My mother's death isn't something I survived. It's something I'm still living through.

For years, I’d assumed I would be completely incapable of functioning after my mom died. I had no idea what my life would or even could look like after that. I couldn’t imagine it, just like I couldn’t imagine, when I was a kid, what it would be like to drive a car or go to college or even just be a grown up; it felt like I would just have to cease to exist when she did.

And yet, here I am, two and a half years after my mom’s death on May 15, 2018. I don’t know if I’m thriving, or even “surthriving,” a term that makes me think of a preternaturally peppy Molly Shannon character on “Saturday Night Live.” But at least I’m no longer sleeping with the lights on while the Mel and Sue years of “The Great British Baking Show” drone on at the edges of my consciousness … most of the time, anyway.

Opinion I thought the grief of losing my husband was over. Coronavirus brought it back.

I didn’t do anything in particular to survive her death except continue to stay alive. I certainly haven’t processed the pain, and I doubt I ever fully will; it’s all simmering just beneath my skin, ready to escape at the next Instagram story from The Dodo about interspecies friendship.

Immediately after her death, there were things that had to be done — writing an obituary, canceling her credit cards and hiring an estate attorney. And I did them; they filled some time. I had help — a lawyer, friends, family, the health aide who became a second daughter to her and a sister to me. Plus Mom had been very organized; she’d even prepared a list of all of her logins for me. Logistically, it was as easy as a death could be.

The most important thing I learned about grief is that it isn’t linear, and it isn’t logical.

But at the end of the day, I was her only child. And she was my only mom. And she was gone. Just gone.

So I let her answering machine fill up with messages, because I couldn’t cope. No one sat shivah for her in Texas; I didn’t even know where to begin to organize that. I had a panic attack in the housewares section of Target.

In the months after that, I declined a lot of social invitations; I whiffed deadlines; I stayed up all night playing video games and listening to true crime podcasts by myself. In short, whatever remaining concerns I had about meeting most societal norms went out the window.

Opinion My dad died from coronavirus. I'm not just grieving — I'm angry.

It wasn’t all terrible; there were small mercies that I’ll never forget. Even when I was at my worst, my loved ones did what they could to soothe the unbearable. My friends came and sat shivah with me in New York City when I arrived home, filling my apartment with carbohydrates and flowers. They flew to me when I needed them but couldn’t say. They took me into their homes when I showed up; or they took me hiking along the Pacific Ocean or to karaoke.

Still, my grief cruelly took away my ability to concentrate on books, movies or even any TV shows that required more than the bare minimum of intellectual processing. I had nothing left to invest emotionally or intellectually in anything I normally loved — or even anything I was once pleasantly distracted by. I struggled to pitch my editors. I flubbed an interview with a celebrity so disastrously I still think about it late at night.

Eventually, I allowed myself the luxury of going to therapy twice a week instead of just once.

If this all sounds awfully familiar to you, it’s because we’re all grieving in some way.

The most important thing I learned about grief is that it isn’t linear, and it isn’t logical. You have to be very careful with yourself and with who you’re around, and you have to make sure they’re extra tender to you, too. Even the most big-hearted people will do or say the wrong thing; I still do it myself. Most of their missteps are forgivable, but you’ll decide which ones aren’t, and that’s important, too.

Special bonds were formed in the last two years between me and the friends who’ve also experienced the loss of their mothers; it’s a very particular, complicated sort of loss that can feel extra messy and ugly. And, let’s face it, not many people can tolerate hearing about the disgusting indignities of aging and death unless they get paid by the hour — nor should they. There is also a kind of relief that you feel after a death like that, and the relief feels shameful, but even the shame feels like a relief, sort of like popping a pimple.

Opinion Nearly 2 million are grieving Covid dead. That's a pandemic, too.

I’m no longer scared when the phone rings (mostly). When a famous person dies, I no longer calculate how much older or younger they were than my mom, as if that somehow affected her odds of survival. Dead parents, it turns out, are great ice breakers on first dates and at cocktail parties. I’m thankfully off the hook for airport travel over the winter holidays. When certain dates roll around — like the anniversary of my parents’ respective deaths — I’m not sad so much as simply disassociated.

If this all sounds awfully familiar to you, it’s because we’re all grieving in some way. We’ve collectively experienced wave after wave of loss in the past nine months, and it scares me to think of how shattering it will be once the constant flow of news and tragedy relents just a little.

I didn’t do anything in particular to survive her death except continue to stay alive.

This sounds horrible but, without the death of my mom — and specifically the experience of grieving her death — I wouldn’t have emotionally or mentally survived the pandemic. While I’m still no expert at tolerating discomfort, I’m better at it than I used to be; there’s not much else to do when you’re laying sideways across your bed at 4 a.m. staring at your cat and feeling desperately, bitterly lonely, except to feel desperately, bitterly lonely.

Plus, now I don’t have to worry about her during the pandemic; she had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and an increasingly knotty conflagration of disorders that would have made her an over-the-top risk for Covid-19, and she lived in Texas. She worried about me all the time anyway, even when there wasn’t an airborne virus ravaging us, and I’d have felt guilty for worrying her, and she’d want me to move back to Dallas, and, well, we’ve all seen “Grey Gardens,” right?

Opinion We want to hear what you THINK. Please submit a letter to the editor.

In the before-times, when I was on a subway stopped between stations, I’d try to sense the millisecond it began to lurch back into motion, until I could no longer tell the difference between standing still and moving. Grief is like that, but with fury and fear and sadness and a terrifying blankness that nothing can soothe. You can’t tell when the subway will start moving again; you can’t magic it into motion. You can only wait and see what happens, and make sure you’re holding on when it starts moving again.

You won’t believe the kinds of things you can survive. I didn’t. I still don’t.

More from our project on surviving 2020 and what comes next:

- THINKing about how we survived one of the worst years ever — and what happens next

- Trump's tyranny proved America isn't immune to authoritarianism. But we can survive it.

- My father's murder disrupted my schooling. But I survived and got back on track.

- Covid 'long-haul' symptoms leave survivors in emotional limbo. It's a familiar pain.

- I agreed to live alone on a desert island for a year. Here's how I stayed for eight.

- It's OK to be pessimistic about 2021. But here's how to let a little hope in.

Jenni Miller is a freelance writer who covers movies, TV, sex, love, death, video games and assorted weirdness for a variety of publications online and in print.

- Infertility

- Miscarriage & Loss

- Pre-Pregnancy Shopping Guides

- Diapering Essentials

- Bedtime & Bathtime

- Baby Clothing

- Health & Safety

- First Trimester

- Second Trimester

- Third Trimester

- Pregnancy Products

- Baby Names By Month

- Popular Baby Names

- Unique Baby Names

- Labor & Delivery

- Birth Stories

- Fourth Trimester

- Parental Leave

- Postpartum Products

- Sleep Guides & Schedules

- Feeding Guides & Schedules

- Milestone Guides

- Learn & Play

- Beauty & Style Shopping Guides

- Meal Planning & Shopping

- Entertaining

- Personal Essays

- Home Shopping Guides

- Work & Motherhood

- Family Finances & Budgeting

- State of Motherhood

- Viral & Trending

- Celebrity News

- Women’s Health

- Children’s Health

- It’s Science

Mental Health

- Health & Wellness Shopping Guide

- What To Read

- What To Watch

- Mother’s Day

- Memorial Day

- Summer prep

- Single Parenting

- Blended Families

- Community & Friendship

- Marriage & Partnerships

- Grandparents & Extended Families

- Stretch Mark Cream

- Pregnancy Pillows

- Maternity Pajamas

- Maternity Workout Clothes

- Compression Socks

- All Pregnancy Products

- Pikler Triangles

- Toddler Sleep Sacks

- Toddler Scooters

- Water Tables

- All Toddler Products

- Breastmilk Coolers

- Postpartum Pajamas

- Postpartum Underwear

- Postpartum Shapewear

- All Postpartum Products

- Kid Pajamas

- Play Couches

- Kids’ Backpacks

- Kids’ Bikes

- Kids’ Travel Gear

- All Child Products

- Baby Swaddles

- Eco-Friendly Diapers

- Baby Bathtubs

- All Baby Products

- Pregnancy-safe Skincare

- Diaper Bags

- Maternity Jeans

- Matching Family Swimwear

- Mama Necklaces

- All Beauty and Style Products

- All Classes

- Free Classes By Motherly

- Parenting & Family Topics

- Toddler Topics

- TTC & Pregnancy

- Wellness & Fitness

- Please wait..

What goes through my mind as I grieve the loss of my mom

There are a million things that change and take on new meanings and shapes. There are a million words that suddenly don't seem so nice anymore. There are a million faces that don't bring comfort like they used to.

By Katie Karambelas Updated June 15, 2022

It’s been a little over two months since I lost my mom to cancer. When I say the words “ I lost my mom ” out loud, they don’t seem right, because a lost sock can be found again. This isn’t just a missing sock. This is a huge hole in my gut , which will never, ever go away.

Losing a parent means you’ve joined a club with people who understand that just walking out the front door with your shoes on and your hair washed can be a challenge. It means that grocery shopping and picking up brussels sprouts, and remembering how much your mom loved to eat them once she realized she could cook them in the oven rather than boiling them, and they actually tasted good, makes your eyes start to burn.

Related: Mothers’ Day grief: What this day means when you’ve lost your own mom

It’s wanting to go for a run to create endorphins to stop the screaming of, “Your mom died!” that keeps running in your head over and over, but you can’t because you also want to curl up in a ball and cry while watching “Gilmore Girls” on Netflix because it was “your thing” growing up with her.

There are a million things that change and take on new meanings and shapes. There are a million words that suddenly don’t seem so nice anymore. There are a million faces that don’t bring comfort like they used to.

I know time will help. This isn’t my first loss, but it is the hardest.

So here are a few things that happen when your mom dies, in case you wanted to know where my head has been lately, or if you’re trying to figure out why your friend who lost her own mom smells like a garbage can half the time, or cries at a simple Pampers commercial.

10 things I experienced after my mom died

1. You cry a lot, and at random times.

I can’t begin to tell you how many times I’ve seen a cute commercial and started sobbing hysterically. Maybe the character’s mom was cheering them on at a soccer game, or maybe she was just giving them a hug. Literally anything that shows another mom in it will have you crying.

Don’t even get me started on walking around in public and seeing another mom with their child. I’m planning a wedding right now and almost started weeping when I was at a wedding show and they asked for mother /daughter duos to come on stage and win a prize. Sure, it wasn’t meant to hurt me, but it burned.

2. You may get closer to your dad.

This isn’t really a negative. When you lose your mom, you suddenly realize that you need your dad’s support and strength more than ever. While he’s grieving as well, there’s something special about sharing this together and being able to reminisce as a pair. You realize that you start telling your dad about your day in the same way you used to tell your mom, in hopes that maybe things will feel normal. It doesn’t, but it does help a little to know that someone still has your back, and you’re not going into every situation alone.

3. Life seems like you’re permanently wearing sunglasses, never the same brightness it was before.

I don’t know how to explain this to someone who hasn’t lost a parent. Just trust me, nothing will have the same brightness after you lose your mom. Those cute shoes at the store you were eyeing suddenly just seem like a stupid idea. That new casserole you wanted to make? Its ingredients are still at the back of the pantry collecting dust. You’ll get back in the routine someday, but it won’t be today.

4. You’ve joined a club with supportive people—one you never wanted to be in.

No one ever wants to join the “I lost a parent” club. Fortunately when you do, you’ll find that these are the people you needed in your life and they came at the perfect time. These are the people who will set their cell phone to a different ringer for you so they absolutely won’t miss your call at 2am. These are the people who let you cuss like a sailor every other word because life is just not fair anymore. These are the people who will let you still be upset a month, a year, even 10 years from now. That brings me to my next point…

5. People seem to expect you to be okay after about a week or two.

If they aren’t a part of the “I lost a parent” club, people expect you to be okay pretty fast. Once the shock of the funeral (if you had one—we didn’t) wears off, people will slowly start to forget about your pain and expect you to be normal again. It’s okay to avoid people for a little while. It’s okay to still be grieving. Remind those you love how hard this is. Sometimes people are so focused on themselves, they forget how to be a real friend .

6. You can never fully grieve because something new hits you every day.

When my mom passed away, I was on my second day of a three-week trip overseas. I had to push my grieving back because I wasn’t home and I had school and places to see. There was no funeral, so no reason to go home. My mom had wanted it this way.

Related: The hard lessons I’ve learned about grief

I tried to push through and be okay, I really did. But grief would slip out of me and I would find myself hysterically crying in the middle of a street in Dublin. When I got home, I still felt like I should be okay, at least for my son and my dad. I didn’t want them to think I was falling apart. So I held a lot of my sadness inside. It’s hard to fully grieve, especially when you’re a parent. When I’m trying to remember what ingredients my mom used in her special lasagna, I find myself grieving all over again. It never really stops, you just learn to accept it.

7. Your child’s curious words will make your heart hurt.

My son is four so death is not something he’s used to. Trying to explain to a four-year-old the idea of someone being gone is pretty impossible. We tried the “Mom-Mom is in heaven and she’s an angel and always looking down on you” stuff. And for the most part it works, but then there are the days where he’s reminding me, “Mommy, you don’t have a mom anymore,” where my heart breaks all over again. He doesn’t know it’s mean, he just says it like a statement. Because it’s true, I don’t. But man do those words hurt.

8. You’ll experience a whole new kind of pain when you start to see how much it’s affected your children.

On the flip side to him being curious, he’s also very sad. When my mom began receiving Hospice care, my son regressed and started wetting the bed at night again. We’ve tried everything to make him stop.

When I’m tucking him in and his tiny voice says things like, “I miss Mom-Mom,” or, “Why does Mom-Mom have to die?” my heart aches. He constantly brings her up and while he might not always sound sad, I can tell that this is harder on him than he lets on. I just wish I could hold all his broken pieces together so he doesn’t have to experience this kind of pain.

9. You may try to scour their phone, Facebook account, Netflix account, etc. searching for one last message, and it’ll likely drive you bonkers.

My mom and I shared a Netflix account which I now feel so thankful for. It’s weird, but all I want to do is know my mom better. I searched through her phone looking for advice. I check Netflix to see what shows she was obsessed with. I went on her Facebook account looking for answers to questions I didn’t even know I had.

I try to find notebooks with her handwriting, hoping maybe she left a note for me somewhere. It will frustrate you to do this, but you can’t help it. You just need one more piece of her, however tiny it is.

10. You’ll be jealous of everyone else who still has a mom.

(Especially when they take her for granted.) From this point forward, you shall never complain about your parent in front of me again. Because darling, you have no idea how lucky you are and how much I want to be in your shoes. Cherish them. Love them. Be thankful you have one more day with them.

Hug your babies tight. Tell your mom you love her. Seek her advice and wisdom. Don’t take these moments for granted. You only have one mom , and when she’s gone you’ll wish you’d never said an ugly word to her your whole life.

A version of this post was published on March 6, 2019. It has been updated.

Related Stories

Therapy made me a better mom—and wife

Motherly Stories

To the mama crying with her baby—the tears will flow and it’ll be okay.

Dear Mama: Your babies need a happy mom, not a perfect one

If you don’t live near your village, here’s how to create one

A mantra for mamas: ‘it’s safe to let the love get bigger’, embracing my ‘fire’—even if it embarrasses my teen, it’s science: wanting to ‘eat’ your baby makes you a better parent, our editors also recommend....

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Helpful Free Resources

- Happiness & Fun

- Healthy Habits

- Love & Relationships

- Mental Health

- Mindfulness & Peace

- Purpose & Passion

- Fun & Inspiring

- Submit a Post

- Books & Things

- Tiny Buddha’s Breaking Barriers to Self-Care

“Grief, when it comes, is nothing like we expect it to be.” ~Joan Didion

This spring marked ten years since I lost my mother . One ordinary Thursday, she didn’t show up to work, and my family spent a blur of days frantically hanging missing person fliers, driving all over New England, and hoping against reason for a happy outcome.

My mother was prone to frequent mood swings, but she also talked to my two older brothers and me multiple times a day, and going off the grid was completely out of character. How does someone just vanish? And why?

Forty days is a long time to brood over worst-case scenarios: murder, kidnap, dissociative fugue cycled through my addled mind. I gave in to despair but always managed to buoy myself up with hope . My mom was my best friend, and at twenty years old, I needed her too much to lose her. She simply had to come home.

Six weeks later, my brother called. Right up front he said he loved me—a sure sign bad news was coming. There was no way to say what he had to say next, so he just spat it out like sour milk: our mother’s body had been found.

A diver checking moorings in a cold New England harbor had spotted something white on the ocean floor. That white whale was our mom’s station wagon. She had driven off the end of a pier. We didn’t say the word suicide, but we both thought it, failed to comprehend it.

It’s been ten years since that terrible spring. Much of it still doesn’t make sense to me, but a decade has softened the rawness of my grief and allowed moments of lightness to find their way back into my life, the way sunrise creeps around the edges of a drawn window shade.

Losing someone to suicide makes you certain you’ll never see another sunrise, much less appreciate one. It isn’t true. I’m thirty years old now and my life is bigger, scarier, and more fulfilling than I ever could have imagined. Grief helped get me here.

Grief is not something you can hack. There is no listicle that can reassemble your busted heart. But I have found that grieving can make your life richer in unexpected ways. Here are ten truths the biggest loss of my life has taught me:

1. Dying is really about living.

At my mother’s memorial, I resented everyone who said some version of that old platitude, “Time heals all wounds.” Experience has taught me that time doesn’t offer a linear healing process so much as a slowly shifting perspective.

In the first raw months and years of grieving, I pushed away family and friends, afraid that they would leave too. With time, though, I’ve forged close relationships and learned to trust again. Grief wants you to go it alone, but we need others to light the way through that dark tunnel.

2. No one will fill that void.

I have a mom-shaped hole in my heart. Turns out it’s not a fatal condition, but it is a primal spot that no one will ever fill. For a long time, I worried that with the closest relationship in my life suddenly severed, I would never feel whole again. Who would ever understand me in all the ways my mother did?

These days I have strong female role models in my life, but I harbor no illusions that any of them will take my mom’s place. I’ve slowly been able to let go of the guilt that I was replacing or dishonoring her by making room for others. Healing is not an act of substituting, but of expanding, despite the holes we carry.

3. Be easy on yourself.

In the months after losing my mother, I was clumsy, forgetful and foggy. I can’t recall any of the college classes I took during that time. Part of my grieving process entailed beating myself up for what I could not control, and my brain fog felt like yet another failure.

In time, the fog lifted and my memories returned. I’ve come to see this as my mind going into survival mode with its own coping mechanisms.

Being kind to myself has never been my strong suit, and grief likes to make guilt its sidekick. Meditation, yoga , and journaling are three practices that help remind me that kindness is more powerful than listening to my inner saboteur.

4. Use whatever works.

I’m not a Buddhist, but I find the concept of letting go and not clinging to anything too tightly to be powerful.

I don’t read self-help, but I found solace in Joan Didion’s memoir The Year of Magical Thinking .

I’m not religious, but I found my voice in a campus support group run by a chaplain.

I hadn’t played soccer since I was a kid, but I joined an adult recreational league and found that I could live completely in the moment while chasing a ball around a field.

There isn’t a one-size-fits-all grieving method. Much of it comes down to flailing around until you find what works. Death is always unexpected; so too are the ways we heal.

5. Gratitude wins.

We always feel that we lost a loved one too soon. My mom gave me twenty good years. Of course I would’ve liked more time, but self-pity and gratitude are flipsides of the same coin; choosing the latter will serve you in positive ways, while the former gives you absolutely nothing.

6. Choose to thrive.

My mom and I share similar temperaments. After her death, I worried I was also destined for an unhappy outcome. This is one of the many tricks that grief plays: it makes you think you don’t deserve happiness.

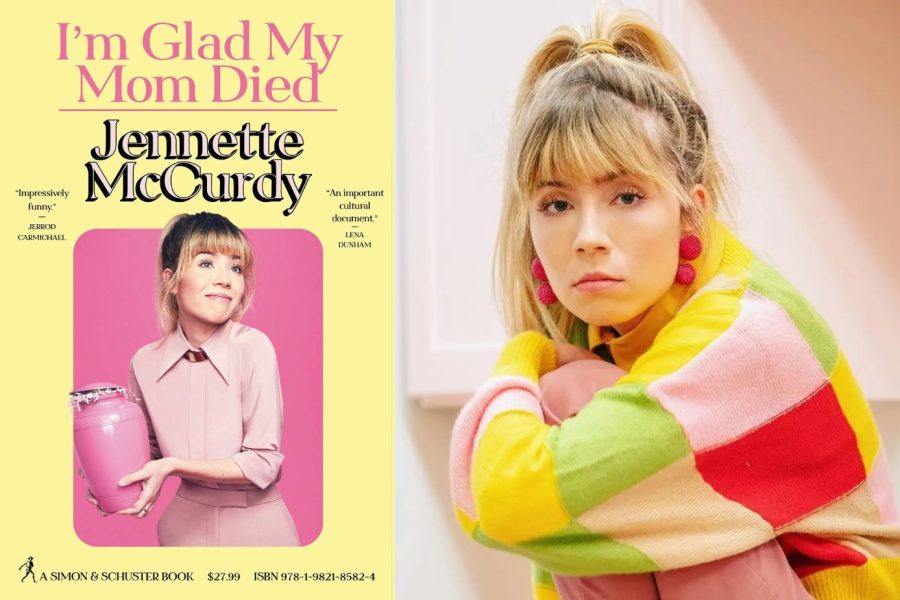

It’s easier to self-destruct than it is to practice self-care . I initially coped through alcohol and other destructive methods, but I knew this was only clouding my grieving process. I had to face the pain directly, and write my way through it. So I wrote a book.

Everyone has their own constructive coping mechanisms, and choosing those, even when it’s hard, is worth it in the long run. My mother may not have been able to find happiness in her own life, but I know she would want that for me. No one is going to water you like a plant—you have to choose to thrive.

7. Time heals, but on its own timeline.

“Time heals all wounds” is something I heard a lot at my mother’s memorial service. Here’s what I wish I had known: grief time does not operate like normal time. In the first year, the present was obscured entirely by the past. Grieving demanded that I revisit every detail leading up to losing my mom.

As I slowly started to find effective coping mechanisms, I began to feel more rooted in the present. My mood did not have to be determined by the hurts of the past.

There will always be good days and bad. This is the bargain we sign on for as humans. Once we make it through the worst days, we gain a heightened sense of appreciation for the small moments of joy to be found in normal days. Healing comes over time, but only if we’re willing to do the work of grieving.

8. Let your loss highlight your gains.

I’ve lived in New York City for eight years now, but it still shocks me that I’ve built a life that I love here. It’s a gift I attribute to my mom. She was always supportive of my stubborn desire to pursue a career as a writer. After she died, the only thing that made sense to me was to write about the experience.

This led me to grad school in New York, a place I had never even considered living before. It feels like home now. I wish I could share it with my mom, but it was her belief in me that got me here. I lost my mom, but I found a home, good friends, a career I love and the perspective to appreciate it all.

9. Heartbreak is a sign of progress.

In the first years after the big loss, I assumed romance was dead to me. Why would I allow someone else to break my heart? Luckily I got past this fear to the point where I was able to experience a long and loving relationship .

That relationship eventually imploded, but I did not, which strikes me as a sign of progress. Grief makes us better equipped to weather the other life losses that are sure to come. This is not pessimism. This is optimism that the rewards of love always trump its risks.

10. Grief makes us beginners.

Death is the only universal, and grieving makes beginners out of all of us. Yet grief affects us all in different ways. There is no instruction manual on how best to cope.

There is only time, day by day and sometimes minute by minute, to feel what works, and to cast aside what does not. In the ten years I’ve learned to live without my mother, I’ve tried to see my grieving process as an evolutionary one. Loss has enriched my life in challenging, unexpected, and maybe even beautiful ways.

About Lindsay Harrison

Lindsay Harrison is a New York based writer and editor. Her first book, Missing , was published by Simon & Schuster. When she's not writing, she's most likely playing soccer or walking her dog, who looks like a fox.

Did you enjoy this post? Please share the wisdom :)

Related posts:

Free Download: Buddha Desktop Wallpaper

Recent Forum Topics

- Don’t enjoy my best friend anymore, one of my only

- Struggling to settle in new role

- Selfish husband

- Working on stuff

- Past Hurts & Present Concerns: Advice Needed for a Stronger Bond

- Fake friend….or a jealous friend

- Why sometime it takes years to miss some one

- My GF keeps talking about her past sex life and I don’t know why it bothers me?

I Hope You Never Stay Where You’re Not Valued

GET MORE FUN & INSPIRING IMAGES & VIDEOS .

Latest Posts

How to Make Shame Your Ally

Why I’m Now Welcoming My Anxiety with Open Arms

How to Feel More in Control in Life in Four Steps

The Unseen Stories and Hidden Beauty We All Carry

Join the Writers Rising Retreat – with Anne Lamott, Cheryl Strayed & others!

This site is not intended to provide and does not constitute medical, legal, or other professional advice. The content on Tiny Buddha is designed to support, not replace, medical or psychiatric treatment. Please seek professional care if you believe you may have a condition.

Tiny Buddha, LLC may earn affiliate income from qualifying purchases, including from the Amazon Associate Program.

Before using the site, please read our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

Click to opt-out of Google Analytics tracking.

Who Runs Tiny Buddha?

Get More Tiny Buddha

- Youtube

- RSS Feed

Credits & Copyright

- Back to Top

Breathable pants, a bug bite hack and more hot Amazon finds

- TODAY Plaza

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Concert Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

My mom died and left me her best friend

I shuffled into the lobby of my New York City wedding venue, holding my gown. I was excited and anxious, but Rena hugged me and calmed my nerves. In the way that the best mothers are, she’d been a huge support to me. But she wasn’t my mother — she was her best friend.

She had been there to help me pick out my dress months earlier — and she was also there a few years later, to help soothe my grief when I mourned my difficult pregnancy loss . Rena had stood by my side for each monumental moment since the unexpected death of my mother in 2010.

It was a warm night in May — the day after Mother's Day — when I received a phone call to return to the hospital, and realized what it meant. The doctor told me my mom, whose past cancer had returned and spread, was gone. She used words I didn’t understand and explained that nothing could’ve been done. When asked if I wanted to see her one last time, I declined.

My parents divorced when I was 3, and though, in retrospect, I suspect my mother felt an underlying loneliness, she always seemed to live a full life with lots of friends. Yet at the time, Rena was one of few who knew what she had been going through with her cancer. A secret she’d initially kept even from me. While I buried my head inside of my sweatshirt and ignored the world that day at the hospital, Rena was the one who went into her room to say goodbye.

Later, she helped me make impossible decisions and unthinkable phone calls, and opened her home for Shiva after the funeral. She tended to me with love, lox and bagels, and provided a safe haven when everything felt dark and lonely.

That first night without my mom, I slept at her apartment — though my own was 20 blocks away. I stayed cradled in the fetal position in her own daughter’s bed (who was away at college), unable to sleep, knowing I’d never again experience the warmth of my mother’s arms wrapped around me.

I’d known Rena almost my entire life, but after that, the second chapter of our relationship began.

The particulars of our friendship are unique, but intergenerational relationships aren’t — 4 in 10 ten adults have a close friend at least 15 years older or younger than them, according to research from AARP. There are positive effects to having friends outside your age group on both sides. For older friends, it offers a renewed energy — for younger people, a role model. For both, it’s a chance for new inspiration, and the chance to get a different perspective. But any health benefits are a bonus for me.

Our connection to each other was forged long ago. When I was a young girl, my mom and her friend were colleagues at the prestigious FIT University in New York City: Rena, a professor, and my mom, a teacher’s assistant. They were also both divorced, with one daughter to whom they were very close, and they bonded over these commonalities.

I knew Rena as one of my mom’s closest friends. We’d been to her home for Jewish holidays, and often I’d see my mom sitting on her bed talking to her on the phone, gossiping like a schoolgirl.

Now, I’m the one on the other end of the line with Rena. Our friendship transformed from a side effect to its own organism — strong, and thriving on its own. Defined not by time or obligation, but love and support.

For me, our relationship has been most meaningful in those times when Rena knew I needed a motherly figure. Like when she accompanied me weekly to the depths of Brooklyn to be fitted for that wedding dress, offering thoughts on ways to incorporate my mom — like a garter belt made from one of mom’s hand-painted silk scarves. A secret tribute that I proudly wore under my gown.

On the best day of my life, she was there to guide and support me when my mother could not.

She was there for the worst day too, almost two years later. The morning after I lost my baby at five months pregnant, I awoke in the hospital bed to a small hand, softly grazing mine. She stood next to my husband, as her Type A personality took over, demanding stronger pain meds from my nurse — a request I’d also made that had been ignored.

I quietly mouthed thank you, when the words wouldn’t form.

“I’m always here for you, sweet girl,” she replied, out loud.

Next to her, on a table, was a brown bag filled with hot bagels from which I could see steam literally rising. Breakfast was the last thing on my mind, but the smell brought me comfort.

Food was her love language, and once again she expressed that love through bagels as she lovingly slathered one with scallion cream cheese and placed it on my tray. I felt love circulating through my veins. It was a small reminder that I was still alive, and despite what my brain said, I was not alone.

The last decade has been filled with chats, messages, mutual support and encouragement between the two of us. We’ve reciprocated flowers, phone check-ins, and the simultaneous grabbing of a dinner bill.

I’ve always tried to remember that even though Rena is filling an impossible void for me, she has her own busy life, including a grown daughter who I don’t know well, beyond the secondhand stories I hear about her life. I always feel immense gratitude that she allows me to share her mother at times.

At times, I’ve wondered if I can ever give back to Rena as much as she’s given me. Her presence helps fill a vacancy, whereas the role I play in her life fills an extra space in her heart, as opposed to an empty one.

That night in the hospital, now more than a decade ago, she lost a friend, and I lost a mother and an irreplaceable relationship. It’s an absence that I have felt more profoundly in recent years, as I’ve struggled to become a mother myself.

I have a few maternal figures in my life, including my mother-in-law. But my relationship with Rena has given me peace of mind in the present, and a touchstone to the past that no other woman possesses.

Having her in my life has provided a feeling of safety and home, from the happiest to the hardest moments — planning both a funeral and a wedding.

I’ve learned true connection comes in all shapes and sizes and isn’t confined by typical standards. The friendship between my mom and her is in the past, but it continues on, evolving, through our friendship now.

Do you have a personal essay to share with TODAY? Please send your ideas to [email protected] .

Blake Turck is a freelance writer and New York City native. She can be found most nights watching movies on the couch with her husband and 5-year-old goldendoodle, Chief Brody, or on Twitter at twitter.com/styleisland .

My on-again, off-again relationship with Mother’s Day

What we don’t talk about when we talk about becoming a mother

I dreaded Mother’s Day after my son died. Then I learned to play again

I loved raising a teenager. But I had no idea it would be so hard when he left

At 57, a bet led to my first tattoo on Mother’s Day

For 23 years, I was Caroline. Here’s why I reclaimed my Chinese birth name.

How I chose my kids' Indian names so my husband could pronounce them

Our son died by suicide 2 years ago. We’re still waiting for him at the dinner table

It took me 10 years of fertility treatments to have 2 kids. I’d do it all again

IVF ruined my life. What I learned from years of failed fertility treatments

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

A week ago, my mother died. The feeling of loss is unbearably intense

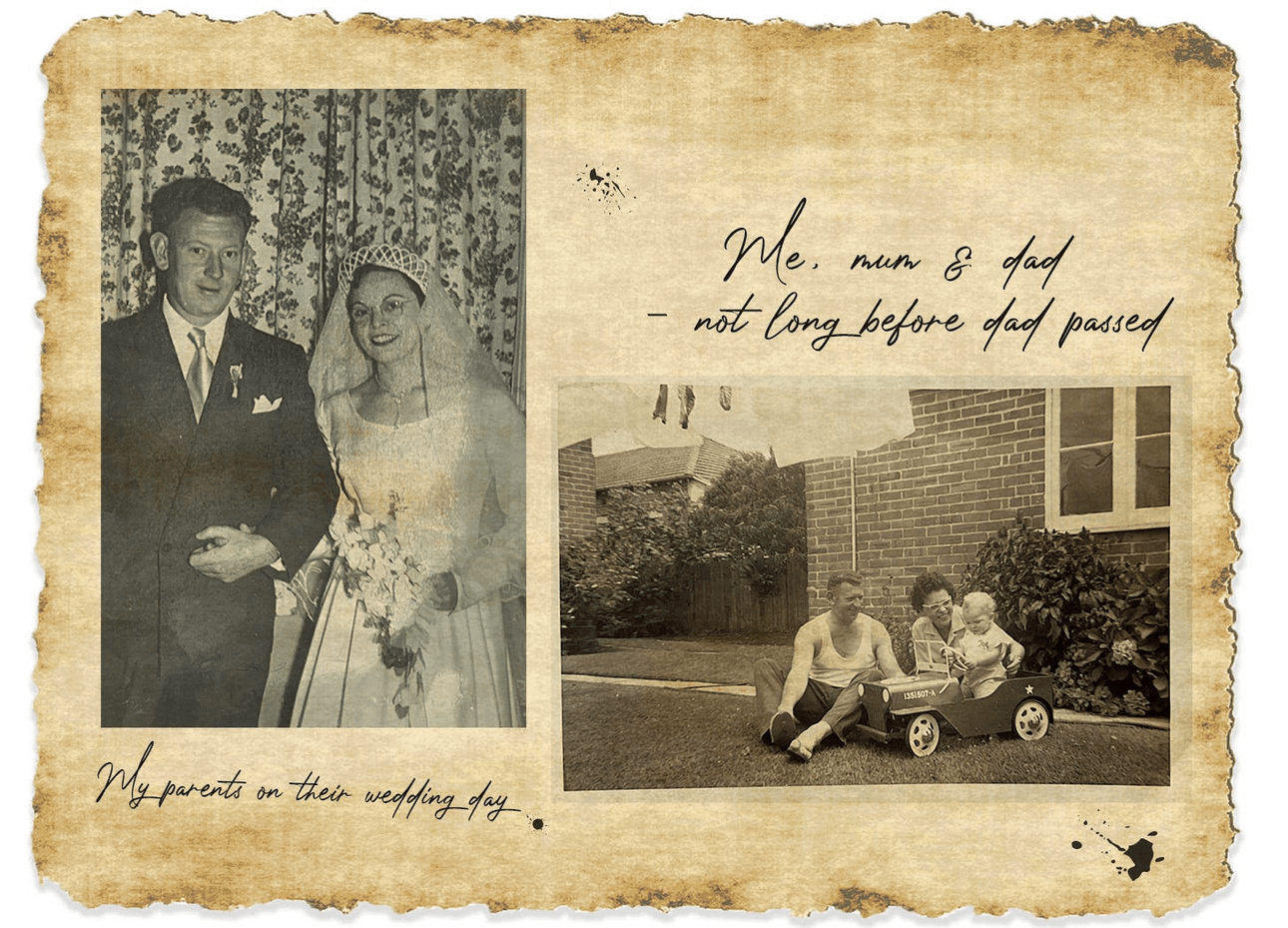

N obody wants their parents to outlive them. It's not the way it should be. The thought of any parent having to bury their child is so awful, so bleak. Yet that doesn't make it any more easy to lose your mum and dad. My mum, Winifred, died last Saturday, just over five and a half years after my dad, John. A 50-year-old orphan is hadly the stuff of grand tragedy. Yet the feeling of bereavement is so intense that it's virtually unbearable. My younger brother, Dave, feels just the same.

My mother suffered hugely before she died, and you'd think that would make it easier, knowing that her pain has ended. But it doesn't. Instead, the thought of how she spent the last eight months, with her illness – renal cancer that had spread to her spine – dominating utterly, robbing her gradually of every pleasure, every activity, every independence, before it stopped toying with her and allowed her to go, is torture.

Worse, she'd never in the least been able to come to terms with the death of my father. So, although she still had happy times, she never stopped missing him, yearning for him, really. That Win struggled on for those years, carrying that huge emotional burden, only to be dealt the blow of having to face a lingering death without him beside her, is wretched beyond belief.

One very cruel aspect of things was that my mother's death was in too many ways a protracted replay of my father's. Both of them turned up at the A&E department of the local hospital, in agony too excruciating to bear any longer, having complained of pain to their GPs for many months. Both received the diagnosis of the disease that would kill them during that trip, in that hospital. I was with my mum and dad when he was told that he didn't have digestive trouble after all, but incurable secondary cancer that had spread from his oesophagus to his liver. John was told that people in his situation tended to survive for another four months, and he survived that long, almost to the minute. He spent his last weeks in a hospice, the hospice that my mother also died in. Except that she sat by his side every day. Desperately as he would have wanted to, John wasn't able to do that for her. None of her family were. We visited as much as we could, but none of us could be a constant, daily support, at her side for every miserable development, in the way that she had been there for him.

We'd tried to persuade my mum to come south to live after John had gone. She was from Essex, and my brother's in London, too, not far from me. But while she was always distraught when our frequent visits came to an end, she couldn't face the idea of leaving the home she had shared with John since the beginning of the 1970s. She lived with her memories and they pretty much engulfed her. But she couldn't let them go, or let go of the people and places that had been part of their daily life as a couple, and whose continuing presence comforted her.

Anyway, she'd never liked travelling and neither had my dad – despite the fact that they'd travelled all the way from Essex to Scotland to start their married life on my dad's Lambretta. Eventually, Win stopped taking the train to London, even at Christmas, and stopped wanting to leave the house for more than a few hours. This time last year, I'd booked a holiday for us all in Mull. But when we went to pick her up and drive her there, she said at the last minute that she didn't want to go. It was a wonderful holiday, even without her. I wished so much that she had been there, with her grandchildren, in all that beauty. It exasperated me that she'd ducked it like that. Now, I see that she must already have been feeling much more ill than anyone realised.

When the consultant first called me, in November, explaining that Win had a tumour in her spine, that could be shrunk to relieve the pain but not removed, my first reaction was to try to have her transferred south. At that point, she thought her life would return to something like normal, as it more or less had after she'd had a kidney removed almost three years before. We did try to look after her in her own home, as Win so ardently wished, but eight days was the longest single stretch that she coped with at home. She was just too ill, too helpless. Every moment physically hurt. Next, I tried having her moved to my place in London. After a lot of discussion, she eventually decided not to do it, just a few weeks ago. In a way, it was a relief, even though I'd hoped to take her on excursions and what-not once she was down here.

On my last visit to her, a couple of weeks ago, my mum had rallied a bit, and I hired a wheelchair cab to take us from the hospice to New Lanark, a place we'd loved as a family when we were kids, and had always carried on visiting. The Christmas before Dad died, he'd walked with us all the way up to the top of the Falls of Clyde.

Even though it rained, we had a great time. Win bought and wore a new scarf, and she wore lipstick for the first time in months, and looked pretty again. We watched the Falls and talked about John. We had lunch, probably the last meal she actually enjoyed. I had wanted her last months to be full of treats like this. But instead I wasted my time, dreaming that all this would happen once she was in London.

It wasn't until she'd gone that I realised Win's refusal to move was probably right. These last few days, as Dave and I have slowly begun attending to the task of sorting out their things at home, have shown me that it was this, above all, that Win couldn't face. The ploughing through of a lifetime of mementos, deciding which had to stay and which could go – it's all so touching, so heartbreaking. I was moved to tears by a little paperback book called Winter Health that had been a fixture around the house when I was a toddler, and which, of course, I'd forgotten about. It's when you can't work out why these things were hung on to that it all seems most poignant.

Maybe because the second world war, and rationing, had dominated the childhood of my parents, they were careful with things. My mum got a glass jug with matching tumblers as a wedding present – really nice. But the glass was delicate, and a couple of them got broken. So the rest went into the cupboard, for safety, and now that jug and the remaining tumblers have outlasted them both. Win and John so often saved things for best, or for the future. They have both run out of future.

I've had a difficult relationship with my mother – who was very much a traditional woman in many ways – ever since I insisted on going to university, having a career, all that. In a way, that's what the ongoing travel-struggle was about. Win always thought that since I'd been the one who'd insisted on leaving, it was up to me to make the effort to keep the relationship going. She didn't seem much interested in hearing about my work, and I resented that, the feeling that she disapproved. Hidden away in the cupboards, I found loads of clippings, even copies of old trade magazines that I worked on in my early 20s, none of which I'd even kept myself. Yet, this is the first time in my life that I've even been able to write a personal piece without fretting that my mother might see it and take umbrage, which she did quite frequently. It does not feel like much of a liberation.

My mum left a lovely note for us, saying that although she had indeed suffered greatly in her loss of John, it had been wonderful to love and be loved with such constance and profoundity. She told us all how much she adored us. I want so much to lay my forehead against hers and tell her that she is adored in return. But it's too late now.

- Death and dying

Clearing out my parents' house for the final time brought a certain serenity

Where Memories Go: Why Dementia Changes Everything by Sally Magnusson – review

Births, marriages, deaths: A day in the life of the register office

Most viewed.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Deal With the Death of a Mother

Theodora Blanchfield is an Associate Marriage and Family Therapist and mental health writer using her experiences to help others. She holds a master's degree in clinical psychology from Antioch University and is a board member of Still I Run, a non-profit for runners raising mental health awareness. Theodora has been published on sites including Women's Health, Bustle, Healthline, and more and quoted in sites including the New York Times, Shape, and Marie Claire.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/theodorablanchfieldamft-50c6fe570e584649b5dbc17eb08b5bbf.jpg)

Daniel B. Block, MD, is an award-winning, board-certified psychiatrist who operates a private practice in Pennsylvania.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/block-8924ca72ff94426d940e8f7e639e3942.jpg)

EMS-FORSTER-PRODUCTIONS / Getty Images

The death of one's mother is one of the hardest things most people will go through in life. Whether you two had a great relationship, a strained relationship, or something in between, this event will likely have a significant impact on your life.

In one survey, between 20% to 30% of participants stated that losing a loved one was the most traumatic event in their lives—even among those who had reported 11 or more traumatic events over the course of their life. For that group, 22% still ranked the loss of a loved one as their most traumatic event.

Why the Death of One's Mother Is So Hard

Whether you are grieving the death of a mother who birthed you or a mother (or mother figure) who raised you, you are either grieving the bond you had or the bond you wish you had.

John Bowlby , a British psychologist, believed that children are born with a drive to seek attachment with their caregivers. While others before him believed that attachment was food-motivated, he believed that attachment formed based on nurturing and responsiveness.

Therefore, it makes sense that grieving that attachment—or lack thereof—would be incredibly difficult.

A mother is such an integral part of our lives in our society, in part because we are not raised in communities with a variety of caretakers,” says Liz Schmitz-Binnall, PsyD, who has done research on mother loss and resilience.

Her research specifically focused on adult women who had lost their mothers as children and found that they scored lower on resilience than those who had not lost mothers as children.

She says she sees many people who didn’t have a good relationship with their mother but are surprised at the strength of their grief reaction following their mother’s death.

How a Mother's Death Can Affect Someone

While mother loss differs from other losses in some key ways, some of the same effects that come from any kind of loss or bereavement are present. Some thoughts and feelings typical of grief:

- Difficulty concentrating

Less known is that grief can show up physically , in addition to the more-known mental or spiritual indications. In your body, grief may look like:

- Digestive problems

- Energy loss

- Nervousness

- Sleep disturbances

- Weight changes

Risk of Psychiatric Disorders

In others, however, a loss of a loved one may activate mental health disorders even in those with no history of mental illness. One study found an increased risk for the following disorders, in addition to discovering a new link between mania and loss:

- Major depressive disorder

- Panic disorder

- Posttraumatic disorder

Specifically in adults over the age of 70:

- Manic episodes

- Alcohol use disorders

- Generalized anxiety disorder

What Is Complex Bereavement?

All grief is complex, but upon losing someone, many people are able to slowly readjust to their daily routines (or create new routines). Mental health professionals may call it complicated or complex bereavement if it has been at least a year and your daily function is still significantly impacted.

(Note: the current clinical name is Persistent Complex Bereavement Disorder, but the American Psychiatric Association recently approved a change of name to Prolonged Grief Disorder. )

Some of the signs of prolonged grief are the following symptoms still significantly impacting your daily functioning after 12 months:

- Difficulty moving on with life

- Emotional numbness

- Thoughts that life is meaningless

- A marked sense of disbelief about the death

In one study, 65% of participants with complicated grief had thought about wanting to die themselves after losing a loved one. So if you, or someone you know who is grieving, is having suicidal thoughts, know that you aren’t alone and this is not uncommon for what you are going through.

If you are having suicidal thoughts but feel you can keep yourself safe, you should talk to a mental health professional. If the thoughts become unbearable and you are in imminent danger of hurting yourself, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 for support from a counselor who is trained in this.

How to Heal from the Death of a Mother

When loss is fresh, it feels like you will feel that way forever—but you won’t.

“If you allow yourself to grieve, and if others allow you to grieve,” says Schmitz-Binnall, “you will probably notice that the really intense feelings will lessen during the first few months after the death of your mother.”

She says that while most people intuitively realize it can be hard to lose a mother, they don’t realize quite how hard it can be—or how long it can take. “People in our society often think we can move through grief in a month and be done with it.”

And even if we don’t acknowledge those feelings, that doesn’t mean they aren’t existing and impacting our lives anyway.

Liz Schmitz-Binnall

Too many people push us to ‘get on with life’ too soon after a significant loss. We need to be able to grieve, but...we also need to adjust our expectations of ourselves.

Some of her tips:

- Feel the feelings

- Or let yourself feel nothing

- Talk about your feelings

- Spend time by yourself

- Spend time with others

- Talk to her (in whatever way that means for you and your beliefs—it may also include writing letters to her.)

Talk to a Professional

Therapy can be helpful after a major loss like this. While most therapists will have worked with grief, as it's one of the most universal life experiences, there are also therapists who specialize in working with clients with grief. To find one, search for grief therapist or grief counselor in your area.

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, BetterHelp, and ReGain. Find out which option is the best for you.

Find a Community

Since grief can feel like such an isolating experience, many find comfort in support groups, whether they be in-person or an online support group. If you are a woman who has lost a mother, you may be interested in the Motherless Daughters community , which is both virtual and has offline meetups.

A Word From Verywell

The death of a mother is one of the most traumatic things someone can experience. If you are currently grieving your mother, give yourself grace. Whether you had a good relationship or not with her, there will always be grief associated with either the actual relationship you had or the one you wish you had.

Hasin DS, Grant BF. The national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions (Nesarc) waves 1 and 2: review and summary of findings . Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol . 2015;50(11):1609-1640. doi:10.1007/s00127-015-1088-0

Schmitz-Binnall E. Resilience in adult women who experienced early mother loss . All Antioch University Dissertations & Theses .

- Keyes KM, Pratt C, Galea S, McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Shear MK. The burden of loss: unexpected death of a loved one and psychiatric disorders across the life course in a national study . AJP . 2014;171(8):864-871. doi:10.4088/jcp.v67n0209

- Szanto K, Shear MK, Houck PR, et al. Indirect self-destructive behavior and overt suicidality in patients with complicated grief. J Clin Psychiatry . 2006;67(2):233-239. doi:10.4088/jcp.v67n0209

By Theodora Blanchfield, AMFT Theodora Blanchfield is an Associate Marriage and Family Therapist and mental health writer using her experiences to help others. She holds a master's degree in clinical psychology from Antioch University and is a board member of Still I Run, a non-profit for runners raising mental health awareness. Theodora has been published on sites including Women's Health, Bustle, Healthline, and more and quoted in sites including the New York Times, Shape, and Marie Claire.

- Dealing with Grief

- Online Grief Counseling

- Loss of Parents

- Loss of Spouse

- Loss of Siblings

- Loss of Children

- Children and Grief

- Relationship Grief

- Alzheimer's Grief

- Disenfranchised Grief

- Coping with Suicide

- Other Types of Grief

- Stories of Grief

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Grief Forum

- Planning a Funeral

- Funeral Flowers

- Funeral Poems

- Funeral Eulogies

- Funeral Caskets and Urns

- Sympathy Gifts

- Sympathy Baskets

- Sympathy Cards

- Words of Sympathy

- Memorial Jewelry

- Memorial Trees

- Pet Loss Grief

- Pet Memorial Jewelry

- Pet Sympathy Cards and Gifts

Online Counseling

Keepsake Store

How to Cope with the Loss of Your Mother

For many people the loss of their mother is harder than the loss of their father. Not because they loved them any less, but the bond between mother and child is a special one. Your mother gave birth to you. She fed you and nurtured you throughout your childhood. The mother is one who tends to have the most responsibility for the care of the child, and is at home with the children more often than the father in most cases.

Your mother is the one you turn to when you break up with your first boyfriend or girlfriend, when you need advice or when you have a problem. Your mother is not only your greatest advocate, she is part of you. You might even look like her. She might be your best friend as well as your mother. It is like losing a part of yourself.

No-one is ever as interested in everything you do as your mother, or as proud of you.

Grief for your mother is one of the hardest things we face in life

Mothers tend to hold families together. They are the ones who keep in touch with all the family members and spread the news around. They are the ones who arrange get togethers, keep the family home together, and generally are the hub of family life. Once the mother is gone, the family either fragments or you have to step in to her role as the main communicator and organiser.

Even if you didn't have the perfect relationship with your mother, her loss can be just as devastating. You no longer have the chance to put things right, to hear her say I love you, or I'm proud of you.

Although the loss of a parent is a normal part of growing up, and it happens to everyone, it is no less devastating. But many people are surprised at how much it affects them. Their friends and family perhaps won't realise just how big a blow it can be, especially if they were old or ill for a long time and it was expected.

Grief for the death of a mother is one of the hardest things we face in life, but nearly all of us have to face it at some time. Everyone's grief is different, and we all have our own ways of coping. We may feel some or all of the emotions of grief at times, or we might just feel numb and blank.

When I lost my own mother I went into denial. It was easy to bury what had happened because I was living far away and had two young children to cope with. Have a read of my story about how I failed to grieve properly here.

The importance of support after the loss of your mother

If you are lucky enough to have a close family member or friend in whom you can confide, you may be able to grieve without needing any extra help. Some people, for various reasons, may need some more professional guidance if they get stuck in their grief or don't have any close support network.

Here are a few of our recommendations for getting help:

Find out if you need grief counseling here

Download a hypnosis session - Death of a Parent

How to find a grief support group

Men and women grieve differently, so be aware of this. Don't be too hard on your partner if he or she is not able to give you all the support you need. It is a difficult time for them too, and not everyone knows what to do, or what to say.

Read my article on Men and Grief for more understanding.

However you are feeling, know that you are not alone. Talk to friends and family. Join a grief support group , but don't be ashamed that you are grieving. It is a natural and normal process, even if it happens to everyone at some point in their lives.

There are lots more helpful articles on the site to guide you on your pathway through grief.

Related Pages:

Books on Grief for Loss of your Mother

A Sudoku Led Recovery - The Loss of my 95 Year Old Mother

Losing the Childhood Home when Mother Died

Healing from the Loss of My Mother

This page is dedicated to Stephanie and Simone who lost their beloved mother in 2012

- Grief and Sympathy Home

- Losing a Parent as an Adult

- Loss of Mother

Where to get help:

Have you considered one-on-one online grief counseling .

Get Expert and Effective Help in the Comfort of Your Own Home

The following information about online counseling is sponsored by 'Betterhelp' but all the opinions are our own. To be upfront, we do receive a commission when you sign up with 'Betterhelp', but we have total faith in their expertise and would never recommend something we didn't completely approve.

Do you feel alone and sad with no support and no idea how to move forward? It can be tough when you are stuck in grief to find the motivation to get the most out of your precious life.

Online counseling can help by giving you that support so you don't feel so alone. You can have someone to talk to anytime you like, a kind and understanding person who will help you to find meaning in life again, to treasure the memories of your loved one without being overwhelmed and to enjoy your activities, family and friends again.

- Simply fill out the online questionnaire and you will be assigned the expert grief counselor most suitable for you. It only takes a few minutes and you don't even have to use your name.

- Pay an affordable FLAT FEE FOR UNLIMITED SESSIONS.

- Contact your counselor whenever you like by chat, messaging, video or phone.

- You can change counselor at any time if you wish.

- Click here to find out more and get started immediately .

- Or read more about how online counseling works here.

Sales from our pages result in a small commission to us which helps us to continue our work supporting the grieving.

Hypnosis for Grief - 10 Ways It Can Help You

Try a gentle hypnotherapy track to relax the mind. Learn how self-hypnosis can help you cope with grief at any time of the day or night.

Read more about it here.

For Remembrance:

Sales from our pages result in a small commission to us which helps us to continue our work supporting the grieving.

Memorial Jewelry to Honour a Loved One

Check out our lovely range of memorial jewelry for any lost loved one. Pendants, necklaces, rings or bracelets, we have them all in all kinds of styles. Choose for yourself or buy as a sympathy gift.

Click here to see our selection

Create an Online Memorial Website

Honour your loved one with their own memorial website. Share photos, videos, memories and more with your family and friends in a permanent online website. Free for basic plan with no ads.

Find out more here.

Keep in touch with us:

Sign up for our newsletter and receive: "the 10 most important things you can do to survive your grief and get on with life".

Our free downloadable and printable document "The 10 Most Important Things You Can Do To Survive Your Grief And Get On With Life" will help you to be positive day to day.

The 10 points are laid out like a poem on two pretty pages which you can pin on your fridge door to help you every day!

All you have to do to receive this free document is fill in your email address below.

You will also receive our newsletter which we send out from time to time with our newest comforting and helpful information. You can unsubscribe any time you like, and don't worry, your email address is totally safe with us.

NEW BONUS - Also receive a copy of our short eBook - '99 Ways to Spot a Great Grief Counselor'. Available for instant download as soon as you sign up. Never waste money on poor counseling again!

Join us on Facebook for articles, support, discussion and more. Click 'Like' below.

Grief and Sympathy

Would you prefer to share this page with others by linking to it?

- Click on the HTML link code below.

- Copy and paste it, adding a note of your own, into your blog, a Web page, forums, a blog comment, your Facebook account, or anywhere that someone would find this page valuable.

Find us here:

Sales made via this site will result in a small commission to us which enables us to continue our work helping those who are grieving. This does not affect the price you are charged and we will only ever recommend services and products in which we have complete faith.

Expert and Effective Online Counseling - Get Started Now

Self-help hypnosis downloads.

Try gentle therapy using relaxing hypnotherapy tracks in the privacy of your own home.

Click here to find out more.

Copyright Elizabeth Postl e RN, HV, FWT and Lesley Postle - GriefandSympathy.com 2012-2024

Any information provided on this website is general in nature and is not applicable to any specific person.

For specific advice, please consult a medical practitioner or qualified psychologist or counselor.

SiteMap About Us Contact Us

Affiliate Disclosure Privacy Policy

Powered by Solo Build It

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Grieving My Mother as I Became a Mother

I’d counted on my mom, an expert on child development, to help me learn to parent my son. The thought of managing without her was terrifying.

By Cassie Chambers

This essay was originally published on January 7, 2020 in NYT Parenting.

I used to say it casually: “I feel like I’ve been hit by a truck.” I said it when I was tired, worn out, maybe coming down with a cold.

Then my mother was rear-ended by a semi truck and died. I don’t use that phrase anymore.

When the wreck happened, I was almost 19 weeks pregnant. I had talked to my mother a few hours before, like I did almost every morning. I had called her as I drove the winding road from my home to my office and complained, once again, about how tired I felt. I told her I had been feeling queasy lately. I could hear the smile in her voice. She told me she was sorry I didn’t feel well, but she was happy there were signs her grandson was growing.

She had said for months that she wanted my son to call her “Nana.” But she felt the need to reiterate it, once again, during that conversation. “I just feel like a Nana,” she said, as I pulled into the parking lot where I left my car each day. I hurriedly told her I had to go — that I was almost at my office — and she rushed out the words she always ended our calls with: “O.K., I love you, bye.” She hung up while I was saying “I love you, too.”

I tried to call her again as I came back from lunch that day. A conversation with a new mom friend had left me wondering whether I needed a doula for the birthing process. I had never heard of a doula, and I wanted my mom’s thoughts on the idea. Her phone rang until it went to voice mail.

When my father showed up at my office a few hours later with the news, I didn’t believe him. “But I talked to her just a few hours ago,” I said, confused. I didn’t fully believe that it could be true until I saw her body, days later, after it had been released by the coroner’s office. Until that point, I kept telling myself there was at least some small chance that they — the police, the hospital, the media — had made a mistake.

But it wasn’t a mistake, as surreal as it was. I began to go through the required motions: shopping for a black dress that fit over my expanding belly to wear to the funeral; picking out bright, cheerful flowers to drape over the coffin; placing the “grandmother” necklace I had bought her for Christmas a few months before into her hand so that she could be buried with it.

I walked away from the cemetery, knowing that I was beginning a journey of letting go of my mother while trying to becoming a mother myself.

I was terrified.

I felt as if all of the help and support I had counted on to be a good mother had been suddenly and unexpectedly ripped away. My mother was a baby expert, a retired director of a child development lab. She had been planning to come stay after I gave birth and to care for her grandchild once I went back to work. She had always promised me that, if and when I had kids, she would come over during the day and walk out the door as I walked in each night. “I’ll even have a casserole in the oven,” she had said, laughing. I had no experience with kids. How was I going to do this without her?

In the months before my mother’s death, I had written a book about her life. About how she had grown up in extreme poverty in the Appalachian Mountains and become the first in her family to go to college. About how she had me while she was a young college student and worked hard to graduate with me by her side. About how the value she taught me to place on education led me far beyond the eastern Kentucky hills to the halls of Harvard, Yale and the London School of Economics. I concluded that everything I knew and had was because of her, and other strong Appalachian mountain women like her.

My mother and I had always been close, but the writing process had brought us closer. We had talked for hours about her life, her memories and her unexpected life path. She traveled with me to the small mountain town she grew up in, and we spent days talking to our relatives. She was honored that her daughter wanted to write a book that told her story. A few months before she died, she read a draft and told me she felt like a “proud hill woman.” I finished the book the day before she passed.

What I missed most after she died were the conversations, both about the book and about our lives. The hours we spent on the phone sorting out the details of her memories. The chats we had over meals about family folklore. Our repeated attempts to distill some meaning from her journey. “You can tell my life story however you want,” she told me. “I just hope someone takes something from it.”

In the first months after she died, I found myself picking up my cellphone and instructing Siri to “call Mom” — before remembering that no one was going to answer on the other end. I would take the dog for a walk in the park, and instinctively begin to dial her. My book editor sent me a list of follow-up questions, and I immediately thought, “I’ll have to ask my mom about that.” Some days I felt as if the hole created by her absence would swallow me.

To fill the void, I began to write letters to her, in an attempt to continue the conversation that had been abruptly cut off. I told her about my pregnancy, about how scared I was about becoming a mother without her by my side. I asked her questions about what her labor had been like and if she thought it was O.K. to get an epidural. I recounted the mundane details of my life, because I had never not shared those with her.

“Last night was hard,” I wrote. “My friend is throwing me a baby shower and she asked me to make a registry. I didn’t know what type of baby carrier I wanted, or if a Pack ’n Play was something I needed for an infant. I wasn’t even sure what I was supposed to put (or not put) in his crib. I wanted to sit down with you and make the list together and have you explain to me why each thing was important. I can’t believe I’ll never have the chance to learn how to be a mom from you.”

It’s hard to read those letters now. The early ones are full of grief, rage and uncertainty. Sometimes, the letters were nothing more than a stream-of-consciousness scream onto a blank page. I wrote them weekly, and I didn’t necessarily feel better afterward.

Then, I had my son.

Gradually, the tone and purpose of my letters began to shift. They became a way to tell my mother about her grandchild and to hope that, somehow, the message was getting through to her. I told her how I thought my chest would burst from pride the first time he rolled over and about how his tiny fingers rested against my chest when I fed him at night. I described his coy smile and complained about what a terrible sleeper he was. I wanted to document — for her and for myself — the ways he was growing. I was growing too.

I was becoming a mother, learning how totally and completely overwhelming it was to be charged with the care of a tiny human. “When does parenting get easier?” I typed into Google one afternoon.

But I was also feeling the indescribable love and joy that comes from being a parent. “I would actually fight a tiger for him,” I told my husband in awe. I had heard other moms express that sentiment before, but I was still surprised at how intensely and sincerely I felt it.

Becoming a mother made me feel connected to my mom in a new way. I understood how much she loved me, because I loved my son that much. I could almost hear her voice during some of those late-night feeding sessions: “I did this too. You’ll get through it, just like I did.” I felt comforted, finally understanding how deep her love for me had been. Becoming a mother — the thing that scared me most after she passed — ended up being the only thing that could bring me a sense of peace.

My son is now 5 months old, and I still write letters to my mother. Not quite every week, but frequently. There is more gratitude in them now. I thank her for the lessons she taught me and the things she did for me. I understand now how much love was behind those never-ending diaper changes and 3 a.m. wake-ups. I plan to keep writing letters to her throughout my son’s childhood. It makes me feel that she — somehow, someway — is still participating in the conversation.

Cassie Chambers , a writer and lawyer who lives in Louisville, Ky., with her husband and son, is the author of “ Hill Women .”

Pregnancy, Childbirth and Postpartum Experiences

Aspirin’s Benefits: Not enough pregnant women at risk of developing pre-eclampsia, life-threatening high blood pressure, know that low-dose aspirin can help lower that risk. Leading experts are hoping to change that.

‘A Chance to Live’: Cases of trisomy 18 may rise as many states restrict abortion. Some women have chosen to have these babies , love them tenderly and care for them devotedly.

Teen Pregnancies: A large study in Canada found that women who were pregnant as teenagers were more likely to die before turning 31 .

Weight-Loss Drugs: Doctors say they are seeing more women try weight-loss medications in the hopes of having a healthy pregnancy. But little is known about the impact of those drugs on a fetus.

Premature Births: After years of steady decline, premature births rose sharply in the United States between 2014 and 2022. Experts said the shift might be partly the result of a growing prevalence of health complications among mothers .

Depression and Suicide: Women who experience depression during pregnancy or in the year after giving birth have a greater risk of suicide and attempted suicide .

Death, Dying, and Bereavement: Reflection Essay

Terminal illness, end of life issue.

While dying is part of human life that surrounds each person, some encounters with death are more influential than others. My mother’s passing was an experience that impacted my view of life and end of life care the most. She died before her 60th birthday – her terminal illness was discovered very late, and she passed away less than a year after receiving the diagnosis. Such a rapid change in my life left a mark on my memory and reshaped my view of life and death.

It was difficult for me to come to terms with her death – the period between the diagnosis and her passing was too short. I was in denial for a long time and had trouble accepting what had happened. Looking back at this time, I see how the end of life is not always expected, and why the children of terminally ill loved ones require the attention of medical professionals as well.

End of life care for my mother took a toll on me, and I had to reevaluate my aspirations to see whether I treated life as an endless path. Now, I reflect on the feelings I had in order to remind myself that the end of life cannot be fully preplanned and that each case is unique in its own way. Moreover, I try to remember that one’s existence is finite. In some cases, the best solution is to provide as much comfort to someone and make sure they are making choices to the best of their ability and knowledge to have a happy and dignified time.

I also considered how my mother might have felt at the moment of diagnosis and during her last year. It is incredibly challenging for one to understand what knowing that you will die soon means. Such clarity is not always desired, but I believe that it is vital for people to know about their current condition because it affects their decision-making in healthcare and life, in general. Death is a part of each human’s life, but every step toward it does not feel final because it can come at any moment.

Knowing one’s diagnosis changes the way people and their loved ones think. Although I can only imagine what my mother felt, I understand what the families of terminally ill persons are going through.

If I were diagnosed with a terminal illness and were given a prognosis of six months or less to live, I would try to accept it in good faith before making decisions. Death is inevitable, but it is impossible to be fully prepared for it, even when you think that you are. So, I would look into myself to search for peace with this news in order to take advantage of the time that I have left.

I would feel sad because I would not see my loved ones and miss them dearly. Thus, my priorities for what should be done would change. I would try to see my family and friends as much as I could and spend time with them, making memories for them and myself. I would like to leave some mementoes behind and focus on the good times that we would have together. Planning for several months ahead is difficult when the exact date of death is unknown, so I would do my best to make the most of each day.

However, it is also vital to think about one’s inner comfort and peace. Coming to terms with my passing would be critical to me – it provides some type of closure and allows me to let go of worries related to everyday life. People may cover their fear of dying with activities and concentration on planning and socialization. In doing so, they may overlook their own satisfaction with life, denying themselves a chance to reflect. As such, I would spend some time searching for some last unanswered questions and unachieved goals that could be completed in the short span of time that I would have.

Finally, I would concentrate on my present and my loved ones’ future. I always strive to remember that life is endless in a way that it continues for other people. Although I will eventually die, some of my friends and my family members will continue living long after I am gone, facing problems and challenges that are inherent to humanity.

Thus, I would try to make plans to alleviate some of these issues. Most importantly, I would organize the provision for my child to finance the education – one of the most necessary, but expensive, parts of one’s coming to adulthood. If possible, I would review our housing options, savings, family and friends support network, and address other household and healthcare concerns.