BibleProject Guides

Guide to the Book of Exodus

Key Information and Helpful Resources

Exodus is the second book of the Bible, and it picks up the biblical storyline right where Genesis left off. Abraham’s grandson Jacob and his family of seventy made their way down to Egypt, where Joseph, one of Jacob’s sons, had been elevated to second in command over Egypt. So the family lived and grew in Egypt as a safe haven for many years.

After a few hundred years, the story of Exodus begins.The word “exodus” refers to the major event that takes place in the first half of the book, Israel’s exodus from Egypt. The book also has a second half that takes place at the foot of Mount Sinai. For now, we will focus on the first half, in which centuries have passed and the Israelites “were fruitful and multiplied and filled the land” (Exod. 1:7).

This phrase is a deliberate echo of the blessing God gave humanity back in the garden (Gen. 1:28), which reminds us of the bigger story so far. When humanity forfeited God’s blessing through sin and rebellion, God’s response was to choose Abraham’s family as the vehicle through which he would restore his blessing to the world.

Exodus 1-18

6:33 • Old Testament Overviews

Who Wrote the Book of Exodus?

Many Jewish and Christian traditions hold that Moses is the author of Exodus. However, authorship is not explicitly stated within the book.

The events described in Exodus take place in Egypt and on the Sinai Peninsula, starting before Moses’ birth until Israel’s arrival at Mount Sinai.

Literary Styles

Exodus is written as narrative and contains occasional poetic and discourse sections.

- God’s confrontation with evil brings justice and rescue

- God’s desire and plan to dwell among his people

- God’s faithfulness to his promises and commitment to an often faithless people

- Sin and idolatry as the greatest threats to the covenant promises and blessings

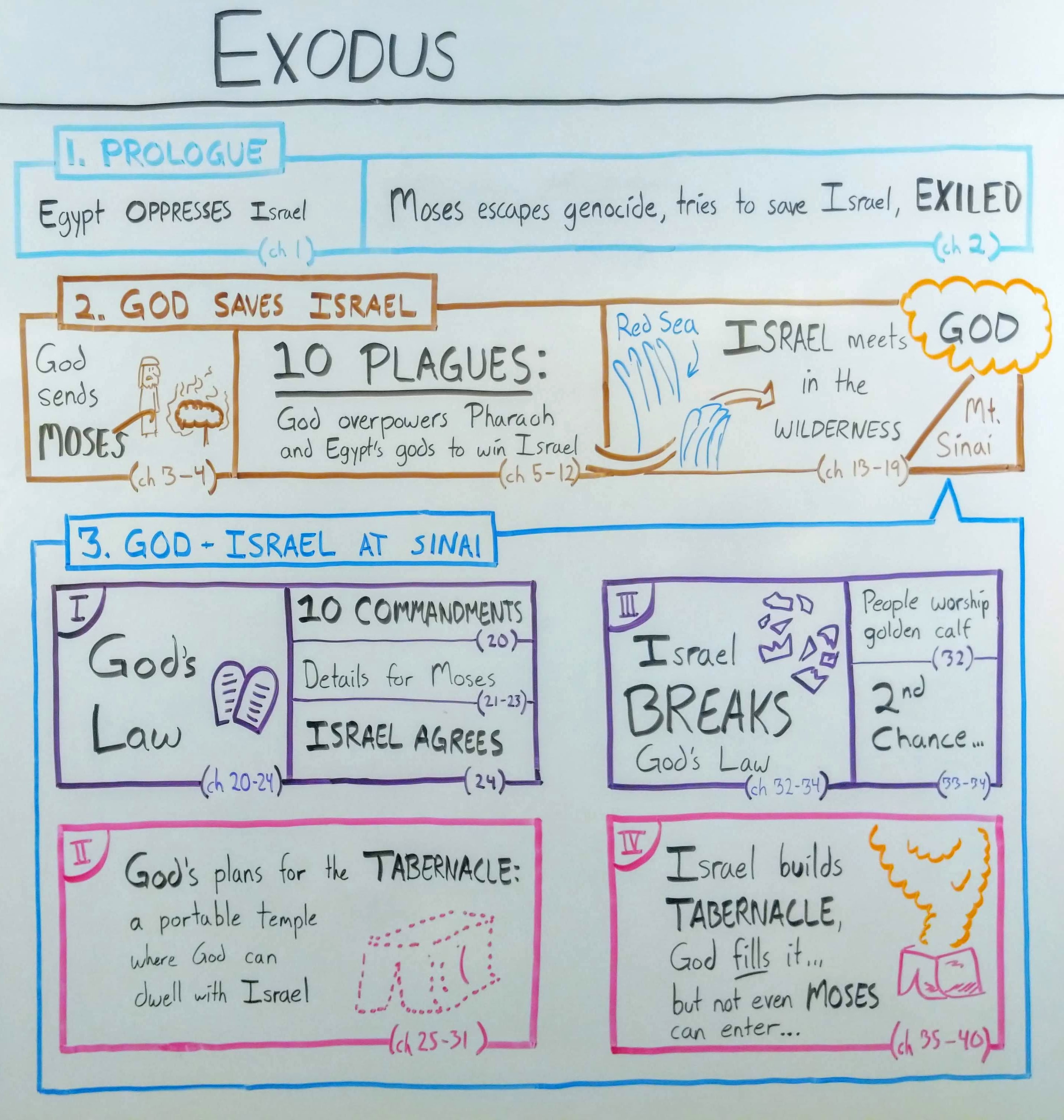

The structure of Exodus is divided into five parts. Chapters 1-15 detail Israel’s slavery in Egypt, God confronting Pharaoh through Moses, and Israel’s deliverance. Chapters 16-40 outline Israel’s grumbling, rebellion, and covenant at Sinai.

Exodus 1-4: Israel’s Enslavement Under Pharaoh

The new Pharaoh, however, does not see Israel as a blessing. He thinks this growing Israelite immigrant group is a threat to his power. So, just as in Genesis, humanity rebels against God. Pharaoh attempts to destroy the Israelites by brutally enslaving them and using them in hard physical labor. It’s bad, but it gets worse when he orders that all Israelite boys be drowned in the Nile River.

This Pharaoh is the worst character in the Bible so far, and his kingdom epitomizes humanity’s rebellion against God. Pharaoh has so redefined good and evil according to his own interests that murder of innocent children becomes “good.” Egypt has become worse than Babylon, and Israel cries out for help against this new form of evil. God responds by first turning Pharaoh’s evil plot upside-down. An Israelite mother throws her boy into the Nile, protected inside a basket, and the child floats right into the Pharaoh’s own family. This boy is named Moses, and he eventually grows up to become the man God will use to defeat Pharaoh.

In the famous story of the burning bush, God appears to Moses and commissions him to go to Pharaoh and order him to release the Israelites. God says that he knows Pharaoh will resist. But God plans to bring his justice down upon Egypt in the form of plagues and harden Pharaoh’s heart.

Related Content

Exodus Overview

Podcast Episode

“God” Is Not a Name

Exodus 5-15: The Ten Plagues and Pharaoh’s Hardening Heart

The confrontation between God and Pharaoh is the major focus in this narrative, but what does it mean that God will harden his heart? It is important to read this part of the story closely and in sequence. In Moses and Pharaoh’s first encounter, we are told simply that Pharaoh’s heart “grew hard,” without any implication that God caused it.

God proceeds to send the first set of five plagues, each one confronting Pharaoh and his gods. Each time, Moses offers a chance for Pharaoh to humble himself and let the people go. However, after each plague, we are told that Pharaoh either “hardened his heart,” or that his “heart grew hard.” He’s doing this of his own will. It’s only with the second set of five plagues that we begin to hear that God hardened Pharaoh’s heart .

The point is that even though God knew Pharaoh would resist his will, God still offered him many chances to do the right thing. Eventually Pharaoh’s evil reaches a point of no return, and even his advisors think he has lost his mind. It’s at that point that God takes over and bends Pharaoh’s evil to his own redemptive purposes. He lures Pharaoh into his own destruction and saves his people.

With the final plague, the night of Passover, God turns the tables on Pharaoh. Just as Pharaoh killed the sons of the Israelites, so God will kill the firstborn sons of Egypt. Unlike Pharaoh, however, God will provide a means of escape through the blood of a lamb.

Here the story stops and introduces us to the annual Israelite ritual of Passover (Exod. 12-13). On the night before Israel left Egypt, they sacrificed a young, spotless lamb and painted its blood on the doorframe of their house. When the divine plague came over Egypt, the houses covered with the blood of the lamb would be “passed over” and the sons spared. Every year since, the Israelites have reenacted this night to remember and celebrate God’s justice and mercy.

Because of his pride and rebellion, Pharaoh loses his son and is compelled to finally let the Israelites go free. The Israelite slaves make their escape from Egypt, but as soon as they leave, Pharaoh changes his mind. He gathers his army and chases after them for a final showdown, thinking that he will slaughter them by the waters of the sea. However, the Israelites run into the sea and discover they’re walking on dry ground that God has provided. But when Pharaoh pursues them, the waters surge around him, destroying him.

This part of the book of Exodus concludes with the first song of praise in the Bible, called “The Song of the Sea” (Exod. 15). The final line declares that “the Lord reigns as king,” and the song retells in poetry what the God’s Kingdom is all about. God is on a mission to confront evil in his world, redeem those enslaved to evil, and bring them to the promised land where his divine presence will live among them. This is what it looks like when God becomes King over his people.

If God Hardened Pharaoh's Heart, Did God Cause the Evil?

Pharaoh vs. the Warrior God

Moses and Aaron

Exodus 16-18: Grumbling in the Wilderness

After the people sing their song, the story takes a surprising turn. The Israelites trek through the wilderness on their way to Mount Sinai and get really hungry and thirsty. In their distress, they start criticizing Moses and God for rescuing them from Egypt! Even though God graciously provides food and water for his people, these events cast a dark shadow. As readers, we wonder if it is possible that Israel’s heart is as hard as Pharaoh’s. We’re left with that haunting question as we turn to read about Israel’s experience at Mount Sinai.

Generosity Q+R: Overpopulation, Cain's Sacrifice, and Manna Hoarding

Israel Tests Yahweh

Exodus 19-31: The Covenant at Sinai

The second half of the book of Exodus picks up right as Moses leads Israel to the foot of Mount Sinai (Exod. 19), where God invites the nation to enter into a covenant relationship. It’s here that we reach another key moment in the big storyline of the Bible. This moment develops God’s promise to Abraham—that through him and his family God would restore his blessing to all nations (Gen. 12, 15, 17). God says that if the people of Israel obey the terms of the covenant, they will become a “kingdom of priests” (Exod. 19:6), acting as God’s representatives to the nations and showing them his character by how they live. In this way, God’s justice and mercy will reach the nations.

The people eagerly accept the offer, and God’s presence appears on the mountain in the form of a cloud. Moses goes up as the people’s representative, and God opens with the basic terms of the covenant, the famous Ten Commandments. These are foundational rules that set up how the Israelites relate to God and to each other. After this comes a collection of fifty-two more commands, which expand on the first ten with more detail. There are laws about Israel’s worship and social justice, which shape how Israel was to live differently from the other nations. Moses wrote down all these laws and brought them to the people, who eagerly agreed to the terms of the covenant.

God then takes the relationship forward another step. He tells Moses that he wants his holy and divine presence to dwell in the midst of Israel. This develops another aspect of God’s original covenant promise from the book of Genesis. After humanity’s rebellion in the garden, access to God’s presence was lost. However, through the family of Abraham, God’s presence has become accessible again, first to Israel at Mount Sinai and one day to all nations.

The following seven chapters (Exod. 25-31) detail the architectural blueprints of a sacred tent called the tabernacle. There is an outer courtyard with an altar, an outer and inner room in the center of the tent, and inside the inner room—called the most holy space—is a golden box with angelic creatures on it, the ark of the covenant. This ark acts as a “hotspot” for God’s presence.

There’s a lot of detail in these chapters, but it’s important to know that every part has a symbolic value. All of the flowers, angels, gold, and jewels call back to the garden of Eden, the place where God and humans lived together in intimacy. In other words, the tabernacle is a portable Eden where God and Israel can live together in peace. That’s how it could have worked, in theory, but things go off course, and Israel breaks the covenant.

Exodus 19-40

The Covenants

The Cathedral in Time

Exodus 32-40: Israel’s Wilderness Rebellion

While Moses is up on the mountain receiving the blueprints for the tabernacle, the Israelites are losing patience down in the camp. They ask Moses’ brother Aaron to make a golden calf idol so they can worship it as the god who saved them from slavery in Egypt. Even as God’s presence is hovering atop the mountain, they are already breaking the first two commandments of the covenant: no idols and no other gods.

What follows is crucial to the rest of the biblical story and how we understand God’s character. God first invites Moses into his anger and pain, venting his feelings and saying he wants to wipe out the entire nation of Israel. After listening, Moses intercedes by appealing to God’s character, saying that this would mean going back on his covenant promises to Abraham. Moses also appeals to God’s reputation among the nations. What would the Egyptians think if he allowed Israel to die in the wilderness? God accepts Moses’ prayer and relents. And while God does bring justice to those who instigated the idolatry, he forgives the nation as a whole and renews the covenant. It’s at this point God describes himself to Moses. “The Lord is merciful and gracious, slow to anger, abounding in covenant faithfulness. He forgives sin, but will not leave the wicked unpunished” (Exod. 34:6-7). In other words, God is full of mercy, but he must deal with evil if he claims to be good. Above all else, God is faithful to his promises even if it means committing himself to people who are faithless.

After renewing the covenant, God commissions Moses to build the tabernacle, detailed in the next five chapters (Exod. 35-39). It all comes together in the final chapter (Exod. 40). The tabernacle is finished, and God’s glorious presence comes over the tent. Our hopes are high! But as Moses goes to enter the tent, he finds that he is unable to. He is blocked from entering, and the book of Exodus comes to a sudden end.

We see now that Israel’s sin has damaged their relationship with God in more ways than we had realized. The book may have opened with Pharaoh’s evil threatening Israel, but as the book comes to an end, Israel has become their own worst enemy. The sin and idolatry of God’s own people is now the greatest threat to his covenant promises. How is God going to reconcile the conflict between his holy, good presence with the sin and corruption of his own people? That’s the question that the next book, Leviticus, sets out to answer.

Visual Commentary: Exodus 34:6-7

Slow to Anger

The Most Quoted Verse in the Bible

Why Moses Couldn’t Enter the Tabernacle

God rescues the people of Israel from Egypt and invites them into an agreement, or covenant, with him. The people damage their relationship with God, which causes God to recommit to his promise to dwell with them.

How to Read Exodus

Exodus (The NIV Application Commentary)

Exploring Exodus: The Origins of Biblical Israel

Exodus (Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries)

Exodus Overview Poster

Scripture Reference Guide

Exodus 1-18 Script References

Exodus 19-40 Script References

Exodus: God saves His people from Egypt

by Jeffrey Kranz | Nov 17, 2018 | Bible Books | 27 comments

The book of Exodus is the story of God rescuing the children of Israel from Egypt and forging a special relationship with them. Exodus is the second book of the Pentateuch (the five books of Moses ), and it’s where we find the stories of the Ten Plagues, the first Passover, the parting of the Red Sea, and the Ten Commandments.

The book gets its name from the nation of Israel’s mass emigration from Egypt, but that’s only the first part of the story. This book follows Israel out of Egypt into the desert, where the nation is specifically aligned with God (as opposed to the idols of Egypt and the surrounding nations). This is the book in which God first lays out his expectations for the people of Israel—we know these expectations as the 10 Commandments. Most of the Old Testament is about how Israel meets (or fails to meet) these expectations. So if you want to understand any other book of the Old Testament, you’ll need a basic understanding of what happens in Exodus.

Important characters in Exodus

Exodus has a tight cast of important characters to keep an eye on.

God (Yahweh) —the creator of heaven and earth and the divine being who chooses the nation of Israel to represent him on earth. God goes to war against the gods of Egypt, frees Israel from their tyranny, and then makes a pact with the new nation. While the rest of the nations serve lesser gods, Yahweh selects the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as the people group that will serve him and him alone.

Moses —the greatest of the Old Testament prophets who serves as a go-between for God and the other humans in the book of Exodus. Moses negotiates with Pharaoh for Israel’s freedom, passes God’s laws on to the people of Israel, and even pleads for mercy on Israel’s behalf when they anger God.

Aaron —Moses’ brother and right hand. Aaron assists Moses as a spokesperson, and eventually is made the high priest of the nation of Israel.

Pharaoh —the chief antagonist in the Exodus story. Pharaoh enslaves the nation of Israel, commits genocide, and is generally a huge jerk.Pharaoh is worshiped as part of the Egyptian pantheon: a lesser god laying an illegitimate claim to God’s people. God defeats Pharaoh and the gods of Egypt by sending a series of ten devastating plagues, and finally destroying Pharaoh’s army in the Red Sea.

Key themes in Exodus

Exodus is all about God making Israel his own. God rescues the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (whom he made some important promises to back in Genesis ). Then, he gives them his expectations—a list of dos and don’ts. Finally, God sets up camp in the midst of the new nation: they are his people, and he is their God.

When God gives Israel the Ten Commandments, he frames them by stating his relationship to the Hebrews. This verse sums up the themes of Exodus nicely:

“I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.” (Ex 20:2)

(You can find more Bible verse art here .)

Let’s take a quick spin through some of Exodus’ themes.

It’s hard to miss this one! The entire book is about God hearing Israel’s cries for help, rescuing them from their oppressors, and making them his own.

Like the rest of the Torah, covenant is a big theme here. God makes a solemn, binding agreement with the people of Israel, establishing himself as their god and them as his people. This relationship comes with certain expectations, with benefits for the Israelites if they uphold their end of the agreement, and consequences if they do not.

God’s presence

Toward the beginning of the book, the cries of Israel rise up to God, who hears them and remembers his promises to Abraham back in Genesis. In the middle of the book, God meets Israel in the wilderness: he is high atop a mountain, and they are on the plain below. God is closer to the people, but still a ways off. However, by the end of the book, God is dwelling in the middle of Israel’s camp in the wilderness. Moses believes that it is God’s presence among the people that sets Israel apart from every other nation in the world (Exod 33:16).

This is related to the theme of covenant—specifically, the expectations God has for the people of Israel. From chapter 20 onward, we start seeing more and more directives for the people on how to live as the people of God.

Zooming out: Exodus in context

Exodus is where the story of the Bible really starts picking up. God has already made his promises to Abraham: his descendants would be a mighty people, they would possess the land of Canaan, and through them the whole earth will be blessed by God. While in Genesis we see God working through a family, in Exodus we see God working with an entire nation.

Exodus is a starburst of Old and New Testament theology. God is faithful, and keeps His promise to Abraham (Gn 15:13–21) by judging the Egyptians and liberating Israel. The Lord also gives Israel the first iteration of the Law, and begins to dwell among His people in the tabernacle. God’s liberation of Israel from slavery foreshadows His work to redeem the nations (Ro 6:17–18), just as His judgment on His people serves as an example for Christians now (1 Co 10:6–13). Exodus is also where God reveals His memorial name: YHWH, or LORD (Ex 3:14; 6:3).

An overview of Exodus’ story and structure

Act 1: Prologue

(Exodus 1–2)

Exodus picks up where Genesis leaves off: the young nation of Israel is in Egypt (they were invited by Joseph, the one with the famous coat). A new Pharaoh notices the Israelites multiplying, and enslaves them. Afraid of an uprising, he orders that all Hebrew sons should be cast into the Nile at birth.

But one baby boy escapes this fate: the Hebrew Moses grows up in Pharaoh’s household. When adult Moses kills an abusive Egyptian slave driver, he flees the country.

Act 2: God saves Israel

(Exodus 3–19)

Forty years later, God appears to Moses as a burning bush and sends him to deliver Israel from the hand of Pharaoh.

Moses, with the help of his brother Aaron, confronts Pharaoh on God’s behalf: “Let My people go” (Ex 5:1). Pharaoh refuses, and so God sends those famous 10 plagues upon the Egyptians. When the last plague kills Pharaoh’s son, he finally allows Israel to leave.

The Israelites celebrate the first-ever Passover, and then set out into the wilderness. Pharaoh changes his mind and sends his army to recapture them. God saves Israel miraculously by parting the Red Sea and allowing Israel to escape their would-be captors—and then uses the sea to wash away Pharaoh’s army. The Israelites leave Egypt and make their way to the foot of Mount Sinai in the wilderness. God descends on the top of the mountain, and then, something amazing happens.

Act 3: God makes a covenant with Israel

(Exodus 20–40)

The Israelites leave Egypt and make their way to Mount Sinai, where God gives His laws to Moses. God makes a covenant with the nation of Israel and the generations to come: because He rescued them from Egypt, Israel is to observe His rules. God speaks the Ten Commandments directly to the whole nation of Israel, and He relays specific ordinances to Moses on the mountain. And the people agree to it!

After this, God makes plans for a place of worship. He’s going to come down from the mountaintop and dwell in the midst of the people of Israel—but in order for this to happen, the people need to prepare a portable tabernacle for him. God gives Moses the plans for the tabernacle, the sacred furniture, and the garments for the priests.

But already things aren’t going as planned. While God is giving Moses laws for the people, the people start worshiping a golden calf … not cool. Moses pleads with God on Israel’s behalf, and the nation is given another go at keeping God’s commands.

And so Israel builds the tabernacle: a holy tent. The book of Exodus ends with the glory of the LORD filling the tabernacle. God is now dwelling among His chosen people, Israel. However, now there’s another problem: how will the people live in the presence of such a holy and powerful being?

That’s what the next book, Leviticus is all about.

Who wrote Exodus?

More pages related to Exodus

- Leviticus (next book of the Bible)

- Genesis (previous)

- Deuteronomy

- The Pentateuch

27 Comments

These are fantastic! Is there a downloadable version?

Thanks, Steven! We don’t have any poster/PDF versions of these yet, I’m afraid—but perhaps someday soon!

I am so delighted in reading your summary on the Books of the Bible! I have began to read the bible from the beginning again and this time and I am truly enjoying it and learning so much and your comments even make it much more clearer.

Many Blessings, Joye

You have made my bible study more understandable and clear. Love your work!!

Hi Jeffery I have started reading the entire Bible chronologically and these overviews are tremendous blessings. Thanks for all the preparation and hard work you do for His Kingdom. Praying for you and this crucial ministry God has given you. Blessings Maryse

I want to see this kind of information about the book of Genesis as well. Please send me. Tq.

Check out our page on Genesis !

This work you have undertaken is just excellent. I am thoroughly enjoying reading, and learning more and more as I go. Outstanding job; you are truly spreading His word. Thank you. :)

Thanks for the kind words, Daniel!

Clear and very good presentation on the Exodus. Thank you very much, Jeffrey. What a blessing!

Thanks so much for the kind words! =)

Very good teaching with great research and explanation

Thanks, John! =)

Thanks Jeffery ! Your video and the overview help me to plan and organize my bible study for kids well ! =)

-from Seoul

Super kind of you to let me know how helpful this is, Mira. Thank you!

God blessed you with the talent to both draw and compose sketches. It lays a foundation for me to draw in the details and colors to make it mine. Thanks!

What a kind note—thank you! We’ve considered making a Bible outline coloring book … would that be something you’d find useful?

These videos are awesome! Thank you! The Bible can be overwhelming and confusing, but these videos clear up the big picture as I walk through the Bible verse by verse throughout the year.

I am using your fantastic explanations and began sharing your videos as the focus at my men’s ministry – Brick Breakers. They are a blessing. Thank you, Scott

Glad to hear they’re useful, Scott—thanks for the kind words!

Thank you Jeffery. I appreciate your work.

God bless, Pastor Bill.

I have enjoyed your survey work of the O.T. books. Are we allowed to print them? If so is there a format for that?

Thank you and God bless.

Thanks, Bill! I don’t have print-friendly formats for all these, but you’re welcome to print out these book surveys all the same. =)

Oh my..those breakdowns added immensely to my study of the Word. I appreciate to effort that took . I just signed on for more….

Thanks, Annette—glad they’re helpful. =)

I would like an overview of each book in old testament . Thanks

Lula, you can find them all here . Enjoy!

- Bible Books

- Bible characters

- Bible facts

- Bible materials

- Bible topics

Recent Posts

- Interesting Facts about the Bible

- Logos Bible Software 10 review: Do you REALLY need it?

- Who Was Herod? Wait… There Were How Many Herods?!

- 16 Facts About King David

- Moses: The Old Testament’s Greatest Prophet

Privacy Overview

Book of Exodus NIV

Chapters for exodus, summary of the book of exodus.

This summary of the book of Exodus provides information about the title, author(s), date of writing, chronology, theme, theology, outline, a brief overview, and the chapters of the Book of Exodus.

"Exodus" is a Latin word derived from Greek Exodos, the name given to the book by those who translated it into Greek. The word means "exit," "departure" (see Lk 9:31 ; Heb 11:22 ). The name was retained by the Latin Vulgate, by the Jewish author Philo (a contemporary of Christ) and by the Syriac version. In Hebrew the book is named after its first two words, we'elleh shemoth ("These are the names of"). The same phrase occurs in Ge 46:8 , where it likewise introduces a list of the names of those Israelites "who went to Egypt with Jacob" ( 1:1 ). Thus Exodus was not intended to exist separately, but was thought of as a continuation of a narrative that began in Genesis and was completed in Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The first five books of the Bible are together known as the Pentateuch (see Introduction to Genesis: Author and Date of Writing).

Author and Date of Writing

Several statements in Exodus indicate that Moses wrote certain sections of the book (see 17:14 ; 24:4 ; 34:27 ). In addition, Jos 8:31 refers to the command of Ex 20:25 as having been "written in the Book of the Law of Moses." The NT also claims Mosaic authorship for various passages in Exodus (see, e.g., Mk 7:10 ; 12:26 and NIV text notes; see also Lk 2:22-23 ). Taken together, these references strongly suggest that Moses was largely responsible for writing the book of Exodus -- a traditional view not convincingly challenged by the commonly held notion that the Pentateuch as a whole contains four underlying sources (see Introduction to Genesis: Author and Date of Writing).

According to 1Ki 6:1 (see note there), the exodus took place 480 years before "the fourth year of Solomon's reign over Israel." Since that year was c. 966 b.c., it has been traditionally held that the exodus occurred c. 1446. The "three hundred years" of Jdg 11:26 fits comfortably within this time span (see Introduction to Judges: Background). In addition, although Egyptian chronology relating to the 18th dynasty remains somewhat uncertain, some recent research tends to support the traditional view that two of this dynasty's pharaohs, Thutmose III and his son Amunhotep II, were the pharaohs of the oppression and the exodus respectively (see notes on 2:15,23 ; 3:10 ).

On the other hand, the appearance of the name Rameses in 1:11 has led many to the conclusion that the 19th-dynasty pharaoh Seti I and his son Rameses II were the pharaohs of the oppression and the exodus respectively. Furthermore, archaeological evidence of the destruction of numerous Canaanite cities in the 13th century b.c. has been interpreted as proof that Joshua's troops invaded the promised land in that century. These and similar lines of argument lead to a date for the exodus of c. 1290 (see Introduction to Joshua: Historical Setting).

The identity of the cities' attackers, however, cannot be positively ascertained. The raids may have been initiated by later Israelite armies, or by Philistines or other outsiders. In addition, the archaeological evidence itself has become increasingly ambiguous, and recent evaluations have tended to redate some of it to the 18th dynasty. Also, the name Rameses in 1:11 could very well be the result of an editorial updating by someone who lived centuries after Moses -- a procedure that probably accounts for the appearance of the same word in Ge 47:11 (see note there).

In short, there are no compelling reasons to modify in any substantial way the traditional 1446 b.c. date for the exodus of the Israelites from Egyptian bondage.

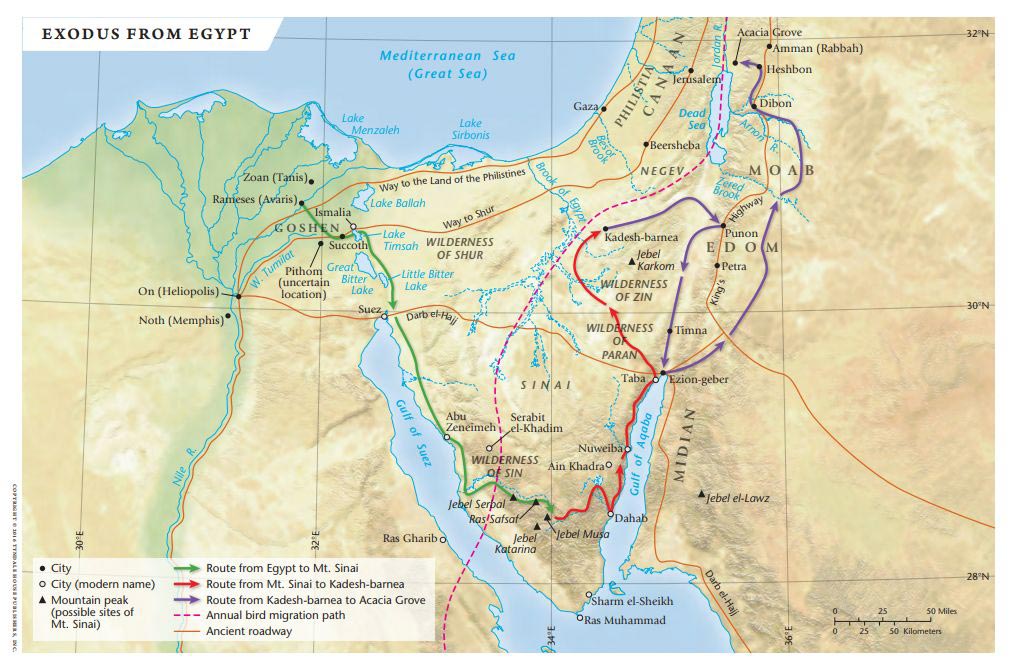

The Route of the Exodus

At least three routes of escape from Pithom and Rameses ( 1:11 ) have been proposed: (1) a northern route through the land of the Philistines (but see 13:17 ); (2) a middle route leading eastward across Sinai to Beersheba; and (3) a southern route along the west coast of Sinai to the southeastern extremities of the peninsula. The southern route seems most likely, since several of the sites in Israel's desert itinerary have been tentatively identified along it. See map No. 2 at the end of the Study Bible. The exact place where Israel crossed the "Red Sea" is uncertain, however (see notes on 13:18 ; 14:2 ).

Themes and Theology

Exodus lays a foundational theology in which God reveals his name, his attributes, his redemption, his law and how he is to be worshiped. It also reports the appointment and work of Moses as the mediator of the Sinaitic covenant, describes the beginnings of the priesthood in Israel, defines the role of the prophet and relates how the ancient covenant relationship between God and his people (see note on Ge 17:2 ) came under a new administration (the covenant given at Mount Sinai).

Profound insights into the nature of God are found in chs. 3 ; 6 ; 33-34 . The focus of these texts is on the fact and importance of his presence with his people (as signified by his name Yahweh -- see notes on 3:14-15 -- and by his glory among them). But emphasis is also placed on his attributes of justice, truthfulness, mercy, faithfulness and holiness. Thus to know God's "name" is to know him and to know his character (see 3:13-15 ; 6:3 ).

God is also the Lord of history. Neither the affliction of Israel nor the plagues in Egypt were outside his control. The pharaoh, the Egyptians and all Israel saw the power of God. There was no one like him, "majestic in holiness, awesome in glory, working wonders" ( 15:11 ; see note there).

It is reassuring to know that God remembers and is concerned about his people (see 2:24 ). What he had promised centuries earlier to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob he now begins to bring to fruition as Israel is freed from Egyptian bondage and sets out for the land of promise. The covenant at Sinai is but another step in God's fulfillment of his promise to the patriarchs ( 3:15-17 ; 6:2-8 ; 19:3-8 ).

The Biblical message of salvation is likewise powerfully set forth in this book. The verb "redeem" is used, e.g., in 6:6 ; 15:13 . But the heart of redemption theology is best seen in the Passover narrative of ch. 12 , the sealing of the covenant in ch. 24 , and the account of God's gracious renewal of that covenant after Israel's blatant unfaithfulness to it in their worship of the golden calf (see 34:1-14 and notes). The apostle Paul viewed the death of the Passover lamb as fulfilled in Christ ( 1Co 5:7 ). Indeed, John the Baptist called Jesus the "Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world" ( Jn 1:29 ).

The foundation of Biblical ethics and morality is laid out first in the gracious character of God as revealed in the exodus itself and then in the Ten Commandments ( 20:1-17 ) and the ordinances of the Book of the Covenant ( 20:22 -- 23:33 ), which taught Israel how to apply in a practical way the principles of the commandments.

The book concludes with an elaborate discussion of the theology of worship. Though costly in time, effort and monetary value, the tabernacle, in meaning and function, points to the "chief end of man," namely, "to glorify God and to enjoy him forever" (Westminster Shorter Catechism). By means of the tabernacle, the omnipotent, unchanging and transcendent God of the universe came to "dwell" or "tabernacle" with his people, thereby revealing his gracious nearness as well. God is not only mighty in Israel's behalf; he is also present in the nation's midst.

However, these theological elements do not merely sit side by side in the Exodus narrative. They receive their fullest and richest significance from the fact that they are embedded in the account of God's raising up his servant Moses (1) to liberate his people from Egyptian bondage, (2) to inaugurate his earthly kingdom among them by bringing them into a special national covenant with him, and (3) to erect within Israel God's royal tent. And this account of redemption from bondage leading to consecration in covenant and the pitching of God's royal tent in the earth, all through the ministry of a chosen mediator, discloses God's purpose in history -- the purpose he would fulfill through Israel, and ultimately through Jesus Christ the supreme Mediator.

- Israel Blessed and Oppressed ( ch. 1 )

- Infant Moses spared ( 2:1-10 )

- Mature Moses' escape from Egypt ( 2:11-25 )

- The Deliverer Called ( ch. 3 )

- The Deliverer's Objections and Disqualifications Overcome ( ch. 4 )

- Oppression made more harsh ( 5:1-21 )

- Promise of deliverance renewed ( 5:22 ; 6:12 )

- The Deliverers Identified ( 6:13-27 )

- Deliverer's commission renewed ( 6:28 ; 7:7 )

- Presenting the signs of divine authority ( 7:8-13 )

- First plague: water turned to blood ( 7:14-24 )

- Second plague: frogs ( 7:25 ; 8:15 )

- Third plague: gnats ( 8:16-19 )

- Fourth plague: flies ( 8:20-32 )

- Fifth plague: against livestock ( 9:1-7 )

- Sixth plague: boils ( 9:8-12 )

- Seventh plague: hail ( 9:13-35 )

- Eighth plague: locusts ( 10:1-20 )

- Ninth plague: darkness ( 10:21-29 )

- Tenth plague announced: death of the firstborn ( ch. 11 )

- The Passover ( 12:1-28 )

- The Exodus from Egypt ( 12:29-51 )

- The Consecration of the Firstborn ( 13:1-16 )

- Deliverance at the "Red Sea" ( 13:17 ; 14:31 )

- Song at the sea ( 15:1-21 )

- The waters of Marah ( 15:22-27 )

- The manna and the quail ( ch. 16 )

- The waters of Meribah ( 17:1-7 )

- The war with Amalek ( 17:8-16 )

- Basic administrative structure ( ch. 18 )

- The Covenant Proposed ( ch. 19 )

- The Decalogue ( 20:1-17 )

- The Reaction of the People to God's Fiery Presence ( 20:18-21 )

- Prologue ( 20:22-26 )

- Laws on slaves ( 21:1-11 )

- Laws on homicide ( 21:12-17 )

- Laws on bodily injuries ( 21:18-32 )

- Laws on property damage ( 21:33 ; 22:15 )

- Laws on society ( 22:16-31 )

- Laws on justice and neighborliness ( 23:1-9 )

- Laws on sacred seasons ( 23:10-19 )

- Epilogue ( 23:20-33 )

- Ratification of the Covenant ( ch. 24 )

- Collection of the materials ( 25:1-9 )

- Ark and atonement cover ( 25:10-22 )

- Table of the bread of the Presence ( 25:23-30 )

- Gold lampstand ( 25:31-40 )

- Curtains and frames ( ch. 26 )

- Altar of burnt offering ( 27:1-8 )

- Courtyard ( 27:9-19 )

- Priesthood ( 27:20 ; 28:5 )

- Garments of the priests ( 28:6-43 )

- Ordination of the priests ( ch. 29 )

- Altar of incense ( 30:1-10 )

- Census tax ( 30:11-16 )

- Bronze basin ( 30:17-21 )

- Anointing oil and incense ( 30:22-38 )

- Appointment of craftsmen ( 31:1-11 )

- Observance of Sabbath rest ( 31:12-18 )

- The golden calf ( 32:1-29 )

- Moses' mediation ( 32:30-35 )

- Threatened separation and Moses' prayer ( ch. 33 )

- Renewal of the covenant ( ch. 34 )

- Summons to build ( 35:1-19 )

- Voluntary gifts ( 35:20-29 )

- Bezalel and his craftsmen ( 35:30 ; 36:7 )

- Progress of the work ( 36:8 ; 39:31 )

- Moses' blessing ( 39:32-43 )

- Erection of God's royal tent ( 40:1-33 )

- Dedication of God's royal tent ( 40:34-38 )

From the NIV Study Bible, Introductions to the Books of the Bible, Exodus Copyright 2002 © Zondervan. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Exodus Videos

How Do We See Christ in the Old Testament?

Why Is a 1446 BC Date for the Exodus So Significant?

What is the Central Theme of the Torah?

What Is the Pentateuch?

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Book of Exodus

Introduction.

- The Masoretic Hebrew Version

- The Samaritan Hebrew Version

- The Greek Septuagint Version

- English Translations

- Annotated Study Bibles

- Dictionary Treatments

- Old Testament Introductions

- Research Tools

- Bibliographies and Surveys of Scholarship

- Technical Commentaries

- Commentaries for General Readers

- Collected Essays

- History of Composition and Literary Context

- Exodus and History

- Exodus and Israelite Religion

- Exodus and Moses

- Feminist Interpretations

- History of Tradition and Composition

- Conflict at the Sea

- Hymns of the Exodus

- Exodus and Wilderness Journey (Exodus 16–18)

- Exodus and Revelation at Mount Sinai (Exodus 19–34)

- Introduction to Law

- The Decalogue

- Book of the Covenant

- Law of Covenant Renewal

- Exodus and Tabernacle (Exodus 25–31, 35–40)

- Exodus and Theology

- History of Interpretation

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Ancient Egypt and the Hebrew Bible

- Ark of the Covenant

- Idol/Idolatry (HB/OT)

- Levi/Levites

- Names of God in the Hebrew Bible

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Latino/a and Latin American Biblical Interpretation

- Otherness in the Hebrew Bible

- Pain and Suffering in the Hebrew Bible

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Book of Exodus by Thomas B. Dozeman LAST REVIEWED: 13 September 2010 LAST MODIFIED: 13 September 2010 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195393361-0038

Exodus is the second book in the Torah, or Pentateuch, of the Hebrew Bible. It follows the story of the Israelite ancestors in Genesis, which concludes with the migration of Jacob’s family to Egypt during a time of famine. Exodus opens with the Israelites’ change of status from guests to slaves in the land of Egypt (Exodus 1–2), which sets the stage for the divine rescue of the Israelites from Egyptian slavery through the leadership of Moses (Exodus 3–15), their initial journey into the wilderness to the divine mountain (Exodus 16–18), and the divine revelation of law, the formation of a covenant, and the construction of a portable sanctuary at Mount Sinai (Exodus 19–40), before the story continues with the formation of the sacrificial cultic system in Leviticus, the formation of the wilderness camp in Numbers 1–10, and the second stage of the wilderness journey in Numbers 11–36. Exodus contains the core story of salvation for ancient Israel, the biography of the liberator and lawgiver, Moses, and the central religious rituals for celebrating salvation, including Passover, Unleavened Bread, First Fruits, Torah observance, and the guidelines for building the proper sanctuary for worship. The Book of Exodus contains a series of interpretations of these central themes, which has resulted in a complex history of composition, prompting a variety of questions about authorship, genre, historicity, and theology.

The Text of Exodus

Exodus is preserved in ancient and medieval tradition in a variety of different languages as illustrated in Würthwein 1995 , of which the Hebrew and Greek versions are the most important for the critical study of the text.

Würthwein, Ernst. The Text of the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Biblia Hebraica. Rev. ed. Translated by Erroll F. Rhodes. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1995.

This book provides an historical overview of the different ancient versions of the Bible.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Biblical Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Archaeology and Material Culture of Nabataea and the Nabat...

- Acts of Peter

- Acts of the Apostles

- Adam and Eve

- Aelia Capitolina

- Afterlife and Immortality

- Agriculture

- Alexander the Great

- Altered States of Consciousness in the Bible

- Ancient Christianity, Churches in

- Ancient Israel, Schools in

- Ancient Medicine

- Ancient Mesopotamia, Schools in

- Ancient Near Eastern Law

- Anti-Semitism and the New Testament

- Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha

- Apocryphal Acts

- Apostolic Fathers

- Archaeology and Material Culture of Ammon and the Ammonite...

- Archaeology and Material Culture of Aram and the Arameans

- Archaeology and Material Culture of Judah and the Judeans ...

- Archaeology and Material Culture of Moab and the Moabites

- Archaeology and Material Culture of Phoenicia and the Phoe...

- Archaeology and Material Culture of the Kingdom of Israel ...

- Archaeology, Greco-Roman

- Art, Early Christian

- Astrology and Astronomy

- Barnabas, Epistle of

- Benefaction/Patronage

- Bible and Film

- Bible and Visual Art

- Bible, Exile, and Migration, The

- Biblical Criticism

- Biblical Studies, Cognitive Science Approaches in

- Caesarea Maritima

- Canon, Biblical

- Child Metaphors in the New Testament

- Children in the Hebrew Bible

- Children in the New Testament World

- Christian Apocrypha

- Christology

- Chronicles, First and Second

- Cities of Refuge

- Clement, First

- Clement of Alexandria

- Clement, Second

- Conversation Analysis

- Corinthians, Second

- Cosmology, Near East

- Covenant, Ark of the

- Crucifixion

- Daniel, Additions to

- Death and Burial

- Deuteronomistic History

- Deuteronomy

- Diaspora in the New Testament

- Digital Humanities and the Bible

- Divination and Omens

- Domestic Architecture, Ancient Israel

- Early Christianity

- Ecclesiastes/Qohelet

- Economics and Biblical Studies

- Education, Greco-Roman

- Education in the Hebrew Bible

- Egyptian Book of the Dead

- Election in the Bible

- Epistles, Catholic

- Epistolography (Ancient Letters)

- Eschatology of the New Testament

- Esther and Additions to Esther

- Exodus, Book of

- Ezra-Nehemiah

- Faith in the New Testament

- Feminist Scholarship on the Old Testament

- Flora and Fauna of the Hebrew Bible

- Food and Food Production

- Friendship, Kinship and Enmity

- Funerary Rites and Practices, Greco-Roman

- Genesis, Book of

- God, Ancient Israel

- God, Greco-Roman

- God, Son of

- Gospels, Apocryphal

- Great, Herod the

- Greco-Roman Meals

- Greco-Roman World, Associations in the

- Greek Language

- Hebrew Bible, Biblical Law in the

- Hebrew Language

- Hellenistic and Roman Egypt

- Hermas, Shepherd of

- Historiography, Greco-Roman

- History of Ancient Israelite Religion

- Holy Spirit

- Honor and Shame

- Hosea, Book of

- Idol/Idolatry (New Testament)

- Imperial Cult and Early Christianity

- Infancy Gospel of Thomas

- Interpretation and Hermeneutics

- Intertextuality in the New Testament

- Israel, History of

- Jesus of Nazareth

- Jewish Christianity

- Jewish Festivals

- Joel, Book of

- John, Gospel of

- John the Baptist

- Jubilees, Book of

- Judaism, Hellenistic

- Judaism, Rabbinic

- Judaism, Second Temple

- Judas, Gospel of

- Jude, Epistle of

- Judges, Book of

- Judith, Book of

- Kings, First and Second

- Lamentations

- Letters, Johannine

- Letters, Pauline

- Levi/Levittes

- Levirate Obligation in the Hebrew Bible

- Levitical Cities

- LGBTIQ Hermeneutics

- Literacy, New Testament

- Literature, Apocalyptic

- Lord's Prayer

- Luke, Gospel of

- Maccabean Revolt

- Maccabees, First–Fourth

- Man, Son of

- Manasseh, King of Judah

- Manasseh, Tribe/Territory

- Mark, Gospel of

- Matthew, Gospel of

- Medieval Biblical Interpretation (Jewish)

- Mesopotamian Mythology and Genesis 1-11

- Midrash and Aggadah

- Minoritized Criticism of the New Testament

- Miracle Stories

- Modern Bible Translations

- Mysticism in Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity

- Myth in the Hebrew Bible

- Nahum, Book of

- New Testament and Early Christianity, Women, Gender, and S...

- New Testament, Feminist Scholarship on the

- New Testament, Men and Masculinity in the

- New Testament, Rhetoric of the

- New Testament, Social Sciences and the

- New Testament Studies, Emerging Approaches in

- New Testament, Textual Criticism of the

- New Testament Views of Torah

- Numbers, Book of

- Nuzi (Nuzi Tablets)

- Old Testament, Biblical Theology in the

- Old Testament, Social Sciences and the

- Orality and Literacy

- Passion Narratives

- Pauline Chronology

- Paul's Opponents

- Performance Criticism

- Period, The "Persian"

- Philippians

- Philistines

- Philo of Alexandria

- Piety/Godliness in Early Christianity and the Roman World

- Poetry, Hebrew

- Pontius Pilate

- Priestly/Holiness Codes

- Priest/Priesthood

- Pseudepigraphy, Early Christian

- Pseudo-Clementines

- Qumran/Dead Sea Scrolls

- Race, Ethnicity and the Gospels

- Revelation (Apocalypse)

- Samaria/Samaritans

- Samuel, First and Second

- Second Baruch

- Sects, Jewish

- Sermon on the Mount

- Sexual Violence and the Hebrew Bible

- Sin (Hebrew Bible/Old Testament)

- Solomon, Wisdom of

- Song of Songs

- Succession Narrative

- Synoptic Problem

- Tales, Court

- Temples and Sanctuaries

- Temples, Near Eastern

- Ten Commandments

- The Bible and the American Civil War

- The Bible and the Qur’an

- The Bible in China

- the Hebrew Bible, Ancient Egypt and

- The New Testament and Creation Care

- Thessalonians

- Thomas, Gospel of

- Trauma and the Bible, Hermeneutics of

- Twelve Prophets, Book of the

- Virtues and Vices: New Testament Ethical Exhortation in I...

- War, New Testament

- Wisdom—Greek and Latin

- Women, Gender, and Sexuality in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testa...

- Worship in the New Testament and Earliest Christianity

- Worship, Old Testament

- Zoology (Animals in the New Testament)

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.154]

- 81.177.182.154

Your browser does not support JavaScript. Please note, our website requires JavaScript to be supported.

Please contact us or click here to learn more about how to enable JavaScript on your browser.

- Change Country

- Resources /

- Insights on the Bible /

- The Pentateuch

Listen to Chuck Swindoll’s overview of Exodus in his audio message from the Classic series God’s Masterwork .

Who wrote the book?

As with Genesis, early Jewish traditions name Moses as the most likely and best qualified person to have authored Exodus. This theory is supported by a number of factors. Moses’s unique education in the royal courts of Egypt certainly provided him the opportunity and ability to pen these works (Acts 7:22). Internal evidence (material found within the text of Exodus itself ) adds support for Moses’s authorship. Many conversations, events, and geographical details could be known only by an eyewitness or participant. For example, the text reads: “Moses then wrote down everything the Lord had said,” (Exodus 24:4 NIV). Additionally, other biblical books refer to “the law of Moses” ( Joshua 1:7; 1 Kings 2:3), indicating that Exodus, which includes rules and regulations, was written by Moses. Jesus Himself introduced a quote from Exodus 20:12 and 21:17 with the words, “For Moses said” (Mark 7:10), confirming His own understanding of the book’s author.

The title “Exodus” comes from the Septuagint, which derived it from the primary event found in the book, the deliverance from slavery and “exodus” or departure of the Israelite nation out of Egypt by the hand of Yahweh, the God of their forefathers.

Where are we?

Exodus begins in the Egyptian region called Goshen. The people then traveled out of Egypt and, it is traditionally believed, moved toward the southern end of the Sinai Peninsula. They camped at Mount Sinai, where Moses received God’s commandments.

The book covers a period of approximately eighty years, from shortly before Moses’s birth (c. 1526 BC) to the events that occurred at Mount Sinai in 1446 BC.

Why is Exodus so important?

In Exodus we witness God beginning to fulfill His promises to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Though the children of Israel were enslaved in a foreign land, God miraculously and dramatically delivered them to freedom. He then established Israel as a theocratic nation under His covenant with Moses on Mount Sinai. The ten plagues, the Passover, the parting of the Red Sea, the fearsome majesty of God’s presence at Mount Sinai, the giving of the Ten Commandments, the building of the tabernacle . . . these events from Exodus are foundational to the Jewish faith. And they provide crucial background context to help future readers of Scripture understand the entire Bible’s message of redemption. The frequency of references to Exodus by various biblical writers, and even Jesus’s own words, testify to its importance.

What's the big idea?

The overall theme of Exodus is redemption—how God delivered the Israelites and made them His special people. After He rescued them from slavery, God provided the Law, which gave instructions on how the people could be consecrated or made holy. He established a system of sacrifice, which guided them in appropriate worship behavior. Just as significantly, God provided detailed directions on the building of His tabernacle, or tent. He intended to live among the Israelites and manifest His shekinah glory (Exodus 40:34–35)—another proof that they were indeed His people.

The Mosaic Covenant, unveiled initially through the Decalogue (Ten Commandments), provides the foundation for the beliefs and practices of Judaism, from common eating practices to complex worship regulations. Through the Law, God says that all of life relates to God. Nothing is outside His jurisdiction.

How do I apply this?

Like the Israelites who left Egypt, all believers in Christ are redeemed and consecrated to God. Under the Mosaic Covenant, people annually sacrificed unblemished animals according to specific regulations in order to have their sins covered, or borne, by that animal. The author of the New Testament book of Hebrews tells us, “But those sacrifices are an annual reminder of sins, because it is impossible for the blood of bulls and goats to take away sins” (Hebrews 10:3–4 NIV). Jesus’s sacrifice on the cross fulfilled the Law. As the perfect Lamb of God, He took away our sin permanently when He sacrificed Himself on our behalf. “We have been made holy through the sacrifice of the body of Jesus Christ once for all” (10:10 NIV).

Have you accepted His sacrifice on your behalf? Are you truly “redeemed”? If you’d like to learn about this, see “How to Begin a Relationship with God.”

Copyright ©️ 2009 by Charles R. Swindoll, Inc. All rights reserved worldwide.

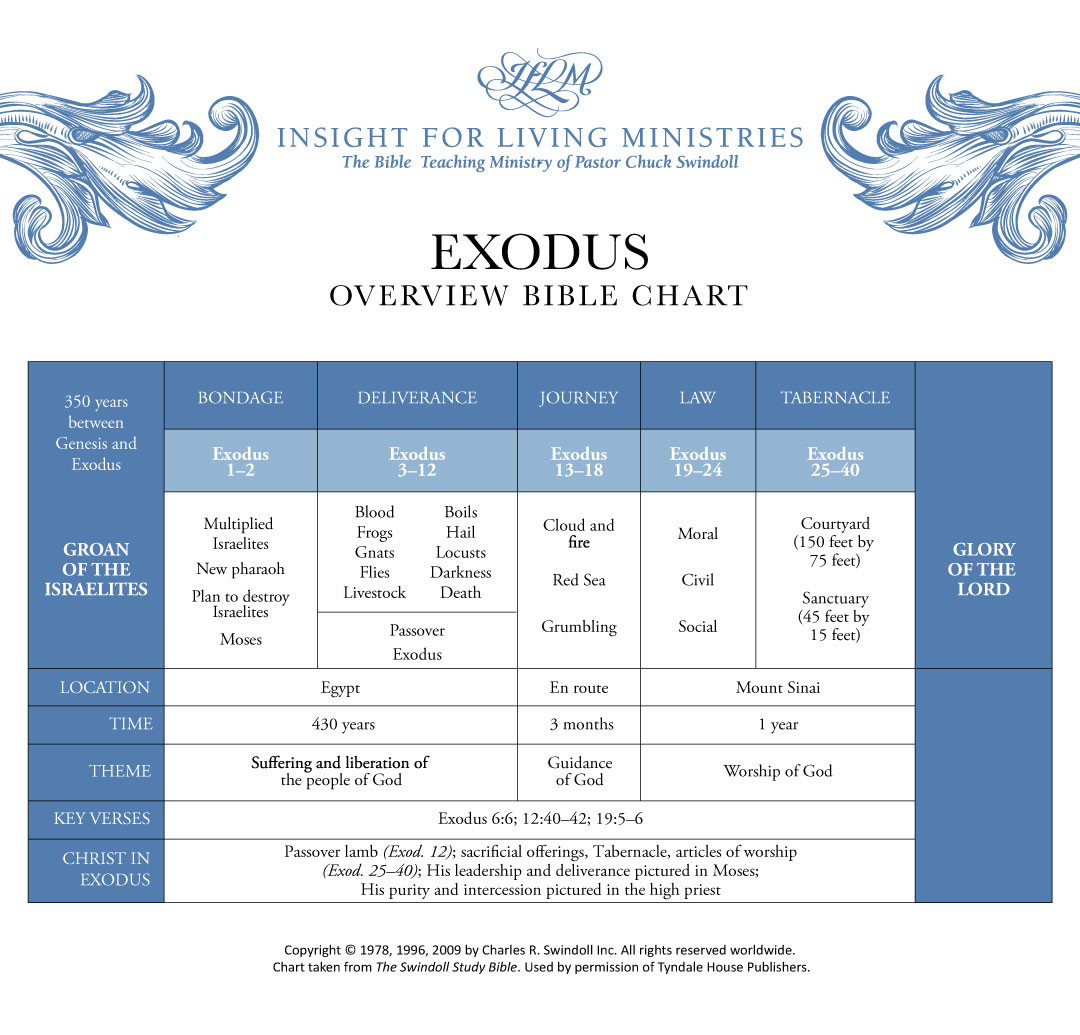

Bible Study Chart

Exodus overview chart.

View Chuck Swindoll's chart of Exodus , which divides the book into major sections and highlights themes and key verses.

View a list of Bible maps , excerpted from The Swindoll Study Bible.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- Submission site

- Why Publish?

- About The Journal of Theological Studies

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

The Book of Exodus: Composition, Reception, and Interpretation . Edited by T homas B. D ozeman , C raig A. E vans , and J oel N. L ohr .

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Graham Davies, The Book of Exodus: Composition, Reception, and Interpretation . Edited by T homas B. D ozeman , C raig A. E vans , and J oel N. L ohr ., The Journal of Theological Studies , Volume 67, Issue 2, October 2016, Pages 635–637, https://doi.org/10.1093/jts/flw149

- Permissions Icon Permissions

T his seventh volume in the series The Formation and Interpretation of Old Testament Literature contains twenty-four essays on Exodus (all in English, but some translated from German), divided into four groups: ‘General Topics’ (three), ‘Issues in Interpretation’ (eight), ‘Textual Transmission and Reception History’ (eleven), and ‘Exodus and Theology’ (two). Surprisingly, perhaps, the second half may prove to be of wider interest and use than the first half. So we shall begin at the end and work backwards. To those many readers who would expect the theology of Exodus to be focused on God, history, law, covenant, and perhaps divine presence, the topics chosen by Walter Brueggemann (‘The God who Gives Rest’) and Terence Fretheim (‘Issues of Agency in Exodus’) may be unexpected, especially when the latter proves to be about human agency as much as (or even more than) divine. What Fretheim has in mind is the action of God through agents that he does not control: as others have recognized, this is especially evident in Exodus 1–2 (not least in the action of women) and Fretheim, with some encouragement from 3:10–12 (Moses is appointed to ‘bring the Israelites out of Egypt’), uses it as a paradigm for the theological interpretation of the rest of the book. Not all, as Fretheim makes clear, would see it this way—a source-critic (there are still some of us left: see below!) might point out that it is especially in the Elohist strand of the narrative (compare also ch. 18) that such a theology is explicit. But Fretheim’s challenge to a one-sided emphasis on ‘divine action’ in Exodus is appropriate and liberating.

Brueggemann, who is well known for espousing a similar approach to the Old Testament, centres his essay on the gift of rest (or Sabbath), which proves to be an unexpectedly pervasive theme of Exodus—not just in the string of explicit textual references that he can assemble (which recalls the telling use of them in the Book of Jubilees which is detected by Lutz Doering in his contribution to the volume [pp. 490–6]), but as a plausible way of glossing the liberation of the Israelites from slave labour. It is, incidentally, in Exod. 16:29 (probably part of the older non-Priestly manna story) that what might be called Brueggemann’s ‘text’ can be found: ‘The Lord has given you the sabbath’ (cf. v. 26). The same connection between Sabbath and liberation has been seen, though Brueggemann does not mention him here, by Jürgen Moltmann (I am indebted to Dr Lidija Gunjevic for drawing this to my attention).

The third group of essays follows very much the same pattern as in the corresponding volume on Genesis (2012). Sidnie White Crawford’s survey of the Dead Sea Scrolls again concentrates, very usefully, on the interpretation of the book there (rather than on the biblical manuscripts, for which those interested will need to consult Armin Lange’s Handbuch ). Among the four essays on the main ancient versions those by Jerome Lund on the Syriac and by David Everson on the Latin have the most to offer, in part because they cover topics that are not as well known as the Septuagint and the Targumim. Bruce Chilton’s ‘The Exodus Theology of the Palestinian Targumim’ provides a succinct summary of his own extensive earlier work on ‘The Poem of the Four Nights’ found in various forms at Exod. 12:42 in Targum Neofiti 1 and elsewhere. In the section on reception history there are (in addition to Jubilees) studies of Philo, (parts of) the New Testament, Josephus, the Christian Fathers and Rabbinic commentary, of which the first and last (by G. E. Sterling and Burton Visotzky) are particularly valuable.

The first two groups of essays may be taken together as, with the exception of ‘Exodus and History’ by Lester Grabbe, they all provide the scholars concerned with the opportunity to present (and sometimes modify) their already published conclusions about a longer or shorter portion of the text. The ‘conclusions’ are predominantly about the origin of the passages in question (C. Dohmen on the Decalogue and H. Utzschneider on the Tabernacle are notable exceptions) and nearly all display the various kinds of redactional analysis which have become particularly prevalent in German-speaking scholarship in the past twenty-five years. The Preface says that ‘The contributors were invited with a view to representing the spectrum of opinion in the current interpretation of the Book of Exodus’ (p. ix), but by accident or design this has not been achieved in this part of the collection. The Genesis volume at least had contributions from Ronald Hendel and Baruch Schwartz to illustrate the older and still widely favoured source-critical model. This is not the place to engage (again!) in detailed argument with the trends that are prominent here. Suffice it to say that there continues to be much to be said, as argued by Ernest Nicholson in his The Pentateuch in the Twentieth Century (1998), for the detection of parallel accounts (or sources) deriving from different authors and traditions and for the broad distinction between substantial pre-exilic and exilic or post-exilic portions of the text. The current ‘avant-garde’ scholarship that appears here remains divided over several important issues (such as the nature of the Priestly Work) and its proliferation of late redactional layers often relies on minor similarities and differences of wording that make too little allowance for ancient authors’ literary competence (as noted by Suzanne Boorer in her essay on the ‘land oath’). One sometimes has the impression that more knowledge about the origin of texts is being sought than sound method and the evidence available will allow. A different kind of problem, compared with the scholarship of an earlier generation, is a much weakened sense for the contribution of inherited tradition to a body of literature like the Pentateuch. Recent studies of ancient Near Eastern scribal tradition have underlined how conservative it was even when it allowed for adaptation and innovation. The essays by Grabbe and David Wright (on the ‘Covenant Code’ in Exodus 20–3) have a different character from the rest (and from one another). The former examines a wide range of evidence and argument (but not the important correlation between ‘Hebrews’ and the ‘ apiru mentioned in Egyptian texts) and ends by stressing the difficulty of finding proof of a historical Exodus; while the latter concentrates on the many parallels with Babylonian laws and argues specifically for the composition of Israel’s ‘founding law text’ on the basis of the ancient laws of Hammurabi in the period of Assyrian domination in the eighth or seventh century bc . Both these contributions merit careful (if critical) study.

There is much that is valuable in this collection and the editors have provided helpful indexes of modern authors and of biblical and other references.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1477-4607

- Print ISSN 0022-5185

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Introduction to Exodus

Author and Date

Exodus (meaning exit) is best understood to have been written primarily by Moses, like the rest of the Pentateuch, though some details (such as the narrative of his death in Deuteronomy 34 ) were clearly added at a later time. It also appears that some language and references were updated for later readers. There is no consensus among scholars as to the date when the events of the exodus took place. A common view is that the exodus occurred in c. 1446 B.C. This is based on the calculation of 480 years from Israel’s departure from Egypt to the fourth year of Solomon’s reign (c. 966 B.C. ; see 1 Kings 6:1 ). However, because Exodus 1:11 depicts Israel working on a city called Raamses, some scholars believe that this would suggest that the exodus occurred during the reign of Raamses II in Egypt (c. 1279–1213 B.C. ), possibly around 1260 B.C. (see note on 1 Kings 6:1 ).

The overarching theme of Exodus is the fulfillment of God’s promises to the patriarchs. The success of the exodus must be credited to the power and purpose of God, who remembers his promises, punishes sin, and forgives the repentant. The book highlights Moses’ faithfulness and prayerfulness.

- Covenant promises. The events and instructions in Exodus are described as the Lord remembering his covenant promises to Abraham ( 2:24; 3:6, 14–17; 6:2–8 ). The promises extend to both Abraham’s descendants and all the nations of the world ( Gen. 12:1–3 ). They include land (which Israel will inhabit), numerous offspring (which will secure their ongoing identity), and blessing (God cares for them and other nations). The fulfillment of these promises is rooted in Israel’s covenant relationship with the Lord ( Gen. 17:7–8 ).

- Covenant mediator. Moses mediates between the Lord and his people. Through Moses the Lord reveals his purposes to Israel and sustains the covenant relationship.

- Covenant presence. God’s presence with his people is highlighted throughout the book of Exodus .

- Setting: Israel in Egypt ( 1:1–2:25 )

- Call of Moses ( 3:1–4:31 )

- Moses and Aaron: initial request ( 5:1–7:7 )

- Plagues and exodus ( 7:8–15:21 )

- Journey ( 15:22–18:27 )

- Setting: Sinai ( 19:1–25 )

- Covenant words and rules ( 20:1–23:33 )

- Covenant confirmed ( 24:1–18 )

- Instructions for the tabernacle ( 25:1–31:17 )

- Moses receives the tablets ( 31:18 )

- Covenant breach, intercession, and renewal ( 32:1–34:35 )

- Tabernacle: preparation for the presence ( 35:1–40:38 )

The Journey to Mount Sinai

Scholars disagree about the precise route of the exodus, but most agree that Mount Sinai is the site that today is called Jebel Musa (“Mountain of Moses”).

- Travel/Study

BIBLE HISTORY DAILY

The exodus: fact or fiction.

Evidence of Israel’s Exodus from Egypt

Dated to c. 1219 B.C.E., the Merneptah Stele is the earliest extrabiblical record of a people group called Israel. Set up by Pharaoh Merneptah to commemorate his military victories, the stele proclaims, “Ashkelon is carried off, and Gezer is captured. Yeno’am is made into nonexistence; Israel is wasted, its seed is not.” Ashkelon, Gezer and Yeno’am are followed by an Egyptian hieroglyph that designates a town. Israel is followed by a hieroglyph that means a people. Photo: Maryl Levine.

Is the biblical Exodus fact or fiction?

This is a loaded question. Although biblical scholars and archaeologists argue about various aspects of Israel’s Exodus from Egypt, many of them agree that the Exodus occurred in some form or another.

The question “Did the Exodus happen” then becomes “ When did the Exodus happen?” This is another heated question. Although there is much debate, most people settle into two camps: They argue for either a 15th-century B.C.E. or 13th-century B.C.E. date for Israel’s Exodus from Egypt.

The article “ Exodus Evidence: An Egyptologist Looks at Biblical History ” from the May/June 2016 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review 1 wrestles with both of these questions—“Did the Exodus happen?” and “When did the Exodus happen?” In the article, evidence is presented that generally supports a 13th-century B.C.E. Exodus during the Ramesside Period, when Egypt’s 19th Dynasty ruled.

The article examines Egyptian texts, artifacts and archaeological sites, which demonstrate that the Bible recounts accurate memories from the 13th century B.C.E. For instance, the names of three places that appear in the biblical account of Israel’s Exodus from Egypt correspond to Egyptian place names from the Ramesside Period (13th–11th centuries B.C.E.). The Bible recounts that, as slaves, the Israelites were forced to build the store-cities of Pithom and Ramses. After the ten plagues, the Israelites left Egypt and famously crossed the Yam Suph (translated Red Sea or Reed Sea), whose waters were miraculously parted for them. The biblical names Pithom, Ramses and Yam Suph (Red Sea or Reed Sea) correspond to the Egyptian place names Pi-Ramesse, Pi-Atum and (Pa-)Tjuf. These three place names appear together in Egyptian texts only from the Ramesside Period. The name Pi-Ramesse went out of use by the beginning of Egypt’s Third Intermediate Period, which began around 1085 B.C.E., and does not reappear until much later.

FREE ebook: Ancient Israel in Egypt and the Exodus .

These specific place names recorded in the biblical text demonstrate that the memory of the biblical authors for these traditions predates Egypt’s Third Intermediate Period. This supports a 13th-century Exodus during the Ramesside Period because it is only during the Ramesside Period that the place names Pi-Ramesse, Pi-Atum and (Pa-)Tjuf (Red Sea or Reed Sea) are all in use.

A worker’s house from western Thebes also seems to support a 13th-century Exodus. In the 1930s, archaeologists at the University of Chicago were excavating the mortuary Temple of Aya and Horemheb, the last two pharaohs of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty, in western Thebes. The temple was first built by Aya in the 14th-century B.C.E., but Horemheb usurped and expanded the temple when he became pharaoh. (He ruled from the late 14th century through the early 13th century B.C.E.) Horemheb chiseled out every place where Aya’s name had been and replaced it with his own. Later—during the reign of Ramses IV (12th century B.C.E.)—the Temple of Aya and Horemheb was demolished.

During their excavations, the University of Chicago uncovered a house and part of another house belonging to the workers who were given the task of demolishing the temple. The plan of the complete house is the same as that of the four-room house characteristic of Israelite dwellings during the Iron Age. However, unlike the Israelite models that were usually constructed of stone, the Theban house was made of wattle and daub. It is significant that this house was built in Egypt at the same time that Israelites were constructing four-room houses in Canaan . The similarities between the two have caused some to speculate that the builders of the Theban house were either proto-Israelites or a group closely related to the Israelites.

Is this a proto-Israelite house? This plan shows the 12th-century B.C.E. worker’s house in western Thebes next to the Temple of Aya and Horemheb. The house is undoubtedly a four-room house. In Canaan, the four-room house is considered an ethnic marker for the presence of Israelites during the Iron Age. Is the Biblical Exodus fact or fiction? This favors “fact,” so the question becomes, “ When did the Exodus happen?” The presence of such a house in Egypt during the 12th century B.C.E. seems to support an Exodus during the Ramesside Period. Photo: Courtesy of Manfred Bietak.

A third piece of evidence for the Exodus is the Onomasticon Amenope. The Onomasticon Amenope is a list of categorized words from Egypt’s Third Intermediate Period. Written in hieratic, the papyrus includes the Semitic place name b-r-k.t , which refers to the Lakes of Pithom. Even in Egyptian sources, the Semitic name for the Lakes of Pithom was used instead of the original Egyptian name. It is likely that a Semitic-speaking population lived in the region long enough that their name eventually supplanted the original.

Watch full-length lectures from the Out of Egypt: Israel’s Exodus Between Text and Memory, History and Imagination conference, which addressed some of the most challenging issues in Exodus scholarship. The international conference was hosted by Calit2’s Qualcomm Institute at UC San Diego in San Diego, CA.

Another compelling piece of evidence for the Exodus is found in the biblical text itself. A history of enslavement is likely to be true. The article explains:

The storyline of the Exodus, of a people fleeing from a humiliating slavery, suggests elements that are historically credible. Normally, it is only tales of glory and victory that are preserved in narratives from one generation to the next. A history of being slaves is likely to bear elements of truth.

Exodus: Fact or fiction? This four-room house from Izbet Sartah, Israel, shares many similarities with the 12th-century B.C.E. worker’s house uncovered in western Thebes. Photo: Israel Finkelstein/Tel Aviv University.

So, is the biblical Exodus fact or fiction? Scholars and people of many faiths line up on either side of the equation, and some say both. Archaeological discoveries have verified that parts of the biblical Exodus are historically accurate, but archaeology can’t tell us everything. Although archaeology can illuminate aspects of the past and bring parts of history to life, it has its limits.

It certainly is exciting when the archaeological record matches with the biblical account—as with the examples described here. However, while this evidence certainly adds weight to the historical accuracy of elements of the biblical account, it can’t be used to “prove” that every detail of the Exodus story in the Bible is true.

To learn more about evidence for Israel’s Exodus from Egypt, read the full article “ Exodus Evidence: An Egyptologist Looks at Biblical History ” in the May/June 2016 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review .

—————— Subscribers: Read the full article “ Exodus Evidence: An Egyptologist Looks at Biblical History ” in the May/June 2016 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review .

This Bible History Daily feature was originally published on April 10, 2016.

1. This BAR article is a free abstract from Manfred Bietak’s article “On the Historicity of the Exodus: What Egyptology Today Can Contribute to Assessing the Biblical Account of the Sojourn in Egypt” in Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider and William H.C. Propp, eds., Israel’s Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective: Text, Archaeology, Culture and Geoscience (Cham: Springer, 2015). In Bietak’s article, the scholarly debate about the archaeological remains and the onomastic data of Wadi Tumilat is more elaborately treated.

Related reading in Bible History Daily :

Exodus in the bible and the egyptian plagues, who was moses was he more than an exodus hero.

Akhenaten and Moses

Out of Egypt: Israel’s Exodus Between Text and Memory, History and Imagination

All-Access members, read more in the BAS Library :

Become a member of biblical archaeology society now and get more than half off the regular price of the all-access pass, explore the world’s most intriguing biblical scholarship.

Dig into more than 9,000 articles in the Biblical Archaeology Society’s vast library plus much more with an All-Access pass.

Related Posts

Pharaoh’s Brick Makers

By: Marek Dospěl

By: Biblical Archaeology Society Staff

Searching for Biblical Mt. Sinai

By: Robin Ngo

112 Responses

The five Books of Moses has be categorically determined that they are works of fiction, not facts. This is just as ridiculous as Aliens in Ancient times. You show one house and you say that it is Israelis and then jump to conclusions that the Exodus is real. Bonkers and bad archeology. Sorry to break it to all of you, Bible is fiction, just like Santa Clause.

Why are you so hateful towards Christians? Do you have some kind of grudge?

Hello Josh, I disagree! Here my own logic. Jesus Is Logical. I means he talks with Logic that Make Sense. In John 14:29 NASB Jesus said “29 Now I have told you before it happens, so that when it happens, you may believe.” The Logic here is If I tell you that it will storm tomorrow, you will say Big Deal. But if I say to you that it will storm 74 days from today at 1 pm in your town with orange rain, you will be very skeptical. You even may forget this conversation till it truly happen and then you will say that guy knows something, he told me exactly that!!! That is the The Logic of John 14:29 Here is a prophecy being fulfilled before your own eyes! In Mark 13:1-2 As He was going out of the temple, one of His disciples *said to Him, “Teacher, behold [a]what wonderful stones and [b]what wonderful buildings!” 2 And Jesus said to him, “Do you see these great buildings? Not one stone will be left upon another which will not be torn down.” Here is why this passage is important 1- At that time, there was no known imminent threat to the temple. 2- That Building, The Temple, was the Heart of The Jewish Life & Worship. They were willing to defend it with every thing 3- The destruction was not accomplished by The Jesus “Team, i.e. His Disciples” to fulfill their Boss prophecy 4- The one who did it were the Romans to crush the Jewish uprising. During that they believed that there were some gold between the stones, that is why they literally turned every stone. 5- The ones that is maintaining the Destruction till this moment are the Muslims who built the mosque on top of the Temple. 6- Islam came 6-7 centuries after Jesus!!! 7- Despite the Rich Jews worldwide, Despite Return to their Promised Land, Despite the Power of their Army, They Can Not Build The Most Important and Central Building in their lives!

Please go back to John 14:29 and be Candid with yourself, Is that humanly possible? Is that a Fiction?

If you are still in doubt, why you do not raise (Earnestly and Sincerely) your eyes to the Lord of Lords and Ask One Question, Please Help My Weak Faith, Show me Yourself! I can Assure you with one thing, If you are truthful and sincere, He will give evidence beyond any doubt. You will be The Most Fulfilled Person. You will be in my prayers. Blessings Brother

“Here is a prophecy being fulfilled before your own eyes! In Mark 13:1-2 As He was going out of the temple, one of His disciples *said to Him, “Teacher, behold [a]what wonderful stones and [b]what wonderful buildings!” 2 And Jesus said to him, “Do you see these great buildings? Not one stone will be left upon another which will not be torn down.””

This “prophecy” is a bit ridiculous to claim. In a time where civilizations conquered and destroyed each other, you are claiming a reference to a temple being destroyed is prophecy? Jerusalem was an occupied city near the outskirts of the Roman Empire, which was at war with the neighboring Persian Empire. That isn’t a prophecy at all to say a temple might be destroyed.

Also, the “Logic of John” could be applied to absolutely anyone who makes any predictions that are near true.