Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

A scoping review of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex (LGBTQI+) people’s health in India

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Centre for Sexuality and Health Research and Policy (C-SHaRP), Chennai, India, The Humsafar Trust, Mumbai, India

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, VOICES-Thailand Foundation, Chiang Mai, Thailand

Roles Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft

Affiliation Centre for Sexuality and Health Research and Policy (C-SHaRP), Chennai, India

Roles Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – original draft

Affiliation The Humsafar Trust, Mumbai, India

Roles Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft

Roles Formal analysis, Investigation

Roles Data curation, Project administration

Affiliation VOICES-Thailand Foundation, Chiang Mai, Thailand

- Venkatesan Chakrapani,

- Peter A. Newman,

- Murali Shunmugam,

- Shruta Rawat,

- Biji R. Mohan,

- Dicky Baruah,

- Suchon Tepjan

- Published: April 20, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001362

- Reader Comments

Amid incremental progress in establishing an enabling legal and policy environment for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer-identified people, and people with intersex variations (LGBTQI+) in India, evidence gaps on LGBTQI+ health are of increasing concern. To that end, we conducted a scoping review to map and synthesize the current evidence base, identify research gaps, and provide recommendations for future research. We conducted a scoping review using the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology. We systematically searched 14 databases to identify peer-reviewed journal articles published in English language between January 1, 2010 and November 20, 2021, that reported empirical qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods data on LGBTQI+ people’s health in India. Out of 3,003 results in total, we identified 177 eligible articles; 62% used quantitative, 31% qualitative, and 7% mixed methods. The majority (55%) focused on gay and other men who have sex with men (MSM), 16% transgender women, and 14% both of these populations; 4% focused on lesbian and bisexual women, and 2% on transmasculine people. Overall, studies reported high prevalence of HIV and sexually transmitted infections; multilevel risk factors for HIV; high levels of mental health burden linked to stigma, discrimination, and violence victimization; and non-availability of gender-affirmative medical care in government hospitals. Few longitudinal studies and intervention studies were identified. Findings suggest that LGBTQI+ health research in India needs to move beyond the predominant focus on HIV, and gay men/MSM and transgender women, to include mental health and non-communicable diseases, and individuals across the LGBTQI+ spectrum. Future research should build on largely descriptive studies to include explanatory and intervention studies, beyond urban to rural sites, and examine healthcare and service needs among LGBTQI+ people across the life course. Increased Indian government funding for LGBTQI+ health research, including dedicated support and training for early career researchers, is crucial to building a comprehensive and sustainable evidence base to inform targeted health policies and programs moving forward.

Citation: Chakrapani V, Newman PA, Shunmugam M, Rawat S, Mohan BR, Baruah D, et al. (2023) A scoping review of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex (LGBTQI+) people’s health in India. PLOS Glob Public Health 3(4): e0001362. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001362

Editor: Prashanth Nuggehalli Srinivas, Institute of Public Health Bengaluru, INDIA

Received: November 19, 2022; Accepted: March 18, 2023; Published: April 20, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Chakrapani et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: This work was financially supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada in the form of a grant (Partnership Grant, 895–2019-1020 [MFARR-Asia]) awarded to PAN. This work was also financially supported by the DBT/Wellcome Trust India Alliance Senior Fellowship (IA/CPHS/16/1/502667) in the form of salary for VC. The specific roles of these authors are articulated in the ‘author contributions’ section. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have read the journal’s policy and have the following competing interests: VC was employed by by the DBT/Wellcome Trust India Alliance Senior Fellowship at the time of this study. PAN serves on the Editorial Board for PLOS Global Public Health. This does not alter our adherence to PLOS Global Public Health policies on sharing data and materials.

Introduction

The right to the highest attainable standard of health is both universal and fundamental in international law [ 1 ]. This is enshrined in Article 12 [ 2 ] of the Convention on Social , Economic , and Cultural Rights and underlies United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG-3), which promises “Health for All” by 2030 and that “no one will be left behind.” This includes lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer identified, and people with intersex variations (LGBTQI+), who are entitled to the same standard of health as everyone else [ 3 ].

Despite the promise of the SDGs, evidence from across the globe suggests that LGBTQI+ health consistently lags behind that of the general public. Systematic and scoping reviews on health and healthcare access among LGBTQI+ people in high-income countries have shown that these populations continue to face disproportionate physical and mental health burdens in contrast to heterosexual populations [ 4 – 9 ]. For example, global reviews and large-scale studies have documented high levels of problematic alcohol use [ 10 ], sexualized drug use [ 11 ], mental health problems [ 4 , 12 ], and high rates of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [ 13 – 15 ] among various LGBTQI+ subpopulations. Consistent with the minority stress model [ 16 ], many of these poor health outcomes are associated with societal stigma, discrimination, and violence, and systemic barriers in access to health services experienced by LGBTQI+ individuals [ 9 , 17 , 18 ].

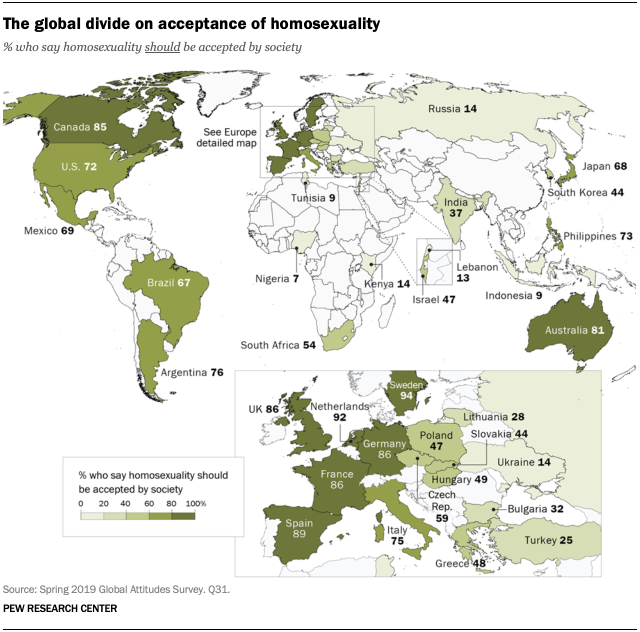

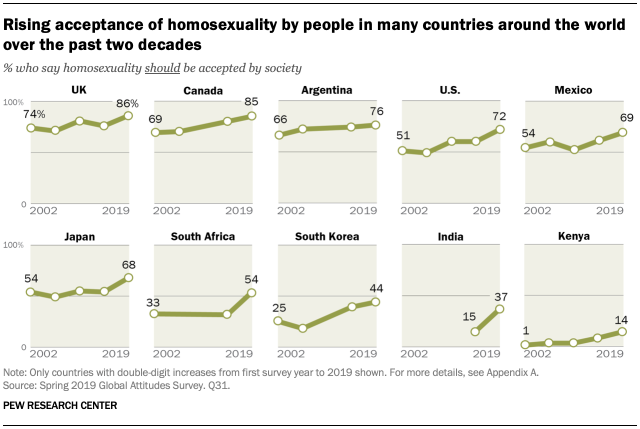

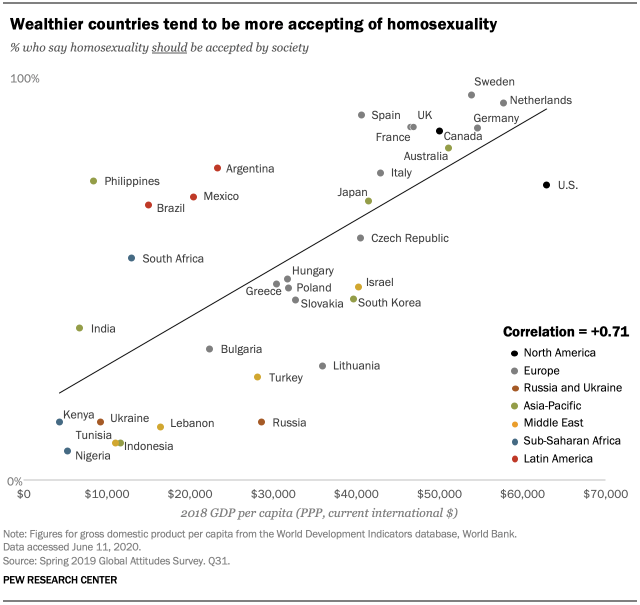

Increasing recognition of health issues and disparities faced by LGBTQI+ people in the context of advances in LGBTQI+ rights movements globally have contributed to an evolving legal and policy environment that is becoming more supportive of LGBTQI+ rights, and more attuned to addressing LGBTQI+ health disparities and discrimination [ 19 ]. These advances in the recognition of LGBTQI+ rights have concomitantly contributed to increasing awareness of the need for research evidence to meaningfully implement this policy shift. Population-specific data are sorely needed to document gaps, disparities, and progress in LGBTQI+ health over time, as recognized by numerous bodies including the World Bank and UNDP; both have called for more attention and investment in research on LGBTQI+ health [ 20 ]. This trend is evident in India where the decriminalization of adult consensual same-sex relationships (2018) [ 21 ] and the enactment of the Transgender Persons Protection of Rights Act (2019) [ 22 ] have recently emerged in rapid succession. The latter act was designed, among other things, to support and promote the delivery of non-discriminatory and gender-affirmative health services to transgender people. Subsequently, India’s Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment’s expert committee on issues related to transgender persons has called for research evidence to design interventions to improve the health of transgender people [ 23 ].

We are aware of no overview and thorough mapping of the evidence base on LGBTQI+ health in India. A few published reviews of LGBTQI+ health in India have focused on specific topics, such as HIV research among MSM or mental health issues among LGBTQI+ individuals [ 24 – 26 ]. To address the fragmented nature of current research knowledge, we conducted a scoping review to synthesize the evidence on LGBTQI+ health in India. The aim of this review was to characterize the breadth of published research on LGBTQI+ health in India and identify gaps in the evidence base, to provide recommendations for future research, and to synthesize existing evidence to inform health policies and interventions to advance LGBTQI+ health.

We used the scoping review framework initially proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [ 27 ] and advanced by the Joanna Briggs Institute [ 28 ]. The key steps involved: (1) identifying the research questions; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection using a pre-defined set of inclusion and exclusion criteria; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results.

Research questions

The specific questions guiding this review were: (1) What are the peer-reviewed literature sources available on LGBTQI+ health in India?; (2) What health problems and conditions are reported among LGBTQI+ people?; and (3) What are the gaps in the available evidence on LGBTQI+ health in India? We conceptualized health problems and conditions broadly, including physical and mental health problems and conditions commonly addressed in the research with LGBTQI+ populations, such as HIV, depression, anxiety, and problematic alcohol use, as well as their social determinants, including stigma, discrimination, violence, and access to care.

Identifying studies from academic databases

As the first comprehensive review of a broad range of health research among LGBTQI+ people across the vast geography and population of India, we limited our search to academic peer-reviewed journal articles. A literature search was conducted using the following academic databases: Medline, Education Resources Information Centre (ERIC), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Public Affairs Information Service Index (PAIS Index), Bibliography of Asian Studies, EconLit, Education Source, Social Work Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, PsychInfo, LGBTLife, Gender Studies, HeinOnline, ProQuest Thesis, Worldwide Political Science Abstracts, and Child and Adolescent Development. Search strings previously validated for LGBT+ populations [ 29 ] were used for identifying relevant articles. Search strings were customized to account for the unique syntax of each database surveyed (see S1 Appendix ). We added relevant Indian LGBTQI+ terminology, including indigenous sexual role-based identity terms, such as kothi (feminine same-sex attracted males, primarily receptive sexual role), panthi (masculine and insertive role) and double-decker (both insertive and receptive role). We also searched for indigenous trans identities, such as hijras, thirunangai, jogappas, mangalmukhi, jogti hijras, and shivshaktis; however, as hijras was the only Indian language term used for trans identity in the article titles and abstracts, we used English language terms, such as trans men, trans women, trans person, and transgender. To delimit the results geographically, we added the term “India*” to all search strings. The searches from each database were documented, duplicates were eliminated, and citations were imported to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne) for abstract and full-text screening.

Study selection

Studies were selected according to pre-defined inclusion criteria. Studies must have been: 1) published between January 1, 2010 and November 20, 2021; conducted among LGBTQI+ people in India; 3) written in English; 4) peer reviewed; and 5) report primary data (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods). Two independent reviewers first screened the titles and abstracts for inclusion. In the case of discrepancies, a third reviewer was consulted to reach consensus. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were screened using a similar process. We selected the time frame to focus on recent articles relevant to current public health programs and policies in India, in order to identify extant research gaps and inform the future research agenda. Additionally, the third phase of India’s National AIDS Control Programme (NACP-III), launched in late 2009, explicitly addressed targeted HIV interventions for men who have sex with men and transgender women, which brought national attention to the health issues of sexual and gender minority populations.

Charting, collating and summarizing the results

The following data were extracted for analysis: year of publication, study location, sample size, study population, objectives, design, methodology (qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods) and key findings. We summarized the results using frequencies, and thematic analysis and synthesis [ 28 ]. Studies were grouped by key themes that emerged from the synthesis: prevalence of HIV and STIs, and risk factors; stigma, discrimination and violence, and health impact; access to health services; interventions to improve health outcomes among LGBTQI+ populations; new HIV prevention technologies and their acceptability; and under-represented LGBTQI+ populations.

The search strategy yielded 2,326 sources after removing duplicates. Screening of the titles and abstracts yielded 588 articles included in full-text review. Of these, 177 peer-reviewed articles met the a priori eligibility criteria and were included in the scoping review ( Fig 1 ). We extracted study characteristics and key findings for the included articles ( Table 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001362.g001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001362.t001

Study characteristics

Of the 177 articles, the majority (59%; n = 105) were published from 2016 onward ( Fig 2 ). In terms of methodology, 62% were quantitative, 31% qualitative, and 7% mixed methods studies. A majority (55%; n = 98) of studies were conducted among MSM, 16% (n = 28) among TGW, and 14% (n = 25) among both MSM and TGW ( Fig 3 ). Seven studies (4%) were conducted among lesbian or bisexual women, five (3%) among LGBTQI+ people as a whole, and two each among transmasculine people, and people with intersex variations.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001362.g002

HCP, healthcare professional; LGBT, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender; MSM, men who have sex with men; TGW, transgender women.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001362.g003

Nearly half (47%; n = 84) of the studies were conducted in four (of 28) Indian states—Maharashtra (n = 30), Tamil Nadu (n = 23), Karnataka (n = 19) or Andhra Pradesh (n = 12), with the majority of these in state capitals—Mumbai, Chennai, Bangalore, or Hyderabad. Over a third (36%; n = 65) of the studies were conducted in multiple Indian states.

Overall, 77% of studies (n = 137/177) reported sources of funding support, and 12% (n = 21) reported not receiving any specific funding; 11% (n = 19) did not report sources of funding. Of those studies that reported a funding source, the majority (72%; n = 99/137) were foreign sources (largely from the U.S. National Institutes of Health [NIH] and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation); 12% (n = 17) were Indo-U.S. collaborative research projects funded jointly by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and NIH. Twenty studies (15%) received primary funding from the government of India (Indian Council of Medical Research [ICMR] and the National AIDS Control Organization [NACO]) and other Indian institutions.

HIV/STI prevalence and risk factors

Thirty-seven percent (n = 65) of the articles focused on reporting STI/HIV prevalence estimates [ 30 – 47 ] and correlates of HIV-related risk behaviors [ 48 – 94 ] among MSM and TGW ( Fig 4 ). In the 18 studies [ 30 – 47 ] that reported HIV and STI prevalence estimates among MSM and TGW, nine [ 31 – 33 , 37 , 39 – 42 , 45 ] were conducted in clinical settings, six [ 30 , 34 , 35 , 38 , 43 , 46 ] in community settings, and three [ 36 , 44 , 47 ] in both clinical and community settings. Of these 18 studies, eight [ 30 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 40 , 43 , 45 , 46 ] reported HIV/STI prevalence and risk factors among MSM, three [ 36 , 39 , 44 ] human papillomavirus (HPV) prevalence among MSM living with HIV, and three [ 31 , 33 , 45 ] reported prevalence of perianal dermatoses, HPV and other STIs (such as syphilis, chlamydia and gonorrhea) among MSM. Two studies [ 38 , 47 ] reported correlates of HIV incidence among MSM, with one study each reporting Hepatitis C prevalence among MSM living with HIV [ 42 ], and one study the prevalence of herpes [ 45 ].

LB, lesbian and bisexual.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001362.g004

Overall, HIV prevalence among MSM ranged from 3.8% to 23.0% across different study sites. Among MSM, HPV/genital warts (23.0% to 95.0%), syphilis (0.8% to 11.9%), HSV/genital herpes (7.1 to 32.0%), and genital molluscum contagium (9.6%) were the most commonly reported STIs [ 30 , 31 , 33 , 34 , 36 , 37 , 39 , 40 , 42 , 45 ]. One study [ 42 ] reported Hepatitis-C prevalence among MSM as 1.3%. Syphilis rates tended to be higher among single MSM (8.3%) than married MSM (1.0%) [ 35 ]. In a study [ 32 ] conducted among 84 TGW who attended STI clinics in Pune, HIV prevalence was 45.2%.

Forty-seven articles [ 48 – 94 ] reported correlates of HIV-related risk among MSM and TGW. Among MSM, significant correlates of HIV risk behaviors/indicators such as condomless sex [ 48 – 50 , 58 , 64 , 77 , 78 , 92 , 93 ], infrequent HIV testing [ 60 , 65 , 72 , 74 ], and HIV/STI positivity [ 48 , 51 , 55 , 79 ] were low literacy and unemployment [ 48 , 76 , 77 ], alcohol and/or drug use [ 54 , 60 , 64 , 65 , 79 , 90 , 93 ], engagement in sex work [ 49 , 60 , 61 , 65 , 67 , 68 , 75 , 76 , 78 ], higher number of male sexual partners [ 48 – 50 , 53 , 56 , 72 , 74 ], early age of sexual debut [ 93 ], and low HIV risk perception [ 60 , 65 , 72 , 74 ]. Six of the 47 articles included data on TGW; five of these [ 79 , 81 , 84 , 87 , 89 ] did not provide details on correlates of HIV risk behaviors, with one study [ 94 ] reporting that having a male regular partner was associated with HIV seropositivity.

Stigma, discrimination, and violence, and health impacts

Over one-fourth of the articles (27%; n = 48) [ 95 – 142 ] reported on stigma, discrimination, violence, and their associations with physical and mental health. Among these, 16 articles focused on stigma-related aspects of LGBTQI+ health [ 96 , 100 – 102 , 109 , 110 , 112 , 114 , 119 , 124 – 126 , 129 , 132 , 137 , 140 ], 3 on violence [ 97 , 103 , 118 ], 17 on mental health and its correlates, such as quality of life [ 95 , 99 , 105 , 106 , 108 , 111 , 115 , 123 , 127 , 128 , 130 , 131 , 135 , 136 , 138 , 139 , 142 ], two on resilience [ 122 , 133 ] and one article each on coping skills [ 141 ] and promoting LGBTQI+ acceptance [ 134 ]. Three articles reported on stress [ 116 ], perceived psychological impact [ 120 ] and violence [ 121 ] associated with Section-377 of the Indian Penal Code, which until September 2018 criminalised adult consensual same-sex relationships.

Several studies highlighted various types of stigma and discrimination experienced by MSM and TGW, which include perceived stigma, felt normative stigma, HIV-related stigma, family-enacted stigma, gender non-conformity stigma, and internalized stigma [ 96 , 100 , 101 , 109 , 124 – 126 , 129 , 132 , 138 ], gender discrimination, workplace discrimination [ 137 , 139 ] and polyvictimization [ 140 ]. Perpetrators of discrimination and violence against MSM and TGW, including those living with HIV, included peers, sexual partners, family members, healthcare providers, and police [ 98 , 102 , 103 , 109 , 112 , 118 , 119 , 129 , 130 , 137 , 139 ]. Fear of discrimination and suboptimal care [ 112 ] or refusal of care [ 109 ] prevented some persons from disclosing their sexual or gender identity to healthcare providers.

Fifteen studies [ 98 , 99 , 107 – 109 , 112 , 115 , 125 , 127 – 130 , 137 , 139 , 140 ] indicated that stigma and discrimination contribute to depression and other negative mental health outcomes, such as suicidal ideation or attempts, among sexual and gender minorities. Two studies documented a high prevalence of mental health issues among MSM: depression (29% to 45%), anxiety (24% to 40%), suicidal ideation (45% to 53%), suicide attempts (23%), substance abuse (28%) including alcohol dependence (15% to 22%) [ 95 , 130 ]. Similarly, among TGW, high levels of depression (43%), problematic alcohol use (37%) [ 108 ], anxiety (39%), depression (21%), suicide risk (75.8%) [ 136 ] and violence (52%) [ 139 ] were reported. Three studies with MSM [ 99 , 108 , 109 , 115 ] and one with MSM and TGW [ 108 ] reported psychosocial syndemics, that is, co-occurring psychosocial conditions such as problematic alcohol use and internalized homonegativity, and their synergistic impact on HIV risk. The COVID-19 pandemic was also addressed as exacerbating psychological distress among LGBTQI+ people [ 125 , 131 ].

Several studies addressed resilience, coping, and social support. A few studies documented various types of social support and other resilience resources available to MSM and TGW [ 107 , 109 , 117 ], with one study reporting moderate or high levels of resilience among 72% of TGW [ 122 ]. In terms of coping with adversity, MSM and TGW reported supportive roles of peers, NGOs [ 109 ], family, friends and partners [ 107 ], and gharanas (‘clans’ or houses of hijra-identified trans people) [ 127 ]. Some MSM and TGW reported strategies to prevent violence, discrimination and psychological distress, which included bribing police, running away from unsafe places and persons, and negotiating condom use during forced sex encounters [ 109 ], hiding sexual identities [ 103 ], denial [ 123 ], and behavioral disengagement [ 141 ]. One study documented positive coping strategies among older transgender people, such as spirituality, hope, and acceptance of gender dissonance [ 125 ]. In a few studies, social support and resilient coping strategies were identified as predictors of HIV risk [ 108 ] or mediators and moderators of the effects of discrimination on HIV risk or depression [ 110 ]. A resilience-based psychosocial intervention that integrated counselling was found to be effective in reducing HIV risk among MSM, with self-esteem and depressive symptoms mediating this effect [ 133 ]. A community-based theatre intervention was identified as effective in improving positive attitudes and knowledge, and promoting acceptance and solidarity towards LGBTQI+ communities among young adult heterosexual audiences [ 134 ].

Access to services: HIV/STIs and gender-affirmative procedures

In total, 22 studies [ 143 – 164 ]—10 quantitative [ 143 , 145 , 146 , 148 – 153 , 156 ] and 12 qualitative [ 144 , 147 , 154 , 155 , 157 – 164 ]—investigated access to HIV/STI services, gender transition services, and other clinical services. Four of these studies focused on HIV testing [ 145 , 148 , 150 , 154 ] and four [ 144 , 148 , 156 , 162 ] on antiretroviral treatment (ART) access and uptake among MSM and TGW living with HIV. Two studies [ 152 , 153 ] addressed the HIV care continuum and linkages to care, three [ 147 , 157 , 158 ] challenges in accessing HIV testing, treatment and care services among MSM and TGW. Five studies focused on access to healthcare and support services for TGW: access to gender transition services [ 154 ], barriers to dental [ 150 ] and eye care [ 160 ], gender-affirmative technologies [ 159 ], and welfare schemes for TGW [ 161 ].

In relation to HIV testing among MSM, quantitative studies [ 146 , 149 , 151 ] reported that a majority of those recruited through community-based organizations (CBOs) or public sex environments were tested for HIV (61% to 86%) [ 146 , 151 ], in contrast to MSM recruited through online social networking sites (47%) [ 149 ]. Factors such as high literacy levels, being 25 to 34 years old, engagement in sex work, and exposure to HIV intervention programs were associated with higher rates of HIV testing. Qualitative studies [ 147 , 155 ] on HIV testing among MSM and TGW in two cities highlighted barriers such as HIV stigma and discrimination in healthcare settings and fears of adverse social consequences of testing HIV positive, and facilitators such as access to outreach programs operated by CBOs/NGOs, and accurate HIV risk perception.

Four studies (2 qualitative [ 144 , 162 ] and 2 quantitative [ 148 , 156 ]) conducted among MSM and TGW living with HIV reported that multilevel barriers prevented or significantly delayed access to free ART: the qualitative studies reported support from healthcare providers and peers as facilitators of ART adherence, while the quantitative studies [ 148 , 156 ] indicated that 76% (n = 65/85) were on ART and 48% of these (n = 31/65) reported nonadherence [ 148 ]. Those who were younger and who had negative beliefs about ART were less likely to be adherent [ 148 ]. Low levels of knowledge, negative perceptions about ART, and ART nonadherence were significantly associated with lower levels of viral suppression [ 156 ].

In relation to access to gender-affirmative medical care, a qualitative study [ 154 ] reported a near-total absence of gender-affirmative hormone therapy and surgeries in public hospitals. Among three qualitative studies on challenges in accessing HIV testing and treatment services among MSM and TGW, two [ 157 , 158 ] reported challenges faced by MSM and TGW in accessing HIV and gender transition-related services in the time of COVID-19.

Interventions to improve health outcomes among LGBTQI+ populations

Eleven articles [ 165 – 175 ] focused on health-related interventions, especially in relation to HIV prevention, of which 10 were exclusively conducted with MSM. Six of the 12 studies were pilot studies, including four pilot RCTs [ 167 , 171 , 173 , 175 ]. Two articles reported qualitative formative research studies to design counselling-based [ 166 ] and mobile phone-based interventions [ 170 ]. Studies of interventions to increase condom use or HIV testing utilized diverse modalities, such as face-to-face risk reduction counseling [ 167 ], provision of community-friendly services [ 168 ], virtual counseling [ 165 ], internet-based [ 175 ] and mobile phone-based messages [ 171 ], and motivational interviewing techniques [ 173 , 174 ]. Other intervention studies used video-based technologies such as mobile game-based learning for peer education [ 172 ], and a video-based counseling session [ 165 ].

New HIV prevention technologies and their acceptability

Overall, 18 studies [ 176 – 193 ] (11 quantitative, 7 qualitative) focused on new HIV prevention technologies, including oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) [ 176 , 177 , 182 , 184 , 187 – 190 , 192 , 193 ], future HIV vaccines [ 178 – 181 , 183 ] and rectal microbicides [ 185 ], as well as medical male circumcision [ 186 ], and oral HIV self-testing [ 191 ].

Of the ten articles on PrEP, eight examined acceptability or willingness to use PrEP among MSM and TGW; one explored the impact of prioritizing PrEP for MSM [ 184 ], and one compared the cost-effectiveness of offering PrEP to MSM with semiannual HIV testing as opposed to WHO-recommended 3-month testing [ 192 ]. Quantitative studies [ 176 , 177 , 188 – 190 , 193 ] reported generally high willingness to use PrEP among MSM and TGW despite low levels of awareness. Qualitative studies [ 183 , 188 ] reported factors associated with PrEP uptake, including perceived effectiveness in serodiscordant relationships, providing protection in cases of forced sex encounters, ability to use covertly, ability to have sex without condoms, and anxiety-less sex; barriers included PrEP stigma, fear of disclosure to one’s family or partners/spouse, and being labelled as HIV-positive or ‘promiscuous’ by peers. A mathematical modelling study [ 184 ] in Bangalore reported that PrEP could prevent a substantial proportion of infections among MSM (27% of infections over 10 years, with 60% coverage and 50% adherence).

Of the 5 studies on future HIV vaccine acceptability [ 178 – 181 , 183 ], two [ 178 , 180 ] assessed willingness to participate (WTP) in hypothetical HIV vaccine trials among MSM; one [ 179 ] explored mental models of candidate HIV vaccines and clinical trials; and two [ 181 , 183 ] assessed frontline health service providers’ perspectives on HIV vaccine trials and their likelihood of recommending HIV vaccines to MSM populations.

Underrepresented LGBTQI+ populations: Sexual minority women, transmasculine people and people with intersex variations

Sexual minority women..

Seven studies (4%) focused on sexual minority women [ 194 – 200 ], while two additional studies [ 201 , 202 ] included sexual minority women as part of a larger sample. Among the seven studies, most focused on romantic relationships, such as communication and prioritization in relationships [ 199 ], difficulties in maintaining relationships [ 196 ], understanding of intimacy [ 197 , 198 ], and lack of legal recognition of same-gender romantic partnerships [ 198 ]. One study [ 197 ] used a collaborative ethnographic approach to capture the understanding of community and activism from the perspectives of “women loving women” which had indirect connections to mental health. Another study [ 200 ] documented resilience sources (for example, self-confidence, optimism) used by sexual minority women to cope with major stressors.

The sexual health of sexual minority women was explored in two studies [ 194 , 198 ]. One used photo-elicitation interviews and a survey to explore health behaviors and concerns [ 194 ], reporting that a majority of sexual minority women were not accessing preventive healthcare services: 36% reported having been screened for breast cancer and 14% for cervical cancer, and only 20% had ever been tested for STIs. The other study [ 198 ] reported lack of knowledge regarding STIs and difficulty in identifying LGBTQ-friendly service providers as major barriers to accessing preventive services.

Transmasculine people.

Two studies (1%) [ 203 , 204 ] focused on transmasculine people’s health: one [ 203 ] documented challenges in negotiating gender identity in various spaces, such as family, educational settings, workplace and neighborhoods; and one [ 204 ] reported that a substantially higher proportion of transmasculine persons (36.3%) attempted suicide when compared with transfeminine persons (24.7%).

People with intersex variations.

Among the two studies (1%) [ 205 , 206 ] that focused on people with intersex variations, one [ 205 ] examined how healthcare professionals decide on gender assignment of intersex children, and the other study [ 206 ] documented the social stigma faced by people with intersex variations and their families. Findings from both of these studies highlighted that gender assignment decisions are influenced by sociocultural factors: parents of intersex children preferred a male gender assignment possibly because of the social advantages of growing up as a male in a patriarchal society.

This scoping review of a decade of peer-reviewed research on the health of LGBTQI+ people in India demonstrates a trend of increased publications addressing the health of sexual and gender minorities; however, it also identifies substantial gaps in the research—in terms of focal populations, geographical coverage, health conditions, and methods. Overall, this review demonstrates a predominant research focus on HIV and HIV-related risk behaviors among MSM and TGW populations; of these studies, a small subset were intervention studies aiming to improve the health of MSM and TGW. Notably, this review reveals the near complete omission of research on the health of sexual minority women—less than 4% of the studies identified. And amid the substantial focus on transgender women, largely in the context of HIV, scant research addressed the health of transmasculine people.

From a methodological perspective, among the quantitative studies that constituted the majority of the research, most were cross-sectional and descriptive in nature; few studies used longitudinal designs or mixed methods approaches, with very few intervention trials. The inclusion of a substantial proportion of qualitative and mixed methods studies, however, suggests a strength in the potential for characterizing the lived experiences of diverse LGBTQI+ people and experiences in the context of health disparities and challenges in healthcare access. Nevertheless, these too were dominated by a focus on MSM and TGW. A scoping review on LGBT inclusion in Thailand similarly reported substantial underrepresentation of lesbian and bisexual women, and transmasculine people, in the peer-reviewed literature [ 6 ].

The persistent and substantial gaps identified, even amid the overall increase in LGBTQI+ health research in India, have important implications for future research and research funding, health policies and programs, and healthcare services and practices for LGBTQI+ populations. There is a clear and compelling need to expand the evidence base on LGBTQI+ health in India to the many health and mental health conditions beyond HIV, and to the health challenges experienced across the diversity of LGBTQI+ people.

Specific population gaps identified in health research among LGBTQI+ people in India indicate the need for greater attention to lesbian and bisexual women, including potential health and mental health disparities compared to cisgender heterosexual women. Additional focus on lesbian and bisexual women’s experiences in access to and use of health services is sorely needed across an array of health conditions and healthcare settings, particularly given that studies reported their underutilization of routine preventive healthcare services. Reviews conducted on the health of sexual minority women in other countries arrived at similar conclusions [ 207 , 208 ]. Further gaps emerged in the dearth of research with transmasculine people [ 209 ], and more broadly in research on access to medical and surgical gender-affirmative care needs for trans people. Greater attention to studies of healthcare providers and healthcare settings, and on healthcare provider training, that aim to improve access to gender-affirmative clinical services are needed [ 210 ]. Finally, there is a wholesale lack of health research among people with intersex variations. Future studies should focus on general health profiles, experiences in access to healthcare, and impact of non-essential or ‘corrective’ surgeries on health and mental health outcomes among people with intersex variations [ 211 , 212 ].

Overall, the relatively small number of intervention studies were largely conducted with MSM in relation to HIV prevention. Nevertheless, while NACO supports several targeted interventions among MSM and TGW, with estimated programmatic coverage of nearly 88% to 95% of at-risk MSM and TGW [ 213 ], the lack of peer-reviewed publications on the effectiveness of such interventions limits their contribution to evidence-informed HIV prevention programs and policies in India. Although these interventions are primarily for programmatic purposes, the absence of published data represents a missed opportunity.

The stark lack of formal health outreach structures in India for lesbian and bisexual women, and for transmasculine people, makes it challenging to reach these populations through established organizational partners. Accordingly, greater involvement of a diversity of LGBTQI+ community-led groups in collaborative and participatory research studies is needed to expand opportunities to engage their inputs on research priorities, recruitment, and data collection methods, thereby also building their capacity in guiding and implementing research [ 214 ]. Such participatory mechanisms may be key to meaningful involvement of diverse and under-represented groups among LGBTQI+ communities and expanding relevant research evidence to advance their health. Strategic research funding mechanisms that target such underrepresented groups, as well as requiring community partnerships in certain health research streams, may be mechanisms to support such initiatives moving forward. For example, the U.S. NIH has established a sexual and gender minority research office, increased dedicated research funds, and released a five-year strategic plan to advance health research among sexual and gender minorities [ 215 ]. Similar steps need to be taken by the Indian Council of Medical Research, Department of Health Research. With just over one-fourth of the studies in this review funded fully or in part (in collaboration with NIH) by Indian government agencies, such as ICMR and NACO, there is a clear need to increase funding for LGBTQI+ health research by the Government of India.

This synthesis also highlights the connections between stigma, discrimination and violence, and the health issues faced by LGBTQI+ people. Several studies advance evidence on how discrimination and violence victimization contribute to psychosocial health problems and HIV risk among MSM and TGW [ 101 , 216 ]. Stigma and violence elimination programs, and interventions in multiple sectors (for example, healthcare, education, employment) and social campaigns to promote understanding and acceptance of LGBTQI+ people are needed. The lack of access to gender-affirmative hormone therapy and surgeries for trans people highlights the need to improve access to such services, especially in the context of the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019, of India. This act clearly places the responsibility on the Indian central government and state governments to provide medical gender-affirmative health services and health insurance for trans people [ 22 ].

Other research areas that require increased exploration include the role of family and peer support in LGBTQI+ mental health, interventions to increase support from families and communities, and programs to eliminate discrimination and promote acceptance in healthcare, educational and workplace settings [ 25 ]. Given the deleterious impacts of stigma and discrimination on mental health and access to care, and the protective effects of social support and resilience resources, studies that integrate an understanding of social-structural contexts that affect mental health are key to effective approaches to advancing LGBTQI+ health [ 26 ]. Expanding the evidence base on LGBTQI+ health will require additional investments by national and state health research funders, including targeted funding for non-HIV-specific LGBTQI+ health research in the academic sector and in government-funded and government-run health programs on HIV (National AIDS Control Program of NACO), sexual and reproductive health and mental health (under National Health Mission), and non-communicable diseases (for example, National Program for Prevention and Control of Cancers, Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases and Stroke).

Finally, few studies made explicit reference to theoretical frameworks (for example, syndemic theory [ 216 ], minority stress theory [ 96 ], and structural violence [ 217 ]), that guided study design, analysis or interpretation. For one, such theories can advance research and understanding of the needs of understudied populations, such as sexual minority women, with studies also benefitting from community-based participatory methodologies and partnerships [ 198 , 199 ]. The latter can advance application of theoretical frameworks that are sensitized to community-identified concerns, self-identifications, and priorities in Indian cultural contexts [ 199 ]. Several theoretical frameworks such as gender minority stress [ 218 ], gender affirmation [ 219 ] and intersectionality [ 220 ] that have been used productively in research among trans people in western countries, especially the U.S., appear not to be explicitly used in studies from India. Future research should include a focus on adapting existing frameworks to meaningfully address the Indian cultural context, as well as developing new indigenous frameworks for research with LGBTQI+ people in India. Future investigations should also ensure the inclusion of diverse subgroups of trans people—not solely gender binary, but also gender non-binary people—and portray local gender identity terms they use as well as indigenous constructions of gender identity, rather than defaulting to western terminologies, some of which do not translate well culturally or linguistically to the Indian LGBTQI+ experience [ 221 ].

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review should be understood in the context of study limitations. First, we limited searches to English-language texts and those included in major academic databases; however, we are not aware of Indian native language-based academic journals, given that academics and researchers largely publish in English. Second, we did not conduct quality assessments of individual studies as this is outside the purview of a scoping review; we aimed to map the field of available research, and research gaps, rather than answer a specific research question [ 28 ]. Third, we limited our review to peer-reviewed articles, for which we identified a substantial number of sources. Future scoping or systematic reviews should include grey literature from across India to broaden understanding of the landscape of research and gaps in regard to LGBTQI+ health; this is particularly the case given the concentration of studies identified among a minority of Indian states, and conducted almost exclusively in urban areas. Further, we did not include asexual-identified people in this review; future reviews should include this subpopulation to understand their health needs and healthcare experiences [ 222 ].

This scoping review identified key research gaps on LGBTQI+ health in India, with investigations largely limited to HIV-related issues, MSM and TGW populations, and urban study sites. This underscores the need for expanding health research in India to address the broad spectrum of LGBTQI+ people’s lives, specifically in moving beyond HIV-focused research to address mental health and non-communicable diseases as well. Future research should address the extensive gender gap in LGBTQI+ health research in India by focusing on health needs and healthcare experiences of lesbian and bisexual women. The broader spectrum of transgender and gender nonbinary people also merits increased focus, including studies on health needs and gaps with transmasculine people.

Finally, it is crucial to include sexual orientation and gender identity in national health surveys and to provide disaggregated data among LGBTQI+ subpopulations so that extant inequalities between heterosexual and cisgender people, and within LGBTQI+ people, can be documented [ 223 ]. Large-scale government-supported national health surveys among LGBTQI+ people provide a unique opportunity to document and explain health inequalities, and to identify potential solutions [ 224 ]. Strategies to enhance health research among LGBTQI+ people in India include developing a national LGBTQI+ health research agenda, providing dedicated LGBTQI+ health research funding from various government bodies, and investing in the training of researchers and new investigators to competently conduct LGBTQI+ health research. Additionally, investments in improving and sustaining the research and service provision capacities of community-based organizations are crucial as they already assume responsibility for serving a substantial number of LGBTQI+ people who are otherwise underserved by government-funded healthcare systems.

Supporting information

S1 checklist. preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews (prisma-scr) checklist..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001362.s001

S1 Appendix. Sample search string for ProQuest database.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001362.s002

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Luke Reid, JD, PhD (cand.), Research Fellow, University of Toronto Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, for assistance in implementing the literature search.

- 1. UN Committee on Economic SaCRC. General Comment No. 14: The right to the highest attainable standard of health (Art. 12 of the Covenant). 2000.

- 2. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. UN General Assembly; 1966.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 19. Belmonte LA. The international LGBT rights movement: A history. London: Bloomsbury Academic; 2021.

- 20. Badgett MVL, Crehan PR. Investing in a research revolution for LGBTI inclusion. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group; 2016.

- 22. The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019. No. 40. In: Justice MoLa, editor. New Delhi 2019.

- 23. MoSJE. Report of the expert committee on the issues relating to transgender persons. New Delhi: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India, 2014.

- 25. Chakrapani V, Newman PA, Shunmugam M. Stigma toward and mental health of hijras/trans women and self-identified men who have sex with men in India. In: Nakamura N, Logie CH, editors. LGBTQ mental health: International perspectives and experiences. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2020. p. 103–19.

- 87. Ferguson H. Virtual Risk: How MSM and TW in India use media for partner selection [Public Health Theses. 1084]. New Haven: Yale University; 2016.

- 117. Pandya A. Voices of invisibles: Coping responses of men who have sex with men. In: Blaznia C, Shen-Miller DS, editors. An international psychology of men: Theoretical advances, case studies, and clinical innovations. NY: Routledge. 2010. p. 233–58.

- 213. NACO. Sankalak: Status of National AIDS Response. New Delhi: National AIDS Control Organization. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India.; 2021.

- 214. Northridge ME, McGrath BP, Krueger SQ. Using community-based participatory research to understand and eliminate social disparities in health for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations. In: Meyer IH, Northridge ME, editors. The Health of Sexual Minorities: Public Health Perspectives on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Populations. Boston, MA: Springer US; 2007. p. 455–70.

- 215. NIH. NIH Strategic Plan to Advance Research on the Health and Well-being of Sexual and Gender Minorities FYs 2021–2025 2020. Available from: https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/SGMStrategicPlan_2021_2025.pdf .

The Legal Struggles of the LGBTQIA+ Community in India

A recent judgement by the Supreme Court of India put off the question of allowing same-sex marriage, but it still may be seen as a victory for the community.

A large number of present-day Indian laws owe their origins to British rule. Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which made punishable by law any sexual act that was “against the order of nature,” was one such controversial law. Its code included everything from oral and anal sex to intercourse between people of the same sex. In 2013, the High Court of Delhi initially read down the section (“reading down” is legalese for determining the law is no longer valid), but it was later reinstituted by a bench of the Supreme Court of India. In 2019, however, Section 377 was finally struck down by a larger constitutional bench of the Supreme Court.

Over the last decade, India’s vibrant and thriving LGBTQIA+ community has moved the courts to fight for recognition of its legal status and all the rights that should accrue to them as they do to other citizens, including the right to live together, marry, adopt, and have children through surrogacy. Recently, LGBTQIA+ petitioners filed a new case for the recognition of the right to marry members of their own community. In this case, however, the Supreme Court provided no relief, recommending instead that the question should be referred to Parliament to decide . However disappointed the community may have been by this ruling, many were appreciative of the fact that their pleas were heard and debated in the highest court of law, especially since the original legal battle was a long and arduous one.

In a 2019 article published in the National Law School of India Review , Kalpana Kannabiran examines the legal journey of this community at length. She particularly focuses on the “far-reaching influence of peoples’ movements on courtroom cultures in India,” which she arrives at by examining the use of “song, performance, poetry and the outpouring of emotion.”

Kannabiran “trace[s] an intellectual history of rights on the Indian sub-continent that undergird and anticipate the constitution, and cut a path through the dense, thorny thickets of ‘tradition’ towards the rainbows on the horizon.” Her legal entry point is the Supreme Court of India’s aforementioned reading down of Section 377 in Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India . She asserts that

important as this judgment is, it needs to be situated within the larger discourse of civil and political rights imperiled in the present moment of right wing Hindu majoritarianism and its dismantling of constitutional regimes at different levels in India today.

Kannabiran draws attention to various sources to which individual judges of the bench referred while delivering the judgment. These included philosophical entreaties by Goethe and Shakespeare’s timeless lyricality as well as pop culture references with lyrics by Leonard Cohen. Works by Oscar Wilde and his alleged lover Alfred Douglas also made an appearance, as did more contemporary writings by Indian author Vikram Seth and Indian playwright Danish Sheikh.

Lauding the judgment for its “reflection on the power and place of the literary in our constitutional imaginary [which] takes us to a long history of resistance against authoritarianism, arbitrary rule and the orders of caste and brahmanical patriarchy,” she hopes that the court continues to “interrogate punitive and regressive legal regimes” so it may “keep sight of its own moral moorings.”

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

During her examination, she quotes the 2013 judgment delivered by the Supreme Court in Suresh Kumar Koushal vs. Naz Foundation , which had overturned the High Court’s original ruling. Here, the judge observed, “carnal intercourse was criminalized because such acts have the tendency to lead to unmanliness and lead to persons not being useful in society.” The bench also made the erroneous observation that only a few hundred people from this community had suffered from the application of this section. In the process, it discounted the humiliation and emotional suffering of this section of society for a long period of time.

The tide changed with Johar . Quite significantly, Kannabiran notes, it was “the acknowledgment of sexual intimacy and desire—and indeed unfulfilled longing (‘the love that dare not speak its name’) within court-speak,” which was “virtually unheard of prior to Johar ,” that became a beacon of hope to future sections of society battling disempowerment of various kinds. She further asserts that

perhaps one of the most significant interventions made in Johar is the affirming of the rights of minorities. […] The interlocking between caste orders, majoritarianism and heteronormative regimes produces specific proscriptions of speech and curtailment of liberties not confined to minorities but extending to those who speak with them.

Kannabiran ends on a poignant note, calling attention to the “perils and pitfalls that majoritarian rule poses to the futures of the Constitution” by quoting Dr. B. R Ambedkar, the father of the Indian Constitution:

“If things go wrong under the new Constitution, the reason will not be that we had a bad Constitution. What we will have to say is that Man was vile.”

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

- Humans for Voyage Iron: The Remaking of West Africa

- Luanda, Angola: The Paradox of Plenty

- Political Corruption in Athens and Rome

- Capturing the Civil War

Recent Posts

- A “Genre-Bending” Poetic Journey through Modern Korean History

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

India’s LGBTQIA+ community notches legal wins but still faces societal hurdles to acceptance, equal rights

Facebook Twitter Print Email

While there has been some recent progress for India’s LGBTQIA+ community, there is still a long way to go to overcome social stigma and prejudice, and to ensure that all people in the country feel their rights are protected, regardless of gender identity or sexual orientation.

UNAIDS , the main advocate for coordinated global action on the HIV/AIDS pandemic, and the UN Development Progarmme ( UNDP ) offices in India have been important partners in this effort.

On this International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia (IDAHOBIT), celebrated annually on 17 May, we reflect on the journey of some members of this community in India and shed light on the challenges they are still faced with.

‘All hell broke loose’

Noyonika* and Ishita*, residents of a small town in the northeastern Indian state of Assam, are a lesbian couple working with an organization advocating for LGBTQIA+ rights.

But despite her advocacy role in the community, Noyonika has been unable to muster the courage to tell her own family that she is gay. “Very few people know this,” she says. “My family is very conservative, and it would be unthinkable for [them] to understand that I am gay.”

Noyonika’s partner, Ishita, is Agender (not identifying with any gender, or having a lack of gender). She says that she realized in childhood that she was different from other girls and was attracted to girls rather than boys. But her family is also very conservative, and she has not told her father about her reality.

Twenty-three-year-old Minal* and 27-year-old Sangeeta* have a similar story. The couple are residents of a small village in the northwestern state of Punjab. They now live in a big city and work for a well-regarded company.

Sangeeta said that although her own parents eventually came to terms with the relationship, Minal’s family was extremely opposed to the point of harassing the couple. “All hell broke loose,” said Minal.

“In 2019, we got permission to live together through a court order,” Sangeeta explained, but after this Minal’s family started threatening her over the phone.

“They used to say that they would kill me and put my family in jail. Even my family members were scared of these threats. After that [Minal’s family] kept stalking and harassing us for two to three years,” she said.

Today, Sangeeta and Minal are still struggling to have their relationship legally recognized.

*Names have been changed to protect identities.

Struggles for acceptance

Heart-rending stories like these can be found across India, where societal prejudices and harassment continue to plague lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex communities.

Sadhna Mishra, a transgender activist from Odisha, runs a community organization called Sakha. As a child, she faced oppression because she was seen as not conforming to societal gender norms. In 2015, she underwent gender confirming surgery and her journey towards her authentic self began.

Recalling the painful days of her childhood, she said, “Because of my femininity, I became a victim of rape again and again. Whenever I used to cry, my mother would ask why, and I would not be able to say anything. I used to ask why people called me Chhakka and Kinnar [transgender or intersex]. My mother would smile and say that’s because you are different and unique.”

It is because of her mother’s faith in her that Sadhna is now active in fighting for the rights of other transgender persons.

Still, she remembers well the hurdles she has faced, like the early days of trying to get launch her organization and the difficulties she had even finding a place for Sakha’s office. People were reluctant to rent space to a transgender person, so Sadhna was forced to work in public places and parks.

Social prejudices

A lack of understanding and intolerance towards the LGBTQIA+ community are similar, whether in larger cities or in rural areas.

Noyonika says that her organization sees many instances where a man is married to a woman because of societal pressure, without understanding his gender identity. “In villages and towns, you will find many married couples who have children and are forced to live a fake life.”

As for the rural areas of Assam where her organization works, Ishita gave the example of a cultural festival Bhavna being celebrated in Naamghars , or places of worship, where dramas based on mythological stories are presented.

The female characters in these dramas are played mostly by men with feminine characteristics. During festivals they are widely praised, and their feminine characteristics are applauded, but out of the spotlight, they can become victims of harassment.

“They are intimidated, they are sexually exploited, they are molested,” Ishita explained.

A slow path to progress

In recent years, there have been positive legal and policy decisions acknowledging the LGBTQIA+ community in India. This includes the 2014 NALSA (National Legal Service Authority) decision, in which the court upheld everyone's right to identify their own gender and legally recognized hijras and kinnar (transgender persons) as a ‘third gender’.

In 2018, the application of portions of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code to criminalize private consensual sex between men was ruled unconstitutional by India’s Supreme Court. Further, in 2021, a landmark judgment by the Madras High Court directed the state to provide comprehensive welfare services to the LGBTQIA+ communities.

United Nations advocacy

Communication is an important way to foster dialogue and help create a more tolerant and inclusive society, and gradually, perhaps even change mindsets.

To this end, UN Women , in collaboration with India’s Ministry of Women and Child Development, has recently contributed to the development of a gender-inclusive communication guide.

Meanwhile, the UNAIDS and UNDP offices in India are working to assist the LGBTQIA+ community by running awareness and empowerment campaigns, as well as provide those communities with better health and social protection services.

“UNAIDS supports LGBTQ+ people’s leadership in the HIV response and in advocacy for human rights, and is working to tackle discrimination, and to help build inclusive societies where everyone is protected and respected,” said David Bridger, UNAIDS Country Director for India.

He added: “The HIV response has clearly taught all of us that in order to protect everyone’s health, we have to protect everyone’s rights.”

In line with the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Organization’s broad commitment to ‘leave no one behind’, UNDP, is working with governments and partners to strengthen laws, policies and programmes that address inequalities and seek to ensure respect for the human rights of LGBTQIA+ people.

Through the “Being LGBTI in the Asia and the Pacific” programme, UNDP has also implemented relevant regional initiatives.

Opportunities and challenges

UNDP India’s National Programme Manager (Health Systems Strengthening Unit), Dr. Chiranjeev Bhattacharjya said, “At UNDP India, we have been working very closely with the LGBTQI community to advance their rights.”

Indeed, he continued, there are currently multiple opportunities to support the community due to progressive legal landmarks like the NALSA judgement, decriminalization of same sex relationships (377 IPC) and the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act of 2019 which has raised awareness regarding their development.

“However, there are implementation challenges which will need multi-stakeholder collaboration and we will continue to work with the community to address them so that we leave no one behind,” he stated.

Even as the Indian legal landscape has inched towards broader inclusion with the repeal of Section 377, the country’s LGBTQIA+ communities are still awaiting recognition – and justice – when dealing with many areas of their everyday lives and interactions, for example: who can be designated 'next of kin' if one partner is hospitalized; can a partner be added to a life insurance policy; or whether legal recognition could be given to gay marriage.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 04 January 2024

Unveiling narratives: representation of same-sex love in bollywood films

- Prasitha V ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6192-2699 1 &

- Bhuvaneswari G 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 57 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

23k Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cultural and media studies

The cultural history of India has been ignorant of various sexual orientations and gender identities leaving LGBTQIA+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual) community with a life of guilt and shame. Visual Media plays a key role in shaping society’s opinion of LGBTQIA+ people and individuals who come to terms with their gender and sexuality at a particular phase of their lives. The representation of homosexual characters is constantly diversified in Bollywood, and the change is evident from being caricatured and even scorned to being shown as prominent protagonists. The growing visibility and the positive portrayal of homosexual characters in Bollywood help to create a more inclusive society. This paper focuses on the select Bollywood films, Ek Ladki Ko Dekha Toh Aisa Laga (2019) by Shelly Chopra Dhar and Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan (2020) by Hitesh Kewalya. The paper analyses the visual elements in select films and their role in shaping the portrayal of homosexuality within the narrative. The paper also reads the chosen films through the lens of familial resistance to same-sex relationships. By analysing the select films, the paper concludes that, though prior Bollywood films have explored the theme of individuals disclosing their sexual identity to their families, the primary narrative focus is not on seeking acceptance from their family members. Thus, the unique emphasis on seeking acceptance and understanding between family members and homosexual individuals set the select films as exceptional narratives within the context of Bollywood’s portrayal of homosexuality.

Similar content being viewed by others

‘We resolve our own sorrows’: screening comfort women in Chinese documentary films

Gender roles in Spanish cinema: a critical and creative process around the word ‘woman’

The segregated gun as an indicator of racism and representations in film, introduction.

Homosexuality has become a contentious issue that garnered considerable attention, but the field of medicine and psychiatry do not classify homosexuality as a disorder. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) officially announced that homosexuality is not a mental illness in 1973 by removing it from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychological Disorders (Spitzer, 1981 ). Freud (1935) states that homosexuality is a variation in sexual function resulting from a specific interruption in sexual development (Marshall, 2014 ). This variation in sexual function is not limited to humans but is also evident in animals as well. Throughout the human and non-human animal kingdoms, sexual behaviour exhibits a wide range of diversity and is controlled by complex mechanisms. Havelock Elis, a British physician proposed that “homosexuality was a common biological manifestation in human beings and animals alike” (Beccalossi, 2012 , p. 172). Research shows that same-sex behaviour is not unknown among animals (Owen, 2004 ; Bawagan, 2019 ; Rao, 2017 ) Considering the extensive research and definitions, multiple countries around the world including India decriminalised homosexuality.

A perception that still exists is that homosexuality is a crime imported from the West, though it has a longstanding existence in Indian history. The book Same-Sex Love in India ( 2008 ), in which Ruth Vanita and Saleem Kidwai enumerated the existence of same-sex sexuality in Rig Veda , which dates back to 1500 B.C. The Kama sutra (aphorism on love), composed by Vatsyayana between the 1st and 6th century A.D., alludes to same-sex sexual behaviour (Vanita and Kidwai, 2008 ). In the same vein, depictions in the pillar caves of Karle (50–75 CE), reveal that two women embrace each other with bare breasts in Buddhist tradition (Bhugra et al., 2010 ). Thus, ancient texts suggest that homosexuality has a historical presence in India. “With the start of British colonisation, the destruction of the images of homosexual expression and sexual expression in general became more systematic. The influence of imperialist British on Indian sexuality took the form of repression and domination” (Tiwari, 2010 , p.15) Ironically, it was homophobia that was introduced into India from the West and not homosexuality. This can be understood through the fact that it was during the British era, that Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code was implemented to outlaw homosexual activity, which states that:

Unnatural offences – Whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal shall be punished with imprisonment for life, or with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to 10 years, and shall be liable to fine. Explanation – Penetration is sufficient to constitute the carnal intercourse necessary to the offence described in this section.

Thus, heterosexism as an ideological framework started denigrating non-heterosexual conduct, and homosexuals are subjected to discrimination, verbal abuse, and physical attacks in a culturally conservative and ideologically dense society like India. The practices that deviate from the dominant ideology of society in India are considered a crime, and those who engage in it are excluded from society. As Meyer states, this lead individuals who identify as homosexuals to internalise cultural anti-homosexual views, leading to internalised homophobia, long before they become aware of their sexuality (Meyer, 2009 ). The concept of heterosexism became deeply rooted in the socio-cultural norms and values of the Indian society which was sex-positive in the past. “Historically, cultural and social values and the attitudes towards sexuality in India have been sex positive, but over the past 200 years under the British colonial rule they became very negative and indeed punitive towards homosexuality and homosexual men and women in line with prevalent Victorian attitudes to sex and sexual activity.” (Bhugra et al., 2015 , p. 455) Nevertheless, it is synonymous to iterate that sexual prejudice and victimisation of homosexuals prevailed in India only after colonisation. The struggle against Section 377 in India began in the early 1990s, when the AIDS Bhedbhav Virodhi Andolan (ABVA) produced a study detailing the persecution faced by the gay community of India, particularly by law enforcement (Thomas, 2018 ). India decriminalised same-sex relationships in the year 2018 after multiple conflicts and decisions. Though legal decisions are in favour of homosexuality, society hasn’t been able to completely embrace homosexuals.

The pre-1990s Hindi industry is referred to as Bombay cinema. The term Bollywood is the blend of Bombay cinema and Hollywood. India’s ambition for globalising its economy coincided with the digital revolution in the early twenty-first century. Also, Bollywood as a global phenomenon not only signifies a break beyond the national cinematic model but hints at a shift in the writing of film history (Chakravarty, 2012 ). This prompted the integration of the entertainment industry, giving rise to the new sector known as entertainment media or Bollywood. Thus, Bollywood stands as a new cultural face of India as a result of economic liberalisation and technological advancements. Ashish Rajadhyaksha ( 2003 ) in his work, “The ‘Bollywoodization’ of the Indian Cinema: cultural nationalism in a global arena”, distinguished the Hindi cinema produced in Bombay from Bollywood by placing it within a broader social, political, and economic context. “Ashish takes recourse to the political economy/cultural studies divide by defining Bollywood as culture industry and Indian cinema as serving the cultural/ideological function of creating the national subject” (Chakravarty, 2012 , p. 274). The term “Cultural Industry” shows how Bollywood is not about merely making films but also about the production of cultural commodities that influence public culture and values. The term Bollywood is preferred over Bombay cinema in this study as films after the 1990s have been referred in this paper. This paper focuses on Hindi films (Bollywood) that explore themes related to homosexuality and the representation of homosexuals.

Being a marginalised category, homosexuals require an appropriate representation to address their problems and concerns (Lama, 2020 ). “As there is no single, easily identifiable characteristic of homosexuality, people of any sexual orientation often turn to visual media to obtain a picture of homosexuality and of gay and lesbian culture” (Levina et al., 2006 , p. 739; Gray, 2009 ). The primary source of social knowledge about LGBTQ identities is the media (Gray, 2009 ). “[H]ow we are seen determines in part how we are treated; how we treat others is based on how we see them; such seeing comes from representation” (Dyer, 2002 , p. 1). Thus, the perception of an individual towards a particular group is influenced by the visual representation, and in turn, the representation affects the individual’s behaviour towards that group. If visibility is the path to acceptance for homosexual individuals, much of that awareness travels through media representations including films, advertisements, and other forms of media. Films have become an effective form of media that relays significant societal issues and they also subtly influence society’s way of thinking. Consequently, Bollywood has created a dichotomy of representation depicting homosexual characters as either humiliating, comical characters as the character Yogendra in the film Student of the Year ( 2012 ) or as individuals who maintain lives filled with internal conflict by hiding their sexuality as the character Rahul in the film Kapoor & Sons ( 2016 ). The directors and scriptwriters have largely been constrained to adopt or experiment with homosexual protagonists in films. This hesitance can be attributed to the political challenges and strong opposition faced by the Bollywood industry, especially during the release of films like Fire ( 1996 ) and Girlfriend ( 2004 ). “Probably the only two Hindi films with lead characters as lesbians ( Fire and Girlfriend ) have invited huge protests and physical attacks on theatres by right-wing activists” (Srinivasan, 2011 , p. 77). Slowly, there has been an increase in the number of films dealing with the struggle of homosexuals and their attempts to assert their individuality and sexual identity. Several films in Bollywood deal with themes of familial rejection based on the characters’ sexual identity. However, the select films Ek Ladki Ko Dekha Toh Aisa Laga ( 2019 ) by Shelly Chopra Dhar and Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan ( 2020 ) by Hitesh Kewalya introduce a narrative of negotiation and reconciliation between family members and the homosexual individuals. The films also feature protagonists who fight for the acceptance of their sexual identity. The research uses a qualitative approach to analyse the visual elements in the narratives and to examine the familial resistance to homosexuals in select films. The research aims to answer the following questions. How do visual elements in the narrative contribute to the representation of homosexuality in the select films? How familial resistance is portrayed in the chosen films, from the perspectives of both homosexual individuals and their families?

Literature review

The Indian film industry often casts women in roles that symbolise “Mother India” and conform to traditional heteronormative roles within the domestic and reproductive realm. This practice confined them to represent and uphold cultural identities. The cultural identity associated with womanhood serves as a strategic element within the framework of the heteropatriarchal structure. The film Fire ( 1996 ) undertakes the challenge of deconstructing the narratives related to women, sexuality, and cultural nationalism and also hints at a tie between tradition, reproduction, and marriage (Lohani-Chase, 2012 ). In Indian society, where patriarchy strongly influences binary gender and gender roles, it also plays a significant role in shaping attitudes toward homosexuality. The representation of gay men is notably normalised in Bollywood films such as Dostana and Straight . Nonetheless, when lesbian characters are depicted in films like Fire and Girlfriend , it brings out complex interplay between gender and culture within society, leading to protests against such portrayals. This patriarchal approach highlights the intricate and gender-biased dynamics that shape the identities of queer women and constrains female participation. The depiction of female desire and the existence of an agency that recognises it are explicit in lesbian films, and as such, they are strongly opposed (Srinivasan, 2011 ). Bollywood provides a varied representation of homosexual characters. Initially, these characters were often portrayed as comical figures, depicted in illogical and odd situations, seemingly included to amuse and entertain the audience. An illustrative example is the character Pinkoo, depicted as an effeminate homosexual in the film Mast Kalandar (1991). Some films present sensitive gay characters as exemplified in the films Ajeeb Dastaan Hai Yeh ( 2013 ), My Brother Nikhil ( 2005 ), and I Am (2010). This comical and sensitive portrayal highlights the negative connotations associated with homosexual characters within the realm of Bollywood and normalises homophobia (Bhughra et al., 2015 ). Furthermore, a common stereotype associated with gay characters is the representation of an effeminate horny gay man as shown in the films Dostana ( 2008 ) and Kal Ho Na Ho (2003). These characters accept jokes at the cost of their sexuality and wear flamboyant clothes just to provide the audience with a dry chuckle between the scenes (Bose, 2018 ). In addition to the infrequency of lesbian representation, there is also a stark disparity in the character development and portrayal of lesbian characters in Bollywood films. Until recent years, many lesbian characters lacked realistic or progressive depictions, often falling victim to stereotypes or being subjected to the incessant male gaze as shown in films like Girlfriend and Unfreedom (Bose and Sreena, 2021 ). In recent narratives, films have started featuring lesbians as central protagonists. However, they are often portrayed as individuals who are connected to culture and gender norms. The portrayal of lesbians as valuing their families and being aware of their class privilege aims to foster greater acceptance of their sexuality among the audience and also address concerns related to acculturation anxieties.

Ek Ladki Ko Dekho Toh Aisa Laga ( 2019 ) brings queerness into the fold of the heteronormative natal family and represents Sweety (lesbian) as the quintessential good Indian queer woman whose deference to the family sanitises and disciplines her queerness. (Chatterjee, 2021 ).

The films that represent homosexuality in the current era such as Ek Ladki Ko Dekha Toh Aisa Laga ( 2019 ), Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan ( 2020 ), and Badhaai Do ( 2022 ) employ representational and discursive methods that reveal a necessity to demonstrate the compatibility of queerness with culture, queerness with the nation, and queerness with the family. This is done to facilitate queer representation within mainstream contexts and to introduce queer elements into the mainstream without unsettling it with the prospect of incompatibility. These films endeavour to normalise same-sex love in a manner that does not pose a threat to the prevailing heterosexual status quo (Arora and Sylvia, 2023 ). While research has been conducted on the negative portrayals and misrepresentation of same-sex love in Bollywood, there is a notable gap in the literature when it comes to comprehensive research that traces the diverse representations of homosexuality in Bollywood and provides a clear and in-depth analysis of the exceptional narratives among them. This paper aims to analyse the selected Bollywood films as exceptional narratives from the prior films that depict homosexual characters. The paper also analyses family as a resistance to same-sex love.