- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How Short-Term Memory Works

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Armeen Poor, MD, is a board-certified pulmonologist and intensivist. He specializes in pulmonary health, critical care, and sleep medicine.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Armeen-fb0d3f30559742abbb4c13376445b7ab.jpg)

- Transfer to Long-Term Memory

- Short-Term Memory Loss

Frequently Asked Questions

Short-term memory is the capacity to store a small amount of information in the mind and keep it readily available for a short period of time. It is also known as primary or active memory.

Short-term memory is essential for daily functioning, which is why experiencing short-term memory loss can be frustrating and even debilitating.

- Short-term memory is very brief . When short-term memories are not rehearsed or actively maintained, they last mere seconds.

- Short-term memory is limited . It is commonly suggested that short-term memory can hold only seven items at once, plus or minus two.

How Long Is Short-Term Memory For?

Most of the information kept in short-term memory will be stored for approximately 20 to 30 seconds, or even less. Some information can last in short-term memory for up to a minute, but most information spontaneously decays quite quickly, unless you use rehearsal strategies such as saying the information aloud or mentally repeating it.

However, the information in short-term memory is also highly susceptible to interference . Any new information that enters short-term memory will quickly displace old information . Similar items in the environment can also interfere with short-term memories.

For example, you might have a harder time remembering someone's name if you're in a crowded, noisy room, or if you were thinking of what to say to the person rather than paying attention to their name.

While many short-term memories are quickly forgotten, attending to this information allows it to continue the next stage — long-term memory .

The amount of information that can be stored in short-term memory can vary. In 1956, in an influential paper titled "The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two," psychologist George Miller suggested that people can store between five and nine items in short-term memory.

More recent research suggests that people are capable of storing approximately four chunks or pieces of information in short-term memory.

For example, imagine that you are trying to remember a phone number. The other person rattles off the 10-digit phone number, and you make a quick mental note. Moments later you realize that you have already forgotten the number. Without rehearsing or continuing to repeat the number until it is committed to memory, the information is quickly lost from short-term memory.

Short-Term vs. Working Memory

Some researchers argue that working memory and short-term memory significantly overlap, and may even be the same thing. The distinction is that working memory refers to the ability to use, manipulate, and apply memory for a period of time (for example, recalling a set of instructions as you complete a task), while short-term memory refers only to the temporary storage of information in memory.

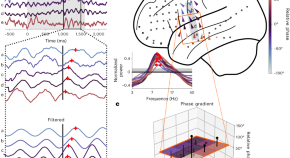

The Baddeley-Hitch model of working memory suggests that there are two components of working memory: a place where you store visual and spatial information (visuospatial scratchpad), and a place where you record auditory information (phonological loop). In addition, the model suggests there is a "central executive" that controls and mediates these two components as well as processes information, directs attention , sets goals, and makes decisions .

How Short-Term Memory Becomes Long-Term Memory

Memory researchers often use what is referred to as the three-store model to conceptualize human memory. This model suggests that memory consists of three basic stores— sensory , short-term, and long-term—and that each of these can be distinguished based on storage capacity and duration.

While long-term memory has a seemingly unlimited capacity that lasts years, short-term memory is relatively brief and limited. Short-term memory is limited in both capacity and duration. In order for a memory to be retained, it needs to be transferred from short-term stores into long-term memory. The exact mechanisms for how this happens remain controversial and not well understood.

The classic model, known as the Atkinson-Shiffrin model or multi-modal model, suggested that all short-term memories were automatically placed in long-term memory after a certain amount of time.

More recently, researchers have proposed that some mental editing takes place and that only particular memories are selected for long-term retention. Factors such as time and interference can affect how information in encoded in memory.

The information-processing view of memory suggests that human memory works much like a computer. In this model, information first enters short-term memory (a temporary holding store for recent events) and then some of this information is transferred into long-term memory (a relatively permanent store), much like information on a computer being placed on a hard disk.

Some researchers, however, dispute the idea that there are separate stores for short-term and long-term memories at all.

Maintenance Rehearsal

Maintenance rehearsal (or rehearsal) can help move memories from short-term to long-term memory. For example, you might use this approach when studying materials for an exam. Instead of just reviewing the information once or twice, you might go over your notes repeatedly until the critical information is committed to memory.

Chunking is one memorization technique that can facilitate the transfer of information into long-term memory. This approach involves organizing information into more easily learned groups, phrases, words, or numbers.

For example, it will take a large amount of effort to memorize the following number: 65,495,328,463. However, it will be easier to remember if it is chunked into the following: 6549 532 8463.

Easily remembered mnemonic phrases, abbreviations, or rhymes can help move short-term memories into long-term storage. A few common examples include:

- ROY G BIV : An acronym that represents the first letter of each color of the rainbow—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet

- I before E, except after C : A rhyme used to remember the spelling of common words

- Thirty days hath September... : A poem used to remember how many days are in each month

Another mnemonic strategy, which dates back to around 500 BCE, is the method of loci. The method of loci involves mentally placing the items you are trying to learn or remember around a room—such as on the sofa, next to a plant, or on the window seat. To trigger your memory, you then visualize yourself going to each location, triggering your recall for that information.

Memory Consolidation

Memory consolidation is the process in which the brain converts short-term memories into long-term ones. Rehearsing or recalling information over and over again creates structural changes in the brain that strengthen neural networks. The repeated firing of two neurons makes it more likely that they will repeat that firing again in the future.

What Is Considered Short-Term Memory Loss?

For most of us, it's pretty common to experience an episode of memory loss occasionally. This can look like missing a monthly payment, forgetting the date, losing our keys, or having trouble finding the right word to use from time to time.

If you feel like you're constantly forgetting things, it can be irritating, frustrating, and frightening. Short-term memory loss may even make you worried that your brain is too reliant on devices like your smartphone rather than your memory to recall information.

What Is Short-Term Memory a Symptom of?

Mild memory loss doesn't always indicate a problem, and certain memory changes are a normal part of aging. Short-term memory loss can also be caused by other, non-permanent factors , including:

- Alcohol or drug use

- Medication side effects

- Sleep deprivation

If you are concerned about memory lapses or any other brain changes, talk to your healthcare provider. They can give you a thorough exam to determine what might be causing your symptoms and recommend lifestyle changes, strategies, or treatments to improve your short-term memory .

Short-term memory plays a vital role in shaping our ability to function in the world around us, but it is limited in terms of both capacity and duration. Disease and injury as well as increasing reliance on smartphones can also have an influence on the ability to store short-term memories. As researchers continue to learn more about factors that influence memory, new ways of enhancing and protecting short-term memory may emerge.

There are many potential causes of short-term memory loss, and many of them are reversible. Memory loss may be a side effect of medication (or a combination of medications). It can occur after a head injury or as a result of vitamin B-12 deficiency. Hypothyroidism (an underactive thyroid gland) can affect memory. So can stress, anxiety, depression, and alcohol use. Or, memory loss could be a symptom of a serious condition, such as dementia or a brain tumor.

Maintenance rehearsal is a way to preserve information in long-term memory. It might mean repeating or otherwise accessing information that is stored in long-term memory to make sure that you retain it.

Living a healthy lifestyle may help preserve and improve memory. That means getting regular physical activity, eating a healthy diet, limiting alcohol and drug use, and sleeping well.

It's also important to keep your brain active. Regular social interactions, along with cognitive activities like word games and learning new skills, may help keep memory issues at bay.

You can also use techniques like mnemonics, rehearsal, chunking, and organizational strategies (such as taking notes and using phone alarms) to help support your memory.

Cowan N. What are the differences between long-term, short-term, and working memory? . Prog Brain Res . 2008;169:323-338. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(07)00020-9

Miller GA. The magical number seven plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information . Psychol Rev . 1956;63(2):81–97.

Atkinson RC, Shiffrin RM. The control processes of short-term memory . Institute for Mathematical Studies in the Social Sciences, Stanford University.

Kelley P, Evans MDR, Kelley J. Making memories: Why time matters . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:400. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00400

Chai WJ, Abd Hamid AI, Abdullah JM. Working memory from the psychological and neurosciences perspectives: A review . Front Psychol . 2018;9:401. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00401

Zlotnik G, Vansintjan A. Memory: An extended definition . Front Psychol . 2019;10:2523. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02523

Adams EJ, Nguyen AT, Cowan N. Theories of working memory: Differences in definition, degree of modularity, role of attention, and purpose . Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch . 2018;49(3):340-355. doi:10.1044/2018_LSHSS-17-0114

Legge ELG, Madan CR, Ng ET, Caplan JB. Building a memory palace in minutes: Equivalent memory performance using virtual versus conventional environments with the Method of Loci . Acta Psychol (Amst) . 2012;141(3):380-390. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2012.09.002

National Institute on Aging. Do memory problems always mean Alzheimer's disease? .

Mayo Clinic. Memory loss: When to seek help .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Short-Term Memory: How It Works and How to Improve It

Categories Memory

Short-term memory (STM) is a type of memory that can hold a small amount of information for a limited period of time. The duration and capacity of short-term memory is quite limited, holding between five to nine pieces of information for around 20 to 30 seconds.

You’ve probably experienced these limitations yourself many times. Consider the last time you thought of something you needed to do and walked into another room to do the thing you just thought of, only to discover that you can’t remember what you would do. This is an example of short-term memory failure.

Problems with short-term memory can range from minor annoyances to more severe signs of a serious health problem. Understanding how short-term memory works can help you better spot potential issues and look for ways to boost your short-term memory.

Table of Contents

Characteristics of Short-Term Memory

Short-term memory is distinguished from other types/stages of memory by a few key factors:

- Limited capacity : Short-term memory can only hold a limited amount of information. In his classic research, George Miller suggested that this number was the “magic number seven, plus or minus two. This means STM can hold between 5 and 9 items at a time.

- Limited duration : As the name indicates, short-term memory is brief. While estimates vary, it typically lasts around 15 to 30 seconds unless the information is actively rehearsed.

Understanding How Memory Works

A number of models have been introduced to explain how memory works and the different parts of memory. Some theories describe memory as consisting of distinct types of memory. Others conceptualize these as stages of memory.

In any case, the four main types (or stages) of memory are:

- Sensory memory : This is the initial stage of memory that holds sensory information for a very brief period of time. While it has a large capacity, it is very brief in duration.

- Short-term memory : Information that you attend to can be transferred from sensory memory to the second stage of memory, which is short-term memory.

- Working memory : This type of memory is sometimes described as a distinct type of memory, it is often identified as a form of short-term memory. It is the part of memory for the immediate, small amount of information you are currently using.

- Long-term memory : Short-term memories that are rehearsed may be transferred to long-term memory, an enduring and virtually limitless store that can last a very long time. Long-term memories can also be identified as either explicit (which form consciously) or implicit (which form unconsciously).

How Short-Term Memory Differs From Working Memory

While short-term and working memory are often described as the same, not all experts agree. Some feel that they are essentially the same thing.

Some important differences that help distinguish between the two:

- Working memory is active : It involves actively using and manipulating small amounts of information.

- Short-term memory is passive : It involves a temporary store for information you have attended to.

Short-term memory is where these memories are briefly stored, while working memory allows them to be actively utilized and manipulated.

Consolidating Short-Term to Long-Term Memory

Because short-term memory is so limited, information has to be transferred into long-term memory in order for it to be retained. So, how exactly does this information go from being the type of information we forget after about 30 seconds to the type of information we remember for years or decades?

Short-term memories become long-term through a process known as memory consolidation. This process involves a few different factors:

Every time you access a memory, the neural network involved in that memory becomes stronger. It’s a bit like walking along a hiking trail; the more frequently you walk it, the more worn it becomes.

As you actively rehearse information in short-term memory, those neural networks fire together and strengthen the “path” for that memory. This means that the next time you want to access that specific information, it will come to mind much more readily.

Elaborative Rehearsal

Repetition is important, but forming meaningful connections with existing information can further cement memories into long-term storage.

Elaborative rehearsal involves thinking about the meaning of new information and memories you have acquired and then making connections or associations with things you have already stored in your memory.

Sleep also plays a crucial role in memory consolidation. Important structures in the brain, specifically the hippocampus and neocortex, are key to this process. During sleep, the hippocampus consolidates short-term memories and moves them into the brain’s cerebral cortex.

When people experience damage to the hippocampus, they may experience retrograde amnesia, which involves the inability to remember past events stored in long-term memory.

Strategies for Improving Short-Term Memory

If you find yourself constantly forgetting things like where you put your phone, a name you just learned, or other types of information that you need to live your day-to-day life, it might mean your short-term memory could use some work. There are a number of strategies you might try to help boost your short-term memory:

Chunking involves grouping information into smaller and easier to remember, chunks. If you were trying to memorize a list, for example, you might group the items into smaller units based on similar features.

If you want to improve your short-term memory, chunking can be a useful tactic.

Mnemonics are memory strategies that involve using easily remembered elements, like acronyms or rhymes, to remember information. Using mnemonics can boost short-term memory by creating associations between things you’ve just learned and other things you already know that are easy to recall.

Visualization

Visualization involves creating mental images of the information you are trying to remember. This can help keep the information in your short-term memory more readily, and may facilitate the transfer of this information from short-term memory into long-term memory.

Real-World Examples of Short-Term Memory

Short-term memory plays a pivotal role in our lives. Our short-term memory is constantly in use as we live our lives, allowing us to remember what we are doing, what we’ve just said, the things we’ve just heard, and where we place things just moments ago.

Academic Performance

In school, short-term memory is vital to the learning process. It allows us to take in what a teacher says and temporarily hold essential details. It also allows us to remember things we’ve just read, relate what we learn to prior knowledge, and respond to questions the teacher asks.

Learning strategies like taking notes, using visual aids, and chunking related information on flashcards can help facilitate the transfer of short-term memories into long-term storage.

Everyday Life

Short-term memory allows us to function in our daily life, including at home, at work, and in our relationships. When someone tells us about an appointment, name, or phone number, we store that information in short-term memory until we can jot it down for future use.

Short-term memory also allows us to remember what we look for on the self as we shop for groceries. Plus, it lets us hold information long enough for us to respond to what others have to say.

Short-Term Memory Loss

Short-term memory loss can have a serious impact on a person’s ability to function. Some of the different factors that can contribute to short-term memory loss include:

Anxiety and Stress

Stress hormones can affect the brain’s hippocampus, a region that plays an important role in memory formation. Anxiety can also interfere with your ability to concentrate, which can affect short-term memory.

Sleep Deprivation

Poor quality or inadequate sleep can affect various cognitive functions, including short-term memory. Remember, sleep plays a vital role in memory consolidation. That’s why you might find it more difficult to remember things when you are tired or sleep-deprived.

Head Injuries

Traumatic brain injuries can also affect short-term memory. The degree of impairment that a person experiences depends on the nature, location, and severity of the damage.

Medical Conditions

Neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and dementia also affect short-term memory. This loss is progressive, which means that it worsens over time.

Certain Medications

Some medications can have an impact on short-term memory. This includes antihistamines, some antidepressants, and benzodiazepines.

People often experience a variety of cognitive symptoms when they are depressed, including difficulties with concentration and memory.

The normal aging process can also lead to changes in short-term memory. Such changes are normal and often mild. If a person experiences more severe impairments as they age, it might be a sign of a more serious problem.

Substance Use

Using alcohol and other types of drugs can also have an effect on memory. Some of these impairments may be more severe when a person is intoxicated, but long-term use can affect the brain’s ability to process information and form memories effectively.

If you have noticed problems with your short-term memory , you might try strategies such as chunking or visualization to improve it. But if these impairments seem serious, are worsening, or are affecting your ability to function, it is important to talk to your doctor to learn more.

Chai WJ, Abd Hamid AI, Abdullah JM. Working memory from the psychological and neurosciences perspectives: A review . Front Psychol . 2018;9:401. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00401

Cowan N. What are the differences between long-term, short-term, and working memory ? Prog Brain Res . 2008;169:323-338. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(07)00020-9

Mayo Clinic. Memory loss: When to seek help .

Squire LR, Genzel L, Wixted JT, Morris RG. Memory consolidation . Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol . 2015;7(8):a021766. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a021766

Vallar G. Short-term memory . In: Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology . Elsevier; 2017:B9780128093245032000. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-809324-5.03170-9

Zlotnik G, Vansintjan A. Memory: An extended definition . Front Psychol . 2019;10:2523. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02523

Short-Term Memory In Psychology: Types, Duration & Capacity

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Short-term memory is a component of memory that holds a small amount of information in an active, readily available state for a brief period, typically a few seconds to a minute. The duration of STM seems to be between 15 and 30 seconds, and STM’s capacity is limited, often thought to be about 7±2 items.

It’s often likened to the brain’s “working space,” enabling tasks like reasoning and language comprehension. Information not rehearsed or processed can quickly be forgotten.

Short-term memory (STM) is the second stage of the multi-store memory model proposed by Atkinson-Shiffrin.

Short-term memory has three key aspects:

- Limited capacity (only about 7 items can be stored at a time)

- Limited duration (storage is very fragile, and information can be lost with distraction or the passage of time)

- Encoding (primarily acoustic, even translating visual information into sounds).

Capacity: Magic Number 7

The capacity of short-term memory is limited. A classic theory proposed by George Miller (1956) suggests that the average number of objects an individual can hold in their short-term memory is about seven (plus or minus 2 items).

Miller thought that short-term memory could hold 7 (plus or minus 2 items) because it only had a certain number of “slots” to store items.

However, Miller didn’t specify how much information can be held in each slot. Indeed, if we can “chunk” information together, we can store much more information in our short-term memory.

Miller’s theory is supported by evidence from various studies, such as Jacobs (1887). He used the digit span test with every letter in the alphabet and numbers apart from “w” and “7” because they had two syllables.

He found out that people find it easier to recall numbers rather than letters. The average span for letters was 7.3, and for numbers, it was 9.3.

However, the nature of the items (e.g., simple versus complex) and individual differences can influence this capacity.

It’s also worth noting that techniques like chunking can help increase the effective capacity by grouping individual pieces of information into larger units.

Short-term memory typically holds information for about 15 to 30 seconds. However, the duration can be extended through rehearsal (repeating the information).

The duration of short-term memory seems to be between 15 and 30 seconds, according to Atkinson and Shiffrin (1971). Items can be kept in short-term memory by repeating them verbally (acoustic encoding), a process known as rehearsal.

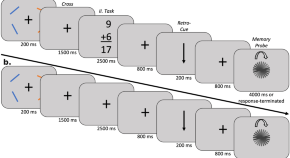

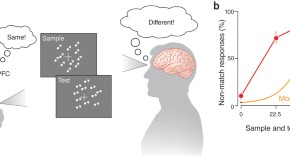

Using a technique called the Brown-Peterson technique, which prevents the possibility of retrieval by having participants count backward in 3s.

Peterson and Peterson (1959) showed that the longer the delay, the less information is recalled. The rapid loss of information from memory when rehearsal is prevented indicates short-term memory having a limited duration.

If not rehearsed or encoded into long-term memory, the information in short-term memory is susceptible to interference and decay, causing it to be forgotten.

It’s important to note that short-term memory duration can vary among individuals and can be influenced by factors like attention, distraction, and the nature of the information.

Encoding in short-term memory primarily involves a transient representation of information, usually based on the sensory attributes of the input . Here’s a breakdown of how encoding works for short-term memory:

- Acoustic Encoding: This is the most common form of encoding in short-term memory. Information, especially verbal information, is often stored based on its sound. This is why, when trying to remember a phone number, you might repeat it aloud or “hear” it in your mind.

- Visual Encoding: Visual encoding is the process of storing visual images. For example, if you glance at a picture briefly and then try to recall details about it a few moments later, you’re relying on visual encoding.

- Semantic Encoding: This involves processing the meaning of information. Although it plays a more dominant role in long-term memory encoding, there are short-term tasks where meaning can influence memory (e.g., remembering words that form a coherent sentence vs. a random list).

- Tactile Encoding: Information can also be encoded based on touch, though this is less common than acoustic or visual encoding for short-term memory tasks.

Various factors, including attention, repetition, and the nature of the information, can influence the effectiveness of encoding in short-term memory.

However, without further processing, the data held in short-term memory can decay or be displaced, emphasizing the transient nature of this memory store.

More durable and elaborate encoding methods, such as deep processing or the formation of associations, are needed to move information from short-term to long-term memory.

Working memory

Baddeley and Hitch (1974) have developed an alternative model of short-term memory, which they call working memory .

Short-term memory and working memory are not the same, although they are closely related concepts. Short-term memory refers to the temporary storage of information, holding it for a brief period of time.

Working memory, on the other hand, involves not just storing, but also manipulating and processing this information. It’s like the brain’s “workspace” for cognitive tasks, such as problem-solving, reasoning, and comprehension.

Working memory is a more dynamic and complex system than mere short-term storage.

Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1971). The control processes of short-term memory . Institute for Mathematical Studies in the Social Sciences, Stanford University.

Baddeley, A.D., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. In G.H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory (Vol. 8, pp. 47–89). New York: Academic Press.

Miller, G. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. The psychological review , 63, 81-97.

Peterson, L. R., & Peterson, M. J. (1959). Short-term retention of individual verbal items. Journal of experimental psychology , 58(3), 193-198.

Related Articles

Eidetic Memory Vs. Photographic Memory

Anterograde Amnesia In Psychology: Definition & Examples

Context and State-Dependent Memory

Declarative Memory In Psychology

Episodic Memory: Definition & Examples

False Memory In Psychology: Examples & More

Everything you need to know about short-term memory

Checked : Soha K. , Vallary O.

Latest Update 20 Jan, 2024

10 min read

Table of content

What is Short term memory?

Mechanism of short-term memory, how does short-term memory work anyway, the role of short term memory, functions of short term memory, differences between short term memory and long term memory, the recency effect and the primacy effect:, what to remember from short term memory:, short term memory problems, loss of short term memory, train your short-term memory.

Do you know that there are several types of memory? Today, we will have a look at short-term memory. We will focus on how it works and on the link between short-term memory and long-term memory. Short-term memory is the memory we all use to recall information in a short time. It is, by nature, limited. For example, the average length of time information is retained in short-term memory is 30 seconds. The number of elements that we can "store" simultaneously is also limited: it is seven elements +/- 2. This is called the memory span. Here’s everything you need to know about short term memory.

Short term memory is also called immediate memory; it operates for a maximum of 30 seconds. It kicks in when a stimulus presents itself, just before it is stored in long-term memory. It is difficult to distinguish where working memory ends, and short-term memory begins. The latter includes verbal and visual memories. Used to manage daily activities, it is a good indicator of alertness and learning abilities. Short-term memories are stored briefly in the parietal lobes, and the neurotransmitter involved being acetylcholine.

According to the model of Atkinson-Shiffrin (1968), it is made up of several elements:

Its first component is sensory memory. When we talk about the short-term memory, its detention period varies between one hundred milliseconds and 2 seconds. Nevertheless, it allows us to keep faithfully information gathered by one of our senses (smell, hearing, sight, touch). Sensory memory is very busy, but it is difficult to access its information, particularly because of the very short retention period.

If the information is selected, it goes into short-term memory. The information retention time is 30 seconds. If used, it can be repeated to keep it in memory longer.

Finally, when information is useful and repeated, it can be transferred to long-term memory. The information is then kept for a very long time.

What information ends up in short-term memory depends on the content. If information is important to you because it interests you, affects you personally, or is emotionally charged, it moves on to your short-term memory. Only when you have learned something seven times does the information arrive in long-term memory. It's quite normal that we don't remember every detail. Short-term memory erases 90% of the information stored. After all, it is not necessary to know years later that you had a pizza with pizza hut on April 2nd, 2018 at 12 noon. On average, the brain deleted irrelevant data after just 18 seconds. Several brain areas interact with each other so that you can remember details. You can actively train this interaction and thus improve a poor short-term memory.

Our short-term memory is one of the four major areas of the brain. In fact, it consists not of just one memory, but of a whole group of memories that are all strongly interlinked. And it has to be because, without the many cognitive skills that our short-term memory gives us, we would not be able to survive.

Our short-term memory has many functions. In the last few decades, it has been established that our short-term memory not only stores and retrieves some information, but is actually one of the most important areas in our brain.

Nowadays, short-term memory is mainly called working memory, and it is responsible for the reception and processing of all information and stimuli that we are exposed to. That means all skills like:

- concentration

And much more are all taken over by our short-term memory. Unfortunately, despite its many tasks, our short-term memory only has a relatively small capacity. This is because, in the past, our brain only had to focus on relatively few things at the same time.

Short-term memory differs from long-term memory in several ways. The first concerns its ability to memorize information. In fact, it is limited in retention time and in its capacity for memorization, unlike long term memory, which is described as almost unlimited memory. And the difference does not end there.

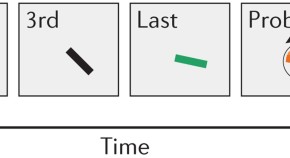

The recency effect refers to the ease of recalling the last items in a list of stimuli. At the same time, the primacy effect expresses the ease of recalling the first elements of a list of stimuli.

To show these effects, scientists have developed an experiment. It consists of teaching a list of words to a subject and asking him to recall this list. Scientists have been able to demonstrate the existence of the effect of recency and primacy when the subject is asked to repeat the words directly after the memorization work. Conversely, the recency effect disappears if the subject waits 30 seconds before returning the list of words.

The researchers concluded that the recency effect was linked to short-term memory. In addition, the primacy effect is intact because the information is already encoded in short-term and then long-term memory. This shows that the primacy effect is related to long term memory.

- Short-term memory has a limited capacity. Its memory span is 7 +/- 2 elements. Its duration is approximately 30 seconds.

- The information stored spend of a sensory memory to the short term memory, and possibly long-term memory

- It is therefore interesting to learn to focus your attention on a limited number of elements at a time to improve the efficiency of memorization. This is why mnemonics are effective, as are advanced memorization tools such as the Mental Palace.

Short-term memory ensures attention and concentration in everyday life. Sometimes the short-term memory does not filter properly so that important learning material is also classified as "unimportant" and does not make its way into long-term memory.

However, if you keep getting things wrong and can no longer remember where they are, and if you regularly forget topics or names, your short-term memory is likely to deteriorate. People who are forgetful or bumbling worry that they may have a bad memory - especially the fear of dementia and Alzheimer's disease increases with age. However, it is normal for short-term memory to deteriorate with age.

Some people fear short-term memory loss. Those affected cannot then take in and evaluate new memories. This means an enormous restriction in everyday life, under which communication with fellow human beings and orientation suffers. Short-term memory loss can be caused by brain disease, dementia, infection, or a stroke.

We Will Write an Essay for You Quickly

It is normal for memory to weaken with age. You can improve your short-term memory with specific exercises. Memory training creates new neural networks in the brain. This improves not only short-term memory but also all other cognitive skills such as:

- Logical thinking

- Understanding of language

Since nowadays everything can be looked up and checked due to smartphones immediately, this impairs the ability to memorize things. But what can you do yourself? With small brain jogging units, you challenge your short-term memory and keep yourself mentally fit. Possibilities are:

- Memorize phone numbers

- Go shopping without a memo

- Spelling difficult words correctly

- Learn the multiplication tables by heart

You can also use special memory exercise programs or solve brain teasers. A healthy lifestyle with good nutrition and regular exercise can also have positive effects on brain performance.

Sperling et al. wanted to prove the existence of sensory memory. For that, they developed an experiment which consists of placing an individual in front of a matrix of 3 X 3 letters. The image is broadcast for 1/20 of a second. The goal is for the individual to find the nine letters. Subject results were approximately 4 to 5 letters found.

Several causes are possible at this stage. Indeed, it is possible that the subjects did not have time to see all the letters, and it is as much possible that they did not manage to memorize everything.

The experience becomes more interesting when the researchers decided to add an element. Right after the image disappears, the researchers play sound called stimuli that can have multiple tones. Each tone represents a row of the matrix. The high tone designates the top line, the middle tone, the middle line etc. The objective of the individual is to transcribe the line expressed by the sound. The results of this new experiment show that the subjects systematically give the correct answer.

This effectively proves that there is indeed a sensory memory because once the matrix is encoded; it remains in visual space for a few seconds. It is the stimuli that will indicate where the subject's attention should be. The conclusion of this study shows that when we have a visual stimulus, it persists a few seconds after its disappearance.

Looking for a Skilled Essay Writer?

- University of South Florida Master of Arts (MA), Humanities

No reviews yet, be the first to write your comment

Write your review

Thanks for review.

It will be published after moderation

Latest News

What happens in the brain when learning?

20 Jan, 2024

How Relativism Promotes Pluralism and Tolerance

How to use the audience’s feedback to write a news report

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

fa51e2b1dc8cca8f7467da564e77b5ea

- Make a Gift

- Join Our Email List

- How Memory Works

Memory is the ongoing process of information retention over time. Because it makes up the very framework through which we make sense of and take action within the present, its importance goes without saying. But how exactly does it work? And how can teachers apply a better understanding of its inner workings to their own teaching? In light of current research in cognitive science, the very, very short answer to these questions is that memory operates according to a "dual-process," where more unconscious, more routine thought processes (known as "System 1") interact with more conscious, more problem-based thought processes (known as "System 2"). At each of these two levels, in turn, there are the processes through which we "get information in" (encoding), how we hold on to it (storage), and and how we "get it back out" (retrieval or recall). With a basic understanding of how these elements of memory work together, teachers can maximize student learning by knowing how much new information to introduce, when to introduce it, and how to sequence assignments that will both reinforce the retention of facts (System 1) and build toward critical, creative thinking (System 2).

Dual-Process Theory

Think back to a time when you learned a new skill, such as driving a car, riding a bicycle, or reading. When you first learned this skill, performing it was an active process in which you analyzed and were acutely aware of every movement you made. Part of this analytical process also meant that you thought carefully about why you were doing what you were doing, to understand how these individual steps fit together as a comprehensive whole. However, as your ability improved, performing the skill stopped being a cognitively-demanding process, instead becoming more intuitive. As you continue to master the skill, you can perform other, at times more intellectually-demanding, tasks simultaneously. Due to your knowledge of this skill or process being unconscious, you could, for example, solve an unrelated complex problem or make an analytical decision while completing it.

In its simplest form, the scenario above is an example of what psychologists call dual-process theory. The term “dual-process” refers to the idea that some behaviors and cognitive processes (such as decision-making) are the products of two distinct cognitive processes, often called System 1 and System 2 (Kaufmann, 2011:443-445). While System 1 is characterized by automatic, unconscious thought, System 2 is characterized by effortful, analytical, intentional thought (Osman, 2004:989).

Dual-Process Theories and Learning

How do System 1 and System 2 thinking relate to teaching and learning? In an educational context, System 1 is associated with memorization and recall of information, while System 2 describes more analytical or critical thinking. Memory and recall, as a part of System 1 cognition, are focused on in the rest of these notes.

As mentioned above, System 1 is characterized by its fast, unconscious recall of previously-memorized information. Classroom activities that would draw heavily on System 1 include memorized multiplication tables, as well as multiple-choice exam questions that only need exact regurgitation from a source such as a textbook. These kinds of tasks do not require students to actively analyze what is being asked of them beyond reiterating memorized material. System 2 thinking becomes necessary when students are presented with activities and assignments that require them to provide a novel solution to a problem, engage in critical thinking, or apply a concept outside of the domain in which it was originally presented.

It may be tempting to think of learning beyond the primary school level as being all about System 2, all the time. However, it’s important to keep in mind that successful System 2 thinking depends on a lot of System 1 thinking to operate. In other words, critical thinking requires a lot of memorized knowledge and intuitive, automatic judgments to be performed quickly and accurately.

How does Memory Work?

In its simplest form, memory refers to the continued process of information retention over time. It is an integral part of human cognition, since it allows individuals to recall and draw upon past events to frame their understanding of and behavior within the present. Memory also gives individuals a framework through which to make sense of the present and future. As such, memory plays a crucial role in teaching and learning. There are three main processes that characterize how memory works. These processes are encoding, storage, and retrieval (or recall).

- Encoding . Encoding refers to the process through which information is learned. That is, how information is taken in, understood, and altered to better support storage (which you will look at in Section 3.1.2). Information is usually encoded through one (or more) of four methods: (1) Visual encoding (how something looks); (2) acoustic encoding (how something sounds); (3) semantic encoding (what something means); and (4) tactile encoding (how something feels). While information typically enters the memory system through one of these modes, the form in which this information is stored may differ from its original, encoded form (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014).

- Retrieval . As indicated above, retrieval is the process through which individuals access stored information. Due to their differences, information stored in STM and LTM are retrieved differently. While STM is retrieved in the order in which it is stored (for example, a sequential list of numbers), LTM is retrieved through association (for example, remembering where you parked your car by returning to the entrance through which you accessed a shopping mall) (Roediger & McDermott, 1995).

Improving Recall

Retrieval is subject to error, because it can reflect a reconstruction of memory. This reconstruction becomes necessary when stored information is lost over time due to decayed retention. In 1885, Hermann Ebbinghaus conducted an experiment in which he tested how well individuals remembered a list of nonsense syllables over increasingly longer periods of time. Using the results of his experiment, he created what is now known as the “Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve” (Schaefer, 2015).

Through his research, Ebbinghaus concluded that the rate at which your memory (of recently learned information) decays depends both on the time that has elapsed following your learning experience as well as how strong your memory is. Some degree of memory decay is inevitable, so, as an educator, how do you reduce the scope of this memory loss? The following sections answer this question by looking at how to improve recall within a learning environment, through various teaching and learning techniques.

As a teacher, it is important to be aware of techniques that you can use to promote better retention and recall among your students. Three such techniques are the testing effect, spacing, and interleaving.

- The testing effect . In most traditional educational settings, tests are normally considered to be a method of periodic but infrequent assessment that can help a teacher understand how well their students have learned the material at hand. However, modern research in psychology suggests that frequent, small tests are also one of the best ways to learn in the first place. The testing effect refers to the process of actively and frequently testing memory retention when learning new information. By encouraging students to regularly recall information they have recently learned, you are helping them to retain that information in long-term memory, which they can draw upon at a later stage of the learning experience (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014). As secondary benefits, frequent testing allows both the teacher and the student to keep track of what a student has learned about a topic, and what they need to revise for retention purposes. Frequent testing can occur at any point in the learning process. For example, at the end of a lecture or seminar, you could give your students a brief, low-stakes quiz or free-response question asking them to remember what they learned that day, or the day before. This kind of quiz will not just tell you what your students are retaining, but will help them remember more than they would have otherwise.

- Spacing. According to the spacing effect, when a student repeatedly learns and recalls information over a prolonged time span, they are more likely to retain that information. This is compared to learning (and attempting to retain) information in a short time span (for example, studying the day before an exam). As a teacher, you can foster this approach to studying in your students by structuring your learning experiences in the same way. For example, instead of introducing a new topic and its related concepts to students in one go, you can cover the topic in segments over multiple lessons (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014).

- Interleaving. The interleaving technique is another teaching and learning approach that was introduced as an alternative to a technique known as “blocking”. Blocking refers to when a student practices one skill or one topic at a time. Interleaving, on the other hand, is when students practice multiple related skills in the same session. This technique has proven to be more successful than the traditional blocking technique in various fields (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014).

As useful as it is to know which techniques you can use, as a teacher, to improve student recall of information, it is also crucial for students to be aware of techniques they can use to improve their own recall. This section looks at four of these techniques: state-dependent memory, schemas, chunking, and deliberate practice.

- State-dependent memory . State-dependent memory refers to the idea that being in the same state in which you first learned information enables you to better remember said information. In this instance, “state” refers to an individual’s surroundings, as well as their mental and physical state at the time of learning (Weissenborn & Duka, 2000).

- Schemas. Schemas refer to the mental frameworks an individual creates to help them understand and organize new information. Schemas act as a cognitive “shortcut” in that they allow individuals to interpret new information quicker than when not using schemas. However, schemas may also prevent individuals from learning pertinent information that falls outside the scope of the schema that has been created. It is because of this that students should be encouraged to alter or reanalyze their schemas, when necessary, when they learn important information that may not confirm or align with their existing beliefs and conceptions of a topic.

- Chunking. Chunking is the process of grouping pieces of information together to better facilitate retention. Instead of recalling each piece individually, individuals recall the entire group, and then can retrieve each item from that group more easily (Gobet et al., 2001).

- Deliberate practice. The final technique that students can use to improve recall is deliberate practice. Simply put, deliberate practice refers to the act of deliberately and actively practicing a skill with the intention of improving understanding of and performance in said skill. By encouraging students to practice a skill continually and deliberately (for example, writing a well-structured essay), you will ensure better retention of that skill (Brown et al., 2014).

For more information...

Brown, P.C., Roediger, H.L. & McDaniel, M.A. 2014. Make it stick: The science of successful learning . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gobet, F., Lane, P.C., Croker, S., Cheng, P.C., Jones, G., Oliver, I. & Pine, J.M. 2001. Chunking mechanisms in human learning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences . 5(6):236-243.

Kaufman, S.B. 2011. Intelligence and the cognitive unconscious. In The Cambridge handbook of intelligence . R.J. Sternberg & S.B. Kaufman, Eds. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Osman, M. 2004. An evaluation of dual-process theories of reasoning. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review . 11(6):988-1010.

Roediger, H.L. & McDermott, K.B. 1995. Creating false memories: Remembering words not presented in lists. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition . 21(4):803.

Schaefer, P. 2015. Why Google has forever changed the forgetting curve at work.

Weissenborn, R. & Duka, T. 2000. State-dependent effects of alcohol on explicit memory: The role of semantic associations. Psychopharmacology . 149(1):98-106.

- Designing Your Course

- In the Classroom

- Getting Feedback

- Equitable & Inclusive Teaching

- Advising and Mentoring

- Teaching and Your Career

- Teaching Remotely

- Tools and Platforms

- Comprehending and Communicating Knowledge

- Motivation and Metacognition

- Promoting Engagement

- Bok Publications

- Other Resources Around Campus

Types of Memory

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

A person’s memory is a sea of images and other sensory impressions, facts and meanings, echoes of past feelings, and ingrained codes for how to behave—a diverse well of information. Naturally, there are many ways (some experts suggest there are hundreds) to describe the varieties of what people remember and how. While the different brands of memory are not always described in exactly the same way by memory researchers, some key concepts have emerged.

These forms of memory, which can overlap in daily life, have also been arranged into broad categories. Memory that lingers for a moment (or even less than a second) could be described as short-term memory , while any kind of information that is preserved for remembering at a later point can be called long-term memory . Memory experts have also distinguished explicit memory , in which information is consciously recalled, from implicit memory , the use of saved information without conscious awareness that it’s being recalled.

On This Page

- Episodic Memory

- Semantic Memory

- Procedural Memory

- Short-Term Memory and Working Memory

- Sensory Memory

- Prospective Memory

When a person recalls a particular event (or “episode”) experienced in the past, that is episodic memory . This kind of long-term memory brings to attention details about anything from what one ate for breakfast to the emotions that were stirred up during a serious conversation with a romantic partner. The experiences conjured by episodic memory can be very recent or decades-old.

A related concept is autobiographical memory , which is the memory of information that forms part of a person’s life story. However, while autobiographical memory includes memories of events in one’s life (such as one’s sixteenth birthday party), it can also encompass facts (such as one’s birth date) and other non-episodic forms of information.

• The details of a phone call you had 20 minutes ago

• How you felt during your last argument

• What it was like receiving your high-school diploma

Semantic memory is someone’s long-term store of knowledge: It’s composed of pieces of information such as facts learned in school, what concepts mean and how they are related, or the definition of a particular word. The details that make up semantic memory can correspond to other forms of memory. One may remember factual details about a party, for instance—what time it started, at whose house it took place, how many people were there, all part of semantic memory—in addition to recalling the sounds heard and excitement felt. But semantic memory can also include facts and meanings related to people, places, or things one has no direct relation to.

• What year it currently is

• The capital of a foreign country

• The meaning of a slang term

Sitting on a bike after not riding one for years and recalling just what to do is a quintessential example of procedural memory . The term describes long-term memory for how to do things, both physical and mental, and is involved in the process of learning skills—from the basic ones people take for granted to those that require considerable practice. A related term is kinesthetic memory , which refers specifically to memory for physical behaviors.

• How to tie your shoes

• How to send an email

• How to shoot a basketball

The terms short-term memory and working memory are sometimes used interchangeably, and both refer to storage of information for a brief amount of time. Working memory can be distinguished from general short-term memory, however, in that working memory specifically involves the temporary storage of information that is being mentally manipulated.

Short-term memory is used when, for instance, the name of a new acquaintance, a statistic, or some other detail is consciously processed and retained for at least a short period of time. It may then be saved in long-term memory, or it may be forgotten within minutes. With working memory , information—the preceding words in a sentence one is reading, for example—is held in mind so that it can be used in the moment.

• The appearance of someone you met a minute ago

• The current temperature, immediately after looking it up

• What happened moments ago in a movie

• A number you have calculated as part of a mental math problem

• The person named at the beginning of a sentence

• Holding a concept in mind (such as ball ) and combining it with another ( orange )

Sensory memories are what psychologists call the short-term memories of just-experienced sensory stimuli such as sights and sounds. The brief memory of something just seen has been called iconic memory, while the sound-based equivalent is called echoic memory. Additional forms of short-term sensory memory are thought to exist for the other senses as well.

Sense-related memories, of course, can also be preserved long-term. Visual-spatial memory refers to memory of how objects are organized in space—tapped when a person remembers which way to walk to get to the grocery store. Auditory memory , olfactory memory , and haptic memory are terms for stored sensory impressions of sounds, smells, and skin sensations, respectively.

• The sound of a piano note that was just played

• The appearance of a car that drove by

• The smell of a restaurant you passed

Prospective memory is forward-thinking memory: It means recalling an intention from the past in order to do something in the future. It is essential for daily functioning, in that memories of previous intentions, including very recent ones, ensure that people execute their plans and meet their obligations when the intended behaviors can’t be carried out right away, or have to be carried out routinely.

• To call someone back

• To stop at the drugstore on the way home

• To pay the rent every month

Why is it easier to recall lyrics to a song than to memorize a poem? The answer is music.

A few studies have suggested that recalling the past with fondness and gratitude can increase self-control, but a recent meta-analysis challenges this idea.

It remains a matter of scientific debate whether the beta amyloid buildup is the cause of Alzheimer’s or a feature of it. It’s time to look at “out of the clump” fresh approaches.

Researchers developed a method to transform students' writing over 30 years ago. What happened to it?

The evidence strongly points to the perils of long-term use of benzos. This warning is more credible after recent studies have revealed the mechanisms of cognitive impairments.

Has your loved one told you something happened that you’re not sure is true? It could be a false memory.

Older U.S. adults and their families have reason to consider space and place for optimizing older adults' short term memory and attentional needs.

We all grow up with stories about our parents, childhood, and challenges. They form our unique way of looking at life and ourselves, but stories can be distorted. Time to upgrade?

It may require very little daily cannabis consumption to produce long-term neuroprotection in the older brain.

The phenomenon is known as the Zeigarnik Effect.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

25 Short-Term Memory Examples

Short-term memory refers to the temporary storage of information that is currently being processed or used.

Short-term memory has two main components:

- limited capacity: A famous study by Miller (1956) found that it can only contain 7 items at once (plus or minus two).

- limited duration: We tend to be able to hold items in our short-term memory for about 15-30 seconds (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1971) unless we continually rehearse it using a process called maintenance rehearsal .

Despite its short duration, short-term memory has undeniable benefits. It aids in daily tasks, such as recalling a phone number momentarily or following directions. It also plays a vital role in cognitive abilities like reading and problem-solving (Eysenck & Keane, 2020).

There are 6 types of short-term memory , including auditory, visual, spatial, tactile, olfactory, and gustagory.

Short-Term Memory Examples

1. Remembering a Phone Number If someone tells you a phone number, you use your short-term memory to recall it long enough to dial it. It’s a perfect demonstration of short-term memory in action, as the number usually fades from your memory shortly after you’ve dialed it, unless it’s committed to long-term memory through repeated use or memorization methods like mnemonics, the chunking method , memory linking or the peg word system .

2. Following Directions When you read or hear instructions and then follow them, you are utilizing your short-term memory. You keep those details in your mind just long enough to complete the task. If you’ve ever assembled furniture from a manual or followed a recipe, you’ve made excellent use of your short-term memory. A good way to commit directions from short-term to long-term memory is to use the method of loci method .

3. Listening to a Lecture When you attend a seminar or lecture, your short-term memory allows you to process and understand the information presented in real-time. It allows you to maintain a mental “thread” of the conversational context, which is essential for comprehending the full message. Because you need to remember this information longer, you need to use a method such as note-taking or rote memorization to help to convert the information to long-term memory.

4. Playing Games Many games, both mental and physical, tap into short-term memory. Whether it’s recalling the sequence of colors, remembering the last move your opponent made at chess, or memorizing the cards played in a hand of bridge, games often require the use of short-term memory to succeed. This can help you to get an advantage on your competitors. Some people have mastered this skill, such as card counters, who can have a great advantage in gameplay.

5. Reading a Book If you’re engrossed in a novel, your short-term memory is working hard. It allows you to remember the start of a sentence when you reach the end, keeps track of the various characters, and enables you to follow the plot. Without short-term memory, reading would be a much more challenging and less enjoyable pursuit. Generally, paragraphs are written so that they contain one ‘chunk’ of information, enough to keep in short-term memory, but if a paragraph gets too long, your short-term memory starts to fail, and you lose your spot in the book.

6. Taking Notes Taking notes during a lecture or a meeting utilizes your short-term memory to retain information long enough to record it. Remembering points long enough to jot them down in condensed form facilitates auditory and visual learning . It also helps translate larger information chunks into manageable bits, boosting your understanding and retention of the topic. In addition, note-taking also aids in enhancing organizational skills .

7. Multiplication and Division When working on multiplication or division problems, especially those involving several digits, you use short-term memory. You must retain the carryover number in your mind as you proceed to the next calculation step. Additionally, you have to remember the original problem and the steps you’ve already completed. This active engagement enhances your computational skills and overall numeracy.

8. Recalling Recent Events When remembering recent events, like the breakfast menu or conversations from a few hours back, your short-term memory comes into play. It temporarily stores recent experiences for quick recall. Interestingly, the human brain tends to favor short-term memories with emotional connections, hence why you might remember a stimulating conversation more than a mundane one. These fleeting memories constitute a significant portion of our daily cognitive activities.

9. Mental Grocery Lists Making mental grocery lists is a demonstration of short-term memory. Remembering a handful of items long enough to grab them from the store can be challenging, yet it’s a task we often perform. This act of attempting to retain and retrieve data in a short span promotes mental agility. Plus, it shows us how effectively we can use short-term memory in our day-to-day routines.

10. Learning a New Language In the process of language acquisition, short-term memory plays a critical role. Retaining new vocabulary words and fresh grammar rules in your mind helps in speaking, writing, or understanding a new language. Your short-term memory allows you to juggle this new information in the context of a conversation. In essence, it’s an indispensable tool in the challenging yet rewarding journey of language learning.

11. Remembering Passwords and PINs Your short-term memory is instrumental when it comes to remembering passwords or PIN numbers momentarily. You recall them just long enough to unlock a device or complete a transaction. This temporary retention highlights the role of short-term memory in safeguarding personal information. However, over-reliance on it for password recall can lead to forgetfulness, hence the need for unique, memorable, yet secure passphrases.

12. Completing Puzzles When you complete a puzzle, be it a Sudoku or crosswords, you’re actively using your short-term memory. You have to remember previously noted numbers or words to fill out the remaining spaces correctly. This activity not only strengthens short-term memory but also harnesses analytical and problem-solving skills, making it a great cognitive exercise.

13. Cooking a New Recipe When you’re trying out a new recipe, your short-term memory plays a significant part. You have to remember each ingredient and the sequence in which they’re added, often while multitasking with various cooking processes. This process reinforces the link between short-term memory and task execution, and it shows how effective information recall aids in real-life skills like cooking.

14. Remembering Dates and Appointments Your short-term memory helps you recall the dates and times of appointments in the near future. Until you write them down or enter them into a digital calendar, this information is held in your short-term memory. This aspect emphasizes the supportive role of short-term memory in managing our time and daily schedules efficiently, contributing to personal organization and responsibility.

15. Learning to Play a Musical Instrument When learning to play a new musical instrument, short-term memory is heavily relied on. It allows you to remember scales, notes, and sequences that you need to play a piece of music. You often need to store information in short-term memory to know seconds in advance where to move your hands next. This use of memory doesn’t just cultivate musical skills, but it also enhances mental flexibility and cognitive strength, thus contributing to broader personal development.

16. Memorizing Steps to a Dance Routine When you begin learning a new dance routine, your short-term memory is put to the test. It’s the temporary storage that keeps the choreography steps in check before they become ingrained through practice and repetition to a part of long-term memory. The ability to remember and execute these movements in sequence also helps improve bodily coordination and rhythm. Furthermore, as patterns become more complex and additional steps are added, you begin to stretch the capacity of this memory system. Consequently, this process aids in enhancing cognitive abilities, kindling creativity, and fostering the self-discipline needed to master an art form.

17. Recognizing Faces in a Crowd Your short-term memory comes into play when you’re scanning a crowd to recognize a familiar face. The mind briefly stores the image of the person you’re seeking, comparing it against the multitude of faces in the crowd. This complex task not only involves visual perception but also quick memory retrieval, underlining how essential short-term memory is in everyday situations. It is this cognitive function that enables us to pick a friend’s face out of a crowd or identify a known face amongst strangers. Beyond social recognition, it’s a testament to human adaptability and survival instincts in navigation through social environments .

18. Calculating Tips in Your Head When you’re figuring out a tip at a restaurant or cafe, you’re putting your short-term memory to work. You need to remember the total bill amount for a short while in order to perform the percentage calculation accurately. This math-on-the-fly showcases the use of short-term memory in real-world financial decision-making. It’s a simple task which underscores short-term memory’s utility in basic everyday arithmetic, financial judgment, and quick decision-making . Moreover, it reflects the practical role our cognitive abilities play in social etiquette and norms.

19. Recalling Product Details While Shopping While shopping, particularly for complex items or major purchases, your short-term memory becomes vital. You might need to remember the details of various products, including specifications, prices, and brands, to make a comparative and informed choice. This information, often discussed or read minutes to hours before, is held in the short-term memory for quick access. Rendered as a consumer tool, this memory function aids in making the right choice to maximize satisfaction and value for money. The process underscores the crucial role that short-term memory plays in decision-making, consumer behavior, and savvy resource management.

20. Remembering Names in an Introduction Your short-term memory is actively engaged when you’re introduced to new people at a social event or professional gathering. You need to remember names and associate them with faces almost immediately after the introduction. The need to recall this data moments after hearing it underscores the function of short-term memory in social interactions and networking. It’s a perfect illustration of its role in maintaining social cohesion . In essence, this ability enhances social communication, impacts human interaction, and can significantly influence professional relationships when nurtured well.

21. Memorizing Lines for a Presentation When preparing for a presentation or public speaking engagement, your short-term memory is key. You need to remember key points, quotes, and any specific phrasing that you plan to use. In the short period before you present, these lines are held in your short-term memory, ready to be retrieved. This utilization of short-term memory explains how speakers manage to deliver speeches without always resorting to written notes. Thus, it’s not only inherent in learning and information recall, but also vital in communication and public representation.

22. Recognizing Turn Sequences in a Board Game While engaging in board games, your short-term memory helps to keep track of the sequences and instructions. You need to remember turn orders, game rules, and the actions of other players. This information, stored temporarily, assists in strategizing your next move. Hence, the game of strategy also becomes a test of one’s cognitive ability, displaying the relationship between memory, comprehension, and competitive success. This mental exercise benefits cognitive agility, decision-making, and social interaction in a group setting.

23. Understanding a New Concept in Class When you’re exposed to a new topic in a class or lecture, your short-term memory serves as an essential tool. You need to remember facts, relate them to each other and to prior knowledge, helping compound understanding of the subject matter. This retention of information forms the first step in the journey from learning to long-term memory storage. Highlighting the role of short-term memory in education and knowledge acquisition, it serves as the initial filter in the learning process. Moreover, it underscores how our cognitive functions aid in personal growth, academic achievement, and overall intellectual development .

24. Recalling Tasks in a To-do List Creating and remembering a to-do list for the day is a routine task heavily dependent on short-term memory. Details of each task, their sequence, and priority levels are held in your short-term memory, often until they’re completed or jotted down somewhere. This process emphasizes the practical use of short-term memory in productivity and task management, which is integral to efficient day-to-day functioning. It also helps to cultivate personal organization, discipline, and even stress management by effectively decluttering our mental workspace.

25. Listening to and Responding in a Conversation In any conversation, short-term memory helps to keep track of what’s being said so that we can form appropriate responses. It plays a vital role in understanding the context, recalling related experiences, and keeping pace with the dialogue flow. This function proves how short-term memory is instrumental in social communication, linguistic comprehension, and interpersonal skills . Its role in conversations also enhances our ability to empathize, understand perspectives, and build connections, establishing its significance not just on a cognitive level, but on a socio-emotional plane too.

Short-Term Memory vs Long-Term Memory

We tend to compare short-term memory to long-term memory (LTM). LTM is where we store information that we need to recall well into the future, but in order to convert information from STM to LTM, we need to engage in conscious memorization practices such as rote learning.

There are substantial differences between STM and LTM, such as how much can be stored, how the information is forgotten, where it’s stored in the brain, and the accessibility of the memories.

Below is a table summary of the key differences:

See Also: Examples of Long-Term Memory

Summary of Key Points

- Short-term memory holds about 7 items of information (plus or minus 2).

- It can hold information for about 15-30 seconds.

- It’s contrasted to long-term memory, which can hold infinite items for a potentially infinite amount of time.

- STM is vital for completing daily tasks, such as holding information in our brains during a conversation or while playing games.

- We can prolong the how long a piece of information is kept in STM through strategies such as whispered repetition.

- To commit information from STM to LTM, learning strategies are required, such as spaced repetition.

Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1971). The control processes of short-term memory . Institute for Mathematical Studies in the Social Sciences, Stanford University.

Baddeley, A.D., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. In G.H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory (Vol. 8, pp. 47–89). New York: Academic Press.

Baddeley, A., Eysenck, M. W., & Anderson, A. C. (2009). Memory. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Eysenck, M. W., & Keane, M. T. (2020). Cognitive Psychology: A Student’s Handbook. Taylor & Francis.

García-Rueda, L., Poch, C., & Campo, P. (2022). Forgetting Details in Visual Long-Term Memory: Decay or Interference? Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience , 16 , 887321.

Miller, G. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information . The psychological review , 63, 81-97.

Nairne, J. S., & Neath, I. (2012). Sensory and working memory. In Weiner, I. B. (Ed.). Handbook of Psychology, Experimental Psychology . London: Wiley.

Slotnick, S. (2017). Cognitive Neuroscience of Memory . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Self-Actualization Examples (Maslow's Hierarchy)