"Advertisement"

Essay On Bank Privatisation Pros And Cons {Step by Step Guide}

Hello My Dear Friends, In this post “ Essay On Bank Privatisation Pros And Cons “, We will read the Privatisation of Bank as an Essay In Details. So…

Let’s Start…

Essay On Bank Privatisation

Introduction.

Privatization means selling Whole or Partially a Govt. Sector Company to Private Sector. Or in Other Words, Transferring Ownership to Private Sector. This Step Was also taken in 1991 in New Economic Reform to Reform India’s Economy.

Privatization is considered to bring efficiency and accuracy to a company. The market share of private banks on loans has risen to 36% by 2020 from 21.26% in 2015, while the share of public sector banks has dropped to 59.8% from 74.28%.

Competition has intensified after the RBI has allowed more independent banks since the 1990s. PSBs have higher NPAs than private sector banks. PSBs have underperformed in comparison to private banks.

PM Narendra Modi said that it is the responsibility of the government to give full support to the enterprise and business of the country. But the government itself should run the enterprise and remain its owner, in today’s era it is neither necessary nor is it possible.

The government’s focus should be on the projects related to people’s welfare and development. PM Narendra Modi also said that such a system has to be created in the country, in which there is no lack of government and there is the influence of the government.

Along with the investment, private sectors also bring top-quality manpower, management, as well as global best practices. And this makes things more modern, modernization takes place in the whole sector, the sector expands rapidly and new job opportunities are also created.

Therefore, by monetize and modernize we can increase the efficiency of the entire economy more.

Currently, the government is reportedly looking into the possibility of Punjab & Sind Bank, Maharashtra Bank, and the Indian Overseas Bank , which is currently not part of the existing consolidation program.

It is noteworthy that, there are twelve state-owned banks in India and this comes after a recent merger involving the merger of ten government lenders in four banks. The government wanted the merger of the banks so that they could increase their competition.

Niti Aayog reportedly suggested that the government provide a green flag for “long-term private capital” in the banking sector. Also, it is recommended to provide banking licenses to a few who have built industrial houses with clear instructions that they do not lend to group companies.

According to the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) policy on universal banking licenses, large industrial houses are allowed to enter 10 percent but are not eligible as “eligible entities” facilities for operating banks.

The ownership and management of state-owned banks are regulated by the Banking Companies (Acquisition and Transfer of Undertakings) Act, 1970.

- Essay On NPA In Indian Banks

- Essay On Bank Fraud In India

Why Banks Privatise and What Will Be Its Impact

Improving the Efficiency and Performance of Public Sector Banks (PSBs) is a key element of India’s economic transformation. It is believed to help improve performance and performance.

India is the Largest Country in Southeast Asia with a Large Financial System represented by many financial institutions. India’s financial sector was well developed even before the country’s political independence in 1947.

Bank Privatisation Pros And Cons

How to privatise banks.

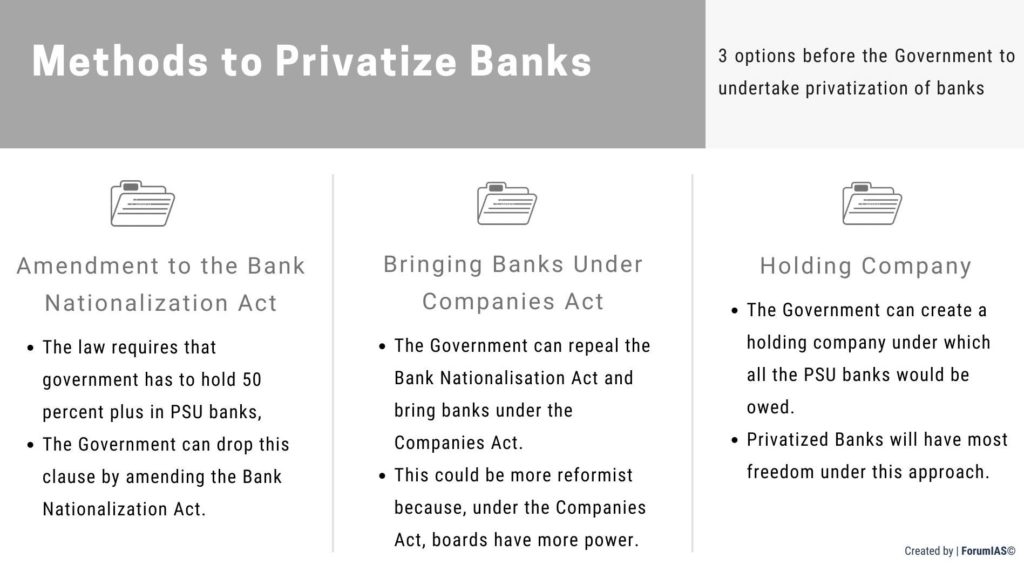

Public companies can be converted into private companies in two ways:

- One option is to sell a controlling stake to a private entity in India.

- The second option for the government is to let its equity States in public sector banks drop below 50%.

Conclusion (Essay On Bank Privatisation)

Any large-scale privatization of public sector banks appears to be fraught with problems. and In the medium term, the best solution is improving governance at public sector banks.

Good, timely as transparent appointments are required at PSBs. Adequate tenure is required to give to chief executive officers. Good quality independent directors are required on PSB boards.

The government is required to play as a regulator rather than the director of the bank. And nudge the PSB management through government nominees rather than through the department of financial services.

Thanks For Reading “ Essay On Bank Privatisation Pros And Cons “.

- Essay On Electric Cars In 1000+ Words | Electric Cars Essay In English

Essay On Cybercrime In 1000+ Words | Cybercrime Essay in English

Essay On Digital Currency In India | Advantages & Disadvantages

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Essay on Privatisation of Banks

Students are often asked to write an essay on Privatisation of Banks in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Privatisation of Banks

Introduction.

Privatisation of banks refers to the transfer of ownership from the public sector to private entities. This process is believed to enhance efficiency and competitiveness in the banking sector.

Benefits of Privatisation

Privatisation can lead to improved services, as private banks generally focus on customer satisfaction. It can also result in increased competition, leading to better products and services.

Drawbacks of Privatisation

However, privatisation can also lead to job losses, as private banks may prioritise cost-cutting. Furthermore, there may be less focus on social responsibilities, as profit becomes the primary goal.

Thus, while privatisation of banks has its benefits, it also has potential drawbacks. It’s important to carefully consider these factors before implementing such changes.

250 Words Essay on Privatisation of Banks

Privatisation of banks refers to the transfer of ownership and control of banking institutions from the public sector to the private sector. This shift has been a major topic of debate globally, with various countries adopting different approaches based on their unique economic and political contexts.

The Rationale Behind Privatisation

The primary argument for privatisation is efficiency. Private sector banks, driven by profit motive, are believed to operate more efficiently, providing better customer service and innovative financial products. Furthermore, privatisation can reduce fiscal burden on the government, allowing it to focus on other areas like infrastructure and social welfare.

Concerns Over Privatisation

However, privatisation is not without concerns. The most significant is the potential for financial exclusion of the underprivileged, as private banks might prioritize profit over social responsibility. Moreover, there are worries about job security for employees and the possibility of a monopolistic market.

The Balanced Approach

A balanced approach could involve maintaining a mix of public and private banks, ensuring competition and safeguarding public interest. This necessitates strong regulatory frameworks to prevent malpractices and ensure accountability.

In conclusion, privatisation of banks is a complex issue with potential benefits and drawbacks. It requires careful consideration of economic, social, and political factors. The ideal banking landscape might be a blend of public and private entities, working under robust regulatory oversight to serve the nation’s financial needs efficiently and responsibly.

500 Words Essay on Privatisation of Banks

Privatisation of banks represents a significant shift in the financial sector, transitioning from public to private ownership. This process has been a topic of debate globally, with arguments both in favour and against it. The subject requires an in-depth understanding of the potential benefits and drawbacks.

Understanding Privatisation

Privatisation is the process where government-owned assets or services are transferred to the private sector. The primary goal is to increase efficiency, promote competition, and reduce public sector burdens. In the context of banks, privatisation can mean selling state-owned banks or reducing the state’s stake in them.

The Case for Privatisation

Proponents of privatisation argue that it can lead to improved efficiency and service quality. Private banks are driven by profit motives and are, therefore, likely to be more efficient in their operations. They are also more inclined to innovate and adopt technology, leading to better customer service.

Privatisation reduces the financial burden on the state. Government-owned banks often require capital infusions to stay afloat, which is a drain on state resources. Privatisation can help alleviate this problem.

Concerns About Privatisation

Despite these potential benefits, privatisation of banks also raises several concerns. One significant concern is the potential for increased risk. Private banks, driven by profit, may engage in risky lending practices, which could lead to financial instability.

Another concern is the issue of social banking. Public sector banks often cater to the needs of rural areas and other sectors that may not be profitable. Privatisation could lead to a decrease in such services, affecting financial inclusion.

Global Experiences

Globally, experiences with bank privatisation have been mixed. In the UK, the privatisation of banks in the 1980s led to increased competition and improved services. However, the 2008 financial crisis raised questions about the stability of private banks.

In contrast, China has maintained a balance of both state-owned and private banks. This has allowed it to achieve financial stability while also promoting competition and innovation.

The privatisation of banks is a complex issue with potential benefits and drawbacks. It could lead to increased efficiency, better services, and reduced state financial burdens. However, it could also increase financial risk and reduce services to less profitable sectors.

The decision to privatise banks should, therefore, be made with careful consideration of these factors. It may be beneficial to adopt a balanced approach, maintaining a mix of both public and private banks, as seen in countries like China. This could help achieve the benefits of privatisation while mitigating the potential drawbacks. Ultimately, the goal should be to create a banking sector that serves the needs of all sectors of society.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Bank

- Essay on Restaurant Food

- Essay on Bad Experience in a Restaurant

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Privatization of Banks: Benefits and Concerns – Explained, pointwise

ForumIAS announcing GS Foundation Program for UPSC CSE 2025-26 from 27th May. Click Here for more information.

- 1 Introduction

- 2 About the Ownership Trend in Banking Sector in India

- 3 What have been the benefits of nationalization of banks?

- 4 What are the arguments in favour of Privatization of Banks (NCAER Report)?

- 5 What are the challenges in Privatization of Banks?

- 6.1 Recommendations of the NCAER report

- 6.2 Recommendations of PJ Nayak Committee

- 6.3 Recommendations of Narashimham committee

- 6.4 Other Measures

- 7 Conclusion

Introduction

A report by National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) has recommended that the Union Government should privatize all Public Sector Banks (PSBs), except the State Bank of India (SBI). The Report further states that the Government ownership hinders the ability of the RBI to regulate the sector. The recommendation of complete privatization of banks has led to sharp reactions from the critics. According to them complete exit of the Government will give rise to systemic risks in the financial sector. The Union Government is aggressively pursuing the exercise of disinvestment. For the ongoing fiscal year FY22, the Government has set a disinvestment target of Rs 1.75 lakh crore. The plan includes privatization of two public sector banks, public listing of the Life Insurance Corporation of India, Shipping Corporation of India, and many other PSUs.

About the Ownership Trend in Banking Sector in India

After the formation of Reserve Bank of India in 1935, to the period till Independence (1947), there were 900 bank failures in India. From 1947 to 1969, 665 banks failed. The depositors of all these banks lost their deposited money. T he Government nationalized 14 major banks in 1969. After this 36 banks failed but these were rescued by merging them with other government banks. This included even bigger banks like Global Trust Bank. 6 more banks were nationalized in 1980.

However, since the liberalization of the economy in 1991, the discourse on bank onwership has changed significantly. Guidelines for setting up private banks were established in 1993 and the ICICI Bank was set up in 1994. Since then the Private Banks have expanded their footprint.

Simultaneously, the approach of the Government has been to reduce its presence in the Banking Sector and reduce the number of Public Sector Banks. In 2019, after a massive consolidation exercise, the number of PSBs reduced from 28 to 12.

During the Union Budget 2020-21 presentation, the Government announced a new policy for strategic disinvestment of public sector enterprises. This policy provides a clear roadmap for disinvestment in all non-strategic and strategic sectors. The Banking Sector falls under the strategic sector. The Government announced privatisation of two PSBs as a part of its disinvestment plan.

What have been the benefits of nationalization of banks?

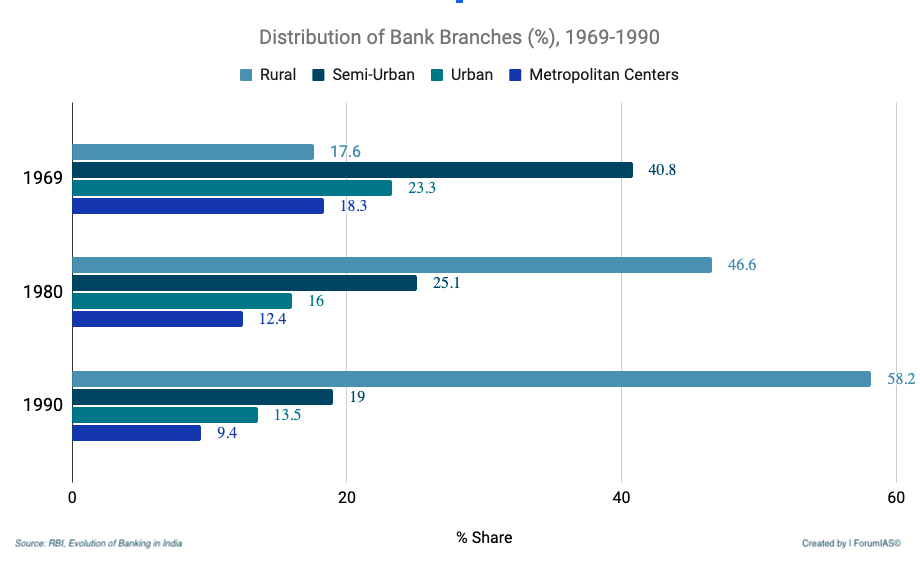

The nationalization of private banks in 1969 resulted in the penetration of banking sector in the rural areas of India. Private Banks were reluctant to open branches in rural India due to low profitability. However, nationalized banks followed the mandate of the Government and helped in financial inclusion.

The Share of Bank Branches in rural areas increased from <18% in 1969 to ~60% by 1990. This shift happened due to several initiatives by Public Sector Banks like the Lead Bank Scheme launched by the RBI in 1969.

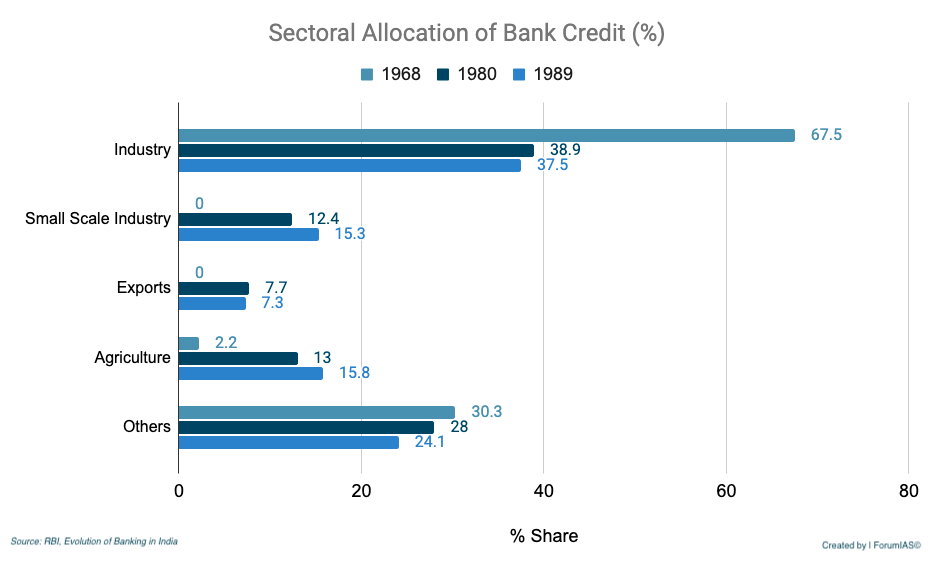

Only after nationalization of banks could small borrowers get credit and there was a shift from class banking to mass banking .

Banks were used to bring about a revolution in agriculture and to carry out activities related to it.

The Sectoral allocation of Bank Credit underwent a change after nationalization of banks. The Share of Agriculture improved from 2.2% in 1968 to 16% in 1989. The share of credit to Industry decreased from 67.5% in 1968 to 37.5% in 1989. This shift happened due to expansion of rural branches and Priority Sector Lending norms.

The proliferation of branches created job opportunities for large section of educated youth. It also benefitted local rural economies.

There was an increased public confidence in the banking system . The growth rate of saving bank deposits witnessed a rapid rise post 1969.

42 crore ordinary people have opened bank accounts as a result of the immense contribution of state-owned banks in opening Jan Dhan Yojana accounts .

What are the arguments in favour of Privatization of Banks (NCAER Report)?

First , private banks have emerged as a credible alternative to PSBs with substantial market share. PSBs have lost ground to private banks, both in terms of deposits and advances of loans. Since 2014-15, almost the entire growth of the banking sector is attributable to the private banks and the SBI.

Second , Government ownership hinders the ability of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to regulate the sector.

At present PSBs are under the dual control of the RBI and the Department of Financial Services of the Ministry of Finance. The RBI handles the governance side of the PSBs under the RBI Act, 1934 . The Department of Financial Services maintains the regulation of PSBs under the Banking Regulation Act, 1949. Thus, RBI does not have the powers to revoke a banking license, shut down a bank, or penalize the board of directors for their faults. Privatization will provide the powers to RBI to control them effectively.

Third , barring SBI, most other PSBs have lagged behind private banks in all the major indicators of performance during the last decade. These PSBs have attained lower returns on assets and equity than their private sector counterparts. The non-performing assets (NPA) of PSBs remain elevated as compared to private banks even as the government infused US$ 65.67 billion into PSBs between 2010-11 and 2020-21 to help them tide over the bad loan crisis.

The market valuation of PSBs, excluding SBI, remains ‘hugely’ below the funds infused in such banks as of May 31, 2022.

Fourth , the under-performance of PSBs has persisted despite a number of policy initiatives aimed at bolstering their performance during this period. These initiatives include: (a) Recapitalisation of PSUs; (b) Constitution of the Bank Board Bureau to streamline and professionalize hiring and governance practices; (c) Prompt corrective action plans ; (d) Consolidation through mergers .

Fifth , the steady erosion in the relative market value of PSBs is indicative of a lack of trust among private investors in the ability of PSBs to meaningfully improve their performance.

Sixth , the current fiscal position of the Union Government is not strong enough to provide huge sums for recapitalization and keep on sustaining sick PSBs.

Seventh , the privatization of banks will have a positive impact on the economy by bringing stability at the macroeconomic level. Privatization of a few loss-making PSBs will ensure that market discipline forces them to rectify their strategy, and this will have a ripple effect on other PSBs.

The pandemic has led to the severe decline in the economic curve of the nation and has made a negative impact on banks as a whole, which makes it imperative to take all possible steps to revive the banking sector.

What are the challenges in Privatization of Banks?

First , as per the stated policy of the Reserve Bank of India, banks cannot be run by industrial houses . However, excluding the industrial houses, there are no entities that have the required financial capability to take over any of the government banks.

Second , private banks have a long history of failures, as noted above (>1500 banks failed between 1935-1969). Recently, the RBI had to come to the rescue of Lakshmi Vilas Bank and YES Bank by pumping of capital by other entities to save these banks. Bank failures and lack of Government intervention will increase the risk in the banking system.

Third , Banks owned by the sovereign government provide more comfort level to depositors . Expansion of private sector in banking will reduce consumer confidence in the sector.

Fourth , Private banks operate with the sole aim of adding shareholder value . In contrast, the government banks also try to serve society and ensure implementation of all government programmes for the social sector. Privatization might have a negative impact on financial inclusion, agriculture credit etc.

Fifth , bank workers are opposed to privatization . as they fear loss of jobs.

What should be the approach going ahead?

Recommendations of the ncaer report.

The two banks chosen for privatization must be the ones with the highest returns on assets and equity, and the lowest NPAs in the last five years. It has recommended Indian Bank and Bank of Baroda as the two top choices for privatization. This would set an example for the success of future privatizations.

It also makes a case for corporate ownership in banks with due diligence as there is “scarcity” of potential large-scale investors in banks. The government must allow foreign investors, including foreign banks and domestic investors, as well as corporate houses to enter the auctions with due diligence

Any potential risk may be minimized by letting a consortium of corporations enter the bidding with the stake of any single corporation capped.

Recommendations of PJ Nayak Committee

Though the Government approved the Bank Board Bureau, the government has to provide enough support for proper functioning. The government can split the Chairman and Managing Director roles. Further, they should be allowed a fixed tenure of 3-5 years.

Recommendations of Narashimham committee

The Government can explore the concept of Narrow Banking. Under this weak PSBs will be allowed to place their funds only in the short term and risk-free assets. This will improve the performance of PSBs.

Other Measures

The Government must create strong recovery laws and take criminal action against wilful defaulters. The challenges in the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) must be addressed. This will provide a faster resolution process. In the meantime, the Government can explore alternate steps such as the concept of Bad Banks.

Privatizing all the PSBs and complete exit of the Government might have significant negative consequences. The Government must find ways to strengthen the governance of banking system and ensure safety of depositors’ money. Complete exit may not be an option, for now.

Source: Business Standard , The Hindu BusinessLine , Outlook , CNBC

Type your email…

Search Articles

Latest articles.

- 10 PM UPSC Current Affairs Quiz 17 May, 2024

- 9 PM UPSC Current Affairs Articles 17 May, 2024

- The rapid growth of the biopharmaceutical industry

- Key provisions of India’s Digital Competition Bill, 2024

- Impact of AI for drug development process

- The issue of Proportional Benefits

- Registered and Recognized Political Parties

- India-Maldives Relations

- Issues Associated with Regulatory Fees

- [Download] New and Improved 9 PM UPSC Weekly Compilation – May 2024 – 2nd week

Prelims 2024 Current Affairs

- Art and Culture

- Indian Economy

- Science and Technology

- Environment & Ecology

- International Relations

- Polity & Nation

- Important Bills and Acts

- International Organizations

- Index, Reports and Summits

- Government Schemes and Programs

- Miscellaneous

- Species in news

Privatization of Banks: Opportunities and Challenges

In 1969, 14 banks were nationalised and in 1980, another 14. The goal was to expand financial services and boost economic growth, but it was already failing. Private banks emerged after reforms of 1991.

12 public sector banks and 21 private sector banks control 70% of the market. The Union Budget 2021-22 aimed at privatizing two public sector banks.

Opportunities

- Effective Regula tions - Government ownership makes it difficult for RBI to regulate the sector, according to NCAER.

- Credit growth - According to economic survey 2020, PSB credit growth has declined since 2013 while new private banks had significant credit growth (between 15 percent and 29 percent).

- Complacency followed by recapitalization - Government controls all PSB operations. This implies bank liability bailout.

- The ex-government recapitalized PSBs with 3.1 lakh crore capital infusion over five years, burdening the state exchequer.

- Decreased risk Appetite - PSB officers are subjected to scrutiny by CVC and CAG making them wary of taking risks

- Strengthening banks –Effective management through private sector participation would create big banks as economic survey suggests India should have at least 6 banks in global top 100 based on its size.

- To deal with banking frauds – PSBs commit 92.9 percent of corporate lending fraud due to poor screening and monitoring.

- Effective management of NPAs – India's banking system's NPAs were 80% PSBs in 2019. 14.6% of loans are gross NPAs.

- More market value - Private banks fetch five times as much value as that of a rupee invested in PSBs.

- Against financial inclusion objectives - Under PM JDY-as of July 2022, more than 45cr beneficiaries have been covered and 78% of these accounts were in PSBs

- Resilience – Indian PSBs were more resilient during the 2008 subprime lending crisis and have also fared well during the Covid crisis.

- Unemployment - Uncertainty in employment prospects of the already employed in PSBs, fear of possible retrenchment might lead to protest from the labour unions.

- Socialistic objectives - PSBs' ATMs in rural areas are twice as many as private banks.

- Labour cost efficiency - PSBs produced more with less labour, according to RBI's recent report.

- Public sector banks played a major role in boosting public confidence due to government guarantees.

- Long history of failures in private banks - EX - RBI had to rescue YES bank by pumping capital by other entities to save the bank.

Way Forward

- NCAER suggested that the banks chosen for privatization must be the ones with the highest returns on assets and equity and the lowest NPAs in the last 5 yrs.

- Research paper by RB I suggested for a more gradual approach towards privatization instead of full exit

- Economic surve y suggested that the efficient of the PSBs could be increased by adopting fintech technology across all banking functions and employee stock ownership across all levels.

- P J Nayak committee recommended that government must reduce its stake in PSBs to less than 50%, establishment of bank investment company to run PSBs.

- Effective usage of data analytics like geo tagging of collateralized assets, connecting lenders all across the banking system through legal identifier system.

- Using credit analytics for prevention of large proportion of NPAs.

- Economic survey suggested for creating a PSB network on line with GSTN for recognizing credit patterns, screening the corporate for fresh loans etc.

Initiatives taken for banking sector reforms-

Conclusion

According to RBI's report, privatisation isn't a cure-all, so a more nuanced approach to bank privatisation is needed to promote economic growth and welfare.

Answer our survey to get FREE CONTENT

Feel free to get in touch! We will get back to you shortly

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Quality Enrichment Program (QEP)

- Total Enrichment Program (TEP)

- Interview Mentorship Program (IMP)

- Prelims Crash Course for UPSC 2024

- Science of Answer Writing (SAW)

- Intensive News Analysis (INA)

- Topper's UPSC PYQ Answer

- PSIR Optional

- NEEV GS + CSAT Foundation

- News-CRUX-10

- Daily Headlines

- Geo. Optional Monthly Editorials

- Past Papers

- © Copyright 2024 - theIAShub

Talk To Our Counsellor

- TRP for UPSC Personality Test

- Interview Mentorship Programme – 2023

- Daily News & Analysis

- Daily Current Affairs Quiz

- Baba’s Explainer

- Dedicated TLP Portal

- 60 Day – Rapid Revision (RaRe) Series – 2024

- English Magazines

- Hindi Magazines

- Yojana & Kurukshetra Gist

- PT20 – Prelims Test Series

- Gurukul Foundation

- Gurukul Advanced – Launching Soon

- Prelims Exclusive Programme (PEP)

- Prelims Test Series (AIPTS)

- Integrated Learning Program (ILP) – 2025

- Connect to Conquer(C2C) 2024

- TLP Plus – 2024

- TLP Connect – 2024

- Public Administration FC – 2024

- Anthropology Foundation Course

- Anthropology Optional Test Series

- Sociology Foundation Course – 2024

- Sociology Test Series – 2023

- Geography Optional Foundation Course

- Geography Optional Test Series – Coming Soon!

- PSIR Foundation Course

- PSIR Test Series – Coming Soon

- ‘Mission ಸಂಕಲ್ಪ’ – Prelims Crash Course

- CTI (COMMERCIAL TAX INSPECTOR) Test Series & Video Classes

- Monthly Magazine

Privatisation of Banks

- February 11, 2021

UPSC Articles

ECONOMY/ GOVERNANCE

Topic: GS-3: Indian Economy and issues relating to planning, mobilization, of resources, growth, development and employment; Government Budgeting GS-3: Government Budgeting

Context : In the Union Budget for 2021-22 , the government has announced taking up the privatisation of two public sector banks (in addition to IDBI Bank) and one general insurance company in the upcoming fiscal.

Laying down a clear policy roadmap for disinvestment, the government has identified four strategic sectors in which it will have bare minimum presence.

- Atomic energy,space and defence;

- Transport and telecommunications;

- Power, petroleum, coal and other minerals;

- Banking, insurance and financial services.

All CPSEs in other sectors will be privatised.

Do You Know?

- PSU banks are under dual control, with the RBI supervising the banking operations and the Finance Ministry handling ownership issues.

- Many committees had proposed bringing down the government stake in public banks below 51% — the Narasimham Committee proposed 33% and the P J Nayak Committee suggested below 50%.

Which are the two PSBs that will be Privatised?

- Currently, there are ten nationalised banks in addition to IDBI Bank and SBI.

- While the government is unlikely to touch the top three including SBI, smaller and middle-level banks are likely to be privatised.

- Government has not disclosed which two banks will be privatised this fiscal.

- The two banks that will now be privatised will be selected through a process in which NITI Aayog will make recommendations, which will be considered by a core group of secretaries on disinvestment and then the Alternative Mechanism (or Group of Ministers).

Reasons for Privatising Public Sector Banks

- Previous reform measures have not yielded results : Years of capital injections and governance reforms have not been able to improve the financial position of in public sector banks significantly. Many of them have higher levels of stressed assets than private banks, and also lag the latter on profitability, market capitalisation and dividend payment record.

- Aligned with Long Term Goal : Privatisation of two public sector banks will set the ball rolling for a long-term project that envisages only a handful of state-owned banks, with the rest either consolidated with strong banks or privatised.

- Reduces Government Burden: Privatisation will free up the government, the majority owner, from continuing to provide equity support to the banks year after year. The government front-loaded Rs 70,000 crore into government-run banks in September 2019, Rs 80,000 crore in in FY18, and Rs 1.06 lakh crore in FY19 through recapitalisation bonds.

- Rationalisation of Banks in Post-COVID Scenario : After the Covid-related regulatory relaxations are lifted, banks are expected to report higher NPAs and loan losses. This would mean the government would again need to inject equity into weak public sector banks. The government is trying to strengthen the strong banks and also minimise their numbers through privatisation.

- Changed Approach to Financial Sector Problems : Privatisation and proposal of setting up an asset reconstruction company entirely owned by banks, underline an approach of finding market-led solutions to challenges in the financial sector.

- Private Participation promotes innovation in market : Private banks’ market share in loans has risen to 36% in 2020 from 21.26% in 2015, while public sector banks’ share has fallen to 59.8% from 74.28%. They have expanded the market share through new innovative products, latest technology, and better services.

What are the challenges associated with increasing Privatisation of Banks?

- Private banks are not without faults

- In the last couple of years, some questions have arisen over the performance of private banks, especially on governance issues.

- ICICI Bank MD and CEO Chanda Kochhar was sacked for allegedly extending dubious loans.

- Yes Bank CEO Rana Kapoor was not given extension by the RBI and now faces investigations by various agencies.

- Lakshmi Vilas Bank faced operational issues and was recently merged with DBS Bank of Singapore.

- Former Axis Bank MD Shikha Sharma too was denied an extension.

- Moreover, when the RBI ordered an asset quality review of banks in 2015, many private sector banks, including Yes Bank, were found under-reporting NPAs.

- Dangers of private banks repeating the mistakes of 1960s

- There is widespread perception that the private sector then was not sufficiently aware of its larger social responsibilities and was more concerned with profit.

- This made private banks unwilling to diversify their loan portfolios as this would raise transaction costs and reduce profits.

- The expansion of branches was mostly in urban areas, and rural and semi-urban areas continued to go unserved

The initial plan of the government was to privatise four. Depending on the success with the first two, the government is likely to go for divestment in another two or three banks in the next financial year.

Connecting the dots:

- Corporates as Banks: Click here

For a dedicated peer group, Motivation & Quick updates, Join our official telegram channel – https://t.me/IASbabaOfficialAccount

Subscribe to our YouTube Channel HERE to watch Explainer Videos, Strategy Sessions, Toppers Talks & many more…

Related Posts :

Us lawsuit on fox news: press freedom vs disinformation, [interview initiative] think, rethink and perform (trp) [day 3] 2020 for upsc/ias personality test.

- [Admissions Start] Baba’s GURUKUL FOUNDATION Classroom Programme for Freshers’ – UPSC/IAS 2025 – Above & Beyond Regular Coaching – OFFLINE and ONLINE. Starts 6th June

- DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS IAS | UPSC Prelims and Mains Exam –17th May 2024

- UPSC Quiz – 2024 : IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs Quiz 17th May 2024

- DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS IAS | UPSC Prelims and Mains Exam –16th May 2024

- UPSC Quiz – 2024 : IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs Quiz 16th May 2024

- DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS IAS | UPSC Prelims and Mains Exam – 15th May 2024

- UPSC Quiz – 2024 : IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs Quiz 15th May 2024

- [MOCK TEST] Sameeksha 2024 – IASbaba’s All India Mock Test for UPSC Prelims 2024 on 19th May (SUNDAY). Available in Offline & Online Mode (English & हिन्दी)

- DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS IAS | UPSC Prelims and Mains Exam –14th May 2024

- UPSC Quiz – 2024 : IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs Quiz 14th May 2024

Don’t lose out on any important Post and Update. Learn everyday with Experts!!

Email Address

Search now.....

Sign up to receive regular updates.

Sign Up Now !

- National Growth and Macroeconomic Centre

- Human Development and Data Innovation

- Investor Education and Protection Fund Chair Unit

- Computable General Equilibrium Modelling and Policy Analysis

- States, Sectors, Surveys, and Impact Evaluation

- Trade, Technology and Skills

- Agriculture and Rural Development

- Centre for Health Policy and Systems

- Books & Reports

- Working Papers

- Interview Series

- Policy Briefs

- Newsletters

- Mission & Vision

- Governing Body

- Director General

- Research Advisory Board

- Annual Reports

- Gender Policy

- Research Opening

- Administrative Opening

- Employee Portal

- Office 365 Login

- Sign-up / Login

Privatization of Public Sector Banks in India: Why, How and How Far

Banks play a critical role in economic growth. In India, the banking sector, dominated by public sector banks (PSBs), has underserved the economy and their stakeholders. The under-performance of PSBs has persisted despite several policy initiatives during the past decade. Meanwhile, private banks have further improved their performance and have gained significant market share. In this paper, we have made the case for privatization of PSBs. Due to its better performance and adhering to the development view of the PSBs, we propose that the State Bank of India (SBI) may remain under government ownership for now, but all other banks should be privatized. In order for them to set an example for the success of future privatizations, the first two banks for privatization should be the ones with better asset quality and higher returns. The most critical element for privatization to succeed would be the withdrawal of the government from the post-privatization board of the bank. The paper proposes a couple of different pathways to successfully transition the sector toward private ownership. It cautions that the status quo will result in further erosion of the market share of PSBs toward oblivion, while impeding India’s economic growth and inflicting substantial costs onto the depositors, firms, taxpayers and the government as their majority owner in the interim.

Researchers

Poonam Gupta is the Director General of National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER), India’s largest economic policy think tank, and a member of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister. Gupta is the founding Director of NCAER’s National Macro and Growth Centre, and editor of its two journals: Margin and Indian Policy Forum. She joined NCAER ... Read More

Arvind Panagariya is Professor of Economics and the Jagdish Bhagwati Professor of Indian Political Economy in the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University. From January 2015 to August 2017, he served as the first Vice Chairman of the NITI Aayog, Government of India in the rank of a Cabinet Minister. He simultaneously ... Read More

Poonam Gupta

Arvind panagariya, ncaer project team:.

- Impact Evaluation

- Search Menu

- Browse content in A - General Economics and Teaching

- Browse content in A1 - General Economics

- A12 - Relation of Economics to Other Disciplines

- A14 - Sociology of Economics

- Browse content in B - History of Economic Thought, Methodology, and Heterodox Approaches

- Browse content in B4 - Economic Methodology

- B41 - Economic Methodology

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C18 - Methodological Issues: General

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C21 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions

- Browse content in C3 - Multiple or Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple Variables

- C38 - Classification Methods; Cluster Analysis; Principal Components; Factor Models

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C59 - Other

- Browse content in C8 - Data Collection and Data Estimation Methodology; Computer Programs

- C80 - General

- C81 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Microeconomic Data; Data Access

- C83 - Survey Methods; Sampling Methods

- Browse content in C9 - Design of Experiments

- C93 - Field Experiments

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D02 - Institutions: Design, Formation, Operations, and Impact

- D03 - Behavioral Microeconomics: Underlying Principles

- D04 - Microeconomic Policy: Formulation; Implementation, and Evaluation

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D10 - General

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- D14 - Household Saving; Personal Finance

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D24 - Production; Cost; Capital; Capital, Total Factor, and Multifactor Productivity; Capacity

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D61 - Allocative Efficiency; Cost-Benefit Analysis

- D62 - Externalities

- D63 - Equity, Justice, Inequality, and Other Normative Criteria and Measurement

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D72 - Political Processes: Rent-seeking, Lobbying, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting Behavior

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- D74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Alliances; Revolutions

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D83 - Search; Learning; Information and Knowledge; Communication; Belief; Unawareness

- D85 - Network Formation and Analysis: Theory

- D86 - Economics of Contract: Theory

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- D92 - Intertemporal Firm Choice, Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E23 - Production

- E24 - Employment; Unemployment; Wages; Intergenerational Income Distribution; Aggregate Human Capital; Aggregate Labor Productivity

- Browse content in E4 - Money and Interest Rates

- E42 - Monetary Systems; Standards; Regimes; Government and the Monetary System; Payment Systems

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E52 - Monetary Policy

- E58 - Central Banks and Their Policies

- Browse content in E6 - Macroeconomic Policy, Macroeconomic Aspects of Public Finance, and General Outlook

- E60 - General

- E61 - Policy Objectives; Policy Designs and Consistency; Policy Coordination

- E62 - Fiscal Policy

- E65 - Studies of Particular Policy Episodes

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F0 - General

- F01 - Global Outlook

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F10 - General

- F11 - Neoclassical Models of Trade

- F13 - Trade Policy; International Trade Organizations

- F14 - Empirical Studies of Trade

- F15 - Economic Integration

- F19 - Other

- Browse content in F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business

- F21 - International Investment; Long-Term Capital Movements

- F22 - International Migration

- F23 - Multinational Firms; International Business

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F32 - Current Account Adjustment; Short-Term Capital Movements

- F34 - International Lending and Debt Problems

- F35 - Foreign Aid

- F36 - Financial Aspects of Economic Integration

- Browse content in F4 - Macroeconomic Aspects of International Trade and Finance

- F41 - Open Economy Macroeconomics

- F42 - International Policy Coordination and Transmission

- F43 - Economic Growth of Open Economies

- Browse content in F5 - International Relations, National Security, and International Political Economy

- F50 - General

- F52 - National Security; Economic Nationalism

- F53 - International Agreements and Observance; International Organizations

- F55 - International Institutional Arrangements

- Browse content in F6 - Economic Impacts of Globalization

- F61 - Microeconomic Impacts

- F63 - Economic Development

- F66 - Labor

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G10 - General

- G15 - International Financial Markets

- G18 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G20 - General

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G22 - Insurance; Insurance Companies; Actuarial Studies

- G23 - Non-bank Financial Institutions; Financial Instruments; Institutional Investors

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G32 - Financing Policy; Financial Risk and Risk Management; Capital and Ownership Structure; Value of Firms; Goodwill

- G33 - Bankruptcy; Liquidation

- G38 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of Government

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H20 - General

- H23 - Externalities; Redistributive Effects; Environmental Taxes and Subsidies

- H25 - Business Taxes and Subsidies

- H26 - Tax Evasion and Avoidance

- H27 - Other Sources of Revenue

- Browse content in H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic Agents

- H31 - Household

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H41 - Public Goods

- H43 - Project Evaluation; Social Discount Rate

- Browse content in H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related Policies

- H52 - Government Expenditures and Education

- H53 - Government Expenditures and Welfare Programs

- H54 - Infrastructures; Other Public Investment and Capital Stock

- H55 - Social Security and Public Pensions

- H56 - National Security and War

- H57 - Procurement

- Browse content in H6 - National Budget, Deficit, and Debt

- H60 - General

- H61 - Budget; Budget Systems

- Browse content in H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental Relations

- H71 - State and Local Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H75 - State and Local Government: Health; Education; Welfare; Public Pensions

- H77 - Intergovernmental Relations; Federalism; Secession

- Browse content in H8 - Miscellaneous Issues

- H83 - Public Administration; Public Sector Accounting and Audits

- H84 - Disaster Aid

- Browse content in I - Health, Education, and Welfare

- Browse content in I0 - General

- I00 - General

- Browse content in I1 - Health

- I10 - General

- I12 - Health Behavior

- I15 - Health and Economic Development

- I18 - Government Policy; Regulation; Public Health

- Browse content in I2 - Education and Research Institutions

- I20 - General

- I21 - Analysis of Education

- I22 - Educational Finance; Financial Aid

- I24 - Education and Inequality

- I25 - Education and Economic Development

- I28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in I3 - Welfare, Well-Being, and Poverty

- I30 - General

- I31 - General Welfare

- I32 - Measurement and Analysis of Poverty

- I38 - Government Policy; Provision and Effects of Welfare Programs

- Browse content in J - Labor and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in J0 - General

- J01 - Labor Economics: General

- J08 - Labor Economics Policies

- Browse content in J1 - Demographic Economics

- J10 - General

- J11 - Demographic Trends, Macroeconomic Effects, and Forecasts

- J12 - Marriage; Marital Dissolution; Family Structure; Domestic Abuse

- J13 - Fertility; Family Planning; Child Care; Children; Youth

- J15 - Economics of Minorities, Races, Indigenous Peoples, and Immigrants; Non-labor Discrimination

- J16 - Economics of Gender; Non-labor Discrimination

- J17 - Value of Life; Forgone Income

- J18 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J2 - Demand and Supply of Labor

- J21 - Labor Force and Employment, Size, and Structure

- J22 - Time Allocation and Labor Supply

- J23 - Labor Demand

- J24 - Human Capital; Skills; Occupational Choice; Labor Productivity

- J26 - Retirement; Retirement Policies

- J28 - Safety; Job Satisfaction; Related Public Policy

- Browse content in J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor Costs

- J38 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J4 - Particular Labor Markets

- J48 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J5 - Labor-Management Relations, Trade Unions, and Collective Bargaining

- J58 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J6 - Mobility, Unemployment, Vacancies, and Immigrant Workers

- J61 - Geographic Labor Mobility; Immigrant Workers

- J62 - Job, Occupational, and Intergenerational Mobility

- J63 - Turnover; Vacancies; Layoffs

- J68 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J8 - Labor Standards: National and International

- J88 - Public Policy

- Browse content in K - Law and Economics

- Browse content in K2 - Regulation and Business Law

- K23 - Regulated Industries and Administrative Law

- Browse content in K3 - Other Substantive Areas of Law

- K34 - Tax Law

- Browse content in K4 - Legal Procedure, the Legal System, and Illegal Behavior

- K40 - General

- K42 - Illegal Behavior and the Enforcement of Law

- Browse content in L - Industrial Organization

- Browse content in L1 - Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance

- L11 - Production, Pricing, and Market Structure; Size Distribution of Firms

- L14 - Transactional Relationships; Contracts and Reputation; Networks

- L16 - Industrial Organization and Macroeconomics: Industrial Structure and Structural Change; Industrial Price Indices

- Browse content in L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and Behavior

- L20 - General

- L23 - Organization of Production

- L25 - Firm Performance: Size, Diversification, and Scope

- L26 - Entrepreneurship

- Browse content in L3 - Nonprofit Organizations and Public Enterprise

- L33 - Comparison of Public and Private Enterprises and Nonprofit Institutions; Privatization; Contracting Out

- Browse content in L5 - Regulation and Industrial Policy

- L51 - Economics of Regulation

- L52 - Industrial Policy; Sectoral Planning Methods

- Browse content in L9 - Industry Studies: Transportation and Utilities

- L94 - Electric Utilities

- L97 - Utilities: General

- L98 - Government Policy

- Browse content in M - Business Administration and Business Economics; Marketing; Accounting; Personnel Economics

- Browse content in M5 - Personnel Economics

- M53 - Training

- Browse content in N - Economic History

- Browse content in N3 - Labor and Consumers, Demography, Education, Health, Welfare, Income, Wealth, Religion, and Philanthropy

- N35 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in N5 - Agriculture, Natural Resources, Environment, and Extractive Industries

- N55 - Asia including Middle East

- N57 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N7 - Transport, Trade, Energy, Technology, and Other Services

- N77 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in O - Economic Development, Innovation, Technological Change, and Growth

- Browse content in O1 - Economic Development

- O10 - General

- O11 - Macroeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O12 - Microeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O13 - Agriculture; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Other Primary Products

- O14 - Industrialization; Manufacturing and Service Industries; Choice of Technology

- O15 - Human Resources; Human Development; Income Distribution; Migration

- O16 - Financial Markets; Saving and Capital Investment; Corporate Finance and Governance

- O17 - Formal and Informal Sectors; Shadow Economy; Institutional Arrangements

- O18 - Urban, Rural, Regional, and Transportation Analysis; Housing; Infrastructure

- O19 - International Linkages to Development; Role of International Organizations

- Browse content in O2 - Development Planning and Policy

- O20 - General

- O22 - Project Analysis

- O23 - Fiscal and Monetary Policy in Development

- O24 - Trade Policy; Factor Movement Policy; Foreign Exchange Policy

- O25 - Industrial Policy

- Browse content in O3 - Innovation; Research and Development; Technological Change; Intellectual Property Rights

- O31 - Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives

- O32 - Management of Technological Innovation and R&D

- O33 - Technological Change: Choices and Consequences; Diffusion Processes

- O34 - Intellectual Property and Intellectual Capital

- O38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in O4 - Economic Growth and Aggregate Productivity

- O40 - General

- O41 - One, Two, and Multisector Growth Models

- O43 - Institutions and Growth

- O47 - Empirical Studies of Economic Growth; Aggregate Productivity; Cross-Country Output Convergence

- Browse content in O5 - Economywide Country Studies

- O55 - Africa

- O57 - Comparative Studies of Countries

- Browse content in P - Economic Systems

- Browse content in P1 - Capitalist Systems

- P14 - Property Rights

- Browse content in P2 - Socialist Systems and Transitional Economies

- P26 - Political Economy; Property Rights

- Browse content in P3 - Socialist Institutions and Their Transitions

- P30 - General

- Browse content in P4 - Other Economic Systems

- P43 - Public Economics; Financial Economics

- P48 - Political Economy; Legal Institutions; Property Rights; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Regional Studies

- Browse content in Q - Agricultural and Natural Resource Economics; Environmental and Ecological Economics

- Browse content in Q0 - General

- Q01 - Sustainable Development

- Browse content in Q1 - Agriculture

- Q10 - General

- Q12 - Micro Analysis of Farm Firms, Farm Households, and Farm Input Markets

- Q13 - Agricultural Markets and Marketing; Cooperatives; Agribusiness

- Q14 - Agricultural Finance

- Q15 - Land Ownership and Tenure; Land Reform; Land Use; Irrigation; Agriculture and Environment

- Q16 - R&D; Agricultural Technology; Biofuels; Agricultural Extension Services

- Q17 - Agriculture in International Trade

- Q18 - Agricultural Policy; Food Policy

- Browse content in Q2 - Renewable Resources and Conservation

- Q25 - Water

- Browse content in Q3 - Nonrenewable Resources and Conservation

- Q33 - Resource Booms

- Browse content in Q4 - Energy

- Q43 - Energy and the Macroeconomy

- Browse content in Q5 - Environmental Economics

- Q51 - Valuation of Environmental Effects

- Q52 - Pollution Control Adoption Costs; Distributional Effects; Employment Effects

- Q54 - Climate; Natural Disasters; Global Warming

- Q56 - Environment and Development; Environment and Trade; Sustainability; Environmental Accounts and Accounting; Environmental Equity; Population Growth

- Q57 - Ecological Economics: Ecosystem Services; Biodiversity Conservation; Bioeconomics; Industrial Ecology

- Q58 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R - Urban, Rural, Regional, Real Estate, and Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R1 - General Regional Economics

- R11 - Regional Economic Activity: Growth, Development, Environmental Issues, and Changes

- R12 - Size and Spatial Distributions of Regional Economic Activity

- R13 - General Equilibrium and Welfare Economic Analysis of Regional Economies

- R14 - Land Use Patterns

- Browse content in R2 - Household Analysis

- R20 - General

- R23 - Regional Migration; Regional Labor Markets; Population; Neighborhood Characteristics

- R28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R3 - Real Estate Markets, Spatial Production Analysis, and Firm Location

- R38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R4 - Transportation Economics

- R40 - General

- R41 - Transportation: Demand, Supply, and Congestion; Travel Time; Safety and Accidents; Transportation Noise

- R48 - Government Pricing and Policy

- Browse content in R5 - Regional Government Analysis

- R52 - Land Use and Other Regulations

- Browse content in Y - Miscellaneous Categories

- Y8 - Related Disciplines

- Browse content in Z - Other Special Topics

- Browse content in Z1 - Cultural Economics; Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology

- Z13 - Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology; Social and Economic Stratification

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- About The World Bank Research Observer

- About the World Bank

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Privatization trends: stylized facts, the effects of privatization: efficiency and firm performance, privatization process: distributional impacts, policy implications, concluding comments.

- < Previous

Privatization in Developing Countries: What Are the Lessons of Recent Experience?

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Saul Estrin, Adeline Pelletier, Privatization in Developing Countries: What Are the Lessons of Recent Experience?, The World Bank Research Observer , Volume 33, Issue 1, February 2018, Pages 65–102, https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkx007

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This paper reviews the recent empirical evidence on privatization in developing countries, with particular emphasis on new areas of research such as the distributional impacts of privatization. Overall, the literature now reflects a more cautious and nuanced evaluation of privatization. Thus, private ownership alone is no longer argued to automatically generate economic gains in developing economies; pre-conditions (especially the regulatory infrastructure) and an appropriate process of privatization are important for attaining a positive impact. These comprise a list which is often challenging in developing countries: well-designed and sequenced reforms; the implementation of complementary policies; the creation of regulatory capacity; attention to poverty and social impacts; and strong public communication. Even so, the studies do identify the scope for efficiency-enhancing privatization that also promotes equity in developing countries.

There is a large body of literature about the economic effects of privatization. However, since it was mainly written in the 1990s, there was typically limited emphasis on issues which have come to the fore more recently, as well as more recent developments in the evidence about privatization itself, much of it from developing economies. This motivated us to write this paper, which summarizes the evidence about the impact of recent privatizations, not only in terms of firms’ efficiency but also with regard to the effects on income distribution. In addition, we are particularly attentive to the process of privatization in developing countries, notably with respect to the regulatory apparatus enabling successful privatization experiences.

When governments divested state-owned enterprises in developed economies, especially in the 1980s and 1990s, their objectives were usually to enhance economic efficiency by improving firm performance, to decrease government intervention and increase its revenue, and to introduce competition in monopolized sectors ( Vickers and Yarrow 1988 ). Much of the earlier evidence about the economic impact of privatization concerned these topics and was based on data from developed countries and later, transition countries. These findings have been brought together in two previous surveys, by Megginson and Netter (2001) and Estrin et al. (2009) respectively. The former assesses the findings of empirical research on the effects of privatization up to 2000, mainly from developed and middle-income countries, while the latter concentrates on transition economies including China, over the 1989 to 2006 period. 1 However, the experiences from the wave of privatizations that have occurred in developing countries before and since these studies warrant a new examination of the impact of privatization in the context of the development process.

The tone of the privatization debate has evolved in recent years in international financial institutions as privatization activity has shifted towards developing economies, and as a consequence of the difficulties of implementation and some privatization failures in the 1980s and 1990s ( Jomo 2008 ). As a result, more emphasis in policy-making is now being placed on creating the preconditions for successful privatization. Thus, in place of a simple pro-privatization bias characteristic of the Washington consensus ( Boycko, Shleifer, and Vishny 1995 ), it is now proposed that governments should first provide a better regulatory and institutional framework, including a well-functioning capital market and the protection of consumer and employee rights. In other words, context matters: ownership reforms should be tailor-made for the national economic circumstances, with strategies for privatization being adapted to local conditions. The traditional privatization objective of improving the efficiency of public enterprises also remains a major goal in developing countries, as does reducing the subsidies to state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

This article therefore reviews the recent evidence on privatization, with an emphasis on developing countries. The first section presents some stylized facts. The next section examines the effects of privatization in terms of firms’ efficiency and performance. In the following section, we go on to examine the distributional impacts of privatization. Policy recommendations are developed in the final section.

Privatization Trends Since the Late 1980s

The data on privatization prior to 2008 (with a regional breakdown) is sourced from the World Bank Privatization database but unfortunately this was discontinued in 2008 and no consolidated data is available after that date. Since we have not been able to find disaggregated data post-2008, we therefore present world aggregates, based on the Privatization Barometer database.

The early literature focused on developed economies and Western Europe represented roughly one-third of global privatization proceeds over the period 1977 to 2002 ( Roland 2008 ). Even so, many of these deals only concerned minority stakes of SOEs ( Bortolotti and Milella 2008 ). There were also spectacular numbers of privatizations during the transition process after 1990 in Central and Eastern Europe, with proceeds totaling $240 billion to 2008, in addition to widespread free or subsidized allocation of shares in former SOEs ( Estrin et al. 2009 ). The revenues from privatization have been more limited in Africa, the Middle East and South Asia, with total proceeds below $50 billion for each (see figure 1 ). 2 However, proceeds are on par with or above Europe once they are expressed as a percentage of GDP.

Value of privatisation transactions in developing countries by region, 1988 to 2008

Source: World Bank, Privatization database. Note: comparable data not available after 2008.

For the rest of Asia, the picture is rather different. While South Asia has experienced only a limited number of privatizations (especially India), this was not the case in East Asia, where total privatization proceeds represented 30% of the world's total ($230 billion) over the 1988 to 2008 period. China, in particular, stands out. Over a 25-year period, the Chinese government has encouraged innovative forms of industrial ownership, especially at the subnational level, that combine elements of collective and private property ( Brandt and Rawski 2008 ). New private entry and foreign direct investment have also been encouraged. As a result, by the end of the 1990s, the non-state sector accounted for over 60% of GDP and state enterprises’ share in industrial output had declined from 78% in 1978 to 28% in 1999 ( Kikeri and Nellis 2004 ). The OECD estimated the state-owned share of GDP had further declined to 29.7% by 2006 ( Lee 2009 ).

Finally, in Latin America and especially in Chile, large-scale privatization programs have been launched, especially in the infrastructure sector, starting in 1974 in Chile and peaking in the 1990s. Between 1988 and 2008, the total privatization proceeds in Latin America amounted to $220 billion (28% of total world proceeds).

One needs to be cautious, however, when interpreting the raw data because of differences in the size of economies. The differences between the privatization experience of Africa, Asia, and Europe become less striking when proceeds are normalized by GDP, though privatization revenue to GDP is high in Latin America, representing, on average, 0.5% of GDP over the period.

Privatization Trends Since 2008

The five years to 2015 have been marked by the predominant role of China in global privatizations, while the EU's share has been below its long-term average of 45% of the world's total proceeds, running at only one-third of worldwide totals, on average. According to the Privatization Barometer (PB) Report 2013–2014, global privatization total proceeds exceeded $1.1 trillion from January 2009 to November 2014, with $544 billion of divested assets between January 2012 and November 2014. 3

In addition, the 20-month period beginning in January 2014 witnessed privatizations totaling $431.4 billion ( PB report 2015 ). This is far more than any comparable period since the beginning of the privatization programs in the U.K. in the late 1970s (see figure 2 ), though as noted below, a significant part of this was driven by the unwinding of positions taken in banks by governments during the financial crisis.

Worldwide Privatization Revenues 1988 to 2015 (billions of USD)

Note: 2015 is an estimate as August 30, 2015. Source: Privatization Barometer Available at: http://www.privatizationbarometer.com/ .

Indian Revenues from Privatization

Source: World Bank Privatization database.

China has consistently been one of the top privatizers from 2009 to 2015; it was the second-largest privatizer in 2009 and the first in 2013, 2014, as well as the 8-month period of January to August 2015. Aggregate privatization deals in China totaled more than $40 billion in both 2013 and 2014 and a spectacular $133.3 billion in the first eight months of 2015 through 247 sales. The bulk of these privatization revenues came from the public and private placement offering of primary shares by SOEs ( PB report 2015 ). However, the state's equity ownership stake was generally only reduced indirectly, by increasing the total number of shares outstanding ( PB report 2015 ). In fact, Hsieh and Song (2015) have shown that almost half of the state-owned firms in 2007 and nearly 60 percent of them in 2012 were legally registered as private firms. The term used in China for this ownership change is that the large state-owned firms are “corporatized” rather than privatized. The typical form this “corporatization” takes is that of a minority share traded in the stock market and merged into a large state-owned conglomerate, the controlling shareholder ( Hsieh and Song 2015 ).

The next-leading country in terms of privatization proceeds after China is the United Kingdom, but it is far behind, with total proceeds of $17.2 billion in 2014 (against $7.8 billion in 2009).

In the EU as a whole, with countries addressing their government deficits post-2008, privatization proceeds rose to a five-year peak in 2013, to $68.0 billion, and a nine-year peak of $77.6 billion in 2014, while the annualized value of privatizations during 2015 (based on the first 8 months) reached $63.3 billion. This represents more than one-third of the global annual totals in 2014, but is only 20.0% of worldwide totals in the first 8 months of 2015, and lower than the long-run average EU share of about 44.6% ( PB report 2015 ). This relative decline of EU privatization proceeds is also reflected in the fact that China alone generated revenues from privatization almost as great as did the EU countries combined during 2015 ($68.0 billion versus $77.6 billion for China; PB report 2015 ).

China and India were the two top emerging countries by total privatization revenues in 2015. The five largest single deals outside the developed world in 2014 were realized in China, with the recapitalization and primary share offering of CITIC Pacific Ltd, the private placement of BOE Technology Group, the primary-share initial public offering (IPO) of Dalian Wanda Commercial, and finally the primary-share IPO of CGN Power and of HK Electrical Investments Ltd.

In the following section, we focus on the privatization experience in Africa and South Asia. While the privatization programs in Eastern Europe, China, and Latin America are among the most important in terms of total proceeds, a rich literature already exists discussing them (see Estrin et al. 2009 on transition economies and Estache and Trujillo 2008 on Latin America). Moreover, while privatization in Latin America and Eastern Europe culminated in the 1990s, much privatization in Africa and South Asia is more recent ( Roland 2008 ).

Privatization Patterns in Africa: A Few Countries Only

Privatization programs in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) occurred in successive waves, with some countries privatizing much earlier than others ( Bennell 1997 ). The first group to start such programs in the late 1970s to early 1980s was composed of francophone West African countries (e.g., Benin, Guinea, Niger, Senegal, and Togo) but their progress was limited. The second group, both Anglophone and Francophone countries (Ghana, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, Mali, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Madagascar, and Uganda), started privatizing in the late 1980s. These programs were often influenced by pressure from the international financial institutions ( Nellis 2008 ) though, as noted by Bennell (1997) , no significant progress was made anywhere except Nigeria until the late 1990s. The final group, the “late starters”, did not begin to privatize until the early to mid-1990s. Among this group, Tanzania, Burkina Faso and Zambia have shown a strong political commitment to privatization, whereas in the other three countries (Cameroon, Ethiopia, and Sierra Leone), only minimal progress was made in the 1990s.

Privatization in the 1990s: A Slow Start.

Only a minority of SOEs in SSA were subject to privatization over the period 1991 to 2001, and very little privatization has taken place outside of South Africa, Ghana, Nigeria, Zambia, and Cote d'Ivoire ( Nellis 2008 ). African states have privatized a smaller percentage (around 40%) of their SOEs than in Latin America and the transition economies ( Nellis 2008 ). In addition, privatization has generally concerned smaller manufacturing, industrial, or service firms. Bennell (1997) also reports that smaller SOEs were usually targeted during the initial stages of privatization programs in SSA because they were easier to sell. Five industries in particular were prominent in most programs: food processing, alcoholic beverages, textiles, cement and other non-metallic products, and metal products. These industries accounted for 60% of the total proceeds from the sale of manufacturing SOEs during 1988 to 1995 ( Bennell 1997 ), if we exclude the exceptional and large sale of ISCOR (Iron and Steel Industrial Corporation) in South Africa.

Bennell (1997) explains that the slow progress in privatization in the 1990s was due to a lack of political commitment compounded by strong opposition from entrenched vested interests (senior bureaucrats in ministries and SOEs themselves, as well as public sector workers concerned about their job security). For instance, in Cameroon, only five of the thirty SOEs scheduled for privatization were sold by the end of 1995. In other countries such as Nigeria, the privatization program started well but then stalled. Despite the fact that Nigeria's program had been one of the most successful in SSA in the 1990s, it was suspended in early 1995 in favor of a mass program of “commercialization”. In Madagascar, the privatization program was also suspended in mid-1993 due to serious mismanagement and its subsequent unpopularity. In addition, Bennell (1997) reports that there were nationalist concerns about the possible political and economic consequences of increased foreign ownership as a result of privatization.

However, in the late 1990s, certain political constraints lifted. First, a growing number of governments in SSA started to undertake significant economic reforms, under the aegis of the World Bank and the IMF, in which privatization was an integral part. Reforms and privatization were also progressively being accepted by the population. In addition, important political liberalization, with multi-party elections, broke with the previous statist policies, and created some room for maneuver to implement privatization programs. Finally, the weak financial position of SOEs in many SSA countries and their rapid deterioration, in conjunction with the fiscal crisis the state experienced in the 1990s, also opened the way for a sell-off of SOEs to raise government revenues and reduce expenditures.

Despite this stronger commitment, Nellis (2008) notes that there were actually only a few privatization deals in Africa in the 1990s, mainly in infrastructure, and even in these the state retained significant minority stakes; around one-third of the shares on average were retained. Between 1988 and 1999, the total proceeds from privatization in SSA amounted to $9.8 billion, with the manufacturing and services sector accounting for 36% of the total, infrastructure 28%, the energy sector 17%, the primary sector 14%, and the financial (and other) sector 6% (see World Bank Privatization Database).

The Early to Mid-2000s; More Rapid Progress.

There were some important privatizations in SSA between 2000 and 2008, and total proceeds increased to $12.654 billion (see World Bank Privatization Database). Nigeria comprised 51% of this amount, followed by Kenya (10%), Ghana (9%) and South Africa (6%). Infrastructure 4 represented 73% of the total amount of the deals, followed by the manufacturing and services sector 5 (17%), the financial sector 6 (6%), energy 7 (4%) and the primary sector 8 (1%; see World Bank Privatization Database).

Privatization Post-2008: A Slowdown.

Privatization activity slowed in SSA with the economic downturn after 2008. One notable exception was Benin, with the privatization of the cotton and the public utility sectors. The concession for the operation of the container terminal of the Port of Cotonou and the majority stake in the cement company were awarded to a strategic private investor in September 2009 and March 2010, respectively, and the privatization of Benin Telecom was launched in 2009 (this is still ongoing; IMF 2010 ). Nigeria was also notable for its sale of 15 electricity-generating and distribution companies in 2013, raising $2.50 billion (see Megginson 2014 ). In Chad, the government announced in 2015 that it was re-launching the sale of 80% of Société des Telecommunications du Tchad (Sotel-Tchad), after the previous attempt collapsed in 2010. Because the World Bank Privatization Database does not have data on privatization after 2008, one cannot compare the aggregated privatization proceeds post-2008 to those of earlier decades.

Privatization in South Asia: A Slow Opening

Privatizations in South Asia have traditionally been rare, despite the notable inefficiency of SOEs ( Gupta 2008 ). The governments’ reluctance to privatize can be partly explained historically, with the government's close involvement in the establishment of an industrial base in the postcolonial era, especially in India ( Gupta 2008 ). Particular sectors had been reserved exclusively for SOEs, such as the infrastructure sector and capital goods and raw materials industries such as steel, petroleum, and heavy machinery. In addition, the government nationalized many loss-making private companies; more than half of the firms owned by the Indian federal government were loss-making in the 1990s.

Following the balance of payment crisis of 1991, the Indian government implemented a series of reforms under the Industrial Policy Resolution of 1991 to encourage private enterprise. Privatization was initiated mainly through two approaches: partial privatization and strategic sales. However, the former was very limited, with the government selling only minority equity stakes until 2000, and without transferring management control. Political uncertainty prevented the emergence of a coherent privatization policy. Majority stakes sales and the transfer of management control were only conducted after the elections of 1999, and even then, until 2004 the government retained an average ownership stake of 82% in all SOEs ( Gupta 2008 ).

The stalled privatization program was revived in 2010 with a secondary offering of shares in National Thermal Power Corporation Ltd (NTPC), which owns 20% of India's power generation capacity ( Gupta 2009 ). However, the sale of the $1.85 billion block of shares only reduced the government's stake by an additional 5%, leaving 85% still under government control. In addition, the process of privatization was viewed as poor, with the secondary offering subscribed only 1.2 times, and even this after assistance from government-owned financial institutions.