- Open access

- Published: 11 July 2018

How to engage stakeholders in research: design principles to support improvement

- Annette Boaz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0557-1294 1 ,

- Stephen Hanney 2 ,

- Robert Borst 3 ,

- Alison O’Shea 1 &

- Maarten Kok 4

Health Research Policy and Systems volume 16 , Article number: 60 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

110k Accesses

196 Citations

84 Altmetric

Metrics details

Closing the gap between research production and research use is a key challenge for the health research system. Stakeholder engagement is being increasingly promoted across the board by health research funding organisations, and indeed by many researchers themselves, as an important pathway to achieving impact. This opinion piece draws on a study of stakeholder engagement in research and a systematic literature search conducted as part of the study.

This paper provides a short conceptualisation of stakeholder engagement, followed by ‘design principles’ that we put forward based on a combination of existing literature and new empirical insights from our recently completed longitudinal study of stakeholder engagement. The design principles for stakeholder engagement are organised into three groups, namely organisational, values and practices. The organisational principles are to clarify the objectives of stakeholder engagement; embed stakeholder engagement in a framework or model of research use; identify the necessary resources for stakeholder engagement; put in place plans for organisational learning and rewarding of effective stakeholder engagement; and to recognise that some stakeholders have the potential to play a key role. The principles relating to values are to foster shared commitment to the values and objectives of stakeholder engagement in the project team; share understanding that stakeholder engagement is often about more than individuals; encourage individual stakeholders and their organisations to value engagement; recognise potential tension between productivity and inclusion; and to generate a shared commitment to sustained and continuous stakeholder engagement. Finally, in terms of practices, the principles suggest that it is important to plan stakeholder engagement activity as part of the research programme of work; build flexibility within the research process to accommodate engagement and the outcomes of engagement; consider how input from stakeholders can be gathered systematically to meet objectives; consider how input from stakeholders can be collated, analysed and used; and to recognise that identification and involvement of stakeholders is an iterative and ongoing process.

It is anticipated that the principles will be useful in planning stakeholder engagement activity within research programmes and in monitoring and evaluating stakeholder engagement. A next step will be to address the remaining gap in the stakeholder engagement literature concerned with how we assess the impact of stakeholder engagement on research use.

Peer Review reports

Closing the gap between research production and research use is a key challenge for the health research system. Stakeholder engagement is being increasingly promoted across the board by health research funding organisations, and indeed by many researchers themselves, as an important pathway to achieving impact [ 1 ]. The literature is diverse, with a rapidly expanding but still relatively small number of papers specifically referring to ‘stakeholder engagement’, and a larger number of publications discussing issues that at least partly overlap with stakeholder engagement. Several of the papers explicitly analysing stakeholder engagement come from the field of environmental research (e.g. Jolibert and Wesselink [ 2 ], Phillipson et al. [ 3 ]). However, stakeholder engagement is also gaining traction in the health field. A recent supplement in this journal consolidated learning relating to tools and approaches to stakeholder engagement within the United Kingdom Department for International Development’s Future Health Systems research consortium [ 4 ]. In particular, in health, there is an important stream of analysis from North America. A review for the United States Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality drew on papers from a range of fields [ 5 ].

This opinion piece provides a short conceptualisation of stakeholder engagement, followed by ‘design principles’ that we put forward based on a combination of existing literature and new empirical insights from our recently completed longitudinal study of stakeholder engagement in research. We have drawn on a systematic literature search conducted to inform the wider study and in particular to conceptualise stakeholder engagement (Additional file 1 ).

Literature review

Conceptualising stakeholder engagement: what does the literature say.

Stakeholders have been defined as “ individuals, organizations or communities that have a direct interest in the process and outcomes of a project, research or policy endeavor ” ([ 6 ], p. 5). In seeking to conceptualise stakeholders, Concannon et al. [ 7 ] developed the 7Ps Framework to identify stakeholders in Patient-Centered Outcomes Research and Comparative Effectiveness Research in the United States of America. The 7Ps are patients and the public, providers, purchasers, payers, public policy-makers and policy advocates working in the non-governmental sector, product makers, and principal investigators. The seven categories signal an overlap with the large literature on patient and public involvement (PPI) in research. However, our focus here is on multi-stakeholder engagement, where diverse groups of stakeholders take part in the research process. Deverka et al. [ 6 ] define engagement as “ an iterative process of actively soliciting the knowledge, experience, judgment and values of individuals selected to represent a broad range of direct interest in a particular issue, for the dual purposes of: creating a shared understanding; making relevant, transparent and effective decisions ” ([ 6 ], p. 5).

Roles, activities and phases of stakeholder engagement: What does the literature say?

There are additional issues about the definition of stakeholder engagement when the nature of the engagement activities is considered. For example, there are issues about how far co-creation/participatory action research approaches can be considered to be stakeholder engagement or something so far beyond the usual stakeholder engagement that they are really in a different category [ 8 ]. Similarly, there is a large and currently distinct literature on PPI in research [ 9 ], including the development of reporting guidelines such as GRIPP2 [ 10 ]. There are a number of parallels in the issues discussed in these literatures as well as some interesting differences (particularly in terms of power inequalities). However, herein, we conceptualise PPI as a subset of stakeholder engagement in-line with most of the literature, including Concannon et al. [ 7 ].

Most of the stakeholder engagement literature highlights the broad range of activities in which stakeholders can engage depending on their own skills and attributes and the capacity and wishes of the researchers conducting specific studies. At the broadest level of a research system, or research funding body, Lomas [ 11 ] claimed there were many activities in which stakeholders could be engaged in a ‘linkage and exchange’ approach for health services research. These were setting priorities, funding programmes, assessing applications, conducting research and communicating findings. The importance of engaging a wide range of stakeholders in priority-setting has often been emphasised. The pioneering study by Kogan and Henkel [ 12 ] analysed both the importance of engaging policy-makers in setting research agendas to meet their needs, and the obstacles to making the process work well. These obstacles included issues around how far the assessment of needs-based research should focus on the relevance and practical impact of the research as well as its scientific merit. Many of the more recent studies explicitly examining stakeholder engagement also set out a range of activities in which stakeholders may be involved. These are often related to phases of the research processes. Concannon et al. [ 7 ] provide a list of roles related to stages and used the identified roles in a subsequent review [ 13 ].

Knowledge translation (KT) is one of many terms used to describe efforts to ensure research evidence is used to inform decision-making [ 14 ]. Although the importance of engaging stakeholders in KT is recognised, it has been acknowledged that stakeholder engagement is often overlooked in favour of more conventional dissemination strategies [ 15 ]. Integrated KT has been developed as an approach to collaborative research in which researchers work with stakeholders who identify a problem and have the influence and sometimes authority to implement the knowledge generated through research [ 16 , 17 ]. Grimshaw et al. [ 14 ] argue that different groups of stakeholders are likely to be engaged depending on the type of research that is being translated.

Assessing the impact of stakeholder engagement: What does the literature say?

A final consideration about the nature of the body of literature specifically on stakeholder engagement is that not only is it still quite limited in total, but there are also notable areas where authors claim it is particularly sparse. In particular, Hinchcliff et al. [ 18 ] examined the literature on multi-stakeholder health services research collaborations in an attempt to address the question of whether it was worth investing in them. They identified very few studies (Harvey et al’s. [ 19 ] 2011 evaluation of a Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care being one exception) and concluded that their generalisability was questionable. They therefore suggested that “ The lack of reliable evidence compels implementers to rely largely on trial and error, risking variable success ” ([ 18 ], p. 124).

The nature of engagement activity is less contentious than the arguments about its potential impact. Research impacts on non-academic audiences are defined by the United Kingdom Higher Education Funding Council as: “ benefits to one or more areas of the economy, society, culture, public policy and services, health, production, environment, international development or quality of life, whether locally, regionally, nationally or internationally ” [ 20 ]. Various studies have attempted to assess a range of impacts of research (especially health research) and/or attempted to identify facilitators and barriers of research use in policy-making. There are also a growing number of reviews of such studies [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ]. While these are not explicitly studies of stakeholder engagement, many of them have identified some form of collaboration between researchers and users as one of the factors most likely to lead to the research making an impact. However, this wider range of literature does not go into detail in terms of analysing the nature of the processes of stakeholder engagement that leads to impact.

Studies specifically focusing on the impact of stakeholder engagement are less common, although it is a growing area of interest [ 28 , 29 ]. Jolibert and Wesselink [ 2 ] found a few examples of impact, but suggested ways to increase impact through what they describe as sustained interactions. Concannon et al. concluded that approximately 20% of their study participants “ reported that stakeholder engagement improved the relevance of research, increased stakeholder trust... enhanced mutual learning by stakeholders, and researchers about each other, or improved research adoption ” ([ 13 ], p. 1697), whereas 6% reported improved transparency and 9% increased understanding of research processes. Also, while Forsythe et al. referred to a lack of evidence about impact, they also observed that “ Commonly reported contributions included changes to project methods, outcomes or goals; improvement of measurement tools; and interpretation of qualitative data ” ([ 30 ], p. 13). In the United States, the Center for Medical Technology Policy website makes a strong statement about the impact of stakeholder engagement: “ Including the perspectives of all key stakeholders has powerful benefits, enhancing both the short- and long-term relevance of clinical research efforts ” [ 31 ].

Assessing the impact of stakeholder engagement: a new study

Given the diversity of stakeholder engagement and the thin evidence base for its impact, our study set out to identify a set of indicators that might be used to identify stakeholder engagement with potential for impact. We identified a study called the European study on Quantifying Utility of Investment in Protection from Tobacco (EQUIPT) and then conducted our own study, Stakeholder Engagement in EQUIPT (SEE-Impact) as a prospective study of stakeholder engagement running alongside. EQUIPT, a major European Commission (EC) – funded project, aimed to achieve impact through extensive stakeholder engagement. Both studies are briefly described in Box 1.

The results of the EQUIPT study have now been published [ 32 , 33 ] and a full account of the main methods from SEE-Impact have been submitted for publication. Papers on the full findings are being finalised. Herein, our aim is to address the statement in our original funding proposal in 2013 that it should be possible to identify aspects of the stakeholder engagement (and perhaps other features of the processes) that might be viewed as intermediate indicators of the eventual impact achieved.

Our analysis of the complex and nuanced process of stakeholder engagement has resulted not in a list of indicators, but in a set of design principles. We hope that these design principles will help to inform the future development of stakeholder engagement as a mechanism for promoting research impact. These principles, rooted in both the existing literature and in the findings from our prospective study of stakeholder engagement, are intended to inform the planning and delivery of stakeholder engagement activities. It is anticipated that they will also provide a structure for building a narrative account of stakeholder engagement as part of an evaluation of an individual project or programme. They might also provide a starting point for the development of future indicators.

Design principles for stakeholder engagement in research

The project team (comprising members of the SEE-Impact research team and collaborators from EQUIPT) met for a 2 day analysis workshop. One aim of the workshop was to begin to build a consensus among the team on what seemed to be the key design principles emerging from the SEE-Impact data and the on-going literature review. SEE-Impact data included observational data, interviews and document analysis. The research team continued to develop the principles through an ongoing period of deliberation, informed by the impact study and the literature. As part of this process, the principles were categorised into three groups, namely organisational, values and practices.

In this section, we first present empirical evidence from the SEE-Impact study that informed our development of the design principles. We then briefly summarise published evidence for each group of design principles in order to situate them in the wider literature.

Design principles and empirical evidence from the stakeholder engagement in EQUIPT for impact (SEE-impact) study

The stakeholder engagement study (SEE-Impact) and the project being studied (EQUIPT) are described in Box 1. In terms of the organisational level principles, the EQUIPT project objectives for stakeholder engagement were clear, as set out in the proposal, protocol and project documents [ 34 ]. The key aims of stakeholder engagement activity were to access the knowledge and skills (described in the protocol as co-creation innovation in the working space) and to increase influence and impact (described in the protocol as dissemination innovation in the transfer space through stakeholder engagement).

In terms of values, the commitment to stakeholder engagement was more clearly demonstrated by some of the EQUIPT project team members than others. For some team members, previous successful experience of an interactive form of working with stakeholders had built a commitment to this particular way of working. It also provided experience of practical elements of working with stakeholders, but perhaps most importantly lived experience of the practical benefits of engagement. For other members of the team, too, working with stakeholders fitted closely with their ethos and values. For example, the Hungarian team talked about their pragmatic approach to research and the need to conduct useful and usable research, with stakeholder engagement being a key component. However, a small group within the wider project team did not seem committed to ensuring stakeholder engagement remained a core element of the project. They favoured a particular, individualised approach to stakeholders and, over time, partially reshaped the stakeholder engagement activities to something more akin to research participation (that is, taking part in a research study as a means of generating specific data as determined by researchers, rather than as co-producers of research). Finally, not all stakeholders identified by the project team were interested in engaging with the project. In particular, the lack of policy priority given to smoking cessation (the focus of the return on investment (ROI) tool) made engagement of policy stakeholders in the Netherlands very difficult to achieve.

In terms of practices, while the EQUIPT project protocol did set out how the stakeholder engagement would operate [ 34 ], there was not as much flexibility as the investigators would have liked in terms of the project plan and this had an impact on the nature of the stakeholder engagement activities. In particular, time intensive methods of engagement originally proposed in the protocol (particularly the large number of face-to-face meetings) began to look unrealistic to members of the team. The lack of flexibility came in part from the funder. The EC told the project team at an early point that there was no scope for negotiation around the project end date. Thus, initial delays in the project put a strain on the project timetable and deliverables. Members of the team proposed a shift from face-to-face meetings with stakeholders to Skype meetings in an effort to ‘catch up’. The technical team producing the new version of the ROI tool for roll out in Europe added to a sense of urgency in ‘speeding up’ the stakeholder engagement work with their need for data to feed into their work. Nevertheless, despite the practical difficulties, in EQUIPT, a significant amount of consideration had been given to stakeholder engagement, including planning how the input provided by stakeholders might be gathered, collated, analysed and used. Vokó et al. highlight that it is important to “ fully analyse several aspects of stakeholder engagement in research ” ([ 32 ], p. 15) and note that there is a tendency to ignore the value of early stakeholder engagement when it comes to development and transferability in the work of economic evaluation. EQUIPT’s careful consideration and the methods adopted facilitated a much more rigorous approach to stakeholder engagement than is often experienced.

Design principles and supporting literature

The design principles for stakeholder engagement are organised into three groups, namely organisational, values and practices, albeit with some inevitable overlaps. We look at each category in turn, alongside a consideration of some of the relevant literature.

Organisational

Clarify the objectives of stakeholder engagement

Embed stakeholder engagement in a framework or model of research use

Identify the necessary resources for stakeholder engagement

Put in place plans for organisational learning and rewarding of effective stakeholder engagement

Recognise that some stakeholders have the potential to play a key role

Some examples from the literature

It is desirable to have a conceptual framework that situates stakeholder engagement as part of a plan for promoting research use in practice. Deverka et al. [ 6 ] proposed an ‘analytic-deliberative’ conceptual model for stakeholder engagement which “ illustrates the inputs, methods and outputs relevant to CER [comparative effectiveness research]. The model differentiates methods at each stage of the project; depicts the relationship between components; and identifies outcome measures for evaluation of the process ” ([ 6 ], p. 1). Furthermore, having a clear evaluation plan is considered critical. Concannon et al. recommended conducting “ evaluative research on the impact of stakeholder engagement on the relevance, transparency and adoption of research ” ([ 13 ], p. 1698). Esmail et al. argue that evaluations of stakeholder engagement should be “ designed a priori as an embedded component of the research process ” ([ 35 ], p. 142). They suggest that, where possible, evaluations should use predefined, validated tools. Jolibert and Wesselink [ 2 ] point out that linking stakeholders’ contributions with specific research objectives is important in order to establish when and how to engage and with whom. They argue that, at the recruitment stage, stakeholders should be made aware of, for example, their role/s, what they could contribute, costs in terms of time and effort, and benefits. Concannon et al. also conclude that funding is needed “ to account for the costs of implementing meaningful engagement activities ” ([ 7 ], p. 989).

In a Canadian study looking at stakeholder involvement in KT as a means of leading to more evidence-informed healthcare, Holmes et al. [ 36 ] identify a range of complexities which, they argue, need to be taken into account by funding schemes in order to meet funders’ and stakeholders’ expected ROI. Stakeholder involvement in research and implementing its findings is complex and time consuming, and the authors recommend an advocacy role where funders support a range of activities to address barriers to effective KT. These include carrying out an assessment of stakeholders’ KT needs “ to identify gaps and opportunities and avoid duplication of efforts ” ([ 36 ], p. 6). Kramer et al. [ 37 ] looked at the involvement of intermediary organisations as research partners on three interventions across four sectors, namely manufacturing, transportation, service and electrical utilities sectors. The authors describe the difficulties, benefits and challenges from the perspectives of both researchers and research partners and stress the importance of allowing the design of the protocol to be collaborative and flexible. Researchers need to honour, trust and respect their partners’ knowledge and expertise, and take into account their needs and priorities. Failure to meet these criteria will significantly dampen stakeholders’ enthusiasm. They also point out the importance of having a model of collaborative research with clear guidelines of how to conduct partnership research projects in order to further facilitate the use of research by practitioners. There would be an invested interest in “ the research question, design and findings, and this would prove to be very valuable as a knowledge transfer strategy ” ([ 37 ], p. 330).

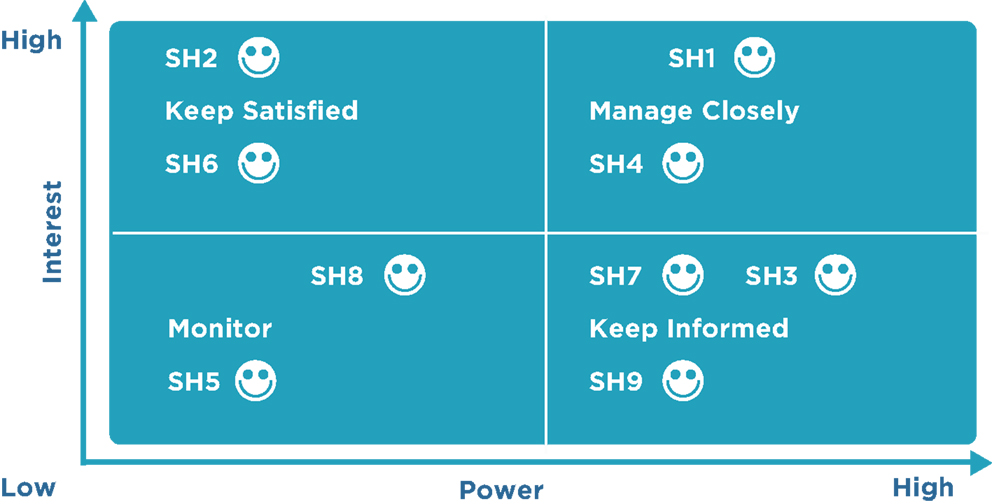

The main literature on stakeholder analysis of policy-making is also useful for highlighting that some stakeholders have more potential to play a key role in the policy deliberations than others. For example, as part of their review of stakeholder analysis of health policy-making, Brugha and Varvasovszky [ 38 ] described an example in which the Hungarian Ministries of Finance and Industry were non-mobilised, high-influence, low-interest stakeholders in debates about public health interventions, but might, in some circumstances, become mobilised high-interest actors.

Foster shared commitment to the values and objectives of stakeholder engagement in the project team

Share understanding that stakeholder engagement is often about more than individuals

Encourage individual stakeholders and their organisations to value engagement

Recognise potential tension between productivity and inclusion

Generate a shared commitment to sustained and continuous stakeholder engagement

Concannon et al. [ 7 ] stress that researchers and stakeholders should be committed to the processes from the outset. Hinchcliff et al. [ 18 ] argue that it is important to define expectations and roles and provide time. Hering et al.’s [ 39 ] global study of water science and technology used stakeholder involvement in the objectives and approaches of the research for the co-production of knowledge as part of transdisciplinary research. Key aspects of particular value to the research included early identification and involvement of stakeholders, continuous engagement with stakeholders, and availability to stakeholders of supporting materials and in multiple languages. Mallery et al. recommend continuing to build trust with stakeholders “ throughout the engagement process ” ([ 5 ], p. 27).

Plan stakeholder engagement activity as part of the research programme of work

Build flexibility within the research process to accommodate engagement and the outcomes of engagement

Consider how input from stakeholders can be gathered systematically to meet objectives

Consider how input from stakeholders can be collated, analysed and used

Recognise identification and involvement of stakeholders is an iterative and ongoing process

Forsythe et al. [ 30 ] highlight the importance of careful and strategic selection of stakeholders. As part of evidence and experience-based guidance to researchers and practice personnel about forming and carrying out effective research partnerships, Ovretveit et al. [ 40 ] developed a guide to categorise and describe types of partnerships or approaches to collaborative working. The guide sets out a framework for the roles and tasks, and the allocation of responsibilities for each partner involved. Roles and tasks are assigned to three main categories, namely questions, design and data, reporting and dissemination, and implementation and integration into organisation or policy. Concannon et al. [ 13 ] suggest the need to develop (and validate) stakeholder engagement tools to support engagement work. Forsythe et al. also stress the importance of “ establishing ‘parameters and expectations for roles’, giving stakeholders guidance, and allowing time for stakeholders to ‘get comfortable with their roles’ as important tasks ” ([ 30 ], p. 19).

The review of methods of stakeholder engagement conducted by Mallery et al. [ 5 ] identified a range of innovative methods and stressed the potential for engaging stakeholders at different points in the research process. The five methods highlighted for consideration were online collaborative forums, product development challenge contests, online communities, grassroots community organising and collaborative research. Jolibert and Wesselink [ 2 ] explored levels and types of stakeholder engagement in 38 EC-funded biodiversity research projects and the impacts of collaborative research on policy, society and science. They looked at how and when stakeholders were involved and the roles played, and argue that greater engagement throughout the whole of the research process, rather than, for example, at the dissemination stage, tends to lead to improved assessment of environmental change and effective policy proposals. Jolibert and Wesselink suggest, following Huberman’s [ 41 ] work in education, that it is desirable to have ‘sustained interactivity’ between researchers and users. Concannon et al. suggest that “ General principles can be drawn from community-based participatory research, which underscores that engagement is a relationship-building process ” ([ 7 ], p. 988). They found that, if bi-directional relationships are sustained over time, stakeholders can serve as ambassadors for high-integrity evidence even where the findings are contrary to generally accepted beliefs. Hinchcliff et al. point to the importance of “ building respect and trust through ongoing interaction ” ([ 18 ], p. 125). Forsythe et al. flag up the importance of continuous involvement and using in-person contact to build relationships [ 30 ]. They also stress the value in having a flexible approach that can adapt to the practical needs of stakeholders. A recent supplement of this journal edited by Paina et al. [ 4 ] also highlighted the importance of flexibility in making space for stakeholder engagement in research processes.

Based on the literature and the application of initial principles to our study, we have developed the elaborated design principles presented in Box 2.

Conclusions

There is a growing interest in stakeholder engagement as a potentially promising approach to promoting research impact. There is also a developing literature mapping out who potential stakeholders might be (the ‘who’), considering approaches to stakeholder engagement (the ‘how’) and identifying rationales for stakeholder engagement (the ‘why’). In this paper, evidence from the literature around these dimensions has been combined with the findings from our study of stakeholder engagement in an EC-funded project to develop a set of design principles to inform future stakeholder engagement in research. The design principles encompass organisational factors, values and practices. We hope that the principles will be useful in planning stakeholder engagement activity within research programmes and in monitoring and evaluating stakeholder engagement. Active engagement of stakeholders may well shift our understanding of what research use looks like [ 39 ]. A next step will be to address the remaining gap in the stakeholder engagement literature concerned with how we assess the impact of stakeholder engagement on research use.

Box 1: Studying stakeholder engagement in tobacco control policy

EQUIPT: the European-study on Quantifying Utility of Investment in Protection from Tobacco

The EQUIPT study set out to work with stakeholders to develop a tool to help government officials, policy-makers and healthcare providers across Europe examine the cost effectiveness and impact of anti-smoking initiatives. The tool was developed as part of a €2 million European Commission grant. An earlier version had already been piloted with local authorities around the United Kingdom, with users able to draw on specific circumstances, statistics and data to predict the impact of tobacco control in their particular regions. The successful stakeholder engagement in the United Kingdom work encouraged the research team to fully integrate stakeholder engagement into the European study. In this study, the following stakeholders were identified: National and European stakeholders consisting of policy-makers, academics, health authorities, insurance companies, advocacy groups, ministries of finance, national committees, clinicians and health technology assessment (HTA) professionals, and experts on smoking cessation and HTA. Ninety three stakeholders took part. They were engaged in a variety of ways, including through one-to-one interviews, Skype meetings and events. Much of the engagement activity focused on the development of the return of investment tool for application in different countries.

SEE-Impact: Stakeholder Engagement in EQUIPT for Impact

SEE-IMPACT was a 3-year prospective study awarded £157,000 from the United Kingdom’s Medical Research Council funding as part of their joint Methodology Programme with the National Institute for Health Research, earmarked to boost understanding of the impact of health-related studies on society and the economy. The study compared and contrasted the way the EQUIPT decision support tool was taken up in a further four European countries – Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands and Spain. The SEE-Impact study focused in particular on the ways in which stakeholders were engaged throughout the EQUIPT study. The study used a range of methods including interviews, surveys, observations and reviews of documents to develop a detailed understanding of how stakeholder engagement might work as a mechanism for promoting impact. An initial literature review on stakeholder engagement was used to distil a set of propositions for testing. Further details about the project can be found on the website of the MRC (now under United Kingdom Research and Innovation).

Box 2 Design principles for stakeholder engagement

1) Clarify the objectives of stakeholder engagement

The objectives might be one or more of accessing knowledge and skills; supporting interpretation of the results and drafting recommendations; supporting future influence and impact on policy and practice; increasing recruitment/enabling research; supporting transferability. The objectives need to be shared then among all parties.

2) Embed stakeholder engagement in a framework or model of research use

There are a number of models and frameworks designed to show how stakeholders might be engaged in a way that helps increase the chances of research being used in policy and practice, for example, the linkage and exchange model [ 9 ]

3) Identify the necessary resources for stakeholder engagement

Resources to consider are budget, time, skills and competences to manage engagement

4) Put in place plans for organisational learning and rewarding of effective stakeholder engagement, for example, through appropriate evaluation of stakeholder engagement

5) Recognise that some stakeholders have the potential to play a key role

Identify those stakeholders who are particularly interested in being engaged and those who are likely to be influential. Depending on the objective of stakeholder engagement, they may provide the most useful input, and are most likely to play a key role in using the results; their engagement should be especially encouraged

6) Foster shared commitment to the values and objectives of stakeholder engagement in the project team

Ideally, make sure the commitment is there from the outset [ 6 ]

7) Share understanding that stakeholder engagement is often about more than individuals

Consideration needs to be given to stakeholders’ roles where they act as representatives – their power and influence within organisations and networks they represent and how these change over time

8) Encourage individual stakeholders and their organisations to value engagement

Support and build capacity for stakeholders and their organisations to engage

9) Recognise potential tension between productivity and inclusion

Engagement may lead to greater relevance and impact, but may have implications for productivity in meeting project objectives (for example, in a timely fashion). Engaging stakeholders, taking into account their needs and inputs and adjusting elements of the research project based on their feedback takes time and can slow down the research process

10) Generate a shared commitment to sustained and continuous stakeholder engagement

Project teams and stakeholders see the value of links between research producers and research users to build ongoing collaborations in order to meet the objectives

11) Plan stakeholder engagement activity as part of the research programme of work

This should be built into the project protocol or plan (see Pokhrel et al. [ 34 ])

12) Build flexibility within the research process to accommodate engagement and the outcomes of engagement

It will also be important to build in mechanisms to allow researchers to have the independence to articulate what is out of scope

13) Consider how input from stakeholders can be gathered systematically to meet objectives

The importance of some face-to-face contact and interactions should be considered

14) Consider how input from stakeholders can be collated, analysed and used

This important aspect of stakeholder engagement needs to be considered earlier than often happens

15) Recognising identification and involvement of stakeholders is an iterative and ongoing process

Ongoing interaction will be fostered by taking the time and creating the structures to build trustful relationships ([ 6 , 12 ])

Abbreviations

European Commission

European-study on Quantifying Utility of Investment in Protection from Tobacco

Knowledge translation

Patient and public involvement

Return on investment

Stakeholder Engagement in EQUIPT for Impact

Kok M, Gyapong J, Wolffers I, Ofori-Adjei D, Ruitenberg J. Which health research gets used and why? An empirical analysis of 30 cases. Health Res Policy Syst. 2016;14:36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-016-0107-2 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Jolibert C, Wesselink A. Research impacts and impact on research in biodiversity conservation: The influence of stakeholder engagement. Environ Sci Policy. 2012;20:100–11.

Article Google Scholar

Phillipson J, Lowe P, Proctor A, Ruto E. Stakeholder engagement and knowledge exchange in environmental research. J Environ Manag. 2012;95:56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.10.005 .

Paina L, Ekirapa-Kiracho E, Ghaffar A, Bennett S. Engaging stakeholders in implementation research: tools, approaches, and lessons learned from application. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15(Suppl 2):104.

Google Scholar

Mallery C, Ganachari D, Fernandez J, Smeeding L, Robinson S, Moon M, Lavallee D, Siegel J. Innovative Methods in Stakeholder Engagement: An Environmental Scan. Prepared by the American Institutes for Research under contract No. HHSA 290 2010 0005 C. AHRQ Publication NO. 12-EHC097-EF. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012.

Deverka PA, Lavallee DC, Desai PJ, Esmail LC, Ramsey SD, Veenstra DL, et al. Stakeholder participation in comparative effectiveness research: defining a framework for effective engagement. J Comp Eff Res. 2012;1(2):181–94.

Concannon TW, Meissner P, Grunbaum JA, McElwee N, Guise JM, Santa J, Conway PH, Daudelin D, Morrato EH, Leslie LK. A new taxonomy for stakeholder engagement in patient centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:985–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2037-1 .

Greenhalgh T, Jackson C, Shaw S, Janaiman T. Achieving research impact through cocreation in community-based health services: literature review and case study. Milbank Q. 2016;94(2):392–429.

Boaz A, McKevitt C, Biri D. Rethinking the relationship between science and society: has there been a shift in attitudes to patient and public involvement and public engagement in science in the United Kingdom? Health Expect. 2016;19(3):592–601. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12295 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, Seers K, Mockford C, Goodlad S, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ. 2017;358:j3453.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Lomas J. Using ‘linkage and exchange’ to move research into policy at a Canadian foundation. Health Aff. 2000;19(3):236–40. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.19.3.236 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kogan M, Henkel M. Government and Research: The Rothschild Experiment in a Government Department. London: Heinemann Educational Books; 1983. (2nd edition. Dortrecht: Springer; 2006).

Concannon TW, Fuster M, Saunders T, Patel K, Wong JB, Leslie LK, Lau J. A systematic review of stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness and patient-centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1692–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2878-x .

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7:50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-50 .

Bowen S, Graham ID. Integrated knowledge translation. In: Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham ID, editors. Knowledge Translation in Health Care: Moving from Evidence to Practice. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118413555.ch02 .

Chapter Google Scholar

McCutcheon C, Graham ID, Kothari A. Defining integrated knowledge translation and moving forward: a response to recent commentaries. Int J Health Policy Manage. 2017;6(5):299–300.

Gagliardi AR, Berta W, Kothari A, Boyko J, Urquhart R. Integrated knowledge translation (IKT) in health care: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2016;11:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0399-1 .

Hinchcliff R, Greenfield D, Braithwaite J. Is it worth engaging in multi-stakeholder health services research collaborations? Reflections on key benefits, challenges and enabling mechanisms. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26:124–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzu009 .

Harvey G, Fitzgerald L, Fielden S, McBride A, Waterman H, Bamford D, Kislov R, Boaden R. The NIHR collaboration for leadership in applied health research and care (CLAHRC) for greater Manchester: combining empirical, theoretical and experiential evidence to design and evaluate a large-scale implementation strategy. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):96. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-96.

Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE). 2014 REF: Assessment Framework and Guidance on Submissions. Panel A Criteria. London: HEFCE; 2012.

Innvær S, Vist G, Trommald M, Oxman A. Health policy-makers’ perceptions of their use of evidence: a systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7:239–44. https://doi.org/10.1258/135581902320432778 .

Hanney SR, Gonzalez-Block MA, Buxton MJ, Kogan M. The utilisation of health research in policy-making: concepts, examples and methods of assessment. Health Res Policy Syst. 2003;1:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-1-2 .

Lavis J, Davies H, Oxman A, Denis JL, Golden-Biddle K, Ferlie E. Towards systematic reviews that inform health care management and policymaking. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10 Suppl 1:35–48. https://doi.org/10.1258/1355819054308549 .

Boaz A, Fitzpatrick S, Shaw B. Assessing the impact of research on policy: a literature review. Sci Public Policy. 2009;36:255–70. https://doi.org/10.3152/030234209X436545 .

Banzi R, Moja L, Pistotti V, Facchini A, Liberati A. Conceptual frameworks and empirical approaches used to assess the impact of health research: an overview of reviews. Health Res Policy Syst. 2011;9:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-9-26 .

Oliver K, Innvar S, Lorenc T, Woodman J, Thomas J. A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-2 .

Hanney S, Greenhalgh T, Blatch-Jones A, Glover M, Raftery J. The impact on healthcare, policy and practice from 36 multi-project research programmes: findings from two reviews. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-017-0191-y .

Nyström ME, Karltun J, Keller C, Andersson Gäre B. Collaborative and partnership research for improvement of health and social services: researcher’s experiences from 20 projects. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0322-0.

Pollock A, Campbell P, Struthers C, Synnot A, Nunn J, Hill S, Goodare H, Watts C, Morley R. Stakeholder involvement in systematic reviews: a protocol for a systematic review of methods, outcomes and effects. Res Involv Engage. 2017;3:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-017-0060-4 .

Forsythe LP, Ellis LE, Edmundson L, Sabharwal R, Rein A, Konopka K, Frank L. Patient and stakeholder engagement in the PCORI pilot projects: description and lessons learned. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:13–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3450-z .

Center for Medical Technology Policy. Stakeholder Engagement. http://www.cmtpnet.org/our-work/stakeholder-engagement/ . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Vokó Z, Cheung KL, Józwiak-Hagymásy J, Wolfenstetter S, Jones T, Muñoz C, Evers S, Hiligsmann M, de Vries H, Pokhrel S. On behalf of the EQUIPT study. Similarities and differences between stakeholders’ opinions on using health technology assessment (HTA) information across five European countries: results from the EQUIPT survey group. Health Res Policy Syst. 2016;14:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-016-0110-7.

Evers SMAA, Hiligsmann M, Vokó Z, Pokhrel S, Jones T, et al. Understanding the stakeholders’ intention to use economic decision-support tools: a cross-sectional study with the tobacco return on investment tool. Health Policy. 2016;120(1):46–54.

Pokhrel S, Evers S, Leidl R, Trapero-Bertran M, Kalo Z, De Vries H, et al. EQUIPT: protocol of a comparative effectiveness research study evaluating cross-context transferability of economic evidence on tobacco control. BMJ Open. 2014;4(11) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-%20006945 .

Esmail L, Moore E, Rein A. Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: moving from theory to practice. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4(2):133–45. https://doi.org/10.2217/cer.14.79 .

Holmes B, Scarrow G, Schellenberger M. Translating evidence into practice: the role of health researcher funders. Implement Sci. 2012;7:39.

Kramer D, Wells R, Bigelow P, Carlan N, Cole D, Hepburn CG. Dancing the two-step: collaborating with intermediary organizations as research partners to help implement workplace health and safety interventions. Work. 2010;36(3):321–32. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2010-1033 .

Brugha R, Varvasovszky Z. Stakeholder analysis: a review. Health Policy Plan. 2000;15:239–46.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Hering J, Hoffmann S, Meierhofer R, Schmid M, Peter A. Assessing the societal benefits of applied research and expert Consulting in Water Science and Technology. Gaia. 2012;21(2):95–101. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.21.2.6 .

Ovretveit J, Hempel S, Magnabosco JL, Mittman BS, Rubenstein LV, Ganz DA. Guidance for research-practice partnerships (R-PPs) and collaborative research. J Health Organ Manage. 2014;28(1):115–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-08-2013-0164 .

Huberman M. Research utilization: the state of the art. Knowl Policy. 1994;7(4):13–33.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the EQUIPT team, in particular, the Principal Investigator Subhash Pokhrel.

The SEE-Impact study (Stakeholder Engagement in EQUIPT for Impact), received funding from the United Kingdom Medical Research Council to explore the engagement of stakeholders in the EQUIPT project.

The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Health, Social Care and Education, a partnership between Kingston University and St George’s, University of London, London, United Kingdom

Annette Boaz & Alison O’Shea

Health Economics Research Group, Brunel University London, Uxbridge, United Kingdom

Stephen Hanney

Erasmus School of Health Policy & Management, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Robert Borst

VU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Maarten Kok

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AB and SH conceived of the study. All authors contributed to the design, data collection and analysis. An initial draft of the paper was produced by AB, with all authors contributing significantly to its development and revision. The final version has been approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Annette Boaz .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical approval for the study entitled ‘Stakeholder Engagement in EQUIPT for Impact (SEE-IMPACT)’ was gained from the Research Ethics Committee, the Faculty of Health, Social Care and Education, St George’s University of London and Kingston University, on 18th March 2014.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:.

SEE-Impact study literature search. (DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Boaz, A., Hanney, S., Borst, R. et al. How to engage stakeholders in research: design principles to support improvement. Health Res Policy Sys 16 , 60 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0337-6

Download citation

Received : 28 February 2018

Accepted : 06 June 2018

Published : 11 July 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0337-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Stakeholder Engagement

- Build Flexibility

- Value Engagement

- Health Systems Research

- Shared Commitment

Health Research Policy and Systems

ISSN: 1478-4505

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Stakeholder theory and management: Understanding longitudinal collaboration networks

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Management Studies, Adnan Kassar School of Business, Lebanese American University, Beirut, Lebanon

Roles Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation School of Project Management, Faculty of Engineering, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation School of Engineering and IT, University of New South Wales (UNSW), Canberra, Australia

- Julian Fares,

- Kon Shing Kenneth Chung,

- Alireza Abbasi

- Published: October 14, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255658

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

This paper explores the evolution of research collaboration networks in the ‘stakeholder theory and management’ (STM) discipline and identifies the longitudinal effect of co-authorship networks on research performance, i.e., research productivity and citation counts. Research articles totaling 6,127 records from 1989 to 2020 were harvested from the Web of Science Database and transformed into bibliometric data using Bibexcel, followed by applying social network analysis to compare and analyze scientific collaboration networks at the author, institution and country levels. This work maps the structure of these networks across three consecutive sub-periods ( t 1 : 1989–1999; t 2 : 2000–2010; t 3 : 2011–2020) and explores the association between authors’ social network properties and their research performance. The results show that authors collaboration network was fragmented all through the periods, however, with an increase in the number and size of cliques. Similar results were observed in the institutional collaboration network but with less fragmentation between institutions reflected by the increase in network density as time passed. The international collaboration had evolved from an uncondensed, fragmented and highly centralized network, to a highly dense and less fragmented network in t 3 . Moreover, a positive association was reported between authors’ research performance and centrality and structural hole measures in t 3 as opposed to ego-density, constraint and tie strength in t 1 . The findings can be used by policy makers to improve collaboration and develop research programs that can enhance several scientific fields. Central authors identified in the networks are better positioned to receive government funding, maximize research outputs and improve research community reputation. Viewed from a network’s perspective, scientists can understand how collaborative relationships influence research performance and consider where to invest their decision and choices.

Citation: Fares J, Chung KSK, Abbasi A (2021) Stakeholder theory and management: Understanding longitudinal collaboration networks. PLoS ONE 16(10): e0255658. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255658

Editor: Ghaffar Ali, Shenzhen University, CHINA

Received: November 24, 2020; Accepted: July 21, 2021; Published: October 14, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Fares et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The emergence of research collaboration networks has largely contributed to the development of many scientific fields and the exponential increase in research publications [ 1 ]. Scientific collaboration is described as the interaction occurring between two or more entities (e.g. authors, institutions, countries) to advance a field of knowledge by uncovering scientific findings in more efficient ways that might not be possible through individual efforts [ 2 , 3 ]. Collaborative relationships affect research performance by disseminating the flow of knowledge, improving research capacity, enhancing innovation, creating new knowledge sources, reducing research cost through economies of scope, and creating synergies between multi-disciplinary teams [ 2 , 4 – 7 ]. Therefore, understanding the status quo of a scientific discipline requires understanding the social structure and composition of these collaborative relationships [ 1 , 8 , 9 ].

Social network analysis (SNA) is one of the most utilized methods for exploring scientific collaboration networks. SNA can quantify, analyze and visualize relationships in a specific research community, identify central opinion leaders that are leading collaborative works as well as evaluate the underlying structures that are influencing collaboration. Usually in a scientific collaboration network, the authors, institutions, and countries are referred to as “actors” or “nodes” and the collaborative relationships between them as “ties”. Indeed, there are a plethora of studies that used SNA to examine scientific collaboration networks of co-authors in various disciplines [ 2 , 10 – 18 ]. However, the findings of the above studies remain inconclusive regarding the longitudinal associations between structures of co-authorship networks and research performance across different sub-periods [ 18 – 20 ], and particularly in the “stakeholder theory and management” (STM) field, there is paucity of evidence. The value of the STM discipline in scientometrics and scientific collaboration research lies in its cross-disciplinary nature, i.e., having been applied in various business [ 21 , 22 ] and non-business domains [ 23 – 25 ], interconnecting different scientific disciplines that were once considered dispersed. The stakeholder theory is considered by many as a “living Wiki”- that is continuously growing through the collaboration of various scholars from different research fields. In light of the above argument, the aims of this study are to:

- explore the evolution of research collaboration networks of each of the authors, institutions, and countries in the STM discipline and across three consecutive sub-periods ( t 1 : 1989–1999; t 2 : 2000–2010; t 3 : 2011–2020),

- identify the key actors (authors, institutions, and countries) that are leading collaborative works in each sub-period, and

- understand the longitudinal effect of co-authorship networks on research performance measured by research productivity (i.e. the number of published papers) and citation counts of the entities [ 26 ].

Certainly, scholars can collaborate in a multitude of different ways ranging from faculty-based administrative works, conference participations, meetings, seminars, inter-institutional joint projects and informal relationships [ 27 ]. However, this study uses co-authorship analysis–as a widely used and reliable bibliometric method that explores co-authorship relationship on scientific papers between different actors (nodes) being authors, institutions or countries. Therefore, the analysis in this paper is carried out at three level: the micro level–authors of the same or different institutions; the meso level–inter-institutional strategic alliances (universities and departments); and the macro level–international partnerships entailing the authors and institutions, all of which are major spectrums of research collaboration [ 7 , 28 ].

To do so, the web of science (WoS) database is used to extract the bibliometric data of 6127 journal articles published in the last 32 years (1989–2020). This data was analyzed using Bibexcel as a package program for bibliometric analysis, UCINET for further SNA, and VOSviewer for visualizing the networks. The results provide important insights for allocating governmental funding, maximizing research output, improving research community reputation and enhancing cost savings that all should be directly or indirectly piloted by the most suitable scientists that can influence and lead collaborative research in their networks [ 29 , 30 ].

This paper starts with a brief history of STM research, followed by an overview of network theories most relevant to this study. Then, the methodology for data collection, refinement and analysis is described. Descriptive and SNA results are presented for each of the examined networks across the three sub-periods, followed by the findings of the association testing between different social network measures (ego-density, degree centrality, betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, efficiency, constraint and average tie strength) and each of the citation counts and research productivity metrics. Lastly, the conclusions and the theoretical and practical implications are provided.

Literature review

Origins of stm.

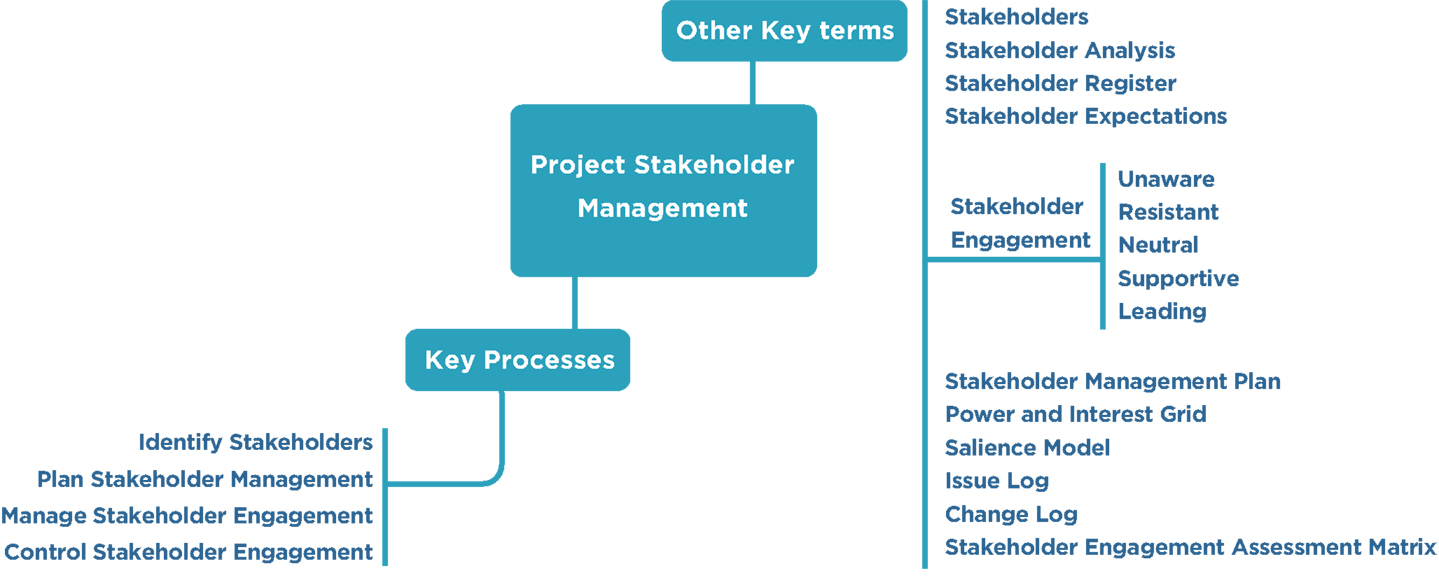

The stakeholder concept was first originated in the Stanford Research Institute in the 1960s, and then more formally introduced by Freeman [ 31 ] as a new theory of strategic management that aims to create value for various organizational groups and individuals to achieve business success. The stakeholder theory aims to define and create value, interconnect capitalism with ethics and identify appropriate management practices [ 32 ]. A stakeholder is best defined as “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives” [ 31 ]. Freeman emphasized on the relationships between the organization and its stakeholders as the central unit of analysis and a point of departure for stakeholder research. Accordingly, Rowley [ 33 ] was the first to introduce social networks to STM to understand the mechanism of such relationships. In particular, he argued that a focal firm’s response to stakeholder pressure is based on the interplay between the centrality of the focal firm and the density of stakeholder alliances. There have been many seminal works that put stakeholder theory on a solid managerial science footing, such that of Donaldson and Preston’s [ 34 ] that conceptualized the theory from a descriptive, instrumental and normative approach, followed by Mitchell et al. [ 35 ] who proposed a framework for identifying stakeholder salience using the attributes of power, legitimacy and urgency, and so on [ 36 – 39 ].

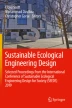

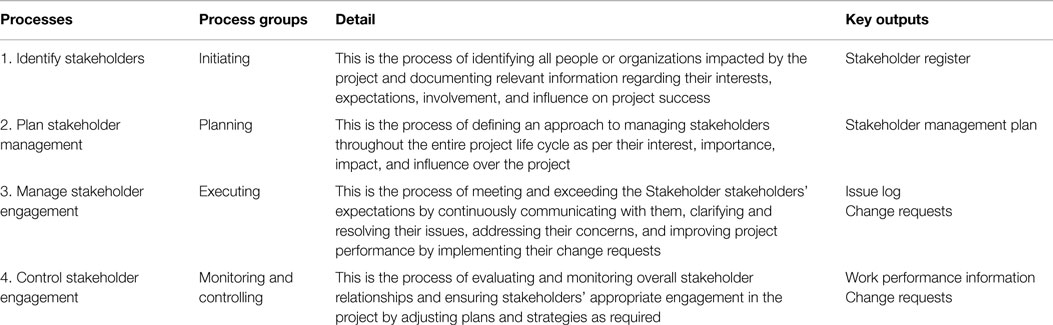

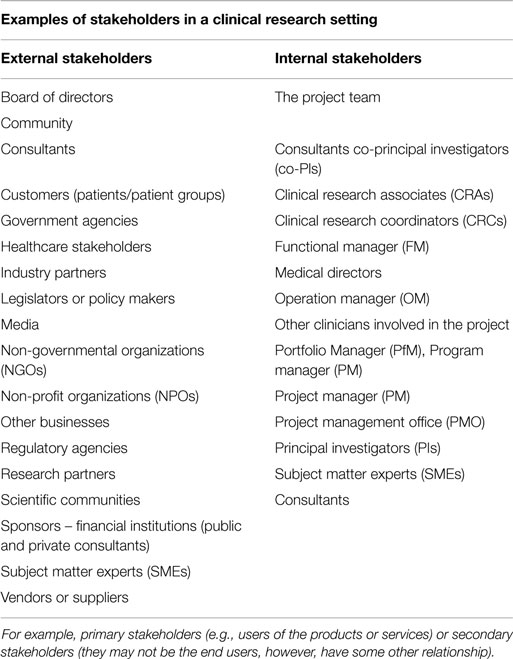

Expansion of STM

From the early 2000s, stakeholder theory has shown to be a class of management theory rather than an exclusive theory, per se, by its applicability in various business domains such as business ethics [ 40 – 42 ], finance [ 43 – 45 ], accounting [ 46 , 47 ], marketing [ 22 , 48 , 49 ] and management [ 21 , 50 , 51 ]. Afterwards, the interest has moved to stakeholder analysis—a main systematical analytical process for stakeholder management that involves identifying and categorizing stakeholders, and identifying best practices for engaging them [ 52 ]. Even some scientific disciplines, such as project management, has considered stakeholder management as one of its core knowledge areas for achieving project success [ 53 ]. This exponential growth of the field has resulted in more than 55 stakeholder definitions [ 54 ] and numerous frameworks for stakeholder identification [ 35 , 55 , 56 ], categorization [ 57 , 58 ], and engagement [ 59 – 62 ]. However, the enlargement of the stakeholder analysis body caused ambiguousness in its concepts and purpose [ 34 , 56 , 63 ], where it turned into an experimental field for different methods to be explored. Jepsen and Eskerod [ 64 ] revealed that the tools used for stakeholder identification and categorization were not clear enough for project managers to use, being referred to as theoretical [ 65 ].

The theoretical debates seemed to have alleviated between 2010 and 2020, where researchers focused instead on the applicability of stakeholder theory in the real world cases [ 66 , 67 ]. Empirical studies mainly examined the behavior of firms and their stakeholders towards each other, such as how firms manage stakeholders [ 68 , 69 ] and how stakeholders influence a firm [ 70 ]. Once again, the scientific paradigm of STM has mostly been uncovered in the domains of strategic management [ 71 , 72 ] and project management [ 73 – 75 ]. Therefore, it is evident that growth of STM has continued on a much larger scale than in the previous years, but little is known about the structure of collaboration networks that have contributed to its development and diversification.

Social network theories and measures

A social network is a web of relationships connecting different actors together (e.g., individuals, organisations, nations). The purpose of analyzing networks in scientific research is to evaluate the performance of certain research actors through the structure and patterns of their relationships, as well as to guide research funding and development of science [ 76 ]. Following previous works [ 52 , 77 ], SNA can be conducted through a variety of metrics such as ego-density at the network level; degree, betweenness and closeness centrality, efficiency and constraint at the actor level; and tie strength at the tie level [ 78 , 79 ].

At the network level, density is the most basic network concept which measures the widespread of connectivity throughout the network as a whole [ 80 ]. In other words, it explains the extent of social activity in a network by determining the percentage of ties present [ 81 ]. On the other hand, ego-network density is used to describe the extent of connectivity in an ego’s surrounding neighborhood [ 82 ]. In this study, the ego is either an author, institution or country. A dense network allows the dissemination of information throughout the network [ 83 ] and reflects a trustworthy environment for different actors [ 84 ]. However, a dense network is a two-edged sword where it might obstruct the ability of actors to access novel information outside their closely knitted cliques.

Actor level analysis was first pioneered through the “Bavelas–Leavitt Experiment” which involved five groups of undergraduate students, each had to communicate using a specific network structure (i.e. visualized as a ‘star’, ‘Y’, ‘circle’) to solve puzzles [ 85 , 86 ]. It was found that the efficiency of information flow between group members was the highest in the centralized structures (‘star’ and ‘Y’), leading to the formation of the network ‘centrality’ concept. Accordingly, Freeman [ 87 ] identified three measures of centrality which are degree, betweenness and closeness. Degree centrality that denotes the number of relationships a focal node has in the network. In other words, it is the number of co-authors associated with a given author. Degree centrality is mostly considered as a measure of ‘immediate influence’ or the ability of a node to directly affect others [ 88 , 89 ]. Betweenness centrality is the number of shortest paths (between all pairs of nodes) that pass through a certain node [ 52 ]. Betweenness centrality is a good estimate of power and influence a node can exert on the resource flow between other actors [ 87 , 90 , 91 ]. A node with high betweenness centrality can be considered as an actor that regularly plays a bridging role among other actors in a network. On the other hand, closeness centrality measures the distance between a node and others in a network and reflects the speed in which information is spread across the entire network [ 87 ]. An actor with high closeness centrality is considered independent and can easily reach other actors without relying on intermediaries [ 81 ].

Another important actor level theory is Burt’s [ 92 ] structural hole theory which highlights the importance of having holes (absence of ties) between actors to prevent redundant information. Otherwise, an actor can have redundant relationships by being connected to actors that themselves are connected, where maintaining these relationships could be costly and time consuming in which might constrain the performance of network actors. Burt proposed using ‘efficiency’ and ‘constraint’ to represent the presence of structural holes and redundant relationships, respectively.

Regarding tie level analysis, Granovetter [ 93 ] introduced the ‘strength of weak ties’ theory. He argued that individuals with weak relationships can obtain information at a faster rate than those with strong relationships. This is because individuals who are strongly connected to each other tend to share information most likely within their closely knitted clique than to transfer it to outsiders. In contrast, Krackhardt et al. [ 94 ] stressed on the importance of ‘strong ties’ to create a trustworthy environment, facilitate change and accelerate task completion. Additionally, Hansen [ 95 ] showed that strong ties rather than week ties can enhance the delivery of complex information.

Materials and methods

Data collection.

This paper used co-authorship information to explore collaborative networks. The ‘Web of Science’ database was utilized with the search being restricted to journal articles with strings of ["stakeholder management" or "stakeholder analysis" or "stakeholder identification" or "stakeholder theory" or "stakeholder engagement" or "stakeholder influence"] in their title, abstract or keywords. These are the most frequently used themes in stakeholder research to describe the concept of STM. Other types of documents such as conference proceedings, and books were excluded. The year 1989 was chosen as the outset date of our research because the results of Laplume et al. [ 96 ] and the web of science search showed that the first stakeholder-based scientific article was published in 1989.

In order to have a better understanding of the evolution of collaboration networks, different datasets were required. Therefore, the overall time period of 32 years was split into three consecutive sub-periods, that being t 1 : 1989–1999), t 2 : 2000–2010 and t 3 : 2011–2020. The bibliometric data for each phase was extracted independently in plain text format (compatible with Bibexcel package program for bibliometric analysis) and involved manuscript titles, authors’ names and affiliations, journal titles, institutional names, identification numbers, abstracts, keywords, publication dates, etc. Out of 21,173 authors, 3115 were duplicates, so 19,058 authors were sent for further analysis. The number of articles extracted was 85 for t 1 , 885 for t 2 and 5157 for t 3 , counting for a total number of 6127 articles.

Data refinement

The bibliometric datasets for the three sub-periods were imported into Bibexcel package program [ 97 ] for data preparation and co-occurrence analysis. Fig 1 summarizes the entire methodological process used for extracting and analyzing the data. The first issue encountered was to resolve name authority control problems (i.e. different entities with same names, or same entities with different names [ 27 ]. For instance, some journal articles were the same but had different titles (e.g., ‘Moving beyond dyadic ties’ and ‘Moving beyond Dyadic Ties: A Network Theory of Stakeholder Influences’). Therefore, a standardization process was conducted by removing duplicates (i.e., articles with same DOI were considered as one source). Moreover, it was important to convert upper and lower cases (e.g., WICKS AC, Wicks AC) of all records to a standard lower-case format (Wicks AC) to avoid duplication of records that might impact network structure. For some of the records, especially that of institutions and countries, it has been shown that co-occurrence has occurred between the same institutions and the same countries. In this case, the names were not brought together but kept apart due to the fact that collaboration has happened between authors of the same institution, or between institutions of the same country. In other words, self-loops were not excluded from our analysis. Using Bibexcel, we extracted social network data for each of the authors, institutions and countries networks and for each sub-period, that involved information about the presence and absence of relationships between the actors. Then, the data was imported into excel and manually scrutinized to correct possible spelling errors.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255658.g001

Social network analysis

The matrices were imported into an SNA program used by many network scholars—“UCINET 6.0” [ 98 ] to calculate the social network measures for each matrix. UCINET is a SNA software mainly used for whole network studies, which features a large number of network metrics to quantify patterns of relationships. Centrality measures were calculated for the authors, institutions and countries to determine those that are leading collaborative works in their networks. However, further network measures such as ego-density, efficiency, constraint and average tie strength were only calculated for the authors to cohesively understand the longitudinal effect of co-authorship networks on research performance.

Ego-density, degree centrality, betweenness centrality and closeness centrality, efficiency and constraint were calculated for each author, institution and country and for each sub-period.

To construct and visualize the collaboration networks of authors, institutions and countries, bibliometric data from WoS was directly imported into VOSviewer–a specialized software tool that visualizes networks based on scientific publications [ 103 ].

Data analysis

To understand the association between social network measures and research performance, the extracted social network measures from UCINET were imported into SPSS with the number of citations and documents published for each author. Correlation and T-tests determined whether a positive or a negative association exists between the explored variables.

Results and discussion

Descriptive results.

A total of 6127 articles were obtained from different journals between 1989 and 2020. As seen in Table 1 and Fig 2 , there is an exponential increase in the number of published articles. 85 articles were published in t 1 , 885 in t 2 and remarkably 5157 in t 3 . This shows that the majority of collaborative endeavors have occurred in the last decade with a 482% increase in the number of articles from t 2 to t 3 . The number of articles written by multi authors (three or more authors) in the last 32 years is 3590 (58.5%) which is much higher than double author articles (1603 articles, 26.16%) and single author articles (934 papers, 16.2%). Fig 2 shows that the number of published articles increased gradually from 2 to 44 articles between 1989 and 2004, with an exponential increase in 2005 and onwards (i.e., the number of publications in 2004 has been doubled in 2005). The period from 2014 and 2019 experienced the highest number of published articles, indicating the increased interest of the academic community in STM research.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255658.g002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255658.t001

Regarding institutional co-occurrence, it is evident that t 3 has witnessed the highest number of collaborative institutions (3778) than t 2 (879) and t 1 (132). Similarly, the number of collaborating countries was the highest (155) in t 3 and the lowest (16) in t 1 . Given that a scientific field might require 45 years to mature [ 104 ], the overall results show that the STM field moved from incubation ( t 1 ) to incremental growth ( t 2 ) to maturity ( t 3 ), reflected by the dramatic increase in the number of articles, institutions, countries and in the number of citations (106,466 in total) especially in t 3 (61,942).

Social network analysis results

Using SNA, the 10 most prolific and influential actors for each network (authors, institutions, countries) in each sub-period ( t 1 , t 2 , t 3 ) were identified.

Each node/circle represents a researcher who have published in the STM field. The size of each node size is proportional to the number of citations. A line connecting two nodes indicates an, at least, one published paper between two authors in STM field.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255658.g003

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255658.t002

This indicates that collaboration is in the form of sub-networks of closely knitted authors each forming their own collaborative clique. It is evident that collaboration is still premature with only 156 authors not well connected in the network. t 1 is known as the discovery period of stakeholder theory where it first appeared in management journals (e.g. Academy of Management Review) [ 32 ].

In t 2 , the collaboration network consists of 1957 authors and has become larger and more condensed than in t 1 . However, it is important to note that Table 1 earlier shows that 62% of articles (547 out of 885 articles) are single and double authored and only 38% (338 articles) are multi-authored. This finding can be noted in Network B, Fig 3 with the emergence of more than 1000 single and dyadic authors that have further fragmented the collaboration network as a whole. This disintegration of the stakeholder domain is expected because the stakeholder theory has a wide scope of interpretations and the term ‘stakeholder’ can mean different things to different people [ 105 ]. With the increase in stakeholder theoretical disputes between the moral justifications [ 41 ] and managerial implications of the theory [ 38 , 66 , 105 ], numerous solo, dyadic and triadic have risen, detaching from both the mainstream stakeholder theory research [ 34 , 35 ], and the large network cliques [ 106 , 107 ]. Perhaps, a reason why most of the prolific actors in t 1 did not make the list in t 2 is because new research areas have emerged, such as stakeholder engagement [ 108 , 109 ], stakeholder social network analysis [ 56 , 110 ], stakeholder involvement in policy decision making [ 111 ] and many more.

As it can be interpreted from the graphical visualization in Fig 3 , that the scenario observed in t 3 is very similar to that in t 2 , but with a larger network of 16,905 authors (763% increase in number of authors from t 2 ). In particular, the number of components has increased to 88 and expanded to include 12 actors. In contrast, network density–the percentage of existing ties over the total number of possible ties–has decreased from 1.8% in t 1 to 0.08% in t 3 . Although it seems intuitive that density would increase with new researchers entering the field, this did not seem to be the case where density decreased with further fragmentations that reduced the number of connections as the number of nodes increased. This finding is supported by a study [ 18 ] that found a decrease in network density of author collaboration networks from 0.026 in the 1980s to 0.003 in the 2000s. In the presence of 16905 authors with different research interests, it is nearly impossible to connect the majority of the nodes and achieve a high network density. The overlay color range in Network C, Fig 3 also shows that the majority of publications have occurred between 2014 and 2018 with few co-authorships noted in the last two years.

The SNA results presented in Table 2 show that Tugwell P is the most influential author in the network, followed by Graham ID, Newman PA, Dawkins JS and Walker CE who all have higher degree centrality scores than the rest. Remarkably, the findings of betweenness centrality in t 3 show an increase in the importance of the intermediary role, as all prominent actors (see Table 2 ) have a higher betweenness centrality score compared to that of t 1 and t 3 . The brokerage role is significant in t 3 with the decrease in degree and closeness scores. Therefore, the collaboration network has become more dependent on authors with a brokerage role in t 3 .