Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a thesis statement + examples

What is a thesis statement?

Is a thesis statement a question, how do you write a good thesis statement, how do i know if my thesis statement is good, examples of thesis statements, helpful resources on how to write a thesis statement, frequently asked questions about writing a thesis statement, related articles.

A thesis statement is the main argument of your paper or thesis.

The thesis statement is one of the most important elements of any piece of academic writing . It is a brief statement of your paper’s main argument. Essentially, you are stating what you will be writing about.

You can see your thesis statement as an answer to a question. While it also contains the question, it should really give an answer to the question with new information and not just restate or reiterate it.

Your thesis statement is part of your introduction. Learn more about how to write a good thesis introduction in our introduction guide .

A thesis statement is not a question. A statement must be arguable and provable through evidence and analysis. While your thesis might stem from a research question, it should be in the form of a statement.

Tip: A thesis statement is typically 1-2 sentences. For a longer project like a thesis, the statement may be several sentences or a paragraph.

A good thesis statement needs to do the following:

- Condense the main idea of your thesis into one or two sentences.

- Answer your project’s main research question.

- Clearly state your position in relation to the topic .

- Make an argument that requires support or evidence.

Once you have written down a thesis statement, check if it fulfills the following criteria:

- Your statement needs to be provable by evidence. As an argument, a thesis statement needs to be debatable.

- Your statement needs to be precise. Do not give away too much information in the thesis statement and do not load it with unnecessary information.

- Your statement cannot say that one solution is simply right or simply wrong as a matter of fact. You should draw upon verified facts to persuade the reader of your solution, but you cannot just declare something as right or wrong.

As previously mentioned, your thesis statement should answer a question.

If the question is:

What do you think the City of New York should do to reduce traffic congestion?

A good thesis statement restates the question and answers it:

In this paper, I will argue that the City of New York should focus on providing exclusive lanes for public transport and adaptive traffic signals to reduce traffic congestion by the year 2035.

Here is another example. If the question is:

How can we end poverty?

A good thesis statement should give more than one solution to the problem in question:

In this paper, I will argue that introducing universal basic income can help reduce poverty and positively impact the way we work.

- The Writing Center of the University of North Carolina has a list of questions to ask to see if your thesis is strong .

A thesis statement is part of the introduction of your paper. It is usually found in the first or second paragraph to let the reader know your research purpose from the beginning.

In general, a thesis statement should have one or two sentences. But the length really depends on the overall length of your project. Take a look at our guide about the length of thesis statements for more insight on this topic.

Here is a list of Thesis Statement Examples that will help you understand better how to write them.

Every good essay should include a thesis statement as part of its introduction, no matter the academic level. Of course, if you are a high school student you are not expected to have the same type of thesis as a PhD student.

Here is a great YouTube tutorial showing How To Write An Essay: Thesis Statements .

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Thesis Statements

Basics of thesis statements.

The thesis statement is the brief articulation of your paper's central argument and purpose. You might hear it referred to as simply a "thesis." Every scholarly paper should have a thesis statement, and strong thesis statements are concise, specific, and arguable. Concise means the thesis is short: perhaps one or two sentences for a shorter paper. Specific means the thesis deals with a narrow and focused topic, appropriate to the paper's length. Arguable means that a scholar in your field could disagree (or perhaps already has!).

Strong thesis statements address specific intellectual questions, have clear positions, and use a structure that reflects the overall structure of the paper. Read on to learn more about constructing a strong thesis statement.

Being Specific

This thesis statement has no specific argument:

Needs Improvement: In this essay, I will examine two scholarly articles to find similarities and differences.

This statement is concise, but it is neither specific nor arguable—a reader might wonder, "Which scholarly articles? What is the topic of this paper? What field is the author writing in?" Additionally, the purpose of the paper—to "examine…to find similarities and differences" is not of a scholarly level. Identifying similarities and differences is a good first step, but strong academic argument goes further, analyzing what those similarities and differences might mean or imply.

Better: In this essay, I will argue that Bowler's (2003) autocratic management style, when coupled with Smith's (2007) theory of social cognition, can reduce the expenses associated with employee turnover.

The new revision here is still concise, as well as specific and arguable. We can see that it is specific because the writer is mentioning (a) concrete ideas and (b) exact authors. We can also gather the field (business) and the topic (management and employee turnover). The statement is arguable because the student goes beyond merely comparing; he or she draws conclusions from that comparison ("can reduce the expenses associated with employee turnover").

Making a Unique Argument

This thesis draft repeats the language of the writing prompt without making a unique argument:

Needs Improvement: The purpose of this essay is to monitor, assess, and evaluate an educational program for its strengths and weaknesses. Then, I will provide suggestions for improvement.

You can see here that the student has simply stated the paper's assignment, without articulating specifically how he or she will address it. The student can correct this error simply by phrasing the thesis statement as a specific answer to the assignment prompt.

Better: Through a series of student interviews, I found that Kennedy High School's antibullying program was ineffective. In order to address issues of conflict between students, I argue that Kennedy High School should embrace policies outlined by the California Department of Education (2010).

Words like "ineffective" and "argue" show here that the student has clearly thought through the assignment and analyzed the material; he or she is putting forth a specific and debatable position. The concrete information ("student interviews," "antibullying") further prepares the reader for the body of the paper and demonstrates how the student has addressed the assignment prompt without just restating that language.

Creating a Debate

This thesis statement includes only obvious fact or plot summary instead of argument:

Needs Improvement: Leadership is an important quality in nurse educators.

A good strategy to determine if your thesis statement is too broad (and therefore, not arguable) is to ask yourself, "Would a scholar in my field disagree with this point?" Here, we can see easily that no scholar is likely to argue that leadership is an unimportant quality in nurse educators. The student needs to come up with a more arguable claim, and probably a narrower one; remember that a short paper needs a more focused topic than a dissertation.

Better: Roderick's (2009) theory of participatory leadership is particularly appropriate to nurse educators working within the emergency medicine field, where students benefit most from collegial and kinesthetic learning.

Here, the student has identified a particular type of leadership ("participatory leadership"), narrowing the topic, and has made an arguable claim (this type of leadership is "appropriate" to a specific type of nurse educator). Conceivably, a scholar in the nursing field might disagree with this approach. The student's paper can now proceed, providing specific pieces of evidence to support the arguable central claim.

Choosing the Right Words

This thesis statement uses large or scholarly-sounding words that have no real substance:

Needs Improvement: Scholars should work to seize metacognitive outcomes by harnessing discipline-based networks to empower collaborative infrastructures.

There are many words in this sentence that may be buzzwords in the student's field or key terms taken from other texts, but together they do not communicate a clear, specific meaning. Sometimes students think scholarly writing means constructing complex sentences using special language, but actually it's usually a stronger choice to write clear, simple sentences. When in doubt, remember that your ideas should be complex, not your sentence structure.

Better: Ecologists should work to educate the U.S. public on conservation methods by making use of local and national green organizations to create a widespread communication plan.

Notice in the revision that the field is now clear (ecology), and the language has been made much more field-specific ("conservation methods," "green organizations"), so the reader is able to see concretely the ideas the student is communicating.

Leaving Room for Discussion

This thesis statement is not capable of development or advancement in the paper:

Needs Improvement: There are always alternatives to illegal drug use.

This sample thesis statement makes a claim, but it is not a claim that will sustain extended discussion. This claim is the type of claim that might be appropriate for the conclusion of a paper, but in the beginning of the paper, the student is left with nowhere to go. What further points can be made? If there are "always alternatives" to the problem the student is identifying, then why bother developing a paper around that claim? Ideally, a thesis statement should be complex enough to explore over the length of the entire paper.

Better: The most effective treatment plan for methamphetamine addiction may be a combination of pharmacological and cognitive therapy, as argued by Baker (2008), Smith (2009), and Xavier (2011).

In the revised thesis, you can see the student make a specific, debatable claim that has the potential to generate several pages' worth of discussion. When drafting a thesis statement, think about the questions your thesis statement will generate: What follow-up inquiries might a reader have? In the first example, there are almost no additional questions implied, but the revised example allows for a good deal more exploration.

Thesis Mad Libs

If you are having trouble getting started, try using the models below to generate a rough model of a thesis statement! These models are intended for drafting purposes only and should not appear in your final work.

- In this essay, I argue ____, using ______ to assert _____.

- While scholars have often argued ______, I argue______, because_______.

- Through an analysis of ______, I argue ______, which is important because_______.

Words to Avoid and to Embrace

When drafting your thesis statement, avoid words like explore, investigate, learn, compile, summarize , and explain to describe the main purpose of your paper. These words imply a paper that summarizes or "reports," rather than synthesizing and analyzing.

Instead of the terms above, try words like argue, critique, question , and interrogate . These more analytical words may help you begin strongly, by articulating a specific, critical, scholarly position.

Read Kayla's blog post for tips on taking a stand in a well-crafted thesis statement.

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Introductions

- Next Page: Conclusions

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Think of yourself as a member of a jury, listening to a lawyer who is presenting an opening argument. You'll want to know very soon whether the lawyer believes the accused to be guilty or not guilty, and how the lawyer plans to convince you. Readers of academic essays are like jury members: before they have read too far, they want to know what the essay argues as well as how the writer plans to make the argument. After reading your thesis statement, the reader should think, "This essay is going to try to convince me of something. I'm not convinced yet, but I'm interested to see how I might be."

An effective thesis cannot be answered with a simple "yes" or "no." A thesis is not a topic; nor is it a fact; nor is it an opinion. "Reasons for the fall of communism" is a topic. "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" is a fact known by educated people. "The fall of communism is the best thing that ever happened in Europe" is an opinion. (Superlatives like "the best" almost always lead to trouble. It's impossible to weigh every "thing" that ever happened in Europe. And what about the fall of Hitler? Couldn't that be "the best thing"?)

A good thesis has two parts. It should tell what you plan to argue, and it should "telegraph" how you plan to argue—that is, what particular support for your claim is going where in your essay.

Steps in Constructing a Thesis

First, analyze your primary sources. Look for tension, interest, ambiguity, controversy, and/or complication. Does the author contradict himself or herself? Is a point made and later reversed? What are the deeper implications of the author's argument? Figuring out the why to one or more of these questions, or to related questions, will put you on the path to developing a working thesis. (Without the why, you probably have only come up with an observation—that there are, for instance, many different metaphors in such-and-such a poem—which is not a thesis.)

Once you have a working thesis, write it down. There is nothing as frustrating as hitting on a great idea for a thesis, then forgetting it when you lose concentration. And by writing down your thesis you will be forced to think of it clearly, logically, and concisely. You probably will not be able to write out a final-draft version of your thesis the first time you try, but you'll get yourself on the right track by writing down what you have.

Keep your thesis prominent in your introduction. A good, standard place for your thesis statement is at the end of an introductory paragraph, especially in shorter (5-15 page) essays. Readers are used to finding theses there, so they automatically pay more attention when they read the last sentence of your introduction. Although this is not required in all academic essays, it is a good rule of thumb.

Anticipate the counterarguments. Once you have a working thesis, you should think about what might be said against it. This will help you to refine your thesis, and it will also make you think of the arguments that you'll need to refute later on in your essay. (Every argument has a counterargument. If yours doesn't, then it's not an argument—it may be a fact, or an opinion, but it is not an argument.)

This statement is on its way to being a thesis. However, it is too easy to imagine possible counterarguments. For example, a political observer might believe that Dukakis lost because he suffered from a "soft-on-crime" image. If you complicate your thesis by anticipating the counterargument, you'll strengthen your argument, as shown in the sentence below.

Some Caveats and Some Examples

A thesis is never a question. Readers of academic essays expect to have questions discussed, explored, or even answered. A question ("Why did communism collapse in Eastern Europe?") is not an argument, and without an argument, a thesis is dead in the water.

A thesis is never a list. "For political, economic, social and cultural reasons, communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" does a good job of "telegraphing" the reader what to expect in the essay—a section about political reasons, a section about economic reasons, a section about social reasons, and a section about cultural reasons. However, political, economic, social and cultural reasons are pretty much the only possible reasons why communism could collapse. This sentence lacks tension and doesn't advance an argument. Everyone knows that politics, economics, and culture are important.

A thesis should never be vague, combative or confrontational. An ineffective thesis would be, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because communism is evil." This is hard to argue (evil from whose perspective? what does evil mean?) and it is likely to mark you as moralistic and judgmental rather than rational and thorough. It also may spark a defensive reaction from readers sympathetic to communism. If readers strongly disagree with you right off the bat, they may stop reading.

An effective thesis has a definable, arguable claim. "While cultural forces contributed to the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, the disintegration of economies played the key role in driving its decline" is an effective thesis sentence that "telegraphs," so that the reader expects the essay to have a section about cultural forces and another about the disintegration of economies. This thesis makes a definite, arguable claim: that the disintegration of economies played a more important role than cultural forces in defeating communism in Eastern Europe. The reader would react to this statement by thinking, "Perhaps what the author says is true, but I am not convinced. I want to read further to see how the author argues this claim."

A thesis should be as clear and specific as possible. Avoid overused, general terms and abstractions. For example, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because of the ruling elite's inability to address the economic concerns of the people" is more powerful than "Communism collapsed due to societal discontent."

Copyright 1999, Maxine Rodburg and The Tutors of the Writing Center at Harvard University

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- Mission, Vision, and Inclusive Language Statement

- Locations & Hours

- Undergraduate Employment

- Graduate Employment

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Newsletter Archive

- Support WTS

- Schedule an Appointment

- Online Tutoring

- Before your Appointment

- WTS Policies

- Group Tutoring

- Students Referred by Instructors

- Paid External Editing Services

- Writing Guides

- Scholarly Write-in

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Journal Article Writing Groups

- Early Career Graduate Student Writing Workshop

- Workshops for Graduate Students

- Teaching Resources

- Syllabus Information

- Course-specific Tutoring

- Nominate a Peer Tutor

- Tutoring Feedback

- Schedule Appointment

- Campus Writing Program

Writing Tutorial Services

How to write a thesis statement, what is a thesis statement.

Almost all of us—even if we don’t do it consciously—look early in an essay for a one- or two-sentence condensation of the argument or analysis that is to follow. We refer to that condensation as a thesis statement.

Why Should Your Essay Contain a Thesis Statement?

- to test your ideas by distilling them into a sentence or two

- to better organize and develop your argument

- to provide your reader with a “guide” to your argument

In general, your thesis statement will accomplish these goals if you think of the thesis as the answer to the question your paper explores.

How Can You Write a Good Thesis Statement?

Here are some helpful hints to get you started. You can either scroll down or select a link to a specific topic.

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is not Assigned How to Tell a Strong Thesis Statement from a Weak One

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned

Almost all assignments, no matter how complicated, can be reduced to a single question. Your first step, then, is to distill the assignment into a specific question. For example, if your assignment is, “Write a report to the local school board explaining the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class,” turn the request into a question like, “What are the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class?” After you’ve chosen the question your essay will answer, compose one or two complete sentences answering that question.

Q: “What are the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class?” A: “The potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class are . . .”

A: “Using computers in a fourth-grade class promises to improve . . .”

The answer to the question is the thesis statement for the essay.

[ Back to top ]

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is not Assigned

Even if your assignment doesn’t ask a specific question, your thesis statement still needs to answer a question about the issue you’d like to explore. In this situation, your job is to figure out what question you’d like to write about.

A good thesis statement will usually include the following four attributes:

- take on a subject upon which reasonable people could disagree

- deal with a subject that can be adequately treated given the nature of the assignment

- express one main idea

- assert your conclusions about a subject

Let’s see how to generate a thesis statement for a social policy paper.

Brainstorm the topic . Let’s say that your class focuses upon the problems posed by changes in the dietary habits of Americans. You find that you are interested in the amount of sugar Americans consume.

You start out with a thesis statement like this:

Sugar consumption.

This fragment isn’t a thesis statement. Instead, it simply indicates a general subject. Furthermore, your reader doesn’t know what you want to say about sugar consumption.

Narrow the topic . Your readings about the topic, however, have led you to the conclusion that elementary school children are consuming far more sugar than is healthy.

You change your thesis to look like this:

Reducing sugar consumption by elementary school children.

This fragment not only announces your subject, but it focuses on one segment of the population: elementary school children. Furthermore, it raises a subject upon which reasonable people could disagree, because while most people might agree that children consume more sugar than they used to, not everyone would agree on what should be done or who should do it. You should note that this fragment is not a thesis statement because your reader doesn’t know your conclusions on the topic.

Take a position on the topic. After reflecting on the topic a little while longer, you decide that what you really want to say about this topic is that something should be done to reduce the amount of sugar these children consume.

You revise your thesis statement to look like this:

More attention should be paid to the food and beverage choices available to elementary school children.

This statement asserts your position, but the terms more attention and food and beverage choices are vague.

Use specific language . You decide to explain what you mean about food and beverage choices , so you write:

Experts estimate that half of elementary school children consume nine times the recommended daily allowance of sugar.

This statement is specific, but it isn’t a thesis. It merely reports a statistic instead of making an assertion.

Make an assertion based on clearly stated support. You finally revise your thesis statement one more time to look like this:

Because half of all American elementary school children consume nine times the recommended daily allowance of sugar, schools should be required to replace the beverages in soda machines with healthy alternatives.

Notice how the thesis answers the question, “What should be done to reduce sugar consumption by children, and who should do it?” When you started thinking about the paper, you may not have had a specific question in mind, but as you became more involved in the topic, your ideas became more specific. Your thesis changed to reflect your new insights.

How to Tell a Strong Thesis Statement from a Weak One

1. a strong thesis statement takes some sort of stand..

Remember that your thesis needs to show your conclusions about a subject. For example, if you are writing a paper for a class on fitness, you might be asked to choose a popular weight-loss product to evaluate. Here are two thesis statements:

There are some negative and positive aspects to the Banana Herb Tea Supplement.

This is a weak thesis statement. First, it fails to take a stand. Second, the phrase negative and positive aspects is vague.

Because Banana Herb Tea Supplement promotes rapid weight loss that results in the loss of muscle and lean body mass, it poses a potential danger to customers.

This is a strong thesis because it takes a stand, and because it's specific.

2. A strong thesis statement justifies discussion.

Your thesis should indicate the point of the discussion. If your assignment is to write a paper on kinship systems, using your own family as an example, you might come up with either of these two thesis statements:

My family is an extended family.

This is a weak thesis because it merely states an observation. Your reader won’t be able to tell the point of the statement, and will probably stop reading.

While most American families would view consanguineal marriage as a threat to the nuclear family structure, many Iranian families, like my own, believe that these marriages help reinforce kinship ties in an extended family.

This is a strong thesis because it shows how your experience contradicts a widely-accepted view. A good strategy for creating a strong thesis is to show that the topic is controversial. Readers will be interested in reading the rest of the essay to see how you support your point.

3. A strong thesis statement expresses one main idea.

Readers need to be able to see that your paper has one main point. If your thesis statement expresses more than one idea, then you might confuse your readers about the subject of your paper. For example:

Companies need to exploit the marketing potential of the Internet, and Web pages can provide both advertising and customer support.

This is a weak thesis statement because the reader can’t decide whether the paper is about marketing on the Internet or Web pages. To revise the thesis, the relationship between the two ideas needs to become more clear. One way to revise the thesis would be to write:

Because the Internet is filled with tremendous marketing potential, companies should exploit this potential by using Web pages that offer both advertising and customer support.

This is a strong thesis because it shows that the two ideas are related. Hint: a great many clear and engaging thesis statements contain words like because , since , so , although , unless , and however .

4. A strong thesis statement is specific.

A thesis statement should show exactly what your paper will be about, and will help you keep your paper to a manageable topic. For example, if you're writing a seven-to-ten page paper on hunger, you might say:

World hunger has many causes and effects.

This is a weak thesis statement for two major reasons. First, world hunger can’t be discussed thoroughly in seven to ten pages. Second, many causes and effects is vague. You should be able to identify specific causes and effects. A revised thesis might look like this:

Hunger persists in Glandelinia because jobs are scarce and farming in the infertile soil is rarely profitable.

This is a strong thesis statement because it narrows the subject to a more specific and manageable topic, and it also identifies the specific causes for the existence of hunger.

Produced by Writing Tutorial Services, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

Writing Tutorial Services social media channels

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write a Strong Thesis Statement: 4 Steps + Examples

What’s Covered:

What is the purpose of a thesis statement, writing a good thesis statement: 4 steps, common pitfalls to avoid, where to get your essay edited for free.

When you set out to write an essay, there has to be some kind of point to it, right? Otherwise, your essay would just be a big jumble of word salad that makes absolutely no sense. An essay needs a central point that ties into everything else. That main point is called a thesis statement, and it’s the core of any essay or research paper.

You may hear about Master degree candidates writing a thesis, and that is an entire paper–not to be confused with the thesis statement, which is typically one sentence that contains your paper’s focus.

Read on to learn more about thesis statements and how to write them. We’ve also included some solid examples for you to reference.

Typically the last sentence of your introductory paragraph, the thesis statement serves as the roadmap for your essay. When your reader gets to the thesis statement, they should have a clear outline of your main point, as well as the information you’ll be presenting in order to either prove or support your point.

The thesis statement should not be confused for a topic sentence , which is the first sentence of every paragraph in your essay. If you need help writing topic sentences, numerous resources are available. Topic sentences should go along with your thesis statement, though.

Since the thesis statement is the most important sentence of your entire essay or paper, it’s imperative that you get this part right. Otherwise, your paper will not have a good flow and will seem disjointed. That’s why it’s vital not to rush through developing one. It’s a methodical process with steps that you need to follow in order to create the best thesis statement possible.

Step 1: Decide what kind of paper you’re writing

When you’re assigned an essay, there are several different types you may get. Argumentative essays are designed to get the reader to agree with you on a topic. Informative or expository essays present information to the reader. Analytical essays offer up a point and then expand on it by analyzing relevant information. Thesis statements can look and sound different based on the type of paper you’re writing. For example:

- Argumentative: The United States needs a viable third political party to decrease bipartisanship, increase options, and help reduce corruption in government.

- Informative: The Libertarian party has thrown off elections before by gaining enough support in states to get on the ballot and by taking away crucial votes from candidates.

- Analytical: An analysis of past presidential elections shows that while third party votes may have been the minority, they did affect the outcome of the elections in 2020, 2016, and beyond.

Step 2: Figure out what point you want to make

Once you know what type of paper you’re writing, you then need to figure out the point you want to make with your thesis statement, and subsequently, your paper. In other words, you need to decide to answer a question about something, such as:

- What impact did reality TV have on American society?

- How has the musical Hamilton affected perception of American history?

- Why do I want to major in [chosen major here]?

If you have an argumentative essay, then you will be writing about an opinion. To make it easier, you may want to choose an opinion that you feel passionate about so that you’re writing about something that interests you. For example, if you have an interest in preserving the environment, you may want to choose a topic that relates to that.

If you’re writing your college essay and they ask why you want to attend that school, you may want to have a main point and back it up with information, something along the lines of:

“Attending Harvard University would benefit me both academically and professionally, as it would give me a strong knowledge base upon which to build my career, develop my network, and hopefully give me an advantage in my chosen field.”

Step 3: Determine what information you’ll use to back up your point

Once you have the point you want to make, you need to figure out how you plan to back it up throughout the rest of your essay. Without this information, it will be hard to either prove or argue the main point of your thesis statement. If you decide to write about the Hamilton example, you may decide to address any falsehoods that the writer put into the musical, such as:

“The musical Hamilton, while accurate in many ways, leaves out key parts of American history, presents a nationalist view of founding fathers, and downplays the racism of the times.”

Once you’ve written your initial working thesis statement, you’ll then need to get information to back that up. For example, the musical completely leaves out Benjamin Franklin, portrays the founding fathers in a nationalist way that is too complimentary, and shows Hamilton as a staunch abolitionist despite the fact that his family likely did own slaves.

Step 4: Revise and refine your thesis statement before you start writing

Read through your thesis statement several times before you begin to compose your full essay. You need to make sure the statement is ironclad, since it is the foundation of the entire paper. Edit it or have a peer review it for you to make sure everything makes sense and that you feel like you can truly write a paper on the topic. Once you’ve done that, you can then begin writing your paper.

When writing a thesis statement, there are some common pitfalls you should avoid so that your paper can be as solid as possible. Make sure you always edit the thesis statement before you do anything else. You also want to ensure that the thesis statement is clear and concise. Don’t make your reader hunt for your point. Finally, put your thesis statement at the end of the first paragraph and have your introduction flow toward that statement. Your reader will expect to find your statement in its traditional spot.

If you’re having trouble getting started, or need some guidance on your essay, there are tools available that can help you. CollegeVine offers a free peer essay review tool where one of your peers can read through your essay and provide you with valuable feedback. Getting essay feedback from a peer can help you wow your instructor or college admissions officer with an impactful essay that effectively illustrates your point.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

How to Write a Solid Thesis Statement

The important sentence expresses your central assertion or argument

arabianEye / Getty Images

- Writing Research Papers

- Writing Essays

- English Grammar

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

A thesis statement provides the foundation for your entire research paper or essay. This statement is the central assertion that you want to express in your essay. A successful thesis statement is one that is made up of one or two sentences clearly laying out your central idea and expressing an informed, reasoned answer to your research question.

Usually, the thesis statement will appear at the end of the first paragraph of your paper. There are a few different types, and the content of your thesis statement will depend upon the type of paper you’re writing.

Key Takeaways: Writing a Thesis Statement

- A thesis statement gives your reader a preview of your paper's content by laying out your central idea and expressing an informed, reasoned answer to your research question.

- Thesis statements will vary depending on the type of paper you are writing, such as an expository essay, argument paper, or analytical essay.

- Before creating a thesis statement, determine whether you are defending a stance, giving an overview of an event, object, or process, or analyzing your subject

Expository Essay Thesis Statement Examples

An expository essay "exposes" the reader to a new topic; it informs the reader with details, descriptions, or explanations of a subject. If you are writing an expository essay , your thesis statement should explain to the reader what she will learn in your essay. For example:

- The United States spends more money on its military budget than all the industrialized nations combined.

- Gun-related homicides and suicides are increasing after years of decline.

- Hate crimes have increased three years in a row, according to the FBI.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) increases the risk of stroke and arterial fibrillation (irregular heartbeat).

These statements provide a statement of fact about the topic (not just opinion) but leave the door open for you to elaborate with plenty of details. In an expository essay, you don't need to develop an argument or prove anything; you only need to understand your topic and present it in a logical manner. A good thesis statement in an expository essay always leaves the reader wanting more details.

Types of Thesis Statements

Before creating a thesis statement, it's important to ask a few basic questions, which will help you determine the kind of essay or paper you plan to create:

- Are you defending a stance in a controversial essay ?

- Are you simply giving an overview or describing an event, object, or process?

- Are you conducting an analysis of an event, object, or process?

In every thesis statement , you will give the reader a preview of your paper's content, but the message will differ a little depending on the essay type .

Argument Thesis Statement Examples

If you have been instructed to take a stance on one side of a controversial issue, you will need to write an argument essay . Your thesis statement should express the stance you are taking and may give the reader a preview or a hint of your evidence. The thesis of an argument essay could look something like the following:

- Self-driving cars are too dangerous and should be banned from the roadways.

- The exploration of outer space is a waste of money; instead, funds should go toward solving issues on Earth, such as poverty, hunger, global warming, and traffic congestion.

- The U.S. must crack down on illegal immigration.

- Street cameras and street-view maps have led to a total loss of privacy in the United States and elsewhere.

These thesis statements are effective because they offer opinions that can be supported by evidence. If you are writing an argument essay, you can craft your own thesis around the structure of the statements above.

Analytical Essay Thesis Statement Examples

In an analytical essay assignment, you will be expected to break down a topic, process, or object in order to observe and analyze your subject piece by piece. Examples of a thesis statement for an analytical essay include:

- The criminal justice reform bill passed by the U.S. Senate in late 2018 (" The First Step Act ") aims to reduce prison sentences that disproportionately fall on nonwhite criminal defendants.

- The rise in populism and nationalism in the U.S. and European democracies has coincided with the decline of moderate and centrist parties that have dominated since WWII.

- Later-start school days increase student success for a variety of reasons.

Because the role of the thesis statement is to state the central message of your entire paper, it is important to revisit (and maybe rewrite) your thesis statement after the paper is written. In fact, it is quite normal for your message to change as you construct your paper.

- 4 Teaching Philosophy Statement Examples

- Examples of Great Introductory Paragraphs

- 100 Persuasive Essay Topics

- 50 Argumentative Essay Topics

- How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

- What Is Expository Writing?

- An Introduction to Academic Writing

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- Write an Attention-Grabbing Opening Sentence for an Essay

- How To Write an Essay

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- How to Write a Response Paper

- The Ultimate Guide to the 5-Paragraph Essay

- Understanding What an Expository Essay Is

- The Introductory Paragraph: Start Your Paper Off Right

- Tips for Writing an Art History Paper

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Tips for Writing Your Thesis Statement

1. Determine what kind of paper you are writing:

- An analytical paper breaks down an issue or an idea into its component parts, evaluates the issue or idea, and presents this breakdown and evaluation to the audience.

- An expository (explanatory) paper explains something to the audience.

- An argumentative paper makes a claim about a topic and justifies this claim with specific evidence. The claim could be an opinion, a policy proposal, an evaluation, a cause-and-effect statement, or an interpretation. The goal of the argumentative paper is to convince the audience that the claim is true based on the evidence provided.

If you are writing a text that does not fall under these three categories (e.g., a narrative), a thesis statement somewhere in the first paragraph could still be helpful to your reader.

2. Your thesis statement should be specific—it should cover only what you will discuss in your paper and should be supported with specific evidence.

3. The thesis statement usually appears at the end of the first paragraph of a paper.

4. Your topic may change as you write, so you may need to revise your thesis statement to reflect exactly what you have discussed in the paper.

Thesis Statement Examples

Example of an analytical thesis statement:

The paper that follows should:

- Explain the analysis of the college admission process

- Explain the challenge facing admissions counselors

Example of an expository (explanatory) thesis statement:

- Explain how students spend their time studying, attending class, and socializing with peers

Example of an argumentative thesis statement:

- Present an argument and give evidence to support the claim that students should pursue community projects before entering college

The Process for Developing Thesis Statements for History : Home

Process for developing thesis statements for history, developing a thesis statement for history .

More than most other academic disciplines, History is focused on clear, organized, and developed writing. And the key fundamental to writing in History is to focus on developing the proper thesis from start to finish.

You can be much more efficient in your searches for research by narrowing down a topic from the very beginning with a working thesis.

For example: Your history teacher assigns a Portfolio Project about how the US ended up fighting for the Allies in World War I. The teacher prompts you by writing that the US could have fought for either the Allies or the Central power in World War I, but they ended up fighting for just the one. Why not the other? Or how remaining neutral in the war would have affected the eventual outcome. Take a position and argue which one was the better choice and why. Defend a strong position.

So, if you develop a working thesis out of this prompt you can immediately focus in on your position.

The essential elements of a proper History working thesis:

- Asserts an historical argument - not a fact, but an ARGUMENT

- Therefore, you are asserting a position that you have to defend .

- Is historically focused and precise,

- and ALWAYS answers the question, "so what?" Why should we care, TODAY?

- Finally, your thesis should identify the main points that you are using to defend your position and will form the basis of every topic sentence in your body paragraphs. This part of the working thesis will take more time to develop.

The thesis statement can be up to three to four sentences and is expected to be at the end or your introduction.

The Finish:

Your working thesis stays with the writing project until you revise it for the VERY last time - right before submitting your whole paper. You want to make sure that is closely reflects your conclusion, which was written after you developed the body of the paper.

Remember: the very first thing that your reader will read is your introduction. First impressions are critically important. So, you will want to go back and update your thesis, which will be the end of your writing process.

Using the prompt above, here is a successful thesis:

Although the US entered World War I on the Allied side against Germany and the Central Power on April 6, 1917, the war had already been raging in Europe for three years. The largest ethnic group in the US were German, equating to 10% of the population; yet while a majority of the nation favored England, France and the other Allies--both groups highly favored US neutrality as the best approach. Therefore, had Germany not continue responding to the Allied blockade by indiscriminately sinking all ships, regardless of citizenship and cargo, the US would have stayed neutral, and the eventual tide of the war would have gone the other way - for the Central Powers.

These helpful tips were provided by James Meredith -

- Last Updated: Jun 3, 2024 2:03 PM

- URL: https://csuglobal.libguides.com/thesis_statement

How to write a PhD thesis: a step-by-step guide

A draft isn’t a perfect, finished product; it is your opportunity to start getting words down on paper, writes Kelly Louise Preece

Kelly Louise Preece

Created in partnership with

You may also like

Popular resources

.css-1txxx8u{overflow:hidden;max-height:81px;text-indent:0px;} How to develop a researcher mindset as a PhD student

Formative, summative or diagnostic assessment a guide, emotions and learning: what role do emotions play in how and why students learn, how to assess and enhance students’ ai literacy, how hard can it be testing ai detection tools.

Congratulations; you’ve finished your research! Time to write your PhD thesis. This resource will take you through an eight-step plan for drafting your chapters and your thesis as a whole.

Organise your material

Before you start, it’s important to get organised. Take a step back and look at the data you have, then reorganise your research. Which parts of it are central to your thesis and which bits need putting to one side? Label and organise everything using logical folders – make it easy for yourself! Academic and blogger Pat Thomson calls this “Clean up to get clearer” . Thomson suggests these questions to ask yourself before you start writing:

- What data do you have? You might find it useful to write out a list of types of data (your supervisor will find this list useful too.) This list is also an audit document that can go in your thesis. Do you have any for the “cutting room floor”? Take a deep breath and put it in a separate non-thesis file. You can easily retrieve it if it turns out you need it.

- What do you have already written? What chunks of material have you written so far that could form the basis of pieces of the thesis text? They will most likely need to be revised but they are useful starting points. Do you have any holding text? That is material you already know has to be rewritten but contains information that will be the basis of a new piece of text.

- What have you read and what do you still need to read? Are there new texts that you need to consult now after your analysis? What readings can you now put to one side, knowing that they aren’t useful for this thesis – although they might be useful at another time?

- What goes with what? Can you create chunks or themes of materials that are going to form the basis of some chunks of your text, perhaps even chapters?

Once you have assessed and sorted what you have collected and generated you will be in much better shape to approach the big task of composing the dissertation.

Decide on a key message

A key message is a summary of new information communicated in your thesis. You should have started to map this out already in the section on argument and contribution – an overarching argument with building blocks that you will flesh out in individual chapters.

You have already mapped your argument visually, now you need to begin writing it in prose. Following another of Pat Thomson’s exercises, write a “tiny text” thesis abstract. This doesn’t have to be elegant, or indeed the finished product, but it will help you articulate the argument you want your thesis to make. You create a tiny text using a five-paragraph structure:

- The first sentence addresses the broad context. This locates the study in a policy, practice or research field.

- The second sentence establishes a problem related to the broad context you have set out. It often starts with “But”, “Yet” or “However”.

- The third sentence says what specific research has been done. This often starts with “This research” or “I report…”

- The fourth sentence reports the results. Don’t try to be too tricky here, just start with something like: “This study shows,” or “Analysis of the data suggests that…”

- The fifth and final sentence addresses the “So What?” question and makes clear the claim to contribution.

Here’s an example that Thomson provides:

Secondary school arts are in trouble, as the fall in enrolments in arts subjects dramatically attests. However, there is patchy evidence about the benefits of studying arts subjects at school and this makes it hard to argue why the drop in arts enrolments matters. This thesis reports on research which attempts to provide some answers to this problem – a longitudinal study which followed two groups of senior secondary students, one group enrolled in arts subjects and the other not, for three years. The results of the study demonstrate the benefits of young people’s engagement in arts activities, both in and out of school, as well as the connections between the two. The study not only adds to what is known about the benefits of both formal and informal arts education but also provides robust evidence for policymakers and practitioners arguing for the benefits of the arts. You can find out more about tiny texts and thesis abstracts on Thomson’s blog.

- Writing tips for higher education professionals

- Resource collection on academic writing

- What is your academic writing temperament?

Write a plan

You might not be a planner when it comes to writing. You might prefer to sit, type and think through ideas as you go. That’s OK. Everybody works differently. But one of the benefits of planning your writing is that your plan can help you when you get stuck. It can help with writer’s block (more on this shortly!) but also maintain clarity of intention and purpose in your writing.

You can do this by creating a thesis skeleton or storyboard , planning the order of your chapters, thinking of potential titles (which may change at a later stage), noting down what each chapter/section will cover and considering how many words you will dedicate to each chapter (make sure the total doesn’t exceed the maximum word limit allowed).

Use your plan to help prompt your writing when you get stuck and to develop clarity in your writing.

Some starting points include:

- This chapter will argue that…

- This section illustrates that…

- This paragraph provides evidence that…

Of course, we wish it werethat easy. But you need to approach your first draft as exactly that: a draft. It isn’t a perfect, finished product; it is your opportunity to start getting words down on paper. Start with whichever chapter you feel you want to write first; you don’t necessarily have to write the introduction first. Depending on your research, you may find it easier to begin with your empirical/data chapters.

Vitae advocates for the “three draft approach” to help with this and to stop you from focusing on finding exactly the right word or transition as part of your first draft.

This resource originally appeared on Researcher Development .

Kelly Louse Preece is head of educator development at the University of Exeter.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter .

How to develop a researcher mindset as a PhD student

A diy guide to starting your own journal, contextual learning: linking learning to the real world, what does a university faculty senate do, hybrid learning through podcasts: a practical approach, how exactly does research get funded.

Register for free

and unlock a host of features on the THE site

Watch CBS News

Trump was found guilty in his "hush money" trial. Here's what to know about the verdict and the case.

By Graham Kates

Updated on: May 31, 2024 / 11:57 AM EDT / CBS News

Former President Donald Trump was found guilty of 34 counts of falsifying business records by a jury in New York on Thursday, marking the end of a historic trial stemming from a "hush money" payment made to an adult film star before the 2016 election.

The trial lasted roughly six weeks, and the jury spent two days deliberating before returning a verdict. Trump denounced the decision as "rigged" and vowed to fight the conviction. His sentencing is scheduled for July 11.

Here are the basics of the charges, what happened during the trial and what comes next:

What were the charges?

Trump was indicted on March 30, 2023, and charged with 34 state counts of falsifying business records in the first degree, a felony in New York.

What was the verdict?

Trump was found guilty on all charges on May 30, 2024. The jury returned a unanimous verdict in the Manhattan courtroom where the trial unfolded for six weeks.

What was needed for the jury to convict?

Justice Juan Merchan instructed jurors before they began deliberations that in order to find Trump guilty of falsifying business records in the first degree, they needed to unanimously conclude not only that he caused records to be falsified, but that he "conspired to promote or prevent the election of any person to a public office by unlawful means."

There were a few types of "unlawful means" that the jury heard evidence about, including: falsification of other business records, violations of campaign finance laws and violations of tax tax laws.

What exactly did prosecutors say Trump did?

Prosecutors from Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg's office said Trump met with former National Enquirer publisher David Pecker and ex-fixer Michael Cohen in his Trump Tower in August 2015, and that the trio hatched a conspiracy to identify, purchase and squash stories that might harm Trump's reputation and presidential campaign.

Just days before the 2016 election, Cohen paid $130,000 to adult film star Stormy Daniels , who claimed she had sex with Trump in 2006. She agreed to keep her story under wraps in exchange for the money.

After Trump became president, Cohen was paid $35,000 a month for a year in a series of checks, most of which were signed by Trump. Prosecutors said the checks and associated business records were illegally portrayed as payments to Cohen for his legal work, when in fact they were intended to reimburse him for the Daniels deal, among other things.

What did Trump's lawyers say?

Trump's lawyers said the arrangement with Pecker and the National Enquirer was not atypical for political campaigns, which often try to influence media narratives about candidates. They said non-disclosure agreements like the one Cohen struck with Daniels are common, too.

As for the checks to Cohen, Trump's lawyers noted that Cohen's title at the time was "personal attorney to the president," and he actually was being paid for ongoing legal work. They said Cohen and Trump had a verbal retainer agreement, but not a signed one.

How about Trump himself?

Trump pleaded not guilty to the charges and denied all wrongdoing. He accused Bragg, a Democrat, of pursuing the case for political gain. Trump has called the case a "con job" and said the charges were "rigged" after the verdict came down.

Who were the key players?

Trump, Cohen and Pecker got top billing during the trial. Pecker was called to the stand by prosecutors first, and described the August 2015 Trump Tower meeting , as well as years of communications with Cohen and Trump about the scheme.

His testimony corroborated key moments relayed by Cohen, whose credibility the defense repeatedly sought throughout to undermine. Pecker's time on the stand was the lead-in to weeks worth of testimony from 18 others before Cohen, their final witness. Prosecutors sought to use those weeks to back up Cohen's story with corroborating evidence.

During the first day of their deliberations, the jury asked to hear portions of Pecker and Cohen's testimony related to the Trump Tower meeting.

What did Cohen say?

Cohen said Trump received regular updates on efforts to cover up salacious stories about him when he ran for president in 2016, and personally signed off on the scheme to falsify records related to them.

Cohen recounted three instances when he, Pecker and the editor of the National Enquirer worked to secure the rights to stories with salacious claims about Trump.

The jury heard a secret recording Cohen made of a conversation with Trump, in which Trump appeared comfortable with the purchase of a story told by another woman, named Karen McDougal.

"So, what do we got to pay for this? 150?" Trump can be heard saying on the tape.

Not long after the Enquirer paid for McDougal's story, Daniels' story hit the market. Her attorney approached the Enquirer about selling the rights one day after the release of the "Access Hollywood" tape in October 2016. On the recording, Trump was heard saying he could "grab [women] by the p****" and "make them do anything." The tape posed a major threat to his electoral prospects.

Cohen recounted intense negotiations in which everyone involved — Trump, Cohen, Daniels, her attorney and the Enquirer editor — were aware that Daniels' claim of a sexual encounter with Trump might have dire consequences for his campaign.

Cohen wired Daniels' attorney $130,000 of his own money on Oct. 28, 2016.

During his testimony, Cohen described how working for Trump for a decade was an "amazing" experience that turned sour after the "hush money" payment to Daniels became public in 2018.

He testified that he believed he was subject to a "pressure campaign" by Trump and his allies after the FBI raided his home and office that year, leading to a pair of guilty pleas to federal charges.

Under scathing cross-examination from defense attorney Todd Blanche, Cohen acknowledged that he's since made a living by loudly criticizing Trump.

He admitted wanting to see Trump imprisoned, and saying as much on his podcast.

Cohen also acknowledged lying under oath on multiple occasions, and, in a shocking moment, admitted for the first time to having stolen tens of thousands of dollars from the Trump Organization.

What did Daniels say on the stand?

Daniels wasn't part of the scheme to influence the election. She never worked for Trump and had no involvement in any of the crimes alleged in the case.

Still, her story of sex with Trump in 2006 was the catalyst that sparked a series of events leading to this unprecedented criminal trial. Prosecutors said she was called to the stand because Blanche denied they ever had sex in his opening statement, an assertion they believed they had to rebut.

Daniels said she met Trump at a celebrity golf tournament in Nevada, and later was invited by Trump's bodyguard to a dinner with the famed businessman. She said they met up at a hotel suite she described in elaborate detail, right down to the tiles, and she was expecting to go to dinner when instead they began talking about business.

Daniels said Trump showed a keen interest in her industry, and seemed to value her insights. After some two hours of talking, with no dinner in sight, she excused herself to go to the bathroom. She recalled being surprised when she emerged to see that Trump had undressed down to a T-shirt and boxers. She described the sex that followed as, on her part, reluctant.

This part of her testimony caused the defense to demand a mistrial, a motion that was denied.

Daniels then described interacting with Trump frequently over the next year or so — including briefly meeting with him at Trump Tower — because he promised to advocate for her to get a spot on his reality television competition. When he told her it wouldn't happen, they stopped communicating.

Later, through a representative, she began shopping her story, seeking to sell the rights to it. When Trump's presidential candidacy gained steam in 2016, those efforts also became heated. They reached a fever in October of that year, when the "Access Hollywood" outtake surfaced.

Daniels said she realized her story was potentially more valuable, because it could be bad for his campaign. Cohen testified to frantic efforts to purchase it.

What comes next?

Trump's conviction kickstarts the sentencing portion of the case. Merchan, the judge, set a date of July 11 for Trump's sentencing hearing. He asked the defense to submit any motions they plan to request no later than June 13, and said prosecutors must respond by June 27.

Falsification of business records carries a maximum sentence of four years in prison and a $5,000 fine for each charge, but Merchan has broad leeway when determining the punishment. Some experts expect Merchan to use other options, like fines, probation or home confinement. But others say he could order Trump to serve some time behind bars.

- Donald Trump

Graham Kates is an investigative reporter covering criminal justice, privacy issues and information security for CBS News Digital. Contact Graham at [email protected] or [email protected]

More from CBS News

Views of Trump trial unchanged following verdict — CBS News poll

3 Trump allies charged in Wisconsin for 2020 fake elector scheme

Georgia court sets tentative Oct. 4 date to hear Trump appeal of Willis ruling

Garland tells GOP House members, "I will not be intimidated"

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples

What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples

Published on 15 September 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on 5 December 2023.

A thesis is a type of research paper based on your original research. It is usually submitted as the final step of a PhD program in the UK.

Writing a thesis can be a daunting experience. Indeed, alongside a dissertation , it is the longest piece of writing students typically complete. It relies on your ability to conduct research from start to finish: designing your research , collecting data , developing a robust analysis, drawing strong conclusions , and writing concisely .

Thesis template

You can also download our full thesis template in the format of your choice below. Our template includes a ready-made table of contents , as well as guidance for what each chapter should include. It’s easy to make it your own, and can help you get started.

Download Word template Download Google Docs template

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Thesis vs. thesis statement, how to structure a thesis, acknowledgements or preface, list of figures and tables, list of abbreviations, introduction, literature review, methodology, reference list, proofreading and editing, defending your thesis, frequently asked questions about theses.

You may have heard the word thesis as a standalone term or as a component of academic writing called a thesis statement . Keep in mind that these are two very different things.

- A thesis statement is a very common component of an essay, particularly in the humanities. It usually comprises 1 or 2 sentences in the introduction of your essay , and should clearly and concisely summarise the central points of your academic essay .

- A thesis is a long-form piece of academic writing, often taking more than a full semester to complete. It is generally a degree requirement to complete a PhD program.

- In many countries, particularly the UK, a dissertation is generally written at the bachelor’s or master’s level.

- In the US, a dissertation is generally written as a final step toward obtaining a PhD.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

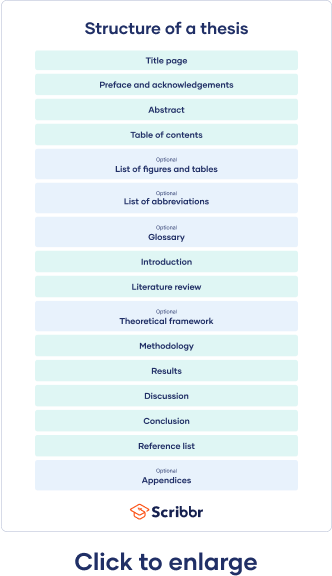

The final structure of your thesis depends on a variety of components, such as:

- Your discipline

- Your theoretical approach

Humanities theses are often structured more like a longer-form essay . Just like in an essay, you build an argument to support a central thesis.

In both hard and social sciences, theses typically include an introduction , literature review , methodology section , results section , discussion section , and conclusion section . These are each presented in their own dedicated section or chapter. In some cases, you might want to add an appendix .

Thesis examples

We’ve compiled a short list of thesis examples to help you get started.

- Example thesis #1: ‘Abolition, Africans, and Abstraction: the Influence of the “Noble Savage” on British and French Antislavery Thought, 1787-1807’ by Suchait Kahlon.

- Example thesis #2: ‘”A Starving Man Helping Another Starving Man”: UNRRA, India, and the Genesis of Global Relief, 1943-1947’ by Julian Saint Reiman.

The very first page of your thesis contains all necessary identifying information, including:

- Your full title

- Your full name

- Your department

- Your institution and degree program

- Your submission date.

Sometimes the title page also includes your student ID, the name of your supervisor, or the university’s logo. Check out your university’s guidelines if you’re not sure.

Read more about title pages

The acknowledgements section is usually optional. Its main point is to allow you to thank everyone who helped you in your thesis journey, such as supervisors, friends, or family. You can also choose to write a preface , but it’s typically one or the other, not both.

Read more about acknowledgements Read more about prefaces

An abstract is a short summary of your thesis. Usually a maximum of 300 words long, it’s should include brief descriptions of your research objectives , methods, results, and conclusions. Though it may seem short, it introduces your work to your audience, serving as a first impression of your thesis.

Read more about abstracts

A table of contents lists all of your sections, plus their corresponding page numbers and subheadings if you have them. This helps your reader seamlessly navigate your document.

Your table of contents should include all the major parts of your thesis. In particular, don’t forget the the appendices. If you used heading styles, it’s easy to generate an automatic table Microsoft Word.

Read more about tables of contents

While not mandatory, if you used a lot of tables and/or figures, it’s nice to include a list of them to help guide your reader. It’s also easy to generate one of these in Word: just use the ‘Insert Caption’ feature.

Read more about lists of figures and tables

If you have used a lot of industry- or field-specific abbreviations in your thesis, you should include them in an alphabetised list of abbreviations . This way, your readers can easily look up any meanings they aren’t familiar with.

Read more about lists of abbreviations

Relatedly, if you find yourself using a lot of very specialised or field-specific terms that may not be familiar to your reader, consider including a glossary . Alphabetise the terms you want to include with a brief definition.

Read more about glossaries

An introduction sets up the topic, purpose, and relevance of your thesis, as well as expectations for your reader. This should:

- Ground your research topic , sharing any background information your reader may need

- Define the scope of your work

- Introduce any existing research on your topic, situating your work within a broader problem or debate

- State your research question(s)

- Outline (briefly) how the remainder of your work will proceed

In other words, your introduction should clearly and concisely show your reader the “what, why, and how” of your research.

Read more about introductions

A literature review helps you gain a robust understanding of any extant academic work on your topic, encompassing:

- Selecting relevant sources

- Determining the credibility of your sources

- Critically evaluating each of your sources

- Drawing connections between sources, including any themes, patterns, conflicts, or gaps

A literature review is not merely a summary of existing work. Rather, your literature review should ultimately lead to a clear justification for your own research, perhaps via:

- Addressing a gap in the literature

- Building on existing knowledge to draw new conclusions

- Exploring a new theoretical or methodological approach

- Introducing a new solution to an unresolved problem

- Definitively advocating for one side of a theoretical debate

Read more about literature reviews

Theoretical framework

Your literature review can often form the basis for your theoretical framework, but these are not the same thing. A theoretical framework defines and analyses the concepts and theories that your research hinges on.

Read more about theoretical frameworks

Your methodology chapter shows your reader how you conducted your research. It should be written clearly and methodically, easily allowing your reader to critically assess the credibility of your argument. Furthermore, your methods section should convince your reader that your method was the best way to answer your research question.

A methodology section should generally include:

- Your overall approach ( quantitative vs. qualitative )

- Your research methods (e.g., a longitudinal study )

- Your data collection methods (e.g., interviews or a controlled experiment

- Any tools or materials you used (e.g., computer software)

- The data analysis methods you chose (e.g., statistical analysis , discourse analysis )

- A strong, but not defensive justification of your methods

Read more about methodology sections

Your results section should highlight what your methodology discovered. These two sections work in tandem, but shouldn’t repeat each other. While your results section can include hypotheses or themes, don’t include any speculation or new arguments here.

Your results section should:

- State each (relevant) result with any (relevant) descriptive statistics (e.g., mean , standard deviation ) and inferential statistics (e.g., test statistics , p values )

- Explain how each result relates to the research question

- Determine whether the hypothesis was supported

Additional data (like raw numbers or interview transcripts ) can be included as an appendix . You can include tables and figures, but only if they help the reader better understand your results.

Read more about results sections

Your discussion section is where you can interpret your results in detail. Did they meet your expectations? How well do they fit within the framework that you built? You can refer back to any relevant source material to situate your results within your field, but leave most of that analysis in your literature review.

For any unexpected results, offer explanations or alternative interpretations of your data.

Read more about discussion sections

Your thesis conclusion should concisely answer your main research question. It should leave your reader with an ultra-clear understanding of your central argument, and emphasise what your research specifically has contributed to your field.

Why does your research matter? What recommendations for future research do you have? Lastly, wrap up your work with any concluding remarks.

Read more about conclusions

In order to avoid plagiarism , don’t forget to include a full reference list at the end of your thesis, citing the sources that you used. Choose one citation style and follow it consistently throughout your thesis, taking note of the formatting requirements of each style.

Which style you choose is often set by your department or your field, but common styles include MLA , Chicago , and APA.

Create APA citations Create MLA citations

In order to stay clear and concise, your thesis should include the most essential information needed to answer your research question. However, chances are you have many contributing documents, like interview transcripts or survey questions . These can be added as appendices , to save space in the main body.

Read more about appendices

Once you’re done writing, the next part of your editing process begins. Leave plenty of time for proofreading and editing prior to submission. Nothing looks worse than grammar mistakes or sloppy spelling errors!

Consider using a professional thesis editing service to make sure your final project is perfect.

Once you’ve submitted your final product, it’s common practice to have a thesis defense, an oral component of your finished work. This is scheduled by your advisor or committee, and usually entails a presentation and Q&A session.

After your defense, your committee will meet to determine if you deserve any departmental honors or accolades. However, keep in mind that defenses are usually just a formality. If there are any serious issues with your work, these should be resolved with your advisor way before a defense.

The conclusion of your thesis or dissertation shouldn’t take up more than 5-7% of your overall word count.

When you mention different chapters within your text, it’s considered best to use Roman numerals for most citation styles. However, the most important thing here is to remain consistent whenever using numbers in your dissertation .

If you only used a few abbreviations in your thesis or dissertation, you don’t necessarily need to include a list of abbreviations .

If your abbreviations are numerous, or if you think they won’t be known to your audience, it’s never a bad idea to add one. They can also improve readability, minimising confusion about abbreviations unfamiliar to your reader.

A thesis or dissertation outline is one of the most critical first steps in your writing process. It helps you to lay out and organise your ideas and can provide you with a roadmap for deciding what kind of research you’d like to undertake.

Generally, an outline contains information on the different sections included in your thesis or dissertation, such as:

- Your anticipated title

- Your abstract