- Join our email list

10 essential research tips for historical fiction writers

by Andrew Noakes

Includes…

Online archives with thousands of primary sources, image, video, and audio resources, maps, language tools, and specialist blogs.

1) Start with a plan

Even if you’re a pantser, you should plan out your historical research in advance. If you don’t, you’re likely to miss things. Start by figuring out what you need to know, then research a list of sources that will help you get there. I advise listing them by type and/or focus (e.g. primary, secondary, political background, daily life, etc.)

2) Take notes and record sources

No matter how big your brain, you’re not going to be able to remember everything you read, so take notes. They don’t have to go on for hundreds of pages, and they don’t even have to be that well organised at first (you can sort that out later), but I would recommend keeping note of where vital bits of information come from. Believe me, you’ll need to refer back to your sources.

3) Cross-reference

One of the first things you need to know about historical sources – whether primary or secondary – is they can be wrong. Errors can range from small and annoying (incorrect dates, misspelled names etc.) to major and highly problematic (like ascribing historical events to the actions of the wrong people).

The important thing is to try and cross-reference everything you read, especially the important things like critical dates and key figures. You should even try and cross-reference small details like diet and clothing when you can. Mistakes in these areas can really put readers off.

4) Check the provenance

Sometimes, errors in historical sources stem from the agendas of those who wrote them. In truth, there’s no such thing as an unbiased source. Every piece of historical writing will, to some extent, be influenced by the outlook of its author and the trends of its time.

The most misleading sources, though, are those that deliberately obscure the truth. Some seek to absolve their authors of blame for a particular historical event; others may seek to cast false blame to damage someone’s reputation. The point is this: the likely purpose of a source affects how we should read it. So always check provenance.

5) When sources disagree…

Sometimes, two sources will contradict each other even though they both seem credible. This can be down to a legitimate difference in interpretation, and in those cases you can feel safe in siding with the interpretation that you find most convincing. You can also adopt your own interpretation, providing it’s plausible and you can back it up.

Occasionally, though, the contradiction occurs because one source has got something wrong. If you’re unable to cross-reference further (i.e. if there aren’t more than two credible sources), then you’ll have to make a judgement call. Which source has more consistently got things right? Which source has the greater authority? Consider these carefully and make a decision, then note the contradiction and your approach to resolving it in your historical note if you’re using one.

6) When there are no sources at all…

This is more and more likely to happen to you the further back your story is set. But try and turn it on its head for a second: remember, you’re not a historian. It’s part of your craft to fill in the gaps with your imagination. In fact, some of the best historical fiction stories grow between the cracks found in history.

If something cannot be known, then so long as your interpretation feels plausible, it’s entirely legitimate to chart your own path. Just make sure you explain the gaps and how you filled them in your historical note.

7) Strike a balance between primary and secondary sources

Primary sources can give you an authentic flavour of your chosen era, and they can help you to reproduce authentic voices in your story as well, to say nothing of their value in providing a deeper insight into historical events.

But secondary sources are also vital for providing you with a wider perspective on those events. Historians can assess things with the benefit of hindsight and through a broader lens.

In truth, you need to use a good mix of both primary and secondary sources in order to properly research your period.

8) Don’t just look for the facts, find the essence of your era as well

Sometimes, I read a manuscript and I just don’t feel ‘in the period’. It might be the way the characters speak to each other, it might be their social and political attitudes, or it might be their etiquette. Whatever the case, the story will feel off.

That’s why it’s important not just to learn the core facts of your period, but to immerse yourself in it as well. Historical fiction authors who do this well recommend reading diaries, newspapers, and other primary sources, investigating cultural artefacts like art and music, and even eating meals from your era!

9) Knowing when to start writing

When do you know you’ve reached that magic point where you’ve done enough research and you can finally start writing?

The truth is you’ll probably never know for sure. After all, there’s no truly objective way to measure it. But it helps to make a list of questions you think you need the answers to before you begin writing. Once those have been answered satisfactorily, you’ll know the time for writing is near.

10) Research while you write

Just because you’ve started writing, it doesn’t mean your research is over. You can – and should – continue to research while you write to enrich your understanding of your period and keep your knowledge fresh. Sometimes, a little bit of extra research can also ignite the flame of inspiration if you’re struggling with writer’s block.

So, there you have it. Those are my 10 essential research tips for historical fiction writers. I hope you find them useful as you research your next story. If you’re looking for more guidance, don’t forget to download our 50+ top online research resources as well.

P.S. Solid research is just one aspect of writing historical fiction. To learn about the others, make sure you read our dedicated guide, How to write historical fiction in 10 steps . You might also be interested in Top tips on writing historical fiction from 64 successful historical novelists .

Do you write historical fiction?

Join our email list for regular writing tips, resources, and promotions.

Writing guides

How to write historical fiction in 10 steps

Top tips on writing historical fiction from 64 successful historical novelists

Beta reader service

Get feedback on your novel from real historical fiction readers.

ARC service

Use our ARC service to help generate reviews for your book.

Top resources

Guide to accuracy and authenticity in historical fiction

Novel outline template for historical fiction writers

60 historical fiction writing prompts

How to write a query letter

Featured blog posts

30 top historical fiction literary agents

How to write flashbacks

When (and how) to use documents in historical fiction

How to Research a Historical Novel: Escape the Research Rabbit Hole

by Guest Blogger | 0 comments

Want to Become a Published Author? In 100 Day Book, you’ll finish your book guaranteed. Learn more and sign up here.

It doesn't take any research to know that historical fiction writers love spending time in history books, digital archives, museum exhibits, and library collections—and that's just in our spare time!

But how do we keep that research from overshadowing the actual writing of our books? How do you research a historical novel without getting lost in the research rabbit hole?

This guest post is by Susanne Dunlap, author of twelve works of historical fiction for adults and teens. You can find her newest book The Portraitist here and find all her books and courses on her website susanne-dunlap.com.

Face it, none of us would write historical novels if we didn’t love the research. If we’re lucky enough to go to historical archives, the very smell of the dust, the idea that the materials and primary sources were handled by people decades or centuries ago, gives us a thrill.

And when we discover something others have overlooked, maybe that little fact that gives us something to hang an entire plot on—pour the champagne! History inspires us, it amazes us, it fascinates us—it torments us.

Research is wonderful and essential. But it can so easily commandeer all our time and energy.

How far do you need to go to track down a person or a date? What if you can’t go to places or get ahold of archival material? Do you have to know everything about the historical period and place and characters in your novel?

Won’t readers be waiting with red pens to circle any little thing you get wrong, or take exception to your interpretation of a historical character’s motives?

And what about the sheer volume of material we now have access to, thanks to the Internet and online archives? One thing leads to another and then another and then another. Before we know it, weeks have passed and we’ve got tons of research but haven’t put a word on a page.

How to Escape the Overwhelm of Research

I had to let go of that tendency to remain mired in research in a hurry when I was forced to research and write a complete manuscript in a year. It had been sold on a one-page proposal.

As I wrote, I remember being certain that someone would take me to task for changing the year a composition by Chopin was published, which I had to do in order to make my story work. But no one cared in the end.

That’s when I first learned that the story comes first, history comes second—a lesson I've had to learn over and over. Story first, history second.

That may sound like sacrilege coming from someone who started writing historical fiction after being in the academic world—a PhD in music history from Yale.

In academic articles, it really mattered that I’d consulted every known source, verified everything and didn’t categorically state something unless I knew it was backed up with historical sources and facts. I learned that the hard way, submitting articles for peer review. Ouch.

When I chose to start writing historical fiction, the research obsession was still deeply ingrained. For the sake of readers and my own sanity, though, I had to learn how to subjugate research to story.

I don’t mean being inaccurate or anachronistic (when a detail is in the wrong time period such as a television in 11th century Europe). I mean becoming comfortable with the necessary limits and with using my own imagination to fill in any gaps.

When My Research Turned Into a Rabbit Hole

My novel The Portraitist is a good example. I started working on it—on and off—seven years ago. Then, I was researching Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, the bitter rival of Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (protagonist of The Portraitist ), thinking she would be the focus of my story.

There was so much material about her, so many paintings, a Metropolitan Museum exhibition of her work, and her own three-volume autobiography—published when she was very old.

Not only that, but because she was the official portraitist to Marie Antoinette, I felt obliged to research everything about the doomed queen and the true events surrounding Louis XVI’s court.

Through that research, I discovered a close friend of Elisabeth’s, another artist: Rosalie Bocquet Filleul. What a story there!

She married the concierge of the Château de la Muette and became concierge herself after his death. She produced several pastel portraits of royals, and—perhaps more interesting—took a number of likenesses of her neighbor in Passy, Benjamin Franklin.

When I discovered that little fact I had to start researching Benjamin Franklin, his life and politics and how he ended up in that diplomatic residence next door to Rosalie Filleul—of whom he became very fond, not least of all because she was stunningly beautiful.

The rest of Rosalie’s story was poignant and tragic. She ended up guillotined because she auctioned off some chairs that belonged to the Château (I argue she was destitute and nearly starving).

So I wrote a manuscript that encompassed the stories of all three of these remarkable women. How could I leave anything out?

Turns out, I should have. That manuscript was a monster. Too long, too complicated, and I couldn’t do justice to any of the women. I had Too. Much. Information.

How to Set Research Limits

Now, of course we love stumbling on all that good stuff, those intriguing tidbits and interconnections. I’m not saying you shouldn’t do that—there’s no “should” about this.

My point is that at some juncture, you have to let go of the idea of “everything,” or the idea that you have to be the expert, and set your limits.

What limits? You might ask. There are several ways you can rein in your research so it really serves your story.

Once you’ve done enough research to figure out the primary story you want to tell, map it out. I mean that both literally and figuratively. I’m not an outliner by nature, but I’ve learned—again, the hard way—that it’s important to know a few basic things:

1. The time period of your story present.

This may seem obvious. Of course you know what time period you’re writing in!

What I’m suggesting here is that you take a good, hard look at how much of that stretch of time you really want to use.

While there may be a case for covering the entire real life of a historical figure, that sort of endeavor is best left to a biographer. You’re looking for the period bounded by the exact moment that triggers the action in your story, and the exact moment when your protagonist’s arc of change is complete.

Put another way, the moment at which the story question is answered.

You’ll no doubt have researched things around this historical time period, and that’s good background information. But you only really need to look in depth at the historical events that directly affect your protagonist.

2. The places where the story is set.

This is possibly a little easier. I’ll give you a simple example: The Portraitist takes place before, during, and after the French Revolution. But it’s set entirely in or near Paris.

To get even more precise, the primary locations are the Louvre, Versailles, the Château de Bellevue, and a suburb of Paris called Pontault en Brie.

No doubt a lot was going on in other parts of France, and of course, there’s that whole American Revolution that had an impact on the French, but it didn’t impinge on my protagonist’s life. Not Adélaïde’s, in any case. (I axed Benjamin Franklin when I focused the story away from Rosalie.)

Once you have that all mapped out, you can get the vital everyday life information about how your characters get from place to place, how long it takes, whether it was comfortable or a huge pain, how much it might have cost, etc.

I did say you still have to do a lot of research, didn’t I?

3. The main characters.

Another obvious one, but if you keep reminding yourself that the focus is on your protagonist and one or two others, you might avoid amassing research that would only bog down your story if you tried to include it.

And maybe you’ll stop yourself from digging into the life of an interesting but peripheral character (did I mention Benjamin Franklin?) when you should be working on getting those words on the page.

4. Finally, give your research the necessity test.

This is simple: Ask yourself as you start diving into that rabbit hole if what you’re looking for is absolutely necessary.

If you don’t have that piece of information you’re looking for, will something important be missing from your book? Think it over. If the answer is no, then you're likely creating the dreaded info dump.

Once you’ve set your limits, organization is your best friend.

How to Organize Your Research

I have one word for you (and I’m not being paid to say this): Scrivener .

Even if you don’t want to use it as a drafting tool, it has so many great features, not the least of which is that you can use it to gather and organize all your research, even import Web pages so you don’t have to go hunting for that bookmark you forgot what you called or where you put it.

If you’re tech savvy, you can also add metadata to make it easy to search.

And if you’re REALLY tech savvy, you can sync it with another great tool, Aeon Timeline . It would take a long time to explain all the benefits of this app for historical novelists, so I’ll leave it to you to go and check it out. The good news is that neither of these apps is very expensive.

Of course, spreadsheets work too, if that’s your comfort zone. But I recommend at least giving these tools a look.

What you’ll probably find when you start organizing all your research is that having to do so gives a good view of what’s essential and what’s not. You can keep it all, but putting it in folders by priority or time span is a sanity preserver.

Do the Research, but Write the Book

My tips above won’t let you off the hook for doing good, solid research. But they may help you give yourself permission to be more focused, to not have to know absolutely everything.

Sure, you’ll write along and discover a gap in your knowledge that you need to fill in order to tie something together or provide a motivation—or just move your characters around from place to place. So be it.

Do that research when the need arises, don’t try to anticipate every eventuality at the start. It’s all about giving yourself permission.

You want to get that draft written. I want you to get that draft written. So embrace the limits and get organized!

Where do you get stuck in the research process? What tips have helped you learn when to stop, so you can get back to your writing? Share in the comments .

Join 100 Day Book

Enrollment closes May 14 at midnight!

Guest Blogger

This article is by a guest blogger. Would you like to write for The Write Practice? Check out our guest post guidelines .

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

How to effectively research historical fiction

I write a lot of historical fiction. All but one of my book manuscripts is historical, whether that’s set in the 1850s, 1940s, or eep – 1990s. It’s easier to write about a period you’ve lived through, but what do you do when everyone who lived during that time is long gone?

You could just base your historical fiction off what you’ve seen in movies, but that would do a disservice to your writing. Funnily enough, movies are not always historically accurate… So I’ve put together my top tips for how to research historical fiction.

Research helps build the authenticity of your historical fiction, whether that’s a Regency romance or a Victorian crime novel. I’ve found that researching books uncovers facts that have ultimately influenced the outcome of my story.

And while there will be times that you need to research while you’re writing – your character gets into a fight and you want to know a historically accurate rapier or gun ASAP – it’s important to do as much research as you need before you write your book. At a minimum, you should be able to answer all the questions outlined below.

Define your fiction’s limits

Before you start your research, you must identify the location and year/s of your book’s setting. This will help narrow your research.

After defining the limits of your fiction, the basic questions you will need to answer researching any historical novel are:

- What did the locations in my story look like at the time?

- What sort of clothes would my characters wear?

- What foods and drinks were consumed?

- If it’s set in a city, what landmarks were built at the time? Big Ben was still being built in the 1850s, so it will seem funny if it’s in your 1830s novel.

- How would people of the period perceive my character? What class are they? How do they fit in with the rest of society?

- What kind of employment was available? Don’t make assumptions about this. I assumed that early newsrooms were filled with men, but women played an important and documented role in both typesetting and editorial.

- What kinds of rituals and etiquette were observed?

- Are there any social issues I should be aware of that have modern consequences for readers? Things such as slavery, racism, and sexism of the period will bring out contemporary responses for readers. How will you address present-day concerns through the lens of the past?

- Who were the rulers/governors at the time?

- What wars and conflicts was the country/state/city involved with or influenced by?

- If you’re writing a crime novel, what were the procedures for law and order? Was it organised or more informal?

- What kind of transportation was/wasn’t used at the time?

- What technology was/wasn’t available at the time? Be careful to check the dates on inventions, particularly regarding communications and medicine.

- Were there common languages or languages for the elite and poor?

- Is there patter from the period you can use in dialogue?

What if you don’t know when or where your book is set? You might have a general idea of the period you’d like to write in. In that case…

Start broad, dig narrow

The first place you want to start is in general histories. A simple search of your library or favourite search engine for books on the period will turn up a plethora of results. Look for the best reviewed books and start there.

Another way to find the best books on a particular period is to look in bibliographies. What books are referenced again and again by researchers?

Many popular books about the Victorian era rely on Henry Mayhew’s London Labor and the London Poor, one of the first books to document firsthand accounts of poverty in London. It is an absolute must-read for anyone writing in that historic period. Rather than reading ten books which quoted the Mayhew, I just read the Mayhew.

What types of research resources are helpful for historical novelists?

Non-fiction books.

The obvious first place to start is with non-fiction books. The kinds of books that are often useful for filling in historic detail are:

- First-hand experiences and accounts

- Books documenting how people lived in the era

- Niche books relevant to your topic

- Photography and illustration books

- Costume books

- Dictionaries – useful for language

While the library is my first stop when looking for unique books (some of which can be expensive to purchase), the following sites have useful resources:

- Project Gutenberg often has first-hand accounts in the public domain

- Wikimedia Commons is a great resource for imagery from historic periods

- Better World Books, eBay and AbeBooks often have hard to find and ex-library books for a reasonable price

Maps are an invaluable research tool for the novelist, as you can mark them up and trace your character’s route through the city. I use maps a lot in writing fiction, both large printed maps that I mark up, and google maps.

Yes, I’m going to say it. I use Wikipedia to get a general overview of an era…

…but that shouldn’t be the only source of information you reach for. While it’s helpful for outlining the basic facts and characters in a time period, there are far more websites out there dedicated to particular aspects of history. I won’t tell you how to do a google search, because it’s probably how you ended up here.

First-hand documents

First-hand research doesn’t have to be difficult! Museums can provide vast sources of inspiration and ideas for your novel. While you can’t touch the exhibits, you can document your research while you look through a museum. And if you can’t get to a specific museum, many of them have online databases and images of their collections that you can access for free.

A great example of this was when I needed to find images of Wapping and the London Docks in the 1850s. I searched the National Maritime Museum’s archives and discovered sketches that Turner had done of the docks. While it would be too expensive for me to travel to London to see the locations (as much as I want to), I could get a sense of what it was like.

Unless you have a particular interest in a topic or are basing your novel on a real-life figure, it’s unlikely that you’ll need to handle first-hand documents from the period. But if you need to, you can access these texts from many state and national libraries. While there might be strict location and handling requirements on items, many librarians would be keen to help a novelist research their book.

Ask an expert

On that note, if you are writing about a very niche topic, don’t be afraid to ask an expert if you can’t find the information you need. I needed to know something specific about how the postal system worked in the Victorian era, so I emailed the postal museum who were more than happy to help. Experts are often excited to meet someone who is interested in their work.

Visit your location

If you can visit the locations in your book, do! Make sure you take a notebook and jot down your impressions of the location. Think about how your characters would perceive and walk around the space. Take your time to absorb the atmosphere and take photos if permitted.

When I was writing a book based on the legend of Count Dracula, I was lucky enough to visit Transylvania. Not even Bram Stoker got to Romania (he based most of his ideas of Transylvania on a travel book). It’s a place I’ll never forget, and my writing was made richer for having gone there. Place is a powerful inspiration for story.

YouTube Videos

While YouTube is a relatively recent phenomenon, it has a vast amount of historical resources. Need to find out how an old gun works? Someone has made a video on that. Want to see a historical costume in action? Someone has made a video on that. I kid you not – I’ve used YouTube to see how both old cameras and guns worked for my novels.

Document your research

Now you might have all this amazing research, but don’t store it in your head!

Documenting is just as important as researching your book. Make sure you have a good note-taking system. Whether that’s a single paper notebook for all your research or using an online tool like OneNote or Evernote to keep it in one place.

Taking photos are also very helpful for documenting places – just check you’re allowed to in private locations and museums before bringing the camera out.

Integrating your historical research into your fiction

While this topic could be a whole separate blog post on how to include historical details in your fiction, it’s important to integrate your research naturally in your work. While we might get obsessed with say, a certain shoe, if it’s not relevant to the story, you shouldn’t be giving a paragraph of backstory on a shoe.

Likewise, don’t be too obvious about integrating your research into dialogue. We don’t need tour guide characters who say, “And this is Big Ben, which was completed in 1859, and is actually the name of the bell inside the tower, not the tower itself. Now follow my umbrella…” A better way is to have characters comment from their perspective – “Gov, those builders better get on with finishing that tower.”

Follow that damn rabbit

Some people will say not to go down the rabbit hole, but I say follow that rabbit. If you’ve stumbled across an interesting aspect of history that no one has ever written about, and you’re curious, keep going. Chances are that curiosity might spark something new.

I hoped this post has helped you learn more about how to research historical fiction. As always, if you have questions, hit me up in the comments below, and let me know how your research is going!

3 responses to “How to effectively research historical fiction”

Thanks for the helpful article!

Thanks for taking the time to check out my blog 🙂

[…] How to effectively research historical fiction […]

Share your thoughts Cancel reply

ENGL 3025: Writing Historical Fiction: Doing Research for Your Writing

About this guide, pre-research the period and location, create a convincing picture, databases for finding details of the period, databases for researching specific periods, primary texts by period, historical newspaper databases, study secondary sources, sources used - find more tips there, get help with your research, document your sources, who wrote this guide.

This guide is primarily developed in support of the course ENGL 3025: Writing Historical Fiction. It outlines elements of research and provides links to resources and research tips.

While many suggested resources are available online, please note that research for historical fiction may require using print resources, visiting libraries and archives, and conducting personal interviews and research consultations.

- Identify the location and year(s) of your piece setting.

- Look at a variety of resources to immerse yourself in a period/event.

Search Summon

Search tip : Do a keyword search; for example, Berlin Wall

Limit to publications from a certain period

Look at different material types

Search the Library Catalog

Search tips

- September 11 terrorist Attacks, 2001

- March on Washington

- Subject headings may not be intuitive. Start with a keyword search, e.g., "9/11,” and then look at subject headings attached to relevant records. Then browse subject headings

Find personal accounts

Where to find them

Library catalog and suggested databases (scroll down for lists of databases).

- Correspondence

- Reminiscences

- For more results click the OhioLINK button on the results screen

Study details of the period

Look for clothes, jewelry, transportation, architecture, etc.in paintings, photographs, documentaries, etc.

- Library catalog

Search tip: To find images in the library catalog use the following keywords:

- Pictorial works

- Documentary photography

- Digital collections of museums

- For pieces set in Cincinnati: Digital Library of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamiltion County

Look at books/periodicals/media

created at the time of your story.

Where to find books

- Google Books

- Project Gutenberg

Tip : In Project Gutenberg explore bookshelves, e.g., US Civil War )

Where to find newspapers

Study historical maps

See " Digital Maps " in the Geography & Environmental Science Resource Guide. May of the maps listed there are historical.

Old Maps Online (multiple countries)

Some databases for researching specific periods include maps (click on the Information button for descriptions)

Research language

"...certain aspects of language can detract from the seeming authenticity of the characters’ words, and these include both archaic or “difficult” language, and anachronistic language or ideas, both of which, in their different ways, can throw the reader out of the illusion the novelist is trying to convey. " " Ancient or modern? Language in historical fiction " by Carolyn Hughes/

Helpful resources

See also “Find personal accounts” and “Look at books/media created at the time of your story.”

Verify information

Check dates, facts, etc.

Wikipedia is great for this! Libraries have even more resources.

- Online Reference Shelf

The Library provides networked access to many more full-text, primary source databases than can be listed here. Others may be located through the Library Catalog and Databases , which contains an alphabetical list of online resources related to Language and Literature.

All Periods/Long Full-Text Coverage

Middle english, early modern.

19th Century

Modern and contemporary.

- Newspapers/Research Databases (Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County

Secondary sources include non-fiction accounts, biographies, academic papers, interviews with historians and experts.

Follow academic discourse related to your historical period or event for different angles, recent findings, and bibliographies.

Secondary sources will also help you identify social issues of the period.

Suggested databases

" Helpful Research Sources for Historical Fiction Writers ." Write to Done.

"How to Do Historical Research for a Novel by Claudia Merrill.

"How to effectively research historical fiction" by Kat Clay.

" Historical Fiction: 7 Elements of Research" by M.K. Todd. Now Novel blog.

- All Online Research Guides

- Ask a Librarian (Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton Coutny)

- Last Updated: Mar 11, 2024 11:55 AM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.uc.edu/histfiction

University of Cincinnati Libraries

PO Box 210033 Cincinnati, Ohio 45221-0033

Phone: 513-556-1424

Contact Us | Staff Directory

University of Cincinnati

Alerts | Clery and HEOA Notice | Notice of Non-Discrimination | eAccessibility Concern | Privacy Statement | Copyright Information

© 2021 University of Cincinnati

7 tips on researching and writing historical fiction

Clare harlow: 'look out for other writers who aren’t afraid to gently tell you how to make your work stronger', samuel burr: 'writing is a craft and not a gift as far as i’m concerned' , by leila aboulela, 28th feb 2023.

Leila Aboulela was born in Cairo, grew up in Khartoum, and moved to Aberdeen in her mid-twenties. Nominated three times for the Orange Prize (now the Women’s Prize for Fiction,) she is the author of five novels, including Bird Summons , The Translator , and Lyrics Alley , which was Fiction Winner of the Scottish Book Awards. Leila was the first winner of the Caine Prize for African Writing, and her short story collection, Elsewhere Home , won the Saltire Fiction Book of the Year Award. Leila’s latest novel River Spirit will be published by Saqi Books on 7 March 2023.

Leila has been a guest speaker in special masterclasses for our Writing Your Novel students and a mentor for our Breakthrough Writers’ Programme – our initiative for under-represented writers. Here she shares some insights on how to approach historical research for a novel, drawing on her own experience of writing River Spirit, which is set in 1880s Sudan.

I’ve always loved reading historical fiction. There is something magical about stepping into the past, a tantalizing place where we can experience ways of life that have vanished. It was, though, only after writing contemporary novels, that I gathered up the courage to write historical ones. To be honest, the research put me off. The word ‘research’ conjured up hours spent in solemn libraries, studying historical tomes, wading through tedious facts and dates of battles. But it need not be like that. I found that research itself could be part of the creative process, that it could be inspiring and lots of fun. Here are the tips, based on how I did it.

1. Follow your fascinations

Read the history that interests you, rather than what you feel you should read. For River Spirit I went to the Sudan archives in Durham University. There, I came across a bill of sale for a slave girl. Her name, Zamzam, gave me an image of her. It was as if I knew her. This triggered my interest in nineteenth century slavery in Sudan. I began to research that topic. I had never intended the main character of my novel to be an enslaved woman. But how Zamzam became enslaved and how she found freedom, fascinated me and so I based my research on finding out more about the kind of day-to-day life she would have likely experienced.

2. Speak to the experts

I interviewed researchers who had written about nineteenth century Sudan. They pointed me towards specific books and papers – and saved hours of my time.

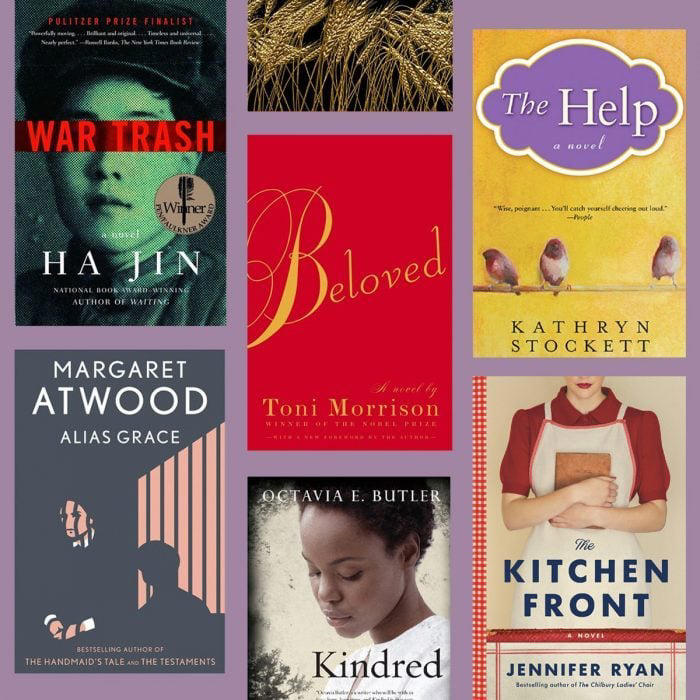

3. Read novels set in the same place and historical period

This was lots of fun because I could enjoy the fiction while at the same time feel that I was working! I picked up interesting, relevant details as well as the names of useful sources listed in the Acknowledgement pages.

4. Find your fictional characters in the footnotes of history

Many historical novels are based on minor figures in history, real people who are mentioned briefly in the footnotes. They might have played a minor part, or they were present when important things happened. Because little is known about them, they provide an opportunity for the creative writer to fill in the missing pieces.

5. Switch between researching and writing

Although I started off with the research, I didn’t devote all my time to it. If I felt creative, I would work on my novel. Sometimes I would keep writing until I got stuck and needed to research something specific. I remember my mum visiting me for a few weeks and to avoid walking around in a hazy daydream in her presence (which is what I’m normally like when I’m writing), I focussed solely on the research. But most of the time, I wrote and researched at the same time. One feeding the other.

6. Expect a longer editing process

Although I was careful, I ended up making the obvious mistake that historical novelists are inclined to fall into. My first draft had too much research! Information dumps, repetitions, ‘look what I know’ paragraphs. I had to cut and cut and cut again. I had to decide what was important to the story and what was not. The copy-editing stage took longer than with my contemporary novels. Lots of fact checking and another chance to trim down on non-essentials.

7. Accept that the research might never end

There are so many history books I could have read but I didn’t. Ones I started but abandoned because I got carried away with writing! The novel was going well and there was nothing more I needed to research. But it would be dishonest to say that I ever felt that I was finished with the research. Perhaps one can never finish researching a historical period. It is more about deciding when to stop and focus on the writing. The research can go on forever. At the end, it is the central story, and the characters who make up the novel, while the historical research remains in the background.

Get your hands on a copy of River Spirit , out 7 March.

If you’re working on a historical novel, why not join our specialist six-week online course: Writing Historical Fiction .

Transform your writing life.

How to Research Historical Fiction

Writers often have a bunch of tabs open on their internet browsers. Sometimes we go incognito, because we look up some weird, weird stuff.

Crime and mystery writers might look up police procedures, stages of putrefaction, how to kill someone, types of poison…but not just that. Car models, flowering shrubs in a particular part of the world, average rainfall on a particular day. Train sounds, what color the Ligurian Sea is…you get the picture.

“You” being the reader. Details are important in fiction, because details help readers quite literally get the picture in their heads that makes the ‘fictive dream’ come alive.

Some genres, like hard science fiction or military thrillers, require some deep research or personal experience (or a degree!), along with a vivid imagination.

Historical fiction is similar in that you must either have time travelled, OR you must have a knack for researching.

Luckily, this knack is not such a secret thing. It can’t be learned.

A short story about a long process

I’m writing historical fiction again. It’s the second in a trilogy. Here’s the story of the first one, if you are interested in the sheer doggedness required to write a novel when your skills are insufficient. On that first novel I got through the initial draft, then realized it was thin because…details. Needed them, didn’t have them. Knew sort of how to get them, thanks to an undergrad degree in History.

For the next two years I read a lot of nonfiction about the time period. I also read some fiction set in that period, but not too much–I didn’t want to use the same details everyone else used. Also because I had deliberately set the story in a place and time where there weren’t many “comparative titles.” (Here’s an explanation of what comparative titles means, if you’re new to the term.)

Tip #1: Let your research serve the scene & not vice-versa.

All the time spent reading and researching led to one thing: a few close-ups of particular moments in time. Yes, I set an entire scene in a swimming pool on the Seine because I thought it was a cool venue–but the scene had to happen somewhere. The setting worked for the action and for the characters’ emotional arcs, so it was fair game.

Tip #2: Keep characters’ point of view in mind.

This first novel in what I believe will be a trilogy was from a male POV. Just one POV. He was a newspaper illustrator, so I had to remember that photos weren’t yet used much in the press ( The Illustrated London News used sketches, as did most other outlets at the time). I had to remember, for the 7 or 8 scenes where my character was sketching, that the form had certain specific limitations because they’d be made into engravings that the newspaper could print in multiple thousands of copies. They needed to have simple cross-hatching, enough white space for the image to stand out.

And on a more general level, I had to remember that my POV character would see everything from under a hat brim, at least in outdoor scenes. So I also gave him “hat head” in every scene set indoors (where he removed his hat at certain times) because it made me laugh, and because I think it made him more sympathetic.

Tip #3: Academic texts, newspapers from the time, weird websites, and primary sources are your friend

That particular historical novel has some characters that came from my own field of historical study as an undergrad, which was the Meiji period in Japan. During this time, the Japanese sent out “missions” to study the exemplars of everything developed during the 200 years Japan’s borders had been closed.

A mission might consist of a few dozen men. They went all over the world. They would tour shipbuilding facilities on the River Clyde in Scotland, study hospital design and breakthroughs in medicine in Holland and Scotland, scientific research and democratic structure in Germany, Western art in Italy, and so on. Wherever these missions went, they took a deep interest in all those working on the cutting edge of their field.

Because there wasn’t a lot of information out there on the internet on what it was like to be part of a Meiji mission, I got a library card for the local university. I pored over the academic texts and theses that studied that period from a number of perspectives and topics.

The internet is great, but it can also be full of misinformation. Websites, much as I love the people who blog on subjects dear to my heart, are simply a starting point to gather information and ideas for various plot turns.

Academic books and trade nonfiction from university presses, on the other hand, have been stringently researched, are heavily footnoted, have the most incredible list of jumping-off points in their bibliographies, and best of all, they dive deep into a particular subject in a way that most blog posts can’t. There is nothing like an entire nonfiction book on a subject to bring up your level of understanding. Five different books from five different angles is even better.

Newspapers are a goldmine for the comings and goings of famous people and for the advertisements for products and services.

Guide books from the historical time period (assuming it’s post-printing press) are invaluable for information on fares and schedules.

You can gain access to much of this stuff through the Internet, by the way! Internet Archive (a digital library), Victorian Voices (a fantastic compendium of journalism and other treats from the period), Project Gutenberg (lots of old books, including guidebooks) .

Libraries are another goldmine. Your local library card might get you free access to JSTOR and other databases for academic articles and primary resources . Here’s a website from Fordham University with some good links . Academic articles are a goldmine for historical novelists. Peer-reviewed journals publish articles that, although they have a slant, are as close to factually correct as we “modern” humans can be about our past.

Finally, if you’re really into the facts, you can get some records from governments and institutions. When I was researching cinematographer Gregg Toland for a novel about F. Scott & Zelda Fitzgerald, I sent away to the state of California for a copy of Toland’s marriage certificate. They asked no questions! And sent me the info.

Don’t you love history?

How to Research Historical Fiction and Nail Your Setting

You know you have to actually research historical fiction.

You know you can't write your frontier romance using a few details you vaguely remember from Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman . If you want to make the world of your story truly come alive for your reader, you have to understand that world.

You must be able to see the sights of your world vividly in your mind. You need to be able to share the sounds, smells, voices, and cultural norms with your readers.

But, if you’re a writer first and a historian second—or let’s say 84th—this may feel like a tall order. How do you become so familiar with a timeline that was never your own and still find time to actually write your nove l ?

How do you research historical fiction thoroughly and efficiently?

Don’t worry. Yes, you have a big job ahead of you, but I’m going to lay out a strategy that will simplify your path. I’ll give you tools for:

- Prioritizing categories of research

- Immersing yourself in the world of your novel

- Checking for accuracy

- Knowing when you’re done

Let’s start with narrowing your focus.

Keep a Running List of Questions

What do you actually have to research for your specific historical fiction novel ?

If you set the perimeters too broad—”Shang Dynasty” or “Victorian England,” for example—you’re going to overwhelm yourself. You’ll also lose precious writing time learning details that aren’t relevant to your story.

Before you start your research, make a list of questions you already know you need an answer to. This could include things like:

- What would my protagonist’s day to day life look like?

- How would they dress?

- Would my protagonist’s job actually exist?

- What behaviors would shock my protagonist’s parents at this point in history?

You don’t have to think of everything upfront. You’ll make new discoveries and think of new questions both as you research and as you write. Let your research list be a growing, evolving creature.

Now, if you’re a pantser, you might find the bulk of your questions arise as you write your first draft. I still recommend creating and researching that initial list of “must knows” to avoid any plot-destroying errors as you write.

And immediately research any mid-draft discovery that has a major bearing on the trajectory of your novel.

For example, if plot point one involves a letter arriving in Egypt exactly ten days after it was written in Oklahoma, make sure such a thing is even possible at the time when your story takes place.

What if I Don’t Have a Story in Mind Yet?

Maybe you’re wondering how to research historical fiction when you have no idea what story you want to tell. Maybe you only know that you love the world of 1920s France and you’d like to set your story then and there. In that case, I’d suggest what I always suggest:

Start with what thrills you.

Why are you so enthralled with this setting? Is it jazz that draws you in? The labor movement? Josephine Baker? Croissants?

Learn more about what interests you and start imagining what kind of stories might unfold in that world.

Whether you have a story in mind or you’re building as you go, here’s how to research historical fiction, step by step.

1. Go to Google

Yeah, you probably didn’t need me for this tip. You probably already planned to use the internet to research historical fiction.

Most of us turn to Google instinctively, whether we’re looking for a casserole recipe or trying to find the name of the screechy-voice guy who was in that movie based on the book by the author who was involved in that scandal.

Go ahead and follow that impulse when you’re researching historical fiction. The Internet can save you a lot of time with quick answers to simple questions.

However, be aware that anyone can post anything online for free. It doesn’t have to be true. So make sure you’re getting your information from a reputable source. (More on that in a bit.)

2. Go Deeper at the Library

Don’t stop at Google. Remember, your goal in researching historical fiction is not just to collect information about an era. You also want to gain a well-rounded understanding of what it meant to live in that era. Your librarian can help you with this in ways Google can’t.

In addition to housing biographies and history books, your library has the hook-up for old newspapers, maps, and photographs. Through your library, you might be able to access documentaries or old radio programs.

Even if the collection at your local library is small, ask if they’re able to borrow any of the materials you’re looking for from other libraries. Your library card may also give you access to digital materials like academic journals, film libraries, archives, and more.

And if you’re really lost, tell your librarian what you need to know. “I’m writing a story about someone traveling across Scotland in the seventeenth century. I’m not sure what that would look like. Do you know of any resources that can help me?”

There’s a decent chance they’ll have something to suggest because librarians are magic.

3. Find Museums and Experts

This is where we progress from informative to immersive.

If you have the ability to visit a museum that shines light on your setting, do it. Even better, take a tour. Museum tour guides give you way more information and deeper context than you’ll find on a placard.

Meanwhile, the contents themselves help you imagine days gone by with greater clarity. You can see the texture of fabrics, the design of a tool, or photographs of daily life.

Too far from a museum that’s relevant to your setting? Consider:

- What museum would you visit if you could? Do they have any online resources? Maybe a virtual lecture series or virtual tours?

- Is there a museum nearby that features an exhibit related to your setting? Maybe you can’t get to a Japanese history museum, but you can explore Japanese art from your era in your local art museum.

- Who can tell you what a museum guide could tell me? Is there an expert on this era who might be willing to answer a few questions?

As you dig deeper, the details of your time period come into focus.

4. Collect Images and Video

Bring it all home. Photographs, paintings, furniture, clothing… whatever you’re finding out there, bring images of those things into your workspace.

Treat these images like clues about life in your chosen era. How do people dress or stand to indicate their social ranking? How are children positioned in photographs? Are they shoved into the corners or primped and paraded? How would one move in that dress or sit on that gosh-awful chair?

If there’s video footage from your era, chase that down, too.

5. Pretend You Live in Your Novel’s Timeline

You don’t have to go full-on Ren Faire. Just expose yourself to a few things that would be part of your characters’ daily lives.

Read books, newspapers, and other published materials from your chosen time period. This step is an absolute must as it not only gives you a ton of cultural insight, it also helps you nail the voice of the era. How did people talk? What were the hot topics of the day?

Music and food also provide great immersion opportunities. What sounds, scents, and flavors would have colored your characters’ daily lives?

If your novel takes place in recent history, watch the movies or television shows that were popular at the time. Check out the art that defines your chosen era.

Put yourself in the shoes of your characters (maybe literally if you have easy access to a costume shop) and see what you discover.

6. Actually Go There

This may not be realistic for you. But, if it is, you can learn a lot by visiting the physical location where your story takes place.

Wander the streets and compare them to photographs or maps from the era. If you can tour a building or home from your chosen time period, do it. Look for a local history museum.

And definitely visit the library. They may have some obscure pieces of local history you won’t find anywhere else.

Now that you know how to research historical fiction, let’s talk about something extremely important.

How to Research Historical Fiction Accurately

Misinformation and bias abound. Here’s how to navigate your research results wisely.

Always note your source. Did you find your article about Regency marriage traditions at SmithsonianMag.com? Or from KrazyKoolHistoryFacts.net? Where is your source getting their information?

Know the difference between primary and secondary sources. A primary source is anything created during the time period you’re researching—a document, a recorded interview, a shoe, whatever. A secondary source is created after the time period in question.

The U.S. Declaration of Independence is a primary source. Your grade school history book’s explanation of the Declaration is a secondary source.

Primary sources give you the most accurate account of the attitudes, voices, and direct experiences of the era. Secondary sources have enough distance to put the experience into a wider context.

On that note:

Be aware of bias. Always ask yourself what biases might be baked into both primary and secondary source material.

That’s not to say you should discount material that comes from a biased source. In fact, much of our history is colored by the people who wrote it. There’s a reason most Americans think the temperance movement was a bunch of hyper-religious spinsters nagging men to stop drinking rather than a crusade to curb domestic violence.

You can’t escape bias in your research. What matters is that you know when you’re getting a prejudiced take on history and that you seek an opposing viewpoint to get a more rounded picture.

How to Know When You’re Done

Now that you know how to research historical fiction, here are some key signs that you’re ready to start writing:

- You’ve answered all the questions that directly impact your story

- You have a pretty firm grasp of the societal norms and structures that would influence your characters and conflicts

- The setting of your historical fiction novel is starting to take shape clearly in your mind

- Anything you have to guess about now will be an easy fix if your guess is wrong

Like worldbuilding, historical fiction research can become an easy excuse to procrastinate. Get your story rolling as soon as it makes sense. You can continue researching as you go.

One final tip: Use your Dabble Story Notes to keep everything you learn organized and at your fingertips as you draft your novel.

If you don’t have a Dabble account, I highly recommend checking it out. You can do that for free for fourteen days. No credit card required. Just click this little link and start your free trial.

Abi Wurdeman is the author of Cross-Section of a Human Heart: A Memoir of Early Adulthood, as well as the novella, Holiday Gifts for Insufferable People. She also writes for film and television with her brother and writing partner, Phil Wurdeman. On occasion, Abi pretends to be a poet. One of her poems is (legally) stamped into a sidewalk in Santa Clarita, California. When she’s not writing, Abi is most likely hiking, reading, or texting her mother pictures of her houseplants to ask why they look like that.

SHARE THIS:

TAKE A BREAK FROM WRITING...

Read. learn. create..

Struggling to come up with a fresh idea for a science fiction story? Wake up your imagination with these unique sci-fi writing prompts.

Could you boosts your book's earning power and build a bigger following by publishing in foreign markets? The answer is... complicated. Here's everything you need to know about going global.

A character flaw is a fault, limitation, or weakness that can be internal or external factors that affect your character and their life.

Historical Fictions Research Network

Call for Papers online

Please find our call for papers for the 2025 Historical Research Fictions Conference in Manchester, UK below.

The Conference

Join us for the HFRN Annual Conference 2025 in Manchester, UK

Call for papers, call for submissions, workshop announcements – find out the latest

Learn more about our mission and how to join us

The Book Series

Contribute to Global Historical Fictions (Brill)

Online Workshops

We run yearly international, interdisciplinary one-day workshops in December

Meet the member of our board and find out how to get involved

Since its inceptional conference at the University of East Anglia in 2016, the Historical Fictions Research Network has been encouraging and generating conversation on line, in print and on a range of platforms about how history is constructed across a range of media and platforms. Welcoming both academics and practitioners, the HFRN aims to create a place for the discussion of all aspects of the construction of the historical narrative through its journal, annual conferences, and further activities. Previous keynotes have explored the experiences of excavations at Treblinka; the use of DNA to reconstruct historical narratives; explorations of memorial practices at battle fields; cookery as a means to explore the past; new insights resulting from a computer based re-construction of the battle of Trafalgar; and a discussion of new approaches at the Petrie Museum.

“In the Old Testament, God asked the prophet Ezekiel, ‘Can these bones live?’ He answered yes: and so do I. The task of historical fiction is to take the past out of the archive and relocate it in a body.”

Hilary Mantel (2917): “Can These Bones Live? Treading the Line Between History and Alternative Facts”

Sign up to our newsletter

Please note that we are currently moving our Newsletter to a new provider. Please visit this page again for further information.

Want to find out what’s new?

Come find us at @HistoricalFic and @historicalfic.bsky.social

Share this:

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

17 Questions to Ask When Researching for Your Novel

- Facebook Data not found. Please check your user ID. Twitter You currently have access to a subset of Twitter API v2 endpoints and limited v1.1 endpoints (e.g. media post, oauth) only. If you need access to this endpoint, you may need a different access level. You can learn more here: https://developer.twitter.com/en/portal/product Instagram Please check your username. Pinterest 234

by Sarah Sundin

When I started writing my first World War II novel, I thought I just needed to read a history book, find some cute outfits for my heroine, and have her hum a popular tune.

You may now stop laughing.

Those initial research questions ended up raising more questions. I fell in love with the era and longed to bring it alive with thorough research.

Here are seventeen questions to ask when conducting research for historical fiction. Many are also useful for contemporary novels and when building a story world for fantasy or science fiction. You will not need deep research in every area, but you should be aware of them.

- Historical events You need to know the events occurring in your era. Even if your character isn’t directly involved, she will be affected by them. Be familiar with the preceding era too.

- Setting in historical context You may know your setting now—but what was it like then? Towns grow and shrink, businesses and streets change, ethnic groups come and go.

- Schooling What was the literacy level? Who went to school and for how long? What did they study? If your character breaks the mold (the peasant who reads), how did this happen?

- Occupation Although I’m a pharmacist, writing about a pharmacist in WWII required research. How much training was required? What were the daily routines, tools, and terminology used, outfits worn? How was the occupation perceived by others?

- Community Life What clubs and volunteer organizations were popular? What were race relations like? Class relations?

- Religious Life How did religion affect personal lives and the community? What denominations were in the region? What was the culture in the church—dress, order of service, behavior? Watch out for modern views here.

- Names Research common names in that era and region. If you must use something uncommon, justify it—and have other characters react appropriately. Also research customs of address (“Mrs. Smith” or “Mary”). In many cultures, only intimate friends used your first name.

- Housing What were homes like? Floor plans, heating, lighting, plumbing? What were the standards of cleanliness? What about wall coverings and furniture? What colors, prints, and styles were popular?

- Home Life What were the roles of men, women, and children? What were the rites of courtship and marriage? Views on child rearing? How about routines for cleaning and laundry?

- Food What recipes and ingredients were used? How was food prepared? Where and when were meals eaten and how (manners, dishes)?

- Transportation How did people travel? Look into the specifics on wagons, carriages, trains, automobiles, planes. What was the route, how long did it take, and what was the travel experience like?

- Fashion Most historical writers adore this area. What were the distinctions between day and evening clothing, formal and informal? How about shoes, hats, gloves, jewelry, hairstyles, makeup? Don’t forget to clothe the men and children too!

- Communication How did people communicate over long distances? How long did letters take and how were they delivered? Did they have telegrams or telephones—if so, how were they used?

- Media How was news received? By couriers, newspapers, radio, movie newsreels, TV? How long did it take for people to learn about an event?

- Entertainment How did they spend free time? Music, books, magazines, plays, sports, dancing, games? Did people enjoy certain forms of entertainment—or shun others?

- Health Care Your characters get sick and injured, don’t they? Good. How will you treat them? Who will treat them and where? What were common diseases? Did they understand the relationship between germs and disease?

- Justice Laws change, so be familiar with laws concerning crimes committed by or against your characters. Also understand the law enforcement, court, and prison systems.

Don’t get overwhelmed or buried in research. Remember, story rules. Let the story guide your research, and let research enrich your story. Your readers will love it.

Originally published by FaithWriters, October 8, 2012, http://faithwriters.com/blog/2012/10/08/historical-research-seventeen-questions/ .

Click here for more information about the Mount Hermon Christian Writers Conference.

Update from the Advancement Team!

Velocity Bike Parks / Felton Meadow Project Draft EIR Publishing Soon!

Fantastic list of questions!!! Great stuff!!!

Thanks, Peter!

Great list of questions, Sarah! I’ll have to keep it handy. Thank you! 🙂

Thanks, Angela! I’m glad it’s useful.

Very pertinent topics. Under Transportation, I’d include animal use & care (maybe pets, too)

Under Home life, what was permissible conversation; any taboos? I suppose courtship & marriage rites include sexual more’s.

Perhaps some of this falls under Community life. And science progress of the era under Occupation.

So much to consider. Thanks for the help.

Thanks, B.D.! Great additions – I had a word-count limitation 🙂

More Than Skin Deep: Getting to Know Your Characters from the Outside In

Getting started with novellas, a writer’s sabbath in a 24/7 world.

Historical fiction: 7 elements of research

This guest contribution is by author and historical fiction blogger M.K. Tod of A Writer of History. Mary provides valuable insights into the particular research required of the historical fiction writer, along with practical advice for sourcing the factual material that will help bring a bygone era to life in your novel.

- Post author By Jordan

- 2 Comments on Historical fiction: 7 elements of research

This guest contribution is by author and historical fiction blogger M.K. Tod of A Writer of History . Mary provides valuable insights into the particular research required of the historical fiction writer, along with practical advice for sourcing the factual material that will help bring a bygone era to life in your novel.

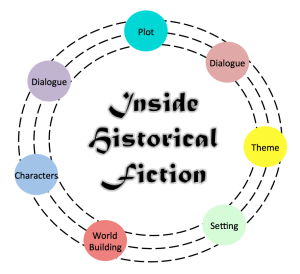

One way to examine fiction, either as writer or reader, is to consider seven critical elements: character, dialogue, setting, theme, plot, conflict, and world building. Every story succeeds or disappoints on the basis of these elements; however, historical fiction has the added challenge of bringing the past to life within each element.

Research is key. What are readers looking for? Where do you start? Below is an explanation of the seven elements of research in the context of historical fiction followed by a series of tips on researching material for your historical novel.

Character – whether real or imagined, characters behave in keeping with the era they inhabit, even if they push the boundaries. And that means discovering the norms, attitudes, beliefs and expectations of their time and station in life. A Roman slave differs from a Roman centurion, as does an innkeeper from an aristocrat in the 18th century. Your mission as writer is to find sources that will reveal the people of the past.

Dialogue – dialogue that is cumbersome and difficult to understand detracts from readers’ enjoyment of historical fiction. Dip occasionally into the vocabulary and grammatical structures of the past by inserting select words and phrases so that a reader knows s/he is in another time period without weighing down the manuscript and slowing the reader’s pace. Be careful, as many words have changed their meanings over time and could be misinterpreted.

Setting – setting is time and place. More than 75% of participants in a 2013 reader survey selected ‘to bring the past to life’ as the primary reason for reading historical fiction. Your job as a writer is to do just that. Even more critically, you need to transport your readers into the past in the first few paragraphs. Consider these opening sentences:

“I could hear a roll of muffled drums. But I could see nothing but the lacing on the bodice of the lady standing in front of me, blocking my view of the scaffold.” Philippa Gregory, The Other Boleyn Girl

“Alienor woke at dawn. The tall candle that had been left to burn all night was almost a stub, and even through the closed shutters she could hear the cockerels on roosts, walls and dung heaps, crowing the city of Poitiers awake.” Elizabeth Chadwick, The Summer Queen

“Cambridge in the fourth winter of the war. A ceaseless Siberian wind with nothing to blunt its edge whipped off the North Sea and swept low across the Fens. It rattled the signs to the air-raid shelters in Trinity New Court and battered on the boarded up windows of King’s College Chapel.” Robert Harris, Enigma

Straightaway you’re in the past. Of course, many more details of setting are revealed throughout the novel in costume, food, furniture, housing, toiletries, entertainment, landscape, architecture, conveyances, sounds, smells, tastes, and a hundred other aspects.

Theme – most themes transcend history, yet theme must still be interpreted within the context of a novel’s time period. Myfanwy Cook’s book Historical Fiction Writing: A Practical Guide and Toolkit contains a long list of typical themes: “Ambition, madness, loyalty, deception, revenge, all is not what it appears to be, love, temptation, guilt, power, fate/destiny, heroism, hope, coming of age, death, loss, friendship, patriotism.” What is loyalty in 5th century China? How does coming of age change from the perspective of ancient Egypt to that of the early twentieth century?

Plot – the plot has to make sense for the time period. And plot will often be shaped around or by the historical events taking place at that time . This is particularly true when writing about a famous historical figure. When considering such historical events, remember that you are telling a story not writing history.

Conflict – the problems faced by the characters in your story. As with theme and plot, conflict must be realistic for the chosen time and place. Readers will want to understand the reasons for the conflicts you present. An unmarried woman in the 15th century might be forced into marriage with a difficult man or the taking of religious vows. Both choices may lead to conflict.

World Building – you are building a world for your readers, hence the customs, social arrangements, family environment, governments, religious structures, international alliances, military actions, physical geography, layouts of towns and cities, and politics of the time are relevant. As Harry Sidebottom, author of Warrior of Rome series said: “The past is another country, they not only do things differently there, they think about things differently.”

“And where do I find all that?” you ask.

You could spend forever researching a particular time and place. The following suggestions come from personal experience plus a range of ideas from other authors of historical fiction:

- Read memoirs, literature written in your time period, old songs, sermons, out-of-print books, diaries and letters . These provide information on all elements: attitudes, language and idiom, household matters, material culture, everyday life, historical timelines, diversions, regulations, vehicles, travel, meals, manners and mannerisms, beliefs, morality and so on. Project Gutenberg and Fullbooks offer interesting selections of out-of-print books.

- Make sure you cover primary sources . As Elizabeth Chadwick says: “The primary sources will give you an idea of the mindset of the time – the thoughts behind the world in which your characters live – politics, social attitudes.” They illuminate your historical backdrop including wars, revolutions, major events, prominent people, and the news of the day. Find primary sources online, in libraries and in archives.

- Secondary sources include non-fiction accounts, biographies, academic papers, interviews with historians and experts. These too add understanding to the world of the past.

- Local sources, local historians and newspapers allow you to capture localities and neighbourhoods, to understand how much things cost, how long travel took, how international events affected local citizens, the things people worried and gossiped about, politics and scandals of the day.

- Old maps situate the streets and buildings of your setting and help ensure accuracy in your story. Remember, a street or building from long ago may no longer exist. What was once a footpath may now be a major roadway. For example, I consulted maps showing WWI trench locations to add authenticity to two novels, Unravelled and Lies Told in Silence.

- Personal travel offers a feel for the landscape your characters inhabit. Such personal physical connection is compelling. If that’s not possible, guidebooks and tools like Google maps and Internet photo searches are virtual ways to travel. Remember the land changes with time, so check your facts.

- Paintings give perspectives on clothing, class differentiation, social preoccupations, physical geography, architecture and other matters.

- Financial accounts help you understand what things cost.

- Transcripts of old court cases provide interesting ideas to enhance your plot, while also providing insights into the legal system and laws of the time.

- Weather records enhance the accuracy of your story with details about floods, extremes of hot or cold, monster storms.

- Museums are incredible sources of information and there are museums for just about anything. Even if you cannot personally visit a museum, some offer online exhibits, research papers, and search capabilities.

- Military records and museums are a rich trove of details.

- Newsreels are more relevant to historical fiction set in the 20th century.

- Movies about historical figures and times are a wonderful way to see and hear history. Most are carefully researched and offer ideas on fashion, morality, diversions, travel, politics, war, and home life, as well as the sounds of chariots racing, cannons exploding, the guillotine dropping. Be sure to check their accuracy. Read Now Novel’s coach and writer Arja Salafranca’s preliminary research into writing historical figures by watching the 2012 film, Die Wonderwerker .

- If you are writing about more recent times, vintage magazines, postcards, cookbooks, and brochures can also be useful.

I would be remiss if I did not mention the internet. I have purposely listed this source last, however, as I would encourage you to use it in conjunction with all of the sources mentioned above or as a means to access these sources.

A final word of advice: don’t forget that the purpose of research is to immerse yourself in the past, not overwhelm your readers with copious and irrelevant detail. Dig deep, but incorporate sparingly.

M.K. Tod writes historical fiction and blogs about all aspects of the genre at A Writer of History . Her latest novel, LIES TOLD IN SILENCE is set in WWI France and is available from all major online retailers . Her debut novel, UNRAVELLED: Two wars. Two affairs. One marriage. is also available from these retailers. Mary can be contacted on Facebook , Twitter and Goodreads .

Related Posts:

- Author interview: Joe Byrd - Monet & writing…

- Writing crime fiction - 7 elements of gripping suspense

- 5 easy ways to research your novel

- Tags guest post , historical fiction , researching your novel

Jordan is a writer, editor, community manager and product developer. He received his BA Honours in English Literature and his undergraduate in English Literature and Music from the University of Cape Town.

2 replies on “Historical fiction: 7 elements of research”

It is really a nice and helpful piece of info. I’m glad that you simply shared this helpful info with us. Thank you for sharing.!! http://goo.gl/5FcgMT

Thank you! Glad you enjoyed it.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Pin It on Pinterest

How to research a historical novel

Hannah kohler, author of the outside lands , offers some advice to anyone writing, or hoping to write, their own historical fiction..

Historical fiction can be a tricky genre to master. If you haven't done your homework it won't feel authentic but, on the other hand, no one wants to read a novel that feels like a school history lesson.

Here Hannah Kohler, author of The Outside Lands , which takes us from 1960s California to Vietnam, offers some advice to anyone writing, or hoping to write, their own historical fiction .

My first novel, The Outside Lands , is set in 1960s California and Vietnam. When I wrote it, I didn't think of it as historical fiction — the period didn't seem remote enough — although novels set more than fifty years in the past are usually defined as historical.

My second novel, Catspaw , is undeniably historical fiction: it is set in the California Gold Rush of 1849. I'm writing it in the British Library, surrounded by the library's vast and extraordinary North American collections. Shelved away in this soaring building are memoirs that will spark plot ideas, diaries that will inspire character voices, photographs that will help me visualize nineteenth-century America.

But if the library is a novelist's wonderland, it can also be a rabbit-hole — a place you can get lost for days at a time, encountering all kinds of marvels but ending up, like Alice, right back where you started. So how do you strike the balance between research and writing? Here are some things I've learned …

Don't write what you know