Research: What Is American Identity and Why Does It Matter?

Why Does the American Identity Matter?

The most important reason for understanding American identity is related to white racial identification. It may not be prevalent in U.S. political attitudes, but it’s still an issue. A survey from 2012 asked white respondents to indicate if whiteness represented the way they thought of themselves most of the time, as opposed to identifying themselves as Americans . One fifth of the survey’s white respondents said that they preferred the term white to American when identifying themselves.

How to Analyze American Identity

- There’s no such thing as a universal identity, especially for an omni-cultural country such as the USA.

- Everyone has their own understanding of what it means to be American today, as citizens come from different religious, ethnic, ideological, and geographical backgrounds.

- Explaining the concept of American identity calls for an inclusive approach based on solidarity.

- Depending on how you discuss the concept, an academic essay may require arguments on modern-day immigration and immigrant policies. How do they fit within the common understanding of American identity?

Who Are We?

Guest Contributor

The most important good news and events of the day.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receives daily updates direct to your inbox!

Alexandria Gets Another New Mural!

Say hello to the turkish coffee lady, related articles.

Gadsby’s Tavern Museum Society’s Spring Fling Boosts Endowment Fund

Community Supporters to be Honored by Volunteer Alexandria During April 27 Ceremony

Lt. Julia Bucholz, from Alexandria, Serves on The USS Howard

Honoring Gold Star Spouses

- Abortion & Reproductive Health

- Climate Change & Science

- Immigration

- Law & Criminal Justice

- Politics & Elections

- Race & Ethnicity

- Religion & Culture

- Understanding Religion, Partisanship, and Women Voters Ahead of the 2024 Presidential Election

- Family Religious Dynamics and Interfaith Relationships

- Careers and Fellowships

- Current PRRI Public Fellows

- PRRI Public Fellow Alumni

- Partnerships

- Press Coverage

- PRRI Voices

Our current political polarization can feel new, but it has a long cultural history. Two dominant visions of American identity have historically been in tension and at times outright competition with one another: pluralism and exclusion.

On the one hand, the first vision understands the United States as a country built on a commitment to pluralism, where anyone, from anywhere, can be American. As people fled religious persecution, the US as a nation of immigrants provided many a home where diverse religious and political views and backgrounds could co-exist. In this broad sense, the country affirms its society is a land of others. These ideals laid out by the Framers of the Constitution have over the centuries been invoked by groups marginalized by race, religion, and immigrant backgrounds to argue for a more inclusive, representative American democracy.

On the other hand, the exclusionary vision of American society has emphasized that American identity–and all the idealized or normative standards that entails (e.g., race, gender)–is not available to all. Historically, what it means to be American has been exclusively available to white people – white men in particular – with European ancestry , both in how people imagine American identity and how law has enforced boundaries of citizenship. For example, when Asian Americans and Latino Americans made legal claims for citizenship in the 19th and early 20th century, they were forced to argue that they fit either ‘white’ or ‘black’ definitions of citizenship. Both during this period and since, citizenship held by immigrants and/or racialized minorities is insufficient to be considered “American.”

Given this tension between a cultural value for pluralism and narrow notions of American identity, how does the public understand what it means to be “truly American” and are these views changing?

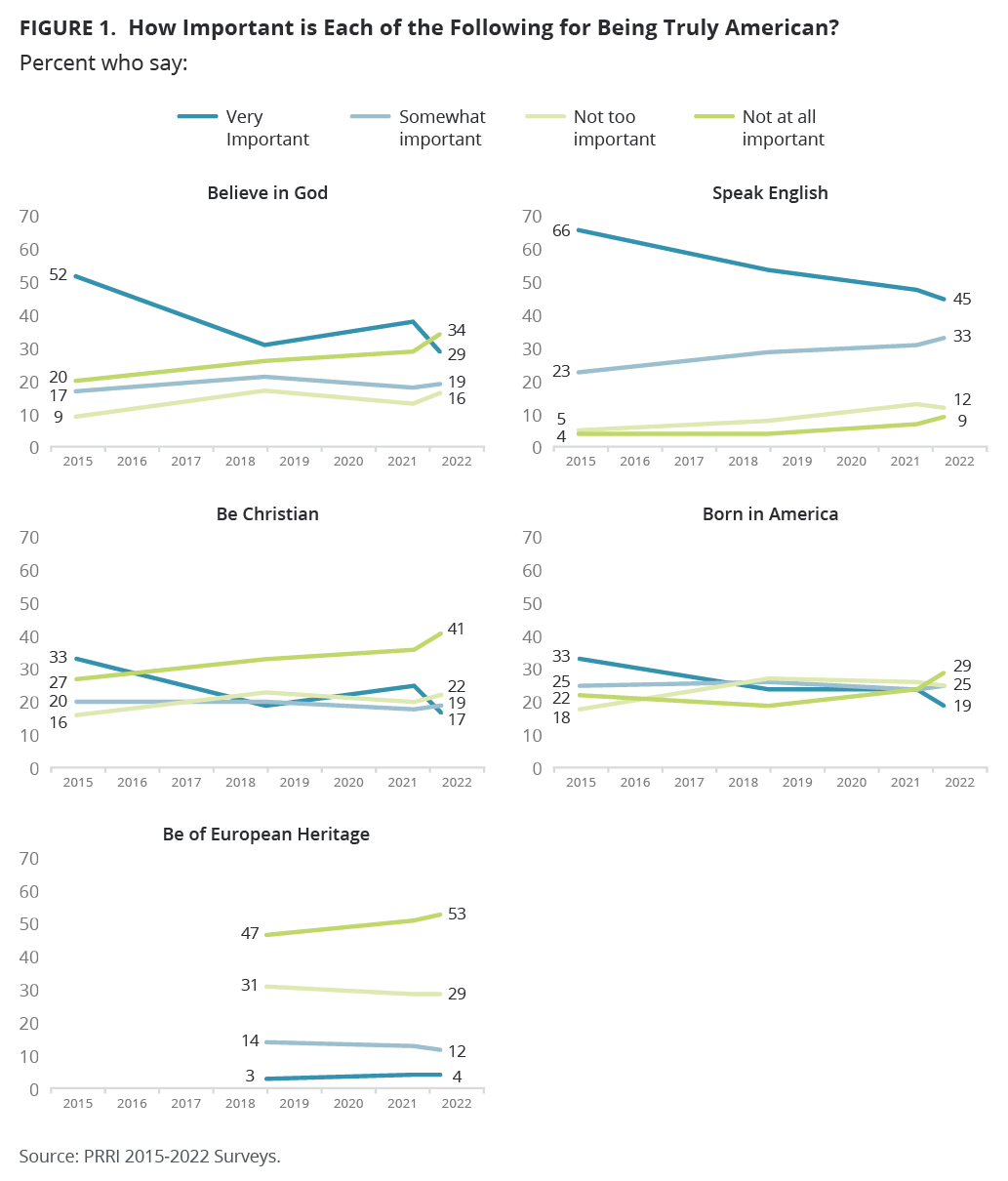

Since 2015, PRRI has asked questions about the hard boundaries of American identity on four occasions. This battery of questions assesses how important the following factors are to being “truly” American: being a Christian, being born in America, being able to speak English, and believing in God. Since 2018, PRRI has included a question about whether being of European heritage is important to being “truly” American.

We examined attitudes about each of these items on a cross-section of Americans in 2015, 2018, 2021, and 2022.

Second, most Americans place the greatest importance on English language skills as the most important factor of the five posed to being truly American, whereas being of European heritage is the least important of the five factors.

Finally, while these trends suggest slight movement toward inclusion, they also show that many people still believe that religious identities and beliefs, language, and place of birth dictate who counts as a true American to some degree. Rates of moderate agreement with these questions are more stable over time.

Together, this snapshot suggests that the tension between the pluralist and exclusionary traditions endure. While the over time trend suggests a move towards a more pluralist vision, the majority of Americans still believe that these hard boundaries of American identity and the exclusionary vision that they support define what it means to be a true American.

Today, some Americans believe that speaking English and holding particular kinds of religious beliefs are central to American identity. These beliefs are tied to citizenship and denied to religious minorities . National political rhetoric often underscores the reality of this vision of America. National identity is regularly invoked in American politics, often to turn public opinion away from progressive immigration policies. Politicians regularly contrast American citizens with immigrants, arguing that their cultures and religions are incompatible with American values and that they will never be “true Americans.” Research also shows that people do not always choose a pluralist or an exclusive vision of American society – their attitudes toward different social groups often combine parts of both visions .

Nazita Lajevardi , Evan Stewart , Roy Whitaker , and Tarah Williams are members of the 2021-2022 cohort of PRRI Public Fellows.

Morning Buzz New Research Research Roundup

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Get New Issue Alerts

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences

What does it mean to be an American?

Sarah Song, a Visiting Scholar at the Academy in 2005–2006, is an assistant professor of law and political science at the University of California, Berkeley, and the author of Justice, Gender, and the Politics of Multiculturalism (2007). She is at work on a book about immigration and citizenship in the United States.

It is often said that being an American means sharing a commitment to a set of values and ideals. 1 Writing about the relationship of ethnicity and American identity, the historian Philip Gleason put it this way:

To be or to become an American, a person did not have to be any particular national, linguistic, religious, or ethnic background. All he had to do was to commit himself to the political ideology centered on the abstract ideals of liberty, equality, and republicanism. Thus the universalist ideological character of American nationality meant that it was open to anyone who willed to become an American. 2

To take the motto of the Great Seal of the United States, E pluribus unum – "From many, one" – in this context suggests not that manyness should be melted down into one, as in Israel Zangwill's image of the melting pot, but that, as the Great Seal's sheaf of arrows suggests, there should be a coexistence of many-in-one under a unified citizenship based on shared ideals.

Of course, the story is not so simple, as Gleason himself went on to note. America's history of racial and ethnic exclusions has undercut the universalist stance; for being an American has also meant sharing a national culture, one largely defined in racial, ethnic, and religious terms. And while solidarity can be understood as "an experience of willed affiliation," some forms of American solidarity have been less inclusive than others, demanding much more than simply the desire to affiliate. 3 In this essay, I explore different ideals of civic solidarity with an eye toward what they imply for newcomers who wish to become American citizens.

Why does civic solidarity matter? First, it is integral to the pursuit of distributive justice. The institutions of the welfare state serve as redistributive mechanisms that can offset the inequalities of life chances that a capitalist economy creates, and they raise the position of the worst-off members of society to a level where they are able to participate as equal citizens. While self-interest alone may motivate people to support social insurance schemes that protect them against unpredictable circumstances, solidarity is understood to be required to support redistribution from the rich to aid the poor, including housing subsidies, income supplements, and long-term unemployment benefits. 4 The underlying idea is that people are more likely to support redistributive schemes when they trust one another, and they are more likely to trust one another when they regard others as like themselves in some meaningful sense.

Second, genuine democracy demands solidarity. If democratic activity involves not just voting, but also deliberation, then people must make an effort to listen to and understand one another. Moreover, they must be willing to moderate their claims in the hope of finding common ground on which to base political decisions. Such democratic activity cannot be realized by individuals pursuing their own interests; it requires some concern for the common good. A sense of solidarity can help foster mutual sympathy and respect, which in turn support citizens' orientation toward the common good.

Third, civic solidarity offers more inclusive alternatives to chauvinist models that often prevail in political life around the world. For example, the alternative to the Nehru-Gandhi secular definition of Indian national identity is the Hindu chauvinism of the Bharatiya Janata Party, not a cosmopolitan model of belonging. "And what in the end can defeat this chauvinism," asks Charles Taylor, "but some reinvention of India as a secular republic with which people can identify?" 5 It is not enough to articulate accounts of solidarity and belonging only at the subnational or transnational levels while ignoring senses of belonging to the political community. One might believe that people have a deep need for belonging in communities, perhaps grounded in even deeper human needs for recognition and freedom, but even those skeptical of such claims might recognize the importance of articulating more inclusive models of political community as an alternative to the racial, ethnic, or religious narratives that have permeated political life. 6 The challenge, then, is to develop a model of civic solidarity that is "thick" enough to motivate support for justice and democracy while also "thin" enough to accommodate racial, ethnic, and religious diversity.

We might look first to Habermas's idea of constitutional patriotism (Verfassungspatriotismus). The idea emerged from a particular national history, to denote attachment to the liberal democratic institutions of the postwar Federal Republic of Germany, but Habermas and others have taken it to be a generalizable vision for liberal democratic societies, as well as for supranational communities such as the European Union. On this view, what binds citizens together is their common allegiance to the ideals embodied in a shared political culture. The only "common denominator for a constitutional patriotism" is that "every citizen be socialized into a common political culture." 7

Habermas points to the United States as a leading example of a multicultural society where constitutional principles have taken root in a political culture without depending on "all citizens' sharing the same language or the same ethnic and cultural origins." 8 The basis of American solidarity is not any particular racial or ethnic identity or religious beliefs, but universal moral ideals embodied in American political culture and set forth in such seminal texts as the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights, Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, and Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech. Based on a minimal commonality of shared ideals, constitutional patriotism is attractive for the agnosticism toward particular moral and religious outlooks and ethnocultural identities to which it aspires.

What does constitutional patriotism suggest for the sort of reception immigrants should receive? There has been a general shift in Western Europe and North America in the standards governing access to citizenship from cultural markers to values, and this is a development that constitutional patriots would applaud. In the United States those seeking to become citizens must demonstrate basic knowledge of U.S. government and history. A newly revised U.S. citizenship test was instituted in October 2008 with the hope that it will serve, in the words of the chief of the Office of Citizenship, Alfonso Aguilar, as "an instrument to promote civic learning and patriotism." 9 The revised test attempts to move away from civics trivia to emphasize political ideas and concepts. (There is still a fair amount of trivia: "How many amendments does the Constitution have?" "What is the capital of your state?") The new test asks more open-ended questions about government powers and political concepts: "What does the judicial branch do?" "What stops one branch of government from becoming too powerful?" "What is freedom of religion?" "What is the 'rule of law'?" 10

Constitutional patriots would endorse this focus on values and principles. In Habermas's view, legal principles are anchored in the "political culture," which he suggests is separable from "ethical-cultural" forms of life. Acknowledging that in many countries the "ethical-cultural" form of life of the majority is "fused" with the "political culture," he argues that the "level of the shared political culture must be uncoupled from the level of subcultures and their prepolitical identities." 11 All that should be expected of immigrants is that they embrace the constitutional principles as interpreted by the political culture, not that they necessarily embrace the majority's ethical-cultural forms.

Yet language is a key aspect of "ethical-cultural" forms of life, shaping people's worldviews and experiences. It is through language that individuals become who they are. Since a political community must conduct its affairs in at least one language, the ethical-cultural and political cannot be completely "uncoupled." As theorists of multiculturalism have stressed, complete separation of state and particularistic identities is impossible; government decisions about the language of public institutions, public holidays, and state symbols unavoidably involve recognizing and supporting particular ethnic and religious groups over others. 12 In the United States, English language ability has been a statutory qualification for naturalization since 1906, originally as a requirement of oral ability and later as a requirement of English literacy. Indeed, support for the principles of the Constitution has been interpreted as requiring English literacy. 13 The language requirement might be justified as a practical matter (we need some language to be the common language of schools, government, and the workplace, so why not the language of the majority?), but for a great many citizens, the language requirement is also viewed as a key marker of national identity. The continuing centrality of language in naturalization policy prevents us from saying that what it means to be an American is purely a matter of shared values.

Another misconception about constitutional patriotism is that it is necessarily more inclusive of newcomers than cultural nationalist models of solidarity. Its inclusiveness depends on which principles are held up as the polity's shared principles, and its normative substance depends on and must be evaluated in light of a background theory of justice, freedom, or democracy; it does not by itself provide such a theory. Consider ideological requirements for naturalization in U.S. history. The first naturalization law of 1790 required nothing more than an oath to support the U.S. Constitution. The second naturalization act added two ideological elements: the renunciation of titles or orders of nobility and the requirement that one be found to have "behaved as a man . . . attached to the principles of the constitution of the United States." 14 This attachment requirement was revised in 1940 from a behavioral qualification to a personal attribute, but this did not help clarify what attachment to constitutional principles requires. 15 Not surprisingly, the "attachment to constitutional principles" requirement has been interpreted as requiring a belief in representative government, federalism, separation of powers, and constitutionally guaranteed individual rights. It has also been interpreted as disqualifying anarchists, polygamists, and conscientious objectors for citizenship. In 1950, support for communism was added to the list of grounds for disqualification from naturalization – as well as grounds for exclusion and deportation. 16 The 1990 Immigration Act retained the McCarthy-era ideological qualifications for naturalization; current law disqualifies those who advocate or affiliate with an organization that advocates communism or opposition to all organized government. 17 Patriotism, like nationalism, is capable of excess and pathology, as evidenced by loyalty oaths and campaigns against "un-American" activities.

In contrast to constitutional patriots, liberal nationalists acknowledge that states cannot be culturally neutral even if they tried. States cannot avoid coercing citizens into preserving a national culture of some kind because state institutions and laws define a political culture, which in turn shapes the range of customs and practices of daily life that constitute a national culture. David Miller, a leading theorist of liberal nationalism, defines national identity according to the following elements: a shared belief among a group of individuals that they belong together, historical continuity stretching across generations, connection to a particular territory, and a shared set of characteristics constituting a national culture. 18 It is not enough to share a common identity rooted in a shared history or a shared territory; a shared national culture is a necessary feature of national identity. I share a national culture with someone, even if we never meet, if each of us has been initiated into the traditions and customs of a national culture.

What sort of content makes up a national culture? Miller says more about what a national culture does not entail. It need not be based on biological descent. Even if nationalist doctrines have historically been based on notions of biological descent and race, Miller emphasizes that sharing a national culture is, in principle, compatible with people belonging to a diversity of racial and ethnic groups. In addition, every member need not have been born in the homeland. Thus, "immigration need not pose problems, provided only that the immigrants come to share a common national identity, to which they may contribute their own distinctive ingredients." 19

Liberal nationalists focus on the idea of culture, as opposed to ethnicity or descent, in order to reconcile nationalism with liberalism. Thicker than constitutional patriotism, liberal nationalism, Miller maintains, is thinner than ethnic models of belonging. Both nationality and ethnicity have cultural components, but what is said to distinguish "civic" nations from "ethnic" nations is that the latter are exclusionary and closed on grounds of biological descent; the former are, in principle, open to anyone willing to adopt the national culture. 20

Yet the civic-ethnic distinction is not so clear-cut in practice. Every nation has an "ethnic core." As Anthony Smith observes

[M]odern "civic" nations have not in practice really transcended ethnicity or ethnic sentiments. This is a Western mirage, reality-as-wish; closer examination always reveals the ethnic core of civic nations, in practice, even in immigrant societies with their early pioneering and dominant (English and Spanish) culture in America, Australia, or Argentina, a culture that provided the myths and language of the would-be nation. 21

This blurring of the civic-ethnic distinction is reflected throughout U.S. history with the national culture often defined in ethnic, racial, and religious terms. 22

Why, then, if all national cultures have ethnic cores, should those outside this core embrace the national culture? Miller acknowledges that national cultures have typically been formed around the ethnic group that is dominant in a particular territory and therefore bear "the hallmarks of that group: language, religion, cultural identity." Muslim identity in contemporary Britain becomes politicized when British national identity is conceived as containing "an Anglo-Saxon bias which discriminates against Muslims (and other ethnic minorities)." But he maintains that his idea of nationality can be made "democratic in so far as it insists that everyone should take part in this debate [about what constitutes the national identity] on an equal footing, and sees the formal arenas of politics as the main (though not the only) place where the debate occurs." 23

The major difficulty here is that national cultures are not typically the product of collective deliberation in which all have the opportunity to participate. The challenge is to ensure that historically marginalized groups, as well as new groups of immigrants, have genuine opportunities to contribute "on an equal footing" to shaping the national culture. Without such opportunities, liberal nationalism collapses into conservative nationalism of the kind defended by Samuel Huntington. He calls for immigrants to assimilate into America's "Anglo- Protestant culture." Like Miller, Huntington views ideology as "a weak glue to hold together people otherwise lacking in racial, ethnic, or cultural sources of community," and he rejects race and ethnicity as constituent elements of national identity. 24 Instead, he calls on Americans of all races and ethnicities to "reinvigorate their core culture." Yet his "cultural" vision of America is pervaded by ethnic and religious elements: it is not only of a country "committed to the principles of the Creed," but also of "a deeply religious and primarily Christian country, encompassing several religious minorities, adhering to Anglo- Protestant values, speaking English, maintaining its European cultural heritage." 25 That the cultural core of the United States is the culture of its historically dominant groups is a point that Huntington unabashedly accepts.

Cultural nationalist visions of solidarity would lend support to immigration and immigrant policies that give weight to linguistic and ethnic preferences and impose special requirements on individuals from groups deemed to be outside the nation's "core culture." One example is the practice in postwar Germany of giving priority in immigration and naturalization policy to ethnic Germans; they were the only foreign nationals who were accepted as permanent residents set on the path toward citizenship. They were treated not as immigrants but "resettlers" (Aussiedler) who acted on their constitutional right to return to their country of origin. In contrast, non-ethnically German guestworkers (Gastarbeiter) were designated as "aliens" (Auslander) under the 1965 German Alien Law and excluded from German citizenship. 26 Another example is the Japanese naturalization policy that, until the late 1980s, required naturalized citizens to adopt a Japanese family name. The language requirement in contemporary naturalization policies in the West is the leading remaining example of a cultural nationalist integration policy; it reflects not only a concern with the economic and political integration of immigrants but also a nationalist concern with preserving a distinctive national culture.

Constitutional patriotism and liberal nationalism are accounts of civic solidarity that deal with what one might call first-level diversity. Individuals have different group identities and hold divergent moral and religious outlooks, yet they are expected to share the same idea of what it means to be American: either patriots committed to the same set of ideals or co-nationals sharing the relevant cultural attributes. Charles Taylor suggests an alternative approach, the idea of "deep diversity." Rather than trying to fix some minimal content as the basis of solidarity, Taylor acknowledges not only the fact of a diversity of group identities and outlooks (first-level diversity), but also the fact of a diversity of ways of belonging to the political community (second-level or deep diversity). Taylor introduces the idea of deep diversity in the context of discussing what it means to be Canadian:

Someone of, say, Italian extraction in Toronto or Ukrainian extraction in Edmonton might indeed feel Canadian as a bearer of individual rights in a multicultural mosaic. . . . But this person might nevertheless accept that a Québécois or a Cree or a Déné might belong in a very different way, that these persons were Canadian through being members of their national communities. Reciprocally, the Québécois, Cree, or Déné would accept the perfect legitimacy of the "mosaic" identity.

Civic solidarity or political identity is not "defined according to a concrete content," but, rather, "by the fact that everybody is attached to that identity in his or her own fashion, that everybody wants to continue that history and proposes to make that community progress." 27 What leads people to support second-level diversity is both the desire to be a member of the political community and the recognition of disagreement about what it means to be a member. In our world, membership in a political community provides goods we cannot do without; this, above all, may be the source of our desire for political community.

Even though Taylor contrasts Canada with the United States, accepting the myth of America as a nation of immigrants, the United States also has a need for acknowledgment of diverse modes of belonging based on the distinctive histories of different groups. Native Americans, African Americans, Irish Americans, Vietnamese Americans, and Mexican Americans: across these communities of people, we can find not only distinctive group identities, but also distinctive ways of belonging to the political community.

Deep diversity is not a recapitulation of the idea of cultural pluralism first developed in the United States by Horace Kallen, who argued for assimilation "in matters economic and political" and preservation of differences "in cultural consciousness." 28 In Kallen's view, hyphenated Americans lived their spiritual lives in private, on the left side of the hyphen, while being culturally anonymous on the right side of the hyphen. The ethnic-political distinction maps onto a private-public dichotomy; the two spheres are to be kept separate, such that Irish Americans, for example, are culturally Irish and politically American. In contrast, the idea of deep diversity recognizes that Irish Americans are culturally Irish American and politically Irish American. As Michael Walzer put it in his discussion of American identity almost twenty years ago, the culture of hyphenated Americans has been shaped by American culture, and their politics is significantly ethnic in style and substance. 29 The idea of deep or second-level diversity is not just about immigrant ethnics, which is the focus of both Kallen's and Walzer's analyses, but also racial minorities, who, based on their distinctive experiences of exclusion and struggles toward inclusion, have distinctive ways of belonging to America.

While attractive for its inclusiveness, the deep diversity model may be too thin a basis for civic solidarity in a democratic society. Can there be civic solidarity without citizens already sharing a set of values or a culture in the first place? In writing elsewhere about how different groups within democracy might "share identity space," Taylor himself suggests that the "basic principles of republican constitutions – democracy itself and human rights, among them" constitute a "non-negotiable" minimum. Yet, what distinguishes Taylor's deep diversity model of solidarity from Habermas's constitutional patriotism is the recognition that "historic identities cannot be just abstracted from." The minimal commonality of shared principles is "accompanied by a recognition that these principles can be realized in a number of different ways, and can never be applied neutrally without some confronting of the substantive religious ethnic-cultural differences in societies." 30 And in contrast to liberal nationalism, deep diversity does not aim at specifying a common national culture that must be shared by all. What matters is not so much the content of solidarity, but the ethos generated by making the effort at mutual understanding and respect.

Canada's approach to the integration of immigrants may be the closest thing there is to "deep diversity." Canadian naturalization policy is not so different from that of the United States: a short required residency period, relatively low application fees, a test of history and civics knowledge, and a language exam. 31 Where the United States and Canada diverge is in their public commitment to diversity. Through its official multiculturalism policies, Canada expresses a commitment to the value of diversity among immigrant communities through funding for ethnic associations and supporting heritage language schools. 32 Constitutional patriots and liberal nationalists say that immigrant integration should be a two-way process, that immigrants should shape the host society's dominant culture just as they are shaped by it. Multicultural accommodations actually provide the conditions under which immigrant integration might genuinely become a two-way process. Such policies send a strong message that immigrants are a welcome part of the political community and should play an active role in shaping its future evolution.

The question of solidarity may not be the most urgent task Americans face today; war and economic crisis loom larger. But the question of solidarity remains important in the face of ongoing large-scale immigration and its effects on intergroup relations, which in turn affect our ability to deal with issues of economic inequality and democracy. I hope to have shown that patriotism is not easily separated from nationalism, that nationalism needs to be evaluated in light of shared principles, and that respect for deep diversity presupposes a commitment to some shared values, including perhaps diversity itself. Rather than viewing the three models of civic solidarity I have discussed as mutually exclusive – as the proponents of each sometimes seem to suggest – we should think about how they might be made to work together with each model tempering the excesses of the others.

What is now formally required of immigrants seeking to become American citizens most clearly reflects the first two models of solidarity: professed allegiance to the principles of the Constitution (constitutional patriotism) and adoption of a shared culture by demonstrating the ability to read, write, and speak English (liberal nationalism). The revised citizenship test makes gestures toward respect for first-level diversity and inclusion of historically marginalized groups with questions such as, "Who lived in America before the Europeans arrived?" "What group of people was taken to America and sold as slaves?" "What did Susan B. Anthony do?" "What did Martin Luther King, Jr. do?" The election of the first African American president of the United States is a significant step forward. A more inclusive American solidarity requires the recognition not only of the fact that Americans are a diverse people, but also that they have distinctive ways of belonging to America.

- 1 For comments on earlier versions of this essay, I am grateful to participants in the Kadish Center Workshop on Law, Philosophy, and Political Theory at Berkeley Law School; the Penn Program on Democracy, Citizenship, and Constitutionalism; and the UCLA Legal Theory Workshop. I am especially grateful to Christopher Kutz, Sarah Paoletti, Eric Rakowski, Samuel Scheffler, Seana Shiffrin, and Rogers Smith.

- 2 Philip Gleason, "American Identity and Americanization," in Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups , ed. Stephan Thernstrom (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 1980), 31–32, 56–57.

- 3 David Hollinger, "From Identity to Solidarity," Dædalus 135 (4) (Fall 2006): 24.

- 4 David Miller, "Multiculturalism and the Welfare State: Theoretical Reflections," in Multiculturalism and the Welfare State: Recognition and Redistribution in Contemporary Democracies , ed. Keith Banting and Will Kymlicka (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 328, 334.

- 5 Charles Taylor, "Why Democracy Needs Patriotism," in For Love of Country? ed. Joshua Cohen (Boston: Beacon Press, 1996), 121.

- 6 On the purpose and varieties of narratives of collective identity and membership that have been and should be articulated not only for subnational and transnational, but also for national communities, see Rogers M. Smith, Stories of Peoplehood: The Politics and Morals of Political Membership (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

- 7 Jürgen Habermas, "Citizenship and National Identity," in Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy , trans. William Rehg (Cambridge, Mass.: mit Press, 1996), 500.

- 9 Edward Rothstein, "Connections: Refining the Tests That Confer Citizenship," The New York Times , January 23, 2006.

- 10 See http://www.uscis.gov/files/nativedocuments/100q.pdf (accessed November 28, 2008).

- 11 Habermas, "The European Nation-State," in Between Facts and Norms , trans. Rehg, 118.

- 12 Charles Taylor, "The Politics of Recognition," in Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition , ed. Amy Gutmann (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994); Will Kymlicka, Multicultural Citizenship: A Liberal Theory of Minority Rights (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

- 13 8 U.S.C., section 1423 (1988); In re Katz , 21 F.2d 867 (E.D. Mich. 1927) (attachment to principles of Constitution implies English literacy requirement).

- 14 Act of Mar. 26, 1790, ch. 3, 1 Stat., 103 and Act of Jan. 29, 1795, ch. 20, section 1, 1 Stat., 414. See James H. Kettner, The Development of American Citizenship , 1608–1870 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984), 239–243. James Madison opposed the second requirement: "It was hard to make a man swear that he preferred the Constitution of the United States, or to give any general opinion, because he may, in his own private judgment, think Monarchy or Aristocracy better, and yet be honestly determined to support his Government as he finds it"; Annals of Cong. 1, 1022–1023.

- 15 8 U.S.C., section 1427(a)(3). See also Schneiderman v. United States , 320 U.S. 118, 133 n.12 (1943), which notes the change from behaving as a person attached to constitutional principles to being a person attached to constitutional principles.

- 16 Internal Security Act of 1950, ch. 1024, sections 22, 25, 64 Stat. 987, 1006–1010, 1013–1015. The Internal Security Act provisions were included in the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, ch. 477, sections 212(a)(28), 241(a)(6), 313, 66 Stat. 163, 184–186, 205–206, 240–241.

- 17 Gerald L. Neuman, "Justifying U.S. Naturalization Policies," Virginia Journal of International Law 35 (1994): 255.

- 18 David Miller, On Nationality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 25.

- 19 Ibid., 25–26.

- 20 On the civic-ethnic distinction, see W. Rogers Brubaker, Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992); David Hollinger, Post-Ethnic America: Beyond Multiculturalism (New York: Basic Books, 1995); Michael Ignatieff, Blood and Belonging: Journeys into the New Nationalism (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1995); Yael Tamir, Liberal Nationalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993).

- 21 Anthony D. Smith, The Ethnic Origins of Nations (Oxford: Blackwell, 1986), 216.

- 22 See Rogers M. Smith, Civic Ideals: Conflicting Visions of Citizenship in U.S. History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997).

- 23 Miller, On Nationality , 122–123, 153–154.

- 24 Samuel P. Huntington, Who Are We? The Challenges to America's National Identity (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), 12. In his earlier book, American Politics: The Promise of Disharmony (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 1981), Huntington defended a "civic" view of American identity based on the "political ideas of the American creed," which include liberty, equality, democracy, individualism, and private property (46). His change in view seems to have been motivated in part by his belief that principles and ideology are too weak to unite a political community, and also by his fears about immigrants maintaining transnational identities and loyalties – in particular, Mexican immigrants whom he sees as creating bilingual, bicultural, and potentially separatist regions; Who Are We? 205.

- 25 Huntington, Who Are We? 31, 20.

- 26 Christian Joppke, "The Evolution of Alien Rights in the United States, Germany, and the European Union," Citizenship Today: Global Perspectives and Practices , ed. T. Alexander Aleinikoff and Douglas Klusmeyer (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2001), 44. In 2000, the German government moved from a strictly jus sanguinis rule toward one that combines jus sanguinis and jus soli , which opens up access to citizenship to non-ethnically German migrants, including Turkish migrant workers and their descendants. A minimum length of residency of eight (down from ten) years is also required, and dual citizenship is not formally recognized. While more inclusive than before, German citizenship laws remain the least inclusive among Western European and North American countries, with inclusiveness measured by the following criteria: whether citizenship is granted by jus soli (whether children of non-citizens who are born in a country's territory can acquire citizenship), the length of residency required for naturalization, and whether naturalized immigrants are permitted to hold dual citizenship. See Marc Morjé Howard, "Comparative Citizenship: An Agenda for Cross-National Research," Perspectives on Politics 4 (2006): 443–455.

- 27 Charles Taylor, "Shared and Divergent Values," in Reconciling the Solitudes: Essays on Canadian Federalism and Nationalism , ed. Guy Laforest (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1993), 183, 130.

- 28 Horace M. Kallen, Culture and Democracy in the United States (New York: Boni & Liveright, 1924), 114–115.

- 29 Michael Walzer, "What Does It Mean to Be an 'American'?" (1974); reprinted in What It Means to Be an American: Essays on the American Experience (New York: Marsilio, 1990), 46.

- 30 Charles Taylor, "Democratic Exclusion (and Its Remedies?)," in Multiculturalism, Liberalism, and Democracy , ed. Rajeev Bhargava et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 163.

- 31 The differences in naturalization policy are a slightly longer residency requirement in the United States (five years in contrast to Canada's three) and Canada's official acceptance of dual citizenship.

- 32 See Irene Bloemraad, Becoming a Citizen: Incorporating Immigrants and Refugees in the United States and Canada (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

What Does it Mean to be an American? Reexamining the Rights and Responsibilities of Citizenship

Skip to Content

Other ways to search:

- Events Calendar

- One American Identity, Two Distinct Meanings

Ryan Dawkins, U.S. Air Force Academy

The question before us is whether America has a distinctive identity. The answer to this question is more complicated than it may initially seem. On the one hand, the United States is certainly distinctive. Its distinctiveness is a function of this country being, in the words of Gary Wills, an “invented” country. It was constructed by individuals who built political institutions informed by political theory; it’s a country built upon ideas rather than ancestry. Indeed, Gunnar Mydral (1944) famously wrote that American identity is built around a constellation of ideals—namely, individualism, liberty, equality, hard-work, and the rule of law—that comprise the American Creed. As long as people endorse these core values, they are part of the national community--or so the argument goes. In many ways, this distinctiveness is at the heart of our historic notion of American exceptionalism.

On the other hand, work in political and social psychology tells us that membership in the national in-group is not so easy to acquire. Even though all Americans, as Americans, share the same national identification, the normative content of that identity can vary greatly across groups. Social identity theory holds that identities are social in nature—that is, their power is derived from the degree to which people consider membership with a group as important to their own self-concept. Group membership carries with it a set of norms and stereotypes that establish the boundaries of who is and who is not a member of the group. These stereotypes are derived from elite-driven notions about who is deemed the proto-typical group member, which includes stereotypes about any number of individual characteristics and attributes, including racial, cultural, and religious heritage. Group identifiers internalize group norms and stereotypes and develop a positive self-conception of themselves, while at the same time developing negative attitudes toward those who do not conform to those stereotypes.

In her book, Who Counts as an American?, Elizabeth Theiss-Morse applies social identity theory to American identity. She contends that the proto-typical American has historically been older, less-educated, Christian, and above all else, White. According to Theiss-Morse, being a strong identifier is a double-edge sword. On the one hand, strong identifiers are more willing than their counterparts to make sacrifices for other Americans. On the other hand, they are also more likely to place restrictive boundaries around who qualifies as a “true American.” Those left out of a strong identifier’s conception of a true American are typically racial and ethnic minorities, non-Christian identifiers, and extreme liberals. The creation and monitoring of these exclusionary boundaries among strong identifiers explains why this narrow ethno-cultural conception of American identity often corresponds with Nativist and anti-immigrant attitudes, especially during periods when there is a sudden influx in the foreign born, largely non-white, population. Such demographic shifts are perceived as a generalized group threat that not only challenges the power of White America, but it's very sense of belonging in the national community.

Indeed, over the last two decades, the country has undergone profound demographic change, and the dominance of the ‘proto-typical’ American is being systematically challenged. While the average White American continues to get older, brown and black America is getting younger. A majority of American children under the age of five are non-white, and the U.S. Census Bureau estimates that the United States will be a majority-minority country by 2045. Moreover, at the same time that the country is becoming less White, it is also becoming less religious. According to a 2014 Pew study, only 36% of Millennials describe themselves as religious compared to 52% and 55% for Gen Xers and Baby-boomers, respectively. As the image of the proto-typical American as a White Christian is being openly contested, more Americans are now embracing a new, much more inclusive conception of American identity, a conception that embraces the country’s immigrant past and celebrates diversity as a source of American strength.

This contestation between a vision of American identity tied to America’s European roots and a conception marked by multiculturalism coincides with the sorting of the American public into the two major political parties. Perhaps the most noteworthy trend of the last forty years is the growing social, ideological, and geographic polarization between Democrats and Republicans. As Lilliana Mason recently noted, Americans are increasingly aligning their partisan identities with their other salient identities, so much so that “the two parties have vastly different social compositions” (Mason 2018, 48). While the Republican Party is primarily composed of White, Christian, self-identified conservatives, the Democratic Party is largely non-white, non-Christian, and self-identified liberal. As a result, these two competing visions of American national identity have taken on a partisan bend.

Using survey data collected by Grinnell College in collaboration with pollster Anne Seltzer, my own research with Abby Hansen supports this idea. When presenting a battery of questions asking respondents what it meant to be a ‘true American,’ our research found that answers tended to fall into one of two orientations: one nativist, the other multicultural. We also found that those who endorsed a more nativist conception of American national identity tended to identify as Republican, while those who endorsed the multicultural conception tended to identify as Democratic. Moreover, as people endorsed each conception of American identity more strongly, they also tended to have more negative feelings toward the party to which they did not identify.

The conclusion from this research is clear. Partisans from each party are operating in very different political realities and misunderstand their fellow Americans on even a basic level. People are no longer operating from a position where, despite whatever differences may exist, they still share a common identity as Americans. Even though we all ostensibly share the common label “American,” the norms and stereotypes associated with what it means to be American could not be more different.

News & Events

- Benson Center 2022-23 CTP Lecture Series: “Western Civilization: From Classics to the Classroom.”

- Engineering Leadership 2021-22 Lecture Series

- Benson Center 2021-22 CTP Lecture Series: "Capitalism and Ethics"

- Beyond Aspirational Identities

- On “American Identities”

- The Perpetual Debate: A Consideration of American Identity

- Alien to Ourselves

- Benson Center 2020-21 Lecture Series: “The Canceled"

- Benson Center Newsletter Archive

- Miss a lecture? Watch it here!

- Student Opportunities

About Hoover

Located on the campus of Stanford University and in Washington, DC, the Hoover Institution is the nation’s preeminent research center dedicated to generating policy ideas that promote economic prosperity, national security, and democratic governance.

- The Hoover Story

- Hoover Timeline & History

- Mission Statement

- Vision of the Institution Today

- Key Focus Areas

- About our Fellows

- Research Programs

- Annual Reports

- Hoover in DC

- Fellowship Opportunities

- Visit Hoover

- David and Joan Traitel Building & Rental Information

- Newsletter Subscriptions

- Connect With Us

Hoover scholars form the Institution’s core and create breakthrough ideas aligned with our mission and ideals. What sets Hoover apart from all other policy organizations is its status as a center of scholarly excellence, its locus as a forum of scholarly discussion of public policy, and its ability to bring the conclusions of this scholarship to a public audience.

- Scott Atlas

- Thomas Sargent

- Stephen Kotkin

- Michael McConnell

- Morris P. Fiorina

- John F. Cogan

- China's Global Sharp Power Project

- Economic Policy Group

- History Working Group

- Hoover Education Success Initiative

- National Security Task Force

- National Security, Technology & Law Working Group

- Middle East and the Islamic World Working Group

- Military History/Contemporary Conflict Working Group

- Renewing Indigenous Economies Project

- State & Local Governance

- Strengthening US-India Relations

- Technology, Economics, and Governance Working Group

- Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific Region

Books by Hoover Fellows

Economics Working Papers

Hoover Education Success Initiative | The Papers

- Hoover Fellows Program

- National Fellows Program

- Student Fellowship Program

- Veteran Fellowship Program

- Congressional Fellowship Program

- Media Fellowship Program

- Silas Palmer Fellowship

- Economic Fellowship Program

Throughout our over one-hundred-year history, our work has directly led to policies that have produced greater freedom, democracy, and opportunity in the United States and the world.

- Determining America’s Role in the World

- Answering Challenges to Advanced Economies

- Empowering State and Local Governance

- Revitalizing History

- Confronting and Competing with China

- Revitalizing American Institutions

- Reforming K-12 Education

- Understanding Public Opinion

- Understanding the Effects of Technology on Economics and Governance

- Energy & Environment

- Health Care

- Immigration

- International Affairs

- Key Countries / Regions

- Law & Policy

- Politics & Public Opinion

- Science & Technology

- Security & Defense

- State & Local

- Books by Fellows

- Published Works by Fellows

- Working Papers

- Congressional Testimony

- Hoover Press

- PERIODICALS

- The Caravan

- China's Global Sharp Power

- Economic Policy

- History Lab

- Hoover Education

- Global Policy & Strategy

- National Security, Technology & Law

- Middle East and the Islamic World

- Military History & Contemporary Conflict

- Renewing Indigenous Economies

- State and Local Governance

- Technology, Economics, and Governance

Hoover scholars offer analysis of current policy challenges and provide solutions on how America can advance freedom, peace, and prosperity.

- China Global Sharp Power Weekly Alert

- Email newsletters

- Hoover Daily Report

- Subscription to Email Alerts

- Periodicals

- California on Your Mind

- Defining Ideas

- Hoover Digest

- Video Series

- Uncommon Knowledge

- Battlegrounds

- GoodFellows

- Hoover Events

- Capital Conversations

- Hoover Book Club

- AUDIO PODCASTS

- Matters of Policy & Politics

- Economics, Applied

- Free Speech Unmuted

- Secrets of Statecraft

- Pacific Century

- Libertarian

- Library & Archives

Support Hoover

Learn more about joining the community of supporters and scholars working together to advance Hoover’s mission and values.

What is MyHoover?

MyHoover delivers a personalized experience at Hoover.org . In a few easy steps, create an account and receive the most recent analysis from Hoover fellows tailored to your specific policy interests.

Watch this video for an overview of MyHoover.

Log In to MyHoover

Forgot Password

Don't have an account? Sign up

Have questions? Contact us

- Support the Mission of the Hoover Institution

- Subscribe to the Hoover Daily Report

- Follow Hoover on Social Media

Make a Gift

Your gift helps advance ideas that promote a free society.

- About Hoover Institution

- Meet Our Fellows

- Focus Areas

- Research Teams

- Library & Archives

Library & archives

Events, news & press.

To Be An American In The 21st Century

The question of what it means to be American has been debated since the founding of our republic, and we are at another moment when the question has taken on a new urgency.

In The Federalist Papers No. 2: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence for the Independent Journal , John Jay wrote to the people of New York arguing for the ratification of the US Constitution around the issue of cultural unity. He reasoned for unity because Americans were “a people descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, professing the same religion, attached to the same principles of government, very similar in their manners and customs, and who by their joint counsels, arms, and efforts, fighting side by side throughout a long and bloody war, have nobly established their general liberty and independence.”

In 1787, Jay was nuanced in that he argued an important part of American identity was also a belief in the American creed such as equality, liberty, individualism, and independence, which are enshrined in both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution he was working to ratify.

Others have interpreted Jay’s emphasis on culture more narrowly, arguing for a more tribal American identity. The late Samuel Huntington , a Harvard professor of political science, writes in his book Who are We? The Challenges to America’s National Identity, “the single most immediate and most serious challenge to America’s traditional identity comes from the immense and continuing immigration from Latin America, especially Mexico.” Huntington argues that unlike past immigrant groups, Mexicans and other Latinos have not assimilated into US culture, thereby rejecting the Anglo-Protestant values that built America. Huntington then warns this persistent inflow of Hispanic immigrants threatens to divide the United States into two peoples, two cultures, and two languages, and we ignore it at our own peril.

Huntington’s nationalism, and parochial extension of John Jay’s line of reasoning, is in direct conflict with the American identity Abraham Lincoln espoused against the anti-immigrant sentiment of his day. In a speech the future president gave in Chicago on July 10, 1858, as part of the Lincoln-Douglas debates , Lincoln discussed how on every 4 th of July Americans celebrate our Founding Fathers. However, he argues brilliantly that those who have immigrated to the United States from Germany, Ireland, France, and Scandinavia are every bit as American as those who trace their ancestry back to the founding of our republic because the principles of the Declaration of Independence serve as an electric chord running through all our hearts.

In embracing an ideal and principle that was meant to be taken literally, namely that all men are created equal, Lincoln also rejects Douglas’s beliefs that the ideals of the Declaration were reserved solely for descendants of the American Revolution and not later arrivals.

Remnants of these disagreements continue today. In his presidential farewell address , Ronald Reagan discussed the renewal that immigration brings to our identity and nation. “Thanks to each wave of new arrivals to this land of opportunity,” said Reagan, “we’re a nation forever young, forever bursting with energy and new ideas, and always on the cutting edge, always leading the world to the next frontier. This quality is vital to our future as a nation. If we ever closed the door to new Americans, our leadership in the world would soon be lost.”

Reagan views align with those of Abraham Lincoln that beliefs in our founding principles and the common American culture being continually enriched is what makes our identity.

In sharp contrast, President Trump today attacks Hispanics and Muslims as being different than other Americans and a threat to our nation. This nativist sense of national identity calls to mind the nationalism of Samuel Huntington and the most parochial reading of Federalist 2. The irony that Trump holds up the Norwegian immigrant as an ideal while Lincoln had to argue Scandinavians should be part of the American family in his 1858 speech is lost on him.

Like then-Senate candidate Lincoln and President Reagan, I believe Americans share in our nation’s principles and political culture set forth in the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Gettysburg Address, and Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

I also believe there has been and remains a cultural expectation and responsibility that immigrants will not only bring diverse perspectives but also join their new country as citizens. Jürgen Habermas , a German sociologist and philosopher, wrote of an Iranian immigrant to Germany who chooses to stand with other Germans at a concentration camp to participate in the acknowledgment of the nation’s collective guilt, even though his ancestors were not part of those crimes.

We honor our achievements as a sense of American culture, such as winning World Wars I and II, putting a man on the moon, prevailing in the Cold War, securing civil rights, and ushering in the digital age. We acknowledge the sacrifices of the generations of men and women who spilled blood, whether in places like Normandy or Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge , so we can have opportunity. We also, regardless of background, have common national traditions such as Thanksgiving, Christmas, Veteran’s Day, Memorial Day, Labor Day, and Halloween; and sports such as baseball, basketball, and American football that bind us. We engage in philanthropy, like following the rules, are generally neighborly and friendly, and keep public places clean. Yet, a hallmark of being an American is also carrying on the cultural traditions of our ancestors whether by bringing soccer, our native cuisines, our ethnic dances, or holidays like Diwali and Eid al-Adha to this country.

In the twenty-first century, Americans are more ethnically and racially diverse than we have ever been. Much of this change has been driven by immigration. In 1960, Europeans accounted for seven of eight immigrants in the United States. By 2010, nine out of ten were from outside Europe. In 1965, 84 percent of the country was non-Hispanic white, compared with 62 percent today. Nearly 59 million immigrants have arrived in the United States in the past fifty years, mostly from Latin America and Asia. This immigration has brought young workers who help offset the large-scale retirement of the baby boomers. Today, a near-record 14 percent of the country’s population is foreign born compared with just 5 percent in 1965. This diversity strengthens our country and makes it a better place to live.

At a time when growth in the US economy and those of other developed nations is slowing, immigration is vitally important to our economy. Immigrants today are more than twice as likely to start a new business. In fact, 43 percent of companies in the 2017 Fortune 500, including several technology firms in Silicon Valley, were launched by foreign-born entrepreneurs , many arriving on family visas. Immigrants also take out patents at two-to-three times the rate of native-born citizens, benefiting our entire country. Family and skilled-based visas complement each other: America would become less attractive to those who come on skills-based visas without the chance for their families to join them.

However, it is important to ensure that these economic benefits help Americans. For too long, some corporations have abused H-1B, L-1, and H-2B visas as a cheap way to displace American workers. To close these loopholes and overhaul the visa programs to protect workers and crack down on foreign outsourcing companies that deprive qualified Americans of high-skill jobs, I have cointroduced bipartisan legislation to restore the H-1B visa program back to its original intent, protect American workers, and make sure we are also providing opportunities for STEM and developing talent here at home.

When done right—as John Feinblatt, chairman of the New American Economy, stated—“The data shows it, and nearly 1,500 economists know it: immigration means more talent, more jobs, and broad economic benefits for American workers and companies alike.”

For many immigrants to this nation, a challenge in the American identity is finding a balance and respect for some of our existing American traditions, while also being proud of one’s own heritage.

I grew up in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. It is fairly suburban, rural, and was 98 percent Caucasian in the 1980s. When my family moved onto Amsterdam Avenue, there was a little bit of chatter and concern on our street that the Khannas were moving in. My parents finally figured out what the fuss was about: On Christmas Eve, everyone on our street would put candle lights on the street. We are of Hindu faith, and there was concern that we wouldn’t. My Dad said that we would be happy to put the candle lights on the street, and we put out lights every year. We were always invited to and attended all the Christmas Eve parties. I also loved playing touch football in my neighbors’ backyards, participating in the same Little League games, avoiding cars while hitting hockey pucks on the road, and going to neighbors’ homes during school candy sales to raise money for charity.

But I never associated my childhood in anyway with giving up my core identity. Let me explain. Years later as a twenty-three-year-old, when I was interning for Kathleen Kennedy Townsend (daughter of Robert Kennedy), her aide told me to go work on the Hill because I had an aptitude for policy. You cannot ever get elected, her aide said to me in a matter-of-fact tone, given your faith and heritage. I refrained from writing to him when I won, pointing out that while his boss lost her race for Congress, I ended up winning mine by 20 points .

But I do remember talking to my parents back then about identity. They told me I will make it in this country if I just keep working hard and was ethical. It is a good and decent country, they assured me. But my Mom made me promise, given my grandfather’s struggle in jail during Gandhi’s independence movement, that I will never give up who I am. I never did.

Today, the grandson of a freedom fighter who remembers seeing his parents have their green cards stamped, represents the most economically powerful Congressional District in the world.

That is the story of America. That represents the hope of American immigrant families.

In many ways my story—born in Philadelphia on the bicentennial year of America’s founding in 1976 and growing up to represent Silicon Valley—is a testament to how open our nation still is to the dreams and aspirations of freedom-loving people who trace their lineage to every corner of the world.

We are still steps away from Lincoln’s hope of becoming a nation that lives up to our founding principles and ushers in a just and lasting peace. But here is what I know: we can be open to the voices of new immigrants without losing our core values or American culture—if anything, the new immigrants will only enrich our exceptional nation.

Rep. Ro Khanna represents Silicon Valley and California’s 17 th Congressional District. Chris Schloesser, his legislative director, assisted with research for this piece.

Speaking of California and immigration, here’s how the Golden State’s population breaks down (the following numbers all courtesy of a May 2018 report by the Public Policy Institute of California). The nation state of 39.5 million residents is home to more than 10 million immigrants. In 2016, approximately 27% of California’s population was foreign-born (about twice the national percentage), with immigrants born in Latin America (51%) and Asia (39%) leading the way. Nearly eight in ten California immigrants are working-age adults (age 18 to 64)—that’s more than one-third of the entire states’ working-age population. A major concern for California’s future: the immigrant education gap. As recently as 2016, one-third (34%) of California’s immigrants hadn’t completed high school—more than four times that of US-born California residents (just 8%). Twenty-eight percent of California’s foreign-born residents hold at least a college bachelor’s degrees—again, less than California’s US-born residents (36%). Why that matters: the less education, the greater the challenge for immigrants to climb the economic ladder and make a go of it in California, home to high taxes, expensive housing, and a crushing cost of living .

[[{"fid":"257121","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default","alignment":"","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_caption[und][0][value]":"","field_file_attr[und][0][value]":""},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format":"default","alignment":"","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_caption[und][0][value]":"","field_file_attr[und][0][value]":""}},"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"1"}}]]

[[{"fid":"257126","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default","alignment":"","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_caption[und][0][value]":"","field_file_attr[und][0][value]":""},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"2":{"format":"default","alignment":"","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_caption[und][0][value]":"","field_file_attr[und][0][value]":""}},"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"2"}}]]

Source: "Almost half of Fortune 500 companies were founded by American immigrants or their children" via Brookings

View the discussion thread.

Join the Hoover Institution’s community of supporters in ideas advancing freedom.

The Essence of being American: Identity and Values

This essay about what it means to be American explores the complex identity shaped by values such as freedom, equality, innovation, and community. It argues that being American transcends legal definitions, embodying a commitment to individual liberty, self-determination, and the pursuit of happiness. The essay highlights the nation’s ongoing struggle and commitment to equality, noting the importance of addressing historical injustices. It also discusses how innovation and resilience are central to the American spirit, reflecting a history of pushing boundaries and embracing change. Furthermore, it acknowledges the strength found in the nation’s diversity, emphasizing unity and the common good as fundamental to the American identity. In summary, to be American is to be part of a dynamic experiment in democracy, constantly striving towards a more inclusive and just future.

You can also find more related free essay samples at PapersOwl about Identity.

How it works

What does it mean to be American? This question, seemingly simple, opens a vast expanse of complexity and diversity that mirrors the nation itself. To be American transcends the mere fact of citizenship or the geographic confines of the United States. It embodies a tapestry of ideals, values, and a shared sense of identity that has evolved over centuries. This essay delves into the multifaceted nature of American identity, exploring the principles and beliefs that constitute the essence of being American.

At the heart of American identity lies the cherished value of freedom. This principle is not only a historical relic of the nation’s founding but a living, breathing aspect of everyday life. Freedom in the American context encompasses the liberties enshrined in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, including freedom of speech, religion, and the pursuit of happiness. However, it goes beyond legal definitions to include the freedom to dream, to strive, and to be oneself unapologetically. This deeply ingrained belief in individual liberty and self-determination has attracted millions to its shores, seeking the promise of a better life where one’s destiny is not predetermined but crafted through effort and opportunity.

Equality stands as another pillar of what it means to be American. Though the nation’s history is fraught with struggles and contradictions regarding equality, the ideal remains a beacon that guides societal progress. Being American involves a commitment to the principle that all men and women are created equal, deserving of the same respect, opportunities, and justice. This commitment is reflected in the ongoing movements and efforts to address historical injustices and ensure that the American promise is inclusive of all, regardless of race, gender, or background.

Innovation and resilience are also key components of the American spirit. The United States has been a cradle of innovation, from the technological marvels that have reshaped the global landscape to the cultural contributions that have enriched humanity. The American ethos is one of pushing boundaries, challenging the status quo, and persisting in the face of adversity. This drive is rooted in the nation’s history of pioneers and immigrants who braved unknown frontiers in search of a new beginning. To be American is to embrace change and the possibility of a better future, fueled by the belief that through hard work and ingenuity, anything is possible.

Community and unity, despite the country’s vast diversity, play a crucial role in defining American identity. The United States is a mosaic of cultures, ethnicities, and beliefs, each contributing to the rich tapestry of the nation. To be American is to appreciate this diversity, recognizing that the strength of the country lies in its ability to unite people around shared values and ideals. It is about finding common ground and working together towards the common good, celebrating the differences that make each American unique while acknowledging the bonds that tie the nation together.

In conclusion, being American is a complex and dynamic state of being, shaped by the principles of freedom, equality, innovation, and community. It is an identity marked by a perpetual striving towards the ideals upon which the nation was founded, even as it confronts the contradictions and challenges inherent in living up to such principles. To be American is to be part of an ongoing experiment in democracy, diversity, and freedom, contributing to a story that is continually unfolding. It is an identity that, at its best, reflects a commitment to a better, more inclusive, and more just future for all who call America home.

Cite this page

The Essence of Being American: Identity and Values. (2024, Feb 27). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/the-essence-of-being-american-identity-and-values/

"The Essence of Being American: Identity and Values." PapersOwl.com , 27 Feb 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/the-essence-of-being-american-identity-and-values/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Essence of Being American: Identity and Values . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-essence-of-being-american-identity-and-values/ [Accessed: 23 May. 2024]

"The Essence of Being American: Identity and Values." PapersOwl.com, Feb 27, 2024. Accessed May 23, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/the-essence-of-being-american-identity-and-values/

"The Essence of Being American: Identity and Values," PapersOwl.com , 27-Feb-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-essence-of-being-american-identity-and-values/. [Accessed: 23-May-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Essence of Being American: Identity and Values . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-essence-of-being-american-identity-and-values/ [Accessed: 23-May-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Stanford University

SPICE is a program of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

What Does It Mean to Be an American?: Reflections from Students (Part 8)

- Sabrina Ishimatsu

The following is Part 8 of a multiple-part series. To read previous installments in this series, please visit the following articles: Part 1 , Part 2 , Part 3 , Part 4 , Part 5 , Part 6 , and Part 7 .

Since December 8, 2020, SPICE has posted seven articles that highlight reflections from 57 students on the question, “What does it mean to be an American?” Part 8 features eight additional reflections.

The free educational website “ What Does It Mean to Be an American? ” offers six lessons on immigration, civic engagement, leadership, civil liberties & equity, justice & reconciliation, and U.S.–Japan relations. The lessons encourage critical thinking through class activities and discussions. On March 24, 2021, SPICE’s Rylan Sekiguchi was honored by the Association for Asian Studies for his authorship of the lessons that are featured on the website, which was developed by the Mineta Legacy Project in partnership with SPICE.

Since the website launched in September 2020, SPICE has invited students to review and share their reflections on the lessons. Below are the reflections of eight students. I am grateful to Dr. Ignacio Ornelas, Teacher, Willow Glen High School, San Jose, California, and Aya Shehata, Hilo High School, Hawai’i, for their support with this edition. The reflections below do not necessarily reflect those of the SPICE staff.

Renn Guard, North Carolina Americans often have the privilege of being a part of many communities that help define themselves as complex, unique individuals. The past few years have demonstrated that our communities define America, a prospect that can be both concerning and hopeful. After the 2021 Atlanta spa shooting, many questioned what “Asian American” has meant and what it could mean. I observed the Asian American community connect over both their pain and frustration with the current state of the country and their hopes for a brighter future. Outside the Asian American community, many other groups, both intersecting and not, also came to sit in solidarity, reminding me that American values are rooted in communities that uphold understanding, inclusivity, and respect.

Emi Hiroshima, California By many, America is known as the “Land of Opportunity.” Certainly, this is what my great grandparents thought when they immigrated to the U.S. from Japan in the early 1900s. Although some may say it’s a less than ideal place to live, I think it provides more opportunities than other countries for those willing to try. In some countries, it is difficult for a woman to pursue certain careers or even to receive an education. They aren’t given the opportunity to even try. I believe America has a long way to go in terms of gender equality or equality for all, but women are surrounded with more chances because of others who pushed for women’s rights throughout history. In America, we are not guaranteed success, but we are provided the opportunity to always try.

Keona Marie Matsui, Hawai’i To me, being American means being free. I am free to embrace my Japanese and Filipino heritage. I am free to learn and celebrate other cultures. I am free to express myself through my physical appearance and my words. I am free to speak another language and learn many more. I am free to take advantage of the opportunities in America. But being an Asian American means that I’m stuck between identities. I was born in America, half Filipino and half Japanese, but I wasn’t born in either country. I don’t speak Tagalog or Japanese fluently; I speak English. I’m not blonde-haired or blue-eyed. I grew up in Hawai’i, surrounded by people with similar situations. Our unique experiences and identities are what make up America—and what makes us American.

Jyoti Souza, Hawai’i That is a complicated question. Some glorify being American because they immigrated from impoverished home countries. Others are ignorant to this country’s history and its current situation, or they simply do not care. For me, this country acted as a home for my grandparents who immigrated from poverty in South America. Though I am grateful for America’s seemingly open arms, it has changed vastly or never changed at all. More people are fighting against laws and bias in our government. The LGBTQ+ community asks for more freedom, African Americans demand justice, and people opposed to an election attack the White House. Some people call themselves American because of their skin color and label any others as outsiders or invaders. On the surface, being American seems like freedom and justice for all, but deep inside, it’s anything but.

Sharika Thaploo, Ohio Growing up as a first-generation immigrant in America, the idea that America was built on the great enlightenment ideals of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” was drilled into me. But to me, America meant assimilation through what I had learned from my experience in this country. I initially believed that to succeed and prosper socially I would have to discard parts of my identity that were essential to my culture. I spent time adjusting to what I believed it meant to be American. But gradually, I saw the way my identity as an Indian American affected all my decisions and my worldview. To me, being an American is bringing ideas and cultural identities into this country to make yourself and the people around you better.