Cookies on this website

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you click 'Accept all cookies' we'll assume that you are happy to receive all cookies and you won't see this message again. If you click 'Reject all non-essential cookies' only necessary cookies providing core functionality such as security, network management, and accessibility will be enabled. Click 'Find out more' for information on how to change your cookie settings.

Tips for a qualitative dissertation

Veronika Williams

17 October 2017

Tips for students

This blog is part of a series for Evidence-Based Health Care MSc students undertaking their dissertations.

Undertaking an MSc dissertation in Evidence-Based Health Care (EBHC) may be your first hands-on experience of doing qualitative research. I chatted to Dr. Veronika Williams, an experienced qualitative researcher, and tutor on the EBHC programme, to find out her top tips for producing a high-quality qualitative EBHC thesis.

1) Make the switch from a quantitative to a qualitative mindset

It’s not just about replacing numbers with words. Doing qualitative research requires you to adopt a different way of seeing and interpreting the world around you. Veronika asks her students to reflect on positivist and interpretivist approaches: If you come from a scientific or medical background, positivism is often the unacknowledged status quo. Be open to considering there are alternative ways to generate and understand knowledge.

2) Reflect on your role

Quantitative research strives to produce “clean” data unbiased by the context in which it was generated. With qualitative methods, this is neither possible nor desirable. Students should reflect on how their background and personal views shape the way they collect and analyse their data. This will not only add to the transparency of your work but will also help you interpret your findings.

3) Don’t forget the theory

Qualitative researchers use theories as a lens through which they understand the world around them. Veronika suggests that students consider the theoretical underpinning to their own research at the earliest stages. You can read an article about why theories are useful in qualitative research here.

4) Think about depth rather than breadth

Qualitative research is all about developing a deep and insightful understanding of the phenomenon/ concept you are studying. Be realistic about what you can achieve given the time constraints of an MSc. Veronika suggests that collecting and analysing a smaller dataset well is preferable to producing a superficial, rushed analysis of a larger dataset.

5) Blur the boundaries between data collection, analysis and writing up

Veronika strongly recommends keeping a research diary or using memos to jot down your ideas as your research progresses. Not only do these add to your audit trail, these entries will help contribute to your first draft and the process of moving towards theoretical thinking. Qualitative researchers move back and forward between their dataset and manuscript as their ideas develop. This enriches their understanding and allows emerging theories to be explored.

6) Move beyond the descriptive

When analysing interviews, for example, it can be tempting to think that having coded your transcripts you are nearly there. This is not the case! You need to move beyond the descriptive codes to conceptual themes and theoretical thinking in order to produce a high-quality thesis. Veronika warns against falling into the pitfall of thinking writing up is, “Two interviews said this whilst three interviewees said that”.

7) It’s not just about the average experience

When analysing your data, consider the outliers or negative cases, for example, those that found the intervention unacceptable. Although in the minority, these respondents will often provide more meaningful insight into the phenomenon or concept you are trying to study.

8) Bounce ideas

Veronika recommends sharing your emerging ideas and findings with someone else, maybe with a different background or perspective. This isn’t about getting to the “right answer” rather it offers you the chance to refine your thinking. Be sure, though, to fully acknowledge their contribution in your thesis.

9) Be selective

In can be a challenge to meet the dissertation word limit. It won’t be possible to present all the themes generated by your dataset so focus! Use quotes from across your dataset that best encapsulate the themes you are presenting. Display additional data in the appendix. For example, Veronika suggests illustrating how you moved from your coding framework to your themes.

10) Don’t panic!

There will be a stage during analysis and write up when it seems undoable. Unlike quantitative researchers who begin analysis with a clear plan, qualitative research is more of a journey. Everything will fall into place by the end. Be sure, though, to allow yourself enough time to make sense of the rich data qualitative research generates.

Related course:

Qualitative research methods.

Short Course

Dissertations and research projects

- Book a session

- Planning your research

Developing a theoretical framework

Reflecting on your position, extended literature reviews, presenting qualitative data.

- Quantitative research

- Writing up your research project

- e-learning and books

- SkillsCheck This link opens in a new window

- ⬅ Back to Skills Centre This link opens in a new window

- Review this resource

What is a theoretical framework?

Developing a theoretical framework for your dissertation is one of the key elements of a qualitative research project. Through writing your literature review, you are likely to have identified either a problem that need ‘fixing’ or a gap that your research may begin to fill.

The theoretical framework is your toolbox . In the toolbox are your handy tools: a set of theories, concepts, ideas and hypotheses that you will use to build a solution to the research problem or gap you have identified.

The methodology is the instruction manual: the procedure and steps you have taken, using your chosen tools, to tackle the research problem.

Why do I need a theoretical framework?

Developing a theoretical framework shows that you have thought critically about the different ways to approach your topic, and that you have made a well-reasoned and evidenced decision about which approach will work best. theoretical frameworks are also necessary for solving complex problems or issues from the literature, showing that you have the skills to think creatively and improvise to answer your research questions. they also allow researchers to establish new theories and approaches, that future research may go on to develop., how do i create a theoretical framework for my dissertation.

First, select your tools. You are likely to need a variety of tools in qualitative research – different theories, models or concepts – to help you tackle different parts of your research question.

When deciding what tools would be best for the job of answering your research questions or problem, explore what existing research in your area has used. You may find that there is a ‘standard toolbox’ for qualitative research in your field that you can borrow from or apply to your own research.

You will need to justify why your chosen tools are best for the job of answering your research questions, at what stage they are most relevant, and how they relate to each other. Some theories or models will neatly fit together and appear in the toolboxes of other researchers. However, you may wish to incorporate a model or idea that is not typical for your research area – the ‘odd one out’ in your toolbox. If this is the case, make sure you justify and account for why it is useful to you, and look for ways that it can be used in partnership with the other tools you are using.

You should also be honest about limitations, or where you need to improvise (for example, if the ‘right’ tool or approach doesn’t exist in your area).

This video from the Skills Centre includes an overview and example of how you might create a theoretical framework for your dissertation:

How do I choose the 'right' approach?

When designing your framework and choosing what to include, it can often be difficult to know if you’ve chosen the ‘right’ approach for your research questions. One way to check this is to look for consistency between your objectives, the literature in your framework, and your overall ethos for the research. This means ensuring that the literature you have used not only contributes to answering your research objectives, but that you also use theories and models that are true to your beliefs as a researcher.

Reflecting on your values and your overall ambition for the project can be a helpful step in making these decisions, as it can help you to fully connect your methodology and methods to your research aims.

Should I reflect on my position as a researcher?

If you feel your position as a researcher has influenced your choice of methods or procedure in any way, the methodology is a good place to reflect on this. Positionality acknowledges that no researcher is entirely objective: we are all, to some extent, influenced by prior learning, experiences, knowledge, and personal biases. This is particularly true in qualitative research or practice-based research, where the student is acting as a researcher in their own workplace, where they are otherwise considered a practitioner/professional. It's also important to reflect on your positionality if you belong to the same community as your participants where this is the grounds for their involvement in the research (ie. you are a mature student interviewing other mature learners about their experences in higher education).

The following questions can help you to reflect on your positionality and gauge whether this is an important section to include in your dissertation (for some people, this section isn’t necessary or relevant):

- How might my personal history influence how I approach the topic?

- How am I positioned in relation to this knowledge? Am I being influenced by prior learning or knowledge from outside of this course?

- How does my gender/social class/ ethnicity/ culture influence my positioning in relation to this topic?

- Do I share any attributes with my participants? Are we part of a s hared community? How might this have influenced our relationship and my role in interviews/observations?

- Am I invested in the outcomes on a personal level? Who is this research for and who will feel the benefits?

One option for qualitative projects is to write an extended literature review. This type of project does not require you to collect any new data. Instead, you should focus on synthesising a broad range of literature to offer a new perspective on a research problem or question.

The main difference between an extended literature review and a dissertation where primary data is collected, is in the presentation of the methodology, results and discussion sections. This is because extended literature reviews do not actively involve participants or primary data collection, so there is no need to outline a procedure for data collection (the methodology) or to present and interpret ‘data’ (in the form of interview transcripts, numerical data, observations etc.) You will have much more freedom to decide which sections of the dissertation should be combined, and whether new chapters or sections should be added.

Here is an overview of a common structure for an extended literature review:

Introduction

- Provide background information and context to set the ‘backdrop’ for your project.

- Explain the value and relevance of your research in this context. Outline what do you hope to contribute with your dissertation.

- Clarify a specific area of focus.

- Introduce your research aims (or problem) and objectives.

Literature review

You will need to write a short, overview literature review to introduce the main theories, concepts and key research areas that you will explore in your dissertation. This set of texts – which may be theoretical, research-based, practice-based or policies – form your theoretical framework. In other words, by bringing these texts together in the literature review, you are creating a lens that you can then apply to more focused examples or scenarios in your discussion chapters.

Methodology

As you will not be collecting primary data, your methodology will be quite different from a typical dissertation. You will need to set out the process and procedure you used to find and narrow down your literature. This is also known as a search strategy.

Including your search strategy

A search strategy explains how you have narrowed down your literature to identify key studies and areas of focus. This often takes the form of a search strategy table, included as an appendix at the end of the dissertation. If included, this section takes the place of the traditional 'methodology' section.

If you choose to include a search strategy table, you should also give an overview of your reading process in the main body of the dissertation. Think of this as a chronology of the practical steps you took and your justification for doing so at each stage, such as:

- Your key terms, alternatives and synonyms, and any terms that you chose to exclude.

- Your choice and combination of databases;

- Your inclusion/exclusion criteria, when they were applied and why. This includes filters such as language of publication, date, and country of origin;

- You should also explain which terms you combined to form search phrases and your use of Boolean searching (AND, OR, NOT);

- Your use of citation searching (selecting articles from the bibliography of a chosen journal article to further your search).

- Your use of any search models, such as PICO and SPIDER to help shape your approach.

- Search strategy template A simple template for recording your literature searching. This can be included as an appendix to show your search strategy.

The discussion section of an extended literature review is the most flexible in terms of structure. Think of this section as a series of short case studies or ‘windows’ on your research. In this section you will apply the theoretical framework you formed in the literature review – a combination of theories, models and ideas that explain your approach to the topic – to a series of different examples and scenarios. These are usually presented as separate discussion ‘chapters’ in the dissertation, in an order that you feel best fits your argument.

Think about an order for these discussion sections or chapters that helps to tell the story of your research. One common approach is to structure these sections by common themes or concepts that help to draw your sources together. You might also opt for a chronological structure if your dissertation aims to show change or development over time. Another option is to deliberately show where there is a lack of chronology or narrative across your case studies, by ordering them in a fragmentary order! You will be able to reflect upon the structure of these chapters elsewhere in the dissertation, explaining and defending your decision in the methodology and conclusion.

A summary of your key findings – what you have concluded from your research, and how far you have been able to successfully answer your research questions.

- Recommendations – for improvements to your own study, for future research in the area, and for your field more widely.

- Emphasise your contributions to knowledge and what you have achieved.

Alternative structure

Depending on your research aims, and whether you are working with a case-study type approach (where each section of the dissertation considers a different example or concept through the lens established in your literature review), you might opt for one of the following structures:

Splitting the literature review across different chapters:

This structure allows you to pull apart the traditional literature review, introducing it little by little with each of your themed chapters. This approach works well for dissertations that attempt to show change or difference over time, as the relevant literature for that section or period can be introduced gradually to the reader.

Whichever structure you opt for, remember to explain and justify your approach. A marker will be interested in why you decided on your chosen structure, what it allows you to achieve/brings to the project and what alternatives you considered and rejected in the planning process. Here are some example sentence starters:

In qualitative studies, your results are often presented alongside the discussion, as it is difficult to include this data in a meaningful way without explanation and interpretation. In the dsicussion section, aim to structure your work thematically, moving through the key concepts or ideas that have emerged from your qualitative data. Use extracts from your data collection - interviews, focus groups, observations - to illustrate where these themes are most prominent, and refer back to the sources from your literature review to help draw conclusions.

Here's an example of how your data could be presented in paragraph format in this section:

Example from 'Reporting and discussing your findings ', Monash University .

- << Previous: Planning your research

- Next: Quantitative research >>

- Last Updated: Apr 17, 2024 1:52 PM

- URL: https://libguides.shu.ac.uk/researchprojects

Chapter 11. Interviewing

Introduction.

Interviewing people is at the heart of qualitative research. It is not merely a way to collect data but an intrinsically rewarding activity—an interaction between two people that holds the potential for greater understanding and interpersonal development. Unlike many of our daily interactions with others that are fairly shallow and mundane, sitting down with a person for an hour or two and really listening to what they have to say is a profound and deep enterprise, one that can provide not only “data” for you, the interviewer, but also self-understanding and a feeling of being heard for the interviewee. I always approach interviewing with a deep appreciation for the opportunity it gives me to understand how other people experience the world. That said, there is not one kind of interview but many, and some of these are shallower than others. This chapter will provide you with an overview of interview techniques but with a special focus on the in-depth semistructured interview guide approach, which is the approach most widely used in social science research.

An interview can be variously defined as “a conversation with a purpose” ( Lune and Berg 2018 ) and an attempt to understand the world from the point of view of the person being interviewed: “to unfold the meaning of peoples’ experiences, to uncover their lived world prior to scientific explanations” ( Kvale 2007 ). It is a form of active listening in which the interviewer steers the conversation to subjects and topics of interest to their research but also manages to leave enough space for those interviewed to say surprising things. Achieving that balance is a tricky thing, which is why most practitioners believe interviewing is both an art and a science. In my experience as a teacher, there are some students who are “natural” interviewers (often they are introverts), but anyone can learn to conduct interviews, and everyone, even those of us who have been doing this for years, can improve their interviewing skills. This might be a good time to highlight the fact that the interview is a product between interviewer and interviewee and that this product is only as good as the rapport established between the two participants. Active listening is the key to establishing this necessary rapport.

Patton ( 2002 ) makes the argument that we use interviews because there are certain things that are not observable. In particular, “we cannot observe feelings, thoughts, and intentions. We cannot observe behaviors that took place at some previous point in time. We cannot observe situations that preclude the presence of an observer. We cannot observe how people have organized the world and the meanings they attach to what goes on in the world. We have to ask people questions about those things” ( 341 ).

Types of Interviews

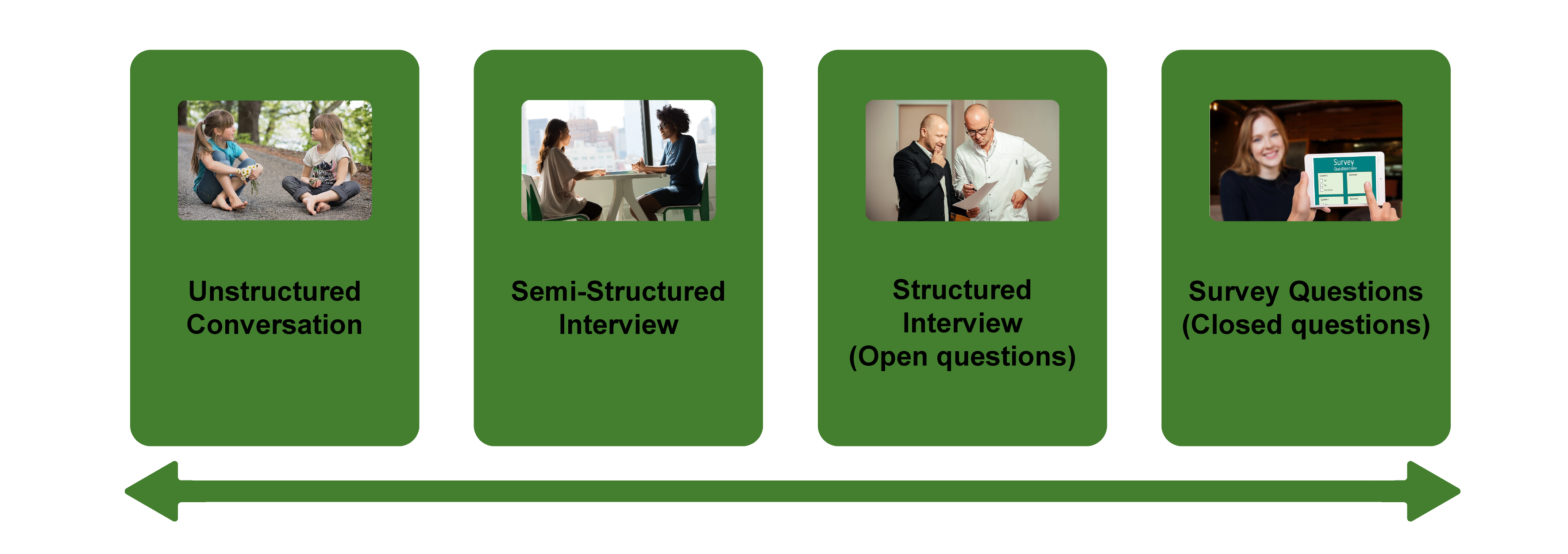

There are several distinct types of interviews. Imagine a continuum (figure 11.1). On one side are unstructured conversations—the kind you have with your friends. No one is in control of those conversations, and what you talk about is often random—whatever pops into your head. There is no secret, underlying purpose to your talking—if anything, the purpose is to talk to and engage with each other, and the words you use and the things you talk about are a little beside the point. An unstructured interview is a little like this informal conversation, except that one of the parties to the conversation (you, the researcher) does have an underlying purpose, and that is to understand the other person. You are not friends speaking for no purpose, but it might feel just as unstructured to the “interviewee” in this scenario. That is one side of the continuum. On the other side are fully structured and standardized survey-type questions asked face-to-face. Here it is very clear who is asking the questions and who is answering them. This doesn’t feel like a conversation at all! A lot of people new to interviewing have this ( erroneously !) in mind when they think about interviews as data collection. Somewhere in the middle of these two extreme cases is the “ semistructured” interview , in which the researcher uses an “interview guide” to gently move the conversation to certain topics and issues. This is the primary form of interviewing for qualitative social scientists and will be what I refer to as interviewing for the rest of this chapter, unless otherwise specified.

Informal (unstructured conversations). This is the most “open-ended” approach to interviewing. It is particularly useful in conjunction with observational methods (see chapters 13 and 14). There are no predetermined questions. Each interview will be different. Imagine you are researching the Oregon Country Fair, an annual event in Veneta, Oregon, that includes live music, artisan craft booths, face painting, and a lot of people walking through forest paths. It’s unlikely that you will be able to get a person to sit down with you and talk intensely about a set of questions for an hour and a half. But you might be able to sidle up to several people and engage with them about their experiences at the fair. You might have a general interest in what attracts people to these events, so you could start a conversation by asking strangers why they are here or why they come back every year. That’s it. Then you have a conversation that may lead you anywhere. Maybe one person tells a long story about how their parents brought them here when they were a kid. A second person talks about how this is better than Burning Man. A third person shares their favorite traveling band. And yet another enthuses about the public library in the woods. During your conversations, you also talk about a lot of other things—the weather, the utilikilts for sale, the fact that a favorite food booth has disappeared. It’s all good. You may not be able to record these conversations. Instead, you might jot down notes on the spot and then, when you have the time, write down as much as you can remember about the conversations in long fieldnotes. Later, you will have to sit down with these fieldnotes and try to make sense of all the information (see chapters 18 and 19).

Interview guide ( semistructured interview ). This is the primary type employed by social science qualitative researchers. The researcher creates an “interview guide” in advance, which she uses in every interview. In theory, every person interviewed is asked the same questions. In practice, every person interviewed is asked mostly the same topics but not always the same questions, as the whole point of a “guide” is that it guides the direction of the conversation but does not command it. The guide is typically between five and ten questions or question areas, sometimes with suggested follow-ups or prompts . For example, one question might be “What was it like growing up in Eastern Oregon?” with prompts such as “Did you live in a rural area? What kind of high school did you attend?” to help the conversation develop. These interviews generally take place in a quiet place (not a busy walkway during a festival) and are recorded. The recordings are transcribed, and those transcriptions then become the “data” that is analyzed (see chapters 18 and 19). The conventional length of one of these types of interviews is between one hour and two hours, optimally ninety minutes. Less than one hour doesn’t allow for much development of questions and thoughts, and two hours (or more) is a lot of time to ask someone to sit still and answer questions. If you have a lot of ground to cover, and the person is willing, I highly recommend two separate interview sessions, with the second session being slightly shorter than the first (e.g., ninety minutes the first day, sixty minutes the second). There are lots of good reasons for this, but the most compelling one is that this allows you to listen to the first day’s recording and catch anything interesting you might have missed in the moment and so develop follow-up questions that can probe further. This also allows the person being interviewed to have some time to think about the issues raised in the interview and go a little deeper with their answers.

Standardized questionnaire with open responses ( structured interview ). This is the type of interview a lot of people have in mind when they hear “interview”: a researcher comes to your door with a clipboard and proceeds to ask you a series of questions. These questions are all the same whoever answers the door; they are “standardized.” Both the wording and the exact order are important, as people’s responses may vary depending on how and when a question is asked. These are qualitative only in that the questions allow for “open-ended responses”: people can say whatever they want rather than select from a predetermined menu of responses. For example, a survey I collaborated on included this open-ended response question: “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?” Some of the answers were simply one word long (e.g., “debt”), and others were long statements with stories and personal anecdotes. It is possible to be surprised by the responses. Although it’s a stretch to call this kind of questioning a conversation, it does allow the person answering the question some degree of freedom in how they answer.

Survey questionnaire with closed responses (not an interview!). Standardized survey questions with specific answer options (e.g., closed responses) are not really interviews at all, and they do not generate qualitative data. For example, if we included five options for the question “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?”—(1) debt, (2) social networks, (3) alienation, (4) family doesn’t understand, (5) type of grad program—we leave no room for surprises at all. Instead, we would most likely look at patterns around these responses, thinking quantitatively rather than qualitatively (e.g., using regression analysis techniques, we might find that working-class sociologists were twice as likely to bring up alienation). It can sometimes be confusing for new students because the very same survey can include both closed-ended and open-ended questions. The key is to think about how these will be analyzed and to what level surprises are possible. If your plan is to turn all responses into a number and make predictions about correlations and relationships, you are no longer conducting qualitative research. This is true even if you are conducting this survey face-to-face with a real live human. Closed-response questions are not conversations of any kind, purposeful or not.

In summary, the semistructured interview guide approach is the predominant form of interviewing for social science qualitative researchers because it allows a high degree of freedom of responses from those interviewed (thus allowing for novel discoveries) while still maintaining some connection to a research question area or topic of interest. The rest of the chapter assumes the employment of this form.

Creating an Interview Guide

Your interview guide is the instrument used to bridge your research question(s) and what the people you are interviewing want to tell you. Unlike a standardized questionnaire, the questions actually asked do not need to be exactly what you have written down in your guide. The guide is meant to create space for those you are interviewing to talk about the phenomenon of interest, but sometimes you are not even sure what that phenomenon is until you start asking questions. A priority in creating an interview guide is to ensure it offers space. One of the worst mistakes is to create questions that are so specific that the person answering them will not stray. Relatedly, questions that sound “academic” will shut down a lot of respondents. A good interview guide invites respondents to talk about what is important to them, not feel like they are performing or being evaluated by you.

Good interview questions should not sound like your “research question” at all. For example, let’s say your research question is “How do patriarchal assumptions influence men’s understanding of climate change and responses to climate change?” It would be worse than unhelpful to ask a respondent, “How do your assumptions about the role of men affect your understanding of climate change?” You need to unpack this into manageable nuggets that pull your respondent into the area of interest without leading him anywhere. You could start by asking him what he thinks about climate change in general. Or, even better, whether he has any concerns about heatwaves or increased tornadoes or polar icecaps melting. Once he starts talking about that, you can ask follow-up questions that bring in issues around gendered roles, perhaps asking if he is married (to a woman) and whether his wife shares his thoughts and, if not, how they negotiate that difference. The fact is, you won’t really know the right questions to ask until he starts talking.

There are several distinct types of questions that can be used in your interview guide, either as main questions or as follow-up probes. If you remember that the point is to leave space for the respondent, you will craft a much more effective interview guide! You will also want to think about the place of time in both the questions themselves (past, present, future orientations) and the sequencing of the questions.

Researcher Note

Suggestion : As you read the next three sections (types of questions, temporality, question sequence), have in mind a particular research question, and try to draft questions and sequence them in a way that opens space for a discussion that helps you answer your research question.

Type of Questions

Experience and behavior questions ask about what a respondent does regularly (their behavior) or has done (their experience). These are relatively easy questions for people to answer because they appear more “factual” and less subjective. This makes them good opening questions. For the study on climate change above, you might ask, “Have you ever experienced an unusual weather event? What happened?” Or “You said you work outside? What is a typical summer workday like for you? How do you protect yourself from the heat?”

Opinion and values questions , in contrast, ask questions that get inside the minds of those you are interviewing. “Do you think climate change is real? Who or what is responsible for it?” are two such questions. Note that you don’t have to literally ask, “What is your opinion of X?” but you can find a way to ask the specific question relevant to the conversation you are having. These questions are a bit trickier to ask because the answers you get may depend in part on how your respondent perceives you and whether they want to please you or not. We’ve talked a fair amount about being reflective. Here is another place where this comes into play. You need to be aware of the effect your presence might have on the answers you are receiving and adjust accordingly. If you are a woman who is perceived as liberal asking a man who identifies as conservative about climate change, there is a lot of subtext that can be going on in the interview. There is no one right way to resolve this, but you must at least be aware of it.

Feeling questions are questions that ask respondents to draw on their emotional responses. It’s pretty common for academic researchers to forget that we have bodies and emotions, but people’s understandings of the world often operate at this affective level, sometimes unconsciously or barely consciously. It is a good idea to include questions that leave space for respondents to remember, imagine, or relive emotional responses to particular phenomena. “What was it like when you heard your cousin’s house burned down in that wildfire?” doesn’t explicitly use any emotion words, but it allows your respondent to remember what was probably a pretty emotional day. And if they respond emotionally neutral, that is pretty interesting data too. Note that asking someone “How do you feel about X” is not always going to evoke an emotional response, as they might simply turn around and respond with “I think that…” It is better to craft a question that actually pushes the respondent into the affective category. This might be a specific follow-up to an experience and behavior question —for example, “You just told me about your daily routine during the summer heat. Do you worry it is going to get worse?” or “Have you ever been afraid it will be too hot to get your work accomplished?”

Knowledge questions ask respondents what they actually know about something factual. We have to be careful when we ask these types of questions so that respondents do not feel like we are evaluating them (which would shut them down), but, for example, it is helpful to know when you are having a conversation about climate change that your respondent does in fact know that unusual weather events have increased and that these have been attributed to climate change! Asking these questions can set the stage for deeper questions and can ensure that the conversation makes the same kind of sense to both participants. For example, a conversation about political polarization can be put back on track once you realize that the respondent doesn’t really have a clear understanding that there are two parties in the US. Instead of asking a series of questions about Republicans and Democrats, you might shift your questions to talk more generally about political disagreements (e.g., “people against abortion”). And sometimes what you do want to know is the level of knowledge about a particular program or event (e.g., “Are you aware you can discharge your student loans through the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program?”).

Sensory questions call on all senses of the respondent to capture deeper responses. These are particularly helpful in sparking memory. “Think back to your childhood in Eastern Oregon. Describe the smells, the sounds…” Or you could use these questions to help a person access the full experience of a setting they customarily inhabit: “When you walk through the doors to your office building, what do you see? Hear? Smell?” As with feeling questions , these questions often supplement experience and behavior questions . They are another way of allowing your respondent to report fully and deeply rather than remain on the surface.

Creative questions employ illustrative examples, suggested scenarios, or simulations to get respondents to think more deeply about an issue, topic, or experience. There are many options here. In The Trouble with Passion , Erin Cech ( 2021 ) provides a scenario in which “Joe” is trying to decide whether to stay at his decent but boring computer job or follow his passion by opening a restaurant. She asks respondents, “What should Joe do?” Their answers illuminate the attraction of “passion” in job selection. In my own work, I have used a news story about an upwardly mobile young man who no longer has time to see his mother and sisters to probe respondents’ feelings about the costs of social mobility. Jessi Streib and Betsy Leondar-Wright have used single-page cartoon “scenes” to elicit evaluations of potential racial discrimination, sexual harassment, and classism. Barbara Sutton ( 2010 ) has employed lists of words (“strong,” “mother,” “victim”) on notecards she fans out and asks her female respondents to select and discuss.

Background/Demographic Questions

You most definitely will want to know more about the person you are interviewing in terms of conventional demographic information, such as age, race, gender identity, occupation, and educational attainment. These are not questions that normally open up inquiry. [1] For this reason, my practice has been to include a separate “demographic questionnaire” sheet that I ask each respondent to fill out at the conclusion of the interview. Only include those aspects that are relevant to your study. For example, if you are not exploring religion or religious affiliation, do not include questions about a person’s religion on the demographic sheet. See the example provided at the end of this chapter.

Temporality

Any type of question can have a past, present, or future orientation. For example, if you are asking a behavior question about workplace routine, you might ask the respondent to talk about past work, present work, and ideal (future) work. Similarly, if you want to understand how people cope with natural disasters, you might ask your respondent how they felt then during the wildfire and now in retrospect and whether and to what extent they have concerns for future wildfire disasters. It’s a relatively simple suggestion—don’t forget to ask about past, present, and future—but it can have a big impact on the quality of the responses you receive.

Question Sequence

Having a list of good questions or good question areas is not enough to make a good interview guide. You will want to pay attention to the order in which you ask your questions. Even though any one respondent can derail this order (perhaps by jumping to answer a question you haven’t yet asked), a good advance plan is always helpful. When thinking about sequence, remember that your goal is to get your respondent to open up to you and to say things that might surprise you. To establish rapport, it is best to start with nonthreatening questions. Asking about the present is often the safest place to begin, followed by the past (they have to know you a little bit to get there), and lastly, the future (talking about hopes and fears requires the most rapport). To allow for surprises, it is best to move from very general questions to more particular questions only later in the interview. This ensures that respondents have the freedom to bring up the topics that are relevant to them rather than feel like they are constrained to answer you narrowly. For example, refrain from asking about particular emotions until these have come up previously—don’t lead with them. Often, your more particular questions will emerge only during the course of the interview, tailored to what is emerging in conversation.

Once you have a set of questions, read through them aloud and imagine you are being asked the same questions. Does the set of questions have a natural flow? Would you be willing to answer the very first question to a total stranger? Does your sequence establish facts and experiences before moving on to opinions and values? Did you include prefatory statements, where necessary; transitions; and other announcements? These can be as simple as “Hey, we talked a lot about your experiences as a barista while in college.… Now I am turning to something completely different: how you managed friendships in college.” That is an abrupt transition, but it has been softened by your acknowledgment of that.

Probes and Flexibility

Once you have the interview guide, you will also want to leave room for probes and follow-up questions. As in the sample probe included here, you can write out the obvious probes and follow-up questions in advance. You might not need them, as your respondent might anticipate them and include full responses to the original question. Or you might need to tailor them to how your respondent answered the question. Some common probes and follow-up questions include asking for more details (When did that happen? Who else was there?), asking for elaboration (Could you say more about that?), asking for clarification (Does that mean what I think it means or something else? I understand what you mean, but someone else reading the transcript might not), and asking for contrast or comparison (How did this experience compare with last year’s event?). “Probing is a skill that comes from knowing what to look for in the interview, listening carefully to what is being said and what is not said, and being sensitive to the feedback needs of the person being interviewed” ( Patton 2002:374 ). It takes work! And energy. I and many other interviewers I know report feeling emotionally and even physically drained after conducting an interview. You are tasked with active listening and rearranging your interview guide as needed on the fly. If you only ask the questions written down in your interview guide with no deviations, you are doing it wrong. [2]

The Final Question

Every interview guide should include a very open-ended final question that allows for the respondent to say whatever it is they have been dying to tell you but you’ve forgotten to ask. About half the time they are tired too and will tell you they have nothing else to say. But incredibly, some of the most honest and complete responses take place here, at the end of a long interview. You have to realize that the person being interviewed is often discovering things about themselves as they talk to you and that this process of discovery can lead to new insights for them. Making space at the end is therefore crucial. Be sure you convey that you actually do want them to tell you more, that the offer of “anything else?” is not read as an empty convention where the polite response is no. Here is where you can pull from that active listening and tailor the final question to the particular person. For example, “I’ve asked you a lot of questions about what it was like to live through that wildfire. I’m wondering if there is anything I’ve forgotten to ask, especially because I haven’t had that experience myself” is a much more inviting final question than “Great. Anything you want to add?” It’s also helpful to convey to the person that you have the time to listen to their full answer, even if the allotted time is at the end. After all, there are no more questions to ask, so the respondent knows exactly how much time is left. Do them the courtesy of listening to them!

Conducting the Interview

Once you have your interview guide, you are on your way to conducting your first interview. I always practice my interview guide with a friend or family member. I do this even when the questions don’t make perfect sense for them, as it still helps me realize which questions make no sense, are poorly worded (too academic), or don’t follow sequentially. I also practice the routine I will use for interviewing, which goes something like this:

- Introduce myself and reintroduce the study

- Provide consent form and ask them to sign and retain/return copy

- Ask if they have any questions about the study before we begin

- Ask if I can begin recording

- Ask questions (from interview guide)

- Turn off the recording device

- Ask if they are willing to fill out my demographic questionnaire

- Collect questionnaire and, without looking at the answers, place in same folder as signed consent form

- Thank them and depart

A note on remote interviewing: Interviews have traditionally been conducted face-to-face in a private or quiet public setting. You don’t want a lot of background noise, as this will make transcriptions difficult. During the recent global pandemic, many interviewers, myself included, learned the benefits of interviewing remotely. Although face-to-face is still preferable for many reasons, Zoom interviewing is not a bad alternative, and it does allow more interviews across great distances. Zoom also includes automatic transcription, which significantly cuts down on the time it normally takes to convert our conversations into “data” to be analyzed. These automatic transcriptions are not perfect, however, and you will still need to listen to the recording and clarify and clean up the transcription. Nor do automatic transcriptions include notations of body language or change of tone, which you may want to include. When interviewing remotely, you will want to collect the consent form before you meet: ask them to read, sign, and return it as an email attachment. I think it is better to ask for the demographic questionnaire after the interview, but because some respondents may never return it then, it is probably best to ask for this at the same time as the consent form, in advance of the interview.

What should you bring to the interview? I would recommend bringing two copies of the consent form (one for you and one for the respondent), a demographic questionnaire, a manila folder in which to place the signed consent form and filled-out demographic questionnaire, a printed copy of your interview guide (I print with three-inch right margins so I can jot down notes on the page next to relevant questions), a pen, a recording device, and water.

After the interview, you will want to secure the signed consent form in a locked filing cabinet (if in print) or a password-protected folder on your computer. Using Excel or a similar program that allows tables/spreadsheets, create an identifying number for your interview that links to the consent form without using the name of your respondent. For example, let’s say that I conduct interviews with US politicians, and the first person I meet with is George W. Bush. I will assign the transcription the number “INT#001” and add it to the signed consent form. [3] The signed consent form goes into a locked filing cabinet, and I never use the name “George W. Bush” again. I take the information from the demographic sheet, open my Excel spreadsheet, and add the relevant information in separate columns for the row INT#001: White, male, Republican. When I interview Bill Clinton as my second interview, I include a second row: INT#002: White, male, Democrat. And so on. The only link to the actual name of the respondent and this information is the fact that the consent form (unavailable to anyone but me) has stamped on it the interview number.

Many students get very nervous before their first interview. Actually, many of us are always nervous before the interview! But do not worry—this is normal, and it does pass. Chances are, you will be pleasantly surprised at how comfortable it begins to feel. These “purposeful conversations” are often a delight for both participants. This is not to say that sometimes things go wrong. I often have my students practice several “bad scenarios” (e.g., a respondent that you cannot get to open up; a respondent who is too talkative and dominates the conversation, steering it away from the topics you are interested in; emotions that completely take over; or shocking disclosures you are ill-prepared to handle), but most of the time, things go quite well. Be prepared for the unexpected, but know that the reason interviews are so popular as a technique of data collection is that they are usually richly rewarding for both participants.

One thing that I stress to my methods students and remind myself about is that interviews are still conversations between people. If there’s something you might feel uncomfortable asking someone about in a “normal” conversation, you will likely also feel a bit of discomfort asking it in an interview. Maybe more importantly, your respondent may feel uncomfortable. Social research—especially about inequality—can be uncomfortable. And it’s easy to slip into an abstract, intellectualized, or removed perspective as an interviewer. This is one reason trying out interview questions is important. Another is that sometimes the question sounds good in your head but doesn’t work as well out loud in practice. I learned this the hard way when a respondent asked me how I would answer the question I had just posed, and I realized that not only did I not really know how I would answer it, but I also wasn’t quite as sure I knew what I was asking as I had thought.

—Elizabeth M. Lee, Associate Professor of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University, author of Class and Campus Life , and co-author of Geographies of Campus Inequality

How Many Interviews?

Your research design has included a targeted number of interviews and a recruitment plan (see chapter 5). Follow your plan, but remember that “ saturation ” is your goal. You interview as many people as you can until you reach a point at which you are no longer surprised by what they tell you. This means not that no one after your first twenty interviews will have surprising, interesting stories to tell you but rather that the picture you are forming about the phenomenon of interest to you from a research perspective has come into focus, and none of the interviews are substantially refocusing that picture. That is when you should stop collecting interviews. Note that to know when you have reached this, you will need to read your transcripts as you go. More about this in chapters 18 and 19.

Your Final Product: The Ideal Interview Transcript

A good interview transcript will demonstrate a subtly controlled conversation by the skillful interviewer. In general, you want to see replies that are about one paragraph long, not short sentences and not running on for several pages. Although it is sometimes necessary to follow respondents down tangents, it is also often necessary to pull them back to the questions that form the basis of your research study. This is not really a free conversation, although it may feel like that to the person you are interviewing.

Final Tips from an Interview Master

Annette Lareau is arguably one of the masters of the trade. In Listening to People , she provides several guidelines for good interviews and then offers a detailed example of an interview gone wrong and how it could be addressed (please see the “Further Readings” at the end of this chapter). Here is an abbreviated version of her set of guidelines: (1) interview respondents who are experts on the subjects of most interest to you (as a corollary, don’t ask people about things they don’t know); (2) listen carefully and talk as little as possible; (3) keep in mind what you want to know and why you want to know it; (4) be a proactive interviewer (subtly guide the conversation); (5) assure respondents that there aren’t any right or wrong answers; (6) use the respondent’s own words to probe further (this both allows you to accurately identify what you heard and pushes the respondent to explain further); (7) reuse effective probes (don’t reinvent the wheel as you go—if repeating the words back works, do it again and again); (8) focus on learning the subjective meanings that events or experiences have for a respondent; (9) don’t be afraid to ask a question that draws on your own knowledge (unlike trial lawyers who are trained never to ask a question for which they don’t already know the answer, sometimes it’s worth it to ask risky questions based on your hypotheses or just plain hunches); (10) keep thinking while you are listening (so difficult…and important); (11) return to a theme raised by a respondent if you want further information; (12) be mindful of power inequalities (and never ever coerce a respondent to continue the interview if they want out); (13) take control with overly talkative respondents; (14) expect overly succinct responses, and develop strategies for probing further; (15) balance digging deep and moving on; (16) develop a plan to deflect questions (e.g., let them know you are happy to answer any questions at the end of the interview, but you don’t want to take time away from them now); and at the end, (17) check to see whether you have asked all your questions. You don’t always have to ask everyone the same set of questions, but if there is a big area you have forgotten to cover, now is the time to recover ( Lareau 2021:93–103 ).

Sample: Demographic Questionnaire

ASA Taskforce on First-Generation and Working-Class Persons in Sociology – Class Effects on Career Success

Supplementary Demographic Questionnaire

Thank you for your participation in this interview project. We would like to collect a few pieces of key demographic information from you to supplement our analyses. Your answers to these questions will be kept confidential and stored by ID number. All of your responses here are entirely voluntary!

What best captures your race/ethnicity? (please check any/all that apply)

- White (Non Hispanic/Latina/o/x)

- Black or African American

- Hispanic, Latino/a/x of Spanish

- Asian or Asian American

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Middle Eastern or North African

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- Other : (Please write in: ________________)

What is your current position?

- Grad Student

- Full Professor

Please check any and all of the following that apply to you:

- I identify as a working-class academic

- I was the first in my family to graduate from college

- I grew up poor

What best reflects your gender?

- Transgender female/Transgender woman

- Transgender male/Transgender man

- Gender queer/ Gender nonconforming

Anything else you would like us to know about you?

Example: Interview Guide

In this example, follow-up prompts are italicized. Note the sequence of questions. That second question often elicits an entire life history , answering several later questions in advance.

Introduction Script/Question

Thank you for participating in our survey of ASA members who identify as first-generation or working-class. As you may have heard, ASA has sponsored a taskforce on first-generation and working-class persons in sociology and we are interested in hearing from those who so identify. Your participation in this interview will help advance our knowledge in this area.

- The first thing we would like to as you is why you have volunteered to be part of this study? What does it mean to you be first-gen or working class? Why were you willing to be interviewed?

- How did you decide to become a sociologist?

- Can you tell me a little bit about where you grew up? ( prompts: what did your parent(s) do for a living? What kind of high school did you attend?)

- Has this identity been salient to your experience? (how? How much?)

- How welcoming was your grad program? Your first academic employer?

- Why did you decide to pursue sociology at the graduate level?

- Did you experience culture shock in college? In graduate school?

- Has your FGWC status shaped how you’ve thought about where you went to school? debt? etc?

- Were you mentored? How did this work (not work)? How might it?

- What did you consider when deciding where to go to grad school? Where to apply for your first position?

- What, to you, is a mark of career success? Have you achieved that success? What has helped or hindered your pursuit of success?

- Do you think sociology, as a field, cares about prestige?

- Let’s talk a little bit about intersectionality. How does being first-gen/working class work alongside other identities that are important to you?

- What do your friends and family think about your career? Have you had any difficulty relating to family members or past friends since becoming highly educated?

- Do you have any debt from college/grad school? Are you concerned about this? Could you explain more about how you paid for college/grad school? (here, include assistance from family, fellowships, scholarships, etc.)

- (You’ve mentioned issues or obstacles you had because of your background.) What could have helped? Or, who or what did? Can you think of fortuitous moments in your career?

- Do you have any regrets about the path you took?

- Is there anything else you would like to add? Anything that the Taskforce should take note of, that we did not ask you about here?

Further Readings

Britten, Nicky. 1995. “Qualitative Interviews in Medical Research.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 31(6999):251–253. A good basic overview of interviewing particularly useful for students of public health and medical research generally.

Corbin, Juliet, and Janice M. Morse. 2003. “The Unstructured Interactive Interview: Issues of Reciprocity and Risks When Dealing with Sensitive Topics.” Qualitative Inquiry 9(3):335–354. Weighs the potential benefits and harms of conducting interviews on topics that may cause emotional distress. Argues that the researcher’s skills and code of ethics should ensure that the interviewing process provides more of a benefit to both participant and researcher than a harm to the former.

Gerson, Kathleen, and Sarah Damaske. 2020. The Science and Art of Interviewing . New York: Oxford University Press. A useful guidebook/textbook for both undergraduates and graduate students, written by sociologists.

Kvale, Steiner. 2007. Doing Interviews . London: SAGE. An easy-to-follow guide to conducting and analyzing interviews by psychologists.

Lamont, Michèle, and Ann Swidler. 2014. “Methodological Pluralism and the Possibilities and Limits of Interviewing.” Qualitative Sociology 37(2):153–171. Written as a response to various debates surrounding the relative value of interview-based studies and ethnographic studies defending the particular strengths of interviewing. This is a must-read article for anyone seriously engaging in qualitative research!

Pugh, Allison J. 2013. “What Good Are Interviews for Thinking about Culture? Demystifying Interpretive Analysis.” American Journal of Cultural Sociology 1(1):42–68. Another defense of interviewing written against those who champion ethnographic methods as superior, particularly in the area of studying culture. A classic.

Rapley, Timothy John. 2001. “The ‘Artfulness’ of Open-Ended Interviewing: Some considerations in analyzing interviews.” Qualitative Research 1(3):303–323. Argues for the importance of “local context” of data production (the relationship built between interviewer and interviewee, for example) in properly analyzing interview data.

Weiss, Robert S. 1995. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies . New York: Simon and Schuster. A classic and well-regarded textbook on interviewing. Because Weiss has extensive experience conducting surveys, he contrasts the qualitative interview with the survey questionnaire well; particularly useful for those trained in the latter.

- I say “normally” because how people understand their various identities can itself be an expansive topic of inquiry. Here, I am merely talking about collecting otherwise unexamined demographic data, similar to how we ask people to check boxes on surveys. ↵

- Again, this applies to “semistructured in-depth interviewing.” When conducting standardized questionnaires, you will want to ask each question exactly as written, without deviations! ↵

- I always include “INT” in the number because I sometimes have other kinds of data with their own numbering: FG#001 would mean the first focus group, for example. I also always include three-digit spaces, as this allows for up to 999 interviews (or, more realistically, allows for me to interview up to one hundred persons without having to reset my numbering system). ↵

A method of data collection in which the researcher asks the participant questions; the answers to these questions are often recorded and transcribed verbatim. There are many different kinds of interviews - see also semistructured interview , structured interview , and unstructured interview .

A document listing key questions and question areas for use during an interview. It is used most often for semi-structured interviews. A good interview guide may have no more than ten primary questions for two hours of interviewing, but these ten questions will be supplemented by probes and relevant follow-ups throughout the interview. Most IRBs require the inclusion of the interview guide in applications for review. See also interview and semi-structured interview .

A data-collection method that relies on casual, conversational, and informal interviewing. Despite its apparent conversational nature, the researcher usually has a set of particular questions or question areas in mind but allows the interview to unfold spontaneously. This is a common data-collection technique among ethnographers. Compare to the semi-structured or in-depth interview .

A form of interview that follows a standard guide of questions asked, although the order of the questions may change to match the particular needs of each individual interview subject, and probing “follow-up” questions are often added during the course of the interview. The semi-structured interview is the primary form of interviewing used by qualitative researchers in the social sciences. It is sometimes referred to as an “in-depth” interview. See also interview and interview guide .

The cluster of data-collection tools and techniques that involve observing interactions between people, the behaviors, and practices of individuals (sometimes in contrast to what they say about how they act and behave), and cultures in context. Observational methods are the key tools employed by ethnographers and Grounded Theory .

Follow-up questions used in a semi-structured interview to elicit further elaboration. Suggested prompts can be included in the interview guide to be used/deployed depending on how the initial question was answered or if the topic of the prompt does not emerge spontaneously.

A form of interview that follows a strict set of questions, asked in a particular order, for all interview subjects. The questions are also the kind that elicits short answers, and the data is more “informative” than probing. This is often used in mixed-methods studies, accompanying a survey instrument. Because there is no room for nuance or the exploration of meaning in structured interviews, qualitative researchers tend to employ semi-structured interviews instead. See also interview.

The point at which you can conclude data collection because every person you are interviewing, the interaction you are observing, or content you are analyzing merely confirms what you have already noted. Achieving saturation is often used as the justification for the final sample size.

An interview variant in which a person’s life story is elicited in a narrative form. Turning points and key themes are established by the researcher and used as data points for further analysis.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Library Guides

Dissertations 4: methodology: methods.

- Introduction & Philosophy

- Methodology

Primary & Secondary Sources, Primary & Secondary Data

When describing your research methods, you can start by stating what kind of secondary and, if applicable, primary sources you used in your research. Explain why you chose such sources, how well they served your research, and identify possible issues encountered using these sources.

Definitions

There is some confusion on the use of the terms primary and secondary sources, and primary and secondary data. The confusion is also due to disciplinary differences (Lombard 2010). Whilst you are advised to consult the research methods literature in your field, we can generalise as follows:

Secondary sources

Secondary sources normally include the literature (books and articles) with the experts' findings, analysis and discussions on a certain topic (Cottrell, 2014, p123). Secondary sources often interpret primary sources.

Primary sources

Primary sources are "first-hand" information such as raw data, statistics, interviews, surveys, law statutes and law cases. Even literary texts, pictures and films can be primary sources if they are the object of research (rather than, for example, documentaries reporting on something else, in which case they would be secondary sources). The distinction between primary and secondary sources sometimes lies on the use you make of them (Cottrell, 2014, p123).

Primary data

Primary data are data (primary sources) you directly obtained through your empirical work (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill 2015, p316).

Secondary data

Secondary data are data (primary sources) that were originally collected by someone else (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill 2015, p316).

Comparison between primary and secondary data

Use

Virtually all research will use secondary sources, at least as background information.

Often, especially at the postgraduate level, it will also use primary sources - secondary and/or primary data. The engagement with primary sources is generally appreciated, as less reliant on others' interpretations, and closer to 'facts'.

The use of primary data, as opposed to secondary data, demonstrates the researcher's effort to do empirical work and find evidence to answer her specific research question and fulfill her specific research objectives. Thus, primary data contribute to the originality of the research.

Ultimately, you should state in this section of the methodology:

What sources and data you are using and why (how are they going to help you answer the research question and/or test the hypothesis.

If using primary data, why you employed certain strategies to collect them.

What the advantages and disadvantages of your strategies to collect the data (also refer to the research in you field and research methods literature).

Quantitative, Qualitative & Mixed Methods

The methodology chapter should reference your use of quantitative research, qualitative research and/or mixed methods. The following is a description of each along with their advantages and disadvantages.

Quantitative research

Quantitative research uses numerical data (quantities) deriving, for example, from experiments, closed questions in surveys, questionnaires, structured interviews or published data sets (Cottrell, 2014, p93). It normally processes and analyses this data using quantitative analysis techniques like tables, graphs and statistics to explore, present and examine relationships and trends within the data (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill, 2015, p496).

Qualitative research

Qualitative research is generally undertaken to study human behaviour and psyche. It uses methods like in-depth case studies, open-ended survey questions, unstructured interviews, focus groups, or unstructured observations (Cottrell, 2014, p93). The nature of the data is subjective, and also the analysis of the researcher involves a degree of subjective interpretation. Subjectivity can be controlled for in the research design, or has to be acknowledged as a feature of the research. Subject-specific books on (qualitative) research methods offer guidance on such research designs.

Mixed methods

Mixed-method approaches combine both qualitative and quantitative methods, and therefore combine the strengths of both types of research. Mixed methods have gained popularity in recent years.

When undertaking mixed-methods research you can collect the qualitative and quantitative data either concurrently or sequentially. If sequentially, you can for example, start with a few semi-structured interviews, providing qualitative insights, and then design a questionnaire to obtain quantitative evidence that your qualitative findings can also apply to a wider population (Specht, 2019, p138).

Ultimately, your methodology chapter should state:

Whether you used quantitative research, qualitative research or mixed methods.

Why you chose such methods (and refer to research method sources).

Why you rejected other methods.

How well the method served your research.

The problems or limitations you encountered.

Doug Specht, Senior Lecturer at the Westminster School of Media and Communication, explains mixed methods research in the following video:

LinkedIn Learning Video on Academic Research Foundations: Quantitative

The video covers the characteristics of quantitative research, and explains how to approach different parts of the research process, such as creating a solid research question and developing a literature review. He goes over the elements of a study, explains how to collect and analyze data, and shows how to present your data in written and numeric form.

Link to quantitative research video

Some Types of Methods

There are several methods you can use to get primary data. To reiterate, the choice of the methods should depend on your research question/hypothesis.

Whatever methods you will use, you will need to consider:

why did you choose one technique over another? What were the advantages and disadvantages of the technique you chose?

what was the size of your sample? Who made up your sample? How did you select your sample population? Why did you choose that particular sampling strategy?)

ethical considerations (see also tab...)

safety considerations

validity

feasibility

recording

procedure of the research (see box procedural method...).

Check Stella Cottrell's book Dissertations and Project Reports: A Step by Step Guide for some succinct yet comprehensive information on most methods (the following account draws mostly on her work). Check a research methods book in your discipline for more specific guidance.

Experiments

Experiments are useful to investigate cause and effect, when the variables can be tightly controlled. They can test a theory or hypothesis in controlled conditions. Experiments do not prove or disprove an hypothesis, instead they support or not support an hypothesis. When using the empirical and inductive method it is not possible to achieve conclusive results. The results may only be valid until falsified by other experiments and observations.

For more information on Scientific Method, click here .

Observations

Observational methods are useful for in-depth analyses of behaviours in people, animals, organisations, events or phenomena. They can test a theory or products in real life or simulated settings. They generally a qualitative research method.

Questionnaires and surveys

Questionnaires and surveys are useful to gain opinions, attitudes, preferences, understandings on certain matters. They can provide quantitative data that can be collated systematically; qualitative data, if they include opportunities for open-ended responses; or both qualitative and quantitative elements.

Interviews

Interviews are useful to gain rich, qualitative information about individuals' experiences, attitudes or perspectives. With interviews you can follow up immediately on responses for clarification or further details. There are three main types of interviews: structured (following a strict pattern of questions, which expect short answers), semi-structured (following a list of questions, with the opportunity to follow up the answers with improvised questions), and unstructured (following a short list of broad questions, where the respondent can lead more the conversation) (Specht, 2019, p142).

This short video on qualitative interviews discusses best practices and covers qualitative interview design, preparation and data collection methods.

Focus groups

In this case, a group of people (normally, 4-12) is gathered for an interview where the interviewer asks questions to such group of participants. Group interactions and discussions can be highly productive, but the researcher has to beware of the group effect, whereby certain participants and views dominate the interview (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill 2015, p419). The researcher can try to minimise this by encouraging involvement of all participants and promoting a multiplicity of views.

This video focuses on strategies for conducting research using focus groups.

Check out the guidance on online focus groups by Aliaksandr Herasimenka, which is attached at the bottom of this text box.

Case study

Case studies are often a convenient way to narrow the focus of your research by studying how a theory or literature fares with regard to a specific person, group, organisation, event or other type of entity or phenomenon you identify. Case studies can be researched using other methods, including those described in this section. Case studies give in-depth insights on the particular reality that has been examined, but may not be representative of what happens in general, they may not be generalisable, and may not be relevant to other contexts. These limitations have to be acknowledged by the researcher.

Content analysis

Content analysis consists in the study of words or images within a text. In its broad definition, texts include books, articles, essays, historical documents, speeches, conversations, advertising, interviews, social media posts, films, theatre, paintings or other visuals. Content analysis can be quantitative (e.g. word frequency) or qualitative (e.g. analysing intention and implications of the communication). It can detect propaganda, identify intentions of writers, and can see differences in types of communication (Specht, 2019, p146). Check this page on collecting, cleaning and visualising Twitter data.

Extra links and resources:

Research Methods

A clear and comprehensive overview of research methods by Emerald Publishing. It includes: crowdsourcing as a research tool; mixed methods research; case study; discourse analysis; ground theory; repertory grid; ethnographic method and participant observation; interviews; focus group; action research; analysis of qualitative data; survey design; questionnaires; statistics; experiments; empirical research; literature review; secondary data and archival materials; data collection.

Doing your dissertation during the COVID-19 pandemic

Resources providing guidance on doing dissertation research during the pandemic: Online research methods; Secondary data sources; Webinars, conferences and podcasts;

- Virtual Focus Groups Guidance on managing virtual focus groups

5 Minute Methods Videos

The following are a series of useful videos that introduce research methods in five minutes. These resources have been produced by lecturers and students with the University of Westminster's School of Media and Communication.

Case Study Research

Research Ethics

Quantitative Content Analysis

Sequential Analysis

Qualitative Content Analysis

Thematic Analysis

Social Media Research

Mixed Method Research

Procedural Method

In this part, provide an accurate, detailed account of the methods and procedures that were used in the study or the experiment (if applicable!).

Include specifics about participants, sample, materials, design and methods.

If the research involves human subjects, then include a detailed description of who and how many participated along with how the participants were selected.

Describe all materials used for the study, including equipment, written materials and testing instruments.

Identify the study's design and any variables or controls employed.

Write out the steps in the order that they were completed.

Indicate what participants were asked to do, how measurements were taken and any calculations made to raw data collected.

Specify statistical techniques applied to the data to reach your conclusions.

Provide evidence that you incorporated rigor into your research. This is the quality of being thorough and accurate and considers the logic behind your research design.

Highlight any drawbacks that may have limited your ability to conduct your research thoroughly.

You have to provide details to allow others to replicate the experiment and/or verify the data, to test the validity of the research.

Bibliography

Cottrell, S. (2014). Dissertations and project reports: a step by step guide. Hampshire, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lombard, E. (2010). Primary and secondary sources. The Journal of Academic Librarianship , 36(3), 250-253

Saunders, M.N.K., Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A. (2015). Research Methods for Business Students. New York: Pearson Education.

Specht, D. (2019). The Media And Communications Study Skills Student Guide . London: University of Westminster Press.

- << Previous: Introduction & Philosophy

- Next: Ethics >>

- Last Updated: Sep 14, 2022 12:58 PM

- URL: https://libguides.westminster.ac.uk/methodology-for-dissertations

CONNECT WITH US

How To Write The Results/Findings Chapter

For qualitative studies (dissertations & theses).

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD). Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2021

So, you’ve collected and analysed your qualitative data, and it’s time to write up your results chapter. But where do you start? In this post, we’ll guide you through the qualitative results chapter (also called the findings chapter), step by step.

Overview: Qualitative Results Chapter

- What (exactly) the qualitative results chapter is

- What to include in your results chapter

- How to write up your results chapter

- A few tips and tricks to help you along the way

- Free results chapter template

What exactly is the results chapter?