Social Darwinism Revisited: How four critics altered the meaning of a near-obsolete term, greatly increased its usage, and thereby changed social science

- Open access

- Published: 13 May 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Geoffrey M. Hodgson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5823-3996 1

325 Accesses

14 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Many social scientists still resist Darwinian insights. A possible reason for this is a fear of being associated with Social Darwinism. This article updates a 2002 search for appearances of Social Darwinism in articles and reviews on the JSTOR database. This database has since increased substantially in size, and it now includes far more publications in languages other than English. Use of the term Social Darwinism was rare before the 1940s. Talcott Parsons used it in 1932 to criticise the analytic use of the core Darwinian concepts in social science. Subsequently, and for the first time, Herbert Spencer and Willam Graham Sumner were described as Social Darwinists. This led to a major change of meaning of the term, where it was associated more, but not entirely, with free market individualism. With this reconstructed meaning, a 1944 bestselling book by Richard Hofstadter provoked an explosion of usage of the term in postwar years. The continuing use of the term is partly ideologically motivated and has served to deter consideration of Darwinian ideas in social science.

Similar content being viewed by others

The KOF Globalisation Index – revisited

Elite Theory

Neoclassical Economics: Origins, Evolution, and Critique

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

With notable exceptions, Darwinism is still resisted in much of social science. Footnote 1 There are several possible reasons for this, including appropriate scholarly reservations about the application of ideas of biological origin to social phenomena. However, such legitimate concerns are sometimes difficult to debate in a measured and informed way because of the widespread depiction of Darwinism by some social scientists as having reactionary, regressive, and even racist implications. Darwinism is thus avoided.

Related misgivings are found in evolutionary economics in the Schumpeterian tradition. Joseph Schumpeter avoided Darwinian concepts such as selection and wrote that for economists ‘no appeal to biology would be of the slightest use’ (Schumpeter 1954 , p. 789; Witt 2002 ). In their seminal work in this intellectual tradition, Richard Nelson and Sidney Winter ( 1982 ) actually deployed the core Darwinian concepts of variation, selection, and replication (of routines), but made no acknowledgement that these concepts were of Darwinian provenance. They mentioned Darwin only once in passing. Since this work and its massive influence, many evolutionary economists have been reluctant to make Darwinian ideas explicit. Footnote 2

Darwinian ideas are often covert. Consider two accounts of evolutionary approaches in economics and management by leading advocates. In Peter Murmann et al. ( 2003 ), Darwinism is mentioned only once, but the Darwinian concept of selection appears several times. In contrast, in the collection of essays edited by Richard Nelson et al. ( 2018 ), the concept of selection is mentioned merely as an aside, and it does not even appear in the index of the book. Given the prominence of the authors involved, these works suggest some reluctance to highlight or develop Darwinian ideas, despite their occasional employment. Footnote 3

It is not the purpose of this article to explore the pros or cons of adopting Darwinian ideas in evolutionary economics, or to consider reasons why social scientists are overly cautious about Darwinism. Except one. This is the possibility that caution about Darwinian ideas, in evolutionary economics and elsewhere, is motivated in part by worries of a backlash from critics of ‘Social Darwinism.’ The frequency and force of this motivation are difficult to assess empirically. However, there is enough anecdotal evidence to assume such concerns exist.

The aim here is not to rehabilitate or advocate any version of Social Darwinism. Instead, it is to reveal the mythology of Social Darwinism and to reduce inhibitions to more careful and well-grounded considerations of the value, or otherwise, of Darwinian ideas in the social sciences. Importantly, hardly anyone described their own views as ‘Social Darwinism’. Instead, it has been a label used by critics, but the objects of criticism are varied and have changed through time.

Many with worries that Darwinism may be dangerous for social science refer to ‘Social Darwinist’ ideas that grew up after the publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species in 1859. They cite nationalism, racism, and eugenics. Mike Hawkins ( 1997 , p. 282) even claimed that Adolf Hitler ‘showed a consistent adherence to the premises of Social Darwinism’. Such inflated accounts might suggest that Social Darwinism fuelled two world wars, stimulated Nazism and the Holocaust, and led to millions of deaths. No wonder Darwinism is verboten in parts of social science.

Since the 1940s, there has been an enhanced concern that ‘Social Darwinism’ implies individualism and competition, as well as other sins. Footnote 4 This narrative typically highlights Herbert Spencer and William Graham Sumner. Today, if we put the phrase ‘Social Darwinism’ into a Web search engine, then the name of Spencer appears in profusion. Spencer is regarded as the foremost ‘Social Darwinist’ and Sumner as his American deputy. There is no denying the impact of these two scholars. They were enormously influential in Anglo-American academia and beyond. The names of Spencer or Sumner are often cited, but their works are little read. In fact, neither Spencer nor Sumner used the term ‘Social Darwinism’. While they celebrated individualism and competition, they opposed nationalism, imperialism, and war. For reasons I raise below, the inclusion of Spencer and Sumner in the narrative on Social Darwinism can be challenged partly on the grounds that they were first included by its critics more than 60 years after the supposed emergence of Social Darwinism as a movement.

There is substantial literature that contests the standard story about ‘Social Darwinism’. ‘Revisionist’ scholars led by Robert Bannister ( 1979 ) pointed out that no group of thinkers labelling themselves as ‘Social Darwinists’ existed. There was no self-declared school promoting ‘Social Darwinism’. The label was almost universally used by critics to describe doctrinal opponents, of various kinds. Historical misrepresentations of basic facts, and the uncritical use of ‘Social Darwinism’ as a term of abuse, have served partisan political agendas, and have foreclosed scholarly discussion of the importance or otherwise of ideas from biology in helping to understand human behaviour and socio-economic evolution. Footnote 5

In 2004, I published a contribution to this debate (Hodgson 2004b ). I reported my 2002 searches for key terms related to ‘Social Darwinism’ in the large JSTOR database of academic journals and other relevant documents. Footnote 6 Apparently, this was the first time this database had been used to research Social Darwinism in this way. I concentrated on the history of the term and its meanings, rather than on the impact of Darwinism on social science and on political ideology. Both issues are important, but the second has received much more attention than the first. At that time, JSTOR had relatively little material in languages other than English. I confined my search to Anglophone journals. My main findings were as follows:

There were very few appearances of the terms ‘Social Darwinism’ or ‘Social Darwinist’ before 1930. My 2002 search found only 21 articles or reviews with appearances in over 77,000 items of relevance. While Darwin, Spencer and Sumner were all highly cited before 1930, the terms ‘Social Darwinism’ or ‘Social Darwinist’ were hardly ever used.

The only item found in the JSTOR database explicitly advocating ‘Social Darwinism’, in any sense whatsoever, was an early piece on eugenics by Colin Wells ( 1907 ), who also argued for a form of ‘individualism’. The American sociologist Lester F. Ward ( 1907 ) pointed out that Well’s usage of ‘Social Darwinism’ was different from that of others, who had mostly used the label in criticisms of racism or nationalism. Ward argued that racist views could not be legitimately derived from Darwinism.

The appearances up to 1939 largely involved critics of race struggle and belligerent nationalism. They accused others of ‘Social Darwinism’. Some of these early appearances are in reviews in English of books by Achille Loria ( 1895 , in Italian) and Jacques Novicow ( 1910 , in French). These volumes are critical of nationalism and racial conflict. After the outbreak of the First World War, two influential books in English by the US sociologist and pacifist George Nasmyth ( 1916 ) and the US philosopher Ralph Barton Perry ( 1918 ) saw nationalism, imperialism, and war as being aided by ‘Social Darwinism’. Perry further argued that theoretical intercourse between sociology and biology should be ended.

Following Perry and others who wanted to free social science from biology, Talcott Parsons gave the term ‘Social Darwinism’ new life and meaning. Parsons ( 1932 ) extended the usage of the term from its previous ideological associations with nationalism and racism to anyone who believed in ‘the application of Darwinian concepts of variation and selection to social evolution’. In this manner, Parsons helped to instigate the major revival and metamorphosis of the term ‘Social Darwinism’.

In strong contrast to prevailing accounts, neither Spencer nor Sumner were described as Social Darwinists before 1933. Sumner was first referred to as a Social Darwinist by Bernhard J. Stern ( 1933 ). Leo Rogin ( 1937 , p. 413) quoted the Soviet sociologist B. I. Smoulevitch ( 1936 , p. 95) who regarded Spencer as influenced by ‘Social Darwinism’. This gave the green light to others, eventually helping to transform the meaning of the term throughout Anglophone social science.

The leader of this transformation was the US historian Richard Hofstadter. He published an article entitled ‘William Graham Sumner, Social Darwinist’ (Hofstadter 1941 ). Therein he put Spencer in the same camp. Hofstadter’s ( 1944 ) Social Darwinism in American Thought transformed the discourse on the topic. Usage of the term ‘Social Darwinism’ (almost entirely by critics and rarely by proponents) increased exponentially in the literature.

Twenty years later, I repeated my explorations of the JSTOR database. Consequently, I can add some further arguments and reflections, and modify some aspects of my previous analysis. Four key players in the 1932–1944 period that I highlighted on my 2002 search, namely Hoftstadter, Parsons, Rogin and Stern, are shown in the present study to have an even more crucial role.

The JSTOR database has expanded considerably over 21 years. It now includes many more documents in languages other than English. It is no longer necessary to confine searches on this theme to English alone. These extended searches, particularly with French, Italian and German works included, enable us to find several more articles and reviews mentioning ‘Social Darwinism’ (as translated) up to 1939. In my 2002 search, I found 32 documents citing ‘Social Darwinism’ (in English) in this period. In 2023, I found 126 articles or reviews using the term up to 1939, a minority of which are in English. Although this is a substantial increase, it is miniscule in relation to the overall number of documents in the database in that period.

In 2002, I searched 502,411 ‘relevant’ articles or reviews in 1880–1989 inclusive. Footnote 7 In 2023, I searched 3,306,435 in the same period. This is more than a sixfold increase. Adding the 1870s, the 1990s, and the first decade of the new millennium, makes it more than an 11-fold increase. Repeating the search with a much larger database is a major test of my preceding analysis and assessment.

The multi-lingual search in 2023 did not undermine the principal conclusions of my preceding Anglophone study. ‘Social Darwinism’ was still a rare term, and almost always used in criticism. Reporting these new results is the first reason for my revisitation of this topic in this article. Not only is the database much larger, significantly more results are found in non-Anglophone territory.

The second reason for the present article is my growing concern that I had previously offered an inadequate explanation of the dramatic reinvention and re-entry of the term in the period from 1932 to 1944, and of its subsequent growth and persistence in usage. In this essay I have delved deeper. I offer some additional evidence and explanations. I revisit possible reasons for Parsons’s ( 1932 , 1937 ) view of Social Darwinism as (for him) a mistaken adoption of core Darwinian concepts in social science. I also explore the ideological and political context in which Stern and others paved the way for Hofstadter ( 1941 , 1944 ) to promote another new definition of Social Darwinism, which was different from Parsons’s, but it could complement and rest alongside it. These reconsiderations may help us understand the motives for continuing accusations and rebuttals of ‘Social Darwinism’ today.

The third reason concerns the methodology that was used in my 2004 article. Since then, I have come across other cases where researchers search for the appearance and usage of the terms in context, rather than starting with presupposed meanings and searching for them. This point may be of some relevance in studies of other key terms.

The rest of this article is structured as follows. Section two offers some brief reflections on the research methodology used in my JSTOR searches on this topic, in the light of two further instances by other authors since 2004. Section three looks at the period up to 1939, including appearances in the additional English and foreign language documents. Section four examines more closely the period from 1932 to 1944, focusing particularly on Parsons, Stern, Rogin and Hofstadter. The growth in usage of Social Darwinism in the second half of the 20th century forms the background of section five, which considers three selected exemplars – two from the 1950s and one from the 1990s – including what is possibly the most important postwar critical account of Social Darwinism (Hawkins 1997 ). Section six concludes the essay.

2 Should we search for a term, or for its imputed substance?

In 2002, I searched for the term ‘Social Darwinism’ (or ‘Social Darwinist’) rather than what might be imagined to be its meaning . Some critics suggested then that I should search for its presumed meaning(s) instead. My position, then as now, is that both approaches in the history of ideas are legitimate and useful. In Hodgson ( 2004b ), I cited an article by Matthias Klaes ( 2001 ) that offers some support for this inclusive stance.

At least in the case of Social Darwinism, there are serious problems with relying on searches for (attributed) meanings alone. As there was no school of self-proclaimed ‘Social Darwinists’ we must rely on how the term was used by its critics. My 2002 search found multiple conflicting meanings and emphases, with a new consensus arising in the 1940s, when the term became much more popular.

As criticisms of Social Darwinism continue to be published, a questionable procedure prevails in this genre. The researcher first assembles a set of traits that he or she considers to be the meaning of the term. These presumed traits might include nationalism, individualism, racism, eugenics, or whatever. With the presumed traits, a search is then conducted. Sure enough, we find what we are seeking. Writers are discovered who expressed nationalist, individualist, racist, eugenic, or other ideas. Or they use the selected catchphrases. These are labelled Social Darwinists, even if they did not use that term, or did not even mention Darwin.

There is no doubt that Darwin was influential. Hawkins ( 1997 , pp. 11–13) rightly pointed out that Darwinism inspired psychology and affected other behavioural sciences. He went further to argue that the influence of Darwinism shows that ‘Social Darwinism cannot be dismissed as marginal’. He also claimed that Darwinism does not have to be closely followed, or even acknowledged, for Social Darwinism to exist. Anyone affected by Darwinian ideas could be a Social Darwinist. And almost everyone was affected to some degree.

Hence, by such methods, we can conclude that Hitler was a Social Darwinist, although neither Darwin nor evolution is mentioned in Mein Kampf, and Hitler did not believe that human species evolved from apes (O’Connell and Ruse 2021 , p. 48). (His ideas on racial purity excluded the possibility of ape-like ancestors.) The wide application of the Social Darwinist label by Hawkins and others goes far beyond Nazism to include libertarian individualists, anti-nationalists and anti-militarists. Sumner is deemed a Social Darwinist, even though Sumner ( 1906 ) mentioned Darwin only once in his most important treatise. Sumner’s disciple Albert G. Keller ( 1923 , p. 137) remarked that his teacher ‘did not give much attention to the possibility of extending evolution into the societal field.’ Sumner is said to be a ‘Social Darwinist’ anyway. Spencer is convicted as well, while noting his coinage of the term ‘survival of the fittest’. The fact that Darwin adopted the term from Spencer is additional proof of Spencer’s guilt. By this method, we can often find the ‘world view’ or traits that we are looking for, but such an attempt to establish a meaning for Social Darwinism depends on partly arbitrary assumptions, picked in the present rather than carefully rooted in the past. With inadequate warrant for the chosen meaning, it depends on the presumptions of the researcher.

Jeffrey O’Connell and Michael Ruse ( 2021 ) used the same method of starting with a preconception of what Social Darwinism means. They added the stipulation that its exponents must believe in human evolution from primates, which ruled out Hitler, but not some other leading Nazis (pp. 48–50). They repeatedly used the phrase ‘traditional Social Darwinism’, as if its lineage were evident from the historical record. With whom did this tradition start? With Spencer of course. He sowed ‘the seeds of traditional social Darwinism’ (pp. 12–14), and these rapidly spread to American soil, with the ideas of academics such as William Graham Sumner and industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller. They also spread to Germany and inspired its military high command in the First World War (pp. 15–19). A problem neglected here is both Spencer and Sumner were strongly opposed to militarism, seeing it as a deadly extension of the power of the state, but that did not stop O’Connell and Ruse seeing ‘traditional social Darwinism’ as ‘triumphant’ in the early years of the 20th century. Another problem for them is that at the time of this triumph, neither Spencer nor Sumner had been described as Social Darwinists. That is unmentioned. Most primary uses of this relatively rare term were in writings in French or Italian. O’Connell and Ruse failed to cite these French and Italian sources. Yet it was in these languages that ‘Social Darwinism’ was then most used.

First take a preconception of what it means, and then find authors who fit. This method used alone, as employed by Hawkins, O’Connell, Ruse and others, constructs a history that is blinkered by contemporary concerns or prejudices. It has no answer to a rival retrospective attempt that might start from different preconceptions and then look back to find different thinkers. It simply finds instances that comply with its presumed ab initio search criteria.

Since 2004, the methodological argument against relying on presumption alone has been reinforced by searches for other key terms in the history of the social sciences. Consider the term ‘classical liberalism’. It is typically associated with early, free-market versions of liberalism, that understand liberty negatively as largely the absence of coercion, treat the individual as generally the best judge of his or her interests, emphasise rights over duties, under the guardianship of a minimal state. This account of ‘classical liberalism’ was promoted by writers such as Friedrich Hayek ( 1960 ), Milton Friedman ( 1955 ) and Ludwig Mises ([1927] 2005 ). They named early intellectuals who expressed such views, and they aligned themselves with this group. Other writers concur with this notion of ‘classical liberalism’, whether critical or otherwise of its substance.

As Helena Rosenblatt ( 2018 ) has shown, there are problems with this methodology. It paints the portrait before studying the fuller historical record. Given the scale and diversity of political and philosophical thought in the last three hundred years, it is quite conceivable that persons resembling the portrait can be found. However, problems are revealed if we choose a thinker such as Adam Smith, who is applauded by Hayek and others for his stress on individual incentives and markets. Other prominent features of his thought – including his extensive discussions of sympathy, justice, and moral sentiments – are given less emphasis, because they are absent from the preconceived portrait. This methodology, while it finds what it was seeking, becomes blind to much else. It has no answer to a rival retrospective attempt that might start from a different conception of ‘classical liberalism’ , and then look back to find thinkers that fit this different portrait.

Instead, Rosenblatt examined past usage of terms such as ‘liberal’ and ‘liberalism’ (and their equivalents in other languages). The views of writers who were the first to describe themselves politically as ‘liberals’ were often very different from the ‘classical liberalism’ described by Hayek, Friedman, and Mises. They stressed duties as well as rights. They rejected the notion that society could function wholly through self-interest. They warned of the dangers of selfishness. Most 19th-century liberals, whether British, French, or German, were not averse to government intervention. Her study dismantles the Hayek–Friedman–Mises historical mischaracterisation of ‘classical liberalism’.

The methodology of searching for a term, and then examining its usages and meanings, was also adopted by Taylor Boas and Jordan Gans-Morse ( 2009 ) in their study of the word ‘neoliberalism’. They found that it has been used in many ways. They produced bibliometric evidence revealing that relatively few authors attempted to define its meaning, even in academic publications. Even more than critics of ‘Social Darwinism’, critics of ‘neoliberalism’ lack consensus on what they are criticising. Searching for the usage of a term is again helpful and instructive.

3 Social Darwinism re-surveyed: 1877–1939

Hodgson ( 2004b ) claimed that that first appearance of the term ‘Social Darwinism’ was in an article by Oskar Schmidt ( 1879 ). The current JSTOR database contains an earlier mention by Fisher ( 1877 ). He discussed an analysis by Henry Maine and accused him of ‘Social Darwinism’. It is unclear what Fisher meant by this. More significantly, as I had found in 2002, in 1880 Émile Gautier published in Paris an anarchist tract entitled Le darwinisme social . Gautier argued that the true application of Darwinian principles to human society meant social cooperation rather than brutal competition. He used the term ‘Social Darwinism’ to criticize those who claimed to use Darwinian ideas to support capitalist competition and laissez faire. The term acquired other meanings, became established in France, and quickly spread to Italy (Clark 1985 ).

The 2023 JSTOR search, from 1877 to 1939 inclusive, found 126 articles or reviews using the term, only 37% of which are in English. Many of the items in English are reviews of French or Italian works that mention the term ‘Social Darwinism’. Such underlines the predominantly Continental European location of its usage before 1940, in languages other than English. This is another new result in the 2023 survey. Among the most influential were still Loria ( 1895 ) and Novicow ( 1910 ), who criticise nationalism, imperialist war, and race struggle. Although the 2023 search found additional references to ‘Social Darwinism’ in the 1920s and 1930s, they were still low in number. After rising to 23 in the first decade of the 20th century, non-Anglophone articles or reviews citing ‘Social Darwinism’ declined in number until the 1940s, reaching a low point of three in that decade. After its Continental heyday around the turn of the century, the enfeebled locus of criticism of ‘Social Darwinism’ shifted to the Anglophone world in the 1920s, but its progress there was at first extremely weak. There were 16 Anglophone articles or reviews citing ‘Social Darwinism’ in the 1920s and 14 in the 1930s. Despite its locational shift to (principally) the US, the global storyline about ‘Social Darwinism’ was in danger of petering out. The 2023 search confirms that the narrative was clearly in the doldrums. In English, French, German and Italian the term ‘Social Darwinism’ was very rare before 1940.

The massive increase in the JSTOR database, with its major extension of non-English texts, allows us to put more emphasis on the fact that mention of ‘Social Darwinism’ occurred in a mere few dozen items, which constitute only 0.016% of the entire ‘relevant’ corpus up to 1939. This strengthens the preceding, more cautious, suggestion that ‘Social Darwinism’ by the 1930s was almost a dead issue, occupying a tiny minority of minds. As now revealed, this decline is even more dramatic in the European Continental literature. By 1930, ‘Social Darwinism’ in the social sciences was an insignificant topic of discussion, for critics or likely advocates. If it were to be revived, it would have to be reinvented.

In the nadir of the 1930s, however, the seeds of its recovery were sown. During the Great Depression, many leading intellectuals would reflect on established ideas, and on the legitimacy of an economic system that had brought mass unemployment and impoverishment. Amid this crisis, ‘Social Darwinism’ would itself mutate. The changed object of criticism would highlight growing concerns, and the narrative on ‘Social Darwinism’ would be much more successful in its replication. After 1941, with the anti-capitalist Soviet Union installed as an ally in the global war against fascism, criticism of this re-invented Social Darwinism received a major boost.

4 Social Darwinism reinvented: 1932–1944

The intervention of Parsons ( 1932 ) was crucial. In a lengthy article on Alfred Marshall, Parsons mentioned Social Darwinism twice. Parsons ( 1932 , p. 325) briefly noted the application of Darwinian concepts to social science and a footnote described ‘the application of Darwinian concepts of variation and selection to social evolution’ as ‘Social Darwinism,’ giving obscure and unclear reasons for rejecting this line of thought, and without naming any of its proponents. Parsons rejected Social Darwinism because for him it meant the application of Darwinian concepts in the social sciences. Preceded by Perry ( 1918 ) and Woods ( 1920 ), Parsons ( 1932 ) made it an analytical as well as an ideological danger. His rising influence within sociology made this a lasting feature. Unlike the other three key players, his motives were solely analytical and academic, and neither ideological nor political.

Parsons simply focussed on the application of core Darwinian concepts such as variation and selection to the analysis of social change. Core Darwinian concepts of variation and selection might apply to individuals, groups, cultural memes, or other entities that cannot be understood solely in biological terms. Parsons’s prohibition would apply to these too.

For example, Thorstein Veblen’s ( 1899 , p. 188) analysis of the ‘natural selection of institutions’ or of ‘the fittest habits of thought’ would also, according to Parsons, be ‘Social Darwinism’. However, despite his explicit use of Darwinian ideas, Veblen is rarely described as a ‘Social Darwinist’. An exception is A. W. Coats ( 1954 , p. 532) who saw Veblen as adopting ‘an extreme form of Social Darwinism’. It is possible that, for many others, Veblen’s socialist sympathies (Hodgson 2023 ) exempted him from such a description. If so, this is evidence that accusations of ‘Social Darwinism’ were increasingly directed against defenders of capitalism and competition. However, Parsons was relatively unconcerned about these political issues.

In another footnote, Parsons ( 1932 , p. 341) wrote: ‘Pareto, like Marshall and Weber, sharply repudiates what he calls “Social Darwinism.”’ Parsons, however, gave no references and cited no rejection of Social Darwinism in their works. No explicit refutation exists in the works of these authors. Although Marshall ( 1920 ) mentioned Darwin a few times, it was not in repudiation. In fact, Marshall was an explicit devotee of the works of Spencer (Thomas 1991 ; Hodgson 1993 ), who today is widely but misleadingly described as a Social Darwinist. Parsons’s standards of scholarship were somewhat defective.

Parsons was a man with a mission. He used the term ‘Social Darwinism’ in his grand project to rebuild his discipline, and to establish boundaries between good and bad sociology. As well as placing Europeans, principally Karl Marx, Émile Durkheim and Max Weber, in the pantheon of sociological fame, Parsons wished to demote earlier American sociologists such as William G. Sumner, Lester F. Ward, Charles H. Cooley and Edward A. Ross. Despite their big analytical and ideological differences, they had all dallied with Darwinian ideas. With this rebuttal, Parsons did not distinguish between those Darwin-inspired American sociologists – notably Ward Footnote 8 – who opposed racism and eugenics, and others – such as Ross – who were racists or supporters of eugenics. Parsons condemned them all. He wanted to re-establish American sociology on an entirely different footing, free of biological concepts.

Parsons was not alone with these concerns. Arguments in favour of severing the links between the behavioural sciences and biology had gathered momentum in the early years of the 20th century (Degler 1991 ; Hodgson 2004a ). They were particularly notable in behaviourist psychology, founded by Watson ( 1914 , 1919 ), which emphasised social nurture much more than biological nature. Growing numbers of social scientists downplayed biological explanations, and went further, to sever all links with biology.

After Parsons’s intervention in 1932, the meaning of Social Darwinism widened. It had an additional purpose. It was applied not exclusively to doctrines of race struggle or war, but also to any application of Darwinism or related biological ideas to the study of human society.

Another major change occurred when Bernhard J. Stern ( 1933 ) became the first person to describe William G. Sumner as a Social Darwinist. Stern had established an academic reputation among American anthropologists and sociologists. In 1932 and 1937, Stern visited the Soviet Union and became an enthusiastic supporter of the regime. He was recruited by the US Communist Party. In 1936, he became one of the founders and editors of the Marxist social science journal, Science and Society . He applauded the 1938 trial of Nicolai Bukharin and accepted the Soviet explanation of the 1939 Hitler–Stalin pact (Kan 2021 ). After the war, he was a victim of McCarthyite persecution (Bloom 1990 ).

Four years after Stern had labelled Sumner as a Social Darwinist, Leo Rogin ( 1937 , p. 413), a Keynesian economist and sympathiser of the Soviet Union, uncritically quoted the Russian sociologist B. I. Smoulevitch ( 1936 , p. 95) who had seen Spencer as influenced by ‘Social Darwinism’. Footnote 9 Previously, Spencer had not been so described. Stern and Rogin gave the green light to others, thus further widening the meaning of the term. Both were respected and Rogin was particularly influential among US academics. Rogin taught and strongly influenced the economist John Kenneth Galbraith (Dimand and Koehn 2008 ) and the future Nobel Laureate in Economics Douglass C. North ( 2005 ).

This highly belated addition of Spencer and Sumner as Social Darwinists must be explained. More than previously, I would now emphasise the effect of the Great Depression, the growing criticism of capitalism among intellectuals at that time, and the growing sympathy for the Soviet Union, which to many seemed to be a superior economic system. Although Marx regarded Darwin as a great biologist, he rejected the application of Darwinian principles to social science. The stumbling block for Marxists and others was that Darwinism was seen as focusing on competition between individuals, as if the whole scientific credo was a byproduct of some version of 19th-century market liberalism. Petr Kropotokin ([1902] 1939) corrected this individualist interpretation and pointed to Darwin’s ( 1871 ) extensive discussion of cooperation and group selection in his Descent of Man. Even here, however, competition was still paramount, where the fitter human groups would be selected. Footnote 10 Competition generally was an anathema to Marxists and many other social scientists. It was associated with the capitalist system and its defects.

As an editor of Science and Society, Stern ( 1941a , p. 181) described statements by the US anthropologist Earnest Hooton as ‘antidemocratic, ruthless, social-Darwinian utterances’ that encourage ‘the development of the fascist ideology in the United States.’ Footnote 11 This stimulated several rejoinders in the pages of that journal, by eminent scholars including the leading biologist J. B. S. Haldane ( 1941 – then a Communist Party sympathiser). Haldane rejected the idea that Darwin was a racist. In his reply to Haldane, Stern ( 1941b , pp. 374–5) bemoaned:

the plethora of baneful apologetics of capitalism in the social science field that transfer the theory of natural selection into an analysis of man’s survival and status in capitalist society. … The social Darwinian sees only biological factors at work, and finds capitalism beneficially selective of superior stocks. Some … oppose making medical attention available to the poor on the grounds that it would help perpetuate inferior stocks. I contend that, since these writers have utilized Darwin’s theoretical principles in the field of social theory and apply the formula of natural selection to the problem of human survival, they may justly be called social Darwinian.

But despite the ‘plethora of baneful apologetics of capitalism’ in the social sciences, Stern cited none. Echoing Parsons ( 1932 ), Stern criticised anyone who applied ‘Darwin’s theoretical principles’ to the social sciences. Thereby Parsons’s account of Social Darwinism was amalgamated with the Marxist reinvention of Social Darwinian as a flawed defence of capitalism and competition.

In a further comment in Science and Society, by Emily R. Grace and M. F. Ashley Montagu ( 1940 ), appears a translation of an entry in ‘the latest Soviet philosophical dictionary’ (published in 1940): ‘ Social Darwinian: - is an incorrect transference of the law of the struggle for existence in the world of animals and plants, discovered by Darwin, to the sphere of social relationships, to the sphere of class struggle.’ The official Soviet dictionary then goes on to claim that this doctrine has been used to justify capitalism, imperialism, exploitation and racism. This shows that by 1940 the term was used in Soviet academia as part of its critique of capitalism. Footnote 12 This observation is all the more significant because in the 3 years from 1940 to 1942 inclusive the term ‘Social Darwinism’ was still rare in the literature. In JSTOR overall there were only 17 articles and reviews that contained the term (or similar) in those 3 years. Four of these were in Science and Society. A group of pro-Soviet Marxist intellectuals, who had experienced the economic collapse of the Great Depression, lit the fuse for the imminent explosion of usage of the term ‘Social Darwinism’.

Among the 17 articles and reviews in the 1940–42 period was Richard Hofstadter’s ( 1941 ) ‘William Graham Sumner, Social Darwinist’. Therein he also described Herbert Spencer as a Social Darwinist. Hofstadter had joined the US Communist Party in 1938 but left in the following year because of the Hitler–Stalin pact. Ideologically, he remained anti-capitalist for years. In a 1939 letter he declared: ‘I hate capitalism and everything that goes with it.’ In 1940, he claimed that studying Social Darwinism helped to explain ‘the disparity between our official individualism and the bitter facts of life as anyone could see them during the great depression.’ In 1944, he published Social Darwinism in American Thought. It was based on his 1938 PhD thesis. It has gone through several reprints and editions. It was reported in the 1992 edition that since 1955 it had sold 200,000 copies. Footnote 13

Hofstadter’s ( 1944 ) book was not intended as a systematic survey of the history of Social Darwinism. Instead, his chapters were a pick and mix of alleged proponents, critics, and their ideas. He relied almost entirely on secondary sources. He made no systematic searches for the term in the literature. Chapter one is on the impact of Darwinism. Chapter two is devoted to Spencer, followed by chapter three on Sumner. He thus depicted the rise of ‘Social Darwinism’ as first and foremost about selfish individualism and competition. Four chapters follow, relating largely to early critiques of Spencer, Sumner and of their celebrations of individualism, competition. and a minimal state. Discussion of eugenics occupies only seven pages in chapter eight – about one-third of that chapter. Then follows a substantial chapter on racism and imperialism, but it does not mention the fascism that was then storming Europe and East Asia. In his conclusion, Hofstadter ( 1944 , p. 203) wrote: ‘As a conscious philosophy, social Darwinism had largely disappeared by the end of the [First World] war.’ A few lines later he surmised: ‘A resurgence of social Darwinism, in either its individualist or imperialist uses, is always a possibility’. But he wrote as if fascism had not become a major threat, and the Second World War had not started. Neither fascism, Hitler, Mussolini nor Nazism appear in the index of the book.

On Social Darwinism and fascism, Hofstadter was slow off the mark. As noted previously, Stern ( 1941a ) had seen Social Darwinist utterances as encouraging fascism in the US. In book in the same year, William M. McGovern ( 1941 , p. 624) went further to claim that Nazism was based on Social Darwinism. This is possibly the first clear claim of this kind.

Hofstadter ( 1944 ) devoted foremost attention to the novel reconstruction of Social Darwinism, which accented individualism and competition, with Spencer and Sumner as its principal proponents. The neglect of the global war against fascism might have helped the promotion of the book as a scholarly retrospective on the history of Social Darwinism. It also served the purposes of the Soviet Union and its Western sympathisers to depict Social Darwinism as a celebration of individualism, competition and capitalism. There was enough of a narrative on imperialism and racism in Hofstadter’s book to remain pertinent during an anti-fascist war. There was nothing in the volume to stop others referring to Hitler and the Nazis as Social Darwinists.

Competitive, individualist versions of ‘Social Darwinism’ were identified and highlighted, thanks foremost to Hofstadter ( 1941 ) and to the accounts of others. From 1941 the Soviet Union was a vital ally. The criticisms of selfish individualism and competition were stimulated by the Great Depression and echoed the anti-capitalist ideology of the Soviet Union. The new, Marxist-inspired narrative on ‘Social Darwinism’, which emerged from the Great Depression, was adaptable enough to prosper during the Second World War. Attacks on ‘Social Darwinism’ for supporting militarism and war, which had been uppermost in 1914–1918, were given much less emphasis. They had to be muted for another reason. The newly acquired perpetrators of Social Darwinism, namely Spencer and Sumner, were themselves opponents of militarism and war.

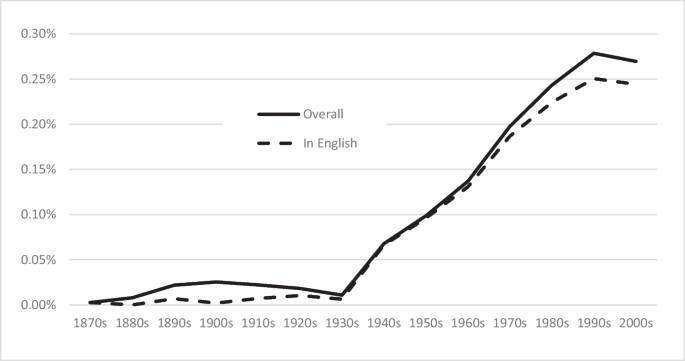

Figure 1 indicates the extent of the discourse on Social Darwinism from 1870 to 2009. For each decade, it shows JSTOR articles or reviews mentioning ‘Social Darwinism’ (with variants in English, and in other languages) as a percentage of all relevant JSTOR articles or reviews. Footnote 14 In the decades from the 1870s to the 1930s inclusive, ‘Social Darwinism’ was very rarely used, particularly in the Anglophone literature. From the beginning of the 20th century to the 1930s, its percentage significantly declined. Developments in the 1930s and early 1940s, including a substantial shift of meaning of the term, completely changed this trajectory. Thanks to Hofstadter ( 1944 ) and others, in the context of sympathy for the Soviet Union during a global anti-fascist war, usage of ‘Social Darwinism’ exploded.

Articles or reviews mentioning ‘Social Darwinism’ as a percentage of all relevant JSTOR articles or reviews (JSTOR searches conducted 31 July 2023. Searches in English, French, German or Italian)

5 After 1944: Some highlights

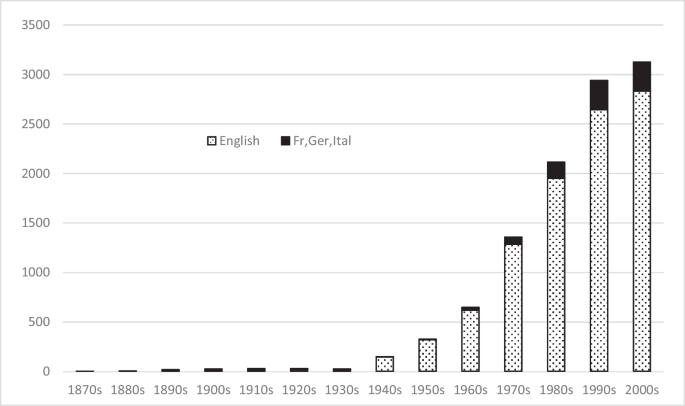

Figure 2 shows the huge upsurge from the 1940s in usage of the term ‘Social Darwinism’ (or equivalents in English, French, German or Italian). The figure shows the absolute numbers of articles or reviews involved. The explosion in usage from the 1940s to the 1990s is equally apparent.

Number of JSTOR articles or reviews in which ‘Social Darwinism’ appears (JSTOR searches conducted 31 July 2023. Searches in English, French, German and Italian)

Given the overall numbers involved, we can sample only a few instances for closer examination. Consider two appearances in the 1950s, which shortly followed the upsurge that started in 1944. In an article entitled ‘Darwin and Social Darwinism’, Gloria McConnaughey ( 1950 ) reflected the view of Parsons and others, which associates Social Darwinism with the use of Darwinian concepts in social science. McConnaughey ( 1950 , p. 397) opined: ‘All writers who have tried to explain politics and morals in terms of natural selection may, with some justice, be called Social Darwinists .’ She then turned to Darwin himself, making clear that he did not give ‘unqualified support to the racist school of anthropology, which postulates biologically superior races; his system of racial classification, rudimentary though it is, is based upon levels of culture’ (McConnaughey 1950 , p. 405). In her conclusion, she asked if Darwin was a Social Darwinist: ‘If by Social Darwinism we merely mean the application of natural selection to ethical and social problems, the answer is obviously yes. If, however, Social Darwinism is taken to refer to the strongly imperialistic, racist and anti-social-reform uses of natural selection, the answer is just as clearly no’ (McConnaughey 1950 , p. 412). Her reservations did not prevent the explosion in usage that was underway.

A few years later, the American sociologist and anthropologist George E. Simpson ( 1959 ) published an article also entitled ‘Darwin and “Social Darwinism”’. Rather than looking at the usage of the term itself, Simpson presumed what Social Darwinism meant and then found illustrative exemplars. Simpson ( 1959 , p. 34) wrote: ‘The application of Darwin's principle human society, with special emphasis on competition and struggle, became known as “Social Darwinism.”’ He then opined that this view was ‘endorsed by the advocates of unrestricted competition in private enterprise, the colonial expansionists, and opponents of voluntary social change.’ No examples were given. He then named the German biologist Ernst Haeckel as providing scientific sanction for these views. Simpson ( 1959 , p. 35) also declared: ‘Herbert Spencer and William Graham Sumner were prominent in advancing the doctrine of the social Darwinists.’ Given their prominence, it is strange that no-one named them as Social Darwinists before the 1930s. Simpson ( 1959 , p. 39) then went to discuss Hitler, concluding that ‘Hitlerism represents the most extreme variety of social Darwinism’. Less cautiously than McConnaughey, and notably on the centenary of Darwin’s ( 1859 ) Origin of Species , Simpson painted a wide picture of Social Darwinism that would resonate among subsequent authors in following decades. According to him, Social Darwinism could be found among libertarians such as Spencer and fascists such as Hitler. Simpson was not the only author to lump their hugely different views under the Social Darwinist heading. The new, widened meaning of the term that emerged in the 1932–1944 period has persisted ever since.

Meanwhile, in biology, a new synthesis between Darwinian principles and genetics was being strengthened (Fisher 1930 ; Wright 1931 ; Dobzhansky, 1937; Huxley 1942 ; Mayr 1942 ). The 1953 discovery of the structure of DNA encouraged further development of this synthesis, with spectacular scientific results. Consequently, within biology, Darwinism became the pre-eminent paradigm, after a period in the late 19th and early 20th century when it had been partially eclipsed (Bowler 1989 ). These developments were bound to affect the social sciences, and so they did. Consequently, the economists Armen Alchian ( 1950 ) and Milton Friedman ( 1953 ) deployed Darwinian selection in their work. Adolf Berle ( 1950 ) used Darwinian ideas in political analysis. A slow undercurrent of Darwinian references became apparent (Hayek 1960 , 1967 ; Campbell 1965 ; Boulding 1981 ). These prepared the ground in the 1990s for fuller developments of Darwinian ideas in socio-economic contexts. These would not be described as ‘Social Darwinism’ by their advocates. The ongoing critical rejection of ‘Social Darwinism’, however, would still inhibit their development.

As Fig. 2 shows, accusations Social Darwinism in the social sciences were unabated. One of the most serious critiques of Social Darwinism is the book by Hawkins ( 1997 ) on Social Darwinism in European and American Thought, 1860–1945. The remainder of this section is devoted to this important book. In some ways, Hawkins’ book is an impressive work of scholarship, covering many thinkers in the 18th and 19th centuries. In 2023, Hawkins’ book had 84 Citations on the Web of Science and 1067 on Google Scholar. It has had a relatively high impact. Footnote 15

Hawkins’ book received high praise from another critic of Social Darwinism. Richard Weikart ( 1997 ) pronounced that it ‘will surely become the standard work on the subject for some time to come. It is a superb corrective to the fairly popular revisionist interpretation of Social Darwinism propagated by Robert Bannister and others.’ Some other reviews were much more critical. Footnote 16

To Spencer, Sumner, Hitler and several others, Hawkins ( 1997 , pp. 11, 120–22, 175–) added unexpected recruits such as Willam James and John Dewey to his list of ‘Social Darwinists’. Their sins were to deploy Darwinian insights in psychology and social science, and to admit some biological influences on human nature. The list of Social Darwinists became longer and more varied.

Hawkins deals innovatively with the problem of wide ideological divergence and variety (from Spencer to Hitler) among the alleged adherents, by defining Social Darwinism as a ‘world view’ rather than as an ideology. This is an attempt to overcome the ideological diversity, from libertarianism to fascism, that has been gathered under the label of Social Darwinism and has thwarted past attempts to define it. According to Hawkins ( 1997 , p. 31), the world view of the Social Darwinists consisted of the following elemental beliefs:

biological laws governed the whole of organic nature, including humans;

the pressure of population growth on resources generated a struggle of existence among organisms;

physical and mental traits conferring an advantage on the possessors in this struggle (or in sexual competition), could, through inheritance, spread through the population;

the cumulative effects of selection and inheritance over time accounted for the emergence of new species and the elimination of others.’

Social Darwinists believed that ‘biological laws’ extend to ‘many (if not all) aspects of culture’ which ‘can be explained by the application of the first four elements’.

Element (i) is unclear. Hawkins referred to ‘biological laws’ without specifying what those laws are. There are no laws in biology that are equivalent in explanatory status to say, Newton’s laws in physics. There may be empirical regularities in biology, but these are often fallible or contingent. In this category fall the ‘laws of variation’ in chapter five of The Origin of Species. Darwin’s principal achievement was to develop an analytical framework that could be applied to biological populations. This framework highlighted variation, selection, and inheritance. To apply his theory, one had to bring in auxiliary explanations that were typically specific to the species and circumstances involved. Darwin did this repeatedly in his works.

It is also unclear what Hawkins is trying to reject in (i). Is he rejecting the belief (a) that biology determines (almost) everything in human society, or rejecting the weaker notion (b) that biology affects or constrains human capacities and behavioural outcomes? While some passages suggest the possibility of a more nuanced approach, Hawkins seems to reject both (a) and (b). This implies that biology can play no significant part in explanations of human phenomena. Human behaviour would be seen as entirely dependent on culture. There is no dual inheritance (Boyd and Richerson 1985 ) or any other mixed position. The (almost) all-culture view is not unique to Hawkins. It is still prevalent in sociology, but there must be some major biological and physical constraints on human capacities. To a large degree, these will be dependent on nutritional, social and environmental factors, but nature and biology also place limits on these capacities.

Element (ii) is a distortion of Darwinism. While forming his ideas, Darwin was influenced by Malthus on the issue of population pressure, but that is not the only reason for ‘the struggle for existence’. Darwin ( 1859 , ch. 3) used the concept in what he termed a ‘wide sense’. It referred broadly to efforts to obtain the means of life, flourishing and procreation. Alongside population pressure, Darwin included other factors, including access to food, the effects of predators, and adverse (seasonal or long-term) shifts in the climate. Darwin’s concept of the ‘struggle for existence’ involves any circumstance that limits the flourishing or fecundity of a species. Malthusian population pressure was just one possibility, among many others.

Hawkins blamed the concept of natural selection for many ills of Social Darwinism. Darwinian selection occurs because members of populations differ in their capacities to endure, survive and pass on key information and capacities to their progeny. Importantly, the occurrence of natural selection provides no warrant for presuming that the processes or outcomes are morally acceptable or superior . So why was Hawkins so hostile to the concept?

The crucial element (v) is related to Hawkins’ ( 1997 , p. 31) claim that human ‘culture cannot be reduced to biological principles’. This may be construed as a (reasonable) rejection of the idea that we can human cultural phenomena solely in biological terms. But Hawkins suggests more. Without mentioning him by name, Hawkins followed the prohibition by Parsons ( 1932 , 1937 ) on the use of core Darwinian concepts in social science. Hawkins noted that several ‘Social Darwinists’ considered entities other than genes as objects of selection. But he did not elaborate on the possibility that concepts such as variation, selection and inheritance could be applied to socio-economic evolution without endorsing explanations in terms of biological factors alone. Among others, works by Veblen ( 1898 , 1899 ), Keller ( 1915 ) and Donald T. Campbell ( 1965 ) applied Darwinian principles to human institutions and culture. None of these authors is mentioned by Hawkins.

Hawkins does mention Petr A. Kropotkin. The author of Mutual Aid is depicted as a well-intentioned progressive who fell victim to dangerous Darwinian ideas. Hawkins ( 1997 , p. 179) tried to rescue the Russian by questioning the Darwinian provenance of Kropotkin’s promotion of cooperation. Hawkins tells us that mutual aid was ‘not, for him, a consequence of natural selection as it was for the Darwinists’. This is patently false. Kropotkin ( 1939 , p.14) saw the principle of mutual aid as ‘nothing but a further development of ideas expressed by Darwin himself in The Descent of Man.’ In contrast to Hawkins’ inaccurate depiction of natural selection as always competitive or individualistic, Kropotkin ( 1939 , p. 72) insisted that ‘competition is not the rule either in the animal world or in mankind. It is limited among animals to exceptional periods, and natural selection finds better fields for its activity … natural selection continually seeks out the ways precisely for avoiding competition as much as possible.’ By Hawkins’ criteria, Kropotkin was a Social Darwinist. But Hawkins is reluctant to describe him as such, seemingly because Kropotkin was politically on the left.

Hawkins endorsed Marx and Engels, who rejected the application of Darwinian ideas to human society. But on occasions they would seem invoke them. In a famous passage in the German Ideology Marx and Engels ( 1976 , pp. 41–2) pointed out that human life ‘involves before everything else eating and drinking, housing, clothing and various other things.’ Although the difficulties involved in obtaining these means of life will vary enormously in time and space, some effort – great or small – is always involved. Admitting this would be a recognition of a universal struggle for existence. Given that the German Ideology was written over a decade before Darwin’s Origin, it would give Marx and Engels precedence. A ‘struggle for existence’ is found in early Marxism.

On 16 January 1861, shortly after The Origin of Species appeared, Marx wrote to Ferdinand Lassalle: ‘Darwin’s work is most important and suits my purpose in that it proves a basis in natural science for the historical class struggle.’ On 18 June 1862, Marx wrote to Engels: ‘It is remarkable how Darwin rediscovers, among the beasts and plants, the society of England with its division of labour, competition, opening up of new markets, “inventions,” and Malthusian “struggle for existence” … in Darwin, the animal kingdom figures as civil society.’ In these two letters Marx clearly indicated that Darwinian principles have some resonance, even relevance, for the understanding of the class struggle and modern society. Footnote 17

As noted by Hawkins ( 1997 , p. 152), there is a later passage where Engels claimed explicitly that Darwinian ideas were applicable a fortiori to capitalism. Engels wrote that capitalism entails ‘the Darwinian struggle of the individual for existence transferred from Nature to society with intensified violence. The conditions of existence natural to the animal appear as the final term of human development’ (Marx and Engels 1962 , vol. 2, p. 143). This seems to admit that capitalism (at least) can be analysed in part with the help of Darwinian concepts. But by the criteria of Parsons ( 1932 ) and Hawkins ( 1997 ), the use of Darwinian concepts in the analysis of any socio-economic system would suggest an adoption of Social Darwinism. So were Marx or Engels Social Darwinists?

Hawkins seemed aware of this possible question. He defended Marxism from the accusation of Social Darwinism by pointing out that capitalism is historically specific, and that under socialism the struggle for existence would ‘be transcended’. But he offered no explanation how. Imagining some unclearly specified future where people supposedly no longer face any struggle to exist does not get Marx and Engels off the hook. It would be necessary to explain how socialism worked, and how it would provide for everyone the means of life, apparently with little effort on their part. Contrary to Hawkins, the invocation of the word ‘socialism’ and its alleged marvels does not provide Marxism with a ‘Get Out of Social Darwinism Free’ card. Perhaps Marx and Engels share enough of the ‘world view’ to be classified as Social Darwinists?

Hawkins’ extensive account of Social Darwinism contains a number of serious analytical flaws. His biased account of Darwinian principles makes them less flexible and palatable for the social scientist. His ameliorating treatment of Kropotkin, Marx and Engels betrays the underlying ideological current in his book. Hawkins followed others by using Social Darwinism as an accusation against social scientists inspired by Darwinian ideas, fearing especially that they might lead to defences of markets and competition. From 1944 onwards the attack on ‘Social Darwinism’ became more of a leftist crusade, with creationists and other anti-Darwinists cheering on the sidelines. By shunning powerful modes of explanation of complex evolutionary phenomena in the socio-economic sphere, it has stunted the development of the social sciences.

6 Conclusion

It is shown here that before 1944 Social Darwinism was a rare term, almost entirely used by critics rather than proponents. It most prominent early usages were by Continental European critics of militarism, imperialism and war, writing in French or Italian. In the United States, from 1932 to 1944 the term underwent a major reconstruction of meaning. Parsons ( 1932 ) used the term to describe anyone who used core Darwinian concepts in social science. He wanted to exclude previous US sociologists who had been influenced by Darwinism from his recasting of sociological theory. Also at this time, the Great Depression led to disillusion with capitalism and greater sympathy for the planned economic system pioneered in the Soviet Union. Three Soviet sympathisers – Hofstadter, Rogin and Stern – described Spencer or Sumner as Social Darwinists. The competitive individualism promoted by Spencer and Sumner was seen as partly responsible for mass unemployment in the 1930s.

In his seminal book on Social Darwinism, reflecting his hostility to capitalism and individualism, Hofstadter put Spencer and Sumner first, before mentioning the alleged role of Social Darwinism in promoting eugenics, imperialism and racism. This reinvention of Social Darwinism, describing a wide range of ills from selfish individualism to fascism, and prohibiting any use of Darwinian concepts in social science, proved extraordinarily successful. Usage of the term exploded, to relative and absolute frequencies far higher than they were before the Second World War. This had a major effect on the development of social science. The reinforcement of barriers between Darwinism and the social sciences significantly affected the development of the latter.

Subsequently, with some notable exceptions, the use of Darwinian principles was avoided. After important developments in biology in the 1930s and 1940s, which synthesized genetics with a resurgent Darwinism, in the 1950s a few influential scholars promoted some Darwinian ideas in economics and politics. But, partly because of the unabating rejection of a supposed previous ‘Social Darwinism’, these approaches were subject to little further development. An exceptional, more detailed and important development of Darwinian ideas in the social sciences was by Campbell ( 1965 ). But even after that, progress was slow. In the 1980s and after, the deployment of Darwinian ideas in the social sciences became further systematized and generalized, particularly after key developments in the philosophy of biology. Footnote 18

It is easy to dismiss these more recent attempts as ‘Social Darwinist’. In the past, such rejections were based typically on ideology and prejudice, and not on any careful consideration of what these approaches might offer. Detailed critical discussion of the value or otherwise of Darwinian principles must proceed in a context where dismissive accusations of ‘Social Darwinism’ are more thoroughly scrutinized.

Data availability

The data reported in this article are available from its author on request.

This article originated in a webinar on ‘Social Darwinism: Myth or Menace’ involving the Darwin Club for Social Science on 13 March 2023. As well as anonymous referees, I thank the webinar participants and in particular Marion Blute for their comments.

Among the exceptions are Metcalfe ( 1998 ) and Andersen ( 2004 ).

The development of Darwinian ideas in evolutionary economics has been the subject of debate. See for example Cordes ( 2006 ), Hodgson ( 2007 ), Witt ( 2008 ), Dollimore and Hodgson ( 2014 ), and Hodgson ( 2019 ).

As noted below, this neglects Darwin’s ( 1871 ) account of human cooperation.

See also the revisionist criticisms of Jones ( 1980 ), Bellomy ( 1984 ), Claeys ( 2000 ), Crook ( 1994 , 1996 ), Leonard ( 2009 ) and others.

Hodgson ( 2004b ) was reprinted in Hodgson ( 2006 ). I should identify an error in my earlier article and its reprint. A passage (Hodgson 2004b , p. 446; 2006, p. 53) suggests that Hofstadter saw Lester F. Ward as a Social Darwinist. He did not.

A ‘relevant’ JSTOR article or review is defined as one that contains ‘human’ OR ‘social’ OR ‘societ*’ OR ‘econom*’, where * is a wildcard. My 2023 searches included ‘Social Darwinism’, ‘Social Darwinist’ and ‘Social Darwinian’. Concerning my 2023 searches, ‘Social Darwinism’ includes all three variants. The 2023 JSTOR searches were completed on 31 July.

Ward ( 1913 ) criticised eugenics.

Rogin ( 1937 , p. 414) saw the USSR as adhering ‘to a democratic utilitarian ethics – one which says that the hungry should be fed, the sick healed, and the dead decently buried.’ This evaluation is difficult to reconcile with the Soviet famine of 1930–33, where about 7 million people died because of Stalin’s policies (Conquest 1986 ).

There is a large literature on group selection including Sober and Wilson ( 1998 ) and Henrich ( 2004 ).

Stern’s ( 1941a ) strictures against racism were no doubt genuine. But he was an apologist for Stalin’s oppressive policies against ethnic minorities (Stern 1944 ; Kan 2021 ). Stern might have invented the term ‘Social Darwin ian ’, as it does not appear earlier. I omitted this variant from my 2002 search, but it was fully incorporated in the 2023 search reported here.

In the USSR, the rise of Lysenko’s quasi-Lamarckian doctrine in the 1930s (Joravsky 1970 ) made opposition to Darwinism state policy, alongside a foundational opposition to capitalism and individualism. Was the revived campaign after 1936 in the West against ‘Social Darwinism’ partly orchestrated by the Soviet authorities, using their sympathisers in the US? As yet, there is no clear evidence to support an affirmative answer.

Hofstadter ( 1944 ). Quotes are from the introduction by Eric Foner to Hofstadter ( 1992 , pp. x-xiv).

See the definition of ‘relevant’ in a preceding footnote.

The searches were conducted on 28 June 2023.

Weikart’s ( 2004 ) book on Darwin to Hitler was criticised by Gooday et al. ( 2008 ). The book received ‘crucial funding’ from the Discovery Institute’s Center for Science and Culture, in Seattle, which funds works on intelligent design (Weikart 2004 , p. x). Johnson’s ( 1998 ) critical review of Hawkins ( 1997 ) saw it as ‘a deeply biased presentation of scientific and intellectual history in the service of a political agenda. The author demonstrates considerable erudition, but it is an erudition contaminated by his ideological commitments.’

Marx and Engels ( 1985 , pp. 246-7, 381). Note that the claim that Marx sought permission from Darwin to dedicate a volume of Capital to him is a myth (Feuer 1975 ; Fay 1978 ; Colp 1982 ).

Campbell ( 1965 ). See for example Sober ( 1984 ), Hull ( 1988 ), Sterelny et al. ( 1996 ) and Hodgson and Knudsen ( 2010 ).

Andersen ES (2004) Population thinking, price’s equation and the analysis of economic evolution. Evol Inst Econ Rev 1(1):127–148

Alchian AA (1950) Uncertainty, evolution, and economic theory. J Pol Econ 58(2):211–22

Article Google Scholar

Bannister RC (1979) Social Darwinism; Science and Myth in Anglo-American Social Thought. Temple University Press, Philadelphia

Google Scholar

Bellomy Donald C (1984) “Social Darwinism” Revisited. Perspectives in American History, New Series 1:1–129

Berle AA (1950) Natural Selection of Political Forces (Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press)

Bloom SW (1990) The Intellectual in a time of Crisis: The Case of Bernhard J. Stern, 1894–1956. J History Behav Sci 26(1):17–37

Boas TC, Gans-Morse J (2009) Neoliberalism: From New Liberal Philosophy to Anti-Liberal Slogan. Stud Comp Int Dev. 44(2):137–161

Boulding KE (1981) Evol Econ (Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications)

Bowler PJ (1989) Evolution: The History of an Idea. University of California Press, Berkeley

Boyd R, Richerson PJ (1985) Culture and the Evolutionary Process. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Campbell DT (1965) Variation, Selection and Retention in Sociocultural Evolution. In: Barringer HR, Blanksten GI, Mack RW (eds) (1965) Social Change in Developing Areas: A Reinterpretation of Evolutionary Theory. Schenkman, Cambridge, MA, pp 19–49

Claeys G (2000) The “Survival of the Fittest” and the Origins of Social Darwinism. J History Ideas 61(2):223–40

Clark LL (1985) Social Darwinism in France. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa

Coats AW (1954) The Influence of Veblen’s Methodology’. J Polit Econ.62(6): 529–37

Colp R (1982) The Myth of the Marx-Darwin Letter. History Pol Econ. 14(4):416–82

Conquest R (1986) The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Cordes C (2006) Darwinism in Economics: From Analogy to Continuity. J Evol Econ, 16(5):529–41

Crook P (1994) Darwinism, War and History: The Debate over the Biology of War from the ‘Origin of Species’ to the First World War. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book Google Scholar

Crook P (1996) Social Darwinism: The Concept. History Euro Ideas 22(4):261–74

Darwin Charles R (1859) On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, 1st edn. John Murray, London

Darwin CR (1871) The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, 1 st edn., 2 vols (London: John Murray and New York: Hill).

Degler CN (1991) In Search of Human Nature: The Decline and Revival of Darwinism in American Social Thought. Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York

Dimand RW , Koehn RH (2008) Galbraith’s Heterodox Teacher: Leo Rogin’s Historical Approach to the Meaning and Validity of Economic Theory. J Econ Issues. 42(2):561–568

Dollimore D, Hodgson GM (2014) Four Essays on Economic Evolution: An Introduction. J Evol Econ . 24(1):1–10

Fay MA (1978) Did Marx Offer to Dedicate Capital to Darwin? J History Ideas. 39(1):133–46

Feuer LS (1975) Is the Darwin-Marx Correspondence Authentic? Annals Sci 32:11–12

Fisher J (1877) The History of Landholding in Ireland. Trans Royal Hist Soc 5:228–326

Fisher RA (1930) The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Friedman M (1953) The Methodology of Positive Economics. in M. Friedman, Essays in Positive Economics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), pp. 3–43

Friedman M (1955) Liberalism, Old Style, Collier’s Year Book (New York: Collier) pp. 360–3

Gooday G, Lynch JM, Wilson KG, BarskyCK (2008) Does Science Education Need the History of Science. Isis. 99(2):322–30

Grace ER, Montagu MF, Ashley (1940) More on Social Darwinism. Sci Soc 6(1):71–78

Haldane JBS (1941) Concerning Social Darwinism. Sci Soc 5(4):373–374

Hawkins M (1997) Social Darwinism in European and American Thought, 1860–1945: Nature as Model and Nature as Threat. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hayek FA (1960) The Constitution of Liberty. Routledge and Kegan Paul, and University of Chicago Press, London and Chicago

Hayek FA (1967) ‘Notes on the Evolution of Systems of Rules of Conduct’, from Hayek, Friedrich A. (1967) Studies in Philosophy, Politics and Economics. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London

Henrich J (2004) Cultural Group Selection, Coevolutionary Processes and Large-Scale Cooperation. J Econ Behav Org. 53(1):3–35

Hodgson GM (1993) Economics and Evolution: Bringing Life Back Into Economics (Cambridge, UK and Ann Arbor, MI: Polity Press and University of Michigan Press).

Hodgson GM (2004) The Evolution of Institutional Economics: Agency, Structure and Darwinism in American Institutionalism. Routledge, London and New York

Hodgson GM (2004b) Social Darwinism in Anglophone Academic Journals: A Contribution to the History of the Term. J Hist Soc. 17(4):428–63

Hodgson GM (2006) Economics in the Shadows of Darwin and Marx: Essays on Institutional and Evolutionary Themes. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Hodgson GM (2007) A Response to Christian Cordes and Clifford Poirot. J Econ Issues. 41(1):265–76

Hodgson GM (2019) Evolutionary Economics: Its Nature and Future, in a series edited by John Foster and Jason Potts: Cambridge Elements in Evolutionary Economics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York

Hodgson GM (2023) Thorstein Veblen and Socialism. J Econ Issues 57(4):1162–77

Hodgson GM, Knudsen T (2010) Darwin’s Conjecture: The Search for General Principles of Social and Economic Evolution. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Hofstadter R (1941) ‘William Graham Sumner. Social Darwinist’, New England Quarterly 14:457–77

Hofstadter R (1944) Social Darwinism in American Thought, 1860–1915, 1st edn. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia

Hofstadter R (1992) Social Darwinism in American Thought, revised edn. with an introduction by Eric Foner. Beacon Press, Boston

Hull DL (1988) Science as a Process: An Evolutionary Account of the Social and Conceptual Development of Science. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Huxley J (1942) Evolution: The Modern Synthesis, 1st edn. Wiley, New York

Johnson GR (1998) Review of Social Darwinism in European and American Thought, 1860–1945: Nature as Model and Nature as Threat by Mike Hawkins. Am Pol Sci Rev. 92(4):930–932.

Jones G (1980) Social Darwinism and English Thought (Brighton, NJ and Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Harvester and Humanities Press)

Joravsky D (1970) The Lysenko Affair (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press)

Kan SA (2021) Bernhard J. Stern, an American Apologist for Stalinism’, History of Anthropology Review, 25 February. https://histanthro.org/notes/bernhard-j-stern-an-american-apologist-for-stalinism/ . Retrieved 31 July 2023.

Keller AG (1915) Societal Evolution: A Study of the Evolutionary Basis of the Science of Society. Macmillan, New York

Keller AG (1923) Societal Evolution. In: Baitsell GA (ed) The Evolution of Man. Yale University Press, New Haven, pp 126–51

Klaes M (2001) Begriffsgeschichte : Between the Scylla of Conceptual and the Charybdis of Institutional History of Economics. J Hist Econ Thought 23(2):153–79

Kropotkin PA (1939) Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, 1 st edn. 1902. Penguin, Harmondsworth

Leonard TC (2009) Origins of the Myth of Social Darwinism: The Ambiguous Legacy of Richard Hofstadter’s Social Darwinism in American Thought. J Econ Behaviour Organ 71(1):37–51

Loria A (1895) Problemi Sociali Contemporanei. Kantorowicz, Milano

Mayr E (1942) Systematics and the Origin of Species. Columbia University Press, New York

Marshall A (1920) Principles of Economics: An Introductory Volume, 8th edn. Macmillan, London

Marx K, Engels F (1962) Selected Works in Two Volumes. Lawrence and Wishart, London

Marx K, Engels F (1976) Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works, Vol. 5, Marx and Engels: 1845–1847 (London and New York: Lawrence and Wishart and International publishers)

Marx K, Engels F (1985) Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works, Vol. 41, Letters 1860–1864 (London: Lawrence and Wishart)

McConnaughey G (1950) Darwin and Social Darwinism. Osiris 9:397–412

McGovern WM (1941) From Luther to Hitler; The History of Fascist-Nazi Political Philosophy. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

Mises L (2005) Liberalism: The Classical Tradition, translated from the German edition of 1927. Liberty Fund, Indianapolis

Metcalfe JS (1998) Evolutionary Economics and Creative Destruction. Routledge, London and New York

Murmann JP, Aldrich HE, Levinthal D, Winter SG (2003) Evolutionary Thought in Management and Organization Theory at the Beginning of the New Millennium: A Symposium on the State of the Art and Opportunities for Future Research. J Manag Inquiry. 12(1):22–40

Nasmyth G (1916) Social Progress and Darwinian Theory: A Study of Force as a Factor in Human Relations. Putnam, New York and London

Nelson RR, Dosi G, Helfat C, Pyka A, Saviotti Pier Paolo, Lee K, Dopfer K, Malerba F, Winter S (eds) (2018) Modern Evolutionary Economics: An Overview. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York

Nelson RR, Winter SG (1982) An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

North DC (2005) Biographical, The Nobel Prize . https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/1993/north/biographical/ . Retrieved 27 April 2023.

Novicow J (1910) La critique du darwinisme social. Alcan, Paris

O’Connell J, Ruse M (2021) Social Darwinism. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York

Parsons T (1932) Economics and Sociology: Marshall in Relation to the Thought of his Time. Quart J Econ. 46(2):316–47

Parsons T (1937) The Structure of Social Action, 2 vols. McGraw-Hill, New York

Perry RB (1918) The Present Conflict of Ideals: A Study of the Philosophical Background of the World War. Longmans Green, New York

Rogin L (1937) Review of Bourgeois Population Theory: A Marxist-Leninist Critique. Am Econ Rev. 27(2):412–14

Rosenblatt H (2018) The Lost History of Liberalism: From Ancient Rome to the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ and Oxford UK

Schmidt O (1879) Science and Socialism. Popular Science 14:557–91

Schumpeter JA (1954) Economic Doctrine and Method: An Historical Sketch, translated from the German edition of 1912 by R. Aris. Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York

Simpson GE (1959) Darwin and “Social Darwinism”. Antioch Rev. 19(1):pp. 33–45

Smoulevitch BI (1936) Burzuazny e teorii narodonaselenija v svete Marksistko-Leninskoj kritikii) (Bourgeois Population Theory: A Marxist-Leninist Critique). Gosoodarstvennoie Sozialno-Ekonomiches-koie Izdatielstvo, Moscow

Sober E (1984) The Nature of Selection: Evolutionary Theory in Philosophical Focus (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

Sober E, Wilson DS (1998) Unto Others: The Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

Sterelny K, Smith KC, Dickison M (1996) The Extended Replicator. Biol Phil 11:377–403

Stern BJ (1933) Sumner, William Graham. In: Edwin R. A. Seligman and Alvin Johnson (eds) Encyclopaedia of the Social Sciences (New York: Macmillan), Vol. 9, p. 463.

Stern BJ (1941a) Recent Literature of Race and Culture Contacts. Sci Soc. 5(2):173–188

Stern BJ (1941) Reply by Bernard J. Stern. Sci Soc 5(4):374–375

Stern BJ (1944) Soviet Policy on National Minorities. Am Sociol Rev 9(3):229–235

Sumner WG (1906) Folkways: A Study of the Sociological Importance of Usages, Manners, Customs, Mores and Morals. Ginn, Boston

Thomas B (1991) Alfred Marshall on Economic Biology. Rev Pol Econ. 3(1): 1–14

Veblen TB (1898) Why Is Economics Not an Evolutionary Science? Quarterly J Econ.12(3):373–97

Veblen TB (1899) The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study in the Evolution of Institutions. Macmillan, New York

Ward LF (1907) Discussion. Am J Soc 12(5):709–710

Ward LF (1913) Eugenics, Euthenics, and Eudemics. Am J Soc. 18(6):737–54

Watson JB (1914) Behavior: A Textbook of Comparative Psychology. Henry Holt, New York

Watson John B (1919) Psychology from the Standpoint of a Behaviorist. J. B. Lippincott, Philadelphia

Weikart R (1997) Review of Mike Hawkins, Social Darwinism in European and American Thought, 1860–1945: Nature as Model and Nature as Threat, H-NEXA, H-Net Reviews. September , https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=1305 . Retrieved 4 August 2023

Weikart R (2004) Darwin to Hitler: Evolutionary Ethics, Eugenics, and Racism in Germany. Palgrave Macmillan, London and New York

Wells DC (1907) Social Darwinism. Am J Soc. 12(5):695–708

Witt U (2002) How Evolutionary is Schumpeter’s Theory of Economic Development? Industry and Innovation 9(1/2):7–22

Witt U (2008) What is Specific about Evolutionary Economics? J Evol Econ 18:547–75

Woods EB (1920) Heredity and Opportunity. Am J Soc 26(1):1–21

Wright S (1931) Evolution in Mendelian Populations. Genetics 16:97–159

Download references

There is no source of funding to declare.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Loughborough University London, London, UK

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The named author is responsible for 100% of the content of this article.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Geoffrey M. Hodgson .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

There is no competing interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions