Recent developments in stress and anxiety research

- Published: 01 September 2021

- Volume 128 , pages 1265–1267, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Urs M. Nater 1 , 2

5382 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Stress and anxiety are virtually omnipresent in today´s society, pervading almost all aspects of our daily lives. While each and every one of us experiences “stress” and/or “anxiety” at least to some extent at times, the phenomena themselves are far from being completely understood. In stress research, scientists are particularly grappling with the conceptual issue of how to define stress, also with regard to delimiting stress from anxiety or negative affectivity in general. Interestingly, there is no unified theory of stress, despite many attempts at defining stress and its characteristics. Consequently, the available literature relies on a variety of different theoretical approaches, though the theories of Lazarus and Folkman ( 1984 ) or McEwen ( 1998 ) are relatively pervasive in the literature. One key issue in conceptualizing stress is that research has not always differentiated between the perception of a stimulus or a situation as a stressor and the subsequent biobehavioral response (often called the “stress response”). This is important, since, for example, psychological factors such as uncontrollability and social evaluation, i.e. factors that may influence how an individual perceives a potentially stressful stimulus or situation, have been identified as characteristics that elicit particularly powerful physiological stressful responses (Dickerson and Kemeny 2004 ). At the core of the physiological stress response is a complex physiological system, which is located in both the central nervous system (CNS) and the body´s periphery. The complexity of this system necessitates a multi-dimensional assessment approach involving variables that adequately reflect all relevant components. It is also important to consider that the experience of stress and its psychobiological correlates do not occur in a vacuum, but are being shaped by numerous contextual factors (e.g. societal and cultural context, work and leisure time, family and dyadic systems, environmental variables, physical fitness, nutritional status, etc.) and dispositional factors (e.g. genetics, personality, resilience, regulatory capacities, self-efficacy, etc.). Thus, a theoretical framework needs to incorporate these factors. In sum, as stress is considered a multi-faceted and inherently multi-dimensional construct, its conceptualization and operationalization needs to reflect this (Nater 2018 ).

The goal of the World Association for Stress Related and Anxiety Disorders (WASAD) is to promote and make available basic and clinical research on stress-related and anxiety disorders. Coinciding with WASAD’s 3rd International Congress held in September 2021 in Vienna, Austria, this journal publishes a Special Issue encompassing state-of-the art research in the field of stress and anxiety. This special issue collects answers to a number of important questions that need to be addressed in current and future research. Among the most relevant issues are (1) the multi-dimensional assessment that arises as a consequence of a multi-faceted consideration of stress and anxiety, with a particular focus on doing so under ecologically valid conditions. Skoluda et al. 2021 (in this issue) argue that hair as an important source of the stress hormone cortisol should not only be taken as a complementary stress biomarker by research staff, but that lay persons could be also trained to collect hair at the study participants’ homes, thus increasing the ecological validity of studies incorporating this important measure; (2) the incongruence between psychological and biological facets of stress and anxiety that has been observed both in laboratory and field research (Campbell and Ehlert 2012 ). Interestingly, there are behavioral constructs that do show relatively high congruence. As shown in the paper of Vatheuer et al. ( 2021 ), gaze behavior while exposed to an acute social stressor correlates with salivary cortisol, thus indicating common underlying mechanisms; (3) the complex dynamics of stress-related measures that may extend over shorter (seconds to minutes), medium (hours and diurnal/circadian fluctuations), and longer (months, seasonal) time periods. In particular, momentary assessment studies are highly qualified to examine short to medium term fluctuations and interactions. In their study employing such a design, Stoffel and colleagues (Stoffel et al. 2021 ) show ecologically valid evidence for direct attenuating effects of social interactions on psychobiological stress. Using an experimental approach, on the other hand, Denk et al. ( 2021 ) examined the phenomenon of physiological synchrony between study participants; they found both cortisol and alpha-amylase physiological synchrony in participants who were in the same group while being exposed to a stressor. Importantly, these processes also unfold over time in relation to other biological systems; al’Absi and colleagues showed in their study (al’Absi et al. 2021 ) the critical role of the endogenous opioid system and its relation to stress-related analgesia; (4) the influence of contextual and dispositional factors on the biological stress response in various target samples (e.g., humans, animals, minorities, children, employees, etc.) both under controlled laboratory conditions and in everyday life environments. In this issue, Sattler and colleagues show evidence that contextual information may only matter to a certain extent, as in their study (Sattler et al. 2021 ), the biological response to a gay-specific social stressor was equally pronounced as the one to a general social stressor in gay men. Genetic information is probably the most widely researched dispositional factor; Kuhn et al. show in their paper (Kuhn et al. 2021 ) that the low expression variant of the serotonin transporter gene serves as a risk factor for increased stress reactivity, thus clearly indicating the important role of dispositional factors in stress processing. An interesting factor combining both aspects of dispositional and contextual information is maternal care; Bentele et al. ( 2021 ) in their study are able to show that there was an effect of maternal care on the amylase stress response, while no such effect was observed for cortisol. In a similar vein, Keijser et al. ( 2021 ) showed in their gene-environment interaction study that the effects of FKBP5, a gene very closely related to HPA axis regulation, and early life stress on depressive symptoms among young adults was moderated by a positive parenting style; and (5) the role of stress and anxiety as transdiagnostic factors in mental disorders, be it as an etiological factor, a variable contributing to symptom maintenance, or as a consequence of the condition itself. Stress, e.g., as a common denominator for a broad variety of psychiatric diagnoses has been extensively discussed, and stress as an etiological factor holds specific significance in the context of transdiagnostic approaches to the conceptualization and treatment of mental disorders (Wilamowska et al. 2010 ). The HPA axis, specifically, is widely known to be dysregulated in various conditions. Fischer et al. ( 2021 ) discuss in their comprehensive review the role of this important stress system in the context of patients with post-traumatic disorder. Specifically focusing on the cortisol awakening response, Rausch and colleagues provide evidence for HPA axis dysregulation in patients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (Rausch et al. 2021 ). As part of a longitudinal project on ADHD, Szep et al. ( 2021 ) investigated the possible impact of child and maternal ADHD symptoms on mothers’ perceived chronic stress and hair cortisol concentration; although there was no direct association, the findings underline the importance of taking stress-related assessments into consideration in ADHD studies. As the HPA axis is closely interacting with the immune system, Rhein et al. ( 2021 ) examined in their study the predicting role of the cytokine IL-6 on psychotherapy outcome in patients with PTSD, indicating that high reactivity of IL-6 to a stressor at the beginning of the therapy was associated with a negative therapy outcome. The review of Kyunghee Kim et al. ( 2021 ) also demonstrated the critical role of immune pathways in the molecular changes due to antidepressant treatment. As for the therapy, the important role of cognitive-behavioral therapy with its key elements to address both stress and anxiety reduction have been shown in two studies in this special issue, evidencing its successful application in obsessive–compulsive disorder (Ivarsson et al. 2021 ; Hollmann et al. 2021 ). Thus, both stress and anxiety are crucial transdiagnostic factors in various mental disorders, and future research needs elaborate further on their role in etiology, maintenance, and treatment.

In conclusion, a number of important questions are being asked in stress and anxiety research, as has become evident above. The Special Issue on “Recent developments in stress and anxiety research” attempts to answer at least some of the raised questions, and I want to invite you to inspect the individual papers briefly introduced above in more detail.

al’Absi M, Nakajima M, Bruehl S (2021) Stress and pain: modality-specific opioid mediation of stress-induced analgesia. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02401-4

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bentele UU, Meier M, Benz ABE, Denk BF, Dimitroff SJ, Pruessner JC, Unternaehrer E (2021) The impact of maternal care and blood glucose availability on the cortisol stress response in fasted women. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02350-y

Article Google Scholar

Campbell J, Ehlert U (2012) Acute psychosocial stress: does the emotional stress response correspond with physiological responses? Psychoneuroendocrinology 37(8):1111–1134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.12.010

Denk B, Dimitroff SJ, Meier M, Benz ABE, Bentele UU, Unternaehrer E, Popovic NF, Gaissmaier W, Pruessner JC (2021) Influence of stress on physiological synchrony in a stressful versus non-stressful group setting. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02384-2

Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME (2004) Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol Bull 130(3):355–391

Fischer S, Schumacher T, Knaevelsrud C, Ehlert U, Schumacher S (2021) Genes and hormones of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in post-traumatic stress disorder. What is their role in symptom expression and treatment response? J Neural Transm (vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02330-2

Hollmann K, Allgaier K, Hohnecker CS, Lautenbacher H, Bizu V, Nickola M, Wewetzer G, Wewetzer C, Ivarsson T, Skokauskas N, Wolters LH, Skarphedinsson G, Weidle B, de Haan E, Torp NC, Compton SN, Calvo R, Lera-Miguel S, Haigis A, Renner TJ, Conzelmann A (2021) Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy in children and adolescents with obsessive compulsive disorder: a feasibility study. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02409-w

Ivarsson T, Melin K, Carlsson A, Ljungberg M, Forssell-Aronsson E, Starck G, Skarphedinsson G (2021) Neurochemical properties measured by 1 H magnetic resonance spectroscopy may predict cognitive behaviour therapy outcome in paediatric OCD: a pilot study. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02407-y

Keijser R, Olofsdotter S, Nilsson WK, Åslund C (2021) Three-way interaction effects of early life stress, positive parenting and FKBP5 in the development of depressive symptoms in a general population. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02405-0

Kuhn L, Noack H, Skoluda N, Wagels L, Rohr AK, Schulte C, Eisenkolb S, Nieratschker V, Derntl B, Habel U (2021) The association of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and the response to different stressors in healthy males. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02390-4

Kyunghee Kim H, Zai G, Hennings J, Müller DJ, Kloiber S (2021) Changes in RNA expression levels during antidepressant treatment: a systematic review. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02394-0

Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1984) Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publisher Company Inc, New York

Google Scholar

McEwen BS (1998) Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med 338(3):171–179

Article CAS Google Scholar

Nater UM (2018) The multidimensionality of stress and its assessment. Brain Behav Immun 73:159–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2018.07.018

Rausch J, Flach E, Panizza A, Brunner R, Herpertz SC, Kaess M, Bertsch K (2021) Associations between age and cortisol awakening response in patients with borderline personality disorder. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02402-3

Rhein C, Hepp T, Kraus O, von Majewski K, Lieb M, Rohleder N, Erim Y (2021) Interleukin-6 secretion upon acute psychosocial stress as a potential predictor of psychotherapy outcome in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02346-8

Sattler FA, Nater UM, Mewes R (2021) Gay men’s stress response to a general and a specific social stressor. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02380-6

Skoluda N, Piroth I, Gao W, Nater UM (2021) HOME vs. LAB hair samples for the determination of long-term steroid concentrations: a comparison between hair samples collected by laypersons and trained research staff. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02367-3

Stoffel M, Abbruzzese E, Rahn S, Bossmann U, Moessner M, Ditzen B (2021) Covariation of psychobiological stress regulation with valence and quantity of social interactions in everyday life: disentangling intra- and interindividual sources of variation. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02359-3

Szep A, Skoluda N, Schloss S, Becker K, Pauli-Pott U, Nater UM (2021) The impact of preschool child and maternal attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms on mothers’ perceived chronic stress and hair cortisol. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02377-1

Vatheuer CC, Vehlen A, von Dawans B, Domes G (2021) Gaze behavior is associated with the cortisol response to acute psychosocial stress in the virtual TSST. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02344-w

Wilamowska ZA, Thompson-Hollands J, Fairholme CP, Ellard KK, Farchione TJ, Barlow DH (2010) Conceptual background, development, and preliminary data from the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders. Depress Anxiety 27(10):882–890. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20735

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Clinical and Health Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Urs M. Nater

University Research Platform ‘The Stress of Life – Processes and Mechanisms Underlying Everyday Life Stress’, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Urs M. Nater .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Nater, U.M. Recent developments in stress and anxiety research. J Neural Transm 128 , 1265–1267 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02410-3

Download citation

Accepted : 13 August 2021

Published : 01 September 2021

Issue Date : September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02410-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 15 April 2020

Practice of stress management behaviors and associated factors among undergraduate students of Mekelle University, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study

- Gebrezabher Niguse Hailu 1

BMC Psychiatry volume 20 , Article number: 162 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

31k Accesses

1 Citations

Metrics details

Stress is one of the top five threats to academic performance among college students globally. Consequently, students decrease in academic performance, learning ability and retention. However, no study has assessed the practice of stress management behaviors and associated factors among college students in Ethiopia. So the purpose of this study was to assess the practice of stress management behaviors and associated factors among undergraduate university students at Mekelle University, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2019.

A cross-sectional study was conducted on 633 study participants at Mekelle University from November 2018 to July 2019. Bivariate analysis was used to determine the association between the independent variable and the outcome variable at p < 0.25 significance level. Significant variables were selected for multivariate analysis.

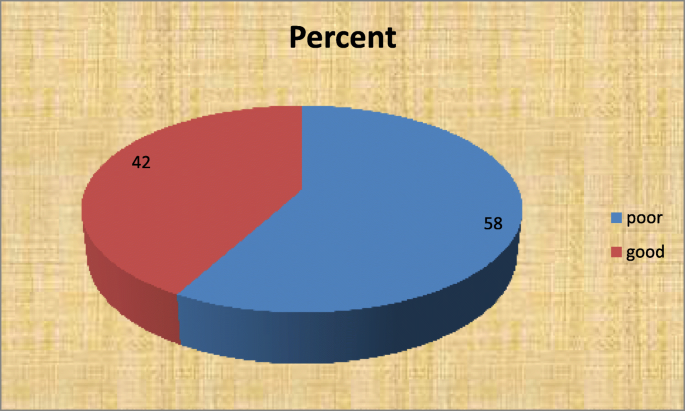

The study found that the practice of stress management behaviors among undergraduate Mekelle university students was found as 367(58%) poor and 266(42%) good. The study also indicated that sex, year of education, monthly income, self-efficacy status, and social support status were significant predictors of stress management behaviors of college students.

This study found that the majority of the students had poor practice of stress management behaviors.

Peer Review reports

Stress is the physical and emotional adaptive response to an external situation that results in physical, psychological and behavioral deviations [ 1 ]. Stress can be roughly subdivided into the effects and mechanisms of chronic and acute stress [ 2 ]. Chronic psychological stress in early life and adulthood has been demonstrated to result in maladaptive changes in both the HPA-axis and the sympathetic nervous system. Acute and time-limited stressors seem to result in adaptive redistribution of all major leukocyte subpopulations [ 2 ].

Stress management behaviors are defined as behaviors people often use in the face of stress /or trauma to help manage painful or difficult emotions [ 3 ]. Stress management behaviors include sleeping 6–8 h each night, Make an effort to monitor emotional changes, Use adequate responses to unreasonable issues, Make schedules and set priorities, Make an effort to determine the source of each stress that occurs, Make an effort to spend time daily for muscle relaxation, Concentrate on pleasant thoughts at bedtime, Feel content and peace with yourself [ 4 ]. Practicing those behaviors are very important in helping people adjust to stressful events while helping them maintain their emotional wellbeing [ 3 ].

University students are a special group of people that are enduring a critical transitory period in which they are going from adolescence to adulthood and can be one of the most stressful times in a person’s life [ 5 ]. According to the American College Health Association’s National College Health Assessment, stress is one of the top five threats to academic performance among college students [ 6 ]. For instance, stress is a serious problem in college student populations across the United States [ 7 ].

I have searched literatures regarding stress among college students worldwide. For instance, among Malaysian university students, stress was observed among 36% of the respondents [ 8 ]. Another study reported that 43% of Hong Kong students were suffered from academic stress [ 9 ]. In western countries and other Middle Eastern countries, including 70% in Jordan [ 10 ], 83.9% in Australia [ 11 ]. Furthermore, based on a large nationally representative study the prevalence of stress among college students in Ethiopia was 40.9% [ 12 ].

Several studies have shown that socio-demographic characteristics and psychosocial factors like social support, health value and perceived self-efficacy were known to predict stress management behaviors [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ].

Although the prevalence of stress among college students is studied in many countries including Ethiopia, the practice of stress management behaviors which is very important in promoting the health of college students is not studied in Ethiopia. Therefore this study aimed to assess the practice of stress management behaviors and associated factors among undergraduate students at Mekelle University.

The study was conducted at Mekelle university colleges from November 2018 to July 2019 in Mekelle city, Tigray, Ethiopia. Mekelle University is a higher education and training public institution located in Mekelle city, Tigray at a distance of 783 Kilometers from the Ethiopian capital ( http://www.mu.edu.et/ ).

A cross-sectional study was conducted on 633 study participants. Students who were ill (unable to attend class due to illness), infield work and withdrawal were not included in the study.

The actual sample size (n) was computed by single population proportion formula [n = [(Za/2)2*P (1 − P)]/d2] by assuming 95% confidence level of Za/2 = 1.96, margin of error 5%, proportion (p) of 50% and the final sample size was estimated to be 633. A 1.5 design effect was used by considering the multistage sampling technique and assuming that there was no as such big variations among the students included in the study.

Multi-stage random sampling was used. Three colleges (College of health science, college of business and Economics and College of Natural and Computational Science) were selected from a total of the seven Colleges from Mekelle University using a simple random sampling technique in which proportional sample allocation was considered from each college.

Data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire by trained research assistants at the classes.

The questionnaire has three sections. The first section contained questions on demographic characteristics of the study participants. The second section contained questions to assess the practice of stress management of the students. The tool to assess the practice of stress management behaviors for college students was developed by Walker, Sechrist, and Pender [ 4 ]. The third section consisted of questions for factors associated with stress management of the students divided into four sub-domains, including health value used to assess the value participants place on their health [ 18 ]. The second subdomain is self-efficacy designed to assess optimistic self-beliefs to cope with a variety of difficult demands in life [ 19 ] and was adapted by Yesilay et al. [ 20 ]. The third subdomain is perceived social support measures three sources of support: family, friends, and significant others [ 21 ] and was adapted by Eker et al. [ 22 ]. The fourth subscale is perceived stress measures respondents’ evaluation of the stressfulness of situations in the past month of their lives [ 23 ] and was adapted by Örücü and Demir [ 24 ].

The entered data were edited, checked visually for its completeness and the response was coded and entered by Epi-data manager version 4.2 for windows and exported to SPSS version 21.0 for statistical analysis.

Bivariate analysis was used to determine the association between the independent variable and the outcome variable. Variables that were significant at p < 0.25 with the outcome variable were selected for multivariable analysis. And odds ratio with 95% confidence level was computed and p -value <= 0.05 was described as a significant association.

Operational definition

Good stress management behavior:.

Students score above or equal to the mean score.

Poor stress management behavior:

Students score below the mean score [ 4 ].

Seciodemographic characteristics

Among the total 633 study participants, 389(61.5%) were males, of those 204(32.2%) had poor stress management behavior. The Median age of the respondents was 20.00 (IQR = ±3). More ever, this result showed that 320(50.6%) of the students came from rural areas, 215(34%) of them had poor stress management behavior.

The result revealed that 363(57.35%) of the study participants were 2nd and 3rd year students, of them 195 (30.8%) had poor stress management.

This result indicated that 502 (79.3%) of the participants were in the monthly support category of > = 300 ETB with a median income of 300.00 ETB (IQR = ±500), from those, 273(43.1%) students had poor stress management behavior (Table 1 ).

Status of practice of stress management behaviors of under graduate students at Mekelle University, Ethiopia

Psychosocial factors

This result indicated that 352 (55.6%) of the students had a high health value status of them 215 (34%) had good stress management behavior. It also showed that 162 (25.6%) of the students had poor perceived self-efficacy, from those 31(4.9%) had a good practice of stress management behavior. Moreover, the result showed that 432(68.2%) of the study participants had poor social support status of them 116(18.3%) had a good practice of stress management behavior (Table 1 ).

Practice of stress management behaviors

The result showed that the majority (49.8%) of the students were sometimes made an effort to spend time daily for muscle relaxation. Whereas only 28(4.4%) students were routinely concentrated on pleasant thoughts at bedtime.

According to this result, only 169(26.7%) of the students were often made an effort to determine the source of stress that occurs. It also revealed that the majority (40.1%) of the students were never made an effort to monitor their emotional changes. Similarly, the result indicated that the majority (42.5%) of the students were never made schedules and set priorities.

The result revealed that only 68(10.7%) of the students routinely slept 6–8 h each night. More ever, the result showed that the majority (34.4%) of the students were sometimes used adequate responses to unreasonable issues (Table 2 ).

Status of the practice of stress management behaviors

The result revealed that the practice of stress management behaviors among regular undergraduate Mekelle university students was found as 367(58%) poor and 266(42%) good. (Fig 1 )

Factors associated with stress management behaviors

In the bivariate analysis sex, college, year of education, student’s monthly income’, perceived-self efficacy, perceived social support and perceived stress were significantly associated with stress management behavior at p < =0.25. Whereas in the multivariate analysis sex, year of education, student’s monthly income’, perceived-self efficacy and perceived social support were significantly associated with stress management behavior at p < =0.05.

Male students were 3.244 times more likely to have good practice stress management behaviors than female students (AOR: 3.244, CI: [1.934–5.439]). Students who were in the age category of less than 20 years were 70% less to have a good practice of stress management behaviors than students with the age of greater or equal to 20 year (AOR: 0.300, CI:[0.146–0.618]).

Students who had monthly income less than300 ETB were 64.4% less to have a good practice of stress management behaviors than students with monthly income greater or equal to 300 ETB (AOR: 0.356, CI:[0.187–0.678]).

Students who had poor self- efficacy status were 70.3% less to have a good practice of stress management behaviors than students with good self-efficacy status (AOR: 0.297, CI:[0.159–0.554]). Students who had poor social support were 70.5% less to have a good practice of stress management behaviors than students with good social support status (AOR: 0.295[0.155–0.560]) (Table 3 ).

The present study showed that the practice of stress management behaviors among regular undergraduate students was 367(58%) poor and 266(42%) good. The study indicated that sex, year of education, student’s monthly income, social support status, and perceived-self efficacy status were significant predictors of stress management behaviors of students.

The current study revealed that male students were more likely to have good practice of stress management behaviors than female students. This finding is contradictory with previous studies conducted in the USA [ 13 , 25 ], where female students were showed better practice of stress management behaviors than male students. This difference might be due to socioeconomic and measurement tool differences.

The current study indicated that students with monthly income less than 300 ETB were less likely to have good practice of stress management behaviors than students with monthly income greater than or equal to 300 ETB. This is congruent with the recently published book which argues a better understanding of our relationship with money (income). The book said “the people with more money are, on average, happier than the people with less money. They have less to worry about because they are not worried about where they are going to get food or money for their accommodation or whatever the following week, and this has a positive effect on their health” [ 26 ].

The present study found that first-year students were less likely to have good practice of stress management behaviors than senior students. This finding is similar to previous findings from Japan [ 27 ], China [ 28 ] and Ghana [ 29 ]. This might be because freshman students may encounter a multitude of stressors, some of which they may have dealt with in high school and others that may be a new experience for them. With so many new experiences, responsibilities, social settings, and demands on their time. As a first-time, incoming college freshman, experiencing life as an adult and acclimating to the numerous and varied types of demands placed on them can be a truly overwhelming experience. It can also lead to unhealthy amounts of stress. A report by the Anxiety and Depression Association of America found that 80% of freshman students frequently or sometimes experience daily stress [ 30 ].

The current study showed that students with poor self-efficacy status were less likely to have good practice of stress management behaviors. This is congruent with the previous study that has demonstrated quite convincingly that possessing high levels of self-efficacy acts to decrease people’s potential for experiencing negative stress feelings by increasing their sense of being in control of the situations they encounter [ 14 ]. More ever this study found that students with poor social support were less likely to have a good practice of stress management behaviors. This finding is similar to previous studies that found good social support, whether from a trusted group or valued individual, has shown to reduce the psychological and physiological consequences of stress, and may enhance immune function [ 15 , 16 , 17 ].

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance and approval obtained from the institutional review board of Mekelle University. Moreover, before conducting the study, the purpose and objective of the study were described to the study participants and written informed consent was obtained. The study participants were informed as they have full right to discontinue during the interview. Subject confidentiality and any special data security requirements were maintained and assured by not exposing the patient’s name and information.

Limitation of the study

There is limited literature regarding stress management behaviors and associated factors. There is no similar study done in Ethiopia previously. More ever, using a self-administered questionnaire, the respondents might not pay full attention to it/read it properly.

This study found that the majority of the students had poor practice of stress management behaviors. The study also found that sex, year of education, student’s monthly income, social support status, and perceived-self efficacy status were significant predictors of stress management behaviors of the students.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Adjusted Odd Ratio

College of Business& Economics

College of health sciences

Confidence interval

College of natural and computational sciences

Crud odds ratio

Ethiopian birr

Master of Sciences

United States of America

United kingdom

Figueroa-Romero C, Sadidi M, Feldman EL. Mechanisms of disease: the oxidative stress theory of diabetic neuropathy. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2008;9(4):301–14.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Lagraauw HM, Kuiper J, Bot I. Acute and chronic psychological stress as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: insights gained from epidemiological, clinical and experimental studies. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;50:18–30.

Article Google Scholar

Greenberg J. Comprehensive stress management: McGraw-Hill Education; 2012.

Walker SN, Sechrist KR, Pender NJ. The health-promoting lifestyle profile: development and psychometric characteristics. Nurs Res. 1987.

Buchanan JL. Prevention of depression in the college student population: a review of the literature. Arch Psychiatric Nurs. 2012;26(1):21–42.

Kisch J, Leino EV, Silverman MM. Aspects of suicidal behavior, depression, and treatment in college students: results from the spring 2000 National College Health Assessment Survey. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005;35(1):3–13.

Crandall KJ, Steward K, Warf TM. A mobile app for reducing perceived stress in college students. Am J Health Stud. 2016;31(2):68–73.

Google Scholar

Gan WY, Nasir MM, Zalilah MS, Hazizi AS. Disordered eating behaviors, depression, anxiety and stress among Malaysian university students. Coll Stud J. 2011;45(2):296–31.

Wong JG, Cheung EP, Chan KK, Ma KK, Wa TS. Web-based survey of depression, anxiety and stress in first-year tertiary education students in Hong Kong. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40(9):777–82.

Abu-Ghazaleh SB, Rajab LD, Sonbol HN. Psychological stress among dental students at the University of Jordan. J Dent Educ. 2011;75(8):1107–14.

PubMed Google Scholar

McDermott BM, Cobham VE, Berry H, Stallman HM. Vulnerability factors for disaster-induced child post-traumatic stress disorder: the case for low family resilience and previous mental illness. Austr New Zeal J Psychiatry. 2010;44(4):384–9.

Dachew BA, Bisetegn TA, Gebremariam RB. Prevalence of mental distress and associated factors among undergraduate students of the University of Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional institutional based study. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119464.

Matheny KB, Ashby JS, Cupp P. Gender differences in stress, coping, and illness among college students. J Individ Psychol. 2005;1:61(4).

Mills H, Reiss N, Dombeck M. Self-efficacy and the perception of control in stress reduction: Mental Help; 2008.

Morisky DE, DeMuth NM, Field-Fass M, Green LW, Levine DM. Evaluation of family health education to build social support for long-term control of high blood pressure. Health Educ Q. 1985;12(1):35–50.

Yilmaz FT, Sabancıogullari S, Aldemir K, Kumsar AK. Does social support affect development of cognitive dysfunction in individuals with diabetes mellitus? Saudi Med J. 2015;36(12):1425.

Barrera M Jr, Toobert DJ, Angell KL, Glasgow RE, MacKinnon DP. Social support and social-ecological resources as mediators of lifestyle intervention effects for type 2 diabetes. J Health Psychol. 2006;11(3):483–95.

Lau RR, Hartman KA, Ware JE. Health as a value: methodological and theoretical considerations. Health Psychol. 1986;5(1):25.

Zhang JX, Schwarzer R. Measuring optimistic self-beliefs: A Chinese adaptation of the General Self-Efficacy Scale. Psychologia. 1995.

Peker K, Bermek G. Predictors of health-promoting behaviors among freshman dental students at Istanbul University. J Dent Educ. 2011;75(3):413–20.

Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41.

Eker D, Arkar H, Yaldiz H. Generality of support sources and psychometric properties of a scale of perceived social support in Turkey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2000;35(5):228–33.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;1:385–96.

Örücü MÇ, Demir A. Psychometric evaluation of perceived stress scale for Turkish university students. Stress Health. 2009;25(1):103–9.

Crockett LJ, Iturbide MI, Torres Stone RA, McGinley M, Raffaelli M, Carlo G. Acculturative stress, social support, and coping: relations to psychological adjustment among Mexican American college students. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2007;13(4):347.

Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness: Penguin; 2009..

Wei CN, Harada K, Ueda K, Fukumoto K, Minamoto K, Ueda A. Assessment of health-promoting lifestyle profile in Japanese university students. Environ Health Prev Med. 2012;17(3):222.

Wang D, Ou CQ, Chen MY, Duan N. Health-promoting lifestyles of university students in mainland China. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):379.

Amponsah M, Owolabi HO. Perceived stress levels of fresh university students in Ghana: a case study. J Educ Soc Behav Sci. 2011;27:153–69.

Beiter R, Nash R, McCrady M, Rhoades D, Linscom BM, Clarahan M, Sammut S. The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. J Affect Disord. 2015;173:90–6.

Download references

Acknowledgments

Author thanks Mekelle University, data collectors, supervisors and study participants.

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of nursing, Mekelle University, Tigray, Ethiopia

Gebrezabher Niguse Hailu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Make an interpretation of the data, make the analysis of the data, prepares and submits the manuscript. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gebrezabher Niguse Hailu .

Ethics declarations

Ethical clearance and approval obtained from the institutional review board of Mekelle University. Moreover, before conducting the study, the purpose and objective of the study were described to the study participants and written informed consent was obtained. The study participants were informed as they have full right to discontinue. Subject confidentiality and any special data security requirements were maintained and assured by not exposing patients’ names and information. Besides, the questionnaires and all other information were stored on a personal computer which is protected with a password.

Consent for publication

Not applicable as there is no image or other confidentiality related issues.

Competing interests

The author declares that he/she has no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Hailu, G.N. Practice of stress management behaviors and associated factors among undergraduate students of Mekelle University, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 20 , 162 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02574-4

Download citation

Received : 04 October 2019

Accepted : 30 March 2020

Published : 15 April 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02574-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Stress management

- University students

BMC Psychiatry

ISSN: 1471-244X

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Individual stress response patterns: Preliminary findings and possible implications

Roles Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

¶ ‡ These authors are joint senior authors on this work.

Affiliation Stress, Hope and Cope Lab., School of Behavioral Sciences, Tel-Aviv Yaffo Academic College, Tel-Aviv Yaffo, Israel

Roles Investigation, Writing – original draft

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft

Roles Conceptualization, Resources

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing

- Rebecca Jacoby,

- Keren Greenfeld Barsky,

- Tal Porat,

- Stav Harel,

- Tsipi Hanalis Miller,

- Gil Goldzweig

- Published: August 13, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255889

- Reader Comments

Research on stress occupied a central position during the 20 th century. As it became evident that stress responses affect a wide range of negative outcomes, various stress management techniques were developed in attempt to reduce the damages. However, the existing interventions are applied for a range of different stress responses, sometimes unsuccessfully.

The aim of this study was to examine whether there are specific clusters of stress responses representing interpersonal variation. In other words, do people have dominant clusters reflecting the different aspects of the known stress responses (physiological, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive)?

The researchers derived a measure of stress responses based on previous scales and used it in two studies in order to examine the hypothesis that stress responses can be grouped into dominant patterns according to the type of response.

The results of Study 1 revealed four distinctive response categories: psychological (emotional and cognitive), physiological gastro, physiological muscular, and behavioral. The results of Study 2 revealed five distinctive response categories: emotional, cognitive, physiological gastro, physiological muscular, and behavioral.

By taking into consideration each person’s stress response profile while planning stress management interventions and then offering them a tailored intervention that reduces the intensity of these responses, it might be possible to prevent further complications resulting in a disease (physical or mental).

Citation: Jacoby R, Greenfeld Barsky K, Porat T, Harel S, Hanalis Miller T, Goldzweig G (2021) Individual stress response patterns: Preliminary findings and possible implications. PLoS ONE 16(8): e0255889. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255889

Editor: Georgia Panayiotou, University of Cyprus, CYPRUS

Received: February 13, 2021; Accepted: July 26, 2021; Published: August 13, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Jacoby et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data is registered and available through the Open Science Framework (OSF): Goldzweig, G., Jacoby, R., Barsky, K. G., Porat, T., Harel, S., & Miller, T. H. (2021, July 10). Individual stress response patterns: Preliminary findings and possible implications. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/XQ2TA .

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The concept of stress in its various forms (such as anxiety and fear) has been known since the 18 th century but became central during the 20 th century. Stress models were, consequently, developed in order to explain the processes undertaken in response to stressors. Early stress research underlined the adaptive nature of organisms’ physiological response to acute stress and the potentially deleterious effects of prolonged stressors [ 1 , 2 ]. Later on, the research expanded to humans emphasizing the cognitive system as mediating between stressors and stress responses [ 3 , 4 ]. As it became evident that continuing or repeated stress responses affect a wide range of negative outcomes, both physical and psychological [ 5 , 6 ], various stress management techniques were developed in an attempt to reduce the harms [ 7 – 10 ]. These include psychophysiological techniques (such as relaxation, biofeedback and more) aiming to reduce stress responses and regaining control, as well as cognitive behavioral techniques aiming to challenge misleading perceptions. A substantial body of research has explored the efficacy of these techniques (e.g. [ 10 ]). However, in most cases, interventions were not tailored to specific patterns of responses, and thus, the same interventions were used, sometimes unsuccessfully, for various stress responses. Since stress responses influence organisms’ coping and health outcomes, their study is important. We believe that by better understanding the complexity of stress responses, appropriate interventions can be developed and implemented.

Theories on stress responses

In the past, stress responses were studied and described mainly by physiologists,. Darwin (1809–1882), who studied the manifested responses of animals and humans to emotional situations, was mainly interested in the observable responses and not in the biochemical changes that occur in response to stress [ 11 ]. Immense strides toward understanding stress responses and their physiological basis were made by Cannon (1871–1945) and Selye (1907–1982). Cannon [ 2 ] studied the homeostatic mechanisms underlying the “fight or flight” response to stressful situations, while Selye [ 1 ] later developed the general adaptation syndrome (GAS) theory, which describes the process of responding to an ongoing stress.

According to these theories, exposure to a stressful event activates a series of autonomic system reactions that cause changes within organs [ 12 , 13 ]. The reactions found were the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). Activation of the HPA axis and the SNS causes hormonal secretions of adrenaline and cortisol and the behavioral “fight or flight” reaction [ 2 ]. According to Berger et al. [ 14 ], the “fight or flight” response is triggered by osteocalcin, a protein released by the skeleton as a hormone, which, they claimed, is a messenger, sent by bone to regulate crucial processes all over the body, including how we respond to danger.

Porges [ 15 ] asserted that although these arousal theories have empirical support when measuring the effects of acute stress, they neglect other aspects of the physiological stress response such as parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) influences and interaction between sympathetic and parasympathetic processes. This neglect limits the theories’ ability to explain a wide variety of stress responses such as freezing, tonic immobility, fainting, and syncope. Porges’ polyvagal theory looks to explain the mechanism underlying the interpersonal differences of physiological and psychological stress responses. Other theories on the role of oxytocin for moderating the autonomic nervous system (e.g., [ 16 ]) and on gender differences, such as “tend and befriend” [ 17 ], have focused on responses directed toward safety behaviors.

Although these researchers have tried to include a psychological dimension in their models, this was mainly cast in terms of stimulus-response relationships, consistent with the dominant physiological and behavioral approaches of the period, and therefore could not explain why different people who are exposed to the same stimulus respond differently. These models, which were derived from animal behavior, were criticized for their universal approach of focusing solely on biological mechanisms and disregarding humans’ subjective perception of the stress experience [ 18 ].

From the middle of the 20 th century, the concept of stress came to occupy a central position in the psychological literature, and new stress models were developed emphasizing the interactions between individuals and their environment. The leading model in psychological stress research is the Transactional Model developed by Lazarus and Folkman [ 3 ]. This model focuses on the cognitive processes preceding the stress response and promotes the understanding of interpersonal variance in the stress responses to the same events. It emphasizes the importance of the individuals’ appraisal of the meaning of the stressful event and their own resources for coping with this event to help mediate between the stressor and stress responses of the organism. It also established the understanding that different individuals will react to the same event with varying intensity or duration: one will find an event threatening, while the other will find it neutral or realize that they have the required coping resources. The Transactional Model does not, however, explain the interpersonal variance of the stress response patterns and of stress influences on health.

Other theories have proposed a more integrative outlook on the stress-related cascade of events, starting even before the encounter with a potential stressor and resulting in various health outcomes. They have suggested a process that is mediated by cognitive appraisal, behavioral outcomes, and physiological mechanisms [ 19 , 20 ]. For example, Brosschot, Gerin, & Thayer [ 21 ] argue that perseverative cognition as manifested in worry, rumination and anticipatory stress should be considered as they are associated with enhanced cardiovascular, endocrinological, immunological, and neurovisceral activity. Others [ 22 , 23 ] have suggested that personality traits are also likely to influence how people respond to stress. These approaches consider all of the main aspects depicted by prior models and provide a wider perspective for both researchers and clinicians.

The aforementioned theories notwithstanding, individual differences of stress responses as represented by different clusters in a non-pathological population have not, to the best of our knowledge, been studied. The purpose of the current study was, therefore, to address this gap and examine whether reported stress responses do, in fact, reflect clusters of the common stress responses: physiological, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive. We also strived to assess interpersonal variation in stress responses; in other words, do people have dominant clusters of stress responses?

Measuring stress responses

Different scales were developed to measure stress responses. For example, Terluin [ 24 ] developed the Four-Dimensional Symptom Questionnaire (4DSQ) in order to differentiate between general distress and what he considered as psychiatric symptoms, namely, depression, anxiety, and somatization. Schlebusch [ 25 ] developed the Stress Symptom Checklist (SSCL) which consists of three categories: physical, psychological, and behavioral. The checklist was intended to be a diagnostic tool that measures specific stress-related psychopathological conditions or disorders, particularly the intensity (or severity) of stress as reflected by an individual’s physical, psychological, and behavioral reactions.

These scales were primarily intended to measure the total intensity of the stress response in order to identify either pathological or intense stress responses, assuming the existence of a unified stress response for all. They ignored the different patterns people exhibit when confronted by a stressor, thus limiting their ability to characterize an individual’s dominant stress response pattern. Based on these works and others, stress responses were generally classified into four categories: physiological, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive [ 26 , 27 ].

Two studies were conducted in order to examine the hypothesis that stress responses can be grouped into dominant patterns according to the type of response (physiological, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive). Although the existing scales include various items representing the above mentioned categories they are too long and didn’t meet our research purposes. Therefore we have decided to derive a short scale of stress responses, representing the four categories, based on the above mentioned scales (see details under " items selection" in the Study 1 description). Participants in the first study were students while participants in the second study were a sample of people suffering from the stress-related medical syndromes of fibromyalgia (FM), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), or both. Participants in both studies were asked to rate the extent to which different stress responses characterize their typical responses to stress. The results are presented separately for each study.

The same statistical analysis was used for both studies. Descriptive statistics was calculated for each item (stress response). We conducted an exploratory factor analysis (principle component analyses with Varimax rotation) of all items. For the second study we also calculated sub-scale scores (base and factor analysis) and compared these scores between the study groups.

The two studies were approved by the ethics committee of the Academic College of Tel Aviv-Yaffo, and all participants signed an electronic consent form prior to the study’s initiation.

Step 1: Items selection

In order to create a comprehensive list of stress response measures, the authors screened the two validated stress response questionnaires: the Four-Dimensional Symptom Questionnaire [ 24 ] and the Stress Symptom Checklist [ 25 ]. The responses were pre-classified separately by each of the authors into the four categories: physiological, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive. Discrepancies between the authors were discussed and resolved when at least four of the six authors agreed on the classification. Other items were newly added in order to encompass stress responses in all four categories. Four external experts examined and discussed the content validity of the new items as expressing stress responses and matching the relevant stress response categories. The final list included 66 items.

Step 2: Identifying the partition of stress responses

Participants..

The participants in Study 1 were first-year psychology undergraduate students at the Academic College of Tel Aviv-Yaffo. They participated in the study as part of their undergraduate program requirements and were recruited via the college’s credit database. A total of 100 participants enrolled in the study, with 91 fully completing the questionnaire. All 91 were first-year undergraduate students (84.6% female, 15.4% male) and the mean age was 23.56 years (SD = 1.37, range = 21–29).

The 66 selected items scale.

A short sociodemographic questionnaire including data on: age and gender.

The items were presented to the participants through the Qualtrics XM online platform. Participants were asked to recall a stressful event and to rate each response item on a scale ranging from “not at all” (1) to “always” (5) reflecting the extent to which each item characterize their response to stressful situations. All participants signed an electronic consent form before answering the questionnaires. The data was gathered and stored anonymously.

Data analysis.

In the first stage of analysis we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (principle component analyses with Varimax rotation) of all 66 items, which revealed four factors (eigenvalue>1.0), accounting for 48% of overall variance. We then screened the items and excluded 36 items based on both content analysis and factor loadings (items with loading< 0.5 were omitted) following two-step analyses. We ended with a final set of 30 items which we found as satisfying for our research purposes (hereinafter the 30 items scale).

In the second stage of analysis, we determined the number of factors according to the Kaiser criterion of eigenvalue> = 1 [ 28 ] and identified 7 factors accounting for 70.38% of the total variance. However, according to the scree plot, 3–4 factors could have been retained. We chose a conservative approach and determined 4 factors. The 4 factors accounted for 58.48% of the total variance.

Table 1 presents the factor loadings and descriptive statistics for each item. It is evident that items loaded on Factor 1 include mostly psychological (emotional and cognitive) responses (introversion, loneliness, confusion, etc.). Factor 2 items include mostly physiological-gastro responses (digestive upset, stomach pains, etc.). Factor 3 items include mostly physiological-muscular responses (neck and shoulder pain, backaches, etc.). Factor 4 items include mostly unregulated behavioral responses (temper flare-ups, nervousness, etc.). The item “physical unrest” was loaded on both Factor 1 and Factor 2.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255889.t001

We calculated a mean score for each factor. Factor 1, psychological, had the highest score (mean = 3.16; SD = 0.93; reliability Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.94, McDonalds Omega = 0.94), followed by Factor 4, behavioral, (mean = 3.13; SD = 0.89;reliability Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.84, McDonalds Omega = 0.84), and Factor 2, physiological-gastro, (mean = 2.56; SD = 1.00; reliability Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.65, McDonalds Omega = 0.67), and finally, Factor 3, physiological-muscular, (mean = 2.27; SD = 0.90; reliability: Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.77, McDonalds Omega = 0.79). Differences between all pairs of factors were significant except for Factor 3 vs. Factor 4.

In order to get further insight into the structure of the stress response items we conducted a smallest space analysis (SSA). SSA is a method of non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) in which a set of variables and their inter-correlations are geometrically portrayed in a multidimensional space [ 29 ]. SSA treats each variable (i.e., each questionnaire item) as a point in a Euclidean space—the higher the correlation between two variables, the closer the points in the space. It attempts to find the space with the minimum number of dimensions in which the rank order of relations is preserved. The regional partition of the SSA space can be studied in conjunction with the corresponding content of the mapped variables. All points within a region should be associated with a specific set of variables of the same content [ 30 – 33 ].

As can be seen, the SSA space in Fig 1 is partitioned into four polar (or angular) regions. Each polar region corresponds to one of the four categories—psychological, physiological-gastro, physiological-muscular, and behavioral—with their respective items. Polar regions divide the space into pie-shaped sections, all emanating from a common point. The elements of a polar facet are considered to be unordered but related [ 37 ]; they differ in kind but not necessarily in complexity. It should be noted that each two adjacent categories are close to each other in some respect.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255889.g001

Participants

Participants were people over 18 years old diagnosed with fibromyalgia (FM), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or both. Participants were recruited from four different online forums based in Israel—two of which were dedicated to IBS the rest to FM. All participants volunteered for the study and none were offered any compensation. A total of 217 participants enrolled in the study but only 143 completed the questionnaire. Amongst these, 62 participants reported having FM (43.35%), 45 reported having IBS (31.47%) and 36 reported having both IBS and FM (25.17%). 95.1% of all participants reported being officially diagnosed by a doctor. The reported mean time from diagnosis was 8.43 years (SD = 6.82). 129 were female (90.2%) and 14 were male (9.8%). This gender difference might be partially explained by the fact that both IBS and FM are more common in women worldwide. Mean age was M = 37.67 years SD = 13.2.

The 30 items scale (see Study 1 ).

A short sociodemographic questionnaire including data on: age, gender, diagnosis, time since diagnosis and who gave the diagnosis.

The items were presented to the participants through the Qualtrics XM online platform. Participants were asked to recall a stressful event and to rate each response item on a scale ranging from “not at all” (1) to “always” (5) reflecting the extent to which each item characterize their response to stressful situations. All participants signed an electronic consent form before answering the questionnaires. All data was gathered and stored anonymously.

Data analysis

We determined the number of factors according to the Kaiser criterion of eigenvalue> = 1 [ 36 ] and identified 7 factors accounting for 65.77% of the total variance. We identified 4–5 factors according to the scree plot. The fit to comparison data method (CD) revealed that the 4 factors solutions added significantly to the eigenvalue of 3 factors solution. Nevertheless, we decided on a conservative approach and we set the number of factors at 5. The 5 factors accounted for 58.01% of the total variance.

Table 2 presents the factor loadings and descriptive statistics for each item. Factor 1 included emotional responses identical to those included in factor 1 (psychological) in study 1. Three items that were included in this factor in study 1 (confusion, difficulty concentrating and attention dispersion) were now included in the additional factor 5 that consists of cognitive responses. Factor 2 included physiological- muscular items (identical to factor 3 in study 1) and the items insomnia and fatigue that were included in Factor 1 in study 1. Factor 3 included behavioural items and was identical to factor 4 in study 1. Factor 4 included physiological-gastro items, identical to the items included in Factor 2 in study 1 (except for the physical unrest item that in study 2 was included in Factor 1).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255889.t002

We calculated a mean score for each factor (see Table 2 ) there were no significant differences between the factors (largest difference was 0.0962). Factors reliability measures: Factor 1—Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.88, McDonalds Omega = 0.88; Factor 2—Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.82, McDonalds Omega = 0.83; Factor 3—Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.85, McDonalds Omega = 0.86; Factor 4—Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.74, McDonalds Omega = 0.75; Factor 5—Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.85, McDonalds Omega = 0.85.

In order to get further insight into the structure of the stress response items we conducted a smallest space analysis (SSA) similar to the SSA conducted in study 1.

As can be seen, the SSA space in Fig 2 is partitioned into five polar (or angular) regions. Each polar region corresponds to one of the five categories—emotional, physiological-gastro, physiological-muscular, behavioral and cognitive—with their respective items. Polar regions divide the space into pie-shaped sections, all emanating from a common point. The elements of a polar facet are considered to be unordered but related; they differ in kind but not necessarily in complexity. It should be noted that each two adjacent categories are close to each other in some respect.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255889.g002

Table 3 which presents comparisons of the 5 factors between the study groups of study 2 indicate that the IBS group reported on significantly lower levels of physiological-muscular distress in comparison to the other two groups. The IBS group reported significantly higher levels of physiological-gastro distress in comparison to the FM group. The IBS group was also found to be significantly lower in comparison to the other two groups on the cognitive factor.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255889.t003

Both the emotional and behavioral factors did not differ significantly between the groups.

In this study, we aimed to examine whether there are specific clusters of stress responses, representing interpersonal variation. More specifically, we hypothesized that different stress response clusters will reflect the different aspects of the known physiological, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive stress responses, thus allowing the identification of individual patterns.

The results obtained from Study 1 revealed four distinctive response categories: psychological (emotional and cognitive), physiological-gastro, physiological-muscular and behavioral. The psychological category entails mostly clinical symptoms of depression and anxiety as well as cognitive responses. Two of the categories are physiological responses: one mostly gastro-related symptoms and the other mostly muscle tension symptoms. The fourth category entails unregulated behaviors. The results obtained from Study 2 revealed five distinctive response categories: emotional, cognitive, physiological-gastro, physiological-muscular, and behavioral. As can be seen, the psychological category is divided into emotional and cognitive. These results thus portray an interesting classification that, if understood, may help to shed new light on stress response patterns and to highlight potential psychological and physiological susceptibilities.

It is already well established that psychological stress plays a role in negative physical and mental health conditions [ 20 , 34 – 36 ]. Thus, each of these response patterns may reflect a specific time point or dimension in the cascade of events vulnerability that may have a pathological outcome. For example, it was found that the link between stress and depression and anxiety is underlined by biological mechanisms such as HPA axis activation and inflammatory processes [ 37 ]. It can therefore be postulated that a person characterized by a high score in the emotional category may, in fact, be at risk of not only depression and anxiety disorder but also high cortisol-related illnesses. Such an assumption may be even more pronounced when an individual presents a high score in one or both of the physiological response categories. For instance, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) was found to be adversely affected by psychological stress via several possible biological pathways including gastrointestinal function [ 38 ]. The digestion-related symptoms characterizing the physiological-gastro category may therefore, indicate susceptibility to such illnesses.

As a result of these findings, we decided to proceed with a study testing whether stress responses in a sample of people suffering from the stress-related medical syndromes of fibromyalgia (FM), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or both (FM+IBS) will reflect our assumptions.

Our results (see Table 2 ) indicate that both the IBS and the FM+IBS groups reported experiencing physiological-gastro stress responses during stressful events more often than the FM group. We also found that both the FM and the FM+IBS groups reported experiencing physiological-muscular stress responses during stressful events more often than the IBS group.

These results are compatible with previous research findings regarding pain sensitivity patterns in these groups. Two-thirds of IBS patients have been found to have lower visceral pain thresholds [ 39 ], while their musculoskeletal pain thresholds are normal [ 40 ] or higher than in normal controls [ 41 ]. In contrast, FM patients have decreased musculoskeletal pain thresholds but normal visceral pain thresholds [ 42 , 43 ]. It appears that only the subgroup of patients who have both IBS and FM suffer both from visceral and somatic hypersensitivity [ 42 ]. However, we find that the direction of the correlation needs further study. For example, it is possible that people who have physiological-gastro responses to stress are more likely to develop IBS later, but it is also possible that people who already have IBS are more likely to respond to stress with gastrointestinal symptoms. We suggest that future longitudinal studies inspect the nature of this correlation.

We also found that both the FM and the FM+IBS groups reported experiencing emotional stress during stressful events more often than the IBS group. An earlier finding by Janssens, Zijlema, Joustra, and Rosmalen [ 44 ] that major depressive disorder is more common in FM than in IBS may explain our findings.

Conclusions

Our individual responses to stressful events embody much about who we are and what we have gone through. Our genetics, past experiences, gender, beliefs, and even smoking habits play a key role in how we react to stressors [ 19 , 45 – 47 ]. In mapping these reactions and patterns, we can obtain a clearer image of each person’s stress responses profile. A possible clinical implication of the findings of this study is the understanding that if we take into consideration the individual’s stress responses profile while planning stress management interventions and offer them a tailored intervention that reduces the intensity of these responses, we might prevent further complications resulting in physical or mental disease. Therefore, stress management interventions should be considered seriously and evidence based. An improved validated scale of stress responses may serve in the future as an important tool that will allow for the implementation of such tailored psychological interventions in various settings with minimal resources.

Limitations

Despite these important implications, there are some methodological limitations in the current study. First, the scale we have used for our research purposes is composed of items selected from previous scales and has not been validated. Second, the participants in study 2 (people who suffer from FM or IBS or both) differ from those of study 1 (students). Third, the majority of the participants were female, which might have led to a bias due to gender differences.

In addition, there are some theoretical concerns. Since our results are based on retrospective reports, participants may not accurately remember how they usually act and feel and may appraise how they have always responded to stress according to the salience of events rather than actual frequency. Previous research has suggested that people who suffer from chronic pain have an attention bias that makes pain more salient to them than it would be in normal controls (e.g., [ 48 ]). We therefore propose that future studies use a daily log of stressful events and subsequent stress reactions in order to circumvent possible memory biases.

Another major challenge is differentiating between stress responses and stress coping strategies. Some theorists have even preferred to limit the concept of coping to voluntary responses [ 49 ], while others have included automatic and involuntary responses as well [ 50 , 51 ]. However, it is difficult to distinguish between voluntary and involuntary responses—if “volition” even exists at all. Libet [ 52 ] posited that if volition does indeed exist, it is only expressed when we use a conscious effort to think or behave differently than we are used to. Furthermore, thoughts and behaviors that are intentional and effortful when first used may, he claimed, become automatic and involuntary with repetition.

These limitations notwithstanding, our study calls for a detailed observation of the components of the existing stress models, focusing specifically on the function of stress responses and their impact on health while implementing tailored interventions that take into consideration individuals’ specific response clusters.

- 1. Selye H. The Stress of Life. Hans Selye. MD New York, McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. 1956:479.

- 2. Cannon WB. The wisdom of the body. 1939.

- 3. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping: Springer publishing company; 1984.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 5. Sapolsky RM. Why zebras don’t get ulcers: The acclaimed guide to stress, stress-related diseases, and coping: Holt paperbacks; 2004.

- 7. Jaremko M, Meichenbaum D. Stress reduction and prevention: Springer Science & Business Media; 2013.

- 11. Darwin C. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Chicago (University of Chicago Press) 1965. 1965.

- 26. Taylor SE. Health psychology: Tata McGraw-Hill Education; 2006.

- 30. Brown J. An introduction to the uses of facet theory. Facet theory: Springer; 1985. p. 17–57.

- 32. Canter D. An introduction to the uses of facet theory. Facet theory approaches to social research: Springer; 1985. p. 18–57.

- 33. Borg IS, Samuel . Facet Theory: Form and Content: 5 (Advanced Quantitative Techniques in the Social Sciences),. CA: Sage: Newbury Park; 1995.

- 35. Hjemdahl P, Rosengren A, Steptoe A. Stress and cardiovascular disease: Springer Science & Business Media; 2011.

- 50. Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK. Coping with stress. Handbook of children’s coping: Springer; 1997. p. 41–70.

- Open access

- Published: 24 February 2024

Physical activity improves stress load, recovery, and academic performance-related parameters among university students: a longitudinal study on daily level

- Monika Teuber 1 ,

- Daniel Leyhr 1 , 2 &

- Gorden Sudeck 1 , 3

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 598 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

4094 Accesses

30 Altmetric

Metrics details

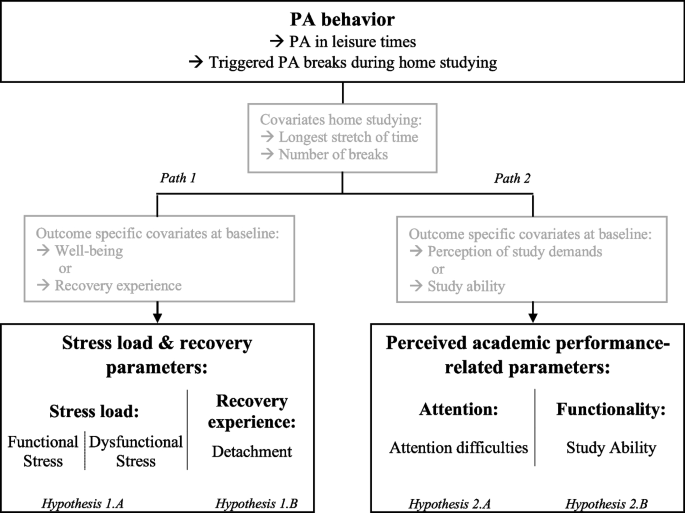

Physical activity has been proven to be beneficial for physical and psychological health as well as for academic achievement. However, especially university students are insufficiently physically active because of difficulties in time management regarding study, work, and social demands. As they are at a crucial life stage, it is of interest how physical activity affects university students' stress load and recovery as well as their academic performance.

Student´s behavior during home studying in times of COVID-19 was examined longitudinally on a daily basis during a ten-day study period ( N = 57, aged M = 23.5 years, SD = 2.8, studying between the 1st to 13th semester ( M = 5.8, SD = 4.1)). Two-level regression models were conducted to predict daily variations in stress load, recovery and perceived academic performance depending on leisure-time physical activity and short physical activity breaks during studying periods. Parameters of the individual home studying behavior were also taken into account as covariates.

While physical activity breaks only positively affect stress load (functional stress b = 0.032, p < 0.01) and perceived academic performance (b = 0.121, p < 0.001), leisure-time physical activity affects parameters of stress load (functional stress: b = 0.003, p < 0.001, dysfunctional stress: b = -0.002, p < 0.01), recovery experience (b = -0.003, p < 0.001) and perceived academic performance (b = 0.012, p < 0.001). Home study behavior regarding the number of breaks and longest stretch of time also shows associations with recovery experience and perceived academic performance.

Conclusions

Study results confirm the importance of different physical activities for university students` stress load, recovery experience and perceived academic performance in home studying periods. Universities should promote physical activity to keep their students healthy and capable of performing well in academic study: On the one hand, they can offer opportunities to be physically active in leisure time. On the other hand, they can support physical activity breaks during the learning process and in the immediate location of study.

Peer Review reports

Introduction