Narcissism Driven by Insecurity, Not Grandiose Sense of Self, New Psychology Research Shows

Narcissism is driven by insecurity, and not an inflated sense of self, finds a new study, which offers a more detailed understanding of this long-examined phenomenon and may also explain what motivates the self-focused nature of social media activity.

Narcissism is driven by insecurity, and not an inflated sense of self, finds a new study by a team of psychology researchers. Its research, which offers a more detailed understanding of this long-examined phenomenon, may also explain what motivates the self-focused nature of social media activity.

“For a long time, it was unclear why narcissists engage in unpleasant behaviors, such as self-congratulation, as it actually makes others think less of them,” explains Pascal Wallisch, a clinical associate professor in both New York University’s Department of Psychology and Center for Data Science and the senior author of the paper , which appears in the journal Personality and Individual Differences . “This has become quite prevalent in the age of social media—a behavior that’s been coined ‘flexing’.

“Our work reveals that these narcissists are not grandiose, but rather insecure, and this is how they seem to cope with their insecurities.”

“More specifically, the results suggest that narcissism is better understood as a compensatory adaptation to overcome and cover up low self-worth,” adds Mary Kowalchyk, the paper’s lead author and an NYU graduate student at the time of the study. “Narcissists are insecure, and they cope with these insecurities by flexing. This makes others like them less in the long run, thus further aggravating their insecurities, which then leads to a vicious cycle of flexing behaviors.”

The survey’s nearly 300 participants—approximately 60 percent female and 40 percent male—had a median age of 20 and answered 151 questions via computer.

The researchers examined Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD), conceptualized as excessive self-love and consisting of two subtypes, known as grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. A related affliction, psychopathy, is also characterized by a grandiose sense of self. They sought to refine the understanding of how these conditions relate.

To do so, they designed a novel measure, called PRISN ( P erformative R efinement to soothe I nsecurities about S ophisticatio N ), which produced FLEX (per F ormative se L f- E levation inde X ). FLEX captures insecurity-driven self-conceptualizations that are manifested as impression management, leading to self-elevating tendencies.

The PRISN scale includes commonly used measures to investigate social desirability (“No matter who I am talking to I am a good listener”), self-esteem (“On the whole, I am satisfied with myself”), and psychopathy (“I tend to lack remorse”). FLEX was shown to be made up of four components: impression management (“I am likely to show off if I get the chance”), the need for social validation (“It matters that I am seen at important events''), self-elevation (“I have exquisite taste”), and social dominance (“I like knowing more than other people”).

Overall, the results showed high correlations between FLEX and narcissism—but not with psychopathy. For example, the need for social validation (a FLEX metric) correlated with the reported tendency to engage in performative self-elevation (a characteristic of vulnerable narcissism). By contrast, measures of psychopathy, such as elevated levels of self-esteem, showed low correlation levels with vulnerable narcissism, implying a lack of insecurity. These findings suggest that genuine narcissists are insecure and are best described by the vulnerable narcissism subtype, whereas grandiose narcissism might be better understood as a manifestation of psychopathy.

The paper’s other authors were Helena Palmieri, an NYU psychology doctoral student at the time of the study, and Elena Conte, an NYU psychology undergraduate student.

DOI: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110780

Press Contact

September 1, 2023

14 min read

What Is Narcissism? Science Confronts a Widely Misunderstood Phenomenon

Researchers debate whether grandiosity always masks vulnerability

By Diana Kwon

Deena So’Oteh

C an you think of a narcissist? Some people might picture Donald Trump, perhaps, or Elon Musk, both of whom are often labeled as such on social media. Or maybe India's prime minister, Narendra Modi, who once wore a pinstripe suit with his own name woven in minute gold letters on each stripe over and over again.

But chances are you've encountered a narcissist, and they looked nothing like Trump, Musk or Modi. Up to 6 percent of the U.S. population, mostly men, is estimated to have had narcissistic personality disorder during some period of their lives. And the condition manifests in confoundingly different ways. People with narcissism “may be grandiose or self-loathing, extraverted or socially isolated, captains of industry or unable to maintain steady employment, model citizens or prone to antisocial activities,” according to a review paper on diagnosing the disorder.

Clinicians note several dimensions on which narcissists vary. They may function extremely well, with successful careers and vibrant social lives, or very poorly. They may (or may not) have other disorders, ranging from depression to sociopathy. And although most people are familiar with the “grandiose” version of narcissism—as displayed by an arrogant and pompous person who craves attention—the disorder also comes in a “vulnerable” or “covert” form, where individuals suffer from internal distress and fluctuations in self-esteem. What these seeming opposites have in common is an extreme preoccupation with themselves.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Most psychologists who treat patients say that grandiosity and vulnerability coexist in the same individual, showing up in different situations. Among academic psychologists, however, many contend that these two traits do not always overlap. This debate has raged for decades without resolution, most likely because of a conundrum: vulnerability is almost always present in a therapist's office, but individuals high in grandiosity are unlikely to show up for treatment. Psychologist Mary Trump deduces, from family history and close observation, that her uncle, Donald Trump, meets the criteria for narcissistic as well as, probably, antisocial personality disorder, at the extreme end of which is sociopathy. But “coming up with an accurate and comprehensive diagnosis would require a full battery of psychological and neuropsychological tests that he'll never sit for,” she notes in her book on the former president.

Now brain science is contributing to a better understanding of narcissism. It's unlikely to resolve the debate, but preliminary studies are coming down on the side of the clinicians: vulnerability indeed seems to be the hidden underside of grandiosity.

Fantasy or Reality?

Tessa, a 25-year-old who now lives in California, has sometimes felt on top of the world. “I would wake up every day and go to college believing I was going to be a famous singer and that my life was going to be fantastic,” she recalls. “I thought I could just keep perfecting myself and that someday I would end up as this amazing person surrounded by this amazing life.”

But she also hit severe emotional lows. One came when she realized that the fabulous life she imagined might never come to be. “It was one of the longest periods of depression I've ever gone through,” Tessa tells me. “I became so bitter, and I'm still working through it right now.”

That dissonance between fantasy and reality has spilled into her relationships. When speaking to other people, she often finds herself bored—and in romantic partnerships, especially, she feels disconnected from both her own and her partner's emotions. An ex-boyfriend, after breaking up, told her she'd been oblivious to the hurt she caused him by exploding in rage when he failed to meet her expectations. “I told him, ‘Your suffering felt like a cry in the wind—I didn't know you were feeling that way’ … all I could think about was how betrayed I felt,” she says. It upset her to see him connect with other people; she reacted by degrading his friends and trying to stop him from meeting them. And she hated him admiring other people because it made her question whether he'd continue to see her as admirable.

Not being able to live the idealized versions of herself—which include visions of being surrounded by friends and fans who love and idolize her for her beauty and talent—leaves Tessa profoundly distressed. “Sometimes I simultaneously feel above everything, above life itself, and also like a piece of trash on the side of the road,” she says. “I feel like I'm constantly trying to hide and cover things up. I'm constantly stressed and exhausted. I'm also constantly trying to build an inner self so I don't have to feel that way anymore.” After her parents suggested therapy, Tessa was diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) in 2023.

What makes narcissism particularly complex is that it may not always be dysfunctional. “Being socially dominant, being achievement-striving and focused on improving one's own lot in life by themselves are not all that problematic and tend to be valued by Western cultures,” notes Aidan Wright, a psychologist at the University of Michigan.

Elsa Ronningstam, a clinical psychologist at McLean Hospital in Massachusetts, says the relatively functional variety of narcissism includes having, when things are going well, a positive view of oneself and a drive to preserve one's own well-being, while still being able to maintain close relationships with others and tolerate divergences from an idealized version of oneself. Then there is “pathological” narcissism, characterized by an inability to maintain a steady sense of self-esteem. Those with this condition protect an inflated view of themselves at the expense of others and—when that view is threatened—experience anger, shame, envy and other negative emotions. They can go about living relatively normal lives and act out only in certain situations. Narcissistic personality disorder is a subtype of pathological narcissism in which someone has persistent, long-term issues. It often occurs along with other conditions, such as depression, bipolar disorder, borderline personality or antisocial personality disorder .

The 21st-century Narcissus

In the ancient Greek tale of Narcissus, a young hunter, admired for his unmatched beauty, spurns many who love and pursue him. Among them is Echo, an unfortunate nymph—who, after pulling a trick on one of the gods, has lost her ability to speak except for words already spoken by another. Though initially entranced by a voice that mirrored his own, Narcissus ultimately rejects Echo's embrace.

The god Nemesis then curses Narcissus, causing him to fall in love with his own reflection in a pool of water. Narcissus becomes hopelessly infatuated with his own image, which he believes to be another beautiful being, and becomes distraught when he finds it cannot reciprocate his affection. In some versions of the story, he wastes away before his own likeness, dying of thirst and starvation.

In the 1960s and 1970s psychoanalysts Heinz Kohut and Otto Kernberg sketched what's now known as the “mask model” of narcissism. It postulated that grandiose traits such as arrogance and assertiveness conceal feelings of insecurity and low self-esteem. The 1980 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the main reference used by clinicians in the U.S., reflected this insight by including vulnerable features in its definition of NPD, although it emphasized the grandiose ones. But some psychiatrists contended that the vulnerability criteria overlapped too much with those of other personality disorders. Borderline personality disorder (BPD), in particular, shares with NPD characteristics of vulnerability such as difficulty managing emotions, sensitivity to criticism, and unstable relationships. Subsequent versions of the DSM therefore placed even more weight on grandiose features—such as an exaggerated sense of self-importance, a preoccupation with fantasies of unlimited success and power, an excessive need for admiration and a lack of empathy.

In the early 2000s Aaron Pincus, a clinical psychologist at Pennsylvania State University, noticed that this focus on grandiosity did not accurately represent what he was seeing in narcissistic patients. “It was completely ignoring what typically drives patients to come to therapy, which is vulnerability and distress,” Pincus says. “That got me on a mission to get us more calibrated in the science.” In a 2008 review , Pincus and his colleagues discovered enormous variability in how mental health practitioners were conceptualizing NPD, with dozens of labels for the ways in which narcissism expressed itself. But there was also a common thread: descriptions of both grandiose and vulnerable ways in which the disorder showed up.

Since then, researchers have found that both dimensions of narcissism are linked to what psychologists call “antagonism,” which includes selfishness, deceitfulness and callousness. But grandiosity is associated with being assertive and attention seeking, whereas vulnerability tends to involve neuroticism and suffering from anxiety, depression and self-consciousness. Vulnerable narcissism also more often goes along with self-harm (which can include hairpulling, cutting, burning and related behaviors that are also found in people with BPD) and risk of suicide than the grandiose form.

The two manifestations of narcissism are also linked to different kinds of problems in relationships. In grandiose states, people with NPD may be more vindictive and domineering toward others, whereas in vulnerable phases they may be more withdrawn and exploitable.

Self-Esteem Juice

Jacob Skidmore, a 23-year-old with NPD who runs accounts as The Nameless Narcissist on several social media platforms, says he often flips from feeling grandiose to vulnerable, sometimes multiple times a day. If he's getting positive attention from others or achieves his goals, he experiences grandiose “highs” when he feels confident and secure. “It's almost a euphoric feeling,” he says. But when these sources of ego boosts—something he refers to as “self-esteem juice”—dry up, he finds himself slipping into lows when an overwhelming feeling of shame might stop him from even leaving his home. “I'm afraid to go outside because I feel like the world is going to judge me or something, and it's painful,” Skidmore says. “It feels like I'm being stabbed in the chest.”

The desire to fill up on self-esteem has driven many of Skidmore's more grandiose behaviors—whether it was making himself the de facto leader of multiple social groups where he referred to himself as “the Emperor” and punished those who angered him or forging relationships purely for the sake of boosting his self-esteem. Skidmore hasn't always presented himself in grandiose ways: when he was younger, he was much more outwardly sensitive and insecure. “I remember looking in the mirror and thinking about how disgusting I was and how much I hated myself,” he tells me.

Clinicians' evaluations, as well as studies in the wider population, support the idea that narcissists oscillate between these two states. In recent surveys, Wright and his graduate student Elizabeth Edershile asked hundreds of undergraduate students and community members to complete assessments that measured their levels of grandiosity and vulnerability multiple times a day over several days. They found that whereas vulnerability and grandiosity do not generally coexist in the same moment, people who are overall more grandiose also undergo periods of vulnerability—whereas those who are generally more vulnerable don't experience much grandiosity. Some studies suggest that the overlap may depend on the severity of the narcissism: clinical psychologist Emanuel Jauk of the Medical University of Graz in Austria and his colleagues found in surveys that vulnerability may be more likely to appear in highly grandiose individuals.

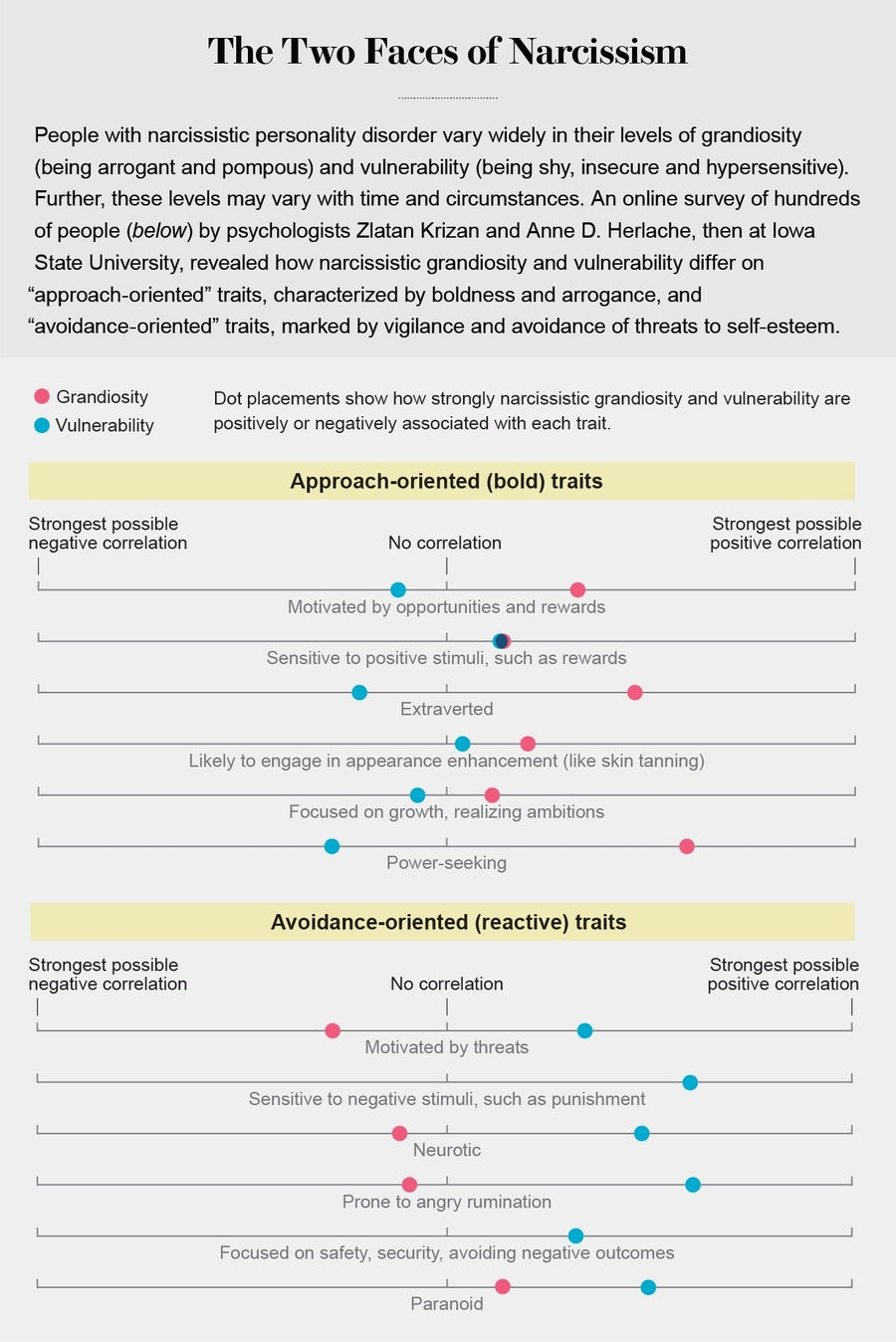

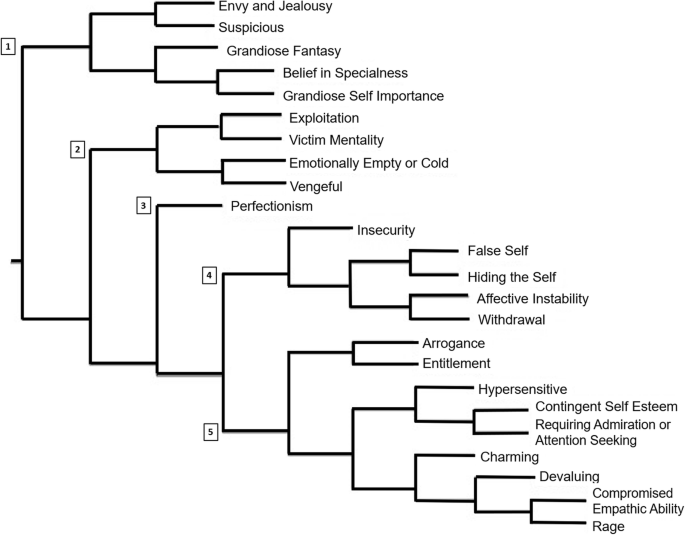

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: “The Narcissism Spectrum Model: A Synthetic View of Narcissistic Personality,” by Zlatan Krizan and Anne D. Herlache, in Personality and Social Psychology Review , Vol. 22; February 2018

To Diana Diamond, a clinical psychologist at the City University of New York, such findings suggest that the mask model is too simple. “The picture is much more complex—vulnerability and grandiosity exist in dynamic relation to each other, and they fluctuate according to what the individual is encountering in life, the stage of their own development.”

But Josh Miller, a psychologist at the University of Georgia, and others entirely reject the idea that grandiose individuals are concealing a vulnerable side. Although grandiose people may sometimes feel vulnerable, that vulnerability isn't necessarily linked to insecurities, Miller argues. “I think they feel really angry because what they cherish more than anything is a sense of superiority and status—and when that's called into question, they're going to lash back,” he adds. Psychologist Donald Lynam of Purdue University agrees: “I think people can be jerks for lots of reasons—they could simply think they're better than others or be asserting status or dominance—it's an entirely different motivation, and I think that motivation has been neglected.”

These differences in perspective may arise because different types of psychologists are studying different populations. In a 2017 study, researchers surveyed 23 clinical psychologists and 22 social and/or personality psychologists (who do not work with patients) and found that although both groups viewed grandiosity as an essential aspect of narcissism, clinical psychologists were slightly more likely to view vulnerability as being at its core .

Most narcissists who seek help are generally more vulnerable, Miller notes: “These are wounded people who come in to seek treatment for their wounds.” To him, that means clinics might not be the best place to study narcissism—at least not its grandiose aspect. It's “a little bit like trying to learn about a lion's behavior in a zoo,” he says.

The unwillingness to seek therapy is especially true of “malignant narcissists,” who, in addition to the usual characteristics, exhibit antisocial and psychopathic features such as lying chronically or enjoying inflicting pain or suffering on others.

Marianne (whose name has been changed for privacy) recalls her father, a brilliant scientist whom her own therapist deemed a malignant narcissist after reading the voluminous letters he'd sent over the years. (He never sought therapy.) It was “all about constant punishment,” Marianne says. He implemented stringent rules, such as putting a strict time limit on how long their family of five children could use the bathroom during long road trips. If, by the time he'd filled the tank, everyone hadn't returned to the car, he'd leave. On one occasion, Marianne was abandoned at a gas station when she couldn't make it back on time. “There was [hardly] a day without that kind of drama—one person being isolated, punished, humiliated, being called out,” she remembers. “If you cried, he'd say you're being histrionic. He didn't associate that crying with his actions; he thought it was performative.”

Her father also pitted her siblings and their mother against one another to prevent them from forging close connections—and he constantly looked for flaws in those around him. Marianne recalls dinner parties at home where her father spent hours trying to pinpoint weaknesses among the other husbands and to hurt couples' opinions of each other. When Marianne brought home boyfriends, her father challenged them and tried to prove that he was superior. And despite being a dazzling academic who easily charmed people when they first met, he got fired time and time again because of conflicts at the universities where he worked. “It was all about one-upmanship,” she says. “His impulse to destroy anything that was shiny, that was popular, that was loved—it overwhelmed everything else.”

Malignant narcissists often pose the greatest challenge for therapists—and they may be particularly dangerous in leadership positions, Diamond notes. They can have deficient moral functioning while exerting an enormous amount of influence on followers. “I think this is something that's going on right now, with the rise of authoritarianism worldwide,” she adds.

An Adverse Childhood?

Research with identical and nonidentical twins suggests that narcissism may be at least partially genetically heritable , but other studies indicate that dysfunctional parenting might also play a significant role. Grandiosity may derive from caregivers holding inflated views about their child's superiority, whereas vulnerability may originate in having a caregiver who was cold, neglectful, abusive or invalidating. Complicating matters, some studies find overvaluation also plays a role in vulnerable narcissism, whereas others fail to find a link between parenting and grandiosity. “Children who develop NPD may have felt seen and appreciated when they achieved or behaved in a certain way that satisfied a caregiver's expectations but ignored, dismissed or scolded when they failed to do so,” Ronningstam summarizes in her guide to the disorder.

Skidmore attributes his own NPD to both genes and painful childhood experiences. “I've never met a narcissist who has not had trauma,” he says. “People just use love as this carrot on a stick [that] they hang above your head, and they tell you to behave or they'll take it away. And so I have this mindset of, ‘Well then, screw it! I don't need love. I can take admiration, achievements, my intelligence—you can't take those things away from me.’

Many researchers nonetheless say a lot more work is needed to determine what role, if any, parenting plays. Miller points out that most research to date of grandiosity, in particular, has found small effects. Further, the work was done retrospectively—asking people to recall their past experiences—rather than prospectively to see how early life experiences affect outcomes.

There is another way to study what is going on with a narcissist, however: look inside. In a study published in 2015, researchers at the University of Michigan recruited 43 boys aged 16 or 17 and asked them to fill out the Narcissism Personality Inventory, a questionnaire that primarily measures grandiose traits. The teenagers then played Cyberball, a virtual ball-tossing game, while their brain activity was measured using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a noninvasive neuroimaging method that enables researchers to observe the brain at work.

Cyberball tests how well people deal with social exclusion. Participants are told that they're playing with two other people, although they are actually playing with a computer. In some rounds, the virtual players include the human participant; in others, the virtual players begin by tossing the ball to everyone but later pass it just between themselves—cutting the participant out of the game.

The teenagers with higher levels of grandiose narcissism turned out to have greater activity in the so-called social pain network than those with lower scores. This network is a collection of brain regions—including parts of the insula and the anterior cingulate cortex—that prior studies had found were associated with distress in the face of social exclusion. Interestingly, the researchers did not find differences in the boys' self-reports of distress. In another revealing fMRI study, Jauk and his Graz colleagues found that men (but not women) with higher levels of grandiose narcissism showed more activity in parts of the anterior cingulate cortex associated with negative emotions and social pain when viewing images of themselves compared with images of close friends or strangers.

The bodies of narcissists bear evidence of elevated stress. Studies indicate that men with more narcissism have higher levels of the stress hormone cortisol than those with less narcissism. In a 2020 study, Royce Lee, a psychiatrist at the University of Chicago, and his colleagues reported that people with NPD—as well as those with BPD—have greater concentrations of molecules associated with oxidative stress (a stress response seen at the cellular level) in their blood.

Such findings suggest that “vulnerability is always there but maybe not always expressed,” Jauk says. “And under particular circumstances, such as in the lab, you can observe signs of vulnerability at a physiological level, even if people say, ‘I don't have vulnerability.’” He adds, however, that these studies are far from the last word on the matter: many of them have a small number of subjects, and some have reported contradicting findings. Follow-up studies, ideally with a larger number of individuals, are needed to validate their results. The neuroscience of narcissism “is incredibly interesting, but at the same time, I'm very hesitant to interpret any of these results,” says Mitja Back, a psychologist at the University of Münster in Germany.

Toward Treatments

To date, there have been no randomized clinical trials for treatments specific for narcissistic personality disorder. Clinicians have, however, begun to adapt psychotherapies that have proved to be effective in other related conditions, such as borderline personality disorder. Treatments currently used include “mentalization,” which aims to help individuals make sense of both their own and others' mental states, and “transference,” which focuses on enhancing a person's ability to self-reflect, take the perspective of others and regulate their emotions. But there is still a dire need for effective treatments.

“People with pathological narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder have a reputation of not changing or dropping off from treatment,” Ronningstam says. “Instead of blaming that on them, the clinicians and researchers need to really further develop strategies that can be adjusted to the individual difference—and at the same time to focus on and promote change.”

Since discovering she has NPD, Tessa has started a YouTube channel called SpiritNarc where she posts videos about her experiences and perspectives on narcissism. “I really want the world to understand [narcissism],” she says. “I'm so sick of the narrative that's going around—people see the outside behavior and say, ‘This means these people are awful.’” What these people don't see, she adds, is the suffering that lies below the surface.

Diana Kwon is a freelance journalist who covers health and the life sciences. She is based in Berlin.

Narcissistic people aren’t just full of themselves – new research finds they’re more likely to be aggressive and violent

Professor of Communication and Psychology, The Ohio State University

PhD Student in Communication, The Ohio State University

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Ohio State University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

The Research Brief is a short take about interesting academic work.

The big idea

We recently reviewed 437 studies of narcissism and aggression involving a total of over 123,000 participants and found narcissism is related to a 21% increase in aggression and an 18% increase in violence .

Narcissism is defined as “ entitled self-importance .” The term narcissism comes from the mythical Greek character Narcissus , who fell in love with his own image reflected in still water. Aggression is defined as any behavior intended to harm another person who does not want to be harmed, whereas violence is defined as aggression that involves extreme physical harm such as injury or death.

Our review found that individuals high in narcissism are especially aggressive when provoked, but are also aggressive when they aren’t provoked. Study participants with high levels of narcissism showed high levels of physical aggression, verbal aggression, spreading gossip, bullying others and even displacing aggression against innocent bystanders. They attacked in both a hotheaded and coldblooded manner. Narcissism was related to aggression in males and females of all ages from both Western and Eastern countries.

People who think they are superior seem to have no qualms about attacking others whom they regard as inferior.

Why it matters

Research shows everyone has some level of narcissism , but some people have higher levels than others. The higher the level of narcissism, the higher the level of aggression.

People high in narcissism tend to be bad relationship partners , and they also tend to discriminate against others and to be low in empathy .

Unfortunately, narcissism is on the rise, and social media might be a contributing factor. Recent research found people who posted large numbers of selfies on social media developed a 25% rise in narcissistic traits over a four-month period. A 2019 survey by the smartphone company Honor found that 85% of people are taking more pictures of themselves than ever before . In recent years, social media has largely evolved from keeping in touch with others to flaunting for attention .

What other research is being done

One very important line of work investigates how people become narcissistic in the first place. For example, one study found that when parents overvalue, overestimate and overpraise their child’s qualities, their child tends to become more narcissistic over time. Such parents think their child is more special and entitled than other children. This study also found that if parents want their child to have healthy self-esteem instead of unhealthy narcissism, they should give unconditional warmth and love to their child.

Our review looked at the link between narcissism and aggression at the individual level. But the link also exists at the group level. Research has found that “collective narcissism” – or “my group is superior to your group” – is related to intergroup aggression , especially when one’s in-group (“us”) is threatened by an out-group (“them”).

How we do our work

Our study, called a meta-analytic review , combined data from multiple studies investigating the same topic to develop a conclusion that is statistically stronger because of the increased number of participants. A meta-analytic review can reveal patterns that aren’t obvious in any one study. It is like looking at the entire forest rather than at the individual trees.

[ Get facts about coronavirus and the latest research. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]

- Meta-analysis

- Quick reads

- New research

- Research Brief

Research Fellow

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

- Open access

- Published: 03 December 2021

Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, identity integration and self-control related to criminal behavior

- S. Bogaerts ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3776-3792 1 , 2 ,

- C. Garofalo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2306-6961 1 , 2 ,

- E. De Caluwé ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6639-6739 1 &

- M. Janković ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7385-8169 1 , 2

BMC Psychology volume 9 , Article number: 191 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

5 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Although systematic research on narcissism has been conducted for over 100 years, researchers have only recently started to distinguish between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism in relation to criminal behavior. In addition, there is some evidence suggesting that identity integration and self-control may underlie this association. Therefore, the present study aimed to develop a theory-driven hypothetical model that investigates the complex associations between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, identity integration, self-control, and criminal behavior using structural equation modeling (SEM).

The total sample ( N = 222) included 65 (29.3%) individuals convicted of criminal behavior and 157 (70.7%) participants from the community, with a mean age of 37.71 years ( SD = 13.25). Criminal behavior was a grouping variable used as a categorical outcome, whereas self-report questionnaires were used to assess grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, self-control, and identity integration.

The overall SEM model yielded good fit indices. Grandiose narcissism negatively predicted criminal behavior above and beyond the influence of identity integration and self-control. In contrast, vulnerable narcissism did not have a direct significant effect on criminal behavior, but it was indirectly and positively associated with criminal behavior via identity integration and self-control. Moreover, grandiose narcissism was positively, whereas vulnerable narcissism was negatively associated with identity integration. However, identity integration did not have a direct significant effect on criminal behavior, but it was indirectly and negatively associated with criminal behavior via self-control. Finally, self-control was, in turn, negatively related to criminal behavior.

Conclusions

We propose that both subtypes of narcissism should be carefully considered in clinical assessment and current intervention practices.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The antecedents of criminality have long been of interest to criminological researchers, as well as factors that mediate the links between them (e.g., [ 1 ]). However, most of the existing studies on personality characteristics and abilities that contribute to the development of criminal behavior have focused on single factors in relation to offending, and integration among studies has often occurred post-hoc via logical inferences (e.g., because construct X is related to construct Y, which in turn is related to criminal behavior, an indirect effect can be logically expected). In the current study, we hence proposed and tested a theory - driven model that focuses on the interplay between narcissism, identity integration, and self-control, in the explanation of criminal behavior .

Despite numerous studies on narcissism, no consensus has been reached on a widely accepted definition of narcissism [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. However, over the past 20 years, there has been broad recognition of the need to differentiate between different types of narcissism that can be roughly divided into narcissistic grandiosity and narcissistic vulnerability [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Although both subtypes of narcissism share a common deeper foundation, such as self-centeredness [ 7 ], they can have very different manifestations. Grandiose narcissism as a pathological characteristic manifests itself in exaggerated self-esteem, grandiosity and an unrealistic sense of superiority, as well as admiration seeking, entitlement and arrogance [ 4 , 6 , 8 ]. Most experts agree that grandiose narcissism is more a characteristic of the Narcissistic Personality Disorder, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 5th Edition, Section II (DSM-5; [ 9 ]), than vulnerable narcissism is [ 3 , 5 , 10 ]. In contrast, vulnerable narcissism entails pronounced self-absorbedness, low self‐esteem, hypervigilance, shyness, social withdrawal and emotional hypersensitivity [ 11 , 12 ]. Recent studies have shown that grandiose narcissism is less harmful to mental health, while vulnerable narcissism is associated with psychological problems and the use of rather inappropriate emotion regulation strategies, such as aggression and repression [ 13 ].

In general, research suggests that narcissism is quite overrepresented in samples of violent offenders (e.g., [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]), and positively associated with criminal behavior [ 18 , 19 ]. However, in the field of forensic psychology, researchers have only recently begun to investigate the difference between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism and no research to date has investigated how both forms differ from one another concerning criminal behavior. Yet, some indirect evidence emerges from studies on grandiose and vulnerable narcissism in relation to aggression, more specifically proactive and reactive aggression. While the results have been somewhat mixed , the available evidence suggests that narcissistic grandiosity is associated with both forms of aggression, while narcissistic vulnerability is associated only with reactive aggression (e.g., [ 20 , 21 , 22 ]). Compared to vulnerable narcissism, grandiose narcissism has also been more strongly associated with a wide variety of impulsivity-related externalizing behaviors, such as gambling [ 23 ], substance use [ 24 ], antisocial behaviors [ 25 ], and proactive aggression [ 26 ]. Individuals with higher levels of grandiose narcissism may have excessive confidence in their competencies and take more risks [ 27 ], probably due to their excessively active reward-oriented system (e.g., [ 28 ]). They focus more on positive outcomes and do not estimate chances and outcomes in a realistic way [ 23 ]. Additionally, aggression in individuals with higher levels of grandiose narcissism is usually seen as a self-enhancing strategy with the aim of restoring or enforcing a sense of superiority [ 29 , 30 ]. However, there is also contrasting evidence suggesting that individuals with high narcissistic vulnerability are more likely to display aggressive behavior than individuals high on grandiosity (e.g., [ 31 , 32 ]). For example, Krizan and Johar [ 31 ] found that narcissistic vulnerability (but not grandiosity) has particularly shown to be a powerful driver of rage, hostility, and aggressive behavior, fueled by suspiciousness, dejection, and angry rumination. The fragmented sense of the self and desperate need for external appreciation predisposes individuals with higher levels of vulnerable narcissism to experience shame about their narcissistic needs and unrestrained anger towards those who exposed their weaknesses [ 33 ]. This, in turn, triggers “narcissistic rage” that can further promote aggressive behavior [ 31 ]. Due to inconsistency and a scarcity of empirical evidence , additional research is needed to uncover whether and how these two subtypes of narcissism are associated with criminal behavior. Indeed, previous research has mainly focused on the link between narcissism and aggressive behavior in samples of the general population. Possible relations of different variants of narcissism with more severe forms of violent behavior (e.g., sanctioned by society) remained largely understudied.

Likewise, little is known about the mechanisms underlying the association between narcissism and criminality. According to Stern [ 34 ], the narcissistic individual is often attuned to what other individuals feel and think. This notion is closely related to the core aspect of identity, namely the fact that the individual is partly determined by interaction with his environment and must develop the ability to act effectively as an independent subject in that environment.

Identity refers to how a person defines the self and understands intimate relationships and social interactions with the social world. Identity formation is a process of alternating phases of ‘crisis and commitment’ that occur especially during adolescence [ 35 ]. Identity integration can be defined as a coherence of identity; the capacity to see oneself and one's life as stable, integrated and purposive [ 36 ]. In contrast, identity diffusion is characterized by a lack of normative commitment and reflects difficulties in maintaining a relatively constant set of goals [ 37 ]. Notably, identity diffusion does not occur in a vacuum; rather, it is an important feature that is associated with various personality dysfunctions and characterizes personality pathology [ 38 , 39 , 40 ]. According to the DSM-5 Section III [ 9 ], significant impairments in self-identity (e.g., unstable self-image, inconsistencies in values, goals, and appearance) and interpersonal functioning (e.g., being insensitive to others, inconsistent, detached, or abusive style of relating) are the main characteristics of personality disorders. In particular, identity diffusion (i.e., incoherent self-image, self-fragmentation) is one of the core components of a narcissistic personality disorder [ 41 , 42 ]. Narcissistic individuals show excessive dependency on others for identity; they need constant external support and attention to maintain their self-esteem, and self-esteem problems often shift between inflated and deflated self-appraisal [ 43 ].

Despite theoretical elaboration of the role of identity in narcissism, there is little empirical research on the association between narcissism and identity integration. However, available evidence suggests that narcissistic traits [ 41 , 44 ], and in particular narcissistic vulnerability [ 39 , 40 , 45 ], are associated with higher identity instability (i.e., a weak sense of the self). For example, Dashineau et al. [ 39 ] found that narcissistic vulnerability was associated with all forms of dysfunction (e.g., well-being, self-control, and everyday life tasks), while grandiosity was associated with specific deficits in interpersonal functioning. However, after accounting for shared variance in vulnerability, grandiosity was not associated with most aspects of poor functioning and was positively associated with better functioning in some areas, such as life satisfaction. Similarly, Huxley et al. [ 40 ] found that vulnerable narcissism was associated with impairment in self- and relational functioning, while grandiosity predicted higher self-functioning. More research is needed to investigate how both grandiose and vulnerable narcissism are associated with identity integration.

Furthermore, it has been shown that identity diffusion can result in feelings of emptiness, deviant behavior and superficiality, or other maladaptive outcomes, such as poor impulse control [ 41 , 42 ]. In the identity-value model, Berkman et al. [ 46 ] proposed that identity plays a crucial role in self-control. By its definition, identity is a relatively stable mental representation of personal and intrapersonal values, priorities, and roles. Therefore, individuals are more prone to associate their identity with long-term goals than with short-term impulses. According to this model, self-control is defined as a decision-making process that compares the subjective value of two options and selects the option with the highest value [ 46 ]. Therefore, individuals with more integrated identity are better at making choices that are relevant to their long-term goals over short-term impulses, meaning they are better at self-control.

Self-control is conceptualized as the capacity to tolerate, use and control one’s own emotions and impulses [ 36 ]. Research has shown that the degree of self-control is positively associated with adaptive correlates in various life domains, such as academic and professional success, healthier and more sustainable intimate relationships, closer social networks, greater self-awareness, empathy, and more proactive health behaviors (e.g., regular medical check-ups; [ 47 ]). In contrast, a lack of self-control is linked to a wide range of antisocial and deviant behaviors [ 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 ], and a variety of negative life outcomes, such as criminal victimization, poor health, and financial difficulties (e.g., [ 52 , 53 , 54 ]).

According to the general theory of crime [ 55 ], a lack of self-control is the main factor behind all criminal acts [ 56 , 57 ], although in this theory self-control was conceptualized in broader terms as “the differential tendency of people to avoid criminal acts whatever the circumstances in which they find themselves” [ 55 p87]. A lack of self-control was thus characterized by impulsive behavior towards others, physical risk-taking and shortsightedness, and can give rise to criminal acts in interaction with situational opportunities [ 55 ].

In sum, there is evidence that grandiose and vulnerable narcissism contribute to disintegrated identity and criminal behavior. In addition, there are indications that identity diffusion is directly associated with criminal behavior and that this association is mediated by self-control. Several studies have reported bivariate associations between pairs of these constructs, as previously reviewed. However, to our knowledge, no studies so far have investigated whether identity integration and self-control sequentially mediate the association between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism and criminal behavior.

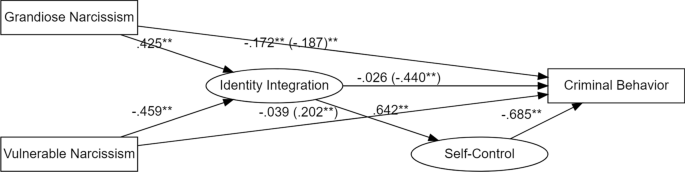

The present study

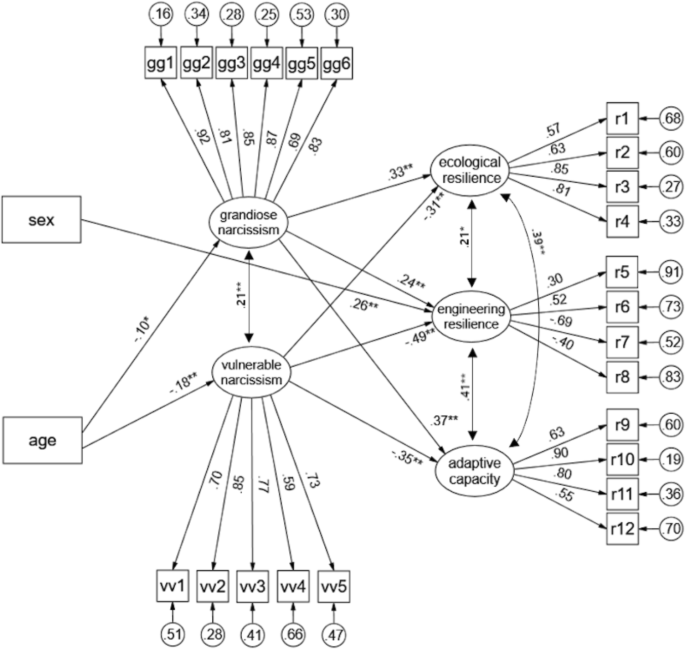

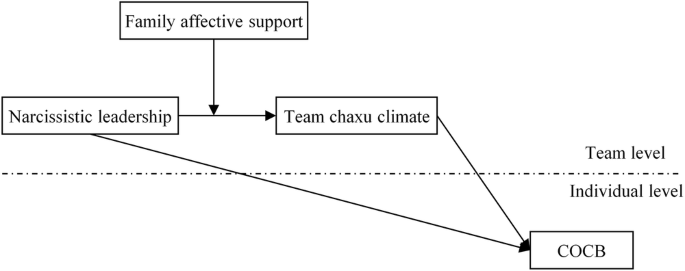

Therefore, the goal of the present study was to develop a theory-driven hypothetical model by using structural equation modeling (SEM) in a cross-section design. Although we cannot test causal relationships in a cross-sectional design, SEM is widely used in social science research to test a hypothetical conceptual model [ 58 , 59 , 60 ]. In this model (see Fig. 1 ), complex associations between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, identity integration, self-control, and criminal behavior were investigated with specific theory-driven hypotheses about the sequential mediation of identity integration and self-control in the link between narcissism and criminal behavior. First, based on the available evidence [e.g., 20 , 21 , 22 , 25 , 26 ], we hypothesized that both grandiose (path 1) and vulnerable narcissism (path 2) would be directly and positively associated with criminal behavior. However, due to the mixed empirical findings of the extent to which grandiose and vulnerable narcissism contribute to violent offending, we had no specific hypotheses as to which of both narcissistic subtypes on criminal behavior would be stronger. Second, since identity diffusion is one of the key features of a narcissistic personality disorder [ 41 , 42 ], we hypothesized that both grandiose and vulnerable narcissism would be directly and negatively associated with identity integration (path 3 and path 4, respectively). Nonetheless, this link might be expected to be weaker for grandiose narcissism, as grandiose narcissism has been documented to be associated with a narrower range of poor identity functioning and better life satisfaction compared to vulnerable narcissism [e.g., 39 , 40 ]. Furthermore, it has been shown that identity diffusion can lead to deviant behavior and a range of maladaptive outcomes such as poor impulse control [ 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 ]. It also plays a vital role in self-control and individuals with a more integrated identity are better at self-control [ 46 ]. Therefore, it was hypothesized that identity integration would have a direct negative effect on criminal behavior (path 5) and a direct positive effect on self-control (path 6). Lastly, previous research has shown that a lack of self-control is associated with a wide range of antisocial and deviant behavior [ 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 ] and is the main factor behind all criminal acts [ 55 ]. Hence, it was hypothesized that self-control would have a direct negative effect on criminal behavior (path 7). Despite supporting these direct links, the review literature also indicates that there may be indirect effects between these variables. Therefore, a series of indirect effects was assumed. Identity integration and self-control were hypothesized to mediate the association between grandiose narcissism and criminal behavior (path 8 [i.e., paths 3, 6, 7]) and between vulnerable narcissism and criminal behavior (path 9 [i.e., paths 4, 6, 7]). Finally, it was hypothesized that self-control would mediate the association between identity integration and criminal behavior (path 10 [i.e., paths 6 and 7]).

Hypothetical conceptual model. Indirect paths are in the brackets

Master level psychology students who did their clinical internship in three outpatient forensic psychiatric centers recruited the individuals convicted of criminal behavior. All offenders undergo mandatory outpatient treatment in these forensic psychiatric centers which was imposed by the judge as a result of a committed offense. Treatments mainly focused on aggression and emotion regulation based on cognitive behavioral therapy. During a therapeutic session, potential participants were asked if they were willing to participate in the study and also received an information letter. In that letter, it was clearly stated that participation was voluntary and that refusing to participate would not influence the participant’s treatment in any way. The participants had approximately one week to consider their potential participation. Participants who agreed to participate in this study were asked to complete a set of psychosocial questionnaires and were rewarded with monetary compensation of five euros. The questionnaires were completed during a treatment session to cause as little burden as possible to the offenders.

Furthermore, 22 Dutch bachelor and master level psychology students collected data in the community from October 2014 to March 2015. The survey was administered via the Qualtrics platform and made available to the general population through publishing on social media. Participants had to be at least 18 years old and have sufficient knowledge of the Dutch language. Control subjects were matched with the delinquent population on two characteristics, namely age and level of education. Participants with a university degree were excluded from the control group because this category did not appear in a sample of delinquents. After being informed of the goal and procedure of the study by an information letter, all participants signed informed consent and participated voluntarily in the study without receiving financial compensation. Before completing the survey, which included a set of validated psychosocial questionnaires, the participants were asked whether they had ever been convicted of an offense and whether a psychologist, psychotherapist or other care provider had treated them in the past 3 years. If the answer was 'yes', they could not participate in the study. After this, the questionnaires could be completed.

To guaranty anonymity, all participants were instructed to return the questionnaires in a sealed envelope after completion. The sealed envelopes and consent statements were given to the student's supervisor. The informed consent was removed before the data encoding. All procedures involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Committee of Scientific Research of FPC Kijvelanden and the local university ethics review board approved the study.

Participants

The total sample included 222 male participants. Of this sample, 65 (29.3%) were individuals convicted of criminal behavior and 157 (70.7%) were controls from the community. The mean age of the participants was 37.71 years ( SD = 13.25), ranging from 20 to 60. Most of the participants (67.6%, n = 150) had a Dutch nationality, lived alone (28.2%, n = 62) and had an income from paid employment (65.4%, n = 138). The most common finished level of education was intermediate vocational education/MBO (31.1%, n = 69), next to higher professional education/HBO (28.4%, n = 63), higher general secondary education/HVO (9%, n = 20) and secondary education/VWO (9%, n = 20). The index offenses of individuals convicted of criminal behavior included a variety of violent offenses: physical aggression (45.3%, n = 29); domestic violence (31.3%, n = 20); verbal aggression (20.3%, n = 13); and other offenses (3.1%, n = 10). More details about the demographic characteristics of the two groups can be found in the appendix (see Additional file 1 : Table S1). The questionnaire characteristics (including F tests) of the two groups are shown in Table 1 . Compared to the control group, the group of individuals convicted of criminal behavior showed significantly higher levels of vulnerable narcissism and lower levels of grandiose narcissism, self-control and identity integration.

The Dutch Narcissism scale

Narcissism was measured with the Nederlandse Narcisme Schaal ([Dutch Narcissism Scale]; NNS; [ 61 ]). The NNS is based on the Narcissistic Personality Inventory [ 62 , 63 ] and on the Hypersensitive Narcissism scale [ 64 ]. The NNS is a Dutch questionnaire that consists of 35 items measuring three different types of narcissism: vulnerable (11 items), grandiose (12 items) and isolation (12 items). The isolation subscale was not used in this study given its misalignment with our theoretical model. All items are rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “that is certainly not the case” to 7 “that is certainly the case”, with higher scores indicating greater levels of narcissism. An example of a vulnerable narcissism item is: “Small remarks of others can sometimes easily hurt my feelings”. An example of a grandiose narcissism item is: “Sometimes I feel like I got lucky with who I am anyway” [ 61 ]. The validity of the Dutch NNS was supported by its relations with age, self-esteem, burnout, and empathy [ 61 ], meaning of life [ 65 , 66 ], and depression [ 66 ], which paralleled findings obtained with other narcissism inventories. Past research has also demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) of both scales, ranging from 0.71 to 0.77 for grandiose narcissism and from 0.77 to 0.87 for vulnerable narcissism. In the current sample, the internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the grandiose and vulnerable narcissism scales was acceptable to good with Cronbach’s alpha of α = 0.71 and α = 0.81, respectively. For more details about item means and factor loadings, see Additional file 1 : Table S2 in the appendix.

The severity indices of personality problems: short form

The Severity Indices of Personality Problems—Short Form (SIPP-SF; [ 36 ]) is a 60-item self-report questionnaire derived from the SIPP-118. The SIPP-SF measures five domains of maladaptive personality functioning, namely: self-control (12 items), identity integration (12 items), relational capacities (12 items), responsibility (12 items) and social concordance (12 items). All items are rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “fully disagree” to 4 “fully agree”, with higher scores corresponding with greater levels of functioning. For the purpose of the present study, only the domains self-control and identity integration of the SIPP-SF were used. The former assesses the capacity to tolerate, use and control one’s own emotions and impulses, whereas the latter assesses the capacity to see oneself and one’s own life as stable, integrated and purposive [ 36 ]. In the current sample, both domains (i.e., self-control and identity integration) showed excellent internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α = 0.93 and α = 0.92, respectively. For more details about item means and factor loadings, see Additional file 1 : Table S3 in the appendix.

- Criminal behavior

Criminal behavior was used as a grouping variable (0 = community participants, 1 = sample of offenders), and defined as being convicted of one or more of the following offenses: physical aggression, domestic violence, verbal aggression, violent property offense and stalking. Because we could not have any a-priori theoretical expectation about distinct links with each type of offense as we had no information about the criminal history, and also to maintain statistical power, we deliberately chose this grouping variable of overall offending (referring to violent criminal behavior).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were computed by using the lavaan package in R [ 67 , 68 ] and SPSS version 25.0 [ 69 ]. To determine the bivariate associations between continuous indicators and criminal behavior (i.e., binary outcome variable), we computed the point-biserial correlations. Furthermore, to investigate the interrelation of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, identity integration, self-control and criminal behavior, path analysis was applied. Path analysis is a subset of SEM and only deals with observed variables. Path analysis was used to investigate whether the assumed theoretical model corresponds to the cross-sectional empirical model that has been studied. A model was estimated with Maximum Likelihood Estimation, which searches for parameter estimates that make probability for observed data maximal [ 70 ]. The model fit was evaluated using the following fit indices: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). The CFI compares the fit of a target model to the fit of a baseline model. Values exceeding 0.90 indicate a well-fitting model. The SRMR represents the square-root of the difference between the residuals of the sample covariance matrix and the hypothesized model. A value less than 0.08 suggests a good model fit [ 71 ]. The minimum sample size for conducting SEM is at least five observations per estimated parameter [ 72 ], which means that we had enough statistical power to detect statistically significant effects. Lastly, missing values were handled with pairwise deletion.

Correlations between all study variables including age are shown in Table 2 . Grandiose narcissism was negatively associated with criminal behavior and positively associated with identity integration and self-control. On the contrary, vulnerable narcissism was positively associated with criminal behavior and negatively associated with identity integration and self-control. Moreover, identity integration was negatively associated with criminal behavior and positively associated with self-control. Finally, self-control was negatively associated with criminal behavior. Considering age, it was negatively associated with both forms of narcissism and positively associated with self-control.

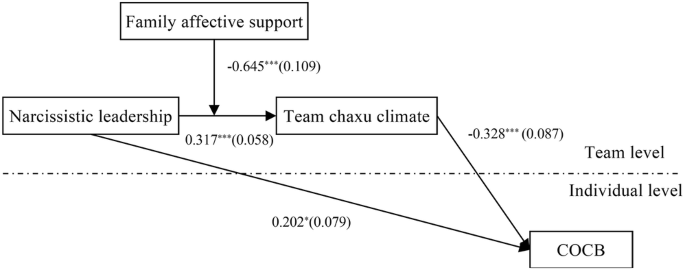

Subsequently, path analysis was performed to investigate the direct and indirect associations between narcissism (i.e., grandiose and vulnerable), identity integration, self-control, and criminal behavior. The data fit sufficiently well with the hypothetical conceptual model based on CFI = 0.98 and SRMR = 0.04. Results are summarized in Table 3 and Fig. 2 . Grandiose narcissism had a significant direct negative path to criminal behavior (path 1), whereas vulnerable narcissism appeared to be non-significantly associated with criminal behavior (path 2). Furthermore, grandiose narcissism had a significant direct positive path to identity integration (path 3), whereas vulnerable narcissism had a significant direct negative path to identity integration (path 4). In addition, identity integration did not have a significant direct path to criminal behavior (path 5), but it had a significant direct positive path to self-control (path 6). Self-control, in turn, had a significant direct negative path to criminal behavior (path 7). Moreover, considering mediating effects, the results showed that identity integration and self-control partially mediated a negative association between grandiose narcissism and criminal behavior (path 8) and fully mediated a positive association between vulnerable narcissism and criminal behavior (path 9). Finally, identity integration was indirectly and negatively associated with criminal behavior through self-control (path 10).

Standardized model results. ** Association is significant at the .01 level (2-tailed). Indirect effects are in the brackets

The present study was the first to investigate the complex associations between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, identity integration, self-control, and criminal behavior by using SEM. We hypothesized that both grandiose and vulnerable narcissism would have a direct positive effect on criminal behavior and a direct negative effect on identity integration. In addition, we expected identity integration to have a negative effect on criminal behavior, and a positive effect on self-control. Lastly, self-control was expected to be negatively associated with criminal behavior. Furthermore, different mediating effects between these associations were also hypothesized, in a sequential model connecting narcissism to identity integration, self-control, and criminal behavior, in this order. In addition, we also expected that self-control would mediate the association between identity integration and criminal behavior. Overall, the path analysis showed that the empirical model fits well with the proposed theoretical model. However, on the path-level, the results indicated that our expectations were not entirely supported.

Specifically, contrary to our expectations, we found that grandiose narcissism was not positively, but directly negatively associated with criminal behavior (path 1), whereas vulnerable narcissism did not have a significant direct effect on criminal behavior (path 2), despite a small but significant bivariate association. However, by inspecting the indirect effects, it should be noted that vulnerable narcissism was significantly positively associated with criminal behavior, but only via identity integration and self-control (path 9). The same indirect effect was significant for grandiose narcissism as well, yet in the opposite direction, however, without diminishing the direct effect of grandiose narcissism on criminal behavior (path 8). This could lead to the conclusion that higher levels of identity integration and self-control partially explained a negative association between grandiose narcissism and criminal behavior, and lower levels of identity integration and self-control fully explained the positive association between vulnerable narcissism and criminal behavior. Our result is in line with previous finding showing that grandiose narcissism is not necessarily associated with criminal behavior [ 13 ] and that narcissistic vulnerability, but not grandiosity, is a stronger indicator of aggressive behavior and hostility ([ 31 , 32 , 73 ]; but see [ 20 , 22 ]). People high on narcissistic vulnerability often use inappropriate emotion-regulating strategies, which might lead to more anger and aggression (e.g., 13, [ 31 , 32 ]). However, in the present study vulnerable narcissism predicted criminal behavior only indirectly.

A lack of a direct effect of vulnerable narcissism on delinquency (path 2) in our study might be explained by the design of the study. In other words, it is likely that previous studies that found a direct association between vulnerable narcissism and criminal behavior did not include mediators in the model. Here, with identity integration and self-control in our model, all association between vulnerable narcissism and criminal behavior goes through identity integration and self-control. It is not necessary that these individuals do not express aggression openly/directly, as the criminal behavior itself can be overt and direct. The statistical effect is not direct because we control for identity and self-control, which may be mechanisms linking vulnerable narcissism and criminal behavior.

Furthermore, the present study revealed that higher levels of grandiose narcissism and lower levels of vulnerable narcissism were associated with a more integrated identity (path 3 and 4, respectively). Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that vulnerable narcissism was associated with lower levels of identity integration. It might be that individuals high on narcissistic vulnerability have a lower integrated identity because they are more likely to maintain their self-esteem and to modulate their fragile ego by relying on the social approval of significant others [ 74 ]. It has also been shown that, with positive feedback, individuals with high levels of vulnerable narcissism can hide the negative and shameful self-image, but when external feedback is perceived as negative, they are forced to face their negative self-image and are deeply ashamed. In contrast, negative feedback does not affect the positive self-image of individuals with grandiose narcissistic traits [ 75 ].

Contrary to our expectations, grandiose narcissism was positively associated with identity integration (path 3) namely with a self-representation of oneself and one’s own life as stable, integrated, and purposive. It might be that individuals high on narcissistic grandiosity have a higher integrated identity because they are more likely to maintain their self-esteem by employing overt strategies, such as self-enhancement and devaluation of others [ 30 ]. The result may fit into previous studies showing that individuals with grandiose narcissistic traits are better adjusted compared to individuals with vulnerable narcissistic traits [ 39 , 40 , 45 , 76 , 77 , 78 ]. For example, Ng et al. [ 76 ] found that grandiose narcissism predicted higher life satisfaction and lower perceived stress, whereas vulnerable narcissism showed the opposite pattern. It has been also shown that the agentic extraversion, a characteristic of grandiose narcissism (i.e., a tendency toward assertiveness, persistence, and achievement), may serve as a protective factor against psychopathology and thus contribute to higher well-being and the “happy face” of narcissism [ 77 ]. This could explain why individuals high on grandiosity are satisfied with their lives, although they remain potentially harmful to others [ 45 ].

Furthermore, identity integration did not have a direct significant negative effect on criminal behavior (path 5), which is not in line with our hypothesis. However, identity integration was significantly negatively associated with criminal behavior, but only indirectly via self-control (path 10). Due to the fact that there was a significant negative correlation between identity integration and criminal behavior, this could lead to the conclusion that self-control fully explained the association between identity integration and delinquency. Indeed, it has been shown that individuals with higher identity integration have better self-control and are therefore less likely to engage in criminal behavior [ 46 ].

In support of this evidence, we found that better-integrated identity was associated with higher levels of self-control (path 6), which in turn was negatively related to delinquency (path 7). Identity can be seen as a strong and enduring source of value, which has an important role in determining self-regulation and self-control outcomes [ 46 ]. Our result corresponds with previous findings showing that lower identity integration can be manifested through poor self-control [ 41 , 46 ]. In addition, a lack of self-control has been linked to a wide range of antisocial and deviant behaviors [ 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 56 ]. Finally, our findings also give support to the general theory of crime [ 55 ], in which a lack of self-control represents the most important explanatory factor behind criminal behaviors.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered while interpreting the results of the present study. First, the current study was limited by operationalizing criminal behavior as a dichotomous variable, as well as by a relatively small sample of 65 offenders and 157 controls, which might negatively affect statistical power and effect size. Second, the study sample included only male participants and therefore our findings are not generalizable to the population of females. In addition, convenience sampling was used to recruit the subsample of controls and hence the generalizability of the findings cannot be entirely justified. Third, to maintain statistical power, we did not include any covariates in the analysis, which may also influence the results. In the current sample, however, age was significantly associated with both forms of narcissism and with self-control. There were also significant differences in social status, educational level and income between controls and offenders (Additional file 1 : Table S1). Future studies may consider including age and other demographic characteristics as covariates when examining these complex associations. Furthermore, different narcissism inventories operationalize grandiose narcissism differently; therefore, we can only conclude that the effects reported relate to the NNS operationalization of narcissism and call for replications with other measures of this construct. Lastly, the design of the study was cross-sectional, which does not allow us to draw causal inferences about the complex associations between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, identity integration, self-control, and criminal behavior.

Research and clinical implications

Despite the limitations mentioned above, this study could have important research and clinical implications. To the best of our knowledge, the interrelation of identity integration, narcissism, and self-control explaining criminal behavior has never been tested before. In this study, we emphasized the role of personality pathology in the development of disintegrated identity. In addition, this study demonstrated the importance of considering identity integration and self-control as significant factors underlying the association between narcissism and criminal behavior. Future studies should investigate the long-term relations between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, identity integration, self-control, and criminal behavior. The findings of the current study may be of significant value for future intervention practices. So far, most studies on narcissism in forensic psychiatry have treated narcissism as a unidimensional construct. However, there is some evidence that grandiose and vulnerable narcissism should be treated independently, as they are differently associated with adverse outcomes, such as criminal behavior, as well as victimization [ 79 ]. Therefore, the differences between these two subtypes of narcissism should be carefully considered in clinical assessment and intervention practices.

This study can deepen our understanding of the complex associations between different aspects of narcissism, identity integration, self-control, and criminal behavior. In particular, the findings of the present study revealed that grandiose narcissism can be seen as a better-adjusted subtype of narcissism, as it was associated with higher identity integration and non-criminal behavior. In contrast, vulnerable narcissism was associated with low identity integration and indirectly associated with criminal behavior. Moreover, our study showed that identity integration and self-control are important mediators in the association of both grandiose and vulnerable narcissism with criminal behavior. Finally, this research confirmed the importance of identity integration in potentially contributing to self-control, which in turn is highly relevant for deterring criminal behavior. Researchers may wish to confirm our conclusions in a larger and more representative sample, and the current study serves as a good starting point for further work.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Structural equation modeling

Nederlandse Narcisme Schaal [Dutch Narcissism Scale]

Severity indices of personality problems – short form

Severity indices of personality problems – 118

Comparative fit index

Standardized root mean square residual

Moore KJ. Prevention of crime and delinquency. Int Encycl Soc Behav Sci. 2001:2910–4.

Miller JD, Lynam DR, Hyatt CS, Campbell WK. Controversies in narcissism. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2017;13:291–315. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045244 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Miller JD, Lynam DR, Siedor L, Crowe M, Campbell WK. Consensual lay profiles of narcissism and their connection to the Five-Factor Narcissism Inventory. Psychol Assess. 2018;30:10–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000460 .

Wink P. Two faces of narcissism. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61:590–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.590 .

Cain NM, Pincus AL, Ansell EB. Narcissism at the crossroads: Phenotypic description of pathological narcissism across clinical theory, social/personality psychology, and psychiatric diagnosis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28:638–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.09.006 .

Miller JD, Campbell WK. Comparing clinical and social-personality conceptualizations of narcissism. J Pers. 2008;76:449–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00492.x .

Brown AA, Freis SD, Carroll PJ, Arkin RM. Perceived agency mediates the link between the narcissistic subtypes and self-esteem. Pers Individ Dif. 2016;90:124–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.055 .

Article Google Scholar

Pincus AL. Some comments on nomology, diagnostic process, and narcissistic personality disorder in the DSM-5 proposal for personality and personality disorders. Personal Disord Theory Res Treat. 2011;2:41–53. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021191 .

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington: Author; 2013.

Book Google Scholar

Miller JD, Hoffman BJ, Campbell WK, Pilkonis PA. An examination of the factor structure of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, narcissistic personality disorder criteria: one or two factors? Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:141–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.08.012 .

Miller JD, Hoffman BJ, Gaughan ET, Gentile B, Maples J, Keith CW. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: a nomological network analysis. J Pers. 2011;79:1013–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00711.x .

Miller JD, Price J, Gentile B, Lynam DR, Campbell WK. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism from the perspective of the interpersonal circumplex. Pers Individ Dif. 2012;53:507–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.04.026 .

Loeffler LAK, Huebben AK, Radke S, Habel U, Derntl B. The association between vulnerable/grandiose narcissism and emotion regulation. Front Psychol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.519330 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Barry CT, Loflin DC, Doucette H. Adolescent self-compassion: associations with narcissism, self-esteem, aggression, and internalizing symptoms in at-risk males. Pers Individ Dif. 2015;77:118–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.036 .

Bogaerts S, Polak M, Spreen M, Zwets A. High and low aggressive narcissism and anti-social lifestyle in relationship to impulsivity, hostility, and empathy in a group of forensic patients in the Netherlands. J Forensic Psychol Pract. 2012;12:147–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228932.2012.650144 .

Lambe S, Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Garner E, Walker J. The role of Narcissism in aggression and violence: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2018;19:209–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016650190 .

Maples JL, Miller JD, Wilson LF, Seibert LA, Few LR, Zeichner A. Narcissistic personality disorder and self-esteem: an examination of differential relations with self-report and laboratory-based aggression. J Res Pers. 2010;44:559–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2010.05.012 .

Blickle G, Schlegel A, Fassbender P, Klein U. Some personality correlates of business white-collar crime. Appl Psychol. 2006;55:220–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2006.00226.x .

Bushman BJ, Baumeister RF. Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: does self-love or self-hate lead to violence? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75:219–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.219 .

Fossati A, Borroni S, Eisenberg N, Maffei C. Relations of proactive and reactive dimensions of aggression to overt and covert narcissism in nonclinical adolescents. Aggress Behav. 2010;36:21–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20332 .

Kjærvik SL, Bushman BJ. The link between narcissism and aggression: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2021;147:477–503. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000323 .

Lobbestael J, Baumeister RF, Fiebig T, Eckel LA. The role of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism in self-reported and laboratory aggression and testosterone reactivity. Pers Individ Dif. 2014;69:22–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.05.007 .

Lakey CE, Rose P, Campbell WK, Goodie AS. Probing the link between narcissism and gambling: the mediating role of judgment and decision-making biases. J Behav Decis Mak. 2008;21:113–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.582 .

Luhtanen RK, Crocker J. Alcohol use in college students: effects of level of self-esteem, narcissism, and contingencies of self-worth. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19:99–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.99 .

Miller JD, Dir A, Gentile B, Wilson L, Pryor LR, Campbell WK. Searching for a vulnerable dark triad: comparing factor 2 psychopathy, vulnerable narcissism, and borderline personality disorder. J Pers. 2010;78:1529–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00660.x .

Vize CE, Collison KL, Crowe ML, Campbell WK, Miller JD, Lynam DR. Using dominance analysis to decompose narcissism and its relation to aggression and externalizing outcomes. Assessment. 2019;26:260–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116685811 .

Campbell WK, Goodie AS, Foster JD. Narcissism, confidence, and risk attitude. J Behav Decis Mak. 2004;17:297–311. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.475 .

Foster JD, Trimm RF. On being eager and uninhibited: narcissism and approach-avoidance motivation. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 2008;34:1004–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208316688 .

Campbell WK, Reeder GD, Sedikides C, Elliot AJ. Narcissism and comparative self-enhancement strategies. J Res Pers. 2000;34:329–47. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.2000.2282 .

Morf CC, Rhodewalt F. Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: a dynamic self-regulatory processing model. Psychol Inq. 2001;12:177–96. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1204_1 .

Krizan Z, Johar O. Narcissistic rage revisited. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;108:784–801. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000013 .

Pincus AL, Ansell EB, Pimentel CA, Cain NM, Wright AGC, Levy KN. Initial construction and validation of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory. Psychol Assess. 2009;21:365–79. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016530 .