History Cooperative

The Homework Dilemma: Who Invented Homework?

The inventor of homework may be unknown, but its evolution reflects contributions from educators, philosophers, and students. Homework reinforces learning, fosters discipline, and prepares students for the future, spanning from ancient civilizations to modern education. Ongoing debates probe its balance, efficacy, equity, and accessibility, prompting innovative alternatives like project-based and personalized learning. As education evolves, the enigma of homework endures.

Table of Contents

Who Invented Homework?

While historical records don’t provide a definitive answer regarding the inventor of homework in the modern sense, two prominent figures, Roberto Nevelis of Venice and Horace Mann, are often linked to the concept’s early development.

Roberto Nevelis of Venice: A Mythical Innovator?

Roberto Nevelis, a Venetian educator from the 16th century, is frequently credited with the invention of homework. The story goes that Nevelis assigned tasks to his students outside regular classroom hours to reinforce their learning—a practice that aligns with the essence of homework. However, the historical evidence supporting Nevelis as the inventor of homework is rather elusive, leaving room for skepticism.

While Nevelis’s role remains somewhat mythical, his association with homework highlights the early recognition of the concept’s educational value.

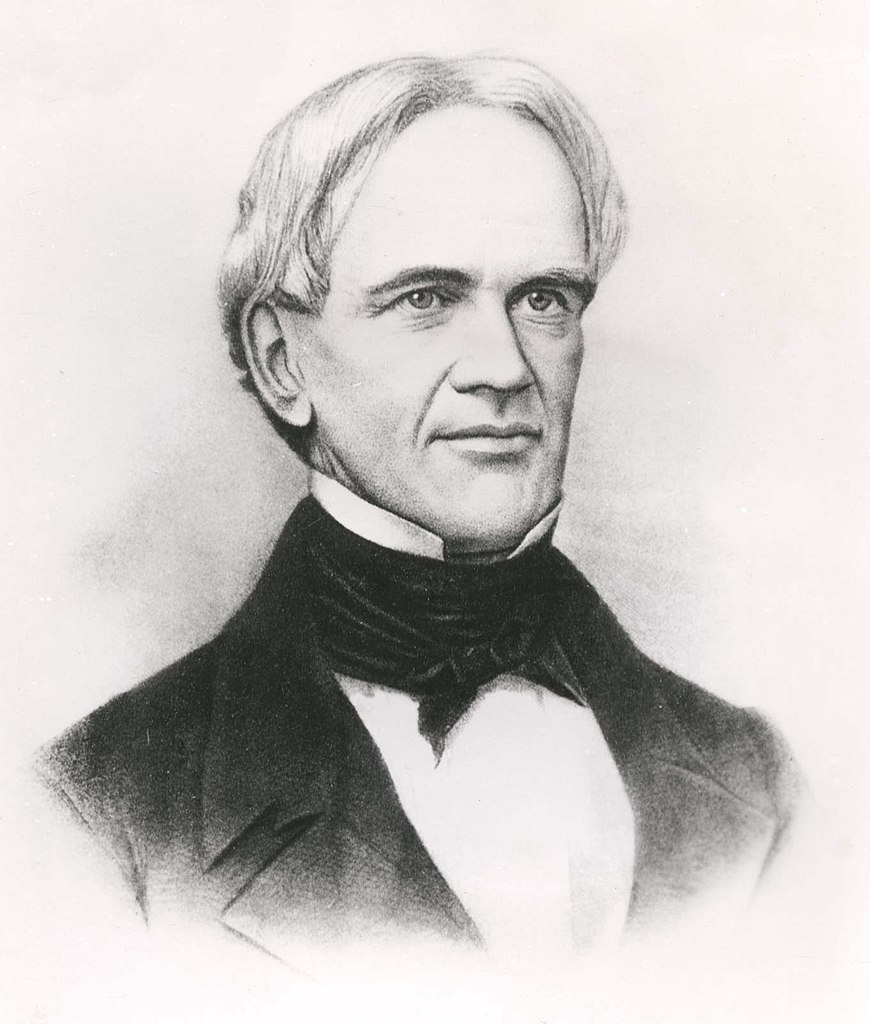

Horace Mann: Shaping the American Educational Landscape

Horace Mann, often regarded as the “Father of American Education,” made significant contributions to the American public school system in the 19th century. Though he may not have single-handedly invented homework, his educational reforms played a crucial role in its widespread adoption.

Mann’s vision for education emphasized discipline and rigor, which included assigning tasks to be completed outside of the classroom. While he did not create homework in the traditional sense, his influence on the American education system paved the way for its integration.

The invention of homework was driven by several educational objectives. It aimed to reinforce classroom learning, ensuring knowledge retention and skill development. Homework also served as a means to promote self-discipline and responsibility among students, fostering valuable study habits and time management skills.

Why Was Homework Invented?

The invention of homework was not a random educational practice but rather a deliberate strategy with several essential objectives in mind.

Reinforcing Classroom Learning

Foremost among these objectives was the need to reinforce classroom learning. When students leave the classroom, the goal is for them to retain and apply the knowledge they have acquired during their lessons. Homework emerged as a powerful tool for achieving this goal. It provided students with a structured platform to revisit the day’s lessons, practice what they had learned, and solidify their understanding.

Homework assignments often mirrored classroom activities, allowing students to extend their learning beyond the confines of school hours. Through the repetition of exercises and tasks related to the curriculum, students could deepen their comprehension and mastery of various subjects.

Fostering Self-Discipline and Responsibility

Another significant objective behind the creation of homework was the promotion of self-discipline and responsibility among students. Education has always been about more than just the acquisition of knowledge; it also involves the development of life skills and habits that prepare individuals for future challenges.

By assigning tasks to be completed independently at home, educators aimed to instill valuable study habits and time management skills. Students were expected to take ownership of their learning, manage their time effectively, and meet deadlines—a set of skills that have enduring relevance in contemporary education and beyond.

Homework encouraged students to become proactive in their educational journey. It taught them the importance of accountability and the satisfaction of completing tasks on their own. These life skills would prove invaluable in their future endeavors, both academically and in the broader context of their lives.

When Was Homework Invented?

The roots of homework stretch deep into the annals of history, tracing its origins to ancient civilizations and early educational practices. While it has undergone significant evolution over the centuries, the concept of extending learning beyond the classroom has always been an integral part of education.

Earliest Origins of Homework and Early Educational Practices

The idea of homework, in its most rudimentary form, can be traced back to the earliest human civilizations. In ancient Egypt , for instance, students were tasked with hieroglyphic writing exercises. These exercises served as a precursor to modern homework, as they required students to practice and reinforce their understanding of written language—an essential skill for communication and record-keeping in that era.

In ancient Greece , luminaries like Plato and Aristotle advocated for the use of written exercises as a tool for intellectual development. They recognized the value of practice in enhancing one’s knowledge and skills, laying the foundation for a more systematic approach to homework.

The ancient Romans also played a pivotal role in the early development of homework. Young Roman students were expected to complete assignments at home, with a particular focus on subjects like mathematics and literature. These assignments were designed to consolidate their classroom learning, emphasizing the importance of practice in mastering various disciplines.

READ MORE: Who Invented Math? The History of Mathematics

The practice of assigning work to be done outside of regular school hours continued to evolve through various historical periods. As societies advanced, so did the complexity and diversity of homework tasks, reflecting the changing needs and priorities of education.

The Influence of Educational Philosophers

While the roots of homework extend to ancient times, the ideas of renowned educational philosophers in later centuries further contributed to its development. John Locke, an influential thinker of the Enlightenment era, believed in a gradual and cumulative approach to learning. He emphasized the importance of students revisiting topics through repetition and practice, a concept that aligns with the principles of homework.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, another prominent philosopher, stressed the significance of self-directed learning. Rousseau’s ideas encouraged the development of independent study habits and a personalized approach to education—a philosophy that resonates with modern concepts of homework.

Homework in the American Public School System

The American public school system has played a pivotal role in the widespread adoption and popularization of homework. To understand the significance of homework in modern education, it’s essential to delve into its history and evolution within the United States.

History and Evolution of Homework in the United States

The late 19th century marked a significant turning point for homework in the United States. During this period, influenced by educational reforms and the growing need for standardized curricula, homework assignments began to gain prominence in American schools.

Educational reformers and policymakers recognized the value of homework as a tool for reinforcing classroom learning. They believed that assigning tasks for students to complete outside of regular school hours would help ensure that knowledge was retained and skills were honed. This approach aligned with the broader trends in education at the time, which aimed to provide a more structured and systematic approach to learning.

As the American public school system continued to evolve, homework assignments became a common practice in classrooms across the nation. The standardization of curricula and the formalization of education contributed to the integration of homework into the learning process. This marked a significant departure from earlier educational practices, reflecting a shift toward more structured and comprehensive learning experiences.

The incorporation of homework into the American education system not only reinforced classroom learning but also fostered self-discipline and responsibility among students. It encouraged them to take ownership of their educational journey and develop valuable study habits and time management skills—a legacy that continues to influence modern pedagogy.

Controversies Around Homework

Despite its longstanding presence in education, homework has not been immune to controversy and debate. While many view it as a valuable educational tool, others question its effectiveness and impact on students’ well-being.

The Homework Debate

One of the central controversies revolves around the amount of homework assigned to students. Critics argue that excessive homework loads can lead to stress, sleep deprivation, and a lack of free time for students. The debate often centers on striking the right balance between homework and other aspects of a student’s life, including extracurricular activities, family time, and rest.

Homework’s Efficacy

Another contentious issue pertains to the efficacy of homework in enhancing learning outcomes. Some studies suggest that moderate amounts of homework can reinforce classroom learning and improve academic performance. However, others question whether all homework assignments contribute equally to learning or whether some may be more beneficial than others. The effectiveness of homework can vary depending on factors such as the student’s grade level, the subject matter, and the quality of the assignment.

Equity and Accessibility

Homework can also raise concerns related to equity and accessibility. Students from disadvantaged backgrounds may have limited access to resources and support at home, potentially putting them at a disadvantage when it comes to completing homework assignments. This disparity has prompted discussions about the role of homework in perpetuating educational inequalities and how schools can address these disparities.

Alternative Approaches to Learning

In response to the controversies surrounding homework, educators and researchers have explored alternative approaches to learning. These approaches aim to strike a balance between reinforcing classroom learning and promoting holistic student well-being. Some alternatives include:

Project-Based Learning

Project-based learning emphasizes hands-on, collaborative projects that allow students to apply their knowledge to real-world problems. This approach shifts the focus from traditional homework assignments to engaging, practical learning experiences.

Flipped Classrooms

Flipped classrooms reverse the traditional teaching model. Students learn new material at home through video lectures or readings and then use class time for interactive discussions and activities. This approach reduces the need for traditional homework while promoting active learning.

Personalized Learning

Personalized learning tailors instruction to individual students’ needs, allowing them to progress at their own pace. This approach minimizes the need for one-size-fits-all homework assignments and instead focuses on targeted learning experiences.

The Ongoing Conversation

The controversies surrounding homework highlight the need for an ongoing conversation about its role in education. Striking the right balance between reinforcing learning and addressing students’ well-being remains a complex challenge. As educators, parents, and researchers continue to explore innovative approaches to learning, the role of homework in the modern educational landscape continues to evolve. Ultimately, the goal is to provide students with the most effective and equitable learning experiences possible.

Unpacking the Homework Enigma

Homework, without a single inventor, has evolved through educators, philosophers, and students. It reinforces learning, fosters discipline and prepares students. From ancient times to modern education, it upholds timeless values. Yet, controversies arise—debates on balance, efficacy, equity, and accessibility persist. Innovative alternatives like project-based and personalized learning emerge. Homework’s role evolves with education.

How to Cite this Article

There are three different ways you can cite this article.

1. To cite this article in an academic-style article or paper , use:

<a href=" https://historycooperative.org/who-invented-homework/ ">The Homework Dilemma: Who Invented Homework?</a>

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

The Surprising History of Homework Reform

Really, kids, there was a time when lots of grownups thought homework was bad for you.

Homework causes a lot of fights. Between parents and kids, sure. But also, as education scholar Brian Gill and historian Steven Schlossman write, among U.S. educators. For more than a century, they’ve been debating how, and whether, kids should do schoolwork at home .

At the dawn of the twentieth century, homework meant memorizing lists of facts which could then be recited to the teacher the next day. The rising progressive education movement despised that approach. These educators advocated classrooms free from recitation. Instead, they wanted students to learn by doing. To most, homework had no place in this sort of system.

Through the middle of the century, Gill and Schlossman write, this seemed like common sense to most progressives. And they got their way in many schools—at least at the elementary level. Many districts abolished homework for K–6 classes, and almost all of them eliminated it for students below fourth grade.

By the 1950s, many educators roundly condemned drills, like practicing spelling words and arithmetic problems. In 1963, Helen Heffernan, chief of California’s Bureau of Elementary Education, definitively stated that “No teacher aware of recent theories could advocate such meaningless homework assignments as pages of repetitive computation in arithmetic. Such an assignment not only kills time but kills the child’s creative urge to intellectual activity.”

But, the authors note, not all reformers wanted to eliminate homework entirely. Some educators reconfigured the concept, suggesting supplemental reading or having students do projects based in their own interests. One teacher proposed “homework” consisting of after-school “field trips to the woods, factories, museums, libraries, art galleries.” In 1937, Carleton Washburne, an influential educator who was the superintendent of the Winnetka, Illinois, schools, proposed a homework regimen of “cooking and sewing…meal planning…budgeting, home repairs, interior decorating, and family relationships.”

Another reformer explained that “at first homework had as its purpose one thing—to prepare the next day’s lessons. Its purpose now is to prepare the children for fuller living through a new type of creative and recreational homework.”

That idea didn’t necessarily appeal to all educators. But moderation in the use of traditional homework became the norm.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

“Virtually all commentators on homework in the postwar years would have agreed with the sentiment expressed in the NEA Journal in 1952 that ‘it would be absurd to demand homework in the first grade or to denounce it as useless in the eighth grade and in high school,’” Gill and Schlossman write.

That remained more or less true until 1983, when publication of the landmark government report A Nation at Risk helped jump-start a conservative “back to basics” agenda, including an emphasis on drill-style homework. In the decades since, continuing “reforms” like high-stakes testing, the No Child Left Behind Act, and the Common Core standards have kept pressure on schools. Which is why twenty-first-century first graders get spelling words and pages of arithmetic.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

Scaffolding a Research Project with JSTOR

Making Implicit Racism

The Diverse Shamanisms of South America

Doing Some (Catfish) Noodling?

Recent posts.

- Medieval Whalers, Smart Plants, and Space Mines

- Arakawa and Gins: An Eternal Architecture

- Zheng He, the Great Eunuch Admiral

- The Dangers of Animal Experimentation—for Doctors

- Fredric Wertham, Cartoon Villain

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Does homework really work?

by: Leslie Crawford | Updated: December 12, 2023

Print article

You know the drill. It’s 10:15 p.m., and the cardboard-and-toothpick Golden Gate Bridge is collapsing. The pages of polynomials have been abandoned. The paper on the Battle of Waterloo seems to have frozen in time with Napoleon lingering eternally over his breakfast at Le Caillou. Then come the tears and tantrums — while we parents wonder, Does the gain merit all this pain? Is this just too much homework?

However the drama unfolds night after night, year after year, most parents hold on to the hope that homework (after soccer games, dinner, flute practice, and, oh yes, that childhood pastime of yore known as playing) advances their children academically.

But what does homework really do for kids? Is the forest’s worth of book reports and math and spelling sheets the average American student completes in their 12 years of primary schooling making a difference? Or is it just busywork?

Homework haterz

Whether or not homework helps, or even hurts, depends on who you ask. If you ask my 12-year-old son, Sam, he’ll say, “Homework doesn’t help anything. It makes kids stressed-out and tired and makes them hate school more.”

Nothing more than common kid bellyaching?

Maybe, but in the fractious field of homework studies, it’s worth noting that Sam’s sentiments nicely synopsize one side of the ivory tower debate. Books like The End of Homework , The Homework Myth , and The Case Against Homework the film Race to Nowhere , and the anguished parent essay “ My Daughter’s Homework is Killing Me ” make the case that homework, by taking away precious family time and putting kids under unneeded pressure, is an ineffective way to help children become better learners and thinkers.

One Canadian couple took their homework apostasy all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada. After arguing that there was no evidence that it improved academic performance, they won a ruling that exempted their two children from all homework.

So what’s the real relationship between homework and academic achievement?

How much is too much?

To answer this question, researchers have been doing their homework on homework, conducting and examining hundreds of studies. Chris Drew Ph.D., founder and editor at The Helpful Professor recently compiled multiple statistics revealing the folly of today’s after-school busy work. Does any of the data he listed below ring true for you?

• 45 percent of parents think homework is too easy for their child, primarily because it is geared to the lowest standard under the Common Core State Standards .

• 74 percent of students say homework is a source of stress , defined as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss, and stomach problems.

• Students in high-performing high schools spend an average of 3.1 hours a night on homework , even though 1 to 2 hours is the optimal duration, according to a peer-reviewed study .

Not included in the list above is the fact many kids have to abandon activities they love — like sports and clubs — because homework deprives them of the needed time to enjoy themselves with other pursuits.

Conversely, The Helpful Professor does list a few pros of homework, noting it teaches discipline and time management, and helps parents know what’s being taught in the class.

The oft-bandied rule on homework quantity — 10 minutes a night per grade (starting from between 10 to 20 minutes in first grade) — is listed on the National Education Association’s website and the National Parent Teacher Association’s website , but few schools follow this rule.

Do you think your child is doing excessive homework? Harris Cooper Ph.D., author of a meta-study on homework , recommends talking with the teacher. “Often there is a miscommunication about the goals of homework assignments,” he says. “What appears to be problematic for kids, why they are doing an assignment, can be cleared up with a conversation.” Also, Cooper suggests taking a careful look at how your child is doing the assignments. It may seem like they’re taking two hours, but maybe your child is wandering off frequently to get a snack or getting distracted.

Less is often more

If your child is dutifully doing their work but still burning the midnight oil, it’s worth intervening to make sure your child gets enough sleep. A 2012 study of 535 high school students found that proper sleep may be far more essential to brain and body development.

For elementary school-age children, Cooper’s research at Duke University shows there is no measurable academic advantage to homework. For middle-schoolers, Cooper found there is a direct correlation between homework and achievement if assignments last between one to two hours per night. After two hours, however, achievement doesn’t improve. For high schoolers, Cooper’s research suggests that two hours per night is optimal. If teens have more than two hours of homework a night, their academic success flatlines. But less is not better. The average high school student doing homework outperformed 69 percent of the students in a class with no homework.

Many schools are starting to act on this research. A Florida superintendent abolished homework in her 42,000 student district, replacing it with 20 minutes of nightly reading. She attributed her decision to “ solid research about what works best in improving academic achievement in students .”

More family time

A 2020 survey by Crayola Experience reports 82 percent of children complain they don’t have enough quality time with their parents. Homework deserves much of the blame. “Kids should have a chance to just be kids and do things they enjoy, particularly after spending six hours a day in school,” says Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth . “It’s absurd to insist that children must be engaged in constructive activities right up until their heads hit the pillow.”

By far, the best replacement for homework — for both parents and children — is bonding, relaxing time together.

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

How families of color can fight for fair discipline in school

Dealing with teacher bias

The most important school data families of color need to consider

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/71970990/05_nohomework_Jiayue_Li.0.jpg)

Filed under:

- The Highlight

Nobody knows what the point of homework is

The homework wars are back.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Nobody knows what the point of homework is

As the Covid-19 pandemic began and students logged into their remote classrooms, all work, in effect, became homework. But whether or not students could complete it at home varied. For some, schoolwork became public-library work or McDonald’s-parking-lot work.

Luis Torres, the principal of PS 55, a predominantly low-income community elementary school in the south Bronx, told me that his school secured Chromebooks for students early in the pandemic only to learn that some lived in shelters that blocked wifi for security reasons. Others, who lived in housing projects with poor internet reception, did their schoolwork in laundromats.

According to a 2021 Pew survey , 25 percent of lower-income parents said their children, at some point, were unable to complete their schoolwork because they couldn’t access a computer at home; that number for upper-income parents was 2 percent.

The issues with remote learning in March 2020 were new. But they highlighted a divide that had been there all along in another form: homework. And even long after schools have resumed in-person classes, the pandemic’s effects on homework have lingered.

Over the past three years, in response to concerns about equity, schools across the country, including in Sacramento, Los Angeles , San Diego , and Clark County, Nevada , made permanent changes to their homework policies that restricted how much homework could be given and how it could be graded after in-person learning resumed.

Three years into the pandemic, as districts and teachers reckon with Covid-era overhauls of teaching and learning, schools are still reconsidering the purpose and place of homework. Whether relaxing homework expectations helps level the playing field between students or harms them by decreasing rigor is a divisive issue without conclusive evidence on either side, echoing other debates in education like the elimination of standardized test scores from some colleges’ admissions processes.

I first began to wonder if the homework abolition movement made sense after speaking with teachers in some Massachusetts public schools, who argued that rather than help disadvantaged kids, stringent homework restrictions communicated an attitude of low expectations. One, an English teacher, said she felt the school had “just given up” on trying to get the students to do work; another argued that restrictions that prohibit teachers from assigning take-home work that doesn’t begin in class made it difficult to get through the foreign-language curriculum. Teachers in other districts have raised formal concerns about homework abolition’s ability to close gaps among students rather than widening them.

Many education experts share this view. Harris Cooper, a professor emeritus of psychology at Duke who has studied homework efficacy, likened homework abolition to “playing to the lowest common denominator.”

But as I learned after talking to a variety of stakeholders — from homework researchers to policymakers to parents of schoolchildren — whether to abolish homework probably isn’t the right question. More important is what kind of work students are sent home with and where they can complete it. Chances are, if schools think more deeply about giving constructive work, time spent on homework will come down regardless.

There’s no consensus on whether homework works

The rise of the no-homework movement during the Covid-19 pandemic tapped into long-running disagreements over homework’s impact on students. The purpose and effectiveness of homework have been disputed for well over a century. In 1901, for instance, California banned homework for students up to age 15, and limited it for older students, over concerns that it endangered children’s mental and physical health. The newest iteration of the anti-homework argument contends that the current practice punishes students who lack support and rewards those with more resources, reinforcing the “myth of meritocracy.”

But there is still no research consensus on homework’s effectiveness; no one can seem to agree on what the right metrics are. Much of the debate relies on anecdotes, intuition, or speculation.

Researchers disagree even on how much research exists on the value of homework. Kathleen Budge, the co-author of Turning High-Poverty Schools Into High-Performing Schools and a professor at Boise State, told me that homework “has been greatly researched.” Denise Pope, a Stanford lecturer and leader of the education nonprofit Challenge Success, said, “It’s not a highly researched area because of some of the methodological problems.”

Experts who are more sympathetic to take-home assignments generally support the “10-minute rule,” a framework that estimates the ideal amount of homework on any given night by multiplying the student’s grade by 10 minutes. (A ninth grader, for example, would have about 90 minutes of work a night.) Homework proponents argue that while it is difficult to design randomized control studies to test homework’s effectiveness, the vast majority of existing studies show a strong positive correlation between homework and high academic achievement for middle and high school students. Prominent critics of homework argue that these correlational studies are unreliable and point to studies that suggest a neutral or negative effect on student performance. Both agree there is little to no evidence for homework’s effectiveness at an elementary school level, though proponents often argue that it builds constructive habits for the future.

For anyone who remembers homework assignments from both good and bad teachers, this fundamental disagreement might not be surprising. Some homework is pointless and frustrating to complete. Every week during my senior year of high school, I had to analyze a poem for English and decorate it with images found on Google; my most distinct memory from that class is receiving a demoralizing 25-point deduction because I failed to present my analysis on a poster board. Other assignments really do help students learn: After making an adapted version of Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book for a ninth grade history project, I was inspired to check out from the library and read a biography of the Chinese ruler.

For homework opponents, the first example is more likely to resonate. “We’re all familiar with the negative effects of homework: stress, exhaustion, family conflict, less time for other activities, diminished interest in learning,” Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth, which challenges common justifications for homework, told me in an email. “And these effects may be most pronounced among low-income students.” Kohn believes that schools should make permanent any moratoria implemented during the pandemic, arguing that there are no positives at all to outweigh homework’s downsides. Recent studies , he argues , show the benefits may not even materialize during high school.

In the Marlborough Public Schools, a suburban district 45 minutes west of Boston, school policy committee chair Katherine Hennessy described getting kids to complete their homework during remote education as “a challenge, to say the least.” Teachers found that students who spent all day on their computers didn’t want to spend more time online when the day was over. So, for a few months, the school relaxed the usual practice and teachers slashed the quantity of nightly homework.

Online learning made the preexisting divides between students more apparent, she said. Many students, even during normal circumstances, lacked resources to keep them on track and focused on completing take-home assignments. Though Marlborough Schools is more affluent than PS 55, Hennessy said many students had parents whose work schedules left them unable to provide homework help in the evenings. The experience tracked with a common divide in the country between children of different socioeconomic backgrounds.

So in October 2021, months after the homework reduction began, the Marlborough committee made a change to the district’s policy. While teachers could still give homework, the assignments had to begin as classwork. And though teachers could acknowledge homework completion in a student’s participation grade, they couldn’t count homework as its own grading category. “Rigorous learning in the classroom does not mean that that classwork must be assigned every night,” the policy stated . “Extensions of class work is not to be used to teach new content or as a form of punishment.”

Canceling homework might not do anything for the achievement gap

The critiques of homework are valid as far as they go, but at a certain point, arguments against homework can defy the commonsense idea that to retain what they’re learning, students need to practice it.

“Doesn’t a kid become a better reader if he reads more? Doesn’t a kid learn his math facts better if he practices them?” said Cathy Vatterott, an education researcher and professor emeritus at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. After decades of research, she said it’s still hard to isolate the value of homework, but that doesn’t mean it should be abandoned.

Blanket vilification of homework can also conflate the unique challenges facing disadvantaged students as compared to affluent ones, which could have different solutions. “The kids in the low-income schools are being hurt because they’re being graded, unfairly, on time they just don’t have to do this stuff,” Pope told me. “And they’re still being held accountable for turning in assignments, whether they’re meaningful or not.” On the other side, “Palo Alto kids” — students in Silicon Valley’s stereotypically pressure-cooker public schools — “are just bombarded and overloaded and trying to stay above water.”

Merely getting rid of homework doesn’t solve either problem. The United States already has the second-highest disparity among OECD (the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) nations between time spent on homework by students of high and low socioeconomic status — a difference of more than three hours, said Janine Bempechat, clinical professor at Boston University and author of No More Mindless Homework .

When she interviewed teachers in Boston-area schools that had cut homework before the pandemic, Bempechat told me, “What they saw immediately was parents who could afford it immediately enrolled their children in the Russian School of Mathematics,” a math-enrichment program whose tuition ranges from $140 to about $400 a month. Getting rid of homework “does nothing for equity; it increases the opportunity gap between wealthier and less wealthy families,” she said. “That solution troubles me because it’s no solution at all.”

A group of teachers at Wakefield High School in Arlington, Virginia, made the same point after the school district proposed an overhaul of its homework policies, including removing penalties for missing homework deadlines, allowing unlimited retakes, and prohibiting grading of homework.

“Given the emphasis on equity in today’s education systems,” they wrote in a letter to the school board, “we believe that some of the proposed changes will actually have a detrimental impact towards achieving this goal. Families that have means could still provide challenging and engaging academic experiences for their children and will continue to do so, especially if their children are not experiencing expected rigor in the classroom.” At a school where more than a third of students are low-income, the teachers argued, the policies would prompt students “to expect the least of themselves in terms of effort, results, and responsibility.”

Not all homework is created equal

Despite their opposing sides in the homework wars, most of the researchers I spoke to made a lot of the same points. Both Bempechat and Pope were quick to bring up how parents and schools confuse rigor with workload, treating the volume of assignments as a proxy for quality of learning. Bempechat, who is known for defending homework, has written extensively about how plenty of it lacks clear purpose, requires the purchasing of unnecessary supplies, and takes longer than it needs to. Likewise, when Pope instructs graduate-level classes on curriculum, she asks her students to think about the larger purpose they’re trying to achieve with homework: If they can get the job done in the classroom, there’s no point in sending home more work.

At its best, pandemic-era teaching facilitated that last approach. Honolulu-based teacher Christina Torres Cawdery told me that, early in the pandemic, she often had a cohort of kids in her classroom for four hours straight, as her school tried to avoid too much commingling. She couldn’t lecture for four hours, so she gave the students plenty of time to complete independent and project-based work. At the end of most school days, she didn’t feel the need to send them home with more to do.

A similar limited-homework philosophy worked at a public middle school in Chelsea, Massachusetts. A couple of teachers there turned as much class as possible into an opportunity for small-group practice, allowing kids to work on problems that traditionally would be assigned for homework, Jessica Flick, a math coach who leads department meetings at the school, told me. It was inspired by a philosophy pioneered by Simon Fraser University professor Peter Liljedahl, whose influential book Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics reframes homework as “check-your-understanding questions” rather than as compulsory work. Last year, Flick found that the two eighth grade classes whose teachers adopted this strategy performed the best on state tests, and this year, she has encouraged other teachers to implement it.

Teachers know that plenty of homework is tedious and unproductive. Jeannemarie Dawson De Quiroz, who has taught for more than 20 years in low-income Boston and Los Angeles pilot and charter schools, says that in her first years on the job she frequently assigned “drill and kill” tasks and questions that she now feels unfairly stumped students. She said designing good homework wasn’t part of her teaching programs, nor was it meaningfully discussed in professional development. With more experience, she turned as much class time as she could into practice time and limited what she sent home.

“The thing about homework that’s sticky is that not all homework is created equal,” says Jill Harrison Berg, a former teacher and the author of Uprooting Instructional Inequity . “Some homework is a genuine waste of time and requires lots of resources for no good reason. And other homework is really useful.”

Cutting homework has to be part of a larger strategy

The takeaways are clear: Schools can make cuts to homework, but those cuts should be part of a strategy to improve the quality of education for all students. If the point of homework was to provide more practice, districts should think about how students can make it up during class — or offer time during or after school for students to seek help from teachers. If it was to move the curriculum along, it’s worth considering whether strategies like Liljedahl’s can get more done in less time.

Some of the best thinking around effective assignments comes from those most critical of the current practice. Denise Pope proposes that, before assigning homework, teachers should consider whether students understand the purpose of the work and whether they can do it without help. If teachers think it’s something that can’t be done in class, they should be mindful of how much time it should take and the feedback they should provide. It’s questions like these that De Quiroz considered before reducing the volume of work she sent home.

More than a year after the new homework policy began in Marlborough, Hennessy still hears from parents who incorrectly “think homework isn’t happening” despite repeated assurances that kids still can receive work. She thinks part of the reason is that education has changed over the years. “I think what we’re trying to do is establish that homework may be an element of educating students,” she told me. “But it may not be what parents think of as what they grew up with. ... It’s going to need to adapt, per the teaching and the curriculum, and how it’s being delivered in each classroom.”

For the policy to work, faculty, parents, and students will all have to buy into a shared vision of what school ought to look like. The district is working on it — in November, it hosted and uploaded to YouTube a round-table discussion on homework between district administrators — but considering the sustained confusion, the path ahead seems difficult.

When I asked Luis Torres about whether he thought homework serves a useful part in PS 55’s curriculum, he said yes, of course it was — despite the effort and money it takes to keep the school open after hours to help them do it. “The children need the opportunity to practice,” he said. “If you don’t give them opportunities to practice what they learn, they’re going to forget.” But Torres doesn’t care if the work is done at home. The school stays open until around 6 pm on weekdays, even during breaks. Tutors through New York City’s Department of Youth and Community Development programs help kids with work after school so they don’t need to take it with them.

As schools weigh the purpose of homework in an unequal world, it’s tempting to dispose of a practice that presents real, practical problems to students across the country. But getting rid of homework is unlikely to do much good on its own. Before cutting it, it’s worth thinking about what good assignments are meant to do in the first place. It’s crucial that students from all socioeconomic backgrounds tackle complex quantitative problems and hone their reading and writing skills. It’s less important that the work comes home with them.

Jacob Sweet is a freelance writer in Somerville, Massachusetts. He is a frequent contributor to the New Yorker, among other publications.

Will you support Vox today?

Millions rely on Vox’s journalism to understand the coronavirus crisis. We believe it pays off for all of us, as a society and a democracy, when our neighbors and fellow citizens can access clear, concise information on the pandemic. But our distinctive explanatory journalism is expensive. Support from our readers helps us keep it free for everyone. If you have already made a financial contribution to Vox, thank you. If not, please consider making a contribution today from as little as $3.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Social media platforms aren’t equipped to handle the negative effects of their algorithms abroad. Neither is the law.

The real science behind the billionaire pursuit of immortality, if you want to belong, find a third place, sign up for the newsletter today, explained, thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Is Homework Good for Kids? Here’s What the Research Says

A s kids return to school, debate is heating up once again over how they should spend their time after they leave the classroom for the day.

The no-homework policy of a second-grade teacher in Texas went viral last week , earning praise from parents across the country who lament the heavy workload often assigned to young students. Brandy Young told parents she would not formally assign any homework this year, asking students instead to eat dinner with their families, play outside and go to bed early.

But the question of how much work children should be doing outside of school remains controversial, and plenty of parents take issue with no-homework policies, worried their kids are losing a potential academic advantage. Here’s what you need to know:

For decades, the homework standard has been a “10-minute rule,” which recommends a daily maximum of 10 minutes of homework per grade level. Second graders, for example, should do about 20 minutes of homework each night. High school seniors should complete about two hours of homework each night. The National PTA and the National Education Association both support that guideline.

But some schools have begun to give their youngest students a break. A Massachusetts elementary school has announced a no-homework pilot program for the coming school year, lengthening the school day by two hours to provide more in-class instruction. “We really want kids to go home at 4 o’clock, tired. We want their brain to be tired,” Kelly Elementary School Principal Jackie Glasheen said in an interview with a local TV station . “We want them to enjoy their families. We want them to go to soccer practice or football practice, and we want them to go to bed. And that’s it.”

A New York City public elementary school implemented a similar policy last year, eliminating traditional homework assignments in favor of family time. The change was quickly met with outrage from some parents, though it earned support from other education leaders.

New solutions and approaches to homework differ by community, and these local debates are complicated by the fact that even education experts disagree about what’s best for kids.

The research

The most comprehensive research on homework to date comes from a 2006 meta-analysis by Duke University psychology professor Harris Cooper, who found evidence of a positive correlation between homework and student achievement, meaning students who did homework performed better in school. The correlation was stronger for older students—in seventh through 12th grade—than for those in younger grades, for whom there was a weak relationship between homework and performance.

Cooper’s analysis focused on how homework impacts academic achievement—test scores, for example. His report noted that homework is also thought to improve study habits, attitudes toward school, self-discipline, inquisitiveness and independent problem solving skills. On the other hand, some studies he examined showed that homework can cause physical and emotional fatigue, fuel negative attitudes about learning and limit leisure time for children. At the end of his analysis, Cooper recommended further study of such potential effects of homework.

Despite the weak correlation between homework and performance for young children, Cooper argues that a small amount of homework is useful for all students. Second-graders should not be doing two hours of homework each night, he said, but they also shouldn’t be doing no homework.

Not all education experts agree entirely with Cooper’s assessment.

Cathy Vatterott, an education professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, supports the “10-minute rule” as a maximum, but she thinks there is not sufficient proof that homework is helpful for students in elementary school.

“Correlation is not causation,” she said. “Does homework cause achievement, or do high achievers do more homework?”

Vatterott, the author of Rethinking Homework: Best Practices That Support Diverse Needs , thinks there should be more emphasis on improving the quality of homework tasks, and she supports efforts to eliminate homework for younger kids.

“I have no concerns about students not starting homework until fourth grade or fifth grade,” she said, noting that while the debate over homework will undoubtedly continue, she has noticed a trend toward limiting, if not eliminating, homework in elementary school.

The issue has been debated for decades. A TIME cover in 1999 read: “Too much homework! How it’s hurting our kids, and what parents should do about it.” The accompanying story noted that the launch of Sputnik in 1957 led to a push for better math and science education in the U.S. The ensuing pressure to be competitive on a global scale, plus the increasingly demanding college admissions process, fueled the practice of assigning homework.

“The complaints are cyclical, and we’re in the part of the cycle now where the concern is for too much,” Cooper said. “You can go back to the 1970s, when you’ll find there were concerns that there was too little, when we were concerned about our global competitiveness.”

Cooper acknowledged that some students really are bringing home too much homework, and their parents are right to be concerned.

“A good way to think about homework is the way you think about medications or dietary supplements,” he said. “If you take too little, they’ll have no effect. If you take too much, they can kill you. If you take the right amount, you’ll get better.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Putin’s Enemies Are Struggling to Unite

- Women Say They Were Pressured Into Long-Term Birth Control

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- Boredom Makes Us Human

- John Mulaney Has What Late Night Needs

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Katie Reilly at [email protected]

Does Homework Really Help Students Learn?

A conversation with a Wheelock researcher, a BU student, and a fourth-grade teacher

“Quality homework is engaging and relevant to kids’ lives,” says Wheelock’s Janine Bempechat. “It gives them autonomy and engages them in the community and with their families. In some subjects, like math, worksheets can be very helpful. It has to do with the value of practicing over and over.” Photo by iStock/Glenn Cook Photography

Do your homework.

If only it were that simple.

Educators have debated the merits of homework since the late 19th century. In recent years, amid concerns of some parents and teachers that children are being stressed out by too much homework, things have only gotten more fraught.

“Homework is complicated,” says developmental psychologist Janine Bempechat, a Wheelock College of Education & Human Development clinical professor. The author of the essay “ The Case for (Quality) Homework—Why It Improves Learning and How Parents Can Help ” in the winter 2019 issue of Education Next , Bempechat has studied how the debate about homework is influencing teacher preparation, parent and student beliefs about learning, and school policies.

She worries especially about socioeconomically disadvantaged students from low-performing schools who, according to research by Bempechat and others, get little or no homework.

BU Today sat down with Bempechat and Erin Bruce (Wheelock’17,’18), a new fourth-grade teacher at a suburban Boston school, and future teacher freshman Emma Ardizzone (Wheelock) to talk about what quality homework looks like, how it can help children learn, and how schools can equip teachers to design it, evaluate it, and facilitate parents’ role in it.

BU Today: Parents and educators who are against homework in elementary school say there is no research definitively linking it to academic performance for kids in the early grades. You’ve said that they’re missing the point.

Bempechat : I think teachers assign homework in elementary school as a way to help kids develop skills they’ll need when they’re older—to begin to instill a sense of responsibility and to learn planning and organizational skills. That’s what I think is the greatest value of homework—in cultivating beliefs about learning and skills associated with academic success. If we greatly reduce or eliminate homework in elementary school, we deprive kids and parents of opportunities to instill these important learning habits and skills.

We do know that beginning in late middle school, and continuing through high school, there is a strong and positive correlation between homework completion and academic success.

That’s what I think is the greatest value of homework—in cultivating beliefs about learning and skills associated with academic success.

You talk about the importance of quality homework. What is that?

Quality homework is engaging and relevant to kids’ lives. It gives them autonomy and engages them in the community and with their families. In some subjects, like math, worksheets can be very helpful. It has to do with the value of practicing over and over.

What are your concerns about homework and low-income children?

The argument that some people make—that homework “punishes the poor” because lower-income parents may not be as well-equipped as affluent parents to help their children with homework—is very troubling to me. There are no parents who don’t care about their children’s learning. Parents don’t actually have to help with homework completion in order for kids to do well. They can help in other ways—by helping children organize a study space, providing snacks, being there as a support, helping children work in groups with siblings or friends.

Isn’t the discussion about getting rid of homework happening mostly in affluent communities?

Yes, and the stories we hear of kids being stressed out from too much homework—four or five hours of homework a night—are real. That’s problematic for physical and mental health and overall well-being. But the research shows that higher-income students get a lot more homework than lower-income kids.

Teachers may not have as high expectations for lower-income children. Schools should bear responsibility for providing supports for kids to be able to get their homework done—after-school clubs, community support, peer group support. It does kids a disservice when our expectations are lower for them.

The conversation around homework is to some extent a social class and social justice issue. If we eliminate homework for all children because affluent children have too much, we’re really doing a disservice to low-income children. They need the challenge, and every student can rise to the challenge with enough supports in place.

What did you learn by studying how education schools are preparing future teachers to handle homework?

My colleague, Margarita Jimenez-Silva, at the University of California, Davis, School of Education, and I interviewed faculty members at education schools, as well as supervising teachers, to find out how students are being prepared. And it seemed that they weren’t. There didn’t seem to be any readings on the research, or conversations on what high-quality homework is and how to design it.

Erin, what kind of training did you get in handling homework?

Bruce : I had phenomenal professors at Wheelock, but homework just didn’t come up. I did lots of student teaching. I’ve been in classrooms where the teachers didn’t assign any homework, and I’ve been in rooms where they assigned hours of homework a night. But I never even considered homework as something that was my decision. I just thought it was something I’d pull out of a book and it’d be done.

I started giving homework on the first night of school this year. My first assignment was to go home and draw a picture of the room where you do your homework. I want to know if it’s at a table and if there are chairs around it and if mom’s cooking dinner while you’re doing homework.

The second night I asked them to talk to a grown-up about how are you going to be able to get your homework done during the week. The kids really enjoyed it. There’s a running joke that I’m teaching life skills.

Friday nights, I read all my kids’ responses to me on their homework from the week and it’s wonderful. They pour their hearts out. It’s like we’re having a conversation on my couch Friday night.

It matters to know that the teacher cares about you and that what you think matters to the teacher. Homework is a vehicle to connect home and school…for parents to know teachers are welcoming to them and their families.

Bempechat : I can’t imagine that most new teachers would have the intuition Erin had in designing homework the way she did.

Ardizzone : Conversations with kids about homework, feeling you’re being listened to—that’s such a big part of wanting to do homework….I grew up in Westchester County. It was a pretty demanding school district. My junior year English teacher—I loved her—she would give us feedback, have meetings with all of us. She’d say, “If you have any questions, if you have anything you want to talk about, you can talk to me, here are my office hours.” It felt like she actually cared.

Bempechat : It matters to know that the teacher cares about you and that what you think matters to the teacher. Homework is a vehicle to connect home and school…for parents to know teachers are welcoming to them and their families.

Ardizzone : But can’t it lead to parents being overbearing and too involved in their children’s lives as students?

Bempechat : There’s good help and there’s bad help. The bad help is what you’re describing—when parents hover inappropriately, when they micromanage, when they see their children confused and struggling and tell them what to do.

Good help is when parents recognize there’s a struggle going on and instead ask informative questions: “Where do you think you went wrong?” They give hints, or pointers, rather than saying, “You missed this,” or “You didn’t read that.”

Bruce : I hope something comes of this. I hope BU or Wheelock can think of some way to make this a more pressing issue. As a first-year teacher, it was not something I even thought about on the first day of school—until a kid raised his hand and said, “Do we have homework?” It would have been wonderful if I’d had a plan from day one.

Explore Related Topics:

- Share this story

Senior Contributing Editor

Sara Rimer A journalist for more than three decades, Sara Rimer worked at the Miami Herald , Washington Post and, for 26 years, the New York Times , where she was the New England bureau chief, and a national reporter covering education, aging, immigration, and other social justice issues. Her stories on the death penalty’s inequities were nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and cited in the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision outlawing the execution of people with intellectual disabilities. Her journalism honors include Columbia University’s Meyer Berger award for in-depth human interest reporting. She holds a BA degree in American Studies from the University of Michigan. Profile

She can be reached at [email protected] .

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.

There are 81 comments on Does Homework Really Help Students Learn?

Insightful! The values about homework in elementary schools are well aligned with my intuition as a parent.

when i finish my work i do my homework and i sometimes forget what to do because i did not get enough sleep

same omg it does not help me it is stressful and if I have it in more than one class I hate it.

Same I think my parent wants to help me but, she doesn’t care if I get bad grades so I just try my best and my grades are great.

I think that last question about Good help from parents is not know to all parents, we do as our parents did or how we best think it can be done, so maybe coaching parents or giving them resources on how to help with homework would be very beneficial for the parent on how to help and for the teacher to have consistency and improve homework results, and of course for the child. I do see how homework helps reaffirm the knowledge obtained in the classroom, I also have the ability to see progress and it is a time I share with my kids

The answer to the headline question is a no-brainer – a more pressing problem is why there is a difference in how students from different cultures succeed. Perfect example is the student population at BU – why is there a majority population of Asian students and only about 3% black students at BU? In fact at some universities there are law suits by Asians to stop discrimination and quotas against admitting Asian students because the real truth is that as a group they are demonstrating better qualifications for admittance, while at the same time there are quotas and reduced requirements for black students to boost their portion of the student population because as a group they do more poorly in meeting admissions standards – and it is not about the Benjamins. The real problem is that in our PC society no one has the gazuntas to explore this issue as it may reveal that all people are not created equal after all. Or is it just environmental cultural differences??????

I get you have a concern about the issue but that is not even what the point of this article is about. If you have an issue please take this to the site we have and only post your opinion about the actual topic

This is not at all what the article is talking about.

This literally has nothing to do with the article brought up. You should really take your opinions somewhere else before you speak about something that doesn’t make sense.

we have the same name

so they have the same name what of it?

lol you tell her

totally agree

What does that have to do with homework, that is not what the article talks about AT ALL.

Yes, I think homework plays an important role in the development of student life. Through homework, students have to face challenges on a daily basis and they try to solve them quickly.I am an intense online tutor at 24x7homeworkhelp and I give homework to my students at that level in which they handle it easily.

More than two-thirds of students said they used alcohol and drugs, primarily marijuana, to cope with stress.

You know what’s funny? I got this assignment to write an argument for homework about homework and this article was really helpful and understandable, and I also agree with this article’s point of view.

I also got the same task as you! I was looking for some good resources and I found this! I really found this article useful and easy to understand, just like you! ^^

i think that homework is the best thing that a child can have on the school because it help them with their thinking and memory.

I am a child myself and i think homework is a terrific pass time because i can’t play video games during the week. It also helps me set goals.

Homework is not harmful ,but it will if there is too much

I feel like, from a minors point of view that we shouldn’t get homework. Not only is the homework stressful, but it takes us away from relaxing and being social. For example, me and my friends was supposed to hang at the mall last week but we had to postpone it since we all had some sort of work to do. Our minds shouldn’t be focused on finishing an assignment that in realty, doesn’t matter. I completely understand that we should have homework. I have to write a paper on the unimportance of homework so thanks.

homework isn’t that bad

Are you a student? if not then i don’t really think you know how much and how severe todays homework really is

i am a student and i do not enjoy homework because i practice my sport 4 out of the five days we have school for 4 hours and that’s not even counting the commute time or the fact i still have to shower and eat dinner when i get home. its draining!

i totally agree with you. these people are such boomers

why just why

they do make a really good point, i think that there should be a limit though. hours and hours of homework can be really stressful, and the extra work isn’t making a difference to our learning, but i do believe homework should be optional and extra credit. that would make it for students to not have the leaning stress of a assignment and if you have a low grade you you can catch up.

Studies show that homework improves student achievement in terms of improved grades, test results, and the likelihood to attend college. Research published in the High School Journal indicates that students who spent between 31 and 90 minutes each day on homework “scored about 40 points higher on the SAT-Mathematics subtest than their peers, who reported spending no time on homework each day, on average.” On both standardized tests and grades, students in classes that were assigned homework outperformed 69% of students who didn’t have homework. A majority of studies on homework’s impact – 64% in one meta-study and 72% in another – showed that take home assignments were effective at improving academic achievement. Research by the Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) concluded that increased homework led to better GPAs and higher probability of college attendance for high school boys. In fact, boys who attended college did more than three hours of additional homework per week in high school.

So how are your measuring student achievement? That’s the real question. The argument that doing homework is simply a tool for teaching responsibility isn’t enough for me. We can teach responsibility in a number of ways. Also the poor argument that parents don’t need to help with homework, and that students can do it on their own, is wishful thinking at best. It completely ignores neurodiverse students. Students in poverty aren’t magically going to find a space to do homework, a friend’s or siblings to help them do it, and snacks to eat. I feel like the author of this piece has never set foot in a classroom of students.

THIS. This article is pathetic coming from a university. So intellectually dishonest, refusing to address the havoc of capitalism and poverty plays on academic success in life. How can they in one sentence use poor kids in an argument and never once address that poor children have access to damn near 0 of the resources affluent kids have? Draw me a picture and let’s talk about feelings lmao what a joke is that gonna put food in their belly so they can have the calories to burn in order to use their brain to study? What about quiet their 7 other siblings that they share a single bedroom with for hours? Is it gonna force the single mom to magically be at home and at work at the same time to cook food while you study and be there to throw an encouraging word?

Also the “parents don’t need to be a parent and be able to guide their kid at all academically they just need to exist in the next room” is wild. Its one thing if a parent straight up is not equipped but to say kids can just figured it out is…. wow coming from an educator What’s next the teacher doesn’t need to teach cause the kid can just follow the packet and figure it out?

Well then get a tutor right? Oh wait you are poor only affluent kids can afford a tutor for their hours of homework a day were they on average have none of the worries a poor child does. Does this address that poor children are more likely to also suffer abuse and mental illness? Like mentioned what about kids that can’t learn or comprehend the forced standardized way? Just let em fail? These children regularly are not in “special education”(some of those are a joke in their own and full of neglect and abuse) programs cause most aren’t even acknowledged as having disabilities or disorders.

But yes all and all those pesky poor kids just aren’t being worked hard enough lol pretty sure poor children’s existence just in childhood is more work, stress, and responsibility alone than an affluent child’s entire life cycle. Love they never once talked about the quality of education in the classroom being so bad between the poor and affluent it can qualify as segregation, just basically blamed poor people for being lazy, good job capitalism for failing us once again!

why the hell?

you should feel bad for saying this, this article can be helpful for people who has to write a essay about it

This is more of a political rant than it is about homework

I know a teacher who has told his students their homework is to find something they are interested in, pursue it and then come share what they learn. The student responses are quite compelling. One girl taught herself German so she could talk to her grandfather. One boy did a research project on Nelson Mandela because the teacher had mentioned him in class. Another boy, a both on the autism spectrum, fixed his family’s computer. The list goes on. This is fourth grade. I think students are highly motivated to learn, when we step aside and encourage them.

The whole point of homework is to give the students a chance to use the material that they have been presented with in class. If they never have the opportunity to use that information, and discover that it is actually useful, it will be in one ear and out the other. As a science teacher, it is critical that the students are challenged to use the material they have been presented with, which gives them the opportunity to actually think about it rather than regurgitate “facts”. Well designed homework forces the student to think conceptually, as opposed to regurgitation, which is never a pretty sight

Wonderful discussion. and yes, homework helps in learning and building skills in students.

not true it just causes kids to stress

Homework can be both beneficial and unuseful, if you will. There are students who are gifted in all subjects in school and ones with disabilities. Why should the students who are gifted get the lucky break, whereas the people who have disabilities suffer? The people who were born with this “gift” go through school with ease whereas people with disabilities struggle with the work given to them. I speak from experience because I am one of those students: the ones with disabilities. Homework doesn’t benefit “us”, it only tears us down and put us in an abyss of confusion and stress and hopelessness because we can’t learn as fast as others. Or we can’t handle the amount of work given whereas the gifted students go through it with ease. It just brings us down and makes us feel lost; because no mater what, it feels like we are destined to fail. It feels like we weren’t “cut out” for success.

homework does help

here is the thing though, if a child is shoved in the face with a whole ton of homework that isn’t really even considered homework it is assignments, it’s not helpful. the teacher should make homework more of a fun learning experience rather than something that is dreaded

This article was wonderful, I am going to ask my teachers about extra, or at all giving homework.

I agree. Especially when you have homework before an exam. Which is distasteful as you’ll need that time to study. It doesn’t make any sense, nor does us doing homework really matters as It’s just facts thrown at us.

Homework is too severe and is just too much for students, schools need to decrease the amount of homework. When teachers assign homework they forget that the students have other classes that give them the same amount of homework each day. Students need to work on social skills and life skills.

I disagree.

Beyond achievement, proponents of homework argue that it can have many other beneficial effects. They claim it can help students develop good study habits so they are ready to grow as their cognitive capacities mature. It can help students recognize that learning can occur at home as well as at school. Homework can foster independent learning and responsible character traits. And it can give parents an opportunity to see what’s going on at school and let them express positive attitudes toward achievement.

Homework is helpful because homework helps us by teaching us how to learn a specific topic.

As a student myself, I can say that I have almost never gotten the full 9 hours of recommended sleep time, because of homework. (Now I’m writing an essay on it in the middle of the night D=)

I am a 10 year old kid doing a report about “Is homework good or bad” for homework before i was going to do homework is bad but the sources from this site changed my mind!

Homeowkr is god for stusenrs

I agree with hunter because homework can be so stressful especially with this whole covid thing no one has time for homework and every one just wants to get back to there normal lives it is especially stressful when you go on a 2 week vaca 3 weeks into the new school year and and then less then a week after you come back from the vaca you are out for over a month because of covid and you have no way to get the assignment done and turned in

As great as homework is said to be in the is article, I feel like the viewpoint of the students was left out. Every where I go on the internet researching about this topic it almost always has interviews from teachers, professors, and the like. However isn’t that a little biased? Of course teachers are going to be for homework, they’re not the ones that have to stay up past midnight completing the homework from not just one class, but all of them. I just feel like this site is one-sided and you should include what the students of today think of spending four hours every night completing 6-8 classes worth of work.

Are we talking about homework or practice? Those are two very different things and can result in different outcomes.

Homework is a graded assignment. I do not know of research showing the benefits of graded assignments going home.

Practice; however, can be extremely beneficial, especially if there is some sort of feedback (not a grade but feedback). That feedback can come from the teacher, another student or even an automated grading program.

As a former band director, I assigned daily practice. I never once thought it would be appropriate for me to require the students to turn in a recording of their practice for me to grade. Instead, I had in-class assignments/assessments that were graded and directly related to the practice assigned.

I would really like to read articles on “homework” that truly distinguish between the two.

oof i feel bad good luck!

thank you guys for the artical because I have to finish an assingment. yes i did cite it but just thanks

thx for the article guys.

Homework is good

I think homework is helpful AND harmful. Sometimes u can’t get sleep bc of homework but it helps u practice for school too so idk.

I agree with this Article. And does anyone know when this was published. I would like to know.

It was published FEb 19, 2019.

Studies have shown that homework improved student achievement in terms of improved grades, test results, and the likelihood to attend college.

i think homework can help kids but at the same time not help kids

This article is so out of touch with majority of homes it would be laughable if it wasn’t so incredibly sad.

There is no value to homework all it does is add stress to already stressed homes. Parents or adults magically having the time or energy to shepherd kids through homework is dome sort of 1950’s fantasy.

What lala land do these teachers live in?

Homework gives noting to the kid

Homework is Bad

homework is bad.

why do kids even have homework?

Comments are closed.

Latest from Bostonia

American academy of arts & sciences welcomes five bu members, com’s newest journalism grad took her time, could boston be the next city to impose congestion pricing, alum has traveled the world to witness total solar eclipses, opening doors: rhonda harrison (eng’98,’04, grs’04), campus reacts and responds to israel-hamas war, reading list: what the pandemic revealed, remembering com’s david anable, cas’ john stone, “intellectual brilliance and brilliant kindness”, one good deed: christine kannler (cas’96, sph’00, camed’00), william fairfield warren society inducts new members, spreading art appreciation, restoring the “black angels” to medical history, in the kitchen with jacques pépin, feedback: readers weigh in on bu’s new president, com’s new expert on misinformation, and what’s really dividing the nation, the gifts of great teaching, sth’s walter fluker honored by roosevelt institute, alum’s debut book is a ramadan story for children, my big idea: covering construction sites with art, former terriers power new professional women’s hockey league.

The History of Homework: Why Was it Invented and Who Was Behind It?

- By Emily Summers

- February 14, 2020

Homework is long-standing education staple, one that many students hate with a fiery passion. We can’t really blame them, especially if it’s a primary source of stress that can result in headaches, exhaustion, and lack of sleep.

It’s not uncommon for students, parents, and even some teachers to complain about bringing assignments home. Yet, for millions of children around the world, homework is still a huge part of their daily lives as students — even if it continues to be one of their biggest causes of stress and unrest.

It makes one wonder, who in their right mind would invent such a thing as homework?

Who Invented Homework?

Pliny the younger: when in ancient rome, horace mann: the father of modern homework, the history of homework in america, 1900s: anti-homework sentiment & homework bans, 1930: homework as child labor, early-to-mid 20th century: homework and the progressive era, the cold war: homework starts heating up, 1980s: homework in a nation at risk, early 21 st century, state of homework today: why is it being questioned, should students get homework pros of cons of bringing school work home.

Online, there are many articles that point to Roberto Nevilis as the first educator to give his students homework. He created it as a way to punish his lazy students and ensure that they fully learned their lessons. However, these pieces of information mostly come from obscure educational blogs or forum websites with questionable claims. No credible news source or website has ever mentioned the name Roberto Nevilis as the person who invented homework . In fact, it’s possible that Nevilis never even existed.

As we’re not entirely sure who to credit for creating the bane of students’ existence and the reasons why homework was invented, we can use a few historical trivia to help narrow down our search.