Research Objectives: The Compass of Your Study

Table of contents

- 1 Definition and Purpose of Setting Clear Research Objectives

- 2 How Research Objectives Fit into the Overall Research Framework

- 3 Types of Research Objectives

- 4 Aligning Objectives with Research Questions and Hypotheses

- 5 Role of Research Objectives in Various Research Phases

- 6.1 Key characteristics of well-defined research objectives

- 6.2 Step-by-Step Guide on How to Formulate Both General and Specific Research Objectives

- 6.3 How to Know When Your Objectives Need Refinement

- 7 Research Objectives Examples in Different Fields

- 8 Conclusion

Embarking on a research journey without clear objectives is like navigating the sea without a compass. This article delves into the essence of establishing precise research objectives, serving as the guiding star for your scholarly exploration.

We will unfold the layers of how the objective of study not only defines the scope of your research but also directs every phase of the research process, from formulating research questions to interpreting research findings. By bridging theory with practical examples, we aim to illuminate the path to crafting effective research objectives that are both ambitious and attainable. Let’s chart the course to a successful research voyage, exploring the significance, types, and formulation of research paper objectives.

Definition and Purpose of Setting Clear Research Objectives

Defining the research objectives includes which two tasks? Research objectives are clear and concise statements that outline what you aim to achieve through your study. They are the foundation for determining your research scope, guiding your data collection methods, and shaping your analysis. The purpose of research proposal and setting clear objectives in it is to ensure that your research efforts are focused and efficient, and to provide a roadmap that keeps your study aligned with its intended outcomes.

To define the research objective at the outset, researchers can avoid the pitfalls of scope creep, where the study’s focus gradually broadens beyond its initial boundaries, leading to wasted resources and time. Clear objectives facilitate communication with stakeholders, such as funding bodies, academic supervisors, and the broader academic community, by succinctly conveying the study’s goals and significance. Furthermore, they help in the formulation of precise research questions and hypotheses, making the research process more systematic and organized. Yet, it is not always easy. For this reason, PapersOwl is always ready to help. Lastly, clear research objectives enable the researcher to critically assess the study’s progress and outcomes against predefined benchmarks, ensuring the research stays on track and delivers meaningful results.

How Research Objectives Fit into the Overall Research Framework

Research objectives are integral to the research framework as the nexus between the research problem, questions, and hypotheses. They translate the broad goals of your study into actionable steps, ensuring every aspect of your research is purposefully aligned towards addressing the research problem. This alignment helps in structuring the research design and methodology, ensuring that each component of the study is geared towards answering the core questions derived from the objectives. Creating such a difficult piece may take a lot of time. If you need it to be accurate yet fast delivered, consider getting professional research paper writing help whenever the time comes. It also aids in the identification and justification of the research methods and tools used for data collection and analysis, aligning them with the objectives to enhance the validity and reliability of the findings.

Furthermore, by setting clear objectives, researchers can more effectively evaluate the impact and significance of their work in contributing to existing knowledge. Additionally, research objectives guide literature review, enabling researchers to focus their examination on relevant studies and theoretical frameworks that directly inform their research goals.

Types of Research Objectives

In the landscape of research, setting objectives is akin to laying down the tracks for a train’s journey, guiding it towards its destination. Constructing these tracks involves defining two main types of objectives: general and specific. Each serves a unique purpose in guiding the research towards its ultimate goals, with general objectives providing the broad vision and specific objectives outlining the concrete steps needed to fulfill that vision. Together, they form a cohesive blueprint that directs the focus of the study, ensuring that every effort contributes meaningfully to the overarching research aims.

- General objectives articulate the overarching goals of your study. They are broad, setting the direction for your research without delving into specifics. These objectives capture what you wish to explore or contribute to existing knowledge.

- Specific objectives break down the general objectives into measurable outcomes. They are precise, detailing the steps needed to achieve the broader goals of your study. They often correspond to different aspects of your research question , ensuring a comprehensive approach to your study.

To illustrate, consider a research project on the impact of digital marketing on consumer behavior. A general objective might be “to explore the influence of digital marketing on consumer purchasing decisions.” Specific objectives could include “to assess the effectiveness of social media advertising in enhancing brand awareness” and “to evaluate the impact of email marketing on customer loyalty.”

Aligning Objectives with Research Questions and Hypotheses

The harmony between what research objectives should be, questions, and hypotheses is critical. Objectives define what you aim to achieve; research questions specify what you seek to understand, and hypotheses predict the expected outcomes.

This alignment ensures a coherent and focused research endeavor. Achieving it necessitates a thoughtful consideration of how each component interrelates, ensuring that the objectives are not only ambitious but also directly answerable through the research questions and testable via the hypotheses. This interconnectedness facilitates a streamlined approach to the research process, enabling researchers to systematically address each aspect of their study in a logical sequence. Moreover, it enhances the clarity and precision of the research, making it easier for peers and stakeholders to grasp the study’s direction and potential contributions.

Role of Research Objectives in Various Research Phases

Throughout the research process, objectives guide your choices and strategies – from selecting the appropriate research design and methods to analyzing data and interpreting results. They are the criteria against which you measure the success of your study. In the initial stages, research objectives inform the selection of a topic, helping to narrow down a broad area of interest into a focused question that can be explored in depth. During the methodology phase, they dictate the type of data needed and the best methods for obtaining that data, ensuring that every step taken is purposeful and aligned with the study’s goals. As the research progresses, objectives provide a framework for analyzing the collected data, guiding the researcher in identifying patterns, drawing conclusions, and making informed decisions.

Crafting Effective Research Objectives

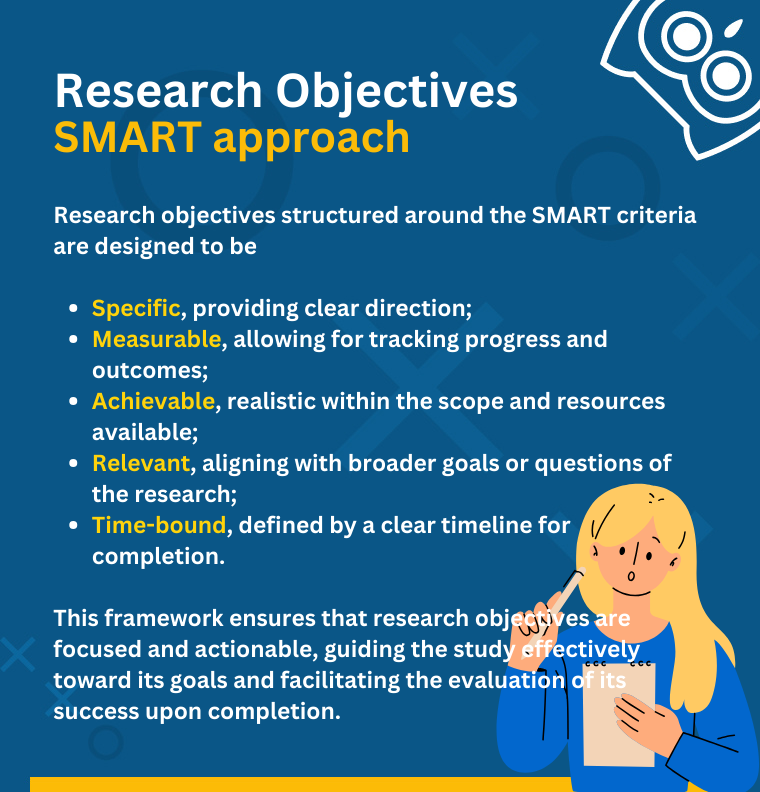

The effective objective of research is pivotal in laying the groundwork for a successful investigation. These objectives clarify the focus of your study and determine its direction and scope. Ensuring that your objectives are well-defined and aligned with the SMART criteria is crucial for setting a strong foundation for your research.

Key characteristics of well-defined research objectives

Well-defined research objectives are characterized by the SMART criteria – Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. Specific objectives clearly define what you plan to achieve, eliminating any ambiguity. Measurable objectives allow you to track progress and assess the outcome. Achievable objectives are realistic, considering the research sources and time available. Relevant objectives align with the broader goals of your field or research question. Finally, Time-bound objectives have a clear timeline for completion, adding urgency and a schedule to your work.

Step-by-Step Guide on How to Formulate Both General and Specific Research Objectives

So lets get to the part, how to write research objectives properly?

- Understand the issue or gap in existing knowledge your study aims to address.

- Gain insights into how similar challenges have been approached to refine your objectives.

- Articulate the broad goal of research based on your understanding of the problem.

- Detail the specific aspects of your research, ensuring they are actionable and measurable.

How to Know When Your Objectives Need Refinement

Your objectives of research may require refinement if they lack clarity, feasibility, or alignment with the research problem. If you find yourself struggling to design experiments or methods that directly address your objectives, or if the objectives seem too broad or not directly related to your research question, it’s likely time for refinement. Additionally, objectives in research proposal that do not facilitate a clear measurement of success indicate a need for a more precise definition. Refinement involves ensuring that each objective is specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound, enhancing your research’s overall focus and impact.

Research Objectives Examples in Different Fields

The application of research objectives spans various academic disciplines, each with its unique focus and methodologies. To illustrate how the objectives of the study guide a research paper across different fields, here are some research objective examples:

- In Health Sciences , a research aim may be to “determine the efficacy of a new vaccine in reducing the incidence of a specific disease among a target population within one year.” This objective is specific (efficacy of a new vaccine), measurable (reduction in disease incidence), achievable (with the right study design and sample size), relevant (to public health), and time-bound (within one year).

- In Environmental Studies , the study objectives could be “to assess the impact of air pollution on urban biodiversity over a decade.” This reflects a commitment to understanding the long-term effects of human activities on urban ecosystems, emphasizing the need for sustainable urban planning.

- In Economics , an example objective of a study might be “to analyze the relationship between fiscal policies and unemployment rates in developing countries over the past twenty years.” This seeks to explore macroeconomic trends and inform policymaking, highlighting the role of economic research study in societal development.

These examples of research objectives describe the versatility and significance of research objectives in guiding scholarly inquiry across different domains. By setting clear, well-defined objectives, researchers can ensure their studies are focused and impactful and contribute valuable knowledge to their respective fields.

Defining research studies objectives and problem statement is not just a preliminary step, but a continuous guiding force throughout the research journey. These goals of research illuminate the path forward and ensure that every stride taken is meaningful and aligned with the ultimate goals of the inquiry. Whether through the meticulous application of the SMART criteria or the strategic alignment with research questions and hypotheses, the rigor in crafting and refining these objectives underscores the integrity and relevance of the research. As scholars venture into the vast terrains of knowledge, the clarity, and precision of their objectives serve as beacons of light, steering their explorations toward discoveries that advance academic discourse and resonate with the broader societal needs.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

Research Aims and Objectives: The dynamic duo for successful research

Picture yourself on a road trip without a destination in mind — driving aimlessly, not knowing where you’re headed or how to get there. Similarly, your research is navigated by well-defined research aims and objectives. Research aims and objectives are the foundation of any research project. They provide a clear direction and purpose for the study, ensuring that you stay focused and on track throughout the process. They are your trusted navigational tools, leading you to success.

Understanding the relationship between research objectives and aims is crucial to any research project’s success, and we’re here to break it down for you in this article. Here, we’ll explore the importance of research aims and objectives, understand their differences, and delve into the impact they have on the quality of research.

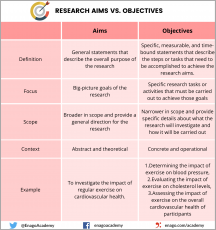

Understanding the Difference between Research Aims and Objectives

In research, aims and objectives are two important components but are often used interchangeably. Though they may sound similar, they are distinct and serve different purposes.

Research Aims:

Research aims are broad statements that describe the overall purpose of your study. They provide a general direction for your study and indicate the intended achievements of your research. Aims are usually written in a general and abstract manner describing the ultimate goal of the research.

Research Objectives:

Research objectives are specific, measurable, and achievable goals that you aim to accomplish within a specified timeframe. They break down the research aims into smaller, more manageable components and provide a clear picture of what you want to achieve and how you plan to achieve it.

In the example, the objectives provide specific targets that must be achieved to reach the aim. Essentially, aims provide the overall direction for the research while objectives provide specific targets that must be achieved to accomplish the aims. Aims provide a broad context for the research, while the objectives provide smaller steps that the researcher must take to accomplish the overall research goals. To illustrate, when planning a road trip, your research aim is the destination you want to reach, and your research objectives are the specific routes you need to take to get there.

Aims and objectives are interconnected. Objectives play a key role in defining the research methodology, providing a roadmap for how you’ll collect and analyze data, while aim is the final destination, which represents the ultimate goal of your research. By setting specific goals, you’ll be able to design a research plan that helps you achieve your objectives and, ultimately, your research aim.

Importance of Well-defined Aims and Objectives

The impact of clear research aims and objectives on the quality of research cannot be understated. But it’s not enough to simply have aims and objectives. Well-defined research aims and objectives are important for several reasons:

- Provides direction: Clear aims and well-defined objectives provide a specific direction for your research study, ensuring that the research stays focused on a specific topic or problem. This helps to prevent the research from becoming too broad or unfocused, and ensures that the study remains relevant and meaningful.

- Guides research design: The research aim and objectives help guide the research design and methodology, ensuring that your study is designed in a way that will answer the research questions and achieve the research objectives.

- Helps with resource allocation: Clear research aims and objectives helps you to allocate resources effectively , including time, financial resources, human resources, and other required materials. With a well-defined aim and objectives, you can identify the resources required to conduct the research, and allocate them in a way that maximizes efficiency and productivity.

- Assists in evaluation: Clearly specified research aims and objectives allow for effective evaluation of your research project’s success. You can assess whether the research has achieved its objectives, and whether the aim has been met. This evaluation process can help to identify areas of the research project that may require further attention or modification.

- Enhances communication: Well-defined research aims and objectives help to enhance communication among the research team, stakeholders, funding agencies, and other interested parties. Clear aims and objectives ensure that everyone involved in your research project understands the purpose and goals of the study. This can help to foster collaboration and ensure that everyone is working towards the same end goal.

How to Formulate Research Aims and Objectives

Formulating effective research aims and objectives involves a systematic process to ensure that they are clear, specific, achievable, and relevant. Start by asking yourself what you want to achieve through your research. What impact do you want your research to have? Once you have a clear understanding of your aims, you can then break them down into specific, achievable objectives. Here are some steps you can follow when developing research aims and objectives:

- Identify the research question : Clearly identify the questions you want to answer through your research. This will help you define the scope of your research. Understanding the characteristics of a good research question will help you generate clearer aims and objectives.

- Conduct literature review : When defining your research aim and objectives, it’s important to conduct a literature review to identify key concepts, theories, and methods related to your research problem or question. Conducting a thorough literature review can help you understand what research has been done in the area and what gaps exist in the literature.

- Identify the research aim: Develop a research aim that summarizes the overarching goal of your research. The research aim should be broad and concise.

- Develop research objectives: Based on your research questions and research aim, develop specific research objectives that outline what you intend to achieve through your research. These objectives should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART).

- Use action verbs: Use action verbs such as “investigate,” “examine,” “analyze,” and “compare” to describe your research aims and objectives. This makes them more specific and measurable.

- Ensure alignment with research question: Ensure that the research aim and objectives are aligned with the research question. This helps to ensure that the research remains focused and that the objectives are specific enough to answer your research question.

- Refine and revise: Once the research aim and objectives have been developed, refine and revise them as needed. Seek feedback from your colleagues, mentors, or supervisors to ensure that they are clear, concise, and achievable within the given resources and timeframe.

- Communicate: After finalizing the research aim and objectives, they should be communicated to the research team, stakeholders, and other interested parties. This helps to ensure that everyone is working towards the same end goal and understands the purpose of the study.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid While Formulating Aims and Objectives

There are several common mistakes that researchers can make when writing research aims and objectives. These include:

- Being too broad or vague: Aims and objectives that are too general or unclear can lead to confusion and lack of focus. It is important to ensure that the aims and objectives are concise and clear.

- Being too narrow or specific: On the other hand, aims and objectives that are too narrow or specific may limit the scope of the research and make it difficult to draw meaningful conclusions or implications.

- Being too ambitious: While it is important to aim high, being too ambitious with the aims and objectives can lead to unrealistic expectations and can be difficult to achieve within the constraints of the research project.

- Lack of alignment: The aims and objectives should be directly linked to the research questions being investigated. Otherwise, this will lead to a lack of coherence in the research project.

- Lack of feasibility: The aims and objectives should be achievable within the constraints of the research project, including time, budget, and resources. Failing to consider feasibility may cause compromise of the research quality.

- Failing to consider ethical considerations: The aims and objectives should take into account any ethical considerations, such as ensuring the safety and well-being of study participants.

- Failing to involve all stakeholders: It’s important to involve all relevant stakeholders, such as participants, supervisors, and funding agencies, in the development of the aims and objectives to ensure they are appropriate and relevant.

To avoid these common pitfalls, it is important to be specific, clear, relevant, and realistic when writing research aims and objectives. Seek feedback from colleagues or supervisors to ensure that the aims and objectives are aligned with the research problem , questions, and methodology, and are achievable within the constraints of the research project. It’s important to continually refine your aims and objectives as you go. As you progress in your research, it’s not uncommon for research aims and objectives to evolve slightly, but it’s important that they remain consistent with the study conducted and the research topic.

In summary, research aims and objectives are the backbone of any successful research project. They give you the ability to cut through the noise and hone in on what really matters. By setting clear goals and aligning them with your research questions and methodology, you can ensure that your research is relevant, impactful, and of the highest quality. So, before you hit the road on your research journey, make sure you have a clear destination and steps to get there. Let us know in the comments section below the challenges you faced and the strategies you followed while fomulating research aims and objectives! Also, feel free to reach out to us at any stage of your research or publication by using #AskEnago and tagging @EnagoAcademy on Twitter , Facebook , and Quora . Happy researching!

This particular material has added important but overlooked concepts regarding my experiences in explaining research aims and objectives. Thank you

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

Academic Essay Writing Made Simple: 4 types and tips

The pen is mightier than the sword, they say, and nowhere is this more evident…

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Improving Research Manuscripts Using AI-Powered Insights: Enago reports for effective research communication

Language Quality Importance in Academia AI in Evaluating Language Quality Enago Language Reports Live Demo…

- AI in Academia

- Trending Now

Simplifying the Literature Review Journey — A comparative analysis of 6 AI summarization tools

Imagine having to skim through and read mountains of research papers and books, only to…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for data interpretation

In research, choosing the right approach to understand data is crucial for deriving meaningful insights.…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right approach

The process of choosing the right research design can put ourselves at the crossroads of…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.1 The Purpose of Research Writing

Learning objectives.

- Identify reasons to research writing projects.

- Outline the steps of the research writing process.

Why was the Great Wall of China built? What have scientists learned about the possibility of life on Mars? What roles did women play in the American Revolution? How does the human brain create, store, and retrieve memories? Who invented the game of football, and how has it changed over the years?

You may know the answers to these questions off the top of your head. If you are like most people, however, you find answers to tough questions like these by searching the Internet, visiting the library, or asking others for information. To put it simply, you perform research.

Whether you are a scientist, an artist, a paralegal, or a parent, you probably perform research in your everyday life. When your boss, your instructor, or a family member asks you a question that you do not know the answer to, you locate relevant information, analyze your findings, and share your results. Locating, analyzing, and sharing information are key steps in the research process, and in this chapter, you will learn more about each step. By developing your research writing skills, you will prepare yourself to answer any question no matter how challenging.

Reasons for Research

When you perform research, you are essentially trying to solve a mystery—you want to know how something works or why something happened. In other words, you want to answer a question that you (and other people) have about the world. This is one of the most basic reasons for performing research.

But the research process does not end when you have solved your mystery. Imagine what would happen if a detective collected enough evidence to solve a criminal case, but she never shared her solution with the authorities. Presenting what you have learned from research can be just as important as performing the research. Research results can be presented in a variety of ways, but one of the most popular—and effective—presentation forms is the research paper . A research paper presents an original thesis, or purpose statement, about a topic and develops that thesis with information gathered from a variety of sources.

If you are curious about the possibility of life on Mars, for example, you might choose to research the topic. What will you do, though, when your research is complete? You will need a way to put your thoughts together in a logical, coherent manner. You may want to use the facts you have learned to create a narrative or to support an argument. And you may want to show the results of your research to your friends, your teachers, or even the editors of magazines and journals. Writing a research paper is an ideal way to organize thoughts, craft narratives or make arguments based on research, and share your newfound knowledge with the world.

Write a paragraph about a time when you used research in your everyday life. Did you look for the cheapest way to travel from Houston to Denver? Did you search for a way to remove gum from the bottom of your shoe? In your paragraph, explain what you wanted to research, how you performed the research, and what you learned as a result.

Research Writing and the Academic Paper

No matter what field of study you are interested in, you will most likely be asked to write a research paper during your academic career. For example, a student in an art history course might write a research paper about an artist’s work. Similarly, a student in a psychology course might write a research paper about current findings in childhood development.

Having to write a research paper may feel intimidating at first. After all, researching and writing a long paper requires a lot of time, effort, and organization. However, writing a research paper can also be a great opportunity to explore a topic that is particularly interesting to you. The research process allows you to gain expertise on a topic of your choice, and the writing process helps you remember what you have learned and understand it on a deeper level.

Research Writing at Work

Knowing how to write a good research paper is a valuable skill that will serve you well throughout your career. Whether you are developing a new product, studying the best way to perform a procedure, or learning about challenges and opportunities in your field of employment, you will use research techniques to guide your exploration. You may even need to create a written report of your findings. And because effective communication is essential to any company, employers seek to hire people who can write clearly and professionally.

Writing at Work

Take a few minutes to think about each of the following careers. How might each of these professionals use researching and research writing skills on the job?

- Medical laboratory technician

- Small business owner

- Information technology professional

- Freelance magazine writer

A medical laboratory technician or information technology professional might do research to learn about the latest technological developments in either of these fields. A small business owner might conduct research to learn about the latest trends in his or her industry. A freelance magazine writer may need to research a given topic to write an informed, up-to-date article.

Think about the job of your dreams. How might you use research writing skills to perform that job? Create a list of ways in which strong researching, organizing, writing, and critical thinking skills could help you succeed at your dream job. How might these skills help you obtain that job?

Steps of the Research Writing Process

How does a research paper grow from a folder of brainstormed notes to a polished final draft? No two projects are identical, but most projects follow a series of six basic steps.

These are the steps in the research writing process:

- Choose a topic.

- Plan and schedule time to research and write.

- Conduct research.

- Organize research and ideas.

- Draft your paper.

- Revise and edit your paper.

Each of these steps will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter. For now, though, we will take a brief look at what each step involves.

Step 1: Choosing a Topic

As you may recall from Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” , to narrow the focus of your topic, you may try freewriting exercises, such as brainstorming. You may also need to ask a specific research question —a broad, open-ended question that will guide your research—as well as propose a possible answer, or a working thesis . You may use your research question and your working thesis to create a research proposal . In a research proposal, you present your main research question, any related subquestions you plan to explore, and your working thesis.

Step 2: Planning and Scheduling

Before you start researching your topic, take time to plan your researching and writing schedule. Research projects can take days, weeks, or even months to complete. Creating a schedule is a good way to ensure that you do not end up being overwhelmed by all the work you have to do as the deadline approaches.

During this step of the process, it is also a good idea to plan the resources and organizational tools you will use to keep yourself on track throughout the project. Flowcharts, calendars, and checklists can all help you stick to your schedule. See Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” , Section 11.2 “Steps in Developing a Research Proposal” for an example of a research schedule.

Step 3: Conducting Research

When going about your research, you will likely use a variety of sources—anything from books and periodicals to video presentations and in-person interviews.

Your sources will include both primary sources and secondary sources . Primary sources provide firsthand information or raw data. For example, surveys, in-person interviews, and historical documents are primary sources. Secondary sources, such as biographies, literary reviews, or magazine articles, include some analysis or interpretation of the information presented. As you conduct research, you will take detailed, careful notes about your discoveries. You will also evaluate the reliability of each source you find.

Step 4: Organizing Research and the Writer’s Ideas

When your research is complete, you will organize your findings and decide which sources to cite in your paper. You will also have an opportunity to evaluate the evidence you have collected and determine whether it supports your thesis, or the focus of your paper. You may decide to adjust your thesis or conduct additional research to ensure that your thesis is well supported.

Remember, your working thesis is not set in stone. You can and should change your working thesis throughout the research writing process if the evidence you find does not support your original thesis. Never try to force evidence to fit your argument. For example, your working thesis is “Mars cannot support life-forms.” Yet, a week into researching your topic, you find an article in the New York Times detailing new findings of bacteria under the Martian surface. Instead of trying to argue that bacteria are not life forms, you might instead alter your thesis to “Mars cannot support complex life-forms.”

Step 5: Drafting Your Paper

Now you are ready to combine your research findings with your critical analysis of the results in a rough draft. You will incorporate source materials into your paper and discuss each source thoughtfully in relation to your thesis or purpose statement.

When you cite your reference sources, it is important to pay close attention to standard conventions for citing sources in order to avoid plagiarism , or the practice of using someone else’s words without acknowledging the source. Later in this chapter, you will learn how to incorporate sources in your paper and avoid some of the most common pitfalls of attributing information.

Step 6: Revising and Editing Your Paper

In the final step of the research writing process, you will revise and polish your paper. You might reorganize your paper’s structure or revise for unity and cohesion, ensuring that each element in your paper flows into the next logically and naturally. You will also make sure that your paper uses an appropriate and consistent tone.

Once you feel confident in the strength of your writing, you will edit your paper for proper spelling, grammar, punctuation, mechanics, and formatting. When you complete this final step, you will have transformed a simple idea or question into a thoroughly researched and well-written paper you can be proud of!

Review the steps of the research writing process. Then answer the questions on your own sheet of paper.

- In which steps of the research writing process are you allowed to change your thesis?

- In step 2, which types of information should you include in your project schedule?

- What might happen if you eliminated step 4 from the research writing process?

Key Takeaways

- People undertake research projects throughout their academic and professional careers in order to answer specific questions, share their findings with others, increase their understanding of challenging topics, and strengthen their researching, writing, and analytical skills.

- The research writing process generally comprises six steps: choosing a topic, scheduling and planning time for research and writing, conducting research, organizing research and ideas, drafting a paper, and revising and editing the paper.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Objectives – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Objectives – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Objectives

Research objectives refer to the specific goals or aims of a research study. They provide a clear and concise description of what the researcher hopes to achieve by conducting the research . The objectives are typically based on the research questions and hypotheses formulated at the beginning of the study and are used to guide the research process.

Types of Research Objectives

Here are the different types of research objectives in research:

- Exploratory Objectives: These objectives are used to explore a topic, issue, or phenomenon that has not been studied in-depth before. The aim of exploratory research is to gain a better understanding of the subject matter and generate new ideas and hypotheses .

- Descriptive Objectives: These objectives aim to describe the characteristics, features, or attributes of a particular population, group, or phenomenon. Descriptive research answers the “what” questions and provides a snapshot of the subject matter.

- Explanatory Objectives : These objectives aim to explain the relationships between variables or factors. Explanatory research seeks to identify the cause-and-effect relationships between different phenomena.

- Predictive Objectives: These objectives aim to predict future events or outcomes based on existing data or trends. Predictive research uses statistical models to forecast future trends or outcomes.

- Evaluative Objectives : These objectives aim to evaluate the effectiveness or impact of a program, intervention, or policy. Evaluative research seeks to assess the outcomes or results of a particular intervention or program.

- Prescriptive Objectives: These objectives aim to provide recommendations or solutions to a particular problem or issue. Prescriptive research identifies the best course of action based on the results of the study.

- Diagnostic Objectives : These objectives aim to identify the causes or factors contributing to a particular problem or issue. Diagnostic research seeks to uncover the underlying reasons for a particular phenomenon.

- Comparative Objectives: These objectives aim to compare two or more groups, populations, or phenomena to identify similarities and differences. Comparative research is used to determine which group or approach is more effective or has better outcomes.

- Historical Objectives: These objectives aim to examine past events, trends, or phenomena to gain a better understanding of their significance and impact. Historical research uses archival data, documents, and records to study past events.

- Ethnographic Objectives : These objectives aim to understand the culture, beliefs, and practices of a particular group or community. Ethnographic research involves immersive fieldwork and observation to gain an insider’s perspective of the group being studied.

- Action-oriented Objectives: These objectives aim to bring about social or organizational change. Action-oriented research seeks to identify practical solutions to social problems and to promote positive change in society.

- Conceptual Objectives: These objectives aim to develop new theories, models, or frameworks to explain a particular phenomenon or set of phenomena. Conceptual research seeks to provide a deeper understanding of the subject matter by developing new theoretical perspectives.

- Methodological Objectives: These objectives aim to develop and improve research methods and techniques. Methodological research seeks to advance the field of research by improving the validity, reliability, and accuracy of research methods and tools.

- Theoretical Objectives : These objectives aim to test and refine existing theories or to develop new theoretical perspectives. Theoretical research seeks to advance the field of knowledge by testing and refining existing theories or by developing new theoretical frameworks.

- Measurement Objectives : These objectives aim to develop and validate measurement instruments, such as surveys, questionnaires, and tests. Measurement research seeks to improve the quality and reliability of data collection and analysis by developing and testing new measurement tools.

- Design Objectives : These objectives aim to develop and refine research designs, such as experimental, quasi-experimental, and observational designs. Design research seeks to improve the quality and validity of research by developing and testing new research designs.

- Sampling Objectives: These objectives aim to develop and refine sampling techniques, such as probability and non-probability sampling methods. Sampling research seeks to improve the representativeness and generalizability of research findings by developing and testing new sampling techniques.

How to Write Research Objectives

Writing clear and concise research objectives is an important part of any research project, as it helps to guide the study and ensure that it is focused and relevant. Here are some steps to follow when writing research objectives:

- Identify the research problem : Before you can write research objectives, you need to identify the research problem you are trying to address. This should be a clear and specific problem that can be addressed through research.

- Define the research questions : Based on the research problem, define the research questions you want to answer. These questions should be specific and should guide the research process.

- Identify the variables : Identify the key variables that you will be studying in your research. These are the factors that you will be measuring, manipulating, or analyzing to answer your research questions.

- Write specific objectives: Write specific, measurable objectives that will help you answer your research questions. These objectives should be clear and concise and should indicate what you hope to achieve through your research.

- Use the SMART criteria: To ensure that your research objectives are well-defined and achievable, use the SMART criteria. This means that your objectives should be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound.

- Revise and refine: Once you have written your research objectives, revise and refine them to ensure that they are clear, concise, and achievable. Make sure that they align with your research questions and variables, and that they will help you answer your research problem.

Example of Research Objectives

Examples of research objectives Could be:

Research Objectives for the topic of “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Employment”:

- To investigate the effects of the adoption of AI on employment trends across various industries and occupations.

- To explore the potential for AI to create new job opportunities and transform existing roles in the workforce.

- To examine the social and economic implications of the widespread use of AI for employment, including issues such as income inequality and access to education and training.

- To identify the skills and competencies that will be required for individuals to thrive in an AI-driven workplace, and to explore the role of education and training in developing these skills.

- To evaluate the ethical and legal considerations surrounding the use of AI for employment, including issues such as bias, privacy, and the responsibility of employers and policymakers to protect workers’ rights.

When to Write Research Objectives

- At the beginning of a research project : Research objectives should be identified and written down before starting a research project. This helps to ensure that the project is focused and that data collection and analysis efforts are aligned with the intended purpose of the research.

- When refining research questions: Writing research objectives can help to clarify and refine research questions. Objectives provide a more concrete and specific framework for addressing research questions, which can improve the overall quality and direction of a research project.

- After conducting a literature review : Conducting a literature review can help to identify gaps in knowledge and areas that require further research. Writing research objectives can help to define and focus the research effort in these areas.

- When developing a research proposal: Research objectives are an important component of a research proposal. They help to articulate the purpose and scope of the research, and provide a clear and concise summary of the expected outcomes and contributions of the research.

- When seeking funding for research: Funding agencies often require a detailed description of research objectives as part of a funding proposal. Writing clear and specific research objectives can help to demonstrate the significance and potential impact of a research project, and increase the chances of securing funding.

- When designing a research study : Research objectives guide the design and implementation of a research study. They help to identify the appropriate research methods, sampling strategies, data collection and analysis techniques, and other relevant aspects of the study design.

- When communicating research findings: Research objectives provide a clear and concise summary of the main research questions and outcomes. They are often included in research reports and publications, and can help to ensure that the research findings are communicated effectively and accurately to a wide range of audiences.

- When evaluating research outcomes : Research objectives provide a basis for evaluating the success of a research project. They help to measure the degree to which research questions have been answered and the extent to which research outcomes have been achieved.

- When conducting research in a team : Writing research objectives can facilitate communication and collaboration within a research team. Objectives provide a shared understanding of the research purpose and goals, and can help to ensure that team members are working towards a common objective.

Purpose of Research Objectives

Some of the main purposes of research objectives include:

- To clarify the research question or problem : Research objectives help to define the specific aspects of the research question or problem that the study aims to address. This makes it easier to design a study that is focused and relevant.

- To guide the research design: Research objectives help to determine the research design, including the research methods, data collection techniques, and sampling strategy. This ensures that the study is structured and efficient.

- To measure progress : Research objectives provide a way to measure progress throughout the research process. They help the researcher to evaluate whether they are on track and meeting their goals.

- To communicate the research goals : Research objectives provide a clear and concise description of the research goals. This helps to communicate the purpose of the study to other researchers, stakeholders, and the general public.

Advantages of Research Objectives

Here are some advantages of having well-defined research objectives:

- Focus : Research objectives help to focus the research effort on specific areas of inquiry. By identifying clear research questions, the researcher can narrow down the scope of the study and avoid getting sidetracked by irrelevant information.

- Clarity : Clearly stated research objectives provide a roadmap for the research study. They provide a clear direction for the research, making it easier for the researcher to stay on track and achieve their goals.

- Measurability : Well-defined research objectives provide measurable outcomes that can be used to evaluate the success of the research project. This helps to ensure that the research is effective and that the research goals are achieved.

- Feasibility : Research objectives help to ensure that the research project is feasible. By clearly defining the research goals, the researcher can identify the resources required to achieve those goals and determine whether those resources are available.

- Relevance : Research objectives help to ensure that the research study is relevant and meaningful. By identifying specific research questions, the researcher can ensure that the study addresses important issues and contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

4 Research Essay

Jeffrey Kessler

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

- Construct a thesis based upon your research

- Use critical reading strategies to analyze your research

- Defend a position in relation to the range of ideas surrounding a topic

- Organize your research essay in order to logically support your thesis

I. Introduction

The goal of this book has been to help demystify research and inquiry through a series of genres that are part of the research process. Each of these writing projects—the annotated bibliography, proposal, literature review, and research essay—builds on each other. Research is an ongoing and evolving process, and each of these projects help you build towards the next.

In your annotated bibliography, you started your inquiry into a topic, reading widely to define the breadth of your inquiry. You recorded this by summarizing and/or evaluating the first sources you examined. In your proposal, you organized a plan and developed pointed questions to pursue and ideas to research. This provided a good sense of where you might continue to explore. In your literature review, you developed a sense of the larger conversations around your topic and assessed the state of existing research. During each of these writing projects, your knowledge of your topic grew, and you became much more informed about its key issues.

You’ve established a topic and assembled sources in conversation with one another. It’s now time to contribute to that conversation with your own voice. With so much of your research complete, you can now turn your focus to crafting a strong research essay with a clear thesis. Having the extensive knowledge that you have developed across the first three writing projects will allow you to think more about putting the pieces of your research together, rather than trying to do research at the same time that you are writing.

This doesn’t mean that you won’t need to do a little more research. Instead, you might need to focus strategically on one or two key pieces of information to advance your argument, rather than trying to learn about the basics of your topic.

But what about a thesis or argument? You may have developed a clear idea early in the process, or you might have slowly come across an important claim you want to defend or a critique you want to make as you read more into your topic. You might still not be sure what you want to argue. No matter where you are, this chapter will help you navigate the genre of the research essay. We’ll examine the basics of a good thesis and argument, different ways to use sources, and strategies to organize your essay.

While this chapter will focus on the kind of research essay you would write in the college classroom, the skills are broadly applicable. Research takes many different forms in the academic, professional, and public worlds. Depending on the course or discipline, research can mean a semester-long project for a class or a few years’ worth of research for an advanced degree. As you’ll see in the examples below, research can consist of a brief, two-page conclusion or a government report that spans hundreds of pages with an overwhelming amount of original data.

Above all else, good research is engaged with its audience to bring new ideas to light based on existing conversations. A good research essay uses the research of others to advance the conversation around the topic based on relevant facts, analysis, and ideas.

II. Rhetorical Considerations: Contributing to the Conversation

The word “essay” comes from the French word essayer , or “attempt.” In other words, an essay is an attempt—to prove or know or illustrate something. Through writing an essay, your ideas will evolve as you attempt to explore and think through complicated ideas. Some essays are more exploratory or creative, while some are straightforward reports about the kind of original research that happens in laboratories.

Most research essays attempt to argue a point about the material, information, and data that you have collected. That research can come from fieldwork, laboratories, archives, interviews, data mining, or just a lot of reading. No matter the sources you use, the thesis of a research essay is grounded in evidence that is compelling to the reader.

Where you described the conversation in your literature review, in your research essay you are contributing to that conversation with your own argument. Your argument doesn’t have to be an argument in the cable-news-social-media-shouting sense of the word. It doesn’t have to be something that immediately polarizes individuals or divides an issue into black or white. Instead, an argument for a research essay should be a claim, or, more specifically, a claim that requires evidence and analysis to support. This can take many different forms.

Example 4.1: Here are some different types of arguments you might see in a research essay:

- Critiquing a specific idea within a field

- Interrogating an assumption many people hold about an issue

- Examining the cause of an existing problem

- Identifying the effects of a proposed program, law, or concept

- Assessing a historical event in a new way

- Using a new method to evaluate a text or phenomenon

- Proposing a new solution to an existing problem

- Evaluating an existing solution and suggesting improvements

These are only a few examples of the kinds of approaches your argument might take. As you look at the research you have gathered throughout your projects, your ideas will have evolved. This is a natural part of the research process. If you had a fully formed argument before you did any research, then you probably didn’t have an argument based on strong evidence. Your research now informs your position and understanding, allowing you to form a stronger evidence-based argument.

Having a good idea about your thesis and your approach is an important step, but getting the general idea into specific words can be a challenge on its own. This is one of the most common challenges in writing: “I know what I want to say; I just don’t know how to say it.”

Example 4.2: Here are some sample thesis statements. Examine them and think about their arguments.

Whether you agree, disagree, or are just plain unsure about them, you can imagine that these statements require their authors to present evidence, offer context, and explain key details in order to argue their point.

- Artificial intelligence (AI) has the ability to greatly expand the methods and content of higher education, and though there are some transient shortcomings, faculty in STEM should embrace AI as a positive change to the system of student learning. In particular, AI can prove to close the achievement gap often found in larger lecture settings by providing more custom student support.

- I argue that while the current situation for undocumented college students remains tumultuous, there are multiple routes—through financial and social support programs like the Fearless Undocumented Alliance—that both universities and colleges can utilize to support students affected by the reality of DACA’s shortcomings.

While it can be argued that massive reform of the NCAA’s bylaws is needed in the long run, one possible immediate improvement exists in the form of student-athlete name, image, and likeness rights. The NCAA should amend their long-standing definition of amateurism and allow student athletes to pursue financial gains from the use of their names, images, and likenesses, as is the case with amateur Olympic athletes.

Each of these thesis statements identifies a critical conversation around a topic and establishes a position that needs evidence for further support. They each offer a lot to consider, and, as sentences, are constructed in different ways.

Some writing textbooks, like They Say, I Say (2017), offer convenient templates in which to fit your thesis. For example, it suggests a list of sentence constructions like “Although some critics argue X, I will argue Y” and “If we are right to assume X, then we must consider the consequences of Y.”

More Resources 4.1: Templates

Templates can be a productive start for your ideas, but depending on the writing situation (and depending on your audience), you may want to expand your thesis beyond a single sentence (like the examples above) or template. According to Amy Guptill in her book Writing in Col lege (2016) , a good thesis has four main elements (pp. 21-22). A good thesis:

- Makes a non-obvious claim

- Poses something arguable

- Provides well-specified details

- Includes broader implications

Consider the sample thesis statements above. Each one provides a claim that is both non-obvious and arguable. In other words, they present something that needs further evidence to support—that’s where all your research is going to come in. In addition, each thesis identifies specifics, whether these are teaching methods, support programs, or policies. As you will see, when you include those specifics in a thesis statement, they help project a starting point towards organizing your essay.

Finally, according to Guptill, a good thesis includes broader implications. A good thesis not only engages the specific details of its argument, but also leaves room for further consideration. As we have discussed before, research takes place in an ongoing conversation. Your well-developed essay and hard work won’t be the final word on this topic, but one of many contributions among other scholars and writers. It would be impossible to solve every single issue surrounding your topic, but a strong thesis helps us think about the larger picture. Here’s Guptill:

Putting your claims in their broader context makes them more interesting to your reader and more impressive to your professors who, after all, assign topics that they think have enduring significance. Finding that significance for yourself makes the most of both your paper and your learning. (p. 23)

Thinking about the broader implications will also help you write a conclusion that is better than just repeating your thesis (we’ll discuss this more below).

Example 4.3: Let’s look at an example from above:

This thesis makes a key claim about the rights of student athletes (in fact, shortly after this paper was written, NCAA athletes became eligible to profit from their own name, image, and likeness). It provides specific details, rather than just suggesting that student athletes should be able to make money. Furthermore, it provides broader context, even giving a possible model—Olympic athletes—to build an arguable case.

Remember, that just like your entire research project, your thesis will evolve as you write. Don’t be afraid to change some key terms or move some phrases and clauses around to play with the emphasis in your thesis. In fact, doing so implies that you have allowed the research to inform your position.

Example 4.4: Consider these examples about the same topic and general idea. How does playing around with organization shade the argument differently?

- Although William Dowling’s amateur college sports model reminds us that the real stakeholders are the student athletes themselves, he highlights that the true power over student athletes comes from the athletic directors, TV networks, and coaches who care more about profits than people.

- While William Dowling’s amateur college sports model reminds us that the real stakeholders in college athletics are not the athletic directors, TV networks, and coaches, but the students themselves, his plan does not seem feasible because it eliminates the reason many people care about student athletes in the first place: highly lucrative bowl games and March Madness.

- Although William Dowling’s amateur college sports model has student athletes’ best interests in mind, his proposal remains unfeasible because financial stakeholders in college athletics, like athletic directors, TV networks, and coaches, refuse to let go of their power.

When you look at the different versions of the thesis statements above, the general ideas remain the same, but you can imagine how they might unfold differently in a paper, and even how those papers might be structured differently. Even after you have a good version of your thesis, consider how it might evolve by moving ideas around or changing emphasis as you outline and draft your paper.

More Resources 4.2: Thesis Statements

Looking for some additional help on thesis statements? Try these resources:

- How to Write a Thesis Statement

- Writing Effective Thesis Statements.

Library Referral: Your Voice Matters!

(by Annie R. Armstrong)

If you’re embarking on your first major college research paper, you might be concerned about “getting it right.” How can you possibly jump into a conversation with the authors of books, articles, and more, who are seasoned experts in their topics and disciplines? The way they write might seem advanced, confusing, academic, irritating, and even alienating. Try not to get discouraged. There are techniques for working with scholarly sources to break them down and make them easier to work with (see How to Read a Scholarly Article ). A librarian can work with you to help you find a variety of source types that address your topic in a meaningful way, or that one specific source you may still be trying to track down.

Furthermore, scholarly experts are not the only voices welcome at the research table! This research paper and others to come are an invitation to you to join the conversation; your voice and lived experience give you one-of-a-kind expertise equipping you to make new inquiries and insights into your topic. Sure, you’ll need to wrestle how to interpret difficult academic texts and how to piece them together. That said, your voice is an integral and essential part of the puzzle. All of those scholarly experts started closer to where you are than you might think.

III. The Research Essay Across the Disciplines

Example 4.5: Academic and Professional Examples

These examples are meant to show you how this genre looks in other disciplines and professions. Make sure to follow the requirements for your own class or to seek out specific examples from your instructor in order to address the needs of your own assignment.

As you will see, different disciplines use language very differently, including citation practices, use of footnotes and endnotes, and in-text references. (Review Chapter 3 for citation practices as disciplinary conventions.) You may find some STEM research to be almost unreadable, unless you are already an expert in that field and have a highly developed knowledge of the key terms and ideas in that field. STEM fields often rely on highly technical language and assume a high level of knowledge in the field. Similarly, humanities research can be hard to navigate if you don’t have a significant background in the topic or material.

As we’ve discussed, highly specialized research assumes its readers are other highly specialized researchers. Unless you read something like The Journ al of American Medicine on a regular basis, you usually learn about scientific or medical breakthroughs when they are reported by another news outlet, where a reporter makes the highly technical language of a scientific discovery more accessible for non-specialists.

Even if you are not an expert in multiple disciplines of study, you will find that research essays contain a lot of similarities in their structure and organization. Most research essays have an abstract that summarizes the entire article at the beginning. Introductions provide the necessary setup for the article. Body sections can vary. Some essays include a literature review section that describes the state of research about the topic. Others might provide background or a brief history. Many essays in the sciences will have a methodology section that explains how the research was conducted, including details such as lab procedures, sample sizes, control populations, conditions, and survey questions. Others include long analyses of primary sources, sets of data, or archival documents. Most essays end with conclusions about what further research needs to be completed or what their research further implies.

As you examine some of the different examples, look at the variations in arguments and structures. Just as in reading research about your own topic, you don’t need to read each essay from start to finish. Browse through different sections and see the different uses of language and organization that are possible.

IV. Research Strategies: When is Enough?

At this point, you know a lot about your topic. You’ve done a lot of research to complete your first three writing projects, but when do you have enough sources and information to start writing? Really, it depends.

If you’re writing a dissertation, you may have spent months or years doing research and still feel like you need to do more or to wait a few months until that next new study is published. If you’re writing a research essay for a class, you probably have a schedule of due dates for drafts and workshops. Either way, it’s better to start drafting sooner rather than later. Part of doing research is trying on ideas and discovering things throughout the drafting process.

That’s why you’ve written the other projects along the way instead of just starting with a research essay. You’ve built a foundation of strong research to read about your topic in the annotated bibliography, planned your research in the proposal, and understood the conversations around your topic in the literature review. Now that you are working on your research essay, you are far enough along in the research process where you might need a few more sources, but you will most likely discover this as you are drafting your essay. In other words, get writing and trust that you’ll discover what you need along the way.

V. Reading Strategies: Forwarding and Countering

Using sources is necessary to a research essay, and it is essential to think about how you use them. At this point in your research, you have read, summarized, analyzed, and made connections across many sources. Think back to the literature review. In that genre, you used your sources to illustrate the major issues, topics, and/or concerns among your research. You used those sources to describe and make connections between them.

For your research essay, you are putting those sources to work in a different way: using them in service of supporting your own contribution to the conversation. According to Joseph Harris in his book Rewriting (2017), we read texts in order to respond to them: “drawing from, commenting on, adding to […] the works of others” (p. 2). The act of writing, according to Harris, takes place among the different texts we read and the ways we use them for our own projects. Whether a source provides factual information or complicated concepts, we use sources in different ways. Two key ways to do so for Harris are forwarding and countering .

Forwarding a text means taking the original concept or idea and applying it to a new context. Harris writes: “In forwarding a text you test the strength of its insights and the range and flexibility of its phrasings. You rewrite it through reusing some of its key concepts and phrasings” (pp. 38-39). This is common in a lot of research essays. In fact, Harris identifies different types of forwarding:

- Illustrating: using a source to explain a larger point

- Authorizing: appealing to another source for credibility

- Borrowing: taking a term or concept from one context or discipline and using it in a new one

- Extending: expanding upon a source or its implications

It’s not enough in a research essay to include just sources with which you agree. Countering a text means more than just disagreeing with it, but it allows you to do more with a text that might not initially support your argument. This can include for Harris:

- Arguing the other side: oftentimes called “including a naysayer” or addressing objections

- Uncovering values: examining assumptions within the text that might prove problematic or reveal interesting insights

- Dissenting: finding the problems in or the limits of an argument (p. 58)

While the categories above are merely suggestions, it is worth taking a moment to think a little more about sources with which you might disagree. The whole point of an argument is to offer a claim that needs to be proved and/or defended. Essential to this is addressing possible objections. What might be some of the doubts your reader may have? What questions might a reasonable person have about your argument? You will never convince every single person, but by addressing and acknowledging possible objections, you help build the credibility of your argument by showing how your own voice fits into the larger conversation—if other members of that conversation may disagree.

VI. Writing Strategies: Organizing and Outlining

At this point you likely have a draft of a thesis (or the beginnings of one) and a lot of research, notes, and three writing projects about your topic. How do you get from all of this material to a coherent research essay? The following section will offer a few different ideas about organizing your essay. Depending on your topic, discipline, or assignment, you might need to make some necessary adjustments along the way, depending on your audience. Consider these more as suggestions and prompts to help in the writing and drafting of your research essay.

Sometimes, we tend to turn our research essay into an enthusiastic book report: “Here are all the cool things I read about my topic this semester!” When you’ve spent a long time reading and thinking about a topic, you may feel compelled to include every piece of information you’ve found. This can quickly overwhelm your audience. Other times, we as writers may feel so overwhelmed with all of the things we want to say that we don’t know where to start.

Writers don’t all follow the same processes or strategies. What works for one person may not always work for another, and what worked in one writing situation (or class) may not be as successful in another. Regardless, it’s important to have a plan and to follow a few strategies to get writing. The suggestions below can help get you organized and writing quickly. If you’ve never tried some of these strategies before, it’s worth seeing how they will work for you.

Think in Sections, Not Paragraphs

For smaller papers, you might think about what you want to say in each of the five to seven paragraphs that paper might require. Sometimes writing instructors even tell students what each paragraph should include. For longer essays, it’s much easier to think about a research essay in sections, or as a few connected short papers. In a short essay, you might need a paragraph to provide background information about your topic, but in longer essays—like the ones you have read for your project—you will likely find that you need more than a single paragraph, sometimes a few pages.

You might think about the different types of sections you have encountered in the research you have already gathered. Those types of sections might include: introduction, background, the history of an issue, literature review, causes, effects, solutions, analysis, limits, etc. When you consider possible sections for your paper, ask yourself, “What is the purpose of this section?” Then you can start to think about the best way to organize that information into paragraphs for each section.

Build an Outline

After you have developed what you want to argue with your thesis (or at least a general sense of it), consider how you want to argue it. You know that you need to begin with an introduction (more on that momentarily). Then you’ll likely need a few sections that help lead your reader through your argument.

Your outline can start simple. In what order are you going to divide up your main points? You can slowly build a larger outline to include where you will discuss key sources, as well as what are the main claims or ideas you want to present in each section. It’s much easier to move ideas and sources around when you have a larger structure in place.

Example 4.6: A Sample Outline for a Research Paper

- College athletics is a central part of American culture

- Few of its viewers fully understand the extent to which players are mistreated

- Thesis: While William Dowling’s amateur col lege sports model does not seem feasible to implement in the twenty-first century, his proposal reminds us that the real stakeholders in college athletics are not the athletic directors, TV networks, and coaches, but the students themselves, who deserve th e chance to earn a quality education even more than the chance to play ball.

- While many student athletes are strong students, many D-1 sports programs focus more on elite sports recruits than academic achievement

- Quotes from coaches and athletic directors about revenue and building fan bases (ESPN)

- Lowered admissions standards and fake classes (Sperber)

- Scandals in academic dishonesty (Sperber and Dowling)

- Some elite D-1 athletes are left in a worse place than where they began

- Study about athletes who go pro (Knight Commission, Dowling, Cantral)

- Few studies on after-effects (Knight Commission)

- Dowling imagines an amateur sports program without recruitment, athletic scholarships, or TV contracts

- Without the presence of big money contracts and recruitment, athletics programs would have less temptation to cheat in regards to academic dishonesty

- Knight Commission Report

- Is there any incentive for large-scale reform?

- Is paying student athletes a real possibility?

Some writers don’t think in as linear a fashion as others, and starting with an outline might not be the first strategy to employ. Other writers rely on different organizational strategies, like mind mapping, word clouds, or a reverse outline.

More Resources 4.3: Organizing Strategies

At this point, it’s best to get some writing done, even if writing is just taking more notes and then organizing those notes. Here are a few more links to get your thoughts down in some fun and engaging ways:

- Concept Mapping

- The Mad Lib from Hell: Three Alternatives to Traditional Outlining

- Thinking Outside the Formal Outline

- Mind Mapping in Research

- Reverse Outlining

Start Drafting in the Middle

This may sound odd to some people, but it’s much easier to get started by drafting sections from the middle of your paper instead of starting with the introduction. Sections that provide background or more factual information tend to be more straightforward to write. Sections like these can even be written as you are still finalizing your argument and organizational structure.

If you’ve completed the three previous writing projects, you will likely also funnel some of your work from those projects into the final essay. Don’t just cut and paste entire chunks of those other assignments. That’s called self-plagiarism, and since those assignments serve different purposes in different genres, they won’t fit naturally into your research essay. You’ll want to think about how you are using the sources and ideas from those assignments to serve the needs of your argument. For example, you may have found an interesting source for your literature review paper, but that source may not help advance your final paper.

Draft your Introduction and Conclusion towards the End

Your introduction and conclusion are the bookends of your research essay. They prepare your reader for what’s to come and help your reader process what they have just read. The introduction leads your reader into your paper’s research, and the conclusion helps them look outward towards its implications and significance.