- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

Worldbuilding Basics: A Beginner's Guide to Creating a Fictional World

Hannah Yang

Some imaginary worlds are so detailed and immersive that they almost feel as real as our own.

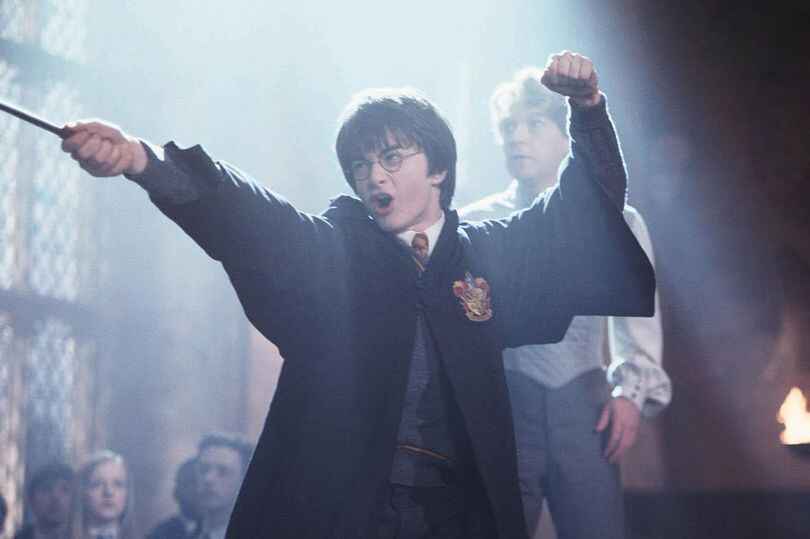

In our mind’s eyes, we’ve dined with hobbits in Middle Earth, attended magic classes at Hogwarts, and fought villains in the Marvel Universe.

What did those authors do to make their imaginary worlds so compelling? And how do you build a detailed world like that for your own story?

Read on to learn how to create a unique fictional world that your readers can get lost in.

Learn How to Build Awe-Inspiring Worlds at Fantasy Writers' Week

- Four free days of live events , just for fantasy writers

- Write, plan, and learn with us live with workshops, write-ins, and interviews

- Hear from bestselling authors and educators like V.E. Schwab and Tomi Adeyemi

On to the article!

What Is Worldbuilding in a Story?

What are the different types of worldbuilding, worldbuilding brainstorming techniques, what are the key elements of worldbuilding, what are some common worldbuilding mistakes, examples of great worldbuilding in fantasy and science fiction.

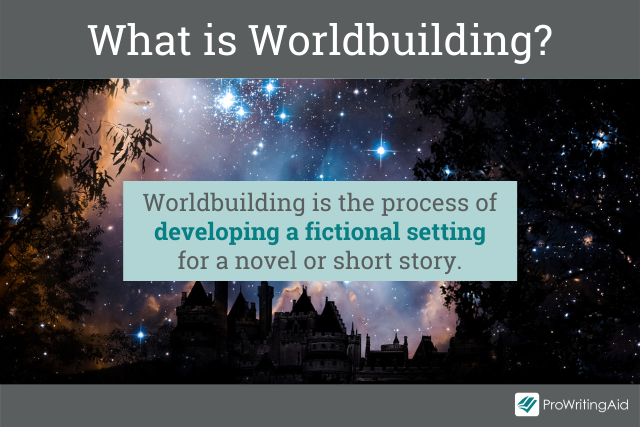

Worldbuilding is the process of developing a fictional setting for a novel or short story.

Every fiction writer will need to do some amount of worldbuilding , whether they need to invent a single apartment or an all-encompassing multiverse.

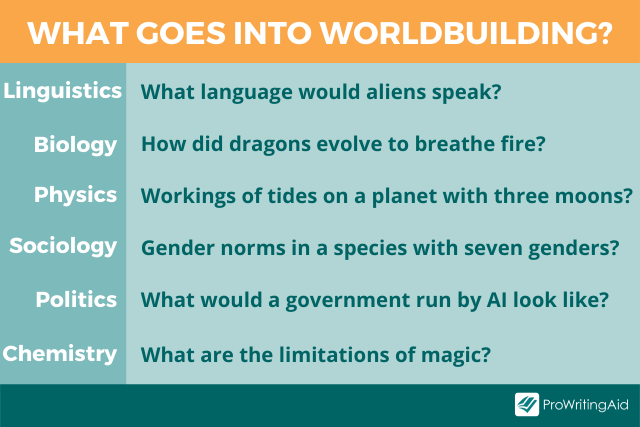

If you write fantasy or science fiction, worldbuilding can be incredibly complex. You might need to develop the history of dragons, the linguistics of a whole new language, or even new laws of physics.

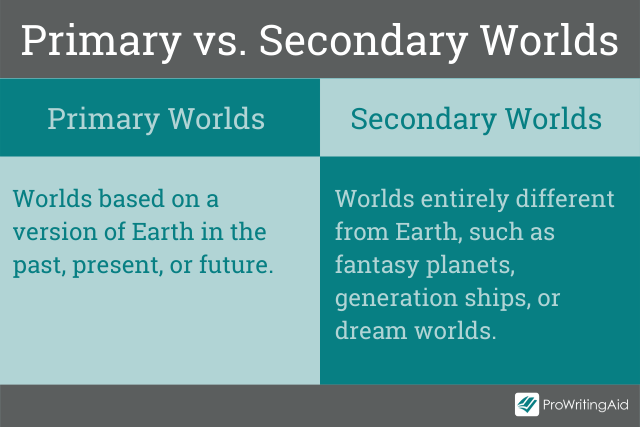

There are two types of worldbuilding: primary world and secondary world .

Primary worlds are worlds similar to some version of the real world, while secondary worlds aren't set on Earth at all.

Primary world worldbuilding is necessary for stories that are set in a slightly different version of the Earth we know.

You’ll need to build a primary world if you write in the following sub-genres:

- Contemporary fantasy , which is fantasy set in the present day (e.g. Harry Potter by J.K. Rowling, The Magicians by Lev Grossman, American Gods by Neil Gaiman)

- Alternate histories , which explores what might have happened if historical events had differed from what happened in reality (e.g. The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick, United States of Japan by Peter Tieryas, The Calculating Stars by Mary Robinette Kowal)

- Apocalyptic science fiction , which describe cataclysmic events that end society as we know it (e.g. The Road by Cormac McCarthy, Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel, Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood)

- Any other story set on a version of Earth

Secondary world worldbuilding is necessary for stories that are set on an entirely different planet from the real world, or maybe even something that’s not a planet at all.

You’ll need to build a secondary world if you write in the following sub-genres:

- Epic fantasy , which is set in an entirely fictional fantasy world (e.g. The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien, A Game of Thrones by George R.R. Martin, A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula K. LeGuin)

- Space empire/space opera science fiction , which span multiple planets or even multiple galaxies (e.g. Star Wars , Star Trek , A Memory Called Empire by Arkady Martine)

- Portal fantasy , where characters in the real world get transported to fictional worlds (e.g. The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, The Ten Thousand Doors of January by Alix E. Harrow)

- Any other story set on a world completely different from Earth

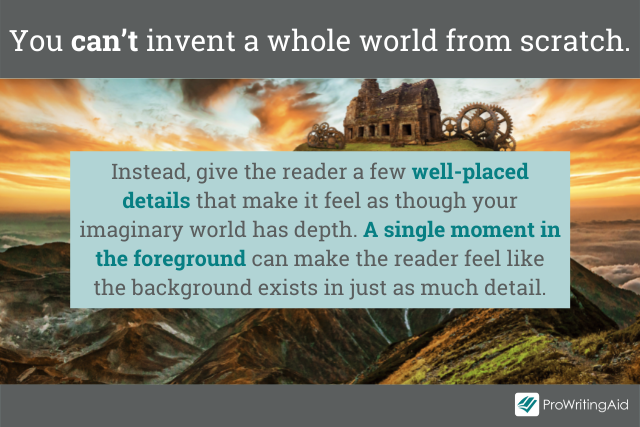

The secret to good worldbuilding is to make it feel like there’s a whole world you’ve developed, even if you only show a few details of it.

You can’t actually invent a whole world from scratch, of course—that would take centuries to accomplish—but you can give the reader a few well-placed details that make it feel as though this world has a lot of depth.

Picture a high-definition photo with a blurry background. A single very real moment in the foreground can make the reader feel like the background exists in just as much detail, even if the background is just a set of smudges.

One useful tip is to start from a single important change and see how many effects that makes on the world. Let’s call this change the Seed.

For example, say your story is set on a world exactly like ours, except people have always been able to fly. That's the Seed for their world. How many effects could that lead to?

Here are some possible effects that could sprout from that Seed alone:

- Instead of the swearwords we use, their swearwords might relate to flight and/or falling

- People might build floating societies, where the upper-class literally lives at the top and the lower-class literally lives at the bottom

- Children might look forward to a rite of passage in which they take their first solo flight, the way children look forward to getting their driver’s license in our world

Starting with a single Seed is often more effective than coming up with a thousand different ideas and trying to merge them together into a cohesive whole.

When you start from one source, everything holds together logically, and it feels like there’s a lot of depth to your world even if you haven’t fully fleshed it out.

Once you’ve decided on your Seed, there are countless types of effects you can consider. I’ve compiled some of the most important ones into a list of questions.

Here’s a list of detailed elements that you can use to brainstorm your fantasy or science fiction world.

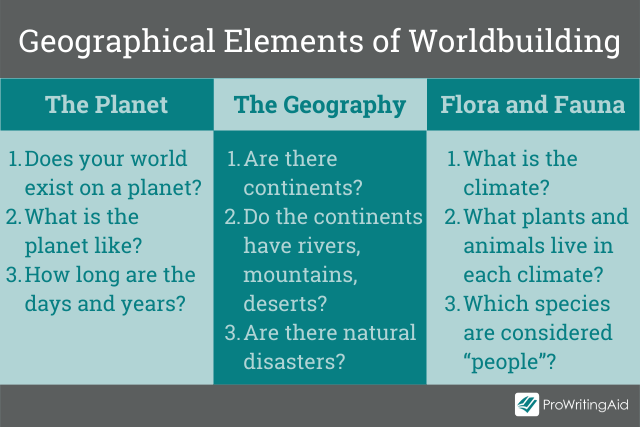

Geographical Elements

If you’re building a secondary world, you can start with the planet itself. This is a piece that many fantasy writers often skip, but it has so much potential in the fantasy genre.

Setting your story on a different planet—or not on a planet at all—leads to all kinds of interesting effects.

- Does your world exist on a planet at all, or is it somewhere else (e.g. a spaceship, a flat disc, an astral plane)?

- If you have a planet, how big is the planet? How strong is its gravity?

- How long are the days in your world? The years?

The Geography

- Are there continents on this planet? What do they look like?

- Do the continents have rivers, mountains, deserts? (Tip: It can help to draw a tectonic map , to see where these structures would naturally occur)

- Are there natural disasters on this planet?

The Flora and Fauna

- What kinds of climates exist on this planet?

- What kinds of plants and animals live in each climate?

- Which species in your world are considered “people”? Are there talking plants, sentient spaceships, etc.?

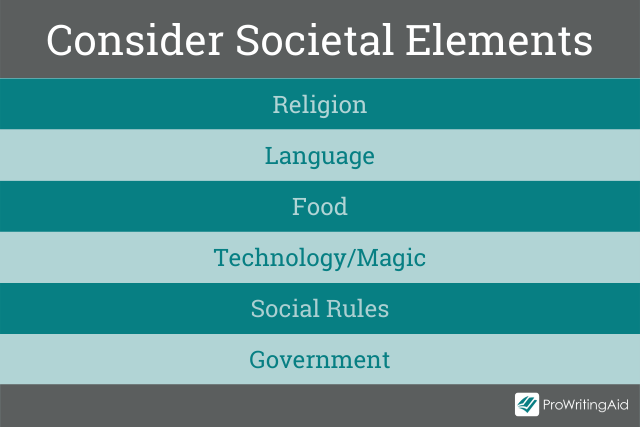

Societal Elements

Whether you’re building a primary world or a secondary world, there will likely be elements of your fictional societies that are different from the real world.

Building a new society and culture is one of the most exciting parts of worldbuilding.

If your book spans more than one society, you’ll want to do this for each group of people that the readers will meet.

- What do they eat? Do different social classes eat different things?

- Where does their food come from? Who grows it?

- How many meals do they eat each day? What are their dining customs?

- What does their language sound like (or look like, or taste like, or smell like)?

- What names do they have? Are their names based on real words? Does everyone have one name, or a first name and a family name, or something else entirely?

- What kind of slang and swearwords do they use?

- Who do they live with? (e.g. friends, parents, spouses, business partners)

- Is there marriage in this society? Who decides each individual’s marital partner(s)?

- How does reproduction and parenthood work?

- What kind of currency do they use?

- What natural resources are considered valuable? Why?

- What kind of economic system do they have? Is it capitalist, communist, socialist, or something else entirely?

Social Roles

- How many genders are there? What are the different roles each gender is expected to play?

- How much social inequality is there?

- How much social mobility is there? Can a lower-class person join the upper classes by acquiring money, education, or some other resource?

- Who holds power in this society?

- Who decides who holds power in this society? Is it a democracy, a monarchy, an oligarchy, or something else entirely?

- Are there any threats to this balance of power?

- Are there gods in this world ? Do they interact with people?

- What kind of religious practices or rituals does this society have?

- What are the creation stories of this society? How do they believe they came here?

Technology / Magic

- What machines and tools do these people use?

- Can people wield magic? How does the magic system work?

- Who has access to these machines, tools, and magic? Can everyone use them or are they restricted in some way?

There are several mistakes that many beginner fantasy and science fiction writers make. I personally have been guilty of all of these at some point in my writing journey.

Of course, none of these “don’t”s are set in stone—if you really want to do one of these things, there are ways to pull them off well.

But as a general rule, these mistakes tend to hurt your story more than they help it.

Mistake #1: Borrowing an existing fantasy world, instead of creating something new.

There are countless fantasy worlds that are just rehashed versions of The Lord of the Rings , complete with J.R.R. Tolkien’s vision of elves, orcs, and dwarves.

You might be thinking, The Lord of the Rings was amazing, so what’s wrong with reusing it?

Well, for one thing, it’s a wasted opportunity. You could come up with a creative and original world that would make your story stand out from the crowd.

Also, copying existing fantasy worlds also means that your story will come inherent with the perspectives those authors had.

For example, J.R.R. Tolkien’s fantasy species reflect some of the racial prejudices of his time, which are prejudices you might not want to perpetuate.

Unless you build your own fictional world, you will never be able to imbue it with your own authentic perspective and fresh ideas.

It’s okay to take inspiration from other authors’ worlds, but you should always find a way to make it your own, instead of copying it outright .

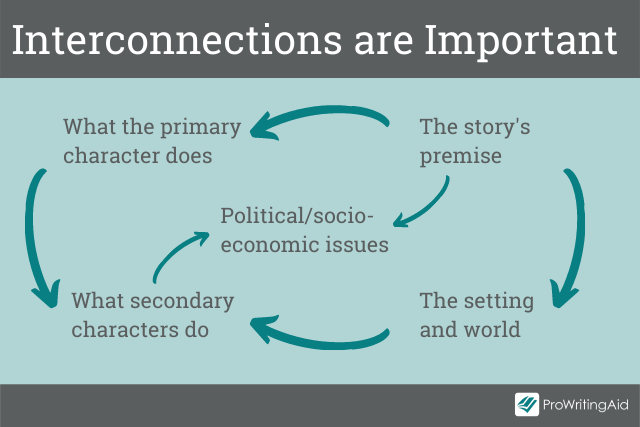

Mistake #2: Using disparate details that don’t belong together.

Maybe you have three unique ideas for a magical world: talking volcanoes, underwater dragons, and strong matriarchies. So you throw all three together into a single book.

But how do these three things interact with each other? What was the chain of cause-and-effect that led to them all existing in the same place?

Most of the time, readers will get confused when you throw too many disconnected details into your world, because you didn’t come up with a logical enough reason for all those things to coexist. Carefully consider how each thing affects everything else.

With worldbuilding, sometimes less is more. Considering interconnections before you add new elements will add so much logical cohesion and depth to your story.

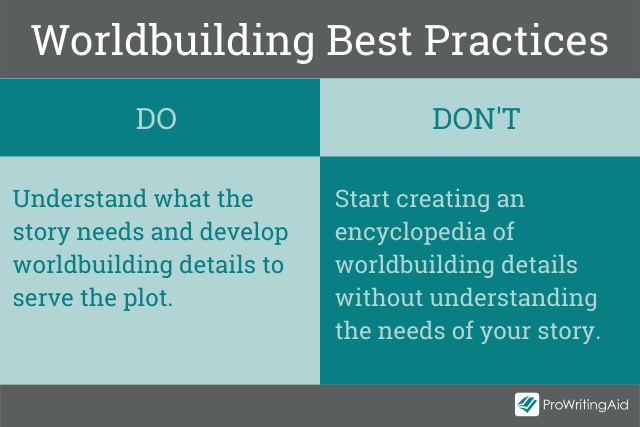

Mistake #3: Spending too much time on worldbuilding details that don’t serve the story.

At the end of the day, what makes a great novel is the story, not the setting.

Worldbuilding is a great servant, but a bad master.

If you’re twisting your story to suit the details of the world, rather than developing the details of the world to suit the story, you might want to shift your priorities.

Prioritize the details you develop based on what will matter to the plot and to the protagonist.

Don’t include a five-paragraph essay on the history of dragons in your world, no matter how interesting that history is, if none of that information has anything to do with the main plot.

Be ruthless when deciding what does and doesn’t belong in your novel.

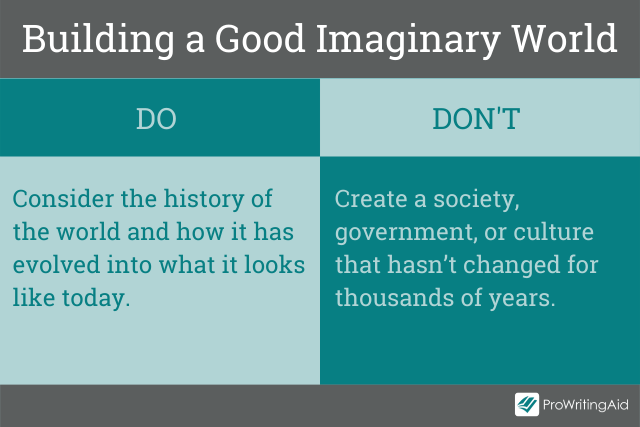

Mistake #4: Making your imaginary world too static.

How many science fiction worlds have you seen where a single regime has ruled for the past thousand years?

Everything is uniform, everything is static, and everyone is somehow happy with the way things are.

This is common in fiction, but impossible in the real word.

Look around at your neighborhood right now, wherever you live—or your city, or your country, or your planet—and think about how much your own world has changed in your lifetime.

A good fictional world should always be evolving. You should give some thought to your imaginary world’s history, not just what it looks like today.

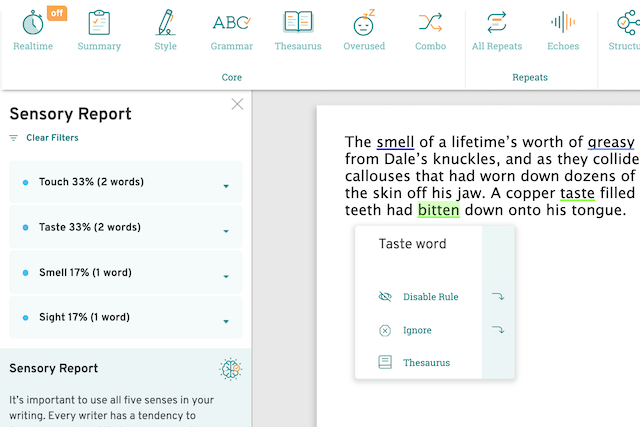

Mistake #5: Failing to consider all five senses.

People experience the world in different ways. Imagine yourself in a busy marketplace. You would simultaneously see the stalls, hear the chatter of the shoppers and calls of vendors, smell the food being cooked on a stall, and feel the heat of the day.

But if you only describe a setting using one sense, it can feel one-dimensional. Check that you have included a variety of sensory elements when describing your setting using ProWritingAid’s Sensory Report.

When you upload your writing ad run the report, it will give you a rundown of how many of each type of sensory word you have used so you can make sure you've got a balance.

Try the Sensory Report now with a free account.

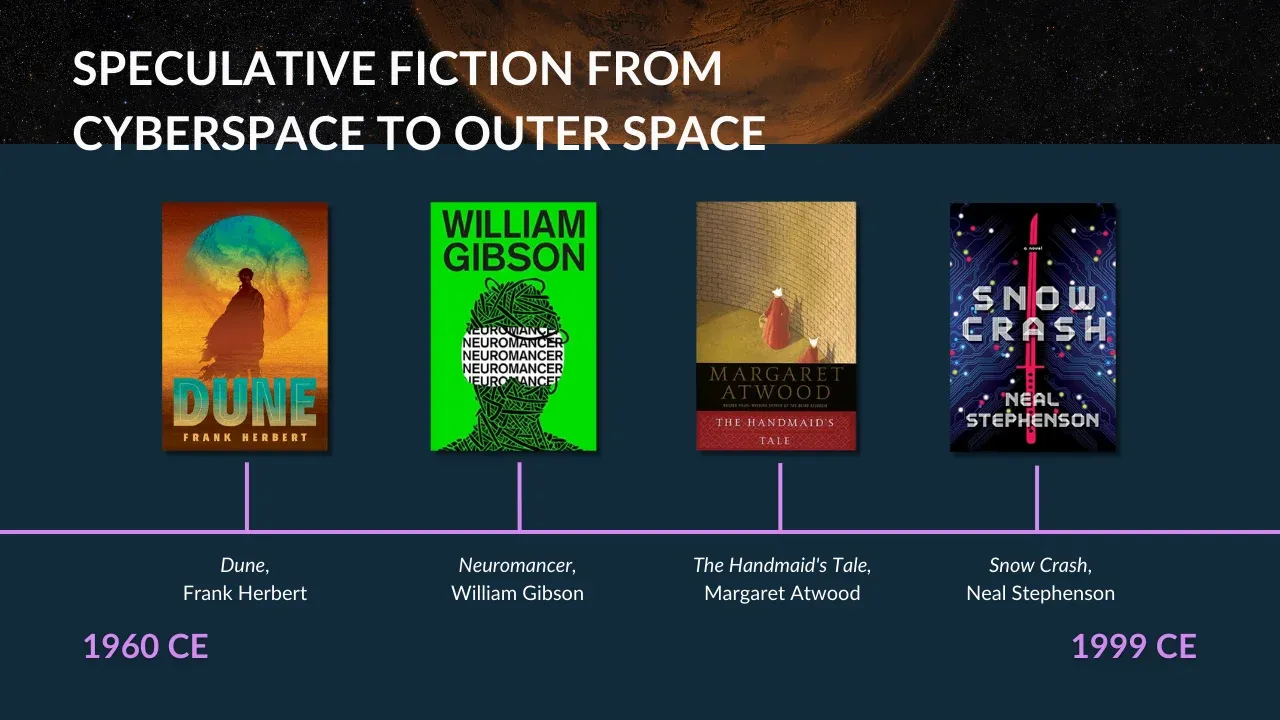

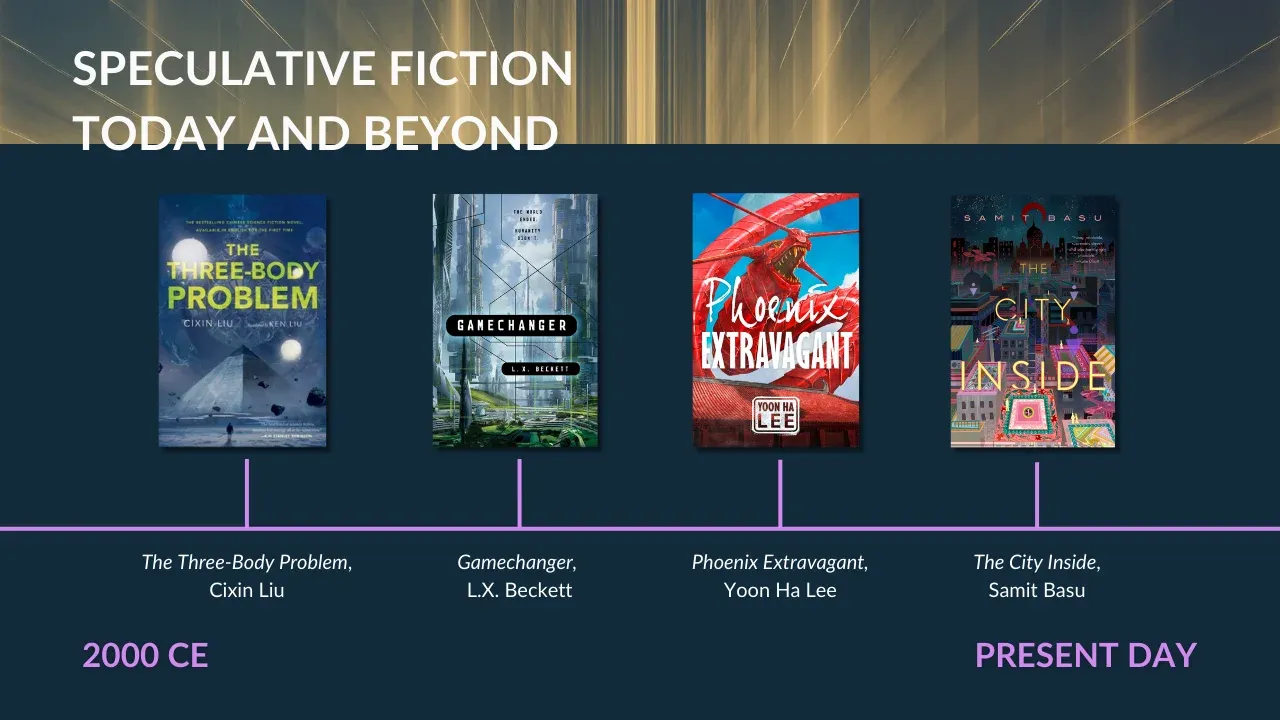

Now that we’ve talked about common mistakes to avoid, let’s look at some examples of worlds in literature that are fresh and unique.

Let’s look at some examples of fantastic worldbuilding from beloved fantasy and science fiction stories.

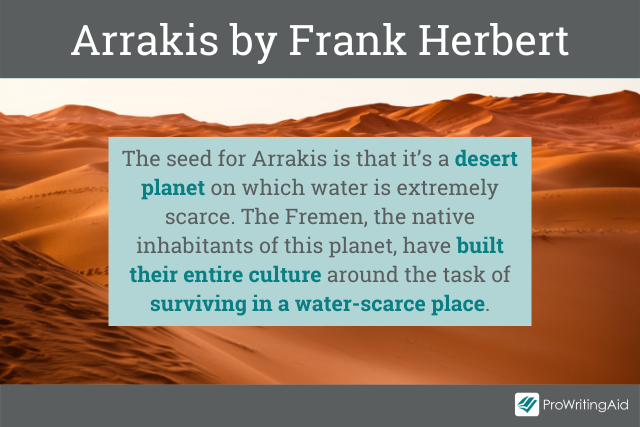

The Planet Arrakis in Dune by Frank Herbert

Dune is a classic masterclass in worldbuilding. The books are set on multiple planets, each of which feel like worlds of their own.

Frank Herbert was fascinated by ecology, and as a result, he did an incredible job developing the ecological details of his worlds.

The Seed for Arrakis is that it’s a desert planet, on which water is extremely scarce.

The Fremen, the native inhabitants of this planet, have built their entire culture around the task of surviving in a water-scarce place.

Some worldbuilding details that stem from this Seed:

- The Fremen wear stillsuits that collect and repurpose their bodies’ water so they can drink the liquid they sweat, urinate, and exhale.

- Instead of using coins, their currency takes the form of “water rings,” which represent their personal ownership of moisture, because water is more valuable than gold on this planet.

- In Fremen culture, spitting at someone is considered a sign of enormous generosity and respect, because of how valuable water is. This almost causes a deadly misunderstanding in one scene of the story, when an outsider from another planet assumes that being spit at is an insult.

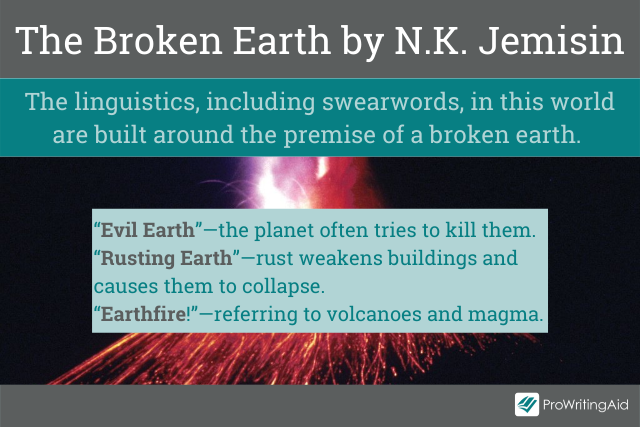

The Continent Called the Stillness in The Broken Earth Trilogy by N.K. Jemisin

The Broken Earth is one of the most intricate and unique worldbuilding systems in the fantasy genre.

The Seed for the Stillness is that the planet has a lot more tectonic activity than our planet does, with frequent earthquakes and tsunamis.

As a result, the people who live on the Stillness essentially live on a planet that keeps trying to kill them.

This is what caused their magic system and system of societal oppression to evolve.

- The sciences most valuable in the Stillness are fields like geomestry and biomestry, which combine the study of geology with other important fields of study to help scientists manage the tectonic activity.

- Orogenes, who have the magical ability of controlling the earth, are named after rocks (e.g. Syenite, Alabaster, Feldspar).

- Swearwords on the Stillness include “evil Earth” (since their planet often tries to kill them), “rusting Earth” (since rust weakens buildings and causes them to collapse in earthquakes) and “earthfire!” (which refers to volcanoes and magma).

The Republic of Gilead in The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

The Handmaid’s Tale is a classic dystopia. But while some dystopias come into existence just because evil people craved power, the Republic of Gilead came into existence to protect a single valuable resource.

This choice gives the story an incredible amount of logical cohesion and believability.

The Seed for Gilead is that female fertility rates have gone down drastically.

As a result, fertile women are considered the most valuable resource, and women are subjugated under a totalitarian theocracy.

- Women are assigned societal functions (Wives, Marthas, Aunts, or Handmaids) and must dress in the assigned colors of their role.

- Handmaids are named after the men they serve. The main characters include Offred who serves Fred, Ofglen who serves Glen, and Ofwarren who serves Warren.

- The far-right movement that created the Republic of Gilead is called the Sons of Jacob, a reference to the Biblical story of Jacob and Rachel, which was the inspiration for the role played by the Handmaids

Build An Immersive Fantasy World

And there you have it: a comprehensive guide to building your own fantasy world.

If you enjoy making maps and timelines, I highly recommend trying World Anvil , which offers a variety of free worldbuilding tools .

What element of worldbuilding is your favorite to brainstorm? Have you come up with any creative details for your own fantasy worlds?

Let us know in the comments.

If you love writing fantasy, this is the event for you.

- Learn from bestselling authors and educators in live sessions

- Master outlining, writing, editing, publishing and more

- Meet like-minded fantasy writers in networking events

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

A Step-by-Step Guide to Immersive World Building

A book like A Game of Thrones , a movie like Star Wars, or even a video game like Final Fantasy can make it appear their creators have effortlessly built a fantasy world out of nothing.

In fact, these worlds may feel as real as the world you live in.

How do they do it? More importantly, how can you do it?

More than two-thirds of my 200 books are novels, but creating fictional worlds never seems to get easier.

It’s an art, and in genres such as Fantasy or Science Fiction, world building is more important than ever. It can make or break your story .

In this guide, I’ll give you tips to follow and errors to avoid. But first…

- What is World Building?

Writing a story is much like building a house — you can have all the right ideas, materials, and tools, but if your foundation isn’t solid, not even the most beautiful structure will stand.

World building is how you create that foundation — the Where of your story.

World building involves more than just the setting . It can be as complex as a unique venue with exotic creatures, rich political histories, and even new religions. Or it can be as simple as tweaking the history of the world we live in.

Go as big as you want, but remember: world building is serious business.

Create a world in which readers can lose themselves.

Do this well and they become not just fans, but also fanatics. Like those who obsess over:

- Harry Potter

- A Game of Thrones

- The Marvel Universe

Each approaches world building in a different way:

1. Real-World Fantasy

Here you set your story in the world we live in, but your plot is either based on a real event (as in Outlander ) or is one in which historical events occur differently (for instance, had Germany won World War 2).

In Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle , he imagines a world in which Franklin Roosevelt was assassinated in the early 1930s.

2. Second-World Fantasy

Here you create new lands, species, and government. You also invent a world rich in its own history, geography, and purpose.

Examples include:

- The Lord of the Rings

Some novels combine the Real World and Second World Fantasy. The Harry Potter series, for instance, is set in the world we live in but with rules and history foreign to us.

(The Chronicles of Narnia and Alice in Wonderland are also examples of this. )

Your job is to take readers on a journey so compelling they can’t help but keep reading to the very end.

- A World Building Guide

Step 1: Plan but Don’t Over-Plan

Outliners prefer to map out everything before they start writing.

Pantsers (those who write by the seat of their pants) write as a process of discovery — or, as Stephen King puts it, they “put interesting characters in difficult situations and write to find out what happens.”

Though I’m a Pantser, I can tell you that discovering a new world is a whole lot harder than building it before you get too deep into the writing.

Build your world first, then you can better focus on your story .

However, over-planning can also be a problem.

Many fantasy writers tell me they become so engrossed in world building that they find reasons not to write.

World building must not come at the expense of your story.

If you’re like me, you may have to spend more time planning than you’re used to.

If you’re an Outliner, draw a line in the sand and start writing as soon as you’re ready, even if you suspect you’ll have more spadework to do as you go.

Step 2: Describe Your World

Once you’ve determined your genre, paint for your reader a world that transports them, allowing them to see, smell, hear, and touch their surroundings. Show them, don’t tell them.

Which idea for this new world most excites you ? An other-worldly landscape? A new language? Strange creatures? Build on that to give you the momentum you need when the going gets tough.

- Climate / Environment

When James Cameron wrote the movie Avatar , he created countless reference books on Pandora’s vegetation and climate and even botany.

In Cormac McCarthy’s The Road , the main characters live in a post-apocalyptic world covered in ash and largely devoid of life. Their entire journey revolves around finding food and water and how to stay warm.

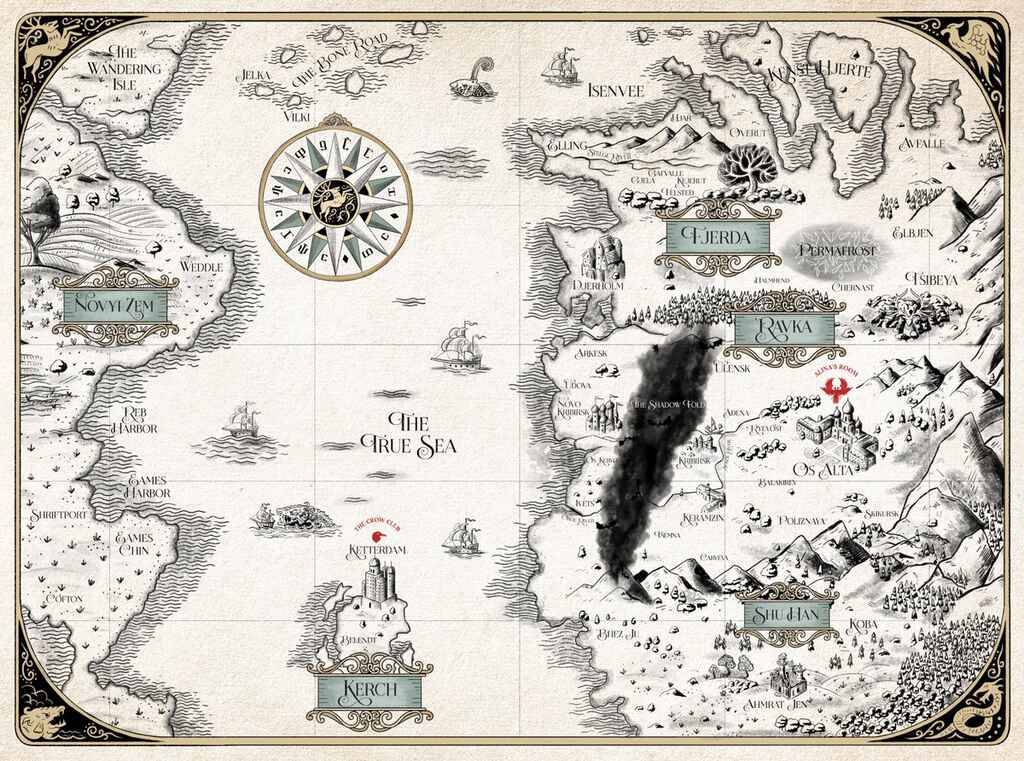

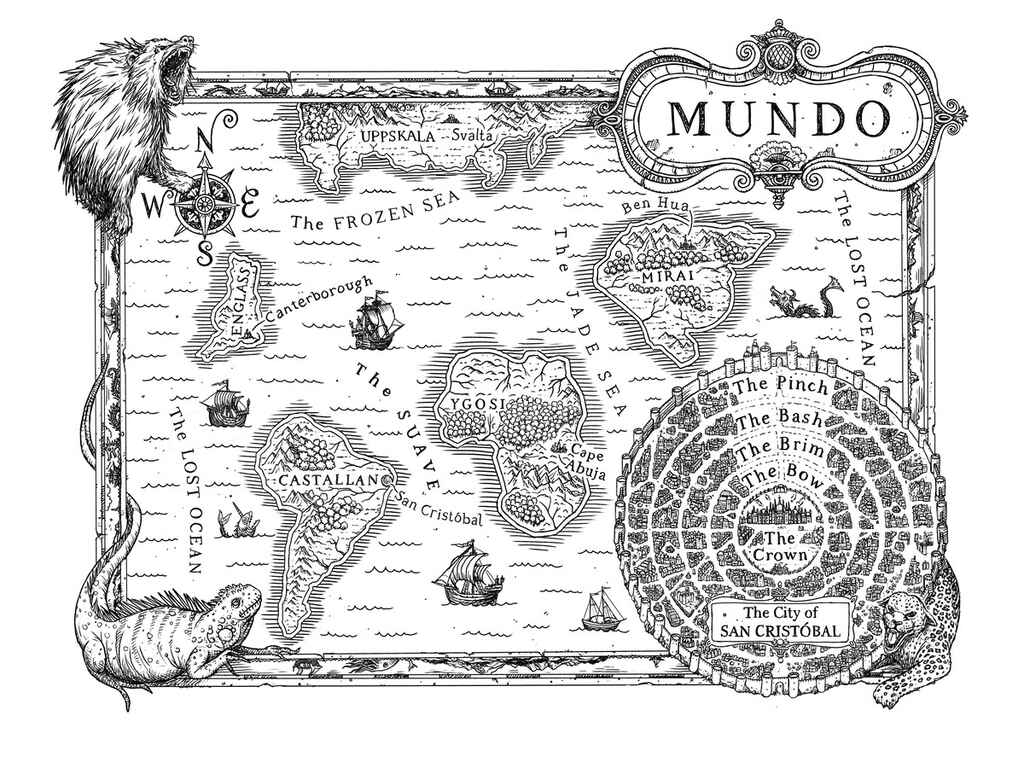

In A Game of Thrones , George R.R. Martin went as far as creating maps.

Other stories that feature maps:

- The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

- The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis

- Discworld by Terry Pratchett

- The Princess Bride by William Goldman

- Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

- Winnie the Pooh by A.A. Milne

- A Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin

World Building Questions:

- Was your world always the way it is now? If not, what was it like before and what caused the change?

- How much of your world do you need to show to support the story ?

- How does the terrain influence your story?

- What is the weather like and does it impact your story?

- How many mountains, oceans, deserts, forests?

- Where are the borders?

- What are the natural resources and how do they impact your story?

Be sure to focus on all five senses, not just seeing and hearing. Touch, taste, and smell will make your world feel real and familiar, even if it’s fantasy.

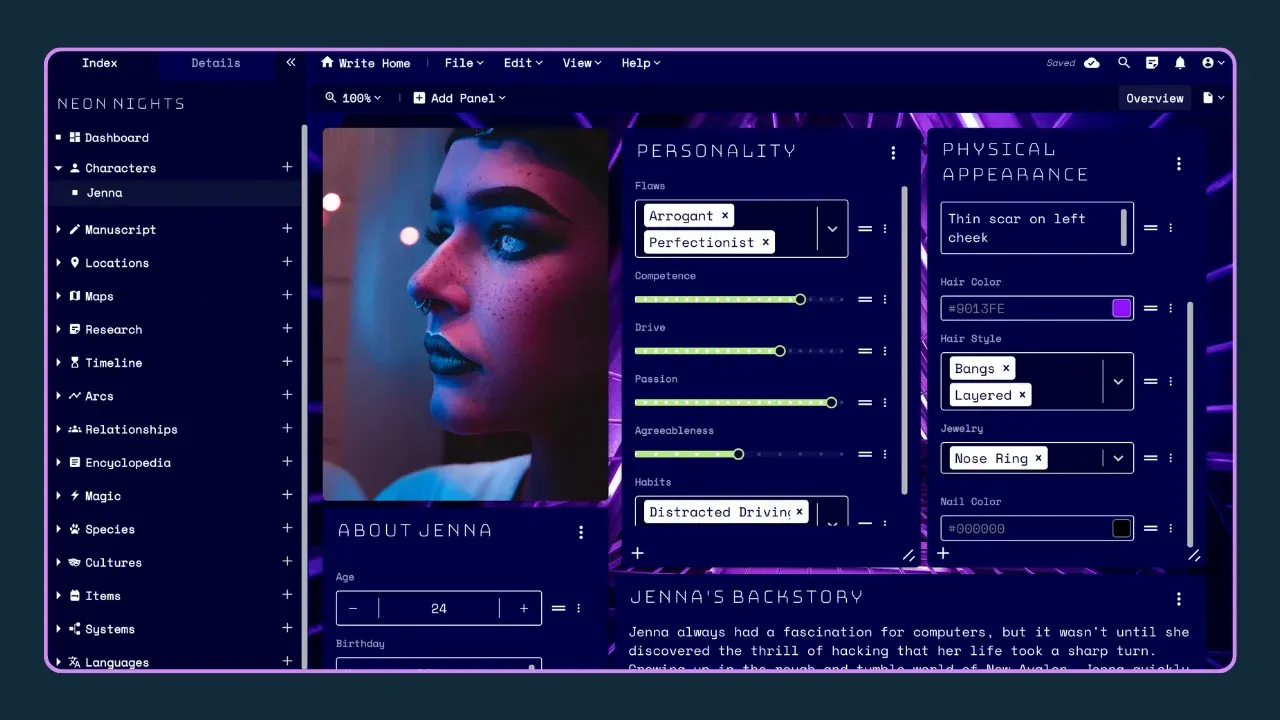

Step 3: Populate Your World

- Are the inhabitants people, but somehow different from you and me?

- Are they aliens, monsters, or some new species?

In The Lord of the Rings , Tolkien gave Frodo a past, personality traits, and morals. But he first determined what a hobbit looked like and how he lived.

World Building Character Questions:

- How big is their population (i.e., how big is your world)?

- How did they become part of your world ( their backstory )?

- Do they have a class system?

- What are the genders, races, and species?

- Does everyone speak the same language?

- How do they get along?

- Are there alliances?

- What resources do they enjoy?

- What resources do they lack?

Step 4: Establish the History of Your World

- The Lord of The Rings focuses on an ancient war .

- The Hunger Games is built on decades of oppression.

- The Divergent trilogy characters are unaware of what their world used to be like.

When world building, consider:

- The Deep Past : What happened to fuel the present economy, environment, culture, etc.

- Trauma : Wars, famines, plagues.

- Power Shifts : Political, religious, or technological.

- Who have been the major rulers?

- What took place during their reigns?

- Who are the enemies of your world?

Step 5: Determine the Culture of Your World

In Star Wars , for instance, religion (The Jedi vs. The Dark Side), societal structure (slaves and free), and politics (the trade wars) play huge roles.

- Is your world totalitarian, authoritarian, or democratic?

- Do your inhabitants speak a common language?

- How do your characters behave? Will they break the rules?

- Are the rules considered fair, or is society opposed to them?

- How are inhabitants punished?

- What is the religious belief system?

- What gods exist?

- How do religious rituals or customs manifest themselves?

- Is there conflict between religious groups?

- How do different social classes behave?

- What do they wear?

- How do families, marriages, and other relationships operate?

- How do inhabitants respond to love and loss?

- What behaviors are forbidden?

- How are gender roles defined?

- What defines their success and failure?

- What and how do they celebrate?

- Do they work?

Step 6: Power Your World

- Is your world energized by equipment or magic?

Equipment involves technology like Artificial Intelligence, space or time travel, or futuristic weaponry.

Or it could focus on simpler technology like swords, guns, or horses.

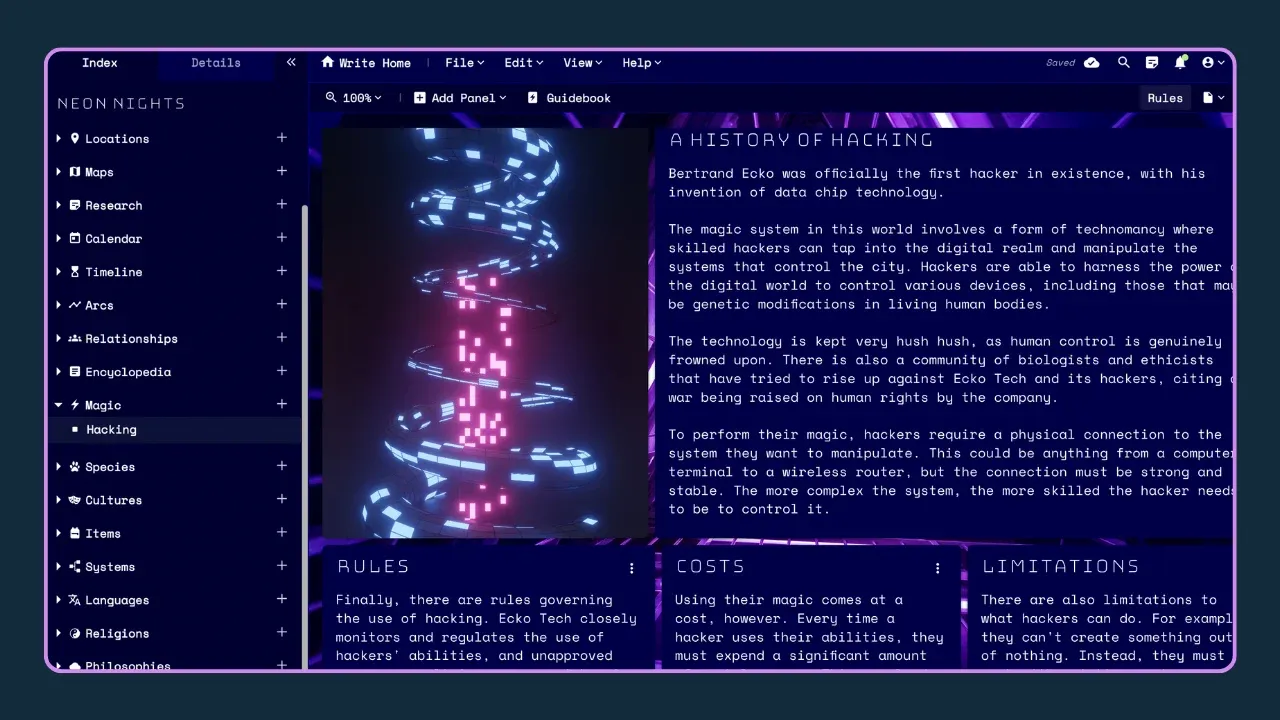

Magic allows you to take your worldbuilding to new realms.

In 2001: A Space Odyssey , Arthur C. Clarke explained how things worked and why, making it as realistic and factual as possible.

When writing his futuristic novels, Iain M. Banks referenced droids and spaceships but never explained how they worked.

The same applies to magic in your story.

You can either explain how it all works or simply focus on how it is used and why.

- Does magic exist in your world?

- How powerful is it?

- Where does it come from?

- How does it manifest itself?

- Can it be controlled?

- Who wields it?

- Can it be learned or are people born with it?

- Are wands or staffs, etc., needed?

- How does it affect the user?

- Do people fear it or embrace it, and what makes the difference?

- Is there good and evil magic?

- What other technologies do people use?

- Who controls it?

- How do they travel and communicate?

- How do they use these technologies day-to-day?

- Do they use technology for entertainment?

- Do governments use it to gain or maintain power?

In Fantastic Beasts , J.K. Rowling wrote a guide that focuses on how the magic works.

If magic or futuristic technology play roles in your world, consider doing the same.

It doesn’t have to be as detailed or as complete as Fantastic Beasts . So long as you have a resource that keeps all the rules in one place, you’ll keep your world (and the rules it lives by) consistent.

- Keep Your World Grounded

World building involves a lot of preparation. But it’s also easy to go overboard with the universe you create, especially if you’re an Outliner.

The excitement of creating and exploring your new universe should be accompanied by a commitment to believability.

That might sound strange when we’re talking about wholly made-up worlds born in our imaginations. But one of the reasons series like Star Wars, Harry Potter , and The Hunger Games garner so many devoted fans is because their worlds have been rendered in such a way that viewers and readers wholly buy in and see them as real places.

They’re relatable.

If you’ve come across the phrase “a willing suspension of disbelief,” you know it refers to a reader’s willingness to temporarily embrace the impossible—setting aside their natural skepticism. And for the most fun reading experience, despite knowing down deep what they’re reading is fantasy, they allow themselves to accept the premise.

So how do you convince your readers to believe in such things as space knights and wizard schools?

1. Be consistent

Always follow your own rules. If yours is a story in which monkeys fly, have them fly and treat this as normal.

As you build your world, reinforce the laws you create (religious, political, physical, etc.).

While these rules will not likely be the focal point of your novel, they should be prominent and accepted as normal throughout.

2. Draw inspiration from real-life

Real-life historical events, personal experiences, interesting natural phenomena, and ideological beliefs (such as ancient religions and philosophies) can inform your world building.

Whether you’re writing real-world fantasy, second-world fantasy, or a combination of both, stories from real life inspire compelling fiction.

As I discussed before, real-world fantasy is a story set in a world that closely resembles our own, often with familiar locations, cultures, and historical contexts. However, it incorporates fantastical elements, such as magic, mythical creatures, or supernatural phenomena.

- J.K. Rowling has said that many characters in the Harry Potter series were inspired by people from her real life including childhood friends and teachers. She was also influenced by myths and folklore around the world, including creatures such as basilisks, centaurs, and trolls.

- C.S. Lewis drew from his experiences opening his home to evacuee children during WW2 for the story of the Pevensie children in The Chronicles of Narnia .

Second-world fantasy , also known as high fantasy, is set in a completely invented or parallel world distinct from our own. The author creates the entire setting, including geography, cultures, languages, and magic systems. However, authors of these made-up worlds still draw inspiration from real life.

- J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth in The Lord of the Rings was greatly influenced by his study of Old English literature particularly the epic poem Beowulf .

- George R.R. Martin’s Westeros in A Song of Ice and Fire is loosely based on The War of the Roses fought in 15th-century England.

3. Prioritize your story over your world

Be very careful to make your plot even more interesting than your world. As fascinating and engaging as Harry Potter’s world is, the real music of the story is what happens—not simply where it happens.

If your world is populated with the most fascinating magical societies, mythical creatures, and mysterious histories, your fantasy fails if your characters are flat and your plot is predictable. While fictional worlds can intrigue readers, your other story elements must captivate them.

- Write Attention-Grabbing Fiction

No two writers will approach world building the same. Just be careful not to get so bogged down in world building that it keeps you from writing your story.

Have fun with it!

Write a story that keeps your readers riveted to the end.

Are You Making This #1 Amateur Writing Mistake?

Faith-Based Words and Phrases

What You and I Can Learn From Patricia Raybon

Before you go, be sure to grab my FREE guide:

How to Write a Book: Everything You Need to Know in 20 Steps

Just tell me where to send it:

Enter your email to instantly access my ultimate guide to writing a novel.

TRY OUR FREE APP

Write your book in Reedsy Studio. Try the beloved writing app for free today.

Craft your masterpiece in Reedsy Studio

Plan, write, edit, and format your book in our free app made for authors.

Blog • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Feb 03, 2023

Worldbuilding: Create Brave New Worlds [+Template]

Worldbuilding is the stage in the writing process where authors create believable settings for their stories. This may involve crafting a fictional world's history, geography, politics, and economy, as well as religions or powerstructures.

Since creating a fictional universe is a daunting task, you might want a bit of help. Here's how to worldbuild in 7 steps:

1. Define your world’s name and setting

2. create a map of the territory , 3. populate the world with people, 4. elaborate your civilization’s history, 5. create systems of technology and magic, 6. distribute resources with a working economy, 7. determine your world’s power structure.

We’ve also created a template to help you in your process, which you can download for free.

FREE RESOURCE

The Ultimate Worldbuilding Template

130 questions to help create a world readers want to visit again and again.

Broadly speaking, the setting of your story will either be our own world, or an entirely fictional world — what’s known as “second world” fantasy. Before you start work on your backstory, it’s essential to know which of these categories your story will fall under.

Create second worlds from scratch

George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire and Raymond E. Feist’s Riftwar cycle are classic examples of “second world” fantasy: they were able to create worlds untethered by historical paths or laws, which gave them a lot of freedom of choice.

This creative freedom is exciting, but it also requires a lot of world building work to invent a fleshed out and textured fantasy world. A strong starting point in order to define your world as “other” to our own is selecting your world’s name. You can make it as cool as you like; think Discworld, Middle Earth, Zamonia, etc.

Set your story in an Earth-like place

Not all fantasy writers, however, wish to create an entirely new world. You can always set your story right here on Earth. For example, the vast majority of literary fiction, mystery, and romance novels are set on a place called Earth that bears a striking resemblance to our own world. This kind of world creation may require less invention on behalf of the author, but may require just as much preparation as they are constrained by historical specifics, technology, and politics.

Within “real world” fantasy, however, you will see two broad subgenres : alternate history fantasy, and historical fantasy.

For historical fantasies, while some amount of historical license is accepted (and encouraged), your readers will notice something’s wrong if your book has Atilla the Hun kidnapping Florence Nightingale without the help of a time machine.

Alternate history fantasy gives you a little more freedom; as the name suggests, you’re inventing an alternate version of history. Still, you’ll want to think carefully about the changes you’re making, and the way they might impact the day-to-day life of your characters.

Once you’ve selected between first and second world settings, you can begin building it in earnest. This is where the fun really begins.

Watch: How to create your worldbuilding bible

Once you’ve named your world, it’s time to fill it. That means having at least a broad sense of its geography and ecology, so that you know what the landscape looks like, and what beasts your characters are likely to encounter.

You can consult our worldbuilding guide for a full list of prompts, but some questions to consider include:

- What sort of environment can be found in different areas of your world? (Deserts, oceans, mountains, forests, etc)

- What wildlife can be found there?

- What is the climate like?

- Where are the cities? How large are they? What are they called?

Take inspiration from real countries

You can draw from the real world when imagining these aspects of your fantasy world. For example, Leigh Bardugo’s Grishaverse takes inspiration from the geography of a number of real-world countries, often at another point in their national history. You can find analogs for Tsarist Russia, the Dutch Republic, China, and Scandinavia in Bardugo’s books.

As well as drawing from the past, another approach could be to imagine a future iteration of our world. NK Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy is a masterful example of speculative worldbuilding. The trilogy takes place on a supercontinent called the Stillness, which is wracked by massive climate events every few centuries which reshape the entire world’s geography. Colson Whitehead’s Zone One is set in the familiar but decimated remains of a future New York, a cityscape that has been devastated by a zombie apocalypse.

Maybe set your story in two different places

Another possibility is to create a dual setting, locating your narrative in part in our own physical world, and in part in another. Erin Morgensen’s The Starless Sea tackles this expertly, using the classic “magical door” trope to connect her real-world locations (Vermont and New York) with her fantastical world, the honey-filled Starless Sea and the magical harbors that sit upon it.

Imagine an entirely new environment

You may, of course, wish to create a landscape entirely alien from our own. Frank Herbert’s Dune is set on the desert planet of Arrakis, a world entirely devoid of natural water and inhospitable to most forms of life. Noteworthy exceptions to this are sandworms, giant and dangerous worm-like creatures that Fremen, the planet’s inhabitants, have learned to ride.

Lots of fantasy readers like referring to a physical map when imagining a world that is unlike our own. Maps are not always necessary, but they’re a useful foundation to define a sense of distance and space — and they can help you visualize your world as you’re building it.

Draw a map to help the reader

For a personal and expert approach, it's definitely worth hiring a professional illustrator to develop your fantasy map. Here at Reedsy, we have rigorously curated the best freelance illustrators in the publishing business — and they're just a click away from helping your work stand out.

Want to finish a novel in just 3 months? Sign up for our How to Write a Novel course.

NEW REEDSY COURSE

How to Write a Novel

Enroll in our course and become an author in three months.

Now that your physical landscape exists, let’s drop some people into it. To create a textured and believable setting, you’ll want to populate your planet with a variety of races and cultures — which can be either created, or based on real-world cultures.

You may wish to pull species from the rich traditions of high fantasy (elves, dwarves, trolls, etc), but you can also invent entirely new races. Our worldbuilding template will help you nail down the details of your inhabitants.

Be careful with tropes and stereotypes

Make sure to research thoroughly before settling on any attributes or characteristics for your characters. Even in the imagined worlds of fantasy and science fiction, harmful stereotypes can be perpetuated, especially when drawing on real-world cultures.

Some research is therefore required to ensure you are handling your source material in a respectful way, and to avoid retrograde stereotypes when portraying the characteristics of imagined races (including “classic” fantasy characters like dwarves, which have long been influenced by antisemitic tropes).

An example of real-world cultures informing fantasy cultures is the setting and characters of Children of Blood and Bone. Author Tomi Adeyemi draws on African mythology and her own Yoruba heritage , setting the story in a fictional version of pre-colonial Nigeria. Her imagined country, Orïsha, is inhabited by two peoples; the magical divîners with distinctive white hair, and their non-magical oppressors, the kosidán.

FREE COURSE

How to Develop Characters

In 10 days, learn to develop complex characters readers will love.

Invent an alien species

Of course, your characters don't need to be human. Octavia Butler’s Xenogensis series is an example of an invented non-human race. In the series’ first installment, Dawn, a human woman Lilith awakens alone in a prison cell, only to learn that she is one of the last survivors of the human race. She has been abducted by the Oankali, a humanoid but thoroughly alien three-gendered species covered in sensory tentacles. The differences between the humans and the Oankali, and the Oankali’s unusual biology and reproduction, form the driving force behind the novel’s plot.

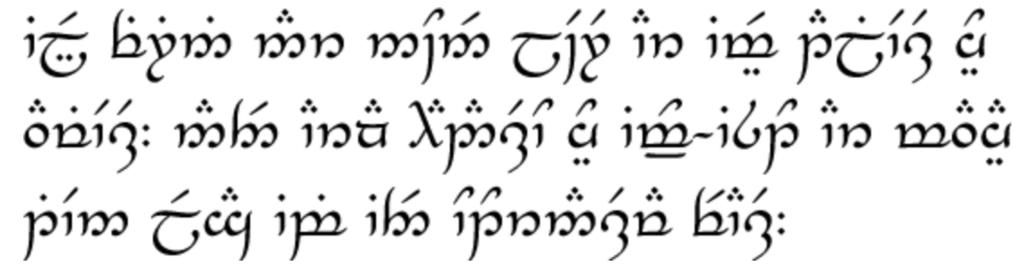

Come up with a new slang or language

When we talk about invented languages in fiction, most of us might imagine devotees of Tolkien whispering Elvish love poems — or Star Trek fans barking threats in Klingon. But language is something that applies to books across the board. Your decisions here will affect how the story develops and can make the difference in whether your book is believable.

Languages can be an interesting and exciting avenue of worldbuilding. The spoken word is a reflection of the cultures that spawned them, and the evolution of the language will often indicate some societal change.

For example, the youths in Anthony Burgess’ 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange speak a dialect called “Nadsat” which mixes Russian and English words. That choice alone implies a lot about the dystopian world of the book, suggesting a future where Soviet culture had spread further West.

Our worldbuilding guide will help you develop your ideas about language, but as a start, it's worth considering how many languages are spoken in your world, which language is most prevalent, and any common phrases or greetings which might come up a lot.

If your story is set on Earth, you can play with idioms and slang to create a unique dialect for your characters, that sets your fictional world apart from our own. Writers of historical fiction will also want to pay close attention to dialect, to ensure that any vocabulary being used is authentic.

So while language building isn’t essential, any little details like these that you can add to your worldbuilding will help create a richer and more immersive setting for your story.

Civilizations are defined by their history. That might be a very broad statement — but it contains a kernel of truth. Writers should have a solid grasp on the history of their world, regardless of genre, and should be familiar with the key events that matter to the story they’re telling or the culture they’re exploring. So, how can you go about this?

Once again, a popular way to flesh out the history of your world is to borrow from our own. The line between historical fiction and fantasy is somewhat blurred, and with good reason. A good fantasy world will have a history that’s every bit as interesting as the one we have here on Earth Prime, so why not draw inspiration from it?

Going back to A Song of Ice and Fire , Martin famously patterned his book's central conflict after The War of the Roses. Using a veiled version of English history as his starting point, Martin then fills in the rest of his rich history with dragons, mad kings, and ice zombies. Similarly, RF Kuang’s The Poppy War is a fantastical reinterpretation of 20th-century China, and contains a fantasy drug-driven conflict inspired by the real-world Opium wars.

Speculate on history-altering moments

Let’s say you’re dealing with a futuristic version of our reality: there’s still plenty of work to be done. You need to have some idea of what’s happened between now and the time when you set your book. Start by speculating on developments in technology and society. Then, crucially, figure out how these changes have affected the characters and cultures in your book.

If your book is an “alternate history”, it may stem from a single “what if” question. Think of a single point of divergence: a moment in history that shifted ever-so-slightly, leading to changes that ripple forward through time.

In Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle , the point of divergence comes with the assassination of President Franklin Roosevelt in the early 1930s. It results in a continuation of the Great Depression and American isolationism, allowing Germany and Japan to win World War II. The book then answers the question: “What would 1960s America be like if the Allies lost the war?”

Perhaps the defining feature of any SFF book is its systems, whether they be magical or technological. It’s important to consider the details of how these things work carefully; just waving your hand and saying “and there’s magic” won’t cut it. You’ll have to define the magical or supernatural elements of your world.

With both science fiction and fantasy worldbuilding, you’re likely to come across the phrases “hard” and “soft” frequently. These labels are a (somewhat arbitrary, but still helpful) way of distinguishing between different types of SFF. Let’s take a look further, so you can decide where your world falls on the spectrum.

Spell out the rules of hard magic

A hard magic system is one defined by its rules, and which has clear and explicit boundaries on when said magic does and doesn’t work, and what the consequences of using magic are.

A great example of this type of magic system is Brandon Sanderson’s Mistborn series, set in a world where the primary form of magic is allomancy : a system whereby users swallow different metals, and metabolize them to different effects. Dedicated fans have been able to catalog all the possible variations of allomancy, and have discovered a clear cause-and-effect relationship between the actions of allomancers and their consequences, making for a true hard magic system.

As you can imagine, designing a hard magical system is a pretty significant undertaking that may involve a lot of variables. For that reason, it’s often worth dedicating a good chunk of your worldbuilding time to making sure your system is watertight.

Play with mystery and soft magic

You can choose not to explain how magic works and allow it to retain some of its mystery. After all, as soon as you explain all of magic’s secrets, it almost ceases to be magic.

One example of a “soft” magic system, one which doesn’t have hard and fast rules, is the one in Belgariad . The sorcerers in David Eddings’ Belgariad manifest their willpower through a system he calls ‘The Will and the Word’. It doesn’t require any potions or scrolls , and the so-called “rules” are able to be broken. As such, the limits to magical powers in this world are more conceptual than they are practical, and you’d be hard pressed to describe exactly what can and can’t be done.

While the flexibility of a soft magic system may be appealing — after all, you can’t break a rule if you haven’t established it — it certainly isn’t a get-out-of-jail free card. If you have an ‘anything goes’ approach to magic, your characters’ actions may cease to have consequences: you can bring anyone back from the dead, time can be reversed, your hero can escape from danger just by ‘magic.’ Be sparing with your use of soft magic, and don’t use it as a deus ex machina that miraculously solves your plot issues.

Explain how magic impacts the world

As well as defining the rules of your magic system, consider what it means to have magic. What are the consequences on both your world and the people using it? Maybe it takes a physical toll on the user, or perhaps there are emotional, mental, or social implications to exercising magic.

Who can use magic? If your protagonist is the only person with their gift, how does the world around them react to it? Are they revered or reviled for their abilities?

Conversely, what happens if someone who should have powers, doesn’t? For example, in Codex Alera by Jim Butcher, the people of Alera bond in childhood with one or more "furies" — elementals of air, water, fire, earth, wood, or metal. Everyone, save the protagonist Tavi who happens to be the crown prince of Alera. This lack of bond comes to have major consequences as noblemen around him begin to eye his ultra-powerful father’s throne.

If, as in Codex Alera , magic is widespread, how do people learn how to use it? Trudi Canavan’s Black Magician trilogy has a Magician’s Guild, where people work their way up through a structured hierarchy. Wizards in Harry Potter attend boarding school and end up with soul-crushing jobs in magical middle management. By imagining how magic would function practically in your world, your book will become all the more believable and relatable.

Now that we’ve discussed magical systems, it’s time to turn our attention to science…

Be precise if you use hard science

This is a brand of writing with a particular basis in technological fact. Best known for his work on 2001: A Space Odyssey , Arthur C. Clarke is one of the greatest pioneers in this field, whose fictional inventions bear close resemblance to everyday items in the 21st century.

One great contemporary example of the hard science is Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem , a novel which explores a real-life phenomenon in orbital mechanics, and imagines a three-star system containing a single Earth-like planet which experiences extreme destruction as it passes between the three.

The important point is this: if you choose to write about technical science and technology, you should get your facts right. Many fans of the genre will likely know more about science than you do. If you get the details wrong, they will call you out on it; take for example Larry Niven, who was mercilessly teased by readers for having a character in Ringworld teleport eastward around the Earth to extend his birthday, when doing so would have actually shortened it.

You can always seek advice: the internet is a wellspring of information. If you’re shy about contacting people, Wikipedia is not a terrible place to start your research.

..or give yourself some slack with soft science

We know what you may be thinking — “Dammit, Reedsy, I’m a writer not a physicist!” If you’re not exactly science-minded but still want to write in the genre, you can always take the lead from writers like the late Iain M. Banks. His beloved science fiction novels are about The Culture, a post-scarcity society where all work is automated, and the citizens leave all the big decisions to a benevolent A.I.

Banks’ universe is full of science fiction tropes like droids and spaceships — but he doesn’t really explain how any of it works. It makes perfect sense from a storytelling point of view: novels set in the modern day rarely explain how iPads work. To us, they’re simply a function of everyday living. Banks makes a conscious decision to focus on story and character and he proves that you don’t need to know much science to write great science fiction.

Whether you go hard or soft, it’s important to establish your system ahead of time, so that you can remain consistent and logical throughout your work. Knowing how involved you want your systems to be will also mean you can plan how and when to deploy your exposition to maximum effect.

It may not sound too exciting, but considering something as fundamental as the economics of your world can be extremely helpful in making it a believable one. This isn't essential, but having an understanding of the economy can help you imagine how your characters will move through the world.

Take, for example, Anne McCaffrey’s iconic fantasy series, Pern . While the dragons are probably what most readers come away remembering, those who play close attention to the mechanics of the world are rewarded with a fascinating system to wrap their heads around. In Pern, the wooden tokens used for trade, “marks”, hold no intrinsic value – they don’t correspond to, for instance, a measure of precious metal, but are simply worth what they are traded for. So, your mark may be more or less valuable, depending on simply how well you are able to haggle to trade it.

Your economy may also be a speculative one, like the post-scarcity economy in Iain Banks’ Culture series. The series explores the implications of a world where most goods can be produced abundantly with minimal or no human labor, something Banks describes as “space socialism”.

As a minimum, it’s good to consider what the main valuables are in your world, how trade takes place (is it a barter system? Do people trade with money?), what the currency is called if there is one, and where your heroes come in the financial pecking order.

As well as creating the history and economy of your world, you may also want to consider other institutions and power structures, such as religions, governments, or political ideologies. Again, this might be drawn from reality: Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials series features a society dominated by the Magisterium, a religious body modeled in part on the real-world Catholic church.

You might also want to borrow from the past, like the feudal system of Dune, or extrapolate into the future, like the theocratic, totalitarian state of Gilead in Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale.

It’s worth reminding ourselves that stories set in other worlds have always actually been about the world we live in. Some of the most enduring works of science fiction and fantasy are profound commentaries on human culture and, in particular, our relationship to power and powerlessness. So even if your story takes place in a galaxy far far away, always remember to ask yourself what are you trying to say about society or the human condition and try your best to be intentional with how you use real-life source materials.

And with that final point, it’s now over to you: remember to download our free worldbuilding guide for tips on how to create your own fantastic lands and customs. We can’t wait to see your brave new world. Qapla'!*

*Klingon for “good luck”

Continue reading

Recommended posts from the Reedsy Blog

What is the Climax of a Story? Examples & Tips

The climax is perhaps a story's most crucial moment, but many writers struggle to stick the landing. Let's see what makes for a great story climax.

What is Tone in Literature? Definition & Examples

We show you, with supporting examples, how tone in literature influences readers' emotions and perceptions of a text.

Writing Cozy Mysteries: 7 Essential Tips & Tropes

We show you how to write a compelling cozy mystery with advice from published authors and supporting examples from literature.

Man vs Nature: The Most Compelling Conflict in Writing

What is man vs nature? Learn all about this timeless conflict with examples of man vs nature in books, television, and film.

The Redemption Arc: Definition, Examples, and Writing Tips

Learn what it takes to redeem a character with these examples and writing tips.

How Many Sentences Are in a Paragraph?

From fiction to nonfiction works, the length of a paragraph varies depending on its purpose. Here's everything you need to know.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Bring your stories to life

Our free writing app lets you set writing goals and track your progress, so you can finally write that book!

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

From Narnia to Neverland, literature is filled with fictional realms. There are High Fantasy worlds like Middle-Earth or Westeros , where everything is vaguely medieval and vaguely European (but also sometimes there are dragons). There are Urban Fantasy worlds, where goblins and whatnot lurk just beneath the streets of real life London and vampires pick off tourists in dark alleyways. There are whole entire Science Fiction galaxies, where interstellar empires rule and every planet seems to consist of just one biome for some reason. There are, in short, a lot of different directions to go in if you want to build a fictional world of your own. Here are a few tips to get you started.

You may think that fiction is fiction, and you can just start coming up with whatever and call it a fantasy world. And... technically, you are correct. Go nuts. But if you're trying to write a book or a TV show or a Dungeons and Dragons campaign, you're probably going to want to share your fictional world with other people at some point. And they're going to like your story/script/10 straight hours of role-playing a whole lot more if you stick to just a few simple rules for building a creative, fully-realized, comprehensible world:

Pick a Starting Point

It may sound obvious, but pick a tone to start with. Is this going to be a goofy adventure full of talking dragons and subverted fantasy tropes, or a gritty alternate reality where every third baby is turned into a cyborg? Will you have magic? Is it based on our real world with a few tweaks, or set in a wholly different plane of existence? Before you start fiddling with maps and made up languages, you're going to need a general idea of what genre (or mix of genres) you're most interested in messing with.

Write Some Rules

Yes, fantasy worlds are fun because they're not bound by our own laws of reality. But you still need some laws of reality, even if you made them up. Write out a few core rules for this world. Perhaps magic exists, but it always costs a terrible price. Maybe humans still can't breathe in space, but vampires can. There could be time travel in this universe, but no way to actually change the future. Pick your own brand of logic, and then stick to it as much as humanly possible.

Avoid “One Hat" Aliens

If you're crafting a whole fantasy world (or solar system), you're probably going to have a few different races and cultures. Please, please try not to boil any race down to one single hat. Give them more than one trait. If you want to make a species of bloodthirsty cat aliens that's fine, but what's their music scene like? Do some of them enjoy knitting? Do they have different political factions based on the legalization of cat nip? No one culture should be a monolith, even in fiction.

Please Don’t Make Caricatures of Real Cultures

As you try to craft nuanced, multi-dimensional cultures for your fantasy realms, you may be tempted to draw inspiration from real world cultures. Please do so carefully and respectfully. Representing diverse characters is a great thing. But if you realize that all your main characters are noble and coded as European, and all your villains are warlike and riding fantasy elephants and vaguely Middle Eastern, you have made a terrible mistake (I'm looking at you, Tolkien and everyone who copied Tolkien).

Become a History Buff

No, you don't need to read all of actual history in order to make up a fictional history. But unless your world is brand new, you should probably think about the broad strokes of your world's past. Have there been enormous empires in this world? Long periods of peace? Legendary queens? Look to real world history if you feel stuck, and remember that the past is long and full of weird surprises.

Walk Through a “Day in the Life”

OK, so your story is set on the planet of Gondolier, in the city of Tol-Ki'en. Great. What does a typical day look like there? What do the inhabitants eat for breakfast? How present is the government in people's day to day interactions? What does a polite local greeting look like? Is there nightlife? Do kids go to school? What are some common vocations? Decide what daily life looks like for this society before your plot gets in there is ruin it all.

Find Real Life Inspirations

Again, and I want to stress this point, do not take a real world culture and give them pointy ears. That's not good writing. But do look to music, art, cities, and landscapes that interest you for inspiration. Do look up customs from a variety of civilizations and think about how they'd work in the present day. Do look at actual biomes and start asking things like, "If all these tree could talk, how would that change the environment around here?"And of course: do your research, talk to people, get sensitivity readers.

Do Research, Write Lists

Lists are your friend. Make lists of common names in your world. Make lists of town names and good reference websites you find. Seek out indexes of plant names and gem names if you need some fantasy-sounding nonsense in a pinch. Basically, you can never have too many extra lists lying around.

Some people are more into maps than others. If you feel called to create a fantasy map and fill in every last village and valley, go for it. If you're not so into fussing over the details, just jot down a few notes about how far things are from each other. Either way, have a sense of space and terrain before you start with the actual story.

Become a Linguist

You don't have to create a whole fantasy language if that doesn't sound like fun to you. But if you're going to go for language-making, or if you just want to come up with a few fantastical names, take a moment to come up with a few core fantasy vocab words, and then start thinking about how those couple of root words can be used in different combinations to create new meanings entirely.

Don’t Info-Dump

You know all the secret nooks and crannies of this world. But your characters probably don't. Make sure that your characters don't want around spouting facts about the founding of their city and the ecological make up of the Enchanted Forest to the North. Let your readers or listeners learn about this world gradually as they explore it, rather than through huge chunks of exposition.

Think About Cause and Effect

Ask a lot of "What If?" questions. What if this country had never been colonized? How would that affect the culture and technology? What if everyone had a magical animal soul-companion? Would their theology look different? What if we had superheroes, but they were always smashing up cities in their big fights? Even if you're making on small change to the real world, it could have massive ramifications.

Get Specific

Sure, you know what your magical tavern is called, but how does it smell? Your forest may be haunted, but what shade of green are the leaves? What are the dominant tastes in the local cuisine? Get specific about your descriptions so you can evoke a real, lived in place, not just a carbon copy of someone else's world.

Figure Out Why Your Story is Happening NOW

Why NOW? Maybe tensions have been rising on your continent for decades, or maybe a strange has turned everything upside-down in this small town. Whatever it is, decide why NOW is that time in your world's history that best serves your story.

Love Your World

Create a world that you're excited about, even if that means ignoring most of these tips altogether. If you don't love your world, than neither will your readers. Find the quirks and details that make this world so very you, and try not to feel constrained by copying the fantasy realms that went before. This one's all you.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Fiction Writing

How to Write About a Fictional City

Last Updated: October 5, 2022 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Stephanie Wong Ken, MFA . Stephanie Wong Ken is a writer based in Canada. Stephanie's writing has appeared in Joyland, Catapult, Pithead Chapel, Cosmonaut's Avenue, and other publications. She holds an MFA in Fiction and Creative Writing from Portland State University. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 96,211 times.

Writing about a fictional city can be a difficult challenge. We all know that real cities are sections of land with a population. But in order to create a fictional city and use it in a story, you will need to access your imagination and focus on the details of the city to get it right.

Looking at Examples of Fictional Cities

- The fictional city of Basin City or Sin City in Frank Miller’s Sin City .

- The fictional city of King’s Landing in George R. Martin’s A Game of Thrones .

- The fictional city of Oz (The Emerald City) in L.Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz .

- The fictional city of The Shire in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit .

- Most fictional cities are described using a map drawn by the author or by an illustrator working with the author. Examine the maps provided of the fictional cities and notice the level of detail that is put into the maps. For example, the map provided in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit includes the names of places in the language of the novel as well as major landmarks and structures in the fictional area.

- Look at the naming of the areas or streets in the fictional city. The names in a fictional city can carry a lot of importance, as the names come to symbolize certain aspects of the world of the book. For example, the naming of “Sin City” in Frank Miller’s Sin City graphic novels indicates that the area is known for its sinful inhabitants. The name tells the reader something about the area and what to expect from the characters that live in the area.

- Note how the author describes the city. Does she use certain descriptions to characterize the city? In The Game of Thrones by George R. Martin, for example, King’s Landing is described as dirty and smelly, but it is also the seat of the throne. These descriptions create an interesting contrast for the reader.

- Creating a fictional city will also allow you to use elements of a real city you know well, such as your hometown, and twist them around so they become fictional. If you are very familiar and comfortable in a certain real-life area, you can then use what you know and change them slightly to create a fictional world.

- Creating a fictional city will also improve your writing overall, as the more believable your city is in your book, the more believable the world of your book will be to readers. Making a convincing fictional city will strengthen your characters as well, as you can shape the city to fit with the actions and perspectives of your characters.

Creating the Basics of the Fictional City

- You may choose a name that feels generic and sort of “every small town” if you want your story to have a more universal feel to it. A name like Milton or Abbsortford, for example, does not tell readers too much about the town other than it is likely small and in North America. Avoid using a name like Springfield, as this immediately makes readers think of The Simpsons, which may not fit with your story.

- Consider a name that fits the region or area where your fictional city is located. If your city is located in Germany, for example, you may select a German name or a German term that could also function as a name. If your city is located in Canada, you may select a Canadian city that exists and change the name slightly to create a fictional name.

- Avoid names that seem obvious, such as Vengeance or Hell, as the reader will be alerted right away to the meaning behind the name. The use of obvious names can be effective if the town acts in contrast to the name. For example, a town named Hell that has the nicest, most pleasant townspeople.

- Who founded the city? This could be a lone explorer who stumbled on the land or Native peoples who built up the city piece by piece using basic tools. Think about the individual or individuals responsible for founding the city.

- When was the city founded? This can help you get a better sense of the development of the city, as a city founded 100 years ago will have a denser history than a city founded 15 years ago.

- Why was the city founded? Answering this question can help you better describe the city’s past. Maybe the city was founded through colonization, where a foreign explorer claimed the land and colonized it. Or maybe the city was founded by people who discovered empty land and built it up on their own. The reasons for the city’s existence will help you get a better sense of your characters, as they may have personal ties and connections to the city due to how the city was founded and why it was founded.

- How old is the city? The age of the city is another important element. An older city may have city planning details that have been preserved, while a newer city may have very few old buildings and an experimental approach to city planning.

- You should also think about the climate of the city. Is it hot and humid or cold and dry? The climate may also depend on the time of year when your story is taking place. If your story takes place in the middle of winter in a fictional town located in Northern California, for example, it may be warm during the day and cooler at night.

- Consider the racial and ethnic groups in your city. Are there more African American individuals than Latinos or Caucasians? Do certain ethnic groups live in certain areas of the city? Are there areas where certain ethnic groups are not allowed or feel uncomfortable being in?

- Think about the class dynamics in your city. This could mean a character who is middle-class lives in a certain area of the city and a character of an upper class lives in a more lavish or expensive area of the city. Your fictional city may be divided by class, with certain areas off-limits to all classes except for one class.

- You may also notate landscape details, like a mountain range that borders the city or sand dunes that protect the city from the outside. Try to add as many details as possible, as this will help you build a more convincing fictional world.

- If you have a friend who is talented at illustration, you may ask them to help you draw a map of the city in more detail. You can also use online resources to help you build the map. Use a program like Photoshop, for example, to cut and paste images from the internet to create a map or a physical representation of the city.

Adding the Specifics of the Fictional City

- You should also think about what the town is known for, according to the outside world. Maybe the city is known as the center of commerce or has one of the most renowned sports teams.

- Consider what locals love or enjoy about the city, as this will make it feel more unique. What are the hotspots and cool hang out areas in the city? What are the locals proud of in terms of their city and what are they ashamed of or afraid of in their city?

- For example, maybe your character spends a lot of time at the private school located in the city center. Take the time to think about small details of the school, from how the building appears within the surrounding area to the school colors and the school mascot. Focus on the area around the school and the layout of the school, including classrooms and areas your character spends a lot of time in.

- For example, maybe your city has a polluted river that runs through the area. Think of how it smells as you walk by the river. Have your characters comment on the stench of the river and the way the river looks or sounds.

- Your story will likely involve several locations or settings that recur. Focus on using the five senses to describe these recurring settings well, as this will help the world of the story feel more convincing.

- For example, your characters may spend time in a dense urban area in the city. The area may be populated with strange creatures and monsters but it may also have elements you may find in a real-life urban area, like buildings, streets, and alleyways. Having real-life details and imagined details together can make it easier to build a believable world.

- For example, if you have a character who needs to access a magical portal in the middle of the city to time travel, you should make sure the magical portal is described well in the fictional city. The magical portal should contain enough detail to be believable and your character should interact with it in an interesting way. This will ensure your fictional city is supporting your character’s needs and goals.

- Place your character in a situation where she has to walk around or interact with a certain section of the city. Or, have your character use a facility in the city that then allows her to describe how it feels to use the facility. This will give you the opportunity to have descriptions of the fictional city through the perspective of the character, which will feel more believable and convincing to the reader than simply telling the reader about the facility.

- You should also have your characters treat the more fantastical or strange elements of the fictional city casually and in a straightforward manner. If your fictional city is located under water, for example, a character who has lived in the city for a long period of time may not be surprised that he has to get in his submarine to visit with his neighbor. You can describe the character getting into the submarine and programming it for its destination in a casual, everyday kind of way. This will signal to the reader that submarines are common in this fictional city and used as a form of transportation without having to directly tell the reader that this is the case.

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.complex.com/pop-culture/2011/10/the-50-coolest-fictional-cities/

- ↑ http://thewritelife.com/worldbuilding/

- ↑ https://scottwrites.wordpress.com/2009/10/20/how-to-create-your-own-fake-town/

- ↑ http://www.springhole.net/writing/town-and-city-questions.htm

- ↑ http://io9.gizmodo.com/7-deadly-sins-of-worldbuilding-998817537

- ↑ http://terribleminds.com/ramble/2013/09/17/25-things-you-should-know-about-worldbuilding/

About This Article

To write about a fictional city, first think of a name that reflects your story world. For example, if your city is in Germany, you might use a German word for your name, or if it's in Canada, you could take an existing Canadian city and change it slightly. Next, write a historical record including details of why and when your city was founded. Then, write a description of your city to create a sense of its atmosphere, climate, and terrain. Finally, draw a map of your city, including major landmarks and where your main characters live and work. For more tips from our Creative Writing co-author, including how to add specific details, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Chandler B.

May 27, 2017

Did this article help you?

William Royster

Feb 19, 2019

Pavan Kumara

Sep 20, 2016

Giwa Omowumi

Feb 24, 2022

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

Build It and They Will Come: How to Create a Fictional World

Worldbuilding is the subtle backbone of your story. It won’t make or break your novel like the characters or plot might, but it’s necessary for building a believable setting that your readers will embrace. If they’re distracted by inconsistencies in your setting then they might have a hard time focusing on the story. And we don't want that.

There are also certain readers (namely epic fantasy types) who live for worldbuilding and want to know as many details as possible about your made-up world. You might hear people refer to books written in alternate realities as “second world” settings as opposed to ones that mirror our reality here on planet Earth.

Worldbuilding isn’t just for those writing fantasy or sci-fi, though. Even if your book is set in a contemporary world, you need to ensure the rules and principles of your world are followed.

This can be especially important in a contemporary setting because they’re often based on real places. And you better believe that if you get the street intersection wrong at a random corner in Denver, someone from Denver is going to call you out on it.