- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write the Results/Findings Section in Research

What is the research paper Results section and what does it do?

The Results section of a scientific research paper represents the core findings of a study derived from the methods applied to gather and analyze information. It presents these findings in a logical sequence without bias or interpretation from the author, setting up the reader for later interpretation and evaluation in the Discussion section. A major purpose of the Results section is to break down the data into sentences that show its significance to the research question(s).

The Results section appears third in the section sequence in most scientific papers. It follows the presentation of the Methods and Materials and is presented before the Discussion section —although the Results and Discussion are presented together in many journals. This section answers the basic question “What did you find in your research?”

What is included in the Results section?

The Results section should include the findings of your study and ONLY the findings of your study. The findings include:

- Data presented in tables, charts, graphs, and other figures (may be placed into the text or on separate pages at the end of the manuscript)

- A contextual analysis of this data explaining its meaning in sentence form

- All data that corresponds to the central research question(s)

- All secondary findings (secondary outcomes, subgroup analyses, etc.)

If the scope of the study is broad, or if you studied a variety of variables, or if the methodology used yields a wide range of different results, the author should present only those results that are most relevant to the research question stated in the Introduction section .

As a general rule, any information that does not present the direct findings or outcome of the study should be left out of this section. Unless the journal requests that authors combine the Results and Discussion sections, explanations and interpretations should be omitted from the Results.

How are the results organized?

The best way to organize your Results section is “logically.” One logical and clear method of organizing research results is to provide them alongside the research questions—within each research question, present the type of data that addresses that research question.

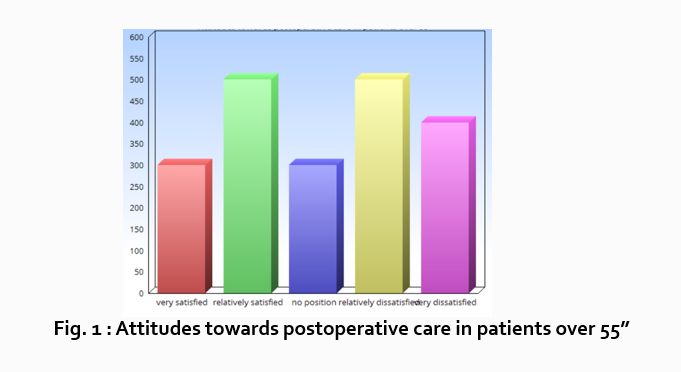

Let’s look at an example. Your research question is based on a survey among patients who were treated at a hospital and received postoperative care. Let’s say your first research question is:

“What do hospital patients over age 55 think about postoperative care?”

This can actually be represented as a heading within your Results section, though it might be presented as a statement rather than a question:

Attitudes towards postoperative care in patients over the age of 55

Now present the results that address this specific research question first. In this case, perhaps a table illustrating data from a survey. Likert items can be included in this example. Tables can also present standard deviations, probabilities, correlation matrices, etc.

Following this, present a content analysis, in words, of one end of the spectrum of the survey or data table. In our example case, start with the POSITIVE survey responses regarding postoperative care, using descriptive phrases. For example:

“Sixty-five percent of patients over 55 responded positively to the question “ Are you satisfied with your hospital’s postoperative care ?” (Fig. 2)

Include other results such as subcategory analyses. The amount of textual description used will depend on how much interpretation of tables and figures is necessary and how many examples the reader needs in order to understand the significance of your research findings.

Next, present a content analysis of another part of the spectrum of the same research question, perhaps the NEGATIVE or NEUTRAL responses to the survey. For instance:

“As Figure 1 shows, 15 out of 60 patients in Group A responded negatively to Question 2.”

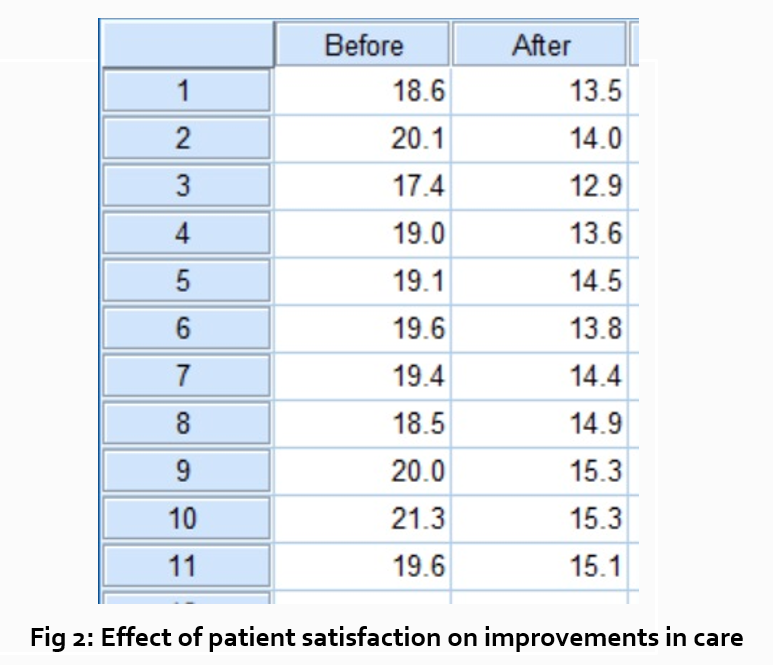

After you have assessed the data in one figure and explained it sufficiently, move on to your next research question. For example:

“How does patient satisfaction correspond to in-hospital improvements made to postoperative care?”

This kind of data may be presented through a figure or set of figures (for instance, a paired T-test table).

Explain the data you present, here in a table, with a concise content analysis:

“The p-value for the comparison between the before and after groups of patients was .03% (Fig. 2), indicating that the greater the dissatisfaction among patients, the more frequent the improvements that were made to postoperative care.”

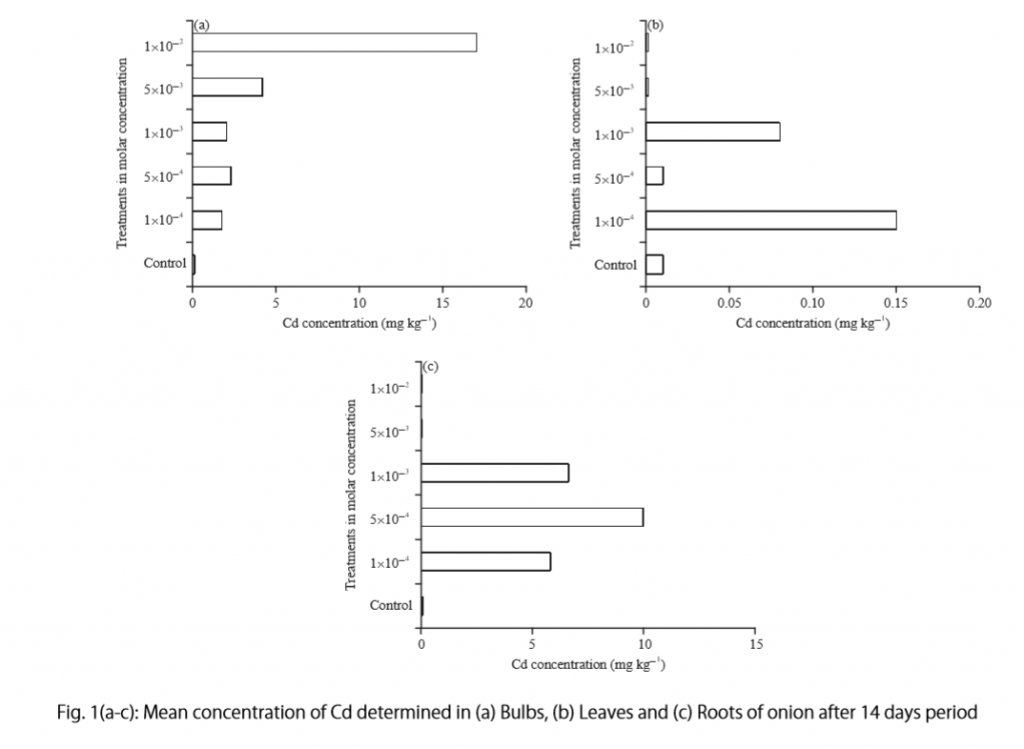

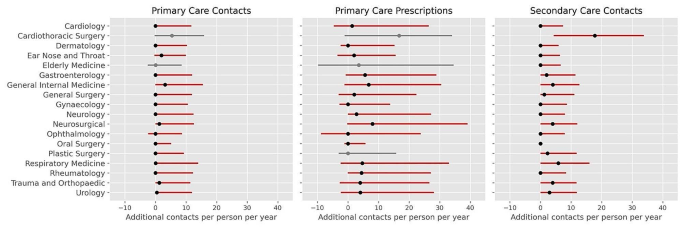

Let’s examine another example of a Results section from a study on plant tolerance to heavy metal stress . In the Introduction section, the aims of the study are presented as “determining the physiological and morphological responses of Allium cepa L. towards increased cadmium toxicity” and “evaluating its potential to accumulate the metal and its associated environmental consequences.” The Results section presents data showing how these aims are achieved in tables alongside a content analysis, beginning with an overview of the findings:

“Cadmium caused inhibition of root and leave elongation, with increasing effects at higher exposure doses (Fig. 1a-c).”

The figure containing this data is cited in parentheses. Note that this author has combined three graphs into one single figure. Separating the data into separate graphs focusing on specific aspects makes it easier for the reader to assess the findings, and consolidating this information into one figure saves space and makes it easy to locate the most relevant results.

Following this overall summary, the relevant data in the tables is broken down into greater detail in text form in the Results section.

- “Results on the bio-accumulation of cadmium were found to be the highest (17.5 mg kgG1) in the bulb, when the concentration of cadmium in the solution was 1×10G2 M and lowest (0.11 mg kgG1) in the leaves when the concentration was 1×10G3 M.”

Captioning and Referencing Tables and Figures

Tables and figures are central components of your Results section and you need to carefully think about the most effective way to use graphs and tables to present your findings . Therefore, it is crucial to know how to write strong figure captions and to refer to them within the text of the Results section.

The most important advice one can give here as well as throughout the paper is to check the requirements and standards of the journal to which you are submitting your work. Every journal has its own design and layout standards, which you can find in the author instructions on the target journal’s website. Perusing a journal’s published articles will also give you an idea of the proper number, size, and complexity of your figures.

Regardless of which format you use, the figures should be placed in the order they are referenced in the Results section and be as clear and easy to understand as possible. If there are multiple variables being considered (within one or more research questions), it can be a good idea to split these up into separate figures. Subsequently, these can be referenced and analyzed under separate headings and paragraphs in the text.

To create a caption, consider the research question being asked and change it into a phrase. For instance, if one question is “Which color did participants choose?”, the caption might be “Color choice by participant group.” Or in our last research paper example, where the question was “What is the concentration of cadmium in different parts of the onion after 14 days?” the caption reads:

“Fig. 1(a-c): Mean concentration of Cd determined in (a) bulbs, (b) leaves, and (c) roots of onions after a 14-day period.”

Steps for Composing the Results Section

Because each study is unique, there is no one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to designing a strategy for structuring and writing the section of a research paper where findings are presented. The content and layout of this section will be determined by the specific area of research, the design of the study and its particular methodologies, and the guidelines of the target journal and its editors. However, the following steps can be used to compose the results of most scientific research studies and are essential for researchers who are new to preparing a manuscript for publication or who need a reminder of how to construct the Results section.

Step 1 : Consult the guidelines or instructions that the target journal or publisher provides authors and read research papers it has published, especially those with similar topics, methods, or results to your study.

- The guidelines will generally outline specific requirements for the results or findings section, and the published articles will provide sound examples of successful approaches.

- Note length limitations on restrictions on content. For instance, while many journals require the Results and Discussion sections to be separate, others do not—qualitative research papers often include results and interpretations in the same section (“Results and Discussion”).

- Reading the aims and scope in the journal’s “ guide for authors ” section and understanding the interests of its readers will be invaluable in preparing to write the Results section.

Step 2 : Consider your research results in relation to the journal’s requirements and catalogue your results.

- Focus on experimental results and other findings that are especially relevant to your research questions and objectives and include them even if they are unexpected or do not support your ideas and hypotheses.

- Catalogue your findings—use subheadings to streamline and clarify your report. This will help you avoid excessive and peripheral details as you write and also help your reader understand and remember your findings. Create appendices that might interest specialists but prove too long or distracting for other readers.

- Decide how you will structure of your results. You might match the order of the research questions and hypotheses to your results, or you could arrange them according to the order presented in the Methods section. A chronological order or even a hierarchy of importance or meaningful grouping of main themes or categories might prove effective. Consider your audience, evidence, and most importantly, the objectives of your research when choosing a structure for presenting your findings.

Step 3 : Design figures and tables to present and illustrate your data.

- Tables and figures should be numbered according to the order in which they are mentioned in the main text of the paper.

- Information in figures should be relatively self-explanatory (with the aid of captions), and their design should include all definitions and other information necessary for readers to understand the findings without reading all of the text.

- Use tables and figures as a focal point to tell a clear and informative story about your research and avoid repeating information. But remember that while figures clarify and enhance the text, they cannot replace it.

Step 4 : Draft your Results section using the findings and figures you have organized.

- The goal is to communicate this complex information as clearly and precisely as possible; precise and compact phrases and sentences are most effective.

- In the opening paragraph of this section, restate your research questions or aims to focus the reader’s attention to what the results are trying to show. It is also a good idea to summarize key findings at the end of this section to create a logical transition to the interpretation and discussion that follows.

- Try to write in the past tense and the active voice to relay the findings since the research has already been done and the agent is usually clear. This will ensure that your explanations are also clear and logical.

- Make sure that any specialized terminology or abbreviation you have used here has been defined and clarified in the Introduction section .

Step 5 : Review your draft; edit and revise until it reports results exactly as you would like to have them reported to your readers.

- Double-check the accuracy and consistency of all the data, as well as all of the visual elements included.

- Read your draft aloud to catch language errors (grammar, spelling, and mechanics), awkward phrases, and missing transitions.

- Ensure that your results are presented in the best order to focus on objectives and prepare readers for interpretations, valuations, and recommendations in the Discussion section . Look back over the paper’s Introduction and background while anticipating the Discussion and Conclusion sections to ensure that the presentation of your results is consistent and effective.

- Consider seeking additional guidance on your paper. Find additional readers to look over your Results section and see if it can be improved in any way. Peers, professors, or qualified experts can provide valuable insights.

One excellent option is to use a professional English proofreading and editing service such as Wordvice, including our paper editing service . With hundreds of qualified editors from dozens of scientific fields, Wordvice has helped thousands of authors revise their manuscripts and get accepted into their target journals. Read more about the proofreading and editing process before proceeding with getting academic editing services and manuscript editing services for your manuscript.

As the representation of your study’s data output, the Results section presents the core information in your research paper. By writing with clarity and conciseness and by highlighting and explaining the crucial findings of their study, authors increase the impact and effectiveness of their research manuscripts.

For more articles and videos on writing your research manuscript, visit Wordvice’s Resources page.

Wordvice Resources

- How to Write a Research Paper Introduction

- Which Verb Tenses to Use in a Research Paper

- How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Paper Title

- Useful Phrases for Academic Writing

- Common Transition Terms in Academic Papers

- Active and Passive Voice in Research Papers

- 100+ Verbs That Will Make Your Research Writing Amazing

- Tips for Paraphrasing in Research Papers

- How it works

How to Write the Dissertation Findings or Results – Steps & Tips

Published by Grace Graffin at August 11th, 2021 , Revised On October 9, 2023

Each part of the dissertation is unique, and some general and specific rules must be followed. The dissertation’s findings section presents the key results of your research without interpreting their meaning .

Theoretically, this is an exciting section of a dissertation because it involves writing what you have observed and found. However, it can be a little tricky if there is too much information to confuse the readers.

The goal is to include only the essential and relevant findings in this section. The results must be presented in an orderly sequence to provide clarity to the readers.

This section of the dissertation should be easy for the readers to follow, so you should avoid going into a lengthy debate over the interpretation of the results.

It is vitally important to focus only on clear and precise observations. The findings chapter of the dissertation is theoretically the easiest to write.

It includes statistical analysis and a brief write-up about whether or not the results emerging from the analysis are significant. This segment should be written in the past sentence as you describe what you have done in the past.

This article will provide detailed information about how to write the findings of a dissertation .

When to Write Dissertation Findings Chapter

As soon as you have gathered and analysed your data, you can start to write up the findings chapter of your dissertation paper. Remember that it is your chance to report the most notable findings of your research work and relate them to the research hypothesis or research questions set out in the introduction chapter of the dissertation .

You will be required to separately report your study’s findings before moving on to the discussion chapter if your dissertation is based on the collection of primary data or experimental work.

However, you may not be required to have an independent findings chapter if your dissertation is purely descriptive and focuses on the analysis of case studies or interpretation of texts.

- Always report the findings of your research in the past tense.

- The dissertation findings chapter varies from one project to another, depending on the data collected and analyzed.

- Avoid reporting results that are not relevant to your research questions or research hypothesis.

Does your Dissertation Have the Following?

- Great Research/Sources

- Perfect Language

- Accurate Sources

If not, we can help. Our panel of experts makes sure to keep the 3 pillars of the Dissertation strong.

1. Reporting Quantitative Findings

The best way to present your quantitative findings is to structure them around the research hypothesis or questions you intend to address as part of your dissertation project.

Report the relevant findings for each research question or hypothesis, focusing on how you analyzed them.

Analysis of your findings will help you determine how they relate to the different research questions and whether they support the hypothesis you formulated.

While you must highlight meaningful relationships, variances, and tendencies, it is important not to guess their interpretations and implications because this is something to save for the discussion and conclusion chapters.

Any findings not directly relevant to your research questions or explanations concerning the data collection process should be added to the dissertation paper’s appendix section.

Use of Figures and Tables in Dissertation Findings

Suppose your dissertation is based on quantitative research. In that case, it is important to include charts, graphs, tables, and other visual elements to help your readers understand the emerging trends and relationships in your findings.

Repeating information will give the impression that you are short on ideas. Refer to all charts, illustrations, and tables in your writing but avoid recurrence.

The text should be used only to elaborate and summarize certain parts of your results. On the other hand, illustrations and tables are used to present multifaceted data.

It is recommended to give descriptive labels and captions to all illustrations used so the readers can figure out what each refers to.

How to Report Quantitative Findings

Here is an example of how to report quantitative results in your dissertation findings chapter;

Two hundred seventeen participants completed both the pretest and post-test and a Pairwise T-test was used for the analysis. The quantitative data analysis reveals a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of the pretest and posttest scales from the Teachers Discovering Computers course. The pretest mean was 29.00 with a standard deviation of 7.65, while the posttest mean was 26.50 with a standard deviation of 9.74 (Table 1). These results yield a significance level of .000, indicating a strong treatment effect (see Table 3). With the correlation between the scores being .448, the little relationship is seen between the pretest and posttest scores (Table 2). This leads the researcher to conclude that the impact of the course on the educators’ perception and integration of technology into the curriculum is dramatic.

Paired Samples

Paired samples correlation, paired samples test.

Also Read: How to Write the Abstract for the Dissertation.

2. Reporting Qualitative Findings

A notable issue with reporting qualitative findings is that not all results directly relate to your research questions or hypothesis.

The best way to present the results of qualitative research is to frame your findings around the most critical areas or themes you obtained after you examined the data.

In-depth data analysis will help you observe what the data shows for each theme. Any developments, relationships, patterns, and independent responses directly relevant to your research question or hypothesis should be mentioned to the readers.

Additional information not directly relevant to your research can be included in the appendix .

How to Report Qualitative Findings

Here is an example of how to report qualitative results in your dissertation findings chapter;

How do I report quantitative findings?

The best way to present your quantitative findings is to structure them around the research hypothesis or research questions you intended to address as part of your dissertation project. Report the relevant findings for each of the research questions or hypotheses, focusing on how you analyzed them.

How do I report qualitative findings?

The best way to present the qualitative research results is to frame your findings around the most important areas or themes that you obtained after examining the data.

An in-depth analysis of the data will help you observe what the data is showing for each theme. Any developments, relationships, patterns, and independent responses that are directly relevant to your research question or hypothesis should be clearly mentioned for the readers.

Can I use interpretive phrases like ‘it confirms’ in the finding chapter?

No, It is highly advisable to avoid using interpretive and subjective phrases in the finding chapter. These terms are more suitable for the discussion chapter , where you will be expected to provide your interpretation of the results in detail.

Can I report the results from other research papers in my findings chapter?

NO, you must not be presenting results from other research studies in your findings.

You May Also Like

Dissertation discussion is where you explore the relevance and significance of results. Here are guidelines to help you write the perfect discussion chapter.

Table of contents is an essential part of dissertation paper. Here is all you need to know about how to create the best table of contents for dissertation.

Here are the steps to make a theoretical framework for dissertation. You can define, discuss and evaluate theories relevant to the research problem.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

The Ultimate Guide to Crafting Impactful Recommendations in Research

Are you ready to take your research to the next level? Crafting impactful recommendations is the key to unlocking the full potential of your study. By providing clear, actionable suggestions based on your findings, you can bridge the gap between research and real-world application.

In this ultimate guide, we'll show you how to write recommendations that make a difference in your research report or paper.

You'll learn how to craft specific, actionable recommendations that connect seamlessly with your research findings. Whether you're a student, writer, teacher, or journalist, this guide will help you master the art of writing recommendations in research. Let's get started and make your research count!

Understanding the Purpose of Recommendations

Recommendations in research serve as a vital bridge between your findings and their real-world applications. They provide specific, action-oriented suggestions to guide future studies and decision-making processes. Let's dive into the key purposes of crafting effective recommendations:

Guiding Future Research

Research recommendations play a crucial role in steering scholars and researchers towards promising avenues of exploration. By highlighting gaps in current knowledge and proposing new research questions, recommendations help advance the field and drive innovation.

Influencing Decision-Making

Well-crafted recommendations have the power to shape policies, programs, and strategies across various domains, such as:

- Policy-making

- Product development

- Marketing strategies

- Medical practice

By providing clear, evidence-based suggestions, recommendations facilitate informed decision-making and improve outcomes.

Connecting Research to Practice

Recommendations act as a conduit for transferring knowledge from researchers to practitioners, policymakers, and stakeholders. They bridge the gap between academic findings and their practical applications, ensuring that research insights are effectively translated into real-world solutions.

Enhancing Research Impact

By crafting impactful recommendations, you can amplify the reach and influence of your research, attracting attention from peers, funding agencies, and decision-makers.

Addressing Limitations

Recommendations provide an opportunity to acknowledge and address the limitations of your study. By suggesting concrete and actionable possibilities for future research, you demonstrate a thorough understanding of your work's scope and potential areas for improvement.

Identifying Areas for Future Research

Discovering research gaps is a crucial step in crafting impactful recommendations. It involves reviewing existing studies and identifying unanswered questions or problems that warrant further investigation. Here are some strategies to help you identify areas for future research:

Explore Research Limitations

Take a close look at the limitations section of relevant studies. These limitations often provide valuable insights into potential areas for future research. Consider how addressing these limitations could enhance our understanding of the topic at hand.

Critically Analyze Discussion and Future Research Sections

When reading articles, pay special attention to the discussion and future research sections. These sections often highlight gaps in the current knowledge base and propose avenues for further exploration. Take note of any recurring themes or unanswered questions that emerge across multiple studies.

Utilize Targeted Search Terms

To streamline your search for research gaps, use targeted search terms such as "literature gap" or "future research" in combination with your subject keywords. This approach can help you quickly identify articles that explicitly discuss areas for future investigation.

Seek Guidance from Experts

Don't hesitate to reach out to your research advisor or other experts in your field. Their wealth of knowledge and experience can provide valuable insights into potential research gaps and emerging trends.

By employing these strategies, you'll be well-equipped to identify research gaps and craft recommendations that push the boundaries of current knowledge. Remember, the goal is to refine your research questions and focus your efforts on areas where more understanding is needed.

Structuring Your Recommendations

When it comes to structuring your recommendations, it's essential to keep them concise, organized, and tailored to your audience. Here are some key tips to help you craft impactful recommendations:

Prioritize and Organize

- Limit your recommendations to the most relevant and targeted suggestions for your peers or colleagues in the field.

- Place your recommendations at the end of the report, as they are often top of mind for readers.

- Write your recommendations in order of priority, with the most important ones for decision-makers coming first.

Use a Clear and Actionable Format

- Write recommendations in a clear, concise manner using actionable words derived from the data analyzed in your research.

- Use bullet points instead of long paragraphs for clarity and readability.

- Ensure that your recommendations are specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and timely (SMART).

Connect Recommendations to Research

By following this simple formula, you can ensure that your recommendations are directly connected to your research and supported by a clear rationale.

Tailor to Your Audience

- Consider the needs and interests of your target audience when crafting your recommendations.

- Explain how your recommendations can solve the issues explored in your research.

- Acknowledge any limitations or constraints of your study that may impact the implementation of your recommendations.

Avoid Common Pitfalls

- Don't undermine your own work by suggesting incomplete or unnecessary recommendations.

- Avoid using recommendations as a place for self-criticism or introducing new information not covered in your research.

- Ensure that your recommendations are achievable and comprehensive, offering practical solutions for the issues considered in your paper.

By structuring your recommendations effectively, you can enhance the reliability and validity of your research findings, provide valuable strategies and suggestions for future research, and deliver impactful solutions to real-world problems.

Crafting Actionable and Specific Recommendations

Crafting actionable and specific recommendations is the key to ensuring your research findings have a real-world impact. Here are some essential tips to keep in mind:

Embrace Flexibility and Feasibility

Your recommendations should be open to discussion and new information, rather than being set in stone. Consider the following:

- Be realistic and considerate of your team's capabilities when making recommendations.

- Prioritize recommendations based on impact and reach, but be prepared to adjust based on team effort levels.

- Focus on solutions that require the fewest changes first, adopting an MVP (Minimum Viable Product) approach.

Provide Detailed and Justified Recommendations

To avoid vagueness and misinterpretation, ensure your recommendations are:

- Detailed, including photos, videos, or screenshots whenever possible.

- Justified based on research findings, providing alternatives when findings don't align with expectations or business goals.

Use this formula when writing recommendations:

Observed problem/pain point/unmet need + consequence + potential solution

Adopt a Solution-Oriented Approach

Foster collaboration and participation.

- Promote staff education on current research and create strategies to encourage adoption of promising clinical protocols.

- Include representatives from the treatment community in the development of the research initiative and the review of proposals.

- Require active, early, and permanent participation of treatment staff in the development, implementation, and interpretation of the study.

Tailor Recommendations to the Opportunity

When writing recommendations for a specific opportunity or program:

- Highlight the strengths and qualifications of the researcher.

- Provide specific examples of their work and accomplishments.

- Explain how their research has contributed to the field.

- Emphasize the researcher's potential for future success and their unique contributions.

By following these guidelines, you'll craft actionable and specific recommendations that drive meaningful change and showcase the value of your research.

Connecting Recommendations with Research Findings

Connecting your recommendations with research findings is crucial for ensuring the credibility and impact of your suggestions. Here's how you can seamlessly link your recommendations to the evidence uncovered in your study:

Grounding Recommendations in Research

Your recommendations should be firmly rooted in the data and insights gathered during your research process. Avoid including measures or suggestions that were not discussed or supported by your study findings. This approach ensures that your recommendations are evidence-based and directly relevant to the research at hand.

Highlighting the Significance of Collaboration

Research collaborations offer a wealth of benefits that can enhance an agency's competitive position. Consider the following factors when discussing the importance of collaboration in your recommendations:

- Organizational Development: Participation in research collaborations depends on an agency's stage of development, compatibility with its mission and culture, and financial stability.

- Trust-Building: Long-term collaboration success often hinges on a history of increasing involvement and trust between partners.

- Infrastructure: A permanent infrastructure that facilitates long-term development is key to successful collaborative programs.

Emphasizing Commitment and Participation

Fostering quality improvement and organizational learning.

In your recommendations, highlight the importance of enhancing quality improvement strategies and fostering organizational learning. Show sensitivity to the needs and constraints of community-based programs, as this understanding is crucial for effective collaboration and implementation.

Addressing Limitations and Implications

If not already addressed in the discussion section, your recommendations should mention the limitations of the study and their implications. Examples of limitations include:

- Sample size or composition

- Participant attrition

- Study duration

By acknowledging these limitations, you demonstrate a comprehensive understanding of your research and its potential impact.

By connecting your recommendations with research findings, you provide a solid foundation for your suggestions, emphasize the significance of collaboration, and showcase the potential for future research and practical applications.

Crafting impactful recommendations is a vital skill for any researcher looking to bridge the gap between their findings and real-world applications. By understanding the purpose of recommendations, identifying areas for future research, structuring your suggestions effectively, and connecting them to your research findings, you can unlock the full potential of your study. Remember to prioritize actionable, specific, and evidence-based recommendations that foster collaboration and drive meaningful change.

As you embark on your research journey, embrace the power of well-crafted recommendations to amplify the impact of your work. By following the guidelines outlined in this ultimate guide, you'll be well-equipped to write recommendations that resonate with your audience, inspire further investigation, and contribute to the advancement of your field. So go forth, make your research count, and let your recommendations be the catalyst for positive change.

Q: What are the steps to formulating recommendations in research? A: To formulate recommendations in research, you should first gain a thorough understanding of the research question. Review the existing literature to inform your recommendations and consider the research methods that were used. Identify which data collection techniques were employed and propose suitable data analysis methods. It's also essential to consider any limitations and ethical considerations of your research. Justify your recommendations clearly and finally, provide a summary of your recommendations.

Q: Why are recommendations significant in research studies? A: Recommendations play a crucial role in research as they form a key part of the analysis phase. They provide specific suggestions for interventions or strategies that address the problems and limitations discovered during the study. Recommendations are a direct response to the main findings derived from data collection and analysis, and they can guide future actions or research.

Q: Can you outline the seven steps involved in writing a research paper? A: Certainly. The seven steps to writing an excellent research paper include:

- Allowing yourself sufficient time to complete the paper.

- Defining the scope of your essay and crafting a clear thesis statement.

- Conducting a thorough yet focused search for relevant research materials.

- Reading the research materials carefully and taking detailed notes.

- Writing your paper based on the information you've gathered and analyzed.

- Editing your paper to ensure clarity, coherence, and correctness.

- Submitting your paper following the guidelines provided.

Q: What tips can help make a research paper more effective? A: To enhance the effectiveness of a research paper, plan for the extensive process ahead and understand your audience. Decide on the structure your research writing will take and describe your methodology clearly. Write in a straightforward and clear manner, avoiding the use of clichés or overly complex language.

Sign up for more like this.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 8. The Discussion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The purpose of the discussion section is to interpret and describe the significance of your findings in relation to what was already known about the research problem being investigated and to explain any new understanding or insights that emerged as a result of your research. The discussion will always connect to the introduction by way of the research questions or hypotheses you posed and the literature you reviewed, but the discussion does not simply repeat or rearrange the first parts of your paper; the discussion clearly explains how your study advanced the reader's understanding of the research problem from where you left them at the end of your review of prior research.

Annesley, Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Peacock, Matthew. “Communicative Moves in the Discussion Section of Research Articles.” System 30 (December 2002): 479-497.

Importance of a Good Discussion

The discussion section is often considered the most important part of your research paper because it:

- Most effectively demonstrates your ability as a researcher to think critically about an issue, to develop creative solutions to problems based upon a logical synthesis of the findings, and to formulate a deeper, more profound understanding of the research problem under investigation;

- Presents the underlying meaning of your research, notes possible implications in other areas of study, and explores possible improvements that can be made in order to further develop the concerns of your research;

- Highlights the importance of your study and how it can contribute to understanding the research problem within the field of study;

- Presents how the findings from your study revealed and helped fill gaps in the literature that had not been previously exposed or adequately described; and,

- Engages the reader in thinking critically about issues based on an evidence-based interpretation of findings; it is not governed strictly by objective reporting of information.

Annesley Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Bitchener, John and Helen Basturkmen. “Perceptions of the Difficulties of Postgraduate L2 Thesis Students Writing the Discussion Section.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 5 (January 2006): 4-18; Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Rules

These are the general rules you should adopt when composing your discussion of the results :

- Do not be verbose or repetitive; be concise and make your points clearly

- Avoid the use of jargon or undefined technical language

- Follow a logical stream of thought; in general, interpret and discuss the significance of your findings in the same sequence you described them in your results section [a notable exception is to begin by highlighting an unexpected result or a finding that can grab the reader's attention]

- Use the present verb tense, especially for established facts; however, refer to specific works or prior studies in the past tense

- If needed, use subheadings to help organize your discussion or to categorize your interpretations into themes

II. The Content

The content of the discussion section of your paper most often includes :

- Explanation of results : Comment on whether or not the results were expected for each set of findings; go into greater depth to explain findings that were unexpected or especially profound. If appropriate, note any unusual or unanticipated patterns or trends that emerged from your results and explain their meaning in relation to the research problem.

- References to previous research : Either compare your results with the findings from other studies or use the studies to support a claim. This can include re-visiting key sources already cited in your literature review section, or, save them to cite later in the discussion section if they are more important to compare with your results instead of being a part of the general literature review of prior research used to provide context and background information. Note that you can make this decision to highlight specific studies after you have begun writing the discussion section.

- Deduction : A claim for how the results can be applied more generally. For example, describing lessons learned, proposing recommendations that can help improve a situation, or highlighting best practices.

- Hypothesis : A more general claim or possible conclusion arising from the results [which may be proved or disproved in subsequent research]. This can be framed as new research questions that emerged as a consequence of your analysis.

III. Organization and Structure

Keep the following sequential points in mind as you organize and write the discussion section of your paper:

- Think of your discussion as an inverted pyramid. Organize the discussion from the general to the specific, linking your findings to the literature, then to theory, then to practice [if appropriate].

- Use the same key terms, narrative style, and verb tense [present] that you used when describing the research problem in your introduction.

- Begin by briefly re-stating the research problem you were investigating and answer all of the research questions underpinning the problem that you posed in the introduction.

- Describe the patterns, principles, and relationships shown by each major findings and place them in proper perspective. The sequence of this information is important; first state the answer, then the relevant results, then cite the work of others. If appropriate, refer the reader to a figure or table to help enhance the interpretation of the data [either within the text or as an appendix].

- Regardless of where it's mentioned, a good discussion section includes analysis of any unexpected findings. This part of the discussion should begin with a description of the unanticipated finding, followed by a brief interpretation as to why you believe it appeared and, if necessary, its possible significance in relation to the overall study. If more than one unexpected finding emerged during the study, describe each of them in the order they appeared as you gathered or analyzed the data. As noted, the exception to discussing findings in the same order you described them in the results section would be to begin by highlighting the implications of a particularly unexpected or significant finding that emerged from the study, followed by a discussion of the remaining findings.

- Before concluding the discussion, identify potential limitations and weaknesses if you do not plan to do so in the conclusion of the paper. Comment on their relative importance in relation to your overall interpretation of the results and, if necessary, note how they may affect the validity of your findings. Avoid using an apologetic tone; however, be honest and self-critical [e.g., in retrospect, had you included a particular question in a survey instrument, additional data could have been revealed].

- The discussion section should end with a concise summary of the principal implications of the findings regardless of their significance. Give a brief explanation about why you believe the findings and conclusions of your study are important and how they support broader knowledge or understanding of the research problem. This can be followed by any recommendations for further research. However, do not offer recommendations which could have been easily addressed within the study. This would demonstrate to the reader that you have inadequately examined and interpreted the data.

IV. Overall Objectives

The objectives of your discussion section should include the following: I. Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings

Briefly reiterate the research problem or problems you are investigating and the methods you used to investigate them, then move quickly to describe the major findings of the study. You should write a direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results, usually in one paragraph.

II. Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important

No one has thought as long and hard about your study as you have. Systematically explain the underlying meaning of your findings and state why you believe they are significant. After reading the discussion section, you want the reader to think critically about the results and why they are important. You don’t want to force the reader to go through the paper multiple times to figure out what it all means. If applicable, begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most significant or unanticipated finding first, then systematically review each finding. Otherwise, follow the general order you reported the findings presented in the results section.

III. Relate the Findings to Similar Studies

No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for your research. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps to support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your study differs from other research about the topic. Note that any significant or unanticipated finding is often because there was no prior research to indicate the finding could occur. If there is prior research to indicate this, you need to explain why it was significant or unanticipated. IV. Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings

It is important to remember that the purpose of research in the social sciences is to discover and not to prove . When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations for the study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. This is especially important when describing the discovery of significant or unanticipated findings.

V. Acknowledge the Study’s Limitations

It is far better for you to identify and acknowledge your study’s limitations than to have them pointed out by your professor! Note any unanswered questions or issues your study could not address and describe the generalizability of your results to other situations. If a limitation is applicable to the method chosen to gather information, then describe in detail the problems you encountered and why. VI. Make Suggestions for Further Research

You may choose to conclude the discussion section by making suggestions for further research [as opposed to offering suggestions in the conclusion of your paper]. Although your study can offer important insights about the research problem, this is where you can address other questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or highlight hidden issues that were revealed as a result of conducting your research. You should frame your suggestions by linking the need for further research to the limitations of your study [e.g., in future studies, the survey instrument should include more questions that ask..."] or linking to critical issues revealed from the data that were not considered initially in your research.

NOTE: Besides the literature review section, the preponderance of references to sources is usually found in the discussion section . A few historical references may be helpful for perspective, but most of the references should be relatively recent and included to aid in the interpretation of your results, to support the significance of a finding, and/or to place a finding within a particular context. If a study that you cited does not support your findings, don't ignore it--clearly explain why your research findings differ from theirs.

V. Problems to Avoid

- Do not waste time restating your results . Should you need to remind the reader of a finding to be discussed, use "bridge sentences" that relate the result to the interpretation. An example would be: “In the case of determining available housing to single women with children in rural areas of Texas, the findings suggest that access to good schools is important...," then move on to further explaining this finding and its implications.

- As noted, recommendations for further research can be included in either the discussion or conclusion of your paper, but do not repeat your recommendations in the both sections. Think about the overall narrative flow of your paper to determine where best to locate this information. However, if your findings raise a lot of new questions or issues, consider including suggestions for further research in the discussion section.

- Do not introduce new results in the discussion section. Be wary of mistaking the reiteration of a specific finding for an interpretation because it may confuse the reader. The description of findings [results section] and the interpretation of their significance [discussion section] should be distinct parts of your paper. If you choose to combine the results section and the discussion section into a single narrative, you must be clear in how you report the information discovered and your own interpretation of each finding. This approach is not recommended if you lack experience writing college-level research papers.

- Use of the first person pronoun is generally acceptable. Using first person singular pronouns can help emphasize a point or illustrate a contrasting finding. However, keep in mind that too much use of the first person can actually distract the reader from the main points [i.e., I know you're telling me this--just tell me!].

Analyzing vs. Summarizing. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University; Discussion. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Hess, Dean R. "How to Write an Effective Discussion." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004); Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sauaia, A. et al. "The Anatomy of an Article: The Discussion Section: "How Does the Article I Read Today Change What I Will Recommend to my Patients Tomorrow?” The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 74 (June 2013): 1599-1602; Research Limitations & Future Research . Lund Research Ltd., 2012; Summary: Using it Wisely. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Discussion. Writing in Psychology course syllabus. University of Florida; Yellin, Linda L. A Sociology Writer's Guide . Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2009.

Writing Tip

Don’t Over-Interpret the Results!

Interpretation is a subjective exercise. As such, you should always approach the selection and interpretation of your findings introspectively and to think critically about the possibility of judgmental biases unintentionally entering into discussions about the significance of your work. With this in mind, be careful that you do not read more into the findings than can be supported by the evidence you have gathered. Remember that the data are the data: nothing more, nothing less.

MacCoun, Robert J. "Biases in the Interpretation and Use of Research Results." Annual Review of Psychology 49 (February 1998): 259-287; Ward, Paulet al, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Expertise . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Write Two Results Sections!

One of the most common mistakes that you can make when discussing the results of your study is to present a superficial interpretation of the findings that more or less re-states the results section of your paper. Obviously, you must refer to your results when discussing them, but focus on the interpretation of those results and their significance in relation to the research problem, not the data itself.

Azar, Beth. "Discussing Your Findings." American Psychological Association gradPSYCH Magazine (January 2006).

Yet Another Writing Tip

Avoid Unwarranted Speculation!

The discussion section should remain focused on the findings of your study. For example, if the purpose of your research was to measure the impact of foreign aid on increasing access to education among disadvantaged children in Bangladesh, it would not be appropriate to speculate about how your findings might apply to populations in other countries without drawing from existing studies to support your claim or if analysis of other countries was not a part of your original research design. If you feel compelled to speculate, do so in the form of describing possible implications or explaining possible impacts. Be certain that you clearly identify your comments as speculation or as a suggestion for where further research is needed. Sometimes your professor will encourage you to expand your discussion of the results in this way, while others don’t care what your opinion is beyond your effort to interpret the data in relation to the research problem.

- << Previous: Using Non-Textual Elements

- Next: Limitations of the Study >>

- Last Updated: May 9, 2024 11:05 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Finding Relevant Scholarly Research for Literature Review: How can we be systematic?

On an average, it takes 15 clicks for a researcher to find an article (which may or may not be related to their research topic) online. This time is not productive because it does not help them gain any knowledge and it could potentially be spent doing something more vital in fostering research and development. Moreover, as most researchers rely on two to three databases to find information for their literature review , the time to find relevant scholarly research data also increases.

Table of Contents

Navigating Through Multiple Scholarly Databases—Is it even necessary?

The Internet has revolutionized the way we access information. Websites and online resources within and outside of academic bibliography are significant resources of literature. However, the challenge in searching and managing the results is undeniable.

Considering the exponential growth in scholarly research data and literature, finding relevant information and reporting your research sooner is imperative. While Open Science has been a positive reform of information access, not all data is available at a click, let alone the relevant one. Researchers fear the possibility of missing out on critical information related to their research topic or accidentally committing plagiarism. Hence, they spend time in toggling through multiple scholarly databases.

In this process of searching for literature on multiple databases, researchers tend to download irrelevant information too. Furthermore, the probability of finding similar resources on multiple databases is higher if the resource is on an Open Access platform. These downloaded papers not only occupy the space in reference managers but also make researchers spend a lot of time deciding whether the paper is worth reading or not.

5 Major Challenges Faced on Multiple Scholarly Databases—How to overcome them?

Finding scholarly research data involves navigating through institutional login pages, subscriptions, and paywalls. Apart from the time, effort, and money spent there are several other challenges that researchers encounter while searching literature on multiple scholarly databases.

Here we discuss 5 major challenges faced by researchers while using multiple scholarly databases:

1. Identifying and Deciding the Resources to Search

The Internet provides information in numerous formats, viz. journal articles, preprints, video recordings, podcasts, infographics, conference proceedings, etc. This wide pool of knowledge gets deeper with advances in scholarly research and literature. Hence, while finding research data on multiple scholarly databases in multiple formats, it becomes difficult to identify and decide the resources to download based on their relevance to the research topic. However, these resources can be easily traced if they all are on a single platform.

2. Search or Navigate Resources Correctly

Researchers use keywords and questions to find scholarly data related to their topic of interest. Databases search for the exact words and phrases. Hence, if researchers use a different word or a synonym that describes the concept, the search results are not relevant. If a single database with optimized keywords is used to access billions of scholarly resources, it not only avoids information overload but also allows navigation of relevant information.

3. Assessing Obtained Search Results

Information overload makes it difficult for researchers to assess every discovered resource. One cannot decide the relevancy of search results based on the research paper ’s title. And reading all sections of all papers—abstract, introduction, results, and/or conclusion—will be extremely time consuming. Furthermore, spending time reading these sections of papers to later find out that it’s not related to your research topic will not help anyone. So, what if there was a tool that could search results beyond keywords using research ideas, questions, etc., and also could summarize the key aspects of each downloaded resource? Definitely something to ponder about.

4. Deciding Which Literature to Select and Cite

Scientists are often overwhelmed with the scholarly research data they find online. It is a never-ending task to decide which literature to select and cite. Thus, it is essential to download only relevant data and assess them based on their relevance to the research topic. Furthermore, citing the literature accurately by following journal-specific guidelines and writing style guides will avoid accidental plagiarism. Such cumbersome tasks can be handled with accuracy using an AI-based tool particularly designed to make academic research and publishing easier.

5. Retrieving Relevant Literature in an Accessible and Editable Format

The inability of some software to save, process, and/or retrieve data in all formats is displeasing in this age of digitization. Hence, scientists prefer software that allows accessing, downloading, managing, and editing research data files in all formats.

How to Find Scholarly Research Data with a Systematic Approach? – 7 simple steps

Given the amount of intelligence on the internet, it is only wise to resort to a reliable system. One which is smart, efficient, precise, accessible, and affordable to integrate the scattered information, help researchers through every step of research reporting and publishing, and save time, effort, and money.

A simple 7-step systematic approach to find relevant scholarly research data

- Search literature based on research ideas, keywords, conference talks, author details, etc.

- Assess the found resources based on their key aspects and findings.

- Search, save, manage, read, and annotate relevant literature on a single platform.

- Use easily accessible and editable formats.

- Cite the literature to avoid plagiarism.

- Follow journal guidelines and format the research paper.

- Connect with co-authors and share your work with them for insights and edits.

An extensive and accurate literature search is the key to performing, reporting, and publishing authentic research. A systematic single-platform search database provides a much better comprehension of insights of the research topic. It helps draw comparisons faster as all results are saved and managed in one place! Moreover, it helps researchers to stimulate the interpretation of ideas, analyze shortcomings, and recognize opportunities of future research.

With advances in technology, this process can be simplified without compromising the quality of the final product. As Artificial Intelligence takes over other realms of society, it’s about time researchers leverage these advances to further streamline research publishing.

What are your ways of literature search? How many databases do you have to use simultaneously? Wouldn’t you want to have all your work on one platform without remembering several login IDs and passwords? This sounds like the future of publishing! What do you think?

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Industry News

- Publishing News

Unified AI Guidelines Crucial as Academic Writing Embraces Generative Tools

As generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools like ChatGPT are advancing at an accelerating pace, their…

- Promoting Research

- Thought Leadership

- Trending Now

How Enago Academy Contributes to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Through Empowering Researchers

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a universal call to action to end…

- AI in Academia

Using AI for Journal Selection — Simplifying your academic publishing journey in the smart way

Strategic journal selection plays a pivotal role in maximizing the impact of one’s scholarly work.…

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Using AI for Plagiarism Prevention and AI-Content Detection in Academic Writing

Watch Now In today’s digital age, where information is readily accessible and content creation…

Authenticating AI-Generated Scholarly Outputs: Practical approaches to take

The rapid advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have given rise to a new era of…

AI for Accuracy in Research and Academic Writing

Upholding Academic Integrity in the Age of AI: Challenges and solutions

AI Assistance in Academia for Searching Credible Scholarly Sources

Call for Responsible Use of Generative AI in Academia: The battle between rising…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and Types

Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and Types

Table of Contents

Research Report

Definition:

Research Report is a written document that presents the results of a research project or study, including the research question, methodology, results, and conclusions, in a clear and objective manner.

The purpose of a research report is to communicate the findings of the research to the intended audience, which could be other researchers, stakeholders, or the general public.

Components of Research Report

Components of Research Report are as follows:

Introduction

The introduction sets the stage for the research report and provides a brief overview of the research question or problem being investigated. It should include a clear statement of the purpose of the study and its significance or relevance to the field of research. It may also provide background information or a literature review to help contextualize the research.

Literature Review

The literature review provides a critical analysis and synthesis of the existing research and scholarship relevant to the research question or problem. It should identify the gaps, inconsistencies, and contradictions in the literature and show how the current study addresses these issues. The literature review also establishes the theoretical framework or conceptual model that guides the research.

Methodology

The methodology section describes the research design, methods, and procedures used to collect and analyze data. It should include information on the sample or participants, data collection instruments, data collection procedures, and data analysis techniques. The methodology should be clear and detailed enough to allow other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the study in a clear and objective manner. It should provide a detailed description of the data and statistics used to answer the research question or test the hypothesis. Tables, graphs, and figures may be included to help visualize the data and illustrate the key findings.

The discussion section interprets the results of the study and explains their significance or relevance to the research question or problem. It should also compare the current findings with those of previous studies and identify the implications for future research or practice. The discussion should be based on the results presented in the previous section and should avoid speculation or unfounded conclusions.

The conclusion summarizes the key findings of the study and restates the main argument or thesis presented in the introduction. It should also provide a brief overview of the contributions of the study to the field of research and the implications for practice or policy.

The references section lists all the sources cited in the research report, following a specific citation style, such as APA or MLA.

The appendices section includes any additional material, such as data tables, figures, or instruments used in the study, that could not be included in the main text due to space limitations.

Types of Research Report

Types of Research Report are as follows:

Thesis is a type of research report. A thesis is a long-form research document that presents the findings and conclusions of an original research study conducted by a student as part of a graduate or postgraduate program. It is typically written by a student pursuing a higher degree, such as a Master’s or Doctoral degree, although it can also be written by researchers or scholars in other fields.

Research Paper

Research paper is a type of research report. A research paper is a document that presents the results of a research study or investigation. Research papers can be written in a variety of fields, including science, social science, humanities, and business. They typically follow a standard format that includes an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion sections.

Technical Report

A technical report is a detailed report that provides information about a specific technical or scientific problem or project. Technical reports are often used in engineering, science, and other technical fields to document research and development work.

Progress Report

A progress report provides an update on the progress of a research project or program over a specific period of time. Progress reports are typically used to communicate the status of a project to stakeholders, funders, or project managers.

Feasibility Report

A feasibility report assesses the feasibility of a proposed project or plan, providing an analysis of the potential risks, benefits, and costs associated with the project. Feasibility reports are often used in business, engineering, and other fields to determine the viability of a project before it is undertaken.

Field Report

A field report documents observations and findings from fieldwork, which is research conducted in the natural environment or setting. Field reports are often used in anthropology, ecology, and other social and natural sciences.

Experimental Report

An experimental report documents the results of a scientific experiment, including the hypothesis, methods, results, and conclusions. Experimental reports are often used in biology, chemistry, and other sciences to communicate the results of laboratory experiments.

Case Study Report

A case study report provides an in-depth analysis of a specific case or situation, often used in psychology, social work, and other fields to document and understand complex cases or phenomena.

Literature Review Report

A literature review report synthesizes and summarizes existing research on a specific topic, providing an overview of the current state of knowledge on the subject. Literature review reports are often used in social sciences, education, and other fields to identify gaps in the literature and guide future research.

Research Report Example

Following is a Research Report Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Academic Performance among High School Students

This study aims to investigate the relationship between social media use and academic performance among high school students. The study utilized a quantitative research design, which involved a survey questionnaire administered to a sample of 200 high school students. The findings indicate that there is a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance, suggesting that excessive social media use can lead to poor academic performance among high school students. The results of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers, as they highlight the need for strategies that can help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities.

Introduction:

Social media has become an integral part of the lives of high school students. With the widespread use of social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat, students can connect with friends, share photos and videos, and engage in discussions on a range of topics. While social media offers many benefits, concerns have been raised about its impact on academic performance. Many studies have found a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance among high school students (Kirschner & Karpinski, 2010; Paul, Baker, & Cochran, 2012).

Given the growing importance of social media in the lives of high school students, it is important to investigate its impact on academic performance. This study aims to address this gap by examining the relationship between social media use and academic performance among high school students.

Methodology:

The study utilized a quantitative research design, which involved a survey questionnaire administered to a sample of 200 high school students. The questionnaire was developed based on previous studies and was designed to measure the frequency and duration of social media use, as well as academic performance.

The participants were selected using a convenience sampling technique, and the survey questionnaire was distributed in the classroom during regular school hours. The data collected were analyzed using descriptive statistics and correlation analysis.

The findings indicate that the majority of high school students use social media platforms on a daily basis, with Facebook being the most popular platform. The results also show a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance, suggesting that excessive social media use can lead to poor academic performance among high school students.

Discussion:

The results of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers. The negative correlation between social media use and academic performance suggests that strategies should be put in place to help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities. For example, educators could incorporate social media into their teaching strategies to engage students and enhance learning. Parents could limit their children’s social media use and encourage them to prioritize their academic responsibilities. Policymakers could develop guidelines and policies to regulate social media use among high school students.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, this study provides evidence of the negative impact of social media on academic performance among high school students. The findings highlight the need for strategies that can help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities. Further research is needed to explore the specific mechanisms by which social media use affects academic performance and to develop effective strategies for addressing this issue.

Limitations:

One limitation of this study is the use of convenience sampling, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Future studies should use random sampling techniques to increase the representativeness of the sample. Another limitation is the use of self-reported measures, which may be subject to social desirability bias. Future studies could use objective measures of social media use and academic performance, such as tracking software and school records.

Implications:

The findings of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers. Educators could incorporate social media into their teaching strategies to engage students and enhance learning. For example, teachers could use social media platforms to share relevant educational resources and facilitate online discussions. Parents could limit their children’s social media use and encourage them to prioritize their academic responsibilities. They could also engage in open communication with their children to understand their social media use and its impact on their academic performance. Policymakers could develop guidelines and policies to regulate social media use among high school students. For example, schools could implement social media policies that restrict access during class time and encourage responsible use.

References:

- Kirschner, P. A., & Karpinski, A. C. (2010). Facebook® and academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1237-1245.

- Paul, J. A., Baker, H. M., & Cochran, J. D. (2012). Effect of online social networking on student academic performance. Journal of the Research Center for Educational Technology, 8(1), 1-19.

- Pantic, I. (2014). Online social networking and mental health. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(10), 652-657.

- Rosen, L. D., Carrier, L. M., & Cheever, N. A. (2013). Facebook and texting made me do it: Media-induced task-switching while studying. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 948-958.

Note*: Above mention, Example is just a sample for the students’ guide. Do not directly copy and paste as your College or University assignment. Kindly do some research and Write your own.

Applications of Research Report

Research reports have many applications, including: