Chapter 11. Interviewing

Introduction.

Interviewing people is at the heart of qualitative research. It is not merely a way to collect data but an intrinsically rewarding activity—an interaction between two people that holds the potential for greater understanding and interpersonal development. Unlike many of our daily interactions with others that are fairly shallow and mundane, sitting down with a person for an hour or two and really listening to what they have to say is a profound and deep enterprise, one that can provide not only “data” for you, the interviewer, but also self-understanding and a feeling of being heard for the interviewee. I always approach interviewing with a deep appreciation for the opportunity it gives me to understand how other people experience the world. That said, there is not one kind of interview but many, and some of these are shallower than others. This chapter will provide you with an overview of interview techniques but with a special focus on the in-depth semistructured interview guide approach, which is the approach most widely used in social science research.

An interview can be variously defined as “a conversation with a purpose” ( Lune and Berg 2018 ) and an attempt to understand the world from the point of view of the person being interviewed: “to unfold the meaning of peoples’ experiences, to uncover their lived world prior to scientific explanations” ( Kvale 2007 ). It is a form of active listening in which the interviewer steers the conversation to subjects and topics of interest to their research but also manages to leave enough space for those interviewed to say surprising things. Achieving that balance is a tricky thing, which is why most practitioners believe interviewing is both an art and a science. In my experience as a teacher, there are some students who are “natural” interviewers (often they are introverts), but anyone can learn to conduct interviews, and everyone, even those of us who have been doing this for years, can improve their interviewing skills. This might be a good time to highlight the fact that the interview is a product between interviewer and interviewee and that this product is only as good as the rapport established between the two participants. Active listening is the key to establishing this necessary rapport.

Patton ( 2002 ) makes the argument that we use interviews because there are certain things that are not observable. In particular, “we cannot observe feelings, thoughts, and intentions. We cannot observe behaviors that took place at some previous point in time. We cannot observe situations that preclude the presence of an observer. We cannot observe how people have organized the world and the meanings they attach to what goes on in the world. We have to ask people questions about those things” ( 341 ).

Types of Interviews

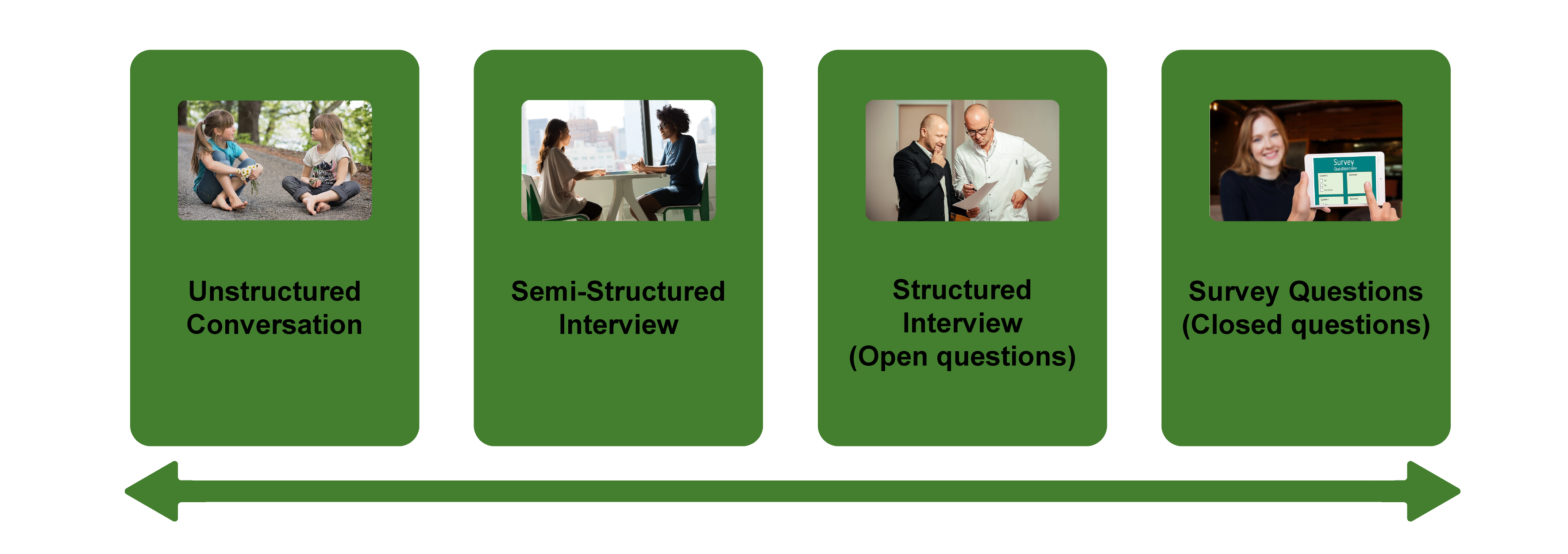

There are several distinct types of interviews. Imagine a continuum (figure 11.1). On one side are unstructured conversations—the kind you have with your friends. No one is in control of those conversations, and what you talk about is often random—whatever pops into your head. There is no secret, underlying purpose to your talking—if anything, the purpose is to talk to and engage with each other, and the words you use and the things you talk about are a little beside the point. An unstructured interview is a little like this informal conversation, except that one of the parties to the conversation (you, the researcher) does have an underlying purpose, and that is to understand the other person. You are not friends speaking for no purpose, but it might feel just as unstructured to the “interviewee” in this scenario. That is one side of the continuum. On the other side are fully structured and standardized survey-type questions asked face-to-face. Here it is very clear who is asking the questions and who is answering them. This doesn’t feel like a conversation at all! A lot of people new to interviewing have this ( erroneously !) in mind when they think about interviews as data collection. Somewhere in the middle of these two extreme cases is the “ semistructured” interview , in which the researcher uses an “interview guide” to gently move the conversation to certain topics and issues. This is the primary form of interviewing for qualitative social scientists and will be what I refer to as interviewing for the rest of this chapter, unless otherwise specified.

Informal (unstructured conversations). This is the most “open-ended” approach to interviewing. It is particularly useful in conjunction with observational methods (see chapters 13 and 14). There are no predetermined questions. Each interview will be different. Imagine you are researching the Oregon Country Fair, an annual event in Veneta, Oregon, that includes live music, artisan craft booths, face painting, and a lot of people walking through forest paths. It’s unlikely that you will be able to get a person to sit down with you and talk intensely about a set of questions for an hour and a half. But you might be able to sidle up to several people and engage with them about their experiences at the fair. You might have a general interest in what attracts people to these events, so you could start a conversation by asking strangers why they are here or why they come back every year. That’s it. Then you have a conversation that may lead you anywhere. Maybe one person tells a long story about how their parents brought them here when they were a kid. A second person talks about how this is better than Burning Man. A third person shares their favorite traveling band. And yet another enthuses about the public library in the woods. During your conversations, you also talk about a lot of other things—the weather, the utilikilts for sale, the fact that a favorite food booth has disappeared. It’s all good. You may not be able to record these conversations. Instead, you might jot down notes on the spot and then, when you have the time, write down as much as you can remember about the conversations in long fieldnotes. Later, you will have to sit down with these fieldnotes and try to make sense of all the information (see chapters 18 and 19).

Interview guide ( semistructured interview ). This is the primary type employed by social science qualitative researchers. The researcher creates an “interview guide” in advance, which she uses in every interview. In theory, every person interviewed is asked the same questions. In practice, every person interviewed is asked mostly the same topics but not always the same questions, as the whole point of a “guide” is that it guides the direction of the conversation but does not command it. The guide is typically between five and ten questions or question areas, sometimes with suggested follow-ups or prompts . For example, one question might be “What was it like growing up in Eastern Oregon?” with prompts such as “Did you live in a rural area? What kind of high school did you attend?” to help the conversation develop. These interviews generally take place in a quiet place (not a busy walkway during a festival) and are recorded. The recordings are transcribed, and those transcriptions then become the “data” that is analyzed (see chapters 18 and 19). The conventional length of one of these types of interviews is between one hour and two hours, optimally ninety minutes. Less than one hour doesn’t allow for much development of questions and thoughts, and two hours (or more) is a lot of time to ask someone to sit still and answer questions. If you have a lot of ground to cover, and the person is willing, I highly recommend two separate interview sessions, with the second session being slightly shorter than the first (e.g., ninety minutes the first day, sixty minutes the second). There are lots of good reasons for this, but the most compelling one is that this allows you to listen to the first day’s recording and catch anything interesting you might have missed in the moment and so develop follow-up questions that can probe further. This also allows the person being interviewed to have some time to think about the issues raised in the interview and go a little deeper with their answers.

Standardized questionnaire with open responses ( structured interview ). This is the type of interview a lot of people have in mind when they hear “interview”: a researcher comes to your door with a clipboard and proceeds to ask you a series of questions. These questions are all the same whoever answers the door; they are “standardized.” Both the wording and the exact order are important, as people’s responses may vary depending on how and when a question is asked. These are qualitative only in that the questions allow for “open-ended responses”: people can say whatever they want rather than select from a predetermined menu of responses. For example, a survey I collaborated on included this open-ended response question: “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?” Some of the answers were simply one word long (e.g., “debt”), and others were long statements with stories and personal anecdotes. It is possible to be surprised by the responses. Although it’s a stretch to call this kind of questioning a conversation, it does allow the person answering the question some degree of freedom in how they answer.

Survey questionnaire with closed responses (not an interview!). Standardized survey questions with specific answer options (e.g., closed responses) are not really interviews at all, and they do not generate qualitative data. For example, if we included five options for the question “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?”—(1) debt, (2) social networks, (3) alienation, (4) family doesn’t understand, (5) type of grad program—we leave no room for surprises at all. Instead, we would most likely look at patterns around these responses, thinking quantitatively rather than qualitatively (e.g., using regression analysis techniques, we might find that working-class sociologists were twice as likely to bring up alienation). It can sometimes be confusing for new students because the very same survey can include both closed-ended and open-ended questions. The key is to think about how these will be analyzed and to what level surprises are possible. If your plan is to turn all responses into a number and make predictions about correlations and relationships, you are no longer conducting qualitative research. This is true even if you are conducting this survey face-to-face with a real live human. Closed-response questions are not conversations of any kind, purposeful or not.

In summary, the semistructured interview guide approach is the predominant form of interviewing for social science qualitative researchers because it allows a high degree of freedom of responses from those interviewed (thus allowing for novel discoveries) while still maintaining some connection to a research question area or topic of interest. The rest of the chapter assumes the employment of this form.

Creating an Interview Guide

Your interview guide is the instrument used to bridge your research question(s) and what the people you are interviewing want to tell you. Unlike a standardized questionnaire, the questions actually asked do not need to be exactly what you have written down in your guide. The guide is meant to create space for those you are interviewing to talk about the phenomenon of interest, but sometimes you are not even sure what that phenomenon is until you start asking questions. A priority in creating an interview guide is to ensure it offers space. One of the worst mistakes is to create questions that are so specific that the person answering them will not stray. Relatedly, questions that sound “academic” will shut down a lot of respondents. A good interview guide invites respondents to talk about what is important to them, not feel like they are performing or being evaluated by you.

Good interview questions should not sound like your “research question” at all. For example, let’s say your research question is “How do patriarchal assumptions influence men’s understanding of climate change and responses to climate change?” It would be worse than unhelpful to ask a respondent, “How do your assumptions about the role of men affect your understanding of climate change?” You need to unpack this into manageable nuggets that pull your respondent into the area of interest without leading him anywhere. You could start by asking him what he thinks about climate change in general. Or, even better, whether he has any concerns about heatwaves or increased tornadoes or polar icecaps melting. Once he starts talking about that, you can ask follow-up questions that bring in issues around gendered roles, perhaps asking if he is married (to a woman) and whether his wife shares his thoughts and, if not, how they negotiate that difference. The fact is, you won’t really know the right questions to ask until he starts talking.

There are several distinct types of questions that can be used in your interview guide, either as main questions or as follow-up probes. If you remember that the point is to leave space for the respondent, you will craft a much more effective interview guide! You will also want to think about the place of time in both the questions themselves (past, present, future orientations) and the sequencing of the questions.

Researcher Note

Suggestion : As you read the next three sections (types of questions, temporality, question sequence), have in mind a particular research question, and try to draft questions and sequence them in a way that opens space for a discussion that helps you answer your research question.

Type of Questions

Experience and behavior questions ask about what a respondent does regularly (their behavior) or has done (their experience). These are relatively easy questions for people to answer because they appear more “factual” and less subjective. This makes them good opening questions. For the study on climate change above, you might ask, “Have you ever experienced an unusual weather event? What happened?” Or “You said you work outside? What is a typical summer workday like for you? How do you protect yourself from the heat?”

Opinion and values questions , in contrast, ask questions that get inside the minds of those you are interviewing. “Do you think climate change is real? Who or what is responsible for it?” are two such questions. Note that you don’t have to literally ask, “What is your opinion of X?” but you can find a way to ask the specific question relevant to the conversation you are having. These questions are a bit trickier to ask because the answers you get may depend in part on how your respondent perceives you and whether they want to please you or not. We’ve talked a fair amount about being reflective. Here is another place where this comes into play. You need to be aware of the effect your presence might have on the answers you are receiving and adjust accordingly. If you are a woman who is perceived as liberal asking a man who identifies as conservative about climate change, there is a lot of subtext that can be going on in the interview. There is no one right way to resolve this, but you must at least be aware of it.

Feeling questions are questions that ask respondents to draw on their emotional responses. It’s pretty common for academic researchers to forget that we have bodies and emotions, but people’s understandings of the world often operate at this affective level, sometimes unconsciously or barely consciously. It is a good idea to include questions that leave space for respondents to remember, imagine, or relive emotional responses to particular phenomena. “What was it like when you heard your cousin’s house burned down in that wildfire?” doesn’t explicitly use any emotion words, but it allows your respondent to remember what was probably a pretty emotional day. And if they respond emotionally neutral, that is pretty interesting data too. Note that asking someone “How do you feel about X” is not always going to evoke an emotional response, as they might simply turn around and respond with “I think that…” It is better to craft a question that actually pushes the respondent into the affective category. This might be a specific follow-up to an experience and behavior question —for example, “You just told me about your daily routine during the summer heat. Do you worry it is going to get worse?” or “Have you ever been afraid it will be too hot to get your work accomplished?”

Knowledge questions ask respondents what they actually know about something factual. We have to be careful when we ask these types of questions so that respondents do not feel like we are evaluating them (which would shut them down), but, for example, it is helpful to know when you are having a conversation about climate change that your respondent does in fact know that unusual weather events have increased and that these have been attributed to climate change! Asking these questions can set the stage for deeper questions and can ensure that the conversation makes the same kind of sense to both participants. For example, a conversation about political polarization can be put back on track once you realize that the respondent doesn’t really have a clear understanding that there are two parties in the US. Instead of asking a series of questions about Republicans and Democrats, you might shift your questions to talk more generally about political disagreements (e.g., “people against abortion”). And sometimes what you do want to know is the level of knowledge about a particular program or event (e.g., “Are you aware you can discharge your student loans through the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program?”).

Sensory questions call on all senses of the respondent to capture deeper responses. These are particularly helpful in sparking memory. “Think back to your childhood in Eastern Oregon. Describe the smells, the sounds…” Or you could use these questions to help a person access the full experience of a setting they customarily inhabit: “When you walk through the doors to your office building, what do you see? Hear? Smell?” As with feeling questions , these questions often supplement experience and behavior questions . They are another way of allowing your respondent to report fully and deeply rather than remain on the surface.

Creative questions employ illustrative examples, suggested scenarios, or simulations to get respondents to think more deeply about an issue, topic, or experience. There are many options here. In The Trouble with Passion , Erin Cech ( 2021 ) provides a scenario in which “Joe” is trying to decide whether to stay at his decent but boring computer job or follow his passion by opening a restaurant. She asks respondents, “What should Joe do?” Their answers illuminate the attraction of “passion” in job selection. In my own work, I have used a news story about an upwardly mobile young man who no longer has time to see his mother and sisters to probe respondents’ feelings about the costs of social mobility. Jessi Streib and Betsy Leondar-Wright have used single-page cartoon “scenes” to elicit evaluations of potential racial discrimination, sexual harassment, and classism. Barbara Sutton ( 2010 ) has employed lists of words (“strong,” “mother,” “victim”) on notecards she fans out and asks her female respondents to select and discuss.

Background/Demographic Questions

You most definitely will want to know more about the person you are interviewing in terms of conventional demographic information, such as age, race, gender identity, occupation, and educational attainment. These are not questions that normally open up inquiry. [1] For this reason, my practice has been to include a separate “demographic questionnaire” sheet that I ask each respondent to fill out at the conclusion of the interview. Only include those aspects that are relevant to your study. For example, if you are not exploring religion or religious affiliation, do not include questions about a person’s religion on the demographic sheet. See the example provided at the end of this chapter.

Temporality

Any type of question can have a past, present, or future orientation. For example, if you are asking a behavior question about workplace routine, you might ask the respondent to talk about past work, present work, and ideal (future) work. Similarly, if you want to understand how people cope with natural disasters, you might ask your respondent how they felt then during the wildfire and now in retrospect and whether and to what extent they have concerns for future wildfire disasters. It’s a relatively simple suggestion—don’t forget to ask about past, present, and future—but it can have a big impact on the quality of the responses you receive.

Question Sequence

Having a list of good questions or good question areas is not enough to make a good interview guide. You will want to pay attention to the order in which you ask your questions. Even though any one respondent can derail this order (perhaps by jumping to answer a question you haven’t yet asked), a good advance plan is always helpful. When thinking about sequence, remember that your goal is to get your respondent to open up to you and to say things that might surprise you. To establish rapport, it is best to start with nonthreatening questions. Asking about the present is often the safest place to begin, followed by the past (they have to know you a little bit to get there), and lastly, the future (talking about hopes and fears requires the most rapport). To allow for surprises, it is best to move from very general questions to more particular questions only later in the interview. This ensures that respondents have the freedom to bring up the topics that are relevant to them rather than feel like they are constrained to answer you narrowly. For example, refrain from asking about particular emotions until these have come up previously—don’t lead with them. Often, your more particular questions will emerge only during the course of the interview, tailored to what is emerging in conversation.

Once you have a set of questions, read through them aloud and imagine you are being asked the same questions. Does the set of questions have a natural flow? Would you be willing to answer the very first question to a total stranger? Does your sequence establish facts and experiences before moving on to opinions and values? Did you include prefatory statements, where necessary; transitions; and other announcements? These can be as simple as “Hey, we talked a lot about your experiences as a barista while in college.… Now I am turning to something completely different: how you managed friendships in college.” That is an abrupt transition, but it has been softened by your acknowledgment of that.

Probes and Flexibility

Once you have the interview guide, you will also want to leave room for probes and follow-up questions. As in the sample probe included here, you can write out the obvious probes and follow-up questions in advance. You might not need them, as your respondent might anticipate them and include full responses to the original question. Or you might need to tailor them to how your respondent answered the question. Some common probes and follow-up questions include asking for more details (When did that happen? Who else was there?), asking for elaboration (Could you say more about that?), asking for clarification (Does that mean what I think it means or something else? I understand what you mean, but someone else reading the transcript might not), and asking for contrast or comparison (How did this experience compare with last year’s event?). “Probing is a skill that comes from knowing what to look for in the interview, listening carefully to what is being said and what is not said, and being sensitive to the feedback needs of the person being interviewed” ( Patton 2002:374 ). It takes work! And energy. I and many other interviewers I know report feeling emotionally and even physically drained after conducting an interview. You are tasked with active listening and rearranging your interview guide as needed on the fly. If you only ask the questions written down in your interview guide with no deviations, you are doing it wrong. [2]

The Final Question

Every interview guide should include a very open-ended final question that allows for the respondent to say whatever it is they have been dying to tell you but you’ve forgotten to ask. About half the time they are tired too and will tell you they have nothing else to say. But incredibly, some of the most honest and complete responses take place here, at the end of a long interview. You have to realize that the person being interviewed is often discovering things about themselves as they talk to you and that this process of discovery can lead to new insights for them. Making space at the end is therefore crucial. Be sure you convey that you actually do want them to tell you more, that the offer of “anything else?” is not read as an empty convention where the polite response is no. Here is where you can pull from that active listening and tailor the final question to the particular person. For example, “I’ve asked you a lot of questions about what it was like to live through that wildfire. I’m wondering if there is anything I’ve forgotten to ask, especially because I haven’t had that experience myself” is a much more inviting final question than “Great. Anything you want to add?” It’s also helpful to convey to the person that you have the time to listen to their full answer, even if the allotted time is at the end. After all, there are no more questions to ask, so the respondent knows exactly how much time is left. Do them the courtesy of listening to them!

Conducting the Interview

Once you have your interview guide, you are on your way to conducting your first interview. I always practice my interview guide with a friend or family member. I do this even when the questions don’t make perfect sense for them, as it still helps me realize which questions make no sense, are poorly worded (too academic), or don’t follow sequentially. I also practice the routine I will use for interviewing, which goes something like this:

- Introduce myself and reintroduce the study

- Provide consent form and ask them to sign and retain/return copy

- Ask if they have any questions about the study before we begin

- Ask if I can begin recording

- Ask questions (from interview guide)

- Turn off the recording device

- Ask if they are willing to fill out my demographic questionnaire

- Collect questionnaire and, without looking at the answers, place in same folder as signed consent form

- Thank them and depart

A note on remote interviewing: Interviews have traditionally been conducted face-to-face in a private or quiet public setting. You don’t want a lot of background noise, as this will make transcriptions difficult. During the recent global pandemic, many interviewers, myself included, learned the benefits of interviewing remotely. Although face-to-face is still preferable for many reasons, Zoom interviewing is not a bad alternative, and it does allow more interviews across great distances. Zoom also includes automatic transcription, which significantly cuts down on the time it normally takes to convert our conversations into “data” to be analyzed. These automatic transcriptions are not perfect, however, and you will still need to listen to the recording and clarify and clean up the transcription. Nor do automatic transcriptions include notations of body language or change of tone, which you may want to include. When interviewing remotely, you will want to collect the consent form before you meet: ask them to read, sign, and return it as an email attachment. I think it is better to ask for the demographic questionnaire after the interview, but because some respondents may never return it then, it is probably best to ask for this at the same time as the consent form, in advance of the interview.

What should you bring to the interview? I would recommend bringing two copies of the consent form (one for you and one for the respondent), a demographic questionnaire, a manila folder in which to place the signed consent form and filled-out demographic questionnaire, a printed copy of your interview guide (I print with three-inch right margins so I can jot down notes on the page next to relevant questions), a pen, a recording device, and water.

After the interview, you will want to secure the signed consent form in a locked filing cabinet (if in print) or a password-protected folder on your computer. Using Excel or a similar program that allows tables/spreadsheets, create an identifying number for your interview that links to the consent form without using the name of your respondent. For example, let’s say that I conduct interviews with US politicians, and the first person I meet with is George W. Bush. I will assign the transcription the number “INT#001” and add it to the signed consent form. [3] The signed consent form goes into a locked filing cabinet, and I never use the name “George W. Bush” again. I take the information from the demographic sheet, open my Excel spreadsheet, and add the relevant information in separate columns for the row INT#001: White, male, Republican. When I interview Bill Clinton as my second interview, I include a second row: INT#002: White, male, Democrat. And so on. The only link to the actual name of the respondent and this information is the fact that the consent form (unavailable to anyone but me) has stamped on it the interview number.

Many students get very nervous before their first interview. Actually, many of us are always nervous before the interview! But do not worry—this is normal, and it does pass. Chances are, you will be pleasantly surprised at how comfortable it begins to feel. These “purposeful conversations” are often a delight for both participants. This is not to say that sometimes things go wrong. I often have my students practice several “bad scenarios” (e.g., a respondent that you cannot get to open up; a respondent who is too talkative and dominates the conversation, steering it away from the topics you are interested in; emotions that completely take over; or shocking disclosures you are ill-prepared to handle), but most of the time, things go quite well. Be prepared for the unexpected, but know that the reason interviews are so popular as a technique of data collection is that they are usually richly rewarding for both participants.

One thing that I stress to my methods students and remind myself about is that interviews are still conversations between people. If there’s something you might feel uncomfortable asking someone about in a “normal” conversation, you will likely also feel a bit of discomfort asking it in an interview. Maybe more importantly, your respondent may feel uncomfortable. Social research—especially about inequality—can be uncomfortable. And it’s easy to slip into an abstract, intellectualized, or removed perspective as an interviewer. This is one reason trying out interview questions is important. Another is that sometimes the question sounds good in your head but doesn’t work as well out loud in practice. I learned this the hard way when a respondent asked me how I would answer the question I had just posed, and I realized that not only did I not really know how I would answer it, but I also wasn’t quite as sure I knew what I was asking as I had thought.

—Elizabeth M. Lee, Associate Professor of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University, author of Class and Campus Life , and co-author of Geographies of Campus Inequality

How Many Interviews?

Your research design has included a targeted number of interviews and a recruitment plan (see chapter 5). Follow your plan, but remember that “ saturation ” is your goal. You interview as many people as you can until you reach a point at which you are no longer surprised by what they tell you. This means not that no one after your first twenty interviews will have surprising, interesting stories to tell you but rather that the picture you are forming about the phenomenon of interest to you from a research perspective has come into focus, and none of the interviews are substantially refocusing that picture. That is when you should stop collecting interviews. Note that to know when you have reached this, you will need to read your transcripts as you go. More about this in chapters 18 and 19.

Your Final Product: The Ideal Interview Transcript

A good interview transcript will demonstrate a subtly controlled conversation by the skillful interviewer. In general, you want to see replies that are about one paragraph long, not short sentences and not running on for several pages. Although it is sometimes necessary to follow respondents down tangents, it is also often necessary to pull them back to the questions that form the basis of your research study. This is not really a free conversation, although it may feel like that to the person you are interviewing.

Final Tips from an Interview Master

Annette Lareau is arguably one of the masters of the trade. In Listening to People , she provides several guidelines for good interviews and then offers a detailed example of an interview gone wrong and how it could be addressed (please see the “Further Readings” at the end of this chapter). Here is an abbreviated version of her set of guidelines: (1) interview respondents who are experts on the subjects of most interest to you (as a corollary, don’t ask people about things they don’t know); (2) listen carefully and talk as little as possible; (3) keep in mind what you want to know and why you want to know it; (4) be a proactive interviewer (subtly guide the conversation); (5) assure respondents that there aren’t any right or wrong answers; (6) use the respondent’s own words to probe further (this both allows you to accurately identify what you heard and pushes the respondent to explain further); (7) reuse effective probes (don’t reinvent the wheel as you go—if repeating the words back works, do it again and again); (8) focus on learning the subjective meanings that events or experiences have for a respondent; (9) don’t be afraid to ask a question that draws on your own knowledge (unlike trial lawyers who are trained never to ask a question for which they don’t already know the answer, sometimes it’s worth it to ask risky questions based on your hypotheses or just plain hunches); (10) keep thinking while you are listening (so difficult…and important); (11) return to a theme raised by a respondent if you want further information; (12) be mindful of power inequalities (and never ever coerce a respondent to continue the interview if they want out); (13) take control with overly talkative respondents; (14) expect overly succinct responses, and develop strategies for probing further; (15) balance digging deep and moving on; (16) develop a plan to deflect questions (e.g., let them know you are happy to answer any questions at the end of the interview, but you don’t want to take time away from them now); and at the end, (17) check to see whether you have asked all your questions. You don’t always have to ask everyone the same set of questions, but if there is a big area you have forgotten to cover, now is the time to recover ( Lareau 2021:93–103 ).

Sample: Demographic Questionnaire

ASA Taskforce on First-Generation and Working-Class Persons in Sociology – Class Effects on Career Success

Supplementary Demographic Questionnaire

Thank you for your participation in this interview project. We would like to collect a few pieces of key demographic information from you to supplement our analyses. Your answers to these questions will be kept confidential and stored by ID number. All of your responses here are entirely voluntary!

What best captures your race/ethnicity? (please check any/all that apply)

- White (Non Hispanic/Latina/o/x)

- Black or African American

- Hispanic, Latino/a/x of Spanish

- Asian or Asian American

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Middle Eastern or North African

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- Other : (Please write in: ________________)

What is your current position?

- Grad Student

- Full Professor

Please check any and all of the following that apply to you:

- I identify as a working-class academic

- I was the first in my family to graduate from college

- I grew up poor

What best reflects your gender?

- Transgender female/Transgender woman

- Transgender male/Transgender man

- Gender queer/ Gender nonconforming

Anything else you would like us to know about you?

Example: Interview Guide

In this example, follow-up prompts are italicized. Note the sequence of questions. That second question often elicits an entire life history , answering several later questions in advance.

Introduction Script/Question

Thank you for participating in our survey of ASA members who identify as first-generation or working-class. As you may have heard, ASA has sponsored a taskforce on first-generation and working-class persons in sociology and we are interested in hearing from those who so identify. Your participation in this interview will help advance our knowledge in this area.

- The first thing we would like to as you is why you have volunteered to be part of this study? What does it mean to you be first-gen or working class? Why were you willing to be interviewed?

- How did you decide to become a sociologist?

- Can you tell me a little bit about where you grew up? ( prompts: what did your parent(s) do for a living? What kind of high school did you attend?)

- Has this identity been salient to your experience? (how? How much?)

- How welcoming was your grad program? Your first academic employer?

- Why did you decide to pursue sociology at the graduate level?

- Did you experience culture shock in college? In graduate school?

- Has your FGWC status shaped how you’ve thought about where you went to school? debt? etc?

- Were you mentored? How did this work (not work)? How might it?

- What did you consider when deciding where to go to grad school? Where to apply for your first position?

- What, to you, is a mark of career success? Have you achieved that success? What has helped or hindered your pursuit of success?

- Do you think sociology, as a field, cares about prestige?

- Let’s talk a little bit about intersectionality. How does being first-gen/working class work alongside other identities that are important to you?

- What do your friends and family think about your career? Have you had any difficulty relating to family members or past friends since becoming highly educated?

- Do you have any debt from college/grad school? Are you concerned about this? Could you explain more about how you paid for college/grad school? (here, include assistance from family, fellowships, scholarships, etc.)

- (You’ve mentioned issues or obstacles you had because of your background.) What could have helped? Or, who or what did? Can you think of fortuitous moments in your career?

- Do you have any regrets about the path you took?

- Is there anything else you would like to add? Anything that the Taskforce should take note of, that we did not ask you about here?

Further Readings

Britten, Nicky. 1995. “Qualitative Interviews in Medical Research.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 31(6999):251–253. A good basic overview of interviewing particularly useful for students of public health and medical research generally.

Corbin, Juliet, and Janice M. Morse. 2003. “The Unstructured Interactive Interview: Issues of Reciprocity and Risks When Dealing with Sensitive Topics.” Qualitative Inquiry 9(3):335–354. Weighs the potential benefits and harms of conducting interviews on topics that may cause emotional distress. Argues that the researcher’s skills and code of ethics should ensure that the interviewing process provides more of a benefit to both participant and researcher than a harm to the former.

Gerson, Kathleen, and Sarah Damaske. 2020. The Science and Art of Interviewing . New York: Oxford University Press. A useful guidebook/textbook for both undergraduates and graduate students, written by sociologists.

Kvale, Steiner. 2007. Doing Interviews . London: SAGE. An easy-to-follow guide to conducting and analyzing interviews by psychologists.

Lamont, Michèle, and Ann Swidler. 2014. “Methodological Pluralism and the Possibilities and Limits of Interviewing.” Qualitative Sociology 37(2):153–171. Written as a response to various debates surrounding the relative value of interview-based studies and ethnographic studies defending the particular strengths of interviewing. This is a must-read article for anyone seriously engaging in qualitative research!

Pugh, Allison J. 2013. “What Good Are Interviews for Thinking about Culture? Demystifying Interpretive Analysis.” American Journal of Cultural Sociology 1(1):42–68. Another defense of interviewing written against those who champion ethnographic methods as superior, particularly in the area of studying culture. A classic.

Rapley, Timothy John. 2001. “The ‘Artfulness’ of Open-Ended Interviewing: Some considerations in analyzing interviews.” Qualitative Research 1(3):303–323. Argues for the importance of “local context” of data production (the relationship built between interviewer and interviewee, for example) in properly analyzing interview data.

Weiss, Robert S. 1995. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies . New York: Simon and Schuster. A classic and well-regarded textbook on interviewing. Because Weiss has extensive experience conducting surveys, he contrasts the qualitative interview with the survey questionnaire well; particularly useful for those trained in the latter.

- I say “normally” because how people understand their various identities can itself be an expansive topic of inquiry. Here, I am merely talking about collecting otherwise unexamined demographic data, similar to how we ask people to check boxes on surveys. ↵

- Again, this applies to “semistructured in-depth interviewing.” When conducting standardized questionnaires, you will want to ask each question exactly as written, without deviations! ↵

- I always include “INT” in the number because I sometimes have other kinds of data with their own numbering: FG#001 would mean the first focus group, for example. I also always include three-digit spaces, as this allows for up to 999 interviews (or, more realistically, allows for me to interview up to one hundred persons without having to reset my numbering system). ↵

A method of data collection in which the researcher asks the participant questions; the answers to these questions are often recorded and transcribed verbatim. There are many different kinds of interviews - see also semistructured interview , structured interview , and unstructured interview .

A document listing key questions and question areas for use during an interview. It is used most often for semi-structured interviews. A good interview guide may have no more than ten primary questions for two hours of interviewing, but these ten questions will be supplemented by probes and relevant follow-ups throughout the interview. Most IRBs require the inclusion of the interview guide in applications for review. See also interview and semi-structured interview .

A data-collection method that relies on casual, conversational, and informal interviewing. Despite its apparent conversational nature, the researcher usually has a set of particular questions or question areas in mind but allows the interview to unfold spontaneously. This is a common data-collection technique among ethnographers. Compare to the semi-structured or in-depth interview .

A form of interview that follows a standard guide of questions asked, although the order of the questions may change to match the particular needs of each individual interview subject, and probing “follow-up” questions are often added during the course of the interview. The semi-structured interview is the primary form of interviewing used by qualitative researchers in the social sciences. It is sometimes referred to as an “in-depth” interview. See also interview and interview guide .

The cluster of data-collection tools and techniques that involve observing interactions between people, the behaviors, and practices of individuals (sometimes in contrast to what they say about how they act and behave), and cultures in context. Observational methods are the key tools employed by ethnographers and Grounded Theory .

Follow-up questions used in a semi-structured interview to elicit further elaboration. Suggested prompts can be included in the interview guide to be used/deployed depending on how the initial question was answered or if the topic of the prompt does not emerge spontaneously.

A form of interview that follows a strict set of questions, asked in a particular order, for all interview subjects. The questions are also the kind that elicits short answers, and the data is more “informative” than probing. This is often used in mixed-methods studies, accompanying a survey instrument. Because there is no room for nuance or the exploration of meaning in structured interviews, qualitative researchers tend to employ semi-structured interviews instead. See also interview.

The point at which you can conclude data collection because every person you are interviewing, the interaction you are observing, or content you are analyzing merely confirms what you have already noted. Achieving saturation is often used as the justification for the final sample size.

An interview variant in which a person’s life story is elicited in a narrative form. Turning points and key themes are established by the researcher and used as data points for further analysis.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Qualitative Interviewing

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 13 January 2019

- Cite this reference work entry

- Sally Nathan 2 ,

- Christy Newman 3 &

- Kari Lancaster 3

4118 Accesses

20 Citations

8 Altmetric

Qualitative interviewing is a foundational method in qualitative research and is widely used in health research and the social sciences. Both qualitative semi-structured and in-depth unstructured interviews use verbal communication, mostly in face-to-face interactions, to collect data about the attitudes, beliefs, and experiences of participants. Interviews are an accessible, often affordable, and effective method to understand the socially situated world of research participants. The approach is typically informed by an interpretive framework where the data collected is not viewed as evidence of the truth or reality of a situation or experience but rather a context-bound subjective insight from the participants. The researcher needs to be open to new insights and to privilege the participant’s experience in data collection. The data from qualitative interviews is not generalizable, but its exploratory nature permits the collection of rich data which can answer questions about which little is already known. This chapter introduces the reader to qualitative interviewing, the range of traditions within which interviewing is utilized as a method, and highlights the advantages and some of the challenges and misconceptions in its application. The chapter also provides practical guidance on planning and conducting interview studies. Three case examples are presented to highlight the benefits and risks in the use of interviewing with different participants, providing situated insights as well as advice about how to go about learning to interview if you are a novice.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Baez B. Confidentiality in qualitative research: reflections on secrets, power and agency. Qual Res. 2002;2(1):35–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794102002001638 .

Article Google Scholar

Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. London: Sage Publications; 2013.

Google Scholar

Braun V, Clarke V, Gray D. Collecting qualitative data: a practical guide to textual, media and virtual techniques. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2017.

Book Google Scholar

Bryman A. Social research methods. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016.

Crotty M. The foundations of social research: meaning and perspective in the research process. Australia: Allen & Unwin; 1998.

Davies MB. Doing a successful research project: using qualitative or quantitative methods. New York: Palgrave MacMillan; 2007.

Dickson-Swift V, James EL, Liamputtong P. Undertaking sensitive research in the health and social sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

Foster M, Nathan S, Ferry M. The experience of drug-dependent adolescents in a therapeutic community. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29(5):531–9.

Gillham B. The research interview. London: Continuum; 2000.

Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967.

Hesse-Biber SN, Leavy P. In-depth interview. In: The practice of qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2011. p. 119–47

Irvine A. Duration, dominance and depth in telephone and face-to-face interviews: a comparative exploration. Int J Qual Methods. 2011;10(3):202–20.

Johnson JM. In-depth interviewing. In: Gubrium JF, Holstein JA, editors. Handbook of interview research: context and method. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2001.

Kvale S. Interviews: an introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1996.

Kvale S. Doing interviews. London: Sage Publications; 2007.

Lancaster K. Confidentiality, anonymity and power relations in elite interviewing: conducting qualitative policy research in a politicised domain. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2017;20(1):93–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2015.1123555 .

Leavy P. Method meets art: arts-based research practice. New York: Guilford Publications; 2015.

Liamputtong P. Researching the vulnerable: a guide to sensitive research methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2007.

Liamputtong P. Qualitative research methods. 4th ed. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2013.

Mays N, Pope C. Quality in qualitative health research. In: Pope C, Mays N, editors. Qualitative research in health care. London: BMJ Books; 2000. p. 89–102.

McLellan E, MacQueen KM, Neidig JL. Beyond the qualitative interview: data preparation and transcription. Field Methods. 2003;15(1):63–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822x02239573 .

Minichiello V, Aroni R, Hays T. In-depth interviewing: principles, techniques, analysis. 3rd ed. Sydney: Pearson Education Australia; 2008.

Morris ZS. The truth about interviewing elites. Politics. 2009;29(3):209–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9256.2009.01357.x .

Nathan S, Foster M, Ferry M. Peer and sexual relationships in the experience of drug-dependent adolescents in a therapeutic community. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2011;30(4):419–27.

National Health and Medical Research Council. National statement on ethical conduct in human research. Canberra: Australian Government; 2007.

Neal S, McLaughlin E. Researching up? Interviews, emotionality and policy-making elites. J Soc Policy. 2009;38(04):689–707. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279409990018 .

O’Reilly M, Parker N. ‘Unsatisfactory saturation’: a critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qual Res. 2013;13(2):190–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112446106 .

Ostrander S. “Surely you're not in this just to be helpful”: access, rapport and interviews in three studies of elites. In: Hertz R, Imber J, editors. Studying elites using qualitative methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1995. p. 133–50.

Chapter Google Scholar

Patton M. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2015.

Punch KF. Introduction to social research: quantitative and qualitative approaches. London: Sage; 2005.

Rhodes T, Bernays S, Houmoller K. Parents who use drugs: accounting for damage and its limitation. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(8):1489–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.028 .

Riessman CK. Narrative analysis. London: Sage; 1993.

Ritchie J. Not everything can be reduced to numbers. In: Berglund C, editor. Health research. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2001. p. 149–73.

Rubin H, Rubin I. Qualitative interviewing: the art of hearing data. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2012.

Serry T, Liamputtong P. The in-depth interviewing method in health. In: Liamputtong P, editor. Research methods in health: foundations for evidence-based practice. 3rd ed. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2017. p. 67–83.

Silverman D. Doing qualitative research. 5th ed. London: Sage; 2017.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (coreq): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Public Health and Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, UNSW, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Sally Nathan

Centre for Social Research in Health, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, UNSW, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Christy Newman & Kari Lancaster

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sally Nathan .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Science and Health, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

Pranee Liamputtong

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Nathan, S., Newman, C., Lancaster, K. (2019). Qualitative Interviewing. In: Liamputtong, P. (eds) Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_77

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_77

Published : 13 January 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-10-5250-7

Online ISBN : 978-981-10-5251-4

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

Published on 4 May 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on 10 October 2022.

An interview is a qualitative research method that relies on asking questions in order to collect data . Interviews involve two or more people, one of whom is the interviewer asking the questions.

There are several types of interviews, often differentiated by their level of structure. Structured interviews have predetermined questions asked in a predetermined order. Unstructured interviews are more free-flowing, and semi-structured interviews fall in between.

Interviews are commonly used in market research, social science, and ethnographic research.

Table of contents

What is a structured interview, what is a semi-structured interview, what is an unstructured interview, what is a focus group, examples of interview questions, advantages and disadvantages of interviews, frequently asked questions about types of interviews.

Structured interviews have predetermined questions in a set order. They are often closed-ended, featuring dichotomous (yes/no) or multiple-choice questions. While open-ended structured interviews exist, they are much less common. The types of questions asked make structured interviews a predominantly quantitative tool.

Asking set questions in a set order can help you see patterns among responses, and it allows you to easily compare responses between participants while keeping other factors constant. This can mitigate biases and lead to higher reliability and validity. However, structured interviews can be overly formal, as well as limited in scope and flexibility.

- You feel very comfortable with your topic. This will help you formulate your questions most effectively.

- You have limited time or resources. Structured interviews are a bit more straightforward to analyse because of their closed-ended nature, and can be a doable undertaking for an individual.

- Your research question depends on holding environmental conditions between participants constant

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Semi-structured interviews are a blend of structured and unstructured interviews. While the interviewer has a general plan for what they want to ask, the questions do not have to follow a particular phrasing or order.

Semi-structured interviews are often open-ended, allowing for flexibility, but follow a predetermined thematic framework, giving a sense of order. For this reason, they are often considered ‘the best of both worlds’.

However, if the questions differ substantially between participants, it can be challenging to look for patterns, lessening the generalisability and validity of your results.

- You have prior interview experience. It’s easier than you think to accidentally ask a leading question when coming up with questions on the fly. Overall, spontaneous questions are much more difficult than they may seem.

- Your research question is exploratory in nature. The answers you receive can help guide your future research.

An unstructured interview is the most flexible type of interview. The questions and the order in which they are asked are not set. Instead, the interview can proceed more spontaneously, based on the participant’s previous answers.

Unstructured interviews are by definition open-ended. This flexibility can help you gather detailed information on your topic, while still allowing you to observe patterns between participants.

However, so much flexibility means that they can be very challenging to conduct properly. You must be very careful not to ask leading questions, as biased responses can lead to lower reliability or even invalidate your research.

- You have a solid background in your research topic and have conducted interviews before

- Your research question is exploratory in nature, and you are seeking descriptive data that will deepen and contextualise your initial hypotheses

- Your research necessitates forming a deeper connection with your participants, encouraging them to feel comfortable revealing their true opinions and emotions

A focus group brings together a group of participants to answer questions on a topic of interest in a moderated setting. Focus groups are qualitative in nature and often study the group’s dynamic and body language in addition to their answers. Responses can guide future research on consumer products and services, human behaviour, or controversial topics.

Focus groups can provide more nuanced and unfiltered feedback than individual interviews and are easier to organise than experiments or large surveys. However, their small size leads to low external validity and the temptation as a researcher to ‘cherry-pick’ responses that fit your hypotheses.

- Your research focuses on the dynamics of group discussion or real-time responses to your topic

- Your questions are complex and rooted in feelings, opinions, and perceptions that cannot be answered with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’

- Your topic is exploratory in nature, and you are seeking information that will help you uncover new questions or future research ideas

Depending on the type of interview you are conducting, your questions will differ in style, phrasing, and intention. Structured interview questions are set and precise, while the other types of interviews allow for more open-endedness and flexibility.

Here are some examples.

- Semi-structured

- Unstructured

- Focus group

- Do you like dogs? Yes/No

- Do you associate dogs with feeling: happy; somewhat happy; neutral; somewhat unhappy; unhappy

- If yes, name one attribute of dogs that you like.

- If no, name one attribute of dogs that you don’t like.

- What feelings do dogs bring out in you?

- When you think more deeply about this, what experiences would you say your feelings are rooted in?

Interviews are a great research tool. They allow you to gather rich information and draw more detailed conclusions than other research methods, taking into consideration nonverbal cues, off-the-cuff reactions, and emotional responses.

However, they can also be time-consuming and deceptively challenging to conduct properly. Smaller sample sizes can cause their validity and reliability to suffer, and there is an inherent risk of interviewer effect arising from accidentally leading questions.

Here are some advantages and disadvantages of each type of interview that can help you decide if you’d like to utilise this research method.

The four most common types of interviews are:

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Semi-structured interviews : A few questions are predetermined, but other questions aren’t planned.

- Unstructured interviews : None of the questions are predetermined.

- Focus group interviews : The questions are presented to a group instead of one individual.

A structured interview is a data collection method that relies on asking questions in a set order to collect data on a topic. They are often quantitative in nature. Structured interviews are best used when:

- You already have a very clear understanding of your topic. Perhaps significant research has already been conducted, or you have done some prior research yourself, but you already possess a baseline for designing strong structured questions.

- You are constrained in terms of time or resources and need to analyse your data quickly and efficiently

- Your research question depends on strong parity between participants, with environmental conditions held constant

More flexible interview options include semi-structured interviews , unstructured interviews , and focus groups .

A semi-structured interview is a blend of structured and unstructured types of interviews. Semi-structured interviews are best used when:

- You have prior interview experience. Spontaneous questions are deceptively challenging, and it’s easy to accidentally ask a leading question or make a participant uncomfortable.

- Your research question is exploratory in nature. Participant answers can guide future research questions and help you develop a more robust knowledge base for future research.

An unstructured interview is the most flexible type of interview, but it is not always the best fit for your research topic.

Unstructured interviews are best used when:

- You are an experienced interviewer and have a very strong background in your research topic, since it is challenging to ask spontaneous, colloquial questions

- Your research question is exploratory in nature. While you may have developed hypotheses, you are open to discovering new or shifting viewpoints through the interview process.

- You are seeking descriptive data, and are ready to ask questions that will deepen and contextualise your initial thoughts and hypotheses

- Your research depends on forming connections with your participants and making them feel comfortable revealing deeper emotions, lived experiences, or thoughts

The interviewer effect is a type of bias that emerges when a characteristic of an interviewer (race, age, gender identity, etc.) influences the responses given by the interviewee.

There is a risk of an interviewer effect in all types of interviews , but it can be mitigated by writing really high-quality interview questions.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2022, October 10). Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 6 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/types-of-interviews/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, data collection methods | step-by-step guide & examples, face validity | guide with definition & examples, construct validity | definition, types, & examples.

- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Faculty of Arts & Sciences Libraries

Library Support for Qualitative Research

- Interview Research

- Resources for Methodology

- Remote Research & Virtual Fieldwork

Resources for Research Interviewing

Nih-funded qualitative research.

- Oral History

- Data Management & Repositories

- Campus Access

Types of Interviews

- Engaging Participants

Interview Questions

- Conducting Interviews

- Transcription

- Coding and Analysis

- Managing & Finding Interview Data

- UX & Market Research Interviews

Textbooks, Guidebooks, and Handbooks

- The Ethnographic Interview by James P. Spradley “Spradley wrote this book for the professional and student who have never done ethnographic fieldwork (p. 231) and for the professional ethnographer who is interested in adapting the author’s procedures (p. iv). Part 1 outlines in 3 chapters Spradley’s version of ethnographic research, and it provides the background for Part 2 which consists of 12 guided steps (chapters) ranging from locating and interviewing an informant to writing an ethnography. Most of the examples come from the author’s own fieldwork among U.S. subcultures . . . Steps 6 and 8 explain lucidly how to construct a domain and a taxonomic analysis” (excerpted from book review by James D. Sexton, 1980).

- Fundamentals of Qualitative Research by Johnny Saldana (Series edited by Patricia Leavy) Provides a soup-to-nuts overview of the qualitative data collection process, including interviewing, participant observation, and other methods.

- InterViews by Steinar Kvale Interviewing is an essential tool in qualitative research and this introduction to interviewing outlines both the theoretical underpinnings and the practical aspects of the process. After examining the role of the interview in the research process, Steinar Kvale considers some of the key philosophical issues relating to interviewing: the interview as conversation, hermeneutics, phenomenology, concerns about ethics as well as validity, and postmodernism. Having established this framework, the author then analyzes the seven stages of the interview process - from designing a study to writing it up.

- Practical Evaluation by Michael Quinn Patton Surveys different interviewing strategies, from, a) informal/conversational, to b) interview guide approach, to c) standardized and open-ended, to d) closed/quantitative. Also discusses strategies for wording questions that are open-ended, clear, sensitive, and neutral, while supporting the speaker. Provides suggestions for probing and maintaining control of the interview process, as well as suggestions for recording and transcription.

- The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research by Amir B. Marvasti (Editor); James A. Holstein (Editor); Jaber F. Gubrium (Editor); Karyn D. McKinney (Editor) The new edition of this landmark volume emphasizes the dynamic, interactional, and reflexive dimensions of the research interview. Contributors highlight the myriad dimensions of complexity that are emerging as researchers increasingly frame the interview as a communicative opportunity as much as a data-gathering format. The book begins with the history and conceptual transformations of the interview, which is followed by chapters that discuss the main components of interview practice. Taken together, the contributions to The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft encourage readers simultaneously to learn the frameworks and technologies of interviewing and to reflect on the epistemological foundations of the interview craft.

- The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods by Nigel G. Fielding, Raymond M. Lee and Grant Blank (Editors) Bringing together the leading names in both qualitative and quantitative online research, this new edition is organised into nine sections: 1. Online Research Methods 2. Designing Online Research 3. Online Data Capture and Data Collection 4. The Online Survey 5. Digital Quantitative Analysis 6. Digital Text Analysis 7. Virtual Ethnography 8. Online Secondary Analysis: Resources and Methods 9. The Future of Online Social Research

ONLINE RESOURCES, COMMUNITIES, AND DATABASES

- Interviews as a Method for Qualitative Research (video) This short video summarizes why interviews can serve as useful data in qualitative research.

- Companion website to Bloomberg and Volpe's Completing Your Qualitative Dissertation: A Road Map from Beginning to End, 4th ed Provides helpful templates and appendices featured in the book, as well as links to other useful dissertation resources.

- International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry Annual conference hosted by the International Center for Qualitative Inquiry at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, which aims to facilitate the development of qualitative research methods across a wide variety of academic disciplines, among other initiatives.

- METHODSPACE An online home of the research methods community, where practicing researchers share how to make research easier.

- SAGE researchmethods Researchers can explore methods concepts to help them design research projects, understand particular methods or identify a new method, conduct their research, and write up their findings. A "methods map" facilitates finding content on methods.

The decision to conduct interviews, and the type of interviewing to use, should flow from, or align with, the methodological paradigm chosen for your study, whether that paradigm is interpretivist, critical, positivist, or participative in nature (or a combination of these).

Structured:

- Structured Interview. Entry in The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methodsby Floyd J. Fowler Jr., Editors: Michael S. Lewis-Beck; Alan E. Bryman; Tim Futing Liao (Editor) A concise article noting standards, procedures, and recommendations for developing and testing structured interviews. For an example of structured interview questions, you may view the Current Population Survey, May 2008: Public Participation in the Arts Supplement (ICPSR 29641), Apr 15, 2011 at https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR29641.v1 (To see the survey questions, preview the user guide, which can be found under the "Data and Documentation" tab. Then, look for page 177 (attachment 8).

Semi-Structured:

- Semi-Structured Interview. Entry in The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methodsby Lioness Ayres; Editor: Lisa M. Given The semi-structured interview is a qualitative data collection strategy in which the researcher asks informants a series of predetermined but open-ended questions. The researcher has more control over the topics of the interview than in unstructured interviews, but in contrast to structured interviews or questionnaires that use closed questions, there is no fixed range of responses to each question.

Unstructured:

- Unstructured Interview. Entry in The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methodsby Michael W. Firmin; Editor: Lisa M. Given Unstructured interviews in qualitative research involve asking relatively open-ended questions of research participants in order to discover their percepts on the topic of interest. Interviews, in general, are a foundational means of collecting data when using qualitative research methods. They are designed to draw from the interviewee constructs embedded in his or her thinking and rationale for decision making. The researcher uses an inductive method in data gathering, regardless of whether the interview method is open, structured, or semi-structured. That is, the researcher does not wish to superimpose his or her own viewpoints onto the person being interviewed. Rather, inductively, the researcher wishes to understand the participant's perceptions, helping him or her to articulate percepts such that they will be understood clearly by the journal reader.

Genres and Uses

Focus groups:.

- "Focus Groups." Annual Review of Sociology 22 (1996): 129-1524.by David L. Morgan Discusses the use of focus groups and group interviews as methods for gathering qualitative data used by sociologists and other academic and applied researchers. Focus groups are recommended for giving voice to marginalized groups and revealing the group effect on opinion formation.

- Qualitative Research Methods: A Data Collector's Field Guide (See Module 4: "Focus Groups")by Mack, N., et al. This field guide is based on an approach to doing team-based, collaborative qualitative research that has repeatedly proven successful in research projects sponsored by Family Health International (FHI) throughout the developing world. With its straightforward delivery of information on the main qualitative methods being used in public health research today, the guide speaks to the need for simple yet effective instruction on how to do systematic and ethically sound qualitative research. The aim of the guide is thus practical. In bypassing extensive discussion on the theoretical underpinnings of qualitative research, it distinguishes itself as a how-to guide to be used in the field.

In-Depth (typically One-on-One):

- A Practical Introduction to in-Depth Interviewingby Alan Morris Are you new to qualitative research or a bit rusty and in need of some inspiration? Are you doing a research project involving in-depth interviews? Are you nervous about carrying out your interviews? This book will help you complete your qualitative research project by providing a nuts and bolts introduction to interviewing. With coverage of ethics, preparation strategies and advice for handling the unexpected in the field, this handy guide will help you get to grips with the basics of interviewing before embarking on your research. While recognising that your research question and the context of your research will drive your approach to interviewing, this book provides practical advice often skipped in traditional methods textbooks.

- Qualitative Research Methods: A Data Collector's Field Guide (See Module 3: "In-Depth Interviews")by Mack, N., et al. This field guide is based on an approach to doing team-based, collaborative qualitative research that has repeatedly proven successful in research projects sponsored by Family Health International (FHI) throughout the developing world. With its straightforward delivery of information on the main qualitative methods being used in public health research today, the guide speaks to the need for simple yet effective instruction on how to do systematic and ethically sound qualitative research. The aim of the guide is thus practical. In bypassing extensive discussion on the theoretical underpinnings of qualitative research, it distinguishes itself as a how-to guide to be used in the field.

Folklore Research and Oral Histories:

In addition to the following resource, see the Oral History page of this guide for helpful resources on Oral History interviewing.

American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress. Folklife and Fieldwork: A Layman’s Introduction to Field Techniques Interviews gathered for purposes of folklore research are similar to standard social science interviews in some ways, but also have a good deal in common with oral history approaches to interviewing. The focus in a folklore research interview is on documenting and trying to understand the interviewee's way of life relative to a culture or subculture you are studying. This guide includes helpful advice and tips for conducting fieldwork in folklore, such as tips for planning, conducting, recording, and archiving interviews.

An interdisciplinary scientific program within the Institute for Quantitative Social Science which encourages and facilitates research and instruction in the theory and practice of survey research. The primary mission of PSR is to provide survey research resources to enhance the quality of teaching and research at Harvard.