Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

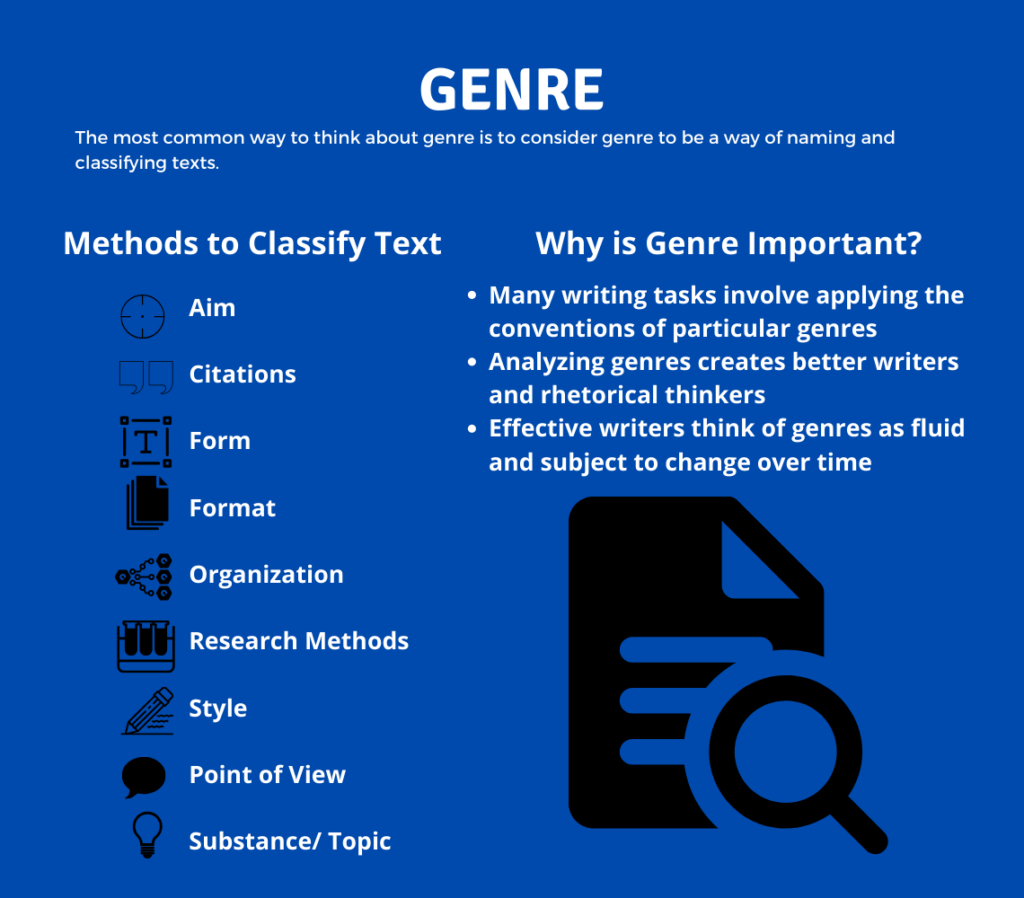

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions about what constitutes a knowledge claim or authoritative research method; the discourse conventions of a particular discourse community . This article reviews research and theory on 6 different definitions of genre, explains how to engage in genre analysis, and explores when during the writing process authors should consider genre conventions. Develop your genre knowledge so you can discern which genres are appropriate to use—and when you need to remix genres to ensure your communications are both clear and persuasive.

Genre Definition

G enre may refer to

- by the aim of discourse

- by discourse conventions

- by discourse communities

- by a type of technology

- a social construct

- the situated actions of writers and readers

- the situated practices and epistemological assumptions of discourse communities

- a form of literacy .

Related Concepts: Deductive Order, Deductive Reasoning, Deductive Writing ; Interpretation ; Literacy ; Mode of Discourse ; Organizational Schema; Rhetorical Analysis ; Rhetorical Reasoning ; Voice ; Tone ; Persona

Genre Knowledge – What You Need to Know about Genre

Genre plays a foundational role in meaning-making activities, including interpretation , reading , writing, and speaking.

In order to communicate with clarity , writers and speakers need to understand the expectations of their audiences regarding the appropriate content, style, design, citation style, and medium. Genres facilitate communication between writers and readers, authors and audiences, and writers/speakers and readers/listeners. Genre and genre knowledge increase the likelihood of clarity in communications .

Writers use their knowledge of genre to jumpstart composing: a genre presumes a formula for how to organize a document, how to develop and present a research question , how to substantiate claims–and more. For writers, genres are an efficient way to respond to recurring situations . Rather than reinvent the wheel every time, writers save time by considering how others have responded in the same or a similar situation . Genres are like big Lego chunks that can be re-used to start a new Lego creation that is similar to past Lego creations you’ve created.

In turn, readers use genres to more quickly scan information . Because they know the formula, because they share with the author as members of a discourse community a common language, common topoi , archive , canonical texts , and expectations about what to say and how to say it in, they can skip through a document and grab the highlights.

Six Definitions of Genre

1. genre refers to a naming and categorization scheme for sorting types of writing.

“… [L]et me define “genres” as types of writing produced every day in our culture, types of writing that make possible certain kinds of learning and social interaction.” (Cooper 1999, p. 25)

G enre refers to types of writing, art, and musical compositions. For instance

- alphabetical texts may be categorized as Expository Writing, Descriptive Writing, Persuasive Writing, or Narrative Writing .

- movies may be categorized as Action & Adventure, Children & Family Movies, Comedies, Documentaries, Dramas.

- music may be categorized as Artist, Album, Country, New Age, Jazz, and so on.

There are many different ways to define and sort genres. For instance, genres may defined based on their content, organization, and style. Or, genres may be defined and categorized based on

- Examples: Drama, Fable, Fairy Tale, etc.

- Move 1 Establish a territory

- Move 2 Establish a niche

- Move 3 Occupy the niche (Swales and Feak 2004)

- A research article written for a scientific audience most likely uses some for of an “IMRAC structure”–i.e., an introduction, methods, results, and conclusion

- An article in the sciences and social sciences would use APA style for citations

- by the type of technology used by the sender and the receiver of the information.

2. Genre is a Social Construct

“Genres are conventions, and that means they are social – socially defined and socially learned.” (Bomer 1995:112) “… [A] genre is a socially standard strategy, embodied in a typical form of discourse, that has evolved for responding to a recurring type of rhetorical situation.” (Coe and Freedman 1998, p. 137)

Genre is more than a way to sort types of texts by discourse aim or some other classification scheme: Genres are social, cultural, rhetorical constructs. For example,

- writers draw on their expectations about what they believe their readers will know about a genre–how it’s structured ( what it’s formula is! ) and when it’s socially useful.

- readers draw on their past experiences as readers and as members of particular discourse communities. They hold expectations about the appropriate use of particular textual patterns in specific situations.

Or, consider this example: in the social situation of seeking a job, an applicant knows from the archive , the culture, the conversations about job seeking , that they are expected to create a letter of application and a résumé . More than that, they know the point of view they are to take as well as the tone –and more.

Writers and readers develop textual expectations tacitly — by reading and speaking with others — and formally: by studying genres in school. Students are inculcated in textual practices of particular disciplines (e.g., engineering or biology) as part of their academic and professional training.

3. Genres Reflect the Situated Actions of Writers and Readers

“a rhetorically sound definition of genre must be centered not on the substance or the form of discourse but on the action it is used to accomplish” (Miller 1984, p. 151)

Carolyn Miller (1984) extends this social view of genre in her article Genre as Social Action by operationalizing genre from a rhetorical perspective. Miller asserts genres are the embodiment of situated actions. In her rhetorical model of genre, Miller theorizes

- writers enter a rhetorical situation guided by aims (e.g., to persuade users to support a proposal ). The writer assesses the rhetorical situation (e.g., considers audience , purpose , voice , style ) to more fully understand the situation and the motives of stakeholders.

- For instance, a researcher could dip into a research study seeking empirical support for a claim . A graphic designer could open a magazine looking for layout ideas.

4. Genres Embody the Situated Practices and Values of Discourse Communities

“Genre not only allows the scholar to report her research, but its conventions and constraints also give structure to the actual investigations she is reporting” (Joliffe 1996, p. 283).

The textual practices of discourse communities reflect the epistemological assumptions of practitioners regarding what constitutes an appropriate rhetorical stance , research method , or knowledge claim . For instance, a scientist doesn’t insert their subjective opinions into the methods section of a lab report because they understand their audience expect them to follow empirical methods and an academic writing prose style

Academic documents, business documents, legal briefs, medical records—these sorts of texts are grounded in the situated practices of members of particular discourse communities . Practitioners — e.g., scientists in a research lab, accountants in an accountancy firm, or engineers in an engineering firm— share assumptions, conventions, and values about how documents should be researched, written, and shared. Discourse communities develop unique ways of communicating with one another. Their daily work, their situated practices, reflect their assumptions about what constitutes knowledge , appropriate research methods, or authoritative sources . Genres reflect the values of communities . They provide a roadmap to rhetors for how to engage with community members in expected ways. (For more on this, see Research ).

5. Genre Knowledge Constitutes a Form of Literacy

Genres are created in the forge of recurring rhetorical situations . Particular exigencies call for particular genres . Applying for a job? Well, then, a résumé and cover letter are called for. Trying to report on an experiment in organic chemistry? Well, then a lab report is due. Thus, being able to recognize which genre is called for by a particular exigency, a particular call to write , is a form of literacy : If you’re unfamiliar with a genre and your reader’s expectations for that genre, then you may as well be from mars.

Genre Analysis – How to Engage in Genre Analysis

When we enter a rhetorical situation , guided by a sense of purpose like an explorer clutching a compass, we invariably compare the present situation to past situations. We reflect on whether we have read the work of other writers who have also addressed the same or somewhat equivalent rhetorical situation , the topic, we’re facing. If you have a proposal due, for instance, it helps to look at some samples of past proposals–particularly if you can access proposals funded by the organization from whom you are seeking support.

For genre theorists, these are acts of typification –a moment where we typify a situation: “What recurs is not a material situation (a real, objective, factual event) but our construal of a type” (Miller 157).

In other words, genres are conceptual tools, ways we relate situated actions to recurring rhetorical situations. When first entering a situation, we assess whether this is a recurring rhetorical situation and whether past responses will work equally well for this new situation—or if we’ll need to tweak our response, our text, a bit. For instance, if applying for a job, you might look at previous drafts of job application letters

Genres are like prefabricated Lego pieces that we can use to jumpstart a new Lego masterpiece.

We abbreviate the experiences of our lives by creating idealized versions–i.e., metatexts that capture the gist of those experiences. Or, we access the archive , or our memory of the archive, and seek exemplars — canonical texts , the works of others who addressed similar exigencies , similar rhetorical situations.

To make this less abstract, let’s consider what might go through the mind of a writer who wants to write a New Year’s party invitation. If the writer were an American, they might reflect on the ritual ball drop in Times Square in New York City. They might recall past texts associated with New Year’s celebrations (party invitations, menus, greeting cards, party hats, songs, and resolutions) as well as rituals (fireworks, champagne, or a New Year’s kiss). They might even conduct an internet search for New Year’s Eve party invitations or download a party template from Google Docs or Microsoft Word. Over time, that writer’s sense of the ideal New Year’s party invitation becomes typified —a condensation of the texts and rituals and stories.

Because we tend to have unique experiences and because we have different personalities, motives, and aims , our sense of an ideal New Year’s Eve invitation might be somewhat different from those of our friends and family—or even the broader society. Rather than assuming it’s a good time to go out and party and dance, you may think it’s a good time to stay home and meditate. After all, as writers, we experience events, texts and rituals subjectively and uniquely. Thus, we don’t all have the same ideas about what should happen at a New Year’s party or even what the best party invite should look like. Still, when we sit down to write a party invitation for New Year’s Eve, this is a reoccurring situation for us, and we cannot help but be influenced by all of the past invitations we’ve received, what our friends and loved ones have recommended, and what we see online for party invite templates (if we engage in strategic searching).

Sample Genre Analysis

Below are some sample questions and perspectives you may consider when engaging in Genre Analysis.

1. When During Composing Should I Engage in Genre Analysis?

Early in the writing process — during prewriting — you are wise to identify the genre your audience expects you to follow. Then, engage in strategic searching to identify exemplars and canonical texts that typify the genre.

Next, you might begin your first draft by outlining the sections of discourse associated with the genre you’re writing in. For example, if you are writing an Aristotelian argument for a school paper, you might jumpstart your first draft by listing the rhetorical moves associated with Aristotelian argument as your subject headings:

- Introduce the Topic

- Introduce Claims

- Appeal to Ethos & Persona to Establish an Appropriate Tone

- Appeal to Emotions

- Appeal to Logic

- Present Counterarguments

- Search for a Compromise and Call for a Higher Interest

- Speculate About Implications in Conclusions

That said, it’s important to note that some people prefer not to think about genre at all during drafting. Research in writing studies has found that there is no single, ideal writing process . Instead, our personalities, rhetorical stance , openness to information , rhetorical situation (e.g., contextual factors such as time available and access to information )–and more — influence how we compose.

You may not want to think much about genre when

- You’re the type of writer who needs to write your way to meaning. For you, writing is rewriting

- Your audience may have specific expectations in mind that you haven’t addressed. You may be unfamiliar with how other writers have addressed that situation in the past. You may lack access to the information you need to research how others typically respond to the rhetorical situation you are facing

In summary, thinking about genre and reading the works of other writers addressing similar rhetorical situations will probably help you jumpstart a writing project. However, at the end of the day, only you can decide how to work with genres of discourse.

Coe, R., & Freedman, A. (1998). Genre theory: Australian and North American approaches. In M. L. Kennedy (ed), Theorizing composition: A critical sourcebook of theory and scholarship in contemporary composition studies (p p. 136-147). Greenwood Press.

Joliffe, D. A. (1996). Genre. In T. Enos (ed), Encyclopedia of rhetoric and composition: Communication from ancient times to the information age (pp . 279-284). Garland Publishing.

Miller, R. (1984). Genre as social action. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 70 , 151-167.

Swales, J., & C. Feak (2004). Academic writing for graduate students: Essential tasks and skills . University of Michigan Press

Related Articles:

Annotated bibliography.

Argument - Argumentation

Autobiography, conclusions - how to write compelling conclusions, cover letter, letter of transmittal.

Dialogue - The Difficulty of Speaking

Executive summary, formal reports, infographics, instructions & processes.

Introductions

Presentations, problem definition, progress reports, recommendation reports, research proposal, research protocol.

Reviews and Recommendations

Subjects & concepts, team charter, suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Joseph M. Moxley

Argument is an iterative process that informs humankind’s search for meaning. Learn about different types of argumentation (Aristotelian Argument; Rogerian Argument; Toulmin Argument) so you can identify the best way...

- Jennifer Janechek

- David Kranes

- Angela Eward-Mangione , Katherine McGee

- Joseph M. Moxley , Julie Staggers

Lorem Ipsum has been the industry’s standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

18.3 Glance at Genre: Genre, Audience, Purpose, Organization

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify key genre conventions, including structure, tone, and mechanics.

- Implement common formats and design features for different text types.

- Demonstrate how genre conventions vary and are shaped by purpose, culture, and expectation.

The multimodal genres of writing are based on the idea that modes work in different ways, with different outcomes, to create various vehicles for communication. By layering, or combining, modes, an author can make meaning and communicate through mixed modes what a single mode cannot on its own. Essentially, modes “cooperate” to communicate the author’s intent as they interweave meanings captured by each.

For example, think of a public service announcement about environmental conservation. A composer can create a linguistic text about the dangers of plastic pollution in oceans and support the ideas with knowledge of or expertise in the subject. Yet words alone may not communicate the message forcefully, particularly if the audience consists of people who have never considered the impact of pollution on the oceans. That composer, then, might combine the text with images of massive amounts of human-generated plastic waste littering a shoreline, thus strengthening the argument and enhancing meaning by touching on audience emotions. By using images to convey some of the message, the composer layers modes. The picture alone does not tell the whole story, but when combined with informational text, it enhances the viewer’s understanding of the issue. Modes, therefore, can be combined in various ways to communicate a rhetorical idea effectively.

Audience Awareness

As with any type of composition, knowing your audience (the readers and viewers for whom you are creating) will help you determine what information to include and what genre, mode(s), or media in which to present it. Consider your audience when choosing a composition’s tone (composer’s attitude toward the audience or subject), substance, and language. Considering the audience is critical not only in traditional academic writing but also in nearly any genre or mode you choose. Ask yourself these questions when analyzing your audience’s awareness:

- What (and how much) does the audience already know about the topic? The amount of background information needed can influence what genre, modes, and media types you include and how you use them. You don’t want to bore an audience with information that is common knowledge or overwhelm an audience with information they know nothing about.

- What is the audience’s viewpoint on the subject? Are you creating for a skeptical audience or one that largely agrees with your rhetorical arguments?

- How do you relate to your audience? Do you share cultural understanding, or are you presenting information or beliefs that will be unfamiliar? This information will help you shape the message, tone, and structure of the composition.

Understanding your audience allows you to choose rhetorical devices that reflect ethos (appeals to ethics: credibility), logos (appeals to logic: reason), and pathos (appeals to sympathy: emotion) to create contextually responsive compositions through multiple modes.

It important to address audience diversity in all types of composition, but the unique aspects of multimodal composition present particular opportunities and challenges. First, when you compose, you do so through your own cultural filter, formed from your experiences, gender, education, and other factors. Multimodal composition opens up the ability to develop your cultural filter through various methods. Think about images of your lived experiences, videos capturing cultural events, or even gestures in live performances. Also consider the diversity of your audience members and how that affects the content choices you make during composition. Avoiding ethnocentrism —the assumption that the customs, values, and beliefs of your culture are superior to others—is an important consideration when addressing your audience, as is using bias-free language, especially regarding ethnicity, gender, and abilities.

Blogs, Vlogs, and Creative Compositions

Among the modes available to you as a composer, blogs (regularly updated websites, usually run by an individual or a small group) have emerged as a significant genre in digital literature. The term blog , a combination of web and log , was coined in 1999 and gained rapid popularity in the early 2000s. In general, blogs have a relatively narrow focus on a topic or argument and present a distinctive structure that includes these features:

- A headline or title draws in potential readers. Headlines are meant to grab attention, be short, and accurately reflect the content of the blog post.

- An introduction hooks the reader, briefly introducing the topic and establishing the author’s credibility on the subject.

- Short paragraphs often are broken up by images, videos, or other media to make meaning and supplement or support the text content.

- The narrative is often composed in a style in which the author claims or demonstrates expertise.

- Media such as images, video, and infographics depict information graphically and break up text.

- Hyperlinks (links to other internet locations) to related content often serve as evidence supporting the author’s claim.

- A call to action provides clear and actionable instructions that engage the reader.

Blogs offer accessibility and an opportunity to make meaning in new ways. By integrating images and audiovisual media, you can develop a multimodal representation of arguments and ideas. Blogs also provide an outlet for conveying ideas through both personal and formal narratives and are used frequently in industries from entertainment to scientific research to government organizations.

Newer in the family of multimodal composition is the video blog, or vlog , a blog for which the medium is video. Vlogs usually combine video embedded in a website with supporting text, images, or other modes of communication. Vlogging often takes on a narrative structure, similar to other types of storytelling, with the added element of supplementary audio and video, including digital transitions that connect one idea or scene to another. Vlogs offer ample opportunities to mix modalities.

Vlogs give a literal voice to a composer, who typically narrates or speaks directly to the camera. Like a blogger, a vlog creator acts as an expert, telling a narrative story or using rhetoric to argue a point. Vlogs often strive to create an authentic and informal tone, similar to published blogs, inviting a stream-of-consciousness or interview-like style. Therefore, they often work well when targeted toward audiences for whom a casual mood is valuable and easily understood.

Other creative compositions include websites, digital or print newsletters, podcasts, and a wide variety of other content. Each composition type has its own best practices regarding structure and organization, often depending on the chosen modalities, the way they are used, and the intended audience. Whatever the mode, however, all multimodal writing has several characteristics in common, beginning with effective, intentional composition.

Effective Writing

Experimenting with modes and media is not an excuse for poorly developed writing that lacks focus, organization, thought, purpose, or attention to mechanics. Although multimodal compositions offer flexibility of expression, the content still must be presented in well-crafted, organized, and purposeful ways that reflect the author’s purpose and the audience’s needs.

- To be well-crafted, a composition should reflect the author’s use of literary devices to convey meaning, use of relevant connections, and acknowledgment of grammar and writing conventions.

- To be organized, a composition should reflect the author’s use of effective transitions and a logical structure appropriate to the chosen mode.

- To be purposeful, a composition should show that the author addresses the needs of the audience, uses rhetorical devices that advance the argument, and offers insightful understanding of the topic.

Organization of multimodal compositions refers to the sequence of message elements. You must decide which ideas require attention, how much and in what order, and which modalities create maximum impact on readers. While many types of formal and academic writing follow a prescribed format, or at least the general outline of one, the exciting and sometimes overwhelming features of multimodal possibilities open the door to any number of acceptable formats. Some of these are prescribed, and others more open ended; your job will inevitably be to determine when to follow a template and when to create something new. As the composer, you seek to structure media in ways that will enable the reader, or audience, to derive meaning. Even small changes in media, rhetorical appeal, and organization can alter the ways in which the audience participates in the construction of meaning.

Within a medium—for example, a video—you might include images, audio, and text. By shifting the organization, placement, and interaction among the modes, you change the structure of the video and therefore create varieties of meaning. Now, imagine you use that same structure of images, audio, and text, but change the medium to a slideshow. The impact on the audience will likely change with the change in medium. Consider the infamous opening scene of the horror movie The Shining (1980). The primary medium, video, shows a car driving through a mountainous region. After audio is added, however, the meaning of the multimodal composition changes, creating an emphasis on pace—management of dead air—and tone—attitude toward the subject—that communicates something new to the audience.

Exploring the Genre

These are the key terms and characteristics of multimodal texts.

- Alignment: the way in which elements such as text features, images, and particularly text are placed on a page. Text can be aligned at the left, center, or right. Alignment contributes to organization and how media transitions within a text.

- Audience: readers or viewers of the composition.

- Channel: a medium used to communicate a message. Often-used channels include websites, blogs, social media, print, audio, and video-hosting sites.

- Complementary: describes content that is different across two or more modes, both of which are necessary for understanding. Often audio and visual modes are complementary, with one making the other more meaningful.

- Emphasis: the elements in media that are most significant or pronounced. The emphasis choices have a major impact on the overall meaning of the text.

- Focus: a clear purpose for composition, also called the central idea, main point, or guiding principle. Focus should include the specific audience the composer is trying to influence.

- Layering: combining modes in a single composition.

- Layout: the organization of elements on a page, including text, images, shapes, and overall composition. Layout applies primarily to the visual mode.

- Media: the means and channels of reaching an audience (for example, image, website, song). A medium (singular form of media ) can contain multiple modes.

- Mode: the method of communication (linguistic, visual, audio, or spatial means of creating meaning). Media can incorporate more than one mode.

- Organization: the pattern of arrangement that allows a reader to understand text or images in a composition. Organization may be textual, visual, or spatial.

- Proximity: the relationship between objects in space, specifically how close to or far from one another they are. Proximity can show a relationship between elements and is often important in layout.

- Purpose: an author’s reason for writing a text, including the reasoning that accounts for which modes of presentation to use. Composers of multimodal texts may seek to persuade, inform, or entertain the audience.

- Repetition: a unifying feature, such as a pattern used more than once, in the way in which elements (text features, typeface, color, etc.) are used on a page. Repetition often indicates emphasis or a particular theme. Repetitions and patterns can help focus a composition, explore a theme, and emphasize important points.

- Supplementary: describes content that is different in two or more modes, where a composer uses one mode to convey primary understanding and the other(s) to support or extend understanding. Supplementary content should not be thought of as “extra,” for its purpose is to expand on the primary media.

- Text: written words. In multimodal composition, text can refer to a piece of communication as a whole, incorporating written words, images, sounds, and movement.

- Tone: the composer’s attitude toward the subject and/or the audience.

- Transitions: words, phrases, or audiovisual elements that help readers make connections between ideas in a multimodal text, including connections from sentence to sentence, paragraph to paragraph, and mode to mode. Transitions show relationships between ideas and help effectively organize a composition.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/18-3-glance-at-genre-genre-audience-purpose-organization

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

What is a Genre? Definition, Examples of Genres in Literature

Home » The Writer’s Dictionary » What is a Genre? Definition, Examples of Genres in Literature

Genre definition: Genre is the organization and classification of writing.

What is Genre in Literature?

What does genre mean? Genre is the organization of literature into categories based on the type of writing the piece exemplifies through its content, form, or style.

Example of Literary Genre

The poem “My Papa’s Waltz” by Theodore Roethke fits under the genre of poetry because its written with lines that meter and rhythm and is divided into stanzas.

It does not follow the traditional sentence-paragraph format that is seen in other genres

Types of Literary Genre

There are a few different types of genre in literature. Let’s examine a few of them.

Poetry : Poetry is a major literary genre that can take many forms. Some common characteristics that poetry shares are that it is written in lines that have meter and rhythm. These lines are put together to form stanza in contrast to other writings that utilize sentences that are divided into paragraphs. Poetry often relies heavily on figurative language such as metaphors and similes in order to convey meanings and create images for the reader.

- “Sonnet 18” is a poem by William Shakespeare that falls within this category of literature. It is a structured poem that consists of 14 lines that follow a meter (iambic pentameter) and a rhyme scheme that is consist with Shakespearean Sonnets.

Drama : This literary genre is often also referred to as a play and is performed in front of an audience. Dramas are written through dialogue and include stage directions for the actors to follow.

- The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde would be considered a drama because it is written through dialogue in the form of a script that includes stage directions to aid the actors in the performance of the play.

Prose : Prose is a type of writing that is written through the use of sentences. These sentences are combined to form paragraphs. This type of writing is broad and includes both fiction and non-fiction.

- To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee is an example of fictional prose. It is written in complete sentences and divided through paragraphs.

Fiction : Fiction is a type of prose that is not real. Authors have the freedom to create a story based on characters or events that are products of their imaginations. While fiction can be based on true events, the stories they tell are imaginative in nature.

Like poetry, this genre also uses figurative language; however, it is more structural in nature and more closely follows grammatical conventions. Fiction often follows Freytag’s plot pyramid that includes an exposition, inciting incident, rising action, climax, falling action, resolution, and dénouement.

- The novel Slaughterhouse Five by Kurt Vonnegut is an example of a fictional story about the main character’s experience with his self-acclaimed ability to time travel.

Nonfiction : Nonfiction is another type of prose that is factual rather than imaginative in nature. Because it is more factual and less imaginative, it may use less figurative language. Nonfiction varies however from piece to piece. It may tell a story through a memoir or it could be strictly factual in nature like a history textbook.

- The memoir Night by Elie Wiesel is a memoir telling the story of Wiesel’s experience as a young Jewish boy during the Holocaust.

The Function of Genre

Genre is important in order to be able to organize writings based on their form, content, and style.

For example, this allows readers to discern whether or not the events being written about in a piece are factual or imaginative. Genre also distinguishes the purpose of the piece and the way in which it is to be delivered. In other words, plays are meant to be performed and speeches are meant to be delivered orally whereas novels and memoirs are meant to be read.

Summary: What Are Literary Genres?

Define genre in literature: Genre is the classification and organization of literary works into the following categories: poetry, drama, prose, fiction, and nonfiction. The works are divided based on their form, content, and style. While there are subcategories to each of these genres, these are the main categories in which literature is divided.

Final Example:

The short story “The Cask of Amontillado” by Edgar Allan Poe is a fictional short story that is written in prose. It fits under the prose category because it is written using complete sentences that follow conventional grammar rules that are then formed into paragraphs.

The story is also identified as fictional because it is an imagined story that follows the plot structure.

School of Writing, Literature, and Film

- BA in English

- BA in Creative Writing

- About Film Studies

- Film Faculty

- Minor in Film Studies

- Film Studies at Work

- Minor in English

- Minor in Writing

- Minor in Applied Journalism

- Scientific, Technical, and Professional Communication Certificate

- Academic Advising

- Student Resources

- Scholarships

- MA in English

- MFA in Creative Writing

- Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies (MAIS)

- Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing

- Undergraduate Course Descriptions

- Graduate Course Descriptions

- Faculty & Staff Directory

- Faculty by Fields of Focus

- Promoting Your Research

- 2024 Spring Newsletter

- Commitment to DEI

- Twitter News Feed

- 2022 Spring Newsletter

- OSU - University of Warsaw Faculty Exchange Program

- SWLF Media Channel

- Student Work

- View All Events

- The Stone Award

- Conference for Antiracist Teaching, Language and Assessment

- Continuing Education

- Alumni Notes

- Featured Alumni

- Donor Information

- Support SWLF

What is a Genre? || Definition & Examples

"what is a genre": a literary guide for english students and teachers.

View the full series: The Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms

- Guide to Literary Terms

- BA in English Degree

- BA in Creative Writing Degree

- Oregon State Admissions Info

What is a Genre? Transcript (English and Spanish Subtitles Available in Video, Click Here for Spanish Transcript)

By Ehren Pflugfelder , Oregon State University Associate Professor of Rhetoric

12 February 2020

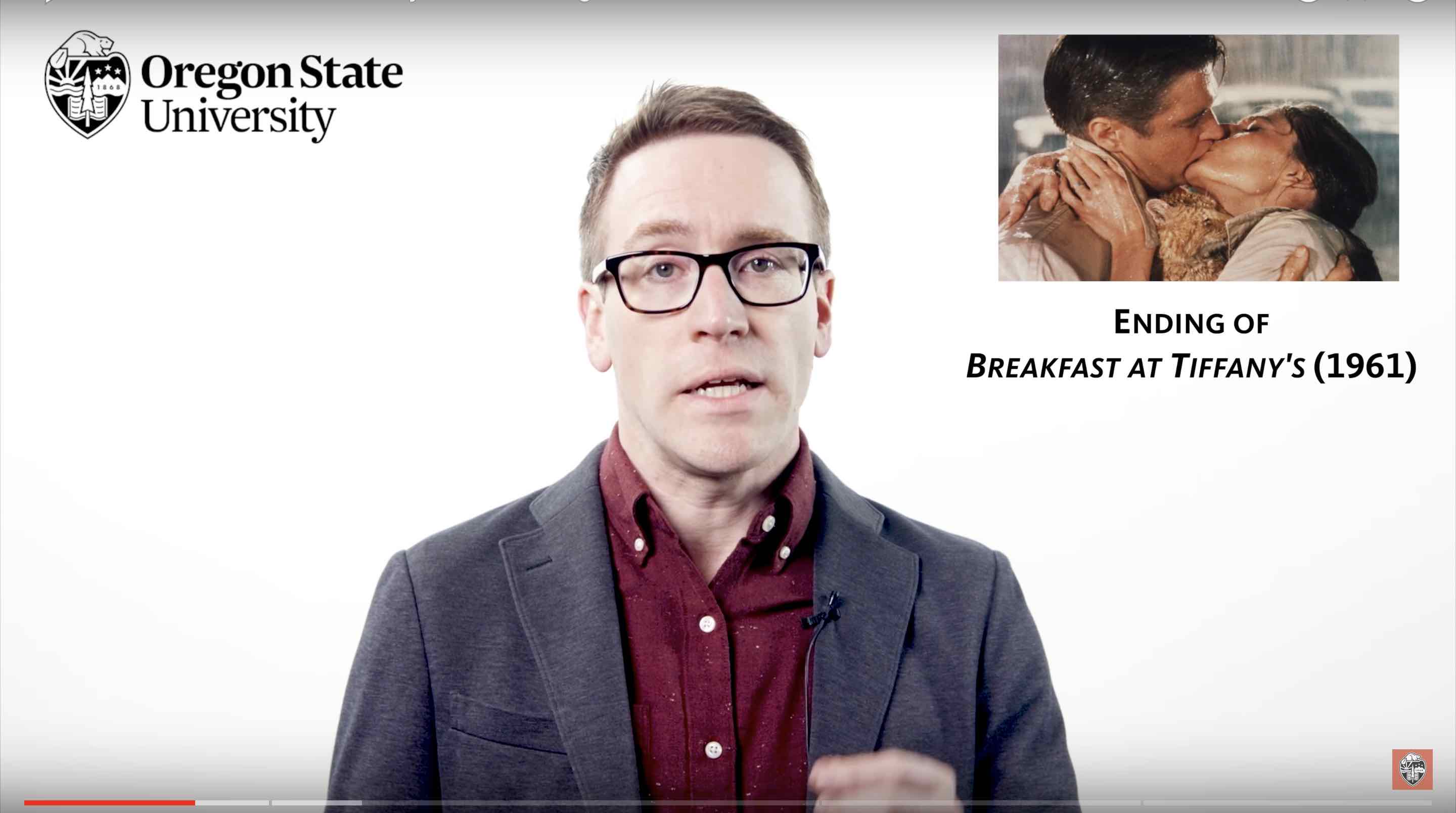

You know that moment when you’re watching a movie, and it’s been really captivating, and you’re getting interested in the characters, and a little bit lost in the story, when something shifts and you can sense what might happen next? Well in those moments, you might be experiencing what it’s like to recognize genre. And genre is a term frequently used to define the elements that repeat themselves in similar kinds of movies, books, television shows, music, and more.

I like to define genre. Genre? Jean? Jahnrah?

breakfast_at_tiffanys_kiss.jpg

Uh, let’s just go with genre (zhan-rah). OK. Genre is what some might call “typified rhetorical action” and what that means is that there are features that repeat again and again, over time, with few differences, in part because audiences expect certain things to happen or because they want certain kinds of experiences. Genre is the name we use to describe the categories that have developed over time for what we read, what we watch, and what we listen to. And the kinds of genres that exist in one culture at one time may not exist in another culture at another time – they’re constantly changing.

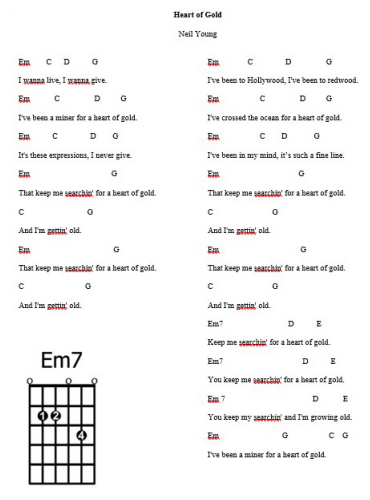

crazy_rich_asians_kiss.jpg

The main kinds of literary genre that you might be familiar with are fiction, poetry, and nonfiction. But those are the biggest categories we can think of, really. For example, non-fiction can encompass everything from a memoir, to a to a biography, to an instruction manual. All are kinds of non-fiction writing – the only thing that ties them together is that they’re not made up. The same is true for fiction and poetry, too, and when we read poetry or prose fiction, we, as the audience, have some expectations as to what should be included. That is, when we read fiction, we expect the narrative to be made up, and when we read poetry, we expect that the each line of a poem match with other lines in a particular way, or it rhyme in the manner of a sonnet , or break rules of punctuation, or simply take us through a lot of figurative language in a very short amount of time.

But those are the big genre categories. Genre gets especially interesting when we find even smaller categories like action movies, or superhero action movies, or parody superhero action movies. So think of the superhero genre this way: there’s usually an evil villain trying to do something terrible that the superhero is going to try and stop; there’s usually smaller fight scenes throughout the movie and a big fight scene at the end where the superhero, or group of superheroes, triumph, often by using their superpowers. The reason I didn’t have to mention a SPOILER ALERT is because I didn’t give any of the plot away, and you all know that superhero movies follow this pattern. That narrative pattern , and all the other ways that we can describe other repeating features, are what makes up a genre.

What’s more is that more than one genre can exist at once. Think of Ant Man. It’s a superhero movie, an action movie, a comedy, and a parody of other superhero movies. In fact, parodies are where we really see how genres work. After all, the reason Ant Man is funny is because it’s making fun of our expectations of what a superhero movie should be – its making fun of the genre of superhero movies.

ant_man_image.jpg

We use these same terms and descriptions to analyze literary works, works of nonfiction, and poetry, too. So, if I want to understand gothic novels, like Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, or Dracula by Bran Stoker, I’m going to look for literary tropes that they share. Some of those tropes could be similar kinds of characters , plots, settings , or themes . Is there a creepy stranger in a cape? Is there danger lurking in the shadows? Is there a haunted castle? Are you encouraged to think of the sinister side of humanity? If so, you might be reading a gothic novel. When I analyze a genre, I’m likely to compare and contrast those features and try to understand how one novel adheres to the conventions of a particular genre or breaks away from our expectations and does something different. We can describe a genre by showing how similar features are repeated, and those elements include most any of the many literary terms that are featured in the other videos in this series. For a gothic novel, we might see metaphors that connect events to scary or dangerous things, we might see foreshadowing of horrible events yet to come, or we might see a flashback to something terrifying that happened in them past and that changes how characters act in the present. All of these are features of a particular genre.

Now, one thing not to confuse with the idea of a genre is that of a medium. A medium is the form in which something is delivered, so we might say the medium of gothic novel is a printed book, or the medium of a superhero movie is that of film. Medium describes the kind of technology that is used to convey a story to us, but doesn’t necessarily help us understand the genre of what we’re reading or watching. People often ask me is email a genre of writing? And I respond by asking when writing an email if we’re required to write in a particular way. And for the most part, we’re not. In email, you can write a love letter, you can write an angry message to the company that sold you a dodgy product, or you can write a poem. Email itself might suggest certain kinds of writing – for example, you shouldn’t break up with someone through email – but it’s a medium that can hold lots of different genres – it itself is not a genre. Describing and analyzing genre is a powerful way to understand how narratives work, and a really useful way to make sense of stories and texts that surround us.

Want to cite this?

MLA Citation: Pflugfelder, Ehren. "What is a Genre?" Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms, 12 Feb. 2020, Oregon State University, https://liberalarts.oregonstate.edu/wlf/what-genre . Accessed [insert date].

Further Resources for Teachers

Other examples of texts that parody the genres within which they work include Jorge Luis Borges's short story "Death and the Compass," Karen Russell's "Vampires in the Lemon Grove," Lewis Carroll's "Jabberwocky," Paolo Bacigalupi's "The Tamarisk Hunter," William Shakespeare's Sonnet 130, and Chris Ware's strange short graphic narrative "Thrilling Adventure Stories (I Guess)." For an example of a character who laughs at the genre he has found himself in, see our "What is a Flashback?" video.

Writing prompt: Select one of the above examples and explain how the author invokes the genre being parodied through the example's form or content. Next, try to explain the significance of the parody. What insight does the parody provide into the limitations of the genre? What tone or attitude does the poem or short story take towards the genre it parodies?

Interested in more video lessons? View the full series:

The oregon state guide to english literary terms, contact info.

Email: [email protected]

College of Liberal Arts Student Services 214 Bexell Hall 541-737-0561

Deans Office 200 Bexell Hall 541-737-4582

Corvallis, OR 97331-8600

liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu CLA LinkedIn

- Dean's Office

- Faculty & Staff Resources

- Research Support

- Featured Stories

- Undergraduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Graduate Students

- Career Services

- Internships

- Financial Aid

- Honors Student Profiles

- Degrees and Programs

- Centers and Initiatives

- School of Communication

- School of History, Philosophy and Religion

- School of Language, Culture and Society

- School of Psychological Science

- School of Public Policy

- School of Visual, Performing and Design Arts

- School of Writing, Literature and Film

- Give to CLA

Module 3: Critical Reading

What is genre, learning objectives.

Differentiate between the goals and purposes of various genres of texts

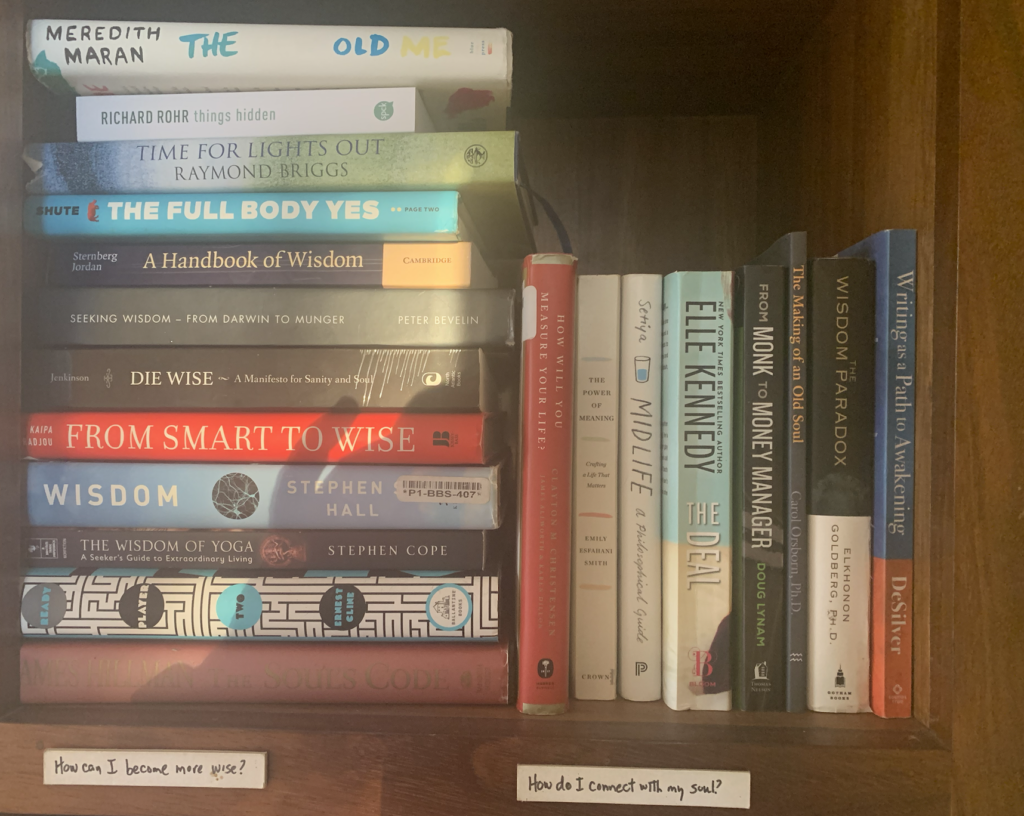

Like movies and books, music is often grouped by genre. How many musical genres can you name?

One important way to empower yourself as a reader (and also a writer) is to learn how to understand genres . The word “genre” (pronounced “john-ruh” with a soft j, like “zhaan-ruh”) comes from the French and roughly means type, kind, category, or class (in keeping with the fact that it’s related to the Latin word genus , which you might recognize from biology). You’re probably already familiar with the term in connection with movies, which are grouped into various genres: horror, Western, drama, romantic comedy, documentary, and so on. Music, as well, has genres: you’ve probably heard of hip-hop, jazz, pop, rap, and rock… but how about glitch hop, vaporwave, lowercase, or pirate metal? Genres can be quite broad, like popular music or instrumental music, or very specific, like soukous or vegan straight edge.

Have you ever watched a movie where you have no idea what the genre is? It can be pretty disconcerting. You don’t know whether you should get ready to laugh, cry, or scream. Similarly, when you go to read something, it can be helpful to know something about the genre in advance. Your approach will change depending on whether you’re reading a research paper, a blog post, a novel, or a grocery list. Each of the four types of writing just named represents a genre (type, category). You can probably think of many more, from biographies to self-help books to cookbooks. (This brings up an important point: “Genre” can refer to the overall form of a text, such as a novel or a textbook, or it can refer to a specific subcategory of that form, such as a mystery novel or a math textbook. Here, we’re more concerned with the first of these, genre-as-form.)

Genres help us communicate better both as readers and as writers. As a reader, you can understand text more easily by developing genre awareness . For example, when you pick up a biography, you know it’s going to tell the life story of a real person, so you approach it with a different set of expectations than you would a novel, which tells a fictional story. If you mistook a biography for a novel, you’d fundamentally misconstrue what you were reading. On the writer’s end, genre awareness helps to plan, organize, and craft the text better, because each genre embodies a set of rules and guidelines for fulfilling a specific purpose and meeting readers’ expectations.

Not incidentally, that’s also your best working definition as we move forward: A genre represents a pattern or set of rules that a given text follows in order to communicate its message effectively to its intended audience . When you read any written text, the aspects of rhetoric that you may have learned about in previous composition classes—purpose, audience, context, and so on—lead you to approach the reading with a certain set of expectations. The concept of genre encompasses these things and provides the added benefit of a pattern or “recipe” for you to follow.

The first step to enjoying this benefit is simply to become more genre-aware. Learn to recognize that virtually everything you read follows the rules of a certain genre. Use this recognition to approach and attack your reading more enjoyably and intelligently.

The Goals and Purposes of Different Academic Genres

The key to understanding a genre is first to understand its purpose. Each genre sets out to accomplish something specific. For example, as mentioned above, the purpose of any biography is to tell someone’s life story. You have to understand this at the outset to understand what you’re reading.

You’ll improve your success as a college student if you understand the goals and purposes of the genres that you’re most likely to encounter in the college setting. These include textbooks, scholarly articles, reference works, journalism, and works of literature. Each of these displays typical features that are related to its primary purpose.

A Note about Academic Genres

When thinking about genres, remember two things about the reading and writing that you’ll do in this class, and also in the entirety of your college career.

First, academic writing forms of its own subset of genres. In a composition class, you may read texts belonging to any or all of the genres you’ve been learning about here. You may also write texts in a variety of genres, including genres that have been developed mainly for classroom learning purposes, such as the five-paragraph essay, the informative research paper, and the persuasive research paper. As you learned in the first section of this module, there’s also an entire world of professional academic/scholarly writing. Student academic writing and professional scholarly writing both follow their own sets of genre recipes for producing writing with specific characteristics to fulfill specific purposes within the educational context.

Second, academic writing is not intrinsically more intelligent, more important, or otherwise “better” than other types of writing. Rather, it’s just one subset of genres among many. It’s a collection of genres that are useful within their intended contexts, for their given purposes. And as with any genre, to be successful in academic ones, it’s simply the case that you need to become familiar with their rules and patterns (such as the use of an academic citation format — MLA, APA, Chicago style, or another — when writing a research paper or scholarly article).

- Video: Understanding genre awareness. Provided by : CAES HKU. Located at : https://youtu.be/Daut5e0kWBo . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Image: Textbooks. Authored by : Logan Ingalls. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/cStoi . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Enyclopedia Britannica International Chinese Edition. Authored by : Hawyih. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Enyclopedia_Britannica_International_Chinese_Edition.jpg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Polish sci-fi and fantasy books. Authored by : Piotrus. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Polish_sci_fi_fantasy_books.JPG . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cairo newsstand. Authored by : flyvancity. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2010_newsstand_Cairo_4508283265.jpg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- More and More Genres. Authored by : lukatoyboy. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/4ACv8C . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- What is Genre?. Authored by : Matt Cardin. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- Join the author community

- About Essays in Criticism

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Ralph Cohen and the Principles of Genre

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Michael B Prince, Ralph Cohen and the Principles of Genre, Essays in Criticism , Volume 71, Issue 1, January 2021, Pages 66–79, https://doi.org/10.1093/escrit/cgaa026

- Permissions Icon Permissions

THE CONCEPT OF GENRE has had great staying power. Aristotle’s method of describing the origin, achievement, and decline of forms in his Poetics retains its force. Open any recent textbook for college composition; consult new work in rhetoric, media, and gender studies; observe the confusion that arises when the digital humanities pursues big data without a theory of classification: today, genre is more relevant than ever. Twenty essays by Ralph Cohen, recently edited by John L. Rowlett, help to explain why. 1

Born on 23 February 1917, Cohen died exactly ninety-nine years later. He received his BA from the City College of New York in 1937. His education was interrupted by the Second World War, during which he served in the US Army Signal Corps. He did not complete his Ph.D. at Columbia University until 1952, when he was 35. By the time Cohen wrote the earliest of the essays collected by Rowlett, essays which span the years 1970-2010, he had been publishing books, essays, reviews, and editions of literary criticism and philosophy for twenty years. His essays articulate a view of literary theory and history that Cohen had developed over the preceding decades.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1471-6852

- Print ISSN 0014-0856

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Campus Library Info.

- ARC Homepage

- Library Resources

- Articles & Databases

- Books & Ebooks

Baker College Research Guides

- Research Guides

- General Education

COM 1010: Composition and Critical Thinking I

- Understanding Genre and Genre Analysis

- The Writing Process

- Essay Organization Help

- Understanding Memoir

- What is a Book Cover (Not an Infographic)?

- Understanding PowerPoint and Presentations

- Understanding Summary

- What is a Response?

- Structuring Sides of a Topic

- Locating Sources

- What is an Annotated Bibliography?

- What is a Peer Review?

- Understanding Images

- What is Literacy?

- What is an Autobiography?

- Shifting Genres

Understanding What is Meant by the Word "Genre"

What do we mean by genre? This means a type of writing, i.e., an essay, a poem, a recipe, an email, a tweet. These are all different types (or categories) of writing, and each one has its own format, type of words, tone, and so on. Analyzing a type of writing (or genre) is considered a genre analysis project. A genre analysis grants students the means to think critically about how a particular form of communication functions as well as a means to evaluate it.

Every genre (type of writing/writing style) has a set of conventions that allow that particular genre to be unique. These conventions include the following components:

- Tone: tone of voice, i.e. serious, humorous, scholarly, informal.

- Diction : word usage - formal or informal, i.e. “disoriented” (formal) versus “spaced out” (informal or colloquial).

- Content : what is being discussed/demonstrated in the piece? What information is included or needs to be included?

- Style / Format (the way it looks): long or short sentences? Bulleted list? Paragraphs? Short-hand? Abbreviations? Does punctuation and grammar matter? How detailed do you need to be? Single-spaced or double-spaced? Can pictures / should pictures be included? How long does it need to be / should be? What kind of organizational requirements are there?

- Expected Medium of Genre : where does the genre appear? Where is it created? i.e. can be it be online (digital) or does it need to be in print (computer paper, magazine, etc)? Where does this genre occur? i.e. flyers (mostly) occur in the hallways of our school, and letters of recommendation (mostly) occur in professors’ offices.

- Genre creates an expectation in the minds of its audience and may fail or succeed depending on if that expectation is met or not.

- Many genres have built-in audiences and corresponding publications that support them, such as magazines and websites.

- The goal of the piece that is written, i.e. a newspaper entry is meant to inform and/or persuade, and a movie script is meant to entertain.

- Basically, each genre has a specific task or a specific goal that it is created to attain.

- Understanding Genre

- Understanding the Rhetorical Situation

To understand genre, one has to first understand the rhetorical situation of the communication.

Below are some additional resources to assist you in this process:

- Reading and Writing for College

Genre Analysis

Genre analysis: A tool used to create genre awareness and understand the conventions of new writing situations and contexts. This a llows you to make effective communication choices and approach your audience and rhetorical situation appropriately

Basically, when we say "genre analysis," that is a fancy way of saying that we are going to look at similar pieces of communication - for example a handful of business memos - and determine the following:

- Tone: What was the overall tone of voice in the samples of that genre (piece of writing)?

- Diction : What was the overall type of writing in the three samples of that genre (piece of writing)? Formal or informal?

- Content : What types(s) of information is shared in those pieces of writing?

- Style / Format (the way it looks): Do the pieces of communication contain long or short sentences? Bulleted list? Paragraphs? Abbreviations? Does punctuation and grammar matter? How detailed do you need to be in that type of writing style? Single-spaced or double-spaced? Are pictures included? If so, why? How long does it need to be / should be? What kind of organizational requirements are there?

- Expected Medium of Genre : Where did the pieces appear? Were they online? Where? Were they in a printed, physical context? If so, what?

- Audience: What audience is this piece of writing trying to reach?

- Purpose : What is the goal of the piece of writing? What is its purpose? Example: the goal of the piece that is written, i.e. a newspaper entry is meant to inform and/or persuade, and a movie script is meant to entertain.

In other words, we are analyzing the genre to determine what are some commonalities of that piece of communication.

For additional help, see the following resource for Questions to Ask When Completing a Genre Analysis .

- << Previous: The Writing Process

- Next: Essay Organization Help >>

- Last Updated: Feb 23, 2024 2:08 PM

- URL: https://guides.baker.edu/com1010

- Search this Guide Search

Definition of Genre

Genre originates from the French word meaning kind or type. As a literary device, genre refers to a form, class, or type of literary work. The primary genres in literature are poetry, drama / play , essay , short story , and novel . The term genre is used quite often to denote literary sub-classifications or specific types of literature such as comedy , tragedy , epic poetry, thriller , science fiction , romance , etc.

It’s important to note that, as a literary device, the genre is closely tied to the expectations of readers. This is especially true for literary sub-classifications. For example, Jane Austen ’s work is classified by most as part of the romance fiction genre, as demonstrated by this quote from her novel Sense and Sensibility :

When I fall in love, it will be forever.

Though Austen’s work is more complex than most formulaic romance novels, readers of Austen’s work have a set of expectations that it will feature a love story of some kind. If a reader found space aliens or graphic violence in a Jane Austen novel, this would undoubtedly violate their expectations of the romantic fiction genre.

Difference Between Style and Genre

Although both seem similar, the style is different from the genre. In simple terms, style means the characters or features of the work of a single person or individual. However, the genre is the classification of those words into broader categories such as modernist, postmodernist or short fiction and novels, and so on. Genres also have sub-genre, but the style does not have sub-styles. Style usually have further features and characteristics.

Common Examples of Genre

Genres could be divided into four major categories which also have further sub-categories. The four major categories are given below.

- Poetry: It could be categorized into further sub-categories such as epic, lyrical poetry, odes , sonnets , quatrains , free verse poems, etc.

- Fiction : It could be categorized into further sub-categories such as short stories, novels, skits, postmodern fiction, modern fiction, formal fiction, and so on.

- Prose : It could be further categorized into sub-genres or sub-categories such as essays, narrative essays, descriptive essays, autobiography , biographical writings, and so on.

- Drama: It could be categorized into tragedy, comedy, romantic comedy, absurd theatre, modern play, and so on.

Common Examples of Fiction Genre

In terms of literature, fiction refers to the prose of short stories, novellas , and novels in which the story originates from the writer’s imagination. These fictional literary forms are often categorized by genre, each of which features a particular style, tone , and storytelling devices and elements.

Here are some common examples of genre fiction and their characteristics:

- Literary Fiction : a work with artistic value and literary merit.

- Thriller : features dark, mysterious, and suspenseful plots.

- Horror : intended to scare and shock the reader while eliciting a sense of terror or dread; may feature scary entities such as ghosts, zombies, evil spirits, etc.

- Mystery : generally features a detective solving a case with a suspenseful plot and slowly revealing information for the reader to piece together.

- Romance : features a love story or romantic relationship; generally lighthearted, optimistic, and emotionally satisfying.

- Historical : plot takes place in the past with balanced realism and creativity; can feature actual historical figures, events, and settings.

- Western : generally features cowboys, settlers, or outlaws of the American Old West with themes of the frontier.

- Bildungsroman : story of a character passing from youth to adulthood with psychological and/or moral growth; the character becomes “educated” through loss, a journey, conflict , and maturation.

- Science Fiction : speculative stories derived and/or inspired by natural and social sciences; generally features futuristic civilizations, time travel, or space exploration.

- Dystopian : sub-genre of science fiction in which the story portrays a setting that may appear utopian but has a darker, underlying presence that is problematic.

- Fantasy : speculative stories with imaginary characters in imaginary settings; can be inspired by mythology or folklore and generally include magical elements.

- Magical Realism : realistic depiction of a story with magical elements that are accepted as “normal” in the universe of the story.

- Realism : depiction of real settings, people, and plots as a means of approaching the truth of everyday life and laws of nature.

Examples of Writers Associated with Specific Genre Fiction

Writers are often associated with a specific genre of fictional literature when they achieve critical acclaim, public notoriety, and/or commercial success with readers for a particular work or series of works. Of course, this association doesn’t limit the writer to that particular genre of fiction. However, being paired with a certain type of literature can last for an author’s entire career and beyond.

Here are some examples of writers that have become associated with specific fiction genre:

- Stephen King: horror

- Ray Bradbury : science fiction

- Jackie Collins: romance

- Toni Morrison: black feminism

- John le Carré: espionage

- Philippa Gregory: historical fiction

- Jacqueline Woodson: racial identity fiction

- Philip Pullman: fantasy

- Flannery O’Connor: Southern Gothic

- Shel Silverstein: children’s poetry

- Jonathan Swift : satire

- Larry McMurtry: western

- Virginia Woolf: feminism

- Raymond Chandler: detective fiction

- Colson Whitehead: Afrofuturism

- Gabriel García Márquez : magical realism

- Madeleine L’Engle: children’s fantasy fiction

- Agatha Christie : mystery

- John Green : young adult fiction

- Margaret Atwood: dystopian

Famous Examples of Genre in Other Art Forms

Most art forms feature genre as a means of identifying, differentiating, and categorizing the many forms and styles within a particular type of art. Though there are many crossovers when it comes to genre and no finite boundaries, most artistic works within a particular genre feature shared patterns , characteristics, and conventions.

Here are some famous examples of genres in other art forms:

- Music : rock, country, hip hop, folk, classical, heavy metal, jazz, blues

- Visual Art : portrait, landscape, still life, classical, modern, impressionism, expressionism

- Drama : comedy, tragedy, tragicomedy , melodrama , performance, musical theater, illusion

- Cinema : action, horror, drama, romantic comedy, western, adventure , musical, documentary, short, biopic, fantasy, superhero, sports

Examples of Genre in Literature

As a literary device, the genre is like an implied social contract between writers and their readers. This does not mean that writers must abide by all conventions associated with a specific genre. However, there are organizational patterns within a genre that readers tend to expect. Genre expectations allow readers to feel familiar with the literary work and help them to organize the information presented by the writer. In addition, keeping with genre conventions can establish a writer’s relationship with their readers and a framework for their literature.

Here are some examples of genres in literature and the conventions they represent:

Example 1: Macbeth by William Shakespeare

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow , Creeps in this petty pace from day to day To the last syllable of recorded time, And all our yesterdays have lighted fools The way to dusty death. Out, out , brief candle! Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player That struts and frets his hour upon the stage And then is heard no more: it is a tale Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, Signifying nothing.

The formal genre of this well-known literary work is Shakespearean drama or play. Macbeth can be sub-categorized as a literary tragedy in that the play features the elements of a classical tragic work. For example, Macbeth’s character aligns with the traits and path of a tragic hero –a protagonist whose tragic flaw brings about his downfall from power to ruin. This tragic arc of the protagonist often results in catharsis (emotional release) and potential empathy among readers and members of the audience .

In addition to featuring classical characteristics and conventions of the tragic genre, Shakespeare’s play also resonates with modern readers and audiences as a tragedy. In this passage, one of Macbeth’s soliloquies , his disillusionment, and suffering is made clear in that, for all his attempts and reprehensible actions at gaining power, his life has come to nothing. Macbeth realizes that death is inevitable, and no amount of power can change that truth. As Macbeth’s character confronts his mortality and the virtual meaninglessness of his life, readers and audiences are called to do the same. Without affirmation or positive resolution , Macbeth’s words are as tragic for readers and audiences as they are for his own character.

Like M a cbeth , Shakespeare’s tragedies are as currently relevant as they were when they were written. The themes of power, ambition, death, love, and fate incorporated in his tragic literary works are universal and timeless. This allows tragedy as a genre to remain relatable to modern and future readers and audiences.

Example 2: The Color Purple by Alice Walker

All my life I had to fight. I had to fight my daddy . I had to fight my brothers. I had to fight my cousins and my uncles. A girl child ain’t safe in a family of men. But I never thought I’d have to fight in my own house. She let out her breath. I loves Harpo, she say. God knows I do. But I’ll kill him dead before I let him beat me.

The formal genre of this literary work is novel. Walker’s novel can be sub-categorized within many fictional genres. This passage represents and validates its sub-classification within the genre of feminist fiction. Sofia’s character, at the outset, is assertive as a black woman who has been systematically marginalized in her community and family, and she expresses her independence from the dominance and control of men. Sofia is a foil character for Celie, the protagonist, who often submits to the power, control, and brutality of her husband. The juxtaposition of these characters indicates the limited options and harsh consequences faced by women with feminist ideals in the novel.

Unfortunately, Sofia’s determination to fight for herself leads her to be beaten close to death and sent to prison when she asserts herself in front of the white mayor’s wife. However, Sofia’s strong feminist traits have a significant impact on the other characters in the novel, and though she is not able to alter the systemic racism and subjugation she faces as a black woman, she does maintain her dignity as a feminist character in the novel.

Example 3: A Word to Husbands by Ogden Nash

To keep your marriage brimming With love in the loving cup, Whenever you’re wrong, admit it; Whenever you’re right, shut up.

The formal genre of this literary work is poetry. Nash’s poem would be sub-categorized within the genre of humor . The poet’s message to what is presumably his fellow husbands is witty, clear, and direct–through the wording and message of the last poetic line may be unexpected for many readers. In addition, the structure of the poem sets up the “punchline” at the end. The piece begins with poetic wording that appears to romanticize love and marriage, which makes the contrasting “base” language of the final line a satisfying surprise and ironic twist for the reader. The poet’s tone is humorous and light-hearted which also appeals to the characteristics and conventions of this genre.

Synonyms of Genre

Genre doesn’t have direct synonyms . A few close meanings are category, class, group, classification, grouping, head, heading, list, set, listing, and categorization. Some other words such as species, variety, family, school, and division also fall in the category of its synonyms.

Post navigation

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Essay Writing

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This resource begins with a general description of essay writing and moves to a discussion of common essay genres students may encounter across the curriculum. The four genres of essays (description, narration, exposition, and argumentation) are common paper assignments you may encounter in your writing classes. Although these genres, also known as the modes of discourse, have been criticized by some composition scholars, the Purdue OWL recognizes the wide spread use of these genres and students’ need to understand and produce these types of essays. We hope these resources will help.

The essay is a commonly assigned form of writing that every student will encounter while in academia. Therefore, it is wise for the student to become capable and comfortable with this type of writing early on in her training.

Essays can be a rewarding and challenging type of writing and are often assigned either to be done in class, which requires previous planning and practice (and a bit of creativity) on the part of the student, or as homework, which likewise demands a certain amount of preparation. Many poorly crafted essays have been produced on account of a lack of preparation and confidence. However, students can avoid the discomfort often associated with essay writing by understanding some common genres.

Before delving into its various genres, let’s begin with a basic definition of the essay.

What is an essay?

Though the word essay has come to be understood as a type of writing in Modern English, its origins provide us with some useful insights. The word comes into the English language through the French influence on Middle English; tracing it back further, we find that the French form of the word comes from the Latin verb exigere , which means "to examine, test, or (literally) to drive out." Through the excavation of this ancient word, we are able to unearth the essence of the academic essay: to encourage students to test or examine their ideas concerning a particular topic.

Essays are shorter pieces of writing that often require the student to hone a number of skills such as close reading, analysis, comparison and contrast, persuasion, conciseness, clarity, and exposition. As is evidenced by this list of attributes, there is much to be gained by the student who strives to succeed at essay writing.

The purpose of an essay is to encourage students to develop ideas and concepts in their writing with the direction of little more than their own thoughts (it may be helpful to view the essay as the converse of a research paper). Therefore, essays are (by nature) concise and require clarity in purpose and direction. This means that there is no room for the student’s thoughts to wander or stray from his or her purpose; the writing must be deliberate and interesting.

This handout should help students become familiar and comfortable with the process of essay composition through the introduction of some common essay genres.

This handout includes a brief introduction to the following genres of essay writing:

- Expository essays

- Descriptive essays

- Narrative essays

- Argumentative (Persuasive) essays

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Understanding Discourse Communities

This chapter uses John Swales’ definition of discourse community to explain to students why this concept is important for college writing and beyond. The chapter explains how genres operate within discourse communities, why different discourse communities have different expectations for writing, and how to understand what qualifies as a discourse community. The article relates the concept of discourse community to a personal example from the author (an acoustic guitar jam group) and an example of the academic discipline of history. The article takes a critical stance regarding the concept of discourse community, discussing both the benefits and constraints of communicating within discourse communities. The article concludes with writerly questions students can ask themselves as they enter new discourse communities in order to be more effective communicators.