ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, how to help middle school students develop research skills.

As the research skills you teach middle school students can last them all their lives, it’s essential to help them develop good habits early in their school careers.

Research skills are useful in nearly every subject, whether it’s English, math, social studies or science, and they will continue to pay off for students every day of their schooling. Understanding the most important research skills that middle school students need will help reach these kids and make a long-term difference.

The research process

It is important for every student to understand that research is actually a process rather than something that happens naturally. The best researchers develop a process that allows them to fully comprehend the ideas they are researching and also turn the data into information that is usable for whatever the end purpose may be. Here is an example of a research process that you may consider using when teaching research skills in your middle school classroom:

- Form a question : Research should be targeted; develop a question you want to answer before progressing any further.

- Decide on resources : Not every resource is good for every question/problem. Identify the resources that will work best for you.

- Gather raw data : First, gather information in its rawest form; do not attempt to make sense of it at this point.

- Sort the data : After you have the information in front of you, decide what is important to you and how you will use it. Not all data will be reliable or worthwhile.

- Process information : Turn the data into usable information. This processing step may take longer than the rest combined. This is where you really see your data shape into something exciting.

- Create a final piece : This is where you would write a research paper, create a project or build a graph or other visual piece with your information. This may or may not be a formal document.

- Evaluate : Look back on the process. Where did you experience success and failure? Did you find an answer to your question?

This process can be adjusted to suit the needs of your particular classroom or the project you are working on. Just remember that the goal is not only to find the data for this particular project, but to teach your students research skills that will help them in the long run.

Research is a very important part of the learning process as well as being useful in real-life once the student graduates. Middle school is a great time to develop these skills as many high school teachers expect that students already have this knowledge.

Students who are well-prepared as researchers will be able to handle nearly any assignment that comes their way. Finding new ways to teach research skills to middle school students need will be a challenge, but the results are well worth it as you see your students succeed in your classroom and set the stage for further success throughout their schooling experience.

You may also like to read

- Web Research Skills: Teaching Your Students the Fundamentals

- Building Math Skills in High School Students

- How to Help High School Students with Career Research

- Five Free Websites for Students to Build Research Skills

- Homework in Middle School: Building a Foundation for Study Skills

- 5 Novels for Middle School Students that Celebrate Diversity

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

Tagged as: Engaging Activities , Middle School (Grades: 6-8)

- Math Teaching Resources | Classroom Activitie...

- Online & Campus Doctorate (EdD) in Organizati...

- Master's in Reading and Literacy Education

Summer II 2024 Application Deadline is June 26, 2024.

Click here to apply.

Featured Posts

Pace University's Pre-College Program: Our Honest Review

Building a College Portfolio? Here are 8 Things You Should Know

Should You Apply to Catapult Incubator as a High Schooler?

8 Criminal Justice Internships for High School Students

10 Reasons to Apply to Scripps' Research Internship for High School Students

10 Free Business Programs for High School Students

Spike Lab - Is It a Worthwhile Incubator Program for High School Students?

10 Business Programs for High School Students in NYC

11 Summer Film Programs for High School Students

10 Photography Internships for High School Students

10 Great Research Topics for Middle School Students

Middle school is the perfect time to start exploring the fascinating world of research, especially if you're passionate about STEM and the humanities. Engaging in research projects now not only feeds your curiosity but also develops critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and a love for learning. Whether you're intrigued by the secrets of the universe, the beauty of numbers, or the complexity of robotics, there's a research project that you can pursue to help you build your knowledge. Let's dive into some advanced yet accessible research topics that will challenge you and enhance your academic journey.

1. Program your own robot

What to do: Start by defining the purpose of your robot. Will it be a pet robot that follows you around, or perhaps a robot that can help carry small items from one room to another? Sketch your design on paper, focusing on what sensors and motors you'll need. For instance, a robot that follows light might need light sensors, while a robot that avoids obstacles will require ultrasonic sensors. Use an Arduino or Raspberry Pi as the brain. You'll need to learn basic programming in Python (for Raspberry Pi) or C++ (for Arduino) to code your robot's behavior.

Tips to get started: The official websites for Arduino and Raspberry Pi offer tutorials for beginners. For more specific projects, such as building a pet robot, search for guides on Instructables that detail each step from hardware assembly to software programming.

2. Design a solar-powered oven

What to do: Investigate how solar ovens work and the science behind solar cooking. Your oven can be as simple as a pizza box solar oven or more complex, like a parabolic solar cooker. Key materials include reflective surfaces (aluminum foil), clear plastic wrap to create a greenhouse effect, and black construction paper to absorb heat. Experiment with different shapes and angles to maximize the heat capture and cooking efficiency. Test your oven by trying to cook different foods and measure the temperature achieved and cooking time required.

Tips to get started: The Solar Cooking wiki is an excellent resource for finding different solar cooker designs and construction plans. YouTube also has numerous DIY solar oven tutorials. Document your process and results in a project journal, noting any changes in design that lead to improvements in efficiency.

3. Assess the health of a local ecosystem

What to do: Choose a local natural area, such as a stream, pond, or forest, and plan a series of observations and tests to assess its health. Key activities could include water quality testing (for pH, nitrates, and phosphates), soil testing (for composition and contaminants), and biodiversity surveys (identifying species of plants and animals present). Compile your data to evaluate the ecosystem's health, looking for signs of pollution, habitat destruction, or invasive species.

Tips to get started: For a comprehensive approach, NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory provides information on atmospheric and environmental monitoring techniques. Tools like iNaturalist can assist in species identification, and water and soil testing kits are available from science education suppliers.

4. Develop an educational app

What to do: Identify a gap in educational resources that your app could fill. Perhaps you noticed that students struggle with a particular math concept, or there's a lack of engaging resources for learning a foreign language. Outline your app’s features, design the user interface, and plan the content it will deliver. Use MIT App Inventor for a drag-and-drop development experience, or Scratch for a game-like educational app. Test your app with classmates or family members, and use their feedback for improvements.

Tips to get started: Both MIT App Inventor and Scratch provide tutorials and community forums where you can learn from others’ projects. Begin with a simple prototype, focusing on one core feature, and expand from there.

5. Model rocketry: design, build, and launch!

What to do: Dive into the basics of rocket science by designing your own model rocket. Understand the principles of thrust, aerodynamics, and stability as you plan your rocket. Materials can range from simple kits available online to homemade components for the body, fins, and nose cone. Educate yourself on the proper engine selection for your design and the recovery system to ensure your rocket returns safely. Conduct a launch in a safe, open area, following all safety guidelines.

Tips to get started: The National Association of Rocketry is a treasure trove of information on model rocket safety, design, and launch procedures. For beginners, consider starting with a kit from Estes Rockets , which includes all necessary components and instructions.

6. Create a wearable electronic device

What to do: Envision a wearable device that solves a problem or enhances an aspect of daily life. It could be a smart bracelet that reminds you to stay hydrated or a hat with integrated LEDs for nighttime visibility. Sketch your design, listing the components you'll need, such as LEDs, sensors, a power source, and a microcontroller like the Adafruit Flora or Gemma. Plan your circuit, sew or assemble your device, and program it to function as intended.

Tips to get started: Adafruit’s Wearables section offers guides and tutorials for numerous wearable projects, including coding and circuit design. Start with a simple project to familiarize yourself with electronics and sewing conductive thread before moving on to more complex designs.

7. Explore the science of slime and non-Newtonian fluids

What to do: Conduct experiments to understand how the composition of slime affects its properties. Create a standard slime recipe using glue, borax (or contact lens solution as a safer alternative), and water. Alter the recipe by varying the amounts of each ingredient or adding additives like cornstarch, shaving cream, or thermochromic pigment. Test how each variation affects the slime’s viscosity, stretchiness, and reaction to pressure.

Tips to get started: The Science Bob website offers a basic slime recipe and the science behind it. Document each experiment carefully, noting the recipe used and the observed properties. This will help you understand the science behind non-Newtonian fluids.

8. Extract DNA at home

What to do: Use common household items to extract DNA from fruits or vegetables, like strawberries or onions. The basic process involves mashing the fruit, adding a mixture of water, salt, and dish soap to break down cell membranes, and then using cold alcohol to precipitate the DNA out of the solution. Observe and analyze the DNA strands.

Tips to get started: Detailed instructions and the science explanation are available at the Genetic Science Learning Center . This project offers a tangible glimpse into the molecular basis of life and can be a springboard to more complex biotechnology experiments.

9. Investigate the efficiency of different types of solar cells

What to do: Compare the efficiency of various solar panels, such as monocrystalline, polycrystalline, and thin-film. Design an experiment to measure the electrical output of each type under identical lighting conditions, using a multimeter to record voltage and current. Analyze how factors like angle of incidence, light intensity, and temperature affect their performance.

Tips to get started: Introductory resources on solar energy and experiments can be found at the Energy.gov website. Consider purchasing small solar panels of different types from electronics stores or online suppliers. Ensure that all tests are conducted under controlled conditions for accurate comparisons.

10. Study ocean acidification and its effects on marine life

What to do: Simulate the effects of ocean acidification on marine organisms in a controlled experiment. Use vinegar to lower the pH of water in a tank and observe its impact on calcium carbonate shells or skeletons, such as seashells or coral fragments. Monitor and record changes over time, researching how acidification affects the ability of these organisms to maintain their shells and skeletons.

Tips to get started: NOAA’s Ocean Acidification Program offers educational materials and experiment ideas. For a simpler version of this experiment, see instructions for observing the effects of acidified water on eggshells, which are similar in composition to marine shells, at educational websites like Science Buddies .

By pursuing these projects, you will not only gain a deeper understanding of STEM principles but also develop invaluable skills in research, design, and critical analysis. These projects will teach you how to question, experiment, and innovate, laying the groundwork for future scientific inquiries and discoveries.

One other option – Lumiere’s Junior Explorer Program

The Lumiere Junior Explorer Program is a program for middle school students to work one-on-one with a mentor to explore their academic interests and build a project they are passionate about . Our mentors are scholars from top research universities such as Harvard, MIT, Stanford, Yale, Duke and LSE.

The program was founded by a Harvard & Oxford PhD who met as undergraduates at Harvard. The program is rigorous and fully virtual. We offer need based financial aid for students who qualify. You can find the application in the brochure !

To learn more, you can reach out to our Head of Growth, Khushi Malde, at [email protected] or go to our website .

Multiple rolling deadlines for JEP cohorts across the year, you can apply using this application link ! If you'd like to take a look at the cohorts + deadlines for 2024, you can refer to this page!

Stephen is one of the founders of Lumiere and a Harvard College graduate. He founded Lumiere as a PhD student at Harvard Business School. Lumiere is a selective research program where students work 1-1 with a research mentor to develop an independent research paper.

- middle school students

Top Research strategies for Students

What are the essential research strategies for students?

Not so long ago, accessing information required legwork. Actual legwork in the form of actually walking to the library and searching through the numerous books organized using an archaic system called the Dewey Decimal System.

Things are much less complicated these days. In this wired age, accessing information is as simple as pressing a few buttons on a laptop or swiping your finger across a cell phone screen.

While this 24/7 online access to information represents impressive progress, we still need to ensure our students develop the necessary research skills and strategies that allow them to access the correct information, evaluate it for accuracy, and then plan for its use in our own work accordingly – whatever the student’s age.

In this article, we will look at solid research skills that will benefit students of all ages. Some of these are evergreen old-school strategies, while others are shiny new. Regardless, each is designed to help students from elementary through to high school make the most of the information to research effectively.

The skills described below represent the essential skills and strategies our students will require. They can begin to develop these in elementary school and build on those foundations as they progress through middle school and high school.

After examining these skills, we provide you with a series of activities organized hierarchically and categorized according to the approximate school stage they correspond to. These can also be dipped into and mixed and matched according to the particular abilities of your specific students.

COMPLETE TEACHING UNIT ON INTERNET RESEARCH SKILLS USING GOOGLE SEARCH

Teach your students ESSENTIAL SKILLS OF THE INFORMATION ERA to become expert DIGITAL RESEARCHERS.

⭐How to correctly ask questions to search engines on all devices.

⭐ How to filter and refine your results to find exactly what you want every time.

⭐ Essential Research and critical thinking skills for students.

⭐ Plagiarism, Citing and acknowledging other people’s work.

⭐ How to query, synthesize and record your findings logically.

Online Research Strategies

Research is essential to the writing process ; students will stumble at the first hurdle without the necessary skills. Research skills help students locate the required relevant information and evaluate its reliability. Developing excellent research skills ultimately enables students to become their teachers.

Let’s now look at the most important of these research skills.

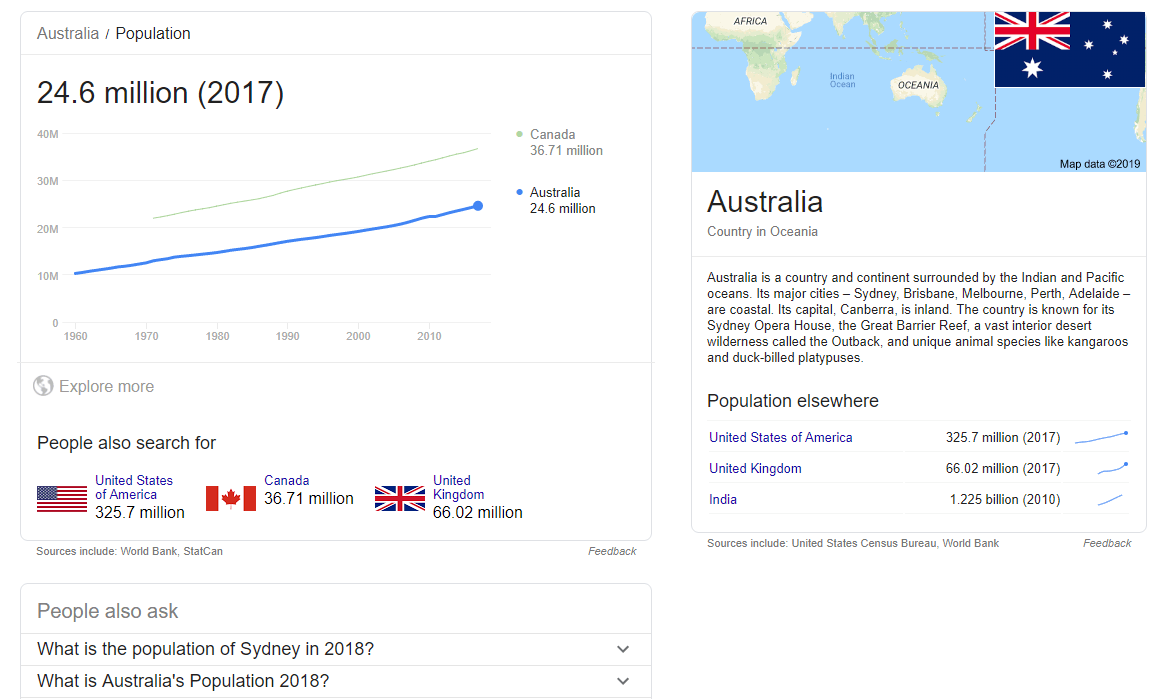

Research Tip # 1. Use Search Engine Shortcuts

Good research begins with asking good questions. This also applies to employing search engines, such as Google , DuckDuckGo , and Yahoo, effectively.

The Internet is an almost inexhaustible collection of information and is constantly growing. Search engines are a tool that helps us filter that information down to the exact piece of knowledge we are seeking. This is achieved primarily through the careful selection of search terms. The specificity of the search terms used is key to successfully navigating the immense ocean of information available on the ’net.

The more refined our search queries are, the more likely the search engine will return relevant information to us and the less time we will waste in the process.

As Google is the most popular search engine out there, here are some quick tips to ensure you and your students are getting the most out of your Google searches. However, note that many of these strategies also work on other search engines.

- Use Quotation Marks

Placing your search terms inside quotation marks (“”) ensures Google searches for the whole phrase, not just occurrences of the individual words in the phrase. This minimizes guesswork on the part of Google and ensures only the most relevant pages are returned to you.

- Exclude Words with a Hyphen

English contains a lot of ambiguity. While this is great for the poets among us, it can make researching some terms problematic. For example, if you search for the term ‘ toast ’ meaning speech, you may also get many results related to the much-loved breakfast staple. Simply type ‘ toast -breakfast’ into the search bar to remove results related to this meaning. This tells Google only to return results including ‘toast’ and to exclude those results also containing the term ‘breakfast.’

- Search a Specific Site

Sometimes we come across a site that is a real treasure trove of information but where information is poorly indexed on the site menus. Luckily, there is a way to search the content on a specific site. To do this, simply type the search terms into the search bar followed by ‘ site: ’ and then the particular site URL. For example, if we wanted to search the Literacy Ideas website for mentions of the term ‘ Visual Literacy ’, we would enter:

visual literacy site:literacyideas.com

We highly recommend this resource for using Google search as a research tool with students. It is very comprehensive.

Research Tip # 2. Check Your Sources

The popular Internet meme quoting Abraham Lincoln states, “Don’t believe everything you read on the Internet.”

In this era of Fake News, we are constantly reminded of the unreliability of much of the information presented as truth on the web . We (and our students) must have some strategies to assess the accuracy and validity of the information we come across.

A good starting point is to ask yourself the following questions when assessing new information:

● Is this information up-to-date?

● Is this information detailed?

● Is the author identified?

● Is the author qualified on the topic?

● Are sources cited?

● Does the information come from a trusted source?

A Complete Teaching Unit on Fake News

Digital and social media have completely redefined the media landscape, making it difficult for students to identify FACTS AND OPINIONS covering:

Teach them to FIGHT FAKE NEWS with this COMPLETE 42 PAGE UNIT. No preparation is required,

Research Tip # 3. Select Domains Wisely

When searching, encourage students to consider the importance of domains, such as .com , .org , . gov , and . edu . These are not all created equally. For example, .com and .org domains are classed as ‘open,’ meaning anyone can register on them. They are usually used for commercial reasons.

Other domains are classed as ‘closed,’ such as .gov and .edu , and registrants must meet specific eligibility requirements to register these. For example, in the case of .edu , registration is limited to accredited post-secondary institutions in the United States.

Depending on the purpose of your search, the domain you choose to search may have implications for the reliability and usefulness of the results returned.

To choose which type of domain to search, type ‘site’, followed by a colon, and then the domain after your chosen search terms.

For example, if you wish to search for the term ‘ American presidents ’ on .edu sites, simply type:

American presidents site:edu

Research Tip # 4. Citation

One downside of the widespread instant and free availability of information on the Internet is the erosion of intellectual property rights and the inevitable increase in plagiarism.

To combat this, we must ensure our students avoid plagiarism and respect copyright rights by adequately citing sources used.

When engaged in writing essays , students should be familiar with how to use quotation marks, compile notes, and structure a bibliography. When citing online sources, they should also be familiar with the conventions related to citing URLs.

Just how detailed citations are will depend mainly on the age and ability of the students in question.

Many excellent free online resources help to format citations correctly, some of which can automatically create formatted citations. For example, Citation Machine and Citation Builder provide this service. Google Docs also has an add-on feature that automatically generates bibliographies and footnotes according to various citation styles, e.g., Chicago, APA, MLA, etc.

Teaching Resources

Use our resources and tools to improve your student’s writing skills through proven teaching strategies.

Research Skills Activities

Elementary School Students

Providing a basic overview of the various research strategies is sufficient for this age group.

Discussions about what research is and why we do it are excellent places to start developing research skills.

These discussions will open up possibilities for students to acquire the necessary vocabulary to develop research skills.

Some topics and areas to focus these discussions on could include:

- How to ask questions about simple research topics

- The concept of keywords – what are they, and how do they work?

- A general overview of search engines, e.g., Google, DuckDuckGo, Bing, Yahoo

- A basic explanation of sources

- Simple note-taking skills

- Researching in the library the “old school” way

Elementary Practice Activities

- Individual Research Project

Ask the students to choose their favorite animal for a class presentation at the end. Students can start by generating research questions to fuel their investigations. Areas they might want to look at could include habitat, life cycle, population numbers, diet, etc.

- Collaborative Hands-On Research

This activity allows the students to engage in basic ‘hands-on’ research on the Internet. This will allow them to practice using keyword search terms to locate helpful information.

Organize the students into ‘research groups’ and provide the groups with a simple topic and a list of questions to research online. For example, the topic might be The Solar System, and some questions they might research could include:

- How many planets are in the solar system?

- What is the name of the closest planet to the sun?

- Which is the most giant planet in the solar system?

- Which is the smallest?

- How many moons does Jupiter have?

- How long does it take for Venus to orbit the sun?

- What is the name of the planet furthest from the sun?

The winning team will be the team to find all the correct answers the quickest.

- Class Project

Another variation of the individual research project is to do a whole class project on a larger scale. For example, students could choose a favorite holiday, such as Christmas, Thanksgiving, Eid, Hanukkah, Chinese New Year, etc., and research multiple aspects of it. For example:

- What are the roots of this festival?

- What is its significance?

- What types of gifts are given?

- What food is associated with this holiday?

- Are certain clothes, customs, or traditions associated with it?

The findings of this research could form classroom displays, presentations, exhibits, etc.

Middle School Students

Students are ready to begin using more sophisticated research skills and strategies at this age. Some things to focus on with middle school-aged students include:

- A more detailed explanation of sources and how to determine their credibility

- Examination of online encyclopedias such as Wikipedia – explore how they may not always be reliable but can be a good resource for locating other more credible sources.

- The use of domains such “edu” “org” “gov” and how they can be used to identify sources

- Practice using simple shortcuts that can be used when searching online

- Discussions on planning and keeping organized notes, e.g., journals, checklists, templates, etc.

Middle School Practice Activities

- Information Recording

As students begin dealing with more complex and larger volumes of information, they’ll need to develop strategies to help them condense and record information for later use in the writing process.

To help them develop this skill, set the students a how-to research task. Choose a task suited to your students’ ages and abilities, for example, anything from How to Bake Cookies to How to Construct a Bridge .

This is an opportunity for your students to develop their note-taking abilities helping them record the important information from their research activities. You may also want them to make visualizations such as diagrams, infographics, and charts, which are valuable techniques for recording the fruits of the research labor.

- Group Project

Organize students into suitably sized groups and provide them with a topic to investigate. Countries work well. Each group will assign a team member to research a specific aspect of their country, and they will pool their findings at the end to develop a presentation or classroom display. Some aspects worthy of research may include:

- Customs and traditions

- Tourist attractions

High School Students

At this stage, the focus moves on from merely finding sources of information to actually processing them. Here, the students should be encouraged to engage more closely with what their research uncovers and begin to dig beneath the surface to evaluate material and sources more critically.

To develop these abilities, students will need to:

- Begin asking more probing questions to initiate their research

- Examine the sources of information more critically

- Become more precise and methodical in choosing search criteria

- Use multiple resources – online, news articles, documentaries, podcasts, youtube

- Keep records of sites visited and books, journals, and articles referred to for citation later

- Cite sources correctly

- quotation marks for searching exact phrases/words

- minus symbol(-) for excluding certain words

- asterisk(*) used to broaden a search by finding words that begin with the same stem

- “site” for site-specific search

- Evaluate sources for reliability, relevance, accuracy, and how current they are

- Develop more organized note-taking methods – focus on quality over quantity

- Plan effectively – utilize strategies to compile information that will help in the final presentation of findings.

High School Practice Activities

- Develop Research Questions

As students learn to deal with the increasing breadth and complexity of research topics, they’ll need to know how to narrow their focus by developing more specific research questions.

This activity provides students with a list of topics to choose from; this can be an excellent opportunity for forging cross-curricular links. For example, you might suggest history or physical education topics, such as The Vietnam War or Cardiovascular Exercise .

Then, ask students to choose a topic and develop research questions on it for aspects they would like to explore further. For example, they might ask questions like How did the Vietnam War start? Or, What effect does cardiovascular exercise have on mood?

Students can then research the answers to their most interesting research questions and share their findings with the class.

- Hold a Debate

Debates are a great way to illustrate the power of research in practical terms – and they are a lot of fun to boot!

In this activity, organize students into debating groups of three. Assign each pair of groups a debate motion and a position. Students will then need to go away and research their topic thoroughly before writing their speeches and delivering their arguments. To learn more about preparing a debate-winning speech, check out our article here .

Research Strategies

“A goal without a plan is just a wish.”

So, what do students do with all these finally-tuned research skills now at their fingertips?

If the boy scouts have taught us anything, it is essential to be prepared. To that end, let’s look at planning strategies to help students get the most from their well-honed research skills.

1. Collaboration

In our rapidly changing world, it is impossible to accurately predict the nature of the jobs our students will undertake in the future.

However, what does seem sure is that the so-called soft skills , which are transferable between jobs, will be much in demand in the working world of tomorrow. Collaboration is one of these important skills.

Collaboration involves working together to achieve a common goal. It promotes high levels of interaction and communication between students and colleagues. Collaboration exposes each individual to diverse perspectives and encourages higher-level thinking. Incorporating collaboration at the planning stage helps ensure the success of teaching and learning projects.

2. The Round Robin

Brainstorming is a tried and tested means of beginning the planning process. There are many variations in brainstorming techniques. The Round Robin , which we will look at here, lends itself well to our previous collaboration strategy.

In the Round Robin , the students sit in a circle to discuss the topic.

One by one, go around the circle, encouraging each student to share one idea until everyone has had a chance to speak. While this happens, an appointed person can keep a record of each shared idea.

Ideas must be shared first without initial discussion or criticism. Evaluation and debate should occur only after each person has had an opportunity to share their ideas.

This is an excellent strategy to ensure each person has had an opportunity to share their ideas. It also avoids any one voice dominating a collaborative planning session.

3. The Mind Map

Mind Maps are simply diagrams that visually represent ideas. They can be done individually or collaboratively using words, pictures, or both.

With much in common with brainstorming, Mind Maps are an excellent way to begin the planning process, as they are a superb means of organizing complex ideas.

Many people use paper and pens to create Mind Maps for their projects. However, people are increasingly turning to technology to help their development. There are now many paid and free options online, providing templates and tools to help you develop your own Mind Maps .

4. Use an Online Calendar

Homework deadlines. Exam timetables. College applications. The demands on students and teachers alike are many and varied. It may, at times, seem impossible to keep track of everything.

Using an online calendar, such as those pre-installed on many cell phones, helps ensure you keep track of your to-do list, and many will even provide regular reminders as those deadlines loom near.

5. Create Checklists

Not only are checklists a great way to ensure you have fulfilled all the criteria of a given task, but they are also an effective means of planning out all the points you need to hit to complete a project successfully.

A good checklist should contain all the essential elements for a successful piece of work. When the descriptions of these items are kept generic rather than detailed and specific, they can serve as templates for a particular genre to be reused each time your students engage in that type of work.

Research Thoroughly. Implement Effectively!

Research skills are the bridge between the idea and its implementation in writing. The more students develop their research skills, the more authoritative their writing will become. With practice, these two sides of the blade will become razor-sharp.

A COMPLETE DIGITAL READING UNIT FOR STUDENTS

Over 30 engaging activities for students to complete BEFORE, DURING and AFTER reading ANY BOOK

- Compatible with all devices and digital platforms, including GOOGLE CLASSROOM.

- Fun, Engaging, Open-Ended INDEPENDENT tasks.

- 20+ 5-Star Ratings ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Useful research strategIES video TUTORIALS

OTHER GREAT ARTICLES TO SUPPORT RESEARCH SKILLS

6 Ways To Identify Fake News: A Complete Guide for Educators

The Writing Process

How to Write an Article

How to Write a Biography

Breaking News

Crafting The Future: An Inside Look at Marshalls High School in Los Angeles

Inclusive Relationship Meaning: Understanding the Concept

How to Get Out of School Excuses

Best Homeschool Curriculum for Autism: A Comprehensive Guide for Parents and Educators

Exciting Research Topics for Middle Schoolers to Fuel Curiosity

Working on the phonological skills by teaching phonemic awareness to the advanced level

What is the goal when de escalating crisis behavior at school ?

Middle school is a time of burgeoning curiosity and the perfect opportunity for students to engage in research that not only educates them academically but also cultivates skills for the future. By encouraging young learners to explore topics they are passionate about, educators and parents play a pivotal role in their intellectual development and the growth of their intrinsic motivation. This blog post outlines a diverse range of research topics suited to the inquiring minds of middle school students, giving them the freedom to deepen their understanding of various subjects while honing critical thinking and independent study skills.

Uncovering the Mysteries of History

Middle schoolers often find history fascinating, particularly when learning about the past from distinct perspectives. Here are some intriguing historical research topics to consider:

- The Unsung Heroes of the Civil Rights Movement: Apart from the well-known leaders, students can explore the contributions of lesser-known figures who played a significant role in the struggle for equality.

- The Impact of Ancient Civilizations on Modern Society: Researching the ways in which the Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, or other ancient societies have influenced contemporary culture, politics, and technology offers a broad canvas for exploration.

- Everyday Life in Different Historical Periods: Focusing on the routines, customs, and technologies that shaped people’s daily lives in times gone by can provide valuable insights into societal norms and individual experiences.

Science and the Natural World

The sciences are a playground of wonder, with an infinity of topics waiting to be explored. Here are some research ideas that can nurture a love for discovery and experimentation:

- Climate Change: Effects and Solutions: Investigating the causes and potential solutions to this global challenge can make students aware of their role in protecting the planet.

- The Wonders of the Solar System: Encouraging a study of the planets, their moons, and the vast expanse of space they inhabit can ignite dreams of interstellar exploration.

- Biodiversity and Ecosystem Conservation: Researching the variety of life on Earth and strategies to protect and sustain ecosystems can foster a sense of environmental stewardship.

Literature, Language, and Creative Expression

Language and literature are potent forms of human expression, allowing students to explore complex ideas and emotions. Here are some topics that bridge the gap between art and academia:

- Interpreting Classic Literature for Modern Relevance: Encouraging the study of timeless works can lead to discussions on their contemporary significance and the evolution of societal values.

- The Structure and Evolution of Language: Investigating the origins and changes in language over time can be a rich area of study, especially when paired with the examination of cultural shifts.

- The Intersection of Art and Literature: Exploring how visual arts and writing intersect to convey messages and emotions can be a fertile ground for interdisciplinary research.

Mathematics and Logic Puzzles

The precision and patterns found in mathematics can be both satisfying and thought-provoking. Middle school students often enjoy the thrill of solving problems and unraveling puzzles. Here are some mathematical research topics that can engage students’ analytical minds:

- Famous Mathematical Conjectures: Researching unsolved problems, such as the Goldbach conjecture or the Riemann hypothesis, can introduce students to the excitement of open questions in mathematics.

- The Application of Math in Various Industries: Investigating how mathematical principles underpin fields like music, art, sports, and technology can illuminate the subject’s real-world utility.

- The History of Mathematical Discoveries: Tracing the lineage of mathematical concepts through different cultures and periods can showcase the universality and timelessness of mathematics.

Social Sciences and Human Interaction

Studying human behavior and society can help students develop empathy and a deeper understanding of the world around them. Here are some social science research ideas to explore:

- The Impact of Social Media on Friendships and Relationships: Research could focus on positive and negative effects, trends, and the future of social interaction.

- Cultural Traditions and Their Meanings: Investigating the origins and contemporary significance of customs from various cultures can foster respect for diversity and a global perspective.

- The Psychology of Decision Making: Exploring the factors that influence human choices, from cognitive biases to social pressures, can provide insights into individual and collective behavior.

Technology and Innovation

Middle schoolers are often tech-savvy and interested in the latest gadgets and advancements. Here are some technology and innovation research topics to tap into that curiosity:

- The Impact of Gaming on Society: Research could examine how video games influence education, social issues, or even career choices.

- Emerging Technologies and Their Ethical Implications: Encouraging students to study technologies like artificial intelligence, gene editing, or wearable tech can lead to discussions on the ethical considerations of their use and development.

- Inventions That Changed the World: Chronicling the history and influence of significant inventions, from the wheel to the internet, can provide a lens through which to view human progress.

By providing middle schoolers with the opportunity to conduct meaningful research in a topic of their choosing, we not only deepen their education but also equip them with the skills and passion for a lifetime of learning. This list is just the beginning; the key is to foster curiosity and guide young minds toward engaging, challenging, and diverse research experiences. Through such explorations, we empower the next generation to think critically, communicate effectively, and, most importantly, to nurture their innate curiosity about the world.

Implementing Research Projects in the Classroom

Encouraging middle school students to undertake research projects requires a strategic approach to ensure sustained interest and meaningful outcomes. Here are some methods educators can employ:

- Mentorship and Support: Pairing students with teacher mentors who can guide them through the research process, provide feedback, and encourage critical thinking is essential for a fruitful research experience.

- Cross-Curricular Integration: Linking research topics to content from different subjects helps students appreciate the interconnectedness of knowledge and develop versatile learning skills.

- Use of Technology and Media: Incorporating digital tools for research, presentation, and collaboration can enhance engagement and teach essential 21st-century skills.

- Presentation and Reflection: Allocating time for students to present their findings nurtures communication skills and confidence, while self-reflection activities help them internalize their learning journey.

These strategies can create a robust framework within which students can pursue their curiosities, leading to a more personalized and impactful educational experience.

What is a good topic to research for middle school?

A good topic for middle school research could delve into the Role of Robotics in the Future of Society . Students can explore how robotics may transform jobs, healthcare, and everyday life. They can examine the balance between automation and human work, predict how robots could augment human abilities, and discuss the ethical dimensions of a robotic future. This inquiry not only captivates the imagination but also encourages critical thinking about technology’s impact on tomorrow’s world.

What are the 10 research titles examples?

- The Evolution of Renewable Energy and Its Future Prospects

- Investigating the Effects of Microplastics on Marine Ecosystems

- The Influence of Ancient Civilizations on Modern Democracy

- Understanding Black Holes: Unveiling the Mysteries of the Cosmos

- The Impact of Augmented Reality on Education and Training

- Climate Change and Its Consequences on Coastal Cities

- The Psychological Effects of Social Media on Teenagers

- Genetic Engineering: The Possibilities and Pitfalls

- Smart Cities: How Technology is Shaping Urban Living

- The Role of Nanotechnology in Medicine: Current Applications and Future Potential

Fascinating Facts About Middle School Research Topics

- Interdisciplinary Impact : Research projects in middle school often blend subjects, such as the integration of art and mathematics when exploring patterns and symmetry, which helps students discover the interconnectivity of different fields of knowledge.

- Skill Building : Engaging in research equips middle schoolers with advanced skills in critical thinking, problem-solving, and time management, which are beneficial across their academic journey and beyond.

- Diversity in Content : Middle school research topics are notably diverse, ranging from examining the role of robotics in society to exploring the psychological effects of social media, catering to a wide array of student interests and strengths.

- Tech Savvy Learning : Technology-based research topics, such as the influence of smart cities or the impact of augmented reality in education, are deeply relevant to tech-savvy middle school students, making learning more engaging and relatable.

- Cultural Relevance : Researching topics like cultural traditions and their meanings encourages middle schoolers to develop a global perspective and fosters a deeper understanding and appreciation for the diversity within their own school community and the world at large.

You May Also Like

More From Author

+ There are no comments

Cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

You May Also Like:

- Our Mission

Teaching Students to Use Evidence-Based Studying Strategies

Applying studying methods that strengthen the brain’s ability to retrieve information can help students learn more effectively.

Every student can learn. But can they do it better? Research suggests that the answer is yes , and that having a great tool kit of strategies for learning and being able to use the right strategy at the right time have a significant impact on student outcomes.

The concept of neuroplasticity is layered on this—our brains are constantly changing as a result of the experiences we have, both positively and negatively. The time of greatest neuroplasticity is, unsurprisingly, the years that students are in school.

How do we help our students maximize their learning? Let’s start by looking at some of the best evidence-based strategies for helping students learn .

Use Retrieval Practice

It’s important for retrieval practice to be at the heart of how students study. Here are some examples:

- Have students take out a sheet of paper and write down everything they know about a topic. Then have them check their notes and revise what they wrote.

- Provide a test study guide for students. For each point, have them write what they know, check, then revise. When they can recall all of the details for a point, they’ll put a check next to it on the guide. They should keep going until they can check everything off.

- Give your students answer keys to problems, and coach students in how to answer them. They can use the key to check their answers and try to solve the problems they have. It’s best to use class time early in the year to build students’ capacity to do the work with increasing independence as time goes on.

Because retrieval practice feels more challenging than rereading notes and highlighting, students often find it frustrating. Coach students that it feels harder because their brains are working harder and making more connections. Because of this, the information and skills they’re learning are going to stick in their memory longer. Be sure to build in breaks for your students. A good rhythm might be 30 minutes of distraction-free studying, then 5–10 minutes of a proper break, then repeat this cycle. If 30 minutes of full focus is too long, try 20.

Use Spaced Practice

The close sibling of retrieval practice is spaced practice , which allows students to get a bit rusty before asking them to retrieve the material from their brain. This also feels hard for students. Make sure to tell students why you’re doing it. If you feel you have to grade it, grade based on effort rather than accuracy. Being incorrect and then fixing what they don’t know are key steps for students in spaced practice.

Students of all ages and abilities struggle to organize spaced practice. It helps if you build it into classwork and homework in the two weeks prior to a test. Use copious amounts of formative assessment to figure out what students currently know well and what they’re starting to get rusty on (and would benefit from spaced practice). Remember that any kind of assessment or activity can be used formatively.

Over time, build students’ capacity to do retrieval and spaced practice with increasing independence, and fade those initial scaffoldings away. Some students will need some scaffolds reapplied at some points, and this is OK. The first rule of scaffolds is: All scaffolds are temporary.

Explain the Purpose of Taking Notes and How to Do It

Students don’t have to record every word you say, but rather re-create key ideas and examples to help them study later. The goal of note-taking is to help students begin learning information right away. The focus is about getting them to summarize and paraphrase, and to capture key definitions, phrases, etc.

Put some class time aside early in the year, and explicitly teach students how to use their class notes to help them study. Here’s an example:

- Before taking notes, ask students to draw a vertical line three-quarters of the way down the page, and write notes on the left side.

- After they take notes, they can review them. For each section, they should come up with one or two questions for which that section of notes is the answer. Have students write these questions on the right side of the line.

- Next, have students fold the page in half along the line.

- Then, have them read the question and try hard to answer it.

- After they’ve answered the question, they can flip the page over and check their answer.

- Repeat this process for all the questions.

All students can benefit from explicit instruction in how to take notes in the context of that particular class—it’s important not to make assumptions that they can do this already.

Students can get context from a text through a quick scan of the introduction and subheadings; they can go chunk by chunk rather than read the whole document. Ask them to read a section, then close the book, and try to write down what they remember. Then they can open the book, reread the section, and amend what they wrote. Advise them to collect and prioritize any questions that arise.

Keywords and Flash Cards Are Effective Tools

There are other ways for students to retrieve information that stem from effective note-taking: The keyword method helps students memorize words and definitions. They find a sound or word hidden in the word they’re trying to learn and make up a tiny story that links it to the definition.

Flash cards can be a good way to help do this, but they’re rarely used well, so explicitly teach students how to use them correctly. At the start of the year, save some class time to help students create and practice using flash cards.

The must-do moment is pausing to think hard after they read the front of the card before flipping it over. If they know the concept, they should try to connect the idea to one or two others. If they don’t know the concept, advise them to take their time before flipping it over. Even if they can’t recall, this process helps the answer stick better when they read it.

If they really know a card, they can put it aside for a while but put it back in the deck to review later that day or tomorrow. Counsel students not to get carried away with arts and crafts studying. Making beautiful flash cards can be an immensely rewarding experience but can also leave students with insufficient time for studying.

Explain that memorizing keywords and definitions can help students learn. Their active working memory, where all their thinking takes place, can hold very few items (three to five) for a very short time (10 to 20 seconds). Having key words and definitions stored in their long-term memory frees up space in their brain to process the new things they’re trying to learn.

These effective and efficient strategies ask more of students’ brains and help them to learn the material right away so that they’ll have less to study when the test comes around. It’s important for students to know them—while these aren’t all of the game-changing evidence-based strategies out there, they’ll help get your students off to a good start.

Remember, these strategies are only good if students can get them to work within the context of your class. Help them to do this by building the strategies into class time, and actively encourage each student’s capacity to do this with increasing independence over time. Only they can do the work.

What do you think? Leave a respectful comment.

Kelly Field, The Hechinger Report Kelly Field, The Hechinger Report

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/education/what-science-tells-us-about-improving-middle-school

What science tells us about improving middle school

CHARLOTTESVILLE, Va. — In a middle school hallway in Charlottesville, Virginia, a pair of sixth grade girls sat shoulder to shoulder on a lime green settee, creating comic strips that chronicled a year of pandemic schooling.

Using a computer program called Pixton, they built cartoon panels, one of a girl waving goodbye to her teacher, clueless that it would be months before they were back in the classroom, another of two friends standing 6 feet apart from one another, looking sad.

“We have to social distance,” one of the girls, Ashlee, said. Then, as if remembering, she scooted a few inches away from her friend, Anna.

In classrooms off the hallway, clusters of kids from grades six to eight worked on wood carvings, scrapbooks, paintings and podcasts, while their teachers stood by to answer questions or offer suggestions. For two hours, the students roamed freely among rooms named for their purpose — the maker space, the study, the hub — pausing for a 15-minute “brain break” at the midway point of the session.

Welcome to Community Lab School, a tiny public charter that is trying to transform the way middle schoolers are taught in the Albemarle School District — and eventually the nation.

Here, learning is project-based, multi-grade and interdisciplinary. There are no stand-alone subjects, other than math; even in that subject, students are grouped not by grade, but by their areas of strength and weakness. In the mornings, students work independently on their projects; in the afternoons, they practice math skills and take electives.

“Our day revolves around giving students choice,” said Stephanie Passman, the head teacher. “We want kids to feel a sense of agency and that this is a place where their ideas will be heard.”

Anna (left) and Ashlee (right), sixth graders at Community Lab School, create comics depicting their Covid year. Photo by Kelly Field for the Hechinger Report

As a laboratory for the Albemarle district, Community Lab School is charged with testing new approaches to middle school that could be scaled to the district’s five comprehensive middle schools. The school has been held up as a national model by researchers at MIT and the University of Virginia, which is studying how to better align middle school with the developmental needs of adolescents.

Over the last 20 years, scientists have learned a lot about how the adolescent brain works and what motivates middle schoolers. Yet a lot of their findings aren’t making it into classroom practice. That’s partly because teacher prep programs haven’t kept pace with the research, and partly because overburdened teachers don’t have the time to study and implement it.

Today, some 70 years after reformers launched a movement to make the middle grades more responsive to the needs of early adolescents, too many middle schools continue to operate like mini high schools, on a “cells and bells” model, said Chad Ratliff, the principal of Community Lab School.

“Traditional middle schools are very authoritarian, controlling environments,” Ratliff said. “A bell rings, and you have three minutes to shuffle to the next thing.”

For many early adolescents — and not a few of their teachers — middle school isn’t about choice and agency, “it’s about surviving,” said Melissa Wantz, a former educator from California, with more than 20 years’ experience.

Now, as schools nationwide emerge from a pandemic that upended educational norms, and caused rates of depression and anxiety to increase among teenagers , reformers hope educators will use this moment to remake middle school, turning it into a place where early adolescents not only survive, but thrive.

“This is an opportunity to think about what we want middle school to look like, rather than just going back to the status quo,” said Nancy L. Deutsche, the director of Youth-Nex: The UVA Center to Promote Effective Youth Development.

The adolescent brain

Scientists have long known that the human brain develops more rapidly between birth and the age of 3 than at any other time in life. But recent advances in brain imaging have revealed that a second spurt occurs during early adolescence, a phase generally defined as spanning ages 11 to 14 .

Though the brain’s physical structures are fully developed by age 6, the connections among them take longer to form. Early adolescence is when much of this wiring takes place. The middle school years are also what scientists call a “sensitive period” for social and emotional learning, when the brain is primed to learn from social cues.

While the plasticity of the teenage brain makes it vulnerable to addiction, it also makes it resilient, capable of overcoming childhood trauma and adversity, according to a report recently published by the National Academies of Science. This makes early adolescence “a window of opportunity,” a chance to set students on a solid path for the remainder of their education, said Ronald Dahl, director of the Institute of Human Development at the University of California, Berkeley.

Meanwhile, new findings in developmental psychology are shedding a fresh light on what motivates middle schoolers.

READ MORE: Four new studies bolster the case for project-based learning

Adolescents, everyone knows, crave connections to their peers and independence from their parents. But they also care deeply about what adults think. They want to be taken seriously and feel their opinions count. And though they’re often seen as selfish, middle schoolers are driven to contribute to the common good, psychologists say.

“They’re paying attention to the social world and one way to learn about the social world is to do things for others,” said Andrew Fuligni, a professor-in-residence in UCLA’s psychology department. “It’s one way you figure out your role in it.”

So, what does this evolving understanding of early adolescence say about how middle schools should be designed?

First, it suggests that schools should “capitalize on kids’ interest in their peers” through peer-assisted and cooperative learning , said Elise Capella, an associate professor of applied psychology and vice dean of research at New York University. “Activating positive peer influence is really important,” she said.

Experts say students should also be given “voice and choice” — allowed to pick projects and partners, when appropriate.

In the ‘70s and ‘80s, reformers coalesced around a “middle school concept” that included such practices as interdisciplinary team teaching and cooperative learning. Kids often learn better when they work together, researchers said. Photo by Nichole Dobo/The Hechinger Report

“Kids have deeper cognitive conversations when they’re with their friends than when they’re not,” said Lydia Denworth, a science writer who wrote a book on friendship, in a recent radio interview .

Schools should also take advantage of the “sensitive period” for social and emotional learning, setting aside time to teach students the skills and mindsets that will help them succeed in high school and beyond, researchers say .

Yet many schools are doing the opposite of what the research recommends. Though many teachers make use of group learning, they often avoid grouping friends together, fearing they’ll goof off, Denworth said. And middle schools often spend less time on social and emotional learning than elementary schools , sometimes seeing it as a distraction from academics .

Meanwhile, many middle schools have abolished recess, according to Phyllis Fagell, author of the book “ Middle School Matters ”, leaving students with little unstructured time to work on social skills.

“When you think about the science of adolescence, the traditional model of middle school runs exactly counter to what students at that age really need,” said Ratliff.

A developmental “mismatch”

The notion that middle schools are misaligned with the needs and drives of early adolescents is hardly a new one. Efforts to reimagine education for grades six to eight dates back to the 1960s, when an education professor, William Alexander , called for replacing junior highs with middle schools that would cater to the age group.

Alexander’s “Middle School Movement” gained steam in the 1980s, when Jacquelynne Eccles, a research scientist, posited that declines in academic achievement and engagement in middle school were the result of a mismatch between adolescents and their schools — a poor “ stage-environment fit. ”

Propelled by Eccles’ theory, reformers coalesced around a “middle school concept” that included interdisciplinary team teaching, cooperative learning, block scheduling and advisory programs.

But while a number of schools adopted at least some of the proposed reforms, many did so only superficially. By the late ‘90s, policymakers’ attention had shifted to early childhood education and the transition to college, leaving middle school as “the proverbial middle child — the neglected, forgotten middle child,” said Fagell.

For many students, the transition from elementary to middle school is a jarring one, Fagell said. Sixth graders go from having one teacher and a single set of classmates to seven or eight teachers and a shifting set of peers.

“At the very point where they most need a sense of belonging, that is exactly when we take them out of school, put them on a bus, and send them to a massive feeder school,” said Fagell.

And at a time when their circadian rhythms are shifting to later sleep and wake times, sixth graders often have to start school earlier than they did in elementary school.

No wonder test scores and engagement slump.

READ MORE: Later school start time gave small boost to grades but big boost to sleep, new study finds

In an effort to recapture some of the “community” feel of an elementary school, many schools have created “advisory” programs, in which students start their day with a homeroom teacher and small group of peers.

Some schools are trying a “teams” approach, dividing grades into smaller groups that work with their own group of instructors. And some are doing away with departmentalization altogether.

At White Oak Middle School, in Silver Spring, Maryland, roughly a third of sixth graders spend half their day with one teacher, who covers four subjects. Peter Crable, the school’s assistant principal until recently, said the approach deepens relationships among students and between students and teachers.

“It can be a lot to ask kids to navigate different dynamics from one class to the next,” said Crable, who is currently a principal intern in another school. When their classmates are held constant, “students have each other’s backs more,” he said.

A study of the program now being used at White Oak, dubbed “Project Success,” found that it had a positive effect on literacy and eliminated the achievement gap between poorer students and their better-off peers.

But scaling the program up has proven difficult, in part because it goes against so many established norms. Most middle school teachers were trained as content-area specialists and see themselves in that role. It can take a dramatic mind shift — and hours of planning — for teachers to adjust to teaching multiple subjects.

Robert Dodd, who came up with Project Success when he was principal of Argyle Middle School, also in Silver Spring, said he’d hoped to expand it district-wide. So far, though, only White Oak has embraced it. (Dodd is now principal of the district’s Walt Whitman High School.)

“Large school systems have a way of snuffing out innovation,” he said.

Even Argyle Middle, where the program started, has pressed pause on Project Success.

“Teachers felt like it was elementary school,” said James Allrich, the school’s current principal. “I found myself forcing them to do it, and it doesn’t work if it’s forced.”

Restoring recess, and other pandemic-era innovations

But Argyle is continuing to experiment, in other ways. This fall, when students were studying online, the district instituted an hour-and-a-half “wellness break” in the middle of the day. Allrich kept it when 300 of the students returned in the spring, rotating them between lunch, recess and “choice time” every 30 minutes.

During one sixth grade recess at the end of the school year, clusters of students played basketball and soccer, while one girl sat quietly under a tree, gazing at a cicada that had landed on her hand. Only three students were scrolling on their phones.

Sixth graders at Argyle Middle, in Silver Spring, Maryland, play basketball during recess. Photo by Kelly Field for the Hechinger Report

“I thought when we got back, students would be all over their cellphones,” said Allrich, over the loud hum of cicadas. “But we see little of that. Kids really want to engage each other in person.”

Peter Gray, a research professor at Boston College who has found a relationship between the decline of free play and the rise of mental illness in children and teens, wishes more middle schools would bring back recess.

“You don’t suddenly outgrow the need for play when you’re 11 years old,” he said.

Allrich said he plans to continue recess in the fall, when all 1,000 students are back in person, but acknowledges the scheduling will be tricky.

READ MORE: How four middle schoolers are navigating the pandemic

Denise Pope, the co-founder of Challenge Success, a school reform nonprofit, hopes schools will stick with some of the other changes they made to their schedules during the pandemic, including later start times. “Don’t go back to the old normal,” Pope implored educators during a recent conference . “The old normal wasn’t healthy.”

Prior to the pandemic, barely a fifth of middle schools followed the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendation to start no earlier than 8:30 a.m. (Community Lab School started at 10 during the shutdown, but plans to return to a 9:30 a.m. start.)

But if the pandemic ushered in some potentially positive changes to middle schools, it also disrupted some of the key developmental milestones of early adolescence, such as autonomy-building and exploring the world. Stuck at home with their parents and cut off from their peers, teens suffered increased rates of anxiety and depression.

When students return to middle schools en masse this fall, they may need help processing the stress and trauma of the prior year and a half, said author Fagell, who is a counselor in a private school in Washington, D.C.

Fagell suggests schools survey students to find out what they need, or try the “iceberg exercise,” in which they are asked what others don’t see about them, what they keep submerged.

“We’re going to have to dive beneath the surface,” she said.

Deutsche, of Youth-Nex in Virginia, said teachers will play a key role in “helping students trust the world again.”

“Relationships with teachers will be even more important,” she said.

Fortunately, there are more evidence-based social-emotional programs for middle schoolers than there used to be, according to Justina Schlund, senior director of Content and Field Learning for the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. A growing number of states are adopting Pre-K through12 social and emotional learning standards or guidelines and many districts and schools are implementing social and emotional learning throughout all grades, she said.

For many middle school students, a return to in-person schooling means a return to a routine that allows no time for play. But, according to researchers, free time is essential to students’ mental health in early adolescence. “You don’t suddenly outgrow the need for play when you’re 11 years old,” says Peter Gray, a research professor at Boston College. Photo by Amadou Diallo for The Hechinger Report

At Community Lab School, middle school students typically score above average on measures of emotional well-being and belonging, according to Shereen El Mallah, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Virginia who tracks the school’s outcomes. Though the Community Lab students experienced an increase in perceived stress during the pandemic, they generally fared better than their peers at demographically similar schools, she said.

Anna and Ashlee, the sixth graders on the settee, said the school’s close-knit community and project-based approach set it apart.

“We’re still learning as much as anyone else, they just make it fun, rather than making us read from textbooks all the time,” Ashlee said.

This story about early adolescents was produced by The Hechinger Report , a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter .

Kelly Field is a journalist based in Boston who has also reported for The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Support Provided By: Learn more

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

As millions of students return to the classroom, parents remain divided on mask mandates

Nation Aug 10

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Teaching ELA with Joy

Middle School ELA Resources

10 Ideas to Make Teaching RESEARCH Easier

By Joy Sexton 1 Comment

I enjoy diving into research units with my students because they get to learn new things, and I do, too! But teaching research skills is a gigantic task! And one thing’s for certain: I’ll have to break the research process into steps to keep my middle school students from feeling overwhelmed. I want them to have that “I’ve got this” attitude from the moment I introduce the project.

Of course, as teachers, we need to be prepared and have our research assignments clearly-designed. But a big key to making the process easier for me and my students, what makes the most impact I think, is modeling . If you can model what you want students to do (as opposed to just telling them), your expectations become clearer. Not everything can be modeled, but whenever the opportunity arises, it’s powerful!

Here are 10 ideas to make teaching research skills manageable and successful:

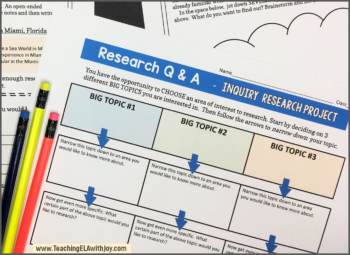

1. Make sure students start out with more than one topic option . What I mean is, it helps for each student to have “back up” topics ready to go in case the first choice isn’t panning out. For example, I’ve had students who chose a topic they were very passionate about. But it turned out that once they got searching, not enough information was turning up. In most cases, these students had decided to research very current topics like a YouTuber or a new version of iPhone or even a specific automobile. They searched and searched, but the few sites they located just repeated the same smattering of facts. It REALLY helped that the assignment required three topic choices, with students prioritizing their choices . Instead of getting all stressed out, the students just went with their second choice, and got right into note-taking. Or let’s say you are assigning topics, for example, for Holocaust research. Once they start researching, students may find a certain topic too complex and would feel more supported if they had other options.

2. Don’t rule out books and other print sources. Now that so many students carry laptops, we’ve come to expect research to be Internet-based. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with that! With just a few clicks, students have access to SO MUCH information. But some of my students come and ask if they can go to the library for printed sources because they prefer taking notes from books. That reminds me that we all learn differently. It might be to our amazement, but library research is alive and well for a portion of our students. Sometimes it’s my struggling learners who go for the printed sources, but I’ve also had more advanced learners hit the books as well. Even if you’ve got kids on their laptops or in the computer lab, find a way to incorporate different types of sources in their search so you differentiate . FYI, the Common Core Standards for W.8 (the research writing) state “Gather information from multiple print and digital sources . . .” So, it looks like using some print sources is still an expectation (but not for every assignment) if you follow Common Core. Definitely let your librarian in on whatever type of research assignment you have going on. They’re usually very eager to provide support !

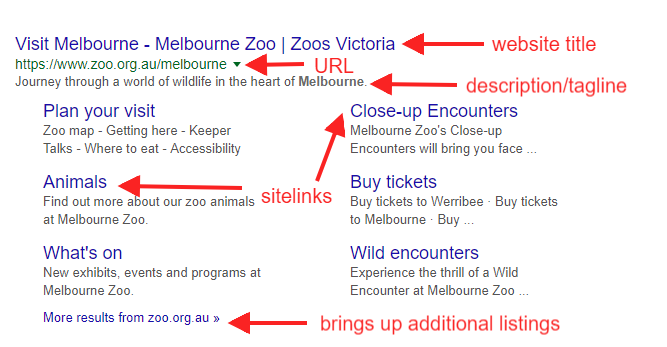

3. Emphasize the need to narrow search terms . So often, students just want to plop their main topic into the Google search bar, right? Unfortunately, what comes up is usually current information that is not necessarily going to hit what they need. That’s how time gets wasted. You can quickly model this skill for students with an example using a celebrity. Say you are needing information on a certain celebrity’s life—some facts about their rise to fame. Place just the name in the search bar, and what most likely comes up are articles that have been in the news about the person. Then place the name with the word “biography” in the search bar and have students notice the difference.

4. Explain the connection between research and reading . Once they have a topic, students are so ready to start note-taking! But wait, do your students understand that research starts with careful reading? First, they’ll need to preview several websites before taking any notes. I call it “Ten Minutes, Reading Only.” That’s the least they can do to look for sources that not only match their topic but meet their readability needs . Let’s face it, many websites or even printed sources are written well above some of our students’ reading levels. Let them know that if they are finding long sentences with numerous unfamiliar words, it’s time to move on. Then, once they do locate a few good sources, they still need to read! When they come upon information they understand that really hits the topic, BINGO. That’s when note-taking should begin.

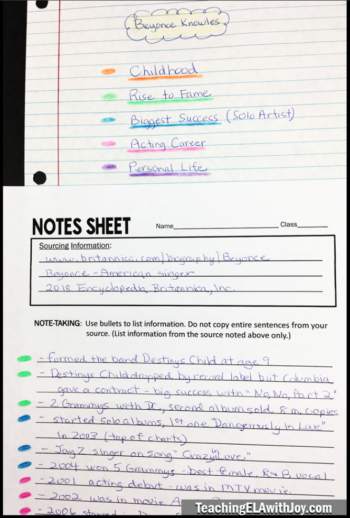

5. Model note-taking using a bulleted list of short phrases . One thing is for sure: we don’t want students to copy full sentences, word for word, when they take notes. So modeling this when you’re teaching research skills is huge. I always tell students that they will create their own complete sentences when they are drafting . Note-taking is for short phrases . Just give them a heads up that they have to be able to understand the shortened information! I’ve had students who wrote phrases too short for the complex information they represented. A problem arose, of course, when trying to draft sentences. The students couldn’t remember what was actually meant by the few words they had copied down.

You can easily model note-taking by choosing a paragraph of nonfiction from a website or online encyclopedia. Project it on your whiteboard or pass out copies to the class. You can have students work with a partner to take notes in short phrases on a bulleted list. Students could then exchange papers several times to see what others came up with, and then share out what they noticed. Or, you may prefer to make the notes on your whiteboard with whole-class participation.

6. Show students the citation generator you want them to use and how it works. Teaching research skills always includes citing sources. So if you approve of students having citations created for them, I’m with you! Just be clear on which citation generator to use. I’ve always preferred www.Bibme.org , but now with all the ads on these sites, and Google Docs’ own generator, there are other options. Again, you can do a quick modeling on your Smartboard using a website. It’s a good idea to walk around during note-taking and check that each student is comfortable using the citation generator. Sometimes students are unsure but might not want to ask.

7. Offer creative formats for students to use as their research product. If you can, let them infuse some of their own passion into the topic. Let’s face it, teaching research skills is easier when students are personally invested. Your standards or district curriculum may require a research-based essay , and that’s fine. With lots of scaffolds and modeling, the results can be awesome! But how about having students report out in a newsletter format? They can break the information down into four short articles and give each one a title. Now the assignment becomes more motivating. Or require a slide presentation, with a paragraph of text on each slide along with visuals.

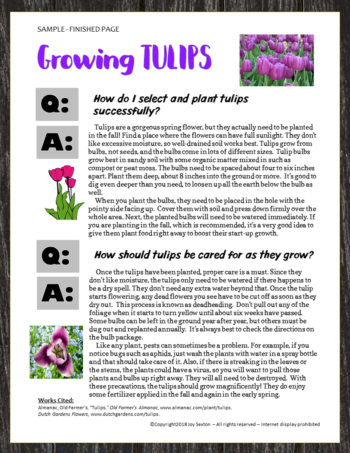

Another creative format is a Q & A page . My students enjoy a short project called Research Q & A , where they choose a topic they’d like to learn more about and create two questions to research. They report their findings on a Q & A sheet, using a template they type into, along with visuals.