- ResearchWorks Home

- Dissertations and Theses

Essays on Globalization and Structural Change

Collections

- Economics [179]

Trade and Globalization

How did international trade and globalization change over time? What is the structure today? And what is its impact?

By: Esteban Ortiz-Ospina , Diana Beltekian and Max Roser

This page was first published in 2014 and last revised in April 2024.

On this topic page, you can find data, visualizations, and research on historical and current patterns of international trade, as well as discussions of their origins and effects.

Other research and writing on trade and globalization on Our World in Data:

- Is globalization an engine of economic development?

- Is trade a major driver of income inequality?

Related topics

Economic Growth

See all our data, visualizations, and writing on economic growth.

Economic Inequality

See all our data, visualizations, and writing on economic inequality.

See all our data, visualizations, and writing on migration.

See all interactive charts on Trade and Globalization ↓

Trade has changed the world economy

Trade has grown remarkably over the last century.

One of the most important developments of the last century has been the integration of national economies into a global economic system. This process of integration, often called globalization, has resulted in a remarkable growth in trade between countries.

The chart here shows the growth of world exports over more than the last two centuries. These estimates are in constant prices (i.e. have been adjusted to account for inflation) and are indexed at 1913 values.

The chart shows an extraordinary growth in international trade over the last couple of centuries: Exports today are more than 40 times larger than in 1913.

You can switch to a logarithmic scale under ‘Settings’. This will help you see that, over the long run, growth has roughly followed an exponential path.

The increase in trade has even outpaced economic growth

The chart above shows how much more trade we have today relative to a century ago. But what about trade relative to total economic output?

Over the last couple of centuries the world economy has experienced sustained positive economic growth , so looking at changes in trade relative to GDP offers another interesting perspective.

The next chart plots the value of traded goods relative to GDP (i.e. the value of merchandise trade as a share of global economic output).

Up to 1870, the sum of worldwide exports accounted for less than 10% of global output. Today, the value of exported goods around the world is around 25%. This shows that over the last hundred years, the growth in trade has even outpaced rapid economic growth.

Trade expanded in two waves

The first "wave of globalization" started in the 19th century, the second one after ww2.

The following visualization presents a compilation of available trade estimates, showing the evolution of world exports and imports as a share of global economic output .

This metric (the ratio of total trade, exports plus imports, to global GDP) is known as the “openness index”. The higher the index, the higher the influence of trade transactions on global economic activity. 1

As we can see, until 1800 there was a long period characterized by persistently low international trade – globally the index never exceeded 10% before 1800. This then changed over the course of the 19th century, when technological advances triggered a period of marked growth in world trade – the so-called “first wave of globalization”.

This first wave came to an end with the beginning of World War I, when the decline of liberalism and the rise of nationalism led to a slump in international trade. In the chart we see a large drop in the interwar period.

After World War II trade started growing again. This new – and ongoing – wave of globalization has seen international trade grow faster than ever before. Today the sum of exports and imports across nations amounts to more than 50% of the value of total global output. 2

Before the first wave of globalization, trade was driven mostly by colonialism

Over the early modern period, transoceanic flows of goods between empires and colonies accounted for an important part of international trade. The following visualizations provide a comparison of intercontinental trade, in per capita terms, for different countries.

As we can see, intercontinental trade was very dynamic, with volumes varying considerably across time and from empire to empire.

Leonor Freire Costa, Nuno Palma, and Jaime Reis, who compiled and published the original data shown here, argue that trade, also in this period, had a substantial positive impact on the economy. 3

The first wave of globalization was marked by the rise and collapse of intra-European trade

The following visualization shows a detailed overview of Western European exports by destination. Figures correspond to export-to-GDP ratios (i.e. the sum of the value of exports from all Western European countries, divided by the total GDP in this region). You can use “Settings” to switch to a relative view and see the proportional contribution of each region to total Western European exports.

This chart shows that growth in Western European trade throughout the 19th century was largely driven by trade within the region: In the period 1830-1900 intra-European exports went from 1% of GDP to 10% of GDP, and this meant that the relative weight of intra-European exports doubled over the period. However, this process of European integration then collapsed sharply in the interwar period.

After the Second World War trade within Europe rebounded, and from the 1990s onwards exceeded the highest levels of the first wave of globalization. In addition, Western Europe then started to increasingly trade with Asia, the Americas, and to a smaller extent Africa and Oceania.

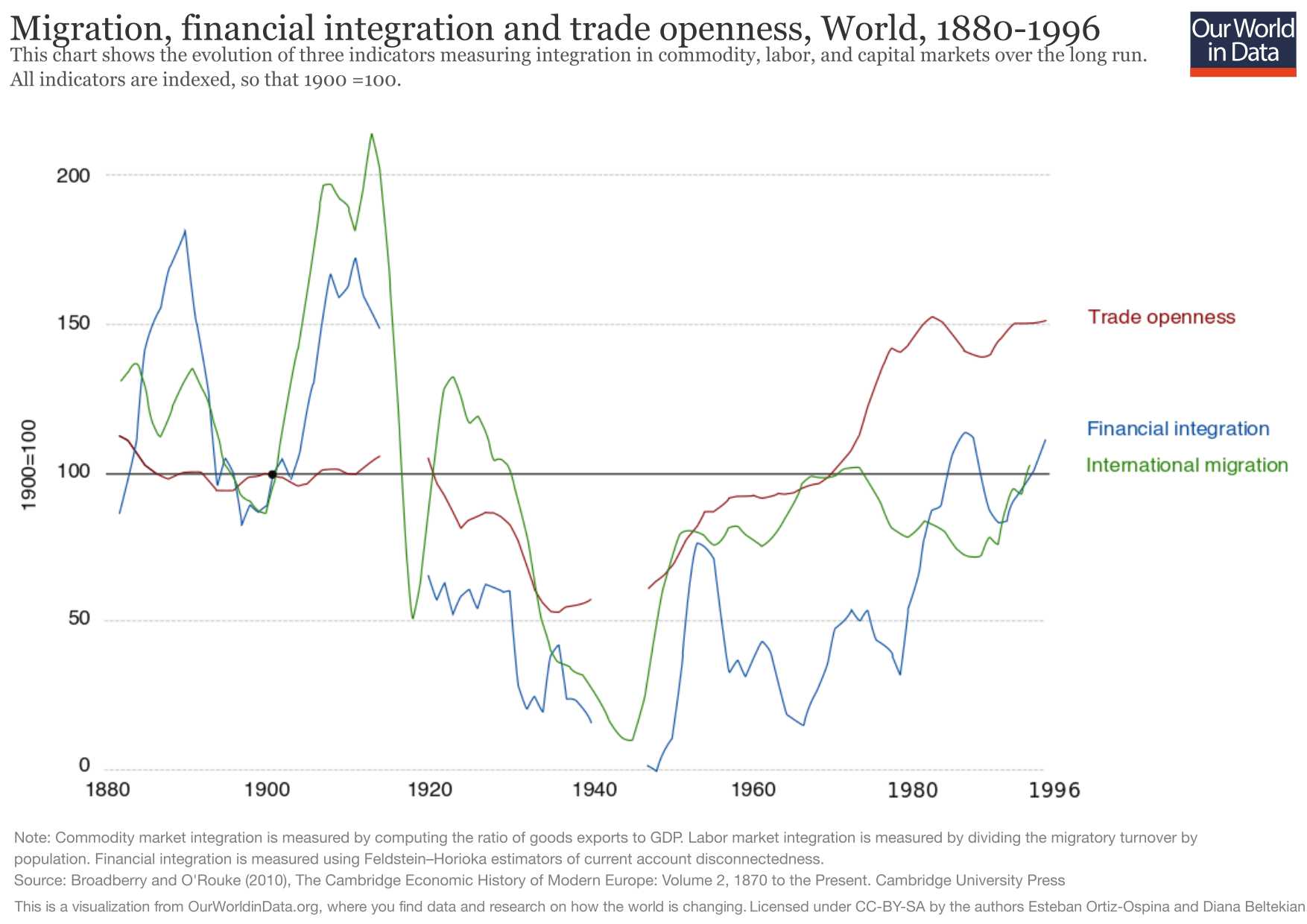

The next graph, using data from Broadberry and O'Rourke (2010) 4 , shows another perspective on the integration of the global economy and plots the evolution of three indicators measuring integration across different markets – specifically goods, labor, and capital markets.

The indicators in this chart are indexed, so they show changes relative to the levels of integration observed in 1900. This gives us another perspective on how quickly global integration collapsed with the two World Wars. 5

The second wave of globalization was enabled by technology

The worldwide expansion of trade after the Second World War was largely possible because of reductions in transaction costs stemming from technological advances, such as the development of commercial civil aviation, the improvement of productivity in the merchant marines, and the democratization of the telephone as the main mode of communication. The visualization shows how, at the global level, costs across these three variables have been going down since 1930.

Reductions in transaction costs impacted not only the volumes of trade but also the types of exchanges that were possible and profitable.

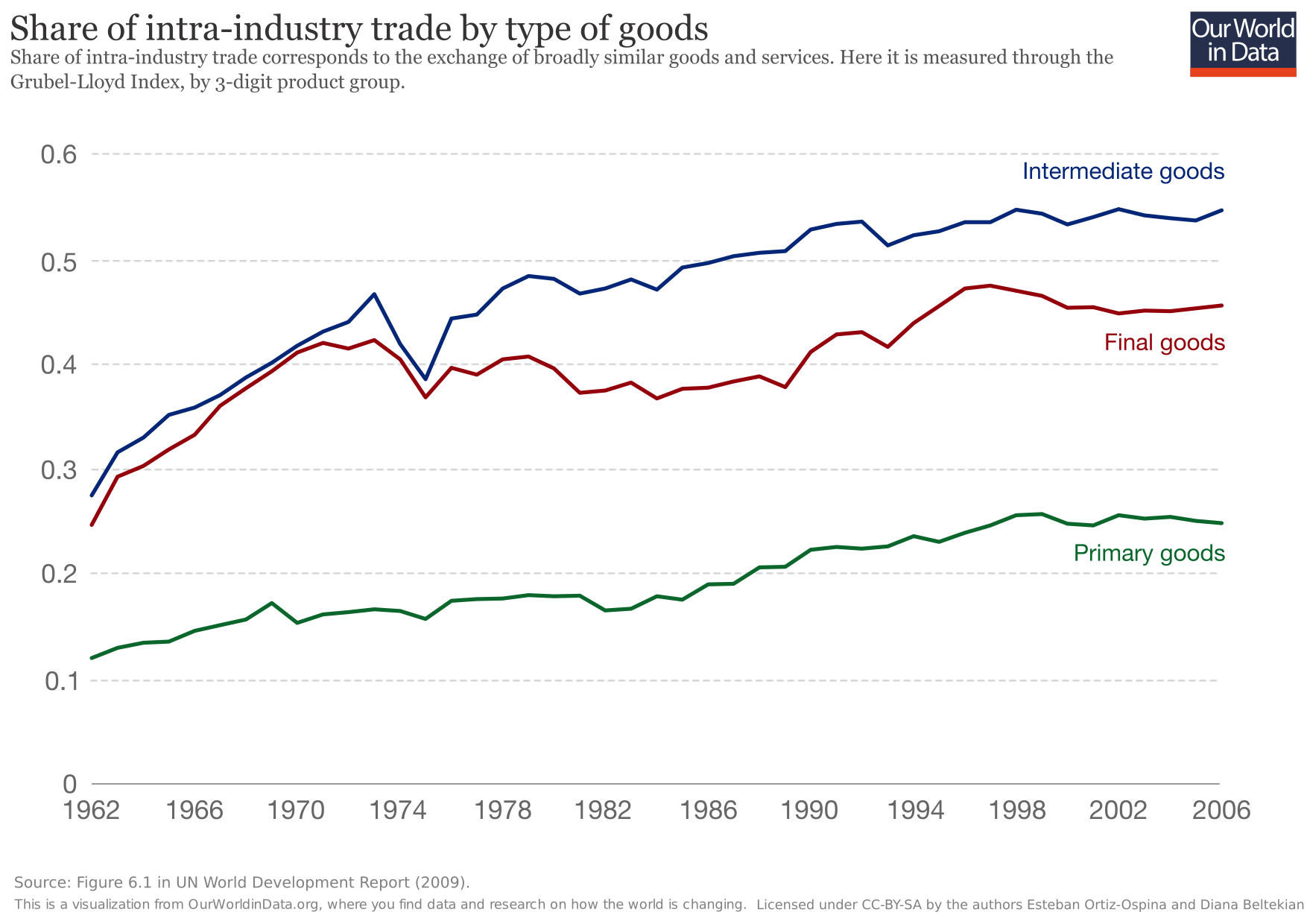

The first wave of globalization was characterized by inter-industry trade. This means that countries exported goods that were very different from what they imported – England exchanged machines for Australian wool and Indian tea. As transaction costs went down, this changed. In the second wave of globalization, we are seeing a rise in intra -industry trade (i.e. the exchange of broadly similar goods and services is becoming more and more common). France, for example, now both imports and exports machines to and from Germany.

The following visualization, from the UN World Development Report (2009) , plots the fraction of total world trade that is accounted for by intra-industry trade, by type of goods. As we can see, intra-industry trade has been going up for primary, intermediate, and final goods.

This pattern of trade is important because the scope for specialization increases if countries are able to exchange intermediate goods (e.g. auto parts) for related final goods (e.g. cars).

Trade and trade partners by country

Above, we examined the broad global trends over the last two centuries. Let's now examine country-level trends over this long and dynamic period.

This chart plots estimates of the value of trade in goods, relative to total economic activity (i.e. export-to-GDP ratios).

These historical estimates obviously come with a large margin of error (in the measurement section below we discuss the data limitations); yet they offer an interesting perspective.

You can edit the countries and regions selected. Each country tells a different story. 7

In the next chart we plot, country by country, the regional breakdown of exports. India is shown by default, but you can edit the countries and regions shown.

When switching to displaying relative values under ‘Settings’, we see the proportional contribution of purchases from each region. For example, we see that more than a third of Indian exports went to Asian countries in recent decades.

This gives us an interesting perspective on the changing nature of trade partnerships. In India, we see the rising importance of trade with Africa—a pattern that we discuss in more detail below .

Trade around the world today

How much do countries trade, trade openness around the world.

The metric trade as a share of GDP gives us an idea of global integration by capturing all incoming and outgoing transactions of a country.

The charts shows that countries differ a lot in the extent to which they engage in trade. Trade, for example, is much less important to the US economy than for other rich countries.

If you press the play button on the map, you can see changes over time. This reveals that, despite the great variation between countries, there is a common trend: over the last couple of decades trade openness has gone up in most countries.

Exports and imports in real dollars

Expressing the value of trade as a share of GDP tells us the importance of trade in relation to the size of economic activity. Let's now take a look at trade in monetary terms – this tells us the importance of trade in absolute, rather than relative terms.

The chart shows the value of exports (goods plus services) in dollars, country by country.

The main takeaway here is that the trend towards more trade is more pronounced than in the charts showing shares of GDP. This is not surprising: most countries today produce more than a couple of decades ago , and at the same time they trade more of what they produce. 8

What do countries trade?

Trade in goods vs. trade in services.

Trade transactions include goods (tangible products that are physically shipped across borders by road, rail, water, or air) and services (intangible commodities, such as tourism, financial services, and legal advice).

Many traded services make merchandise trade easier or cheaper—for example, shipping services, or insurance and financial services.

Trade in goods has been happening for millennia , while trade in services is a relatively recent phenomenon.

In some countries services are today an important driver of trade: in the UK services account for around half of all exports; and in the Bahamas, almost all exports are services.

In other countries, such as Nigeria and Venezuela, services account for a small share of total exports.

Globally, trade in goods accounts for the majority of trade transactions. But as this chart shows, the share of services in total global exports has slightly increased in recent decades. 9

How are trade partnerships changing?

Bilateral trade is becoming increasingly common.

If we consider all pairs of countries that engage in trade around the world, we find that in the majority of cases, there is a bilateral relationship today: most countries that export goods to a country also import goods from the same country.

The interactive visualization shows this. 10 In the chart, all possible country pairs are partitioned into three categories: the top portion represents the fraction of country pairs that do not trade with one another; the middle portion represents those that trade in both directions (they export to one another); and the bottom portion represents those that trade in one direction only (one country imports from, but does not export to, the other country).

As we can see, bilateral trade is becoming increasingly common (the middle portion has grown substantially). However, many countries still do not trade with each other at all.

South-South trade is becoming increasingly important

The next visualization here shows the share of world merchandise trade that corresponds to exchanges between today's rich countries and the rest of the world.

The 'rich countries' in this chart are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom and the United States. 'Non-rich countries' are all the other countries in the world.

As we can see, up until the Second World War, the majority of trade transactions involved exchanges between this small group of rich countries. But this has changed quickly over the last couple of decades, and today, trade between non-rich countries is just as important as trade between rich countries.

In the past two decades, China has been a key driver of this dynamic: the UN Human Development Report (2013) estimates that between 1992 and 2011, China's trade with Sub-Saharan Africa rose from $1 billion to more than $140 billion. 11

The majority of preferential trade agreements are between emerging economies

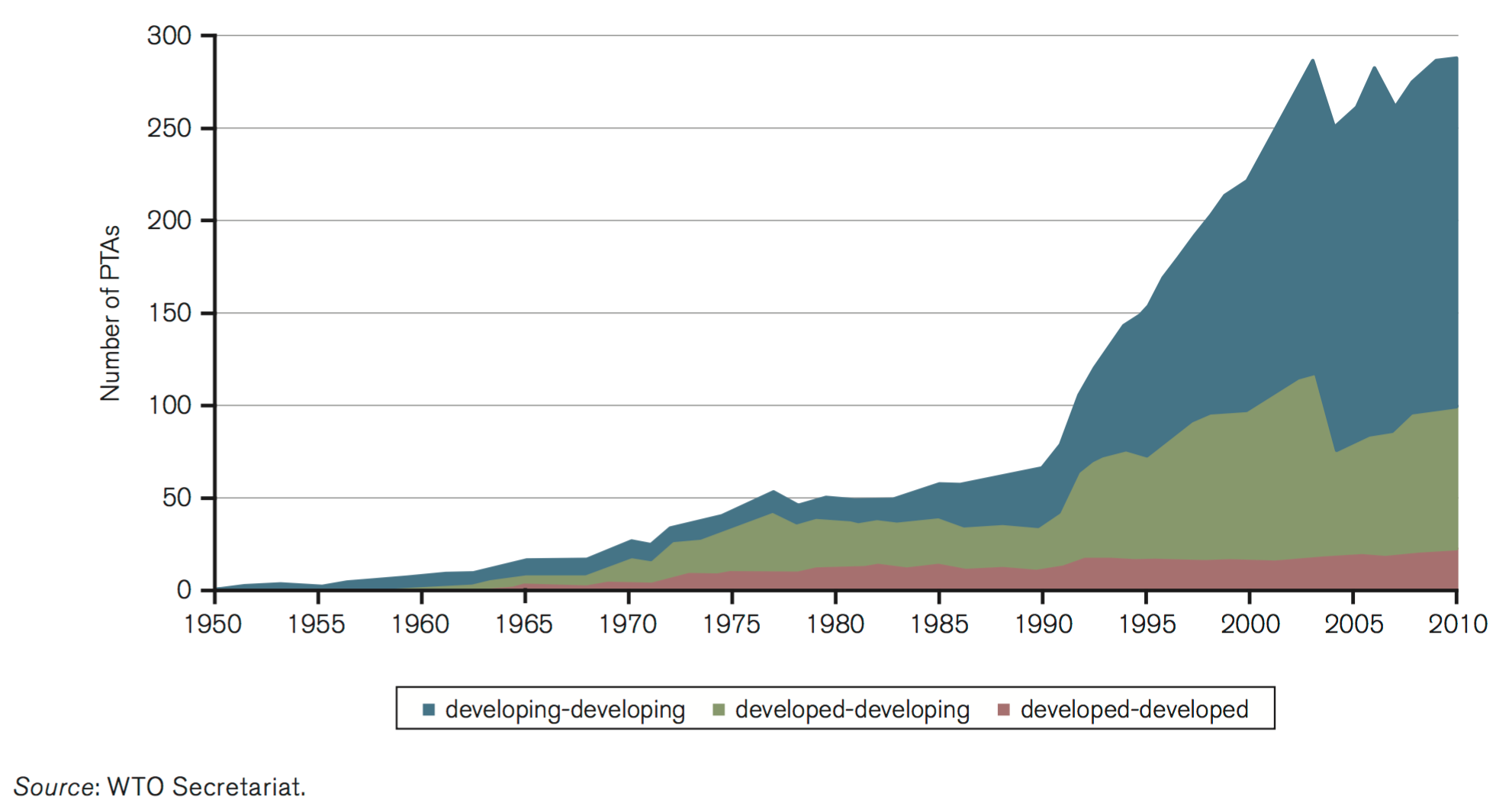

The last few decades have not only seen an increase in the volume of international trade, but also an increase in the number of preferential trade agreements through which exchanges take place. A preferential trade agreement is a trade pact that reduces tariffs between the participating countries for certain products.

The visualization here shows the evolution of the cumulative number of preferential trade agreements in force worldwide, according to the World Trade Organization (WTO). These numbers include notified and non-notified preferential agreements (the source reports that only about two-thirds of the agreements currently in force have been notified to the WTO) and are disaggregated by country groups.

This figure shows the increasingly important role of trade between developing countries (South-South trade), vis-a-vis trade between developed and developing countries (North-South trade). In the late 1970s, North-South agreements accounted for more than half of all agreements – in 2010, they accounted for about one-quarter. Today, the majority of preferential trade agreements are between developing economies.

Trading patterns have been changing quickly in middle-income countries

An important change in the composition of exported goods in these countries has accompanied the increase in trade among emerging economies over the last half century.

The next visualization plots the share of food exports in each country's total exported merchandise. These figures, produced by the World Bank, correspond to the Standard International Trade Classification, in which 'food' includes, among other goods, live animals, beverages, tobacco, coffee, oils, and fats.

Two points stand out. First, the relative importance of food exports has substantially decreased in most countries since the 1960s (although globally, it has gone up slightly more recently). Second, this decrease has been largest in middle-income countries, particularly in Latin America.

Regarding levels, as one would expect, in high-income countries, food still accounts for a much smaller share of merchandise exports than in most low- and middle-income-countries.

Trade generates efficiency gains

The raw correlation between trade and growth.

Over the last couple of centuries, the world economy has experienced sustained positive economic growth , and over the same period, this process of economic growth has been accompanied by even faster growth in global trade .

In a similar way, if we look at country-level data from the last half century we find that there is also a correlation between economic growth and trade: countries with higher rates of GDP growth also tend to have higher rates of growth in trade as a share of output. This basic correlation is shown in the chart here, where we plot the average annual change in real GDP per capita, against growth in trade (average annual change in value of exports as a share of GDP). 12

Is this statistical association between economic output and trade causal?

Among the potential growth-enhancing factors that may come from greater global economic integration are: competition (firms that fail to adopt new technologies and cut costs are more likely to fail and be replaced by more dynamic firms); economies of scale (firms that can export to the world face larger demand, and under the right conditions, they can operate at larger scales where the price per unit of product is lower); learning and innovation (firms that trade gain more experience and exposure to develop and adopt technologies and industry standards from foreign competitors). 13

Are these mechanisms supported by the data? Let's take a look at the available empirical evidence.

Evidence from cross-country differences in trade, growth, and productivity

When it comes to academic studies estimating the impact of trade on GDP growth, the most cited paper is Frankel and Romer (1999). 14

In this study, Frankel and Romer used geography as a proxy for trade to estimate the impact of trade on growth. This is a classic example of the so-called instrumental variables approach . The idea is that a country's geography is fixed, and mainly affects national income through trade. So if we observe that a country's distance from other countries is a powerful predictor of economic growth (after accounting for other characteristics), then the conclusion is drawn that it must be because trade has an effect on economic growth. Following this logic, Frankel and Romer find evidence of a strong impact of trade on economic growth.

Other papers have applied the same approach to richer cross-country data, and they have found similar results. A key example is Alcalá and Ciccone (2004). 15

This body of evidence suggests trade is indeed one of the factors driving national average incomes (GDP per capita) and macroeconomic productivity (GDP per worker) over the long run. 16

Evidence from changes in labor productivity at the firm level

If trade is causally linked to economic growth, we would expect that trade liberalization episodes also lead to firms becoming more productive in the medium and even short run. There is evidence suggesting this is often the case.

Pavcnik (2002) examined the effects of liberalized trade on plant productivity in the case of Chile, during the late 1970s and early 1980s. She found a positive impact on firm productivity in the import-competing sector. She also found evidence of aggregate productivity improvements from the reshuffling of resources and output from less to more efficient producers. 17

Bloom, Draca, and Van Reenen (2016) examined the impact of rising Chinese import competition on European firms over the period 1996-2007 and obtained similar results. They found that innovation increased more in those firms most affected by Chinese imports. They also found evidence of efficiency gains through two related channels: innovation increased and new existing technologies were adopted within firms, and aggregate productivity also increased because employment was reallocated towards more technologically advanced firms. 18

Trade does not only increase efficiency gains

Overall, the available evidence suggests that trade liberalization does improve economic efficiency. This evidence comes from different political and economic contexts and includes both micro and macro measures of efficiency.

This result is important because it shows that there are gains from trade. But of course, efficiency is not the only relevant consideration here. As we discuss in a companion article , the efficiency gains from trade are not generally equally shared by everyone. The evidence from the impact of trade on firm productivity confirms this: "reshuffling workers from less to more efficient producers" means closing down some jobs in some places. Because distributional concerns are real it is important to promote public policies – such as unemployment benefits and other safety-net programs – that help redistribute the gains from trade.

Trade has distributional consequences

The conceptual link between trade and household welfare.

When a country opens up to trade, the demand and supply of goods and services in the economy shift. As a consequence, local markets respond, and prices change. This has an impact on households, both as consumers and as wage earners.

The implication is that trade has an impact on everyone. It's not the case that the effects are restricted to workers from industries in the trade sector; or to consumers who buy imported goods. The effects of trade extend to everyone because markets are interlinked, so imports and exports have knock-on effects on all prices in the economy, including those in non-traded sectors.

Economists usually distinguish between "general equilibrium consumption effects" (i.e. changes in consumption that arise from the fact that trade affects the prices of non-traded goods relative to traded goods) and "general equilibrium income effects" (i.e. changes in wages that arise from the fact that trade has an impact on the demand for specific types of workers, who could be employed in both the traded and non-traded sectors).

Considering all these complex interrelations, it's not surprising that economic theories predict that not everyone will benefit from international trade in the same way. The distribution of the gains from trade depends on what different groups of people consume, and which types of jobs they have, or could have. 19

The link between trade, jobs and wages

Evidence from chinese imports and their impact on factory workers in the us.

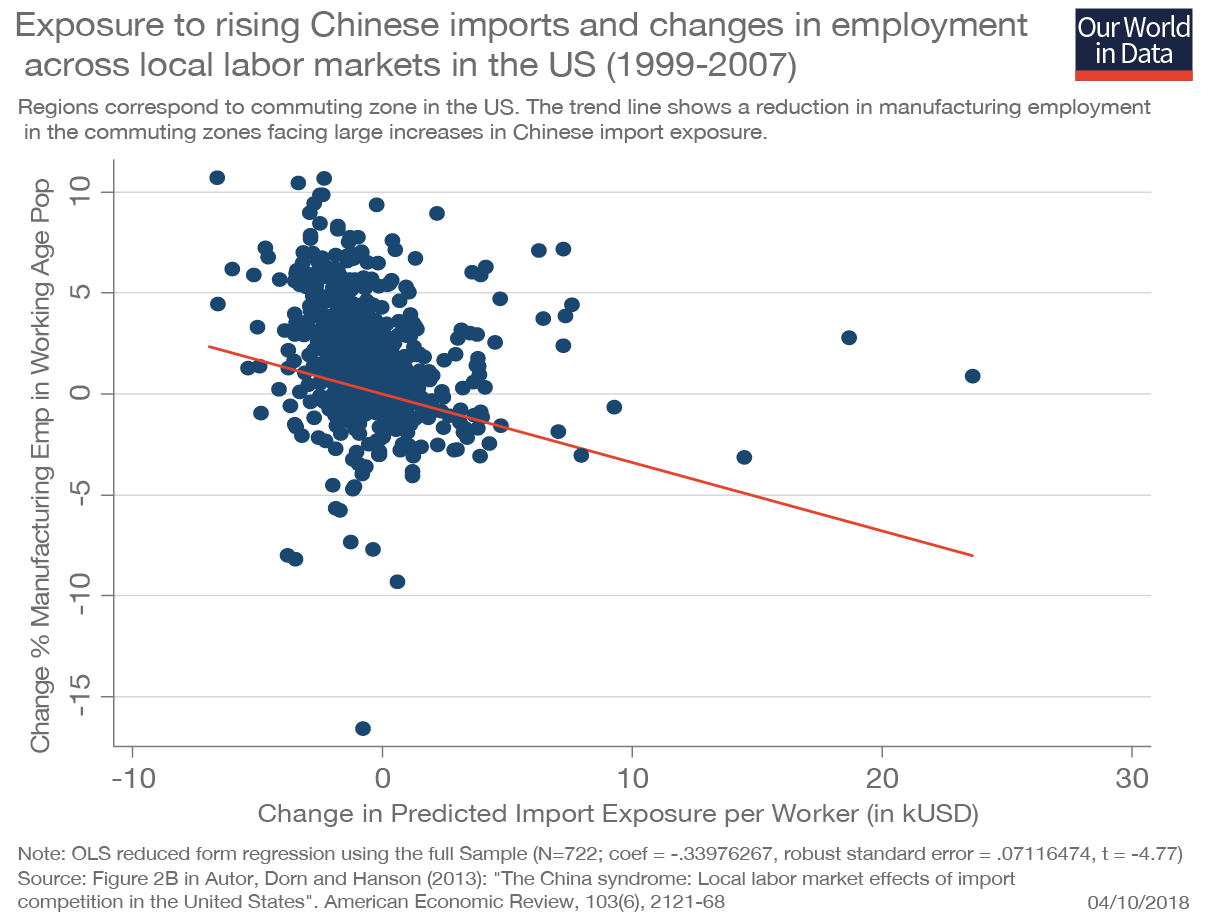

The most famous study looking at this question is Autor, Dorn and Hanson (2013): "The China syndrome: Local labor market effects of import competition in the United States". 20

In this paper, Autor and coauthors examined how local labor markets changed in the parts of the country most exposed to Chinese competition. They found that rising exposure increased unemployment, lowered labor force participation, and reduced wages. Additionally, they found that claims for unemployment and healthcare benefits also increased in more trade-exposed labor markets.

The visualization here is one of the key charts from their paper. It's a scatter plot of cross-regional exposure to rising imports, against changes in employment. Each dot is a small region (a 'commuting zone' to be precise). The vertical position of the dots represents the percent change in manufacturing employment for the working-age population, and the horizontal position represents the predicted exposure to rising imports (exposure varies across regions depending on the local weight of different industries).

The trend line in this chart shows a negative relationship: more exposure goes along with less employment. There are large deviations from the trend (there are some low-exposure regions with big negative changes in employment); but the paper provides more sophisticated regressions and robustness checks, and finds that this relationship is statistically significant.

This result is important because it shows that the labor market adjustments were large. Many workers and communities were affected over a long period of time. 21

But it's also important to keep in mind that Autor and colleagues are only giving us a partial perspective on the total effect of trade on employment. In particular, comparing changes in employment at the regional level misses the fact that firms operate in multiple regions and industries at the same time. Indeed, Ildikó Magyari found evidence suggesting the Chinese trade shock provided incentives for US firms to diversify and reorganize production. 22

So companies that outsourced jobs to China often ended up closing some lines of business, but at the same time expanded other lines elsewhere in the US. This means that job losses in some regions subsidized new jobs in other parts of the country.

On the whole, Magyari finds that although Chinese imports may have reduced employment within some establishments, these losses were more than offset by gains in employment within the same firms in other places. This is no consolation to people who lost their jobs. But it is necessary to add this perspective to the simplistic story of "trade with China is bad for US workers".

Evidence from the expansion of trade in India and the impact on poverty reductions

Another important paper in this field is Topalova (2010): "Factor immobility and regional impacts of trade liberalization: Evidence on poverty from India". 23

In this paper, Topalova examines the impact of trade liberalization on poverty across different regions in India, using the sudden and extensive change in India's trade policy in 1991. She finds that rural regions that were more exposed to liberalization experienced a slower decline in poverty and lower consumption growth.

Analyzing the mechanisms underlying this effect, Topalova finds that liberalization had a stronger negative impact among the least geographically mobile at the bottom of the income distribution and in places where labor laws deterred workers from reallocating across sectors.

The evidence from India shows that (i) discussions that only look at "winners" in poor countries and "losers" in rich countries miss the point that the gains from trade are unequally distributed within both sets of countries; and (ii) context-specific factors, like worker mobility across sectors and geographic regions, are crucial to understand the impact of trade on incomes.

Evidence from other studies

- Donaldson (2018) uses archival data from colonial India to estimate the impact of India’s vast railroad network. He finds railroads increased trade, and in doing so they increased real incomes (and reduced income volatility). 24

- Porto (2006) looks at the distributional effects of Mercosur on Argentine families, and finds this regional trade agreement led to benefits across the entire income distribution. He finds the effect was progressive: poor households gained more than middle-income households because prior to the reform, trade protection benefitted the rich disproportionately. 25

- Trefler (2004) looks at the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement and finds there was a group who bore "adjustment costs" (displaced workers and struggling plants) and a group who enjoyed "long-run gains" (consumers and efficient plants). 26

The link between trade and the cost of living

The fact that trade negatively affects labor market opportunities for specific groups of people does not necessarily imply that trade has a negative aggregate effect on household welfare. This is because, while trade affects wages and employment, it also affects the prices of consumption goods. So households are affected both as consumers and as wage earners.

Most studies focus on the earnings channel and try to approximate the impact of trade on welfare by looking at how much wages can buy, using as a reference the changing prices of a fixed basket of goods.

This approach is problematic because it fails to consider welfare gains from increased product variety, and obscures complicated distributional issues such as the fact that poor and rich individuals consume different baskets so they benefit differently from changes in relative prices. 27

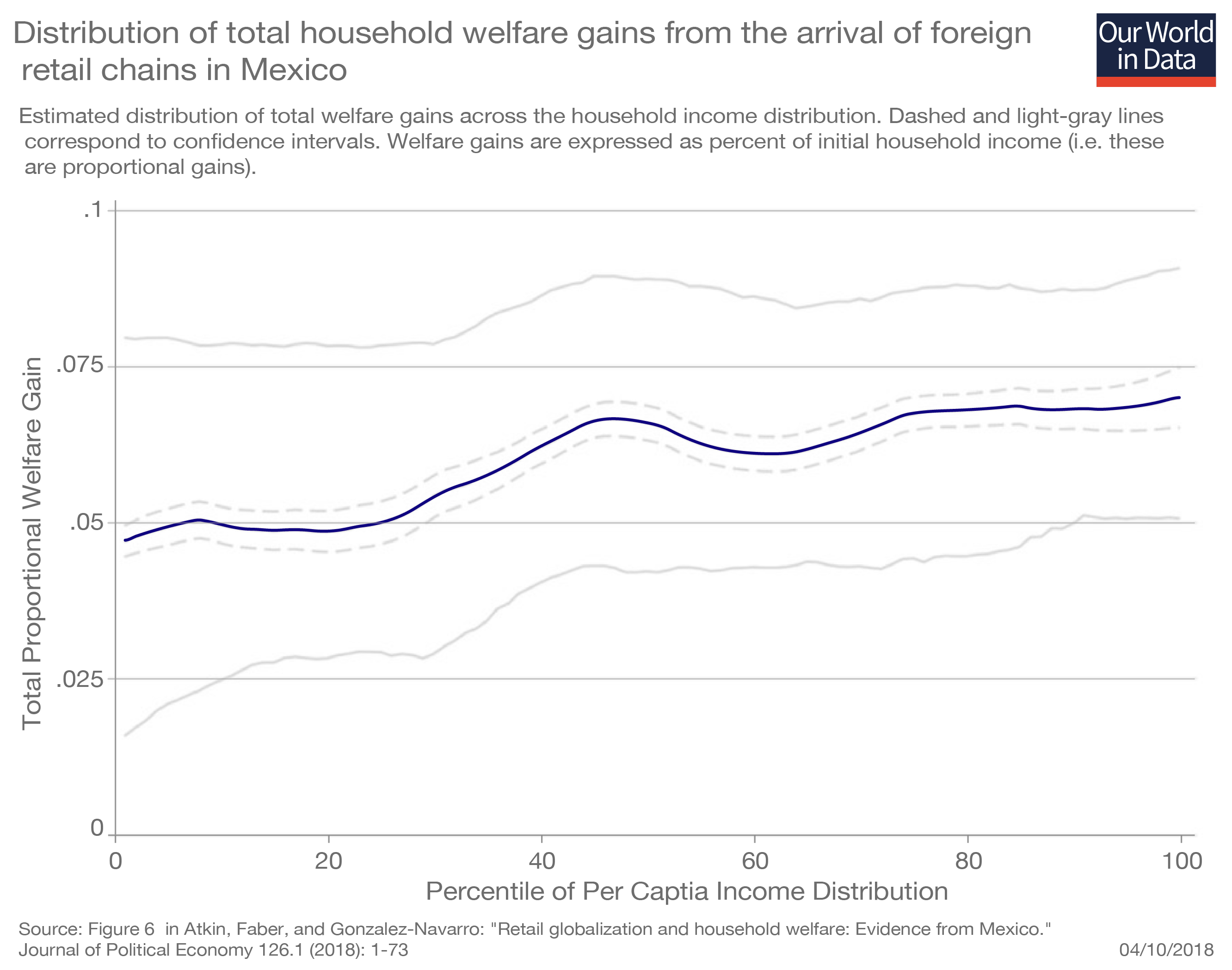

Ideally, studies looking at the impact of trade on household welfare should rely on fine-grained data on prices, consumption, and earnings. This is the approach followed in Atkin, Faber, and Gonzalez-Navarro (2018): "Retail globalization and household welfare: Evidence from Mexico". 28

Atkin and coauthors use a uniquely rich dataset from Mexico, and find that the arrival of global retail chains led to reductions in the incomes of traditional retail sector workers, but had little impact on average municipality-level incomes or employment; and led to lower costs of living for both rich and poor households.

The chart here shows the estimated distribution of total welfare gains across the household income distribution (the light-gray lines correspond to confidence intervals). These are proportional gains expressed as a percent of initial household income.

As we can see, there is a net positive welfare effect across all income groups; but these improvements in welfare are regressive, in the sense that richer households gain proportionally more (about 7.5 percent gain compared to 5 percent). 29

Evidence from other countries confirms this is not an isolated case – the expenditure channel really seems to be an important and understudied source of household welfare. Giuseppe Berlingieri, Holger Breinlich, Swati Dhingra, for example, investigated the consumer benefits from trade agreements implemented by the EU between 1993 and 2013; and they found that these trade agreements increased the quality of available products, which translated into a cumulative reduction in consumer prices equivalent to savings of €24 billion per year for EU consumers. 30

Implications of trade’s distributional effects

The available evidence shows that, for some groups of people, trade has a negative effect on wages and employment opportunities; at the same time, it has a large positive effect via lower consumer prices and increased product availability.

Two points are worth emphasizing.

For some households, the net effect is positive. But for some households that's not the case. In particular, workers who lose their jobs can be affected for extended periods of time, so the positive effect via lower prices is not enough to compensate them for the reduction in earnings.

On the whole, if we aggregate changes in welfare across households, the net effect is usually positive. But this is hardly a consolation for the worse off.

This highlights a complex reality: There are aggregate gains from trade , but there are also real distributional concerns. Even if trade is not a major driver of income inequalities , it's important to keep in mind that public policies, such as unemployment benefits and other safety-net programs, can and should help redistribute the gains from trade.

Explaining trade patterns: Theory and Evidence

Comparative advantage, theory: what is 'comparative advantage' and why does it matter to understand trade.

In economic theory, the 'economic cost' – or the 'opportunity cost' – of producing a good is the value of everything you need to give up in order to produce that good.

Economic costs include physical inputs (the value of the stuff you use to produce the good), plus forgone opportunities (when you allocate scarce resources to a task, you give up alternative uses of those resources).

A country or a person is said to have a 'comparative advantage' if it can produce something at a lower opportunity cost than its trade partners.

The forgone opportunities of production are key to understanding this concept. It is precisely this that distinguishes absolute advantage from comparative advantage.

To see the difference between comparative and absolute advantage, consider a commercial aviation pilot and a baker. Suppose the pilot is an excellent chef, and she can bake just as well, or even better than the baker. In this case, the pilot has an absolute advantage in both tasks. Yet the baker probably has a comparative advantage in baking, because the opportunity cost of baking is much higher for the pilot.

The freely available economics textbook The Economy: Economics for a Changing World explains this as follows: "A person or country has comparative advantage in the production of a particular good, if the cost of producing an additional unit of that good relative to the cost of producing another good is lower than another person or country’s cost to produce the same two goods."

At the individual level, comparative advantage explains why you might want to delegate tasks to someone else, even if you can do those tasks better and faster than them. This may sound counterintuitive, but it is not: If you are good at many things, it means that investing time in one task has a high opportunity cost, because you are not doing the other amazing things you could be doing with your time and resources. So, at least from an efficiency point of view, you should specialize on what you are best at, and delegate the rest.

The same logic applies to countries. Broadly speaking, the principle of comparative advantage postulates that all nations can gain from trade if each specializes in producing what they are relatively more efficient at producing, and imports the rest: “do what you do best, import the rest”. 31

In countries with a relative abundance of certain factors of production, the theory of comparative advantage predicts that they will export goods that rely heavily upon those factors: a country typically has a comparative advantage in those goods that use its abundant resources. Colombia exports bananas to Europe because it has comparatively abundant tropical weather.

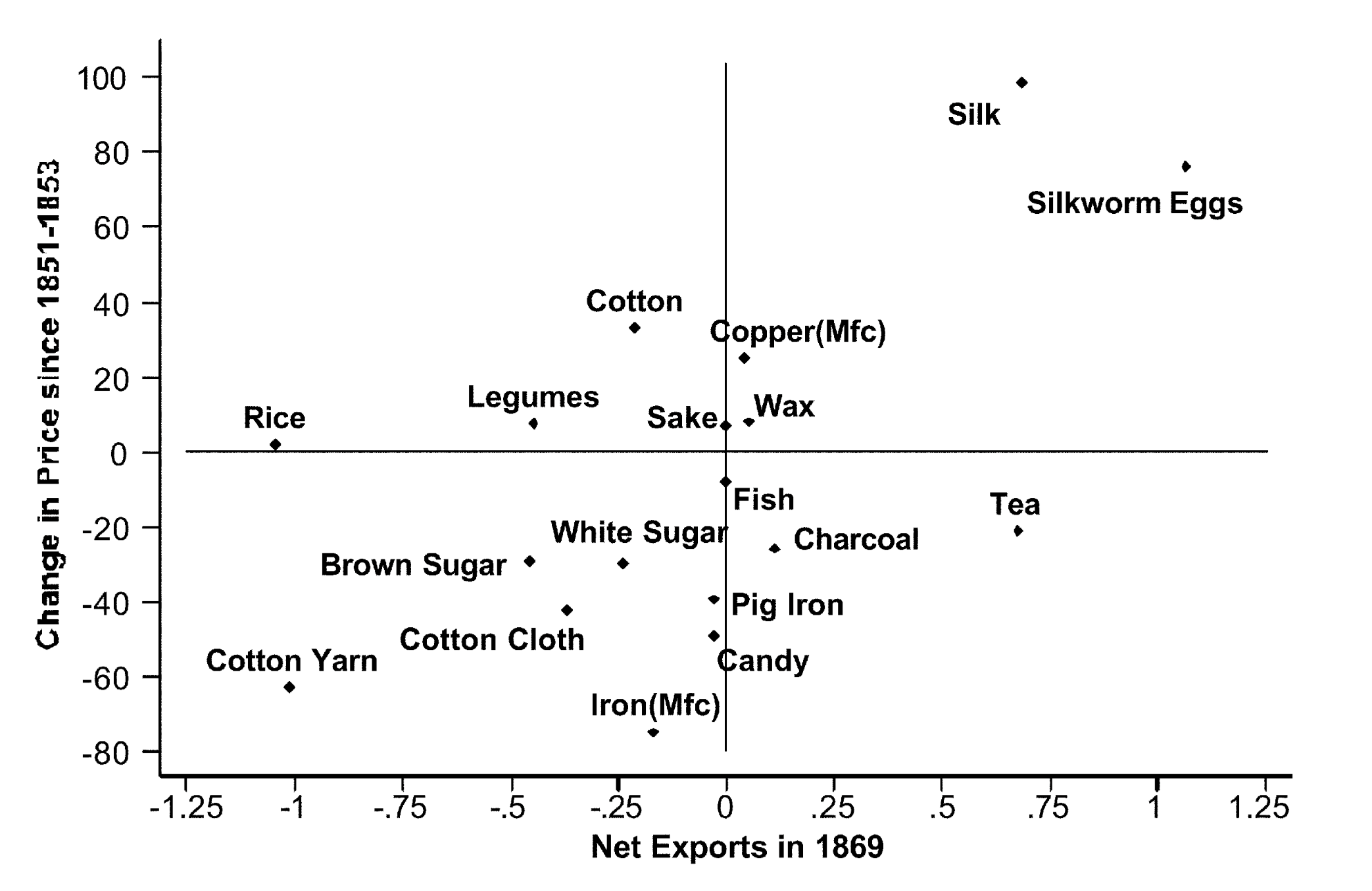

Is there empirical support for comparative-advantage theories of trade?

The empirical evidence suggests that the principle of comparative advantage does help explain trade patterns. Bernhofen and Brown (2004) 32 , for instance, provide evidence using the experience of Japan. Specifically, they exploit Japan’s dramatic nineteenth-century move from a state of near complete isolation to wide trade openness.

The graph here shows the price changes of the key tradable goods after the opening up to trade. It presents a scatter diagram of the net exports in 1869 graphed in relation to the change in prices from 1851–53 to 1869. As we can see, this is consistent with the theory: after opening to trade, the relative prices of major exports such as silk increased (Japan exported what was cheap for them to produce and which was valuable abroad), while the relative price of imports such as sugar declined (they imported what was relatively more difficult for them to produce, but was cheap abroad).

Trade diminishes with distance

The resistance that geography imposes on trade has long been studied in the empirical economics literature – and the main conclusion is that trade intensity is strongly linked to geographic distance.

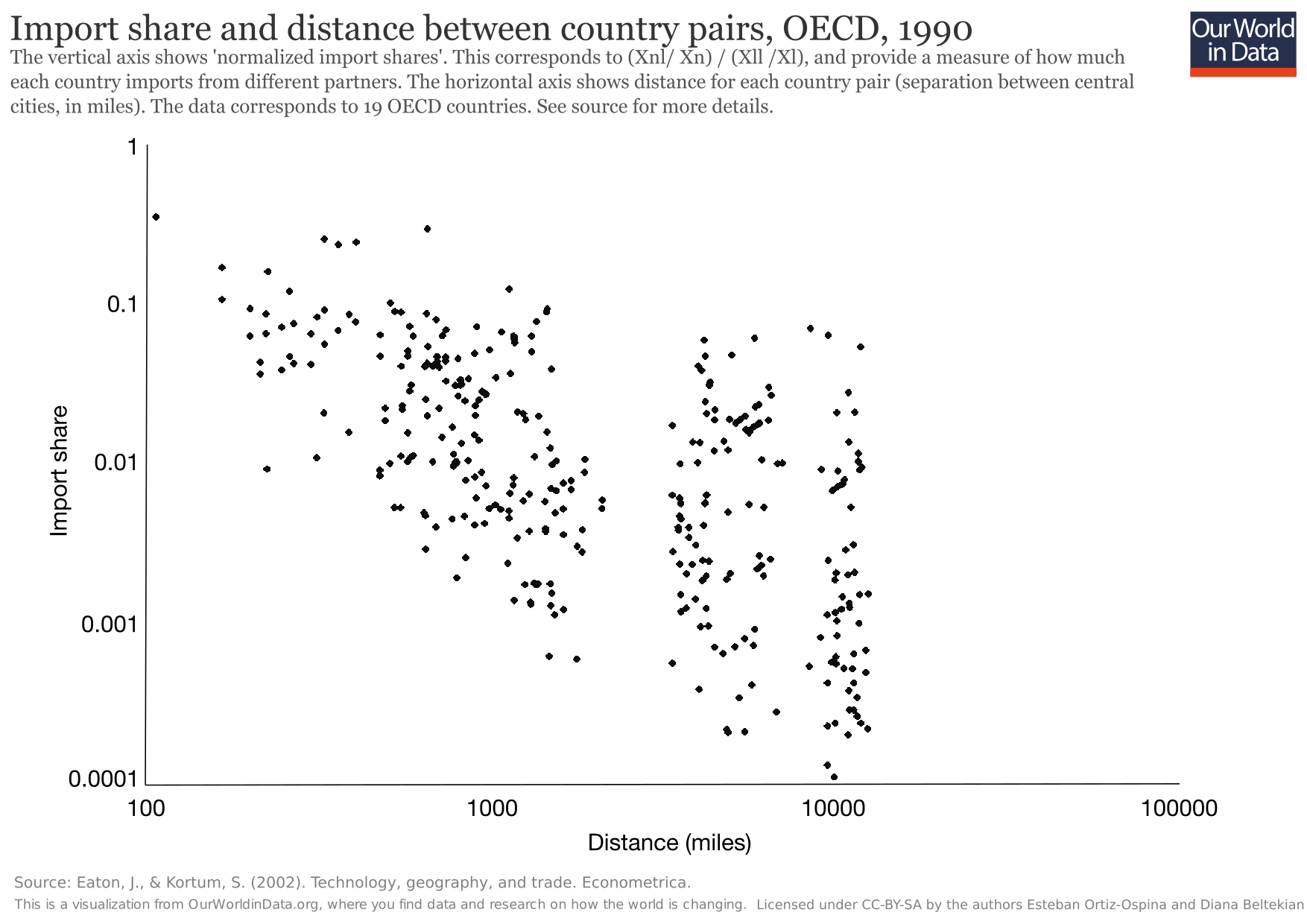

The visualization, from Eaton and Kortum (2002), graphs 'normalized import shares' against distance. 33 Each dot represents a country pair from a set of 19 OECD countries, and both the vertical and horizontal axes are expressed on logarithmic scales.

The 'normalized import shares' in the vertical axis provide a measure of how much each country imports from different partners (see the paper for details on how this is calculated and normalized), while the distance in the horizontal axis corresponds to the distance between central cities in each country (see the paper and references therein for details on the list of cities). As we can see, there is a strong negative relationship. Trade diminishes with distance. Through econometric modeling, the paper shows that this relationship is not just a correlation driven by other factors: their findings suggest that distance imposes a significant barrier to trade.

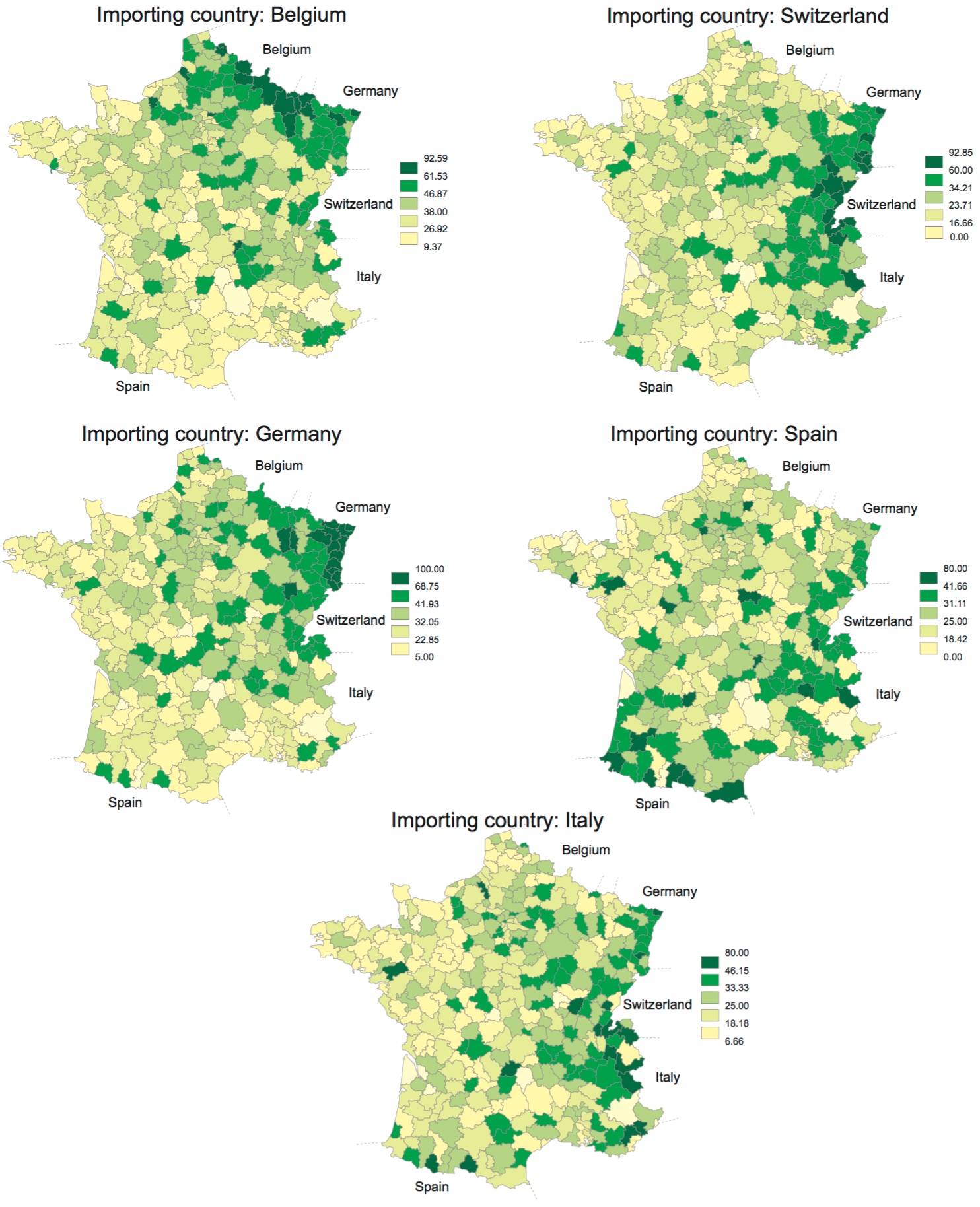

The fact that trade diminishes with distance is also corroborated by data on trade intensity within countries. The visualization here shows, through a series of maps, the geographic distribution of French firms that export to France's neighboring countries. The colors reflect the percentage of firms that export to each specific country.

As we can see, the share of firms exporting to each of the corresponding neighbors is the largest close to the border. The authors also show in the paper that this pattern holds for the value of individual-firm exports – trade value decreases with distance to the border.

Institutions

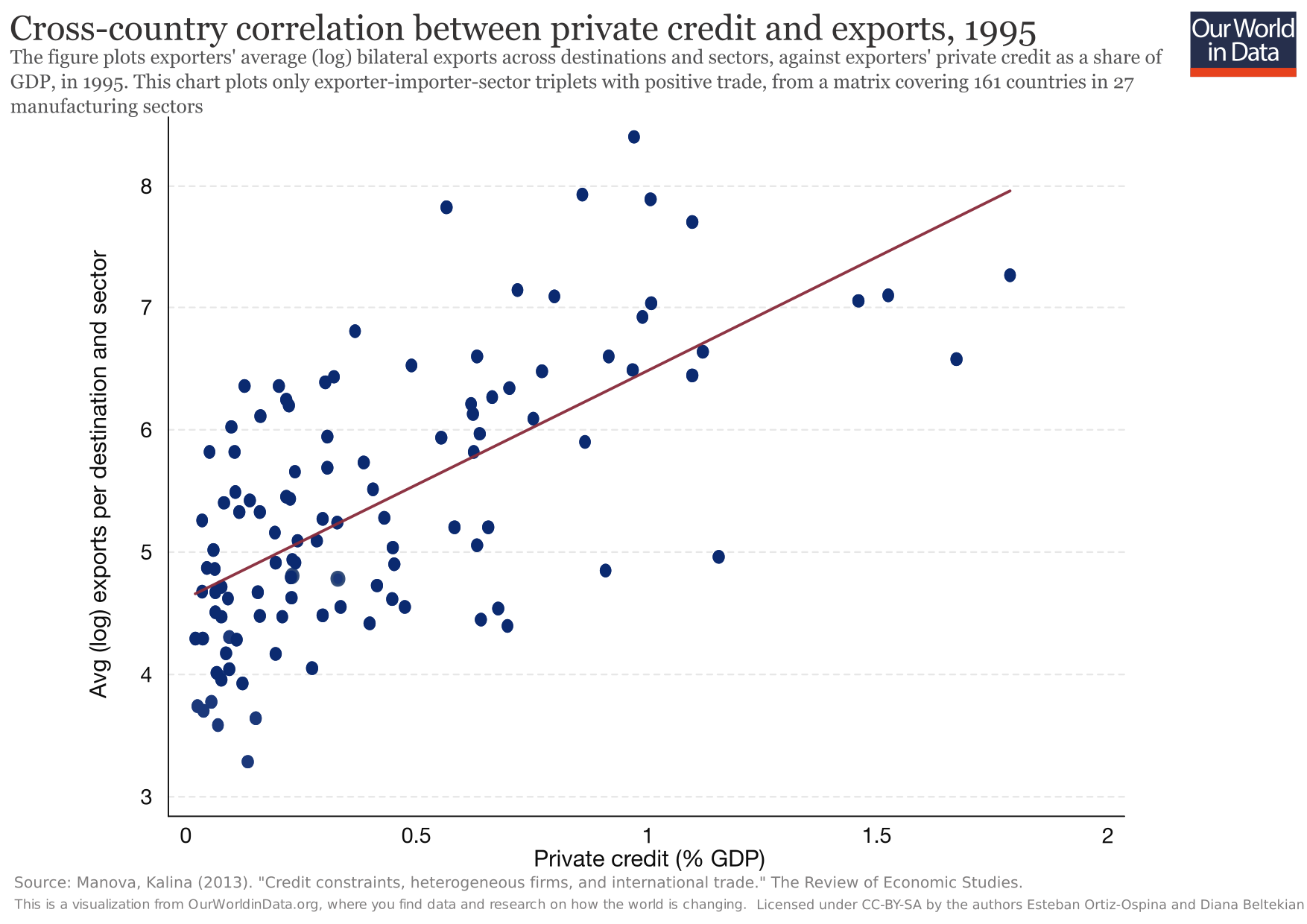

Conducting international trade requires both financial and non-financial institutions to support transactions. Some of these institutions are fairly obvious (e.g. law enforcement); but some are less obvious. For example, the evidence shows that producers in exporting countries often need credit in order to engage in trade.

The scatter plot, from Manova (2013), shows the correlation between levels in private credit (specifically exporters’ private credit as a share of GDP) and exports (average log bilateral exports across destinations and sectors). 35 As can be seen, financially developed economies – those with more dynamic private credit markets – typically outperform exporters with less evolved financial institutions.

Other studies have shown that country-specific institutions, like the knowledge of foreign languages, for instance, are also important to promote foreign relative to domestic trade. 36

Increasing returns to scale

The concept of comparative advantage predicts that if all countries had identical endowments and institutions, there would be little incentive for specialization because the opportunity cost of producing any good would be the same in every country.

So you may wonder: why is it then the case that in the last few years, we have seen such rapid growth in intra-industry trade between rich countries?

The increase in intra-industry between rich countries seems paradoxical under the light of comparative advantage because in recent decades we have seen convergence in key factors, such as human capital , across these countries.

The solution to the paradox is actually not very complicated: Comparative advantage is one, but not the only force driving incentives to specialization and trade.

Several economists, most notably Paul Krugman, have developed theories of trade in which trade is not due to differences between countries, but instead due to "increasing returns to scale" – an economic term used to denote a technology in which producing extra units of a good becomes cheaper if you operate at a larger scale.

The idea is that specialization allows countries to reap greater economies of scale (i.e. to reduce production costs by focusing on producing large quantities of specific products), so trade can be a good idea even if the countries do not differ in endowments, including culture and institutions.

These models of trade, often referred to as “New Trade Theory”, are helpful in explaining why in the last few years we have seen such rapid growth in two-way exchanges of goods within industries between developed nations.

In a much-cited paper, Evenett and Keller (2002) show that both factor endowments and increasing returns help explain production and trade patterns around the world. 37

You can learn more about New Trade Theory, and the empirical support behind it, in Paul Krugman's Nobel lecture .

Measurement and data quality

There are dozens of official sources of data on international trade, and if you compare these different sources, you will find that they do not agree with one another. Even if you focus on what seems to be the same indicator for the same year in the same country, discrepancies are large.

Such differences between sources can also be found in rich countries where statistical agencies tend to follow international reporting guidelines more closely.

There are also large bilateral discrepancies within sources: the value of goods that country A exports to country B can be more than the value of goods that country B imports from country A.

Here we explain how international trade data is collected and processed, and why there are such large discrepancies.

What data is available?

The data hubs from several large international organizations publish and maintain extensive cross-country datasets on international trade. Here's a list of the most important ones:

- World Bank Open Data

- WTO Statistics

- UN Comtrade

- UNCTAD World Integrated Trade Solutions

In addition to these sources, there are also many other academic projects that publish data on international trade. These projects tend to rely on data from one or more of the sources above, and they typically process and merge series in order to improve coverage and consistency. Three important sources are:

- The Correlates of War Project . 38

- The NBER-United Nations Trade Dataset Project .

- The CEPII Bilateral Trade and Gravity Data Project . 39

How large are the discrepancies between sources?

In the visualization here, we compare the data published by several of the sources listed above, country by country, from 1955 to today.

For each country, we exclude trade in services, and we focus only on estimates of the total value of exported goods, expressed as shares of GDP. 40

As this chart clearly shows, different data sources often tell very different stories. If you change the country or region shown you will see that this is true, to varying degrees, across all countries and years.

Constructing this chart was demanding. It required downloading trade data from many different sources, collecting the relevant series, and then standardizing them so that the units of measure and the geographical territories were consistent.

All series, except the two long-run series from CEPII and NBER-UN, were produced from data published by the sources in current US dollars and then converted to GDP shares using a unique source (World Bank).

So, if all series are in the same units (share of national GDP) and they measure the same thing (value of goods exported from one country to the rest of the world), what explains the differences?

Let's dig deeper to understand what's going on.

Why doesn't the data add up?

Differences in guidelines used by countries to record and report trade data.

Broadly speaking, there are two main approaches used to estimate international merchandise trade:

- The first approach relies on estimating trade from customs records , often complementing or correcting figures with data from enterprise surveys and administrative records associated with taxation. The main manual providing guidelines for this approach is the International Merchandise Trade Statistics Manual (IMTS).

- The second approach relies on estimating trade from macroeconomic data , typically National Accounts . The main manual providing guidelines for this approach is the Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual (BPM6), which was drafted in parallel with the 2008 System of National Accounts of the United Nations (SNA 2008). The idea behind this approach is to record changes in economic ownership. 41

Under these two approaches, it is common to distinguish between 'traded merchandise' and 'traded goods'. The distinction is often made because goods simply being transported through a country (i.e., goods in transit) are not considered to change a country's stock of material resources and are hence often excluded from the more narrow concept of 'merchandise trade'.

Also, adding to the complexity, countries often rely on measurement protocols developed alongside approaches and concepts that are not perfectly compatible to begin with. In Europe, for example, countries use the 'Compilers guide on European statistics on international trade in goods'.

Measurement error and other inconsistencies

Even when two sources rely on the same broad accounting approach, discrepancies arise because countries fail to adhere perfectly to the protocols.

In theory, for example, the exports of country A to country B should mirror the imports of country B from country A. But in practice this is rarely the case because of differences in valuation. According to the BPM6, imports, and exports should be recorded in the balance of payments accounts on a ' free on board (FOB) basis', which means using prices that include all charges up to placing the goods on board a ship at the port of departure. Yet many countries stick to FOB values only for exports, and use CIF values for imports (CIF stands for 'Cost, Insurance and Freight', and includes the costs of transportation). 42

The chart here gives you an idea of how large import-export asymmetries are. Shown are the differences between the value of goods that each country reports exporting to the US, and the value of goods that the US reports importing from the same countries. For example, for China, the figure in the chart corresponds to the “Value of merchandise imports in the US from China” minus the “Value of merchandise exports from China to the US”.

The differences in the chart here, which are both positive and negative, suggest that there is more going on than differences in FOB vs. CIF values. If all asymmetries were coming from FOB-CIF differences, then we should only see positive values in the chart (recall that, unlike FOB values, CIF values include the cost of transportation, so CIF values are larger).

What else may be going on here?

Another common source of measurement error relates to the inconsistent attribution of trade partners. An example is failure to follow the guidelines on how to treat goods passing through intermediary countries for processing or merchanting purposes. As global production chains become more complex, countries find it increasingly difficult to unambiguously establish the origin and final destination of merchandise, even when rules are established in the manuals. 43

And there are still more potential sources of discrepancies. For example differences in customs and tax regimes, and differences between "general" and "special" trade systems (i.e. differences between statistical territories and actual country borders, which do not often coincide because of things like 'custom free zones'). 44

Even when two sources have identical trade estimates, inconsistencies in published data can arise from differences in exchange rates. If a dataset reports cross-country trade data in US dollars, estimates will vary depending on the exchange rates used. Different exchange rates will lead to conflicting estimates, even if figures in local currency units are consistent.

A checklist for comparing sources

Asymmetries in international trade statistics are large and arise for a variety of reasons. These include conceptual inconsistencies across measurement standards and inconsistencies in the way countries apply agreed-upon protocols. Here's a checklist of issues to keep in mind when comparing sources.

- Differences in underlying records: is trade measured from National Accounts data rather than directly from custom or tax records?

- Differences in import and export valuations: are transactions valued at FOB or CIF prices?

- Inconsistent attribution of trade partners: how is the origin and final destination of merchandise established?

- Difference between 'goods' and 'merchandise': how are re-importing, re-exporting, and intermediary merchanting transactions recorded?

- Exchange rates: how are values converted from local currency units to the currency that allows international comparisons (most often the US-$)?

- Differences between 'general' and 'special' trade system: how is trade recorded for custom-free zones?

- Other issues: Time of recording, confidentiality policies, product classification, deliberate mis-invoicing for illicit purposes.

Many organizations producing trade data have long recognized these factors. Indeed, international organizations often incorporate corrections in an attempt to improve data quality.

The OECD's Balanced International Merchandise Trade Statistics , for example, uses its own approach to correct and reconcile international merchandise trade statistics. 45

The corrections applied in the OECD's 'balanced' series make this the best source for cross-country comparisons. However, this dataset has low coverage across countries, and it only goes back to 2011. This is an important obstacle since the complex adjustments introduced by the OECD imply we can't easily improve coverage by appending data from other sources. At Our World in Data we have chosen to rely on CEPII as the main source for exploring long-run changes in international trade, but we also rely on World Bank and OECD data for up-to-date cross-country comparisons.

There are two key lessons from all of this. The first lesson is that, for most users of trade data out there, there is no obvious way of choosing between sources. And the second lesson is that, because of statistical glitches, researchers and policymakers should always take analyses of trade data with a pinch of salt. For example, in a recent high-profile report , researchers attributed mismatches in bilateral trade data to illicit financial flows through trade mis-invoicing (or trade-based money laundering). As we show here, this interpretation of the data is not appropriate, since mismatches in the data can, and often do arise from measurement inconsistencies rather than malfeasance. 46

Hopefully, the discussion and checklist above can help researchers better interpret and choose between conflicting data sources.

Interactive charts on Trade and Globalization

The openness index, when calculated for the world as a whole, includes double-counting of transactions: When country A sells goods to country B, this shows up in the data both as an import (B imports from A) and as an export (A sells to B).

Indeed, if you compare the chart showing the global trade openness index and the chart showing global merchandise exports as a share of GDP , you find that the former is almost twice as large as the latter.

Why is the global openness index not exactly twice the value reported in the chart plotting global merchandise exports? There a three reasons.

First, the global openness index uses different sources. Second, the global openness index includes trade in goods and services, while merchandise exports include goods but not services. And third, the amount that country A reports exporting to country B does not usually match the amount that B reports importing from A.

We explore this in more detail in our measurement section below .

Klasing and Milionis (2014), one of the sources in the chart, published an additional set of estimates under an alternative specification. Similarly, for the period 1960-2015, the World Bank's World Development Indicators published an alternative set of estimates similar but not identical to those included from the Penn World Tables (9.1). You find all these alternative overlapping sources in this comparison chart .

Leonor Freire Costa, Nuno Palma, and Jaime Reis (2015) – The great escape? The contribution of the empire to Portugal's economic growth, 1500–1800 Leonor Freire Costa Nuno Palma Jaime Reis European Review of Economic History, Volume 19, Issue 1, 1 February 2015, Pages 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1093/ereh/heu019

Broadberry and O'Rourke (2010) - The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Europe: Volume 2, 1870 to the Present. Cambridge University Press.

Integration in the goods markets is measured here through the 'trade openness index', which is defined by the sum of exports and imports as a share of GDP. In our interactive chart you can explore trends in trade openness over this period for a selection of European countries.

Broadberry and O'Rourke (2010) - The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Europe: Volume 2, 1870 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. The graph depicts the “evolution of three indicators measuring integration in commodity, labor, and capital markets over the long run. Commodity market integration is measured by computing the ratio of exports to GDP. Labor market integration is measured by dividing the migratory turnover by population. Financial integration is measured using Feldstein–Horioka estimators of current account disconnectedness.”

We also have the same chart but showing imports .

We also have the same chart, but showing imports .

This interactive chart shows trade in services as a share of GDP across countries and regions.

This chart was inspired by a chart from Helpman, E., Melitz, M., & Rubinstein, Y. (2007). Estimating trade flows: Trading partners and trading volumes (No. w12927). National Bureau of Economic Research.

We also have the same data, but as a stacked-area chart .

There are different ways of capturing this correlation. I focus here on all countries with data over the period 1945-2014. You can find a similar chart using different data sources and time periods in Ventura, J. (2005). A global view of economic growth. Handbook of economic growth, 1, 1419-1497. Online here .

The textbook The Economy: Economics for a Changing World explains this in more detail.

Frankel, J. A., & Romer, D. H. (1999). Does trade cause growth? American Economic Review, 89(3), 379-399.

Alcalá, F., & Ciccone, A. (2004). Trade and productivity . The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(2), 613-646.

There are many papers that try to answer this specific question with macro data. For an overview of papers and methods see: Durlauf, S. N., Johnson, P. A., & Temple, J. R. (2005). Growth econometrics. Handbook of economic growth, 1, 555-677.

Pavcnik, N. (2002). Trade liberalization, exit, and productivity improvements: Evidence from Chilean plants . The Review of Economic Studies, 69(1), 245-276.

Bloom, N., Draca, M., & Van Reenen, J. (2016). Trade induced technical change? The impact of Chinese imports on innovation, IT and productivity. The Review of Economic Studies, 83(1), 87-117. Available online here .

You can read more about these economic concepts, and the related predictions from economic theory, in Chapter 18 of the textbook The Economy: Economics for a Changing World .

David, H., Dorn, D., & Hanson, G. H. (2013). The China syndrome: Local labor market effects of import competition in the United States . American Economic Review, 103(6), 2121-68.

It's important to mention here that the economist Jonathan Rothwell wrote a paper suggesting these findings are the result of a statistical illusion. Rothwell's critique received some attention from the media , but Autor and coauthors provided a reply , which I think successfully refutes this claim.

Magyari, I. (2017). Firm Reorganization, Chinese Imports, and US Manufacturing Employment . US Census Bureau, Center for Economic Studies.

Topalova, P. (2010). Factor immobility and regional impacts of trade liberalization: Evidence on poverty from India . American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(4), 1-41.

Donaldson, D. (2018). Railroads of the Raj: Estimating the impact of transportation infrastructure . American Economic Review, 108(4-5), 899-934.

Porto, G (2006). Using Survey Data to Assess the Distributional Effects of Trade Policy. Journal of International Economics 70 (2006) 140–160.

Trefler, D. (2004). The long and short of the Canada-US free trade agreement . American Economic Review, 94(4), 870-895.

See: (i) Feenstra, R. C., & Weinstein, D. E. (2017). Globalization, markups, and US welfare . Journal of Political Economy, 125(4), 1040-1074. (ii) Fajgelbaum, P. D., & Khandelwal, A. K. (2016). Measuring the unequal gains from trade . The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(3), 1113-1180.

Atkin, David, Benjamin Faber, and Marco Gonzalez-Navarro. "Retail globalization and household welfare: Evidence from Mexico." Journal of Political Economy 126.1 (2018): 1-73.

In the paper, Atkin and coauthors explore the reasons for this and find that the regressive nature of the distribution is mainly due to richer households placing higher weight on the product variety and shopping amenities on offer at these new foreign stores.

Berlingieri, G., Breinlich, H., & Dhingra, S. (2018). The Impact of Trade Agreements on Consumer Welfare—Evidence from the EU Common External Trade Policy. Journal of the European Economic Association.

Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson (1969) was once challenged by the mathematician Stanislaw Ulam: "Name me one proposition in all of the social sciences which is both true and non-trivial." It was several years later than he thought of the correct response: comparative advantage. "That it is logically true need not be argued before a mathematician; that is is not trivial is attested by the thousands of important and intelligent men who have never been able to grasp the doctrine for themselves or to believe it after it was explained to them."

(NB. This is an excerpt from https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/reser_e/cadv_e.htm)

Bernhofen, D., & Brown, J. (2004). A Direct Test of the Theory of Comparative Advantage: The Case of Japan. Journal of Political Economy, 112(1), 48-67. doi:1. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/379944 doi:1

Eaton, J., & Kortum, S. (2002). Technology, geography, and trade. Econometrica, 70(5), 1741-1779.

Crozet, M., & Koenig, P. (2010). Structural Gravity Equations with Intensive and Extensive Margins. The Canadian Journal of Economics / Revue Canadienne D'Economique, 43(1), 41-62. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40389555

Manova, Kalina. "Credit constraints, heterogeneous firms, and international trade." The Review of Economic Studies 80.2 (2013): 711-744.

Melitz, J. (2008). Language and foreign trade. European Economic Review, 52(4), 667-699.

Evenett, S. J., & Keller, W. (2002). On theories explaining the success of the gravity equation . Journal of Political Economy, 110(2), 281-316.

For more information on how the COW trade datasets were constructed see: (i) Barbieri, Katherine, and Omar M. G. Omar Keshk. 2016. Correlates of War Project Trade Data Set Codebook, Version 4.0. Available at http://correlatesofwar.org and (ii) Barbieri, Katherine, Omar M. G. Keshk, and Brian Pollins. 2009. TRADING DATA: Evaluating our Assumptions and Coding Rules. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 26(5): 471–491.

Further information on CEPII's methodology can be found in their working paper .

The chart includes series labeled by the sources as 'merchandise trade' and 'goods trade'. As we explain below, part of the asymmetries in trade data comes from the fact that, although 'merchandise' and 'goods' are equivalent in the dictionary, these two terms often measure related but different things.

For example, if there is no change in ownership (e.g. a firm exports goods to its factory in another country for processing, and then re-imports the processed goods) the manual says that statistical agencies should only record the net difference in value. You can find more details about this in an OECD Statistics Briefing .

This issue is actually also a source of disagreement between National Accounts data and customs data. You can read more about it in this report: Harrison, Anne (2013) FOB/CIF Issue in Merchandise Trade/Transport of Goods in BPM6 and the 2008 SNA, Twenty-Fifth Meeting of the IMF Committee on Balance of Payments Statistics, Washington, D.C .

Precisely because of the difficulty that arises when trying to establish the origin and final destination of merchandise, some sources distinguish between national and dyadic (i.e. 'directed') trade estimates.

For more details about general and special trade see the Eurostat glossary .

The OECD approach consists of four steps, which they describe as follows: "First, data are collected and organized, and imports are converted to FOB prices to match the valuation of exports. Secondly, data are adjusted for several specific large problems known to drive asymmetries. Presently these include “modular” adjustments for unallocated and confidential trade; for exports by Hong Kong, China; for Swiss non-monetary gold; and for clear-cut cases of product misclassifications. The list of modules is expected to grow over time. In the third step, adjusted data are balanced using a “Symmetry Index” that weights exports and imports. As the final step, the data are also converted to Classification of Products by Activity (CPA) products to better align with National Accounts statistics, such as in national Supply-Use tables." You can read more about it here . In addition to the OECD, other sources also use corrections. The IMF's DOTS dataset, for example, uses a 6 percent rule for converting import valuations (in CIF) into export values (in FOB). More information can be found in the IMF's (2018) working paper on 'New Estimates for Direction of Trade Statistics'.

For more details on this see Forstater, M. (2018) Illicit Financial Flows, Trade Misinvoicing, and Multinational Tax Avoidance: The Same or Different? , CGD Policy Paper 123.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

BibTeX citation

Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license . You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Globalization

Covering a wide range of distinct political, economic, and cultural trends, the term “globalization” remains crucial to contemporary political and academic debate. In contemporary popular discourse, globalization often functions as little more than a synonym for one or more of the following phenomena: the pursuit of classical liberal (or “free market”) policies in the world economy (“economic liberalization”), the growing dominance of western (or even American) forms of political, economic, and cultural life (“westernization” or “Americanization”), a global political order built on liberal notions of international law (the “global liberal order”), an ominous network of top-down rule by global elites (“globalism” or “global technocracy”), the proliferation of new information technologies (the “Internet Revolution”), as well as the notion that humanity stands at the threshold of realizing one single unified community in which major sources of social conflict have vanished (“global integration”). Globalization is a politically-contested phenomenon about which there are significant disagreements and struggles, with many nationalist and populist movements and leaders worldwide (including Turkey’s Recep Erdoğan, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, and former US President Donald Trump) pushing back against what they view as its unappealing features.

Fortunately, recent social theory has formulated a more precise concept of globalization than those typically offered by politicians and pundits. Although sharp differences continue to separate participants in the ongoing debate about the term, most contemporary social theorists endorse the view that globalization refers to fundamental changes in the spatial and temporal contours of social existence, according to which the significance of space or territory undergoes shifts in the face of a no less dramatic acceleration in the temporal structure of crucial forms of human activity. Geographical distance is typically measured in time. As the time necessary to connect distinct geographical locations is reduced, distance or space undergoes compression or “annihilation.” The human experience of space is intimately connected to the temporal structure of those activities by means of which we experience space. Changes in the temporality of human activity inevitably generate altered experiences of space or territory. Theorists of globalization disagree about the precise sources of recent shifts in the spatial and temporal contours of human life. Nonetheless, they generally agree that alterations in humanity’s experiences of space and time are working to undermine the importance of local and even national boundaries in many arenas of human endeavor. Since globalization contains far-reaching implications for virtually every facet of human life, it necessarily suggests the need to rethink key questions of normative political theory.

1. Globalization in the History of Ideas

2. globalization in contemporary social theory, 3. the normative challenges of globalization, other internet resources, related entries.

The term globalization has only become commonplace in the last three decades, and academic commentators who employed the term as late as the 1970s accurately recognized the novelty of doing so (Modelski 1972). At least since the advent of industrial capitalism, however, intellectual discourse has been replete with allusions to phenomena strikingly akin to those that have garnered the attention of recent theorists of globalization. Nineteenth and twentieth-century philosophy, literature, and social commentary include numerous references to an inchoate yet widely shared awareness that experiences of distance and space are inevitably transformed by the emergence of high-speed forms of transportation (for example, rail and air travel) and communication (the telegraph or telephone) that dramatically heighten possibilities for human interaction across existing geographical and political divides (Harvey 1989; Kern 1983). Long before the introduction of the term globalization into recent popular and scholarly debate, the appearance of novel high-speed forms of social activity generated extensive commentary about the compression of space.

Writing in 1839, an English journalist commented on the implications of rail travel by anxiously postulating that as distance was “annihilated, the surface of our country would, as it were, shrivel in size until it became not much bigger than one immense city” (Harvey 1996, 242). A few years later, Heinrich Heine, the émigré German-Jewish poet, captured this same experience when he noted: “space is killed by the railways. I feel as if the mountains and forests of all countries were advancing on Paris. Even now, I can smell the German linden trees; the North Sea’s breakers are rolling against my door” (Schivelbusch 1978, 34). Another young German émigré, the socialist theorist Karl Marx, in 1848 formulated the first theoretical explanation of the sense of territorial compression that so fascinated his contemporaries. In Marx’s account, the imperatives of capitalist production inevitably drove the bourgeoisie to “nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, and establish connections everywhere.” The juggernaut of industrial capitalism constituted the most basic source of technologies resulting in the annihilation of space, helping to pave the way for “intercourse in every direction, universal interdependence of nations,” in contrast to a narrow-minded provincialism that had plagued humanity for untold eons (Marx 1848, 476). Despite their ills as instruments of capitalist exploitation, Marx argued, new technologies that increased possibilities for human interaction across borders ultimately represented a progressive force in history. They provided the necessary infrastructure for a cosmopolitan future socialist civilization, while simultaneously functioning in the present as indispensable organizational tools for a working class destined to undertake a revolution no less oblivious to traditional territorial divisions than the system of capitalist exploitation it hoped to dismantle.

European intellectuals have hardly been alone in their fascination with the experience of territorial compression, as evinced by the key role played by the same theme in early twentieth-century American thought. In 1904, the literary figure Henry Adams diagnosed the existence of a “law of acceleration,” fundamental to the workings of social development, in order to make sense of the rapidly changing spatial and temporal contours of human activity. Modern society could only be properly understood if the seemingly irrepressible acceleration of basic technological and social processes was given a central place in social and historical analysis (Adams 1931 [1904]). John Dewey argued in 1927 that recent economic and technological trends implied the emergence of a “new world” no less noteworthy than the opening up of America to European exploration and conquest in 1492. For Dewey, the invention of steam, electricity, and the telephone offered formidable challenges to relatively static and homogeneous forms of local community life that had long represented the main theatre for most human activity. Economic activity increasingly exploded the confines of local communities to a degree that would have stunned our historical predecessors, for example, while the steamship, railroad, automobile, and air travel considerably intensified rates of geographical mobility. Dewey went beyond previous discussions of the changing temporal and spatial contours of human activity, however, by suggesting that the compression of space posed fundamental questions for democracy. Dewey observed that small-scale political communities (for example, the New England township), a crucial site for the exercise of effective democratic participation, seemed ever more peripheral to the great issues of an interconnected world. Increasingly dense networks of social ties across borders rendered local forms of self-government ineffective. Dewey wondered, “How can a public be organized, we may ask, when literally it does not stay in place?” (Dewey 1927, 140). To the extent that democratic citizenship minimally presupposes the possibility of action in concert with others, how might citizenship be sustained in a social world subject to ever more astonishing possibilities for movement and mobility? New high-speed technologies attributed a shifting and unstable character to social life, as demonstrated by increased rates of change and turnover in many arenas of activity (most important perhaps, the economy) directly affected by them, and the relative fluidity and inconstancy of social relations there. If citizenship requires some modicum of constancy and stability in social life, however, did not recent changes in the temporal and spatial conditions of human activity bode poorly for political participation? How might citizens come together and act in concert when contemporary society’s “mania for motion and speed” made it difficult for them even to get acquainted with one another, let alone identify objects of common concern? (Dewey 1927, 140).

The unabated proliferation of high-speed technologies is probably the main source of the numerous references in intellectual life since 1950 to the annihilation of distance. The Canadian cultural critic Marshall McLuhan made the theme of a technologically based “global village,” generated by social “acceleration at all levels of human organization,” the centerpiece of an anxiety-ridden analysis of new media technologies in the 1960s (McLuhan 1964, 103). Arguing in the 1970s and 1980s that recent shifts in the spatial and temporal contours of social life exacerbated authoritarian political trends, the French social critic Paul Virilio seemed to confirm many of Dewey’s darkest worries about the decay of democracy. According to his analysis, the high-speed imperatives of modern warfare and weapons systems strengthened the executive and debilitated representative legislatures. The compression of territory thereby paved the way for executive-centered emergency government (Virilio 1977). But it was probably the German philosopher Martin Heidegger who most clearly anticipated contemporary debates about globalization. Heidegger not only described the “abolition of distance” as a constitutive feature of our contemporary condition, but he linked recent shifts in spatial experience to no less fundamental alterations in the temporality of human activity: “All distances in time and space are shrinking. Man now reaches overnight, by places, places which formerly took weeks and months of travel” (Heidegger 1950, 165). Heidegger also accurately prophesied that new communication and information technologies would soon spawn novel possibilities for dramatically extending the scope of virtual reality : “Distant sites of the most ancient cultures are shown on film as if they stood this very moment amidst today’s street traffic…The peak of this abolition of every possibility of remoteness is reached by television, which will soon pervade and dominate the whole machinery of communication” (Heidegger 1950, 165). Heidegger’s description of growing possibilities for simultaneity and instantaneousness in human experience ultimately proved no less apprehensive than the views of many of his predecessors. In his analysis, the compression of space increasingly meant that from the perspective of human experience “everything is equally far and equally near.” Instead of opening up new possibilities for rich and multi-faceted interaction with events once distant from the purview of most individuals, the abolition of distance tended to generate a “uniform distanceless” in which fundamentally distinct objects became part of a bland homogeneous experiential mass (Heidegger 1950, 166). The loss of any meaningful distinction between “nearness” and “distance” contributed to a leveling down of human experience, which in turn spawned an indifference that rendered human experience monotonous and one-dimensional.

Since the mid-1980s, social theorists have moved beyond the relatively underdeveloped character of previous reflections on the compression or annihilation of space to offer a rigorous conception of globalization. To be sure, major disagreements remain about the precise nature of the causal forces behind globalization, with David Harvey (1989 1996) building directly on Marx’s pioneering explanation of globalization, while others (Giddens 19990; Held, McGrew, Goldblatt & Perraton 1999) question the exclusive focus on economic factors characteristic of the Marxist approach. Nonetheless, a consensus about the basic rudiments of the concept of globalization appears to be emerging.

First, recent analysts associate globalization with deterritorialization , according to which a growing variety of social activities takes place irrespective of the geographical location of participants. As Jan Aart Scholte observes, “global events can – via telecommunication, digital computers, audiovisual media, rocketry and the like – occur almost simultaneously anywhere and everywhere in the world” (Scholte 1996, 45). Globalization refers to increased possibilities for action between and among people in situations where latitudinal and longitudinal location seems immaterial to the social activity at hand. Even though geographical location remains crucial for many undertakings (for example, farming to satisfy the needs of a local market), deterritorialization manifests itself in many social spheres. Business people on different continents now engage in electronic commerce; academics make use of the latest Internet conferencing equipment to organize seminars in which participants are located at disparate geographical locations; the Internet allows people to communicate instantaneously with each other notwithstanding vast geographical distances separating them. Territory in the sense of a traditional sense of a geographically identifiable location no longer constitutes the whole of “social space” in which human activity takes places. In this initial sense of the term, globalization refers to the spread of new forms of non-territorial social activity (Ruggie 1993; Scholte 2000).