How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 8 min read

Critical Thinking

Developing the right mindset and skills.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

We make hundreds of decisions every day and, whether we realize it or not, we're all critical thinkers.

We use critical thinking each time we weigh up our options, prioritize our responsibilities, or think about the likely effects of our actions. It's a crucial skill that helps us to cut out misinformation and make wise decisions. The trouble is, we're not always very good at it!

In this article, we'll explore the key skills that you need to develop your critical thinking skills, and how to adopt a critical thinking mindset, so that you can make well-informed decisions.

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is the discipline of rigorously and skillfully using information, experience, observation, and reasoning to guide your decisions, actions, and beliefs. You'll need to actively question every step of your thinking process to do it well.

Collecting, analyzing and evaluating information is an important skill in life, and a highly valued asset in the workplace. People who score highly in critical thinking assessments are also rated by their managers as having good problem-solving skills, creativity, strong decision-making skills, and good overall performance. [1]

Key Critical Thinking Skills

Critical thinkers possess a set of key characteristics which help them to question information and their own thinking. Focus on the following areas to develop your critical thinking skills:

Being willing and able to explore alternative approaches and experimental ideas is crucial. Can you think through "what if" scenarios, create plausible options, and test out your theories? If not, you'll tend to write off ideas and options too soon, so you may miss the best answer to your situation.

To nurture your curiosity, stay up to date with facts and trends. You'll overlook important information if you allow yourself to become "blinkered," so always be open to new information.

But don't stop there! Look for opposing views or evidence to challenge your information, and seek clarification when things are unclear. This will help you to reassess your beliefs and make a well-informed decision later. Read our article, Opening Closed Minds , for more ways to stay receptive.

Logical Thinking

You must be skilled at reasoning and extending logic to come up with plausible options or outcomes.

It's also important to emphasize logic over emotion. Emotion can be motivating but it can also lead you to take hasty and unwise action, so control your emotions and be cautious in your judgments. Know when a conclusion is "fact" and when it is not. "Could-be-true" conclusions are based on assumptions and must be tested further. Read our article, Logical Fallacies , for help with this.

Use creative problem solving to balance cold logic. By thinking outside of the box you can identify new possible outcomes by using pieces of information that you already have.

Self-Awareness

Many of the decisions we make in life are subtly informed by our values and beliefs. These influences are called cognitive biases and it can be difficult to identify them in ourselves because they're often subconscious.

Practicing self-awareness will allow you to reflect on the beliefs you have and the choices you make. You'll then be better equipped to challenge your own thinking and make improved, unbiased decisions.

One particularly useful tool for critical thinking is the Ladder of Inference . It allows you to test and validate your thinking process, rather than jumping to poorly supported conclusions.

Developing a Critical Thinking Mindset

Combine the above skills with the right mindset so that you can make better decisions and adopt more effective courses of action. You can develop your critical thinking mindset by following this process:

Gather Information

First, collect data, opinions and facts on the issue that you need to solve. Draw on what you already know, and turn to new sources of information to help inform your understanding. Consider what gaps there are in your knowledge and seek to fill them. And look for information that challenges your assumptions and beliefs.

Be sure to verify the authority and authenticity of your sources. Not everything you read is true! Use this checklist to ensure that your information is valid:

- Are your information sources trustworthy ? (For example, well-respected authors, trusted colleagues or peers, recognized industry publications, websites, blogs, etc.)

- Is the information you have gathered up to date ?

- Has the information received any direct criticism ?

- Does the information have any errors or inaccuracies ?

- Is there any evidence to support or corroborate the information you have gathered?

- Is the information you have gathered subjective or biased in any way? (For example, is it based on opinion, rather than fact? Is any of the information you have gathered designed to promote a particular service or organization?)

If any information appears to be irrelevant or invalid, don't include it in your decision making. But don't omit information just because you disagree with it, or your final decision will be flawed and bias.

Now observe the information you have gathered, and interpret it. What are the key findings and main takeaways? What does the evidence point to? Start to build one or two possible arguments based on what you have found.

You'll need to look for the details within the mass of information, so use your powers of observation to identify any patterns or similarities. You can then analyze and extend these trends to make sensible predictions about the future.

To help you to sift through the multiple ideas and theories, it can be useful to group and order items according to their characteristics. From here, you can compare and contrast the different items. And once you've determined how similar or different things are from one another, Paired Comparison Analysis can help you to analyze them.

The final step involves challenging the information and rationalizing its arguments.

Apply the laws of reason (induction, deduction, analogy) to judge an argument and determine its merits. To do this, it's essential that you can determine the significance and validity of an argument to put it in the correct perspective. Take a look at our article, Rational Thinking , for more information about how to do this.

Once you have considered all of the arguments and options rationally, you can finally make an informed decision.

Afterward, take time to reflect on what you have learned and what you found challenging. Step back from the detail of your decision or problem, and look at the bigger picture. Record what you've learned from your observations and experience.

Critical thinking involves rigorously and skilfully using information, experience, observation, and reasoning to guide your decisions, actions and beliefs. It's a useful skill in the workplace and in life.

You'll need to be curious and creative to explore alternative possibilities, but rational to apply logic, and self-aware to identify when your beliefs could affect your decisions or actions.

You can demonstrate a high level of critical thinking by validating your information, analyzing its meaning, and finally evaluating the argument.

Critical Thinking Infographic

See Critical Thinking represented in our infographic: An Elementary Guide to Critical Thinking .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

Book Insights

Work Disrupted: Opportunity, Resilience, and Growth in the Accelerated Future of Work

Jeff Schwartz and Suzanne Riss

Zenger and Folkman's 10 Fatal Leadership Flaws

Avoiding Common Mistakes in Leadership

Add comment

Comments (1)

priyanka ghogare

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Latest Updates

Pain Points Podcast - Presentations Pt 2

NEW! Pain Points - How Do I Decide?

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Finding the Best Mix in Training Methods

Using Mediation To Resolve Conflict

Resolving conflicts peacefully with mediation

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Developing personal accountability.

Taking Responsibility to Get Ahead

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

- Interactive Videos

- Overview & Comparison

- THINKING PRO - Curriculum Unit

- Benefits for School Admin

- Benefits for Teachers

- Social Studies

- English Language Learners

- Foundation Giving

- Corporate Giving

- Individual Giving

- Partnerships

Developing Critical Thinking Skills

Critical thinking doesn’t come naturally

Wherever we go in life, we must think critically when it matters the most. From our first days of school, through formal education, into the workplace, and in the civic choices we make in our communities -- critical thinking is a vital skill to have.

It’s important to consider critical thinking as just that: a skill. Just as we don’t naturally improve at playing the banjo or running marathons as we grow older, critical thinking doesn’t simply blossom with maturation. Like most other skills, it must be nurtured, practiced, and developed if we wish to make the most of it.

To fully illustrate this concept, educational psychologists Linda Elder and Richard Paul (2010) have developed a theory of stages of development in critical thinking . It makes clear that people aren’t born critical thinkers, but rather progress through several more-or-less universal stages of critical thinking development:

- The “ Unreflective Thinker ” is largely unaware of the importance of critical thinking in all facets of life, and doesn’t consistently practice any critical thinking methods.

- The “ Challenged Thinker ” is enlightened, having been made aware of the importance of critical thinking, and of their own lack of critical thinking skills.

- The “ Beginning Thinker ” has committed to making critical thinking a part of their life, and has begun to self-monitor and observe their own thinking practices and habits.

- The “ Practicing Thinker ” understands what types of changes they must make to their “old” patterns of thinking, and are committed to actively practicing critical thinking.

- The “ Advanced Thinker ” has established excellent critical thinking habits, and are beginning to reap the benefits of applying these habits throughout their lives.

Stages of critical thinking

We could all benefit from sharpening our critical thinking skills. Furthermore, as educators, leaders, parents, or team members, we want to see critical thinking skills utilized fully by our students, employees, children, and teammates. So how can we encourage the development of this skill, moving from “unreflective thinkers” to “advanced thinkers”?

There are, of course, many answers. Even moving from the first to the second stage of development is quite the daunting task. Wolcott Lynch (2001), an educational consulting company, has proposed a sequence of steps that can help thinkers to better engage with professional, personal, and civic problems:

- Identify the problem, relevant information, and uncertainties.

- Explore interpretations and connections.

- Prioritize alternatives and communicate conclusions.

- Integrate , monitor , and refine strategies for re-addressing the problem.

These steps provide a great starting place for helping ourselves and the other thinkers in our lives to develop methodical practices of critical thinking. Do you have any suggestions for other ways to nourish and encourage critical thinking? Share your methods and observations in the comments below.

Elder, L. with Paul, R. (2010). Critical Thinking Development: A Stage Theory. Accessed 01 September 2016 from https://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/critical-thinking-development-a-stage-theory/483

Lynch, C. L. and Wolcott, S. K. (2001). Helping Your Students Develop Critical Thinking Skills. Accessed 01 September 2016 from https://www.scribd.com/document/522423747/IDEA-Paper-37

- Programs & Services

- Delphi Center

Ideas to Action (i2a)

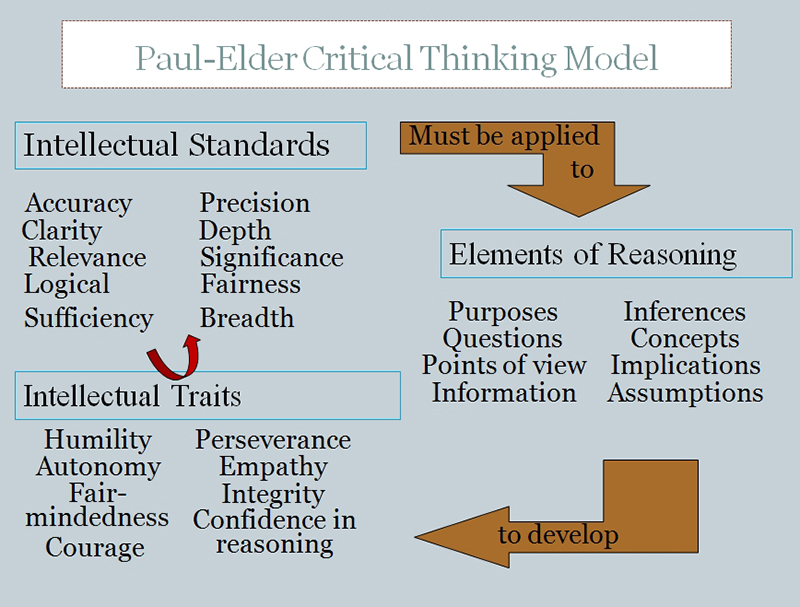

- Paul-Elder Critical Thinking Framework

Critical thinking is that mode of thinking – about any subject, content, or problem — in which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully taking charge of the structures inherent in thinking and imposing intellectual standards upon them. (Paul and Elder, 2001). The Paul-Elder framework has three components:

- The elements of thought (reasoning)

- The intellectual standards that should be applied to the elements of reasoning

- The intellectual traits associated with a cultivated critical thinker that result from the consistent and disciplined application of the intellectual standards to the elements of thought

According to Paul and Elder (1997), there are two essential dimensions of thinking that students need to master in order to learn how to upgrade their thinking. They need to be able to identify the "parts" of their thinking, and they need to be able to assess their use of these parts of thinking.

Elements of Thought (reasoning)

The "parts" or elements of thinking are as follows:

- All reasoning has a purpose

- All reasoning is an attempt to figure something out, to settle some question, to solve some problem

- All reasoning is based on assumptions

- All reasoning is done from some point of view

- All reasoning is based on data, information and evidence

- All reasoning is expressed through, and shaped by, concepts and ideas

- All reasoning contains inferences or interpretations by which we draw conclusions and give meaning to data

- All reasoning leads somewhere or has implications and consequences

Universal Intellectual Standards

The intellectual standards that are to these elements are used to determine the quality of reasoning. Good critical thinking requires having a command of these standards. According to Paul and Elder (1997 ,2006), the ultimate goal is for the standards of reasoning to become infused in all thinking so as to become the guide to better and better reasoning. The intellectual standards include:

Intellectual Traits

Consistent application of the standards of thinking to the elements of thinking result in the development of intellectual traits of:

- Intellectual Humility

- Intellectual Courage

- Intellectual Empathy

- Intellectual Autonomy

- Intellectual Integrity

- Intellectual Perseverance

- Confidence in Reason

- Fair-mindedness

Characteristics of a Well-Cultivated Critical Thinker

Habitual utilization of the intellectual traits produce a well-cultivated critical thinker who is able to:

- Raise vital questions and problems, formulating them clearly and precisely

- Gather and assess relevant information, using abstract ideas to interpret it effectively

- Come to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, testing them against relevant criteria and standards;

- Think open-mindedly within alternative systems of thought, recognizing and assessing, as need be, their assumptions, implications, and practical consequences; and

- Communicate effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex problems

Paul, R. and Elder, L. (2010). The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools. Dillon Beach: Foundation for Critical Thinking Press.

- SACS & QEP

- Planning and Implementation

- What is Critical Thinking?

- Why Focus on Critical Thinking?

- Culminating Undergraduate Experience

- Community Engagement

- Frequently Asked Questions

- What is i2a?

Copyright © 2012 - University of Louisville , Delphi Center

Developing Critical Thinking

- Posted January 10, 2018

- By Iman Rastegari

In a time where deliberately false information is continually introduced into public discourse, and quickly spread through social media shares and likes, it is more important than ever for young people to develop their critical thinking. That skill, says Georgetown professor William T. Gormley, consists of three elements: a capacity to spot weakness in other arguments, a passion for good evidence, and a capacity to reflect on your own views and values with an eye to possibly change them. But are educators making the development of these skills a priority?

"Some teachers embrace critical thinking pedagogy with enthusiasm and they make it a high priority in their classrooms; other teachers do not," says Gormley, author of the recent Harvard Education Press release The Critical Advantage: Developing Critical Thinking Skills in School . "So if you are to assess the extent of critical-thinking instruction in U.S. classrooms, you’d find some very wide variations." Which is unfortunate, he says, since developing critical-thinking skills is vital not only to students' readiness for college and career, but to their civic readiness, as well.

"It's important to recognize that critical thinking is not just something that takes place in the classroom or in the workplace, it's something that takes place — and should take place — in our daily lives," says Gormley.

In this edition of the Harvard EdCast, Gormley looks at the value of teaching critical thinking, and explores how it can be an important solution to some of the problems that we face, including "fake news."

About the Harvard EdCast

The Harvard EdCast is a weekly series of podcasts, available on the Harvard University iT unes U page, that features a 15-20 minute conversation with thought leaders in the field of education from across the country and around the world. Hosted by Matt Weber and co-produced by Jill Anderson, the Harvard EdCast is a space for educational discourse and openness, focusing on the myriad issues and current events related to the field.

An education podcast that keeps the focus simple: what makes a difference for learners, educators, parents, and communities

Related Articles

Roots of the School Gardening Movement

Student-centered learning, reading and the common core.

Critical Thinking

- Reference work entry

- Cite this reference work entry

- Héfer Bembenutty 3

438 Accesses

Information processing ; Logical reasoning ; Memory ; Metacognition ; Problem-solving ; Rationalizing ; Reasoning ; Reflective judgment; Thinking

Critical thinking refers to individuals’ ability to engage reflectively in high-level information processing and entails producing, evaluating, and reflecting on the evidence, facts, syllogisms, and reasoning.

Description

Thinking involves the process of perceiving, storage, processing, transforming, retrieving, remembering, and using information storage in the memory. The process of thinking starts with perception of stimuli, processing the information in the working memory, storage them in the long-term memory, and retrieving the information when it is needed. Individuals think about actual objects such a dog or imaginary objects such as Peter Pan. However, thinking reflectively and evaluating evidence is a unique characteristic of human beings. Children and adults do not act only based on impulse and instincts; rather, they...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Hirsch, E. D. (1996). The schools we need and why we don’t have them . New York: Doubleday.

Google Scholar

King, P. M., & Kitchener, K. S. (2004). The reflective judgment model: Twenty years of research on epistemic cognition (Chapter 3). In B. K. Hofer & P. R. Pintrich (Eds.), Personal epistemology: The psychology of beliefs about knowledge and knowing . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Piaget, J. (1963). Origins of intelligence in children . New York: Norton.

Pressley, M., Barkowski, J. G., & Schneider, W. (1987). Cognitive strategies: Good strategy users coordinate metacognition and knowledge. In R. Vasta & G. Whitehurst (Eds.), Annals of child development (Vol. 5, pp. 89–129). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Santrock, J. W. (2007). Child development (11th ed.). Boston: McGraw Hill.

Woolfolk, A. (2005). Educational psychology (9th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Rosenthal, T. L. (1974). Observational learning of rule-governed behavior by children. Psychological Bulletin, 81 (1), 24–42.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Secondary Education and Youth Services, Powdermaker Hall 150-P, Queens College of the City University of New York, 65-30 Kissena Boulevard, Flushing, NY, 11367-1597, USA

Héfer Bembenutty

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Héfer Bembenutty .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Neurology, Learning and Behavior Center, 230 South 500 East, Suite 100, Salt Lake City, Utah, 84102, USA

Sam Goldstein Ph.D.

Department of Psychology MS 2C6, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, 22030, USA

Jack A. Naglieri Ph.D. ( Professor of Psychology ) ( Professor of Psychology )

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2011 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Bembenutty, H. (2011). Critical Thinking. In: Goldstein, S., Naglieri, J.A. (eds) Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-79061-9_733

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-79061-9_733

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-0-387-77579-1

Online ISBN : 978-0-387-79061-9

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Schools & departments

Critical thinking

Advice and resources to help you develop your critical voice.

Developing critical thinking skills is essential to your success at University and beyond. We all need to be critical thinkers to help us navigate our way through an information-rich world.

Whatever your discipline, you will engage with a wide variety of sources of information and evidence. You will develop the skills to make judgements about this evidence to form your own views and to present your views clearly.

One of the most common types of feedback received by students is that their work is ‘too descriptive’. This usually means that they have just stated what others have said and have not reflected critically on the material. They have not evaluated the evidence and constructed an argument.

What is critical thinking?

Critical thinking is the art of making clear, reasoned judgements based on interpreting, understanding, applying and synthesising evidence gathered from observation, reading and experimentation. Burns, T., & Sinfield, S. (2016) Essential Study Skills: The Complete Guide to Success at University (4th ed.) London: SAGE, p94.

Being critical does not just mean finding fault. It means assessing evidence from a variety of sources and making reasoned conclusions. As a result of your analysis you may decide that a particular piece of evidence is not robust, or that you disagree with the conclusion, but you should be able to state why you have come to this view and incorporate this into a bigger picture of the literature.

Being critical goes beyond describing what you have heard in lectures or what you have read. It involves synthesising, analysing and evaluating what you have learned to develop your own argument or position.

Critical thinking is important in all subjects and disciplines – in science and engineering, as well as the arts and humanities. The types of evidence used to develop arguments may be very different but the processes and techniques are similar. Critical thinking is required for both undergraduate and postgraduate levels of study.

What, where, when, who, why, how?

Purposeful reading can help with critical thinking because it encourages you to read actively rather than passively. When you read, ask yourself questions about what you are reading and make notes to record your views. Ask questions like:

- What is the main point of this paper/ article/ paragraph/ report/ blog?

- Who wrote it?

- Why was it written?

- When was it written?

- Has the context changed since it was written?

- Is the evidence presented robust?

- How did the authors come to their conclusions?

- Do you agree with the conclusions?

- What does this add to our knowledge?

- Why is it useful?

Our web page covering Reading at university includes a handout to help you develop your own critical reading form and a suggested reading notes record sheet. These resources will help you record your thoughts after you read, which will help you to construct your argument.

Reading at university

Developing an argument

Being a university student is about learning how to think, not what to think. Critical thinking shapes your own values and attitudes through a process of deliberating, debating and persuasion. Through developing your critical thinking you can move on from simply disagreeing to constructively assessing alternatives by building on doubts.

There are several key stages involved in developing your ideas and constructing an argument. You might like to use a form to help you think about the features of critical thinking and to break down the stages of developing your argument.

Features of critical thinking (pdf)

Features of critical thinking (Word rtf)

Our webpage on Academic writing includes a useful handout ‘Building an argument as you go’.

Academic writing

You should also consider the language you will use to introduce a range of viewpoints and to evaluate the various sources of evidence. This will help your reader to follow your argument. To get you started, the University of Manchester's Academic Phrasebank has a useful section on Being Critical.

Academic Phrasebank

Developing your critical thinking

Set yourself some tasks to help develop your critical thinking skills. Discuss material presented in lectures or from resource lists with your peers. Set up a critical reading group or use an online discussion forum. Think about a point you would like to make during discussions in tutorials and be prepared to back up your argument with evidence.

For more suggestions:

Developing your critical thinking - ideas (pdf)

Developing your critical thinking - ideas (Word rtf)

Published guides

For further advice and more detailed resources please see the Critical Thinking section of our list of published Study skills guides.

Study skills guides

This article was published on 2024-02-26

Parents' Guide

Introduction, critical thinking development: ages 5 to 9.

Critical thinking must be built from a solid foundation. Although children aged five to nine are not yet ready to take on complicated reasoning or formulate detailed arguments, parents can still help their children lay a foundation for critical thinking.

In order to develop high-level critical thinking skills later in life, five- to nine-year-old children must first make progress along four different tracks. This includes developing basic reasoning skills and interests, building self-esteem, learning emotional management skills, and internalizing social norms that value critical thinking. The following sections will discuss the importance of these foundational aspects of critical thinking and offer parents guidance in how to support their young children’s development.

1. Logic and Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is different from logical thinking. logical thinking is like math: it involves formal reasoning skills that can only be learned later in life. in contrast, critical thinking builds on everyday reasoning. so parents should guide their children’s critical thinking development from a very young age..

Formal logic is an important part of critical thinking, but ultimately critical thinking involves habits and skills going far beyond the domain of logic. Children are able to develop their critical faculties not from logical analysis, but everyday reasoning.

There are three main factors to keep in mind in differentiating logic from the everyday reasoning that underpins critical thinking.

First, logic is not a natural human trait. If logic were natural, we wouldn’t have to learn how to reason, and math wouldn’t be considered so difficult in school. The natural reasoning displayed by children is often founded on sensory experiences and marred by the cognitive biases discussed in the introduction. Consider this example. Someone says: “If it rains, I’ll take my umbrella with me.” And then a moment later adds: “It’s not raining.” What may we conclude? The vast majority of people — including both adults and children old enough to understand the question — will conclude that the person will not take an umbrella. In context, that is a reasonable conclusion to draw.

Logic is not natural to humans and can only be acquired through learning.

But from a purely logical perspective, it does not follow. The fact that if it does rain, the speaker will take an umbrella implies nothing, strictly speaking, about what will happen in the case that it is not raining. Logic, the cognitive capacity for formal and reliable deduction, is not natural to humans. We can only acquire it through learning—and only at an age when the cognitive system and brain development allow for such learning (between ages 12 and 15).

Second, although logic is not natural, it can be taught with varying degrees of success, according to personality, cognitive profile, and so on. Multiple developmental psychology studies since Piaget have shown that our cognitive system can only become proficient in logical analysis later on, and with the correct training.

Third, if parents train children from ages five to nine to make more or less complex logical deductions, no deep knowledge is acquired. At a young age, the cognitive system does not yet have the capacity to discern logical invariables (i.e., the ability to reproduce a line of reasoning in a variable context).

This is why we only explain mathematical principles to children when they are 13 to 14 years old. But again parents can encourage the basics of critical thinking at an early age by promoting social factors like self-esteem.

Logic and Brain Development

Complex reasoning predominantly takes place in the prefrontal cortex and areas of the brain devoted to language. Language development is, of course, closely linked to explicit learning, as well as to implicit stimulation.

But reasoning requires more than just language skills. The prefrontal cortex carries out what are known as executive functions. It controls concentration, planning, decision-making, and many other functions. These allow us to break down complex tasks into a series of simpler tasks. Reasoning requires a strategy that breaks things down. The prefrontal lobe is a cerebral zone that only matures neurologically after the age of 20.

Logic is neither natural nor easy. Its development requires a comfortable handling of language and the capacity for problem-solving in the prefrontal cortex. Where are we now? Where do we want to go? How can we get there?

Metacognition

2. everyday reasoning, although their logical reasoning skills are undeveloped, young children can argue and express opinions. parents should encourage them. even though a child’s argument will tend to be based on emotion, the practice can help build a critical perspective and confidence..

Despite the fact that young children may not be able to grasp logical concepts, they still employ everyday forms of reasoning in both their use of language and in problem-solving and decision-making. It is from out of these capacities that critical thinking can begin to develop at this age.

As is readily apparent, communication via language is not logical. Natural language does not conform to a formal logical structure. It is contextual, whether we are talking about comprehension or expression. If someone says: “If I had a knife, I would cut my steak,” most people would understand that having a knife makes it possible to cut the steak. However, in formal logic, the sentence means that if I had a knife, I would be obliged to cut the steak. Logical language is systematic and obligatory. But a child learns to speak and to understand in a pragmatic and contextual, not logical, fashion.

Certain communication problems result from an overly rigid logical rigor, as in the case of people with Asperger’s syndrome, a type of high-functioning autism. Paradoxically, human communication only works because it is not a purely logical linguistic system. This is one of the reasons why automated translation between languages has been a thorn in the side of artificial intelligence experts since the 1970s.

Logical Proof and Factual Proof

Most real-life problems that we have been grappling with since infancy cannot be formally resolved by logical deduction .

Decision-making is based on a complex mix of different elements:

the cognitive processing of a situation and/or argument

intervention, conscious or unconscious, from our memory of similar past experiences, our preferences, and our personality in the broad sense

our emotions

This is how a child can choose between two toys or how an adult chooses between buying and renting an apartment. People with ultra-logical cognitive tendencies won’t have enough factors for their reasoning to work with, and may be incapable of making a decision—and therefore, incapable of taking action. Neurological studies, since those undertaken by Antonio Damasio in the 1990s, have shown us that decision-making processes and emotional processes are intimately linked , from both neurophysiological and behavioral perspectives.

Pure logic, besides often producing unfortunate results in the real world, can be a hindrance in a highly complicated universe where decisions require managing multiple factors. This is the main reason why artificial intelligence is only now starting to see results, despite the fact that information technology has been in use since the 1940s.

Computer engineers have needed to overcome their grounding in logical, mathematical, and hypothetical deduction, and to incorporate developments in cognitive science and neurology. Algorithms now operate more like children. That is to say, they make random decisions, analyze and memorize the outcomes in order to progress, and then correct themselves by discerning both the invariables and the contextual variables. This is called deep learning.

Children cannot rely too heavily on logic, but they are still able to express opinions based on their experiences, intuitions, and emotions.

This is also how children between five and nine years old operate. They solve many problems and make many choices, without being able to demonstrate (in the purest sense of the word) why their conclusions and choices were correct.

Between the ages of five and nine, therefore, children cannot rely too heavily on logic. However, they are still able to to express opinions based on their experiences, intuitions, and emotions. To do this, they need to practice, have good self-esteem, and feel esteemed by others in order to believe they have the right, the desire, and the energy to put their critical thinking to use. In other words, they need to exist as a thinking and acting subject whose capacities are recognized by others.

At this age, children are able to argue based on things they have experienced and knowledge they have acquired at school or at home, from books, television, or the internet, or by talking with their friends. They are also able to argue with their “heart.” They assume that their emotions are arguments themselves.

For example, a child might consider that we shouldn’t eat meat because innocent animals shouldn’t have to die. The child’s empathy is the crux of their argument and the strength of their insistence will often be proportional to that of their emotions.

Case in Point

We show children from this age group a drawing of a rectangular flask tipped at an angle, and we ask them: “If I fill this flask roughly halfway, could you draw the water line on the flask?”

What would be the result? Most children will draw a line perpendicular to the flask’s longitudinal axis. Yet, since this axis does not run vertically but is at an angle, the line the child draws is not horizontal relative to the ground, as it should be.

Children err here because their minds are referentially anchored to the flask, just as astronomers for many millennia fixated on the idea of the earth, and later the sun, as a reference point—before realizing that the universe does not have an absolute reference point.

Even if we explain the error to children—and they say they understand—many will, shortly afterwards, make the same mistake again. Their cognitive system is not mature enough to incorporate the logic behind reference and relativity. The example shows how logical thinking is not natural. It requires a learned ability to step back and remove oneself from immediate engagement with a particular situation.

3. Preparing Kids to Think Critically

Parents or guardians can foster critical thinking skills in children from an early age. First, it’s important to understand the basics of how children learn to think and how a child’s mind differs from that of an adult. Critical thinking in their early years prepares children for life’s challenges and allows them to live a productive life.

How to teach critical thinking to your child

Here are four ways you can support your child’s early cognitive development and put them on the path to becoming critical thinkers. Teaching critical thinking may seem daunting, but having a primer on the particular needs of a child can help you better approach this important task.

1. Encourage children not to see everything as centered only on them by involving them in discussions on an array of topics, including current affairs.

Contrary to popular belief, from the age of five—and sometimes even earlier—children like to be involved in discussions, provided they are not drowned in technical vocabulary or formal logic . They also need to feel that adults are interested in what they are saying and that they are being listened to. Adults need to learn to step away from the role of educator and engage children at their level.

It is highly important for the development of critical faculties that children see their thoughts on the world are accepted. By taking those thoughts seriously, we are taking our children seriously and accepting them.

For example, ask five-year-old children whether Santa Claus exists and how they know. Listen to their arguments: they saw Santa at the mall; they know their Christmas presents must come from somewhere. Contradicting them or breaking down their worldview would be a grave mistake. It would fly in the face of our knowledge about cognitive development, and it would disregard their emotional need for this belief. Paradoxically, we need to let children formulate their own ideas and worldviews, namely through dreaming and imagination. In this way, they will grow happy and confident enough, in time and at their own pace, to move on to more mature ideas.

2. Value the content of what children say.

With encouragement, children will want to express their thoughts increasingly often, quite simply because they find it pleasurable. A certain structure in our brains, the amygdala, memorizes emotions linked to situations we experience. We are predisposed to pursue experiences and situations which induce pleasure, be it sensory or psychological. If a child puts energy into reflection in order to convince us that aliens exist, and we then dismantle their arguments and dreams, we will be inhibiting their desire to participate in this type of discussion again.

For children aged five to nine, the pleasure of thinking something through, of expressing and discussing their thoughts, of feeling language to be a source of joy, are all of far greater importance than argumentative rigor or logical reasoning .

Children debate and give their opinions. This stimulates their brain, which creates a whole host of connections, which, in turn, improve their abilities and their cognitive and emotional performance. The pleasure of discussion, of having someone listen to your ideas, releases a “flood” of neurotransmitters that promote cerebral development. An atmosphere of kindness and benevolence in which the child feels heard produces neural connections and develops various kinds of intelligence. As the child learns through debate, putting effort into reflective thought and into verbal and bodily expression, the brain evolves and invests in the future. This results from cognitive stimulation paired with joie de vivre that comes from being heard by others and receiving their undivided attention.

Parents should not hold back from bringing children into discussions and debates.

3. gradually, the ability to argue with pertinence, on both familiar topics of reflection or debate and new ones, will increase..

Numerous recent studies show that doing well in school results more so from pleasure and the development of self-esteem than heavy exposure to graded exercises, which can create anxiety and belittle children. Children are vulnerable and quickly internalize the labels others place on them.

In short, parents should not hold back from bringing children into discussions and debates, keeping to the principles outlined above. Also, be sure to respond to their desire to start discussions within their frame of reference and be sure to take them seriously.

4. Gradually, with time, pleasure, learning, and cognitive and emotional development, it will be possible to encourage children to argue without pressuring them through open-ended questions.

From the age of eight, children can start learning about metacognition and the adoption of alternative points of view. They should also be trained at this time to understand the difference between an opinion, an argument, and a piece of evidence.

An opinion is the expression of an idea that is not, in and of itself, true or false. Children are empowered to express their opinions early on by all the preliminary work on building up self-esteem. “I think they should close down all the schools, so we can be on holiday all the time” is an opinion. A child of five can easily express such an opinion.

An argument is an attempt to convince others by offering information and reasoning. A child of eight might argue: “If we close down all the schools, we can get up later. Then we’ll have more energy to learn things better at home.”

Evidence are the facts we use to try to prove a point in an argument. Evidence can be highly powerful but it rarely amounts to conclusive proof. When an unambiguous proof is presented, alternative opinions evaporate, provided that one can cognitively and emotionally assimilate the perspective of the person presenting the proof. Something can be proven in two ways. On the one hand, it can be proven through formal reasoning—attainable from the age of nine upwards in real-life situations and, later on, in l more abstract situations. On the other hand, it can be established through factual demonstration. If a child claims that “you can scare away a mean dog by running after it,” proof can be given through demonstration. This leaves no need for argument.

From ages eight to nine, children can come to differentiate and prioritize opinion, argument, and evidence in what they say and hear, provided that their own flawed arguments at age five to six were met with respect and tolerance. This is vital for developing children’s self-esteem and respect for others. It enables them to take pleasure in argument and increases their desire to express themselves more persuasively.

Critical thinking exercises for kids

Hunting—for or against? For a debate like this one, with considerable social implications, focus on these concepts:

1. Teach children to distinguish between:

An opinion : I am against hunting…

An argument : … because it entails animal suffering and human deaths.

Hunting significantly increases the production of stress hormones (such as hydrocortisone) in hunted animals.

There are around thousands of hunting accidents each year.

2. Teach children to adopt a counter-argument for practice:

An opinion : I am in favor of hunting…

An argument : … because it allows us to control the size of animal populations.

Evidence : Wild boar populations are high and cause a great deal of damage to farmland.

New Perspectives and Overcoming Biases

4. the importance of self-esteem, children need self-esteem to think themselves worthy of expressing their opinions. parents can strengthen their children’s self-esteem by encouraging them to try new things, stimulating their curiosity, and showing pride in their accomplishments., understanding the importance of self-esteem, the foundation of critical thinking.

Before children can learn to analyze and criticize complicated material or controversial opinions, they need to have a strong sense of themselves. Their capacity to question external sources of information depends on feelings of self-worth and security.

The terms “self-confidence” and “self-esteem” are often used interchangeably. There is, however, a difference between the two, even if they are related. Before we can have high self-esteem, we must first have self-confidence. The feeling of confidence is a result of a belief in our ability to succeed.

Self-esteem rests on our conscious self-worth, despite our foibles and failures. It’s knowing how to recognize our strengths and our limitations and, therefore, having a realistic outlook on ourselves.

Self-esteem requires an ability to recognize our strengths and weaknesses, and to accept them as they are.

For example, children can have high self-esteem even if they know that they struggle with math. Self-esteem can also vary depending on context. Children in school can have high social self-esteem, but a lower academic self-esteem.

Self-esteem requires an ability to recognize our strengths and weaknesses, and to accept them as they are. Children must learn to understand that they have value, even if they can’t do everything perfectly.

Self-esteem starts developing in childhood. Very young children adopt a style of behavior that reflects their self-image. From the age of five, healthy self-esteem is particularly important when it comes to dealing with the numerous challenges they face. Children must, among other things, gradually become more independent, and learn how to read, write, and do mental arithmetic. This period is key, and children need self-confidence as well. More than anywhere else, it is in the family home that children develop the foundations for self-esteem.

Children with high self-esteem:

have an accurate conception of who they are and neither over- nor underestimate their abilities;

make choices;

express their needs, feelings, ideas, and preferences;

are optimistic about the future;

dare to take risks and accept mistakes;

keep up their motivation to learn and to progress;

maintain healthy relationships with others;

trust their own thoughts and trust others.

As parents, developing our own self-esteem enhances the development of our children’s self-esteem, as their identity is closely entwined with our own. Our children learn a great deal by imitating us. Modeling self-esteem can therefore be a great help to them. Here are some examples of what we can do:

Be openly proud of our accomplishments, even those which seem minor to us.

Engage in activities just for fun (and not for competitive reasons).

Don’t pay too much heed to other people’s opinions about us.

Don’t belittle ourselves: if we’ve made an error or if we aren’t so good at a certain task, explain to children that we are going to start again and learn to do it better.

At mealtimes, prompt everyone around the table to say something they did well that day.

On a big sheet of paper, write down the names of family members; then, write down next to everyone’s name some of their strengths.

5. Promoting Self-Esteem

To promote healthy self-esteem in children, parents must strike a balance between discipline and encouragement., the most important thing of all in the development of young children’s self-esteem is our unconditional love for them..

Children must feel and understand that our love will never be dependent on their actions, their successes, or their failures. It is this state of mind that allows them to embrace the unknown and to continue to progress despite the inevitable failures that come along with learning new skills.

Developing Self-Esteem

But be careful not to let unconditional love prevent the imposition of authority or limits. Instead of developing their self-esteem, the absence of limits promotes the feeling in children that they can do no wrong and renders them incapable of dealing with frustration. It is necessary to establish limits and to be firm (without being judgmental). The desired result is only reached if effort and respect are taken seriously.

Self-esteem means loving ourselves for who we are, for our strengths and our weaknesses, and it is based on having been loved this way since birth.

Advice: How to promote the development of a child’s self-esteem

As parents, we have a big influence on our children, particularly when they are young. Here are some ways to help build up children’s self-esteem:

Praise children’s efforts and successes. Note that effort is always more important than results.

Don’t hesitate to reiterate to children that error and failure are not the same thing. Show them that you’re proud of them, even when they make mistakes. Reflect with them on how to do better next time.

Let children complete household chores; give them a few responsibilities they can handle. They will feel useful and proud.

Show children that we love them for who they are, unconditionally, and not for what they do or how they look.

Let children express their emotions and inner thoughts.

Assist children in finding out who they are. Help them to recognize what they like and where their strengths lie.

Encourage them to make decisions. For example, let them choose their own outfits.

Invite them to address common challenges (according to their abilities and age).

Pitfalls to avoid

Avoid being overprotective. Not only does this prevent children from learning, it also sends them a negative message: that they are incapable and unworthy of trust.

Don’t criticize them incessantly. If we’re always making negative comments about our children, and if we show ourselves to be unsatisfied with their work or behavior even when they’re doing their best, they will get disheartened.

If children don’t act appropriately, stress that it is their behavior, rather than their personality, that must change. For example, it is better to explain that an action they may have done is mean, rather than that they are themselves mean.

Always be respectful towards children. Never belittle them. What we say to our children has a great impact on their self-image.

Show them we’re interested in what they’re doing. Don’t ignore them. We are still at the center of their universe.

Don’t compare them to their siblings or to other children their age. (“Your four-year-old sister can do it!”) Highlight how they are progressing without comparing them to anyone else.

Risk-Taking

6. the role of emotions, emotions are an important part of children’s cognitive development, but if emotions become overwhelming they can be counterproductive. parents should help their children learn how to express their feelings calmly and prevent emotions from becoming a distraction., understanding the role of emotions in the development of critical thinking.

Young children may develop skills in language and argument, and benefit from a level of self-esteem allowing them to stand their ground and explore the unknown. Nonetheless, the development of their critical faculties will still be limited if they haven’t learned how to manage their emotions.

Emotions appear in a part of the brain called the limbic system , which is very old in terms of human evolution. This system develops automatically at a very early stage. But very quickly, children experience the need to rein in the spontaneous and unrestricted expression of their emotions. These emotions are, of course, closely connected to basic relations to others (and initially most often to one’s parents) and to cultural norms.

The prefrontal lobe contains the greatest number of neural networks that simultaneously regulate the scope of conscious emotions and their expression in verbal and non-verbal language, as well as in behavior. From the age of five or six, children start their first year of primary school, where they are forced to sit for hours on end each day. They must also listen to a curriculum designed more around societal needs and expectations, rather than around the desires and emotions of children. Frontal lobe development enables the inhibition of urges and the management of emotions , two prerequisites for intellectual learning and for feelings of belonging in family and society.

The ability to manage emotions has a two-fold constructive impact on the development of children’s critical faculties. First, it enables children to override their emotions, so they may focus their attention and concentrate. This is essential for both cognitive development in general and their argumentative, logical, and critical skills.

Management of emotions also allows us to feel settled and to convince and influence others when we speak. Paradoxically, children learn that, by managing their emotions (which is initially experienced as repression), they can have an impact on their peers, make themselves understood, and even be emulated. The pleasure they derive from this reinforces the balance between spontaneity and control, and both pleasure in self-expression and respect for others will increase. Self-esteem will therefore progress, also allowing the child to assert his or her will.

Development of the critical faculties will benefit from a heightened level of self-esteem. But it’s important to remember that this is a balancing act.

If family or social pressures excessively inhibit emotional expression, feelings of uniqueness and self-worth are compromised. In this case, even with otherwise normal (and even excellent) cognitive development, children’s critical faculties can be impeded. A child won’t truly become an individual and the development of his or her critical faculties will therefore be stunted. Such a child is like a mere cell, rather than a whole organ. This lack of individuality is found in the social conventions and education systems established by totalitarian regimes. Highly intelligent, cultured, logical people can, under such regimes, remain devoid of critical thinking skills.

Emotion is the psychological motor of cognition. But in high and uncontrolled doses, emotion can override cognition.

Conversely, if children’s emotions and expressions of emotion are badly managed or not curtailed at all, they will come to see themselves as almost omnipotent. The consequent behavior will be mistaken for high self-esteem . In reality, cognitive and intellectual development will be dampened due to a lower attention span caused by poor emotional management. Logical and argumentative skills will be less developed and what may appear to be “critical” thinking will, in fact, be nothing more than a systematic, unthinking opposition to everything.

Critical thinking without cognitive and intellectual development does not truly exist. Real, constructive critical thinking requires listening, attention, concentration, and the organization of one’s thoughts. The development of these faculties itself requires good emotional management, which must intensify from around the age of five or six, in order to strengthen learning skills and social life. Above all, parents should not try to snuff out a child’s emotions. Emotions are what give children vital energy, the desire to learn, and the strength to exercise self-control. Emotion is the psychological motor of cognition. But in high and uncontrolled doses, emotion can override cognition.

7. Managing Emotions

Parents should not ignore or simply silence their children when they act out or are overcome with emotion. they should work with them on strategies for coping and discuss how they can more calmly and productively express their emotions., how to help our children to control their emotions.

Our emotions are a part of who we are: we have to learn to manage and accept them. In order to help children manage their emotions, we must set limits (for example, by forbidding them to waste food or lie). However, setting limits on their behavior does not mean setting limits on their feelings.

We cannot stop children from getting angry even if they are forbidden from acting on that anger rather we can coach children in controlling their reactions. Sending them to their rooms to calm down will not prevent them from being upset and frustrated. On the contrary, by conveying to them the idea that they must face their emotions alone, we encourage them to repress their feelings. When children repress their emotions, they can no longer manage them consciously, which means they are liable to resurface at any moment.

An angry child is not a bad person, but a hurt person. When children lose control over their emotions, it is because they are overwhelmed.

These outbursts, when our children seem to have totally lost control of themselves, can frighten us as parents. Indeed, if children habitually repress their emotions, they become unable to express them verbally and rage takes over.

Failing to acknowledge children’s emotions can prevent them from learning to exercise self-control.

Advice: How do children learn to manage their emotions?

Children learn from us. When we yell, they learn to yell. When we speak respectfully, they learn to speak respectfully. Likewise, every time we manage to control our emotions in front of our children, they learn how to regulate their own emotions.

To help children manage their emotions, we should explicitly explain how to do so and discuss it with them.

Even older children need to feel a connection with their parents to manage their emotions. When we notice our children having difficulties controlling their emotions, it is important to reconnect with them. When children feel cared for and important, they become more cooperative and their feelings of joy cancel out bad behavioral traits.

The best way to help children become autonomous is to trust them and to entrust them with tasks and little challenges.

An angry child is not a bad person, but a hurt person. When children lose control over their emotions, it is because they are overwhelmed. Controlling their emotions is beyond their capacities at that particular moment in time and emotional control is something that they’ll build gradually as they mature.

If we continue treating them with compassion, our children will feel safe enough to express their emotions. If we help them to cry and let out their emotions, these feelings of being overwhelmed will go away, along with their anger and aggression.

Is it important to teach children specific language for expressing emotions?

Of course it is! But don’t try to force children to voice their emotions. Instead, focus on accepting their emotions. This will teach them that:

There is nothing wrong with emotions—they enrich human life.

Even if we can’t control everything in life, we can still choose how we react and respond.

When we are comfortable with our emotions, we feel them deeply, and then they pass. This gives us the sensation of letting go and of releasing tension.

If we actively teach these lessons—and continue to work on resolving our own emotions—we will be happy to find that our children will learn to manage their feelings. It will eventually become second nature to them.

Emotional Management

8. critical thinking and social life, critical thinking is a positive social norm, but it requires the support of background knowledge and genuine reasoning skills. without them, critical thinking can become an illusion..

Parents should balance their encouragement of children’s argumentative skills and self-expression with an emphasis on intellectual rigor.

Taking account of social norms and peer groups

No child grows up in a vacuum. As they develop, children internalize many of the norms and ways of thinking that are dominant in their families, social lives, schools, and society more broadly. Parents should be aware of the positive and negative influences these different spheres can have on their children. They should know what they can do to expose their children to norms that will foster healthy and independent thinking.

It seems that the right, even the responsibility, to think for oneself and to exercise one’s critical faculties has become increasingly tied to notions of dignity and individuality. More and more we see factors that have historically determined who has the “right” to be critical—age, origin, gender, level of general knowledge, or other implicit hierarchies—fade in importance.

Thus, it is becoming more and more common for students (with disconcerting self-assurance) to correct their teachers on aspects of history or other issues that are matters of fact. This raises some important questions, notably regarding the role of the educator, the goals of education, and the relationships between generations.

Our society encourages critical thinking from a very early age. We have insisted on the fact that, for young children, although intellectual rigor is difficult to attain, it is crucial to develop self-esteem and self-affirmation. But we have also seen that from around the age of eight, it is necessary to move towards teaching them basic reasoning skills.

The risk of making the “right to critical thinking” a social norm from a young age is that we lower intellectual standards. If the encouragement of children to think critically is not paired with intellectual progress in other areas, critical thinking is rendered a mere simulation of free thought and expression. This is as true for children as it is for teenagers or adults.

The entire population may feel truly free and have high self-esteem. However, if the intellectual rigor that comes with arguing, debating, and reasoning, is missing from children’s intellectual and social education, the people will be easily manipulated. Giving our children the freedom to exercise their critical faculties must be paired with the demand for intellectual rigor and linguistic mastery, without which “critical thinking” would offer the mere illusion of liberty.

Striking a balance:

For parents today, it is a matter of striking a balance between fostering critical thought from an early age, in spite of gaps in knowledge and logic, and developing our children’s cognitive faculties and knowledge base. Without these faculties of listening, attention, comprehension, expression, argument, and deduction, critical thinking is an illusion, a pseudo-democratic farce. This can lead to a society plagued by ignorance and vulnerable to barbarism.

On the other hand, we cannot simply slip back into old social conventions whereby children were told to simply keep quiet and learn their lessons passively. The only thing this approach ensures is that the child won’t become a troublemaker.

What is needed is an approach that harmonize advances in philosophy and psychology, which consider children as fully fledged individuals, on the one hand, with an understanding of the intellectual immaturity of this child, on the other.

Disagreeing in a civilized manner, in the end, allows us to agree on what matters most.

With the help of an affectionate, attentive, but also sometimes restrictive and guiding parent—who is at once intellectually stimulating, indulgent, and patient with the child’s needs—early development of self-affirmation and critical thinking becomes compatible with growing intellectual aptitude.

This intellectual aptitude is crucial to a healthy social life as well. People lacking this intellectual maturity cannot even disagree with each other productively; they lack the ability to discuss subjects worthy of critical interest, as well as the social and cognitive skills of listening, argument, and logical deduction. Disagreeing in a civilized manner, in the end, allows us to agree on what matters most.

Consider this discussion between two eight year olds.

– “I saw a show on TV yesterday that proved that aliens really exist. Tons of people have seen them, and they’ve found marks left by flying saucers in the desert!”

– “But there’s no real evidence. Those clues and eyewitness accounts weren’t very specific. Different witnesses described the aliens in very different ways—some said they were little green men, while others said they were big with glowing eyes. And the marks from UFOs could have been formed by strong winds.”

– “Oh, so you think you’re smarter than the scientists on TV, is that it?”

One child declares that a TV show they saw proves the existence of aliens. He or she takes it for granted that what we see on TV is true. The second is educated into a norm that calls claims into question and demands evidence. The first child doesn’t understand the second, because, to him or her, seeing it on TV is proof enough. From this point onward, the discussion can only go in circles. In this case, different social or family norms are incompatible.

Independent Thinking

Case study 1, metacognition.

Already at a young age children can begin to gain perspective on how they reason. One good way to help them foster this metacognition is by pointing out the variety of different methods available for solving a particular problem. By, for example, seeing the multiple different methods available for solving a math problem, children can begin to think about their own thought processes and evaluate various cognitive strategies. This will gradually open up the world of reasoning to them. They will begin to pay more attention to how they solve problems or complete tasks involving reasoning, instead of focusing only on answering correctly or completing the task.

How do children calculate 6 x 3, for example?

There are several ways:

They could add 6 + 6 + 6;

They could recall that 6 x 2 = 12, then add six more to get 18;

They could simply memorize and recall the answer: 18;

They could draw a grid of 6 by 3 units and then count how many boxes are in the grid.

Or they could use one of various other techniques…

Our culture values accurate and precise results but tends to pay little attention to the route taken to arrive at those results. Yet, if children are aware of their train of thought, they will be in a better position to master the technique—to perfect it to the point where they may even decide to switch to another technique if they need to increase their speed, for example. That is why it is important to help children understand the method they are using to the point that they can explain it themselves.

In helping their children with schoolwork or other projects involving reasoning, parents should ask them to explain themselves, make explicit the steps they’re taking to solve a particular problem, and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of their method and alternative methods. The result will be a much deeper understanding not only of the particular task at hand, but also of the practice of reasoning itself.

Case Study 2

Logical proof and factual proof.

At this stage, we can begin to introduce rudimentary logical concepts and distinctions. In everyday conversation, children have already begun using what we might call “natural logic.” They may, for example, get in arguments, like the one below, in which they draw conclusions based on premises. When children present these types of arguments, parents can intervene to teach basic logical concepts and ask children how a given conclusion might be proven or disproven.

One distinction appropriate to teach at this age is that between logical proof (proof that draws logical conclusions from certain premises) and factual proof (proof that uses actual facts to prove or disprove a given statement). The following anecdote provides the opportunity for such a lesson.

William and Eve, two children walking their dog in the park, are having a conversation about Labradors:

— “There are two kinds of Labradors—black and golden,” declares William.

— “That’s not true; there are also chocolate Labradors,” replies Eve. “My friend Adam has one.”

— “Well, his dog must not be a Labrador then,” William says.

How might we interpret this conversation?

In terms of logical proof, if Labradors are either black or golden, Adam’s chocolate “Labrador” cannot be a Labrador. That is a logically formulated proof. The reasoning is valid. It is the basic premise, William’s initial declaration that there are only two kinds of Labradors, that is false. It is, therefore, possible for William to draw a false conclusion even though his logic is technically correct.

In terms of factual proof, if we can prove that the chocolate-colored dog has two Labrador parents, we can factually prove that William’s premise is wrong: there are at least three types of Labrador.

There are many opportunities like this one to begin to make explicit the logical steps involved in everyday conversations with your children and to show them that they are already using logic, even if they may not know it. This serves to get them thinking about their own thinking, and it makes the topics of logic and reasoning less intimidating.

Case Study 3

What is bias.

A bias is a simply a preconceived and unreasoned opinion. Often biases are formed due to upbringing, larger societal biases, or particular subjective experiences. They exist in many forms and can persist into adulthood unless a child builds a firm foundation in critical thinking and reasoning.

How to overcome bias

The following anecdotes demonstrate how parents can use everyday events to help their children better understand and relate to perspectives outside their own. In order to think critically, children must be able to imaginatively and empathetically put themselves outside their own experiences and perspectives. Children thereby begin to come to terms with the limitations their own upbringings and backgrounds necessarily impose on them.

This is a vital part of metacognition since it allows children to see themselves, their attitudes, and their views as if from the outside. They become better at overcoming biases, prejudices, and errors in thinking. This process also enables them to entertain the perspectives of others and thereby engage in argument and debate in the future with more charity and nuance. Finally, it encourages them to seek out new experiences and perspectives and to develop intellectual curiosity.

In this first anecdote, a child learns to broaden her horizons through an interaction with another child whose experience is different from her own. In the second, a child learns that his attitude toward particular objects can depend strongly on the context in which they are experienced.

Overcoming Bias Example 1: Fear of Dogs

Jane is eight years old and lives in a small village. Her parents own several animals, including two Labradors.

Jane’s cousin Max is nine and a half and lives in central Paris.

Max is always happy to visit Jane, and they play together outside, dreaming up adventures and climbing trees. But he is terribly afraid of Jane’s big dogs; whenever they come near him, he screams at the top of his lungs and runs indoors to hide. Jane finds this funny, calling her cousin a “fraidy cat” and devising ploys to lure Max close to the dogs.

Jane does not realize that, unlike her, Max is not used to having animals in his daily environment. She interprets his attitude exclusively from the viewpoint of her own experience.

What would you do if you were Jane’s parents?

At the dinner table, Jane’s mom asks her to stop teasing Max and explains that he is not used to animals because he lives in different circumstances than she does.

She asks Max to tell them what it is like living in the city. Max talks about his daily life and, notably, how he takes the metro by himself to school in the mornings, two stations from home.

The blood drains from Jane’s face: “You take the metro all by yourself? I could never do that, I’d be much too scared of getting lost.”

Her mom says to her: “You see, Jane, you fell into a trap—thinking that your cousin was just like you. We are all different. You need to remind yourself of that in the future because it’s easy for you to forget!”

This focused discussion has given Jane the opportunity to overcome her own egocentrism by realizing that she and Max inhabit different worlds. She, therefore, realizes that even though Max is scared of dogs (whereas she is not), he is capable of things that intimidate her, like taking the metro alone. This allows her to re-examine her way of reasoning through a “meta” example of her own ideas about the world, eventually leading her to change her attitude toward her cousin.

As parents, we should look for and take advantage of opportunities to open up our children to new perspectives, especially with respect to unexamined biases they may have against peers or outsiders. They will gradually learn to identify and guard against the tendency we all have to generalize recklessly from our own limited experience. Moreover, they will develop the capacity to see things from other perspectives and interests outside their own narrow sphere.

Overcoming Bias Example 2: Fear of Nettles

Josh has recently been on a field trip with his class. Before a hike, the teacher warns the students to steer clear of the nettle plants in the area These “stinging nettles” can cause a nasty itching and burning rash.

A few days later, at dinner, Josh finds that his parents have prepared a nettle soup . Boiling water makes the nettles safe to touch and eat. But he refuses to eat it, since his experience tells them to keep nettles as far away from his body as possible— especially his mouth.

Josh vehemently refuses to try the soup at first and insists on having a frozen pizza instead. But his parents are firm with him and show him that the soup poses no danger by eating it themselves. Finally, Josh relents and tries the soup. He finds that it causes him no harm, and, much to his surprise, he actually enjoys it.

Children who do not know that nettles are safe to eat formulate their prejudice against the soup based solely on their experience, which is limited to the nettle’s irritant qualities. These kinds of learning experiences can be good moments for parents to point out to their children how they may falsely generalize their own limited experiences and how those experiences can produce unwarranted biases. These prejudices may stop them from trying out new things that may very well enrich their lives.

Case Study 4

Developing self esteem.

Climbing Esther and Ali, both five years old, are at a playground, looking at a climbing wall designed for five to 10 year olds.

Esther goes over to the wall, looks at it, and touches the climbing holds. She starts climbing, pulling herself up with her arms and putting her feet on the lower holds to relieve her arms.