- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

It’s a New Era for Mental Health at Work

- Kelly Greenwood

Research on how the past 18 months have affected U.S. employees — and how companies should respond.

In 2019, employers were just starting to grasp the prevalence of mental health challenges at work, the need to address stigma, and the emerging link to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). One silver lining amid all the disruption and trauma over the last two years is the normalization of these challenges. In a follow-up study of their 2019 Mental Health at Work Report, Mind Share Partners’ 2021 Mental Health at Work Report, the authors offer a rare comparison of the state of mental health, stigma, and work culture in U.S. workplaces before and during the pandemic. They also present a summary of what they learned and their recommendations for what employers need to do to support their employees’ mental health.

When we published our research on workplace mental health in October 2019, we never could have predicted how much our lives would soon be upended by the Covid-19 pandemic. Then the murders of George Floyd and other Black Americans by the police; the rise in violence against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPIs); wildfires; political unrest; and other major stressors unfolded in quick succession, compounding the damage to our collective mental health.

- Kelly Greenwood is the Founder and CEO of Mind Share Partners , a national nonprofit changing the culture of workplace mental health so both employees and organizations can thrive. Through movement building , custom training, and strategic advising, it normalizes mental health challenges and promotes sustainable ways of working to create a mentally healthy workforce. Follow her on LinkedIn and subscribe to her monthly newsletter.

- Julia Anas is the chief people officer at Qualtrics, the world’s #1 Experience Management (XM) provider and creator of the XM category. At Qualtrics, she is responsible for building a talented and diverse organization and driving employee development as well as organizational design, talent, and succession planning.

Partner Center

Ellice Weaver / Wellcome

Understanding what works for workplace mental health: putting science to work

This report summarises what we’ve learned from our first commission on promising approaches for addressing workplace mental health. It also sets out why businesses and researchers need to work together to take a more scientific approach to supporting mental health at work.

- Share with Facebook

- Share with X

- Share with LinkedIn

- Share with Email

What’s inside

- findings from ten research projects that looked at the evidence behind promising approaches for supporting workplace mental health

- suggested actions businesses can take, based on this evidence

- reflections on gaps in the evidence and why it’s important for businesses and scientists to work together to understand what works.

Who this is for

- policy makers

- researchers.

Key findings

Businesses all over the world are thinking about how they can most effectively support the mental health of their staff. But despite growing interest and investment in workplace mental health initiatives in recent years, there is still so much we don't know about what works and what doesn’t.

In 2020, Wellcome commissioned ten global research teams to look at the existing evidence behind promising approaches for addressing anxiety and depression in the workplace, with a focus on younger workers.

Key findings include:

- Excessive sitting has risks for both physical and mental health. Reducing the time office workers spend sitting by an hour a day may reduce depression symptoms by approximately 10% and anxiety symptoms by around 15%.

- Flexible working can benefit mental health by decreasing the amount of conflict people experience between their work and home lives. This conflict can be a source of stress and may contribute to anxiety and depression.

- More job autonomy is associated with lower rates of anxiety and depression. Employers can increase employees' autonomy by allowing them more freedom to craft how they do their roles.

- There is significant evidence from high-income countries to show that workplace mindfulness interventions have a positive impact on mental health. But far less is known about their effectiveness in low- and middle-income countries.

The research identifies important gaps in our knowledge about what works. Businesses and scientists need to work together to fill these gaps in the evidence to understand how employers can most effectively support the mental health of their staff.

Downloads

Summary report.

- Putting science to work: understanding what works for workplace mental health PDF 7.3 MB

Individual research reports submitted to Wellcome

- Breaking up excessive sitting with light activity PDF 1.1 MB

- Buddying at onboarding PDF 1.2 MB

- Employee autonomy PDF 1.9 MB

- Financial wellbeing interventions PDF 1.1 MB

- Flexible working policies PDF 1.4 MB

- Group psychological first aid for humanitarian workers and volunteers PDF 1.3 MB

- Mental health peer support PDF 1.8 MB

- Mindfulness in hospitality and tourism in low- and middle-income countries PDF 1.8 MB

- Social support interventions for healthcare workers PDF 3.3 MB

- Workforce involvement and peer support networks in low- and middle-income countries PDF 1.4 MB

Contact us

For more information, contact Rhea Newman, Policy and Advocacy Adviser, at [email protected] .

Mental health

Related content .

Mental health at Wellcome: looking forward

Why science needs lived experiences of mental health challenges

Our Nation’s Current Workplace Landscape

Recent surveys suggest...

Written Document on Workplace Well‑Being

We can build workplaces that are engines of well-being, showing workers that they matter, that their work matters, and that they have the workplace resources and support necessary to flourish.

This 30-page Surgeon General’s Framework for Workplace Mental Health and Well-Being offers a foundation that workplaces can build upon. Download the document PDF or continue scrolling to learn more.

The Surgeon General’s Framework for Workplace Mental Health and Well‑Being

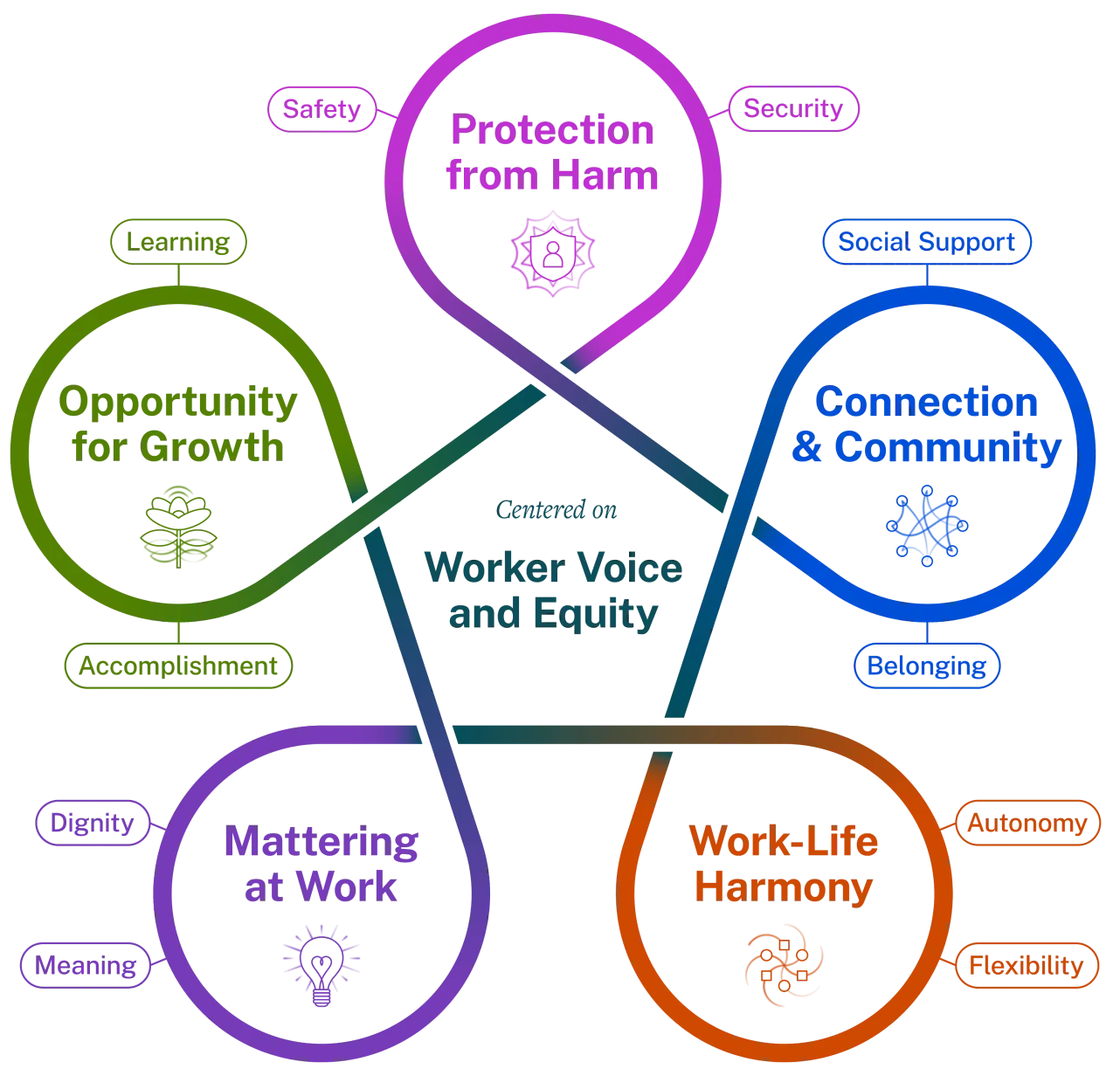

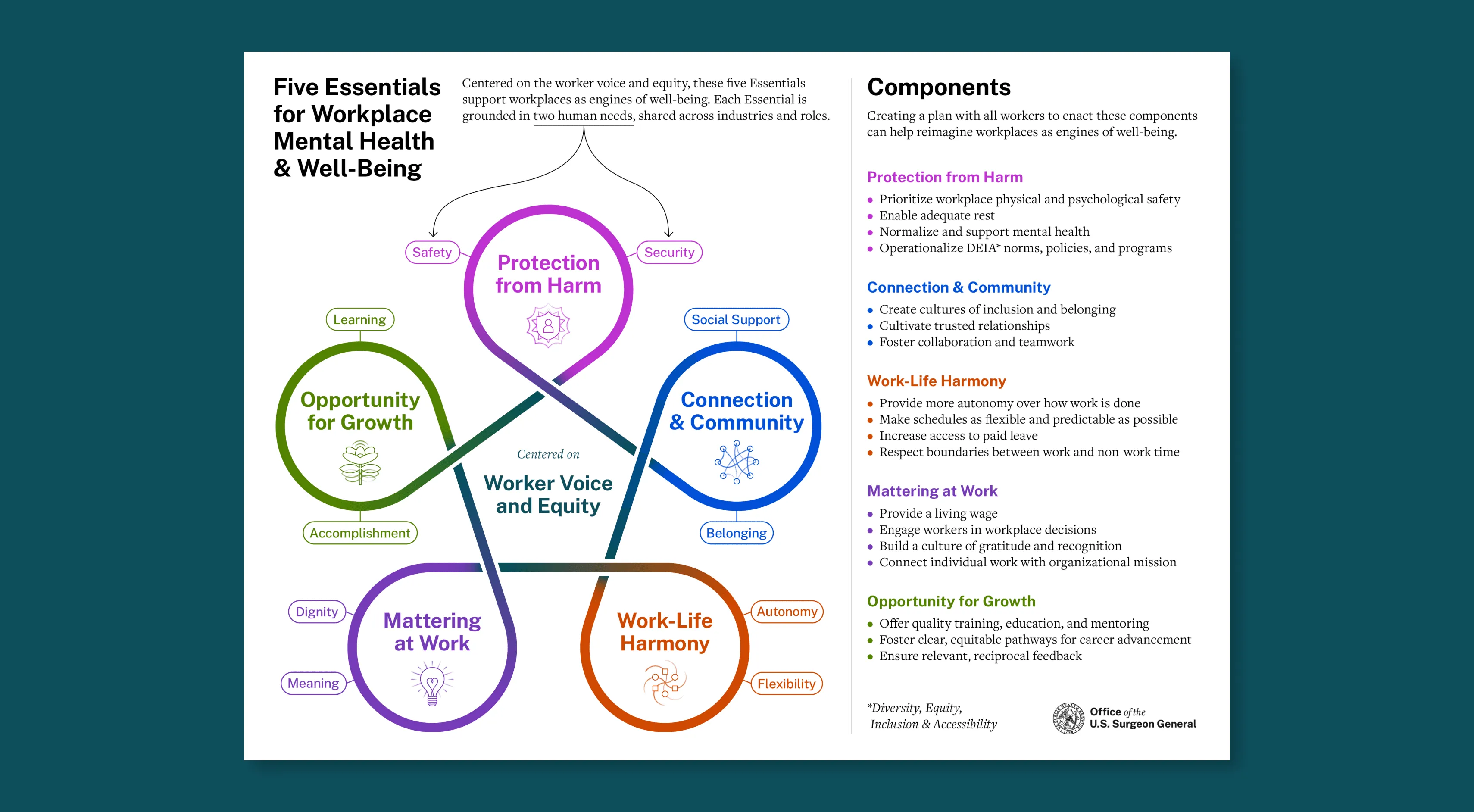

Centered on the worker’s voice and equity, these Five Essentials support workplaces as engines of well-being. Each essential is grounded in two human needs, shared across industries and roles. Creating a plan to enact these practices can help strengthen the essentials of workplace well‑being.

Explore the Framework

The first Essential of this Framework is Protection from Harm . Creating the conditions for physical and psychological safety is a critical foundation for ensuring workplace mental health and well-being. This Essential rests on two human needs: safety and security .

Safety is protecting all workers from physical and non-physical harm, including injury, illness, discrimination, bullying, and harassment.

Security is ensuring all workers feel secure financially and in their job future.

*Diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility

The second Essential of the Framework is Connection and Community . Fostering positive social interactions and relationships in the workplace supports worker well-being. This Essential rests on two human needs: social support and belonging .

Social Support is having the networks and relationships that can offer physical and psychological help, and can mitigate feelings of loneliness and isolation.

Belonging is the feeling of being an accepted member of a group.

The third Essential of this Framework is Work-Life Harmony . Professional and personal roles can together create work and non-work conflicts. The ability to integrate work and non-work demands, for all workers, rests on the human needs of autonomy and flexibility .

Autonomy is how much control a worker has over when, where, and how they do their work.

Flexibility is ability of workers to work when and where is best for them.

The fourth Essential of the Framework is Mattering at Work . People want to know that they matter to those around them and that their work matters. Knowing you matter has been shown to lower stress, while feeling like you do not can raise the risk for depression. This Essential rests on the human needs of dignity and meaning .

Dignity is the sense of being respected and valued.

Meaning in the workplace can refer to the sense of broader purpose and significance of one’s work.

The final Essential of this Framework is Opportunity for Growth . When organizations create more opportunities for workers to accomplish goals based on their skills and growth, workers become more optimistic about their abilities and more enthusiastic about contributing to the organization. This Essential rests on the human needs of learning and a sense of accomplishment .

Learning is the process of acquiring new skills and knowledge in the workplace.

Accomplishment is the outcome of meeting goals and having an impact.

Conclusion & Next Steps

The Surgeon General’s Framework for Workplace Mental Health and Well-Being emphasizes the connection between the well-being of workers and the health of organizations. It offers a foundation and resources that can be used by workplaces of any size, across any industry. Sustainable change must be driven by committed leaders in continuous collaboration with the valued workers who power each workplace. The most important asset in any organization is its people. By choosing to center their voices, we can ensure that everyone has a platform to thrive.

Resources for Supporting Workplace Well‑Being

Visit our resources page to find more information about how to implement the framework in your workplace.

Key Downloads

Essentials for Workplace Mental Health and Well-Being Graphic

This graphic communicates the Five Essentials for Workplace Mental Health and Well-Being and their respective human needs and components, shared across industries and roles.

Workplace Mental Health and Well-Being Reflection Questions Deck

This is a deck of questions to help leaders reflect on their workplaces and start designing organizational policy and culture around the Five Essentials for Workplace Mental Health & Well-Being.

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Mental Health in the Workplace

Mental Health Disorders and Stress Affect Working-Age Americans

This issue brief is available for download [PDF – 2 MB]

Mental health disorders are among the most burdensome health concerns in the United States. Nearly 1 in 5 US adults aged 18 or older (18.3% or 44.7 million people) reported any mental illness in 2016.2 In addition, 71% of adults reported at least one symptom of stress, such as a headache or feeling overwhelmed or anxious. 4

Many people with mental health disorders also need care for other physical health conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, respiratory illness, and disorders that affect muscles, bones, and joints. 5–8 The costs for treating people with both mental health disorders and other physical conditions are 2 to 3 times higher than for those without co-occurring illnesses. 9 By combining medical and behavioral health care services, the United States could save $37.6 billion to $67.8 billion a year. 9

About 63% of Americans are part of the US labor force.10 The workplace can be a key location for activities designed to improve well-being among adults. Workplace wellness programs can identify those at risk and connect them to treatment and put in place supports to help people reduce and manage stress. By addressing mental health issues in the workplace, employers can reduce health care costs for their businesses and employees.

Mental Health Issues Affect Businesses and Their Employees

Poor mental health and stress can negatively affect employee:

- Job performance and productivity.

- Engagement with one’s work.

- Communication with coworkers.

- Physical capability and daily functioning.

Mental illnesses such as depression are associated with higher rates of disability and unemployment.

- Depression interferes with a person’s ability to complete physical job tasks about 20% of the time and reduces cognitive performance about 35% of the time. 11

- Only 57% of employees who report moderate depression and 40% of those who report severe depression receive treatment to control depression symptoms. 12

Even after taking other health risks—like smoking and obesity—into account, employees at high risk of depression had the highest health care costs during the 3 years after an initial health risk assessment. 13,14

Employers Can PROMOTE Awareness About the Importance of Mental Health and Stress Management

Workplace health promotion programs have proven to be successful, especially when they combine mental and physical health interventions.

The workplace is an optimal setting to create a culture of health because:

- Communication structures are already in place.

- Programs and policies come from one central team.

- Social support networks are available.

- Employers can offer incentives to reinforce healthy behaviors.

- Employers can use data to track progress and measure the effects.

Action steps employers can take include:

- Make mental health self-assessment tools available to all employees.

- Offer free or subsidized clinical screenings for depression from a qualified mental health professional, followed by directed feedback and clinical referral when appropriate.

- Offer health insurance with no or low out-of-pocket costs for depression medications and mental health counseling.

- Provide free or subsidized lifestyle coaching, counseling, or self-management programs.

- Distribute materials, such as brochures, fliers, and videos, to all employees about the signs and symptoms of poor mental health and opportunities for treatment.

- Host seminars or workshops that address depression and stress management techniques, like mindfulness, breathing exercises, and meditation, to help employees reduce anxiety and stress and improve focus and motivation.

- Create and maintain dedicated, quiet spaces for relaxation activities.

- Provide managers with training to help them recognize the signs and symptoms of stress and depression in team members and encourage them to seek help from qualified mental health professionals.

- Give employees opportunities to participate in decisions about issues that affect job stress.

Success Stories

Many Businesses PROVIDE Employees With Resources to Improve Mental Health and Stress Management

Prudential Financial 15

- Monitors the effect of supervisors on worker well-being, especially when supervisors change.

- Conducts ongoing, anonymous surveys to learn about attitudes toward managers, senior executives, and the company as a whole.

- Normalizes discussion of mental health by having senior leadership share personal stories in video messages.

TiER1 Performance Solutions 16

- Focuses on six key health issues: depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and addictions as part of its Start the Conversation about Mental Illness awareness campaign.

- Provides resources to assess risk, find information, and get help or support using multiple formats to increase visibility and engagement. For example, information is provided as infographics, e-mails, weekly table tents with reflections and challenges, and videos (educational and storytelling).

Beehive PR 17

- Maintains the “InZone,” a dedicated quiet room that is not connected to a wireless internet signal, which gives employees a place to recharge.

- Combines professional and personal growth opportunities through goal-setting, one-on-one coaching, development sessions, and biannual retreats.

Tripler Army Medical Center 18

- Requires resiliency training to reduce burnout and increase skills in empathy and compassion for staff members who are in caregiver roles. Training sessions mix classroom-style lectures, role-playing, yoga, and improvisational comedy to touch on multiple learning styles.

Certified Angus Beef 19

- Provides free wellness consultations by an on-site clinical psychologist. Employees do not have to take leave to access these services.

- Holds lunchtime learning sessions to reduce stigma about mental health and the services available to employees.

- Offers quarterly guided imagery relaxation sessions to teach stress management strategies.

Houston Texans 20

- Provides comprehensive and integrated physical, mental, and behavioral health insurance coverage, including round-the-clock access to employee assistance program (EAP) services.

- Extends EAP access to anyone living in an employee’s home, with dedicated programming for those who are caring for children or elderly parents.

What Can Be Done?

Strategies for Managing Mental Health and Stress in the Workplace

Health care providers can:

- Ask patients about any depression or anxiety and recommend screenings, treatment, and services as appropriate.

- Include clinical psychologists, social workers, physical and occupational therapists, and other allied health professionals as part of core treatment teams to provide comprehensive, holistic care.

Public health researchers can:

- Develop a “how-to” guide to help in the design, implementation, and evaluation of workplace health programs that address mental health and stress issues.

- Create a mental health scorecard that employers can use to assess their workplace environment and identify areas for intervention.

- Develop a recognition program that rewards employers who demonstrate evidence-based improvements in metrics of mental health and well-being and measurable business results.

- Establish training programs in partnership with business schools to teach leaders how to build and sustain a mentally healthy workforce.

Community leaders and businesses can:

- Promote mental health and stress management educational programs to working adults through public health departments, parks and recreational agencies, and community centers.

- Support community programs that indirectly reduce risks, for example, by increasing access to affordable housing, opportunities for physical activity (like sidewalks and trails), tools to promote financial well-being, and safe and tobacco-free neighborhoods.

- Create a system that employees, employers, and health care providers can use to find community-based programs (for example, at churches and community centers) that address mental health and stress management.

Federal and state governments can:

- Provide tool kits and materials for organizations and employers delivering mental health and stress management education.

- Provide courses, guidance, and decision-making tools to help people manage their mental health and well-being.

- Collect data on workers’ well-being and conduct prevention and biomedical research to guide ongoing public health innovations.

- Promote strategies designed to reach people in underserved communities, such as the use of community health workers to help patients access mental health and substance abuse prevention services from local community groups (for example, churches and community centers).

Employees can:

- Encourage employers to offer mental health and stress management education and programs that meet their needs and interests, if they are not already in place.

- Participate in employer-sponsored programs and activities to learn skills and get the support they need to improve their mental health.

- Serve as dedicated wellness champions and participate in trainings on topics such as financial planning and how to manage unacceptable behaviors and attitudes in the workplace as a way to help others, when appropriate.

- Share personal experiences with others to help reduce stigma, when appropriate.

- Be open-minded about the experiences and feelings of colleagues. Respond with empathy, offer peer support, and encourage others to seek help.

- Adopt behaviors that promote stress management and mental health.

- Eat healthy, well-balanced meals, exercise regularly, and get 7 to 8 hours of sleep a night.

- Take part in activities that promote stress management and relaxation, such as yoga, meditation, mindfulness, or tai chi.

- Build and nurture real-life, face-to-face social connections.

- Take the time to reflect on positive experiences and express happiness and gratitude.

- Set and work toward personal, wellness, and work-related goals and ask for help when it is needed.

Any mental illness is defined as having any mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder in the past year that met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (DSM-IV) criteria (excluding developmental disorders and substance use disorders). Mental illness can vary in impact, ranging from no impairment to mild, moderate, and even severe impairment.

Mindfulness is a psychological state of moment-to-moment awareness of your current state without feeling inward judgement about your situation. Mindfulness can be achieved through practices foster control and develop skills such as calmness and concentration.

Self-management is a collaborative, interactive, and ongoing process that involves educators and people with health problems. The educator provides program participants with the information, problem-solving skills, and tools they need to successfully manage their health problems, avoid complications, make informed decisions, and engage in healthy behaviors. These programs can be provided in person, over the phone, or online.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Behavioral Health Spending & Use Accounts, 1986-2014. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2016. HHS publication SMA-16-4975.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Mental illness website. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.shtml . Accessed March 29, 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data table for Figure 16. Health care visits in the past 12 months among children aged 2-17 and adults aged 18 and over, by age and provider type: United States, 1997, 2006, and 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2016/fig16.pdf [PDF – 898 KB] . Accessed July 3, 2018.

- American Psychological Association. Stress in America: Coping with Change, Part 1. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2017.

- Merikangas KR, Ames M, Cui L, Ustun TB, Von Korff M, Kessler RC. The impact of comorbidity of mental and physical conditions on role disability in the US adult household population. Arch Gen Psychiatry . 2007;64(10):1180–1188.

- Scott KM, Lim C, Al-Hamzawi A, et al. Association of mental disorders with subsequent chronic physical conditions: work mental health surveys from 17 countries. JAMA Psychiatry . 2016;73(2):150–158.

- Glassman AH. Depression and cardiovascular comorbidity. Dialogues Clin Neurosci . 2007;9(1):9–17.

- Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry . 2010;67(3):220–229.

- Melek SP, Norris DT, Paulus J, Matthews K, Weaver A, Davenport S. Potential Economic Impact of Integrated Medical-Behavioral Healthcare: Updated Projections for 2017. Milliman Research Report. Seattle, WA: Milliman, Inc.; 2018.

- US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Databases, Tables & Calculators by Subject website. Labor force statistics from the Current Population Survey. https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS11300000 . Accessed July 3, 2018.

- Lerner D, Henke RM. What does research tell us about depression, job performance, and work productivity? J Occup Environ Med . 2008;50(4):401–410.

- Dewa CS, Thompson AH, Jacobs P. The association of treatment of depressive episodes and work productivity. Can J Psychiatry . 2011;56(12):743–750.

- Goetzel RZ, Anderson DR, Whitmer RW, et al; Health Enhancement Research Organization (HERO) Research Committee. The relationship between modifiable health risks and health care expenditures: an analysis of the multi-employer HERO health risk and cost database. J Occup Environ Med . 1998;40(10):843–854.

- Goetzel RZ, Pei X, Tabrizi MJ, et al. Ten modifiable health risk factors are linked to more than one-fifth of employer-employee health care spending. Health Aff . 2012;31(11):2474–2484.

- American Psychological Association, Center for Organizational Excellence. The Awards website. Prudential Financial. http://www.apaexcellence.org/awards/organizational-excellence/oea2017 . Accessed July 3, 2018.

- American Psychiatric Association, Center for Workplace Mental Health. The Awards website. TiER1 Performance Solutions. http://workplacementalhealth.org/Case-Studies/Tier1PerformanceSolutions . Accessed July 3, 2018.

- American Psychological Association, Center for Organizational Excellence. The Awards website. Beehive PR. http://www.apaexcellence.org/awards/national/winner/54 . Accessed July 3, 2018.

- American Psychological Association, Center for Organizational Excellence. The Awards website. Resiliency Training. http://www.apaexcellence.org/awards/bphonors/winner/99 . Accessed July 3, 2018.

- American Psychological Association, Center for Organizational Excellence. The Awards website. Setting the Bar for Emotional Wellness. http://www.apaexcellence.org/awards/bphonors/winner/86 . Accessed July 3, 2018.

- American Psychiatric Association, Center for Workplace Mental Health. Case Study website. Houston Texans. http://workplacementalhealth.org/Case-Studies/Houston-Texans . Accessed July 3, 2018.

To receive email updates about Workplace Health Promotion, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

The Role of Mental Health on Workplace Productivity: A Critical Review of the Literature

- Review Article

- Published: 15 November 2022

- Volume 21 , pages 167–193, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Claire de Oliveira ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3961-6008 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Makeila Saka 2 ,

- Lauren Bone 2 &

- Rowena Jacobs ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5225-6321 1

23k Accesses

20 Citations

124 Altmetric

14 Mentions

Explore all metrics

Mental health disorders in the workplace have increasingly been recognised as a problem in most countries given their high economic burden. However, few reviews have examined the relationship between mental health and worker productivity.

To review the relationship between mental health and lost productivity and undertake a critical review of the published literature.

A critical review was undertaken to identify relevant studies published in MEDLINE and EconLit from 1 January 2008 to 31 May 2020, and to examine the type of data and methods employed, study findings and limitations, and existing gaps in the literature. Studies were critically appraised, namely whether they recognised and/or addressed endogeneity and unobserved heterogeneity, and a narrative synthesis of the existing evidence was undertaken.

Thirty-eight (38) relevant studies were found. There was clear evidence that poor mental health (mostly measured as depression and/or anxiety) was associated with lost productivity (i.e., absenteeism and presenteeism). However, only the most common mental disorders were typically examined. Studies employed questionnaires/surveys and administrative data and regression analysis. Few studies used longitudinal data, controlled for unobserved heterogeneity or addressed endogeneity; therefore, few studies were considered high quality.

Despite consistent findings, more high-quality, longitudinal and causal inference studies are needed to provide clear policy recommendations. Moreover, future research should seek to understand how working conditions and work arrangements as well as workplace policies impact presenteeism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Is working in later life good for your health? A systematic review of health outcomes resulting from extended working lives

Workplace Intervention Research: Disability Prevention, Disability Management, and Work Productivity

Researching complex and multi-level workplace factors affecting disability and prolonged sickness absence.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Mental health disorders in the workplace, such as depression and anxiety, have increasingly been recognised as a problem in most countries. Using a human capital approach, the global economic burden of mental illness was estimated to be US$$2.5 trillion in 2010 increasing to US$$6.1 trillion in 2030; most of this burden was due to lost productivity, defined as absenteeism and presenteeism [ 1 ]. Workplaces that promote good mental health and support individuals with mental illnesses are more likely to reduce absenteeism (i.e., decreased number of days away from work) and presenteeism (i.e., diminished productivity while at work), and thus increase worker productivity [ 2 ]. Burton et al. provided a review of the association between mental health and worker productivity [ 3 ]. The authors found that depressive disorders were the most common mental health disorder among most workforces and that most studies examined found a positive association between the presence of mental health disorders and absenteeism (particularly short-term disability absences). They also found that workplace policies that provide employees with access to evidence-based care result in reduced absenteeism, disability and lost productivity [ 3 ].

However, this review is now outdated. Prevalence rates for common mental disorders have increased [ 4 ], while workplaces have also responded with attempts to reduce stigma and the potential economic impact [ 5 ], necessitating the need for an updated assessment of the evidence. Furthermore, given that most of the global economic burden of mental illness is due to lost productivity [ 1 ], it is important to have a good understanding of the existing literature on this outcome. While the previous review focused on the prevalence of certain mental health conditions and the available interventions and workplace policies, this review focused on the measures of lost productivity and the instruments used, as well as the data and methods employed, which the previous review did not examine in depth. Thus, the objectives of this paper were to update the Burton et al. review [ 3 ] on the association between mental health and lost productivity, and undertake a critical review of the literature that has been published since then, specifically how researchers have studied this relationship, the type of data and databases they have employed, the methods they have used, their findings, and the existing gaps in the literature.

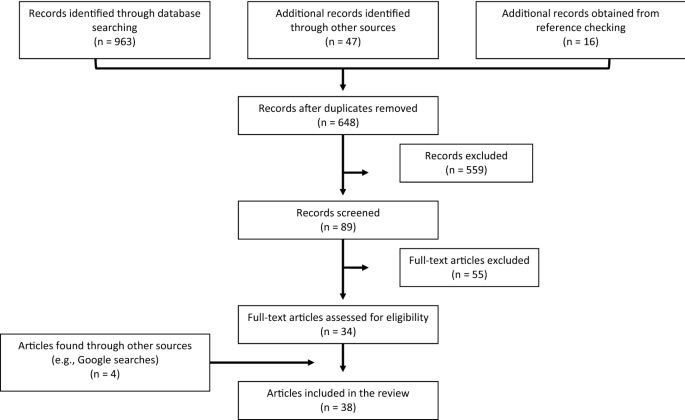

We undertook a critical review, i.e., a review that presents, analyses and synthesises evidence from diverse sources by extensively searching the literature and critically evaluating its quality [ 6 ], ultimately identifying the most significant papers in the field. Footnote 1 We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement [ 7 ] to guide our analysis. Our review focused on all studies published since 2008, which examined the relationship between mental health and workplace-related productivity among working-age adults. We used the Population, Intervention, Control, Outcomes, and Study design (known as PICOS) criteria to guide the development of the search strategy.

2.1 Eligibility Criteria

The populations of interest comprised working-age adults (18–65 years old). Studies focusing solely on volunteers and/or caregivers (i.e., unpaid workers) were excluded. The intervention(s), or rather more appropriately the exposure(s), had to be a diagnosis of any mental disorder/illness or self-reported mental health problem(s). Any studies that examined substance use and/or physical health in addition to mental health were included if results were reported separately for mental health-related outcomes. The control or comparator group, where applicable, included working age individuals without a mental disorder/illness or mental health problem(s). The outcome(s) included lost workplace productivity measured by absenteeism, presenteeism, sick leave, short- and/or long-term disability, or job loss. Studies that examined productivity of home-related activities (e.g., housework) were excluded. Studies with an observational study design and/or regression analysis were included; randomised control trials, cost-of-illness studies and economic evaluations were excluded (the first two were only included if they examined the relationship between mental health and lost productivity). Only original studies were considered; however, relevant reviews were retained for reference checking to find relevant studies, which may not have been captured by the search strategy.

2.2 Search Strategy

We searched literature published in English from 1 January 2008 to 31 May 2020. Structured searches were done in MEDLINE and EconLit to capture the most relevant literature published in the medical and economics fields, respectively. We also undertook relevant searches in Google and on specific websites of interest (e.g., UK Parliament Hansard, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Centre for Mental Health, the Health Foundation, the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the King’s Fund) and a hand search of the references of key papers [ 8 ]. Search terms or strings were developed on the basis of four concepts: population or workplace, intervention/exposure (i.e., presence of mental disorder/illness), work-related outcomes, and study design (see Table 1 ).

2.3 Study Selection

After duplicate records were removed, one reviewer (LB) screened all titles and abstracts while additional reviewers (CdO and RJ) were brought in for discussion, if/where necessary. Articles were excluded either because they did not examine the relationship between mental health and lost productivity (e.g., some cost-of-illness studies) or were mainly focused on physical health. Subsequently, all relevant full-text articles were retrieved and screened by one reviewer (LB) to confirm eligibility; additional reviewers (MS, RJ or CdO) were brought in, if/where necessary.

2.4 Data Extraction

Two reviewers (LB and MS) undertook the data extraction, and an additional reviewer (RJ or CdO) was assigned to resolve any disagreements. The research team developed a data extraction form, based on the Cochrane good practice data extraction form, which included study information (author(s), year of publication), country (where the study was published or conducted), aims of study, study design (cross-sectional, longitudinal), data source(s) (i.e., database(s), surveys/questionnaires), study population (sample size, age range), mental disorder(s) examined, workplace outcome examined (absenteeism, presenteeism, short-term disability, long-term disability, job loss, other), methods employed (statistical analysis, regression model employed), and results/key findings.

2.5 Quality Assessment

We reviewed the methods employed in the studies to assess their quality and robustness, drawing loosely on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, a risk-of-bias assessment tool for observational studies [ 9 ]. We paid particular attention to whether studies were able to move beyond simple associations and attempted to address causal inference, where necessary, and whether they took account of endogeneity (i.e., cases where the explained variable and the explanatory variable are determined simultaneously) and/or unobserved heterogeneity (i.e., cases where the presence of unexplained (observed) differences between individuals are associated with the (observed) variables of interest), which are common issues when examining the relationship between mental health and lost productivity. All studies that recognised and/or accounted for these issues were considered high quality. We also examined the type of data/databases employed (i.e., cross-sectional or longitudinal data and representative, population-based samples), findings, and limitations (and the extent to which these impacted the findings), which were also considered when determining the quality of a study.

2.6 Data Synthesis

Given the heterogeneity of studies examined, undertaking a meta-analysis was not possible. Therefore, we undertook a narrative synthesis of the relevant literature, where we synthesised the existing evidence by mental disorder/illness and workplace outcome (absenteeism, presenteeism, sick leave, short- and long-term disability, or job loss), if/where appropriate.

3.1 Study Selection

After all citations were merged and duplicates removed, our search produced 648 unique records, of which 89 full texts were assessed; four studies were obtained from other sources (e.g., Google searches). Ultimately, 38 studies were included in the final review [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 ] (see Fig. 1 ) and relevant data were extracted (see Table 2 and Table A1 in the Appendix for more details).

PRISMA flow diagram

3.2 Overview of Studies

All studies focused on individuals typically between the ages of 18 and 64/65 years. Some studies ( n = 5) examined individuals 20 or 25 years and older [ 11 , 12 , 16 , 28 , 38 ] to account for younger individuals who might still be in school and thus not working, while other studies had different lower and upper age limits (e.g., age 15 [ 25 , 47 ] and age 60 [ 11 , 38 ] years, respectively). Most studies were from the USA ( n = 10; 26%) and the Netherlands ( n = 6; 16%); this result is line with the findings from a review of economic evaluations of workplace mental health interventions [ 48 ]. The remaining studies were from Australia ( n = 4), Japan ( n = 4), South Korea ( n = 3), multiple countries ( n = 4), Brazil ( n = 1), Colombia ( n = 1), Denmark ( n = 1), Finland ( n = 1), Norway ( n = 1), Singapore ( n = 1), and the United Kingdom ( n = 1). Many studies did not specify the setting or industry or state the size of the firm where the study was undertaken (also found elsewhere [ 48 ]); consequently, this information was not included in the data extraction form.

3.3 Measures and Instruments/Tools Used

3.3.1 mental health.

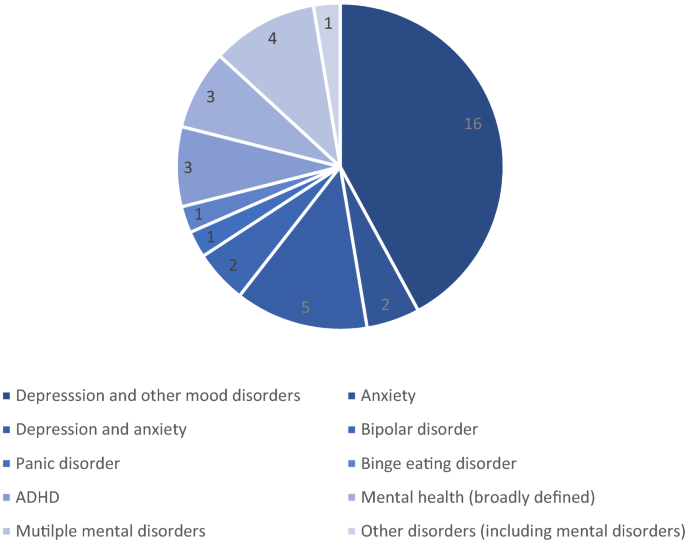

Most studies ( n = 16) examined depression/depressive symptoms, major depressive disorder or other mood disorders (see Fig. 2 ). Two studies examined anxiety and five studied both anxiety and depression. A smaller number of studies examined other disorders—three studies examined attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), two studies focused on bipolar disorder, one examined panic disorder, one studied binge-eating disorder, and one looked at other disorders including mental disorders (depressive symptoms and cognitive function). Three studies looked at mental health broadly speaking (two studies examined poor mental health and another studied common mental disorders). Finally, four studies examined multiple mental disorders (e.g., depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, emotional disorders, substance use disorders, ADHD). Some studies used a binary indicator for the presence/absence of a mental disorder/poor mental health, while other analyses used different aggregate measures of mental illness or psychological distress, based on the number of recorded symptoms.

Studies by mental disorder. ADHD attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

A variety of instruments/tools were used to measure mental health, depending on the disorder. Depression was measured using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6 scale) [ 49 ], Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) depression scale [ 50 ], Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [ 51 ], Short General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) [ 52 ], Major Depression Inventory (MDI) [ 53 ], Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) [ 54 ], and Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5) [ 55 ]. In studies that examined both anxiety and depression ( n = 2), the authors used either the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [ 56 ] or the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) [ 57 ]. In one study [ 42 ], severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms was assessed using the Beck Anxiety Inventory [ 58 ] and the Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology questionnaire [ 59 ], respectively. In another study [ 33 ], mood disorder was measured using the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) [ 60 ]. In one study [ 41 ], ADHD was assessed using the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey [ 61 ]; in another [ 35 ], it was assessed using the WHO Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale [ 62 ]. Panic disorders were measured using the Panic Disorder Severity Scale [ 63 ] in one study [ 16 ].

3.3.2 Lost Productivity

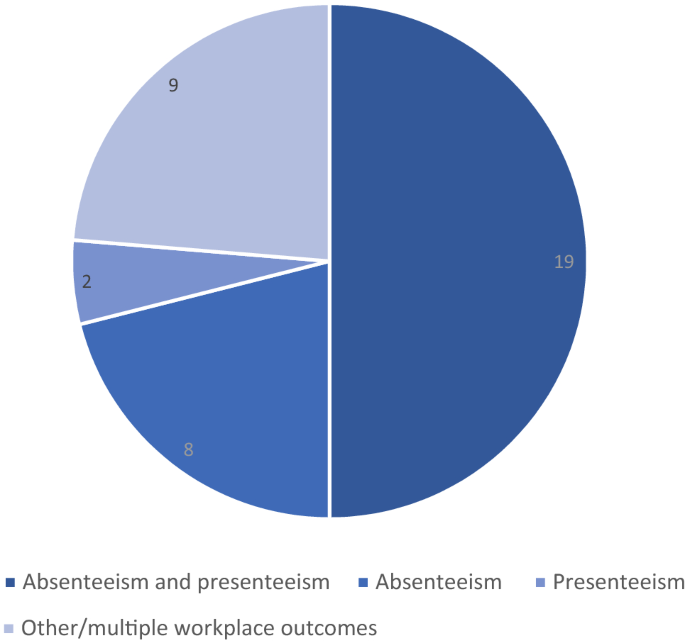

Nineteen studies examined both absenteeism and presenteeism, eight studies examined absenteeism only, two studies examined presenteeism only, and nine examined other or several workplace outcomes, such as employment, absenteeism, presenteeism, workplace accidents/injuries, short- and/or long-term disability, activity impairment and/or job loss (see Fig. 3 ).

Studies by workplace outcome

Five studies used the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire [ 64 ] (Beck et al. [ 27 ], Jain et al. [ 36 ], Able et al. [ 30 ], Asami et al. [ 31 ], Ling et al. [ 44 ]); three used the WHO’s Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HWP) [ 65 ] (Hjarsbech et al. [ 18 ], Woo et al. [ 38 ], Park et al. [ 16 ]) to determine absenteeism and presenteeism. A recent systematic review also found that that the WPAI was most frequently applied in economic evaluations and validation studies to measure lost productivity [ 66 ]. Two studies [ 12 , 20 ] used the Work Limitations Questionnaire [ 67 ]. Other studies used a variety of different instruments to measure lost productivity, such as the Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for Costs Associated with Psychiatric illness (TiC-P) [ 68 ] (Bokma et al. [ 26 ]), the Short-Form Health and Labour Questionnaire [ 69 ] (Bouwmans et al. [ 45 ]), the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO-DAS) [ 70 ] (de Graaf et al. [ 23 ]) and the Endicott Work Productivity Scale [ 71 ] (McMorris et al. [ 33 ]). One study [ 43 ] made use of four work performance measures to examine lost productivity: WPAI [ 64 ], Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ) [ 66 ], Endicott Work Productivity Scale (EWPS) [ 71 ] and Functional Status Questionnaire Work Performance Scale (WPS) [ 72 ].

3.4 Data Sources and Methods

Most studies ( n = 20) employed data collected through surveys/questionnaires, though some used publicly available datasets, such as the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey [ 29 ], the National Comorbidity Survey Replication [ 28 ] and the National Latino and Asian American Study [ 28 ], the US National Health and Wellness Survey [ 44 ], the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey [ 25 , 47 ], and the Singapore Mental Health Study [ 24 ]. One study used administrative claims data [ 32 ]. Three studies made use of linked data, such as Hjarsbech et al. [ 18 ], which linked questionnaires to the Danish National Register of Social Transfer Payments; Erickson et al. [ 43 ], which utilised questionnaires linked to medical records, and Mauramo et al. [ 34 ], which used survey data from the Helsinki Health Study linked to employer's register data on sickness absence. Only one study employed trial data [ 45 ]. Most studies ( n = 29; 76%) employed cross-sectional data; few used longitudinal data ( n = 9; 24%).

3.4.2 Methods

Several studies ( n = 8) used regression analysis to examine the relationship between mental health and lost productivity, namely linear regression [ 11 , 17 ] and logistic regression models [ 25 , 29 , 42 , 45 ]. Two studies employed two-part models, where the first part examined the probability/odds of workers experiencing absenteeism, while the second part modeled the number of hours of absenteeism [ 10 ] or the number of work days missed [ 29 ]. One paper employed Poisson regressions to model the rate of work-lost days (absenteeism) and work-cut days (presenteeism) [ 34 ]. Another study computed Kaplan–Meier survival curves to estimate the mean and median duration of sickness absence due to depressive symptoms [ 40 ], and one estimated a Cox's proportional hazards model to analyse whether and to what extent depressive symptoms at baseline predicted time to onset of first long-term sickness absence during the 1-year follow-up period [ 18 ]. Only one study employed instrumental variables to address the potential endogeneity of the mental illness variable employed [ 28 ] and four employed longitudinal data models [ 13 , 20 , 25 , 47 ].

3.5 Evidence Synthesis

Almost all studies ( n = 36) found a positive (and, many times, a strong) association between the presence of mental illness/disorders or poor mental health and productivity loss measured by absenteeism and/or presenteeism. Nevertheless, there were a few exceptions—one study found that mood disorders were associated with decreased presenteeism (i.e., work performance) but found no significant relationship between mood disorders and absenteeism [ 11 ]. Another study found that individuals with binge-eating disorders reported greater levels of presenteeism and lost productivity than those without but found no effect for absenteeism [ 44 ].

Many studies ( n = 6) on depression examined both absenteeism and presenteeism where the presence of the former was positively associated with the latter (as was the case for studies, which examined only absenteeism and only presenteeism), and the latter was higher among those with higher severity of depression. These findings held in studies examining major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder (though one study found that symptoms of mania or hypomania were not significantly associated with absenteeism) [ 14 ]. Studies examining depression and anxiety (and anxiety alone, including panic disorder) generally examined both absenteeism and presenteeism and found that these disorders were significantly associated with lost productivity. One study found that workers with binge-eating disorder reported greater levels of presenteeism than those without but no differences in absenteeism. All studies on ADHD ( n = 3) examined both absenteeism and presenteeism and found ADHD was associated with more days of missed work and poor work performance. Studies looking at mental health (broadly defined) typically examined absenteeism only, finding a positive relationship between both, though the magnitude of the effect was found to be modest in one study [ 47 ]. Studies examining multiple disorders ( n = 4) also examined both absenteeism and presenteeism. Overall, having a mental disorder was positively associated with lost productivity; however, one study found no significant relationship between mood disorders and alcohol use/dependence and absenteeism [ 11 ].

Many studies ( n = 6) found that higher severity of the disorder or co-occurring mental health conditions was associated with greater productivity loss. For example, Knudsen et al. found that while comorbid anxiety and depression and anxiety alone were significant risk factors for absenteeism, depression alone was not [ 37 ].

Some studies examined outcomes separately for men and women ( n = 5) or examined specific groups ( n = 1). For example, Ammerman et al. examined high-risk, low-income mothers with major depression and found that depression significantly increased the likelihood of absenteeism (i.e., missing workdays) among this group [ 29 ]. However, beyond gender, studies did not report on differences by ethnicity/race and/or age.

Overall, we found that the literature on this topic continues to examine the most common mental disorders (e.g., depression and anxiety) using similar data sources and analysis techniques as the Burton et al. review [ 3 ] (see Table 3 ). However, more recent literature shows that the positive relationship between the presence of mental disorders and lost productivity may not hold in all instances.

4 Discussion

The goal of this review was to provide a comprehensive overview and critical assessment of the most recent literature examining the relationship between mental health and workplace productivity, with a particular focus on data and methods employed. It provides clear evidence that poor mental health is associated with lost productivity, defined as increased absenteeism (i.e., more missed days from work) and increased presenteeism (i.e., decreased productivity at work). However, overall, only three studies were of high quality [ 25 , 28 , 47 ]. Studies with greater rigour and more robust methods, which accounted for unobserved heterogeneity for example, found a similar positive relationship but a smaller effect size [ 25 , 47 ].

Other reviews have also found large significant associations between measures of mental health and lost productivity, such as absenteeism [ 3 , 73 , 74 , 75 ]. For example, Burton et al. [ 3 ] found that depressive disorders were the most common mental health disorder among most workers, with many studies showing a positive association between the presence of mental health conditions and absenteeism, particularly short-term disability absences [ 3 ]. However, we found that studies employing superior methodological study design have shown the strength of the observed association may be smaller than previously thought.

Overall, our findings are in line with those from other reviews [ 73 , 74 , 75 ] and the Burton et al. study [ 3 ]. We too found that the most common disorder examined was depression, followed by depression and anxiety, the most studied workplace outcomes were both absenteeism and presenteeism, and that there was an association between mental disorders and both absenteeism and presenteeism. We found that studies employed a variety of data sources, from data collected from surveys/questionnaires to existing surveys and administrative data. Regression analysis was commonly used to examine the relationship between mental health and lost productivity, though there were some studies where the most appropriate regression model was not used given the outcome examined (e.g., linear regression models were used regardless of the type of outcome examined).

Some studies employed small sample sizes [ 20 , 43 ], which are not representative of the broader population and can thus impact the generalizability of findings, and other studies that did use nationally representative population samples employed cross-sectional designs [ 11 , 42 , 46 ], which can limit causal inference. Therefore, the vast majority did not examine the causal effect of mental health on lost productivity, but rather only the association between the two. A notable exception was Banerjee et al. [ 28 ], who examined the potential endogeneity of the mental illness variable used. Moreover, few studies employed longitudinal data, which can help account for unobserved heterogeneity (that may be correlated with both mental health and lost productivity) and minimise the potential for reverse causality and omitted variable bias; Wooden et al. [ 47 ] and Bubonya et al. [ 25 ] were notable exceptions. Wooden et al. found that the association between poor mental health and the number of annual paid sickness absence days was much smaller once they accounted for unobserved heterogeneity and focused on within-person differences [ 47 ]. For example, the incidence rate ratios for the number of sickness absence days for employed women and men experiencing severe depressive symptoms were 1.31 and 1.38, respectively, in the negative binomial regression models but dropped to 1.10 and 1.13, respectively, once the authors controlled for unobserved heterogeneity through the inclusion of correlated random effects. Thus, it may be that previous research has overstated the magnitude of the association between poor mental health and lost productivity. More studies with rigorous causal inference are required to help strengthen the ability to make informed policy recommendations.

Few studies explored the factors that might explain absenteeism and/or presenteeism due to mental health. Again, the study by Bubonya et al. was a notable exception [ 25 ], providing several important insights on the relationship between mental health and lost productivity. According to the authors, initiatives that limit and help workers manage job stress seem to be the most promising avenue for improving workers’ productivity. Furthermore, the authors found that presenteeism rates among workers with poor mental health were relatively insensitive to work environments, in line with other research from the UK [ 76 ]; consequently, they suggested that developing institutional arrangements that specifically target the productivity of those experiencing mental ill health may prove challenging. These findings are particularly important in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic due to changes in work arrangements and workplaces (e.g., working from home while trying to balance work with home and care responsibilities, hybrid working arrangements, and ensuring workplaces have COVID-19-secure measures in place). This work will be of particular interest to employers and decision makers looking to improve worker productivity.

Most literature examined either depression or anxiety or both, the most common mental disorders. Few studies examined mental disorders such as ADHD, bipolar disorder and eating disorders, and no studies examined schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, personality disorder or suicidal/self-harm behaviour. More work is needed on these mental disorders, which, although less prevalent and thus less studied, are potentially more work disabling (despite already low employment rates for individuals with these conditions) [ 77 , 78 ]. Other research suggests there are important gender differences [ 25 , 28 ]. For example, Bubonya et al. found that increased job control can help reduce absenteeism for women with good mental health, though not for women in poor mental health [ 25 ]. Banerjee et al. found that the impact of poor mental health on the likelihood of being employed and in the labour force is higher for men [ 28 ]. Future research should ensure that gender differences, as well as other differences (e.g., age, industry, job conditions), are examined to ensure tailored polices are developed and implemented.

There is also a need to better understand the extent to which mental illness decreases productivity at work and the mechanisms through which this occurs, as this could help inform the role of employment policy and practices to minimise presenteeism [ 25 ]. Some research suggests that conducive working conditions, such as part-time employment and having autonomy over work tasks, can help mitigate the negative impact of mental health on presenteeism [ 76 ]. Alongside this, it is important to learn more about the dynamics of the relationship between mental illness and worker productivity to understand the trade-offs between presenteeism and absenteeism [ 25 ]. For example, it would be helpful to understand whether policies that incentivise workers with mental ill health to take time off improve overall productivity by reducing presenteeism. None of the studies in this review explored this trade-off. Finally, more rigorous research on this topic would help achieve a better understanding of the overall economic impact of mental disorders.

This review is not without limitations. It only included studies obtained from a few select databases and did not include grey literature, and only one reviewer screened the titles and abstracts (though the purpose was not to undertake a systematic review); however, it examined papers and reports from select websites of interest. Furthermore, this review only focused on the relationship between mental health and lost productivity. Although lost productivity is an important labour market outcome, there are other outcomes that mental health can impact such as labour force participation, wages/earnings, and part-time versus full time employment. Finally, this review only included studies published in English and therefore may have missed other relevant studies. Nonetheless, this review has several strengths. It provides an updated review on this topic, thus addressing a critical gap in the literature, and examined the type of data and databases employed, the methods used, and the existing gaps in the literature, thus providing a more comprehensive overview of the research done to date.

5 Conclusion

This review found clear evidence that poor mental health, typically measured as depression and/or anxiety, was associated with lost productivity, i.e., increased absenteeism and presenteeism. Most studies used survey and administrative data and regression analysis. Few studies employed longitudinal data, and most studies that used cross-sectional data did not account for endogeneity. Despite consistent findings across studies, more high-quality studies are needed on this topic, namely those that account for endogeneity and unobserved heterogeneity. Furthermore, more work is needed to understand the extent to which mental illness decreases productivity at work and the mechanisms through which this occurs, as well as a better understanding of the dynamics of the relationship between mental illness and worker productivity to understand the trade-offs between presenteeism and absenteeism. For example, future research should seek to understand how working conditions and work arrangements as well as workplace policies (e.g., vacation time and leaves of absence) impact presenteeism.

This type of review differs from a systematic review, which seeks to systematically search for, appraise and synthesise existing evidence, often following existing guidelines on the conduct of a review.

Bloom DE, Cafiero ET, Jané-Llopis E, et al. The global economic burden of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Economic Forum; 2011.

Google Scholar

Hamberg-van Reenen HH, Proper KI, van den Berg M. Worksite mental health interventions: a systematic review of economic evaluations. Occup Environ Med. 2012;69:837–45.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Burton WN, Schultz AB, Chen C, Edington DW. The association of worker productivity and mental health: a review of the literature. Int J Workplace Health Manag. 2008;1(2):78–94.

Article Google Scholar

McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R, Brugha T, editors. Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. Leeds: NHS Digital; 2016.

Mental wellbeing at work. Public health guideline [PH22]. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph22 (Accessed 28 July 2021).

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7): e1000097.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Christensen MK, Lim CCW, Saha S, Plana-Ripoll O, Cannon D, Presley F, Weye N, Momen NC, Whiteford HA, Iburg KM, McGrath JJ. The cost of mental disorders: a systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29: e161.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses; 2013. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp .

Uribe JM, Pinto DM, Vecino-Ortiz AI, Gómez-Restrepo C, Rondón M. Presenteeism, absenteeism, and lost work productivity among depressive patients from five cities of Colombia. Value Health Reg Issues. 2017;14:15–9.

Tsuchiya M, Kawakami N, Ono Y, Nakane Y, Nakamura Y, Fukao A, Tachimori H, Iwata N, Uda H, Nakane H, Watanabe M, Oorui M, Naganuma Y, Furukawa TA, Kobayashi M, Ahiko T, Takeshima T, Kikkawa T. Impact of mental disorders on work performance in a community sample of workers in Japan: the World Mental Health Japan Survey 2002–2005. Psychiatry Res. 2012;198(1):140–5.

Toyoshima K, Inoue T, Shimura A, Masuya J, Ichiki M, Fujimura Y, Kusumi I. Associations between the depressive symptoms, subjective cognitive function, and presenteeism of Japanese adult workers: a cross-sectional survey study. Biopsychosoc Med. 2020;14:10.

Suzuki T, Miyaki K, Song Y, Tsutsumi A, Kawakami N, Shimazu A, Takahashi M, Inoue A, Kurioka S. Relationship between sickness presenteeism (WHO-HPQ) with depression and sickness absence due to mental disease in a cohort of Japanese workers. J Affect Disord. 2015;180:14–20.

Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Unützer J, Operskalski BH, Bauer MS. Severity of mood symptoms and work productivity in people treated for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(6):718–25.

Lamichhane DK, Heo YS, Kim HC. Depressive symptoms and risk of absence among workers in a manufacturing company: a 12-month follow-up study. Ind Health. 2018;56(3):187–97.

Park YL, Kim W, Chae JH, Seo OhK, Frick KD, Woo JM. Impairment of work productivity in panic disorder patients. J Affect Disord. 2014;157:60–5.

Johnston DA, Harvey SB, Glozier N, Calvo RA, Christensen H, Deady M. The relationship between depression symptoms, absenteeism and presenteeism. J Affect Disord. 2019;256:536–40.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hjarsbech PU, Andersen RV, Christensen KB, Aust B, Borg V, Rugulies R. Clinical and non-clinical depressive symptoms and risk of long-term sickness absence among female employees in the Danish eldercare sector. J Affect Disord. 2011;129(1–3):87–93.

Hilton MF, Scuffham PA, Vecchio N, Whiteford HA. Using the interaction of mental health symptoms and treatment status to estimate lost employee productivity. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(2):151–61.

Hees HL, Koeter MW, Schene AH. Longitudinal relationship between depressive symptoms and work outcomes in clinically treated patients with long-term sickness absence related to major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;148(2–3):272–7.

Fernandes MA, Ribeiro HKP, Santos JDM, Monteiro CFS, Costa RDS, Soares RFS. Prevalence of anxiety disorders as a cause of workers’ absence. Rev Bras Enferm. 2018;71(suppl 5):2213–20.

Evans-Lacko S, Knapp M. Global patterns of workplace productivity for people with depression: absenteeism and presenteeism costs across eight diverse countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(11):1525–37.

de Graaf R, Tuithof M, van Dorsselaer S, ten Have M. Comparing the effects on work performance of mental and physical disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(11):1873–83.

Chong SA, Vaingankar JA, Abdin E, Subramaniam M. Mental disorders: employment and work productivity in Singapore. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(1):117–23.

Bubonya M, Cobb-Clark DA, Wooden M. Mental health and productivity at work: does what you do matter? Labour Econ. 2017;46:150–65.

Bokma WA, Batelaan NM, van Balkom AJ, Penninx BW. Impact of anxiety and/or depressive disorders and chronic somatic diseases on disability and work impairment. J Psychosom Res. 2017;94:10–6.

Beck A, Crain AL, Solberg LI, Unützer J, Glasgow RE, Maciosek MV, Whitebird R. Severity of depression and magnitude of productivity loss. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(4):305–11.

Banerjee S, Chatterji P, Lahiri K. Effects of psychiatric disorders on labor market outcomes: a latent variable approach using multiple clinical indicators. Health Econ. 2017;26(2):184–205.

Ammerman RT, Chen J, Mallow PJ, Rizzo JA, Folger AT, Van Ginkel JB. Annual direct health care expenditures and employee absenteeism costs in high-risk, low-income mothers with major depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:386–94.

Able SL, Haynes V, Hong J. Diagnosis, treatment, and burden of illness among adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Europe. Pragmat Obs Res. 2014;5:21–33.

Asami Y, Goren A, Okumura Y. Work productivity loss with depression, diagnosed and undiagnosed, among workers in an Internet-based survey conducted in Japan. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57(1):105–10.

Curkendall S, Ruiz KM, Joish V, Mark TL. Productivity losses among treated depressed patients relative to healthy controls. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52(2):125–30.

McMorris BJ, Downs KE, Panish JM, Dirani R. Workplace productivity, employment issues, and resource utilization in patients with bipolar I disorder. J Med Econ. 2010;13(1):23–32.

Mauramo E, Lallukka T, Lahelma E, Pietiläinen O, Rahkone O. Common mental disorders and sickness absence. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(6):569–75.

Kessler RC, Lane M, Stang PE, Van Brunt DL. The prevalence and workplace costs of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in a large manufacturing firm. Psychol Med. 2009;39(1):137–47.

Jain G, Roy A, Harikrishnan V, Yu S, Dabbous O, Lawrence C. Patient-reported depression severity measured by the PHQ-9 and impact on work productivity: results from a survey of full-time employees in the United States. J Occup Environ Med. 2013;55(3):252–8.

Knudsen AK, Harvey SB, Mykletun A, Øverland S. Common mental disorders and long-term sickness absence in a general working population. The Hordaland Health Study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127(4):287–97.

Woo JM, Kim W, Hwang TY, Frick KD, Choi BH, Seo YJ, Kang EH, Kim SJ, Ham BJ, Lee JS, Park YL. Impact of depression on work productivity and its improvement after outpatient treatment with antidepressants. Value Health. 2011;14(4):475–82.

Harvey SB, Glozier N, Henderson M, Allaway S, Litchfield P, Holland-Elliott K, Hotopf M. Depression and work performance: an ecological study using web-based screening. Occup Med (Lond). 2011;61(3):209–11.

Koopmans PC, Roelen CA, Groothoff JW. Sickness absence due to depressive symptoms. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2008;81(6):711–9.

de Graaf R, Kessler RC, Fayyad J, ten Have M, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Borges G, Demyttenaere K, Gasquet I, de Girolamo G, Haro JM, Jin R, Karam EG, Ormel J, Posada-Villa J. The prevalence and effects of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on the performance of workers: results from the WHO World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Occup Environ Med. 2008;65(12):835–42.

Plaisier I, Beekman AT, de Graaf R, Smit JH, van Dyck R, Penninx BW. Work functioning in persons with depressive and anxiety disorders: the role of specific psychopathological characteristics. J Affect Disord. 2010;125(1–3):198–206.

Erickson SR, Guthrie S, Vanetten-Lee M, Himle J, Hoffman J, Santos SF, Janeck AS, Zivin K, Abelson JL. Severity of anxiety and work-related outcomes of patients with anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(12):1165–71.

Ling YL, Rascati KL, Pawaskar M. Direct and indirect costs among patients with binge-eating disorder in the United States. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(5):523–32.

Bouwmans CA, Vemer P, van Straten A, Tan SS, Hakkaart-van RL. Health-related quality of life and productivity losses in patients with depression and anxiety disorders. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(4):420–4.

Buist-Bouwman MA, Ormel J, de Graaf R, de Jonge P, van Sonderen E, Alonso J, Bruffaerts R, Vollebergh WA, ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 Investigators. Mediators of the association between depression and role functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118(6):451–8.

Wooden M, Bubonya M, Cobb-Clark D. Sickness absence and mental health: evidence from a nationally representative longitudinal survey. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2016;42(3):201–8.

PubMed Google Scholar

de Oliveira C, Cho E, Kavelaars R, Jamieson M, Bao B, Rehm J. Economic analyses of mental health and substance use interventions in the workplace: a systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):893–910.

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32:959–76.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401.

Goldberg D, Hillier V. A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med. 1979;9(1):139–45.

Bech P, Rasmussen N-A, Olsen LR, Noerholm V, Abildgaard W. The sensitivity and specificity of the Major Depression Inventory, using the Present State Examination as the index of diagnostic validity. J Affect Disord. 2001;66:159–64.

Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62.

Berwick DM, Murphy JM, Goldman PA, Ware JE Jr, Barsky AJ, Weinstein MC. Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Med Care. 1991;29(2):169–76.

Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety And Depression Scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:29.

Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE, Babor TF, Burke J, Farmer A, Jablenski A, Pickens R, Regier DA, et al. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview. An epidemiologic Instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(12):1069–77.

Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893–7.

Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, Jarrett RB, Trivedi MH. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychol Med. 1996;26(3):477–86.

Hirschfeld RM. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire: a simple, patient-rated screening instrument for bipolar disorder. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;4(1):9–11.

Kessler RC, Haro JM, Heeringa SG, et al. The World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Epidemiol Psychiatr Soc. 2006;15:161–6.

Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, Demler O, Faraone S, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Jin R, Secnik K, Spencer T, Ustun TB, Walters EE. The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med. 2005;35(2):245–56.

Shear MK, Brown TA, Barlow DH, Money R, Sholomskas DE, Woods SW, et al. Multicenter collaborative panic disorder severity scale. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(11):1571–5.

Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353–65.

Kessler RC, Barber C, Beck A, Berglund P, Cleary PD, McKenas D, Pronk N, Simon G, Stang P, Üstün TU, Wang P. The World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ). J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45(2):156–74.

Hubens K, Krol M, Coast J, Drummond MF, Brouwer WBF, Uyl-de Groot CA, Hakkaart-van RL. Measurement instruments of productivity loss of paid and unpaid work: a systematic review and assessment of suitability for health economic evaluations from a societal perspective. Value Health. 2021;24(11):1686–99.

Lerner D, Amick BC 3rd, Rogers WH, Malspeis S, Bungay K, Cynn D. The Work Limitations Questionnaire. Med Care. 2001;39(1):72–85.

Hakkaart-Van Roijen L. Manual. Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for Costs associated with Psychiatric Illness (TiC-P adults); 2010. http://www.bmg.eur.nl/english/imta/publications/questionnaires_manuals .

van Roijen L, Essink-Bot M, Koopmanschap MA, et al. Labor and health status in economic evaluation of health care. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1996;12(3):405–15.

Janca A, Kastrup M, Katschnig H, López-Ibor JJ Jr, Mezzich JE, Sartorius N. The World Health Organization Short Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO DAS-S): a tool for the assessment of difficulties in selected areas of functioning of patients with mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1996;31(6):349–54.

Endicott J, Nee J. Endicott Work Productivity Scale (EWPS): a new measure to assess treatment effects. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33(1):13–6.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Jette AM, Davies AR, Cleary PD, Calkins DR, Rubenstein LV, Fink A, Kosecoff J, Young RT, Brook RH, Delbanco TL. The Functional Status Questionnaire: reliability and validity when used in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 1986;1(3):143–9.

Duijts SFA, Kant I, Swaen GMH, van den Brandt PA, Zeegers MPA. A meta-analysis of observational studies identifies predictors of sickness absence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(11):1105–15.

Darr W, Johns G. Work strain, health, and absenteeism: a meta-analysis. J Occup Health Psychol. 2008;13(4):293–318.

Lerner D, Henke RM. What does research tell us about depression, job performance, and work productivity? J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(4):401–10.

Bryan ML, Bryce AM, Roberts J. Presenteeism in the UK: effects of physical and mental health on worker productivity; 2020; SERPS no. 2020005. ISSN 1749-8368. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/media/12544/download .

Cook JA. Employment barriers for persons with psychiatric disabilities: update of a report for the President’s Commission. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(10):1391–405.

Luciano A, Meara E. Employment status of people with mental illness: national survey data from 2009 and 2010. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(10):1201–9.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Kath Wright for her help with the search strategy.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Health Economics, University of York, York, UK

Claire de Oliveira & Rowena Jacobs

Hull York Medical School, Hull and York, UK

Claire de Oliveira, Makeila Saka & Lauren Bone

Institute for Mental Health Policy Research, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, Canada

Claire de Oliveira

Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Claire de Oliveira .

Ethics declarations

No funding was received for this research.

Conflict of interest

None to declare.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Consent for publication (from patients/participants), availability of data and material, code availability, author contributions.

CdO and RJ conceived and developed the protocol study. LB undertook the search and screened all titles and abstracts. MS extracted the data. CdO and RJ adjudicated any discrepancies in the full-text review. CdO wrote the first draft of the manuscript. CdO and RJ supervised the project. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the manuscript. All authors take sole responsibility for the content.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 42 KB)

Rights and permissions.

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

de Oliveira, C., Saka, M., Bone, L. et al. The Role of Mental Health on Workplace Productivity: A Critical Review of the Literature. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 21 , 167–193 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-022-00761-w

Download citation

Accepted : 22 August 2022

Published : 15 November 2022

Issue Date : March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-022-00761-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

More From Forbes

An employer’s guide to mental health awareness in the workplace.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

The stresses and pressure at the office or working remotely can be a cause of the deterioration of ... [+] employees’ mental health and emotional wellbeing.

May is National Mental Health Awareness Month, and creates the opportunity for organizations to bring mental, emotional and physical wellbeing to the forefront. It facilitates in helping to reduce any stigmas surrounding behavioral health issues and highlight how mental illness can impact the workplace, society, families and others.

Stress And Anxiety In The Workplace