sometimes known as " duplicate plagiarism "—is a term for when a writer recycles work for a different assignment or publication and represents it as new. For students, this may involve recycling an essay or large portions of text written for a prior course and resubmitting it to fulfill a different assignment in a ...

Plagiarism is defined as a form of misconduct which involves copying or stealing others' ideas, methods, findings, or words and passing off as one's own original work without acknowledging the original source (Office of Research Integrity, Citation 2000).However, reusing one's own previously published work in subsequent publications without acknowledging this may be considered as self ...

As Callahan (2018, p. 306) states, "whether a real issue of ethical concern or a moral panic, self-plagiarism has captured the attention of authors, editors, publishers, and plagiarism-detection software companies," and has led to fierce debates on the judgment of fair reuse of one's own work. This editorial will revisit these debates and explain the views and expectations of the Project ...

Self-plagiarism is a contentious issue in higher education, research and scholarly publishing contexts. The practice is problematic because it disrupts scientific publishing by over-emphasizing results, increasing journal publication costs, and artificially inflating journal impact, among other consequences. We hypothesized that there was a dearth of empirical studies on the topic of self ...

1. The fundamental role of research papers. The broadest reason to avoid self-plagiarism deals with the integrity of the research record, and of scientific discovery as a whole. It is widely understood that each published manuscript will include new knowledge and results that advance our understanding of the world.

Forms of self-plagiarism. To clarify the ethical complexities of self-plagiarism and explain the ways to avoid it, scientists have been trying to define self-plagiarism and to describe its possible forms (2,3).Miguel Roig published a paper in Biochemia Medica with an emphasis on self-plagiarism; he distinguished four types of self-plagiarism: duplicate (redundant) publication, augmented ...

The paper discusses self-plagiarism and associated practices in scholarly publishing. It approaches at some length the conceptual issues raised by the notion of self-plagiarism. It distinguishes among and then examines the main families of arguments against self-plagiarism, as well as the question of possibly legitimate reasons to engage in this practice. It concludes that some of the animus ...

Scholarly misconduct causes significant impact on the academic community. To the extremes, results of scholarly misconduct could endanger public welfare as well as national security. Although self-plagiarism has drawn considerable amount of attention, it is still a controversial issue among different aspect of academic ethic related discussions. The main purpose of this study is to identify ...

Many journals, conference proceedings, and other publishers allow you to reuse your self-authored papers in a thesis or dissertation, as long as you have credited the original publisher. Though requirements vary by publisher, this credit can often be accomplished through simple citations and disclaimers.

Among the various forms of academic misconduct, text recycling or 'self-plagiarism' holds a particularly contentious position. Scientists and commentators agree on the undermining effects of infringements of core conventions in research, such as falsification, fabrication and plagiarism (FFP), and a series of questionable research practices ...

Avoiding self-plagiarism. Academic publication takes many different forms. Researchers will often write up their findings for more than one publication, for example in a thesis and a journal article, or a blog post and book chapter. This is not necessarily a problem, but researchers need to consider their choices carefully.

Self‐plagiarism is a type of plagiarism, in which the writer republishes a work in its entirety or reuses portions of a previously written text in a new manuscript without proper citation (American Psychological Association, 2010). The controversial term "self‐plagiarism" often leads to the assumption that data which has been published ...

The guidelines usefully recast these issues in terms other than self-plagiarism, says Lisa Rasmussen, a research ethicist at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte. "It's causing a problem to focus too much on self-plagiarism," she says. ... Moskovitz says: In a survey of editors at top journals across disciplines, he and his collaborators ...

Hi, I am thinking about revising my doctoral dissertation into a journal article to have a broader readership. But I am concerned about any potential problems of self-plagiarism.My doctoral dissertation was electronically published by the university in 2014. In that case, can I still submit an article the content of which is based on most parts of my doctoral dissertation?

Remember to follow these guidelines to ensure the appropriate use of published work in your doctoral thesis while avoiding self-plagiarism. What is Self-Plagiarism. The UCL Academic Manual describes self-plagiarism as: "The reproduction or resubmission of a student's own work which has been submitted for assessment at UCL or any other ...

Revised on 26 July 2022. Plagiarism often involves using someone else's words or ideas without proper citation, but you can also plagiarise yourself. Self-plagiarism means reusing work that you have already published or submitted for a class. It can involve: Resubmitting an entire paper. Copying or paraphrasing passages from your previous work.

Self-plagiarism requires clear definition within an environment that places integrity at the heart of the research enterprise. This paper explores the whole notion of self-plagiarism by academics and distinguishes between appropriate and inappropriate textual re-use in academic publications, while considering research on other forms of plagiarism such as student plagiarism. Based on the ...

Nature Portfolio journals' editorials; Plagiarism and fabrication ... publication is a form of self-plagiarism. ... part of a PhD or other academic thesis which has been published according to the ...

Posted onSeptember 13, 2021by pat thomson. The term self-plagiarism is usually associated with re-using your own work, recycling slabs of material already published, cutting and pasting from one text to another, producing something which duplicates something that has already appeared elsewhere. Self-plagiarism is not the same as stealing ...

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society was established in March 1665 and the first fully peer-reviewed journal was Medical Essays and Observations (1733). Over a thousand periodicals were founded during the eighteenth century but many ran for only a few issues (see Geilas & Fyfe, Citation 2020 , for the editing of scientific journals ...