Kathang Pinoy

Filipino in thoughts and words.

Famous Essays and Speeches by Filipinos

- My Husband's Roommate

- Where is the Patis?

- I Am A Filipino

- This I Believe

- The Philippines A Century Hence by José Rizal (Translated by Charles E. Derbyshire) Part I

- The Philippines A Century Hence by José Rizal (Translated by Charles E. Derbyshire) Part II

- The Philippines A Century Hence by José Rizal (Translated by Charles E. Derbyshire) Part III

- The Philippines A Century Hence by José Rizal (Translated by Charles E. Derbyshire) Part IV

- The Indolence of the Filipinos by José Rizal (Translated by Charles E. Derbyshire)

- The Filipino Is Worth Dying For

- 1983 Arrival Speech of Ninoy Aquino

- Philippines

- The Filipino Authors You Should...

The 7 Most Legendary Filipino Authors

A country shaped by centuries of colonization by violent wars, long-lasting political upheaval, and the idyllic beauty of its islands, the Philippines offers writers plenty of material to work with. In stories drawn from this complex heritage, Filipino authors stand out for their creative, compelling voices. Culture Trip rounds up seven of the best literary talents to come from the Philippines.

Jessica hagedorn.

Best known for her 1990 novel Dogeaters , Jessica Hagedorn was born and raised in the Philippines and relocated to San Francisco in her teens. Hagedorn’s ethnic heritage is a mix of Spanish, Filipino, French, Irish, and Chinese. Dogeaters , which won the American Book Award and was a finalist for the National Book Award, shines a light on the many layers of Filipino society, especially the American influence prevalent in the entertainment industry. Hagedorn is also a poet and playwright. Her first play, Mango Tango , was produced by Joseph Papp in 1978, the same year she moved to New York, where she currently lives with her daughters.

Sionil Jose

A writer deeply concerned with social justice, F. Sionil Jose’s novels have been translated into 22 languages, and he’s one of the most widely read Filipino authors. Sionil Jose’s Rosales Saga is a five-volume work that follows the Samson family and their changing fortunes over a 100-year timeframe. Sionil Jose’s books are especially illuminating for anyone interested in provincial life in the Philippines, the revolution against Spain, and the framework of the Filipino family. His anti-elitist views have made him a somewhat unpopular author within the Philippines, but Sionil Jose’s works are among the most highly acclaimed internationally of any Filipino writer. He won the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Literature in 1980.

Nick Joaquin

Winning the National Artist award for Literature, Nick Joaquín is probably the most esteemed writer the Philippines has produced. Joaquin came from a well-educated family and was published at the early age of 17. After winning a scholarship in a nationwide essay contest, he left the Philippines to study in Hong Kong. On his return to Manila he worked for many years as a journalist, and his highly intellectual writing raised the standards of journalism in the country. Joaquin’s book, The Woman With Two Navels is essential reading in Philippine literature. However many of his short stories, such as “May Day Eve,” are extremely accessible and enjoyable for those new to the Philippines.

Merlinda Bobis

Award-winning writer Merlinda Bobis started off as a painter, but grew into a writer as “painting with words was cheaper.” Bobis’ books, short stories, and poems tell of lesser-known aspects of Filipino life, often from a strong feminist stance. One of her most well-known novels, Fish-Hair Woman , describes a romance between a young village woman and an Australian soldier in the middle of a harrowing conflict that threatens the entire province. The Australian called it a “superb novel” that “maintains its tragic intensity throughout.” Bobis has also won the international Prix Italia award for her play Rita’s Lullaby and the Steele Rudd Award for her short story “White Turtle.”

Jose Dalisay Jr.

Jose Dalisay Jr. writes a popular online column where he’s more commonly known by his pen name, Butch Dalisay. Dalisay was imprisoned during Martial Law, and his experiences from this portion of Philippine history are brought to life in his first novel, Killing Time in a Warm Place . His second novel, Soledad’s Sister tackles the plight of overseas Filipino workers, and was shortlisted for the Man Asian Literary Prize in 2007. Within the Philippines, Dalisay has won 16 Palanca Awards, the country’s highest prize for literature.

Luis Francia

Award-winning author Luis Francia has lived in New York for decades, but his experiences of growing up in the Philippines continue to shape the stories he tells the world. The poet, author, and teacher emigrated to the U.S. after finishing college, where he wrote and co-edited the Village Voice newspaper for more than 20 years. His memoir Eye of the Fish: A Personal Archipelago won a PEN Open Book Award and an Asian American Literary Award. Amitav Ghosh, author of The Glass Palace , described Francia’s memoir as “a hugely readable travelogue and an indispensable guide to a fascinating and richly varied archipelago.”

The Philippines’ national hero was also a prolific writer, poet, and essayist. Jose Rizal’s two novels, Noli me Tangere and El Filibusterismo were social commentaries that sharply revealed the injustices of Spanish colonization while praising the Filipino in his most natural state. The novels, which are surprisingly wry and romantic, crystallized the growing anti-Spanish sentiment and were banned within the Philippines. The execution of Jose Rizal at 35 years old set off the Philippine Revolution and paved the way for the country’s independence. Even without these dramatic events, Rizal’s books and his final poem, “Mi Ultimo Adios,” stand on their own literary merit, and have influenced scores of Filipino writers since.

Culture Trips launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes places and communities so special.

Our immersive trips , led by Local Insiders, are once-in-a-lifetime experiences and an invitation to travel the world with like-minded explorers. Our Travel Experts are on hand to help you make perfect memories. All our Trips are suitable for both solo travelers, couples and friends who want to explore the world together.?>

All our travel guides are curated by the Culture Trip team working in tandem with local experts. From unique experiences to essential tips on how to make the most of your future travels, we’ve got you covered.

Places to Stay

Hip holiday apartments in the philippines you'll want to call home.

The Best Hotels to Book in Palawan, the Philippines

Where to Stay in Tagaytay, the Philippines, for a Local Experience

The Best Resorts in Palawan, the Philippines

What Are the Best Resorts to Book in the Philippines?

Bed & Breakfasts in the Philippines

The Most Budget-Friendly Hotels in Tagaytay

The Best Hotels to Book in Pasay, the Philippines

The Best Hotels to Book In Tagaytay for Every Traveller

The Best Hotels to Book in the Philippines for Every Traveller

The Best Pet-Friendly Hotels in Tagaytay, the Philippines

See & Do

Exhilarating ways to experience the great outdoors in the philippines, culture trip spring sale, save up to $1,656 on our unique small-group trips limited spots..

- Post ID: 1153276

- Sponsored? No

- View Payload

Search form

- ADVERTISE here!

- How To Contribute Articles

- How To Use This in Teaching

- To Post Lectures

Sponsored Links

You are here, our free e-learning automated reviewers.

- Mathematics

- Home Economics

- Physical Education

- Music and Arts

- Philippine Studies

- Language Studies

- Social Sciences

- Extracurricular

- Preschool Lessons

- Life Lessons

- AP (Social Studies)

- EsP (Values Education)

Jose Rizal’s Essays and Articles

Refer these to your siblings/children/younger friends:

HOMEPAGE of Free NAT Reviewers by OurHappySchool.com (Online e-Learning Automated Format)

HOMEPAGE of Free UPCAT & other College Entrance Exam Reviewers by OurHappySchool.com (Online e-Learning Automated Format)

Articles in Diariong Tagalog

“El Amor Patrio” (The Love of Country)

This was the first article Rizal wrote in the Spanish soil. Written in the summer of 1882, it was published in Diariong Tagalog in August. He used the pen name “Laong Laan” (ever prepared) as a byline for this article and he sent it to Marcelo H. Del Pilar for Tagalog translation.

Written during the Spanish colonization and reign over the Philippine islands, the article aimed to establish nationalism and patriotism among the natives. Rizal extended his call for the love of country to his fellow compatriots in Spain, for he believed that nationalism should be exercised anywhere a person is.

“Revista De Madrid” (Review of Madrid)

This article written by Rizal on November 29, 1882 wasunfortunatelyreturned to him because Diariong Tagalog had ceased publications for lack of funds.

Articles in La Solidaridad

“Los Agricultores Filipinos” (The Filipino Farmers)

This essay dated March 25, 1889 was the first article of Rizal published in La Solidaridad. In this writing, he depicted the deplorable conditions of the Filipino farmers in the Philippines, hence the backwardness of the country.

“A La Defensa” (To La Defensa)

This was in response to the anti-Filipino writing by Patricio de la Escosura published by La Defensa on March 30, 1889 issue. Written on April 30, 1889, Rizal’s article refuted the views of Escosura, calling the readers’ attention to the insidious influences of the friars to the country.

“Los Viajes” (Travels)

Published in the La Solidaridad on May 15, 1889, this article tackled the rewards gained by the people who are well-traveled to many places in the world.

“La Verdad Para Todos” (The Truth for All)

This was Rizal’s counter to the Spanish charges that the natives were ignorant and depraved. On May 31, 1889, it was published in the La Solidaridad.

"Vicente Barrantes’ Teatro Tagalo”

The first installment of Rizal’s “Vicente Barrantes” was published in the La Solidaridad on June 15, 1889. In this article, Rizal exposed Barrantes’ lack of knowledge on the Tagalog theatrical art.

“Defensa Del Noli”

The manuscripts of the “Defensa del Noli” was written on June 18, 1889. Rizal sent the article to Marcelo H. Del Pilar, wanting it to be published by the end of that month in the La Solidaridad.

“Verdades Nuevas”(New Facts/New Truths)

In this article dated July 31, 1889, Rizal replied to the letter of Vicente Belloc Sanchez which was published on July 4, 1889 in ‘La Patria’, a newspaper in Madrid. Rizal addressed Sanchez’s allegation that provision of reforms to the Philippines would devastate the diplomatic rule of the Catholic friars.

“Una Profanacion” (A Desecration/A Profanation)

Published on July 31, 1889, this article mockingly attacked the friars for refusing to give Christian burial to Mariano Herbosa, Rizal’s brother in law, who died of cholera in May 23, 1889. Being the husband of Lucia Rizal (Jose’s sister), Herbosa was denied of burial in the Catholic cemetery by the priests.

“Crueldad” (Cruelty),

Dated August 15, 1889, this was Rizal’s witty defense of Blumentritt from the libelous attacks of his enemies.

“Diferencias” (Differences)

Published on September 15, 1889, this article countered the biased article entitled “Old Truths” which was printed in La Patria on August 14, 1889. “Old Truths” ridiculed those Filipinos who asked for reforms.

“Inconsequencias” (Inconsequences)

The Spanish Pablo Mir Deas attacked Antonio Luna in the Barcelona newspaper “El Pueblo Soberano”. As Rizal’s defense of Luna, he wrote this article which was published on November 30, 1889.

“Llanto Y Risas” (Tears and Laughter)

Dated November 30, 1889, this article was a condemnation of the racial prejudice of the Spanish against the brown race. Rizal remembered that he earned first prize in a literary contest in 1880. He narrated nonetheless how the Spaniard and mestizo spectators stopped their applause upon noticing that the winner had a brown skin complexion.

“Filipinas Dentro De Cien Anos” (The Philippines within One Hundred Years)

This was serialized in La Solidaridad on September 30, October 31, December 15, 1889 and February 15, 1890. In the articles, Rizal estimated the future of the Philippines in the span of a hundred years and foretold the catastrophic end of Spanish rule in Asia. He ‘prophesied’ Filipinos’ revolution against Spain, winning their independence, but later the Americans would come as the new colonizer

The essay also talked about the glorious past of the Philippines, recounted the deterioration of the economy, and exposed the causes of natives’ sufferings under the cruel Spanish rule. In the essay, he cautioned the Spain as regards the imminent downfall of its domination. He awakened the minds and the hearts of the Filipinos concerning the oppression of the Spaniards and encouraged them to fight for their right.

Part of the essays reads, “History does not record in its annals any lasting domination by one people over another, of different races, of diverse usages and customs, of opposite and divergent ideas. One of the two had to yield and succumb.” The Philippines had regained its long-awaited democracy and liberty some years after Rizal’s death. This was the realization of what the hero envisioned in this essay.

Dated January 15, 1890, this article was the hero’s reply to Governor General Weyler who told the people in Calamba that they “should not allow themselves to be deceived by the vain promises of their ungrateful sons.” The statement was made as a reaction to Rizal’s project of relocating the oppressed and landless Calamba tenants to North Borneo.

“Sobre La Nueva Ortografia De La Lengua Tagala” (On The New Orthography of The Tagalog Language)

Rizal expressed here his advocacy of a new spelling in Tagalog. In this article dated April 15, 1890, he laid down the rules of the new Tagalog orthography and, with modesty and sincerity, gave the credit for the adoption of this new orthography to Dr. Trinidad H. Pardo de Tavera, author of the celebrated work “El Sanscrito en la Lengua Tagala” (Sanskrit in the Tagalog Language) published in Paris, 1884.

“I put this on record,” wrote Rizal, “so that when the history of this orthography is traced, which is already being adopted by the enlightened Tagalists, that what is Caesar’s be given to Caesar. This innovation is due solely to Dr. Pardo de Tavera’s studies on Tagalismo. I was one of its most zealous propagandists.”

“Sobre La Indolencia De Los Filipinas” (The Indolence of the Filipinos)

This logical essay is a proof of the national hero’s historical scholarship. The essay rationally countered the accusations by Spaniards that Filipinos were indolent (lazy) during the Spanish reign. It was published in La Solidaridad in five consecutive issues on July (15 and 31), August (1 and 31) and September 1, 1890.

Rizal argued that Filipinos are innately hardworking prior to the rule of the Spaniards. What brought the decrease in the productive activities of the natives was actually the Spanish colonization. Rizal explained the alleged Filipino indolence by pointing to these factors: 1) the Galleon Trade destroyed the previous links of the Philippines with other countries in Asia and the Middle East, thereby eradicating small local businesses and handicraft industries; 2) the Spanish forced labor compelled the Filipinos to work in shipyards, roads, and other public works, thus abandoning their agricultural farms and industries; 3) many Filipinos became landless and wanderers because Spain did not defend them against pirates and foreign invaders; 4) the system of education offered by the colonizers was impractical as it was mainly about repetitive prayers and had nothing to do with agricultural and industrial technology; 5) the Spaniards were a bad example as negligent officials would come in late and leave early in their offices and Spanish women were always followed by servants; 6) gambling like cockfights was established, promoted, and explicitly practiced by Spanish government officials and friars themselves especially during feast days; 7) the crooked system of religion discouraged the natives to work hard by teaching that it is easier for a poor man to enter heaven; and 8) the very high taxes were discouraging as big part of natives’ earnings would only go to the officials and friars.

Moreover, Rizal explained that Filipinos were just wise in their level of work under topical climate. He explained, “violent work is not a good thing in tropical countries as it is would be parallel to death, destruction, annihilation. Rizal concluded that natives’ supposed indolence was an end-product of the Spanish colonization.

Other Rizal’s articles which were also printed in La Solidaridad were “A La Patria” (November 15, 1889), “Sin Nobre” (Without Name) (February 28, 1890), and “Cosas de Filipinas” (Things about the Philippines) (April 30, 1890).

Historical Commentaries Written in London

This historical commentary was written by Rizal in London on December 6, 1888.

“Acerca de Tawalisi de Ibn Batuta”

This historical commentaryis believed to form part of ‘Notes’ (written incollaboration with A.B. Meyer and F. Blumentritt) on a Chinese code in the Middle Ages, translated from the German by Dr. Hirth. Written on January 7, 1889, the article was about the “Tawalisi” which refers to the northern part of Luzon or to any of the adjoining islands.

It was also in London where Rizal penned the following historical commentaries: “La Political Colonial On Filipinas” (Colonial Policy In The Philippines), “Manila En El Mes De Diciembre” (December , 1872), “Historia De La Familia Rizal De Calamba” (History Of The Rizal Family Of Calamba), and “Los Pueblos Del Archipelago Indico (The People’s Of The Indian Archipelago )

Other Writings in London

“La Vision Del Fray Rodriguez” (The Vision of Fray Rodriguez)

Jose Rizal, upon receipt of the news concerning Fray Rodriguez’ bitter attack on his novel Noli Me Tangere, wrote this defense under his pseudonym “Dimas Alang.” Published in Barcelona, it is a satire depicting a spirited dialogue between the Catholic saint Augustine and Rodriguez. Augustine, in the fiction, told Rodriguez that he (Augustine) was commissioned by God to tell him (Rodriguez) of his stupidity and his penance on earth that he (Rodriguez) shall continue to write more stupidity so that all men may laugh at him. In this pamphlet, Rizal demonstrated his profound knowledge in religion and his biting satire.

“To The Young Women of Malolos”

Originally written in Tagalog, this famous essay directly addressed to the women of Malolos, Bulacan was written by Rizal as a response to Marcelo H. Del Pilar’s request.

Rizal was greatly impressed by the bravery of the 20 young women of Malolos who planned to establish a school where they could learn Spanish despite the opposition of Felipe Garcia, Spanish parish priest of Malolos. The letter expressed Rizal’s yearning that women be granted the same chances given to men in terms of education. In the olden days, young women were not educated because of the principle that they will soon be wives and their primary career would be to take care of the home and children. Rizal however advocated women’s right to education.

Below are some of the points mentioned by Rizal in his letter to the young women of Malolos: 1) The priests in the country that time did not embody the true spirit of Christianity; 2) Private judgment should be used; 3) Mothers should be an epitome of an ideal woman who teaches her children to love God, country, and fellowmen; 4) Mothers should rear children in the service of the state and set standards of behavior for men around her;5) Filipino women must be noble, decent, and dignified and they should be submissive, tender, and loving to their respective husband; and 6) Young women must edify themselves, live the real Christian way with good morals and manners, and should be intelligent in their choice of a lifetime partner.

Writings in Hong Kong

“Ang Mga Karapatan Ng Tao” (The Rights Of Man)

This was Rizal’s Tagalog translation of “The Rights of Man” which was proclaimed by the French Revolution in 1789.

“A La Nacion Espanola”(To The Spanish Nation)

Written in 1891, this was Rizal’s appeal to Spain to rectify the wrongs which the Spanish government and clergy had done to the Calamba tenants.

“Sa Mga Kababayan” (To My Countrymen)

This writing written in December 1891 explained the Calamba agrarian situation .

“Una Visita A La Victoria Gaol” (A Visit To Victoria Gaol), March 2, 1892

On March 2, 1892,Rizal wrote this account of his visit to the colonial prison of Hong Kong. He contrasted in the article the harsh Spanish prison system with the modern and more humane British prison system.

“Colonisation Du British North Borneo, Par De Familles De Iles Philippines” (Colonization Of British North Borneo By Families From The Philippine Islands)

This was Rizal’s elucidation of his pet North Borneo colonization project.

“Proyecto De Colonization Del British North Borneo Por Los Filipinos” (Project Of The Colonization Of British North Borneo By The Filipinos)

In this writing, Rizal further discussed the ideas he presented in “Colonization of British North Borneo by Families from the Philippine Islands.”

“La Mano Roja” (The Red Hand)

This was a writing printed in sheet form. Written in Hong Kong, the article denounced the frequent outbreaks of fires in Manila.

“Constitution of The La Liga Filipina”

This was deemed the most important writing Rizal had made during his Hong Kong stay. Though it was Jose Ma. Basa who conceived the establishment of Liga Filipina (Philippine League), his friend and namesake Jose Rizal was the one who wrote its constitution and founded it.

Articles for Trubner’s Record

Due to the request of Rizal’s friend Dr. Reinhold Rost, the editor of Trubner’s Record (a journal devoted to Asian Studies), Rizal submitted two articles:

Specimens of Tagal Folklore

Published in May 1889, the article contained Filipino proverbs and puzzles.

Two Eastern Fables (June 1889)

It was a comparative study of the Japanese and Philippine folklore. In this essay, Jose Rizal compared the Filipino fable, “The Tortoise and the Monkey” to the Japanese fable “Saru Kani Kassen” (Battle of the Monkey and the Crab).

Citing many similarities in form and content, Rizal surmised that these two fables may have had the same roots in Malay folklore. This scholarly work received serious attention from other ethnologists, and became a topic at an ethnological conference.

Among other things, Rizal noticed that both versions of the fable tackled about morality as both involve the eternal battle between the weak and the powerful. The Filipino version however had more philosophy and plainness of form whereas the Japanese counterpart had more civilization and diplomacy.

Other Writings

“Pensamientos De Un Filipino” (Reflections of A Filipino)

Jose Rizal wrote this in Madrid, Spain from 1883-1885. It spoke of a liberal minded and anti-friar Filipino who bears penalties such as an exile.

“Por Telefono”

This was a witty satire authored by “Dimas Alang” (one of the hero’s pen names) ridiculing the Catholic monk Font, one of the priests who masterminded the banning of the “Noli”. Published in booklet form in Barcelona, Spain, it narrated in a funny way the telephone conversation between Font and the provincial friar of the San Agustin Convent in Manila.

This pamphlet showed not only Rizal’s cleverness but also his futuristic vision. Amazingly, Rizal had envisaged that overseas telephonic conversations could be carried on—something which was not yet done during that time (Fall of 1889). It was only in 1901, twelve years after Rizal wrote the “Por Telefono,” when the first radio-telegraph signals were received by Marconi across the Atlantic.

“La Instruccion” (The Town Schools In The Philippines)

Using his penname “Laong Laan”, Rizal assessed in this essay the elementary educational system in the Philippines during his time. Having observed the educational systems in Europe, Rizal found the Spanish-administered education in his country poor and futile. The hero thus proposed reforms and suggeted a more significant and engaging system.

Rizal for instance pointed out that there was a problem in the mandated medium of instruction—the colonizers’ language (Spanish) which was not perfectly understood by the natives. Rizal thus favored Philippine languages for workbooks and instructions.

The visionary (if not prophetic) thinking of Rizal might have been working (again) when he wrote the essay. Interestingly, his call for educational reforms, especially his stand on the use of the local languages for instruction, is part of the battle cry and features of today’s K to 12 program in the Philippines ... continue reading (© 2013 by Jensen DG. Mañebog )

Jensen DG. Mañebog , the contributor, is a book author and professorial lecturer in the graduate school of a state university in Metro Manila. His unique textbooks and e-books on Rizal (available online) comprehensively tackle, among others, the respective life of Rizal’s parents, siblings, co-heroes, and girlfriends. (e-mail: [email protected] )

Tag: Jose Rizal’s Essays and Articles

For STUDENTS' ASSIGNMENT, use the COMMENT SECTION here: Bonifacio Sends Valenzuela to Rizal in Dapitan

Ourhappyschool recommends.

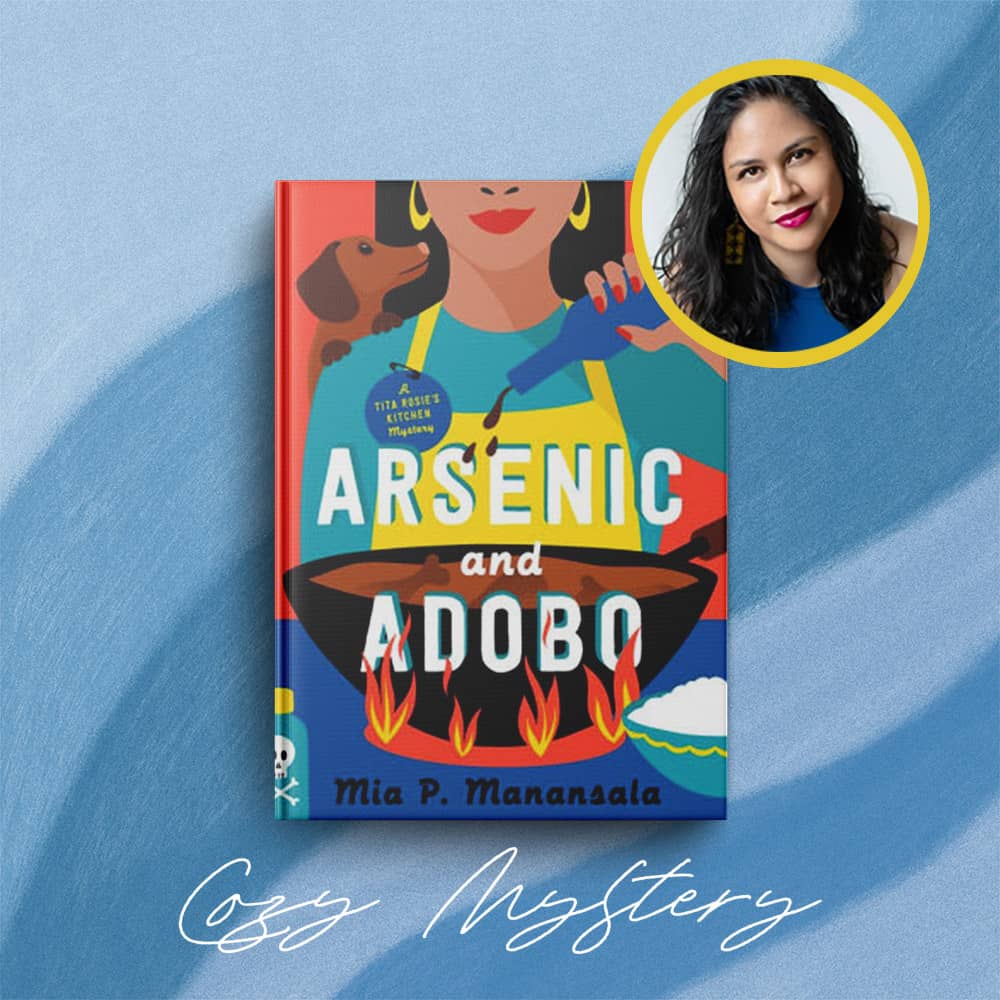

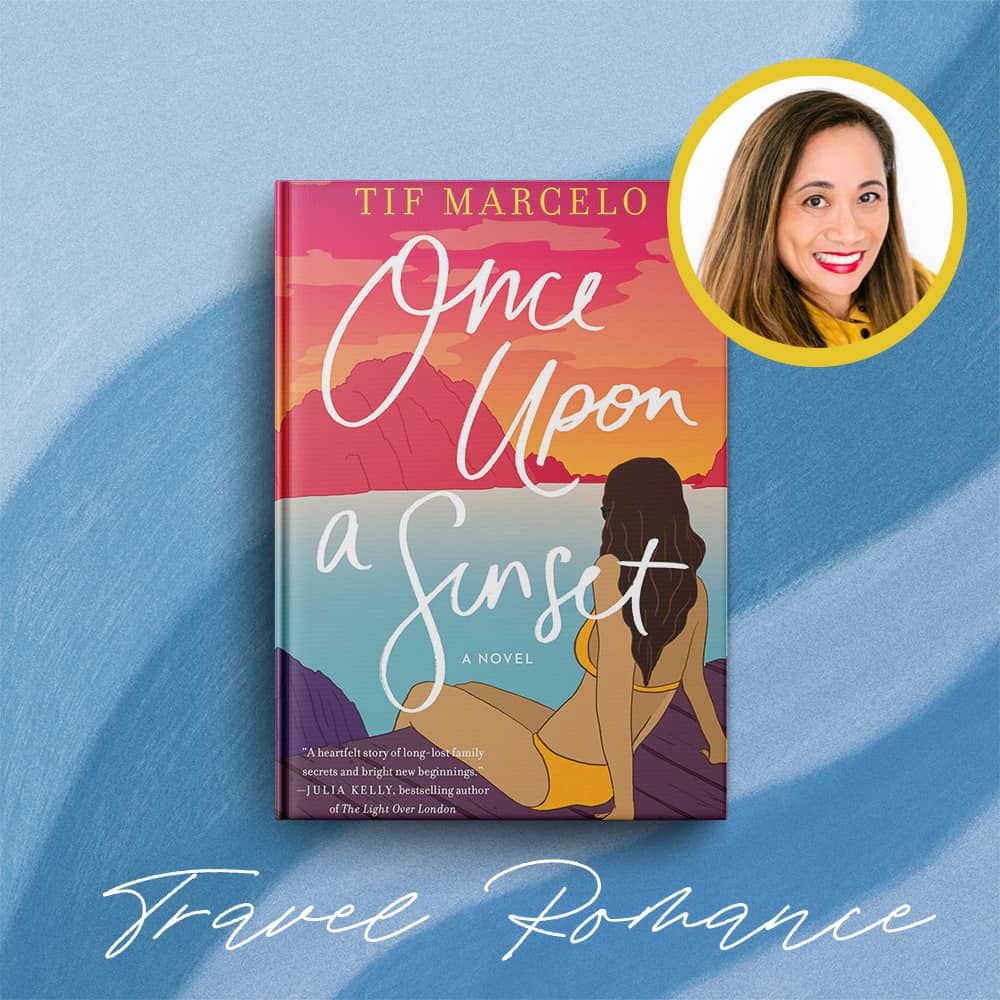

18 Best Filipino Authors on Your Must-Read List

Are you looking for a new book to read? Check out these 18 best Filipino authors that you will absolutely love.

Many people living in the Philippines have had intense struggles through poverty, crime, and cultural challenges. Those who are skilled writers take those challenges and transform them into great works of literature. If you want to get a feel for the human struggle that the people of the Philippines experiencing, reading one of these Filipino authors could give you that insight.

Throughout the works created by famous authors from the Philippines, you will find something to fit almost any taste. From historic to modern, here are the Filipino authors you need to read.

1. Carlos Bulosan

2. jessica hagedorn, 3. jose rizal, 4. randy ribay, 5. barbara jane reyes, 6. elaine castillo, 7. f. sionil jose, 8. gina apostol, 9. joanne ramos, 10. malaka gharib, 11. melissa de la cruz, 12. mia alvar, 13. nick joaquin, 14. marcelo hilario del pilar y gatmaitan, 15. meredith talusan, 16. lysley tenorio, 17. mia hopkins, 18. tess uriza holthe.

Unlimited access to more than 5,500 nonfiction bestsellers. Free trial available.

Best Filipino Authors Ranked

Born in the Philippines in a small farming village called Mangusmana, Carlos Bulosan came from a family who struggled to make ends meet. Determined to help his family and improve his education, Bulosan emigrated to the United States at the age of 17. He started working low-paying jobs while facing racism and illness until he finally learned how to write and put a voice to the struggles of the Filipino people in the United States.

His best-known work is a semi-autobiographical book called America Is in the Heart. He also wrote The Freedom from Want. Bulosan was both a novelist and a poet, and he died in Washington in 1956. If you enjoyed our round-up of the best Filipino authors, we have many more articles on the best authors from around the globe. You might want to check out our list of the best Korean authors . Or use the search bar at the top right of the page to search for authors in a country or region you are interested in.

- Carlos Bulosan (Author)

- English (Publication Language)

- 327 Pages - 04/01/2014 (Publication Date) - University of Washington Press (Publisher)

Born in 1949 in Manila, Jessica Hagedorn is a modern playwright, poet and writer. She came to the United States in 1963 to get her education at the American Conservatory Theater training program. She lives in New York City and has won an American Book Award and the Lucille Lotel Foundation fellowship.

Hagedorn has many famous works to her name, but Mango Tango, her first play, is one of her most famous. She also wrote Burning Heart: A Portrait of the Philippines and the fiction novel Dream Jungle.

Jose Rizal came from a wealthy Filipino family He was well-educated and spent much of his time as a young adult traveling Europe to discuss politics. He also studied medicine at the University of Heidelberg and pushed for Filipino reforms under the Spanish authorities. His execution at the age of 36 put a fast end to his writing career.

Rizal wrote a number of poems as a teenager. He also wrote an Operetta called On the Banks of the Pasig. His first novel, Noli Me Tangere, offended the religious leaders of his area and caused him to be deemed a troublemaker. This likely led to his later arrest for political and religious problems.

Randy Ribay is a Filipino author who writes middle-grade and young-adult fiction. Though he was born in the Philippines, he was raised in the United States and majored in English literature at the University of Colorado with a graduate degree from Harvard. In addition to writing, he teaches English in San Francisco.

Ribay’s first works were poetry, but his book Patron Saints of Nothing is an award-winning work of adult fiction. He also wrote An Infinite Number of Parallel Universes and After the Shot Drops. You might also be interested in our round-up of the best Indian authors of all time.

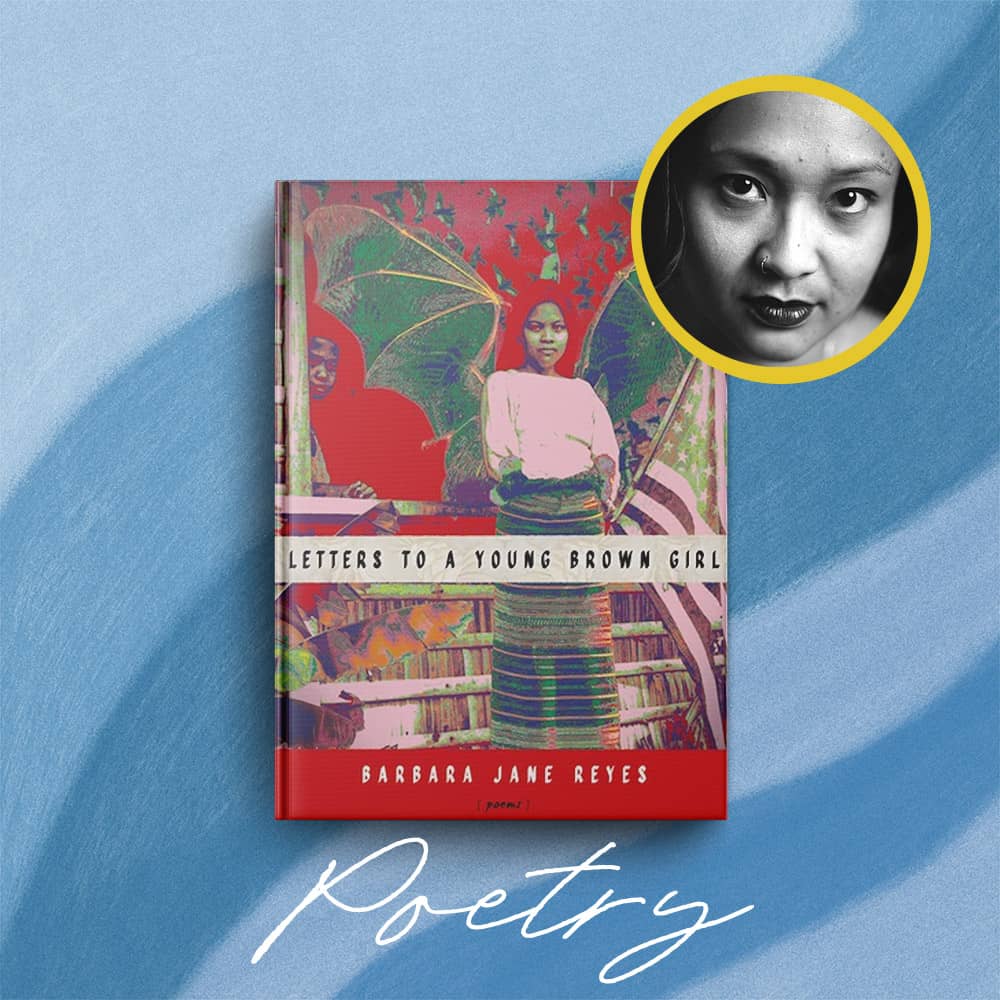

Poet and author Barbara Jane Reyes was born in Manila and moved to the United States as a child. She studied literature and writing in California before launching her award-winning career. She now serves as an adjunct professor at the University of San Francisco.

Reyes’s published works include full-length poetry collections and chapbooks. Gravities of Center, Easter Sunday and Poeta en San Francisco all won awards, including the James Laughlin Award of the Academy of American Poets. Letters to a Young Brown Girl is another popular collection.

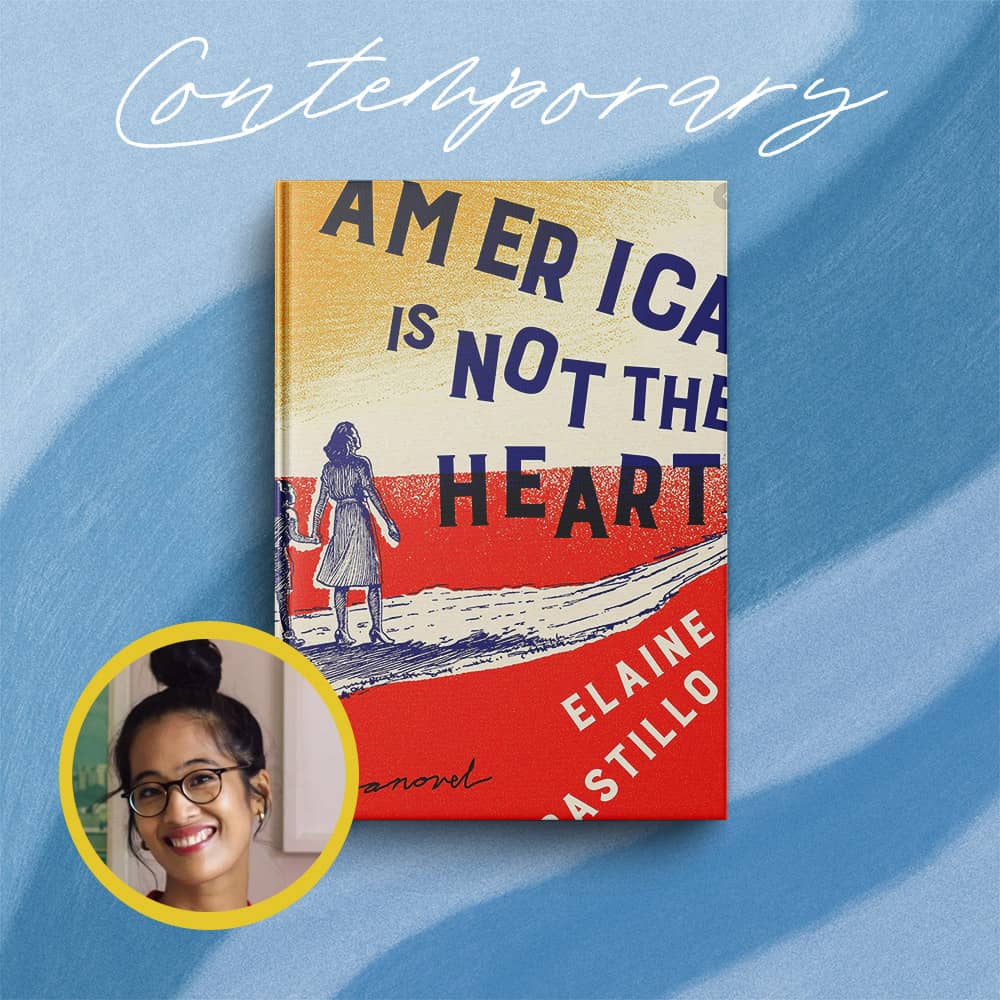

Elaine Castillo is an American writer who is of Filipino descent. She studied at the University of California Berkeley and the University of London. She is passionate about equality for the people of the Philippines, and that comes out in her work.

In 2018 Castillo published her first novel America is Not the Heart. Though this is the only publication she has so far, many reviewers consider her an up-and-coming name in literature. NPR named it one of the best books of the year.

Francisco Sionil Jose was a Filipino writer who is one of the most widely read in the English language. He writes about the social struggles of his culture, and his books and short stories have a huge following. He was born in Pangasinan and attended the University of Santo Tomas before starting his journalism and writing career.

Jose has many novels in his name, including The Pretenders and The Rosales Saga. He also wrote Dusk: A Novel. He won the National Artist of the Philippines award for his literary works. He died at the age of 97 in 2022.

Gina Apostol is a modern Filipino author who was born in Manila and attended Devine World College and the University of the Philippines before coming to the United States to earn her master’s degree at Johns Hopkins University.

Apostol’s first book, Bibliolepsy, recently received republication. She also wrote The Revolution According to Raymundo Mata and Gun Dealers’ Daughter. She has non-fiction works about Filipino American History and short stories to her name as well.

Born in the Philippines, Joanne Ramos moved to Wisconsin when she was just six years old. She attended Princeton University, where she received a bachelor’s degree. She worked in investment banking and private investing before becoming a staff writer for The Economist.

In 2019 Ramos published The Farm, her first novel. It tells the tale of a facility named Golden Oaks, where women serve as surrogate mothers for wealthy clients, and the main character is Filipino, shedding some light on the plight of poor Filipino women and where current cultural ideals could lead them.

Malaka Gharib works for NPR as the digital strategist and deputy editor for their global health and development team. She started this position in 2015, and before that worked with the Malala Fund, which raises money for educational charities.

Gharib is the author of the graphic novel I Was Their American Dream: A Graphic Memoir. It talks about what she faced growing up as a Filipino Egyptian American and introduces young readers to the culture of the Philippines. She also wrote How to Raise a Human and #15Girls, both of which won Gracie Awards.

Melissa de la Cruz grew up in Manila and made the move to San Francisco as a teenager. She majored in art history at Columbia University. She lives in West Hollywood, where she continues to write novels and middle-grade fiction.

Many of de la Cruz’s works are quite famous, including several New York Times bestsellers. She published The Isle of the Lost, a prequel to the 2015 Disney movie Descendants, which spent weeks on the bestseller list. She is also famous for her Blue Bloods series, which has three million copies in print, and she has over 50 books to her name.

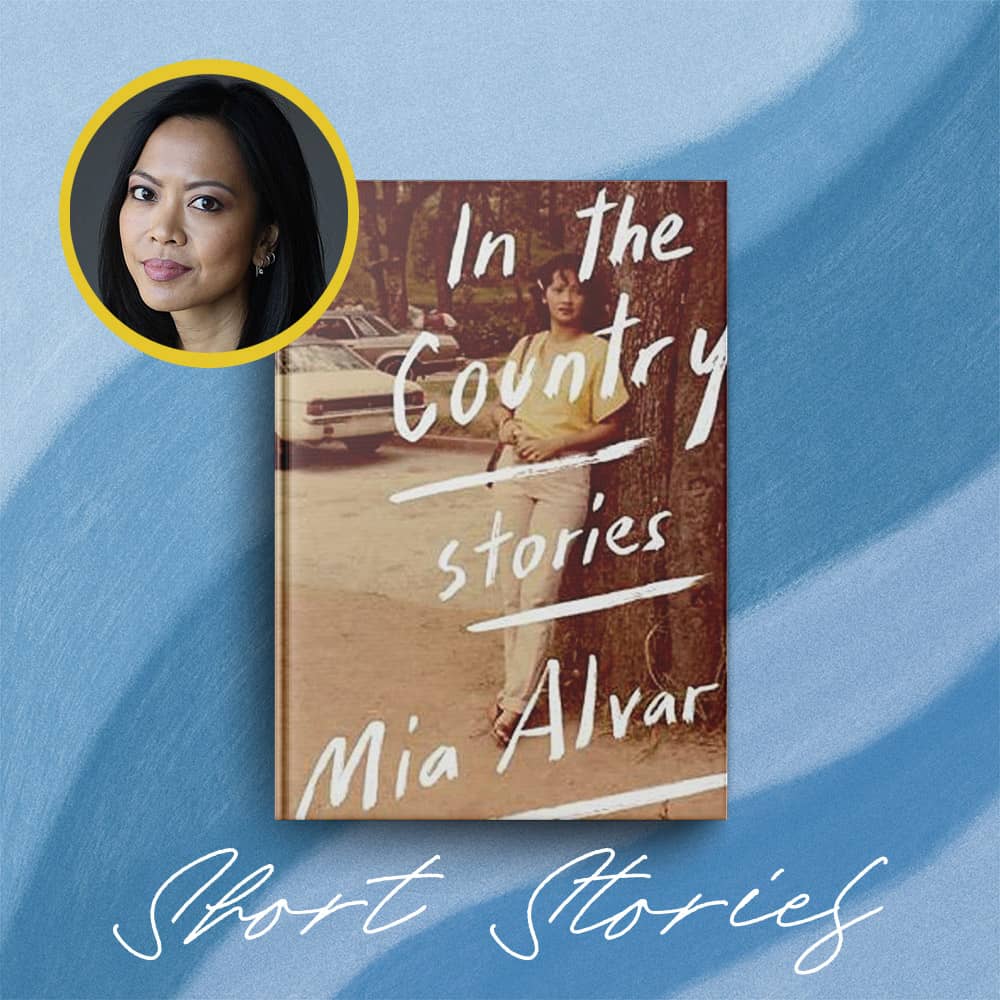

Mia Alvar was born in the Philippines and raised in the United States and Bahrain. She attended Harvard College and Columbia University and currently resides in California.

Alvar won the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction for her short story collection In the Country. She serves as the writer in residence at the Corporation of Yaddo. Sech also earned the Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers award for her work.

Best known for his short stories and novels, Nick Joaquin often wrote under the pen name Quijano de Mania. He was born in 1917 and fought in the Philippine Revolution. After winning a nationwide essay competition, he started contributing poems and stories to magazines and newspapers. He was named the National Artist in 1957.

Joaquin has several novels to his name, including The Woman Who Had Two Navels and A Portrait of the Artist as Filipino. He focused on trying to explain and showcase Filipino culture and its history.

Marcelo Hilario del Pilar y Gatmaitan was often called Plaridel, his pen name. He was born in 1850 and lived in many parts of the Philippines before moving to Barcelona, Spain. Well-educated as a young man, especially in the arts, he became a well-known Filipino writer as an adult. He also attended law school and wrote on legal topics quite often.

Del Pilar was a prolific writer who published many works during his lifetime. The Greatness of God and The Triumph of the Enemies of Progress in the Philippines were some of them.

Meredith Talusan is a Filipino-American author who moved to the United States at the age of 15. He has many excellent essays, stories, and books to her name. She attended Cornell University, where she received an MFA degree, and she worked as a journalist for many well-known publications. In addition to writing, Talusan trained as a dancer.

Talusan has hit the New York Times Bestsellers list with Not That Bad: Dispatches from Rape Culture. She earned the Marsha P. Johnson Fellowship and the Poynter Fellowship at Yale. Many of her books talk about the LGTBQ+ community, and Fairest is her most recent publication.

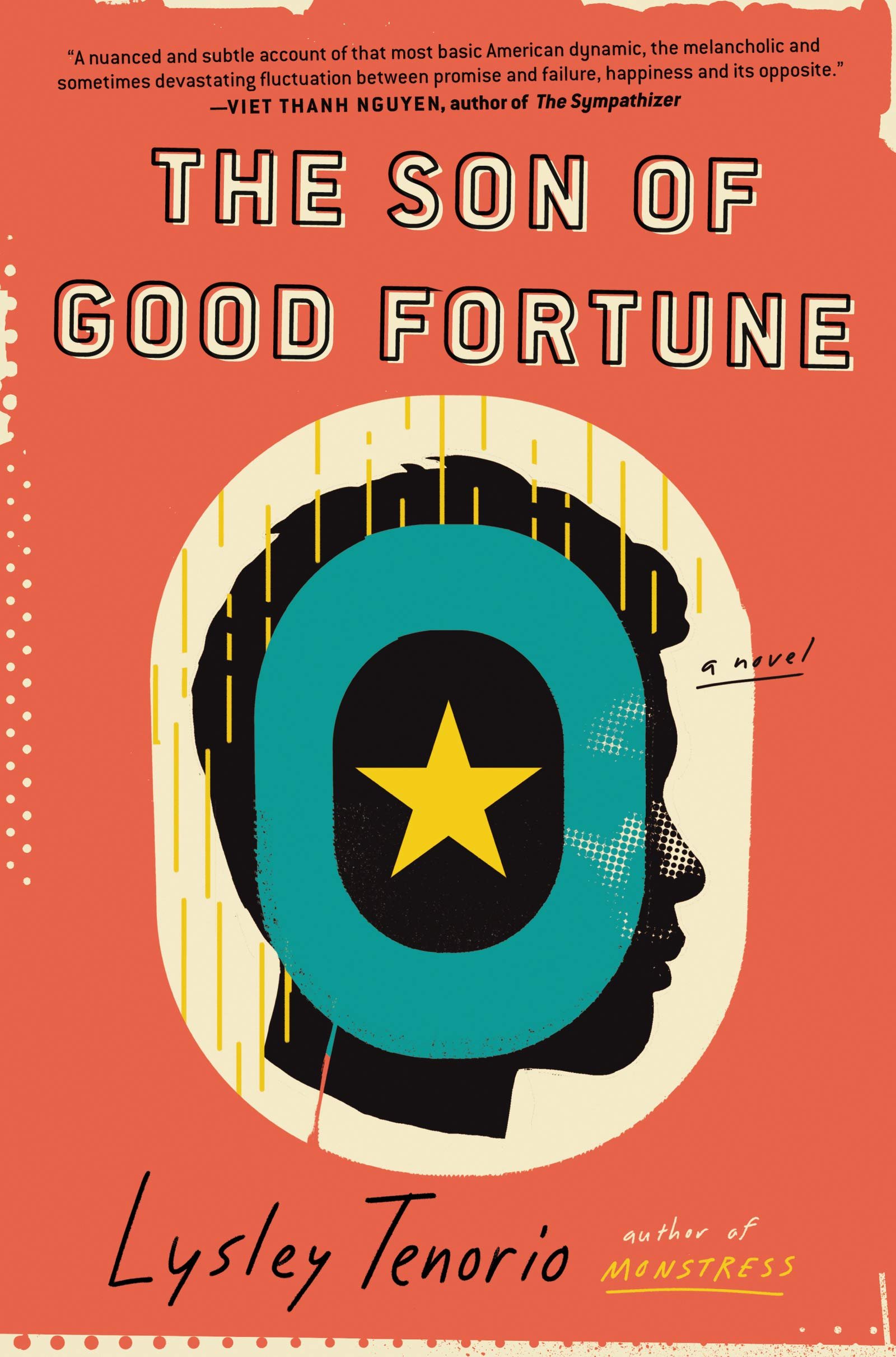

Lysley Tenorio is a Filipino writer who wrote The Son of Good Fortune and Monstress. His work won many awards, including a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, an Edmund White Award, and the Rome Prize. Many of his works have become plays.

Tenorio focuses much of his writing on short stories . He was born in the Philippines and moved to San Francisco to pursue his passion for the arts. He works as an associate professor at Saint Mary’s College of California.

Mia Hopkin s is a Filipino-American writer known for her romance novels. She lives in Los Angeles and continues to publish new novels today. She likes to use working-class heroes in her works.

Mia Hopkins’ novels are full of steamy stories. Trashed is one of her most recent, and it is written from the point of view of the anti-hero of her previous novels. Her books have been featured in Entertainment Weekly, USA Today, and The Washington Post. Several of her works are part of a larger series, which gives the reader the chance to get to know her characters.

Tess Uriza Holthe is a Filipino-American writer who was raised in San Francisco. She attended Golden Gate University and works as an accountant in addition to her work as a writer.

Of her books, When the Elephants Dance is her most famous, hitting several national bestseller lists. She wrote the book during her breaks at work, and she drew information from her own father’s experience in the Philippines to inspire the story. She also wrote The Five-Forty-Five to Cannes. If you enjoyed this guide on the top Filipino authors, you might be interested in our round-up of the best Ukrainian authors .

Nicole Harms has been writing professionally since 2006. She specializes in education content and real estate writing but enjoys a wide gamut of topics. Her goal is to connect with the reader in an engaging, but informative way. Her work has been featured on USA Today, and she ghostwrites for many high-profile companies. As a former teacher, she is passionate about both research and grammar, giving her clients the quality they demand in today's online marketing world.

View all posts

- #WalangPasok

- Breaking News

- Photography

- ALS Exam Results

- Aeronautical Engineering Board Exam Result

- Agricultural and Biosystem Engineering Board Exam Result

- Agriculturist Board Exam Result

- Architecture Exam Results

- BAR Exam Results

- CPA Exam Results

- Certified Plant Mechanic Exam Result

- Chemical Engineering Exam Results

- Chemical Technician Exam Result

- Chemist Licensure Exam Result

- Civil Engineering Exam Results

- Civil Service Exam Results

- Criminology Exam Results

- Customs Broker Exam Result

- Dental Hygienist Board Exam Result

- Dental Technologist Board Exam Result

- Dentist Licensure Exam Result

- ECE Exam Results

- ECT Board Exam Result

- Environmental Planner Exam Result

- Featured Exam Results

- Fisheries Professional Exam Result

- Geodetic Engineering Board Exam Result

- Guidance Counselor Board Exam Result

- Interior Design Board Exam Result

- LET Exam Results

- Landscape Architect Board Exam Result

- Librarian Exam Result

- Master Plumber Exam Result

- Mechanical Engineering Exam Results

- MedTech Exam Results

- Metallurgical Engineering Board Exam Result

- Midwives Board Exam Result

- Mining Engineering Board Exam Result

- NAPOLCOM Exam Results

- Naval Architect and Marine Engineer Board Exam Result

- Nursing Exam Results

- Nutritionist Dietitian Board Exam Result

- Occupational Therapist Board Exam Result

- Ocular Pharmacologist Exam Result

- Optometrist Board Exam Result

- Pharmacist Licensure Exam Result

- Physical Therapist Board Exam

- Physician Exam Results

- Principal Exam Results

- Professional Forester Exam Result

- Psychologist Board Exam Result

- Psychometrician Board Exam Result

- REE Board Exam Result

- RME Board Exam Result

- Radiologic Technology Board Exam Result

- Real Estate Appraiser Exam Result

- Real Estate Broker Exam Result

- Real Estate Consultant Exam Result

- Respiratory Therapist Board Exam Result

- Sanitary Engineering Board Exam Result

- Social Worker Exam Result

- UPCAT Exam Results

- Upcoming Exam Result

- Veterinarian Licensure Exam Result

- X-Ray Technologist Exam Result

- Programming

- Smartphones

- Web Hosting

- Social Media

- SWERTRES RESULT

- EZ2 RESULT TODAY

- STL RESULT TODAY

- 6/58 LOTTO RESULT

- 6/55 LOTTO RESULT

- 6/49 LOTTO RESULT

- 6/45 LOTTO RESULT

- 6/42 LOTTO RESULT

- 6-Digit Lotto Result

- 4-Digit Lotto Result

- 3D RESULT TODAY

- 2D Lotto Result

- English to Tagalog

- English-Tagalog Translate

- Maikling Kwento

- EUR to PHP Today

- Pounds to Peso

- Binibining Pilipinas

- Miss Universe

- Family (Pamilya)

- Life (Buhay)

- Love (Pag-ibig)

- School (Eskwela)

- Work (Trabaho)

- Pinoy Jokes

- Tagalog Jokes

- Referral Letters

- Student Letters

- Employee Letters

- Business Letters

- Pag-IBIG Fund

- Home Credit Cash Loan

- Pick Up Lines Tagalog

- Pork Dishes

- Lotto Result Today

- Viral Videos

Philippine Authors and Their Works – Some Legendary Authors In PH

Here are some of the most famous philippine authors and their works that left remarkable mark in the ph literature..

PHILIPPINE AUTHORS AND THEIR WORKS – These are the legendary Filipino authors and their remarkable contributions.

The Philippine literature has improved greatly over time. We have authors who write fully in Filipino, while others scribbled their thoughts and letters in English adapting the Western style and language. But what most definitely will be of significance is how these creations have shaped and enriched the literature of the country.

Meet some of the most legendary and iconic authors from the Philippines below and a few of their masterpieces:

- She wrote the 1990 novel Dogeaters which won the American Book Award and was declared a finalist for the National Book Award. She also created the play Mango Tango which happened to be her first-ever play.

- He is one of those writers who deeply tackled social justice and issues. He created Rosales Saga – a a five-volume work. He is one of the most widely read Filipino authors. In 1980, he won the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Literature.

- He is a National Artist. He published a work at the age of 17 and his skill has made him won a scholarship from an essay contest where he topped. Among his most famous works is The Woman With Two Navels .

- She wrote numerous books, short stories, and poems which told the lesser-known facts about the life of a Filipino. Fish-Hair Woman is one of her greatest stories that narrated the story of a woman who fell in love with an Australian soldier. Her works Rita’s Lullaby and White Turtle won the international Prix Italia Award and the Steele Rudd Award, respectively.

- He is popularly called Butch Dalisay, his pen name. He lived and got imprisoned in the time of Martial law. his writings include Killing Time in a Warm Place (his first novel) and Soledad’s Sister (his second novel). In his career, he has won 16 Palanca awards.

- He is a poet, author, and a teacher. His Eye of the Fish: A Personal Archipelago won the PEN Open Book Award and an Asian American Literary Award.

- Our very own national hero is a prolific writer. He wrote Noli me Tangere and El Filibusterismo m, which, at current times, is deeply discussed in academic institutions. Mi Ultimo Adios is the last poem he wrote before his execution.

- Functions Of Communication – Basic Functions Of Communication

- Nature Of Communication – Elements, Process, and Models Of Communication

What can you say about this? Let us know!

For more news and updates, follow us on Twitter: @ philnews_ph Facebook: @PhilNews and; YouTube channel Philnews Ph .

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

The Philippine Literature

"i am a filipino".

by Carlos P. Romulo

I am a Filipino – inheritor of a glorious past, hostage to the uncertain future. As such, I must prove equal to a two-fold task – the task of meeting my responsibility to the past, and the task of performing my obligation to the future.

I am sprung from a hardy race – child many generations removed of ancient Malayan pioneers. Across the centuries, the memory comes rushing back to me: of brown-skinned men putting out to sea in ships that were as frail as their hearts were stout. Over the sea I see them come, borne upon the billowing wave and the whistling wind, carried upon the mighty swell of hope – hope in the free abundance of the new land that was to be their home and their children’s forever.

This is the land they sought and found. Every inch of shore that their eyes first set upon, every hill and mountain that beckoned to them with a green and purple invitation, every mile of rolling plain that their view encompassed, every river and lake that promised a plentiful living and the fruitfulness of commerce, is a hollowed spot to me.

By the strength of their hearts and hands, by every right of law, human and divine, this land and all the appurtenances thereof – the black and fertile soil, the seas and lakes and rivers teeming with fish, the forests with their inexhaustible wealth in wild and timber, the mountains with their bowels swollen with minerals – the whole of this rich and happy land has been for centuries without number, the land of my fathers. This land I received in trust from them, and in trust will pass it to my children, and so on until the world is no more.

I am a Filipino. In my blood runs the immortal seed of heroes – seed that flowered down the centuries in deeds of courage and defiance. In my veins yet pulses the same hot blood that sent Lapulapu to battle against the alien foe, that drove Diego Silang and Dagohoy into rebellion against the foreign oppressor,

That seed is immortal. It is the self-same seed that flowered in the heart of Jose Rizal that morning in Bagumbayan when a volley of shots put an end to all that was mortal of him and made his spirit deathless forever; the same that flowered in the hearts of Bonifacio in Balintawak, of Gregorio del Pilar at Tirad Pass, of Antonio Luna at Calumpit, that bloomed in flowers of frustration in the sad heart of Emilio Aguinaldo at Palanan, and yet burst forth royally again in the proud heart of Manuel L. Quezon when he stood at last on the threshold of ancient Malacanang Palace, in the symbolic act of possession and racial vindication.

The seed I bear within me is an immortal seed. It is the mark of my manhood, the symbol of my dignity as a human being. Like the seeds that were once buried in the tomb of Tutankhamen many thousands of years ago, it shall grow and flower and bear fruit again. It is the insigne of my race, and my generation is but a stage in the unending search of my people for freedom and happiness.

I am a Filipino, child of the marriage of the East and the West. The East, with its languor and mysticism, its passivity and endurance, was my mother, and my sire was the West that came thundering across the seas with the Cross and Sword and the Machine. I am of the East, an eager participant in its struggles for liberation from the imperialist yoke. But I know also that the East must awake from its centuried sleep, shake off the lethargy that has bound its limbs, and start moving where destiny awaits.

For I, too, am of the West, and the vigorous peoples of the West have destroyed forever the peace and quiet that once were ours. I can no longer live, a being apart from those whose world now trembles to the roar of bomb and cannon shot. For no man and no nation is an island, but a part of the main, and there is no longer any East and West – only individuals and nations making those momentous choices that are the hinges upon which history revolves.

At the vanguard of progress in this part of the world I stand – a forlorn figure in the eyes of some, but not one defeated and lost. For through the thick, interlacing branches of habit and custom above me I have seen the light of the sun, and I know that it is good. I have seen the light of justice and equality and freedom, my heart has been lifted by the vision of democracy, and I shall not rest until my land and my people shall have been blessed by these, beyond the power of any man or nation to subvert or destroy.

I am a Filipino, and this is my inheritance. What pledge shall I give that I may prove worthy of my inheritance? I shall give the pledge that has come ringing down the corridors of the centuries, and its hall be compounded of the joyous cries of my Malayan forebears when they first saw the contours of this land loom before their eyes, of the battle cries that have resounded in every field of combat from Mactan to Tirad Pass, of the voices of my people when they sing:

Land of the morning.

Child of the sun returning . . .

Ne’er shall invaders

Trample thy sacred shore.

Out of the lush green of these seven thousand isles, out of the heart-strings of sixteen million people all vibrating to one song, I shall weave the mighty fabric of my pledge. Out of the songs of the farmers at sunrise when they go to labor in the fields; out the sweat of the hard-bitten pioneers in Mal-ig and Koronadal; out of the silent endurance of stevedores at the piers and the ominous grumbling of peasants in Pampanga; out of the first cries of babies newly born and the lullabies that mothers sing; out of crashing of gears and the whine of turbines in the factories; out of the crunch of ploughs upturning the earth; out of the limitless patience of teachers in the classrooms and doctors in the clinics; out of the tramp of soldiers marching, I shall make the pattern of my pledge:

I am a Filipino born of freedom, and I shall not rest until freedom shall have been added unto my inheritance – for myself and my children’s – forever.

The Life and Works of Rizal

Your one-stop source of book summaries, chapter analyses, poem and essay interpretations, images, multimedia, news, digital downloads and everything Rizal.

Search This Blog

The indolence of the filipinos: summary and analysis, related pages:.

The Indolence of the Filipino Full Text

The Indolence of the Filipino Short Version

The Indolence of the Filipino Editor's Explanation

The Indolence of the Filipino Highlights and Quotable Quotes

Second, Spain also extinguished the natives’ love of work because of the implementation of forced labor. Filipinos were compelled to work in shipyards, roads, and other public works, abandoning agriculture, industry, and commerce.

Third, Spain did not protect the people against foreign invaders and pirates. With no arms to defend themselves, the natives were killed, their houses burned, and their lands destroyed. As a result, the Filipinos were forced to become nomads, lost interest in cultivating their lands or in rebuilding the industries that were shut down, and simply became submissive to the mercy of God.

Fourth, there was a crooked system of education. What was being taught in the schools were repetitive prayers and other things that could not be used by the students to lead the country to progress. There were no courses in Agriculture, Industry and other fields which were badly needed by the Philippines during those times.

Fifth, the Spanish rulers were a bad example to despise manual labor. The officials reported to work at noon and left early, all the while doing nothing in line with their duties. The women were seen constantly followed by servants who dressed them and fanned them – personal things which they ought to have done for themselves.

Sixth, gambling was established and widely propagated during those times. Almost every day there were cockfights, and during feast days, the government officials and friars were the first to engage in all sorts of bets and gambles.

Seventh, there was a crooked system of religion. The friars taught the naïve Filipinos that it was easier for a poor man to enter heaven, and so they preferred not to work and remain poor so that they could easily enter heaven after they died.

Lastly, the taxes were extremely high, so much so that a huge portion of what the Filipinos earned went to the government or to the friars. When the object of their labor was removed and they were exploited, they were reduced to inaction.

Rizal admitted that the Filipinos did not work so hard because they were wise enough to adjust themselves to the warm, tropical climate. “An hour’s work under that burning sun, in the midst of pernicious influences springing from nature in activity, is equal to a day’s labor in a temperate climate.”

It is important to note that indolence in the Philippines is a chronic malady, but not a hereditary one. Truth is, before the Spaniards arrived on these lands, the natives were industriously conducting business with China, Japan, Arabia, Malaysia, and other countries in the Middle East. The reasons for this said indolence were clearly stated in the essay, and were not based only on presumptions, but were grounded on fact taken from history.

Another thing that we might add that had caused this indolence, is the lack of unity among the Filipino people. In the absence of unity and oneness, the people did not have the power to fight the hostile attacks of the government and of the other forces of society. There would also be no voice, no leader to sow progress and to cultivate it, so that it may be reaped in due time. In such a condition, the Philippines remained a country that was lifeless, dead, simply existing and not living. As Rizal stated in conclusion, “a man in the Philippines is an individual; he is not merely a citizen of a country.”

It can clearly be deduced from the writing that the cause of the indolence attributed to our race is Spain: When the Filipinos wanted to study and learn, there were no schools, and if there were any, they lacked sufficient resources and did not present more useful knowledge; when the Filipinos wanted to establish their businesses, there wasn’t enough capital nor was there protection from the government; when the Filipinos tried to cultivate their lands and establish various industries, they were made to pay enormous taxes and were exploited by the foreign rulers.

It is not only the Philippines, but also other countries, that may be called indolent, depending on the criteria upon which such a label is based. Man cannot work without resting, and if in doing so he is considered lazy, they we could say that all men are indolent. One cannot blame a country that was deprived of its dignity, to have lost its will to continue building its foundation upon the backs of its people, especially when the fruits of their labor do not so much as reach their lips. When we spend our entire lives worshipping such a cruel and inhumane society, forced upon us by aliens who do not even know our motherland, we are destined to tire after a while. We are not fools, we are not puppets who simply do as we are commanded – we are human beings, who are motivated by our will towards the accomplishment of our objectives, and who strive for the preservation of our race. When this fundamental aspect of our existence is denied of us, who can blame us if we turn idle?

Also read: The Indolence of the Filipinos: Highlights and Quotable Quotes

- The Board of Regents

- Office of the University President

- UP System Officials and Offices

- The UP Charter

- University Seal

- Budget and Finances

- University Quality Policy

- Principles on Artificial Intelligence

- UP and the SDGs

- International Linkages

- Philosophy of Education

- Constituent Universities

- Academic Programs

- Undergraduate Admissions | UPCAT

- Graduate Admissions

- Varsity Athletic Admission System

- Student Learning Assistance System

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Academics and Research

- Public Service

- Search for: Search Button

I am a Filipino

I am a Filipino is an essay written by Carlos Peña Romulo, Sr. which was printed in The Philippines Herald on August 16, 1941.

A Pulitzer Prize winner, passionate educator, intrepid journalist and effective diplomat, Romulo graduated from the University of the Philippines in 1918 with a Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences degree. He earned his Master of Arts degree in Philosophy from Columbia University in 1921. He would join the ranks of the UP faculty in 1923 as an Associate Professor in what was then the English Department. He would be later be appointed to the Board of Regents in 1931. Almost three decades later, he would once again be reunited with the University, serving as its 11th President in 1962.

I am a Filipino–inheritor of a glorious past, hostage to the uncertain future. As such I must prove equal to a two-fold task–the task of meeting my responsibility to the past, and the task of performing my obligation to the future.

I sprung from a hardy race, child many generations removed of ancient Malayan pioneers. Across the centuries the memory comes rushing back to me: of brown-skinned men putting out to sea in ships that were as frail as their hearts were stout. Over the sea I see them come, borne upon the billowing wave and the whistling wind, carried upon the mighty swell of hope–hope in the free abundance of new land that was to be their home and their children’s forever.

This is the land they sought and found. Every inch of shore that their eyes first set upon, every hill and mountain that beckoned to them with a green-and-purple invitation, every mile of rolling plain that their view encompassed, every river and lake that promised a plentiful living and the fruitfulness of commerce, is a hallowed spot to me.

By the strength of their hearts and hands, by every right of law, human and divine, this land and all the appurtenances thereof–the black and fertile soil, the seas and lakes and rivers teeming with fish, the forests with their inexhaustible wealth in wild life and timber, the mountains with their bowels swollen with minerals–the whole of this rich and happy land has been, for centuries without number, the land of my fathers. This land I received in trust from them and in trust will pass it to my children, and so on until the world is no more.

I am a Filipino. In my blood runs the immortal seed of heroes–seed that flowered down the centuries in deeds of courage and defiance. In my veins yet pulses the same hot blood that sent Lapulapu to battle against the first invader of this land, that nerved Lakandula in the combat against the alien foe, that drove Diego Silang and Dagohoy into rebellion against the foreign oppressor.

That seed is immortal. It is the self-same seed that flowered in the heart of Jose Rizal that morning in Bagumbayan when a volley of shots put an end to all that was mortal of him and made his spirit deathless forever, the same that flowered in the hearts of Bonifacio in Balintawak, of Gergorio del Pilar at Tirad Pass, of Antonio Luna at Calumpit; that bloomed in flowers of frustration in the sad heart of Emilio Aguinaldo at Palanan, and yet burst forth royally again in the proud heart of Manuel L. Quezon when he stood at last on the threshold of ancient Malacañan Palace, in the symbolic act of possession and racial vindication.

The seed I bear within me is an immortal seed. It is the mark of my manhood, the symbol of dignity as a human being. Like the seeds that were once buried in the tomb of Tutankhamen many thousand years ago, it shall grow and flower and bear fruit again. It is the insignia of my race, and my generation is but a stage in the unending search of my people for freedom and happiness.

I am a Filipino, child of the marriage of the East and the West. The East, with its languor and mysticism, its passivity and endurance, was my mother, and my sire was the West that came thundering across the seas with the Cross and Sword and the Machine. I am of the East, an eager participant in its spirit, and in its struggles for liberation from the imperialist yoke. But I also know that the East must awake from its centuried sleep, shake off the lethargy that has bound his limbs, and start moving where destiny awaits.

For I, too, am of the West, and the vigorous peoples of the West have destroyed forever the peace and quiet that once were ours. I can no longer live, a being apart from those whose world now trembles to the roar of bomb and cannon-shot. I cannot say of a matter of universal life-and-death, of freedom and slavery for all mankind, that it concerns me not. For no man and no nation is an island, but a part of the main, there is no longer any East and West–only individuals and nations making those momentous choices which are the hinges upon which history resolves.

At the vanguard of progress in this part of the world I stand–a forlorn figure in the eyes of some, but not one defeated and lost. For, through the thick, interlacing branches of habit and custom above me, I have seen the light of the sun, and I know that it is good. I have seen the light of justice and equality and freedom, my heart has been lifted by the vision of democracy, and I shall not rest until my land and my people shall have been blessed by these, beyond the power of any man or nation to subvert or destroy.

I am a Filipino, and this is my inheritance. What pledge shall I give that I may prove worthy of my inheritance? I shall give the pledge that has come ringing down the corridors of the centuries, and it shall be compounded of the joyous cries of my Malayan forebears when first they saw the contours of this land loom before their eyes, of the battle cries that have resounded in every field of combat from Mactan to Tirad Pass, of the voices of my people when they sing:

Land of the morning, Child of the sun returning– Ne’er shall invaders Trample thy sacred shore.

Out of the lush green of these seven thousand isles, out of the heartstrings of sixteen million people all vibrating to one song, I shall weave the mighty fabric of my pledge. Out of the songs of the farmers at sunrise when they go to labor in the fields, out of the sweat of the hard-bitten pioneers in Mal-lig and Koronadal, out of the silent endurance of stevedores at the piers and the ominous grumbling of peasants in Pampanga, out of the first cries of babies newly born and the lullabies that mothers sing, out of the crashing of gears and the whine of turbines in the factories, out of the crunch of plough-shares upturning the earth, out of the limitless patience of teachers in the classrooms and doctors in the clinics, out of the tramp of soldiers marching, I shall make the pattern of my pledge:

“I am a Filipino born to freedom, and I shall not rest until freedom shall have been added unto my inheritance—for myself and my children and my children’s children—forever.”

Share this:

University of the philippines.

University of the Philippines Media and Public Relations Office Fonacier Hall, Magsaysay Avenue, UP Diliman, Quezon City 1101 Telephone number: (632) 8981-8500 Comments and feedback: [email protected]

University of the Philippines © 2024

4 Award-Winning Must-Read Filipino Authors and Poets

Whether you’re just starting to take interest in reading books or looking for ways to finally catch up on your to-read list, reading the works of these four Filipino authors might just be the push that you needed. As these authors immerses its readers to the Filipino experience, their books will definitely tug unseen emotions and thoughts. It’s no wonder that they have received received global recognition for their work.

Allan Popa at Saringsing Bikol Writers Workshop 2019 held in Catanduanes

Courtesy of Irvin Parco Sto. Tomas

If you’re into poetry, Allan Popa is one of the first names that come up if you’re asking any scholar in the Philippines. As of 2022, he has published more than ten collections of poetry including Morpo and Samsara , in which he received a National Book Award for Poetry in 2001 and 2002, respectively. Other national recognitions that Allan Popa has received are the Philippines Free Press Literary Award and the Manila Critics Circle National Book Award. Aside from national recognition, he has also earned an MFA degree in poetry at Washington University in Saint Louis. Not only that, but he also won the Norma Lowry Prize and the Academy of American Poets Graduate Prize during his stay in the university.

While the majority of his works are published in Tagalog, there are many translated editions and you can find many of them online.

“The poems...work like parables...(they) are mystical, mysterious, and mystifying, and so require to be read with deliberation and savored with fine discrimination,” says Bienvenido Lumbera, Editor of Sanghaya 2003: Philippine Arts and Culture Yearbook.

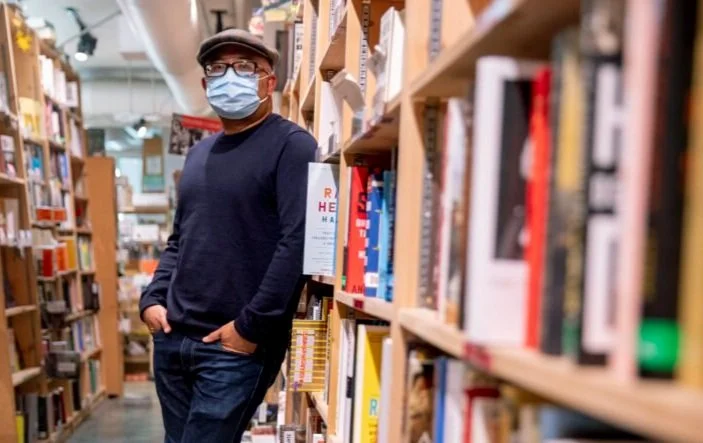

Lysley Tenorio

Courtesy of Jessica Christian via The Chronicle

Fiction writer, Lysley Tenorio has both published and received awards in the United States for writing stories about Filipinos and mostly, their experience in another country. His book titled Monstress (2012), which contains eight short stories, was named a book of the year by the San Francisco Chronicle. His recognitions in the field of literature includes receiving a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, a Whiting Award, a Stegner fellowship, the Edmund White Award, and the Rome Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Aside from having his stories appear in The Atlantic and Zoetrope: All-Story, and Ploughshares, The American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco and the Ma-Yi Theater in New York City has also adapted his stories for stage.

Lysley Tenorio’s most recent book is The Son of Good Fortune (2020) and is beautiful reflection of how vibrant and empathetic his characters are. Voted a Best Book by Amazon in July of 2020, The Son of Good Fortune is a novel about a mother, Maxima, and her son, Excel, who are undocumented Filipino immigrants living in California. Both of them do their best to assimilate. make money and not get caught by the INS. But what they do not know about each other is the ultimate challenge: Maxima seduces men on the internet, eventually cajoling them to wire her money, while Excel flees to a hippie commune with his girlfriend and begins to wonder if he could make it his home.

Conchitina Cruz

Courtesy of Conchitina Cruz

Another poet, Conchitina Cruz, also known as Chingbee Cruz, has written multiple poetry collections, and has published her works in both Philippine and American journals. Her collection of prose poetry, Dark Hours (2005) , where Chingbee Cruz navigates the city through the experiences of different characters, won the National Book Award in 2006. She also holds two Palanca Awards, an esteemed award giving body in the Philippines.

Although she is a Manila-based author, her audience expands in other corners of the world. She has earned her MFA degree at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and her PhD in English from State University of New York (SUNY) Albany. Other works of Conchitina Cruz includes elsewhere held and lingered (2008) , There is no emergency (2015) , and book of essays The Filipino Author as a Producer (2017) and Partial Views: On the Essay as a Genre in Philippine Literary Production (2021). Aside from writing, she currently also co-runs a small press, the Youth & Beauty Brigade.

Cruz’s work is known to be very lyrical and memoir-based stream of consciousness. Her poems illicit deep experience and response from fans of her work.

Gina Apostol

Courtesy of Margarita Corporan via ginaapostol.com

A US-based author, Gina Apostol, without fail, have always gotten a recognition for her published works. If you’re into reading stories of fiction based on the history of the Philippines, you might want to pick up one of her books. Her debut novel, Bibliolepsy (1997) has won the Juan Laya Prize for the Novel Category (Philippine National Book Award). This also holds true for her work, The Revolution According to Raymundo Mata (2009) has also won the same award. She follows these two works with Gun Dealers’ Daughter (2010) in which it won the 2013 PEN/Open Book Award, an award given to authors of color that has published in the United States. Her latest book, Insurrecto (2018), has garnered multiple recognitions such as Publisher Weekly’s one of the Ten Best Books of 2018, Editor’s Choice of the NYT, and being shortlisted for the Dayton Prize. Gina Apostol has also recently won the 2022 Rome Prize in Literature for her next novel.

Written by Maria Manio

YOU MIGHT LIKE TO READ MORE ABOUT

If you’re like me, you’ve always wanted to learn how to speak the native tongue of the Philippines, Tagalog, but you didn’t know where to start. Lucky for us, University of California, Berkeley professor Joi Barrios has written a book for beginners to easily learn and understand Tagalog, the exact language that is spoken in Manila today.

In the past 5 years we have seen a rise on ube flavored or inspired food items. Bring the brightly purple colored Yam in the mainstream spotlight. We made a short list of our favorites right now and where you can get them.

The Philippines has been rich in culture and language even before pre-colonial age. With a booming in trade with its neighboring countries, language in the are has evolved and shared words that would later still be used today.

We listed some loan words from other Asian languages that are used in modern Tagalog.

Top 5 Things To Know Before You Self-Publish Your First Book

6 "very asian" things you used to like before they were cool now everyone is obsessed with.

Prepare for an unforgettable journey at Pokeverse: Choose your journey – Season 1

The ‘hidden gem’ of k-drama: byeon woo seok’s journey through k-drama hits, south korean actor ahn bo hyun swoons filipino fans during his 2024 asia tour fan meeting in manila, little mermaid’s original director provides criticism of the live action adaptation of the movie, a book finds its way back home to the library, 84 years later.

- POP! Culture

- Entertainment

- Special Feature

- INQUIRER.net

POP! is INQUIRER.net’s premier pop culture channel, delivering the latest news in the realm of pop culture, internet culture, social issues, and everything fun, weird, and wired. It is also home to POP! Sessions and POP! Hangout, OG online entertainment programs in the Philippines (streaming since 2015).

As the go-to destination for all things ‘in the now’, POP! features and curates the best relevant content for its young audience. It is also a strong advocate of fairness and truth in storytelling.

POP! is operated by INQUIRER.net’s award-winning native advertising team, BrandRoom.

Email us at [email protected]

MRP Building, Mola Corner Pasong Tirad Streets, Brgy La Paz, Makati City

10 Filipino poets and poems to explore on World Poetry Day

- 21 March, 2022

- No Comments

March 21 is World Poetry Day, and what better way to celebrate than by exploring our country’s own rich poetry scene?

With so many languages and dialects to utilize when describing our rich history and experiences, the Philippines has a lot to offer to the poetry world. Here are 5 poets and 5 poem collections/works to discover on World Poetry Day.

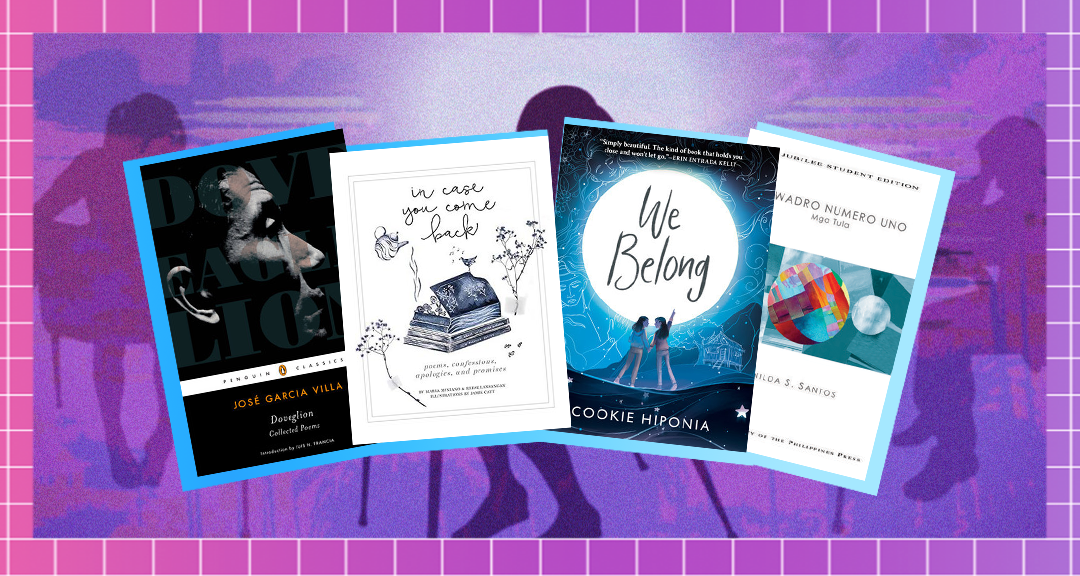

Dovegelion by Jose Garcia Villa

A National Artist for Literature in the Philippines, Jose Garcia Villa was a poetry giant both in the Philippines and in America. Dubbed the “Pope of Greenwich Village”, Villa wrote amongst other literary giants including W.H. Auden, Tennessee Williams, and Gore Vidal.

Dovegelion contains rare and never before published works by Jose Garcia Villa. The title coming from his pen name “Dovegelion” for dove, eagle, and lion. Jose Garcia Villa was definitely a prolific poet, leaving behind numerous works and never shying away from playing with the structure and content of his poems.

Ophelia Dimalanta

Author of collections Flowing On , Love Woman , and Lady Polyester: Poems Past and Present , Ophelia Dimalanta uses sensual stanzas to express her stories and observations. Dimalanta embraces eroticism, saying that it “can be applied if it is functional; if it is important to what you are writing about.”

We Belong by Cookie Hiponia Everman

A contemporary take on a novel-in-verse, We Belong is Cookie Hiponia Everman’s ambitious debut that intertwines a Filipina immigrant story with the mythology of our country.

There isn’t much that Stella and Luna know about their mama, Elsie, other than she immigrated from the Philippines when she was young. As Elsie prepares her kids for bed, they ask her for a story. Elsie gifts them with two—one about her own childhood as a resolute middle child adjusting to the life of immigration, and that of Mayari, the legendary daughter of a god.

Benilda Santos

A recipient of 3 Carlos Palanca Awards for Literature in poetry (for both English and Filipino works), Benilda Santos has proved herself as a poetic power.

Santos’ Kuwadro Numero Uno: Mga Tula was the winner of the National Book Award. Her other poetry collections include Pali-palitong Posporo and Alipato: Mga Bago at Piling Tula .

Santos is also known for her poem Medusa , which is her own rendition of a Greek myth from the point of view of a female monster.

HAI[NA]KU and Other Poems by AA Patawaran

A mix of poems about the big and little things in life. This collection provides humorous and witty takes on love and loss, independence, introspection, and the people/things that walk in and out of your life.

Merlie Alunan

Fluent in languages other than English and Tagalog, Merlie Alunan’s works are sometimes conceived and drafted in Cebuano or Waray before taking their final form in English.

Merlie Alunan’s work includes both poetry and non-poetry collections: Pagdakop sa Bulalakaw ng Uban Pang Mga Balak , Sa Atong Dila: Introduction to Visayan Literature , and Tinalunay: Hinugpong mga Panurat .

To inspire other non-Tagalog writers of the country, Merlie Alunan has organized and facilitated numerous writing workshops in the hopes to get more Waray poems released in the mainstream poetry scene.

In Case You Come Back: Poems, Confessions, Apologies, and Promises by Marla Miniano and Reese Lansangan

Musician Reese Lansangan collaborates with writer Marla Miniano to create a poetry collection chronicling the fascinating intricacies and rituals that make-up everyday life.

From adventures to marshmallows and paper cuts to pixie dust, no rock is left unturned, and no topic is brushed past in this all-encapsulating poetry collection.

Edith Tiempo

Edith Tiempo displays masterful power over language as she vividly describes scenes and events while still scattering various symbols across her stanzas. Another recipient of the National Artist Award for Literature, Edith Tiempo may best be known for her poem The Return . It is a chilling poem about a case of dark nostalgia that comes upon an old man as he tries to relive his youth.

The Last Time I’ll Write About You by Dawn Lanuza

Veteran Filipino YA and romance author Dawn Lanuza makes her debut into poetry with The Last Time I’ll Write About You .

Dawn Lanuza explores any and all things love, the perfect poetry collection for anyone coming from the month of love with any lingering feelings (whether they be good or bad).

Barbara Jane Reyes

With work like Letters to A Young Brown Girl and Diwata , Barbara Jane Reyes is a poetic powerhouse to watch out for.

In Letters to A Young Brown Girl , Reyes expresses all the complicated emotions that come from growing up not only as a young girl, but as a young brown girl. Reyes calls out all the hurts brought upon young brown girls’ fragile and precarious sense of self as they grow-up. Candid and raw, Reyes’ voice is that of an empowered woman standing up for herself, and an encouraging light leading the way for the young brown girls following after her.

In Diwata , Reyes brings to light, not monsters or paranormal beings, but the real-life horrors within our Filipino history and culture. Reyes puts a spotlight on the mistreatment of Filipinas through the years and the overbearing control that was forced upon both their bodies and minds.

And that’s 10 poetry collections/works and poets for you to check out to celebrate World Poetry Day.

Roses are red Violets are blue We love poetry, and you should too!

Don’t be afraid to dip your pen into the poetry scene and even write a few stanzas yourself if you feel so inclined.

Other POP! stories you might like:

10 books by Filipina authors to discover this National Women’s Month

Nostalgic books to remind you why you fell in love with reading

10 most anticipated novels releasing in 2022

About Author

Gari custodio.

Senior Writer

POP! Jr Artist - JC Alingalan

If you prefer your pet to your child, you’re not alone

Marvel and Shonen Jump are teaming up to make Deadpool manga

Related stories, filipino visual artist, journalist among the finalists for this year’s pulitzer prize, reader’s digest uk bids farewell after 86 long years of publication, filipino artist calls out state university for displaying ‘plagiarized’ piece in art exhibit, merlee jayme’s book ‘ten talks, ten cities’ launches in sm aura’s book nook, ‘hulma: paghubog ng kababaihan sa lipunan’ — an art exhibit celebrating the international women’s month.

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

Popping on POP!