Office of the Provost

Guidance on authorship in scholarly or scientific publications, general principles.

The public’s trust in and benefit from academic research and scholarship relies upon all those involved in the scholarly endeavor adhering to the highest ethical standards, including standards related to publication and dissemination of findings and conclusions.

Accordingly, all scholarly or scientific publications involving faculty, staff, students and/or trainees arising from academic activities performed under the auspices of Yale University must include appropriate attribution of authorship and disclosure of relevant affiliations of those involved in the work, as described below.

These publications, which, for the purposes of this guidance, include articles, abstracts, manuscripts submitted for publication, presentations at professional meetings, and applications for funding, must appropriately acknowledge contributions of colleagues involved in the design, conduct or dissemination of the work by neither overly attributing contribution nor ignoring meaningful contributions.

Financial and other supporting relationships of those involved in the scholarly work must be transparent and disclosed in publications arising from the work.

Authorship Standards

Authorship of a scientific or scholarly paper should be limited to those individuals who have contributed in a meaningful and substantive way to its intellectual content. All authors are responsible for fairly evaluating their roles in the project as well as the roles of their co-authors to ensure that authorship is attributed according to these standards in all publications for which they will be listed as an author.

Requirement for Attribution of Authorship

Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for its content. All co-authors should have been directly involved in all three of the following:

- planning and contribution to some component (conception, design, conduct, analysis, or interpretation) of the work which led to the paper or interpreting at least a portion of the results;

- writing a draft of the article or revising it for intellectual content; and

- final approval of the version to be published. All authors should review and approve the manuscript before it is submitted for publication, at least as it pertains to their roles in the project.

Some diversity exists across academic disciplines regarding acceptable standards for substantive contributions that would lead to attribution of authorship. This guidance is intended to allow for such variation to disciplinary best practices while ensuring authorship is not inappropriately assigned.

Lead Author

The first author is usually the person who has performed the central experiments of the project. Often, this individual is also the person who has prepared the first draft of the manuscript. The lead author is ultimately responsible for ensuring that all other authors meet the requirements for authorship as well as ensuring the integrity of the work itself. The lead author will usually serve as the corresponding author.

Co-Author(s)

Each co-author is responsible for considering his or her role in the project and whether that role merits attribution of authorship. Co-authors should review and approve the manuscript, at least as it pertains to their roles in the project.

External Collaborators, Including Sponsor or Industry Representatives

Individuals who meet the criteria for authorship should be included as authors irrespective of their institutional affiliations. In general, the use of “ghostwriters” is prohibited, i.e., individuals who have contributed significant portions of the text should be named as authors or acknowledged in the final publication. Industry representatives or others retained by industry who contribute to an article and meet the requirements for authorship or acknowledgement must be appropriately listed as contributors or authors on the article and their industry affiliation must be disclosed in the published article.

Acknowledgements

Individuals who do not meet the requirements for authorship but who have provided a valuable contribution to the work should be acknowledged for their contributing role as appropriate to the publication.

Courtesy or Gift Authorship

Individuals do not satisfy the criteria for authorship merely because they have made possible the conduct of the research and/or the preparation of the manuscript. Under no circumstance should individuals be added as co-authors based on the individual’s stature as an attempt to increase the likelihood of publication or credibility of the work. For example, heading a laboratory, research program, section, or department where the research takes place does not, by itself, warrant co-authorship of a scholarly paper. Nor should “gift” co-authorship be conferred on those whose only contributions have been to provide, for example, routine technical services, to refer patients or participants for a study, to provide a valuable reagent, to assist with data collection and assembly, or to review a completed manuscript for suggestions. Although not qualifying as co-authors, individuals who assist the research effort may warrant appropriate acknowledgement in the completed paper.

Senior faculty members should be named as co-authors on work independently generated by their junior colleagues only if they have made substantial intellectual contributions to the experimental design, interpretation of findings and manuscript preparation.

Authorship Disputes

Determinations of authorship roles are often complex, delicate and potentially controversial. To avoid confusion and conflict, discussion of attribution should be initiated early in the development of any collaborative publication. For disputes that cannot be resolved amicably, individuals may seek the guidance of the dean of their school or the cognizant deputy provost in the Faculty of Arts & Sciences.

Disclosure of Research Funding and Other Support

In all scientific and scholarly publications and all manuscripts submitted for publication, authors should acknowledge the sources of support for all activities leading to and facilitating preparation of the publication or manuscript, including, but not limited to:

- grant, contract, and gift support;

- salary support if other than institutional funds. Note that salary support that is provided to the University by an external entity does not constitute institutional funds by virtue of being distributed by the University; and

- technical or other support if substantive and meaningful to the completion of the project.

Disclosure of Financial Interests and External Activities

Authors should fully disclose related financial interests and outside activities in publications (including articles, abstracts, manuscripts submitted for publication), presentations at professional meetings, and applications for funding.

In addition, authors should comply with the disclosure requirements of the University’s Committee on Conflict of Interest.

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Order Authors in Scientific Papers

It’s rare that an article is authored by only one or two people anymore. In fact, the average original research paper has five authors these days. The growing list of collaborative research projects raises important questions regarding the author order for research manuscripts and the impact an author list has on readers’ perceptions.

With a handful of authors, a group might be inclined to create an author name list based on the amount of work contributed. What happens, though, when you have a long list of authors? It would be impractical to rank the authors by their relative contributions. Additionally, what if the authors contribute relatively equal amounts of work? Similarly, if a study was interdisciplinary (and many are these days), how can one individual’s contribution be deemed more significant than another’s?

Why does author order matter?

Although an author list should only reflect those who have made substantial contributions to a research project and its draft manuscript (see, for example, the authorship guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors ), we’d be remiss to say that author order doesn’t matter. In theory, everyone on the list should be credited equally since it takes a team to successfully complete a project; however, due to industry customs and other practical limitations, some authors will always be more visible than others.

The following are some notable implications regarding author order.

- The “first author” is a coveted position because of its increased visibility. This author is the first name readers will see, and because of various citation rules, publications are usually referred to by the name of the first author only. In-text or bibliographic referencing rules, for example, often reduce all other named authors to “et al.” Since employers use first-authorship to evaluate academic personnel for employment, promotion, and tenure, and since graduate students often need a number of first-author publications to earn their degree, being the lead author on a manuscript is crucial for many researchers, especially early in their career.

- The last author position is traditionally reserved for the supervisor or principal investigator. As such, this person receives much of the credit when the research goes well and the flak when things go wrong. The last author may also be the corresponding author, the person who is the primary contact for journal editors (the first author could, however, fill this role as well, especially if they contributed most to the work).

- Given that there is no uniform rule about author order, readers may find it difficult to assess the nature of an author’s contribution to a research project. To address this issue, some journals, particularly medical ones, nowadays insist on detailed author contribution notes (make sure you check the target journal guidelines before submission to find out how the journal you are planning to submit to handles this). Nevertheless, even this does little to counter how strongly citation rules have enhanced the attention first-named authors receive.

Common Methods for Listing Authors

The following are some common methods for establishing author order lists.

- Relative contribution. As mentioned above, the most common way authors are listed is by relative contribution. The author who made the most substantial contribution to the work described in an article and did most of the underlying research should be listed as the first author. The others are ranked in descending order of contribution. However, in many disciplines, such as the life sciences, the last author in a group is the principal investigator or “senior author”—the person who often provides ideas based on their earlier research and supervised the current work.

- Alphabetical list . Certain fields, particularly those involving large group projects, employ other methods . For example, high-energy particle physics teams list authors alphabetically.

- Multiple “first” authors . Additional “first” authors (so-called “co-first authors”) can be noted by an asterisk or other symbols accompanied by an explanatory note. This practice is common in interdisciplinary studies; however, as we explained above, the first name listed on a paper will still enjoy more visibility than any other “first” author.

- Multiple “last” authors . Similar to recognizing several first authors, multiple last authors can be recognized via typographical symbols and footnotes. This practice arose as some journals wanted to increase accountability by requiring senior lab members to review all data and interpretations produced in their labs instead of being awarded automatic last-authorship on every publication by someone in their group.

- Negotiated order . If you were thinking you could avoid politics by drowning yourself in research, you’re sorely mistaken. While there are relatively clear guidelines and practices for designating first and last authors, there’s no overriding convention for the middle authors. The list can be decided by negotiation, so sharpen those persuasive argument skills!

As you can see, choosing the right author order can be quite complicated. Therefore, we urge researchers to consider these factors early in the research process and to confirm this order during the English proofreading process, whether you self-edit or received manuscript editing or paper editing services , all of which should be done before submission to a journal. Don’t wait until the manuscript is drafted before you decide on the author order in your paper. All the parties involved will need to agree on the author list before submission, and no one will want to delay submission because of a disagreement about who should be included on the author list, and in what order (along with other journal manuscript authorship issues).

On top of that, journals sometimes have clear rules about changing authors or even authorship order during the review process, might not encourage it, and might require detailed statements explaining the specific contribution of every new/old author, official statements of agreement of all authors, and/or a corrigendum to be submitted, all of which can further delay the publication process. We recommend periodically revisiting the named author issue during the drafting stage to make sure that everyone is on the same page and that the list is updated to appropriately reflect changes in team composition or contributions to a research project.

If you’ve done more than a handful of citations during your research career, you’ve seen examples of lead and co-authorship in action. This behavior of labeling writers of a paper is becoming more and more common as teamwork in the field of academics takes on steam.

Although it’s not uncommon to have multiple authors on one paper, differentiating between a co-author and the lead author isn’t as cut and dried as one might assume. The first name in the citation would make you believe that this placement means the author did the majority share of the work in the research and writing process. But determining who did more than someone else isn’t something everyone agrees upon, and if this isn’t delineated clearly before the work begins, it can lead to misunderstandings and possible misconduct.

Defining Each Role

Before you start working with a partner, one of the very first things you should do is communicate regarding each other’s definition of authorship. Coming to an agreement early can minimize any arguments or dissent before publishing the works.

To help you get started, here are the working definitions of lead and co-authors according to the accepted principles of academic publishing:

● A lead author is an individual that has likely initiated the research topic and carried out the research. They take the load of the writing and editing tasks on their shoulders, beginning the document, adding the majority of the content, running final drafts through editing tools, or hiring an editor to review the manuscript. Their name is typically listed first on the manuscript’s authorship sections.

● Co-authors, on the other hand, will collaborate with the lead author. They are listed as an author because they make a significant contribution to the research and the paper, but it is not a majority contribution. They may come into the project after the lead author has begun the process of creating the experiment and finding funding, but they share the responsibility and accountability for the final outcome.

Use these two definitions to determine who in the team is going to do what tasks, then decide in writing who the lead and co-authors will be. This can be adjusted later with everyone’s approval should one person fail to fill their roles, or another step up and replace a lead author.

Factors Used When Splitting Up Attribution

Still not sure how to split the hairs when it comes to attribution? There are some factors that eliminate assumptions and capitalize on factual data—you know, the stuff that every researcher can agree upon.

Because the label of author vs. co-author can make a major difference in one’s career, both academically and financially, this is a designation to take very seriously. In a new team, or with a new member of the team, these rules tend to get rid of gray areas:

● Lead authors make substantial contributions throughout almost every stage of the work, including acquisition, interpretation of data, analysis, and outcome

● Lead authors draft the work and play a major role in the critical revisions prior to publishing

● Lead authors have final approval of the work before it is sent in for approval or rejection from a publishing agency

● The team agrees that everyone is accountable for their part of the work, but a lead author takes accountability for the entire project, whether the active part of the job was theirs or not

● The lead author is the one who is questioned if there are any inaccuracies or questions of integrity; this person follows these investigations through their resolution.

When you clearly display the role of a lead author, many people who thought they wanted the job description don’t mind taking a step back. It’s a lot of pressure, and a hefty load of responsibility in the event that the work has any accountability or integrity issues called into question.

Monitoring Your Authorship With Impactio

However, whether you’re a lead author or your name falls behind someone else’s on the publication, it’s important to follow your authorship impact. You can do this with Impactio’s research tools. Impactio is America’s leading platform in academic analytics tools, and the free report features let you clearly see where your work is leading the way or falling short in certain areas.

With Impactio, you can build a team of professionals from all over the world, work together to come up with authorship decisions, and complete almost all the research you need by connecting online. When you’re ready to boost your professional reputation, start with Impactio.

- Afghanistan

- Åland Islands

- American Samoa

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Bolivia (Plurinational State of)

- Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Bouvet Island

- British Indian Ocean Territory

- Brunei Darussalam

- Burkina Faso

- Cayman Islands

- Central African Republic

- Christmas Island

- Cocos (Keeling) Islands

- Congo (Democratic Republic of the)

- Cook Islands

- Côte d'Ivoire

- Curacao !Curaçao

- Dominican Republic

- El Salvador

- Equatorial Guinea

- Falkland Islands (Malvinas)

- Faroe Islands

- French Guiana

- French Polynesia

- French Southern Territories

- Guinea-Bissau

- Heard Island and McDonald Islands

- Iran (Islamic Republic of)

- Isle of Man

- Korea (Democratic Peoples Republic of)

- Korea (Republic of)

- Lao People's Democratic Republic

- Liechtenstein

- Marshall Islands

- Micronesia (Federated States of)

- Moldova (Republic of)

- Netherlands

- New Caledonia

- New Zealand

- Norfolk Island

- North Macedonia

- Northern Mariana Islands

- Palestine, State of

- Papua New Guinea

- Philippines

- Puerto Rico

- Russian Federation

- Saint Barthélemy

- Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha

- Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Saint Lucia

- Saint Martin (French part)

- Saint Pierre and Miquelon

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Sao Tome and Principe

- Saudi Arabia

- Sierra Leone

- Sint Maarten (Dutch part)

- Solomon Islands

- South Africa

- South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

- South Sudan

- Svalbard and Jan Mayen

- Switzerland

- Syrian Arab Republic

- Tanzania, United Republic of

- Timor-Leste

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Turkmenistan

- Turks and Caicos Islands

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

- United States of America

- United States Minor Outlying Islands

- Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of)

- Virgin Islands (British)

- Virgin Islands (U.S.)

- Wallis and Futuna

- Western Sahara

Loading metrics

Open Access

Ten simple rules for collaboratively writing a multi-authored paper

* E-mail: [email protected]

¶ ‡ MAF is the lead author. All authors contributed equally to this work. Besides for MAF, author order was computed randomly.

Affiliation Australian Rivers Institute, Griffith University, Nathan, Queensland, Australia

Affiliation Department of Ecology and Environmental Science, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden

Affiliation Marine Institute, Furnace, Newport, Co. Mayo, Ireland

Affiliation Center for Environmental Research, Education and Outreach, Washington State University, Pullman, Washington, United States of America

Affiliation UFZ, Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research, Department of Lake Research, Magdeburg, Germany

Affiliation Department of Biology, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Affiliation Department of Biology, Pomona College, Claremont, California, United States of America

Affiliation Department of Ecology and Genetics/Limnology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

Affiliation Department of Geography, Geology, and the Environment, Illinois State University, Normal, Illinois, United States of America

Affiliation Department of Biological Sciences, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia, United States of America

Affiliation Catalan Institute for Water Research (ICRA), Girona, Spain

- Marieke A. Frassl,

- David P. Hamilton,

- Blaize A. Denfeld,

- Elvira de Eyto,

- Stephanie E. Hampton,

- Philipp S. Keller,

- Sapna Sharma,

- Abigail S. L. Lewis,

- Gesa A. Weyhenmeyer,

Published: November 15, 2018

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006508

- Reader Comments

Citation: Frassl MA, Hamilton DP, Denfeld BA, de Eyto E, Hampton SE, Keller PS, et al. (2018) Ten simple rules for collaboratively writing a multi-authored paper. PLoS Comput Biol 14(11): e1006508. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006508

Editor: Fran Lewitter, Whitehead Institute, UNITED STATES

Copyright: © 2018 Frassl et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This work was supported by the Global Lake Ecological Observatory Network (GLEON; www.gleon.org ). ML and PK received the GLEON student travel fund. GW was supported by the Swedish Research Council, Grant No. 2016-04153. NC had the support of the Beatriu de Pinós postdoctoral programme (BP-2016-00215). PK was supported by the DFG (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, grant SP 1570/1-1). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Science is increasingly done in large teams [ 1 ], making it more likely that papers will be written by several authors from different institutes, disciplines, and cultural backgrounds. A small number of “Ten simple rules” papers have been written on collaboration [ 2 , 3 ] and on writing [ 4 , 5 ] but not on combining the two. Collaborative writing with multiple authors has additional challenges, including varied levels of engagement of coauthors, provision of fair credit through authorship or acknowledgements, acceptance of a diversity of work styles, and the need for clear communication. Miscommunication, a lack of leadership, and inappropriate tools or writing approaches can lead to frustration, delay of publication, or even the termination of a project.

To provide insight into collaborative writing, we use our experience from the Global Lake Ecological Observatory Network (GLEON) [ 6 ] to frame 10 simple rules for collaboratively writing a multi-authored paper. We consider a collaborative multi-authored paper to have three or more people from at least two different institutions. A multi-authored paper can be a result of a single discrete research project or the outcome of a larger research program that includes other papers based on common data or methods. The writing of a multi-authored paper is embedded within a broader context of planning and collaboration among team members. Our recommended rules include elements of both the planning and writing of a paper, and they can be iterative, although we have listed them in numerical order. It will help to revisit the rules frequently throughout the writing process. With the 10 rules outlined below, we aim to provide a foundation for writing multi-authored papers and conducting exciting and influential science.

Rule 1: Build your writing team wisely

The writing team is formed at the beginning of the writing process. This can happen at different stages of a research project. Your writing team should be built upon the expertise and interest of your coauthors. A good way to start is to review the initial goal of the research project and to gather everyone’s expectations for the paper, allowing all team members to decide whether they want to be involved in the writing. This step is normally initiated by the research project leader(s). When appointing the writing team, ensure that the team has the collective expertise required to write the paper and stay open to bringing in new people if required. If you need to add a coauthor at a later stage, discuss this first with the team ( Rule 8 ) and be clear as to how the person can contribute to the paper and qualify as a coauthor (Rules 4 and 10 ). When in doubt about selecting coauthors, in general we suggest to opt for being inclusive. A shared list with contact information and the contribution of all active coauthors is useful for keeping track of who is involved throughout the writing process.

In order to share the workload and increase the involvement of all coauthors during the writing process, you can distribute specific roles within the team (e.g., a team leader and a facilitator [see Rule 2 ] and a note taker [see Rule 8 ]).

Rule 2: If you take the lead, provide leadership

Leadership is critical for a multi-authored paper to be written in a timely and satisfactory manner. This is especially true for large, joint projects. The leader of the writing process and first author typically are the same person, but they don’t have to be. The leader is the contact person for the group, keeps the writing moving forward, and generally should manage the writing process through to publication. It is key that the leader provides strong communication and feedback and acknowledges contributions from the group. The leader should incorporate flexibility with respect to timelines and group decisions. For different leadership styles, refer to [ 7 , 8 ].

When developing collaborative multi-authored papers, the leader should allow time for all voices to be heard. In general, we recommend leading multi-authored papers through consensus building and not hierarchically because the manuscript should represent the views of all authors ( Rule 9 ). At the same time, the leader needs to be able to make difficult decisions about manuscript structure, content, and author contributions by maintaining oversight of the project as a whole.

Finally, a good leader must know when to delegate tasks and share the workload, e.g., by delegating facilitators for a meeting or assigning responsibilities and subleaders for sections of a manuscript. At times, this may include recognizing that something has changed, e.g., a change in work commitments by a coauthor or a shift in the paper’s focus. In such a case, it may be timely for someone else to step in as leader and possibly also as first author, while the previous leader’s work is acknowledged in the manuscript or as a coauthor ( Rule 4 ).

Rule 3: Create a data management plan

If not already implemented at the start of the research project, we recommend that you implement a data management plan (DMP) that is circulated at an early stage of the writing process and agreed upon by all coauthors (see also [ 9 ] and https://dmptool.org/ ; https://dmponline.dcc.ac.uk/ ). The DMP should outline how project data will be shared, versioned, stored, and curated and also details of who within the team will have access to the (raw) data during and post publication.

Multi-authored papers often use and/or produce large datasets originating from a variety of sources or data contributors. Each of these sources may have different demands about how data and code are used and shared during analysis and writing and after publication. Previous articles published in the “Ten simple rules” series provide guidance on the ethics of big-data research [ 10 ], how to enable multi-site collaborations through open data sharing [ 3 ], how to store data [ 11 ], and how to curate data [ 12 ]. As many journals now require datasets to be shared through an open access platform as a prerequisite to paper publication, the DMP should include detail on how this will be achieved and what data (including metadata) will be included in the final dataset.

Your DMP should not be a complicated, detailed document and can often be summarized in a couple of paragraphs. Once your DMP is finalized, all data providers and coauthors should confirm that they agree with the plan and that their institutional and/or funding agency obligations are met. It is our experience within GLEON that these obligations vary widely across the research community, particularly at an intercontinental scale.

Rule 4: Jointly decide on authorship guidelines

Defining authorship and author order are longstanding issues in science [ 13 ]. In order to avoid conflict, you should be clear early on in the research project what level of participation is required for authorship. You can do this by creating a set of guidelines to define the contributions and tasks worthy of authorship. For an authorship policy template, see [ 14 ] and check your institute’s and the journal’s authorship guidelines. For example, generating ideas, funding acquisition, data collection or provision, analyses, drafting figures and tables, and writing sections of text are discrete tasks that can constitute contributions for authorship (see, e.g., the CRediT system: http://docs.casrai.org/CRediT [ 15 ]). All authors are expected to participate in multiple tasks, in addition to editing and approving the final document. It is debated whether merely providing data does qualify for coauthorship. If data provision is not felt to be grounds for coauthorship, you should acknowledge the data provider in the Acknowledgments [ 16 ].

Your authorship guidelines can also increase transparency and help to clarify author order. If coauthors have contributed to the paper at different levels, task-tracking and indicating author activity on various tasks can help establish author order, with the person who contributed most in the front. Other options include groupings based on level of activity [ 17 ] or having the core group in the front and all other authors listed alphabetically. If every coauthor contributed equally, you can use alphabetical order [ 18 ] or randomly assigned order [ 19 ]. Joint first authorship should be considered when appropriate. We encourage you to make a statement about author order (e.g., [ 19 ]) and to generate authorship attribution statements; many journals will include these as part of the Acknowledgments if a separate statement is not formally required. For those who do not meet expectations for authorship, an alternative to authorship is to list contributors in the Acknowledgments [ 15 ]. Be aware of coauthors’ expectations and disciplinary, cultural, and other norms in what constitutes author order. For example, in some disciplines, the last author is used to indicate the academic advisor or team leader. We recommend revisiting definitions of authorship and author order frequently because roles and responsibilities may change during the writing process.

Rule 5: Decide on a writing strategy

The writing strategy should be adapted according to the needs of the team (white shapes in Fig 1 ) and based on the framework given through external factors (gray shapes in Fig 1 ). For example, a research paper that uses wide-ranging data might have several coauthors but one principal writer (e.g., a PhD candidate) who was conducting the analysis, whereas a comment or review in a specific research field might be written jointly by all coauthors based on parallel discussion. In most cases, the approach that everyone writes on everything is not possible and is very inefficient. Most commonly, the paper is split into sub-sections based on what aspects of the research the coauthors have been responsible for or based on expertise and interest of the coauthors. Regardless of which writing strategy you choose, the importance of engaging all team members in defining the narrative, format, and structure of the paper cannot be overstated; this will preempt having to rewrite or delete sections later.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Different writing strategies ranging from very inclusive to minimally inclusive: group writing = everyone writes on everything; subgroup writing = document is split up into expertise areas, each individual contributes to a subsection; core writing group = a subgroup of a few coauthors writes the paper; scribe writing = one person writes based on previous group discussions; principal writer = one person drafts and writes the paper (writing styles adapted from [ 20 ]). Which writing strategy you choose depends on external factors (filled, gray shapes), such as the interdisciplinarity of the study or the time pressure of the paper to be published, and affects the payback (dashed, white shapes). An increasing height of the shape indicates an increasing quantity of the decision criteria, such as the interdisciplinarity, diversity, feasibility, etc.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006508.g001

For an efficient writing process, try to use the active voice in suggestions and make direct edits rather than simply stating that a section needs revision. For all writing strategies, the lead author(s) has to ensure that the completed text is cohesive.

Rule 6: Choose digital tools to suit your needs

A suitable technology for writing your multi-authored paper depends upon your chosen writing approach ( Rule 5 ). For projects in which the whole group writes together, synchronous technologies such as Google Docs or Overleaf work well by allowing for interactive writing that facilitates version control (see also [ 21 ]). In contrast, papers written sequentially, in parallel by subsections, or by only one author may allow for using conventional programs such as Microsoft Word or LibreOffice. In any case, you should create a plan early on for version control, comments, and tracking changes. Regularly mark the version of the document, e.g., by including the current date in the file name. When working offline and distributing the document, add initials in the file name to indicate the progress and most recent editor.

High-quality communication is important for efficient discussion on the paper’s content. When picking a virtual meeting technology, consider the number of participants permitted in a single group call, ability to record the meeting, audio and visual quality, and the need for additional features such as screencasting or real-time notes. Especially for large groups, it can be helpful for people who are not currently speaking to mute their microphones (blocking background noise), to use the video for nonverbal communication (e.g., to show approval or rejection and to help nonnative speakers), or to switch off the video when internet speeds are slow. More guidelines for effective virtual meetings are available in Hampton and colleagues [ 22 ].

In between virtual meetings, virtual technologies can help to streamline communication (e.g., https://slack.com ) and can facilitate the writing process through shared to-do lists and task boards including calendar features (e.g., http://trello.com ).

With all technologies, accessibility, ease of use, and cost are important decision criteria. Note that some coauthors will be very comfortable with new technologies, whereas others may not be. Both should be ready to compromise in order to be as efficient and inclusive as possible. Basic training in unfamiliar technologies will likely pay off in the long term.

Rule 7: Set clear timelines and adhere to them

As for the overall research project, setting realistic and effective deadlines maintains the group’s momentum and facilitates on-schedule paper completion [ 23 ]. Before deciding to become a coauthor, consider your own time commitments. As a coauthor, commit to set deadlines, recognize the importance of meeting them, and notify the group early on if you realize that you will not be able to meet a deadline or attend a meeting. Building consensus around deadlines will ensure that internally imposed deadlines are reasonably timed [ 23 ] and will increase the likelihood that they are met. Keeping to deadlines and staying on task require developing a positive culture of encouragement within the team [ 14 ]. You should respect people’s time by being punctual for meetings, sending out drafts and the meeting agenda on schedule, and ending meetings on time.

To develop a timeline, we recommend starting by defining the “final” deadline. Occasionally, this date will be set “externally” (e.g., by an editorial request), but in most cases, you can set an internal consensus deadline. Thereafter, define intermediate milestones with clearly defined tasks and the time required to fulfill them. Look for and prioritize strategies that allow multiple tasks to be completed simultaneously because this allows for a more efficient timeline. Keep in mind that “however long you give yourself to complete a task is how long it will take” [ 24 ] and that group scheduling will vary depending on the selected writing strategy ( Rule 5 ). Generally, collaborative manuscripts need more draft and revision rounds than a “solo” article.

Rule 8: Be transparent throughout the process

This rule is important for the overall research project but becomes especially important when it comes to publishing and coauthorship. Being as open as possible about deadlines ( Rule 7 ) and expectations (including authorship, Rule 4 ) helps to avoid misunderstandings and conflict. Be clear about the consequences if someone does not follow the group’s rules but also be open to rediscuss rules if needed. Potential consequences of not following the group’s rules include a change in author order or removing authorship. It should also be clear that a coauthor’s edits might not be included in the final text if s/he does not contribute on time. Bad experience from past collaboration can lead to exclusion from further research projects.

As for collaboration [ 2 ], communication is key. During meetings, decide on a note taker who keeps track of the group’s discussions and decisions in meeting notes. This will help coauthors who could not attend the meeting as well as help the whole group follow up on decisions later on. Encourage everyone to provide feedback and be sincere and clear if something is not working—writing a multi-authored paper is a learning process. If you feel someone is frustrated, try to address the issue promptly within the group rather than waiting and letting the problem escalate. When resolving a conflict, it is important to actively listen and focus the conversation on how to reach a solution that benefits the group as a whole [ 25 ]. Democratic decisions can often help to resolve differing opinions.

Rule 9: Cultivate equity, diversity, and inclusion

Multi-authored papers will likely have a team of coauthors with diverse demographics and cultural values, which usually broadens the scope of knowledge, experience, and background. While the benefit of a diverse team is clear [ 14 ], successfully integrating diversity in a collaborative team effort requires increased awareness of differences and proactive conflict management [ 25 ]. You can cultivate diversity by holding members accountable to equity, diversity, and inclusivity guidelines (e.g., https://www.ryerson.ca/edistem/ ).

If working across cultures, you will need to select the working language (both for verbal and written communications); this is most commonly the publication language. When team members are not native speakers in the working language, you should always speak slowly, enunciate clearly, and avoid local expressions and acronyms, as well as listen closely and ask questions if you do not understand. Besides language, be empathetic when listening to others’ opinions in order to genuinely understand your coauthors’ points of view [ 26 ].

When giving verbal or written feedback, be constructive but also be aware of how different cultures receive and react to feedback [ 27 ]. Inclusive writing and speaking provide engagement, e.g., “ we could do that,” and acknowledge input between peers. In addition, you can create opportunities for expression of different personalities and opinions by adopting a participatory group model (e.g., [ 28 ]).

Rule 10: Consider the ethical implications of your coauthorship

Being a coauthor is both a benefit and a responsibility: having your name on a publication implies that you have contributed substantially, that you are familiar with the content of the paper, and that you have checked the accuracy of the content as best you can. To conduct a self-assessment as to whether your contributions merit coauthorship, start by revisiting authorship guidelines for your group ( Rule 4 ).

Be sure to verify the scientific accuracy of your contributions; e.g., if you contributed data, it is your responsibility that the data are correct, or if you performed laboratory or data analyses, it is your responsibility that the analyses are correct. If an author is accused of scientific misconduct, there are likely to be consequences for all the coauthors. Although there are currently no clear rules for coauthor responsibility [ 29 ], be aware of your responsibility and find a balance between trust and control.

One of the final steps before submission of a multi-authored paper is for all coauthors to confirm that they have contributed to the paper, agree upon the final text, and support its submission. This final confirmation, initiated by the lead author, will ensure that all coauthors have considered their role in the work and can affirm contributions. It is important that you repeat the confirmation step each time the paper is revised and resubmitted. Set deadlines for the confirmation steps and make clear that coauthorship cannot be guaranteed if confirmations are not done.

When writing collaborative multi-authored papers, communication is more complex, and consensus can be more difficult to achieve. Our experience shows that structured approaches can help to promote optimal solutions and resolve problems around authorship as well as data ownership and curation. Clear structures are vital to establish a safe and positive environment that generates trust and confidence among the coauthors [ 14 ]. The latter is especially challenging when collaborating over large distances and not meeting face-to-face.

Since there is no single “right approach,” our rules can serve as a starting point that can be modified specifically to your own team and project needs. You should revisit these rules frequently and progressively adapt what works best for your team and the project.

We believe that the benefits of working in diverse groups outweigh the transaction costs of coordinating many people, resulting in greater diversity of approaches, novel scientific outputs, and ultimately better papers. If you bring curiosity, patience, and openness to team science projects and act with consideration and empathy, especially when writing, the experience will be fun, productive, and rewarding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Meredith Holgerson and Samantha Oliver for their input in the very beginning of this project. We thank the Global Lake Observatory Network (GLEON), which has provided a trustworthy and collaborative work environment.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 7. Bass BM, Avolio BJ. Improving Organizational Effectiveness Through Transformational Leadership. 1st ed. London: SAGE Publications; 1994.

- 8. Braun S, Peus C, Frey D, Knipfer K. Leadership in Academia: Individual and Collective Approaches to the Quest for Creativity and Innovation. In: Peus C, Braun S, Schyns B, editors. Leadership Lessons from Compelling Contexts: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2016. pp. 349–365.

- 24. Northcote Parkinson C. Parkinson’s Law: Or the Pursuit of Progress. 1st ed. London: John Murray; 1958.

- 25. Bennett LM, Gadlin H, Levine-Finley S. Collaboration & Team Science: A Field Guide. National Institutes of Health. August 2010. https://ccrod.cancer.gov/confluence/display/NIHOMBUD/Home . [cited 19 February 2018].

- 26. Covey SR. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. London: Simon & Schuster; 2004.

- 27. Meyer E. The Culture Map (INTL ED): Decoding How People Think, Lead, and Get Things Done Across Cultures. 1st ed. New York: PublicAffairs; 2016.

- 28. Kaner S. Facilitator’s guide to participatory decision-making. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2014.

- Publication Recognition

What is a Corresponding Author?

- 3 minute read

- 416.8K views

Table of Contents

Are you familiar with the terms “corresponding author” and “first author,” but you don’t know what they really mean? This is a common doubt, especially at the beginning of a researcher’s career, but easy to explain: fundamentally, a corresponding author takes the lead in the manuscript submission for publication process, whereas the first author is actually the one who did the research and wrote the manuscript.

The order of the authors can be arranged in whatever order suits the research group best, but submissions must be made by the corresponding author. It can also be the case that you don’t belong in a research group, and you want to publish your own paper independently, so you will probably be the corresponding author and first author at the same time.

Corresponding author meaning:

The corresponding author is the one individual who takes primary responsibility for communication with the journal during the manuscript submission, peer review, and publication process. Normally, he or she also ensures that all the journal’s administrative requirements, such as providing details of authorship, ethics committee approval, clinical trial registration documentation, and gathering conflict of interest forms and statements, are properly completed, although these duties may be delegated to one or more co-authors.

Generally, corresponding authors are senior researchers or group leaders with some – or a lot of experience – in the submission and publishing process of scientific research. They are someone who has not only contributed to the paper significantly but also has the ability to ensure that it goes through the publication process smoothly and successfully.

What is a corresponding author supposed to do?

A corresponding author is responsible for several critical aspects at each stage of a study’s dissemination – before and after publication.

If you are a corresponding author for the first time, take a look at these 6 simple tips that will help you succeed in this important task:

- Ensure that major deadlines are met

- Prepare a submission-ready manuscript

- Put together a submission package

- Get all author details correct

- Ensure ethical practices are followed

- Take the lead on open access

In short, the corresponding author is the one responsible for bringing research (and researchers) to the eyes of the public. To be successful, and because the researchers’ reputation is also at stake, corresponding authors always need to remember that a fine quality text is the first step to impress a team of peers or even a more refined audience. Elsevier’s team of language and translation professionals is always ready to perform text editing services that will provide the best possible material to go forward with a submission or/and a publication process confidently.

Who is the first author of a scientific paper?

The first author is usually the person who made the most significant intellectual contribution to the work. That includes designing the study, acquiring and analyzing data from experiments and writing the actual manuscript. As a first author, you will have to impress a vast group of players in the submission and publication processes. But, first of all, if you are in a research group, you will have to catch the corresponding author’s eye. The best way to give your work the attention it deserves, and the confidence you expect from your corresponding author, is to deliver a flawless manuscript, both in terms of scientific accuracy and grammar.

If you are not sure about the written quality of your manuscript, and you feel your career might depend on it, take full advantage of Elsevier’s professional text editing services. They can make a real difference in your work’s acceptance at each stage, before it comes out to the public.

Language Editing Services by Elsevier Author Services:

Through our Language Editing Services , we correct proofreading errors, and check for grammar and syntax to make sure your paper sounds natural and professional. We also make sure that editors and reviewers can understand the science behind your manuscript.

With more than a hundred years of experience in publishing, Elsevier is trusted by millions of authors around the world.

Check our video Elsevier Author Services – Language Editing to learn more about Author Services.

Find more about What is a corresponding author on Pinterest:

- Research Process

What is Journal Impact Factor?

What is a Good H-index?

You may also like.

How to Make a PowerPoint Presentation of Your Research Paper

How to Submit a Paper for Publication in a Journal

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Reaching out for scientific legacy: how to define authorship in academic publishing

- Published: 23 January 2016

- Volume 103 , article number 10 , ( 2016 )

Cite this article

- Sven Thatje 1

4279 Accesses

17 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Scientists devote their careers to the search for new discoveries, which turn into public knowledge once published as a scientific article or as an academic book. This exciting curiosity-driven search for knowledge enthuses most scientists and often occupies an exceptionally large part of a scientist’s life. There are now many ways of publicising scientific discoveries, ranging from the print media to electronic publishing such as video documentary or voice podcast, all of which seek to preserve knowledge beyond human lifetime. Still, the principal way of preserving scientific discoveries for the future is the scientific article published in peer-reviewed a scientific journal (Kronick, 1990 ; Riisgård, 2000 ; Thatje, 2010 ). For the sake of this essay, I will hereafter refer to the peer reviewed scientific article as the “paper”.

What is a scientific legacy? The reputation of a scientist is based on the quality of a paper bearing the scientist’s name and its impact on the respective subject area in which the paper is published. The number of papers—and their quality—published by a scientist helps building academic reputation and influences a peer’s professional career. Scientific legacy describes the circumstance when a scientist’s work and name remains recognised beyond lifetime if not for generations to come. It is often the body of many published works that is of legacy building nature. Consequently, a “name on a paper”, as such, contributes to a scientist’s potential to building legacy. Therefore, scientific legacy is about future generations of scientists recognising the contributions of their predecessors. A good, if not groundbreaking, paper influences a research area for many years to come if not decades, and a scientist’s dream is an idea-driven discovery, which governs academia well beyond human lifetime. In brief, authorship of an article declares ownership and is a claim of potential legacy.

We publish the results of research for various reasons: for the joy of it, to inform peers, for the advancement of science and society, as well as to build reputation and legacy. “Publish or perish” is another phrase governing a scientist’s life, and especially that of the young scientist; presenting a long list of scientific papers in most areas of research is mandatory and influences a scientist’s future as an academic or researcher.

Building reputation precedes leaving a legacy. We have seen a steep increase in publishing activities in recent decades, as science is an important driver of the developments of both economy and society. Most countries increasingly invest into a vast array of research reflecting on each country’s developmental state, which has led to the number of scientists increase globally. Many areas of research develop rapidly e.g. the medical sciences, leading to unprecedented advances benefitting society. As a result, scientists from many disciplines tend to publish more papers than ever before, the reasons for which are diverse. There are many types of scientific papers (e.g. raging from short Communications to Original article formats) and the list of authors on a paper tends to be longer than what it used to be in most areas of research. The single author paper is, overall, rather rare these days, and also because research has become widely inter-disciplinary.

In summary, scientists mainly contribute to papers as co-authors rather than be the lead author. The number of authors on a paper is often driven by the impact factor (or quality) of the journal in which the article is published. Journals that have a high impact factor, which is based on the mean number of citations each article received (Riisgård, 2000 ; Thatje, 2010 ), tend to have greater influence on directing a research area. Authorship of any such article is therefore more desirable.

Given the diverse nature surrounding the publication of research, it is of importance to periodically revisit the criteria that “justify names on papers”. Ownership of research outcomes and ideas is often at risk where e.g. academic hierarchy, funding pressure, and limited job security dominate the research environment. Here, I wish to share my very personal thoughts on this subject, which are the result of several years of experience as the editor of The Science of Nature as well as a published scientist. These “rules of thumb of publishing” may serve as guidance and for further discussion. They should be of use to any area of academia, such as for peers as well as to funding agencies and employers, and area of publishing, not only within the natural sciences.

Single author papers constitute a minor proportion to the body of published scholarly work today. The single author paper is the most desirable publication in most if not all areas of academia. The situation is getting more complicated where several peers contributed to publishable research, and consequently giving each author’s contribution justice can be rather difficult. However, a few simple and clear recommendations do apply when defining authorship.

All authors of a paper must be able to present the contents of this research in detail. This should be of the quality of an oral presentation (talk) given at a science conference or as in a postgraduate (e.g. PhD) viva. This involves the discussion of content-related questions or within a public context such as media enquiries.

There are four types of authorship; the principal, also known as the first or lead author, the co-author, the senior author, and the communicating author. The most desirable position is that of the lead author, the principal authority with overall responsibility for the paper. The lead author wrote most if not all of the paper, with contributions from the co-authors. In most cases, the lead author is also responsible for managing and submitting the manuscript to the journal, including revision of the manuscript following peer review. The lead author is the main driver behind the piece of research including generating the idea(s), planning and conducting the research, analyses, and the write-up of the study for publication. The lead author certainly must be the originator of the idea, unless the idea was presented by the senior author, e.g. when supervising a research student. In many cases, the lead author also takes the position of the communicating author, to whom any paper related correspondence should be sent to. Alternatively, the communicating author is often found associated with the senior author (and is then identified as the same) and the senior author, if present, is then found in last position in a list of authors. The exact position of the senior author however, may vary and according to science culture of respective country and or case-by-case, and as indicated. The senior author often is a head of lab or research group or research grant lead or a principal PhD supervisor. However, the principal criteria of authorship, as outlined earlier, do also apply for the senior authorship. Where there are two peers authoring a paper, it is generally assumed that both peers contributed equally to any aspect of the paper or represent student and supervisor/senior author.

Difficulties in justifying an authorship arise when there are more than two authors; papers with approximately one to three authors tend to be easy to deal with; this can be the case of collaboration of established peers or rather often these days, a postgraduate student as lead and the involved (co)-supervisors as co-authors. In such case, the authorship to each peer’s build of reputation is rather obvious. Justifying the position of a co-author’s name in a long list of authors can be much more difficult. Papers with 5 to 10 or even up to 50 authors (or more!) are not uncommon these days. Such “consortia” or “community” papers do often reflect on the type of science involved, e.g. the use of large infrastructure and consortia-funded research or the increased need for multi-disciplinary approaches. Valuing differences in any co-author’s contribution in such case of multi-authorship is largely impossible. However, identifying the lead and the senior as well as communicating authors is of priority. Further, indistinguishable contributions of co-authorship are often made clear by listing peers’ names in alphabetical order. Where equal contributions of authors apply, a footnote can be placed. This can be important in case where two PhD students or early career scientists are disadvantages by not figuring both as the lead author and despite having contributed equally to joint research.

There is no doubt that the average number of “names on papers” has increased in recent years. As stated before, there are numerous reasons justifying this development. However, the basic criteria of authorship do always apply! Again, longer lists of authors automatically imply that the contribution of each co-author is close to being indistinguishable. Where there are more important contributions of the individual co-author to be underlined, the alphabetical order of listing authors may be abandoned, and a numerical order, and according to significance in contribution, may be preferred. Peer pressure can be high when developing a list of authors. Especially early career scientists can feel pressurised to succeed in their professional careers.

I have personally come under the impression that names on papers are not always justified. It is therefore desirable that scientists take clear responsibility for ideas and the resulting papers. Too often legacy is not built for those who deserve it but others who are demanding to be part of the publication; the responsibility for such development however is with all authors. Undoubtedly, funding research alone does not justify an authorship. Journal editors often favour longer lists of authors perhaps because such articles attract more (self)citations in the short run, positively affecting journal citation rates and therefore journal impact (Leimu and Koricheva 2005 , Engqvist and Frommen, 2008 ).

Personally, I would like to see a development toward an increased awareness of what an authorship really means, and how important it is for building reputation and legacy. Based on my experience, it appears to me that we have largely forgotten about the role of Acknowledgements in publishing. Today, these are mainly used to acknowledge funding sources and technical support. Sometimes, word counts and article layout restrictions do not even allow for any acknowledgements these days. Where the basic authorship criteria are not fulfilled, alternatively being recognised in a paper’s acknowledgements should again be seen as recognition and an indicator of a valuable contribution, which however, does not deserve authorship.

To conclude, the ways we publish and how we value authorships has changed in recent times. Re-visiting this defining issue is therefore desirable, and timely. It is the lead and senior authorships that stand out and build a scientist’s reputation. Such papers should be considered in particular when seeking to employ early (and late) career scientist. This collection of thoughts should provide guidance only and is not meant to be exhaustive. The definition of authorship, in most cases however, is straightforward and courtesy authorship must be avoided. It is up to us as scientists to show integrity and honesty when publishing, to self-govern and regulate through principles of fairness. In a world in which ‘publish or perish’ has become our motto, these values have been eroded, though they must be maintained.

Engqvist L, Frommen JG (2008) The h -index and self-citations. Trends Ecol Evolut 23:250–252

Article Google Scholar

Kronick DA (1990) Peer review in 18th-century scientific journalism. JAMA 263:1321–1329

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Leimu R, Koricheva J (2005) What determines the citation frequency of ecological papers? Trends Ecol Evolut 20:28–32

Riisgård HU (2000) The peer-review system: time for re-assessment? Mar Ecol Prog Ser 192:305–313

Thatje S (2010) The multiple faces of journal peer review. Naturwissenschaften 97:237–239

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Ocean and Earth Science, National Oceanography Centre, University of Southampton, European Way, Southampton, SO14 3ZH, UK

Sven Thatje

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sven Thatje .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Thatje, S. Reaching out for scientific legacy: how to define authorship in academic publishing. Sci Nat 103 , 10 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-016-1335-6

Download citation

Received : 14 January 2016

Accepted : 17 January 2016

Published : 23 January 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-016-1335-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Lead Author

- Scientific Legacy

- Building Reputation

- Funding Pressure

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

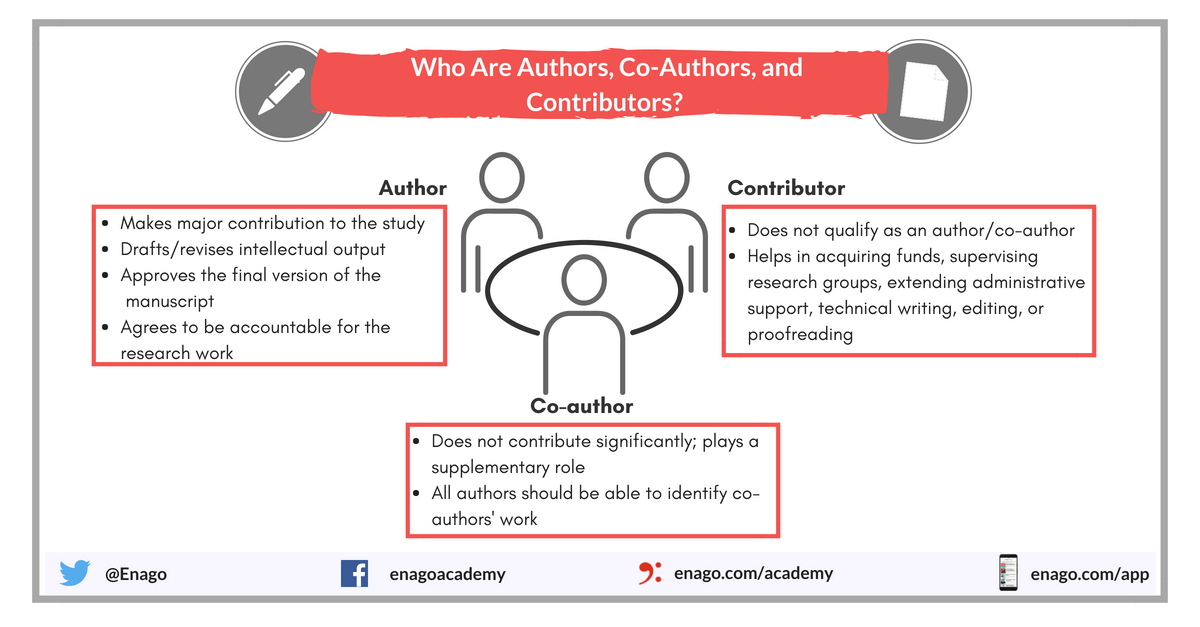

Authorship: Difference Between “Contributor” and “Co-Author”

With an increasing number of researchers and graduates chasing publication opportunities under the pressure of “ publish or perish ,” many are settling for participation in multiple author projects as the first step in building a track record of publications. Over time, the trend of multiple authorship has grown from 3–4 authors of a paper to 6 or more. As those numbers grow, the potential for confusion over responsibilities, accountabilities, and entitlements grows in parallel.

The term “multiple authorship” can be misleading, since the degree to which the workload is apportioned can depend on rank, experience, and expertise. Some participants will earn a place on the team solely on the basis of rank, with the hope that their presence will improve the team’s chances of getting accepted for publication in a prestigious journal. Others will be invited because they authored the original study design, provided the dataset for the study, or even provided the institutional research facilities.

Layers of Authorship

When there are only three or four members on a research paper team, the workload should be fairly easy to divide up, with a corresponding designation of one lead author and two or three co-authors . However, when the size of the team increases, a point is reached when co-authors become contributors. The perception of these titles can vary. New researchers who aspire to official authorship status may see the title of “contributor” as a relegation or demotion in rank, but for other, more experienced researchers, it may simply be a pragmatic recognition of the fact that you may have provided valuable resources but didn’t actually contribute to the writing or editing of the research paper.

Academic Misconduct

The danger in opening up another level of authorship is that journals are now given the opportunity to stuff papers with a few extra authors.

Related: Confused about assigning authorship to the right person? Check out this post on authorship now!

If the journal’s conduct has been flagged as being questionable to begin with—charging high article processing fees (APFs) for publication, delivering suspiciously short turnaround times for peer reviews—how far can they be from colluding with editors to add on a few contributors who had nothing to do with the research paper at all?

Contributorship Statements

As the development of larger research teams or collaborative authorship teams continues, the opportunities for new researchers to get published will hopefully increase too. However, the opportunity should never be looked upon as just getting your name added to the list of collaborators because being on that list comes with responsibilities. For example, if the peer review process flags problems with the data, who will be tasked with responding to that? If the reviewers request a partial re-write and re-submission , who will be tasked with delivering on those requests?

The larger the team, the greater the need for a detailed written agreement that allocates clear responsibilities both pre- and post-submission. This would fulfill two important tasks. First, everyone would know what is expected of them and what the consequences would be for not delivering on those expectations. Second, when the paper is accepted for publication, the agreement could be summarized as a contributorship statement , so that readers are given a clear picture of who did what. In addition, as this trend of multiple authorship continues, grant and tenure committees are starting to request clarification of publication claims, and such a statement would help to delineate precisely what you contributed to the paper.

Hello, How to cite the article of Authorship: Difference Between “Contributor” and “Co-Author”? Warm regards

Thank you for sharing your query on our website. Since we are not aware of the writing style format of the research paper concerned, we would suggest you to refer to the following website : https://www.citationmachine.net/apa/cite-a-website . Accordingly you can choose the style, add the article link and create the relevant citation format for the paper. Please note that proper acknowledgement and citation of the reference is necessary to avoid any issues of plagiarism.

Let us know in case of any other queries.

An impressive share! I’ve just forwarded this onto a coworker who was conducting a little research on this. And he in fact ordered me breakfast simply because I stumbled upon it for him… lol. So allow me to reword this…. Thanks for the meal!! But yeah, thanks for spending some time to talk about this issue here on your website.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

How Can Researchers Work Towards Equal Authorship

In the past, authorship lacked a clear set of guidelines and sometimes excluded individuals who…

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Insights into Assigning Authorship and Contributorship, and Open Access Publishing

ICMJE guidelines on authorship Avoiding authorship dilemma Overview of Open Knowledge Significance of open data…

- Publishing Research

- Understanding Ethics

Should First Authors Be Responsible for Scientific Misconduct?

You can also listen to this article as an audio recording. Scientific misconduct is a…

- Global Japanese Webinars

誰を論文の著者や貢献者とするか ― 研究者のためのオーサーシップ基礎知識

著者と貢献者の違い 何人まで著者として記載できるか 責任著者および共著者となれる条件 著者のためのリソース

学术作者和贡献者署名要怎么写

ICMJE 准则 谁有资格被列为作者 作者名单应该要多长 共同作者与第一作者

What You Must Know While Assigning Authorship to Your Manuscript

Authorship and Contributorship in Scientific Publications

Experts’ Take: Giving Proper Credit in Multi-authored Publications

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Plast Surg

- v.43(2); Jul-Dec 2010

Authorship issue explained

Surajit bhattacharya.

Editor, IJPS E-mail: ni.oc.oohay@hbtijarus

When it comes to the fact that who should be an author and who should not be offered ghost authorship, it seem we are all in agreement.[ 1 ] Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take responsibility for the content. Authorship credit should be based only on substantial contributions to (a) conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of data; and to (b) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and on (c) final revision of the version to be published. Conditions (a), (b), and (c) must all are met.

However, when it comes to the sequence of authorship there seems to be a grey zone and exploitation at both ends of the spectrum. We have come across aggrieved Unit Chiefs and displeased residents in almost equal numbers. It is important for young authors to understand that there are two positions that count, the first author and the last author. Attached to either position is the status associated with being the author for correspondence. The best combination when one is young is to be first author and the author for correspondence. As one’s career progresses, being last author and author for correspondence signals that this is a paper from one’s Unit, he/she is the main person responsible for its contents, and a younger colleague has made major contributions to the paper, hence he/she is designated as the first author. The guidelines here are not as well defined as for authorship in general, Riesenberg and Lundberg[ 2 ] have made certain very important and simple suggestions to decide the sequence of authorship:

- The first author should be that person who contributed most to the work, including writing of the manuscript

- The sequence of authors should be determined by the relative overall contributions to the manuscript.

- It is common practice to have the senior author appear last, sometimes regardless of his or her contribution. The senior author, like all other authors, should meet all criteria for authorship.

- The senior author sometimes takes responsibility for writing the paper, especially when the research student has not yet learned the skills of scientific writing. The senior author then becomes the corresponding author, but should the student be the first author? Some supervisors put their students first, others put their own names first. Perhaps it should be decided on the absolute amount of time spent on the project by the student (in getting the data) and the supervisor (in providing help and in writing the paper). Or perhaps the supervisor should be satisfied with being corresponding author, regardless of time committed to the project.

- A sensible policy adopted by many supervisors is to give the student a fixed period of time (say 12 months) to write the first draft of the paper. If the student does not deliver, the supervisor may then write the paper and put her or his own name first.

The second issue raised in this letter is about the use of plurals. Our insistence of avoiding pronouns I, me and mine in all publications is very sound and logical. Even if it is a single author paper, surgery is a team game and we are virtually powerless without our unsung colleagues - residents, nurses, technicians etc. By using plurals we recognize their vital role in our success story. Where as in a multiple author paper, the author has no option but to call it ‘our work’ instead on ‘my paper’, even when he is writing the paper all by himself / herself, there were many hands helping him / her and it is our Journal policy to acknowledge the same.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 28 May 2024

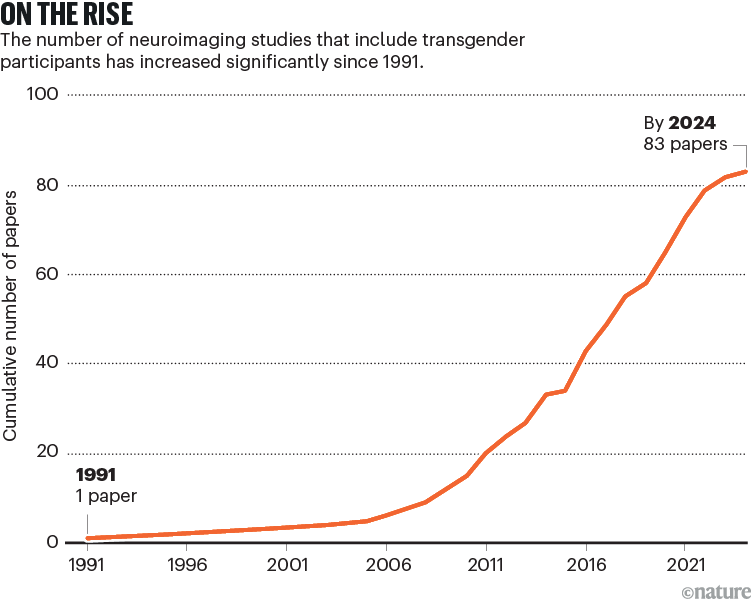

Heed lessons from past studies involving transgender people: first, do no harm

- Mathilde Kennis 0 ,

- Robin Staicu 1 ,

- Marieke Dewitte 2 ,

- Guy T’Sjoen 3 ,

- Alexander T. Sack 4 &

- Felix Duecker 5

Mathilde Kennis is a researcher in cognitive neuroscience and clinical psychological science at Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Robin Staicu is a neuroscientist and specialist in diversity, equity and inclusion at Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

Marieke Dewitte is a sexologist and assistant professor in clinical psychological science at Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

Guy T’Sjoen is a clinical endocrinologist and professor in endocrinology at Ghent University Hospital, Belgium, the medical coordinator of the Centre for Sexology and Gender at Ghent University Hospital, and one of the founders of the European Professional Association for Transgender Health.

Alexander T. Sack is a professor in cognitive neuroscience at Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

Felix Duecker is an assistant professor in cognitive neuroscience at Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

You have full access to this article via your institution.