How to Write a Research Paper: Parts of the Paper

- Choosing Your Topic

- Citation & Style Guides This link opens in a new window

- Critical Thinking

- Evaluating Information

- Parts of the Paper

- Writing Tips from UNC-Chapel Hill

- Librarian Contact

Parts of the Research Paper Papers should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Your introductory paragraph should grab the reader's attention, state your main idea, and indicate how you will support it. The body of the paper should expand on what you have stated in the introduction. Finally, the conclusion restates the paper's thesis and should explain what you have learned, giving a wrap up of your main ideas.

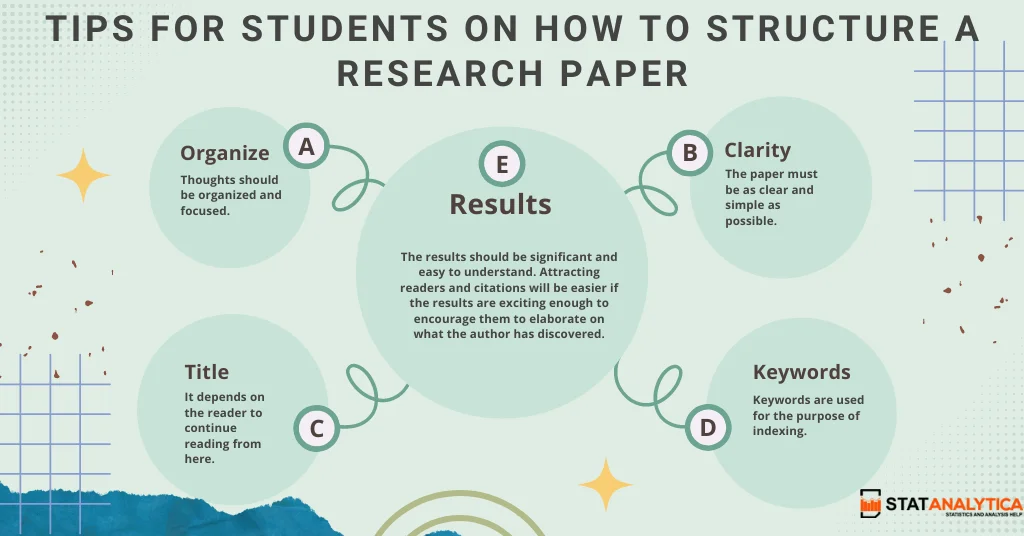

1. The Title The title should be specific and indicate the theme of the research and what ideas it addresses. Use keywords that help explain your paper's topic to the reader. Try to avoid abbreviations and jargon. Think about keywords that people would use to search for your paper and include them in your title.

2. The Abstract The abstract is used by readers to get a quick overview of your paper. Typically, they are about 200 words in length (120 words minimum to 250 words maximum). The abstract should introduce the topic and thesis, and should provide a general statement about what you have found in your research. The abstract allows you to mention each major aspect of your topic and helps readers decide whether they want to read the rest of the paper. Because it is a summary of the entire research paper, it is often written last.

3. The Introduction The introduction should be designed to attract the reader's attention and explain the focus of the research. You will introduce your overview of the topic, your main points of information, and why this subject is important. You can introduce the current understanding and background information about the topic. Toward the end of the introduction, you add your thesis statement, and explain how you will provide information to support your research questions. This provides the purpose and focus for the rest of the paper.

4. Thesis Statement Most papers will have a thesis statement or main idea and supporting facts/ideas/arguments. State your main idea (something of interest or something to be proven or argued for or against) as your thesis statement, and then provide your supporting facts and arguments. A thesis statement is a declarative sentence that asserts the position a paper will be taking. It also points toward the paper's development. This statement should be both specific and arguable. Generally, the thesis statement will be placed at the end of the first paragraph of your paper. The remainder of your paper will support this thesis.

Students often learn to write a thesis as a first step in the writing process, but often, after research, a writer's viewpoint may change. Therefore a thesis statement may be one of the final steps in writing.

Examples of Thesis Statements from Purdue OWL

5. The Literature Review The purpose of the literature review is to describe past important research and how it specifically relates to the research thesis. It should be a synthesis of the previous literature and the new idea being researched. The review should examine the major theories related to the topic to date and their contributors. It should include all relevant findings from credible sources, such as academic books and peer-reviewed journal articles. You will want to:

- Explain how the literature helps the researcher understand the topic.

- Try to show connections and any disparities between the literature.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

More about writing a literature review. . .

6. The Discussion The purpose of the discussion is to interpret and describe what you have learned from your research. Make the reader understand why your topic is important. The discussion should always demonstrate what you have learned from your readings (and viewings) and how that learning has made the topic evolve, especially from the short description of main points in the introduction.Explain any new understanding or insights you have had after reading your articles and/or books. Paragraphs should use transitioning sentences to develop how one paragraph idea leads to the next. The discussion will always connect to the introduction, your thesis statement, and the literature you reviewed, but it does not simply repeat or rearrange the introduction. You want to:

- Demonstrate critical thinking, not just reporting back facts that you gathered.

- If possible, tell how the topic has evolved over the past and give it's implications for the future.

- Fully explain your main ideas with supporting information.

- Explain why your thesis is correct giving arguments to counter points.

7. The Conclusion A concluding paragraph is a brief summary of your main ideas and restates the paper's main thesis, giving the reader the sense that the stated goal of the paper has been accomplished. What have you learned by doing this research that you didn't know before? What conclusions have you drawn? You may also want to suggest further areas of study, improvement of research possibilities, etc. to demonstrate your critical thinking regarding your research.

- << Previous: Evaluating Information

- Next: Research >>

- Last Updated: Feb 13, 2024 8:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ucc.edu/research_paper

- Search This Site All UCSD Sites Faculty/Staff Search Term

- Contact & Directions

- Climate Statement

- Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Adjunct Faculty

- Non-Senate Instructors

- Researchers

- Psychology Grads

- Affiliated Grads

- New and Prospective Students

- Honors Program

- Experiential Learning

- Programs & Events

- Psi Chi / Psychology Club

- Prospective PhD Students

- Current PhD Students

- Area Brown Bags

- Colloquium Series

- Anderson Distinguished Lecture Series

- Speaker Videos

- Undergraduate Program

- Academic and Writing Resources

Writing Research Papers

- Research Paper Structure

Whether you are writing a B.S. Degree Research Paper or completing a research report for a Psychology course, it is highly likely that you will need to organize your research paper in accordance with American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines. Here we discuss the structure of research papers according to APA style.

Major Sections of a Research Paper in APA Style

A complete research paper in APA style that is reporting on experimental research will typically contain a Title page, Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion, and References sections. 1 Many will also contain Figures and Tables and some will have an Appendix or Appendices. These sections are detailed as follows (for a more in-depth guide, please refer to " How to Write a Research Paper in APA Style ”, a comprehensive guide developed by Prof. Emma Geller). 2

What is this paper called and who wrote it? – the first page of the paper; this includes the name of the paper, a “running head”, authors, and institutional affiliation of the authors. The institutional affiliation is usually listed in an Author Note that is placed towards the bottom of the title page. In some cases, the Author Note also contains an acknowledgment of any funding support and of any individuals that assisted with the research project.

One-paragraph summary of the entire study – typically no more than 250 words in length (and in many cases it is well shorter than that), the Abstract provides an overview of the study.

Introduction

What is the topic and why is it worth studying? – the first major section of text in the paper, the Introduction commonly describes the topic under investigation, summarizes or discusses relevant prior research (for related details, please see the Writing Literature Reviews section of this website), identifies unresolved issues that the current research will address, and provides an overview of the research that is to be described in greater detail in the sections to follow.

What did you do? – a section which details how the research was performed. It typically features a description of the participants/subjects that were involved, the study design, the materials that were used, and the study procedure. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Methods section. A rule of thumb is that the Methods section should be sufficiently detailed for another researcher to duplicate your research.

What did you find? – a section which describes the data that was collected and the results of any statistical tests that were performed. It may also be prefaced by a description of the analysis procedure that was used. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Results section.

What is the significance of your results? – the final major section of text in the paper. The Discussion commonly features a summary of the results that were obtained in the study, describes how those results address the topic under investigation and/or the issues that the research was designed to address, and may expand upon the implications of those findings. Limitations and directions for future research are also commonly addressed.

List of articles and any books cited – an alphabetized list of the sources that are cited in the paper (by last name of the first author of each source). Each reference should follow specific APA guidelines regarding author names, dates, article titles, journal titles, journal volume numbers, page numbers, book publishers, publisher locations, websites, and so on (for more information, please see the Citing References in APA Style page of this website).

Tables and Figures

Graphs and data (optional in some cases) – depending on the type of research being performed, there may be Tables and/or Figures (however, in some cases, there may be neither). In APA style, each Table and each Figure is placed on a separate page and all Tables and Figures are included after the References. Tables are included first, followed by Figures. However, for some journals and undergraduate research papers (such as the B.S. Research Paper or Honors Thesis), Tables and Figures may be embedded in the text (depending on the instructor’s or editor’s policies; for more details, see "Deviations from APA Style" below).

Supplementary information (optional) – in some cases, additional information that is not critical to understanding the research paper, such as a list of experiment stimuli, details of a secondary analysis, or programming code, is provided. This is often placed in an Appendix.

Variations of Research Papers in APA Style

Although the major sections described above are common to most research papers written in APA style, there are variations on that pattern. These variations include:

- Literature reviews – when a paper is reviewing prior published research and not presenting new empirical research itself (such as in a review article, and particularly a qualitative review), then the authors may forgo any Methods and Results sections. Instead, there is a different structure such as an Introduction section followed by sections for each of the different aspects of the body of research being reviewed, and then perhaps a Discussion section.

- Multi-experiment papers – when there are multiple experiments, it is common to follow the Introduction with an Experiment 1 section, itself containing Methods, Results, and Discussion subsections. Then there is an Experiment 2 section with a similar structure, an Experiment 3 section with a similar structure, and so on until all experiments are covered. Towards the end of the paper there is a General Discussion section followed by References. Additionally, in multi-experiment papers, it is common for the Results and Discussion subsections for individual experiments to be combined into single “Results and Discussion” sections.

Departures from APA Style

In some cases, official APA style might not be followed (however, be sure to check with your editor, instructor, or other sources before deviating from standards of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association). Such deviations may include:

- Placement of Tables and Figures – in some cases, to make reading through the paper easier, Tables and/or Figures are embedded in the text (for example, having a bar graph placed in the relevant Results section). The embedding of Tables and/or Figures in the text is one of the most common deviations from APA style (and is commonly allowed in B.S. Degree Research Papers and Honors Theses; however you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first).

- Incomplete research – sometimes a B.S. Degree Research Paper in this department is written about research that is currently being planned or is in progress. In those circumstances, sometimes only an Introduction and Methods section, followed by References, is included (that is, in cases where the research itself has not formally begun). In other cases, preliminary results are presented and noted as such in the Results section (such as in cases where the study is underway but not complete), and the Discussion section includes caveats about the in-progress nature of the research. Again, you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first.

- Class assignments – in some classes in this department, an assignment must be written in APA style but is not exactly a traditional research paper (for instance, a student asked to write about an article that they read, and to write that report in APA style). In that case, the structure of the paper might approximate the typical sections of a research paper in APA style, but not entirely. You should check with your instructor for further guidelines.

Workshops and Downloadable Resources

- For in-person discussion of the process of writing research papers, please consider attending this department’s “Writing Research Papers” workshop (for dates and times, please check the undergraduate workshops calendar).

Downloadable Resources

- How to Write APA Style Research Papers (a comprehensive guide) [ PDF ]

- Tips for Writing APA Style Research Papers (a brief summary) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – empirical research) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – literature review) [ PDF ]

Further Resources

How-To Videos

- Writing Research Paper Videos

APA Journal Article Reporting Guidelines

- Appelbaum, M., Cooper, H., Kline, R. B., Mayo-Wilson, E., Nezu, A. M., & Rao, S. M. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 3.

- Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 26.

External Resources

- Formatting APA Style Papers in Microsoft Word

- How to Write an APA Style Research Paper from Hamilton University

- WikiHow Guide to Writing APA Research Papers

- Sample APA Formatted Paper with Comments

- Sample APA Formatted Paper

- Tips for Writing a Paper in APA Style

1 VandenBos, G. R. (Ed). (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.) (pp. 41-60). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

2 geller, e. (2018). how to write an apa-style research report . [instructional materials]. , prepared by s. c. pan for ucsd psychology.

Back to top

- Formatting Research Papers

- Using Databases and Finding References

- What Types of References Are Appropriate?

- Evaluating References and Taking Notes

- Citing References

- Writing a Literature Review

- Writing Process and Revising

- Improving Scientific Writing

- Academic Integrity and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Writing Research Papers Videos

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.

It is typically based on Empirical Evidence, and may involve qualitative or quantitative research methods, or a combination of both. The purpose of a research paper is to contribute new knowledge or insights to a particular field of study, and to demonstrate the author’s understanding of the existing literature and theories related to the topic.

Structure of Research Paper

The structure of a research paper typically follows a standard format, consisting of several sections that convey specific information about the research study. The following is a detailed explanation of the structure of a research paper:

The title page contains the title of the paper, the name(s) of the author(s), and the affiliation(s) of the author(s). It also includes the date of submission and possibly, the name of the journal or conference where the paper is to be published.

The abstract is a brief summary of the research paper, typically ranging from 100 to 250 words. It should include the research question, the methods used, the key findings, and the implications of the results. The abstract should be written in a concise and clear manner to allow readers to quickly grasp the essence of the research.

Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper provides background information about the research problem, the research question, and the research objectives. It also outlines the significance of the research, the research gap that it aims to fill, and the approach taken to address the research question. Finally, the introduction section ends with a clear statement of the research hypothesis or research question.

Literature Review

The literature review section of a research paper provides an overview of the existing literature on the topic of study. It includes a critical analysis and synthesis of the literature, highlighting the key concepts, themes, and debates. The literature review should also demonstrate the research gap and how the current study seeks to address it.

The methods section of a research paper describes the research design, the sample selection, the data collection and analysis procedures, and the statistical methods used to analyze the data. This section should provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the research, using tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. The findings should be presented in a clear and concise manner, with reference to the research question and hypothesis.

The discussion section of a research paper interprets the findings and discusses their implications for the research question, the literature review, and the field of study. It should also address the limitations of the study and suggest future research directions.

The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study, restates the research question and hypothesis, and provides a final reflection on the significance of the research.

The references section provides a list of all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style such as APA, MLA or Chicago.

How to Write Research Paper

You can write Research Paper by the following guide:

- Choose a Topic: The first step is to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. Brainstorm ideas and narrow down to a research question that is specific and researchable.

- Conduct a Literature Review: The literature review helps you identify the gap in the existing research and provides a basis for your research question. It also helps you to develop a theoretical framework and research hypothesis.

- Develop a Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the main argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise and specific to your research question.

- Plan your Research: Develop a research plan that outlines the methods, data sources, and data analysis procedures. This will help you to collect and analyze data effectively.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Collect data using various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. Analyze data using statistical tools or other qualitative methods.

- Organize your Paper : Organize your paper into sections such as Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Ensure that each section is coherent and follows a logical flow.

- Write your Paper : Start by writing the introduction, followed by the literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and follows the required formatting and citation styles.

- Edit and Proofread your Paper: Review your paper for grammar and spelling errors, and ensure that it is well-structured and easy to read. Ask someone else to review your paper to get feedback and suggestions for improvement.

- Cite your Sources: Ensure that you properly cite all sources used in your research paper. This is essential for giving credit to the original authors and avoiding plagiarism.

Research Paper Example

Note : The below example research paper is for illustrative purposes only and is not an actual research paper. Actual research papers may have different structures, contents, and formats depending on the field of study, research question, data collection and analysis methods, and other factors. Students should always consult with their professors or supervisors for specific guidelines and expectations for their research papers.

Research Paper Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health among Young Adults

Abstract: This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults. A literature review was conducted to examine the existing research on the topic. A survey was then administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Introduction: Social media has become an integral part of modern life, particularly among young adults. While social media has many benefits, including increased communication and social connectivity, it has also been associated with negative outcomes, such as addiction, cyberbullying, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults.

Literature Review: The literature review highlights the existing research on the impact of social media use on mental health. The review shows that social media use is associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health problems. The review also identifies the factors that contribute to the negative impact of social media, including social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Methods : A survey was administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The survey included questions on social media use, mental health status (measured using the DASS-21), and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression analysis.

Results : The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Discussion : The study’s findings suggest that social media use has a negative impact on the mental health of young adults. The study highlights the need for interventions that address the factors contributing to the negative impact of social media, such as social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Conclusion : In conclusion, social media use has a significant impact on the mental health of young adults. The study’s findings underscore the need for interventions that promote healthy social media use and address the negative outcomes associated with social media use. Future research can explore the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health. Additionally, longitudinal studies can investigate the long-term effects of social media use on mental health.

Limitations : The study has some limitations, including the use of self-report measures and a cross-sectional design. The use of self-report measures may result in biased responses, and a cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality.

Implications: The study’s findings have implications for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers. Mental health professionals can use the findings to develop interventions that address the negative impact of social media use on mental health. Educators can incorporate social media literacy into their curriculum to promote healthy social media use among young adults. Policymakers can use the findings to develop policies that protect young adults from the negative outcomes associated with social media use.

References :

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive medicine reports, 15, 100918.

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., … & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among US young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1-9.

- Van der Meer, T. G., & Verhoeven, J. W. (2017). Social media and its impact on academic performance of students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16, 383-398.

Appendix : The survey used in this study is provided below.

Social Media and Mental Health Survey

- How often do you use social media per day?

- Less than 30 minutes

- 30 minutes to 1 hour

- 1 to 2 hours

- 2 to 4 hours

- More than 4 hours

- Which social media platforms do you use?

- Others (Please specify)

- How often do you experience the following on social media?

- Social comparison (comparing yourself to others)

- Cyberbullying

- Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

- Have you ever experienced any of the following mental health problems in the past month?

- Do you think social media use has a positive or negative impact on your mental health?

- Very positive

- Somewhat positive

- Somewhat negative

- Very negative

- In your opinion, which factors contribute to the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Social comparison

- In your opinion, what interventions could be effective in reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Education on healthy social media use

- Counseling for mental health problems caused by social media

- Social media detox programs

- Regulation of social media use

Thank you for your participation!

Applications of Research Paper

Research papers have several applications in various fields, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge by generating new insights, theories, and findings that can inform future research and practice. They help to answer important questions, clarify existing knowledge, and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Informing policy: Research papers can inform policy decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations for policymakers. They can help to identify gaps in current policies, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and inform the development of new policies and regulations.

- Improving practice: Research papers can improve practice by providing evidence-based guidance for professionals in various fields, including medicine, education, business, and psychology. They can inform the development of best practices, guidelines, and standards of care that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- Educating students : Research papers are often used as teaching tools in universities and colleges to educate students about research methods, data analysis, and academic writing. They help students to develop critical thinking skills, research skills, and communication skills that are essential for success in many careers.

- Fostering collaboration: Research papers can foster collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by providing a platform for sharing knowledge and ideas. They can facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships that can lead to innovative solutions to complex problems.

When to Write Research Paper

Research papers are typically written when a person has completed a research project or when they have conducted a study and have obtained data or findings that they want to share with the academic or professional community. Research papers are usually written in academic settings, such as universities, but they can also be written in professional settings, such as research organizations, government agencies, or private companies.

Here are some common situations where a person might need to write a research paper:

- For academic purposes: Students in universities and colleges are often required to write research papers as part of their coursework, particularly in the social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities. Writing research papers helps students to develop research skills, critical thinking skills, and academic writing skills.

- For publication: Researchers often write research papers to publish their findings in academic journals or to present their work at academic conferences. Publishing research papers is an important way to disseminate research findings to the academic community and to establish oneself as an expert in a particular field.

- To inform policy or practice : Researchers may write research papers to inform policy decisions or to improve practice in various fields. Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies, guidelines, and best practices that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- To share new insights or ideas: Researchers may write research papers to share new insights or ideas with the academic or professional community. They may present new theories, propose new research methods, or challenge existing paradigms in their field.

Purpose of Research Paper

The purpose of a research paper is to present the results of a study or investigation in a clear, concise, and structured manner. Research papers are written to communicate new knowledge, ideas, or findings to a specific audience, such as researchers, scholars, practitioners, or policymakers. The primary purposes of a research paper are:

- To contribute to the body of knowledge : Research papers aim to add new knowledge or insights to a particular field or discipline. They do this by reporting the results of empirical studies, reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, proposing new theories, or providing new perspectives on a topic.

- To inform or persuade: Research papers are written to inform or persuade the reader about a particular issue, topic, or phenomenon. They present evidence and arguments to support their claims and seek to persuade the reader of the validity of their findings or recommendations.

- To advance the field: Research papers seek to advance the field or discipline by identifying gaps in knowledge, proposing new research questions or approaches, or challenging existing assumptions or paradigms. They aim to contribute to ongoing debates and discussions within a field and to stimulate further research and inquiry.

- To demonstrate research skills: Research papers demonstrate the author’s research skills, including their ability to design and conduct a study, collect and analyze data, and interpret and communicate findings. They also demonstrate the author’s ability to critically evaluate existing literature, synthesize information from multiple sources, and write in a clear and structured manner.

Characteristics of Research Paper

Research papers have several characteristics that distinguish them from other forms of academic or professional writing. Here are some common characteristics of research papers:

- Evidence-based: Research papers are based on empirical evidence, which is collected through rigorous research methods such as experiments, surveys, observations, or interviews. They rely on objective data and facts to support their claims and conclusions.

- Structured and organized: Research papers have a clear and logical structure, with sections such as introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. They are organized in a way that helps the reader to follow the argument and understand the findings.

- Formal and objective: Research papers are written in a formal and objective tone, with an emphasis on clarity, precision, and accuracy. They avoid subjective language or personal opinions and instead rely on objective data and analysis to support their arguments.

- Citations and references: Research papers include citations and references to acknowledge the sources of information and ideas used in the paper. They use a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, or Chicago, to ensure consistency and accuracy.

- Peer-reviewed: Research papers are often peer-reviewed, which means they are evaluated by other experts in the field before they are published. Peer-review ensures that the research is of high quality, meets ethical standards, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Objective and unbiased: Research papers strive to be objective and unbiased in their presentation of the findings. They avoid personal biases or preconceptions and instead rely on the data and analysis to draw conclusions.

Advantages of Research Paper

Research papers have many advantages, both for the individual researcher and for the broader academic and professional community. Here are some advantages of research papers:

- Contribution to knowledge: Research papers contribute to the body of knowledge in a particular field or discipline. They add new information, insights, and perspectives to existing literature and help advance the understanding of a particular phenomenon or issue.

- Opportunity for intellectual growth: Research papers provide an opportunity for intellectual growth for the researcher. They require critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity, which can help develop the researcher’s skills and knowledge.

- Career advancement: Research papers can help advance the researcher’s career by demonstrating their expertise and contributions to the field. They can also lead to new research opportunities, collaborations, and funding.

- Academic recognition: Research papers can lead to academic recognition in the form of awards, grants, or invitations to speak at conferences or events. They can also contribute to the researcher’s reputation and standing in the field.

- Impact on policy and practice: Research papers can have a significant impact on policy and practice. They can inform policy decisions, guide practice, and lead to changes in laws, regulations, or procedures.

- Advancement of society: Research papers can contribute to the advancement of society by addressing important issues, identifying solutions to problems, and promoting social justice and equality.

Limitations of Research Paper

Research papers also have some limitations that should be considered when interpreting their findings or implications. Here are some common limitations of research papers:

- Limited generalizability: Research findings may not be generalizable to other populations, settings, or contexts. Studies often use specific samples or conditions that may not reflect the broader population or real-world situations.

- Potential for bias : Research papers may be biased due to factors such as sample selection, measurement errors, or researcher biases. It is important to evaluate the quality of the research design and methods used to ensure that the findings are valid and reliable.

- Ethical concerns: Research papers may raise ethical concerns, such as the use of vulnerable populations or invasive procedures. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants to ensure that the research is conducted in a responsible and respectful manner.

- Limitations of methodology: Research papers may be limited by the methodology used to collect and analyze data. For example, certain research methods may not capture the complexity or nuance of a particular phenomenon, or may not be appropriate for certain research questions.

- Publication bias: Research papers may be subject to publication bias, where positive or significant findings are more likely to be published than negative or non-significant findings. This can skew the overall findings of a particular area of research.

- Time and resource constraints: Research papers may be limited by time and resource constraints, which can affect the quality and scope of the research. Researchers may not have access to certain data or resources, or may be unable to conduct long-term studies due to practical limitations.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Scientific and Scholarly Writing

- Literature Searches

- Tracking and Citing References

Parts of a Scientific & Scholarly Paper

Introduction.

- Writing Effectively

- Where to Publish?

- Capstone Resources

Different sections are needed in different types of scientific papers (lab reports, literature reviews, systematic reviews, methods papers, research papers, etc.). Projects that overlap with the social sciences or humanities may have different requirements. Generally, however, you'll need to include:

INTRODUCTION (Background)

METHODS SECTION (Materials and Methods)

What is a title

Titles have two functions: to identify the main topic or the message of the paper and to attract readers.

The title will be read by many people. Only a few will read the entire paper, therefore all words in the title should be chosen with care. Too short a title is not helpful to the potential reader. Too long a title can sometimes be even less meaningful. Remember a title is not an abstract. Neither is a title a sentence.

What makes a good title?

A good title is accurate, complete, and specific. Imagine searching for your paper in PubMed. What words would you use?

- Use the fewest possible words that describe the contents of the paper.

- Avoid waste words like "Studies on", or "Investigations on".

- Use specific terms rather than general.

- Use the same key terms in the title as the paper.

- Watch your word order and syntax.

The abstract is a miniature version of your paper. It should present the main story and a few essential details of the paper for readers who only look at the abstract and should serve as a clear preview for readers who read your whole paper. They are usually short (250 words or less).

The goal is to communicate:

- What was done?

- Why was it done?

- How was it done?

- What was found?

A good abstract is specific and selective. Try summarizing each of the sections of your paper in a sentence two. Do the abstract last, so you know exactly what you want to write.

- Use 1 or more well developed paragraphs.

- Use introduction/body/conclusion structure.

- Present purpose, results, conclusions and recommendations in that order.

- Make it understandable to a wide audience.

- << Previous: Tracking and Citing References

- Next: Writing Effectively >>

- Last Updated: Apr 17, 2024 3:27 PM

- URL: https://libraryguides.umassmed.edu/scientific-writing

Structure of a Research Paper

Structure of a Research Paper: IMRaD Format

I. The Title Page

- Title: Tells the reader what to expect in the paper.

- Author(s): Most papers are written by one or two primary authors. The remaining authors have reviewed the work and/or aided in study design or data analysis (International Committee of Medical Editors, 1997). Check the Instructions to Authors for the target journal for specifics about authorship.

- Keywords [according to the journal]

- Corresponding Author: Full name and affiliation for the primary contact author for persons who have questions about the research.

- Financial & Equipment Support [if needed]: Specific information about organizations, agencies, or companies that supported the research.

- Conflicts of Interest [if needed]: List and explain any conflicts of interest.

II. Abstract: “Structured abstract” has become the standard for research papers (introduction, objective, methods, results and conclusions), while reviews, case reports and other articles have non-structured abstracts. The abstract should be a summary/synopsis of the paper.

III. Introduction: The “why did you do the study”; setting the scene or laying the foundation or background for the paper.

IV. Methods: The “how did you do the study.” Describe the --

- Context and setting of the study

- Specify the study design

- Population (patients, etc. if applicable)

- Sampling strategy

- Intervention (if applicable)

- Identify the main study variables

- Data collection instruments and procedures

- Outline analysis methods

V. Results: The “what did you find” --

- Report on data collection and/or recruitment

- Participants (demographic, clinical condition, etc.)

- Present key findings with respect to the central research question

- Secondary findings (secondary outcomes, subgroup analyses, etc.)

VI. Discussion: Place for interpreting the results

- Main findings of the study

- Discuss the main results with reference to previous research

- Policy and practice implications of the results

- Strengths and limitations of the study

VII. Conclusions: [occasionally optional or not required]. Do not reiterate the data or discussion. Can state hunches, inferences or speculations. Offer perspectives for future work.

VIII. Acknowledgements: Names people who contributed to the work, but did not contribute sufficiently to earn authorship. You must have permission from any individuals mentioned in the acknowledgements sections.

IX. References: Complete citations for any articles or other materials referenced in the text of the article.

- IMRD Cheatsheet (Carnegie Mellon) pdf.

- Adewasi, D. (2021 June 14). What Is IMRaD? IMRaD Format in Simple Terms! . Scientific-editing.info.

- Nair, P.K.R., Nair, V.D. (2014). Organization of a Research Paper: The IMRAD Format. In: Scientific Writing and Communication in Agriculture and Natural Resources. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-03101-9_2

- Sollaci, L. B., & Pereira, M. G. (2004). The introduction, methods, results, and discussion (IMRAD) structure: a fifty-year survey. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA , 92 (3), 364–367.

- Cuschieri, S., Grech, V., & Savona-Ventura, C. (2019). WASP (Write a Scientific Paper): Structuring a scientific paper. Early human development , 128 , 114–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2018.09.011

- Research guides

Writing an Educational Research Paper

Research paper sections, customary parts of an education research paper.

There is no one right style or manner for writing an education paper. Content aside, the writing style and presentation of papers in different educational fields vary greatly. Nevertheless, certain parts are common to most papers, for example:

Title/Cover Page

Contains the paper's title, the author's name, address, phone number, e-mail, and the day's date.

Not every education paper requires an abstract. However, for longer, more complex papers abstracts are particularly useful. Often only 100 to 300 words, the abstract generally provides a broad overview and is never more than a page. It describes the essence, the main theme of the paper. It includes the research question posed, its significance, the methodology, and the main results or findings. Footnotes or cited works are never listed in an abstract. Remember to take great care in composing the abstract. It's the first part of the paper the instructor reads. It must impress with a strong content, good style, and general aesthetic appeal. Never write it hastily or carelessly.

Introduction and Statement of the Problem

A good introduction states the main research problem and thesis argument. What precisely are you studying and why is it important? How original is it? Will it fill a gap in other studies? Never provide a lengthy justification for your topic before it has been explicitly stated.

Limitations of Study

Indicate as soon as possible what you intend to do, and what you are not going to attempt. You may limit the scope of your paper by any number of factors, for example, time, personnel, gender, age, geographic location, nationality, and so on.

Methodology

Discuss your research methodology. Did you employ qualitative or quantitative research methods? Did you administer a questionnaire or interview people? Any field research conducted? How did you collect data? Did you utilize other libraries or archives? And so on.

Literature Review

The research process uncovers what other writers have written about your topic. Your education paper should include a discussion or review of what is known about the subject and how that knowledge was acquired. Once you provide the general and specific context of the existing knowledge, then you yourself can build on others' research. The guide Writing a Literature Review will be helpful here.

Main Body of Paper/Argument

This is generally the longest part of the paper. It's where the author supports the thesis and builds the argument. It contains most of the citations and analysis. This section should focus on a rational development of the thesis with clear reasoning and solid argumentation at all points. A clear focus, avoiding meaningless digressions, provides the essential unity that characterizes a strong education paper.

After spending a great deal of time and energy introducing and arguing the points in the main body of the paper, the conclusion brings everything together and underscores what it all means. A stimulating and informative conclusion leaves the reader informed and well-satisfied. A conclusion that makes sense, when read independently from the rest of the paper, will win praise.

Works Cited/Bibliography

See the Citation guide .

Education research papers often contain one or more appendices. An appendix contains material that is appropriate for enlarging the reader's understanding, but that does not fit very well into the main body of the paper. Such material might include tables, charts, summaries, questionnaires, interview questions, lengthy statistics, maps, pictures, photographs, lists of terms, glossaries, survey instruments, letters, copies of historical documents, and many other types of supplementary material. A paper may have several appendices. They are usually placed after the main body of the paper but before the bibliography or works cited section. They are usually designated by such headings as Appendix A, Appendix B, and so on.

- << Previous: Choosing a Topic

- Next: Find Books >>

- Last Updated: Dec 5, 2023 2:26 PM

- Subjects: Education

- Tags: education , education_paper , education_research_paper

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Online Guide to Writing and Research

The research process, explore more of umgc.

- Online Guide to Writing

Structuring the Research Paper

Formal research structure.

These are the primary purposes for formal research:

enter the discourse, or conversation, of other writers and scholars in your field

learn how others in your field use primary and secondary resources

find and understand raw data and information

For the formal academic research assignment, consider an organizational pattern typically used for primary academic research. The pattern includes the following: introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusions/recommendations.

Usually, research papers flow from the general to the specific and back to the general in their organization. The introduction uses a general-to-specific movement in its organization, establishing the thesis and setting the context for the conversation. The methods and results sections are more detailed and specific, providing support for the generalizations made in the introduction. The discussion section moves toward an increasingly more general discussion of the subject, leading to the conclusions and recommendations, which then generalize the conversation again.

Sections of a Formal Structure

The introduction section.

Many students will find that writing a structured introduction gets them started and gives them the focus needed to significantly improve their entire paper.

Introductions usually have three parts:

presentation of the problem statement, the topic, or the research inquiry

purpose and focus of your paper

summary or overview of the writer’s position or arguments

In the first part of the introduction—the presentation of the problem or the research inquiry—state the problem or express it so that the question is implied. Then, sketch the background on the problem and review the literature on it to give your readers a context that shows them how your research inquiry fits into the conversation currently ongoing in your subject area.

In the second part of the introduction, state your purpose and focus. Here, you may even present your actual thesis. Sometimes your purpose statement can take the place of the thesis by letting your reader know your intentions.

The third part of the introduction, the summary or overview of the paper, briefly leads readers through the discussion, forecasting the main ideas and giving readers a blueprint for the paper.

The following example provides a blueprint for a well-organized introduction.

Example of an Introduction

Entrepreneurial Marketing: The Critical Difference

In an article in the Harvard Business Review, John A. Welsh and Jerry F. White remind us that “a small business is not a little big business.” An entrepreneur is not a multinational conglomerate but a profit-seeking individual. To survive, he must have a different outlook and must apply different principles to his endeavors than does the president of a large or even medium-sized corporation. Not only does the scale of small and big businesses differ, but small businesses also suffer from what the Harvard Business Review article calls “resource poverty.” This is a problem and opportunity that requires an entirely different approach to marketing. Where large ad budgets are not necessary or feasible, where expensive ad production squanders limited capital, where every marketing dollar must do the work of two dollars, if not five dollars or even ten, where a person’s company, capital, and material well-being are all on the line—that is, where guerrilla marketing can save the day and secure the bottom line (Levinson, 1984, p. 9).

By reviewing the introductions to research articles in the discipline in which you are writing your research paper, you can get an idea of what is considered the norm for that discipline. Study several of these before you begin your paper so that you know what may be expected. If you are unsure of the kind of introduction your paper needs, ask your professor for more information. The introduction is normally written in present tense.

THE METHODS SECTION

The methods section of your research paper should describe in detail what methodology and special materials if any, you used to think through or perform your research. You should include any materials you used or designed for yourself, such as questionnaires or interview questions, to generate data or information for your research paper. You want to include any methodologies that are specific to your particular field of study, such as lab procedures for a lab experiment or data-gathering instruments for field research. The methods section is usually written in the past tense.

THE RESULTS SECTION

How you present the results of your research depends on what kind of research you did, your subject matter, and your readers’ expectations.

Quantitative information —data that can be measured—can be presented systematically and economically in tables, charts, and graphs. Quantitative information includes quantities and comparisons of sets of data.

Qualitative information , which includes brief descriptions, explanations, or instructions, can also be presented in prose tables. This kind of descriptive or explanatory information, however, is often presented in essay-like prose or even lists.

There are specific conventions for creating tables, charts, and graphs and organizing the information they contain. In general, you should use them only when you are sure they will enlighten your readers rather than confuse them. In the accompanying explanation and discussion, always refer to the graphic by number and explain specifically what you are referring to; you can also provide a caption for the graphic. The rule of thumb for presenting a graphic is first to introduce it by name, show it, and then interpret it. The results section is usually written in the past tense.

THE DISCUSSION SECTION

Your discussion section should generalize what you have learned from your research. One way to generalize is to explain the consequences or meaning of your results and then make your points that support and refer back to the statements you made in your introduction. Your discussion should be organized so that it relates directly to your thesis. You want to avoid introducing new ideas here or discussing tangential issues not directly related to the exploration and discovery of your thesis. The discussion section, along with the introduction, is usually written in the present tense.

THE CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS SECTION

Your conclusion ties your research to your thesis, binding together all the main ideas in your thinking and writing. By presenting the logical outcome of your research and thinking, your conclusion answers your research inquiry for your reader. Your conclusions should relate directly to the ideas presented in your introduction section and should not present any new ideas.

You may be asked to present your recommendations separately in your research assignment. If so, you will want to add some elements to your conclusion section. For example, you may be asked to recommend a course of action, make a prediction, propose a solution to a problem, offer a judgment, or speculate on the implications and consequences of your ideas. The conclusions and recommendations section is usually written in the present tense.

Key Takeaways

- For the formal academic research assignment, consider an organizational pattern typically used for primary academic research.

- The pattern includes the following: introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusions/recommendations.

Mailing Address: 3501 University Blvd. East, Adelphi, MD 20783 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . © 2022 UMGC. All links to external sites were verified at the time of publication. UMGC is not responsible for the validity or integrity of information located at external sites.

Table of Contents: Online Guide to Writing

Chapter 1: College Writing

How Does College Writing Differ from Workplace Writing?

What Is College Writing?

Why So Much Emphasis on Writing?

Chapter 2: The Writing Process

Doing Exploratory Research

Getting from Notes to Your Draft

Introduction

Prewriting - Techniques to Get Started - Mining Your Intuition

Prewriting: Targeting Your Audience

Prewriting: Techniques to Get Started

Prewriting: Understanding Your Assignment

Rewriting: Being Your Own Critic

Rewriting: Creating a Revision Strategy

Rewriting: Getting Feedback

Rewriting: The Final Draft

Techniques to Get Started - Outlining

Techniques to Get Started - Using Systematic Techniques

Thesis Statement and Controlling Idea

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Freewriting

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Summarizing Your Ideas

Writing: Outlining What You Will Write

Chapter 3: Thinking Strategies

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone: Style Through Vocabulary and Diction

Critical Strategies and Writing

Critical Strategies and Writing: Analysis

Critical Strategies and Writing: Evaluation

Critical Strategies and Writing: Persuasion

Critical Strategies and Writing: Synthesis

Developing a Paper Using Strategies

Kinds of Assignments You Will Write

Patterns for Presenting Information

Patterns for Presenting Information: Critiques

Patterns for Presenting Information: Discussing Raw Data

Patterns for Presenting Information: General-to-Specific Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Specific-to-General Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Summaries and Abstracts

Supporting with Research and Examples

Writing Essay Examinations

Writing Essay Examinations: Make Your Answer Relevant and Complete

Writing Essay Examinations: Organize Thinking Before Writing

Writing Essay Examinations: Read and Understand the Question

Chapter 4: The Research Process

Planning and Writing a Research Paper

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Ask a Research Question

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Cite Sources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Collect Evidence

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Decide Your Point of View, or Role, for Your Research

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Draw Conclusions

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Find a Topic and Get an Overview

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Manage Your Resources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Outline

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Survey the Literature

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Work Your Sources into Your Research Writing

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Human Resources

Research Resources: What Are Research Resources?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Electronic Resources

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Print Resources

Structuring the Research Paper: Formal Research Structure

Structuring the Research Paper: Informal Research Structure

The Nature of Research

The Research Assignment: How Should Research Sources Be Evaluated?

The Research Assignment: When Is Research Needed?

The Research Assignment: Why Perform Research?

Chapter 5: Academic Integrity

Academic Integrity

Giving Credit to Sources

Giving Credit to Sources: Copyright Laws

Giving Credit to Sources: Documentation

Giving Credit to Sources: Style Guides

Integrating Sources

Practicing Academic Integrity

Practicing Academic Integrity: Keeping Accurate Records

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Paraphrasing Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Quoting Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Summarizing Your Sources

Types of Documentation

Types of Documentation: Bibliographies and Source Lists

Types of Documentation: Citing World Wide Web Sources

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - APA Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - CSE/CBE Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - Chicago Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - MLA Style

Types of Documentation: Note Citations

Chapter 6: Using Library Resources

Finding Library Resources

Chapter 7: Assessing Your Writing

How Is Writing Graded?

How Is Writing Graded?: A General Assessment Tool

The Draft Stage

The Draft Stage: The First Draft

The Draft Stage: The Revision Process and the Final Draft

The Draft Stage: Using Feedback

The Research Stage

Using Assessment to Improve Your Writing

Chapter 8: Other Frequently Assigned Papers

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Article and Book Reviews

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Reaction Papers

Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Adapting the Argument Structure

Writing Arguments: Purposes of Argument

Writing Arguments: References to Consult for Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Anticipate Active Opposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Determine Your Organization

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Develop Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Introduce Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - State Your Thesis or Proposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Write Your Conclusion

Writing Arguments: Types of Argument

Appendix A: Books to Help Improve Your Writing

Dictionaries

General Style Manuals

Researching on the Internet

Special Style Manuals

Writing Handbooks

Appendix B: Collaborative Writing and Peer Reviewing

Collaborative Writing: Assignments to Accompany the Group Project

Collaborative Writing: Informal Progress Report

Collaborative Writing: Issues to Resolve

Collaborative Writing: Methodology

Collaborative Writing: Peer Evaluation

Collaborative Writing: Tasks of Collaborative Writing Group Members

Collaborative Writing: Writing Plan

General Introduction

Peer Reviewing

Appendix C: Developing an Improvement Plan

Working with Your Instructor’s Comments and Grades

Appendix D: Writing Plan and Project Schedule

Devising a Writing Project Plan and Schedule

Reviewing Your Plan with Others

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

Research Guide

Chapter 5 sections of a paper.

Now that you have identified your research question, have compiled the data you need, and have a clear argument and roadmap, it is time for you to write. In this Module, I will briefly explain how to develop different sections of your research paper. I devote a different chapter to the empirical section. Please take into account that these are guidelines to follow in the different section, but you need to adapt them to the specific context of your paper.

5.1 The Abstract

The abstract of a research paper contains the most critical aspects of the paper: your research question, the context (country/population/subjects and period) analyzed, the findings, and the main conclusion. You have about 250 characters to attract the attention of the readers. Many times (in fact, most of the time), readers will only read the abstract. You need to “sell” your argument and entice them to continue reading. Thus, abstracts require good and direct writing. Use journalistic style. Go straight to the point.

There are two ways in which an abstract can start:

By introducing what motivates the research question. This is relevant when some context may be needed. When there is ‘something superior’ motivating your project. Use this strategy with care, as you may confuse the reader who may have a hard time understanding your research question.

By introducing your research question. This is the best way to attract the attention of your readers, as they can understand the main objective of the paper from the beginning. When the question is clear and straightforward this is the best method to follow.

Regardless of the path you follow, make sure that the abstract only includes short sentences written in active voice and present tense. Remember: Readers are very impatient. They will only skim the papers. You should make it simple for readers to find all the necessary information.

5.2 The Introduction

The introduction represents the most important section of your research paper. Whereas your title and abstract guide the readers towards the paper, the introduction should convince them to stay and read the rest of it. This section represents your opportunity to state your research question and link it to the bigger issue (why does your research matter?), how will you respond it (your empirical methods and the theory behind), your findings, and your contribution to the literature on that issue.

I reviewed the “Introduction Formulas” guidelines by Keith Head , David Evans and Jessica B. Hoel and compiled their ideas in this document, based on what my I have seen is used in papers in political economy, and development economics.

This is not a set of rules, as papers may differ depending on the methods and specific characteristics of the field, but it can work as a guideline. An important takeaway is that the introduction will be the section that deserves most of the attention in your paper. You can write it first, but you need to go back to it as you make progress in the rest of teh paper. Keith Head puts it excellent by saying that this exercise (going back and forth) is mostly useful to remind you what are you doing in the paper and why.

5.2.1 Outline

What are the sections generally included in well-written introductions? According to the analysis of what different authors suggest, a well-written introduction includes the following sections:

- Hook: Motivation, puzzle. (1-2 paragraphs)

- Research Question: What is the paper doing? (1 paragraph)

- Antecedents: (optional) How your paper is linked to the bigger issue. Theory. (1-2 paragraphs)

- Empirical approach: Method X, country Y, dataset Z. (1-2 paragraphs)

- Detailed results: Don’t make the readers wait. (2-3 paragraphs)

- Mechanisms, robustness and limitations: (optional) Your results are valid and important (1 paragraph)

- Value added: Why is your paper important? How is it contributing to the field? (1-3 paragraphs)

- Roadmap A convention (1 paragraph)

Now, let’s describe the different sections with more detail.

5.2.1.1 1. The Hook

Your first paragraph(s) should attract the attention of the readers, showing them why your research topic is important. Some attributes here are:

- Big issue, specific angle: This is the big problem, here is this aspect of the problem (that your research tackles)

- Big puzzle: There is no single explanation of the problem (you will address that)

- Major policy implemented: Here is the issue and the policy implemented (you will test if if worked)

- Controversial debate: some argue X, others argue Y

5.2.1.2 2. Research Question

After the issue has been introduced, you need to clearly state your research question; tell the reader what does the paper researches. Some words that may work here are:

- I (We) focus on

- This paper asks whether

- In this paper,

- Given the gaps in knoweldge, this paper

- This paper investigates

5.2.1.3 3. Antecedents (Optional section)

I included this section as optional as it is not always included, but it may help to center the paper in the literature on the field.

However, an important warning needs to be placed here. Remember that the introduction is limited and you need to use it to highlight your work and not someone else’s. So, when the section is included, it is important to:

- Avoid discussing paper that are not part of the larger narrative that surrounds your work

- Use it to notice the gaps that exist in the current literature and that your paper is covering

In this section, you may also want to include a description of theoretical framework of your paper and/or a short description of a story example that frames your work.

5.2.1.4 4. Empirical Approach

One of the most important sections of the paper, particularly if you are trying to infer causality. Here, you need to explain how you are going to answer the research question you introduced earlier. This section of the introduction needs to be succint but clear and indicate your methodology, case selection, and the data used.

5.2.1.5 5. Overview of the Results

Let’s be honest. A large proportion of the readers will not go over the whole article. Readers need to understand what you’re doing, how and what did you obtain in the (brief) time they will allocate to read your paper (some eager readers may go back to some sections of the paper). So, you want to introduce your results early on (another reason you may want to go back to the introduction multiple times). Highlight the results that are more interesting and link them to the context.

According to David Evans , some authors prefer to alternate between the introduction of one of the empirical strategies, to those results, and then they introduce another empirical strategy and the results. This strategy may be useful if different empirical methodologies are used.

5.2.1.6 6. Mechanisms, Robustness and Limitations (Optional Section)

If you have some ideas about what drives your results (the mechanisms involved), you may want to indicate that here. Some of the current critiques towards economics (and probably social sciences in general) has been the strong focus on establishing causation, with little regard to the context surrounding this (if you want to hear more, there is this thread from Dani Rodrick ). Agency matters and if the paper can say something about this (sometimes this goes beyond our research), you should indicate it in the introduction.

You may also want to briefly indicate how your results are valid after trying different specifications or sources of data (this is called Robustness checks). But you also want to be honest about the limitations of your research. But here, do not diminish the importance of your project. After you indicate the limitations, finish the paragraph restating the importance of your findings.

5.2.1.7 7. Value Added

A very important section in the introduction, these paragraphs help readers (and reviewers) to show why is your work important. What are the specific contributions of your paper?

This section is different from section 3 in that it points out the detailed additions you are making to the field with your research. Both sections can be connected if that fits your paper, but it is quite important that you keep the focus on the contributions of your paper, even if you discuss some literature connected to it, but always with the focus of showing what your paper adds. References (literature review) should come after in the paper.

5.2.1.8 8. Roadmap

A convention for the papers, this section needs to be kept short and outline the organization of the paper. To make it more useful, you can highlight some details that might be important in certain sections. But you want to keep this section succint (most readers skip this paragraph altogether).

5.2.2 In summary

The introduction of your paper will play a huge role in defining the future of your paper. Do not waste this opportunity and use it as well as your North Star guiding your path throughout the rest of the paper.

5.3 Context (Literature Review)

Do you need a literature review section?

5.4 Conclusion

How to Write a Body of a Research Paper

The main part of your research paper is called “the body.” To write this important part of your paper, include only relevant information, or information that gets to the point. Organize your ideas in a logical order—one that makes sense—and provide enough details—facts and examples—to support the points you want to make.

Logical Order

Transition words and phrases, adding evidence, phrases for supporting topic sentences.

- Transition Phrases for Comparisons

- Transition Phrases for Contrast

- Transition Phrases to Show a Process

- Phrases to Introduce Examples

- Transition Phrases for Presenting Evidence

How to Make Effective Transitions

Examples of effective transitions, drafting your conclusion, writing the body paragraphs.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

- The third and fourth paragraphs follow the same format as the second:

- Transition or topic sentence.

- Topic sentence (if not included in the first sentence).

- Supporting sentences including a discussion, quotations, or examples that support the topic sentence.

- Concluding sentence that transitions to the next paragraph.

The topic of each paragraph will be supported by the evidence you itemized in your outline. However, just as smooth transitions are required to connect your paragraphs, the sentences you write to present your evidence should possess transition words that connect ideas, focus attention on relevant information, and continue your discussion in a smooth and fluid manner.

You presented the main idea of your paper in the thesis statement. In the body, every single paragraph must support that main idea. If any paragraph in your paper does not, in some way, back up the main idea expressed in your thesis statement, it is not relevant, which means it doesn’t have a purpose and shouldn’t be there.

Each paragraph also has a main idea of its own. That main idea is stated in a topic sentence, either at the beginning or somewhere else in the paragraph. Just as every paragraph in your paper supports your thesis statement, every sentence in each paragraph supports the main idea of that paragraph by providing facts or examples that back up that main idea. If a sentence does not support the main idea of the paragraph, it is not relevant and should be left out.

A paper that makes claims or states ideas without backing them up with facts or clarifying them with examples won’t mean much to readers. Make sure you provide enough supporting details for all your ideas. And remember that a paragraph can’t contain just one sentence. A paragraph needs at least two or more sentences to be complete. If a paragraph has only one or two sentences, you probably haven’t provided enough support for your main idea. Or, if you have trouble finding the main idea, maybe you don’t have one. In that case, you can make the sentences part of another paragraph or leave them out.

Arrange the paragraphs in the body of your paper in an order that makes sense, so that each main idea follows logically from the previous one. Likewise, arrange the sentences in each paragraph in a logical order.

If you carefully organized your notes and made your outline, your ideas will fall into place naturally as you write your draft. The main ideas, which are building blocks of each section or each paragraph in your paper, come from the Roman-numeral headings in your outline. The supporting details under each of those main ideas come from the capital-letter headings. In a shorter paper, the capital-letter headings may become sentences that include supporting details, which come from the Arabic numerals in your outline. In a longer paper, the capital letter headings may become paragraphs of their own, which contain sentences with the supporting details, which come from the Arabic numerals in your outline.

In addition to keeping your ideas in logical order, transitions are another way to guide readers from one idea to another. Transition words and phrases are important when you are suggesting or pointing out similarities between ideas, themes, opinions, or a set of facts. As with any perfect phrase, transition words within paragraphs should not be used gratuitously. Their meaning must conform to what you are trying to point out, as shown in the examples below: