Journal of Oral Research and Review Latest Publications

Total documents, published by medknow publications.

- Latest Documents

- Most Cited Documents

- Contributed Authors

- Related Sources

- Related Keywords

Biomaterials for periodontal regeneration: A brief overview

Photobiomodulation therapy in the treatment of a palatal ulcer, temporomandibular joint ankylosis pattern, causes, and management among pediatric patient attending a tertiary hospital in bangladesh, unraveling coronoplasty in periodontics, the war between amalgam and composite: a critical review, a case of ankyloglossia, knowledge, practice, and awareness of dental undergraduate and postgraduate students toward postexposure prophylaxis and needlestick injuries: a descriptive cross-sectional institutional dental hospital study, hemodynamic changes in pediatric dental patients using 2% lignocaine, buffered lignocaine, and 4% articaine in pediatric dental procedures, solitary median maxillary central incisor: gateway to diagnosis of systemic diseases, autologous platelet concentrates in periodontal regenerative therapy: a brief overview, export citation format, share document.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 23 May 2024

Effectiveness of school oral health programs in children and adolescents: an umbrella review

- Upendra Singh Bhadauria 1 ,

- Harsh Priya 2 ,

- Bharathi Purohit 1 &

- Ankur Singh 3

Evidence-Based Dentistry ( 2024 ) Cite this article

31 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

To evaluate the systematic reviews assessing the effectiveness of any type of school-based oral health programs in children and adolescents.

Methodology

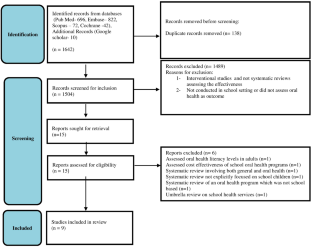

A two-staged search strategy comprising electronic databases and registries based on systematic reviews was employed to evaluate the effectiveness of school-based interventions. The quality assessment of the systematic reviews was carried out using the Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR-2) tool. The Corrected Covered Area was used to evaluate the degree of overlap.

Nine reviews were included in this umbrella review. The Critical Covered Area reported moderate overlap (5.70%) among the primary studies. The assessment of risk of bias revealed one study with a high level confidence; one with moderate whereas all other studies with critically low confidence. Inconclusive evidence related to improvements in dental caries and gingival status was reported whereas, plaque status improved in a major proportion of the reviews. Knowledge, attitude, and behavior significantly increased in students receiving educational interventions when compared to those receiving usual care.

Conclusions

The evidence points to the positive impact of these interventions in behavioral changes and clinical outcomes only on a short term basis. There is a need for long-term follow-up studies to substantiate the outcomes of these interventions.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 4 print issues and online access

251,40 € per year

only 62,85 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

School dental screening programmes for oral health: Cochrane systematic review

How can children be involved in developing oral health education interventions?

Could behavioural intervention improve oral hygiene in adolescents?

Data availability.

The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (US); 2021 Dec. Section 1, Effect of Oral Health on the Community, Overall Well-Being, and the Economy. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK578297/ .

Dadipoor S, Ghaffari M, Alipour A, Safari-Moradabadi A. Effects of educational interventions on oral hygiene: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Research Square; 2019. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.15898/v1 .

Stein C, Santos NML, Hilgert JB, Hugo FN. Effectiveness of oral health education on oral hygiene and dental caries in schoolchildren: systematic review and meta-analysis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018;46:30–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12325 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bramantoro T, Santoso CMA, Hariyani N, Setyowati D, Zulfiana AA, Nor NAM, Nagy A, et al. Effectiveness of the school-based oral health promotion programmes from preschool to high school: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0256007. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256007 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hakojärvi HR, Selänne L, Salanterä S. Child involvement in oral health education interventions - a systematic review of randomised controlled studies. Community Dent Health. 2019;36:286–92.

PubMed Google Scholar

Gurav KM, Shetty V, Vinay V, Bhor K, Jain C, Divekar P. Effectiveness of oral health educational methods among school children aged 5-16 years in improving their oral health status: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2022;15:338–49.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Geetha Priya PR, Asokan S, Janani RG, Kandaswamy D. Effectiveness of school dental health education on the oral health status and knowledge of children: a systematic review. Indian J Dent Res. 2019;30:437–49.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Akera P, Kennedy SE, Lingam R, Obwolo MJ, Schutte AE, Richmond R. Effectiveness of primary school-based interventions in improving oral health of children in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22:264.

Prabhu S, John J. Oral Health Education for improving oral health status of school children – a systematic review. IOSR-JDMS. 2015;14:101–6.

Google Scholar

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Becker LA, Pieper D, Hartling L Chapter V: overviews of reviews. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.3 (updated 2022) . editors. Cochrane; 2022. Available from. [Accessed on December 1, 2022]. www.training.cochrane.org/ .

Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Editors. JBI; 2020. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-01 . Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global .

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71 .

Pieper D, Antoine S-L, Mathes T, Neugebauer EAM, Eikermann M. Systematic review finds overlapping reviews were not mentioned in every other overview. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:368–75.

Sardana D, Ritto FP, Ciesla D, Fagan TR. Evaluation of oral health education programs for oral health of individuals with visual impairment: an umbrella review. Spec Care Dentist. 2023;43:751–64.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or nonrandomized studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008.j4008 .

Cooper AM, O’Malley LA, Elison SN, Armstrong R, Burnside G, Adair P, et al. Primary school-based behavioural interventions for preventing caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:CD009378. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bhadauria US, Gupta V, Arora H. Interventions in improving the oral hygiene of visually impaired individuals: a systematic review. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30:e1092–e1100. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13517 .

Download references

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Division of Public Health Dentistry, CDER-AIIMS, New Delhi, India

Upendra Singh Bhadauria & Bharathi Purohit

Division of Public Health Dentistry, Centre for Dental Education and Research, AIIMS, New Delhi, India

Harsh Priya

Australian Research Council DECRA Senior Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia

Ankur Singh

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

USB: Concept, design, drafting of manuscript, BP: Data assembly, revising of article, HP: Data assembly, AS: Critical revision of the article.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Harsh Priya .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information, rights and permissions.

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bhadauria, U.S., Priya, H., Purohit, B. et al. Effectiveness of school oral health programs in children and adolescents: an umbrella review. Evid Based Dent (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41432-024-01013-7

Download citation

Received : 07 March 2024

Accepted : 18 April 2024

Published : 23 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41432-024-01013-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Current Issue

This year, the Journal of Oral Research , after rethinking its editorial policy, mainly with regard to periodicity, has adopted the modality of continuous publication. This new challenge for the editorial team of the Journal of Oral Research implies a greater commitment to the community and all the actors in the communication process of scientific research. We strive to optimize the availability of manuscripts as they become ready to be published, and continue to offer a space to publicize the findings and innovations in all areas of dentistry, this way fulfilling the role of the Journal in the wide dissemination of open science.

Join this challenge and be part of the Journal of Oral Research team, you can complete the form at this link: https://forms.gle/3RA5x9RJTM6vYYZH9

Ahead of print proofs

Do you want to be a reviewer?

- Español (España)

- Português (Brasil)

INDEXACIONES

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

J Oral Res is an open access publication, and the Official publication of the Faculty of Dentistry of the University of Concepción, Chile.

Distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license and must be properly cited.

Printed ISSN 0719-2460 | ISSN online 0719-2479 | Address: Avda. Roosevelt # 1550, 3rd floor, Concepción, Chile.

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

Size of box indicates number of estimates.

eTable 1. Search Strategy

eTable 2. Risk of Bias Assessment Using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist Tool

eTable 3. Time From Symptom Presentation to Diagnosis Measurement Across Studies

eFigure 1. Forest Plots of Proportions of Presenting Signs and Symptoms for EOCRC, by Sign or Symptom

eFigure 2. Pooled Proportions of Presenting Signs and Symptoms for EOCRC by Geography

eFigure 3. Pooled Proportions of Presenting Signs and Symptoms for EOCRC; Stratified Analysis by Age Group

eFigure 4. Pooled Proportions of Presenting Signs and Symptoms for EOCRC, Stratified Analysis by Risk of Bias

eFigure 5. Pooled Proportions of Presenting Signs and Symptoms for EOCRC, Stratified Analysis by Data Source

eFigure 6. Histograms of Mean and Median Diagnosis Stratified by Data Source

Data Sharing Statement

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Demb J , Kolb JM , Dounel J, et al. Red Flag Signs and Symptoms for Patients With Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer : A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis . JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(5):e2413157. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.13157

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Red Flag Signs and Symptoms for Patients With Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer : A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- 1 Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla

- 2 Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, California

- 3 Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego, La Jolla

- 4 Division of Gastroenterology, Washington University in St Louis, St Louis, Missouri

- 5 Department of Internal Medicine, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, New York

- 6 Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, Missouri

- 7 UC San Diego Library, University of California San Diego, La Jolla

- 8 University of Colorado Cancer Center, Colorado School of Public Health, Aurora

- 9 Molecular Medicine Unit, Department of Medicine, Biomedical Research Institute of Salamanca, University of Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain

- 10 Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee

- 11 Division of Medical Oncology, University of Colorado Denver Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora

- 12 Division of Biomedical Informatics, Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego, La Jolla

- 13 Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

- 14 Jennifer Moreno Veteran Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, San Diego, California

- 15 Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, Missouri

- 16 Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, Missouri

- 17 Surgery Department, Vithas Arturo Soria University Hospital, Madrid, Spain

Question In patients with early-onset colorectal cancer (EOCRC), what are the most common presenting signs and symptoms, what is their association with EOCRC risk, and what is the time from presentation to diagnosis?

Findings In this systematic review and meta-analysis including 81 studies and more than 24.9 million patients, nearly half of individuals with EOCRC presented with hematochezia and abdominal pain and one-quarter presented with altered bowel habits. Delays in diagnosis of 4 to 6 months from time of initial presentation were common.

Meaning These findings underscore the need to identify signs and symptoms concerning for EOCRC and complete timely diagnostic workup for individuals without an alternative diagnosis or sign or symptom resolution.

Importance Early-onset colorectal cancer (EOCRC), defined as a diagnosis at younger than age 50 years, is increasing, and so-called red flag signs and symptoms among these individuals are often missed, leading to diagnostic delays. Improved recognition of presenting signs and symptoms associated with EOCRC could facilitate more timely diagnosis and impact clinical outcomes.

Objective To report the frequency of presenting red flag signs and symptoms among individuals with EOCRC, to examine their association with EOCRC risk, and to measure variation in time to diagnosis from sign or symptom presentation.

Data Sources PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, and Web of Science were searched from database inception through May 2023.

Study Selection Studies that reported on sign and symptom presentation or time from sign and symptom presentation to diagnosis for patients younger than age 50 years diagnosed with nonhereditary CRC were included.

Data Extraction and Synthesis Data extraction and quality assessment were performed independently in duplicate for all included studies using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses reporting guidelines. Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools were used to measure risk of bias. Data on frequency of signs and symptoms were pooled using a random-effects model.

Main Outcomes and Measures Outcomes of interest were pooled proportions of signs and symptoms in patients with EOCRC, estimates for association of signs and symptoms with EOCRC risk, and time from sign or symptom presentation to EOCRC diagnosis.

Results Of the 12 859 unique articles initially retrieved, 81 studies with 24 908 126 patients younger than 50 years were included. The most common presenting signs and symptoms, reported by 78 included studies, were hematochezia (pooled prevalence, 45% [95% CI, 40%-50%]), abdominal pain (pooled prevalence, 40% [95% CI, 35%-45%]), and altered bowel habits (pooled prevalence, 27% [95% CI, 22%-33%]). Hematochezia (estimate range, 5.2-54.0), abdominal pain (estimate range, 1.3-6.0), and anemia (estimate range, 2.1-10.8) were associated with higher EOCRC likelihood. Time from signs and symptoms presentation to EOCRC diagnosis was a mean (range) of 6.4 (1.8-13.7) months (23 studies) and a median (range) of 4 (2.0-8.7) months (16 studies).

Conclusions and Relevance In this systematic review and meta-analysis of patients with EOCRC, nearly half of individuals presented with hematochezia and abdominal pain and one-quarter with altered bowel habits. Hematochezia was associated with at least 5-fold increased EOCRC risk. Delays in diagnosis of 4 to 6 months were common. These findings highlight the need to identify concerning EOCRC signs and symptoms and complete timely diagnostic workup, particularly for individuals without an alternative diagnosis or sign or symptom resolution.

The incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer (EOCRC), defined as a diagnosis at younger than age 50 years, has been increasing at an alarming rate, in contrast to the decreasing CRC rate among older individuals. 1 These trends have been observed globally, 2 - 9 and EOCRC rates in the US are projected to increase by at least 140% by 2030. 10 These worrisome epidemiologic findings prompted an update in US CRC screening guidelines to begin screening among individuals at average risk at age 45 years. 11

Outside of screening, early detection of symptomatic EOCRC remains a priority. Delayed diagnosis may be a result of late patient presentation and lack of clinician knowledge of common CRC symptoms, such as hematochezia or abdominal and pelvic pain, and signs, such as iron deficiency anemia. Patients and clinicians alike may downplay symptom severity and fail to recognize key red flags and clinical cues that should trigger suspicion of CRC. 12 - 15 Furthermore, diagnostic algorithms in adults younger than 50 years often favor a less invasive and more conservative watchful waiting strategy, which could result in missed opportunities for intervention. 16 Therefore, defining the prevalence of these common signs and symptoms and their associated EOCRC risk is a critical first step to inform care pathways.

Additionally, delays in diagnostic workup after sign or symptom presentation are up to 40% longer in younger compared with older individuals with CRC, which may contribute to greater proportion of late stage diagnosis (58%-89% vs 30%-63%) and increasing EOCRC mortality rates in the US (1.3% per year from 2008-2017). 17 - 20 Mitigation strategies to expedite timely diagnoses may help decrease EOCRC morbidity and mortality. To address these gaps and pressing clinical issues, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to quantify the prevalence of signs and symptoms at EOCRC presentation, their association with EOCRC risk, and time to diagnosis.

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to answer 3 questions. First, which signs and symptoms are most commonly present in individuals diagnosed with EOCRC? Second, what is the association between EOCRC sign or symptom exposure and EOCRC risk? Third, what is the time from sign or symptom presentation to diagnosis of EOCRC? This study is registered on Prospero (identifier: CRD42020181296 ). We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses ( PRISMA ) reporting guideline.

A comprehensive literature search was performed in PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, and Web of Science Core Collection from inception through May 2023 to identify candidate studies for inclusion (eTable 1 in Supplement 1 ). Results were exported and deduplicated in EndNote (Clarivate) using the Bramer method. 21

Study review and data extraction were performed in Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation). Two independent reviewers (among J. Demb, J.M.K, J. Dounel, C.D.L.F., S.M.A. and F.E.R.V.) screened titles and abstracts for eligibility and reviewed the full text of all designated articles, with a third reviewer (S.G.) providing consensus if needed. Studies that reported on sign or symptom presentation or time to diagnosis for patients younger than age 50 years diagnosed with nonhereditary CRC were included. Studies with fewer than 15 eligible patients, most patients younger than age 18 years, or published before 1996 or in which more than half of the study period occurred before 1996—the year when EOCRC incidence rates began increasing, notably among adults aged 40 to 49 years—were excluded. 22 Meeting abstracts, reviews, non-English articles, and nonoriginal research were excluded.

Two reviewers (J. Demb and J.M.K.) extracted relevant data from articles meeting inclusion criteria, including study characteristics (time period, design, country, and population composition), the proportion of patients with EOCRC presenting with each sign and symptom, relative estimates for association of signs and symptoms with EOCRC risk, and time from symptom presentation to diagnosis, as defined by either patient report of onset of symptoms or medical record capture of symptom presentation. Risk of bias assessment was performed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal tools for cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, and case-control studies. 23 These tools include questions characterizing a study’s sources of bias and internal validity, measurement of exposures, outcomes and follow-up, and potential risk of selection or information bias. Risk of bias was graded and separated into 3 categories: low risk, 75% to 100% of checklist items included; moderate risk, 50% to 75% of checklist items; and high risk, less than 50% of checklist items.

For the assessment of signs and symptoms among patients with EOCRC, sign and symptom proportions were pooled individually across studies and proportions were compared using forest plots. Pooled prevalence estimates were calculated via random-effects meta-analysis using the Hartung and Knapp method, which has been found to perform well when between-study heterogeneity is high and study sample sizes are similar. 24 , 25 Stratified analyses were performed to measure pooled estimates based on specific study characteristics to assess potential variations in estimates, including geographic study location (US vs non-US), study age groups (≤40 years and ≤50 years), risk of bias (low, moderate, high), and data source type (claims or medical record, patient-reported, not well defined). Meta-regression was also performed adjusting for percentage of male study participants and the year of study publication.

We assessed heterogeneity between study-specific estimates using the inconsistency index ( I 2 ), and used cutoffs of 0% to 30%, 30% to 60%, 60% to 90%, and 90% to 100% to suggest minimal, moderate, substantial, and considerable heterogeneity, respectively. Between-study sources of heterogeneity were investigated using subgroup analyses by stratifying original estimates according to study characteristics. In this analysis, P < .10 differences between subgroups was considered statistically significant (ie, a value of P < .10 suggests that stratifying based on that particular study characteristic partly explained the heterogeneity observed in the analysis).

Signs and symptoms with estimates of EOCRC risk across at least 3 studies were described using forest plots. Due to significant heterogeneity across studies, particularly the composition of the analytic samples, we were unable to conduct meta-analysis of signs and symptoms and their association with EOCRC risk. Time to diagnosis was defined as the date of sign or symptom presentation to the date of diagnosis and stratified according to the data source type, since this was measured differently across studies. These data were aggregated based on whether the estimate was a mean or median, and the distributions of mean and median times to diagnosis were evaluated.

P values were 2-sided, and statistical significance was set at P < .10. All analyses were performed using R statistical software version 4.1.3 (R Project for Statistical Computing), with plots and statistical analyses calculated using the suite of functions and commands within the meta package and the ggplot2 package, with R code provided in the eMethods in Supplement 1 . 26 Data were analyzed from August 2022 and April 2024.

Of the 12 859 unique articles retrieved, 699 full texts were reviewed, and 81 studies 12 , 13 , 18 , 27 - 104 were included ( Figure 1 and Table ). There were 76 cross-sectional studies, 12 , 13 , 18 , 27 - 35 , 37 - 43 , 45 , 46 , 48 - 92 , 94 , 96 - 104 4 case-control studies, 44 , 47 , 93 , 95 and 1 cohort study. 36 Studies were performed in Africa (5 studies), 31 , 41 , 54 , 65 , 84 Asia or the Middle East (26 studies), 18 , 35 , 37 , 42 , 48 , 49 , 51 - 53 , 56 , 62 , 66 , 67 , 71 , 77 , 78 , 80 , 82 , 85 , 96 , 99 - 104 Europe (19 studies), 28 , 29 , 40 , 43 , 45 , 46 , 50 , 55 , 57 , 58 , 60 , 63 , 64 , 72 , 73 , 75 , 87 , 91 , 93 North America (23 studies), 12 , 27 , 32 - 34 , 36 , 39 , 44 , 47 , 59 , 61 , 68 - 70 , 74 , 81 , 86 , 88 , 92 , 94 , 95 , 97 , 98 South America (5 studies), 30 , 38 , 83 , 89 , 90 and Oceania (2 studies). 76 , 79 There were 67 studies 12 , 13 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 32 - 34 , 36 , 38 - 40 , 44 , 45 , 47 , 48 , 51 - 77 , 79 , 81 , 83 , 84 , 86 - 102 , 104 deemed to have low risk of bias, 10 studies 18 , 29 , 31 , 35 , 37 , 46 , 50 , 80 , 85 , 103 with moderate risk of bias, and 4 studies 41 , 49 , 78 , 82 with high risk of bias, based on JBI checklists. Notable sources of bias included using patient-reported or inadequately defined measures of signs or symptoms and time to diagnosis (eTable 2 in Supplement 1 ).

There were 78 studies 12 , 13 , 18 , 31 - 92 , 94 - 108 that reported on 17 signs and symptoms at presentation, based on claims or medical records (66 studies), 12 , 13 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 32 - 34 , 38 - 40 , 42 - 45 , 47 , 48 , 51 - 77 , 79 , 81 , 83 , 84 , 86 - 92 , 94 - 104 patient report (6 studies), 18 , 29 , 37 , 46 , 80 , 82 or other (7 studies). 31 , 35 , 41 , 49 , 50 , 78 , 85 ( Figure 2 ; eFigure 1 in Supplement 1 ). In adults with EOCRC, the 3 most common presenting signs and symptoms were hematochezia (pooled prevalence, 45% [95% CI, 40%-50%]; 76 studies), 12 , 13 , 18 , 27 - 31 , 33 - 35 , 37 - 63 , 65 - 92 , 94 - 102 , 104 abdominal pain (pooled prevalence, 40% [95% CI, 35%-45%]; 73 studies), 12 , 13 , 18 , 27 - 31 , 33 - 35 , 37 - 40 , 42 - 67 , 70 - 85 , 87 - 92 , 94 - 102 , 104 and altered bowel habits, which included constipation, diarrhea, alternating bowel habits, or alternating diarrhea or constipation (pooled prevalence, 27% [95% CI, 22%-33%]; 63 studies). 12 , 18 , 28 - 31 , 33 - 35 , 37 - 39 , 43 - 68 , 70 - 72 , 74 - 80 , 83 - 85 , 87 , 88 , 90 , 92 , 94 - 96 , 98 - 100 , 102 , 104

When evaluating patterns by geography, the 3 most common presenting signs and symptoms were the same in both the US (20 studies) 12 , 33 , 34 , 39 , 44 , 47 , 59 , 61 , 68 - 70 , 74 , 81 , 86 , 88 , 92 , 94 , 95 , 97 , 98 and non-US (58 studies) 13 , 27 - 29 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 40 - 43 , 45 , 46 , 48 - 58 , 60 , 62 - 67 , 71 - 73 , 75 - 80 , 82 - 85 , 87 , 89 - 91 , 96 , 99 - 102 , 104 studies (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1 ). When stratifying by age of study population, there were 42 studies 12 , 18 , 28 - 30 , 32 - 34 , 38 - 40 , 42 , 44 , 45 , 48 , 50 , 54 , 61 , 62 , 67 , 69 - 71 , 74 , 75 , 78 , 80 , 82 , 86 - 92 , 94 - 100 including adults aged 50 years or younger and 25 studies 31 , 35 , 37 , 41 , 43 , 46 , 47 , 49 , 51 , 53 , 55 , 56 , 59 , 60 , 63 - 66 , 68 , 72 , 77 , 81 , 83 - 85 including adults aged 40 years and younger. In both groups, the top 3 presenting signs and symptoms were consistent with the primary results (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1 ). Primary results were unchanged in studies with low risk of bias; although in studies with moderate risk of bias, the 3 most common presenting signs and symptoms varied: hematochezia (pooled prevalence, 43% [95% CI, 34%-53%]; 9 studies), abdominal pain (pooled prevalence, 36% [95% CI, 26%-48%]; 9 studies) and obstruction (pooled prevalence, 24% [95% CI. 16%-33%]; 2 studies) (eFigure 4 in Supplement 1 ). When examining data source used to ascertain presenting sign or symptom, only studies with a poorly defined data source showed alternative most common presenting symptoms: loss of appetite (pooled prevalence, 58% [95% CI, 40%-74%]; 2 studies), hematochezia (pooled prevalence, 57% [95% CI, 37%-75%]; 7 studies), and abdominal pain (pooled prevalence, 54% [95% CI, 36%-71%]; 6 studies) (eFigure 5 in Supplement 1 ). Meta-regression analyses by percentage of male study participants or year of study publication across the 17 signs and symptoms for CRC were not found to account for a significant amount of between-study heterogeneity.

There were 5 studies 36 , 44 , 47 , 93 , 95 examining the association of EOCRC risk with abdominal pain, anemia, constipation, diarrhea, hematochezia, and nausea or vomiting ( Figure 3 ). Hematochezia (relative estimate range, 5.2-54.0; 5 studies), 36 , 44 , 47 , 93 , 95 abdominal pain (relative estimate range, 1.3-6.0; 4 studies), 44 , 47 , 93 , 95 and anemia (relative estimate range, 2.1-10.8; 3 studies) 36 , 44 , 47 were associated with higher likelihood of CRC compared with no CRC.

There were 34 studies 18 , 28 , 29 , 31 - 34 , 37 , 38 , 41 , 43 , 44 , 50 , 52 - 54 , 56 - 58 , 61 , 62 , 71 , 75 , 80 , 81 , 83 - 86 , 88 , 90 , 94 , 96 , 104 that reported a continuous measure of time from sign or symptom presentation to diagnosis, with 23 studies providing a mean result and 16 studies providing a median result (eTable 3 in Supplement 1 ). The time from symptom onset to EOCRC diagnosis was reported as a mean (range) of 6.4 (1.8-13.7) months and a median (range) of 4.1 (2.0-8.7) months ( Figure 4 ). When classifying time from sign or symptom onset to diagnosis by measurement type (medical record, patient reported, not well defined), there was considerable heterogeneity. When excluding studies with inadequately defined data sources, the time from symptom onset to EOCRC diagnosis was a mean (range) of 6.6 (3.0-13.7) months and median (range) of 3.8 (2.0-8.7) months (eFigure 6 in Supplement 1 ).

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, nearly half of individuals diagnosed with EOCRC presented with hematochezia and abdominal pain, which were associated with 5- to 54-fold and 1.3- to 6-fold increased likelihood of CRC, respectively. An interval of 4 to 6 months from symptom onset to EOCRC diagnosis was common. These findings underscore the need for clinicians to consider EOCRC as part of the differential diagnosis for patients presenting with potential red flag signs and symptoms, and to follow up through either confirmation of diagnosis and sign or symptom resolution when a benign cause is suspected, or colonoscopy referral to rule out CRC based on sign or symptom severity or absence of diagnosis or sign or symptom resolution after initial workup and management for a suspected benign cause.

Our finding that 45% of individuals with EOCRC presented with hematochezia aligns with current clinical paradigms—hematochezia (or rectal bleeding) is often cited as a common presenting symptom among patients with CRC. 105 In addition, the 5 studies 36 , 44 , 47 , 93 , 95 that measured the association between hematochezia and EOCRC risk found estimates between 5.1 and 54.0, underscoring the urgent need for these patients to undergo comprehensive diagnostic evaluation. A full colonoscopy should be pursued when individuals younger than 50 years present with hematochezia, according to guidelines from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and European Panel on the Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 106 , 107 A high index of suspicion for CRC in younger patients with hematochezia may be particularly useful to identify patients with high risk, given the high frequency and association with CRC.

Our review also found that nearly half of individuals with EOCRC reported abdominal pain, based on evidence from 73 studies 12 , 13 , 18 , 27 - 31 , 33 - 35 , 37 - 40 , 42 - 67 , 70 - 85 , 87 - 92 , 94 - 102 , 104 and a 1.3- to 6-fold positive association with EOCRC risk across 4 studies. 44 , 47 , 93 , 95 Given its association with a myriad of gastrointestinal conditions, the American Academy of Family Physicians recommends computed tomography for evaluating patients with acute right or left lower quadrant abdominal pain and ultrasonography for right upper quadrant pain, though the guidelines also recommend identifying associated symptoms to better focus a differential diagnosis. 108 It may be inefficient and unrealistic to perform colonoscopy for all adults younger than 45 years with isolated abdominal pain, given the low diagnostic yield 109 and insufficient capacity across the US to accommodate this group. Nevertheless, the fact that 40% of patients with EOCRC presented with abdominal pain and 27% presented with altered bowel habits reinforces that any new symptom should be comprehensively evaluated by a clinician. Our findings suggest that EOCRC should be part of the initial differential diagnosis, and that a plan for follow-up should be in place, such as a 30- to 60-day follow-up visit to confirm whether the original working diagnosis was correct, the red flag sign or symptom has resolved, or to refer for colonoscopy to exclude EOCRC if these criteria are not met. 110 We postulate that all benign causes of red flag signs or symptoms either can be diagnostically confirmed or should resolve with initial treatment. When an alternative diagnosis is not confirmed or signs or symptoms fail to resolve, a colonoscopy to rule out EOCRC should be pursued. Abdominal pain could serve as a marker to prompt further patient-clinician discussion about additional medical history, which could help determine whether further diagnostic work-up is warranted.

Globally and in the US, hematochezia, abdominal pain, and altered bowel habits were the 3 most common signs and symptoms. The fourth most common symptom differed based on geographic location—diarrhea among US studies and loss of appetite in non-US studies. The findings highlight how nonspecific symptoms are frequently present at EOCRC diagnosis and emphasize the need for medical professionals to be aware of the symptoms most associated with EOCRC, to refine clinical practice pathways and minimize late EOCRC detection.

The mean time from sign or symptom onset to EOCRC diagnosis was found to be 6.4 months (median, 4 months). A recent study using administrative claims data in Canada from 2003 to 2018 reported the greatest delay occurring between the first investigation and diagnosis (78 days) with short turnaround times between presentation and first investigation (5 days) or diagnosis and treatment start (23 days). Date of first presentation was defined by the physician visit related to the diagnostic examination (endoscopy, surgery, or imaging). 111 The data are mixed on whether decreasing time to diagnosis would improve outcomes, but it is well established that risk for progression to more advanced-stage disease increases over time. Another claims-based study from Canada found that young individuals with CRC had longer diagnostic intervals compared with middle-aged patients, although young patients with metastatic EOCRC had a short diagnostic interval, likely due to more noticeable or concerning symptoms. 32 Other studies found that differences between older and younger patients with CRC in stage at presentation were not just associated with delayed diagnosis, but could be associated with additional biological and genetic factors. 33

Nevertheless, it is prudent to address potential physician and patient barriers to timely workup. Younger patients may experience ongoing signs and symptoms and delay seeking medical attention. 88 Potential reasons for these delays include a patient believing they are too young to worry about cancer or a lack of access to primary care or health insurance. 88 , 110 Clarifying how these signs and symptoms are associated with EOCRC could give patients greater urgency to report these symptoms sooner, leading to quicker diagnostic workup and resolution. For clinicians, particularly those in primary care, recognition of clues and appropriate diagnostic workup for concerning signs and symptoms is paramount to early EOCRC detection. However, prior studies found that clinicians often dismiss these signs and symptoms or misattribute them to more benign conditions, such as attributing rectal bleeding to hemorrhoids, without conducting further diagnostic evaluation. 15 , 112 This can leave a potentially concerning sign or symptom unresolved for an extended period of time, and for some patients, delay EOCRC diagnosis. To avoid missing an EOCRC diagnosis, clinicians should work with patients to ensure concerning signs and symptoms undergo diagnostic evaluation to identify and resolve the underlying cause.

Our study has several strengths. Our approach distilled a tremendous amount of global data over several decades into clear and practical information that is immediately useful to clinicians. We applied strict study selection criteria to capture only individuals younger than 50 years with nonhereditary CRC to represent an individual with average risk diagnosed with EOCRC beginning in 1996, when EOCRC rates started to increase. The meta-analysis adjusted for or stratified by potential contributors to study heterogeneity, including study quality, age of study population, country of study origin, percentage of male study participants, and year of publication.

Our study has some limitations. There was significant heterogeneity across studies, which impacted our ability to meta-analyze some of our results. This was most significant in assessment of the associations of signs and symptoms with EOCRC, where a lack of a consistent comparator group hindered our ability to pool estimates for the associations. Additionally, we were unable to compare EOCRC risk against other potential outcomes, which might have better contextualized the relative risk. In our measurement of association of signs and symptoms with EOCRC, studies did not measure the potential likelihood of reverse causation—whether EOCRC was associated with sign or symptom presentation. We were unable to evaluate the impact of time to diagnosis on CRC outcomes due to a limited number of studies answering this question. In addition, sign- and symptom-based data extracted from studies used in this review were often extracted cross-sectionally to characterize patients with EOCRC at study baseline, limiting our access to stratified or more granular results by age, sex, race and ethnicity, or genetic ancestry, which could have better contextualized the burden of signs and symptoms and relevant EOCRC risk. We were unable to examine the constellation of signs and symptoms since we lacked individual-level data from each study and could not provide a positive predictive value for symptoms. However, we anticipate patients may have presented with multiple signs and symptoms and encourage clinicians to consider the full list of common presenting signs and symptoms and their prevalence to aid in EOCRC risk assessment.

This systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining sign and symptom presentation of EOCRC found that hematochezia, abdominal pain, altered bowel habits, and unexplained weight loss were the most common presenting signs and symptoms in patients diagnosed with EOCRC. Markedly increased EOCRC risk was seen in adults with hematochezia and abdominal pain. Furthermore, time from sign or symptom presentation to EOCRC diagnosis was often between 4 and 6 months. These findings and the increasing risk of CRC in individuals younger than 50 years highlight the urgent need to educate clinicians and patients about these signs and symptoms to ensure that diagnostic workup and resolution are not delayed. Adapting current clinical practice to identify and address these signs and symptoms through careful clinical triage and follow-up could help limit morbidity and mortality associated with EOCRC.

Accepted for Publication: March 19, 2024.

Published: May 24, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.13157

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2024 Demb J et al. JAMA Network Open .

Corresponding Author: Joshua Demb, PhD, MPH, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, 3350 La Jolla Village Dr, Bldg 13, San Diego, CA 92126 ( [email protected] ).

Author Contributions: Drs Demb and Kolb had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs Demb and Kolb are co–first authors.

Concept and design: Demb, Kolb, Fritz, Advani, Cao, Dwyer, Heskett, Lieu, Singh, Vuik, Gupta.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Demb, Kolb, Dounel, Fritz, Cao, Coppernoll-Blach, Perea, Heskett, Holowatyj, Lieu, Singh, Spaander, Gupta.

Drafting of the manuscript: Demb, Kolb, Dounel, Fritz, Advani, Dwyer, Heskett, Lieu.

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Demb, Singh.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Dwyer, Heskett, Gupta.

Supervision: Demb, Kolb, Advani, Perea, Spaander, Gupta.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Holowatyj reported receiving grants from National Institutes of Health, American Cancer Society, Pfizer, Dalton Family Foundation, and ACPMP Research Foundation and personal fees from MJH Life Sciences outside the submitted work. Dr Gupta reported receiving personal fees from Guardant Health, Universal Diagnostics, Geneoscopy, and InterVenn Biosciences and owning stock in CellMax Life outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 2 .

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Adaptive clinical trials in surgery: A scoping review of methodological and reporting quality

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Division of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Department of Surgery, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, Department of Health Research Methodology, Evidence, and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Division of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Department of Surgery, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, McGill University School of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Health Research Methodology, Evidence, and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, Division of General Surgery, Department of Surgery, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Health Research Methodology, Evidence, and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Division of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Department of Surgery, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Division of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Department of Surgery, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Endocrine Surgery Section Head, Division of General Surgery, Department of Surgery, University Health Network, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Roles Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Roles Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Health Research Methodology, Evidence, and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, Division of Orthopedic Surgery, Department of Surgery, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

- Phillip Staibano,

- Emily Oulousian,

- Tyler McKechnie,

- Alex Thabane,

- Samuel Luo,

- Michael K. Gupta,

- Han Zhang,

- Jesse D. Pasternak,

- Michael Au,

- Published: May 28, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299494

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Adaptive surgical trials are scarce, but adopting these methods may help elevate the quality of surgical research when large-scale RCTs are impractical.

Randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard for evidence-based healthcare. Despite an increase in the number of RCTs, the number of surgical trials remains unchanged. Adaptive clinical trials can streamline trial design and time to trial reporting. The advantages identified for ACTs may help to improve the quality of future surgical trials. We present a scoping review of the methodological and reporting quality of adaptive surgical trials.

Evidence review

We performed a search of Ovid, Web of Science, and Cochrane Collaboration for all adaptive surgical RCTs performed from database inception to October 12, 2023. We included any published trials that had at least one surgical arm. All review and abstraction were performed in duplicate. Risk of bias (RoB) was assessed using the RoB 2.0 instrument and reporting quality was evaluated using CONSORT ACE 2020. All results were analyzed using descriptive methods.

Of the 1338 studies identified, six trials met inclusion criteria. Trials were performed in cardiothoracic, oral, orthopedic, and urological surgery. The most common type of adaptive trial was group sequential design with pre-specified interim analyses planned for efficacy, futility, and/or sample size re-estimation. Two trials did use statistical simulations. Our risk of bias evaluation identified a high risk of bias in 50% of included trials. Reporting quality was heterogeneous regarding trial design and outcome assessment and details in relation to randomization and blinding concealment.

Conclusion and relevance

Surgical trialists should consider implementing adaptive components to help improve patient recruitment and reduce trial duration. Reporting of future adaptive trials must adhere to existing CONSORT ACE 2020 guidelines. Future research is needed to optimize standardization of adaptive methods across medicine and surgery.

Citation: Staibano P, Oulousian E, McKechnie T, Thabane A, Luo S, Gupta MK, et al. (2024) Adaptive clinical trials in surgery: A scoping review of methodological and reporting quality. PLoS ONE 19(5): e0299494. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299494

Editor: Frances Chung, University of Toronto, CANADA

Received: December 27, 2023; Accepted: February 11, 2024; Published: May 28, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Staibano et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are available on OSF: 10.17605/OSF.IO/2GDC5 .

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) are essential for evaluating the effectiveness and safety of interventions in healthcare [ 1 ]. Their importance is reflected in the literature: since 1965, over 39,000 RCTs have been published globally, with over 60% published in the last 20 years [ 2 ]. In 2003, however, only 3.4% of studies published in leading journals were surgical RCTs [ 3 ]. Despite a 50% increase in the number of published surgical trials between 1999 and 2009, this number has remained stable over the past decade [ 4 ]. Surgical trials suffer from a high rate of discontinuation and nonpublication rates often due to slow patient recruitment [ 5 ]. A systematic review of surgical trials published from 2008 to 2020 highlighted several methodological concerns with surgical RCTs, including small sample sizes, a focus on minor clinical outcomes, moderate-to-high bias, and inconsistent usage of blinding and expertise-based randomization [ 3 , 6 ].

In medicine, at least 50% of adopted interventions are derived from RCTs, yet fewer than 25% of surgical interventions are based on evidence derived from RCTs [ 3 ]. Adherence to clinical trial methodological standards in surgery is often impacted by high costs, feasibility issues, between-group crossover, and poor patient adherence [ 7 , 8 ]. As a consequence, many surgical innovations have been adopted based upon non-scientific practices and small-scale, poorly controlled observational studies [ 6 ]. Randomized studies in surgery, however, have historically led to an effective discarding of unnecessary surgical procedures [ 9 ].

The conventional randomized trial design with a large sample size remains the gold-standard approach for comparing medical interventions. Classically, RCTs adhere to a fixed study protocol and culminate in a pre-defined final analysis. Adaptive clinical trials, however, involve flexible adjustments to the study protocol based upon pre-specified interim analyses, which can permit sample size re-calculations, adding or dropping treatment arms, and/or stopping the trial for futility or lack of efficacy ( Table 1 ). Adaptive trials are gaining popularity in drug development and other medical disciplines, as demonstrated by the TAILoR, 18-F PET, and STAMPEDE trials [ 10 – 12 ]. Benefits of trial adaptability include cost reduction, decreased probability of assigning patients to an ineffective treatment arm, and expedited trial completion [ 13 ]. Adaptive trials were useful during the peak of COVID-19 to accelerate the comparison of anti-viral therapies [ 14 ]. Adaptive methodology, however, has been less adopted in evidence-based surgery. Given the challenges surgical researchers face in implementing conventional RCTs, adaptive trials may represent a high-quality alternative that allows surgical researchers to retain the benefits of randomization whilst minimizing costs and permitting protocol adjustments to maximize trial feasibility, adherence, and validity. The goal of this study was to perform a scoping review to characterize the methodological and reporting quality of adaptive study designs in surgical trials. These findings will define the current landscape of adaptive surgical trial quality so that they can be optimized and applied to future surgical populations.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299494.t001

Materials and methods

Study design.

We performed a scoping review of all prospective randomized trials that have employed adaptive designs within any surgical discipline. Surgical disciplines for the purposes of this study included cardiothoracic surgery, general surgery, gynecological surgery, orthopedic surgery, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, neurosurgery, plastic surgery, and urological surgery. We included all studies that compared at least one surgical arm. We also included studies that compared at least one surgical arm to a non-surgical interventional procedure. We registered this review in Open Science Framework (DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/2GDC5 ). Due to the nature of this study, institutional review board (IRB) approval was not required. This review was performed in accordance with PRISMA Scoping Review guidelines [ 15 ].

Search strategy

We performed a library citation search of Medline (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), Web of Science, Cochrane Collaboration, and CENTRAL databases from inception to October 14th, 2023 ( S1 File ). The search strategy was finalized by a librarian specialist. We performed a search of pre-print databases to identify any relevant drafted manuscripts or ongoing clinical trials. We also performed a search of clinicaltrials.gov using the keywords “adaptive/Bayesian”, “clinical trial/trial”, and “surgery/surgical” to evaluate for any active surgical trials meeting our eligibility criteria. We also used keywords for each included surgical discipline. We screened the first 10 pages of relevant results of clinicaltrials.gov and pre-publication databases. Additional studies were identified through reference list searches of included articles. All duplicates were removed, and citations were managed using Covidence software (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) [ 16 ].

Study selection

Any adaptive trial investigating one or more surgical or procedural interventions was included. Eligible trials must have included one of the following adaptive designs: Bayesian, frequentist, sample re-estimation, group sequential, multi-arm multi-stage (MAMS), seamless, continual reassessment, population enrichment, adaptive randomization, and/or adaptive dose-ranging. Any protocols for adaptive surgical trials were collated for the discussion, but not included in the final article synthesis. We excluded any trials that did not include at least one surgical arm, as well as any trials evaluating perioperative medications or non-surgical interventions provided in a surgical setting. Abstracts and conference proceedings, non-human studies, and non-English publications were also excluded.

Outcomes of interest and data abstraction

The primary outcome of this study was to characterize the existing adaptive surgical trial literature and assess the methodological and reporting quality. All identified citations underwent screening of titles and abstracts in duplicate (E.O. and S.L.), followed by full-text evaluation in duplicate (P.S. and E.O.). With the use of a standardised and piloted data abstraction template, the following study characteristics were extracted: publication year, country of study, study design, and methodological details pertaining to adaptive design. We used CONSORT ACE 2020 to guide data abstraction and identified the following adaptive trial characteristics: type of adaptive design, number and type of pre-determined interim analyses, goals of interim analysis, presence of any statistical simulations, and details related to randomization, blinding, type I error adjustments, and final statistical analysis [ 17 ]. All data abstraction was performed in duplicate (E.O. and S.L.) and any conflicts resolved by third reviewer (P.S.).

Quality appraisal

For all studies meeting eligibility criteria, we performed quality appraisal using the Cochrane Risk-of-Bias for Randomized Trials (RoB 2.0) instrument [ 18 ]. We also performed a reporting quality appraisal using the CONSORT ACE 2020 guidelines for adaptive trials [ 17 ]. The author checklist was applied to the abstract and main text for all included articles. We categorized quality of reporting into fully reported , partially reported (with details provided , where relevant) , and not reported . All quality appraisal was performed in duplicate (E.O. and S.L.). All conflicts were resolved via discussion and a third reviewer (P.S.).

Statistical analysis

We performed descriptive statistical analysis for all included studies. We reported all continuous outcomes as means (with standard deviation) or median (with ranges), where applicable. All categorical outcomes were reported as proportions and percentages, where applicable. All analyses were performed in Microsoft Excel (Redmond, Washington, USA).

Search strategy and article selection

Our database search yielded 1338 results from database inception to October 2023, of which, six published trials met eligibility criteria (i.e., <0.5% of retrieved citations) ( Fig 1 ) [ 19 – 24 ]. Our review of clinicaltrials.gov yielded 263 active trials, but none met the eligibility criteria. Our review of pre-publication databases did not yield any manuscripts that met eligibility criteria.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299494.g001

Study characteristics

All six included studies were published after 2015 ( Table 2 ) [ 19 – 24 ]. They were in the fields of cardiothoracic surgery, orthopedics, urology, and oral and maxillofacial surgery. Five studies published their study protocol in advance of trial registration [ 19 – 23 ]. All studies compared two treatment arms. Two trials were conducted in the US (33.3%), one in Japan (16.7%), and three in Europe (50%). Two trials were multi-institutional [ 21 , 23 ]. The total number of recruited patients was 2980 and the range of patient recruitment was 30–1746 patients. We also note that three trials recruited under 150 patients [ 20 – 22 ]. All studies utilized at least one surgical treatment arm. One cardiothoracic surgery trial utilized an interventional procedure as an experimental arm [ 23 ]. All studies utilized 1:1 randomization, and blinding included a combination of patients, outcome assessors, and/or surgeons. These studies did not report an expertise-based group allocation design. Primary outcomes in five trials clinical endpoints of direct patient relevance [ 19 – 23 ]. In the five studies that reported secondary outcomes, the majority were further clinical endpoints with two studies evaluating patient-centred outcomes, and one performing a global economic analysis. The study follow-up range for all trials was 1–24 months with most studies using a 6–12-month study follow-up period. All study data is included in S2 File .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299494.t002

Adaptive methodology characteristics

All included studies were prospective adaptive RCTs ( Table 3 ). One study specified a non-inferiority design [ 23 ]. Two studies employed adaptive randomization [ 20 , 24 ]. Mastroianni et al. (2021) utilized covariate adaptive randomization and identified their pre-specified prognostic strata in their methods [ 20 ]. Yoshioka et al. (2018) did not describe their adaptive randomization methods [ 24 ]. Metcalfe et al. (2022) and Reardon et al. (2017) mentioned the role of statistical simulations in informing their trial design and analysis plan [ 21 , 23 ]. Four studies described their proposed statistical analysis plan, including the type of group allocation analysis and the relevant inferential testing methods. Reardon et al. (2017) was the only study to employ a Bayesian method for trial design and analysis, and this group also used a statistical consulting firm to assist with calculations [ 23 ]. Three studies described a group-sequential design with two treatment arms alongside sample size re-estimation performed at each interim analysis. Four studies also described their adaptive methodologies, including the number and goal(s) of their interim analyses [ 19 , 21 – 23 ]. These interim analyses were all pre-specified and performed for the purpose of study termination for futility or efficacy, and/or sample size re-estimation. In two studies, the sample size was increased at the interim analysis [ 19 , 22 ]. Two studies utilized two pre-specified interim analyses [ 19 , 21 ]. Gaudino et al. (2021) reported a sample size increase at the second interim analysis due to a lower-than-expected primary outcome event rate [ 19 ]. Metcalfe et al. (2022) stopped further randomization due to futility criteria being met [ 21 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299494.t003

Risk of bias and CONSORT reporting

All trials were evaluated by two independent reviewers in duplicate using the Cochrane RoB 2.0 instrument ( Fig 2 ). Overall, three (50%) trials had a low risk of bias and three (50%) had a high risk of bias. A high risk of bias was primarily derived from the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, and the reporting of outcomes [ 20 , 23 , 24 ]. We also performed an assessment of reporting quality using the CONSORT extension ACE checklist [ 17 ]. Two studies directly referenced CONSORT ACE 2020 guidelines [ 20 , 22 ]. Most studies (83.3%) reported trial registration, protocol, full statistical analysis plan, and funding sources. We described abstract and main text reporting outcomes for all included studies ( S1 Table ; S3 File ). Despite other studies adequately reporting details for rationale, methods, and results, one study reported adaptive design details within their abstract [ 21 ]. We found that within the methods section of the main text, most reporting heterogeneity (i.e., 50–83.3% of studies describing either partial or no reporting) occurred when describing design changes following trial initiation, changes to study design after the start of the trial, and details regarding blinding implementation and adherence ( Fig 3 ). In the results section, no studies reported the reasons for trial stoppage or sufficient details surrounding this decision, and there was heterogeneity in the quality of outcome reporting. Lastly, regarding the discussion, we found that findings were adequately contextualized, but only two studies fully reported study limitations with direct reference to adaptive design decisions [ 21 , 22 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299494.g002

Green = Fully reported; Yellow = Partially reported; Red = Not reported.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299494.g003

We present the first scoping review of adaptive clinical trials in surgery. Since 2015, six adaptive trials have been published comparing at least one surgical intervention, which only represents 0.5% of the database search. We also note that three trials recruited under 150 patients. Adaptive methodologies are increasingly being adopted in non-surgical trials, but their design remains nebulous and as such, they have seldom been applied to surgical populations [ 13 ].

Adaptive randomization methods represent an early adaptive method applied to trial design in medicine [ 25 , 26 ]. Response-adaptive randomization can minimize the number of patients randomized to an inferior treatment arm and may suit multi-arm trials or trials with prolonged recruitment and moderately delayed responses,[ 27 , 28 ]. This method of randomization may improve surgical trial recruitment and ethicality, as patients will have an increased probability of being randomized to an effective surgical arm [ 28 ]. Sirkis et al. (2022) simulated adaptive randomization techniques in the RECOVERY trial demonstrating that adaptive approaches may have reduced death and increased the likelihood of randomization to effective COVID-19 therapies [ 29 ]. Adaptive randomization has the potential, however, to optimize patient recruitment in surgical trials, but must be used prudently, as surgical trials are often small-to-moderate in size and therefore prone to prognostic imbalances. A priori trial simulation studies to guide sample size calculations and evaluate optimal adaptive randomization methods and their biases may further inform adaptive designs for surgical trials.

Outside of adaptive randomization alone, we found that three studies employed a group sequential design with blinded sample size re-estimation performed at one or two prespecified interim analyses [ 19 , 21 , 22 ]. A recent systematic review identified 27 adaptive trials that utilized sample size re-estimation, in particular, this design was used in Phase I/II trials wherein there was insufficient prior knowledge of treatment group [ 30 ]. Sample size re-estimation, however, can lead to an inflated type I error rate, and though methods for optimizing these statistical adaptations exist, they remain poorly standardized within the adaptive trial literature [ 31 ]. Group sequential trial designs are defined by at least one interim analysis being built into the trial design to evaluate efficacy and/or futility of treatment arms and can facilitate the adding or dropping of additional treatment arms [ 32 ]. Sequential designs have been used in pharmaceutical trials for decades, and more recently were employed in the DEVELOP-UK trial evaluating lung perfusion following lung transplantation [ 32 , 33 ]. Two studies in this review reported that statistical simulations were performed to guide design and interim analyses [ 21 , 23 ]. Statistical simulations represent another advantage of adaptive trials, as they can estimate efficiency gains and facilitate trial improvements prior to funding expenditure and beginning patient recruitment [ 34 ]. Reardon et al. (2017) utilized a Bayesian analysis plan to design and perform analysis within their trial [ 23 ]. Though statistically more complicated, Bayesian-designed trials hold promise in comparative effectiveness trials wherein prior population knowledge is lacking, as these designs can assist sample size estimations, improve power, and potentially increase the rate at which patients are randomized to effective treatments [ 35 ]. Current barriers to adaptive trial adoption amongst stakeholders, however, include patient consent, risks for bias, type I error rate, lack of clear rationale, and a paucity of education about adaptive methodologies [ 36 ].

Interestingly, combining adaptive methods such as sample size re-estimation couched within a response-adaptive RCT, may also prove helpful as the synergized application of these methods can further improve power and shorten trial duration [ 37 ]. Reardon et al. (2017) reported that an independent statistical group assisted with their analysis [ 23 ]. Better adoption of complex adaptive trial methodologies amongst surgeons will need to occur alongside improved biostatistical training for surgeons and increased collaboration with statisticians [ 38 , 39 ]. Moreover, it is not difficult to conceptualize the interaction that can exist between generative artificial intelligence and the computations that underly adaptive trial design and execution [ 40 ].

We performed a quality appraisal using the Cochrane Rob 2.0 instrument for RCTs [ 18 ]. We were unable to identify a quality appraisal tool tailored to adaptive trial methodologies, but our research group is currently in the process of creating a customized adaptive trial RoB instrument. Our quality appraisal identified 50% of the included trials to have a high risk of bias, which was primarily derived from randomization details and inadequate outcome reporting. We used the CONSORT ACE 2020 guidelines to assess reporting quality in all included trials [ 17 ]. Within the main text, heterogenous reporting was primarily identified in the description of trial design, changes following the start of the trial, and details regarding blinding and concealment maintenance. These deficiencies are important to highlight, as adherence to pre-specified trial design parameters and interim analyses are critical in minimizing type I error rate and bias within adaptive methodologies. It will be important for future adaptive trials to adhere to the published CONSORT ACE 2020 guidelines. Our study limitations are the exclusion of any abstracts or grey literature, and despite liberal search criteria, the risk of missing any relevant surgical trials.

Surgical subspecialties are beginning to explore the role for adaptive trials in their respective disciplines [ 41 , 42 ]. As we peer into the future of evidence-based surgery, we must identify the existing barriers to adoption and global dissemination of surgical trial design and implementation. For instance, our group is currently exploring the importance of pilot trials in surgery to overcome issues of early trial termination [ 5 , 43 ]. As researchers characterize the importance of creativity in surgical innovation, we posit that adaptive trial methodologies provide yet another methodological tool to answer translational questions and advance evidence-based surgical knowledge [ 44 ]. Since conventional RCTs are often conducted out of high-income countries, cost-effective and efficient adaptive methodologies may facilitate practice-changing trials being conducted in low-middle income countries, thereby improving global collaboration and conclusion generalizability [ 45 ].

Adaptive designs have the potential to optimize patient recruitment and statistical power when sample sizes are small, or little is known about the research populations under investigation: common issues encountered in surgical trials [ 46 ]. These designs may also assist with conducting trials in rare disease populations [ 47 ]. Like any technological advancement, however, it is imperative that we always identify the appropriate research question and clinical scenario where adaptive methodologies can be best deployed, as they are not without their shortcomings [ 48 ]. For instance, adaptive trials are likely not best suited when there is a notable delay in outcome assessment or there is inadequate trial infrastructure at the primary institution. An adaptive design is, however, likely best suited when the gain in trial efficiency and cost-effectiveness greatly outweighs the added complexity to trial methodology and statistical analysis [ 48 ]. Here, we demonstrate that the number of published adaptive surgical trials is low and reporting of complex adaptive methods is often heterogenous and inadequate. Future adaptive trials must be reported in accordance with published CONSORT ACE 2020 guidelines [ 17 ]. As these methodologies continue to be optimized, we suggest that surgical trialists consider implementing adaptive design components when deemed appropriate for their clinical question and population-of-interest. Adaptive trial designs may help to improve the quality of surgical evidence, streamline time to reporting, and compliment the accelerated pace of innovation in surgery.

Supporting information

S1 file. ovid search algorithm..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299494.s001

S2 File. Raw data for all included trials.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299494.s002

S3 File. Raw data for CONSORT ACE 2020 evaluation.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299494.s003

S1 Table. CONSORT ACE 2020 assessment for included studies.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299494.s004

S1 Checklist. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299494.s005

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Knowledge, attitude, and perception regarding generic medicine prescription among dental and medical professionals - A systematic review. Journal of Oral Research and Review. 15 (2):161-170, Jul-Dec 2023.

A peer-reviewed, open access journal in dentistry that publishes original research and reviews. Find out about its aims, scope, editorial board, publication fees, archiving policy and more.