Your Guide to the Prepared Environment in Montessori

What is the Prepared Environment?

What are the elements of a prepared environment.

- socialization

- exploration/learning

The teacher's or parent's role in preparing the environment

- cleanliness

- living plants

- small furniture

- art at child's eye level

- neutral walls and furnishing

- variety of natural textures in furnishings and materials

- ample open space

- designated place for personal items (shoes, jacket, ect)

- designated place for completed art projects

- low shelving

Why is the prepared environment so important in Montessori?

Sharing is caring!

What is the Absorbent Mind? — The Montessori-Minded Mom

Thursday 8th of October 2020

[…] you’ll notice about a Montessori learning area is the way it is meticulously prepared. The preparation of the environment is so that a child can explore the materials […]

The Planes of Development in Montessori — The Montessori-Minded Mom

[…] and Montessori homeschooling parents invest time in preparing an environment that allows children to experience things of their own interests, and at their own pace. Parents […]

The Global Montessori Network

- What is a Prepared Montessori Environment?

This video lesson is designed for parents to guide them about the Montessori-prepared environment and its principles and benefits.

What is a Montessori Prepared Environment?

Dr. Maria Montessori believed that a child should be provided an environment to facilitate maximum independent learning and exploration; thus, named it as “Prepared environment.”

Therefore, a Montessori-prepared environment is an organized, clean, spacious, warm, safe, and inviting space that helps children learn from the activities prepared to tailor their development needs.

In a Montessori classroom, lessons, activities, and teaching tools are visually appealing and are tailored to meet every child’s developmental needs and interests. Each child is allowed to choose the lessons they want to learn. The furniture is child-sized and activities are kept at the eye level of children.

With a prepared environment, each child gets the freedom to develop their unique potential through appropriate learning materials and activities. These materials are realistic and easy to use. It ranges from simple to complex and concrete to abstract, catering to every child’s age, ability, and independence.

Montessori teachers act more than just as guides. They are responsible for preparing the lessons, and the environment. They are also responsible for maintaining a healthy environment and assisting with behavioral interventions.

The Montessori-prepared environment greatly differs from that of conventional education, here a child experiences a combination of freedom and self-discipline, as guided by the environment.

The Prepared Environment is composed of six aspects, or principles: Freedom, Structure and Order, Beauty, Nature and Reality, Social Environment, and Intellectual Environment.

6 Principles of Montessori Prepared Environment

There are 6 basic principles or aspects or characteristics of a prepared environment in a Montessori school: freedom, structure and order, beauty, nature and reality, social environment and intellectual environment.

“The first aim of the prepared environment is, as far as it is possible, to render the growing child independent of the adult.” – Maria Montessori

Children in a Montessori-prepared environment have freedom of choice, movement, and interaction. It means a child can explore, learn, move around, observe, and engage socially. Children are allowed to make choices of what they want to learn and with whom they want to learn.

Structure and Order:

This principle refers to how the universe functions and its structure and order . A child understands the order of their surroundings and relates to the world around them. In a Montessori classroom, a routine is followed and children know what to expect and how to be confident and organized. The baseline of their realizations is their classroom.

Montessori classrooms are clean, uncluttered, in order, and have a neutral color palette. The Montessori materials are made up of natural materials and are beautifully displayed on the shelf, accessible to the children. The classroom also has windows to get natural light and potted plants to bring positivity to them. This beautiful overall layout is inviting and is meant to inspire tranquility when compared to conventional classrooms .

Nature and Reality:

The cornerstone of Montessori education is interacting with the world around you. It is because of Montessori’s belief that children can learn more from nature than from a book that nature is incorporated into prepared environments.

Nature inspires children. Therefore, children are invited to play outside and interact with nature. They use learning materials made of natural wood, metal, bamboo, cotton, and glass rather than synthetics or plastics. These materials are child-friendly so that the child can work with them independently. Montessori activities use real objects such as sewing with a needle, transferring beans using a spoon, and many more to keep the child close to nature.

Social Environment:

In a Montessori school, a prepared environment is more than the classroom setting. The prepared environment supports the social and emotional development of the child by encouraging freedom of interaction. Through Montessori learning, children develop empathy for others and a sense of compassion . Children are encouraged to learn grace and courtesy with the help of a multi-age classroom setting.

Intellectual Environment:

To achieve intellectual excellence, all the above five principles should be fulfilled. The ultimate goal of Montessori education is to develop the overall personality of the child using five key areas of the Montessori curriculum ( Sensorial , Practical life, Mathematics , Science, and Culture). In addition to fostering cognitive development , the above principles also provide an infinite amount of learning and growth opportunities for the child.

Montessori education spends a great deal of time and effort to plan and develop a prepared environment for each class level. The environment is prepared by keeping the development needs of each child in mind and providing them with appropriate materials and opportunities to explore, learn, and grow. Thus, helping children succeed in life .

Watch the video to know more about the importance and benefits of a “Prepared Montessori Environment”.

Related Video Resources

- Positive Parenting Strategy and Tips

- Montessori Silence Game

- Montessori Materials

- Sensitive Periods

To learn more about Montessori education, click here .

Video created by Aishwarya | I teach I learn

Parents | Montessori at Home | What is a Prepared Montessori Environment? (English)

This video has been added and used with the author’s permission. It is also available on the author’s YouTube, here .

- What are the 6 principles of a Montessori prepared environment?

The prepared environment of the Montessori classroom includes six basic components or principles: freedom, structure and order, beauty, nature and reality, social environment, and lastly intellectual environment.

- What are the benefits of the Montessori prepared environment?

A prepared environment gives every child the freedom to develop their unique potential through developmentally appropriate activities or materials. The materials range from simple to complex and from concrete to abstract, catering to every child’s age and ability.

- about montessori

- Montessori at home

- Montessori education

- Why Montessori

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

- Support the Library Consider a gift today.

- Office of the Dean Meet the leadership team.

- Commitment to DEIAJ Fostering a culture of inclusivity

- Strategic Initiatives Committed to creating an inclusive, innovative library.

- News & Events Stay updated with what's happening.

- Welcome Get to know us.

- Staff Directory Find who you're looking for.

- Hours Find hours for our libraries.

- Provost's Library Advisory Committee Faculty and student advisory committee.

- Exhibits Visit our exhibit galleries.

- Waterbury Campus Library Waterbury Campus

- Law Library Thomas J. Meskill Law Library

- Avery Point Campus Library Avery Point Campus

- Stamford Campus Library Jeremy Richard Library

- Homer Babbidge Library Storrs Campus

- Archives & Special Collections Storrs Campus

- Pharmacy Library Storrs Campus

- Health Sciences Library UConn Health Sciences Library

- Music & Dramatic Arts Library Storrs Campus

- Hartford Campus Library at the Hartford Public Library

- Workshops Workshops and events offered by staff members at UConn Library.

- Scan On Demand Request scans of print items not available electronically.

- Open Education Create immersive learning experiences without financial barriers.

- Borrowing Learn about checking out materials.

- Tutoring Centers Get help from the W and Q Centers.

- Research Data Services Manage your research data effectively.

- Interlibrary Services Request materials from libraries worldwide.

- Ask a Librarian Get help online, by phone, text, or email.

- Technology Services Make and share your digital work.

- Request UConn Items Request UConn circulating items.

- Instruction Incorporate information literacy into your curriculum.

- Student Study Spaces & Meeting Rooms Find space for classes, events, or studying.

- Request a Purchase Adding an item to the collection.

- Course Reserves Request Library materials for classes.

- Subject Specialists Subject specific and departmental contacts.

- Managing Citations & Digital Files Create and manage bibliographies.

- Archives & Special Collections Dodd Center

- Scholarly Communication Discover resources for publishing and copyright.

- Greenhouse Studios Transforming scholarship in the humanities.

- Research Quick Start Quick answers to common library & research questions.

- Digital Projects Collaborative research projects.

- Research Guides Subject specific guides to resources.

- Collections Learn more about our collections.

- Databases Discover specialized research databases.

- Faculty-Authored Books Discover our program to collect faculty-authored books.

- WorldCat Find and request books and media owned by other libraries.

- New Titles @UConn Library Discover recently added resources.

- Journal Search Find journals by title and subject category.

- General Search Find articles, books, e-books, media, and more.

- Find by Citation Find journals, articles, or books from a citation.

- Connecticut Digital Archive Discover resources from CT educational, cultural, and state institutions.

- Ask a Librarian

- My Accounts

php is_front_page()=

One UConn: Welcoming you back to the UConn Library.

- Archives & Special Collections

- About Archives & Special Collections

- The American Approach to Montessori Teaching and Learning

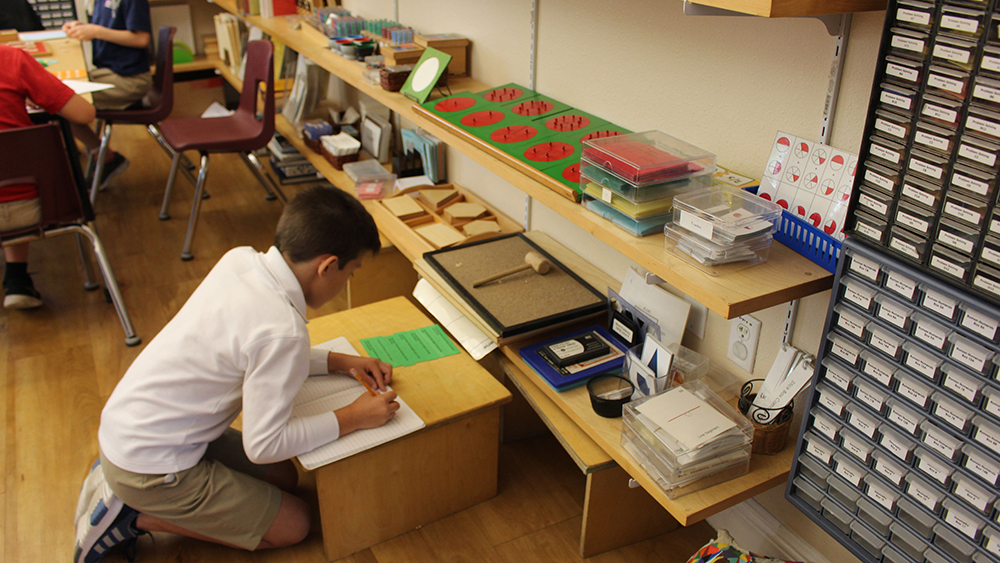

Montessori in the Classroom: The Prepared Environment

The design of a Montessori classroom, sometimes referred to as the “Prepared Environment,” is an important component of the Montessori method of education. In each Montessori classroom, the furniture and learning materials are scaled to the child. To make learning materials inviting to the child, the teacher stores them in places that are visible and easily accessible to children. Room to Learn , filmed in 1968 at the Early Learning Center in Stamford, Connecticut, describes the design and construction of a Montessori school and explains the layout of a Montessori classroom. That same year, AMS member Jane Nielson photographed Montessori classrooms all over the country. Many of the classroom elements described in “Room to Learn” are visible in her photographs.

The UConn Library is committed to making our collections fully accessible, but some older media, such as the video shown here, do not allow us to provide captions or transitions on this webpage. Contact the staff at [email protected] to ask for a transcript of this video.

In “I Can Do It Myself,” which appeared in the AMS periodical, The Constructive Triangle , Volume VI, Number 3 (Summer 1979), Eileen S. Adler explains the importance of the prepared environment to the development of a child’s independence. She notes, “If we want our children to be independent and feel that they can do it themselves, we must provide the environment that allows them this space.” Scaling the classroom to the child encouraged independent action by making activities easier for children to complete on their own and made work more comfortable. Maria Montessori explained this feature of the prepared environment in her book, Spontaneous Activity in Education (Originally translated into English in 1917):

“It is the tendency of the child actually to live by means of the things around him; he would like to use a washstand of his own, to dress himself, really to comb the hair on a living head, to sweep the floor himself; he would like to have seats, tables, sofas, clothes-pegs, and cupboards. What he desires is to work himself, to aim at some intelligent object, to have comfort in his own life. . . . We offer a very simple suggestion: give the child the environment in which everything is constructed in proportion to himself, and let him live therein.”

Montessori classrooms across the United States followed this model, with low shelves that were easily accessible to students and chairs and desks that were sized to fit the child.

Culver City

(310) 215 -3388

(323) 795-0200

(562) 291-2324

What are The Six Principles of a Montessori Prepared Environment?

- By MontessoriAcademy

- March 20, 2023

- No Comments

In Montessori education, freedom is a fundamental principle that empowers children to direct their learning. Teachers act as facilitators and guides, fostering independent thinking and self-motivation.

Freedom within limits is a key aspect of the Montessori approach. The teacher sets clear boundaries and expectations, but learners can choose their activities and pursue their interests. This promotes responsibility, self-discipline , and self-regulation, leading to a sense of confidence and autonomy.

Some of the benefits of freedom in a Montessori environment include:

- Encouraging creativity and imagination

- Promoting a love of learning

- Fostering independence and self-direction

- Developing decision-making and problem-solving skills

- Building self-esteem and confidence

2. Structure and Order

In a Montessori environment, structure and order are important principles that support learning and development. The Environment is designed to be structured and orderly, with designated areas for different activities.

Each area has appropriate materials and tools, and everything has a specific place. The order of the Environment helps to create a sense of security and confidence, allowing learners to focus on their work and making it easier for them to access the materials they need.

The benefits of structure and order in a Montessori environment are numerous. Here are some examples:

- Encouraging independence and self-direction

- Promoting concentration and focus

- Developing problem-solving and decision-making skills

- Enhancing coordination and motor skills

- Fostering a sense of responsibility and respect for materials and tools

- Supporting the development of organizational skills

3. Beauty and Atmosphere

Creating an optimal learning environment is essential in Montessori education. The physical space should be designed with aesthetics, organization, and cleanliness. The Environment should be visually appealing and stimulating, with materials encouraging creativity and imagination.

Natural elements like plants and sunlight should be included to create a calming and inviting atmosphere. A well-designed environment fosters a sense of respect and appreciation for the space and materials used, which can enhance the love for learning.

The beauty and atmosphere of the Montessori Environment provide a range of benefits to learners. Here are some examples:

- An aesthetically pleasing environment promotes creativity, imagination, and curiosity.

- A calm, peaceful atmosphere helps learners to focus and concentrate on their work.

- A clean and well-maintained environment teaches children the importance of orderliness and responsibility.

- Natural elements, such as plants, help to create a healthy learning environment by purifying the air and reducing stress levels.

- An engaging and stimulating environment enhances the learning experience, making it more enjoyable and meaningful.

4. Nature and Reality

Natural materials and real-life experiences are emphasized to promote a sense of connection to the world and foster understanding. This focus on nature and reality supports curiosity and wonder.

The natural materials in the Environment, such as plants, animals, and rocks, allow children to explore new ideas and concepts while developing their senses and imagination. Real-world experiences promote a greater understanding of material properties as well as an awareness of the Environment.

Examples of how Montessori promotes nature and reality include:

- Using real-life tasks, such as cooking or cleaning, as learning activities

- Incorporating natural materials, like plants, wood, and stone, into the learning environment

- Encouraging outdoor exploration and activities

- Using real-world examples in lessons, such as studying the solar system or learning about different cultures and their traditions.

5. Social Environment

In the Montessori approach, social interaction and cooperation are encouraged through various strategies. Mixed-age classrooms allow for peer mentoring and natural leadership development as older students take on the role of helping and supporting younger ones.

The Environment is designed to be respectful, inclusive, and supportive of diversity and cultural differences, promoting a sense of community and belonging. Teachers facilitate opportunities for group work and collaboration and model positive social behaviors and attitudes.

The Social Environment of the Montessori classroom offers numerous benefits for learners. Here are some examples:

- Opportunity for peer mentoring and leadership development

- Exposure to diverse perspectives and cultures

- Enhanced social skills such as communication, collaboration, and empathy

- Sense of community and belonging

- Increased confidence and self-esteem through group work and shared accomplishments.

6. Intellectual Environment

Various challenging and engaging activities and materials foster intellectual growth and development . The approach encourages self-directed learning, where you are given the freedom and support to explore and discover independently.

This promotes a sense of responsibility for your education and encourages critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity. The Environment is designed to be stimulating and thought-provoking, with various materials and activities catering to different learning styles and interests.

Here are some examples of the benefits of the intellectual Environment in the Montessori approach:

- Encourages self-directed learning and exploration

- Promotes critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity

- Offers a wide range of materials and activities to cater to different learning styles and interests

- Supports intellectual growth and development through challenging and engaging activities

- Helps develop a sense of responsibility for one’s education

Factors to Consider in Preparing Montessori Environment

When implementing Montessori methods, it is important to remember that they may not work equally well for every student. In order to create an environment in which all learners can thrive, there are three key considerations to keep in mind.

1. Students have different maturity levels and interests and should be allowed to choose their materials based on their preferences.

2. Some students may have disabilities or physical limitations that require specialized equipment or materials to work effectively. Teachers should be prepared to provide these accommodations.

3. Cultural background can significantly affect a student’s learning process. Teachers should strive to be culturally sensitive and encourage students to develop a global perspective that acknowledges and respects differences in beliefs, perspectives, and values.

Things To Remember

If you are considering the Montessori approach to education for your child, it is important to understand these six principles and find a Montessori school that adheres to them.

At Montessori Academy , we understand that a child’s environment plays a crucial role in their development. We strive to create a welcoming and caring atmosphere where every child feels safe and empowered to learn and discover. Our top priority is to provide a nurturing environment that fosters growth and encourages exploration.

If you have any questions or any concerns, please contact us today. We will be happy to help!

- Montessori Prepared Environment

MontessoriAcademy

Leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Copyright © 2024— All rights Reserved. Website Design by SpringHive

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Prepared Environments and Teachers: The Fundamentals of Authentic Montessori

The proper boundary of an authentic Montessori education remains a divisive issue. The fact that no clear consensus exists on a means to authenticate a school bearing the name of Montessori has led to some educators arguing in favor of broad flexibility to adapt the method for local circumstances. Others contend there must be fixed criteria to assure that all Montessori schools maintain at least some sense of consistency. This essay argues for the fixed, or non-adaptive, approach and establishes both a prepared environment with Montessori materials and the spiritual preparation of the teacher as two indispensible elements of an authentic Montessori education. This essay also explores common elements put forward by other Montessori educators as indispensible such as three-year age grouping. Despite the utility of these other elements, this essay concludes that both personal experience and extensive secondary research confirm the necessity of teacher preparation in the Montessori context. Just as we guide young children from concrete concepts to more abstract ones, this essay argues the components of authenticity move from the concrete realm of physical preparedness, to the abstract realm of being spiritually in tune with the needs of the children.

Related Papers

Betty Namuddu

Half a decade later after the passing of its founder, there are many questions about the Montessori philosophy and methodology. Can the Montessorians stay true to the views and ideals of Dr Montessori? How do you tell that a Montessori school is authentic? What is the yardstick for an authentic Montessori classroom? In my opinion, authenticity, is all about the teacher’s spiritual preparedness, and understanding of the philosophy. Drawing from different scholarly peer-reviewed research, I explain in this paper why the teacher is the most important element in preserving the authenticity of the Montessori methodology in the classroom. The teacher is the one that puts all the puzzles together (all the elements) to create an authentic Montessori classroom.

Jennifer Johnson

LaToya Jones

Dana McCabe

The question of authenticity in Montessori appears to be open to debate. Guidelines for “what makes it real” are given; most concentrate on the external. Perhaps looking inward could emphasize the most significant element of the Montessori Method: the preparation of the adult who guides the students. Sometimes refered to as a “Spiritual Transformation”, this process is an ongoing, career-long process, and takes commitment on the part of the adult to use continual self-reflection as a means to better practice.

Mitzi Jones

Maria Montessori dedicated her life’s work to observing children. Through observation and experimentation, she developed a method to meet the needs of the child at their stage of development (Abraham, 2012, p.22). She taught us that to help a child meet their fullest potential we must follow the child. As Montessori’s teachings have spread into every corner of the world, it is often met with opposition from educational leaders on every level. As teachers and school leaders try to satisfy the demands of the outside world, they often find themselves compromising the authenticity of their Montessori program. This paper explores some of the challenges experienced by Montessori practitioners, including my personal experiences.

Dayani Pieri

22,000 Montessori schools have been established worldwide within a hundred years after the inauguration of the first Montessori school in Rome. Maria Montessori expressed concern regarding the watering down of her education system and chose to train all the teachers herself. Today, scholars are still concerned about the watering down of the Montessori schools due to various reasons listed. Many have tried to express what an authentic Montessori classroom should be but have fallen short. Powell (2009) uses his solar system analogy to explain the characteristics of a Montessori classroom which fosters collaborative learning, freedom of choice, and a personal connection. AMS (2006) and Abraham (2012) both agree with Powell on these attributes, however, Abraham unlike AMS and Powell points to the lack of these characteristics to be unauthentic. AMS agrees with Powell regarding the importance of the three-year span classroom which according to Powell energizes all the other features of the environment, namely, collaborative learning, freedom of choice, and personal connection between the guide and the students. The paper concludes that if these and other characteristics put forth by AMS (2006) and Dorer (2007) are combined, it might be possible to explain authentic Montessori.

Baer Hanusz-Rajkowski

Abstract Authentic Montessori education in the 21st century poses many hopes and as many challenges when looking at the state of public and private education in the Unites States. These multiple approaches to education are hindered and compounded by the traditional one-way teacher-dictated sharing of information, then evaluated by standardized testing. On the other hand, Montessori’s approach is to meet the child where the child’s interests and abilities stand and to challenge the child to the next step. It gives the child place and space to explore limits, with the capacity to self-correct most errors. Montessori is interactive, much like the life that today’s children participate in via the internet and electronic games. It is still possible to bring authentic Montessori into the public sector by applying the Montessori Method.

Sarah Irving

Abstract Over one hundred years after Maria Montessori’s last visit to the United States of America have past, and Montessorians still cannot decide on the standards for an authentic Montessori school. More conversation is needed between Montessori teachers or guides to stop the bickering about who teaches in the most authentic school. A respectful and engaged conversation is needed to unite Montessorians and help children. I believe that authentic Montessori should have, at minimum, a certified Montessori guide, three-year multi-aged groupings, and uninterrupted work choice stimulated by intrinsic motivation.

Alyssa Dapolito

Hannah Ebner

Today’s education system is not working, and Montessori methodology holds solutions to many problems in the current paradigm. We need an overhaul, a revolution of the system. Montessorians must determine what parts of the philosophy are non-negotiable, and which parts are flexible to meet modern challenges. I argue that the spiritual, loving quality of the teacher is the fundamental aspect of Montessori that must be preserved as the method grows. The spirituality is contained in the teacher’s Montessori cosmic worldview, in the interactions between the teacher and student, as well as in the Montessori prepared environment. Many schools make compromises to the “authentic” Montessori method in today’s climate of standardized testing, parental anxiety, and district mandates. If Montessori is to be a successful remedy to our education system’s problems, the soul of Montessori must be kept intact by wise and loving teachers.

RELATED PAPERS

In vivo (Athens, Greece)

J. Talmadge

CONGRESSO …

Bruna Menezes

Editorial Biblos, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Liliana Shulman

Plural (São Paulo. Online)

Adriana Alves Loche

Applied Physics Letters

K. Jarasiunas

Science Translational Medicine

mathias hafner

DIANA PAOLA GRISALES VALENCIA

imranhossain sumon , Md. Moyazzem Hossain

Sameh Ragab

Meteoritics & Planetary Science

Jozef Masarik

Buletin Poltanesa

Imam Isti isma

Slim Bellali

American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism

James Yager

Andrea Manganaro

JAQUELINE SOTO CABELLO

International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications

I Nengah Mertayasa

Maintenance Reliability and Condition Monitoring

amit bhende

Gerd-Christian Weniger

International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing (IJCSMC)

IJCSMC Journal

Experimental Neurology

Dean Naritoku

Cardiovascular Psychiatry and Neurology

Yulia Antonenko Volkova

Carlos De La Cruz

Vajira Medical Journal (วชิรเวชสาร)

Tanattha Kittisopee

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 27 October 2017

Montessori education: a review of the evidence base

- Chloë Marshall 1

npj Science of Learning volume 2 , Article number: 11 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

342k Accesses

62 Citations

248 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

The Montessori educational method has existed for over 100 years, but evaluations of its effectiveness are scarce. This review paper has three aims, namely to (1) identify some key elements of the method, (2) review existing evaluations of Montessori education, and (3) review studies that do not explicitly evaluate Montessori education but which evaluate the key elements identified in (1). The goal of the paper is therefore to provide a review of the evidence base for Montessori education, with the dual aspirations of stimulating future research and helping teachers to better understand whether and why Montessori education might be effective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Learning to teach through noticing: a bibliometric review of teacher noticing research in mathematics education during 2006–2021

Exploration of implementation practices of Montessori education in mainland China

A meta-analysis to gauge the impact of pedagogies employed in mixed-ability high school biology classrooms

Introduction.

Maria Montessori (1870–1952) was by any measure an extraordinary individual. She initially resisted going into teaching—one of the few professions available to women in the late 19th century—and instead became one of the very first women to qualify as a medical doctor in Italy. As a doctor she specialised in psychiatry and paediatrics. While working with children with intellectual disabilities she gained the important insight that in order to learn, they required not medical treatment but rather an appropriate pedagogy. In 1900, she was given the opportunity to begin developing her pedagogy when she was appointed director of an Orthophrenic school for developmentally disabled children in Rome. When her pupils did as well in their exams as typically developing pupils and praise was lavished upon her for this achievement, she did not lap up that praise; rather, she wondered what it was about the education system in Italy that was failing children without disabilities. What was holding them back and preventing them from reaching their potential? In 1907 she had the opportunity to start working with non-disabled children in a housing project located in a slum district of Rome. There, she set up her first 'Casa dei Bambini' ('children’s house') for 3–7-year olds. She continued to develop her distinctive pedagogy based on a scientific approach of experimentation and observation. On the basis of this work, she argued that children pass through sensitive periods for learning and several stages of development, and that children’s self-construction can be fostered through engaging with self-directed activities in a specially prepared environment. There was international interest in this new way of teaching, and there are now thousands of Montessori schools (predominantly for children aged 3–6 and 6–12) throughout the world. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4

Central to Montessori’s method of education is the dynamic triad of child, teacher and environment. One of the teacher’s roles is to guide the child through what Montessori termed the 'prepared environment, i.e., a classroom and a way of learning that are designed to support the child’s intellectual, physical, emotional and social development through active exploration, choice and independent learning. One way of making sense of the Montessori method for the purposes of this review is to consider two of its important aspects: the learning materials, and the way in which the teacher and the design of the prepared environment promote children’s self-directed engagement with those materials. With respect to the learning materials, Montessori developed a set of manipulable objects designed to support children’s learning of sensorial concepts such as dimension, colour, shape and texture, and academic concepts of mathematics, literacy, science, geography and history. With respect to engagement, children learn by engaging hands-on with the materials most often individually, but also in pairs or small groups, during a 3-h 'work cycle' in which they are guided by the teacher to choose their own activities. They are given the freedom to choose what they work on, where they work, with whom they work, and for how long they work on any particular activity, all within the limits of the class rules. No competition is set up between children, and there is no system of extrinsic rewards or punishments. These two aspects—the learning materials themselves, and the nature of the learning—make Montessori classrooms look strikingly different to conventional classrooms.

It should be noted that for Montessori the goal of education is to allow the child’s optimal development (intellectual, physical, emotional and social) to unfold. 2 This is a very different goal to that of most education systems today, where the focus is on attainment in academic subjects such as literacy and mathematics. Thus when we ask the question, as this review paper does, whether children benefit more from a Montessori education than from a non-Montessori education, we need to bear in mind that the outcome measures used to capture effectiveness do not necessarily measure the things that Montessori deemed most important in education. Teachers and parents who choose the Montessori method may choose it for reasons that are not so amenable to evaluation.

Despite its existence for over 100 years, peer-reviewed evaluations of Montessori education are few and they suffer from a number of methodological limitations, as will be discussed in Section 3. This review has three aims, namely to (1) identify some key elements of the Montessori educational method, (2) review existing evaluations of Montessori education, and (3) review studies that do not explicitly evaluate Montessori education but which evaluate the key elements identified in (1). My goal is to provide a review of the scientific evidence base for Montessori education, with the dual aspirations of stimulating future research and helping teachers to better understand whether and why Montessori education might be effective.

Some key elements of the Montessori educational method

The goal of this section is to isolate some key elements of the Montessori method, in order to better understand why, if Montessori education is effective, this might be, and what elements of it might usefully be evaluated by researchers. These are important considerations because there is considerable variability in how the Montessori method is implemented in different schools, and the name, which is not copyrighted, is frequently used without full adherence. 5 , 6 Nevertheless, some elements of the method might still be beneficial, or could be successfully incorporated (or, indeed, are already incorporated) into schools that do not want to carry the name 'Montessori' or to adhere fully to its principles. Pinpointing more precisely what—if anything—about the Montessori method is effective will enable a better understanding of why it works. Furthermore, it has been argued that there might be dangers in adopting wholesale and uncritically an educational method that originated over 100 years ago, in a world that was different in many ways to today’s. 7 If the method is to be adopted piecemeal, which pieces should be adopted? As outlined previously, two important aspects of Montessori’s educational method are the learning materials, and the self-directed nature of children’s engagement with those materials. Some key elements of each of these aspects will now be considered in turn.

The learning materials

The first learning materials that the child is likely to encounter in the Montessori classroom are those that make up the practical life curriculum. These are activities that involve pouring different materials, using utensils such as scissors, tongs and tweezers, cleaning and polishing, preparing snacks, laying the table and washing dishes, arranging flowers, gardening, doing up and undoing clothes fastenings, and so on. Their aims, in addition to developing the child’s skills for independent living, are to build up the child’s gross and fine motor control and eye-hand co-ordination, to introduce them to the cycle of selecting, initiating, completing and tidying up an activity (of which more in the next section), and to introduce the rules for functioning in the social setting of the classroom.

As the child settles into the cycle of work and shows the ability to focus on self-selected activities, the teacher will introduce the sensorial materials. The key feature of the sensorial materials is that each isolates just one concept for the child to focus on. The pink tower, for example, consists of ten cubes which differ only in their dimensions, the smallest being 1 cm 3 , the largest 10 cm 3 . In building the tower the child’s attention is being focused solely on the regular decrease in volume of successive cubes. There are no additional cues—different colours for example, or numbers written onto the faces of the cube—which might help the child to sequence the cubes accurately. Another piece of sensorial material, the sound boxes, contains six pairs of closed cylinders that vary in sound from soft to loud when shaken, and the task for the child is to find the matching pairs. Again, there is only one cue that the child can use to do this task: sound. The aim of the sensorial materials is not to bombard the child’s senses with stimuli; on the contrary, they are tools designed for enabling the child to classify and put names to the stimuli that he will encounter on an everyday basis.

The sensorial materials, are, furthermore, designed as preparation for academic subjects. The long rods, which comprise ten red rods varying solely in length in 10 cm increments from 10 cm to 1 m, have an equivalent in the mathematics materials: the number rods, where the rods are divided into alternating 10 cm sections of red and blue so that they take on the numerical values 1–10. The touchboards, which consist of alternate strips of sandpaper and smooth paper for the child to feel, are preparation for the sandpaper globe in geography—a globe where the land masses are made of rough sandpaper but the oceans and seas are smooth. The touchboards are also preparation for the sandpaper letters in literacy and sandpaper numerals in mathematics, which the child learns to trace with his index and middle fingers.

Key elements of the literacy curriculum include the introduction of writing before reading, the breaking down of the constituent skills of writing (pencil control, letter formation, spelling) before the child actually writes words on paper, and the use of phonics for teaching sound-letter correspondences. Grammar—parts of speech, morphology, sentence structure—are taught systematically through teacher and child-made materials.

In the mathematics curriculum, quantities 0–10 and their symbols are introduced separately before being combined, and large quantities and symbols (tens, hundreds and thousands) and fractions are introduced soon after, all through concrete materials. Operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, the calculation of square roots) are again introduced using concrete materials, which the child can choose to stop using when he is able to succeed without that concrete support.

Principles running throughout the design of these learning materials are that the child learns through movement and gains a concrete foundation with the aim of preparing him for learning more abstract concepts. A further design principle is that each piece of learning material has a 'control of error' which alerts the child to any mistakes, thereby allowing self-correction with minimal teacher support.

Self-directed engagement with the materials

Important though the learning materials are, 8 they do not, in isolation, constitute the Montessori method because they need to be engaged with in a particular way. Montessori observed that the young child is capable of concentrating for long periods of time on activities that capture his spontaneous interest. 2 , 3 , 4 There are two features of the way that children engage with the learning materials that Montessori claimed promoted this concentration. The first is that there is a cycle of activity surrounding the use of each piece of material (termed the 'internal work cycle ' 9 ). If a child wishes to use the pink tower, for example, he will have to find a space on the floor large enough to unroll the mat that will delineate his work area, carry the ten cubes of the pink tower individually to the mat from where they are stored, then build the tower. Once he has built the tower he is free to repeat this activity as many times as he likes. Other children may come and watch, and if he wishes they can join in with him, but he will be able to continue on his own if he prefers and for as long as he likes. When he has had enough, he will dismantle the pink tower and reassemble it in its original location, ready for another child to use. This repeated and self-chosen engagement with the material, the lack of interruption, and the requirement to set up the material and put it away afterwards, are key elements aimed at developing the child’s concentration. 10

The second feature which aims to promote concentration is that these cycles of activity take place during a 3-h period of time (termed the 'external work cycle' 9 ). During those 3 h children are mostly free to select activities on their own and with others, and to find their own rhythm of activity, moving freely around the classroom as they do so. One might wonder what the role of the teacher is during this period. Although the children have a great deal of freedom in what they do, their freedom is not unlimited. The teacher’s role is to guide children who are finding it hard to select materials or who are disturbing others, to introduce new materials to children who are ready for a new challenge, and to conduct small-group lessons. Her decisions about what to teach are made on the basis of careful observations of the children. Although she might start the day with plans of what she will do during the work cycle, she will be led by her students and their needs, and there is no formal timetable. Hence the Montessori classroom is very different to the teacher-led conventional classroom with its highly structured day where short timeslots are devoted to each activity, the whole class is engaged in the same activities at the same time, and the teacher instructs at the front of the class.

In summary, there are two aspects of Montessori classrooms that are very different to conventional classrooms: the learning materials themselves, and the individual, self-directed nature of the learning under the teacher’s expert guidance. All the elements described here—the features of the learning materials themselves (e.g., each piece of material isolates just one concept, each contains a control of error that allows for self-correction, learning proceeds from concrete to abstract concepts) and the child-led manner of engagement with those materials (e.g., self-selection, repeated and active engagement, tidying up afterwards, freedom from interruption, lack of grades and extrinsic rewards) might potentially benefit development and learning over the teaching of the conventional classroom. We will return to many of the elements discussed here in the following two sections. (This has necessarily been only a brief survey of some of the most important elements of the Montessori method. Readers wanting to find out more are again directed to refs. 2 , 3 , 4 ).

Evaluations of Montessori education

There are few peer-reviewed evaluations of Montessori education, and the majority have been carried out in the USA. Some have evaluated children’s outcomes while those children were in Montessori settings, and others have evaluated Montessori-educated children after a period of subsequent conventional schooling. As a whole this body of research suffers from several methodological limitations. Firstly, few studies are longitudinal in design. Secondly, there are no good quality randomised control trials; most researchers have instead tried to match participants in Montessori and comparison groups on as many likely confounding variables as possible. Thirdly, if children in the Montessori group do score higher than those in the non-Montessori group on a particular outcome measure, then assuming that that effect can be attributed to being in a Montessori classroom, what exactly is it about Montessori education that has caused the effect? Montessori education is a complex package—how can the specific elements which might be causing the effect be isolated? At a very basic level—and drawing on two of the main aspects of Montessori education outlined above—is the effect due to the learning materials or to the self-directed way in which children engage with them (and can the two be separated)? Fourthly, there are presumably differences between Montessori schools (including the way in which the method is implemented) that might influence children’s outcomes, but studies rarely include more than one Montessori school, and sometimes not more than one Montessori class. Fifthly, and relatedly, there is the issue of 'treatment fidelity'—what counts as a Montessori classroom? Not all schools that call themselves 'Montessori' adhere strictly to Montessori principles, have trained Montessori teachers, or are accredited by a professional organisation. A sixth, and again related, point is that children’s experiences in Montessori education will vary in terms of the length of time they spend in Montessori education, and the age at which they attend. Finally, the numbers of children participating in studies are usually small and quite narrow in terms of their demographics, making generalisation of any results problematic. These methodological issues are not limited to evaluations of Montessori education, of course—they are relevant to much of educational research.

Of these, the lack of randomised control trials is particularly notable given the recognition of their importance in education. 11 , 12 Parents choose their child’s school for a host of different reasons, 13 and randomisation is important in the context of Montessori education because parents who choose a non-conventional school for their child might be different in relevant ways from parents who do not, for example in their views on child-rearing and aspirations for their child’s future. This means that if a study finds a benefit for Montessori education over conventional education this might reflect a parent effect rather than a school effect. Furthermore, randomisation also controls for socio-economic status (SES). Montessori schools are often fee-paying, which means that pupils are likely to come from higher SES families; children from higher SES families are likely to do better in a variety of educational contexts. 14 , 15 , 16 A recent report found that even public (i.e., non-fee-paying) Montessori schools in the USA are not representative of the racial and socioeconomic diversity of the neighbourhoods they serve. 17 However, random assignment of children to Montessori versus non-Montessori schools for the purposes of a randomised control trial would be very difficult to achieve because it would take away parental choice.

Arguably the most robust evaluation of the Montessori method to date is that by Lillard and Else-Quest. 18 They compared children in Montessori and non-Montessori education and from two age groups—5 and 12-year olds—on a range of cognitive, academic, social and behavioural measures. Careful thought was given to how to overcome the lack of random assignment to the Montessori and non-Montessori groups. The authors’ solution was to design their study around the school lottery that was already in place in that particular school district. All children had entered the Montessori school lottery; those who were accepted were assigned to the Montessori group, and those who were not accepted were assigned to the comparison (other education systems) group. Post-hoc comparisons showed similar income levels in both sets of families. Although group differences were not found for all outcome measures, where they were found they favoured the Montessori group. For 5-year olds, significant group differences were found for certain academic skills (namely letter-word identification, phonological decoding ability, and math skills), a measure of executive function (the card sort task), social skills (as measured by social reasoning and positive shared play) and theory of mind (as measured by a false-belief task). For 12-year olds, significant group differences were found on measures of story writing and social skills. Furthermore, in a questionnaire that asked about how they felt about school, responses of children in the Montessori group indicated that they felt a greater sense of community. The authors concluded that 'at least when strictly implemented, Montessori education fosters social and academic skills that are equal or superior to those fostered by a pool of other types of schools'. 18

Their study has been criticised for using just one Montessori school, 19 but Lillard and Else-Quest’s response is that the school was faithful to Montessori principles, which suggests that the results might be generalisable to other such schools. 20 That fidelity might impact outcomes has long been of concern, 21 and was demonstrated empirically in a further, longitudinal, study, 6 that compared high fidelity Montessori classes (again, from just one school), 'supplemented' Montessori classes (which provided the Montessori materials plus conventional activities such as puzzles, games and worksheets), and conventional classrooms. Children in these classes were 3–6 years old, and they were tested at two time-points: towards the beginning and towards the end of the school year. Although the study lacked random assignment of children to groups, the groups were matched with respect to key parent variables such as parental education. As in Lillard and Else-Quest’s earlier study, 18 outcome measures tapped a range of social and academic skills related to school readiness (i.e., children’s preparedness to succeed in academic settings). There were two research questions: firstly, do preschool children’s school readiness skills change during the academic year as a function of school type, and secondly, within Montessori schools, does the percentage of children using Montessori materials in a classroom predict children’s school readiness skills at the end of the academic year? Overall, the answer to both questions was “yes”. Children in the high-fidelity Montessori school, as compared with children in the other two types of school, showed significantly greater gains on measures of executive function, reading, math, vocabulary, and social problem-solving. Furthermore, the degree to which children were engaged with Montessori materials significantly predicted gains in executive function, reading and vocabulary. In other words, treatment fidelity mattered: children gained fewer benefits from being in a Montessori school when they were engaged in non-Montessori activities.

This study does not demonstrate definitively that the Montessori materials drove the effect: there might have been other differences between the high and lower fidelity classrooms—such as the teachers’ interactions with their pupils—that were responsible for the difference in child outcomes. 6 In a move to explore the role of the Montessori materials further, a more recent experimental study 22 removed supplementary materials, to leave just the Montessori materials, from two of the three classrooms in a Montessori school that served 3–6-year olds. Over a period of 4 months children in the classrooms from which supplementary materials were removed made significantly greater gains than children from the unchanged classroom on tests of letter-word identification and executive function, although not on measures of vocabulary, theory of mind, maths, or social problem-solving. The authors acknowledge weaknesses in the study design, including the small number of participants (just 52 across the three classrooms) and the short duration. Nevertheless, the study does provide a template for how future experimental manipulations of fidelity to the Montessori method could be carried out.

Fidelity is important because variation in how faithful Montessori schools are to the 'ideal' is likely to be an important factor in explaining why such mixed findings have been found in evaluations of the Montessori method. 6 For example, two early randomised control trials to evaluate Head Start in the USA did not find any immediate benefit of Montessori preschool programmes over other types of preschool programmes. 23 , 24 In both programmes, only 4-year olds were included, whereas the ideal in Montessori preschool programmes is for 3–6 year olds to be taught in the same class in order to foster child-to-child tutoring. 6 Furthermore, in one of the programmes 23 the ideal 3-h work cycle was reduced to just 30 min. 6 A more recent study of older children compared 8th grade Montessori and non-Montessori students matched for gender, ethnicity and socio-economic status. 25 The study found lower scores for Montessori students for English/Language Arts and no difference for maths scores, but the participating Montessori school altered the “ideal” by issuing evaluative grades to pupils and introducing non-Montessori activities. 6

These same limitations then make it difficult to interpret studies that have found 'later' benefits for children who have been followed up after a subsequent period of conventional education. In one of the studies discussed earlier, 23 social and cognitive benefits did emerge for children who had previously attended Montessori preschools and then moved to conventional schools, but these benefits did not emerge until adolescence, while a follow-up study 26 found cognitive benefits in Montessori males only, again in adolescence. Although such 'sleeper effects' have been widely reported in evaluations of early years interventions, they may be artefacts of simple measurement error and random fluctuations. 27 Importantly, if the argument is that lack of fidelity to the Montessori method is responsible for studies not finding significant benefits of Montessori education at younger ages, it is not logical to then credit the Montessori method with any benefits that emerge in follow-up studies.

Some studies report positive outcomes for certain curricular areas but not others. One, for example, investigated scores on maths, science, English and social studies tests in the final years of compulsory education, several years after children had left their Montessori classrooms. 28 Compared to the non-Montessori group (who were matched for gender, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity and high school attended), the Montessori group scored significantly higher on maths and science, but no differences were found for English and social studies. What might explain this differential effect? The authors suggested that the advantages for maths might be driven by the materials themselves, compared to how maths is taught in conventional classes. 28 Alternatively, or perhaps in addition, children in Montessori classrooms might spend more time engaged in maths and science activities compared to children in conventional classes, with the amount of time spent on English and social studies not differing. However, the authors were unable, within the design of their study, to provide details of exactly how much time children in the Montessori school had spent doing maths, science, English and social studies, in comparison to the time that children in conventional classes were spending on those subjects.

Just as knowing what is going on in the Montessori classroom is vital to being able to interpret the findings of evaluations, so is knowing what is going on in the comparison classrooms. One of the earliest evaluations of Montessori education in the USA 29 speculated that Montessori would have found much to appreciate in one of the non-Montessori comparison classes, including its 'freedom for the children (moving about; working alone); its planned environment (innovative methods with tape recorder playback of children’s conversations; live animals, etc.); its non-punitive character (an “incorrect” answer deserves help, not anger; original answers are reinforced, but other answers are pursued); and its emphasis on concentration (the children sustained activity without direct supervision for relatively long periods of time)'. In some evaluations, the differences between Montessori and conventional classrooms might not actually be so great, which might explain why benefits of being educated in a Montessori classroom are not found. And even if the Montessori approach to teaching a particular curriculum area is different to those used in conventional classrooms, there are likely to be different, equally-effective approaches to teaching the same concepts. This is a suggested explanation for the finding that although children in Montessori kindergartens had an advantage relative to their conventionally-educated peers for base-10 understanding in mathematics, they did not maintain this advantage when tested 2 years later. 30

While most evaluations are interested in traditional academic outcomes or factors related to academic success such as executive functions, a small number have investigated creativity. For example, an old study 31 compared just 14 four and five-year-old children who attended a Montessori nursery school with 14 four and five-year olds who attended a conventional nursery school (matched for a range of parental variables, including attitudes and parental control). In a non-verbal creativity task, involving picture construction, they were given a blank sheet of paper, a piece of red gummed paper in the shape of a curved jellybean, and a pencil. They were then asked to think of and draw a picture in which the red paper would form an integral part. Each child’s construction was rated for originality, elaboration, activity, and title adequacy, and these ratings were then combined into a 'creativity' score. The group of conventionally-schooled children scored almost twice as high as the Montessori group. A second task involved the child giving verbal descriptions of seven objects: a red rubber ball, a green wooden cube, a short length of rope, a steel mirror, a piece of rectangular clear plastic, a piece of chalk, and a short length of plastic tubing. Each description was scored as to whether it was functional (i.e., focused on the object’s use) or whether it was a description of the object’s physical characteristics (i.e., shape, colour, etc.). Like the non-verbal creativity task, this task differentiated the two groups: whereas the conventionally educated children gave more functional descriptions (e.g., for the cube: “you play with it”), the Montessori children gave more physical descriptions (e.g., “it’s square, it’s made of wood, and it’s green”). A third task, the Embedded Figure Test, involved the child first being presented with a stimulus figure and then locating a similar figure located in an embedding context. Both accuracy and speed were measured. While the two groups did not differ in the number of embedded figures accurately located, the Montessori group completed the task significantly more quickly. The fourth and final task required children to draw a picture of anything they wanted to. Drawings were coded for the presence or absence of geometric figures and people. The Montessori group produced more geometric figures, but fewer people, than the conventional group.

The authors were careful not to cast judgement on the performance differences between the two groups. 31 They wrote that 'The study does, however, support the notion that differing preschool educational environments yield different outcomes' and 'Montessori children responded to the emphasis in their programme upon the physical world and upon a definition of school as a place of work; the Nursery School children responded on their part to the social emphasis and the opportunity for spontaneous expression of feeling'. They did not, however, compare and contrast the particular features of the two educational settings that might have given rise to these differences.

Creativity has been studied more recently in France. 32 Seven to twelve-year olds were tested longitudinally on five tasks tapping different aspects of creativity. 'Divergent' thinking tasks required children to (1) think of unusual uses for a cardboard box, (2) come up with ideas for making a plain toy elephant more entertaining, and (3) make as many drawings as possible starting from pairs of parallel lines. 'Integrative' thinking tasks required children to (1) invent a story based on a title that was provided to them, and (2) invent a drawing incorporating six particular shapes. Their sample was bigger than that of the previous study, 31 comprising 40 pupils from a Montessori school and 119 from two conventional schools, and pupils were tested in two consecutive years (no information is provided about whether pupils from different schools were matched on any variable other than age). For both types of task and at both time-points the Montessori-educated children scored higher than the conventionally-educated children. Again, the authors made little attempt to pinpoint the precise differences between schools that might have caused such differences in performance.

None of the studies discussed so far has attempted to isolate individual elements of the Montessori method that might be accounting for any of the positive effects that they find. There are several studies, however, that have focused on the practical life materials. A quasi-experimental study 33 demonstrated that the practical life materials can be efficacious in non-Montessori classrooms. More than 50 different practical life exercises were introduced into eight conventional kindergarten classes, while five conventional kindergarten classes were not given these materials and acted as a comparison group. The outcome measure was a fine motor control task, the 'penny posting test', whereby the number of pennies that a child could pick up and post through a one-inch slot in a can in two 30 s trials was counted. At pre-test the treatment and comparison groups did not differ in the number of pennies posted, but at post-test 6 months later the treatment group achieved a higher score than the comparison group, indicating finer motor control. A nice feature of this study is that teachers reported children in both groups spending the same amount of time on tasks designed to support fine motor control development, suggesting that there was something specific to the design of the practical life materials that was more effective in this regard than the conventional kindergarten materials on offer. And because the preschools that had used the practical life activities had introduced no other elements of the Montessori method, the effect could be confidently attributed to the practical life materials themselves.

An extension of this study 34 investigated the potential benefits of the practical life materials for fine motor control by comparing 5-year olds in Montessori kindergarten programmes with 5-year olds in a conventional programme (reported to have similarities in teaching mission and pupil background characteristics) on the 'flag posting test'. In this task, the child was given a solid hardwood tray covered with clay in which there were 12 pinholes. There were also 12 paper flags mounted on pins, six to the right of the tray and six to the left, and the child’s task was to place the flags one at time in the holes. The child received three scores: one for the amount of time taken to finish the activity, one for the number of attempts it took the child to put each flag into the hole, and one for hand dominance (to receive a score of 1 (established dominance) the child had to consistently use the same hand to place all 12 flags, whereas mixed dominance received a score of 0). Children were pre-tested at the beginning of the school year and post-tested 8 months later. Despite the lack of random assignment to groups, the two groups did not differ on pre-test scores, but they did at post-test: at post-test the Montessori group were significantly faster and significantly more accurate at the task, and had more established hand dominance. However, no attempt was made to measure how frequently children in both groups engaged with materials and activities that were designed to support fine motor control development. Furthermore, the children in the Montessori classrooms were at the age where they should also have been using the sensorial materials, some of which (for example, the 'knobbed cylinders' and 'geometric cabinet') are manipulated by holding small knobs, and whose use could potentially enhance fine motor control. At that age children would also have been using the 'insets for design', materials from the early literacy curriculum designed to enhance pencil control. Therefore, although the results of this study are consistent with the practical life materials enhancing fine motor control, the study does not securely establish that they do.

A further study 35 introduced practical life exercises into conventional kindergarten classes, while control kindergarten classes were not given these materials. 15 min were set aside in the experimental schools’ timetable for using the practical life materials, and they were also available during free choice periods. This time the outcome measure at pre-test and post-test was not fine motor skill but attention. There were benefits to attention of being in the experimental group, but only for girls—boys showed no such benefits. The differential gender impact of the practical life materials on the development of attention is puzzling. Girls did not appear to engage with the materials more than boys during the time that was set aside for using them, but no measure was taken of whether girls chose them more frequently than boys during the free choice periods. Similarly, there were no measurements of the time that children in both the experimental and control groups spent engaged in other activities that might have enhanced fine motor control. Nor is it clear whether it was the fine motor practice directly or rather the opportunity to select interesting activities (the teachers in the experimental schools commented on how interesting the children found the practical life activities) that was responsible for the benefits to attention that were recorded for girls.

Finally, it has been found that young adolescents in Montessori middle schools show greater intrinsic motivation than their peers in conventional middle schools (matched for an impressive array of background variables, including ethnicity, parental education and employment, home resources, parental involvement in school, and number of siblings). 36 The authors did not establish exactly which elements of the Montessori method might be responsible for this finding, but they did speculate that the following might be relevant: “students were provided at least 2 h per day to exercise choice and self-regulation; none of the students received mandatory grades; student grouping was primarily based on shared interests, not standardised tests; and students collaborated often with other students”. The authors did not evaluate the Montessori and non-Montessori groups on any measures of academic outcomes, but given the links between academic success and motivation at all stages of education (they provide a useful review of this literature), this link would be worth investigating in Montessori schools.

This section has discussed studies that have evaluated the Montessori method directly. To date there have been very few methodologically robust evaluations. Many suffer from limitations that make it challenging to interpret their findings, whether those findings are favourable, neutral or unfavourable towards the Montessori method. However, while randomised control trials could (and should) be designed to evaluate individual elements of the Montessori method, it is difficult to see how the random assignment of pupils to schools could work in practice (hence the ingenuity of the study reported in ref. 18 ). Nor could trials be appropriately blinded—teachers, and perhaps parents and pupils too, would know whether they were in the Montessori arm of the trial. In other words, although random assignment and blinding might work for specific interventions, it is hard to see how they could work for an entire school curriculum. Furthermore, given the complexity of identifying what it is that works, why it works, and for whom it works best, additional information, for example from observations of what children and teachers are actually doing in the classroom, would be needed for interpreting the results.

Evaluations of key elements of Montessori education that are shared with other educational methods

This final section examines studies that have not evaluated the Montessori method directly, but have evaluated other educational methods and interventions that share elements of the Montessori method. They, together with our growing understanding of the science underpinning learning, can add to the evidence base for Montessori education. Given the vast amount of research and the limited space in which to consider it, priority is given to systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

One of the best-researched instructional techniques is the use of phonics for teaching children to read. Phonics is the explicit teaching of the letter-sound correspondences that allow the child to crack the alphabetic code. Montessori’s first schools were in Italy, and Italian orthography has relatively transparent one-to-one mappings between letters and sounds, making phonics a logical choice of method for teaching children the mechanics of reading and spelling. English orthography is, however, much less regular: the mappings between letters and sounds are many-to-many, and for this reason the use of phonics as a method of instruction has been challenged for English. 37 Nevertheless, there is overwhelming evidence of its effectiveness despite English’s irregularities. 38 , 39 , 40 At the same time, great strides have been made in elucidating the neural mechanisms that underlie early reading and reading impairments, and these too demonstrate the importance to successful reading of integrating sound and visual representations. 41

As always in education, the devil is in the detail. Importantly, phonics programmes have the greatest impact on reading accuracy when they are systematic. 39 , 40 By 'systematic' it is meant that letter-sound relationships are taught in an organised sequence, rather than being taught on an ad hoc as-and-when-needed basis. However, within systematic teaching of phonics there are two very different approaches: synthetic phonics and analytic phonics. Synthetic phonics starts from the parts and works up to the whole: children learn the sounds that correspond to letters or groups of letters and use this knowledge to sound out words from left to right. Analytic phonics starts from the whole and drills down to the parts: sound-letter relationships are inferred from sets of words which share a letter and sound, e.g., \(\underline{h}\) at , \(\underline{h}\) en , \(\underline{h}\) ill , \(\underline{h}\) orse . Few randomised control trials have pitted synthetic and analytic phonics against one another, and it is not clear that either has the advantage. 40

The Montessori approach to teaching phonics is certainly systematic. Many schools in the UK, for example, use word lists drawn from Morris’s 'Phonics 44'. 42 , 43 Furthermore, the Montessori approach to phonics is synthetic rather than analytic: children are taught the sound-letter code before using it to encode words (in spelling) and decode them (in reading). One of the criticisms of synthetic phonics is that it teaches letters and sounds removed from their meaningful language context, in a way that analytic phonics does not. 44 It has long been recognised that the goal of reading is comprehension. Reading for meaning requires both code-based skills and language skills such as vocabulary, morphology, syntax and inferencing skills, 45 and these two sets of skills are not rigidly separated, but rather interact at multiple levels. 46 Indeed, phonics instruction works best where it is integrated with text-level reading instruction. 39 , 40 The explicit teaching of phonics within a rich language context—both spoken and written—is central to the Montessori curriculum. No evaluations have yet pitted phonics teaching in the Montessori classroom versus phonics teaching in the conventional classroom, however, and so whether the former is differentially effective is not known.

Research into writing supports Montessori’s view that writing involves a multitude of component skills, including handwriting, spelling, vocabulary and sentence construction. 47 , 48 Proficiency in these skills predicts the quality of children’s written compositions. 49 , 50 In the Montessori classroom these skills are worked on independently before being brought together, but they can continue to be practised independently. A growing body of research from conventional and special education classrooms demonstrates that the specific teaching of the component skills of writing improves the quality of children’s written compositions. 51 , 52 , 53 , 54

With respect to teaching mathematics to young children, there are many recommendations that Montessori teachers would recognise in their own classrooms, such as teaching geometry, number and operations using a developmental progression, and using progress monitoring to ensure that mathematics instruction builds on what each child knows. 55 Some of the recommended activities, such as 'help children to recognise, name, and compare shapes, and then teach them to combine and separate shapes' 55 map exactly on to Montessori’s sensorial materials such as the geometric cabinet and the constructive triangles. Other activities such as 'encourage children to label collections with number words and numerals' 55 map onto Montessori’s early mathematics material such as the number rods, the spindle box and the cards and counters. The importance of conceptual knowledge as the foundation for children being able to understand fractions has been stressed. 56 The Montessori fraction circles—which provide a sensorial experience with the fractions from one whole to ten tenths—provide just such a foundation, as do practical life exercises such as preparing snacks (how should a banana be cut so that it can be shared between three children?) and folding napkins.