Advertisement

Sustainable Tourism as a Driving force of the Tourism Industry in a Post-Covid-19 Scenario

- Original Research

- Published: 12 June 2021

- Volume 158 , pages 991–1011, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Beatriz Palacios-Florencio ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2789-7914 1 ,

- Luna Santos-Roldán 2 ,

- Juan Manuel Berbel-Pineda 1 &

- Ana María Castillo-Canalejo 2

17k Accesses

41 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The tourism industry is probably one of the most affected by the crisis caused by Covid-19. It is the responsibility of politicians, tourism professionals and researchers to look for solutions to revive this important industry. This article shows how the development of Sustainable Tourism can help in the sustenance of the tourism industry, since one of the premises on which Sustainable Tourism is based is the non-overcrowding of tourist destinations (essential factor in the current context). Considering this argument and the existing regulations on lockdown rules, social distancing and meet up, it is considered that the practices in Sustainable Tourism can become a potential solution to stimulate tourist movements and help the revival of the tourism industry. Therefore, more specifically, the main objective of this article is to know tourist´s perception among about Sustainable Tourism and to determine which factors help its development. In this sense, the use of structural equation models in a research of 308 tourists has determined how factors related to the tourists’ attitude, motivation and perceived benefits provided by the development of Sustainable Tourism increase the intention to consume this type of tourism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Sustainable Tourism in Europe from Tourists’ Perspectives

Sustainable Tourism and Degrowth: Searching for a Path to Societal Well-Being

Sustainable Tourism; Vector of the Social and Solidarity Economy: Case of Region Souss Massa, South of Morocco

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It is widely accepted that one of the aspects considered by Sustainable Tourism is the fight against overcrowding in certain tourist destinations and avoid damages associated (eg. Jurowski & Gursoy, 2004 ; Santana-Jiménez & Hernández, 2011 ). In fact, Sustainable Tourism has been trying (for years) to place itself as a solution to the negative aspects that involve tourism in its development and to the criticism it frequently receives (Sharpley, 2020 ). And it is now, in this context, that this perception makes more sense than ever before.

The massification of tourist destinations and the damage this causes (both in cities and to natural environments), is one of the fiercest criticisms levelled at tourism. In this sense, Sustainable Tourism is based, among other things, on promoting and developing less massified tourist destinations or Sustainable Mass Tourism as the desired impending outcome for most destinations. In relation to this, the research of Weaver ( 2012 ) highlights the concept of Sustainable Mass Tourism as an emerging tourism state—something that can be convenient reconsidered in the current situation-. According to this author, this type of tourism is perceived as a desired outcome for destinations with a focus on sustainability and indicates three convergent developmental trajectories: organic, incremental and induced.

On the other hand, we would like to point out that, among the measures being taken to combat Covid-19, restrictions on meetings and social distancing measures stand out (World Health Organization, 2020 ). And, why are these measures being referred to here? The explanation is simple, as this paper takes as the basis the fight against overcrowding in tourist destinations; relating it to the measures adopted (nearly worldwide), due to the social distancing caused by Covid-19. In fact, this measure, together with the tourist's perception of fear of travelling, are the ingredients for preventing overcrowded destinations, and therefore strenght Sutainable Tourism.

Therefore, it can be stated that tourism industry is highly sensitive to significant shocks like the Covid-19 pandemic (Chang et al., 2020 ). In other words, tourism is particularly susceptible to measures to counter pandemics due to restricted mobility and social distancing. This leads to global travel restrictions (which are unprecedented) that, together with confinement, are causing the most severe disruption to the global economy in recent decades (Gössling et al., 2020 ). According to the declarations made by the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) on its website, on April, 96% of worldwide destinations have implemented travel restrictions. Around 40 destinations are experiencing a partial border closure, while 90 destinations have closed totally their borders. An unforeseen and, for the time being, unpredictable situation that urges survival measures for the sector.

Given this current scenario, Sustainable Tourism may find a great opportunity for its development (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020 ; Petrizzo, 2020 ). Indeed, this article focuses primarily on determining factors focuses on the tourist's perception for promoting Sustainable Tourism.

The UNWTO defined in 2005 the concept of Sustainable Tourism as “ one whose practices and principles can be applicable to all forms of tourism in all types of destinations, including mass tourism and the various niche tourism segments ”. Sustainability principles refer to the environmental, economic, and socio-cultural aspects of tourism development, and a suitable balance must be established between these three dimensions to guarantee its long-term sustainability (UNWTO, 2005 ). In addition to international organizations, we also find many authors who have defined the concept of Sustainable Tourism (Higgins-Desbiolles et al., 2019 ; Hussain, et al., 2015 ; Mohaidin, et al., 2017 ). Conversely, despite the fact that Sustainable Tourism has been recognized in business practice in many destinations, the volume of academic research has not been as large as it deserves (Ruhanen et al., 2015 ). From the start, the development of Sustainable Tourism is based on the preservation of the environment (Ciacci et al., 2021 ), the cultural authenticity and the democratic profitability of the tourist activity in destination (Crosby, 1996 ). It is only this tourism that recognizes the priority place of social return, as an index of well-being reversed on the visited destination; and also the exclusively economic return, that is, whether the tourist activity generates sufficient income for the local population, in terms of employment, wealth and available resources (Fernández, 2018 ).

The purpose of this study is to identify the factors that help the development of Sustainable Tourism (from a tourist's perception point of view), since a greater use of this type of tourism could help the revival of the tourism industry. In this sense, and considering the guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO), the different governments in all countries recommend avoiding large concentrations of people (which favors the development of this type of tourism).

However, in generic terms, tourism implies people concentration, and even more so in those destinations considered as “overcrowded”: large cities, charming cities, main beach locations, amusement parks, airports, etc. That is why, under the conditions exposed, it is necessary to combat the social, economic, financial and cultural consequences of a pandemic, which entails a challenge for the tourism sector, that requires a careful assessment of its impact dimensions, as well as a reconsideration of a new hitherto unknown approach. Thus, the development of tourism as it is currently known will change in the coming years, which will have serious repercussions on the profitability of tourism industry (Hancock, 2020 ).

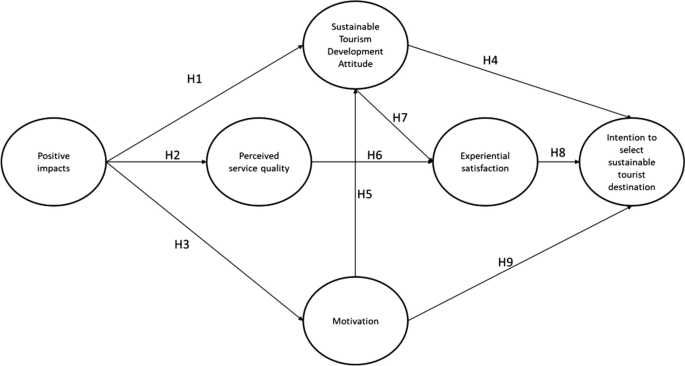

Henceforth, this study gives an assessment of Sustainable Tourism and the variables that enable accelerated development (which becomes more necessary in this crisis context in tourism industry). The theoretical frame study analyzes the factors of perceived quality, motivation, attitude, and satisfaction as attributes with a potential influence on the intention of choosing this kind of tourism. Consequently, the study is based on literature focused on consumer behavior based on their perception. However, the main contribution of this study is not theoretical (since there is a lot of literature based on this approach). The main contribution lies in extracting all the positive aspects that sustainable tourism brings to tourism development and highlighting its value in these times of crisis that this industry is going through.

2 Theorical Background

2.1 the relation between positive impacts and the attitude towards the development of sustainable tourism, the perception of service quality and motivation.

Most research conclude that the three basic categories of benefits and costs that affect to a community which receives tourists are economic, environmental, and social (Chi-Ming et al., 2017 ; Gee et al., 1989 ; Gunn, 1988 ; Gursoy et al., 2000 ; Gursoy et al., 2002 ; Murphy, 1985 ; Nunkoo & So, 2015 ; Palacios-Florencio et al., 2018 ; Vargas, 2007 ).

The economic benefits of tourism development are usually translated into employment opportunities (Belisle & Hoy, 1980 ; Davis et al., 1988 ; Ritchie, 1988 ; Tyrrell and Spaulding, 1984 ; Tosum, 2002 ; Var et al., 1985 ), income derivatives of the tourism sector (Davies et al., 1988 ; Lankford, 1994 ; Jurowski et al., 1997 ; Murphy, 1983 ; Tyrrel and Spaulding, 1984 ) and investment and business opportunities (Davis et al., 1988 ; Sethna & Richmond, 1978 ).

Regarding the social impact of tourism, it can be conceived as changes in the people lives residing in the communities that are part of the destination and related to tourism activity (Mathieson & Wall, 1982 ). Likewise, the social and cultural benefits (Besculides et al., 2002 ) translate into an increase in leisure activities (Keogh, 1990 ; Liu et al., 1987 ; Murphy, 1983 ; Pizam, 1978 ; Rothman, 1978 ; Sheldom and Var, 1984 ), the improvement of public services and infrastructures (Pizam, 1978 ; Sethna & Richmond, 1978 ) and the instigating effect on social change (Harrison, 1992 ). Between its benefits, tourism increases cultural identity and pride, the cohesion and the exchange of ideas, improves knowledge of the area culture (Esman, 1984 ), creates opportunities for cultural exchange, revitalizes local traditions, increases the quality of life and improves the image of the community (Besculides et al., 2002 ).

Similarly, in the environmental field, tourism may be the reason to protect natural resources and conserve homogeneous urban designs (Díaz & Gutiérrez, 2010 ), so that it can be possible to promote an ordered tourist development based on a model integrated in the environment. Miller et al., ( 2014 ) refer to the concept of pro-environmental behaviour, understood as the actions for protecting the environment, while tourists´ pro-environmental behaviour were connected to nature-based tourism and ecotourism. Ciacci et al., ( 2021 ) adds to the environmental factor, logistical and infrastructural dimension. While it is true that environmental quality can be composed by objective and subjective components, it has been widely accepted that a good link between environmental protection, logistic and infrastructural development is seen as fundamental for a successful Sustainable Tourism development strategy.

The notion of sustainable development is a relatively recent concept, first defined in 1987 in the Brundtland report by the UN. This report, also called “Our Common Future”, declares that sustainable development tries to “meet the needs of the present generation without the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (CMMAD, 1992 : 67).

Following the arrival of the concept of sustainable development in 1987 with the aforementioned Brundtland report, it was applied to the tourism field.

This type of tourism weights the importance of stakeholders and, although the key role of residents is recognized (Gursoy et al., 2018 ; Stylidis et al., 2014 ), it is also interesting to analyze the perspective of the tourists themselves. Indeed, knowing the attitudes of tourists towards the development of Sustainable Tourism and raising culture, environment and economy awareness of the communities visited are vital factors to protect tourist destinations and reduce negative impacts (Othman et al., 2010 ).

On the other hand, most studies report a positive relation between the attitude towards Sustainable Tourism development and the perception of its positive impacts (Andereck & Vogt, 2000 ; Byrd et al., 2009 ; Chi-Ming et al., 2017 ; Ekanayake & Long, 2012 ; Hussain, et al., 2015 ; Pavlić et al., 2017 ; Su & Chang, 2017 ). The provision of high quality and environmentally friendly services has been identified as an important factor for the success of a tourist destination (Miller et al., 2014 ).

Service quality is defined as the level of satisfaction an event or experience produces according to individual needs or expectations (Michael, 2013 ). Mukhles ( 2013 ) proposes five main components to analyze the quality of the tourist service: attractions and neighborhoods, facilities and services, accessibility, destination image, and pricing. The attractions and neighborhoods of the destination are elements that largely determine the choice of tourists and motivate the visit to this destination, include both natural and artificial attractions. The facilities and services include accommodation, restaurants, transportation, sports or other activities and tourist sale points. Accessibility includes elements related to transport and its infrastructure. The destination image is the subjective interpretation of reality by the tourist and, the fifth component, the price enables to measure the quality of the different services. On the other hand, Mohaidin et al. ( 2017 ) considers other attributes that should be taken into account: the environment safety and harmony and the ability to perform the promised service in a reliable and accurate way. Hence, the following model hypotheses are raised:

Tourism motivation is a driving force that motivates people to go on holiday or visit destinations. Beerli and Martin ( 2004 ) describe the motivation to travel as an internal need that drives an individual to act in a certain way to achieve his desired satisfaction. Yoon and Uysal ( 2005 ) found that motivation is the most important factor that increases satisfaction together with the services and the loyalty to a destination. In addition to being the most important factor in predicting tourism behavior, motivation to travel also significantly influences the understanding of the intentions of tourist visits (Li et al., 2010 ; Mohaidin, et al., 2017 ).

The motivation to travel to a destination will be higher whether the tourist is aware of the positive impacts that Sustainable Tourism can have on there (Crouch & Ritchie, 1999 ). From this information, the following hypothesis of this study is proposed:

2.2 The Relation Between the Attitude Towards the Development of Sustainable Tourism and the Intention to Choose a Sustainable Tourist Destination

Intention can be defined as a stated probability of engaging in a certain behavior (Oliver, 1997 ). Efforts to recognize and attract the right visitors are crucial in ensuring Sustainable Tourism. Behavioral intentions represent a vital issue in the field of tourism, since it is necessary to know and understand the tourist loyalty, i.e. the factors that influence positive intentions towards a destination (Mohaidin et al., 2017 ).

Ventakesh ( 2006 ) and Mohaidin, et al. ( 2017 ) point out that, among the psychological factors that affect tourists in their intention to select a sustainable tourist destination, a respectful attitude towards the environment has a positive effect. Luo and Deng ( 2008 ) verifies that people who show positive attitudes towards the environment during trips can transmit a greater desire for Sustainable Tourism experiences with nature.

Miller, et al. ( 2014 ) indicate that are several types of variables that are associated with pro-environmental behavior in the context of large mass tourism urban destinations, including individual background factors, habit, attitudes and external contextual factors. This study suggests that psychological factors such as attitudes may be more important than socio-demographic and contextual factors in determining pro-environmental behaviour in sustainable urban tourism destination.

From these statements, the following hypothesis is interpreted:

2.3 The Relation Between Motivation and Attitude Towards the Development of Sustainable Tourism

Along with satisfaction, knowing the motivations of tourists is the basis for understanding the following behavior trends (Jensen, 2015 ; Xu and Chan, 2016 ). For Wong et al. ( 2017 ), it is a two-phase process where internal and external factors converge. In this sense, the internal factors concern the desire to make the trip. Kim et al. ( 2007 ) incorporates psychological reasons such as disconnection and relaxation. For their part, external factors promote the destination choice, including cultural and unique features of the destination (Pesonen et al., 2011 ).

The tourist motivation has positive effects on their visit intention, as the commitment to the environment, nature care and conservation in the case of Sustainable Tourism development (Hunter, 2000 ). Huang and Liu ( 2017 ) apply these constructs to ecotourism to confirm that greater environment sensitivity of tourists is related to the motivation and the intention to repeat the visit. Similarly, Zhang and Lei ( 2012 ) argue that environmental knowledge and concern are directly related to the motivation and intention of a tourist visit.

2.4 The Relation Between the Perception of Service Quality and Satisfactory Experience

Understanding what factors influence tourist satisfaction is one of the most relevant research topics in the tourism sector, due to the impact it has on the success of any tourism product or service. The perceived quality is a measure that represents the quality obtained from product or service attributes and is related to the satisfaction of the customer’s needs and the product or service availability (ACSI, 2016 ).

It is widely recognized in the literature that the service quality perceived by the customer directly influences the tourist experience satisfaction (Castillo Canalejo & Jimber del Río, 2018 ; Hui et al., 2007; Mohaidin et al., 2017 ; Wu et al., 2016 ). Therefore, the following model hypothesis is formulated:

2.5 The Relation Between the Attitude Towards the Development of Sustainable Tourism and Satisfactory Experience

Experimental satisfaction goes beyond the concept of service satisfaction, taking into account it focuses on customers’ evaluations regarding their experiences once such service has been consumed (Wu et al., 2016 ). If this is applied to sustainable development in the aforementioned Brutland Report, the concept of satisfaction becomes vitally relevant. The development of Sustainable Tourism must satisfy the needs of tourists and residents at the same time that economic, socio-cultural and environmental need (UNWTO, 2005 ).

In the scientific literature, some authors (Chang & Fong, 2010 ; Kao et al., 2008 ; Wu et al., 2016 ) allude to green experiential satisfaction to refer to the clients’ general evaluations regarding their experience with respectful aspects of the environment and its expectations on the sustainable development of tourist destinations or services. From the study of these authors, the following hypothesis is based:

2.6 The Relation Between Satisfactory Experience and Intention to Choose a Sustainable Tourist Destination

Another widely recognized factor in the scientific literature that influences the intention to visit a place is satisfaction. According to Oliver ( 1980 ), it is considered as the balance of expectations and perceptions before and after the visit to a destination, whose importance lies in the ability to influence future behavior (Ohn & Supinit, 2016 ; Choo et al., 2016 ). In tourism studies, the satisfaction produced by the experience of tourist activities is especially important, as these are the most memorable and are conceived as a differentiating element from other visits (Walls et al., 2011 ).

There are numerous studies that prove the relation between tourist satisfaction and the intention of returning (Baker & Crompton, 2000 ; Beecho and Prentice 1997 ; Castillo Canalejo & Jimber del Río, 2018 ; Caneed, 2003 ; Dimitriades, 2006 ; Hallowell, 1996 ; Pizam, 1994 ; Sung, et al., 2016 ). Other authors, such as Jurdana and Frleta ( 2012 ) or Chin et al. ( 2018 ), focus on a specific type of tourism: rural tourism. From the reading of these authors, the following hypothesis is proposed:

2.7 The Relation Between Motivation and Intention to Choose a Sustainable Tourist Destination

Motivation is an individual internal factor that can affect the tourist behavior by influencing their trip valuation. This construct can be considered as a key factor in the process of selecting tourist destinations and the intention to visit (Chang et al., 2014 ; Hsu and Huang 2009 ).

In the bibliography, we find several examples of authors that demonstrate that motivation and satisfaction influence the tourist’s decision when choosing a destination (Chiu et al., 2016 ; Yoon & Uysal, 2005 ). In this sense, the study of Malaysia of Mohaidin et al. ( 2017 ) confirms that motivation positively influences the intention to choose a sustainable tourist destination, in line with the results offered by Beerli and Martin ( 2004 ), and Prebensen ( 2006 ). Based on this, the last hypothesis is proposed:

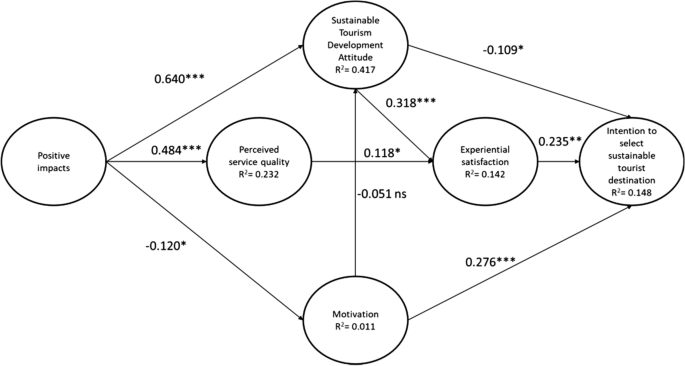

In summary, hereunder the conceptual model to be studied is shown in Fig. 1

Conceptual mode. Source Own elaboration

3 Data and Methodology

The data was collected from tourists who visited the city of Córdoba (Spain) between the months of October and November 2019. Córdoba (a World Heritage city) is one of the main cities receiving tourism (both national and international). This means that one of the main challenges that it faces is massification and the problems associated (Weaver, 2012 ). The sample included a total of 308 tourists, who received the questionnaires personally and on-site in the monumental area of the city. The questionnaires were handed out randomly to people visiting the monumental area, after requesting their collaboration and verifying that they were tourists and not simple passers-by. Despite its possible limitations, we considered this procedure to be the most appropriate for the objectives of this research. So, we have used a non-probabilistic sampling.

In relation to the instruments used, the original versions of the scales were translated with special attention into the linguistic characteristics of the population. All variables were measured on a Likert scale from 1 to 5. Where 1 = totally disagree and 5 = totally agree. The items in the questionnaire were translated and adapted for the different constructs. The items of positive socio-cultural, economic and environmental impacts were extracted and adapted from Pavlić et al. ( 2017 ), the items related to experiential satisfaction were obtained from the research carried out by Wu & Li ( 2015 ), the items of Sustainable Tourism Development Attitude were adapted from the study of Wei-San Su et al. ( 2017 ), and the constructs of “perceived service quality, intention to select sustainable tourist destination and motivation” were extracted and adapted from Mohaidin et al. ( 2017 ).

Table 1 shows the main aspects related to the respondents’ profile. It has to be emphasized that a relative equality is observed regarding the origin of the tourists surveyed. In general, these are tourists who come on holiday, own financing and, in a high percentage of cases, basing on their own decision. More than 60% of the travelers are 35 years old or more, have a stable partner (married and living as a couple), live in households based on 2 or more people and earn a monthly income of between 1000 and 2000 euros. Although the majority of the respondents stated that they were visiting this city for the first time (62.7%), a high percentage (close to 40%) repeated their destination. On average, the tourists who participated in the study stayed in the city for 2–3 days.

For the analysis of relations between the variables of the proposed model, structural equation modeling has been used, more specifically the Partial Least Squares (PLS) technique, based on variance (Roldán and Sánchez-Franco, 2012 ). We have specifically chosen this technique for the following reasons (Cepeda-Carrion and Roldan, 2004 ): (a) the better suitability of the technique for research in the social sciences (economics, business organization, marketing, etc.); (b) the absence of strict requirements on the distribution of the data; and (c) the possibility of using composite variables. The measurement model used in this study is composite and reflective (Mode A). This makes the use of traditional PLS viable (Sarstedt et al., 2016 ). We have used PLS SmartPLS 3.2.8 software (Ringle et al., 2015 ).

The use of a single questionnaire in a self-report format to obtain the data of the latent variables made it necessary to verify the existence of common variance between them. All the experts’ suggestions (Huber and Power, 1985 ; Podsakoff et al., 2003 ) on the procedural steps regarding the design of questionnaires have been followed. The different measures used were separated and, on the other hand, the anonymity of the respondents was guaranteed. The Harman test (1967) has been used to detect the existence of common influence in the responses. The results of the exploratory factor analysis show that the 40 elements of the questionnaire are grouped into a total of 12 factors, where the largest of them explains 17% of the variance. This allows us to confirm the absence of a common factor of influence between these items (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986).

The latent model perspective (MacKenzie & Royle, 2005 ; Real et al., 2006 ) was used when analyzing the relations between the different constructs of the model and its factors. And, as in any model of structural equations, both the measurement model and the structural model were validated (See table A in the appendix that includes the correlation matrix between the items of the model).

4 Results and Discussion

4.1 measurement model.

Table 2 collects both the mean and standard deviation of each element and the data necessary to begin with the validation of the measurement model: determine the reliability of the individual items. We have measured all latent variables (constructs) in mode A (reflective). It is observed that the factor loads of most of the items exceed the minimum criterion of 0.707 (Carmines and Zeller, 1979), only two elements with lower values have been maintained, although very close (0.68). These items have been taking into account after checking their level of significance via bootstrapping (5000 subsamples) and according to the suggestions made by Hair et al. ( 2017 ). 25 items of a total of 40 were removed from the original questionnaire.

The reliability of the constructs was evaluated using the composite reliability index (ρ c ) (Werts et al., 1974 ). In all cases, we observe the fulfillment of the minimum requirement: a composite reliability greater than 0.7 (Nunnally, 1978 ). Regarding convergent validity, as Table 1 illustrates, all latent variables exceed the minimum level of 0.5 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981 ) in the AVE.

The analysis of the discriminant validity of the various constructs (latent variables) has been performed based on the Fornell-Larcker criterion. The data is collected in Table 3 . The Fornell-Larcker criterion is strictly followed in all cases. This allows us to affirm the discriminant validity between the latent variables and their way of measuring them.

After validating the measurement model, the structural model can be validated.

4.2 Structural Model

Following the indications of Roldán and Cepeda ( 2018 ), the study of the structural model must begin with the analysis of the sign, size and significance of the path coefficients, the R 2 values and the Q 2 test. According to Hair et al. ( 2017 ), we have used the bootstrapping technique with 5000 samples, to determine the t statistics and the confidence intervals and, in this way, obtain the significance of the relations. Table 4 offers the direct effects (path coefficients), the value of the t statistic, the corresponding confidence intervals and the verification of proposed hypotheses validity, along with the values of R 2 and Q 2 .

Not all direct effects are significant and positive and, therefore, the data do not indicate a widespread validity for the hypotheses proposed. 2 relations of a total of 3 are significant, but with an opposite sign to proposed one: the effect of the attitude towards the development of Sustainable Tourism on the intention to choose is negative, the same as the positive impact on the tourist motivation. Another invalid hypothesis regarding the effect of the attitude towards Sustainable Tourism on the tourist motivation is also contrary to the proposed one; although, in this case, it has no statistical significance.

The R 2 values only offer an appropriate predictive level for the variable attitude towards Sustainable Tourism development and a moderate level for the perceived service quality. The final variable intention to choose a sustainable tourist destination does not reach significant predictive levels. Besides, the Q 2 values indicate a certain level of predictive relevance of the model, since they all are greater than 0, although some of them are quite low.

In our model, we have also intended to verify whether there are mediation relations concerning the various endogenous variables included in the model. The results on mediation appear in Table 5 , where the values of all the indirect effects presented in the model are collected. The results indicate the presence of significant and positive indirect effects in total only in the case of the following relations: between the effect of the attitude towards the development of Sustainable Tourism and the intention to select a sustainable tourist destination, and between global positive impacts and the attitude towards the development of Sustainable Tourism. The model and its results are presented graphically in Fig. 2 .

Structural model: results and relations. Source Own elaboration

Once the reliability of the different items and the validity of the proposed models have been verified, we observe an absence of unanimity in the confirmation of the hypotheses proposed. Thus, in this case, the results do not match with the statements provided by some authors such as Crouch and Ritchie ( 1999 ), Lit et al. (2010) or Mohaidin et al. ( 2017 ), who confirm that the positive impacts provided by Sustainable Tourism could be a motivation for the destination. Similarly, nor does the study confirm that favorable attitudes towards the development of Sustainable Tourism positively influence on the intention to select sustainable tourist destinations, as authors such as Ventakesh ( 2006 ) or Mohaidin et al. ( 2017 ) concluded in their studys. On the other hand, although numerous studies consider the tourist motivation as a driver of their future behavior and as a positive effect trigger on the intention of visiting certain destinations, in addition to as a favorable attitude related to development of Sustainable Tourism (e.g. Huang & Liu, 2017 ), these theories are not also confirmed in this case.

The rest of the hypotheses raised in this study, related to perceived service quality, satisfaction or intention to choose sustainable tourist destinations, provide results that confirm previous studies on this topic and the relations proposed in this study.

5 Conclusions, Limitations and Future Research

5.1 conclusions.

Sustainable Tourism can become a solution to the crisis caused by COVID-19. This type of tourism promotes “greener” destinations, conceiving this term not only as ecological, but also as healthy. Therefore, the current mass many of the main tourist destinations face up today seems to stop happening soon or have to evolute to a sustainable mass tourism that combines the emergence of sustainability as a societal norm with the entrenched norm of support for growth (Weaver, 2012 ).

The different governments on spaces for coexistence not because of a greater environmental awareness instilled in tourists, but because of the obligations impose this fact and, on the other hand, because of the new requirements in terms of security tourists will impose on themselves when traveling and choosing a destination. Curiously, this crisis is going to force a change in Sustainable Tourism this summer 2020 in Spain. Once the confinement is finished, only internal tourism will be able to be developed. This adaptation will help overcome old problems: the exclusivity of “sun and sand” tourism will be faced to the fear of crowds, so that the occupation of inland destinations will increase, revitalizing unpopulated areas.

Therefore, the COVID-19 crisis should indirectly boost the long-awaited Sustainable Tourism, so necessary for environmental conservation and recovery. This type of tourism will finally have the long-expected opportunity (Petrizzo, 2020 ). This is the perfect time of the positioning of a sustainable Spanish tourism brand focused on its pre-existing competitive advantages. Furthermore, although the intention of many previous studies was demonstrating the importance of Sustainable Tourism (e. g. Chi-Ming et al., 2017 ; Ekanayake & Long, 2012 ; Fernández, 2018 ; Hussain, et al., 2015 ; Mohaidin et al., 2017 ; Vargas, 2007 ; Pavlić et al., 2017 ; Su & Chang, 2017 ), it does not succeed in establishing firmly in the tourist motivation, as this study reflects. However, the study confirms that tourists consider the Sustainable Tourism positive factors as important and manifest a favorable attitude towards its develop, particularly in the intention of selecting this destination type.

Based on the structural model proposed in this article and the results provided by its analysis, we see how the intention to select sustainable touristic destinations is supported by motivation (H9) and by the tourists’ satisfaction of developing favorable attitudes towards Sustainable Tourism (H8). Likewise, a positive and significant relationship of the tourist’s attitude towards the development of Sustainable Tourism is observed, fostered by the generic positive impact that it entails (H1). Respect to the tourist’ satisfaction experienced when consuming Sustainable Tourism, this is generated by the tourist’ attitude to develop Sustainable Tourism (H7) and by the service quality perceived on it (H6). This perceived service quality is caused by the generic positive impacts resulting from the development of Sustainable Tourism (H2). The rest of the relations established in the model (H3, H4 and H5) do not find statistical support in the results obtained.

Delving into the current approach of the Spanish tourism industry, the prospects noticed are dramatic, since this industry has a vital importance in the country, becoming the main axis of the national economic strength. Therefore, tourism experts and academics have the duty of find solutions to the crisis caused by the coronavirus. For this reason, we consider that promoting less crowded destinations and, ultimately, fostering Sustainable Tourism may be one of the solutions to this unprecedented crisis.

In summary, Sustainable Tourism can build on the momentum provided by this context of health crisis to increase a favorable attitude towards Sustainable Tourism development. Achieving this attitude will allow an increase in the tourist´s awareness, translated as the tourist´s perception of the positive impact and the satisfaction experienced with the consumption of this tourism type. The contributions that this work provides are several. In general, it highlights the convenience for Sustainable Tourism at present. It summarizes the constructs involved in the tourist's perception of Sustainable Tourism, contrary to other research focused on certain types of Sustainable Tourism. Specifically, our research model covers a total of 9 hypothesis with a new combination of constructs, in comparison to other publications with the same topic.

Public Institutions, in addition to managing the restrictions in the different territories, should also have the responsibility of developing policies for saving the tourism sector from the current crisis. Since Sustainable Tourism (as analyzed here) can help to promote tourist movements, it is the responsibility of Public Institutions to promote them. Therefore, it is important to determine the factors motivating tourists to engage in Sustainable Tourism, so that Public Institutions can also encourage its development, carrying out policies focused on the promotion and encouragement of this type of tourism.

The main contribution of this study is not theoretical (since there is a lot of literature based on this approach). The main contribution lies in extracting all the positive aspects that sustainable tourism brings to tourism development and highlighting its value in these times of crisis that this industry is going through.

5.2 Limitations

However, the main limitation we find in the present study is that the study was carried out prior to the crisis caused by COVID-19, therefore, aspects such as changes in attitudes, motivations and perceptions related to and caused by this new situation were not considered at any time. However, the study focused on analyzing the importance of Sustainable Tourism from a tourist perception approach. Without doubt, this relevance will be driven by this new situation. The second limitation derives from the non-probabilistic character of the sample, as the results obtained cannot be generalized; they do not guarantee a representation of the whole population, so that, it can be accepted a level of subjectivity.

In short, it is necessary to find formulas that boost the tourism industry. The development of Sustainable Tourism can help to mitigate the tourists’ perceived fear of visiting destinations with a large concentration of people. Therefore, can this crisis be the last great opportunity for the development of Sustainable Tourism?

5.3 Future Research

It would be very convenient to replicate this study in the future, when total mobility within the national territory begins to be allowed and the circulation of tourists is allowed internationally. Thus, for example, an aspect that was not supported in the present study is the importance of positive impacts a destination could have did not suppose a motivation for its choice. Thanks to the different government campaigns that are being recently launched with the aim of achieving positive impacts from visiting certain destinations, we think that this aspect could change due to the increased sensitivity perceived by the tourist.

ACSI (2016). www.theacsi.org/about-acsi/the-science-of-customer-satisfaction , last accessed (23/02/2017).

Andereck, K. L., & Vogt, C. A. (2000). The relationship between residents´attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options. Journal of Travel Research., 39 (1), 27–36.

Google Scholar

Baker, D. A., & Crompton, J. L. (2000). Quality satisfaction and behaviour intention. Annals of Tourism Research., 27 (3), 785–804.

Beeho, A. J., & Prentice, R. (1997). Conceptualizing the experiences of heritage tourists: a case study of new Lanark world heritage village. Tourism Management., 18 (2), 75–87.

Beerli, A., & Martin, J. D. (2004). Factors influencing destination image. Annals of Tourism Research., 31 (5), 657–681.

Belisle, F. J., & Hoy, D. R. (1980). The perceived impact of tourism by residents: a case study in Santa Marta. Columbia. Annals of Tourism Research., 7 , 83–101.

Besculides, A., Lee, M., & McCormick, P. (2002). Residents’ perceptions of the cultural benefits of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 29 , 303–319.

Byrd, E., Cardenan, D., & Dregallas, S. (2009). Differences in stakeholder attitudes of tourism development and the natural environment. E-Review of Tourism Research., 7 (2), 72–81.

Caneen, J. M. (2003). Cultural determinants of tourism intention to return. Tourism Analysis., 8 , 237–242.

Castillo Canalejo, A.M., & Jimber del Río, J.A., (2018). Quality, satisfaction and loyalty índices. Journal of Place Management and Development .

Chang, C. L., McAleer, M., & Ramos, V. (2020). A charter for sustainable tourism after COVID-19. Sustainability, 12 , 3671.

Chang, N. J., & Fong, C. M. (2010). Green product quality, green corporate image, green customer satisfaction and green customer loyalty. African Journal of Business Management., 4 (13), 2836–2844.

Chang, K.-C., Kuo, N. T., Hsu, C. L., & Cheng, Y.-S. (2014). The impact of website quality and perceived trust on customer purchase intention in the hotel sector: Website brand and perceived value as moderators. International Journal of Innovation, Management and Technology , 5 , 255–260.

Chien, C., Law, F., Lo, M., & Ramayah, T. (2018). The impact of accessibility quality and accommodation quality on tourists’ satisfaction and revisit intention to rural tourism destination in sarawak: the moderating role of local communities’ attitude. Global Business and Management Research., 10 (2), 115–127.

Chiu, W., Zeng, S., & Cheng, P. (2016). The influence of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: a case study of Chinese tourists in Korea. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research., 10 (2), 223–234.

Chi-Ming, H., Chang, H., & Sung Hee, P. A. (2017). study of two stakeholders’ attitudes toward sustainable tourism development: A comparison model of Penghu Island in Taiwan. Pacific Journal Business Research , 8 , 2–28.

Ciacci, A., Ivaldi, E., Mangano, S., & Ugolini, G. (2021). Environment, logistics and infrastructure: the three spheres of influence of Italian coastal tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism . https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1876715

Article Google Scholar

ComiSión Mundial Del Medio Ambiente Y Del Desarrollo (CMMAD) (1992): Nuestro futuro común, Madrid, Alianza Editorial.

Cotrell, S., Duim, R., Ankersmid, P., & Kelder, L. (2004). Measuring the sustainability of tourism in manuel antonio and texel: a tourist perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism., 12 (5), 409–431.

Crosby, A. (1996). Elementos básicos para un Turismo Sostenible en las áreas naturales . Centro Europeo de Formación Ambiental y Turística.

Crouch, G. I., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (1999). Tourism competitiveness, and societal prosperity. Journal of Business Research., 44 , 137–152.

Davis, D., Allen, J., & Cosenza, R. M. (1988). Segmenting local residents by their attitudes, interests, and opinions toward tourism. Journal of Travel Research., 27 , 2–8.

Díaz, R., & Gutiérrez, D. (2010). La actitud del residente en el destino turístico de Tenerife: Evaluación y tendencia. PASOS, Revista De Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 8 (4), 431–444.

Dimitriades, Z. S. (2006). Customer satisfaction loyalty and commitment in service organizations. Management Research News., 29 (12), 782–800.

Ekanayake, E., & Long, A. E. (2012). Tourism development and economic growth in developing countries. The International Journal of Business and Finance Research., 6 (1), 61–63.

Esman, M. (1984). Tourism as ethnic preservation: The Cajuns of Louisiana. Annals of Tourism Research., 11 , 451–467.

Fernández Poncela, A. M. (2018). Turismo, negocio o desarrollo: El caso de Huasca. México. PASOS, 16 (1), 233–251.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research , 18 (1), 39–50.

Gee, C. Y., Mackens, J. C., & Choy, D. J. (1989). The Travel Industry . Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism . https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

Gunn, C. A. (1988). Tourism Planning . Taylor and Francis.

Gursoy, D., & Jurowski, C., (2000). Resident attitudes in relation to distance from tourist attractions. Travel and Tourism Research Association, http://www.ttra.com

Gursoy, D., Jurowski, C., & Uysal, M. (2002). Resident attitudes: A structural modeling approach. Annals of Tourism Research., 29 (1), 79–105.

Gursoy, D., Ouyang, Z., Nunkoo, R., & Wei, W. (2018). Residents’ impact perceptions of and attitudes towards tourism development: a metaanalysis. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management , 28 , 1–28.

Hair, J. F., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2017). An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management & Data Systems , 117 (3), 442–458.

Hallowell, R. (1996). The relationship of customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, profitability: An empirical study. International Journal of Service Industry Management., 7 (4), 27–42.

Hancock, A. (2020). Grounded flights force Tui to cut staff hours and wages. Financial Times. Online. https://www.ft.com/content/85a8d648-6a07-11ea-800d-da70cff6e4d3 .

Harrison, D. (1992). Tourism to less developed countries: The social consequences in tourism and less developed countries . Bellhaven.

Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2020). Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tourism Geographies . https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757748

Higgins-Desbiolles, F., Carnicelli, S., Krolikowski, C., Wijesinghe, G., & Boluk, K. (2019). Degrowing tourism: Rethinking tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism., 27 (12), 1926–1944. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1601732

Hsu, C., & Huang, S. (2009). Effects of travel motivation, past experience, perceived constraint, and attitude on revisit intention. Journal of Travel Research , 48 , 29–44.

Huang, Y., & Liu, C. S. (2017). Moderating and mediating roles of environmental concern and ecotourism experience for revisit intention. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management., 29 (7), 1854–1872.

Hunter, L. M. (2000). A comparison of the environmental attitudes, concern, and behaviors of native-born and foreign-born US residents. Population and Environment., 21 (6), 565–580.

Hussain, K., Ali, F., Ari Ragavan, N., & Singh Manhas, P. (2015). Sustainable Tourism and resident satisfaction at Jammu and Kashmir India. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes., 7 (5), 486–499.

INE (2019): https://www.ine.es/

Jensen, J. M. (2015). The relationships between socio-demographic variables, travel motivations and subsequent choice of vacation. Advances in Economics and Business., 3 (8), 322–328.

Jurdana, D.S., & Frleta, D.S. (2012). Sustainable rural tourism development – tourists´satisfaction with Istria as a rural holiday destination. Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality Management in Opatija.Biennial International Congress. Tourism and Hospitality Industry, pp. 51–59.

Jurowski, C., Uysal, M., & Williamd, R. D. (1997). A theoretical analysis of host community resident reactions to tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 36 (2), 3–11.

Jurowski, C., & Gursoy, D. (2004). Distance effects on residents’ attitudes toward tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 31 (2), 296–312.

Kao, Y. F., Huang, L. S., & Wu, C. H. (2008). Effects of theatrical elements on experiential quality and loyalty intentions for theme parks. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research., 13 (2), 163–174.

Keogh, B. (1990). Resident and recreationists’ perceptions and attitudes with respect to tourism development. Journal of Applied Recreation Research., 15 (2), 71–83.

Kim, K., Oh, I., & Jogaratnam, G. (2007). College student travel: A revised model of push motives. Journal of Vacation Marketing , 13 (1), 73–85.

Lankford, S. V., & Howard, D. R. (1994). Developing a tourism attitude impact scale. Annals of Tourism Research, 21 , 121–139.

Li, M., Cai, L. A., Lehto, X. Y., & Huang, J. (2010). A missing link in understanding revisit intention-the role of motivation and image. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing., 27 (4), 335–348.

Liu, J. C., Sheldon, P. J., & Var, T. (1987). Residents perceptions of the environmental impacts of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 14 , 17–37.

Luo, Y., & Deng, J. (2008). The new environmental paradigm and nature-based tourism motivation. Journal of Travel Research., 46 (4), 392–402.

MacKenzie, D., & Royle, A. (2005). Designing occupancy studies: general advice and allocating survey effort. Methodological Insights , 42 (6), 1105–1114.

Mathieson, A., & Wall, G. (1982). Tourism: Economic, Physical, and Social Impacts . Longman House.

Michael, J.M., (2013). Power Hand Tool customers´ Determination of Service Quality and Satisfaction in Repair/return Process. Dissertation at Campella University; Ann Arbor: PreQuest LLC.

Miller, D., Merrilees, B., & Coughlan, A. (2014). Sustainable urban tourism: Understanding and developing pro-environmental behaviours. Journal of Sustainable Tourism., 23 (1), 26–46.

Mohaidin, Z., Tze Wei, K., & Ali Murshi, M. (2017). Factors influencing the tourists´ intention to select Sustainable Tourism destination: A case study of Penang Malaysia. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 3 (4), 442–465.

Murphy, P. E. (1983). Community attitudes to tourism. Tourism Management, 2 , 189–195.

Murphy, P. E. (1985). Tourism: A Community Approach . Routledge.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Nunkoo, R., & So, K.K.F., (2015). Residents’ support for tourism: Testing alternative structural models. Journal of Travel Research .

Ohn, P., & Supinit, V. (2016). Factors influencing tourist loyalty of international graduate students: A study on tourist destination in Pattaya Thailand. International Journal of Thesis Projects and Dissertations, 4 (1), 45–55.

Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research., 17 (4), 460–469.

Oliver, R. L. (1997). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer . New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc.

OMT. (2005). Indicadores de Desarrollo Sostenible para los destinos turísticos - Guía práctica . Organización Mundial del Turismo.

Othman, N., Anwar, N. A. M., & Kian, L. L. (2010). Sustainability analysis: Visitors impact on taman negara. Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Culinary Arts, 2 (1), 67–79.

Palacios-Florencio, B., García del Junco, J., Castellanos-Verdugo, M., & Rosa-Díaz, I. M. (2018). Trust as mediator of corporate social responsibility, image and loyalty in the hotel sector. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26 (7), 1273–1289. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1447944

Pavlić, I., Portolan, A., & Puh, B. (2017). Supported current tourism development in UNESCO protected site: The case of old city of dubrovnik. Economies , 5 , 9.

Pesonen, J., Raija, K., Kronenberg, C., & Peters, M. (2011). Understanding the relationship between push and pull motivations in rural torurism. Tourism Review, 66 (3), 32–49.

Pizam, A. (1978). Tourism’s impacts: The social costs to the destination community as perceived by its residents. Journal of Travel Research, 16 (4), 8–12.

Pizam, A. (1994). Monitoring customer satisfaction. Food and Beverage Management: A selection of Readings, Bertrand, D. and Andrew L. (Eds). Butterworth-Heineman. Oxford, 231–247.

Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology , 88 , 879–903.

Prebensen, N. K. (2006). Segmenting the group tourist heading for warmer weather—a Norwegian example. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 19 (4), 27–40.

Pretizzo Páez, M. A. (2020). El impacto de la COVID-19 en el sector turismo, academia.edu, 1–10-

Real, J. C., Leal, A., & Roldán, J. L. (2006). Information technology as a determinant of organizational learning and technological distinctive competencias. Industrial Marketing Management , 35 (4), 505–521.

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J.-M. (2015). SmartPLS 3 . Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH.

Ritchie, J. R. B. (1988). Consensus policy formulation in tourism. Tourism Management, 9 , 199–216.

Roldán, J. L., & Cepeda, G. (2018). Curso sobre PLS-SEM, 6ª edición . Universidad de Sevilla.

Roldán, J. L., & Sanchez-Franco, M. J., (2012). Variance-based structural equation modeling. In M. Mora, et al. (Eds.), Research methodologies, innovations and philosophies in software systems engineering and information systems (pp. 193–221). USA: IGI Global.

Rothman, R. A. (1978). Residents and transients: community reaction to seasonal visitors. Journal of Travel Research, 16 (3), 8–13.

Ruhanen, L., Weiler, B., Moyle, B., & Moyle, C. (2015). Trends and patterns in sustainable tourism research: A 25-year bibliometric analysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism , 23 , 517–535.

Santana-Jiménez, Y., & Hernández, J. M. (2011). Estimating the effect of overcrowding on tourist attraction: The case of Canary Islands. Tourism Management, 32 (2), 415–425.

Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., Thiele, K. O., & Gudergan, S. P. (2016). Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: Where the bias lies. Journal of Business Research , 69 (10), 3998–4010.

Sethna, R., & Richmond, B. (1978). US Virgin islanders’ perceptions of tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 17 (1), 30–37.

Sharpley, R. (2020). Tourism, sustainable development and the theoretical divide: 20 years on. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28 (11), 1932–1946.

Sheldon, P. J., & Var, T. (1984). Resident attitudes to tourism in north wales. Tourism Management, 5 , 40–47.

Stylidis, D., Biran, A., Sit, J., & Szivas, E. (2014). Residents' support for tourism development: The role of residents' place image and perceived tourism impacts. Tourism Management , 45 , 260–274.

Su, W.-S., & Chang, L.-F. (2017). Developing sustainable tourism attitude in Taiwanese residents. The International Journal of Organizational Innovation, 10 (1), 275–289.

Sung, Y.-H., Su, C.-S., & Chang, W.-C. (2016). The quality and value of Hualien´s harvest festival. Annals of Tourism Research, 56 , 128–163.

Tosun, C. (2002). Host perceptions of impacts: A comparative tourism study. Annals of Tourism Research, 29 , 231–245.

Tyrell, T. J., & Spaulding, I. A. (1984). A survey of attitudes toward tourism growth in Rhode Island. Hospitality Education and Research Journal, 8 (2), 22–33.

Var, T., Kendall, K. W., & Tarakcoglu, E. (1985). Residents attitudes toward tourists in a Turkish Resort Town. Annals of Tourism Research, 12 , 652–658.

Vargas, A. et. al., (2007). Desarrollo del turismo y percepción de la comunidad local: factores determinantes de su actitud hacia un mayor desarrollo turístico. XXI Congreso Anual AEDEM, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Madrid, 6,7, y 8 de junio de 2007/Vol.1, pág. 24, coord. por Carmelo Mercado Idoeta.

Venkatesh, U. (2006). Leisure meaning and impact on leisure travel behaviour. Journal of Service Research, 6 (1), 87–108.

Walls, A., Okumus, F., Wang, Y., & Kwun, D. J. (2011). Understanding the consumer experience: An exploratory study of luxury hotels. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 20 (2), 166–197.

Weaver, D. B. (2012). Organic, incremental and induced paths to sustainable mass tourism convergence. Tourism Management., 33 (5), 1030–1037.

Werts, C., Linn, R., & Joreskog, K. (1974). Intraclass reliability estimates: Testing structural assumptions. Educational and Psychological Measurement , 34 , 25–33.

Wong, B. K., Ghazali, M., & Azni, Z. T. (2017). Malaysia my second home: The influence of push and pull motivations on satisfaction. Tourism Management, 61 , 394–410.

World Travel and Tourism Council, (2019). https://wttc.org/en-gb/

World Health Organization (2020): https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public

Wu, H.-C., & Li, T. (2015). An empirical study of the effects of service quality, visitor satisfaction, and emotions on behavioral intentions of visitors to the museums of macau. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism , 16 (1), 80–102.

Wu, H.-C., Ai, C.-H., & Cheng, C.-C. (2016). Synthesizing the effects of green experiential quality, green equity, green image and green experiential satisfaction on green switching intention. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28 (9), 2080–2107.

Xu, J., & Shukman, C. (2016). A new nature-based tourism motivation model: Testing the moderating effects of the push motivation. Tourism Management Perspectives, 18 , 107–110.

Yoon, Y., & Uysal, M. (2005). An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A strucutural model. Tourism Management, 26 (1), 45–56.

Zhang, H., & Lei, S. L. (2012). A structural model of residents’ intention to participate in ecotourism: The case of a wetland community. Tourism Management, 33 (4), 916–925.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Business Organization and Marketing, Faculty of Business Studies, University of Pablo de Olavide, Carretera Utrera, Km.1, 41013, Seville, Spain

Beatriz Palacios-Florencio & Juan Manuel Berbel-Pineda

Department of Business Organization, Faculty of Law and Business, University of Córdoba, Puerta Nueva s.n., 14071, Córdoba, Spain

Luna Santos-Roldán & Ana María Castillo-Canalejo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Beatriz Palacios-Florencio .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 18 KB)

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Palacios-Florencio, B., Santos-Roldán, L., Berbel-Pineda, J.M. et al. Sustainable Tourism as a Driving force of the Tourism Industry in a Post-Covid-19 Scenario. Soc Indic Res 158 , 991–1011 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02735-2

Download citation

Accepted : 04 June 2021

Published : 12 June 2021

Issue Date : December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02735-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Sustainable tourism

- Mass tourism

- Overcrowded destinations

- Tourism crisis

- Sustainable Tourism development

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Impact of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry

Marinko Škare.

a Juraj Dobrila University of Pula, Faculty of Economics and Tourism “Dr. Mijo Mirković”, Croatia

Domingo Riberio Soriano

b University of Valencia, Spain

Małgorzata Porada-Rochoń

c Faculty of Economics, Finance and Management, University of Szczecin, Poland

Our paper is among the first to measure the potential effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism industry. Using panel structural vector auto-regression (PSVAR) (Pedroni, 2013) on data from 1995 to 2019 in 185 countries and system dynamic modeling (real-time data parameters connected to COVID-19), we estimate the impact of the pandemic crisis on the tourism industry worldwide. Past pandemic crises operated mostly through idiosyncratic shocks' channels, exposing domestic tourism sectors to large adverse shocks. Once domestic shocks perished (zero infection cases), inbound arrivals revived immediately. The COVID-19 pandemic, however, is different; and recovery of the tourism industry worldwide will take more time than the average expected recovery period of 10 months. Private and public policy support must be coordinated to assure capacity building and operational sustainability of the travel tourism sector during 2020–2021. COVID-19 proves that pandemic outbreaks have a much larger destructive impact on the travel and tourism industry than previous studies indicate. Tourism managers must carefully assess the effects of epidemics on business and develop new risk management methods to deal with the crisis. Furthermore, during 2020–2021, private and public policy support must be coordinated to sustain pre-COVID-19 operational levels of the tourism and travel sector.

1. Introduction

From the start of the COVID-19 crisis in China, the impact of the pandemic on the travel tourism industry was significantly underestimated. Even now, policymakers and tourism practitioners do not have a full understanding of the scenarios and effects of the crisis, which will have an unprecedented impact on the tourism industry. Empirical studies on the impact of pandemic outbreaks on the tourism industry are widely missing in the literature. Our paper is among the first to measure the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the short and long term, both worldwide and on a geographical level. The study attempts to explore what is expected to be a negative impact on the world and the geographical travel and tourism industry. It also plans to investigate the nature of the impact. Understanding the level of potential impact and the global channels of transmission will help us predict the extent of current and future epidemic effects on the travel and tourism industry. It will help policymakers and practitioners design policies aimed at capacity building and operational sustainability of the travel tourism sector during 2020–2021 as a policy response to the COVID-19 crisis. Health care quality innovation will play an important role in fighting this pandemic crisis ( Zsifkovits et al., 2016 ).

The latest research report of the world travel and tourism council (WTTC) lists up to 75 million workers at immediate job risk as a result of COVID-19. Research reveals a potential Travel Tourism GDP loss in 2020 of up to US$ 2.1 trillion. WTTC also estimates the daily loss of a shocking one million jobs in the travel tourism sector for the widespread impact of the coronavirus pandemic. Pine and McKercher (2004) researched the impact of the SARS epidemic in 2002 on China's Guandong Province. Their study results show that the impact was negative, substantial, and significant. Mao et al. (2010) studied recovery patterns in Taiwan after the SARS outbreak using a catastrophe cusp model (for details see Sewell et al., 1977 ; Woodcock and Davis, 1978 ; Zeeman, 1976 ) and discovered two factors necessary for recovery from catastrophe to a normal state. The post-recovery period depends on the level of hysteresis and institutional efficiency in facing critical events. Kuo et al. (2008) found that epidemic crises affect tourism demand differently. Results of their study on SARS (2001–2004) and the widespread avian flu (2002–2006) show that SARS had an important impact on tourism demand in China, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan. The spread of avian flu, however, did not have an important negative impact on the tourism demand in Asia despite the high fatality rate. Preceding studies on pandemic impacts must be extended, however, to account for COVID-19′s new patterns and characteristics. Although in the previous widespread cases (SARS, 2002; H1N1, 2009) inbound tourist arrivals recovered almost immediately after the pandemic alerts were lifted, this will not be the case for COVID-19, and we must take that into account the new empirical models on pandemic impacts. SARS affected Asian stock market integration ( Chen et al., 2018 ) and increased hygienic measures in a limited fashion, but the COVID-19 pandemic seems to demand stricter measures ( Kostoff, 2011 ). Information and communication technologies (ICTs) will play a crucial role in fighting COVID-19 ( Gaspar et al., 2019 ).

To test the impact of COVID-19 on the travel tourism industry worldwide, we set up a dynamic model using an annual data set from 1995 to 2019. The model included 185 countries over 16 different regions and world in total. From the estimated PSVAR models, we take parameters on the empirical link between TCGD, TCEMP, SPEND, GOV, INV, and IPANDEMIC shock. Estimated parameters reflect the empirical link of past pandemic episodes from 1980 to 2019 but say little about the empirical link of the above variables with COVID-19. Demographic patterns in Europe and the rest of the world make population more vulnerable to future epidemic outbreaks ( Skirbekk et al., 2015 ).

To summarize our study results, the impact of COVID-19 on the travel tourism industry will be incomparable to the consequence of the previous pandemic episodes. Depending on the dynamics of future pandemics (from April 2020), the best-case scenario (scenario 1) shows that the travel tourism industry worldwide will drop on average from −2.93 percentage points to −7.82 in the total GDP contribution. Jobs in the travel tourism industry will decrease by −2.44 percentage points to −6.55. The estimated lost inbound tourist spending ranges from −25.0 percentage points to −35.0. Total capital investments that fall due to pandemics varies from −25.0 percentage points to −31.0. The impact is different across regions and in scenarios 1–3, which we further explain in the study.

The paper is structured as follows. After the introduction, Section 2 presents a summary of epidemic outbreaks worldwide since 1980. Section 3 describes the data sample (countries and regions in the sample) and the period used in the modeling process. Section 4 explains the methodological framework of PSVAR with a summary of the results. In Section 5 , we develop a system dynamics model that includes the empirical relationship obtained from PSVAR, extended for the new parameters (pattern and dynamic) that resulted from the COVID-19 crisis. We discuss the empirical study results in the Section 6 . Section 7 offers concluding remarks on the empirical study results and directions for further research.

2. Epidemic outbreak episodes and tourism worldwide trends since 1980

Several distinct factors determine the impact of an epidemic outbreak on tourism demand. Geographical distance to ground zero (infection epicenter) and infectious power are two of the most distinct. Other modern determinants are media attention (Internet revolution) and associated hysteria. Present worldwide socioeconomic conditions and terrorism, together with conditions of world conflict, impact tourism demand. Oil prices and environmental conditions also exhibit a substantial effect on the number of international tourists travelers. Furthermore, episodes of epidemic outbreaks have coincided with economic turmoil, both nationally and internationally, in the last 53 years (see Table 1 ). Because of tourism's seasonality character and vulnerability to exogenous factors, measuring the impact of an individual factor is a complicated task. This study aims to measure the impact of virus outbreaks on the tourism demand globally since 1980 as a prerequisite to measuring the COVID-19 impact. Several virus outbreaks globally affected worldwide tourism trends and the world economy after World War II (WWII). Table 1 shows the infections and deaths of significant virus outbreaks in the last 53 years.

Infections and deaths of significant virus outbreaks in the last 53 years.

In the past 50 years, the world has experienced several virus outbreaks with different levels of infections and mortality rates. Fig. 1 plots the virus outbreak episodes to the total number of tourist arrivals by world regions from 1950 to 2018. As expected, the impact varies by world regions depending on the source and distance to the virus outbreak source (ground zero countries).

International tourist arrivals by world regions 1950–2018.

Fig. 1 shows the that different epidemic outbreaks produce different worldwide impacts. Virus epidemic diseases, like SARS (2002) and H1N1(2009), have a large and significant impact on worldwide tourism trends and economic opportunity costs. Epidemic outbreaks with less infectious power (R naught - R 0 <1) have a lower impact on tourism trends and associated economic losses. Fig. 1 illustrates that the drop in tourist arrivals due to epidemic outbreaks varies across world regions. Table 2 displays registered (direct) drops in the number of tourist arrivals by world regions according to data from the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO)—a United Nations specialized agency—database.

Tourist arrivals and spending in a time of epidemic outbreaks by world regions, 1980–2019.

Table 2 shows that the total lost tourist arrivals worldwide from 1980 to 2019 amounted to 57 million (M) during the epidemic outbreaks. Lost tourism spending worldwide in times of epidemic outbreaks during this same period reached 95 US$ billion (bn). In relative terms, total lost tourism spending in a time of epidemic crisis was 0.23% of the world GDP (to the average world GDP value from 1980 to 2018). Epidemic outbreaks vary significantly between the type of disease outbreak and across world regions. Africa did not experience a significant impact on the tourism demand during the epidemic crisis; total losses were 2 bn US$ in tourism spent from 1980 to 2019.

The SARS epidemic crisis of 2002 and H1N1 (2009) caused a striking drop in tourist arrivals by −10 million in the Americas region; in tourism spending, the loss was −21 bn US$ in the that region. The Asiatic and Pacific regions experienced a significant drop in tourist arrivals during the bird flu epidemic (1997), SARS (2002), and H1N1(2009). Lost arrivals during the bird flu crisis in that region was −1 million, and lost spending amounted to −2 bn US$ . The decline in the tourist arrivals in the region at the time of the SARS (2002) outbreaks was −12 million with a related −2 bn US$ in lost revenue. During the H1N1 (2009) crisis, the region experienced −3 million tourist arrivals decline and −6 bn US$ lost tourism spending. The European region was not significantly hit by most of the outbreaks and epidemics from 1980 to 2019 (for the distance to the virus originating region). However, in the H1N1 epidemics (2009), there was a decline of −26 million tourist arrivals and a −61 bn US$ total tourism spending loss (amounting to 0.5% of the Europe GDP at the time). In H1N1 epidemic episode, however, Europe was affected strikingly with a total decline in tourist arrivals and spending loss that surpassed the economic impact for all other world regions over the 1980–2019 period.

The Middle East region suffered travel disruptions during the H1N1 (2009) epidemic crisis, causing a −3 million decline in tourist arrivals. Tourist spending, however, did not register a decline due to a rise in the receipts per arrival. The bird flu (2013) crisis faced a −2 million decline in tourist arrivals and −1 bn US$ in international visitor spending.

We associate epidemic outbreaks with significant opportunity costs in tourism demand. Although epidemic outbreaks significantly shape and influence the tourism industry, multiple causality issues (e.g., outbreaks followed by environmental and security issues or political and economic crises) arise when it comes to measuring the opportunity costs of epidemic outbreaks. To address this issue, we use structural vector auto-regression (SVAR) models to estimate the direct and opportunity costs of COVID-19 on the tourism industry (and economy) worldwide.

3. Data and facts on pandemics' impact on travel and tourism

The travel and tourism industry in the time of services-led growth trends has become increasingly important worldwide since 1990. From 1995, the travel and tourism industry's direct contribution to the world GDP increased from 9.9% in 1995 to 10.3% in 2019. A significant impact of the travel and tourism industry is also visible on employment levels. The total contribution to world employment in 2019 was 10.4%. The SARS epidemic in 2003 and the financial crisis of 2008 had a significant negative impact on world and regional travel and tourism industries.

We use annual data for 185 countries grouped in 16 world regions: Africa, the Americas, Asia Pacific, Caribbean, Central Asia, Europe, Latin America, Middle East, Northeast Asia, North Africa, Northern America, Oceania, other Europe, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa. All data are in real prices (CPI US$ 2000=100 index), adjusted for the impact of inflation. We utilize two main databases: World travel and tourism council (WTTC) data gateway (wttc.org/datagateway) and UNWTO (unwto.org/data). All data are in annual frequencies from 1995 to 2019. Data series (variables) we use for modeling:

- • TCGDP = total (indirect and induced impact) of travel and tourism contribution to the national/regional GDP (in real US$ bn, WTTC 2020 )

- • TCEMP = total (indirect and induced impact) travel and tourism contribution to national/regional employment (in 000 of jobs, WTTC 2020 )

- • SPEND = total spending in the domestic economy by foreign visitors (in real US$ bn, WTTC 2020 ),

- • ARRIVALS = total tourist arrivals (in 000, UNWTO 2020 )

- • GOV = individual government expenditures on travel and tourism (in real US$ bn, WTTC 2020 )

- • INV = Investment - capital investment both private and public (in real US$ bn, WTTC 2020 )

- • PANDEMIC = dichotomous (dummy) variable, PANDEMIC = 1 when no pandemic outbreaks exist and PANDEMIC = 0 when pandemic outbreaks are present

- • IPANDEMIC = measures the impact of pandemic outbreaks SARS (2002), H1N1 (2009), MERS (2012), and H7N9 bird flu (2013)

To correctly capture the pandemic impact, we use the interaction variable (model) with ARRIVALS as a continuous variable (000 of jobs) and PANDEMIC as a dichotomous variable (dummy variable 0,1).

4. Measuring pandemics' impact on the tourism industry using PSVAR

Our goal is to analyze the impact of the new coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak on world tourism dynamics. To our knowledge, this study is the first attempt to measure the impact of the current COVID-19 outbreak on tourism worldwide. To estimate the impact of COVID-19′s ongoing outbreak, we model the COVID-19 shocks using time series data for past coronavirus outbreaks; for SARS (2002), H1N1 (2009), and Ebola (2004); and for the past epidemic outbreaks of Hendra (1994), H5N1 bird flu (1997), Nipah (1998), MERS (2012), and H7N9 bird flu (2013). However, COVID-19 is a new type of virus, and it brings much uncertainty connected to the speed of spread, infectious power, mortality rate, and future dynamics of the virus. Therefore, we use the current state of knowledge on the COVID-19 reproduction number (R0) ( Kucharski et al., 2020 ) to calibrate our models for the SARS (2002) and H1N1(2009) variance. To study the impact of COVID-19 on tourism worldwide, we use the heterogeneous PSVAR model as developed by Pedroni (2013) . Using the PSVAR model—Ewiews code provided by Luvsannyam (2018) and Góes (2016) —we estimated how the COVID-19 shocks on tourism (arrivals, spending) propagated across world regions. We have a strong heterogeneous sample, so using PSVAR enabled us to estimate the impact of the COVID-19 shock on tourism, depending on the following factors: region-specific socioeconomic conditions, vulnerability to external shocks, health system stability, environmental conditions, tourism sector stability, and competitiveness.

Following Pedroni (2013) , we decomposed the impact of the structural shock (COVID-19) into common shock (effects of COVID-19 outbreak originating in any other region in the sample and propagating to region-specific tourism industry) and idiosyncratic shock.

Idiosyncratic shocks show the impact of COVID-19 originating in a member-specific region on the tourism industry in the same region. As in Biljanovska et al. (2017) and Pedroni (2013) , we refer to the measured COVID-19 effects on the tourism industry as a common component or spillover (common shock), and to an idiosyncratic component as country-specific (idiosyncratic shock).

We use the following estimation model for an unbalanced panel using data from 1995 to 2019 in the PSVAR bivariate form (for details see Góes (2016) ; Pedroni (2013) ; Biljanovska et al. (2017) :

where y * i,t is an s n-dimensional vector of demeaned stacked endogenous variables, and

which equals polynomial of lagged coefficients with country-specific lag lengths J i , coefficient matrix A i j , vector of stacked residuals e i,t and B i contemporaneous coefficient matrix ( Góes, 2016 ).

In this model, we allow for full heterogeneity and robust inference decomposing (using time effects) impulse response function to idiosyncratic shocks and common shocks (region-specific response). To estimate the impact of pandemic outbreaks, we use TCGDP, TCEMP, SPEND, ARRIVALS, GOV, and INV as endogenous variables, and PANDEMIC (dummy), IPANDEMIC (interaction variable), defined in Section 3 . Structural shock (white noise vector) takes the form

with ε ¯ t ′ = vector of common white noise and ε ˜ i t = vector of idiosyncratic white noise shocks.

Composite white noise errors equal