How to Become a Research Nurse

What is a research nurse.

- Career Outlook

Research Nurses, also referred to as Clinical Nurse Researchers or Nurse Researchers, develop and implement studies to investigate and provide information on new medications, vaccinations, and medical procedures. They assist in providing evidence-based research that is essential to safe and quality nursing care. This guide will explain what a Research Nurse does, how much they make, how to become one, and more!

Research nurses play a pivotal role in developing new and potentially life-saving medical treatments. Typically, clinical research nurses have advanced degrees, assist in the development of studies regarding medications, vaccines, and medical procedures, and also the care of research participants.

Nurses that know they want to be a clinical research nurse will often work as a research assistant, a clinical data collector, and/or clinical research monitor. It is essential to gain some bedside experience, but not as important as other nursing specialties.

Clinical research nurses have advanced degrees such as an MSN or Ph.D. This is vital to those that want to conduct independent research. For that reason, most clinical research nurses do not work in this field until they are in their 40s-50s.

Find Nursing Programs

What does a research nurse do.

Research Nurses primarily conduct evidence-based research through these two types of research methods:

- Quantitative: Meaning it’s researched that can be measured via statistical, mathematical, or computational techniques.

- Phenomenology

- Grounded Theory

- Ethnography

- Narrative Inquiry

Clinical research nurses perform a variety of tasks, all centered around research. These specific job responsibilities include:

- Collaborating with industry sponsors and other investigators from multi-institutional studies

- Educating and training of new research staff

- Overseeing the running of clinical trials

- Administering questionnaires to clinical trial participants

- Writing articles and research reports in nursing or medical professional journals or other publications

- Monitoring research participants to ensure adherence to study rules

- Adhering to research regulatory standards

- Writing grant applications to secure funding for studies

- Reporting findings of research, which may include presenting findings at industry conferences, meetings and other speaking engagements

- Adhering to ethical standards

- Maintaining detailed records of studies as per FDA guidelines, including things such as drug dispensation

- Participating in subject recruitment efforts

- Ensuring the necessary supplies and equipment for a study are in stock and in working order

- Engaging with subjects and understanding their concerns

- Providing patients with thorough explanation of trial prior to obtaining Informed Consent, in collaboration with treating physician and provides patient education on an ongoing basis throughout the patient’s course of trial.

>> Show Me Online MSN Programs

Research Nurse Salary

Glassdoor.com states an annual median salary of $95,396 for Research Nurses and Payscale reports that Clinical Research Nurses earn an average annual salary of $75,217 or $36.86/hr .

Research Nurse Salary by Years of Experience

Research Nurses can earn a higher annual salary with increased years of experience.

- Less than 1 year of experience earn an average salary of $68,000

- 1-4 years of experience earn an average salary of $73,000

- 5-9 years of experience earns an average salary of $73,000

- 10-19 years of experience earns an average salary of $80,000

- 20 years or more of experience earns an average salary of $78,000

Via Payscale

To become a Research Nurse, you’ll need to complete the following steps:

Step 1: Attend Nursing School

You’ll need to earn either an ADN or a BSN from an accredited nursing program in order to take the first steps to become a registered nurse.

Step 2: Pass the NCLEX-RN

Become a Registered Nurse by passing the NCLEX examination.

Step 3: Gain Experience at the Bedside

Though not as important as in some other nursing careers, gaining experience is still a vital step for those wanting to become Nurse Researchers.

Step 4: Earn an MSN and/or Ph.D

Research Nurses typically need an advanced degree, so ADN-prepared nurses will need to complete an additional step of either completing their BSN degree or entering into an accelerated RN to MSN program which will let them earn their BSN and MSN at the same time.

Step 5: Earn Your Certification

There are currently two certifications available for Clinical Research Nurses. They are both offered by the Association of Clinical Research Professionals.

- Clinical Research Association (CCRA)

- Clinical Research Coordinator (CCRC)

These certifications are not specific to nurses but rather those that work in the research field.

CCRA Certification

In order to be deemed eligible for the CCRA Certification exam, applicants must attest to having earned 3,000 hours of professional experience performing the knowledge and tasks located in the six content areas of the CRA Detailed Content Outline. Any experience older than ten years will not be considered.

What’s on the Exam?

- Scientific Concepts and Research Design

- Ethical and Participant Safety Considerations

- Product Development and Regulation

- Clinical Trial Operations (GCPs)

- Study and Site Management

- Data Management and Informatics

Exam Information

- Exam Fee: $435 Member; $485 Nonmember

- Exam Fee: $460 Member; $600 Nonmember

- Multiple choice examination with 125 questions (25 pretest non-graded questions)

CCRC Certification

In order to be deemed eligible for the CCRC Certification exam, applicants must attest to having earned 3,000 hours of professional experience performing the knowledge and tasks located in the six content areas of the CCRC Detailed Content Outline. Any experience older than ten years will not be considered.

Where Do Research Nurses Work?

Clinical Research nurses can work in a variety of locations, including:

- Government Agencies

- Teaching Hospitals

- Medical Clinics

- International Review Board

- Medicine manufacturing

- Pharmaceutical companies

- Medical research organizations

- Research Organizations

- International Health Organizations

- Private practice

- Private and public foundations

What is the Career Outlook for a Research Nurse?

According to the BLS , from 2022 to 2032, there is an expected growth of 6% for registered nurses. With the aging population and nursing shortage, this number is expected to be even higher.

The BLS does identify medical scientists, which includes clinical research nurses, as having a growth potential of 10% between 2022-2032.

What are the Continuing Education Requirements for a Research Nurse?

Generally, in order for an individual to renew their RN license, they will need to fill out an application, complete a specific number of CEU hours, and pay a nominal fee. Each state has specific requirements and it is important to check with the board of nursing prior to applying for license renewal.

If the RN license is part of a compact nursing license, the CEU requirement will be for the state of permanent residence. Furthermore, some states require CEUs related to child abuse, narcotics, and/or pain management.

A detailed look at Continuing Nurse Education hours can be found here .

Where Can I Learn More About Becoming a Research Nurse?

- American Nurses Association (ANA)

- Nurse Researcher Magazine

- National Institute of Nursing Research

- International Association of Clinical Research Nurses

- Association of Clinical Research Professionals

- Society of Clinical Research Associates

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing

Research Nurse FAQs

What is the role of a research nurse.

- Research nursing is a nursing practice with a specialty focus on the care of research participants.

What makes a good Research Nurse?

- Research Nurses should be excellent communicators, have strong attention to detail, be self-assured, have strong clinical abilities, be flexible, autonomous, organized, and eager to learn new information.

How much does a Research Nurse make?

- Research nurses earn an average salary of $95,396 according to Glassdoor.com.

What is it like being a Research Nurse?

- Research Nurses provide and coordinate clinical care. Research Nurses have a central role in ensuring participant safety, maintaining informed consent, the integrity of protocol implementation, and the accuracy of data collection and data recording.

Kathleen Gaines (nee Colduvell) is a nationally published writer turned Pediatric ICU nurse from Philadelphia with over 13 years of ICU experience. She has an extensive ICU background having formerly worked in the CICU and NICU at several major hospitals in the Philadelphia region. After earning her MSN in Education from Loyola University of New Orleans, she currently also teaches for several prominent Universities making sure the next generation is ready for the bedside. As a certified breastfeeding counselor and trauma certified nurse, she is always ready for the next nursing challenge.

Plus, get exclusive access to discounts for nurses, stay informed on the latest nurse news, and learn how to take the next steps in your career.

By clicking “Join Now”, you agree to receive email newsletters and special offers from Nurse.org. We will not sell or distribute your email address to any third party, and you may unsubscribe at any time by using the unsubscribe link, found at the bottom of every email.

- Mayo Clinic Careers

- Anesthesiology

- Dermatology

- Emergency Medicine

- Family Medicine

- Internal Medicine

- Lung Transplant

- Psychiatry & Psychology

- Nurse Practitioner & Physician Assistant

- Ambulance Service

- Clinical Labs

- Med Surg RN

- Radiology Imaging

- Clinical Research Coordinator

- Respiratory Care

- Senior Care

- Surgical Services

- Travel Surgical Tech

- Practice Operations

- Administrative Fellowship Program

- Administrative Internship Program

- Career Exploration

- Nurse Residency and Training Program

- Nursing Intern/Extern Programs

- Residencies & Fellowships (Allied Health)

- Residencies & Fellowships (Medical)

- SkillBridge Internship Program

- Training Programs & Internships

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

- Employees with Disabilities

Life-changing careers

Search life-changing careers.

Search by Role or Keyword

Enter Location

- United States Applicants

- United Kingdom Applicants

- Current Employees

Remote Opportunities

Mayo Clinic offers a variety of remote job opportunities. During the global pandemic, we readily embraced the move to a remote working model for the health and safety of our employees. It became evident that our teams were equally collaborative and continued to support the Mayo Clinic mission and values. As the pandemic eases and we look towards the future, Mayo will continue to support remote work for teams whose work is not reliant on campus resources.

Join a company culture that encourages balance and wellness, with plenty of opportunities for career development!

Current Remote Job Openings

- IT Help Desk Specialist - Remote Information Technology 334596

- Senior Manager-Rev Cycle Application Supp-Remote Business 330997

- Statistical Programmer (Remote) Research 334558

- Intern-Biostatistics (BS) Internship 334397

- IT Lead Software Engineer - Remote Information Technology 333247

- Senior Manager Quality & Regulatory Operations MCS Laboratory, Business 334456

- Senior AI RAQA Specialist - CDH - Remote Business 334494

- CDI SPECIALIST I Business 334255

- Intern -Undergraduate - Ortho Research - Remote - Temporary Research 333148

- Senior Automation Solutions – Tech Specialist II Information Technology 331775

Join Our Talent Community

Sign up, stay connected and get opportunities that match your skills sent right to your inbox

Email Address

Phone Number

Upload Resume/CV (Must be under 1MB) Remove

Job Category* Select One Advanced Practice Providers Business Education Engineering Executive Facilities Support Global Security Housekeeping Information Technology Internship Laboratory Nursing Office Support Patient Care - Other Pharmacy Phlebotomy Physician Post Doctoral Radiology Imaging Research Scientist Surgical Services Therapy

Location Select Location Albert Lea, Minnesota Arcadia, Wisconsin Austin, Minnesota Barron, Wisconsin Bloomer, Wisconsin Caledonia, Minnesota Cannon Falls, Minnesota Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin Decorah, Iowa Duluth, Minnesota Eau Claire, Wisconsin Fairmont, Minnesota Faribault, Minnesota Holmen, Wisconsin Jacksonville, Florida La Crosse, Wisconsin Lake City, Minnesota London, England Mankato, Minnesota Menomonie, Wisconsin Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, Minnesota New Prague, Minnesota Onalaska, Wisconsin Osseo, Wisconsin Owatonna, Minnesota Phoenix, Arizona Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin Red Wing, Minnesota Rice Lake, Wisconsin Rochester, Minnesota Saint Cloud, Minnesota Saint James, Minnesota Scottsdale, Arizona Sparta, Wisconsin Tomah, Wisconsin Waseca, Minnesota Zumbrota, Minnesota

Area of Interest Select One Nursing Research Radiology Laboratory Medicine & Pathology Facilities Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN) Neurology Pharmacy Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation Cardiovascular Medicine Surgery General Services Psychiatry & Psychology Mayo Collaborative Services Respiratory Therapy Ambulance Services Environmental Services Finance Anesthesiology & Perioperative Medicine Mayo Clinic Laboratories Surgical Technician Emergency Medicine Orthopedics Social Work Family Medicine Gastroenterology & Hepatology International Hospital Internal Medicine Medical Oncology Radiation Oncology Global Security Information Technology Obstetrics & Gynecology Office Support Hematology Housekeeping Pediatrics Senior Care Transplant Cardiovascular Surgery Critical Care General Internal Medicine Hospice & Palliative Care Ophthalmology Patient Scheduling Administration Pulmonary/Sleep Medicine Education Engineering Artificial Intelligence & Informatics Dermatology Desk Operations Oncology Sports Medicine Urology Biochemistry & Molecular Biology Community Internal Medicine Linen & Central Services Nephrology & Hypertension Physiology & Biomedical Engineering Surgical Assistant Clinical Genomics Endocrinology Health Care Delivery Research Immunology Infectious Diseases Neurosciences Otolaryngology (ENT) Regenerative Biotherapeutics Rheumatology Cancer Center Clinical Trials & Biostatistics Digital Epidemiology Molecular Medicine Molecular Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics Primary Care Quality Business Development Development/Philanthropy Legal Neurologic Surgery Pain Medicine Women's Health Allergic Diseases Bariatric Medicine Cancer Biology Center for Individualized Medicine Clinical Nutrition Comparative Medicine Dental Specialities Geriatric Medicine & Gerontology Healthcare Technology Management Informatics Information Security Marketing Occupational/Preventative Medicine Spine Center Spiritual Care Travel Urgent Care Volunteer Services

Confirm Email

By submitting your information, you consent to receive email communication from Mayo Clinic.

Equal opportunity

All qualified applicants will receive consideration for employment without regard to race, color, religion, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, national origin, protected veteran status, or disability status. Learn more about "EEO is the Law." Mayo Clinic participates in E-Verify and may provide the Social Security Administration and, if necessary, the Department of Homeland Security with information from each new employee's Form I-9 to confirm work authorization.

Reasonable accommodations

Mayo Clinic provides reasonable accommodations to individuals with disabilities to increase opportunities and eliminate barriers to employment. If you need a reasonable accommodation in the application process; to access job postings, to apply for a job, for a job interview, for pre-employment testing, or with the onboarding process, please contact HR Connect at 507-266-0440 or 888-266-0440.

Job offers are contingent upon successful completion of a post offer placement assessment including a urine drug screen, immunization review and tuberculin (TB) skin testing, if applicable.

Recruitment Fraud

Learn more about recruitment fraud and job scams

Advertising

Mayo Clinic is a not-for-profit organization and proceeds from Web advertising help support our mission. Mayo Clinic does not endorse any of the third party products and services advertised.

Advertising and sponsorship policy | Advertising and sponsorship opportunities

Reprint permissions

A single copy of these materials may be reprinted for noncommercial personal use only. "Mayo," "Mayo Clinic," "MayoClinic.org," "Mayo Clinic Healthy Living," and the triple-shield Mayo Clinic logo are trademarks of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.

Any use of this site constitutes your agreement to the Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy linked below.

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy | Notice of Privacy Practices | Notice of Nondiscrimination

© 1998-2024 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved.

Clinical Research Nurse Work From Home jobs

Registered nurse (rn) - virtual - placement & logis.

Registered Nurse RN - Virtual Interview Event!

Eacute virtual care nurse - 9e medical-surgical - (internal only) (on-site), registered nurse (rn) - mds coordinator - long-term care.

Avera Mother Joseph Manor Ret Comm

RN Virtual Acute Care

Registered nurse - atrium health hospice home care cabarrus pt remote weekend days, clinical trial educator - renal dialysis exp. (remote).

Randstad Life Sciences Us

Clinical Field Staff Supervisor - RN

Aletheia Staffing

Travel Nurse RN - OR - Operating Room - $2,970 per week

Clinical reviewer utilization management rn, travel nurse rn - home health - $2,282 per week in bronx, ny, rn pulmonary clinic.

Corewell Health

NP / Clinic RN / Florida / Permanent / IMMEDIATE OPENING For a NURSE Job

Revenue cycle appeals registered nurse - remote.

Conifer Revenue Cycle Solutions

Travel Nurse RN - PCU - $2,129 per week in Allentown, PA

Travelnursesource

Infojini Healthcare

Per Diem / PRN Nurse RN - Clinic - $28+ per hour

Travel nurse rn - virtual care - $2,844 per week.

- Registered Nurse

RN and LPN in Waianae - $5K Bonus - New Grab Welcome!

Wilson Care Group

Learn More About Clinical Research Nurse Jobs

Work from home clinical research nurse jobs.

- Work From Home Clinic Registered Nurse Jobs

- Work From Home Clinical Care Coordinator Jobs

- Work From Home Clinical Educator Jobs

- Work From Home Nurse Jobs

- Work From Home Nurse Clinician Jobs

- Work From Home Pediatric Nurse Jobs

- Work From Home Registered Health Nurse Jobs

- Work From Home Registered Nurse Jobs

- Work From Home Registered Nurse In The ICU Jobs

- Work From Home Registered Professional Nurse Jobs

- Work From Home Research Nurse Jobs

- Work From Home Staff Nurse Jobs

- Work From Home Traveling Nurse Jobs

Clinical Research Nurse Related Careers

- Agency Registered Nurse

- Clinic Registered Nurse

- Clinical Care Coordinator

- Clinical Educator

- Nurse Clinician

- Oncology Registered Nurse

- Pediatric Nurse

- Psychiatric Registered Nurse

- Registered Health Nurse

- Registered Nurse Charge Nurse

- Registered Nurse In Pacu

- Registered Nurse In The ICU

Clinical Research Nurse Related Jobs

- Agency Registered Nurse Employment

- Clinic Registered Nurse Employment

- Clinical Care Coordinator Employment

- Clinical Educator Employment

- Head Nurse Employment

- Nurse Employment

- Nurse Clinician Employment

- Oncology Registered Nurse Employment

- Pediatric Nurse Employment

- Psychiatric Registered Nurse Employment

- Registered Health Nurse Employment

- Registered Nurse Employment

- Registered Nurse Charge Nurse Employment

- Registered Nurse In Pacu Employment

- Registered Nurse In The ICU Employment

What Similar Roles Do

- Clinic Registered Nurse Responsibilities

- Clinical Care Coordinator Responsibilities

- Clinical Educator Responsibilities

- Head Nurse Responsibilities

- Nurse Responsibilities

- Nurse Clinician Responsibilities

- Oncology Registered Nurse Responsibilities

- Pediatric Nurse Responsibilities

- Psychiatric Registered Nurse Responsibilities

- Registered Health Nurse Responsibilities

- Registered Nurse Responsibilities

- Registered Nurse Charge Nurse Responsibilities

- Registered Nurse In Pacu Responsibilities

- Registered Nurse In The ICU Responsibilities

- Registered Nurse Med/Surg Responsibilities

- Zippia Careers

- Healthcare Practitioner and Technical Industry

- Clinical Research Nurse Jobs

- Clinical Research Nurse Work From Home Jobs

Browse healthcare practitioner and technical jobs

Can nurses work from home? Yes! These are your options

It’s one of the most frequently asked questions we get in comments to our posts and advertisements. Do you have work-from-home nursing jobs ? Does your site list telenursing positions for RNs, or any kind of telecommute jobs? Any remote nursing job opportunities?

We understand!

I can tell you one thing for sure — there’s no nursing company more sympathetic to this question than NurseRecruiter.com ! We all work remotely ourselves. Started doing it well before this cursed year and the pandemic it wrought. We’ve been doing it for years!

So we definitely understand the attraction. Live where you always wanted to live! Rid yourself of the practical obstacles that kept you from pursuing long-cherished dreams. Avoid dreary and expensive commutes. Work where — and when! — you feel most comfortable and least stressed. Take back control over your work-life balance! Put yourself at a healthy distance from workplace drama and executives second-guessing everything you do.

Remote working also opens up windows of opportunity for people who otherwise face challenging thresholds. When you can’t leave home for 12-hour shifts because you are raising a kid by yourself. When a disability makes working as floor nurse hard or impossible. When your age or health puts you at too high a risk in these pandemic times to accept a hospital job.

No less of a nurse

We don’t need to explain why interest in remote nursing jobs has surged this year. Hospital work was never harder than now; never as anxiety-inducing.

But even before Covid-19 ever reared its ugly head, there were stories we heard over and again. Being a bedside nurse can be exhausting. Floor nursing in understaffed teams is stressful and sometimes even literally back-breaking . Working in hospitals with high-acuity patients pays well, but takes a lot from you too. Nurses get burnt out.

In short, the whole industry needs change. But in the meantime, can anyone really blame you if you go looking for an alternative? If you genuinely love caring for people, but crave a different way to pursue your calling? You will be no less of a nurse working from home!

You’re going to need a plan!

The next question is: how realistic is it? Nurses aren’t office workers, after all, doing 9-to-5’s behind a computer all day. While white-collar workers stay at home to protect themselves, you’re out on the front lines. Essential workers. Because to be a nurse, you need to be by your patient, with your team. Right?

By and large, this is true. We have to be honest: most nursing still cannot be done from home. But don’t give up on your dream quite yet! Remote nursing jobs do exist, across a wide variety of settings. If anything, the Coronavirus pandemic has increased the need for telenursing , boosting demand for specific positions like phone triage nurses.

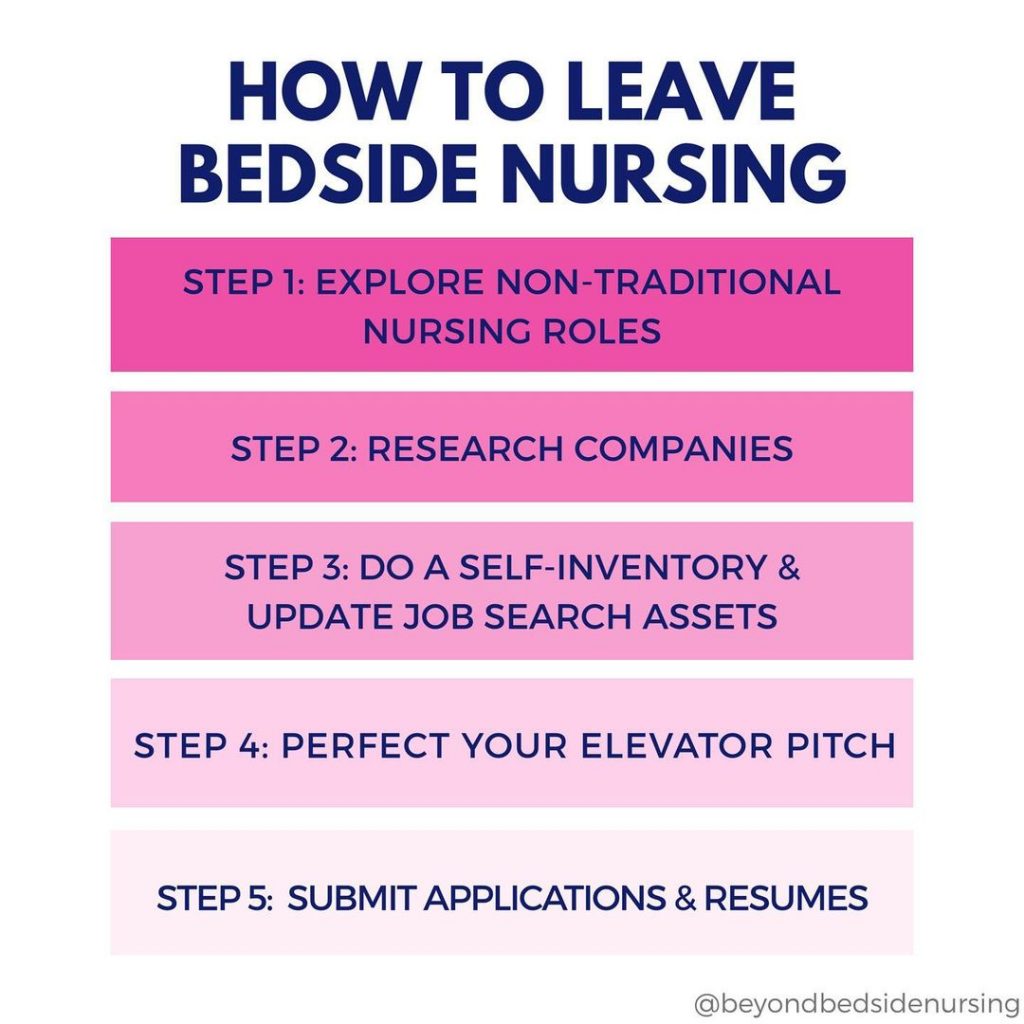

But you need a plan. Many work-from-home jobs in nursing involve specialties that are professions by themselves, like online nurse education, medical coding or billing, or case management . Qualifying for those might require investing time and resources in getting the right qualifications and experience. You might have to go back to school first. But the jobs are there!

Maybe you already have the right qualifications. And if you don’t, you just have to think of it in terms of a strategic plan — which steps do you need to undertake to get to your goal of qualifying for them?

Let’s look at a few examples, and use some of the great advice you yourselves have suggested in comments to our Facebook posts !

Telehealth nursing and telephone triage

Online nurse educator, case manager, care manager or patient advocate, medical coder or biller, utilization review nurse, health coach, health informatics nurse, research nurse, legal nurse consultant, nurse consultant in other fields, writing and business opportunities, the middle road: partly-remote alternatives to hospital bedside care.

Telehealth services are facing “a flood of patients in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic,” to the extent that providers are struggling to meet the demand . That means telehealth companies are ramping up their hiring of new staff!

There are different kinds of telenursing jobs , involving greater or lesser professional responsibility. They can be done from office locations or from home, depending on the job and employer. “I have friend who loves telenursing!,” Margie Kirchgesner Gehres wrote, explaining that “some nurses prefer to go to the office and answer phones” while others prefer the “solitude at home”.

Now medical facilities are even more overstretched than normal, and eager to minimize the infection risks of in-person visits, they are hiring more nurses to do telephone triage. Triage nurses can assess symptoms to decide whether an appointment is necessary. An experienced RN is perfectly qualified to tackle many of the every-day questions patients have, and a lot of those can be handled adequately by phone!

A call center nurse has fewer responsibilities. They don’t issue medical advice of any kind, they just make sure patients are connected through to the right person.

Many insurance companies and health systems provide a 24-hour nurse advice line. The advice nurses manning those lines help patients with non-emergency issues sort out what support they might need, understand their medications, find the care they need if they are away from home, and get a ‘sick slip’ if needed.

Most importantly, when people are anxious about any suspected medical issues, these nurses provide evidence-based healthcare advice. Infinitely more useful than having them just google their symptoms and inevitably ‘finding out’ it must be cancer..

And speaking for the nurses working in these jobs, dealing with these everyday issues, however important it is to address them early, does sometimes involve a more light-hearted note…

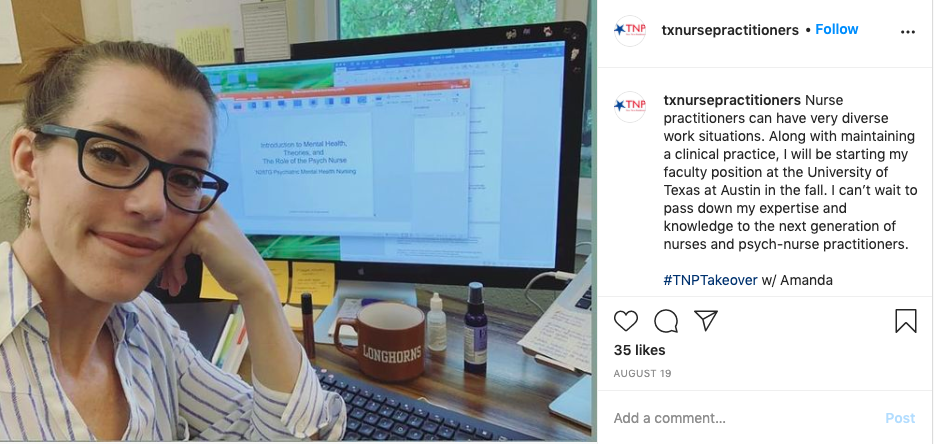

Our website regularly features jobs in nurse education . Until this year, few of them involved working from home. But for obvious reasons a lot of nursing education has now gone remote, and so have the jobs of nurse educators .

Even when all this is over, online teaching will likely occupy an ever more prominent role. Not just for nursing schools educating tomorrow’s nurses but also in continuing education, training experienced nurses advanced skills. All those online courses you see advertised? There are faculty jobs teaching them, designing courses and curricula, evaluating applications.

It’s a rewarding and important job, and one that has good prospects of providing long-term stability. The plan? To work in education, focus on pursuing your own, and get that Master’s degree in nurse education!

A related if rather specific job is to be a nurse exam writer , where you help to formulate appropriate questions for nursing certifications and exams (and we all know that some of those could be articulated more clearly!)

“ Case management and utilization management jobs are often work from home,” Heather Roets Meade said in our Facebook comments. And she’s right! (And we’ll get back to those utilization management jobs later on.)

Case managers (or case management nurses ) play a key role in navigating complex care for patients whose treatment involves multiple specialties — often older people with chronic health conditions. They scrupulously manage the communication between the physicians involved in their care as well as with the insurance company.

The case manager is both a coordinator and a go-between, helping them all to create the best care plan for the patient. But they keep a firm eye on the institutional needs, legal and financial ramifications involved. Their focus is also on preventing any non-compliance, minimizing the overutilization of services, and finding cost-effective solutions.

The jobs market for nurse case managers is growing rapidly. In hospice and home care centers for example, but with increasing space for remote work as well. Working from home, you’d be on the phone a lot, from helping patients with their doctor’s appointments to assisting the care providers in scheduling important surgeries.

Like many of the jobs in this list, entering this field is a lot easier with several years of experience as Registered Nurse. To complete your qualifications, there are four different ways to earn your certification in case management.

While case managers help the patient get a handle on the complicated care issues he or she faces, they still operate within the restrictions that are set by the hospital, insurance company, or other institution that employs them. What if you enjoy patient education and care coordination, but you want to be wholly on the side of the patient, with nobody’s interests but theirs in mind?

That’s where a care manager comes in. Their work can be especially important when someone faces a lifelong injury, a chronic disease, or the prospect of end-of-life care. The choices and pressures involved in understanding treatment options and grappling with insurance issues can be overwhelming. That’s all the more true for the elderly and their families, for whom an aging life care manager or geriatric care manager can be a godsend.

Nowadays, and of course especially in current circumstances, a significant part of this work is done remotely, by telephonic nurse care managers .

Care managers take a holistic approach, Lori Beth Charlton explains . They help their clients navigate the maze of health care and long-term care systems with a firm eye on what serves their overall quality of life best. And they don’t just look at their medical needs, but also at how those intersect with a client’s “social, emotional, financial, legal, and housing needs”.

Happy International Nurses Day! First picture 1990 first year student nurse, second picture 2020 working from home no makeup selfie. What a difference 30 years makes 🙎🏻♀️but still here, still nursing. #InternationalNursesDay2020 pic.twitter.com/nSJ6pKWmb5 — Corinne Miller (@corinnegmiller) May 12, 2020

Several of you mentioned medical coding and billing, which is a rapidly growing field as well, and again has the distinct advantage of steady and predictable hours! A lot of this work is done in offices, but there is an increasing number of remote jobs too. “I am an RN and went into coding eight years ago, work from home,” wrote Janice Larson.

The jobs involved, as medical biller or medical coder , are quite different from each other, and it’s mostly just in smaller businesses that the same person does both billing and coding. Billers and coders are both health claims specialists , but becoming a medical coder takes more study and experience (and pays better) — though one job is a great starting ground for the other!

Medical coders play a key role in the billing process — errors in assigning medical codes will lead to insurance companies being incorrectly billed, which can cause contested or rejected claims and serious headaches for patients and hospitals. But it can be genuinely tricky to translate notes and documentation from various sources about complex medical issues into unambiguous medical codes. A medical coder has to be able to understand and interpret medical documentation as well as insurance contract language in enough detail to provide a clinical opinion.

That’s why RNs have significant advantages applying to these jobs. But medical billers , too, benefit from a nurse’s real grasp of clinical care when it comes to getting the details of the billing forms right, especially in a complex field like home care. As medical biller, you gather insurance information from the patient, review billing records for Medicare and/or Medicaid claims, and collaborate with insurance companies when filing claims “to work out denials/rejections, finalize the details and send out statements”. You also operate as an intermediary, helping patients understand their charges and smoothing out stressful issues — so your bedside manner still matters!

Either line of work can involve a bit of detective work , “dissecting a patient’s medical record, tracking down additional information,” which is part of the charm. That goes for a medical review nurse too, whose job partly involves detecting potentially fraudulent or abusive billing practices.

It won’t come as surprise that you need to do specific courses to take on these jobs as well. Further education is key , from a specialized degree or certification to follow-up workshops. Especially if you want to get that job as remote medical coder , additional experience and training counts!

If you’ve been a RN for long enough, you may have your issues with insurance companies. Maybe not the first place you think of when wondering if the grass is greener on the other side! But there is a variety of job opportunities to be found there for nurses who seek alternatives to bedside nursing, with more regular working hours to boot. Not just for case managers, but for insurance claim specialists and utilization review nurses too.

A utilization review (UR) nurse assesses the severity of the medical problem, and whether it meets the criteria for full inpatient treatment or other levels of (eg outpatient) care. Hospitals and other healthcare providers need UR nurses for that same task. But when you work for an insurance company, you review claims to determine which kind of treatment is warranted, scrutinizing medical records and medical review criteria and guidelines to identify what procedures are covered and what amount needs to be paid out.

A significant amount of jobs in the context of case management at insurance companies involves disability claims and workers’ compensation cases. A nurse case reviewer or nurse consultant focused on workers’ compensation claims will review the documentation to make sure the claim meets all compliance standards.

If some of the above jobs sounded all too bureaucratic, becoming a health coach might be a good alternative! As bedside nurse, you care for the sick — that is why you chose the profession after all, right? But do you ever wonder about all the patients who might not have needed that hospital care, if they had gotten a little bit more help with preventative care earlier?

To put it in fancier words, “a key feature of U.S. health care” is the way it encourages “overuse of services by favoring procedural over cognitive tasks (e.g., surgery vs. behavior-change counseling) and specialty over primary care”. That’s how Farshad Fani Marvasti and Randall S. Stafford articulated it in a New England Journal of Medicine article titled “From “Sick Care” to Health Care” , where they argued that “a prevention model, focused on forestalling the development of disease before symptoms or life-threatening events occur, is the best solution”.

As health coach, you can be part of this solution. Instead of prescribing what someone should do, you mentor them into finding the right ways to do it, building “one-on-one relationships in order to make wellness plans and set health goals that will work for a specific person”.

The good news is that this is work that can also be done online from home, as remote health coach . “Lots of insurance companies want health coaches to work from home,” The Nerdy Nurse explained . So do other health and wellness companies and sites like WebMD. And with a bit of entrepreneurial spirit and a knack for networking, you can also work as independent, self-employed health coach!

A healthy lifestyle is more than a diet. It is an overall approach to life that involves moving the body each day, relaxation, quality time with friends+family and expressing 💙. #MyPhoto #IonianSea #lifestylemedicine #Health #Greece #HealthCoach pic.twitter.com/WrPtZ3Mh3e — Beth Frates MD (@BethFratesMD) August 6, 2020

Getting into health informatics as clinical informatics nurse or nursing informatics specialist is another great option if you want to pursue long-term work-from-home opportunities.

“I started being able to work partly from home in 2012 when I was an EHR Application Analyst,” The Informatics Nurse explained . “I was able do more productive work with the time saved from my long commute. Just as important, I could more easily spend time with my then-3-year-old daughter during breaks (and I wasn’t too tired to play with her by end of day). After that, I worked as a Project Consultant for a health system in the Midwest while still residing in California.”

Health informatics is a good field to choose if your drive as a nurse stems from a holistic passion to improve the care people receive, rather than the satisfaction of one-on-one patient contact. A lot of new technologies make our jobs as nurses ever easier, but if you’ve been a nurse for a while you also know that how some of them are applied in practice can be… bothersome. Why not be part of the solution yourself?

It’s your chance to show how innovative you can be! Use your practical nursing experience to consult on new technology applications, or to help build or evaluate data and information retrieval systems, for patient records for example.

Does that sound too abstract or ambitious? Informatics nurses also stay closer to day-to-day hospital life by helping employers introduce new electronic health records and medical charting systems, making sure they’re always updated, and educating nurses on how to use them.

That means you’ll first have to educate yourself, of course. The Nurse.org info sheet on nursing informatics notes that “some employers will hire tech-savvy BSN-prepared nurses for informaticist jobs,” but “there is an increasing demand for nurse informaticists to have a Master’s degree in Health Informatics or a related field”.

It might be worth it, though, as The Nerdy Nurse has pointed out: “the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects a 15% increase in demand for information technicians in nursing by the year 2024. Since this is a relatively new and high tech industry, nursing informatics are some of the highest-paid nurses.”

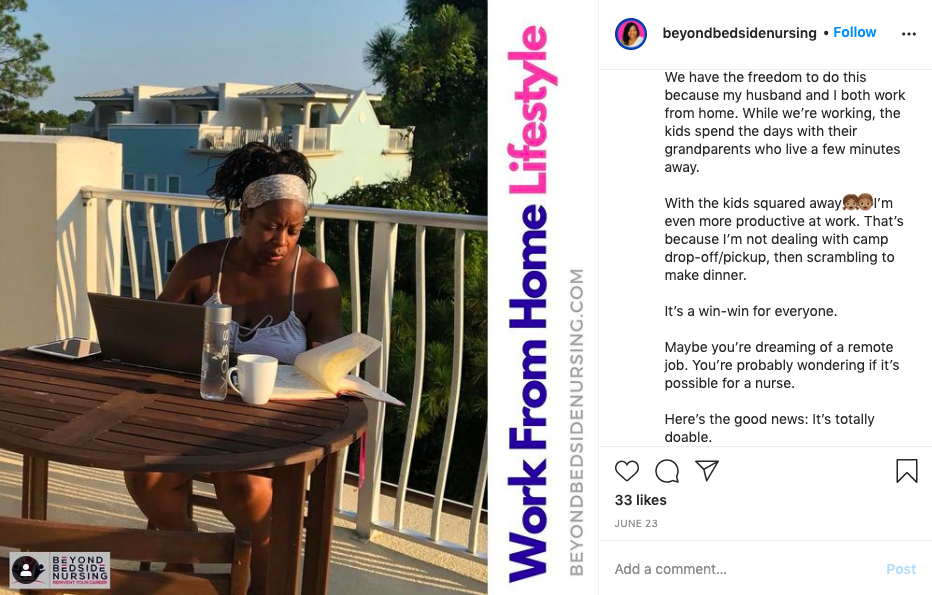

Being a clinical research nurse is another alternative that involves remote work opportunities, and even the office jobs involved get you home more often than hospital work! “I’m in research,” a nurse on Reddit’s Nursing forum explained, and “I’m home every evening for dinner, no call/weekends/nights, work from home when I’m not seeing patients, and I feel great, well rested, and happy”.

Writing data analysis manuscripts and study protocols is “fascinating and mentally stimulating” work, the nurse added. Because that’s the kind of work a clinical research associate does: whenever a new drug, treatment or medical device goes through clinical trials and testing, research nurses monitor the studies, analyzing and writing up their progress and findings. They ensure regulatory and study protocol compliance, make sure all important patient information is recorded correctly, and recruit and screen patients for clinical trials.

If bedside isn’t your cup of tea, just know there’s great jobs available out there. You just have to hunt and wait.

Peering over documents is as far removed from everyday hospital care as you can imagine, but that is kind of the point! As a fellow research nurse interjected, “I only go into the office 1-2 days a week… I am SO much less stressed these days, and I’m making more than I was in the ED.” Like they said, “if bedside isn’t your cup of tea, just know there’s great jobs available out there. You just have to hunt and wait.”

Alisia McIntyre had another suggestion. “Perhaps you can be a legal nurse consultant .” Not just is this another job that an experienced Registered Nurse can do from home as self-employed, independent contractor, legal nurse consulting is a handsomely paid specialty as well!

Take the legal department of an insurance company, for example. When they investigate a personal injury claim — or worse, a case that involves accusations of medical malpractice or wrongful death — they won’t be able to get by on their legal expertise alone. They will need advice from people with medical expertise and hands-on healthcare experience!

That’s where legal nurse consultants come in. They identify, interpret, organize and summarize the relevant medical records. They assess the damages and injuries being claimed and the costs of future care, review hospital policies, and interview clients, witnesses and experts. They search for relevant literature and make sure it’s reflected correctly, and screen incoming cases for merit. They review and summarize depositions, and even testify in court as expert witnesses themselves.

But it’s not just insurance companies that need them. There is work for legal nurse consultants in “law firms, government agencies,… patient safety organizations, business and industry legal departments, healthcare facilities and forensic laboratories” too! Your work might involve regulatory compliance, product liability, worker’s compensation, even criminal cases involving assault or abuse.

To become a legal nurse consultant (LNC), you first need to be a RN with extensive experience, and then work on your legal knowledge. Start with a nurse consulting training program and if possible, follow-up with an internship or by attending in legal seminars. To be the perfect candidate, enhance your reputation by getting certified as LNCC by the American Legal Nurse Consultant Certification Board. You can get your first job before working through all those steps, but as with many of these jobs that allow for working from home, the longer ahead you plan, the easier it is to realize your dream!

Not all nurse consultants are in the legal field! There are definitely other niche specialties for nurse consultants that are a world away from bedside nursing.

Companies which provide genetic testing, for example, employ genetics nurse consultants to communicate the test results to their customers in language they can understand. Businesses planning to launch new products aimed at nurses need an insider’s recommendations. Some occupational health nurses work as consultants.

There are creative nurse consultants too. One might even end up advising a film or documentary maker on how the profession is portrayed! And a lucky few who prefer to really delve into the details can find work as medical script nurses , making sure the medical plots devised by TV and film writers don’t stray too far from reality..

Have you seen @carolynjdocs documentary, @defining__hope it's "about eight patients with life-threatening illnesses weighing what matters most at the fragile junctures in life." worked as a nurse consultant on it. — Barbara Glickstein (@BGlickstein) January 12, 2019

If you are creative and have an eye for business opportunities, you could run a side hustle as nurse entrepreneur . If you’re successful enough, it might even become your next profession! We interviewed a former pediatric nurse, Melissa Gersin, who invented a baby-soothing mat and made that “Tranquilo Mat” her business !

If you are a skilled writer to boot and never short of ideas, being a nurse blogger nowadays is basically a subset of this category. Honestly, we are grateful for the old-school nurse blogs where people simply spend a few hours of their spare time to share moving, funny or interesting stories and practical advice and insights. But the best known bloggers these days are basically nursepreneurs in their own right , using their blog as gateway to more financially lucrative opportunities.

It’s definitely not the easy money it may seem at first blush — just sprinkling your posts with affiliate links won’t get you more than pocket money. If you look at the most famous nurse bloggers, they are excellent communicators in a broader sense, deploying their skill as writers to attract invitations as speakers and coaches , appearing at conferences, workshops and training sessions. Online, their blogs pull in curious readers, but it’s the more in-depth resources they provide — the training materials, educational videos or toolkits for nursing students — that bring in revenue.

As a nurse entrepreneur, when asked what I do, I say, “I am a self-employed registered nurse who spends her time speaking and writing. You might say I heal with words." ~Donna Cardillo #nurseentrepreneur #speaking #writing #healing #nurse #TheInspirationNurse #selfemployed pic.twitter.com/HZsBtdZCh3 — Donna Cardillo (@DonnaCardilloRN) March 20, 2019

Would you rather really just stick to writing? There’s no need to start your own blog to be a freelance nurse writer . Medical journals and magazines commission articles from writers with in-depth knowledge of medical terminology. You don’t necessarily have to start at that level either, though! Think of how many healthcare businesses are out there, how many nursing schools. They all have websites, and they all require new content every day!

Many home health jobs can’t be done from your own home, but there are advantages to visiting patients at their homes instead of working in a hospital — and some of the work has now moved at least partly online.

“It doesn’t require being on your feet all day,” wrote Gayle Colleen in our Facebook comments. “I do pediatric home care, you have one patient and get to sit some,” Shawna Tyo added, heartily endorsed by Alexia Carlson: ”That’s what I do. I love my job!”

A nurse in Reddit’s nursing community recounted his experience doing home medicare wellness visits . Doing those as a job already had numerous advantages over working in a hospital before, he argued, and now the switch to doing these check-ins virtually provides even more freedom. “I’ve never worked in a hospital and never have any desire too. I do telehealth and medicare annual wellness visits. I choose my own hours, .. wear literal pajamas and make $34 an hour. Prior to covid I did the same but visits at homes. In — do the assessment, get BP, temp, 02 sat — out. Get to meet folks, cats and dogs. No coworker drama. Lazy nurse? Maybe, but my back’s fine. I love my job and I got money in the bank.”

Remote nursing is in your grasp: plan for the future

In short, it’s not quite as simple as just checking a box in our search fields to say ‘only jobs from home’ — like all major life or career changes, switching to a remote nursing involves thinking through choices and achieving your plan step by step. Know your options, identify networking opportunities, ask questions. But if you find yourself unable to grapple with the challenges of bedside nursing anymore, there are definite possibilities to put your nursing expertise to good use in alternative careers!

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Let us know what you have to say:

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

24 comments

Zulyamn Yanira Ruiz-Ortiz

IM LABOR NURSE FOR 25 YEARS I HAVE IN JAN 2020 INJURY IN MY BACK.NECK AND RIGHT ARM. I CAN’T WORK IN MY SAME JOB BUT I CAN WORK FROM HOME BY COMPUTER.

Wanda Faye Pitts Brown

This article was extremely helpful. I am a handicapped nurse. I was injured in a car accident after I became a nurse. I tried a few other fields but have decided to try coding. I have taken the course and am preparing to be certified but I have no clue where to look for a job. I have not worked in 10 years. It took that long for me to recover from the accident. This article helped me decide what I should do next.

That is wonderful to hear — I’m glad we were able to help you determine your next move!

Cynthia Coutinho

I am a nurse of 35 years practice. I believe I have many qualifications that suit these positions. Do you have listing for job postings in these fields? Do you match jobs to applicants?

Dear Cynthia, NurseRecruiter.com is a specialized nursing jobs board where nurses can look for jobs and employers and recruiters can post new positions. So the process of matching jobs to applicants takes place online.

Nurses who are registered on our site can search for open positions that are specifically relevant to their experience, qualifications and area, and employers can reach out to nurses who are registered here when they think their skill sets match the open position. Well, if you are registered on the site already you may be familiar with the process!

We have to be honest: work-from-home positions are relatively rare among the job opportunities that are posted here. We tried to stress in the blog post that finding such positions should be treated as a matter of strategic planning — it’s unfortunately not as straightforward as finding an on-site position.

Still, especially recently, employers have been posting remote/WFH positions on our site a little more often. For example in the case management / utilization review category or, more rarely, in nursing education or telephone triage .

So while finding a remote position will take more than simply being registered here, it can be useful to check back in here regularly. On our side, we are studying the possibility of flagging remote/WFH positions specifically, to ease the process of finding them.

Akilah McRoy

I work for a school district (I have 6 schools ) Tk-high school. What I found during this time while there are no students in school is that the data entry for entering and updating student records is SEVERELY behind. Some data not entered for years (immunizations, care plans, vision and hearing results ect…). There has to be other districts with the same issue. Would love to have a job like this helping other schools.

Twana Phillips

Send me more info please.

I am so thankful for email…I am so burned out from working with organizations where the staff is running the business, no leadership, no support to help move forward, leaders that tell you, I did not sign on the deal with the issues of the department. I so want to work hard from home and make a difference.

Melinda Hamrick

I’m interested in learning more. I’ve been a nurse for 24 1/2 years.

I’ve been an LPN for over 25 years. Are any of these opportunities available for us? After doing this for so long and getting older, I have ailments of my own particularly my knees that are really starting to take a toll on me physically.

Here I am after 45 years of nursing….and I’m still not ready to retire completely….I want to work 1-2 days a week….and still be part of the healthcare system….crazy girl am I…

Sharon Barton

I am definitely interested!

Catherine Autry

I would love to work from home.

Diane Derry

I would be greatly interested in working from home. I have been looking for something full time with health benefits. Please keep me informed of the opportunities .

Are there any simple data entry type jobs at home for LPNs?

Beatrice Cimei

I am an LPN in Oklahoma I had a stroke that prevents me from driving so working from home would be what I need to do what job would I apply for?

Merredith Brawley

30 years in medicine, most of it in the OR. I tried a career other than OR and found poor training, extreme politics, cliques, and no time for the patients–only the command to move faster. Surely there is something where you can spend time doing nursing.

Angela Miller

I have experience in MS, tele, PT, OT, SLP, and am much interested in a remote work from home position! Ive been told one of my greatest assets is my compassion. I would love to hear about opportunities. I live near Cincy, OH

How to I apply for remote nursing job? I filled out the application but not see this option to choose.

I am Oncology Nurse and I have OSTOEOARTHRITIS and the right hip pain so severe that affects when I work for 8 hours standing. I like to work form home, nu I ahve no experiences those above mentioned carreer, I need help.

correction: my right hipe……. ” I have no experiences above mentioned career”

Nzeakor, Josephine Uchechukwu.

I love your explanations. They are quite comprehensible. I am a registered Nurse/Midwife of more than 25years of experience and also a health-educator. I’ll like to work from home as a Triage Nurse. That is on part time basis. Thank you.

Leslie Whitmarsh

I have Rheumatoid Arthritis and have had a couple really rough years learning my body does not handle the hours of office or hospital nursing. I am still so passionate about my profession and would like to work from home to be able to stay in my profession.

I am looking for RN utilization review work at home. I have been a nurse for over 40 years.. not quite ready to retire.. however need to be at home.. less stress. I have been in management my entire career. 33 years as Director of Neurosurgery in a hospital. Currently Director of nursing in LTC.. been there for 5 years. I am looking fo assistance in obtaining a remote job. I hold an MSN in nursing

Recent Posts

- This is where nurse wages are highest — and where your RN salary is worth the most!

- Get nurses to swipe right on your job: how to double your results

- When nurses strike — again! What can you expect when you go on strike? Or take a strike nursing job?

- What’s the best travel nursing destination in Pennsylvania, and why is it Pittsburgh?

- “It’s just crazy — every nurse takes the NCLEX, we should be able to work anywhere in the US and not pay extra”

- Newsletters

- Nurse Employers

- Nurse Marketing

- Nursing Jobs

- Nursing News

- Nursing Stories

- Per Diem Nursing

- Scholarship

- Sponsored Content

- Travel Nursing

- Department of Health and Human Services

- National Institutes of Health

Nursing at the NIH Clinical Center

Clinical research nurse roles.

Medical Support Assistant: The Medical Support Assistant (MSA) performs administrative duties to support the medical staff, nursing staff and patients, as well as other Clinical Center Departments and Institutes. They are responsible for coordinating and organizing patients' administrative and clerical information utilizing the hospital information systems. They facilitate patient visits, coordinate administrative work, and serve as the focal point for communications within the clinic/unit.

Program Support Assistant: The Program Support Assistant (PSA) provides direct administrative, procedural, and informational resource assistance and support to program staff and/or managers by organizing, collecting, analyzing, and presenting information related to the current and future program/project workload. Assists with the coordination of program workflow and the coordination of various duties assigned to program staff.

Program Specialist: The Program Specialist (PS) supports the administrative functions of the operations of the area assigned including financial management, procurement, quality assurance, management analysis and timekeeping. They participate with senior specialists in the coordination, preparation, and analysis of a wide variety of reports.

Staff Assistant: The Staff Assistant directs and implements administrative functions for the assigned office. Keeps the supervisor fully informed of current conditions throughout the department and takes appropriate action to ensure that administrative activities are properly implemented to support its mission. Maintains liaison and coordination between the department and other offices in the Clinical Center and the NIH. Establishes and implements standards for the efficient operation of the office and coordinates with other staff within the office and department, ensuring that administrative and clerical functions result in smooth operations.

Health Technician, Phlebotomist: The Health Technician Phlebotomist provides clinical care and supports biomedical research under the supervision of a licensed nurse. The incumbent supports a team that provides collection of blood and blood components from donors/patients by either collection of a unit of whole blood or blood components utilizing apheresis. The incumbent performs venipuncture on donors/patients within the Blood Services Section for allogeneic use or for in vitro studies carried out by the various Institutes at the NIH.

Health Technician, Surgical: Provides technical support and patient care support for both major and minor surgical procedures. These duties include assistance with positioning the patient and surgical prep. Patient care also involves the transport of patients to and from the surgical suite, as well as assisting staff during surgical procedures as directed.

Medical Instrument Technician (Surgical): The Medical Instrument Technician (Surgical) assists with surgeries under the supervision of surgeons, registered nurses, or other surgical personnel. They help set up the operating room, prepare and transport patients for surgery, adjust lights and equipment, pass instruments and other supplies to surgeons and surgeon's assistants, hold retractors, and help count sponges, needles, supplies, and instruments.

Patient Care Technician: The Patient Care Technician supports the activities of the professional nurse by independently providing patient care functions to assigned patients while maintaining a safe environment.

Behavioral Health Technician: The Behavioral Health Technician supports the activities of the professional nurse by independently providing patient care functions to assigned behavioral health patients while maintaining a safe and therapeutic environment.

Healthcare Simulator Technician: The Healthcare Simulator Technician assists the Simulation Program Coordinator/Nurse Coordinator by providing simulation operational expertise and clerical support for the NIH Clinical Center Simulation Program.

Diagnostic Radiologic Technologist (Interventional Radiology): The Diagnostic Radiologic Technologist in Interventional Radiology (IR) is trained in radiographic imaging guided procedures and has the professional skills/expertise required to integrate interventional procedures/exams into overall clinical management. This position is a key part of the IR team performing procedures/exams on patients and actively participates in the design, implementation and evaluation of new imaging methods and techniques utilized in this area.

Lead Diagnostic Radiology Technician: The Lead Diagnostic Radiology Technician functions as the team leader for the team of diagnostic radiology technicians performing interventional radiology services. As the team leader they utilize a variety of coordinating, coaching, facilitating, consensus-building, and planning techniques.

Program Manager for Sterile Processing Service: The Program Manager for the Sterile Processing Service manages the Sterile Processing Service which is the central point that all contaminated supplies, equipment, and materials are sent after use. It includes sterile and non-sterile storage, and centralized decontamination, high-level disinfection, and sterilization. It supplies equipment to the operating rooms, laboratories, inpatient areas and specialty clinics, and dispatch areas for distribution to approximately 60 supply issue points throughout the NIH Clinical Center complex.

Lead Medical Supply Technician (Sterile Processing): The Lead Medical Supply Technician for Sterile Processing functions as the team leader for the team of medical supply technicians (sterile processing) on an assigned shift and personally performs the work of medical supply technicians (sterile processing). As the team leader, they utilize a variety of coordinating, coaching, facilitating, consensus-building, and planning techniques.

Medical Supply Technicians (Sterile Processing): The Medical Supply Technician is responsible for the decontamination, packaging, sterilization, high level disinfection and distribution of medical/surgical instruments and equipment in the Clinical Center.

Clinical Research Nurse 1: The Clinical Research Nurse (CRN) 1 has a nursing degree from a professional nursing program approved by the legally designated state accrediting agency. The CRN 1 is a newly graduated registered nurse with one year or less of clinical nursing experience. The incumbent functions under the direction of an experienced nurse to provide patient care, while using professional judgment and sound decision making.

Clinical Research Nurse 2: The Clinical Research Nurse (CRN) 2 has a nursing degree or diploma from a professional nursing program approved by the legally designated state accrediting agency and has practiced nursing for at least one year. This nurse independently provides nursing care; identifies and communicates the impact of the research process on patient care; adjusts interventions based on findings; and reports issues/variances promptly to the research team. The CRN 2 administers research interventions; collects patient data according to protocol specifications; evaluates the patient response to therapy; and integrates evidence-based practice into nursing practice. The CRN 2 contributes to teams, workgroups and the nursing shared governance process. New skills and knowledge are acquired that are based on self-assessment, feedback from peers and supervisors, and changing clinical practice requirements.

Clinical Research Nurse 3: The Clinical Research Nurse (CRN) 3 has a nursing degree or diploma from a professional nursing program approved by the legally designated state accrediting agency at the time the program was completed by the applicant. The CRN 3 has practiced nursing for at least two years. The role spans the professional nursing development from “fully competent” to “expert” nursing practice. The CRN 3 provides care to acute and complex patient populations and utilizes appropriate professional judgment and critical decision making in planning and providing care. They master all nursing skills and associated technology for a particular Program of Care and assists in assessing the competency of less experienced nurses. The CRN 3 participates in the planning of new protocol implementation on the patient care unit; administers research interventions; collects patient data according to protocol specifications; evaluates the patient’ response to therapy; responds to variances in protocol implementation; reports variances to the research team; integrates evidence-based practice into nursing practice; and evaluates patient outcomes. The CRN 3 assumes the charge nurse and preceptor roles as assigned. Formal and informal feedback is provided by the CRN 3 to peers and colleagues in support of individual growth and improvement of the work environment.

Clinical Research Nurse 4: The Clinical Research Nurse (CRN) 4 has a nursing degree or diploma from a professional nursing program approved by the legally designated state accrediting agency at the time the program was completed by the applicant. The CRN 4 is a clinical expert and leader in all aspects of nursing practice. They demonstrate expertise in the nursing process; professional judgment and decision making; planning and providing nursing care; and knowledge of the biomedical research process. The CRN 4 utilizes basic leadership principles and has an ongoing process of questioning and evaluating nursing practice.

Supplemental Nurse/Float Pool/Per Diem: Supplemental Staff are Temporary Intermittent RN positions within the Nursing Department that are assigned to either a Central Pool or are Unit Based. Central Pool Supplemental staff work out of the Office of Staffing and Workforce Planning, select their schedule based on the available needs of the house and are assigned as needed to different units. Unit Based Supplemental staff are assigned to a unit and select their schedule to meet the unit’s needs. If not needed on the unit for their scheduled shift, they can be floated like any other member of the unit nursing staff. Float to all units as assigned within their competency skill set as needed.

Clinical Manager/Team Lead: The Clinical Manager (CM)/Team Lead is an experienced staff nurse who supports the Nurse Manager and other departmental leadership with operations and leadership of a patient care area(s). This position functions as a team leader and it utilizes a variety of coordinating, coaching, facilitating, consensus-building, and planning techniques to lead a team of Clinical Research Nurses and paraprofessionals. They provide patient care, as well as support protocol implementation, data collection and human subject protection.

Clinical Educator: The Clinical Educator (CE) is an experienced staff nurse who provides direct patient care and collaborates with the Nurse Manager and other departmental leadership to oversee educational needs of unit staff. The CE develops/coordinates/evaluates orientation for new unit staff, trains/mentor’s unit preceptors, serves as a liaison/resource for departmental/Clinical Center/professional educational opportunities, identifies educational needs, coordinates unit in-services, and plans unit educational days. The CE designs, implements and evaluates learning experiences for all staff levels to acquire, maintain, or increase their knowledge and competence. The Clinical Educator teaches at the unit and departmental level.

Safety & Quality Nurse: The Safety and Quality Nurse provides direct patient care and coordinates, oversees and evaluates the quality improvement and patient safety initiatives at the unit or program of care level. They collaborate with the nurse manager and department leaders on improvement activities related to promoting patient safety, clinical quality and reducing risk. They develop and maintains proficiency in effective use and interpretation of data to drive quality improvement activities on the unit or program of care level.

Program Director : The Program Director serves as the supervisor of a group of expert advisors for a specific area of nursing expertise (education, recruitment & outreach, safety & quality, staffing & workforce planning). The incumbent coordinates, implements, and oversees all the operations of the program they oversee. They serve as the liaison to other Clinical Center departments and the ICs for issues related area of expertise and assigned responsibility and to provide communication and consultative services to all credentialed nurses at the Clinical Center.

Nurse Manager : The Nurse Manager has 3 to 5 years of recent management experience; advanced preparation (Masters degree) is preferred. The Nurse Manager has experience in change management, creative leadership, and program development; an demonstrates strong communication and collaboration skills to foster an effective partnership with institute personnel. The Nurse Manager demonstrates a high level of knowledge in a particular specialty practice area and utilizes advanced leadership skills to meet organization goals.

Clinical Nurse Specialist : The Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) has a Masters or Doctorate Degree in Nursing from a state-approved school of nursing accredited by either the National League for Nursing Accrediting Commission (NLNAC) or the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (CCNE) with a major in the clinical nursing specialty to which the nurse is assigned. The CNS has a minimum of 5 years’ experience, is certified in a specialty area, and is accountable for a specific patient population within a specialized program of care.

Nurse Educators : The Nurse Educator plans, directs, executes, and evaluates a broad program of nursing professional and educational activities directed toward professional development of nursing and support staff. Designs, implements and evaluates learning experiences for all staff levels to acquire, maintain, or increase their knowledge and competence. Collaborates in the design and implementation of learning needs assessment tools for unit and specific programs of care.

Nurse Consultant: The Nurse Consultant serves as an expert advisor with responsibility for managing a broad array of administrative projects and providing clinical consultative support for a Clinical Center Nursing Department Service or program. The Nurse Consultant leads, or directs projects related to clinical research nursing, staffing, budgeting, policy, safety, and human resources.

Nurse Scientist: The Nurse Scientist is a nurse with advanced preparation (PhD or doctorate in nursing or related field) in research principles and methodology, who also has expert content knowledge in a specific clinical area. The primary focus of the role is to (1) provide leadership in the development, coordination and management of clinical research studies; (2) provide mentorship for nurses in research; (3) lead evaluation activities that improve outcomes for patients participating in research studies at the Clinical Center; and (4) contribute to the overall health sciences literature. The incumbent is expected to develop a portfolio of independent research that provides the vehicle for achieving these primary objectives.

NOTE: PDF documents require the free Adobe Reader .

This page last updated on 05/24/2024

You are now leaving the NIH Clinical Center website.

This external link is provided for your convenience to offer additional information. The NIH Clinical Center is not responsible for the availability, content or accuracy of this external site.

The NIH Clinical Center does not endorse, authorize or guarantee the sponsors, information, products or services described or offered at this external site. You will be subject to the destination site’s privacy policy if you follow this link.

More information about the NIH Clinical Center Privacy and Disclaimer policy is available at https://www.cc.nih.gov/disclaimers.html

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Research Initiatives

- Meet Our Researchers

- Meet Our Program Officers

- RESEARCH LENSES

- Health Equity

- Social Determinants of Health

- Population and Community Health

- Prevention and Health Promotion

- Systems and Models of Care

- Funding Opportunities

- Small Business Funding

- Grant Applicant Resources

- Training Grants

- Featured Research

- Strategic Plan

- Budget and Legislation

- Connect With Us

- Jobs at NINR

Advancing health equity into the future.

NINR's mission is to lead nursing research to solve pressing health challenges and inform practice and policy – optimizing health and advancing health equity into the future.

Funding Opportunities Newsletter

Subscribe to receive the latest funding opportunities and updates from NINR.

Funding opportunities that improve health outcomes

NINR believes that nursing research is the key to unlocking the power and potential of nursing. NINR offers grants to individuals at all points in their career, from early investigators to established scientists. NINR grants also support small businesses and research centers.

Research Funding

Small Business

Training Funding

Homepage events stories, addressing public health challenges through research.

NINR-supported researchers explore and address some of the most important challenges affecting the health of the American people. Learn about accomplishments from the community of NINR-supported scientists across the United States.

Advancing social determinants of health research at NIH

Over 20 NIH Institutes, Centers, and Offices are working collaboratively to accelerate NIH-wide SDOH research across diseases and conditions, populations, stages of the life course, and SDOH domains.

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Infection Prevention and Long-term Care Facility Residents

- Nursing Home Infection Preventionist Training

- PPE in Nursing Homes

- Respiratory Virus Toolkit

- Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs)

- The resources on this page can keep you and your loved ones safe.

Long-term care facilities provide many services, both medical and personal care, to people who are unable to live without help.

If you live in a nursing home, assisted living facility or other long-term care facility, you have a higher risk of getting an infection. There are steps you can take to reduce your risk:

- Tell your healthcare provider if you think you have an infection or if your infection is getting worse.

- Take antibiotics exactly as prescribed and tell your healthcare provider if you have any side effects, such as diarrhea.

- Keep your hands clean. Remind staff and visitors to keep their hands clean.

- Get vaccinated against flu and other infections to avoid complications.

Resources for staying safe in long-term care facilities

About C. diff

About Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales

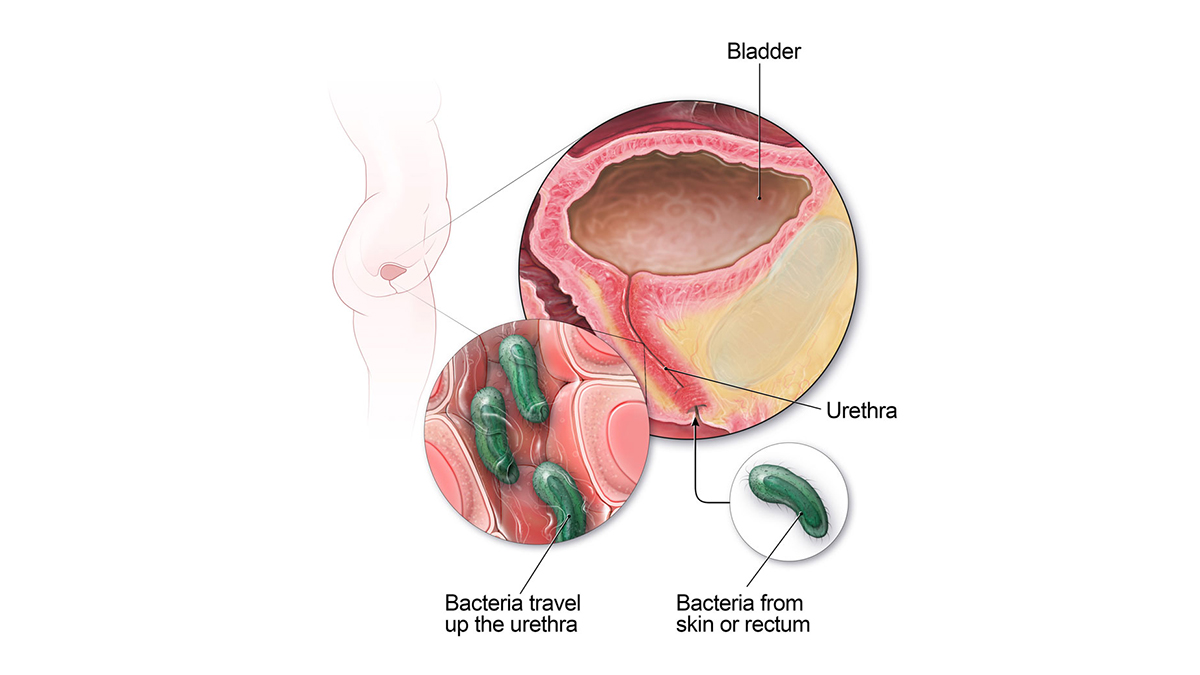

Catheter-associated Urinary Tract Infection Basics

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Basics

Healthy Habits: Antibiotic Do's and Don'ts

About Sepsis

About Norovirus

Resources for family members and caregivers

- Medicare resources for long-term care residents and caregivers.

- Find a nursing home in your area .

This website provides resources for patients, families and caregivers on the prevention of infections in nursing homes and assisted living facilities.

For Everyone

Health care providers.

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

CMS Newsroom

Search cms.gov.

- Physician Fee Schedule

- Local Coverage Determination

- Medically Unlikely Edits

Home - Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

What are you looking for today, search results.

Inflation Reduction Act

Medicaid renewals, innovation center, no surprise billing.

- Nursing home resources

This law helps save money for people with Medicare, improves access to affordable treatments, and strengthens the Medicare program.

As states resume normal operations, we’re working to make sure people stay covered.

We support the development and testing of innovative health care payment and service delivery models.

See how new rules help protect people from surprise medical bills and remove consumers from payment disputes between a provider or health care facility and their health plan.

Nursing Home Resources

Get the latest policy information and learn about initiatives to enable safe and quality care in nursing homes.

Strategic Plan Overview

CMS serves the public as a trusted partner and steward, dedicated to advancing health equity, expanding coverage, and improving health outcomes.

Advance Equity

Advance health equity by addressing the health disparities that underlie our health system

Expand Access

Build on the Affordable Care Act and expand access to quality, affordable health coverage and care

Engage Partners

Engage our partners and the communities we serve throughout the policymaking and implementation process

Drive Innovation

Drive Innovation to tackle our health system challenges and promote value-based, person-centered care.

Protect Program

Protect our programs' sustainability for future generations by serving as a responsible steward of public funds

Foster Excellence

Foster a positive and inclusive workplace and workforce, and promote excellence in all aspects of CMS's operations

Top resources

Medicare fee schedules.

Check the fee schedules to find billing codes.

- Physician fee schedule lookup tool

- Physician fee schedule

- Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule

- Durable Medical Equipment Fee Schedule

- Ambulatory Surgical Center (ASC) Payment

Codes for claim reimbursement

Find codes to be reimbursed for clinical services.

- Medicare Coverage Database