- Create new account

- Reset your password

Register and get FREE resources and activities

Ready to unlock all our resources?

An overview of the Welsh education system

The education system in Wales used to resemble the structure set up in England , with maintained schools (most state schools) following the National Curriculum. However, from September 2022 a new curriculum will be introduced that has been created in Wales by teachers, partners, practitioners and businesses. The age of a child on 1 September determines when they need to start primary school.

From September 2022 , phases and key stages will be replaced with one continuum of learning from ages 3 to 16 in each of the new areas of learning. The areas are:

1. Expressive arts

2. Humanities

3. Health and wellbeing

4. Science and technology

5. Mathematics and numeracy

6. Languages, literacy and communication

In addition, literacy, numeracy and digital skills will be embedded throughout all curriculum areas.

Boost your child's maths & English skills!

- We'll create a tailored plan for your child...

- ...and add activities to it each week...

- ...so you can watch your child grow in skills & confidence

What about teaching in Welsh?

The Welsh Government wants to make sure that children can be educated in Welsh if there’s a need or demand for it, so Welsh is taught as a part of the curriculum in all schools up to the age of 16 . Schools have the option to teach lessons entirely or mostly in Welsh – this includes English-medium schools (schools where children are taught in English).

‘Welsh-medium’ schools are schools where children are taught in Welsh. Children going to these schools also get a good grounding in English language skills, but schools are not required by law to teach English in Years 1 and 2.

Does the curriculum in Wales have a Welsh slant?

Take the subject of history, for example. Welsh schools are given discretion on exactly what to teach in history within the curriculum. Although they’re encouraged to focus on historical figures and events from their local area and around Wales in the first instance, they’re also free to include topics involving Britain as a while.

What tests do pupils in Wales take?

Statutory teacher assessments are usually administered at the end of Key Stage 2 and Key Stage 3, as in England, but students do not take Key Stage 2 National Curriculum Tests (Standard Attainment Tests, or SATs) .

However, Key Stage 2 assessments will not continue from September 2022 and Key Stage 3 assessments are to end when the new curriculum rollout has been completed (by 2024).

Since May 2013, all children in Wales from Y2 to Y9 have taken National Reading and Numeracy Tests as part to a new National Literacy and Numeracy Framework (LNF). These will continue with the new curriculum in 2022.

Students take General Certificate of Secondary Education exams (GCSEs) during year 11, and have the choice to continue on to Years 12 and 13 to sit A-level exams.

Please note: the table below is best viewed on a desktop (not mobile) screen.

When is the new curriculum for Wales being introduced?

The new curriculum for Wales will be introduced in school classrooms from nursery to Year 7 in 2022, rolling into Year 8 in 2023, Year 9 in 2024, Year 10 in 2025 and Year 11 in 2026. All schools will have access the final curriculum from 2020, to allow them to move towards full roll-out in 2022.

Give your child a headstart

- FREE articles & expert information

- FREE resources & activities

- FREE homework help

More like this

GOV.WALES uses cookies which are essential for the site to work. Non-essential cookies are also used to tailor and improve services. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies.

Education: our national mission

Our strategy to improve education along with updates, achievements and milestones.

- Education and skills planning and strategy (Sub-topic)

In this collection

Our national mission.

Includes updates on progress and new objectives.

- Our national mission 21 March 2023 Policy and strategy

Education in Wales: action plan 2017 to 2021

Actions planned to improve the school system, including its sixth forms, up until 2021. The approach and some of the actions remain relevant.

Keynote speeches

- Bevan Foundation: high standards and aspirations for all

- A vision for higher education

- A vision for further education

- A Second Chance Nation: Where it's never too late to learn

- Curriculum for Wales: towards September 2022: what you need to know and do

- Cymraeg belongs to us all

First published

Last updated, share this page.

- Share this page via Twitter

- Share this page via Facebook

- Share this page via Email

Education Wales

Online safety and sextortion – help and training for teachers.

Darllenwch y dudalen hon yn Gymraeg

Incidents of online abuse are ever evolving with ‘sextortion’ the latest issue to make the headlines.

The Keeping Safe Online area of Hwb has all the latest support and practical help for teachers on emerging, high priority issues and information on the current trends in online behaviour of children and young people.

Sextortion is financially motivated sexual extortion. It is on the rise globally with reports of children and young people being forced into paying money or meeting another financial demand (such as purchasing a pre-paid gift card) after an offender has threatened to release nudes or semi-nudes of them.

The latest support for schools from the National Crime Agency (NCA) is now available bilingually on Hwb.

It includes a template letter for parents and carers to make them aware of the recent rise in reporting of sextortion.

Sharing nudes and semi-nudes guidance has been created for teachers to help respond to incidents and gives a legal context.

Hwb has also produced a 10 minute video about sharing nude images which is designed to help schools:

- Plan their approach to preventing and responding to incidents

- Understand current image sharing safety concerns, including sextortion and AI-generated media

- Access confidential advice and the reporting services available

Social media training

Two thirds of children aged 3-17 use social media apps. Last year, children in the UK spent an average of 2 hours a day on TikTok

These numbers are growing so understanding how to help young people use social media safely is vital.

A new video is available to help schools.

It covers how a school can safely manage its own social media presence, with further guidance available here .

It provides information on how schools can understand and spot emerging social media related issues and harmful behaviours, such as powerful online influencers and misinformation.

It navigates schools through the Keeping Safe Online area of Hwb to find the right sources of support and the best ways to talk to children and young people about these issues.

Help for parents and carers

Resources are available for schools to share with parents and carers:

- Leafle t: Supporting your child when they are online

- Social media and gaming app guides : an overview of the most popular apps, such as TikTok, Snapchat and Call of Duty.

- Video to direct parents and carers to the Keeping Safe Online area of Hwb

Equity and inclusion in the Curriculum for Wales

With the introduction of the Curriculum for Wales, schools and other educational settings across Wales are designing, using and refining their curriculum to ensure all children and young people are supported to reach their full potential.

Following National Network events held across Wales, case studies are now available on Hwb with schools showing how their curriculum is supporting equity, helping children progress in their learning and fulfil their potential. The events gave practitioners an opportunity to share their experiences and gain valuable insights into approaches others are taking to ensure their curriculum supports equity and inclusion for all.

The case studies include information about approaches to additional learning provision, becoming a trauma informed school, overcoming economic disadvantage and more. A directory of organisations from the events that can support schools and settings with equity and inclusion is also available on Hwb.

The case studies

- Crownbridge Special School, Torfaen – person-centred planning for pupils with a range of complex and multiple additional learning needs.

- Fitzalan High School, Cardiff – ensuring inclusivity in a school where approximately 75% of learners have English as an additional language.

- Lewis School Pengam, Caerphilly – promoting citizenship, equity and inclusion within the curriculum.

- Malpas Court Primary School, Newport – a school with a speech and language base and where 44% of learners have additional learning needs

- Monkton Primary School, Pembroke – creating a curriculum focussing on community a sense of ‘cynefin’.

- Moorland Primary School, Splott, Cardiff – Inquiry-based learning

- Victoria Gems, Jewels and Treasures Nursery, at Victoria County Primary school, Wrexham – developing a nursery setting curriculum that promotes equity and inclusion

- Ysgol Bro Pedr, Lampeter, Ceredigion , (one of the first 3 to 19 schools in Wales) – developing an inclusive curriculum at an all-through school.

- Ysgol Gynradd, Llandeilo, Carmarthenshire – overcoming economic disadvantage.

- Ysgol Maes Derw PRU, Swansea – Curriculum for Wales at a PRU

- Ysgol Plas Cefndy PRU Denbighshire – developing a curriculum that promotes equity and inclusion.

- Ysgol Santes Dwynwen, Newborough, Anglesey (Welsh-medium primary school) – a trauma informed school

- St Christopher’s school, Wrexham – supporting all learners to develop their skills in environments outside of the classroom.

- Welsh Immersion, Cardiff – provision to facilitate pupils wishing to transfer to Welsh medium education.

For more networking and information around equity and inclusion and the Curriculum for Wales, log in to Hwb and join the network (search Hwb networks for ‘Equity and Inclusion Tegwch a Chynwysoldeb’).

By registering on the National Network platform you can get the latest information about in-person and online conversations as well as access to materials related to National Network conversations.

Sully Primary School – a whole school approach to International Languages. The journey so far…

By integrating cultural experiences into their new curriculum, Sully Primary School are inspiring pupils to find out more about the world around them and discover a love for languages.

With a diverse pupil population, the school has created an environment where language is a dynamic force for celebration, identity, and connection. Parents and cultural institutions are invited into the school to share their personal experiences, knowledge and language skills.

Through exposure to Welsh, Spanish, Mandarin, French, and Italian, a multi-language approach has been developed.

A new curriculum

The school developed a clear aim and vision of what they wanted from the new curriculum and how to achieve it.

Their vision was for pupils to receive an engaging language education, one that developed their curiosity of the world around them, not just being the passive recipients of language teaching.

Their curriculum has been designed to ensure International Languages are firmly positioned to connect with the other areas of learning and experience, with the four purposes as its cornerstones.

Putting theory into practice

They wanted recognition of their curriculum journey and aimed to become an International School with accreditation from the British Council. This itself gave a framework to plan within.

At the beginning of their journey, they were lucky to have a member of staff who was passionate about international studies and languages. With the backing of the senior leadership team, this person acted as a driver for change. Initially some staff were a little reluctant to give a full buy-in to this planned approach but time, strong guidance and obvious pupil interest gradually resulted in all staff being fully on board.

In the beginning, action plans were shared with stakeholders to gain and buy-in and support from all members of staff and also with the shared understanding of families and the governing body.

They quickly developed strong links with the Italian Embassy, The Confucius Institute and The British Council who have all been immensely supportive in helping Sully Primary School become an International School.

At the heart of their curriculum lies the translanguaging approach. Pupils are encouraged to explore linguistic connections and patterns through exposure to Welsh, Spanish, Mandarin, French, and Italian at different stages throughout their education. These languages were chosen after discussions with their secondary school MFL teachers, who advised to stay away from delivering on one language and instead encouraged us to develop a multi-language approach to foster a love of and a curiosity for languages.

Professional learning

It was very important to ensure staff were fully on board and confident enough with their own language skills and cultural knowledge. Funding from the British Council enabled staff to travel to countries including Spain, Italy and China.

Cultural visits across the globe assisted in creating a greater independent approach towards professional development with staff seeking to increase their own language skills.

A few members of staff requested refresher training in Welsh language. Another enrolled on a night school course with her husband to learn Italian and a few others started competing with each other using Duolingo.

Skills of the existing workforce were developed along with relationships with outside agencies who could bring expertise into the school, benefitting both children and staff. There are now members of staff who are comfortable in delivering basic Spanish, French and Italian sessions and peripatetic Italian and Chinese language teachers are used to deliver weekly language lessons across the school.

Language as a tool for connection and knowledge

Recognising the relationship between language and culture, cultural experiences are actively integrated into language education. ‘International Languages Week,’ enables pupils to immerse themselves in the exploration of a specific country, delving into its culture, language, and religion.

These weeks provide a platform for inviting parents into the school to share their personal backgrounds, cultural knowledge, and language skills. Embraced by the wider school community, these weeks culminate in a celebratory display, allowing children to showcase their newly acquired skills and knowledge to a wide audience.

Last year the school was selected to work with the British Council for the Cerdd Iaith project with pupils learning songs in a range of different languages. They worked with the writer and composer, Tim Riley, and the Welsh actor and singer Lily Beau. The positive impact of this project on pupils was clear. The weekly sessions left pupils feeling energised and excited, learning new words and phrases in different languages.

Involvement in the project culminated in a concert at the Wales Millennium Centre where pupils got to perform with a live orchestra alongside children from all over Wales.

Use of the Cerdd Iaith website continues with a weekly singing assembly for older children. The resources provided by Cerdd Iaith fit perfectly with the schools translanguaging-centric approach to the teaching of International Languages.

Welsh Government consultation on draft trans guidance for schools – update

Education leaders and practitioners have been clear that they need national guidance to support trans and nonbinary children and young people to feel valued, included, and safe in their education.

We know teachers and schools are already working hard to support children and young people. Providing appropriate national guidance for schools in Wales to support trans, nonbinary and gender questioning children and young people in education is a Welsh Government commitment.

We have been working closely with school leaders, practitioners, learners and a wide range of stakeholders on the development of guidance for Wales.

A public consultation was planned for this academic year. However, we have decided to take more time to develop the guidance so that it’s informed by the best available evidence, including the findings of the Cass Review and the views of stakeholders, including learners themselves and parents.

We are committed to taking this guidance forward. All learners need to feel valued, included and safe and ensuring their wellbeing is our main priority.

Thanks to everyone, especially to the children and young people who have talked to us so far and helped develop this guidance.

Designing a curriculum – updated guidance for schools

Following a period of co-construction and consultation with practitioners, the Curriculum for Wales guidance has been updated to include ‘ Continuing the Journey ’, which outlines our expectations for ongoing curriculum design.

Whilst our expectations for curriculum design have not changed, we have, in response to practitioners, made the guidance shorter and easier to navigate and understand.

It has been split into 4 areas:

- Purpose : what should our learners learn and why?

- Progression : what should progress in that learning look like for each learner?

- Assessment : how are we assessing to enable that progression?

- Pedagogy : how does our daily practice support our curriculum?

Easy to access support is also now available on Hwb, including:

- Navigating the Curriculum for Wales Framework – a hyperlinked document to help navigate the guidance.

- Key terms from the Curriculum for Wales – explaining more about terms such as ‘cross cutting themes’, ‘the four purposes’ and ‘principles of progression’.

- Understanding Cluster Working – a model for cluster working to support planning, designing, reviewing, and refining curriculum and assessment.

- What are schools legally required to do? An understanding of the mandatory and statutory duties for headteachers and governing bodies.

- Assessing learner progress – practical support for assessment design

- Developing a shared understanding of progression .

- Shared understanding of progression: supporting cluster working

- Principles of progression: supporting self-evaluation and a shared understanding of progression .

- A range of Professional learning resources to support effective curriculum design.

Work is underway, with input from schools, to provide updated guidance on each of the areas of learning and experience.

Keep an eye out for more information over the next couple of months.

Wales’ Professional Learning Resources – now in one place!

See this post in Welsh

For the first time, Professional Learning resources have been centralised in one place on Hwb. The freshly categorised and classified resources are now readily searchable and accessible to all education practitioners across Wales via the professional learning area .

The professional learning area has been organised to help practitioners find the right resources to meet their professional learning needs, whatever those needs may be. Within the area, practitioners will find a wide breadth of training, self-guided learning, case studies, guidance, and research on all aspects of professional learning. The resources cover 4 broad areas: curriculum, pedagogy and assessment; leadership and governance; well-being, equity and inclusion; and developing as a professional. Practitioners can filter the resources within these categories or search for resources using keywords.

A practitioner working party was convened to assure quality during the process, and several other groups are still providing feedback. The PL area is a work in progress and feedback can be left by anyone accessing the page. Your feedback will help us improve it.

Practitioner Sally Llewellyn has been seconded to lead the work. She says:

‘This is all about identifying and gathering together appropriate, relevant, high quality professional learning provision to support practitioners with their continued development and Curriculum for Wales implementation. We’ve listened to colleagues asking for a more searchable repository of quality resources, and now it’s here and it’s continuing to develop.

‘I’ve worked with middle tier organisations including regional consortia, local authorities, the National Academy for Educational Leadership, Higher Education Institutions, The Arts Council for Wales, Diversity and Anti-Racist Professional Learning, as well as Welsh Government priority policy areas including curriculum and assessment, equity in education, and workforce and wellbeing.’

School Governors: a new resource for evaluation and improvement

‘Governor’s Self Evaluation’ is a new resource designed to help governing bodies evaluate their work and act as a critical friend when looking at the effectiveness of their school.

It contains practical guidance, prompts, interactive resources, training materials and case studies.

Currently in its pilot phase, any feedback on the resource is welcome before the final version is published on Hwb in September. A link to a feedback form can be found on the landing page.

The resource is a guide and its use is optional. There is no expectation for governors to evaluate every prompt or address every aspect within this resource systematically. Governors are welcome to use as much or as little as required.

The resource draws on content from other self-evaluation toolkits available regionally, and is presented in a similar way to the National Resource: Evaluation and Improvement (NR:EI) used by schools.

A new Cabinet Secretary for Education – letter from Lynne Neagle

As part of the Cabinet reshuffle , following the appointment of Vaughan Gething as First Minister, Lynne Neagle has been appointed as the Cabinet Secretary for Education, replacing Jeremy Miles who moves to the Economy portfolio.

Lynne Neagle is the Senedd Member for Torfaen, and moves to Education from her previous Cabinet post as the Deputy Minister for Mental Health.

Dear Colleague

I am privileged to have been appointed Cabinet Secretary for Education. I know from my time as Chair of the Senedd Children, Young People and Education Committee what a dedicated and hard-working education workforce we have in Wales, and I am really looking forward to working with you in my new role.

You are critical to the success of our transformative education reforms, including the Curriculum for Wales roll out, the current consultation on 14 to 16 learning, Made-for-Wales GCSEs, and the implementation of the Additional Learning Needs programme. Ensuring you have the tools to make these reforms a success will be my number one priority.

I am acutely aware that you are supporting our ambitious transformation of education while also dealing with the aftermath of a global pandemic. The increase in mental health issues amongst learners and the workforce, a drop in attendance and reports of deteriorating behaviour are matters that worry us all.

Government, parents and carers, and society as a whole need to come together to address these challenges. I know it can’t all be the responsibility of schools.

Making sure our young people have the best chance in life is a passion for me. A good education in an inclusive, safe, and nurturing environment helps build skills, knowledge and resilience. It is the greatest gift we can give our children and young people.

As Deputy Minister for Mental Health, I jointly chaired our Ministerial Board to take forward our Whole Schools Approach to Mental Health and Wellbeing in Wales and was able to secure additional funding for Child and Adolescent Mental Health services in Wales.

I intend to spend my first months in office listening to you. I hope to visit schools after Easter and during those visits, as well as meeting children, young people, and your staff, I would like to talk to you about your burning issues.

I am really looking forward to working with you and meeting as many of you as possible. If there are issues you would like to discuss with me my door is open. Please email [email protected] or [email protected] and I’ll be in touch.

Yours sincerely

Lynne Neagle AS/MS Ysgrifennydd y Cabinet dros Addysg Cabinet Secretary for Education

How is Estyn changing its approach to Inspection under Curriculum for Wales? – Insights from a Peer Inspector.

Introducing Curriculum for Wales is a journey, not just for schools but for the wider education system as it adapts to support curriculum reform. Estyn’s evolving approach to inspection is an important example.

Ceri Richmond, Deputy Headteacher at Morriston Comprehensive School, is a Peer Inspector. She has recently had a week’s refresher training and is the perfect person to tell us more about how the approach to inspection is changing.

Firstly Ceri, why did you become a Peer Inspector?

I started in 2017 because as a senior leader with responsibility for self-evaluation and teaching and learning, I wanted to ensure that I could identify good practice. I wanted to be confident when observing lessons and mentoring departments in self-evaluation procedures. For me it’s about better teaching and learning, although I started by focussing on school self-evaluation.

What’s the essence of the role?

It’s important for Estyn to have practicing professionals in the team for balance and to bring that current perspective. There are usually at least two peer inspectors in each team. I appreciate the fact that we are full members of the inspection team with the same range of responsibilities. On the other side, I have also appreciated that current perspective from the peer inspectors when my own school is under inspection.

Can you describe your recent training?

I really enjoyed it. We were a room of Peer Inspectors, mainly looking at teaching and learning, pastoral (e.g. skills and attendance) and team development. We looked at lots of examples of pupil work and were asked what we could glean. Evidence gathering is always about triangulating and analysing how those work scrutinies would tie in with observations and pupil voice, for example. During an inspection we would share all our observations and notes from different inspection activities in a live document. This means that all inspectors can collate and see the information pertinent to the area they have been allocated to report on. It’s really good as refresher training if you’ve had a gap in inspections, and I can take a lot back to my own school.

As we move firmly into schools delivering the new Curriculum for Wales, I will be very interested to see how these activities and the focus of these activities will develop to take into account differences, for example in the way we use the principles of progression to measure progress and what we are now measuring in terms of progress, as we move to a purposes-driven curriculum, with a new but more equal emphasis on learner effectiveness as well as knowledge and skills.

How different are inspections under Curriculum for Wales?

The biggest improvement in the current framework is the removal of summative judgements. It means we look at both strengths and weaknesses. You can see the needs of a school, and they do come out in that final report, but the feedback is more balanced and far more constructive.

Leaner inspection arrangements are more focused on the most important areas that drive improvement. It’s also more based on the school’s own self-evaluation activity. In that way, we’re also assessing the strength of the school’s own ability to identify improvement.

Interestingly, in a recent House of Lords evidence session, it was said that the Inspectorate needs to respect the decisions taken at local level on curriculum, otherwise there is a risk that schools will try to please inspectors rather than serve the needs of the learners, which makes absolute sense in Wales!

So what style can schools expect from you?

The style has changed. It’s not big brother anymore, it’s working with the schools and it’s more supportive, although I do believe it will be some time before it feels this way by the school being inspected. The report is far more balanced and constructive. Also, there is more regular contact and more frequent visits – engagement visits and thematic visits. These are designed to focus on improvement processes to support stronger evaluations.

On balance it feels better, especially in a time when the curriculum is being introduced year by year in secondaries. We need to acknowledge the amount of change that’s involved and ensure that all tiers and departments within the sector talk to and communicate openly with each other.

Let Maths Take You Further: Supporting learners on their mathematical journey

Read this post in Welsh

Since April 2023, 3500+ learners from more than 80% of state-funded schools and colleges engaged in mathematics workshops, masterclasses and conferences organised by Further Mathematics Support Programme Wales (FMSPW).

Support is still available to all schools in Wales and can be applied for here .

But for the full picture of the support and how it works for learners in Wales at various ages, read on.

Funded by the Welsh Government and managed by Swansea University, the FMSPW collaborates with partners across Wales and the UK, operating across Aberystwyth, Bangor, Cardiff, and Swansea universities. Together, we offer a comprehensive range of mathematics enrichment activities tailored for all ages.

For pupils in years 7 and 8, FMSPW hosts lunchtime and after-school math clubs, fostering a welcoming atmosphere where participants can engage with mathematics through interactive games and hands-on activities.

For learners aged 14-15, our program provides access to a series of mathematics masterclasses by the Royal Institution, available both online and in-person, along with junior and senior math challenges and problem-solving sessions. Our “Careers in Mathematics” talks offer valuable insights into the practical applications of mathematics in the world of work and study, aiding students in making informed decisions regarding their A-level choices.

As students approach GCSE level, we provide support through revision events and online resources. The FMSPW is especially committed to supporting Additional Mathematics Level 2 qualification as it is evident that the qualification is important for schools. Our recent case studies have shown that studying Additional Mathematics can lead to increased enrolment in A-level mathematics classes, boost confidence among female students, and contribute to a more balanced gender representation at A-level. To encourage more schools to offer Additional Mathematics, FMSPW developed a suite of engaging Desmos resources covering the entire syllabus.

At the A-level stage, FMSPW program extends to include revision classes and a wealth of materials to support students pursuing A-level Mathematics and Further Mathematics qualifications.

For schools unable to offer Further Mathematics internally, FMSPW provides online tuition classes complemented by in-person study days held across Wales. This year, we have had 27 schools subscribe to our Further Mathematics tuition courses, supporting nearly 60 students in studying 140 FM modules. 40% of our students come from schools with medium to high percentages of pupils receiving free school meals.

James Johnson from a school in North Wales shared his positive experience studying Further Mathematics with FMSPW:

“ Studying Further Maths has been a fun, challenging and rewarding experience over the last year. The tutors have provided me plenty of support and there were lots of resources available to assist us during the year .”

Further Mathematics remains an important qualification preferred or encouraged by some universities with research evidence of improved transition to STEM degrees among all students but especially girls.

Problem-solving remains a focal point of the FMSPW program at A-level, with challenging courses designed to stretch students’ understanding. As learner feedback shows, participants find the problems both stimulating and enjoyable, often forming new friendships along the way.

A student in Year 12 who is taking part in the Introduction to Problem Solving course this year said:

“ I feel like the topics were very challenging and difficult to get your head around, which was good because it stretches your understanding .”

Recognising the need to further support Wales’ brightest mathematicians, we offer a hybrid support program for students aiming to study at Russell Group universities, which may require additional mathematics tests like MAT or STEP. Our online Bridging Maths to Uni program helps students bridge the gap between school mathematics and university-level study.

FMSPW extends its gratitude to our partners in schools, colleges, education consortia, and universities for their invaluable help and support. Together, we continue to inspire and empower the next generation of mathematicians in Wales and beyond.

- print Print

- error Feedback

Devolution 20 - Education: How far is it 'made in Wales'?

Much has changed in Wales in the twenty years since the first National Assembly for Wales was elected in May 1999. This is the fourth in a series of articles that attempts to describe some of that change. It has been prepared by Senedd Research as part of the Assembly’s activity to mark twenty years of devolution.

Devolution has given policymakers the opportunity to develop a distinctly Welsh approach to education. In the early years of the Assembly, The Learning Country (2001) strategy was described as a “landmark document for those who hoped that the Welsh Assembly would not just nibble at the edges of educational policy-making but would also conjure up a wider vision of an education system to serve the Welsh nation” (Gareth Elwyn Jones & Gordon Wynne Roderick’s A History of Education in Wales (2003) , cited in Philip Dixon’s Testing Times, 2016 .)

Pre-16 education

A ‘made in wales’ approach.

As part of former First Minister Rhodri Morgan’s 2002 declaration of “clear red water” , between Wales and England, the then Welsh Government ended Standard Attainment Tests (SATs) at Key Stages 1, 2 and 3. The publication of school-level pupil performance (often used to generate ‘school league tables’) also ended.

The Foundation Phase , which was introduced between 2004 and 2009, brought a new approach to young children’s learning, based on an experiential and ‘learning through play’ approach. It remains a flagship policy and the principles on which it is based are now shaping the approach to the new age 3-16 curriculum .

At the other end of the school-age spectrum, the Welsh Baccalaureate , introduced between 2003 and 2007, and revised in 2015, has sought to equip young people with a broader skills base to better prepare them for higher education and the workplace. An Assembly Committee has recently undertaken an inquiry into the Welsh Baccalaureate , publishing a report recognising its centrality to young people’s learning and development and recommending how its status can be enhanced.

Another example is the Free Breakfast Scheme in primary schools. Introduced in 2004, it is intended to improve the concentration and in turn the attainment of pupils.

More recently, this ‘made in Wales’ approach to education has led to a Welsh qualifications system , a lengthy and wide-ranging reform of the Special Education Needs system , and the far-reaching work underway to introduce a new Curriculum for Wales . The SEN reforms have undergone considerable scrutiny over many years, with Assembly Committees most recently scrutinising the Additional Learning Needs and Education Tribunal (Wales) Act 2018 and the draft ALN Code .

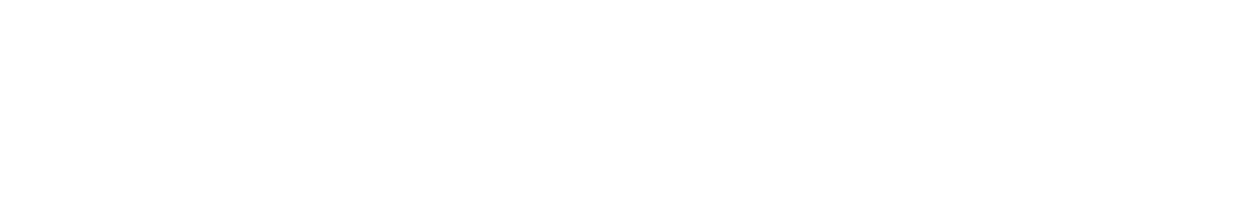

Leaning towards PISA?

Wales’ approach to school improvement has also been influenced by international movements, most notably the OECD and its Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA).

Just over a decade into devolution, the publication of the PISA 2009 results in 2010 delivered what the then Minister for Education, Leighton Andrews, called a “wake up call to a complacent system” and “evidence of a systemic failure”. Wales’ disappointing PISA results precipitated a renewed and changed focus on school accountability, a return to the basics of literacy and numeracy and a new regional approach to school improvement, all set out in the then Minister’s twenty point plan . Following on from this was Huw Lewis’ time as Minister which focused on a drive to tackle the link between deprivation and low attainment. Over time, there has also been a recognition that Wales needs to improve support for more able and talented learners if a greater number are to achieve the highest grades.

The OECD was called in to help identify solutions. Its reports in 2014 and 2017 informed the Welsh Government’s education action plans, Qualified for Life and Education in Wales: Our National Mission 2017-2021 respectively.

Since her appointment as Minister in June 2016, Kirsty Williams has continued to take forward the education reforms already in train such as developing a new curriculum, reforming teachers’ professional development, enhancing educational leadership and tackling the deprivation attainment gap. However, following her agreement in June 2016 with the then First Minister, Carwyn Jones (updated in December 2018 in her agreement with the new First Minister, Mark Drakeford ), Kirsty Williams has also brought her own priorities to the fore.

These include supporting the viability of small and rural schools and reducing infant class sizes. The latter links back to the earliest days of devolution when the existing statutory limit of 30 pupils was introduced in 2001. With Kirsty Williams as Minister, the Welsh Government has reinvigorated this policy and is seeking to reduce the size of classes with 29 or more pupils in underperforming schools and where there are high levels of pupils eligible for free school meals and pupils with Additional Learning Needs.

Returning to PISA, the publication of the 2018 results in December 2019 will shine a further spotlight on the Welsh Government’s progress in raising school standards, particularly given its target of achieving 500 points in each of the three domains by 2021. Since the ‘shock to the system’ delivered by PISA 2009, subsequent results have not significantly improved in Wales as the infographic below shows.

Higher education

Higher education institutions (HEIs) are autonomous organisations, therefore policymakers’ capacity to directly affect a ‘made in Wales’ approach is more limited than with schools. However devolution has seen significant changes in the HE sector and legislation expected in the next year or so could see the Welsh Government substantially reform the strategic planning and funding of the broader post compulsory education and training sector.

One of the more visible examples of the divergence between Wales and England has been student financial support. For example, from 2012 a larger Tuition Fee Grant (TFG) provided students from Wales with a non-means tested grant to cover the cost of increased tuition fees. However, this system diverged further following the Welsh Diamond Review which has seen the TFG being withdrawn for new students from September 2018 as part of a shift toward funding living cost support.

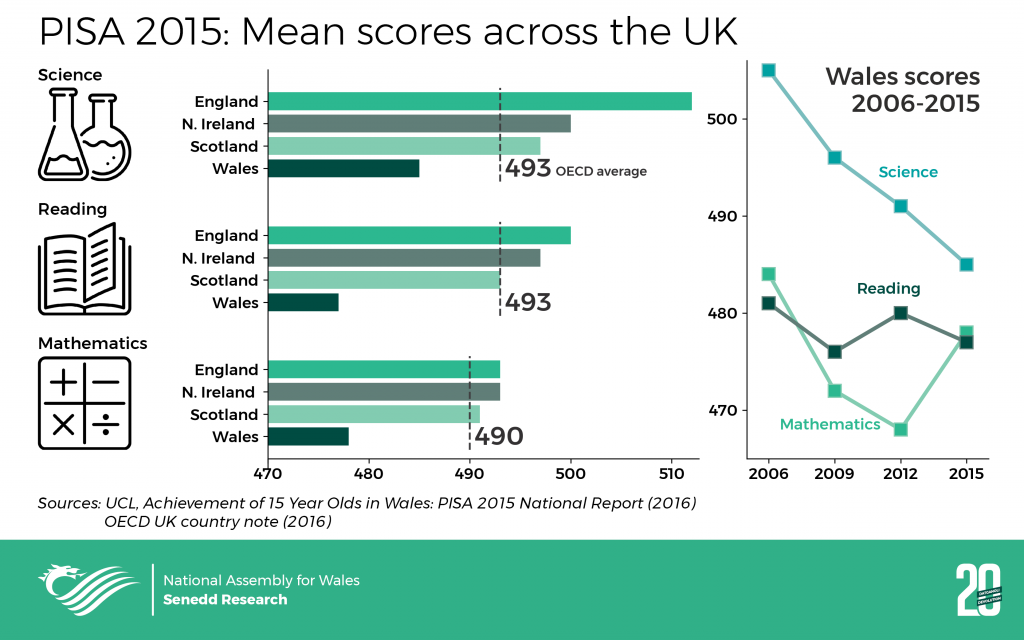

The number and size of HEIs

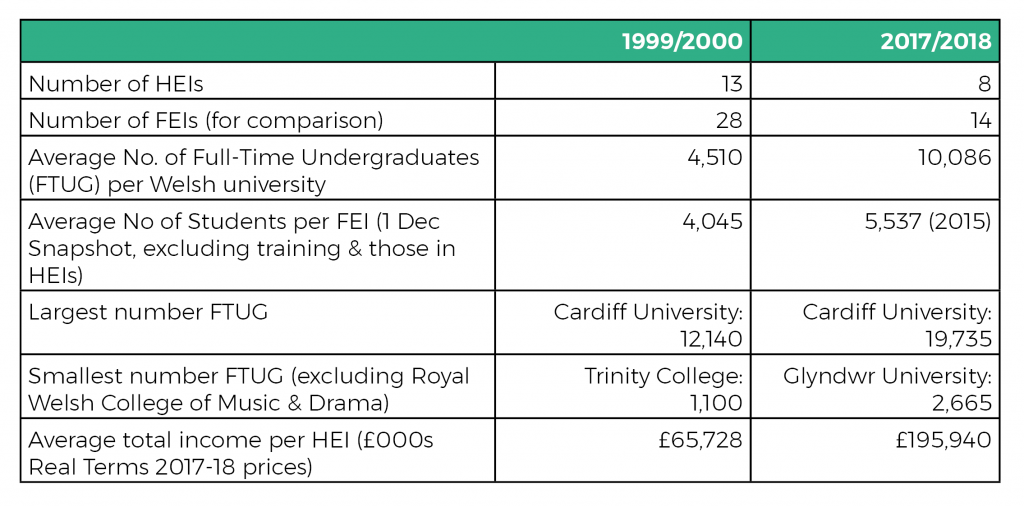

Since 1999, the Welsh Government has sought to actively shape the size and structure of the Welsh HE sector. The extent of this change is illustrated below.

So how did this level of change happen?

In 2002 the Welsh Assembly Government published its Reaching Higher HE strategy in which it explained that: “re-configuration and collaboration must be at the heart of the strategy for HE in Wales”.

After a number of mergers and collaborations under Reaching Higher, and the Welsh Government’s new HE strategy, For our Future (2010), the Higher Education Funding Council for Wales (HEFCW) was tasked with developing a “regional dimension to planning and delivery”. Its 2010 Corporate Strategy said that:

too many of our universities are too small by UK standards, and that we have too many institutions, raising challenges over competitiveness and sustainability.

In 2010, after the then Education Minister Leighton Andrews had warned universities must “ adapt or die ”, HEFCW published its recommendations on the future shape of higher education in Wales . These suggested radical change, consolidating the sector into no more than six HE institutions. These plans led to the merger of the University of Wales, Newport and the University of Glamorgan into the University of South Wales.

This proposal to create what was to become USW originally included the University of Wales Institute, Cardiff (UWIC) , now Cardiff Metropolitan University. However its governing body resisted the Welsh Government’s attempt to dissolve the institution in what became a demonstration of the autonomy of universities.

In contrast to the deliberate national policy of planned change, some institutions have instigated change themselves.

Some exercised their independence by withdrawing from the University of Wales federal umbrella and applying for their own Degree Awarding Powers and the right to use “university” in their title.

Some initiated their own mergers. For example, the University of Wales, Lampeter, the University of Wales itself, Swansea Metropolitan University and Trinity College, Carmarthen merged together in stages to form the current University of Wales Trinity St David.

The table below demonstrates the effect of the sector’s consolidation into fewer, larger institutions and offers a broad comparison (where data is available) with the further education (FEIs) sector. As the number of institutions has dropped since devolution and all have gained university title, enrolments and incomes have broadly increased.

The number of people participating in higher education

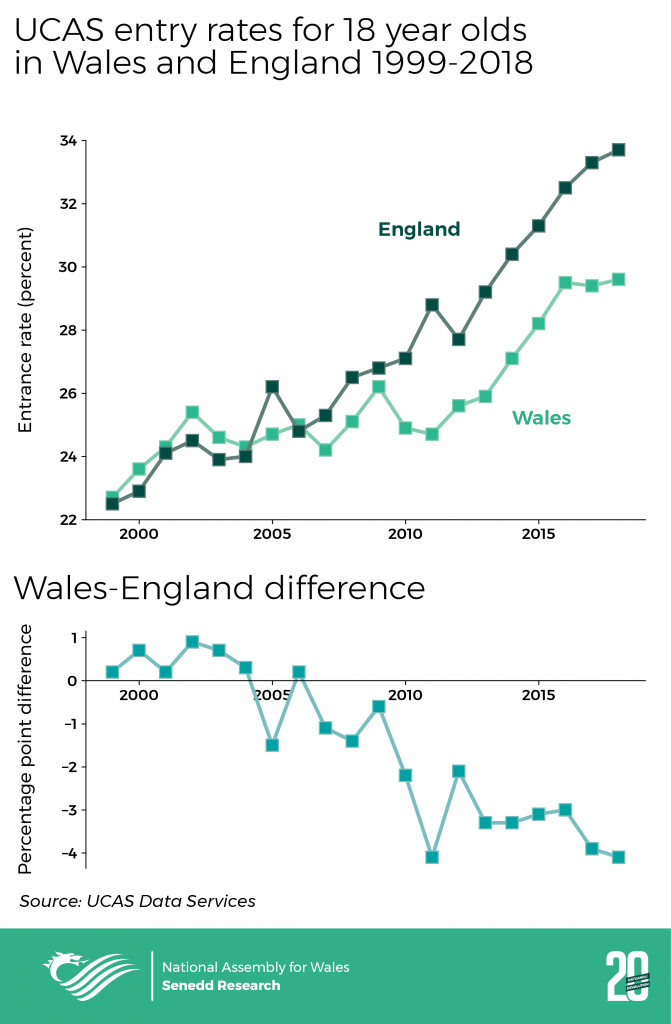

Over the past twenty years, there has been a consistent trend for a higher proportion of 18 year olds in the UK to attend higher education each year.

The graphic below shows this trend since 2000 for both Wales and England. This higher participation rate has helped to broadly maintain recruitment numbers during the last few years when the 18 year old population in the UK has been temporarily falling.

Changes in how HEIs receive their income

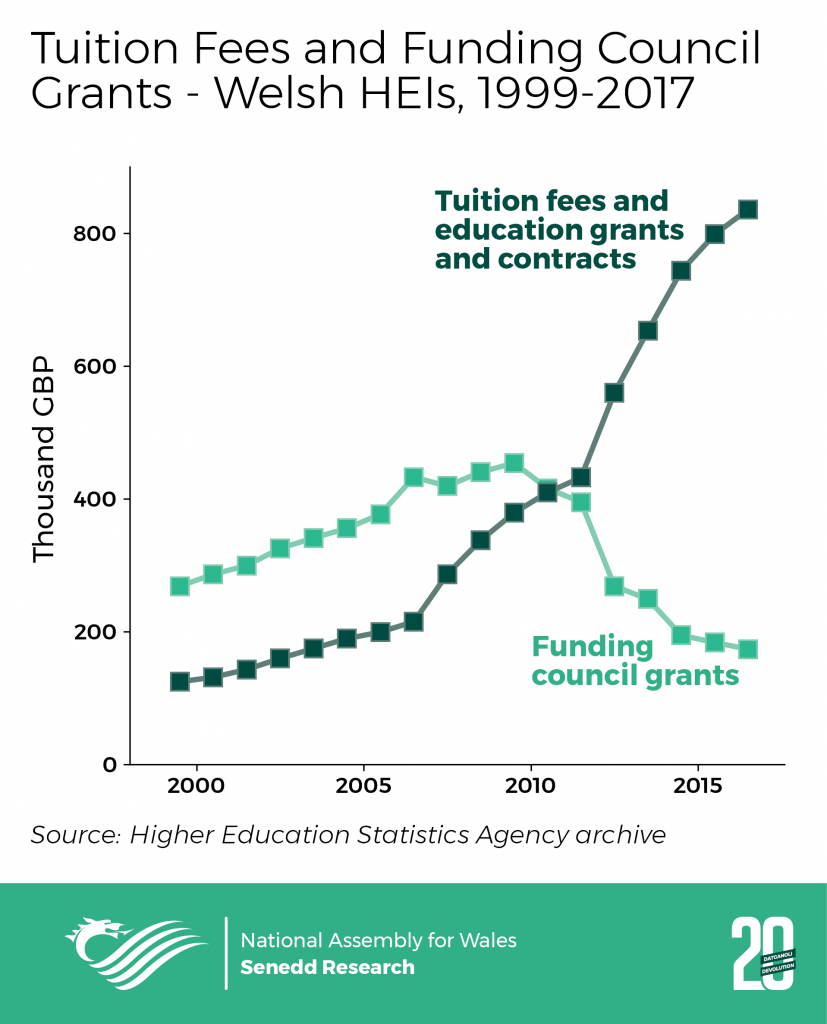

Throughout the last twenty years, institutions have received more of their income from student fees and less from central HEFCW grants.

The removal of student number controls in both England and Wales from 2015/16, has allowed HEIs to increase student numbers, thereby generating increased income through the greater volume of tuition fees.

The graphic below shows the shift from central grant funding toward student tuition fee funding, a shift that accelerated from 2012/13 with the introduction of £9,000 fees.

The future is likely to bring further reform with the Welsh Government proposing, through legislation in the Assembly, to bring further education, higher education, work-based learning and adult community learning together under a single arms-length strategic planning and funding Commission.

This would result in the dissolution of HEFCW and the Welsh Government relinquishing funding and regulation of further education to the proposed Commission for Tertiary Education, Training and Research. The aim of such reform is to bring about a post-16 education sector that is characterised by clear and seamless progression routes for learners across all types of institution.

The next article to be published tomorrow will look at the environment .

Article by Michael Dauncey and Phil Boshier , Senedd Research, National Assembly for Wales

Helpful links

- Subscribe to knowledge exchange updates chevron_right

- Get involved with the Senedd’s work chevron_right

- Subscribe to updates chevron_right

The Welsh Government’s “national mission” for education: In Brief

Higher and Further Education in Wales

- About Wales

© Hawlfraint y Goron / Crown Copyright

A passion for education

Wales is a nation where learning is valued and academic standards are high. As part of the UK higher-education and further-education systems, our universities and colleges offer qualifications that are respected by academics and employers across the world.

Our universities are modern and innovative, but our history goes back a long way. Higher education in Wales began in 1822, when St David’s College, Lampeter, opened its doors. We now have eight universities, with campuses located throughout the country.

Around 149,000 students are enrolled at Welsh universities, including around 25,000 international students, drawn from 132 countries. They’re attracted by a culture of excellence in both teaching and research. In the UK’s last Research Excellence Framework, more than three quarters of the work taking place at our universities was judged to be ‘world leading’ or ‘internationally significant’.

Three of our eight universities feature in the top 500 of the Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2022. And student satisfaction is vital. In the last Whatuni Student Choice Awards, four of the places in the UK top 10 – including the number-one spot – were taken by Welsh universities.

Further education colleges in Wales focus on education and training opportunities for people of all backgrounds who are aged 16+. Further education colleges are at the heart of their communities with excellent links to industry and clear progression routes to universities in the UK.

They have an excellent reputation for integrating international students into the culture, language and life of Wales.

We may have plenty of castles in Wales, but we don’t have ivory towers. Our universities have tight links with their local communities and the worlds of business and technology. Within six months of leaving, 92% of graduates are in employment.

Global Wales

In recognition of the importance of Welsh universities’ and colleges' international activities, Global Wales was set up. It’s a partnership between Universities Wales and the Welsh Government , British Council Wales , Colleges Wales and the Higher Education Funding Council for Wales (HEFCW), and is currently funded by Taith .

The Global Wales programme provides a strategic, collaborative approach to international higher and further education education in Wales. It also aims to raise awareness about Wales, build on international partnerships with universities and colleges, and to promote them in key overseas markets. See the Universities Wales website for more information.

Related stories

Nearly 130,000 students are enrolled on courses at our universities. Here are 10 reasons why you should join them.

This is what you'll love about Wales

As a student, you’ll enjoy a great quality of life, whether your taste is for art and culture, socialising or exploring our great outdoors.

This is what to expect

Wales is famous for its warm welcome – and when you’re starting at university, it begins long before you arrive on campus.

Student life

How our universities will help you make the most of all the opportunities and experiences on offer outside the library and lecture theatre.

Before you start...

This site uses animations - they can be turned off.

Terms and Conditions

By using this site, you confirm you agree to our Terms and Conditions .

Sign up to our newsletter

Receive all the latest information about studying in Wales, scholarships opportunities, and student advice straight to your inbox!

- Education spending

Major challenges for education in Wales

- Luke Sibieta

Published on 21 March 2024

This report examines the major challenges for education in Wales, including low outcomes across a range of measures and high levels of inequality.

- Education and skills

- Poverty, inequality and social mobility

- Human capital

Download the report

PDF | 583.29 KB

The author gratefully acknowledges the support of the Economic and Social Research Council via the ESRC Centre for the Microeconomic Analysis of Public Policy. This report also draws heavily on analysis and knowledge gained by the author in his work as a Research Fellow at the Education Policy Institute.

Executive summary

Last December, the OECD published the latest round of PISA tests in reading, maths and science skills. These international comparisons always prompt public debate. Most countries saw declining scores, reflecting the effects of the pandemic. In Wales, the declines were particularly large, erasing all the progress seen since 2012. This report argues that low scores in Wales are a major concern and challenge for the new First Minister. Low educational outcomes are not likely to be a reflection of higher poverty in Wales, a different ethnic mix of pupils, statistical biases or differences in resources. They are more likely to reflect differences in policy and approach. We recommend that policymakers and educators in Wales pause, and in some cases rethink, past and ongoing reforms in the following areas:

- The new Curriculum for Wales should place greater emphasis on specific knowledge.

- Reforms to GCSEs should be delayed to give proper time to consider their effects on long-term outcomes, teacher workload and inequalities.

- More data on pupil skill levels and the degree of inequality in attainment are needed and should be published regularly.

- A move towards school report cards, alongside existing school inspections, could be an effective way to provide greater information for parents without a return to league tables.

Related content

Sliding education results and high inequalities should prompt big rethink in welsh education policy, key findings.

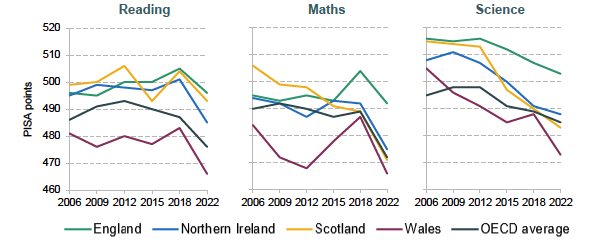

- PISA scores declined by more in Wales than in most other countries in 2022, with scores declining by about 20 points (equivalent to about 20% of a standard deviation, which is a big decline). This brought scores in Wales to their lowest ever level, significantly below the average across OECD countries and significantly below those seen across the rest of the UK. Scotland and Northern Ireland also saw declines in PISA scores in 2022, whilst scores were relatively stable in England.

- Lower scores in Wales cannot be explained by higher levels of poverty. In PISA, disadvantaged children in England score about 30 points higher, on average, than disadvantaged children in Wales. This is a large gap and equivalent to about 30% of a standard deviation. Even more remarkably, the performance of disadvantaged children in England is either above or similar to the average for all children in Wales.

- These differences extend to GCSE results. In England, the gap in GCSE results between disadvantaged and other pupils was equivalent to 18 months of educational progress, which is already substantial, in 2019 before the pandemic. In Wales, it was even larger at 22–23 months in 2019 and has hardly changed since 2009. The picture is worse at a local level. Across England and Wales, the local areas with the lowest performance for disadvantaged pupils are practically all in Wales. There are many areas of England with higher or similar levels of poverty to local areas in Wales, but which achieve significantly higher GCSE results for disadvantaged pupils, e.g. Liverpool, Gateshead and Barnsley.

- A larger share of pupils in England are from minority ethnic or immigrant backgrounds than in Wales. Such pupils tend to show higher levels of performance. However, even this cannot explain lower scores in Wales, as second-generation immigrants also tend to show lower levels of performance in Wales than in England.

- The differences in educational performance between England and Wales are unlikely to be explained by differences in resources and spending. Spending per pupil is similar in the two countries, in terms of current levels, recent cuts and recent trends over time.

- There are worse post-16 educational outcomes in Wales, with a higher share of young people not in education, employment or training than in the rest of the UK (11% compared with 5–9%), lower levels of participation in higher education (particularly amongst boys) and lower levels of employment and earnings for those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

- The explanation for lower educational performance is much more likely to reflect longstanding differences in policy and approach, such as lower levels of external accountability and less use of data.

- There are important lessons for policymakers in Wales from across the UK. The new Curriculum for Wales is partly based on the Scottish Curriculum for Excellence, with both having noble aims to broaden the curriculum, improve well-being and focus on skills. However, there is now evidence arguing that these quite general skills-based curricula might not be effective ways to develop those skills. New GCSEs are due to be taught in Wales from 2025, including greater use of assessment, a broader range of subjects and the removal of triple science as an option. These reforms run the risk of widening inequalities, increasing teacher workload and limiting future education opportunities. There is much greater use of data to understand differences in outcomes and inequalities in England. This could easily be emulated in Wales without a return to school league tables.

1. Introduction

In December 2023, the OECD published the latest round of PISA scores (OECD, 2023). These international comparisons of reading, maths and science skills always prompt significant public debate, particularly in countries seeing declining scores. The latest tests were taken in 2022. Most countries saw declining scores, reflecting the effects of school closures during the pandemic.

In Wales, scores declined significantly, with the lowest test scores across the four nations of the UK. This erased all the increases seen in Wales since 2012 , when low PISA test scores last prompted soul-searching in the Welsh education system. This time, concern about low scores within Wales has been relatively brief, with the Minister emphasising ongoing reforms (Miles, 2023). This contrasts with the picture elsewhere in the UK. In Scotland , low and declining scores have prompted significant public debate and have led the Minister to promise improvements to the system (Gilruth, 2023). In England , ministers have claimed credit for relatively high scores and an improvement in relative scores compared with other countries. There were also declines in Northern Ireland, though public debate has been mostly focused on the restoration of the Northern Ireland Executive.

This short report argues that low education outcomes, high levels of inequality and their consequences for children’s life chances represent a major challenge for the new First Minister of Wales. Improving this situation should be an urgent priority for his new government.

2. Overall performance and inequalities in Wales

This section sets out the overall performance of pupils in Wales in PISA tests over time, overall levels of inequality and how this compares with the rest of the UK.

Large declines in reading, maths and science skills in Wales

Starting with the overall picture, Figure 1 shows that PISA test scores in Wales fell significantly in maths, reading and science in 2022. To some extent, this matches the decline seen across other OECD countries following the global pandemic. However, there was a steeper fall in Wales in reading and science. Scores in Wales are also now lower than in any previous PISA cycle. The declines in Wales represented about 20 PISA points, on average. This is equivalent to about 20% of a standard deviation, which is a substantial decline.

Figure 1. PISA scores across UK nations over time

Source: Based on figures 7.13–7.15 in Sizmur et al. (2019); OECD (2023).

We also saw large falls over time in maths and science in Scotland and Northern Ireland. Across both nations, there were smaller falls in reading scores, which remain above the OECD average.

In England, we see a different picture. Reading and maths skills were increasing gradually between 2006 and 2018. There was then a relatively small decline in both reading and maths scores in 2022, taking them back to the same levels as around 2012/2015. Given the scale of disruption to education during the pandemic and the declines seen across other OECD countries, a small decline and general stable pattern over the last 10 years is likely to be a positive sign of resilience in England.

Whilst there were declines in science scores in England in 2022, Jerrim (2024) argues that this decline is seen across most OECD countries and may reflect methodological changes in the survey over time. Science scores in England also remain well above the OECD average.

Larger inequalities in Wales

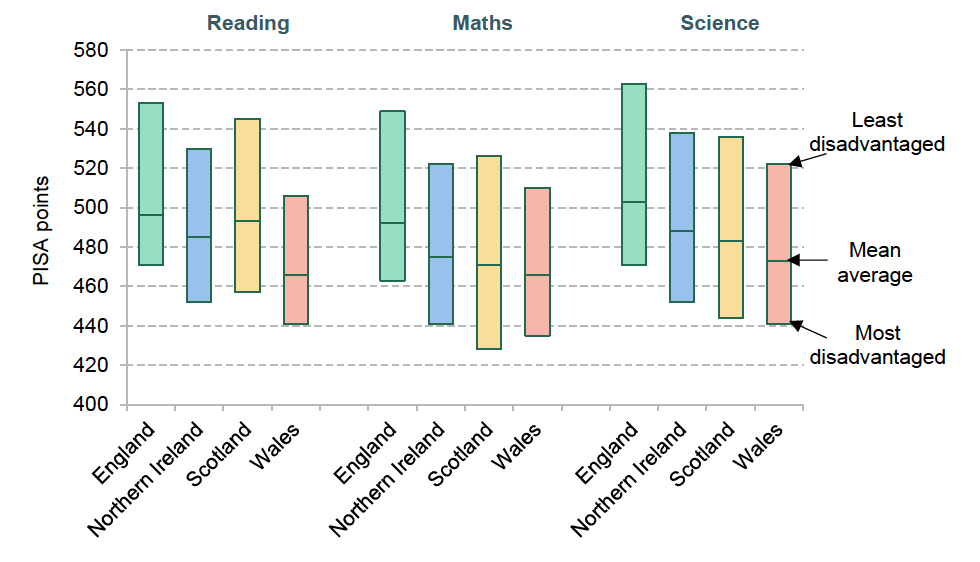

Equally concerning are the level of performance of disadvantaged pupils and the state of educational inequalities in Wales, which are visible in both PISA and GCSE results. Figure 2 shows the mean PISA scores in each nation and subject for those in the most and least disadvantaged groups (bottom and top quartiles of the OECD’s index of economic, social and cultural status, ESCS), together with the mean scores for all children, in 2022.

Figure 2. Average PISA scores for most disadvantaged, least disadvantaged and all by nation and subject area in 2022

Source: Department for Education, 2023.

The gaps in performance between the most and least disadvantaged groups are broadly similar across England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and are perhaps a little larger for Scotland in reading and maths. However, the difference in levels between England and other nations of the UK by level of disadvantage is very stark. For the least disadvantaged group, we see that scores in England are about 25–30 PISA points higher than in the other nations of the UK, on average. Some of this is likely to be explained by higher incomes at the top end of the spectrum in England. However, it is notable that scores for the least disadvantaged 25% of children in Wales are only barely above the average for all children in England.

At the other end of the distribution, disadvantaged children in Wales have the lowest scores across all four nations for reading and science (and the second-lowest for maths, just above the very low maths scores for disadvantaged children in Scotland). Disadvantaged children in England score about 30 points higher, on average, than disadvantaged children in Wales. This is a large gap and equivalent to about 30% of a standard deviation. Indeed, the performance of disadvantaged children in England is either above or similar to the average for all children in Wales.

Why we should care about the reasons for low PISA scores

Before thinking about the factors driving low PISA scores in Wales and policy implications, it is important to ask whether PISA scores actually matter. There are no prizes for a high PISA ranking, except kudos, and there are no immediate consequences, except pressure on policymakers. It is also important to focus on the actual scores, rather than rankings or relative performance. Education is not a zero-sum game. If all countries saw an equally large rise in scores, we are all likely to be better off.

PISA scores matter because they are a valuable and comparable indicator of young people’s skills in reading, numeracy and science. These are fundamental skills for accessing the rest of the curriculum and for achieving education qualifications. There is an enormous body of evidence that shows how skills and educational qualifications lead to greater chances of employment, higher earnings, higher productivity, improved health outcomes, lower crime, and the list goes on as evidence improves (Hanushek et al., 2015; Psacharopoulos and Patrinos, 2018).

Furthermore, there is a great deal of evidence showing that Welsh young people experience worse educational and labour market outcomes after leaving school than young people in the rest of the UK. A recent EPI/SKOPE report shows that young people in Wales have the lowest participation in higher education across the UK, with Welsh boys seeing particularly poor trends over the last 15 years (Robson et al., 2024). We also see that the share of young people who are not in education, employment or training (NEET) is higher in Wales than in the rest of the UK. In 2022–23 , 11% of 16- to 18-year-olds in Wales were NEET, as compared with 5–9% across the rest of the UK. A similar picture emerges for 19- to 24-year-olds. In the labour market, we also see that Welsh young people from working-class backgrounds have lower earnings and lower employment levels than working-class young people from other UK nations.

The inescapable truth is that disadvantaged pupils in Wales have low skill levels and low levels of educational attainment. This drives a high disadvantage gap, reduces opportunities in the labour market and perpetuates inequalities. This will act as a drag on growth and living standards.

3. Explanations for lower performance in Wales

In this section, we gradually examine the potential explanations for lower levels of educational performance in Wales, including the statistical biases and the roles of poverty, ethnic mix, resources, the curriculum, accountability and assessments.

Statistical concerns and biases

To what extent do lower PISA scores in Wales reflect statistical concerns and biases? Some caution is always needed when interpreting exact changes across countries over time, particularly as PISA scores are based on a sample of children in each nation across each cycle. There are also sources of potential bias specific to the UK and Wales, with the OECD warning that low response rates could be creating biases within the UK this year. Jerrim (2023) has written about the curious issue of the implausibly low scores of pupils taking the test in Welsh, which could be biasing Welsh scores downwards. However, such biases are likely to be modest (less than 10 points) and have been known to affect previous years (Jerrim, Lopez-Agudo and Marcenaro-Gutierrez, 2022).

In general, one should focus on the general trends and levels over time. For Wales, this is a picture of low test scores across all three subject areas, below the OECD average and lower than the rest of the UK. Furthermore, as shown below, the fact that we see higher GCSE inequalities and worse post-16 educational and labour market outcomes in Wales strongly suggests that PISA is capturing a real issue in the Welsh education system.

Higher poverty is not the explanation

There will be differences between disadvantaged children in Wales and England that explain some of these differences in skill levels. However, there is likely to be a high degree of socio-economic similarity between the disadvantaged groups across England and Wales (we look at differences by ethnic background below). These groups are mainly made up of families reliant on means-tested benefits or on minimum wage levels, which will be very similar across the two nations. As of January 2019, the share of children eligible for free school meals was about 18% in Wales , which is only slightly larger than the 15% in England . Furthermore, about 8–9% of pupils were persistently eligible for free school meals (FSM) across both nations, suggesting similar levels of persistent poverty (Cardim-Dias and Sibieta, 2022). Transitional protections under universal credit make it difficult to present more recent statistics in a comparable way.

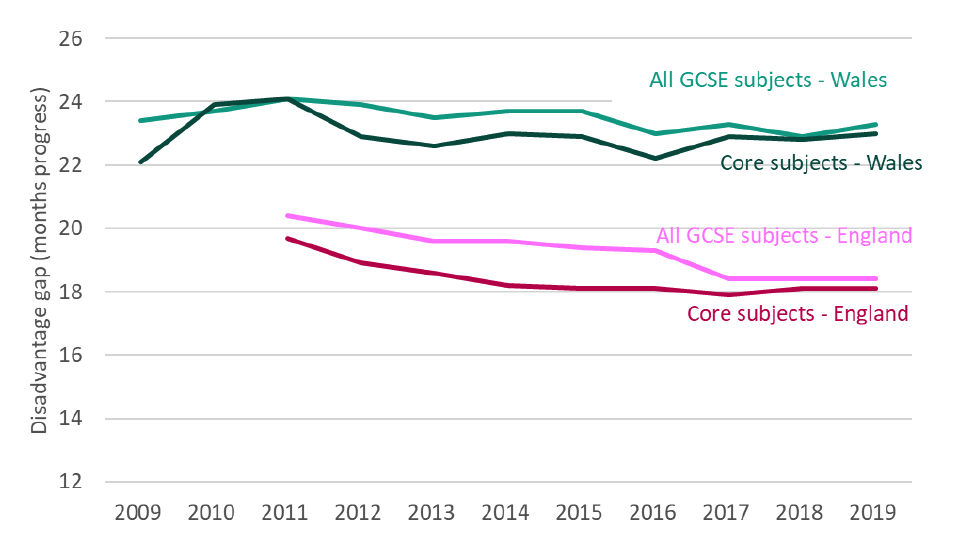

Differences in GCSE specifications between England and Wales make it difficult to compare absolute or raw results. However, Cardim-Dias and Sibieta (2022) show that one can produce reliable comparisons of inequalities in GCSE results, and the gap in performance between disadvantaged and other pupils. This analysis presents the disadvantage gap in terms of months of educational progress, where 11 months would be the expected difference in performance between a child born in September and one born in August.

As shown in Figure 3, Cardim-Dias and Sibieta (2022) show higher inequalities in GCSE results in Wales than in England. Before the pandemic, disadvantaged pupils in Wales were the equivalent of 22–23 months of educational progress behind their peers, compared with a gap of 18 months in England.

Figure 3.Disadvantage gap in GCSE results in Wales and England over time (months of educational progress; disadvantaged defined as ever eligible for FSM in past six years)

Note: Core subjects are English/Welsh, maths and science.

Source: Reproduced from Cardim-Dias and Sibieta (2022) with kind permission.

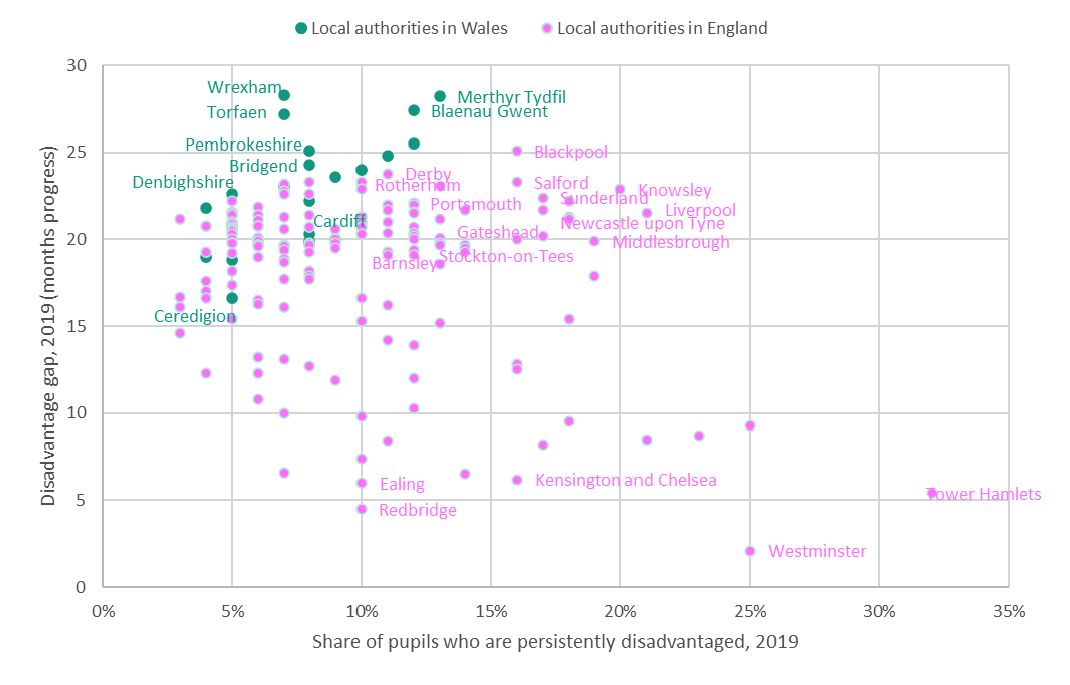

The results are even more stark at a local level, as shown in Figure 4. Across England and Wales, the local authorities with the worst performance for disadvantaged pupils are practically all in Wales. Before the pandemic, there were seven local authorities in Wales where disadvantaged pupils were at least 25 months behind their peers at the national level: Torfaen, Wrexham, Blaenau Gwent, Merthyr Tydfil, Neath Port Talbot, Rhondda Cynon Taf and Pembrokeshire. In England, this was only the case for Blackpool. Furthermore, there are many local authorities in England with similar levels of deprivation and demographics to deprived areas in Wales, but which manage to achieve a lower disadvantage gap – for example, Salford, Gateshead and Portsmouth. There are also places with much higher levels of persistent disadvantage that achieve lower disadvantage gaps, such as Liverpool and Newcastle. The low performance of disadvantaged pupils in Wales is simply not an inevitable result of high levels of deprivation.

Figure 4. Relationship between persistent disadvantage and the disadvantage gap across local authorities in Wales and England

Note: Pupils are classed as persistently disadvantaged if they were eligible for free school meals for 80% of their time in school. Disadvantage gap is measured in terms of GCSE results.

To be clear, the overall level of the disadvantage gap and educational inequalities in England are substantial, with a national disadvantage gap of 18 months before the pandemic and much evidence to suggest that this has been getting even worse over recent years (Babbini et al., 2023). But the picture in Wales looks even worse than this. This greater disadvantage gap cannot be explained by higher levels of disadvantage in Wales. Areas of England with similar or higher levels of disadvantage manage to achieve lower levels of educational inequality. The explanation must lie elsewhere.

Role of immigrants and ethnic make-up

Perhaps the most significant difference is the ethnic make-up of each nation. Over 30% of pupils in England are from minority ethnic backgrounds, compared with about 10% in Wales . Over 20% of 15-year-olds in England were from first- or second-generation immigrant backgrounds in 2022, compared with 10% in Wales (OECD, 2023). This matters, as the evidence clearly shows that ethnic minorities and those from immigrant backgrounds generally perform very well in England (Wilson, Burgess and Briggs, 2011; OECD, 2023). These differences seem likely to be accentuated amongst the disadvantaged group, and may explain some of the lower performance in Wales. However, there are reasons to doubt that this explains a large element of lower skill levels in Wales.

According to PISA, non-immigrants in England score about 30 PISA points higher in maths than non-immigrants in Wales. We also see that immigrants score about 20 PISA points higher in England than in Wales. Immigrants and non-immigrants alike have higher levels of performance in England. Indeed, the high performance of immigrants is an under-appreciated success of the English education system. As Freedman (2024) has pointed out, England is the only European country where second-generation immigrants outperform non-immigrants in PISA. If second-generation immigrants in England were a country, they would have similar maths scores to high-performing countries such as Canada and Estonia, and be not far behind Korea and Japan.

How much do resources matter?

Resources and spending also differ across the UK (Sibieta, 2023). In Scotland, spending per pupil has long been higher and class sizes lower than in the rest of the UK (Jerrim and Sibieta, 2021). Following a further boost since 2018, spending per pupil in Scotland is at least 18% or £1,300 higher than elsewhere in the UK. Spending levels and trends are more similar in Wales, England and Northern Ireland. There were real-terms cuts to spending per pupil between 2010 and 2019, which are now being gradually reversed (Sibieta, 2023).

With England showing higher levels of skills than high-spending Scotland, one naturally asks whether school spending matters all that much. The answer is still yes. Correlations of spending across time and countries provide little information on the true effects of higher spending on educational outcomes. We have excellent evidence showing increasing levels of school spending does improve educational outcomes, and probably more so for disadvantaged students (Jackson and Mackevicius, 2024). This remains relevant and can help us interpret differences across nations.

In Scotland, we see historical levels of higher spending and recent large increases. An entirely plausible explanation is that higher levels of skills in Scotland in the past could be partly explained by greater resources. Recent declines could be explained by negative effects of reforms outweighing the effects of extra spending, and potentially by reforms reducing the bang-for-buck from extra resources.

In England, we see stable scores at a time of reduced spending per pupil and resilience in the face of a global pandemic. A very plausible explanation is that reforms to the system, such as the knowledge-rich curriculum and focus on basic literacy and numeracy, could have had positive effects, which may have been slightly diminished by reduced spending. This has the additional implication that the current English system may well be characterised by high bang-for-buck from extra spending.

This has some important lessons for policymakers in Wales considering the role of extra resources. How much you spend and how you spend it are often seen as competing factors. This is an entirely false trade-off. They both matter in complementary ways. A well-functioning and high-performing system is likely to generate large gains from extra spending. Throwing money at a poorly-performing system will likely produce disappointing results.

Curriculum changes: knowledge versus skills

One of the biggest school policy differences across the four nations of the UK has been curriculum reform. Scotland (from 2010) and Northern Ireland (from 2007) have already implemented skills-based curricula, which focus on the development of skills and competencies. The new Curriculum for Wales , implemented from 2022 onwards, takes a similar approach and is partly modelled on the Scottish Curriculum for Excellence. The National Curriculum in England is very different. The most recent version was implemented from 2014 onwards and focuses on whether pupils have specific elements of knowledge.

The Curriculum for Wales aims to develop general skills and defines four key purposes:

- ambitious, capable learners, ready to learn throughout their lives;

- enterprising, creative contributors, ready to play a full part in life and work;

- ethical, informed citizens of Wales and the world;

- healthy, confident individuals, ready to lead fulfilling lives as valued members of society.

Learning is organised into six different areas of learning (combining many traditional subject domains). A high emphasis is also placed on health and well-being. Schools then have significant autonomy to define the specific elements of their own curriculum as long as they are progressing towards the general definitions of skills. This is intended to achieve a broad and balanced curriculum.

These are of course very noble and sensible aims. The trouble is that defining the curriculum in terms of general skills might not actually be a good way to develop those skills in the first place. Whilst many of the skills seem like good long-term goals for an education system, Christodoulou (2023) argues that it is more effective to break those skills down into the teaching of specific elements of knowledge. Assessing generic skills is also incredibly difficult. As a result, skill-based curricula can lead to significant inequalities in the curriculum content that pupils are exposed to, and in the ways in which they are assessed. Indeed, based on pilots of the new curriculum, education researchers in Wales have already warned that the new curriculum risks exacerbating existing inequalities without external accountability on curriculum design and assessment, and extra investment (Power, Newton and Taylor, 2020).

Paterson (2023) also argues that the reduction in science and maths scores in Scotland and Northern Ireland, alongside stable reading scores, is the pattern one might expect following the introduction of skills-based curricula. Reading is a relatively general skill that parents can assist with. Maths and science require more specific knowledge that parents might find harder to impart. This seems like a reasonable conclusion. However, it would be near impossible to definitively conclude that it is the adoption of skills-based curricula that has led to lower scores in Scotland and Northern Ireland, and that a knowledge-based curriculum has improved scores in England. Correlation is not causation. Furthermore, the improvements in reading in England appear longstanding, dating back to 2006 at least, and might not just be about the adoption of the new National Curriculum. The improvements may reflect the widespread adoption of synthetic phonics following the Rose Report in 2006, which has been shown to have had positive effects (Machin, McNally and Viarengo, 2018).

The trouble is, as argued by Crehan (2023), declines have happened in essentially every country that has adopted such skills-based curricula – for example, France, Finland, Australia and New Zealand, with the last thinking about ways to introduce specific knowledge elements into its curriculum.

Lastly, there is also no evidence to suggest that policymakers in Wales have been successful in achieving the broader aim of maximising pupil well-being. The 2022 PISA report for Wales (Ingram et al., 2023) shows that pupils in Wales report a lower score for overall life satisfaction than the OECD average and that a lower-than-average share of pupils felt like they belonged in school. Pupils reporting higher levels of life satisfaction and belonging tended to be those achieving higher scores on PISA tests.

At the very least, all this must leave us wary about the introduction of the skills-based Curriculum for Wales. Maybe Wales will totally buck the international trend. However, there is no good evidence showing that a skills-based curriculum will be able to turn around low scores and high inequalities seen in Wales.

Accountability and assessment: not measuring up

Another key difference across the four nations has been approaches to accountability and assessment. In England, there has long been a focus on high-stakes accountability, either through league tables, school-by-school data comparisons or Ofsted inspections with single-word judgements (often with high consequences for schools and their leadership teams). This can have benefits, in terms of high levels of accountability, but can also create perverse incentives to teach to the test, and the problems associated with high-pressured school inspections are now well known.

Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland abolished league tables long ago. Some evidence suggests this had a small negative effect in Wales (Burgess, Wilson and Worth, 2013), and a more general school categorisation system was introduced about 10 years ago. This has since been abolished and replaced by a system of self-evaluation by schools.

Since 2013, pupils aged 7–14 have sat literacy and numeracy tests of one form or another in Wales. However, the results from these have rarely been published in ways that allow us to track average skills levels or inequalities over time. For England, we have significant data on pupil skill levels from tests such as the phonics check and Key Stage 2 tests , and there are clear metrics comparing school performance with national and low benchmarks at pretty much every stage of education. Historically, such test scores have been used as part of school league tables. However, more important are the ways in which the data are used to track overall performance over time, to understand inequalities across pupils and areas, and for schools to compare their own levels with those of others. This approach to data on school comparisons was briefly part of the Welsh school system, but is not really encouraged any more. The Welsh Government has recently published data showing falling numeracy and reading levels since the pandemic, and it plans to publish more on inequalities in Spring 2024. This should ideally become a regular and systematic overview of skills levels and inequalities across time and place and enable schools to do comparisons to aid their understanding.