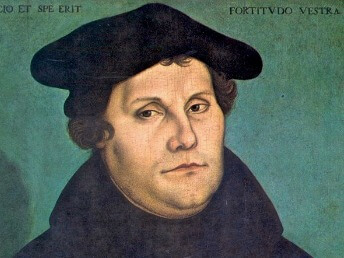

by Dr. Martin Luther, 1517

Disputation of Doctor Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences by Dr. Martin Luther (1517)

Out of love for the truth and the desire to bring it to light, the following propositions will be discussed at Wittenberg, under the presidency of the Reverend Father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and of Sacred Theology, and Lecturer in Ordinary on the same at that place. Wherefore he requests that those who are unable to be present and debate orally with us, may do so by letter. In the Name our Lord Jesus Christ. Amen. 1. Our Lord and Master Jesus Christ, when He said Poenitentiam agite, willed that the whole life of believers should be repentance. 2. This word cannot be understood to mean sacramental penance, i.e., confession and satisfaction, which is administered by the priests. 3. Yet it means not inward repentance only; nay, there is no inward repentance which does not outwardly work divers mortifications of the flesh. 4. The penalty [of sin], therefore, continues so long as hatred of self continues; for this is the true inward repentance, and continues until our entrance into the kingdom of heaven. 5. The pope does not intend to remit, and cannot remit any penalties other than those which he has imposed either by his own authority or by that of the Canons. 6. The pope cannot remit any guilt, except by declaring that it has been remitted by God and by assenting to God's remission; though, to be sure, he may grant remission in cases reserved to his judgment. If his right to grant remission in such cases were despised, the guilt would remain entirely unforgiven. 7. God remits guilt to no one whom He does not, at the same time, humble in all things and bring into subjection to His vicar, the priest. 8. The penitential canons are imposed only on the living, and, according to them, nothing should be imposed on the dying. 9. Therefore the Holy Spirit in the pope is kind to us, because in his decrees he always makes exception of the article of death and of necessity. 10. Ignorant and wicked are the doings of those priests who, in the case of the dying, reserve canonical penances for purgatory. 11. This changing of the canonical penalty to the penalty of purgatory is quite evidently one of the tares that were sown while the bishops slept. 12. In former times the canonical penalties were imposed not after, but before absolution, as tests of true contrition. 13. The dying are freed by death from all penalties; they are already dead to canonical rules, and have a right to be released from them. 14. The imperfect health [of soul], that is to say, the imperfect love, of the dying brings with it, of necessity, great fear; and the smaller the love, the greater is the fear. 15. This fear and horror is sufficient of itself alone (to say nothing of other things) to constitute the penalty of purgatory, since it is very near to the horror of despair. 16. Hell, purgatory, and heaven seem to differ as do despair, almost-despair, and the assurance of safety. 17. With souls in purgatory it seems necessary that horror should grow less and love increase. 18. It seems unproved, either by reason or Scripture, that they are outside the state of merit, that is to say, of increasing love. 19. Again, it seems unproved that they, or at least that all of them, are certain or assured of their own blessedness, though we may be quite certain of it. 20. Therefore by "full remission of all penalties" the pope means not actually "of all," but only of those imposed by himself. 21. Therefore those preachers of indulgences are in error, who say that by the pope's indulgences a man is freed from every penalty, and saved; 22. Whereas he remits to souls in purgatory no penalty which, according to the canons, they would have had to pay in this life. 23. If it is at all possible to grant to any one the remission of all penalties whatsoever, it is certain that this remission can be granted only to the most perfect, that is, to the very fewest. 24. It must needs be, therefore, that the greater part of the people are deceived by that indiscriminate and highsounding promise of release from penalty. 25. The power which the pope has, in a general way, over purgatory, is just like the power which any bishop or curate has, in a special way, within his own diocese or parish. 26. The pope does well when he grants remission to souls [in purgatory], not by the power of the keys (which he does not possess), but by way of intercession. 27. They preach man who say that so soon as the penny jingles into the money-box, the soul flies out [of purgatory]. 28. It is certain that when the penny jingles into the money-box, gain and avarice can be increased, but the result of the intercession of the Church is in the power of God alone. 29. Who knows whether all the souls in purgatory wish to be bought out of it, as in the legend of Sts. Severinus and Paschal. 30. No one is sure that his own contrition is sincere; much less that he has attained full remission. 31. Rare as is the man that is truly penitent, so rare is also the man who truly buys indulgences, i.e., such men are most rare. 32. They will be condemned eternally, together with their teachers, who believe themselves sure of their salvation because they have letters of pardon. 33. Men must be on their guard against those who say that the pope's pardons are that inestimable gift of God by which man is reconciled to Him; 34. For these "graces of pardon" concern only the penalties of sacramental satisfaction, and these are appointed by man. 35. They preach no Christian doctrine who teach that contrition is not necessary in those who intend to buy souls out of purgatory or to buy confessionalia. 36. Every truly repentant Christian has a right to full remission of penalty and guilt, even without letters of pardon. 37. Every true Christian, whether living or dead, has part in all the blessings of Christ and the Church; and this is granted him by God, even without letters of pardon. 38. Nevertheless, the remission and participation [in the blessings of the Church] which are granted by the pope are in no way to be despised, for they are, as I have said, the declaration of divine remission. 39. It is most difficult, even for the very keenest theologians, at one and the same time to commend to the people the abundance of pardons and [the need of] true contrition. 40. True contrition seeks and loves penalties, but liberal pardons only relax penalties and cause them to be hated, or at least, furnish an occasion [for hating them]. 41. Apostolic pardons are to be preached with caution, lest the people may falsely think them preferable to other good works of love. 42. Christians are to be taught that the pope does not intend the buying of pardons to be compared in any way to works of mercy. 43. Christians are to be taught that he who gives to the poor or lends to the needy does a better work than buying pardons; 44. Because love grows by works of love, and man becomes better; but by pardons man does not grow better, only more free from penalty. 45. 45. Christians are to be taught that he who sees a man in need, and passes him by, and gives [his money] for pardons, purchases not the indulgences of the pope, but the indignation of God. 46. Christians are to be taught that unless they have more than they need, they are bound to keep back what is necessary for their own families, and by no means to squander it on pardons. 47. Christians are to be taught that the buying of pardons is a matter of free will, and not of commandment. 48. Christians are to be taught that the pope, in granting pardons, needs, and therefore desires, their devout prayer for him more than the money they bring. 49. Christians are to be taught that the pope's pardons are useful, if they do not put their trust in them; but altogether harmful, if through them they lose their fear of God. 50. Christians are to be taught that if the pope knew the exactions of the pardon-preachers, he would rather that St. Peter's church should go to ashes, than that it should be built up with the skin, flesh and bones of his sheep. 51. Christians are to be taught that it would be the pope's wish, as it is his duty, to give of his own money to very many of those from whom certain hawkers of pardons cajole money, even though the church of St. Peter might have to be sold. 52. The assurance of salvation by letters of pardon is vain, even though the commissary, nay, even though the pope himself, were to stake his soul upon it. 53. They are enemies of Christ and of the pope, who bid the Word of God be altogether silent in some Churches, in order that pardons may be preached in others. 54. Injury is done the Word of God when, in the same sermon, an equal or a longer time is spent on pardons than on this Word. 55. It must be the intention of the pope that if pardons, which are a very small thing, are celebrated with one bell, with single processions and ceremonies, then the Gospel, which is the very greatest thing, should be preached with a hundred bells, a hundred processions, a hundred ceremonies. 56. The "treasures of the Church," out of which the pope. grants indulgences, are not sufficiently named or known among the people of Christ. 57. That they are not temporal treasures is certainly evident, for many of the vendors do not pour out such treasures so easily, but only gather them. 58. Nor are they the merits of Christ and the Saints, for even without the pope, these always work grace for the inner man, and the cross, death, and hell for the outward man. 59. St. Lawrence said that the treasures of the Church were the Church's poor, but he spoke according to the usage of the word in his own time. 60. Without rashness we say that the keys of the Church, given by Christ's merit, are that treasure; 61. For it is clear that for the remission of penalties and of reserved cases, the power of the pope is of itself sufficient. 62. The true treasure of the Church is the Most Holy Gospel of the glory and the grace of God. 63. But this treasure is naturally most odious, for it makes the first to be last. 64. On the other hand, the treasure of indulgences is naturally most acceptable, for it makes the last to be first. 65. Therefore the treasures of the Gospel are nets with which they formerly were wont to fish for men of riches. 66. The treasures of the indulgences are nets with which they now fish for the riches of men. 67. The indulgences which the preachers cry as the "greatest graces" are known to be truly such, in so far as they promote gain. 68. Yet they are in truth the very smallest graces compared with the grace of God and the piety of the Cross. 69. Bishops and curates are bound to admit the commissaries of apostolic pardons, with all reverence. 70. But still more are they bound to strain all their eyes and attend with all their ears, lest these men preach their own dreams instead of the commission of the pope. 71. He who speaks against the truth of apostolic pardons, let him be anathema and accursed! 72. But he who guards against the lust and license of the pardon-preachers, let him be blessed! 73. The pope justly thunders against those who, by any art, contrive the injury of the traffic in pardons. 74. But much more does he intend to thunder against those who use the pretext of pardons to contrive the injury of holy love and truth. 75. To think the papal pardons so great that they could absolve a man even if he had committed an impossible sin and violated the Mother of God -- this is madness. 76. We say, on the contrary, that the papal pardons are not able to remove the very least of venial sins, so far as its guilt is concerned. 77. It is said that even St. Peter, if he were now Pope, could not bestow greater graces; this is blasphemy against St. Peter and against the pope. 78. We say, on the contrary, that even the present pope, and any pope at all, has greater graces at his disposal; to wit, the Gospel, powers, gifts of healing, etc., as it is written in I. Corinthians xii. 79. To say that the cross, emblazoned with the papal arms, which is set up [by the preachers of indulgences], is of equal worth with the Cross of Christ, is blasphemy. 80. The bishops, curates and theologians who allow such talk to be spread among the people, will have an account to render. 81. This unbridled preaching of pardons makes it no easy matter, even for learned men, to rescue the reverence due to the pope from slander, or even from the shrewd questionings of the laity. 82. To wit: -- "Why does not the pope empty purgatory, for the sake of holy love and of the dire need of the souls that are there, if he redeems an infinite number of souls for the sake of miserable money with which to build a Church? The former reasons would be most just; the latter is most trivial." 83. Again: -- "Why are mortuary and anniversary masses for the dead continued, and why does he not return or permit the withdrawal of the endowments founded on their behalf, since it is wrong to pray for the redeemed?" 84. Again: -- "What is this new piety of God and the pope, that for money they allow a man who is impious and their enemy to buy out of purgatory the pious soul of a friend of God, and do not rather, because of that pious and beloved soul's own need, free it for pure love's sake?" 85. Again: -- "Why are the penitential canons long since in actual fact and through disuse abrogated and dead, now satisfied by the granting of indulgences, as though they were still alive and in force?" 86. Again: -- "Why does not the pope, whose wealth is to-day greater than the riches of the richest, build just this one church of St. Peter with his own money, rather than with the money of poor believers?" 87. Again: -- "What is it that the pope remits, and what participation does he grant to those who, by perfect contrition, have a right to full remission and participation?" 88. Again: -- "What greater blessing could come to the Church than if the pope were to do a hundred times a day what he now does once, and bestow on every believer these remissions and participations?" 89. "Since the pope, by his pardons, seeks the salvation of souls rather than money, why does he suspend the indulgences and pardons granted heretofore, since these have equal efficacy?" 90. To repress these arguments and scruples of the laity by force alone, and not to resolve them by giving reasons, is to expose the Church and the pope to the ridicule of their enemies, and to make Christians unhappy. 91. If, therefore, pardons were preached according to the spirit and mind of the pope, all these doubts would be readily resolved; nay, they would not exist. 92. Away, then, with all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, "Peace, peace," and there is no peace! 93. Blessed be all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, "Cross, cross," and there is no cross! 94. Christians are to be exhorted that they be diligent in following Christ, their Head, through penalties, deaths, and hell; 95. And thus be confident of entering into heaven rather through many tribulations, than through the assurance of peace.

This text was converted to ASCII text for Project Wittenberg by Allen Mulvey, and is in the public domain. You may freely distribute, copy or print this text. Please direct any comments or suggestions to:

Rev. Robert E. Smith Walther Library Concordia Theological Seminary.

E-mail: [email protected] Surface Mail: 6600 N. Clinton St., Ft. Wayne, IN 46825 USA Phone: (260) 452-3149 - Fax: (260) 452-2126

Stanford Humanities Today

Arcade: a digital salon.

Scott Ferguson and Brendan Cook

Lo, Christ is never strong in us till we be weak. As our strength abateth, so groweth the strength of Christ in us; when we are clean emptied of our own strength, then are we full of Christ’s strength. And look, how much of our own strength remaineth in us, so much lacketh there of the strength of Christ. – William Tyndale, Obedience of a Christian Man Why does not the pope, whose wealth is today greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build this one basilica of St. Peter with his own money rather than with the money of poor believers? – Martin Luther, Thesis 86

Issuing a direct challenge to seemingly unshakable economic truths, the contemporary chartalist school of political economy known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) has argued that money is a boundless public utility and that at bottom employment is a creature of the state. As MMT economist Stephanie Kelton explains in a recent piece for The Los Angeles Times , this means that a currency-issuing polity can always afford to employ persons in service of social and environmental needs. Such targeted state spending should not precipitate harmful inflation, Kelton maintains, provided that government mobilizes available material resources and collective knowhow to realize its politically determined aims.

Chartalists like Kelton offer the left a genuine alterative to neoliberal privation and a novel foundation for politics. Still, possibilities for social and environmental justice tomorrow will also hinge on the struggle over defining money’s past, and chartalist historiography remains in its infancy. Pioneering efforts by Alfred Mitchell Innes , Michael Hudson , and Christine Desan notwithstanding, contemporary chartalism lacks a rich archive of social artefacts and demands more robust and interdisciplinary methods. This is where the complex historiographic methods practiced in the humanities can make a tremendous contribution to the chartalist project. Indeed, if the future of money is to be forged in the fires of its still-largely obscure history, the humanities can play a crucial role in mining money’s social past for its repressed social potentials.

Take, for example, the recent account of the Protestant Reformation by Davide Cantoni, Jeremiah Dittmar, and Noam Yuchtman. Published by VoxEU and later featured by Naked Capitalism , the essay contends that the tremendous economic transformation that accompanied the Reformation was precipitated by the breakup of a previously monopolized “market for salvation” and resulted in an “immediate and large secularization” of investment and production more generally.

It is clear that the authors’ entire thesis relies upon unquestioned neoclassical assumptions about the virtues of competitive markets, pricing on the margin, rational expectations, and econometric evidence; this alone should raise the eyebrow of any critical chartalist. Yet when viewed from an interdisciplinary historical perspective, their neoclassical fable of the Reformation melts into thin air.

The authors’ foundational error is to treat the Universal Church not as a governmental institution, as it would be in a chartalist reading, but as a sort of independent contractor providing religious services to interested individuals. They start by affirming earlier scholarship, which casts the various organs of the Church as “producers of salvation” for the lay Christians who served as the product’s “consumers.”

Having begun here, they introduce a second “product.” In addition to manufacturing salvation, the Church is also a supplier of legitimacy for so-called “secular rulers,” by which the authors primarily mean the monarchs of the emergent nation-states. Before the age of reform, the papacy held a spiritual monopoly, they explain, providing the crowned heads of Christendom with salvation, and especially legitimacy, for a very steep price. With the introduction of the new reformed confessions, however, the monopoly was broken, and sovereigns of every faith found they could now purchase the endorsement of religious leaders at a bargain. This meant that resources once diverted towards “religious” ends could be put to other, more “secular” uses.

Although it is hard to deny that the weakness of the papacy after 1517 allowed even Catholic rulers to enlarge the scope of their power, the rest of the account presented by Cantoni, Dittmar, and Yuchtman is far less credible. Their least plausible gesture is to stress a one-dimensional narrative of secularization at the expense of a more nuanced understanding of the evolving role of religion in European society.

The development of secular civil society in the West is obviously much debated. Was it a product of the later age Enlightenment? Or a gradual process unfolding over the course of many centuries? Instead of choosing either of these more plausible theories, the authors try to make the Reformation a dramatic turning point. Rather than a single step along a very long road, it is the site of a sudden realignment of social resources and political power away from the realm of the sacred, a moment when “human capital and fixed investment shifted sharply from religious to secular purposes.” The authors speak of a decline in the study of theology, “which paid off specifically in the religious sector,” of “increased [labor] demand in the secular sector,” and a reorientation of construction projects “towards the interests of secular lords — palaces and administrative buildings.”

This simplistic division is a mistake, and not because the transfer of social resources from the institutional church to monarchies and republics was imaginary; that it took place is beyond controversy. Instead we need to question the framing of the shift in terms of an opposition of “religious” and “secular.” Were the so-called “secular rulers” who benefited from the weakening of papal authority really less religious in their orientation?

Take the example of England! While Henry VIII dissolved most, although not all of the monasteries, it never occurred to him to abolish the English Church. Instead he placed himself at its head, appointing bishops, overseeing the indoctrination of his subjects, and setting the patterns of their worship; he did not abolish the papacy so much as take the pope’s place. He also laid claim upon the pope’s authority to punish heresy within his realm, a function enthusiastically continued by his children and successors, Edward, Mary, and Elizabeth. Can we really describe the empowerment of these rulers as a decline of the sacred at the expense of the secular?

And England is hardly an exception. The Catholic monarchs of Iberia inserted themselves even more dramatically into the spiritual lives of their subjects, and it was left to the “secular” town government of Geneva to establish perhaps the most systematically theocratic regime in the history of Western Europe.

The same may be said of the authors’ assertions regarding “secular” labor demand and “secular” construction projects. They speak of the “hiring of lawyers rather than theologians,” but a law degree had been a reliable path to success in the Roman curia since at least the thirteenth century; it would hardly be an exaggeration to say that the popes of the later middle ages employed more tax attorneys than doctors of theology. The authors also classify “palaces” as “secular” building projects, in contrast to churches and shrines, but this would be news to the architects and builders of the great ecclesiastical palaces of fifteenth-century Rome.

Moreover, by including “administrative buildings” on the “secular” side of the balance, the authors return to their original error. To treat courthouses and chanceries as more appropriate to a king or a prince than a cardinal or a pope means more than simply ignoring how many were built or refurbished to serve the needs of the massive papal bureaucracy. Ultimately, it is to forget that the pre-Reformation church was not a private provider of this or that service, but a source of political authority in its own right. It was not simply an impediment to the aspirations of would-be theocrats in London or Madrid, but their rival: a sophisticated and self-conscious governing project directed towards the collective life of Latin Christianity.

It is because Cantoni, Dittmar, and Yuchtman fail to recognize the political nature of the papacy that their simplified account of a rapid lurch towards secularization is necessary in the first place. Since they cannot acknowledge the real similarities between royal and papal regimes, they must resort to a forced opposition of kings and popes, royal lawyers and church lawyers, princes’ palaces and bishops’ palaces. They mistake a revolution in political and monetary governance for a story of markets, consumerism, and individual bargaining. As a consequence, they set forth a simplified and exaggerated story of secularization.

Their thinking allows no room for a different story, one not of supply and demand, provider and customer, but of contesting government enterprises, the decline of one, the papacy, and the rise of others in its place. They have already decided that the history of humanity is a story of producing and consuming, and buying and bargaining, and so this is what they find. And because this understanding is derived from a later era, namely the Enlightenment, they must impose the Enlightenment’s opposition of religion and secularism upon their account of the profoundly religious society of Reformation Europe. What is worse, by suppressing the Reformation’s true political contours, the authors misrepresent the period’s complex history and its potential meaning for a future politics.

The great irony here is that it was the same age of Reformation which the authors so gravely misunderstand that cleared the way for the reductive vision of politics and economics upon which they rely. The later middle ages had nourished a number of diverse intellectual traditions, many of which anticipated chartalism’s sense of the potential of the state to answer the needs of the people.

In the era of Aquinas, Dante, and Accursius, a capacious and expansive understanding of law, government, sovereignty, and, above all, of currency, still seemed possible. It did not appear ridiculous to declare, as Dante does in De Monarchia, that the Empire cannot become insolvent because all things ultimately belong to the emperor.

In contrast, the greatest minds of the Reformation, Erasmus, Luther, Melanchthon, Calvin, helped complete the work of stifling and foreclosing these traditions, work begun with the parallel development of Humanism and Nominalism in the fourteenth century. In their ostensibly theological writings on God’s power and Christ’s redeeming grace, the reformers developed a style of contracted, zero-sum thinking which, extended to political economy, makes the limitation of public spending seem natural and inevitable. Such thinking is on full display in the two epigraphs above.

The claim of the English reformer William Tyndale that Christ is only strong when the individual is weak is a metaphysical foreshadowing of the modern Liberal doctrine that the state’s power to spend must come at the expense of the private wealth of the citizen. The underlying logic of such a statement points toward a notion of “private money” being “taken” by a grasping state apparatus which is already adumbrated in Luther’s famous Theses.

Laying the groundwork for the later emergence of Liberal political economy and the modern system of nation-states, the reformers actively purged late-medieval conceptions of the monetary instrument as a public utility from the collective imagination. Instead, they construed money as a private, finite and decentered instrument, and sovereign governments as constrained by taxation revenues and borrowing. In historicizing the Reformation through a narrative of market maneuvering, Cantoni, Dittmar, and Yuchtman mirror the Reformation period’s self-serving repression of chartalism and bar chartalism’s political potential from expanding the contemporary political imagination.

History is not a transparent window onto bygone times; it is an opaque antechamber to still-undetermined futures. For this reason, chartalists need to tell fresh and compelling stories about money’s complex political and social history. In the meantime, we must insist that if money is irreducible to market exchange, so too is its past. Otherwise, the fate of collective life will remain imprisoned in a dismal story that the Reformation scripted long ago.

View the discussion thread.

What are My Colloquies?

My Colloquies are shareables: Curate personal collections of blog posts, book chapters, videos, and journal articles and share them with colleagues, students, and friends.

My Colloquies are open-ended: Develop a Colloquy into a course reader, use a Colloquy as a research guide, or invite participants to join you in a conversation around a Colloquy topic.

My Colloquies are evolving: Once you have created a Colloquy, you can continue adding to it as you browse Arcade.

Discovering Humanities Research at Stanford

Stanford Humanities Center

Advancing Research in the Humanities

Humanities Research for a Digital Future

The Humanities in the World

- Interventions

- About the Journal

- Policy and Submissions

- Editorial Board

- Editorial Policy

- Submission Guidelines

- Executive Team

- Friends of Arcade

Explore the Faith

Faith seeking Understanding

The 95 Theses by Dr. Martin Luther

The Ninety-Five Theses were written by Martin Luther in 1517 and are widely regarded as the initial catalyst for the Protestant Reformation.

Overview ● Full Text

The Ninety-Five Theses protest against clerical abuses, especially nepotism, simony, usury, pluralism, and the sale of indulgences.

It is believed that, according to university custom, on October 31, 1517, Luther posted the Ninety-Five Theses on the door of All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg.

In those days it was common for scholars to announce a debate by posting a list of Quaestiones Disputatae (disputed questions) on the door of the main church in town. People would gather to hear their scholars debate. It is likely that Luther posted his Ninety-Five Theses for this purpose.

The full text of the Ninety-Five Theses follow, along with our own comments:

DISPUTATION ON THE POWER AND EFFICACY OF INDULGENCES COMMONLY KNOWN AS THE 95 THESES

BY DR. MARTIN LUTHER

Out of love and concern for the truth, and with the object of eliciting it, the following heads will be the subject of a public discussion at Wittenberg under the presidency of the reverend father, Martin Luther, Augustinian, Master of Arts and Sacred Theology, and duly appointed Lecturer on these subjects in that place. He requests that whoever cannot be present personally to debate the matter orally will do so in absence in writing.

Out of love and concern for the truth . Martin Luther is concerned with truth. Truth needed to shine forth to everybody. It had long been obscured by Catholic clerics.

THESIS 1. When our Lord and Master, Jesus Christ, said “Repent”, He called for the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.

THESIS 2. The word cannot be properly understood as referring to the sacrament of penance, i.e. confession and satisfaction, as administered by the clergy.

cannot be … the sacrament of penance . Centuries of tradition had eroded sacramental confession to a powerless ritual. It was commonly done by rote. People often confessed the same sins over and over. Clerics were bored with it, and they merely consulted manuals that told them what penance to assign.

THESIS 3. Yet its meaning is not restricted to repentance in one’s heart; for such repentance is null unless it produces outward signs in various mortifications of the flesh.

produces outward signs . It is one thing to feel sorry for your sins. It is another thing altogether to change your life accordingly. The weakness in sacramental confession is that it requires sorrow, but does not require people to change their lives.

THESIS 4. As long as hatred of self abides (i.e. true inward repentance) the penalty of sin abides, viz., until we enter the kingdom of heaven.

THESIS 5. The pope has neither the will nor the power to remit any penalties beyond those imposed either at his own discretion or by canon law.

The pope . Here we get to the crux of the matter. For centuries, the Catholic church had popes who were corrupt.

THESIS 6. The pope himself cannot remit guilt, but only declare and confirm that it has been remitted by God; or, at most, he can remit it in cases reserved to his discretion. Except for these cases, the guilt remains untouched.

himself cannot remit guilt . Many people have the mistaken notion that a cleric forgives sin.

declare and confirm that it has been remitted by God . The truth is that only God can forgive sin.

THESIS 7. God never remits guilt to anyone without, at the same time, making him humbly submissive to the priest, His representative.

THESIS 8. The penitential canons apply only to men who are still alive, and, according to the canons themselves, none applies to the dead.

THESIS 9. Accordingly, the Holy Spirit, acting in the person of the pope, manifests grace to us, by the fact that the papal regulations always cease to apply at death, or in any hard case.

THESIS 10. It is a wrongful act, due to ignorance, when priests retain the canonical penalties on the dead in purgatory.

THESIS 11. When canonical penalties were changed and made to apply to purgatory, surely it would seem that tares were sown while the bishops were asleep.

tares were sown . That is, “weeds” were sown.

the bishops were asleep . The job of a shepherd is to feed and protect the people under your authority. They are called to vigilance. But many of the bishops were like corrupt politicians and thought only of themselves.

THESIS 12. In former days, the canonical penalties were imposed, not after, but before absolution was pronounced; and were intended to be tests of true contrition.

THESIS 13. Death puts an end to all the claims of the Church; even the dying are already dead to the canon laws, and are no longer bound by them.

THESIS 14. Defective piety or love in a dying person is necessarily accompanied by great fear, which is greatest where the piety or love is least.

THESIS 15. This fear or horror is sufficient in itself, whatever else might be said, to constitute the pain of purgatory, since it approaches very closely to the horror of despair.

THESIS 16. There seems to be the same difference between hell, purgatory, and heaven as between despair, uncertainty, and assurance.

the same difference . This is an interesting comparison. Charting it out, it looks like this:

THESIS 17. Of a truth, the pains of souls in purgatory ought to be abated, and charity ought to be proportionately increased.

THESIS 18. Moreover, it does not seem proved, on any grounds of reason or Scripture, that these souls are outside the state of merit, or unable to grow in grace.

on any grounds of reason or Scripture . Those are two great ways to consider an idea:

- Is it Scriptural?

- Does it make sense?

THESIS 19. Nor does it seem proved to be always the case that they are certain and assured of salvation, even if we are very certain ourselves.

THESIS 20. Therefore the pope, in speaking of the plenary remission of all penalties, does not mean “all” in the strict sense, but only those imposed by himself.

those imposed by himself . The Catholic church announces that certain sins result in a penalty of such-and-such number of years in Purgatory. Then they announce that the penalty can be reduced if you give money to the Catholic church.

THESIS 21. Hence those who preach indulgences are in error when they say that a man is absolved and saved from every penalty by the pope’s indulgences.

THESIS 22. Indeed, he cannot remit to souls in purgatory any penalty which canon law declares should be suffered in the present life.

THESIS 23. If plenary remission could be granted to anyone at all, it would be only in the cases of the most perfect, i.e. to very few.

THESIS 24. It must therefore be the case that the major part of the people are deceived by that indiscriminate and high-sounding promise of relief from penalty.

THESIS 25. The same power as the pope exercises in general over purgatory is exercised in particular by every single bishop in his bishopric and priest in his parish.

THESIS 26. The pope does excellently when he grants remission to the souls in purgatory on account of intercessions made on their behalf, and not by the power of the keys (which he cannot exercise for them).

THESIS 27. There is no divine authority for preaching that the soul flies out of the purgatory immediately the money clinks in the bottom of the chest.

the money clinks in … the chest . There was a heinous practice. The cleric announced that as soon as your money clinked into the bottom of the plate, at that very moment the soul of your loved one would be instantaneously liberated from Purgatory.

THESIS 28. It is certainly possible that when the money clinks in the bottom of the chest avarice and greed increase; but when the church offers intercession, all depends in the will of God.

THESIS 29. Who knows whether all souls in purgatory wish to be redeemed in view of what is said of St. Severinus and St. Pascal? (Note: Paschal I, pope 817-24. The legend is that he and Severinus were willing to endure the pains of purgatory for the benefit of the faithful).

THESIS 30. No one is sure of the reality of his own contrition, much less of receiving plenary forgiveness.

No one is sure of the reality of his own contrition . That is, we do not even know if our contrition is sincere.

THESIS 31. One who bona fide buys indulgence is a rare as a bona fide penitent man, i.e. very rare indeed.

THESIS 32. All those who believe themselves certain of their own salvation by means of letters of indulgence, will be eternally damned, together with their teachers.

THESIS 33. We should be most carefully on our guard against those who say that the papal indulgences are an inestimable divine gift, and that a man is reconciled to God by them.

THESIS 34. For the grace conveyed by these indulgences relates simply to the penalties of the sacramental “satisfactions” decreed merely by man.

THESIS 35. It is not in accordance with Christian doctrines to preach and teach that those who buy off souls, or purchase confessional licenses, have no need to repent of their own sins.

THESIS 36. Any Christian whatsoever, who is truly repentant, enjoys plenary remission from penalty and guilt, and this is given him without letters of indulgence.

THESIS 37. Any true Christian whatsoever, living or dead, participates in all the benefits of Christ and the Church; and this participation is granted to him by God without letters of indulgence.

participates in all the benefits of Christ and the Church . The grace of our Jesus Christ is not withheld from any Christian believer.

granted to him by God without letters of indulgence . God does not need the pope’s permission in order to grant the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ.

THESIS 38. Yet the pope’s remission and dispensation are in no way to be despised, for, as already said, they proclaim the divine remission.

THESIS 39. It is very difficult, even for the most learned theologians, to extol to the people the great bounty contained in the indulgences, while, at the same time, praising contrition as a virtue.

THESIS 40. A truly contrite sinner seeks out, and loves to pay, the penalties of his sins; whereas the very multitude of indulgences dulls men’s consciences, and tends to make them hate the penalties.

the very multitude of indulgences . The selling of indulgences was a widespread practice, and people everywhere were duped.

THESIS 41. Papal indulgences should only be preached with caution, lest people gain a wrong understanding, and think that they are preferable to other good works: those of love.

THESIS 42. Christians should be taught that the pope does not at all intend that the purchase of indulgences should be understood as at all comparable with the works of mercy.

THESIS 43. Christians should be taught that one who gives to the poor, or lends to the needy, does a better action than if he purchases indulgences.

does a better action . It is far better to live the Christian life than to purchase indulgences.

THESIS 44. Because, by works of love, love grows and a man becomes a better man; whereas, by indulgences, he does not become a better man, but only escapes certain penalties.

THESIS 45. Christians should be taught that he who sees a needy person, but passes him by although he gives money for indulgences, gains no benefit from the pope’s pardon, but only incurs the wrath of God.

THESIS 46. Christians should be taught that, unless they have more than they need, they are bound to retain what is only necessary for the upkeep of their home, and should in no way squander it on indulgences.

squander it on indulgences . To purchase an indulgence is to squander your money.

THESIS 47. Christians should be taught that they purchase indulgences voluntarily, and are not under obligation to do so.

THESIS 48. Christians should be taught that, in granting indulgences, the pope has more need, and more desire, for devout prayer on his own behalf than for ready money.

THESIS 49. Christians should be taught that the pope’s indulgences are useful only if one does not rely on them, but most harmful if one loses the fear of God through them.

THESIS 50. Christians should be taught that, if the pope knew the exactions of the indulgence-preachers, he would rather the church of St. Peter were reduced to ashes than be built with the skin, flesh, and bones of the sheep.

if the pope knew the exactions of the indulgence-preachers . Did the pope know what the indulgence preachers were saying?

the church of St. Peter were reduced to ashes . Would a pope really prefer the Vatical to be burned to the ground than to give up the profit from the selling of indulgences?

THESIS 51. Christians should be taught that the pope would be willing, as he ought if necessity should arise, to sell the church of St. Peter, and give, too, his own money to many of those from whom the pardon-merchants conjure money.

THESIS 52. It is vain to rely on salvation by letters of indulgence, even if the commissary, or indeed the pope himself, were to pledge his own soul for their validity.

THESIS 53. Those are enemies of Christ and the pope who forbid the word of God to be preached at all in some churches, in order that indulgences may be preached in others.

THESIS 54. The word of God suffers injury if, in the same sermon, an equal or longer time is devoted to indulgences than to that word.

THESIS 55. The pope cannot help taking the view that if indulgences (very small matters) are celebrated by one bell, one pageant, or one ceremony, the gospel (a very great matter) should be preached to the accompaniment of a hundred bells, a hundred processions, a hundred ceremonies.

THESIS 56. The treasures of the church, out of which the pope dispenses indulgences, are not sufficiently spoken of or known among the people of Christ.

THESIS 57. That these treasures are not temporal are clear from the fact that many of the merchants do not grant them freely, but only collect them.

THESIS 58. Nor are they the merits of Christ and the saints, because, even apart from the pope, these merits are always working grace in the inner man, and working the cross, death, and hell in the outer man.

THESIS 59. St. Laurence said that the poor were the treasures of the church, but he used the term in accordance with the custom of his own time.

the poor were the treasures of the church . This was a noble thing for Laurence to say. And for it, Emperor Valerian executed him.

THESIS 60. We do not speak rashly in saying that the treasures of the church are the keys of the church, and are bestowed by the merits of Christ.

THESIS 61. For it is clear that the power of the pope suffices, by itself, for the remission of penalties and reserved cases.

THESIS 62. The true treasure of the church is the Holy gospel of the glory and the grace of God.

the Holy gospel . This is the greatest thing that we Christians have: the Good News of the Lord Jesus Christ.

THESIS 63. It is right to regard this treasure as most odious, for it makes the first to be the last.

THESIS 64. On the other hand, the treasure of indulgences is most acceptable, for it makes the last to be the first.

THESIS 65. Therefore the treasures of the gospel are nets which, in former times, they used to fish for men of wealth.

men of wealth . Only those who are wealthy enough to purchase an indulgence could be saved.

THESIS 66. The treasures of the indulgences are the nets which to-day they use to fish for the wealth of men.

THESIS 67. The indulgences, which the merchants extol as the greatest of favours, are seen to be, in fact, a favourite means for money-getting.

THESIS 68. Nevertheless, they are not to be compared with the grace of God and the compassion shown in the Cross.

THESIS 69. Bishops and curates, in duty bound, must receive the commissaries of the papal indulgences with all reverence.

THESIS 70. But they are under a much greater obligation to watch closely and attend carefully lest these men preach their own fancies instead of what the pope commissioned.

THESIS 71. Let him be anathema and accursed who denies the apostolic character of the indulgences.

THESIS 72. On the other hand, let him be blessed who is on his guard against the wantonness and license of the pardon-merchant’s words.

THESIS 73. In the same way, the pope rightly excommunicates those who make any plans to the detriment of the trade in indulgences.

THESIS 74. It is much more in keeping with his views to excommunicate those who use the pretext of indulgences to plot anything to the detriment of holy love and truth.

THESIS 75. It is foolish to think that papal indulgences have so much power that they can absolve a man even if he has done the impossible and violated the mother of God.

THESIS 76. We assert the contrary, and say that the pope’s pardons are not able to remove the least venial of sins as far as their guilt is concerned.

are not able to remove the least . God is the one who forgives of sins.

THESIS 77. When it is said that not even St. Peter, if he were now pope, could grant a greater grace, it is blasphemy against St. Peter and the pope.

THESIS 78. We assert the contrary, and say that he, and any pope whatever, possesses greater graces, viz., the gospel, spiritual powers, gifts of healing, etc., as is declared in I Corinthians 12:28.

I Corinthians 12:28 . God has set some in the assembly: first apostles, second prophets, third teachers, then miracle workers, then gifts of healings, helps, governments, and various kinds of languages.

THESIS 79. It is blasphemy to say that the insignia of the cross with the papal arms are of equal value to the cross on which Christ died.

equal value to the cross . How could people imagine such a thing?

THESIS 80. The bishops, curates, and theologians, who permit assertions of that kind to be made to the people without let or hindrance, will have to answer for it.

THESIS 81. This unbridled preaching of indulgences makes it difficult for learned men to guard the respect due to the pope against false accusations, or at least from the keen criticisms of the laity.

THESIS 82. They ask, e.g.: Why does not the pope liberate everyone from purgatory for the sake of love (a most holy thing) and because of the supreme necessity of their souls? This would be morally the best of all reasons. Meanwhile he redeems innumerable souls for money, a most perishable thing, with which to build St. Peter’s church, a very minor purpose.

for the sake of love . Love would motivate the pope to liberate people from Purgatory without them needing to PAY FOR IT.

he redeems innumerable souls for money . Instead, the pope only liberated people from Purgatory if they would PAY FOR IT.

THESIS 83. Again: Why should funeral and anniversary masses for the dead continue to be said? And why does not the pope repay, or permit to be repaid, the benefactions instituted for these purposes, since it is wrong to pray for those souls who are now redeemed?

THESIS 84. Again: Surely this is a new sort of compassion, on the part of God and the pope, when an impious man, an enemy of God, is allowed to pay money to redeem a devout soul, a friend of God; while yet that devout and beloved soul is not allowed to be redeemed without payment, for love’s sake, and just because of its need of redemption.

THESIS 85. Again: Why are the penitential canon laws, which in fact, if not in practice, have long been obsolete and dead in themselves,—why are they, to-day, still used in imposing fines in money, through the granting of indulgences, as if all the penitential canons were fully operative?

THESIS 86. Again: since the pope’s income to-day is larger than that of the wealthiest of wealthy men, why does he not build this one church of St. Peter with his own money, rather than with the money of indigent believers?

the pope’s income … is larger than that of the wealthiest . The pope misused the millions of Catholics around the world as his own income stream.

THESIS 87. Again: What does the pope remit or dispense to people who, by their perfect repentance, have a right to plenary remission or dispensation?

THESIS 88. Again: Surely a greater good could be done to the church if the pope were to bestow these remissions and dispensations, not once, as now, but a hundred times a day, for the benefit of any believer whatever.

THESIS 89. What the pope seeks by indulgences is not money, but rather the salvation of souls; why then does he suspend the letters and indulgences formerly conceded, and still as efficacious as ever?

THESIS 90. These questions are serious matters of conscience to the laity. To suppress them by force alone, and not to refute them by giving reasons, is to expose the church and the pope to the ridicule of their enemies, and to make Christian people unhappy.

THESIS 91. If therefore, indulgences were preached in accordance with the spirit and mind of the pope, all these difficulties would be easily overcome, and indeed, cease to exist.

THESIS 92. Away, then, with those prophets who say to Christ’s people, “Peace, peace,” where in there is no peace.

THESIS 93. Hail, hail to all those prophets who say to Christ’s people, “The cross, the cross,” where there is no cross.

THESIS 94. Christians should be exhorted to be zealous to follow Christ, their Head, through penalties, deaths, and hells.

be zealous to follow Christ . This is the goal for any Christian: to wholeheartedly follow Jesus Christ.

THESIS 95. And let them thus be more confident of entering heaven through many tribulations rather than through a false assurance of peace.

This text of “The 95 Theses by Dr. Martin Luther” courtesy of Senn High School. There are no stated copyright restrictions and the translation is assumed to be in the Public Domain.

Unless otherwise noted, all Bible quotations on this page are from the World English Bible and the World Messianic Edition . These translations have no copyright restrictions. They are in the Public Domain.

- Harz Mountains

- Quedlinburg

- Wernigerode

- Harz Fairy Tales

- Berchtesgaden Area

- Berchtesgaden Town

- Eagle's Nest

- Hitler's Berghof

- Obersalzberg

- Braunau am Inn

- Wartburg Castle

- Martin Luther

- Hogan's Heroes

- Colditz Castle

- Flights to Germany

Martin Luther's 95 Theses

Here they are, all of the Martin Luther 95 theses, posted on the church door in Wittenberg, Germany, October 31, 1517 .

(Or read a summary of the 95 theses .)

Jump to sections in the text...

Out of love for the truth and from desire to elucidate it, the Reverend Father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and Sacred Theology, and ordinary lecturer therein at Wittenberg, intends to defend the following statements and to dispute on them in that place. Therefore he asks that those who cannot be present and dispute with him orally shall do so in their absence by letter. In the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, Amen.

1. Our Lord and Master Jesus Christ, in saying, "Repent ye, etc.," intended that the whole life of his believers on earth should be a constant penance.

2. And the word "penance" neither can, nor may, be understood as referring to the Sacrament of Penance, that is, to confession and atonement as exercised under the priest's ministry.

3. Nevertheless He does not think of inward penance only: rather is inward penance worthless unless it produces various outward mortifications of the flesh.

4. Therefore mortification continues as long as hatred of oneself continues, that is to say, true inward penance lasts until entrance into the Kingdom of Heaven.

5. The Pope will not, and cannot, remit other punishments than those which he has imposed by his own decree or according to the canons.

6. The Pope can forgive sins only in the sense, that he declares and confirms what may be forgiven of God; or that he doth it in those cases which he hath reserved to himself; be this contemned, the sin remains unremitted.

7. God forgives none his sin without at the same time casting him penitent and humbled before the priest His vicar.

8. The canons concerning penance are imposed only on the living; they ought not by any means, following the same canons, to be imposed on the dying.

9. Therefore, the Holy Spirit, acting in the Pope, does well for us, when the latter in his decrees entirely removes the article of death and extreme necessity.

10. Those priests act unreasonably and ill who reserve for Purgatory the penance imposed on the dying.

11. This abuse of changing canonical penalty into the penalty of Purgatory seems to have arisen when the bishops were asleep.

12. In times of yore, canonical penalties were imposed, not after, but before, absolution, as tests of true repentance and affliction.

13. The dying pay all penalties by their death, are already dead to the canons, and rightly have exemption from them.

14. Imperfect spiritual health or love in the dying person necessarily brings with it great fear; and the less this love is, the greater the fear it brings.

15. This fear and horror - to say nothing of other things - are sufficient in themselves to produce the punishment of Purgatory, because they approximate to the horror of despair.

16. Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven seem to differ as perfect despair, imperfect despair, and security of salvation differ.

17. It seems as must in Purgatory love in the souls increase, as fear diminishes in them.

18. It does not seem to be proved either by arguments or by the Holy Writ that they are outside the state of merit and demerit, or increase of love.

19. This, too, seems not to be proved, that they are all sure and confident of their salvation, though we may be quite sure of it.

20. Therefore the Pope, in speaking of the perfect remission of all punishments, does not mean that all penalties in general be forgiven, but only those imposed by himself.

21. Therefore, those preachers of indulgences err who say that, by the Pope's indulgence, a man may be exempt from all punishments, and be saved.

22. Yea, the Pope remits the souls in Purgatory no penalty which they, according to the canons, would have had to pay in this life.

23. If to anybody complete remission of all penalties may be granted, it is certain that it is granted only to those most approaching perfection, that is, to very few.

24. Therefore the multitude is misled by the boastful promise of the paid penalty, whereby no manner of distinction is made.

25. The same power that the Pope has over Purgatory, such has also every bishop in his diocese, and every curate in his parish.

26. The Pope acts most rightly in granting remission to souls, not by the power of the keys - which in Purgatory he does not possess - but by way of intercession.

27. They preach vanity who say that the soul flies out of Purgatory as soon as the money thrown into the chest rattles.

28. What is sure, is, that as soon as the penny rattles in the chest, gain and avarice are on the way of increase; but the intercession of the church depends only on the will of God Himself.

29. And who knows, too, whether all those souls in Purgatory wish to be redeemed, as it is said to have happened with St. Severinus and St. Paschalis.

30. Nobody is sure of having repented sincerely enough; much less can he be sure of having received perfect remission of sins.

31. Seldom even as he who has sincere repentance, is he who really gains indulgence; that is to say, most seldom to be found.

32. On the way to eternal damnation are they and their teachers, who believe that they are sure of their salvation through indulgences.

33. Beware well of those who say, the Pope's pardons are that inestimable gift of God by which man is reconciled to God.

34. For the forgiveness contained in these pardons has reference only to the penalties of sacramental atonement which were appointed by men.

35. He preaches like a heathen who teaches that those who will deliver souls out of Purgatory or buy indulgences do not need repentance and contrition.

36. Every Christian who feels sincere repentance and woe on account of his sins, has perfect remission of pain and guilt even without letters of indulgence.

37. Every true Christian, be he still alive or already dead, partaketh in all benefits of Christ and of the Church given him by God, even without letters of indulgence.

38. Yet is the Pope's absolution and dispensation by no means to be contemned, since it is, as I have said, a declaration of the Divine Absolution.

39. It is exceedingly difficult, even for the most subtle theologists, to praise at the same time before the people the great wealth of indulgence and the truth of utter contrition.

40. True repentance and contrition seek and love punishment; while rich indulgence absolves from it, and causes men to hate it, or at least gives them occasion to do so.

41. The Pope's indulgence ought to be proclaimed with all precaution, lest the people should mistakenly believe it of more value than all other works of charity.

42. Christians should be taught, it is not the Pope's opinion that the buying of indulgence is in any way comparable to works of charity.

43. Christians should be taught, he who gives to the poor, or lends to a needy man, does better than buying indulgence.

44. For, by the exercise of charity, charity increases and man grows better, while by means of indulgence, he does not become better, but only freer from punishment.

45. Christians should be taught, he who sees his neighbor in distress, and, nevertheless, buys indulgence, is not partaking in the Pope's pardons, but in the anger of God.

46. Christians should be taught, unless they are rich enough, it is their duty to keep what is necessary for the use of their households, and by no means to throw it away on indulgences.

47. Christians should be taught, the buying of indulgences is optional and not commanded.

48. Christians should be taught, the Pope, in selling pardons, has more want and more desire of a devout prayer for himself than of the money.

49. Christians should be taught, the Pope's pardons are useful as far as one does not put confidence in them, but on the contrary most dangerous, if through them one loses the fear of God.

50. Christians should be taught, if the Pope knew the ways and doings of the preachers of indulgences, he would prefer that St. Peter's Minster should be burnt to ashes, rather than that it should be built up of the skin, flesh, and bones of his lambs.

51. Christians should be taught, the Pope, as it is his bounden duty to do, is indeed also willing to give of his own money - and should St. Peter's be sold thereto - to those from whom the preachers of indulgences do most extort money.

52. It is a vain and false thing to hope to be saved through indulgences, though the commissary - nay, the Pope himself - was to pledge his own soul therefore.

53. Those who, on account of a sermon concerning indulgences in one church, condemn the word of God to silence in the others, are enemies of Christ and of the Pope.

54. Wrong is done to the word of God if one in the same sermon spends as much or more time on indulgences as on the word of the Gospel.

55. The opinion of the Pope cannot be otherwise than this:- If an indulgence - which is the lowest thing - be celebrated with one bell, one procession and ceremonies, then the Gospel - which is the highest thing - must be celebrated with a hundred bells, a hundred processions, and a hundred ceremonies.

56. The treasures of the Church, whence the Pope grants his dispensation are neither sufficiently named nor known among the community of Christ.

57. It is manifest that they are not temporal treasures, for the latter are not lightly spent, but rather gathered by many of the preachers.

58. Nor are they the merits of Christ and of the saints, for these, without the Pope's aid, work always grace to the inner man, cross, death, and hell to the other man.

59. St. Lawrence called the poor of the community the treasures of the community and of the Church, but he understood the word according to the use in his time.

60. We affirm without pertness that the keys of the Church, bestowed through the merit of Christ, are this treasure.

61. For it is clear that the Pope's power is sufficient for the remission of penalties and forgiveness in the reserved cases.

62. The right and true treasure of the Church is the most Holy Gospel of the glory and grace of God.

63. This treasure, however, is deservedly most hateful, for it makes the first to be last.

64. While the treasure of indulgence is deservedly most agreeable, for it makes the last to be first.

65. Therefore, the treasures of the Gospel are nets, with which, in times of yore, one fished for the men of Mammon.

66. But the treasures of indulgence are nets, with which now-a-days one fishes for the Mammon of men.

67. Those indulgences, which the preachers proclaim to be great mercies, are indeed great mercies, forasmuch as they promote gain.

68. And yet they are of the smallest compared to the grace of God and to the devotion of the Cross.

69. Bishops and curates ought to mark with eyes and ears, that the commissaries of apostolical (that is, Popish) pardons are received with all reverence.

70. But they ought still more to mark with eyes and ears, that these commissaries do not preach their own fancies instead of what the Pope has commanded.

71. He who speaks against the truth of apostolical pardons, be anathema and cursed.

72. But blessed be he who is on his guard against the preacher's of pardons naughty and impudent words.

73. As the Pope justly disgraces and excommunicates those who use any kind of contrivance to do damage to the traffic in indulgences.

74. Much more it is his intention to disgrace and excommunicate those who, under the pretext of indulgences, use contrivance to do damage to holy love and truth.

75. To think that the Popish pardons have power to absolve a man even if - to utter an impossibility - he had violated the Mother of God, is madness.

76. We assert on the contrary that the Popish pardon cannot take away the least of daily sins, as regards the guilt of it.

77. To say that St. Peter, if he were now Pope, could show no greater mercies, is blasphemy against St. Peter and the Pope.

78. We assert on the contrary that both this and every other Pope has greater mercies to show: namely, the Gospel, spiritual powers, gifts of healing, etc. (1.Cor.XII).

79. He who says that the cross with the Pope's arms, solemnly set on high, has as much power as the Cross of Christ, blasphemes God.

80. Those bishops, curates, and theologists, who allow such speeches to be uttered among the people, will have one day to answer for it.

81. Such impudent sermons concerning indulgences make it difficult even for learned men to protect the Pope's honor and dignity against the calumnies, or at all events against the searching questions, of the laymen.

82. As for instance: - Why does not the Pope deliver all souls at the same time out of Purgatory for the sake of most holy love and on account of the bitterest distress of those souls - this being the most imperative of all motives, - while he saves an infinite number of souls for the sake of that most miserable thing money, to be spent on St. Peter's Minster: - this being the very slightest of motives?

83. Or again: - Why do masses for the dead continue, and why does not the Pope return or permit to be withdrawn the funds which were established for the sake of the dead, since it is now wrong to pray for those who are already saved?

84. Again: - What is this new holiness of God and the Pope that, for money's sake, they permit the wicked and the enemy of God to save a pious soul, faithful to God, and yet will not save that pious and beloved soul without payment, out of love, and on account of its great distress?

85. Again: - Why is it that the canons of penance, long abrogated and dead in themselves, because they are not used, are yet still paid for with money through the granting of pardons, as if they were still in force and alive?

86. Again: - Why does not the Pope build St. Peter's Minster with his own money - since his riches are now more ample than those of Crassus, - rather than with the money of poor Christians?

87. Again: -Why does the Pope remit or give to those who, through perfect penitence, have already a right to plenary remission and pardon?

88. Again: - What greater good could the Church receive, than if the Pope presented this remission and pardon a hundred times a day to every believer, instead of but once, as he does now?

89. If the Pope seeks by his pardon the salvation of souls, rather than money, why does he annul letters of indulgence granted long ago, and declare them out of force, though they are still in force?

90. To repress these very telling questions of the laymen by force, and not to solve them by telling the truth, is to expose the Church and the Pope to the enemy's ridicule and to make Christian people unhappy.

91. Therefore, if pardons were preached according to the Pope's intention and opinion, all these objections would be easily answered, nay, they never had occurred.

92. Away then with all those prophets who say to the community of Christ, "Peace, peace", and there is no peace.

93. But blessed be all those prophets who say to the community of Christ, "The cross, the cross," and there is no cross.

94. Christians should be exhorted to endeavor to follow Christ their Head through Cross, Death, and Hell,

95. And thus hope with confidence to enter Heaven through many miseries, rather than in false security.

Read a summary of the 95 theses ; a listing of the three main points , in the words of Martin Luther.

More Martin Luther...

- The 95 Theses

Share this page:

Hello and Guten Tag!

I'm Karen and I've created this website to share my collection of interesting, and often unusual, places to visit in Germany.

I'm a California native, but I lived in Germany for several years, and have made numerous visits back there to explore this fascinating country... off the beaten track.

More about me...

Traveling in Germany

Check the German Rail website (Deutschebahn) for train and bus schedules, prices, and ticket bookings.

Find a place to stay in Germany...

Home Sitemap About Me

Privacy Policy Contact Me

Use Policy Affiliate Disclosure

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Uncommon-Travel-Germany.com

Justification by Allegiance

Thursday, march 26, 2009, martin luther's 86th thesis, no comments:, post a comment, blog archive.

- Martin Luther's 95th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 94th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 93rd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 92nd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 91st Thesis

- Martin Luther's 90th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 89th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 88th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 87th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 86th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 85th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 84th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 83rd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 82nd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 81st Thesis

- Martin Luther's 80th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 79th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 78th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 77th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 76th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 75th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 74th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 73rd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 72nd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 71st Thesis

- Martin Luther's 70th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 69th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 68th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 67th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 66th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 65th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 64th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 63rd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 62nd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 61st Thesis

- Martin Luther's 60th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 59th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 58th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 57th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 56th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 55th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 54th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 53rd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 52nd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 51st Thesis

- Martin Luther's 50th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 49th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 48th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 47th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 46th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 45th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 44th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 43rd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 42nd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 41st Thesis

- Martin Luther's 40th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 39th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 38th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 37th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 36th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 35th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 34th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 33rd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 32nd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 31st Thesis

- Martin Luther's 30th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 29th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 28th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 27th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 26th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 25th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 24th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 23rd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 22nd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 21st Thesis

- Martin Luther's 20th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 19th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 18th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 17th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 16th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 15th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 14th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 13th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 12th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 11th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 10th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 9th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 8th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 7th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 6th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 5th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 4th Thesis

- Martin Luther's 3rd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 2nd Thesis

- Martin Luther's 1st Thesis

- Is it Time to Put "Justification by Faith" to Rest?

The Protestant Reformation

Protestantism, discontent with the roman catholic church.

The Protestant Reformation was the schism within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin, and other early Protestants.

Learning Objectives

Explain the main motivating factors behind the Protestant Reformation

Key Takeaways

- The Reformation began as an attempt to reform the Roman Catholic Church, by priests who opposed what they perceived as false doctrines and ecclesiastic malpractice.

- Following the breakdown of monastic institutions and scholasticism in late medieval Europe, accentuated by the Avignon Papacy, the Papal Schism, and the failure of the Conciliar movement, the 16th century saw a great cultural debate about religious reforms and later fundamental religious values. John Wycliffe and Jan Hus were early opponents of papal authority, and their work and views paved the way for the Reformation.

- Martin Luther was a seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation who strongly disputed the sale of indulgences. His Ninety-Five Theses criticized many of the doctrines and practices of the Catholic Church.

- The Roman Catholic Church responded with a Counter-Reformation spearheaded by the new order of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), specifically organized to counter the Protestant movement.

- Conciliar movement : A reform movement in the 14th-, 15th-, and 16th-century Catholic Church that held that supreme authority in the church resided with an Ecumenical council, apart from, or even against, the pope. The movement emerged in response to the Western Schism between rival popes in Rome and Avignon.

- the Western Schism : A split within the Catholic Church from 1378 to 1418, when several men simultaneously claimed to be the true pope.

- doctrine : List of beliefs and teachings by the church.

- ecclesiastic : One who adheres to a church-based philosophy.

- indulgences : In Catholic theology, a remission of the punishment that would otherwise be inflicted for a previously forgiven sin as a natural consequence of having sinned. They are granted for specific good works and prayers in proportion to the devotion with which those good works are performed or prayers recited.

- Council of Trent : Council of the Roman Catholic Church set up in Trento, Italy, in direct response to the Reformation.

The Protestant Reformation, often referred to simply as the Reformation, was a schism from the Roman Catholic Church initiated by Martin Luther and continued by other early Protestant reformers in Europe in the 16th century.

Although there had been significant earlier attempts to reform the Roman Catholic Church before Luther—such as those of Jan Hus, Geert Groote, Thomas A Kempis, Peter Waldo, and John Wycliffe—Martin Luther is widely acknowledged to have started the Reformation with his 1517 work The Ninety-Five Theses.

Luther began by criticizing the selling of indulgences, insisting that the pope had no authority over purgatory and that the Catholic doctrine of the merits of the saints had no foundation in the gospel. The Protestant position, however, would come to incorporate doctrinal changes such as sola scriptura (by the scripture alone) and sola fide (by faith alone). The core motivation behind these changes was theological, though many other factors played a part, including the rise of nationalism, the Western Schism that eroded faith in the papacy, the perceived corruption of the Roman Curia, the impact of humanism, and the new learning of the Renaissance that questioned much traditional thought.

Roots of Unrest

Following the breakdown of monastic institutions and scholasticism in late medieval Europe, accentuated by the Avignon Papacy, the Papal Schism, and the failure of the Conciliar movement, the 16th century saw a great cultural debate about religious reforms and later fundamental religious values. These issues initiated wars between princes, uprisings among peasants, and widespread concern over corruption in the Church, which sparked many reform movement within the church.

These reformist movements occurred in conjunction with economic, political, and demographic forces that contributed to a growing disaffection with the wealth and power of the elite clergy, sensitizing the population to the financial and moral corruption of the secular Renaissance church.

The major individualistic reform movements that revolted against medieval scholasticism and the institutions that underpinned it were humanism, devotionalism, and the observantine tradition. In Germany, “the modern way,” or devotionalism, caught on in the universities, requiring a redefinition of God, who was no longer a rational governing principle but an arbitrary, unknowable will that could not be limited. God was now a ruler, and religion would be more fervent and emotional. Thus, the ensuing revival of Augustinian theology, stating that man cannot be saved by his own efforts but only by the grace of God, would erode the legitimacy of the rigid institutions of the church meant to provide a channel for man to do good works and get into heaven.

Humanism, however, was more of an educational reform movement with origins in the Renaissance’s revival of classical learning and thought. A revolt against Aristotelian logic, it placed great emphasis on reforming individuals through eloquence as opposed to reason. The European Renaissance laid the foundation for the Northern humanists in its reinforcement of the traditional use of Latin as the great unifying language of European culture. Since the breakdown of the philosophical foundations of scholasticism, the new nominalism did not bode well for an institutional church legitimized as an intermediary between man and God. New thinking favored the notion that no religious doctrine can be supported by philosophical arguments, eroding the old alliance between reason and faith of the medieval period laid out by Thomas Aquinas.

The great rise of the burghers (merchant class) and their desire to run their new businesses free of institutional barriers or outmoded cultural practices contributed to the appeal of humanist individualism. To many, papal institutions were rigid, especially regarding their views on just price and usury. In the north, burghers and monarchs were united in their frustration for not paying any taxes to the nation, but collecting taxes from subjects and sending the revenues disproportionately to the pope in Italy.

Early Attempts at Reform

The first of a series of disruptive and new perspectives came from John Wycliffe at Oxford University, one of the earliest opponents of papal authority influencing secular power and an early advocate for translation of the Bible into the common language. Jan Hus at the University of Prague was a follower of Wycliffe and similarly objected to some of the practices of the Roman Catholic Church. Hus wanted liturgy in the language of the people (i.e. Czech), married priests, and to eliminate indulgences and the idea of purgatory.