International Research in Children's Literature

Subject Area and Category

- Literature and Literary Theory

Edinburgh University Press

Publication type

17556198, 17556201

Information

How to publish in this journal

The set of journals have been ranked according to their SJR and divided into four equal groups, four quartiles. Q1 (green) comprises the quarter of the journals with the highest values, Q2 (yellow) the second highest values, Q3 (orange) the third highest values and Q4 (red) the lowest values.

The SJR is a size-independent prestige indicator that ranks journals by their 'average prestige per article'. It is based on the idea that 'all citations are not created equal'. SJR is a measure of scientific influence of journals that accounts for both the number of citations received by a journal and the importance or prestige of the journals where such citations come from It measures the scientific influence of the average article in a journal, it expresses how central to the global scientific discussion an average article of the journal is.

Evolution of the number of published documents. All types of documents are considered, including citable and non citable documents.

This indicator counts the number of citations received by documents from a journal and divides them by the total number of documents published in that journal. The chart shows the evolution of the average number of times documents published in a journal in the past two, three and four years have been cited in the current year. The two years line is equivalent to journal impact factor ™ (Thomson Reuters) metric.

Evolution of the total number of citations and journal's self-citations received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. Journal Self-citation is defined as the number of citation from a journal citing article to articles published by the same journal.

Evolution of the number of total citation per document and external citation per document (i.e. journal self-citations removed) received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. External citations are calculated by subtracting the number of self-citations from the total number of citations received by the journal’s documents.

International Collaboration accounts for the articles that have been produced by researchers from several countries. The chart shows the ratio of a journal's documents signed by researchers from more than one country; that is including more than one country address.

Not every article in a journal is considered primary research and therefore "citable", this chart shows the ratio of a journal's articles including substantial research (research articles, conference papers and reviews) in three year windows vs. those documents other than research articles, reviews and conference papers.

Ratio of a journal's items, grouped in three years windows, that have been cited at least once vs. those not cited during the following year.

Evolution of the percentage of female authors.

Evolution of the number of documents cited by public policy documents according to Overton database.

Evoution of the number of documents related to Sustainable Development Goals defined by United Nations. Available from 2018 onwards.

Leave a comment

Name * Required

Email (will not be published) * Required

* Required Cancel

The users of Scimago Journal & Country Rank have the possibility to dialogue through comments linked to a specific journal. The purpose is to have a forum in which general doubts about the processes of publication in the journal, experiences and other issues derived from the publication of papers are resolved. For topics on particular articles, maintain the dialogue through the usual channels with your editor.

Follow us on @ScimagoJR Scimago Lab , Copyright 2007-2024. Data Source: Scopus®

Cookie settings

Cookie Policy

Legal Notice

Privacy Policy

- What is IBBY

- Organization

- Biennial Report

- Presidents of IBBY

- Honorary Members

- Jella Lepman Medal

- Patrons and Sponsors

- Friends of IBBY

- IBBY Partners

- Hans Christian Andersen Award

- IBBY-Asahi Reading Promotion Award

- IBBY-iRead Outstanding Reading Promoter Award

- IBBY Honour List

- International Children's Book Day

- IBBY-Yamada Fund

- IBBY Collection for Young People with Disabilities

- Silent Books

- Sustainable Development Goals Book Club

- Exhibitions

- Children's Books in Europe

- Books for Africa Books from Africa

- IBBY Children in Crisis Fund

- National Sections

- Individual Members

- Regional Conferences & Meetings

- Latest News

- Media Releases

- International Newsletters

- National Newsletters

- Regional Newsletters

- IBBY Calendar 2024

A Journal of International Children's Literature

Bookbird: A Journal of International Children's Literature (ISSN 0006 7377) is a refereed journal published quarterly by IBBY. Bookbird aims to communicate new ideas to the community of readers interested in children's books and is open to any topic in the field of international children's literature. Bookbird also includes themed issues for which the editor will post calls for manuscripts on the IBBY website. Bookbird also includes news of IBBY projects and events which are highlighted in the Focus IBBY column. Other regular features include coverage of children's literature studies and children's literature awards around the world as well as reading promotion projects worldwide.

Bookbird is indexed by Scopus and is available in print and online through Project Muse. For more information see below and the Bookbird Facebook page.

Bookbird en Español

Bookbird, Inc. se complace en anunciar que Bookbird, la revista de literatura infantil internacional de IBBY está disponible en versión digital en español. Bookbird en español reproduce el contenido íntegro y el formato idéntico al de la edición en inglés, y se edita trimestralmente, poco después de la publicación del número en su versión original.

Bookbird en español es una publicación de Jacarandá Editoras (Argentina). Para más información sobre la revista y cómo suscribirse, visite bookbird-esp.com.ar .

¡Disfrute de la maravillosa revista de IBBY desde ya, en su idioma!

Bookbird, Inc. is delighted to announce that IBBY’s journal Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature is now available in Spanish in an online edition. The contents and layout will be exactly the same as in the English language edition, and each issue will appear soon after each English language issue is published.

Bookbird en Español is produced by Jacarandá Editoras in Argentina. Details about subscribing may be found at bookbird-esp.com.ar .

Now Spanish speakers can read IBBY’s wonderful journal in Spanish!

Latest Bookbird issue

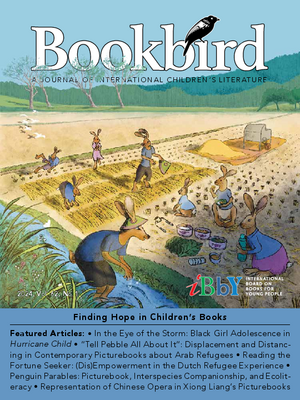

Bookbird Issue 1 / 2024 (61.4) Finding Hope in Children’s Books

Dowload Focus IBBY Subscribe to Bookbird Download articles on Project Muse

Call for Papers - "Nonfiction in children's books"

Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature is seeking contributions for a special issue on Nonfiction in Children’s Literature Call open until 30 August 2024

We are living in the age of information and misinformation, where the current state of technology both promises remarkable advancements in knowledge and continually blurs the lines between reality and fiction. From AI advocates envisioning a future where humans exist as immortal programs within machine to DNA studies tracing the peopling of every continent over the thousands of years, from bots masquerading as people and “deep fakes” emulating artifacts plaguing our screens, to our ever-expanding ability to access and translate archives in any language, we imbibe and exhale information with every breath. Texts, images, videos, and sound can be ever more easily manipulated, manufactured, and distorted. In this fast-changing environment, the world of books for children and young adults is inevitably affected and transformed. What are the boundaries of fiction and nonfiction? Where do children’s books fit in this universe where digital information both connects and entraps us? Or a more extreme question, how do we define, use, and understand nonfiction books for children and young adults in this era?

The scholarly exploration of youth nonfiction is an emerging field in this challenging time. As Nina Goga, Sarah Hoem Iversen, and Anne-Stefi Teigland argue in their edited volume, Verbal and Visual Strategies in Nonfiction Picturebooks (2021), there has been an “unwillingness to include the many verbal and visual strategies of nonfiction within the concept of children’s literature.” This gap in the research opens up a new opportunity. On the one hand, we have the chance to explore with fresh eyes what “nonfiction” books have the capacity to achieve—how they narrate, engage, challenge, inspire readers through words, design, and images both created by artists and discovered in archives. On the other hand, we must examine the beliefs, biases, prejudices, and assumptions that result in excellence in children’s literature being overwhelmingly associated with fiction. What is the aesthetic excellence in children’s nonfiction? What role can nonfiction play in the reading lives of children and young adults?

The focus in this special issue of Bookbird is on nonfiction for children and teenagers—what it has to offer to those readers and its place in the worldview of the adult gatekeepers. We are looking for submission addressing the following matters:

- The ability, or inability, of nonfiction to inspire imagination

- When nonfiction uses photographs as illustrations, the book designer rather than an artist shapes the flow of art and text. How do these choices influence readers?

- How do we draw the border between narrative nonfiction and historical fiction for young readers?

- The artistic consideration in image replication / reproduction in nonfiction graphic novels or pictureboosk, including the use of paratexts

- The positioning of nonfiction and reading for pleasure

- The historical study of nonfiction and its place in children’s literature

- The uses of nonfiction in libraries, schools, and reading promotion

- The attitude towards nonfiction books for children and young adults, including the abiding preference for fiction books in various awards for children’s books.

- History is often taught as a national pageant in order to inculcate specific values of patriotism and citizenship in students, how can books with transnational and transcultural narratives bring readers broader perspectives on subjects such as migration, climate, trade, science, disease, biology, the spread of ideas and philosophies?

Full papers should be submitted to the editor, Chrysogonus Siddha Malilang ( [email protected] ), and guest editor Marc Aronson ( [email protected] ) by 30 August 2023. We also welcome submissions for “Letters” and “Children and Their Books” with the same topics. Full submission details are available in the section "Call for Paper: General guidelines" located on this web page.

Call For Papers - General Guidelines

Would you like to write for Bookbird?

Feature Articles Bookbird publishes articles on children’s literature with an international perspective four times a year. Some of our issues are devoted to special topics. Details and deadlines of these issues are available in this page. The articles should be approximately 4000 words in length. Full paper should be submitted to the editor, Chrysogonus Siddha Malilang ( [email protected] ).

Books on Books Bookbird also publishes reviews of critical and scholarly work on children’s literature. Reviews should be no more than 1000 words in length. The “Books on Books” section is handled by the International Youth Library in Munich, Germany. If you wish to review a scholarly study of children’s literature, or if you would like to submit a review copy, contact the IYL ( [email protected] ).

Children and Their Books Bookbird provides a forum where those working with children and their literature can write about their experiences – teachers, librarians, publishers, authors, and parents. Short articles of ca. 2500 words discussing the ways in which you have worked with children and their literature or have watched children respond to literature are welcomed. Articles should be submitted to the editor, Chrysogonus Siddha Malilang ( [email protected] ).

Letters Bookbird publishes “Letters” of 700 words on individual works of children’s literature, or focusing on a particular author or illustrator.

Postcards Bookbird receives “postcards” from every corner of the globe. These are brief presentation of ca. 150 words on individual books. Postcard suggestions should be sent to the postcard editor, Siobhan Parkinson ( [email protected] ).

For further information, please contact:

Editor Chrysogonus Siddha Malilang: [email protected] Read more about Bookbird: www.ibby.org/bookbird Subscribe to Bookbird: www-press.jhu.edu/journals/bookbird

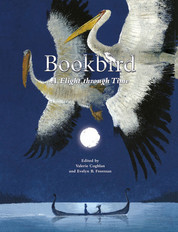

Bookbird: A Flight Through Time

Bookbird: A Flight through Time captures in words and images the story of Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature, the official publication of the International Board on Books for Young People, from its beginning as a modest bulletin to an internationally acclaimed quarterly publication. Through the voices of many involved with Bookbird, this book tells the story of an important part of children’s literature in an international context over more than sixty years.

Buy the book Bookbird: A Flight through Time

Subscriptions and Back Issues

Issues of Bookbird from 2008 onwards are available by online subscription through Project Muse . Bookbird electronic or print subscriptions can be ordered through JHU Bookbird Subscriptions .

Contents of Bookbird issues 2013 to 2023

Back issues of Bookbird from 1963 to 2019 are available as PDFs from the IBBY Archives .

Editor and Editorial Review Board

Bookbird editor 2022-.

Chrysogonus Siddha Malilang is a researcher and senior lecturer at Malmö University, Sweden. He holds a PhD in Literature Studies (English) with an interest in Creative Writing Pedagogy, Play in Education, Critical Pedagogy, Community of Practice, and a/r/tography. He is also interested in Children's Literature and New Media (such as graphic novels and video games).

Chrysogonus Siddha Malilang has published books for young adult in Bahasa Indonesia in 2006. During his doctoral studies in Macao, he worked as an editor at the Association of Stories in Macao (ASM), a community publisher based in Macao SAR publishing poetry, fiction, life writing, and translated works in various languages. He has also published Indonesian translations of picture books.

Bookbird Editorial Review Board

Bookbird inc. board.

Valerie Coghlan , President Evelyn B. Freeman , Secretary Ellis Vance , Treasurer

Doris Breitmoser , EC Member of the Board Junko Yokota , EC Member of the Board

Ethics and Malpractice Statement

Publication Ethics and Publication Malpractice Statement

Bookbird: Journal of International Children’s Literature follows best practices to ensure ethics in publication and the high quality of published papers. In the process of selecting, evaluating, reviewing, editing, preparing for publication and publishing manuscripts, the journal is guided by ethical principles and best practice to achieve and maintain a high standard of scholarly literature, as expressed in the Guidelines and Codes of Conduct issued by the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) www.publicationethics.org Full conformity with the standards of ethical behaviour is expected from all parties involved: editors, reviewers, authors and the publisher.

DUTIES OF EDITORS Publication decisions All submitted manuscripts are considered for publication. The editor evaluates the manuscript for originality and appropriateness of content and form as required in the Guidelines for Contributors. Manuscripts deemed satisfactory are subjected to double-blind peer review. The editor-in-chief asks two or more individuals who possess relevant expertise to act as referees, provides them with clear guidelines regarding the reviewing process and is also responsible for the peer review process being objective and completed in a timely fashion. Reviewers are given special forms on which to write their own evaluation and suggest classification of the manuscript. The decision concerning which of the articles submitted for publication should be published is made by the editor-in-chief, based on the reviewers’ evaluations and potentially guided by the opinions of the members of the editorial board and reviewers. The final responsibility for all editorial decisions, as well as for everything published in Bookbird: Journal of International Children’s Literature, rests with the editor-in-chief. The editor-in-chief informs the authors of the submitted manuscripts about the results of the peer review process within six months of their submission. If the manuscript is rejected, the editor-in-chief provides a clear explanation to the author.

Impartiality Each manuscript is evaluated impartially for its intellectual content, without regard to the gender, race, citizenship, ethnicity, religious, ideological or political beliefs, academic title, institutional affiliation, academic reputation, etc., of the author(s).

Confidentiality and disclosure The editor-in-chief is responsible for ensuring the integrity and confidentiality of each manuscript submitted to the editorial board of Bookbird: Journal of International Children’s Literature during the reviewing process. All manuscripts received are treated as confidential documents by all the members of the editorial board. Since each manuscript is subject to a double-blind peer review, the identities of both authors and reviewers are protected. The editor-in-chief and the members of the editorial board do not disclose any content presented in submitted and unpublished manuscripts, or use it in their own research or in any other way, without the explicit written consent of the author(s).

Conflicts of interest The editor-in-chief requires all members of the editorial board, authors and reviewers to disclose all potential conflicts of interest regarding submitted manuscripts, such as competitive, collaborative or other relationships with any of the parties. Should a conflict of interest appear that involves the editor-in-chief or any of the members of the editorial board, this person should excuse him/herself from the reviewing and decision-making process and delegate it to the deputy editor or another member of the editorial board.

Ethical misconduct and errors The editor-in-chief will respond to all allegations of ethical misconduct and take appropriate steps to rectify possible errors and omissions. The said steps primarily include contacting the author(s) of the paper in question, but may extend to referring the case to appropriate academic or research institutions. If allegations refer to an unpublished manuscript, its publication will be postponed until the case has been satisfactorily resolved. Should substantial errors or inaccuracies be determined in a submitted manuscript or published paper, the editor-in-chief will cooperate with the author(s) in amending the manuscript in question or, in the case of published papers, prepare and publish a correction. In the most severe cases, the editor-in-chief can, upon conferring with the author(s) and publisher, decide to retract the paper from the journal.

DUTIES OF REVIEWERS The role of reviewer Peer review assists the editor-in-chief in making editorial decisions. The reviewer may also – through editorial communication with the author(s) – help improve the quality of submitted manuscripts. The reviewer should evaluate submitted manuscripts in a critical but constructive way and make a list of detailed comments and suggestions regarding the research itself and the way it is presented in the manuscript. Reviewers should also identify relevant published work that has not been cited by the author(s) and warn the editor-in-chief of possible cases of plagiarism, copyright infringement, etc. Finally, the reviewer should advise the editor-in-chief on whether or not a given manuscript is suitable for publication in Bookbird: Journal of International Children’s Literature.

The peer review process Reviews should be conducted objectively and strictly on scholarly grounds. Reviewers are expected to express their views in a clear and constructive way, and support them with arguments. Inappropriate comments and personal criticism are deemed unacceptable.

Promptness and conflict of interest Invited referees who feel unqualified to review a given manuscript or are aware that its timely review will not be possible should immediately notify the editor-in-chief. Reviewers should excuse themselves from reviewing manuscripts in which they have conflicts of interests and should notify the editor-in-chief if such a case occurs.

Confidentiality and disclosure Manuscripts received for review must be treated as confidential documents. The reviewer must not show or discuss the manuscripts with others, except with special permission from the editor- in-chief. Content presented in the submitted manuscripts must not be publicly disclosed, used for one's own research, or used in any other way.

DUTIES OF AUTHORS Reporting standards Authors of reports of original research should present an accurate account of the work performed in the context of previous research, as well as an objective discussion of its significance. Authors should describe their methods and present their findings clearly and unambiguously. They should represent the work of others accurately in citations and quotations from the original publications they have consulted. Authors submitting their manuscripts to the editorial board of Bookbird: Journal of International Children’s Literature are held accountable for the originality of their work, as well as for the accuracy of the information and references contained therein. Submitted manuscripts should follow the Guidelines for Contributors available on the website of the journal (Bookbird.org). Papers should be submitted in English. The accuracy and appropriateness of the language used are also the responsibility of the author(s).

Originality and plagiarism Bookbird: Journal of International Children’s Literature publishes previously unpublished academic papers related to children’s and young adult literature and culture. Papers that have previously been presented at a conference, but are not to be published in the conference proceedings, may also be considered (the author should notify the editorial board about this in advance). Manuscripts submitted to Bookbird: Journal of International Children’s Literature should not have been submitted to other publications at the same time. An authorial statement claiming the status of the manuscript in these respects should be sent to the official email address of the journal (Bookbird.org) upon the submission of a manuscript. Authors should ensure that they have written entirely original works and that any data, quotations, etc., taken from the works of others is appropriately recognised and cited. Authors are responsible for obtaining copyright clearance for illustrations, photographs, tables and other material protected by copyright laws. Copyright materials should only be reproduced with appropriate permission and acknowledgement.

Authorship of a manuscript Only those individuals who have made a significant contribution to the manuscript and taken part in its production can be regarded as its authors. The author submitting the manuscript for publication in Bookbird: Journal of International Children’s Literature should ensure that everyone who has taken part in the production of the manuscript is included in the list of authors. The submitting author should also make sure that all co-authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript and have agreed to its submission to the journal.

Communicating with editors and reviewers Authors should respond to editorial and reviewers' comments in a professional and timely manner. If authors decide to withdraw a manuscript that has already been submitted for review or if they are not willing to accept reviewers' suggestions, they should immediately notify the editor-in-chief.

Disclosure and conflicts of interest In their manuscripts, authors should disclose any financial or other substantial conflict of interest that might be construed to influence their research or the interpretation of its results. All organisations that have supported the research and all sources of financial support, as well as their role in conducting the research and processing and publishing its results, should be clearly indicated in the manuscript. If the source of funding has not been explicitly stated, this will be taken as a sign that the author him/herself bears the financial burden for conducting the research and producing the manuscript.

Errors in manuscripts and published works If at any time the author(s) discover(s) a significant error or inaccuracy in the submitted manuscript, that error or inaccuracy must immediately be reported to the editor-in-chief. In the case of errors or inaccuracies detected in already published papers, the author(s) must promptly notify the editor-in-chief and cooperate with him/her on publishing an appropriate correction or erratum, or, in the case of extremely severe errors, retract the paper from the journal.

Bookbird: A Journal of International Children's Literature

Chrysogonus Siddha Malilang, Malmö University, Sweden

Journal Details

Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature publishes reviewed academic articles on children’s literature with an international perspective. Articles that compare literatures from different countries are of interest, as are papers on translation studies and articles that discuss the reception of work from one country in another. Articles concerned with a particular national literature or a particular book or writer may also be suitable, but it is important that the article should be of interest to an international audience and written without assuming excessive background information.

Bookbird also provides a forum, “Children and Their Books,” in which those working directly with children and their books (e.g. teachers, librarians and parents) or those working in the publishing industry can present their work. These pieces are shorter and are not peer reviewed. They are expected to present good practice and to stimulate other readers who work with children. They should also create a dialogue between the academic articles and day-to-day practice.

Bookbird publishes reviews of both primary and secondary sources. Primary reviews are in the form of brief Postcards on individual works of recently published children’s literature and Letters that discuss the work of a particular author or illustrator. Bookbird also publishes standard academic reviews of recently published critical works on children’s literature. Reviews of non-Anglophone works are particularly welcomed.

Academic works for review should be sent to: Jutta Reusch, Periodical Section, Internationale Jugendbibliothek Schloss Blutenburg Seldweg 15 Munich, DEU 81247 Germany.

Bookbird is published four times a year (in January, April, July and October). There is no particular deadline for Bookbird (except in the case of occasional special issues), and papers tend to be published roughly in the order in which they are received. The details and deadlines of special issues can be found on Bookbird ’s homepage .

However, since Bookbird is a refereed journal, and the refereeing process can take several weeks or months, there may be a lapse of quite some time between an academic article being received and being accepted for publication, and then another lapse of time before it is actually published. As a rule, academic articles that are accepted are published within a year of submission and works for “Children and Their Books” within three issues.

Length and Submission Guidelines

Academic articles should not exceed 4000 words. Papers for “Children and Their Books” should not exceed 2500 words. Postcards must be under 300 words and Letters should not exceed 1000 words. Reviews of secondary sources should not exceed 500 words. Save your paper as a .DOC or .DOCX file (if you are using Word for Windows) or an .RTF file (if you are a Macintosh user) and send as an email attachment. Send accompanying pictures as .JPGs at 300 dpi. Material submitted to Bookbird must be original and must not be under submission elsewhere.

Please submit papers via email to Chrysogonus Siddha Malilang ( [email protected] ). Use the following formula in the email subject line: ‘ Bookbird submission XX’, where XX stands for your initials.

Include some information about yourself (e.g., XX lectures in children’s literature at ABC University, Anycity, and has recently published a book on ...) in the body of the email (or in a separate document), not in the paper itself.

Authors are responsible for gaining permission to reproduce illustrations or lengthy quotations from the copyright-holder. Forms will be provided to assist you in this process.

Bookbird is published in English only. If you are unable to write in English, please have your work translated by a reputable translator before submitting it. Bear in mind that all requests for alterations will come in English and will refer to the English version. If you are able to write in English but you have doubts about the quality of your language, please have it checked before you submit it. If the editors find your topic and argument compelling, they may help you revise the language of your paper before it is submitted for peer review.

Even though you are writing in English, please give the names of organizations, institutes and published material in the original language, with an English translation in square brackets, for example: Jens Peder Larsen was awarded the 1992 Children’s Book Prize for his book Bronden [ The Well ].

Include diacritical marks (accents, umlauts etc.) in all titles and names. If you are unable do this, then please indicate in a note how the words should correctly be written. In the case of non-Roman alphabets, please supply a transliteration.

Writing style

Bookbird is a serious academic journal, and as such it publishes, in the main, serious academic articles. This does not mean that we encourage contributors to be somber or earnest or ‘heavy’ in their style. Although most contributors to Bookbird will be academics or children’s literature professionals, many of the readers may have a more general interest, and we want Bookbird to appeal to them as well as to the professionals. For this reason, we prefer a style that engages the reader’s interest and takes the reader’s requirements into account. So when writing for Bookbird , by all means approach your subject seriously and present your research or your argument as you would for your colleagues, but do keep the more general reader in mind as well.

Keep in mind that many Bookbird readers do not have English as their first language, so clarity both in your arguments and in your language is of great value. A simple strategy like breaking up the text with a few headings can be very helpful to a reader who finds it difficult to read a dense text. Irony is best avoided as it often leads to confusion.

Bookbird uses MLA (Modern Language Association) format; please follow the most current edition. Authors should consult the guidelines, but some of the more common matters are also mentioned below.

Spelling and Punctuation

Bookbird follows the conventions of American English. The editors may change your spellings and punctuation to ensure consistency in style across the journal.

Quotation marks: Please use double quotation marks (“like this”) for direct quotations. Punctuation marks which you have added (such as full stops or exclamation marks) should not appear within the double quotation marks. Single quotation marks (‘like this’) are used to indicate quotations within a quotation). They may also be used for emphasis, although italics are preferred.

Notes and References

Use endnotes rather than footnotes, keyed by superior (superscript) number, only when absolutely necessary , for extra information that does not fit into the flow of the text.

Bear in mind that information in endnote form is quite difficult to read, and may be off-putting to readers. So, try to reduce the number of endnotes by using a combination of in-text references and reference lists for bibliographical information. This is a neater and more reader-friendly system and is preferred by Bookbird .

In-text references: children's books

Please refer to a previously mentioned children’s book by the title , not by the author—date. After the first reference, you may abbreviate the title if it is a long one and the abbreviation is clear.

In-text references: critical works

The first time you refer to a secondary source or a critical work in the text, please give the author’s full name. Thereafter please use the author’s last name, date of publication and page number using the conventions outlined in the MLA style guide.

Works Cited: Listing children’s books

It is usually more helpful to readers if you list children’s books separately from the list of secondary sources.

A list of children’s books by a particular author is usually best organized in chronological (or reverse chronological) order, but a list of children’s books by various authors is probably easier to consult if it is laid out in alphabetical order.

Works Cited: Listing secondary sources

Please use the most recent edition of MLA handbook for full details. The examples below are intended as a brief guide.

Sandroni, Laura and Luiz Raul Machado. A criança e I kuvri: Guia pràtico de estimulo à leitura [The Child and the Book: A Practical Guide for Encouraging Reading]. São Paulo: Atica, 1986.

Translated book

Reuter, Bjarne. Buster’s World. Trans. Anthea Bell. New York: E P Dutton, 1989. Originally published as Busters verden Copenhagen , Branner og Korch, 1978.

Journal article

Jenkins, Christine. “Heartthrobs and Heartbreaks: A Guide to Young Adult Books with Gay Themes.” Out/Look 3.3 (1988): 82-91.

Article in a book

Purcell, Arthur H. “Better Waste Management Strategies Are Needed to Avert a Garbage Crisis.” Garbage and Recycling: Opposing Viewpoints. Ed. Helen Cothran. San Diego: Greenhaven, 2003. 20-27.

References to books should include the publication date of the original edition (given first) as well as the one cited.

The Hopkins Press Journals Ethics and Malpractice Statement can be found at the ethics-and-malpractice page.

Bookbird Peer Review

Bookbird: A Journal of International Children's Literature (ISSN 0006 7377) is a refereed quarterly journal publication of the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY). Bookbird accepts submissions of original scholarly articles focused on issues that are relevant to the field of children's literature and have an international perspective. Articles that compare literatures from different countries are of interest, as are papers on translation studies and articles that discuss the reception of work from one country in another. Articles concerned with a particular national literature or a particular book or writer may also be suitable, but it is important that the article should be of interest to an international audience and written without assuming excessive background information. Bookbird also includes themed issues for which the editor will post calls for manuscripts on the IBBY website. Submitted articles should not exceed 4,000 words, and should include an abstract of 150–200 words. Material submitted to Bookbird must be original and must not be under submission elsewhere.

Bookbird uses double-blind peer review. Authors submit their piece to the editor(s), and upon initial submission the editor(s) read the article and decide on whether it should be sent out for review. Having passed preliminary editorial review, all articles are sent to expert peer reviewers in a double-blind process (reviewers do not know the identity of the author, and the author is not informed of the identity of the reviewers). Reviewers return their reports within 3–4 weeks recommending one of the following:

- Accept as is

- Accept with minor revisions

- Accept with major revisions

- Revise & resubmit

The reviews are advisory and the editors reserve the right not to follow a reviewer’s recommendation or even to find another reviewer if they deem a given review unacceptable. For “Revise & Resubmit” the authors are encouraged to resubmit within the next three months. If an article is accepted with minor or major changes, the authors have three weeks to revise and submit their improved articles. The editors then review the revised articles and make final decisions. Accepted articles are copyedited and are returned to authors for proofreading two weeks later. Authors have a week to respond. Articles are published approximately four weeks later.

Criteria for review, both by the editors and the reviewers, are:

- Is the paper relevant to the scholarship of international children’s literature?

- Does the paper present original ideas or results supported by evidence and argument?

- Is it innovative in any way?

- Is the paper well supported by the citation of existing, up-to-date literature?

- Are the citations listed fully and accurately?

- Are the methodologies, designs and/or theories used in the article appropriate and successfully used?

- Is the paper clear, concise, complete, and well-written?

Postcards Editor

Anamaria Anderson

Editorial Review Board

Nicola Daly, University of Waikato (New Zealand) Debra Dudek, Edith Cowan University (Australia); Peter E. Cumming, York University (Canada) Roxanne Harde, University of Alberta (Canada) Anto Thomas Chakramakkil, St. Thomas College, Kerala (India) Judith Inggs, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (South Africa) Holly Johnson, University of Cincinnati (USA) Ingrid Johnston, University of Alberta (Canada) Mateusz Świetlicki, University of Wrocław (Poland) Aline Frederico, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) Yasmine Motawy, The American University in Cairo (Egypt) Beatriz Alcubierre Moya, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos (México) Jamie Campbell Naidoo, University of Alabama (USA) Keith O’Sullivan, Dublin City University (Ireland) Farideh Pourgiv, Shiraz University Center for Children’s Literature Studies (Iran) Sharifah Aishah Osman, University Malaya (Malaysia) Björn Sundmark, Malmö University (Sweden) Petros Panaou, University of Georgia (USA) Andrea Mei-Ying Wu, National Cheng Kung University (Taiwan) Andrea Casals Hill, Pontifica Universidad Catolica de Chile (Chile)

Abstracting & Indexing Databases

- Emerging Sources Citation Index

- Web of Science

- Biography Index: Past and Present (H.W. Wilson), vol.26, 1988-vol.49, no.2, 2011

- Book Review Digest Plus (H.W. Wilson), Mar.2004-

- Current Abstracts, 7/1/2003-12/31/2008

- Library & Information Science Source, 7/1/2003-12/31/2008

- Library Literature & Information Science Full Text (H.W. Wilson), 01/01/1984-

- Library Literature & Information Science Index (H.W. Wilson), 1/1/1984-10/1/2011

- Library Literature & Information Science Retrospective: 1905-1983 (H.W. Wilson), 1/4/1967-1/6/1982

- Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts (LISTA), 7/1/2003-12/31/2008

- Literary Reference Center, 1/1/2007-12/31/2008

- Literary Reference Center Plus, 1/1/2007-12/31/2008

- MLA International Bibliography (Modern Language Association)

- OmniFile Full Text Mega (H.W. Wilson), 10/2/2011-

- Poetry & Short Story Reference Center, 7/1/2003-12/31/2008

- TOC Premier (Table of Contents), 7/1/2003-12/31/2008

- Book Review Index Plus

- Gale Academic OneFile

- Gale Academic OneFile Select, 03/1993-03/2016

- Gale General OneFile, 03/1993-03/2016

- Gale OneFile: Information Science, 03/1993-03/2016

- InfoTrac Custom, 3/1993-3/2016

- ArticleFirst, vol.31, no.1, 1993-vol.49, no.4, 2011

- Electronic Collections Online, vol.46, no.1, 2008-vol.49, no.4, 2011

- Library Literature, vol.22, no.2, 1984-vol.48, no.4, 2010

- Education Collection, 1/1/1998-

- Education Database, 1/1/1998-

- Library & Information Science Collection, 01/01/1998-

- Library Science Database, 01/01/1998-

- Professional ProQuest Central, 01/01/1998-

- ProQuest 5000, 01/01/1998-

- ProQuest 5000 International, 01/01/1998-

- ProQuest Central, 01/01/1998-

- ProQuest Professional Education, 01/01/1998-

- Research Library, 01/01/1998-

- Social Science Premium Collection, 01/01/1998-

Abstracting & Indexing Sources

- Children's Book Review Index (Active) (Print)

- Children's Literature Abstracts (Ceased) (Print)

Source: Ulrichsweb Global Serials Directory.

0.2 (2022) 0.3 (Five-Year Impact Factor) 0.00019(Eigenfactor™ Score) Rank in Category (by Journal Impact Factor): Note: While journals indexed in AHCI and ESCI are receiving a JIF for the first time in June 2023, they will not receive ranks, quartiles, or percentiles until the release of 2023 data in June 2024.

© Clarivate Analytics 2023

Published quarterly.

Readers include: The community of readers interested in children's books.

Bookbird does not publish print advertisements.

Online Advertising Rates (per month)

Promotion (400x200 pixels) - $281.00

Online Advertising Deadline

Online advertising reservations are placed on a month-to-month basis.

All online ads are due on the 20th of the month prior to the reservation.

General Advertising Info

For more information on advertising or to place an ad, please visit the Advertising page.

eTOC (Electronic Table of Contents) alerts can be delivered to your inbox when this or any Hopkins Press journal is published via your ProjectMUSE MyMUSE account. Visit the eTOC instructions page for detailed instructions on setting up your MyMUSE account and alerts.

Also of Interest

Benjamin Fraser, The University of Arizona

David L. Russell, Ferris State University; Karin E. Westman, Kansas State University; and Naomi J. Wood, Kansas State University

Linda Mahood, University of Guelph

Megan Corbin, West Chester University

Lisa Rowe Fraustino , Hollins University

Penny A. Pasque, The Ohio State University; Thomas F. Nelson Laird, Indiana University, Bloomington

Rosa Andújar, King's College London

Vasti Torres, Indiana University

Carine Bourget, University of Arizona

Joseph Michael Sommers, Central Michigan University

Nicholas Morrow Williams, Arizona State University

Kate Quealy-Gainer, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Georgia L. Irby, College of William & Mary

Mária Minich Brewer and Daniel Brewer, University of Minnesota

Hopkins Press Journals

Children's Literature Collections

Approaches to Research

- © 2017

- Keith O'Sullivan 0 ,

- Pádraic Whyte 1

School of English, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

School of English, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

- Presents the culmination of a two-year project on children’s books in Ireland, bringing together books published across five centuries

- Contributes to the critical resources available on children’s literature in collections, and specifically, in terms of collecting, librarianship, education, and children’s literature studies

- Offers a complex view of children’s literature collections by showing the varied approaches to researching collections.

Part of the book series: Critical Approaches to Children's Literature (CRACL)

6903 Accesses

12 Citations

6 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (13 chapters)

Front matter, introduction.

- Pádraic Whyte, Keith O’Sullivan

History and Canonicity

Instruction with delight: evidence of children as readers in eighteenth-century ireland from the collections of dublin city library and archive.

- Máire Kennedy

Irish Children’s Books 1696‒1810: Importation, Exportation and the Beginnings of Irish Children’s Literature

- Anne Markey

The Great Famine in Irish History Textbooks, 1900–1971

- Ciara Boylan

The Development of the Irish Immigrant Experience in Irish-American Children’s Literature 1850‒1900

- Ciara Gallagher

Author and Text

Time and the child: the case of maria edgeworth’s early lessons.

- Aileen Douglas

Picking Grandmamma’s Pockets

- Jarlath Killeen, Marion Durnin

From Superstition to Enchantment: The Evolution of T. Crofton Croker’s Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland

- Ciara Ní Bhroin

‘Firing for the Hearth’: Storytelling, Landscape and Padraic Colum’s The Big Tree of Bunlahy

Pádraic Whyte

Ideals and Institutions

Kildare place society and the beginnings of formal education in ireland.

- Susan M. Parkes

Homespun Books: Creating an Irish National Children’s Literature

- Julie Anne Stevens

The Puffin Story Books Phenomenon: Popularization, Canonization and Fantasy, 1941‒1979

- Keith O’Sullivan

Picturing Possibilities in Children’s Book Collections

- Valerie Coghlan

Back Matter

- Children's literature

- Archival studies

- Collections

- Irish Studies

- children's literature

- English literature

- history of literature

- twentieth century

About this book

This book provides scholars, both national and international, with a basis for advanced research in children’s literature in collections. Examining books for children published across five centuries, gathered from the collections in Dublin, this unique volume advances causes in collecting, librarianship, education, and children’s literature studies more generally. It facilitates processes of discovery and recovery that present various pathways for researchers with diverse interests in children’s books to engage with collections. From book histories, through bookselling, information on collectors, and histories of education to close text analyses, it is evident that there are various approaches to researching collections. In this volume, three dominant approaches emerge: history and canonicity, author and text, ideals and institutions. Through its focus on varied materials, from fiction to textbooks, this volume illuminates how cities can articulate a vision of children's literature through particular collections and institutional practices.

Editors and Affiliations

Keith O'Sullivan

About the editors

Keith O’Sullivan is Lecturer in English at the Church of Ireland College of Education, Dublin, Ireland. He recently co-edited Children’s Literature and New York City (2014) and Irish Children’s Literature and Culture: New Perspectives on Contemporary Writing (2011). In 2013, he was co-recipient of a major Government of Ireland/Irish Research Council award to establish a National Collection of Children’s Books.

Pádraic Whyte is Assistant Professor of English and a director of the master’s programme in Children's Literature at the School of English, Trinity College Dublin. He is author of Irish Childhoods (2011) and co-editor of Children's Literature and New York City (2014). He was co-recipient of a major Irish Research Council/Government of Ireland award to establish a National Collection of Children’s Book.

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : Children's Literature Collections

Book Subtitle : Approaches to Research

Editors : Keith O'Sullivan, Pádraic Whyte

Series Title : Critical Approaches to Children's Literature

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-59757-1

Publisher : Palgrave Macmillan New York

eBook Packages : Literature, Cultural and Media Studies , Literature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017

Hardcover ISBN : 978-1-137-60311-1 Published: 20 May 2017

Softcover ISBN : 978-1-349-93406-5 Published: 29 October 2020

eBook ISBN : 978-1-137-59757-1 Published: 19 May 2017

Series ISSN : 2753-0825

Series E-ISSN : 2753-0833

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : X, 261

Topics : Children's Literature , European Literature , British and Irish Literature , Twentieth-Century Literature , Literary History

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Church Life Journal

A Journal of the McGrath Institute for Church Life

- Home ›

The Original Vision: Edward Robinson and the Spiritual Life of Children

by Daniel McClain May 27, 2024

The moments of happiness—not the sense of well-being, Fruition, fulfilment, security or affection, Or even a very good dinner, but the sudden illumination— We had the experience but missed the meaning, And approach to the meaning restores the experience In a different form . . . —T. S. Eliot, Four Quartets

A few years ago, I was in Denver visiting with Jerome Berryman , creator of a well-known Montessori-based children’s catechesis program known as "Godly Play." We had begun corresponding a couple years earlier because I had been teaching a course on children’s literature and theology at my university, and had adapted it for a seminary audience. Dr. Berryman discovered somehow that I incorporated Godly Play resources in my teaching. An online conversation led to an invitation to travel to Colorado. Before long, I was en route .

Jerome keeps a library and archive near his home. Like all academics, Jerome’s pride in his book collection was evident. We lingered amongst the shelves. Maria Montessori, Sofia Cavaletti, and other members of Montessori’s inner circle are all there. Jerome sparkled as he recounted his own training at the Montessori School in Bergamo, Italy. We talked about Heidegger, Rowan Williams, Pope Benedict XVI, poetry, and history.

He casually handed me a book and asked me if I knew it. That book was Edward Robinson’s The Original Vision . Always one to jump on good book recommendations, I snapped up a copy of The Original Vision , an American edition published by Seabury Press in 1978.

The Religious Experience Research Unit

Edward Robinson, the younger brother of the controversial English bishop, John A. T. Robinson, was an English educator, botanist, sculptor, and researcher. The son and nephew of well-known priests in the Church of England, Edward read classics at Oxford and began his career as an educator in former English colonies on the African continent, where for fifteen years he collected numerous specimens of grasses, discovering and naming several species (fifteen of which are named after him), some of which are housed at Kew Gardens . Robinson was known to have one of the largest personal collections of grasses in the world.

About three years after Robinson returned to England, he received an invitation to join a new research program at Oxford University, called the Religious Experience Research Unit (RERU). Founded just a year before, the RERU was the brainchild of Sir Alister Hardy, a marine biologist with a voracious intellectual appetite and an artistic temperament. [1]

In 1963-64, Hardy was invited to give the Gifford Lectures. “Evolution and the spirit of Man” (later published as The Living Stream and The Divine Flame ) challenges a purely material theory of evolution, and argues that religious/spiritual experience is a phenomenon tied to reality. Spiritual experiences are a natural part of human life.

What Sir Alister presented as a research interest in the early sixties became a research project by 1969, collecting and analyzing responses to his invitation to the British public to answer the question: “Have you ever experienced a presence or power, whether you call it God or not, which is different from your everyday self?”

Hardy described his team as “naturalists hunting specimen of human existence . . . anthropologists in our own society—indeed, of course, the anthropologists are the naturalists of mankind.” [2] Their question ultimately generated around 6000 responses, 400 of which were processed by the RERU research staff between 1970 and 1977. Today that data is held in an archive at the Sir Alister Hardy Trust Religious Experience Research Centre at the University of Wales Trinity St. David. In 1985, Sir Alister received the John Templeton Prize for his work in religious research.

Edward Robinson

Edward Robinson joined the RERU in 1970, invited by Hardy himself, who was drawn to what he and Robinson shared in common: a propensity to scientific classification as well as a curious amalgam of capacities in religion, education, and botany. Within seven years Hardy had stepped down as Director, and Robinson took the helm.

During his first seven years at the RERU, prior to his appointment as Director, Robinson combed through, classified, and published findings related to the initial 4000 responses to Sir Alister’s question. Throughout this first phase of his work, he noticed something remarkable in the data. He recounts, “Some 15% of our correspondents . . . started by going back to events and experiences of their earliest years.” [3] That 600 respondents narrated meaningful experiences of a religious, spiritual, or mystical nature in early childhood is significant, Robinson clarifies, because it bucks the received canonical understanding of a transition from “childhood incompetence to the adult ability to give correct solutions.” [4] The testimonies provoked Robinson: “I began to wonder whether there were not in quite young children capacities for insight and understanding that had been underrated by the developmental psychologists. Here it seemed might be a valuable source for information to complement the prevailing view.”

As he dug deeper into the initial testimonies collected by the RERU, simple complementarity became less tenable, not because Robinson wanted to reject developmentalism tout court , but because the a priori imposition of a chronological framework obscured what Robinson found most fascinating in the responses. Not only that, but Robinson notes that a developmental model would automatically raise questions about the validity or objectivity of a childhood memory simply because it was from childhood. [5] “How reliable . . . are such records? . . . How far can we really trust [a 50-year-old narrative, for instance] as a historical record?” [6]

For Robinson, however, the perduring quality of such a memory, the way it grounded and illuminated subsequent life experiences, thoughts, and values overrode historical concerns. [7] The question is not whether the knowledge of childhood is objectively correct, but whether for the knower it is certain. “She may have been wrong, but the idea never entered her head, either at the time [whilst a child] or subsequently.” [8] Moreover, Robinson points out that questions of historical veracity only attends to one aspect of an adult’s ongoing experience and misses what he refers to as an everyday, ongoing process, initiated by “childhood,” and in which religious experience is not, typically, a rare and dramatic thing, but “really quite ordinary.” [9]

Critiquing Developmentalism

Robinson believed that developmental psychology, however valuable for its introduction of epistemology and clinical observation to the psychological process with children, could not comprehend the role that childhood religious experience played in the lives of his adult respondents. Fundamental to his critique, Robinson saw an implicit bias in Piaget and his heirs, and one that continued to plague education. “Piaget,” he accuses,

Is . . . continually setting children an exam in a subject that adults are good at and children bad. Predictably, the children fail . . . if children are really to be thought of as little more than inefficient adults, then the prime function of education is to turn them into efficient ones. [10]

Looking at testimonies of experiences as early as four or five years old, [11] he rejected psychological commitments like Ronald Goldman’s “negative and patronizing” conclusion that “religious insight generally begins to appear between the ages of 12 and 13.” [12] Piaget and Goldman prized the acquisition of analytic thinking, which Piaget located in the formal operational stage, beginning as early as 11 years old. Goldman himself made analysis an epistemological prerequisite for religious experience. Robinson pushed back on all this: analytic thought does not undo the immediacy or solidity of childhood experiences, at whatever age, or even the ways they continue to shape the person.

Robinson pressed against this solipsistic, isolated, and cognitively overdetermined understanding, as if religious experience is merely self-revelation or the revelation of an abstract God. Instead, these experiences are “immediate” and “unquestionably real” experiences of “something real” outside of the child, experiences that constitute a “self-authenticating” “original vision” that informs the self through adulthood. [13]

What I began to see emerging from Robinson’s critique of this epistemologically overdetermined theory of childhood was twofold: 1) the relationship between forms of knowledge and religious experience needed to be entirely rethought; and 2) religious experience is perhaps so commonplace in children that we who look for the spectacular might be overlooking the actual religious lives of children. Robinson’s constructive proposal would shift the narrative completely, and would reframe the relationship of childhood to personhood.

Mystery & Synthesis

Robinson saw a mysterious quality of childhood that sequential thinking was not able to see. “Unless we think purely in chronological terms, childhood can never be a simple concept.” [14]

Robinson’s initial data set, as well as the qualitative value of the testimonies themselves, gave him what he needed to look for an alternative to developmentalism. Robinson issued nine additional questions to “about 500” respondents, 360 of which responded (the questions and data analysis are all included as appendices). [15]

The result of this additional study led to The Original Vision , which is not only a theoretical alternative, but an interpretation of the RERU’s in-depth study and the additional questionnaire. Robinson classifies the additional 360 responses into nine kinds of experience, or ways of getting into the experience of childhood.

In summary, Robinson argues that childhood is a “ self-authenticating . . . form of knowledge,” akin to “mystical” experience (although he takes issue with how vague that word can be), that must be studied over time as a “natural” and “ religious ” phenomenon, “in purposive terms,” and with “sympathetic insight.” [16] By self-authenticating, Robinson distinguished between self-authorizing and self-aware, and embraced both. First, the experience of childhood that is retrieved in reflection needs no external confirmation for it to hold authority in the person’s life. Second, the experience “bring[s] to the person . . . an awareness of the true self as individual.” [17]

The bulk of The Original Vision is comprised not of Robinson’s analysis, but of the correspondents’ testimonies. These first-hand accounts are disarming and raw. Often, there is an immediacy to them, as if the correspondent is relaying an experience that happened days or weeks ago, rather than decades.

One of the first accounts that Robinson shares comes from an interview that he conducted. The interviewee recounts a sense of certainty in his experience along the lines of the first sense of self-authentication. He says,

From my present age, looking back some half a century, I would say now that I did then experience—what? a truth, a fact, the existence of the divine. What happened was telling me something. But what was it telling? The fact of divinity, that it was good? Not so much the moral sense, but that it was beautiful, yes, sacred. [18]

Here we see that the interviewee is not so much caught in the reverie of make-believe (a la Piaget’s pre-operational stage), but conscious of an experience of otherness and, indeed, beauty.

Importantly, the respondent admits to not having the linguistic capacity to convey his experience at the time. However, the sense of surety that arose in that moment remained with him, right up to the moment of the interview, “some half a century” later. If not linguistically mediated, whence this certainty? Robinson prods this question early and throughout the book, curious about what model of childhood can accommodate and respect these adults’ claims to some variety of real experience, experiences that Robinson maintains are more commonplace than esoteric.

Most respondents recall experiences that begin with quotidian activities or surroundings—walks, school, kitchens, shops, etc. A sixty-four-year-old woman talks about sitting in her mother’s lap at five years old, feeling sorry for her mother’s small-minded notions of God. [19] Another respondent, a forty-nine-year-old woman, recalls hating her mother and doctor for taking her tonsils out. [20] Men and women of all ages recall experiencing “otherness” and “individuation” and “flashes [of] awareness” at early ages amidst ordinary activities like walking to and from school or visiting their parents in workplaces, all experiences that developmental staging arguably preclude. [21] One respondent tells of her grammar school teacher’s invitation to practice the loving presence of Christ “who was above all a friend to children,” and how this invitation led to her certainty that she was understood. [22]

Whereas developmental thinking maintains the distinction between the fantastical, imaginative lives of young children and the practical, discursive, and analytical thinking of older children, Robinson is fascinated by the way that adults continue to ground their adult lives in the experiences, and even knowledge, of these early years. [23] “The great majority of those whose experience led me to this study are men and women in whom the original vision of childhood never faded.” [24] Of course, he acknowledges, this will be a problem for many. “Some may still feel it intolerably paradoxical to base a study of childhood on the records of those who have in years at least left it so far behind.” [25]

But where cynics see distance, Robinson posits something like the nutrient-rich soil of a garden. “To have attempted an assessment of the childhood experience of any of these writers at an earlier age would have been in some respects at least premature; that they would not yet have had their experience, or not yet had it sufficiently for a proper judgment to be made of it.” [26]

Without saying it explicitly, Robinson has articulated a vision of childhood that is not defined or delimited to years of a person’s life, but rather a “slow process” of reflection on a kind of knowledge, [27] stretched out over a life like a lens, not to obscure nature, but rather to more faithfully reveal it. “Metaphysics must start with personal experience.” [28] The vision of childhood is a vision that helps us see both the limits of our own seeing and infinite capaciousness beyond our personal experiences. “This significance of the insignificant is a theme central to the biblical, the Christian tradition. The still small voice, the grain of mustard seed, the one coin lost, the single sparrow dead—these are the stuff of which religious experience is made.” [29]

This concluding theme is captured rather powerfully near the middle of the book by one respondent, a forty-five-year-old woman.

I think I have been simply trying, in adult life, to grow towards the vision of childhood, and to comprehend more fully the significance of the light which was so interwoven into those early years. The original impact of light was so powerful that my inner world still reverberates with it. Later logic chopping, analysis and interpretation have in no way diminished the immediacy of that impact. Very importantly: this same consciousness of light has proved to be translatable as the light of common day living. In my own extremis, I have tried to remember the light and stand by it. [30]

Developmental thinking alone cannot comprehend childhood as Robinson saw it expressed in the lasting influence of his correspondents’ ongoing experience of their own childhood. The analysis of childhood testimony of religious experience in The Original Vision is eye-opening to those who may have adopted a certain kind of model of childhood that is dependent on development or injury. Instead of childhood as a developmental phase [31] or symbolizing a traumatic repression or recovery, [32] we see emerge from the first-hand testimony of these responses a vision of childhood that provides adulthood with the possibility of an integrated, mature wholeness.

The Original Vision provides a starting point by framing childhood as a “synthetic comprehension” that is not destroyed by the later acquisition of analytic thinking. Rather, it remains as a holistic knowledge that makes possible the condition of other kinds of knowledge throughout life.

It is unfortunate that aside from several reviews and scattered mention in few articles, The Original Vision has faded into obscurity. A study similar to Robinson’s was undertaken by Edward Hoffman. [33] Yet, developmental thinking continues to dominate the way we treat childhood, if not in the academy then at least in popular thinking and practice.

Robinson’s observation of adult testimony of childhood experience bids us to ask, “What happens, or what is gained in childhood that makes it possible to tell our stories as adults?” A fulsome answer to this question depends on our ability to see the enduring power of childhood throughout the entirety of human life.

[1] Like many naturalists, Hardy was artistic in skill and imagination. During WWII, Hardy’s army career consisted in designing camouflage patterns.

[2] Hardy, “Forward,” in Robinson, The Original Vision , 4.

[3] Robinson, The Original Vision , 11.

[4] The Original Vision, 10.

[5] For a “genetic epistemologist” like Piaget, a childhood memory lacks credibility because of its non-clinical origin but also because most of memories collected by the RERU come from the pre-operational stage (two to seven years old). In the pre-operational stage, a child lacks the concrete reasoning to be able to distinguish between symbol and reality, or to abstract the symbol as representative of concepts. Robinson’s respondents, on the other hand, claimed to have experiences while in the age range of the pre-operational stage, and to be able to distinguish their experiences from symbolic make-believe, and arrived at conceptual outcomes.

[6] The Original Vision, 13. Cf. Robinson, This Timebound Ladder: Ten Dialogues on Religious Experience (Oxford: The Religious Experience Research Unit, 1977), 71-72.

[7] The Original Vision, 23: “The possibility that there is something here that must be taken serious is clearly felt as some kind of threat; to question the authenticity of the records is the first and most obvious defense.”

[8] The Original Vision, 20.

[9] The Original Vision, 15.

[10] The Original Vision , 10.

[11] The Original Vision, 11. On studying the first hand accounts, “I began to wonder whether there were not in quite young children capacities for insight and understanding that had been underrated by the developmental psychologists.”

[12] Goldman, Religious Thinking from Childhood to Adolescence (Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1964), 226, cited in The Original Vision , 11.

[13] The Original Vision, 16 and 22.

[14] The Original Vision, 15.

[15] The Original Vision , 157-71.

[16] The Original Vision, 16. All emphases original unless otherwise noted.

[17] The Original Vision, 16.

[18] The Original Vision, 35.

[19] The Original Vision , 69.

[20] The Original Vision , 111.

[21] The Original Vision , 113-15.

[22] The Original Vision , 84.

[23] The Original Vision, 19.

[24] The Original Vision , 148.

[25] The Original Vision , 144.

[26] The Original Vision, 145.

[27] The Original Vision , 145.

[28] The Original Vision, 146.

[29] The Original Vision, 147.

[30] The Original Vision, 55.

[31] Cf. Jean Piaget, “The theory of stages in cognitive development,” in D. R. Green, M. P. Ford, & G. B. Flamer, Measurement and Piaget (McGraw-Hill, 1971), and Piaget, The Child’s Conception of the World, tr. J. & A. Tomlinson (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1929), 62, cited in Robinson, The Original Vision, 9-10.

[32] Cf. Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle . Childhood gives rise in the adult to an “unpleasurable tension” that originates in a traumatic neurosis which is a repressed memory of a childhood event.

[33] See Hoffman, Visions of Innocence: Spiritual and Inspirational Experiences of Childhood (Boston: Shambhala, 1992).

Featured Image: Ludwik Stasiak, Nun Praying with Children, before 1924; Source: Wikimedia Commons, PD-Old-70.

Daniel McClain

Dan McClain holds a PhD in Historical and Systematic Theology from the Catholic University of America, and previously taught theology at the General Theological Seminary (NYC) and Loyola University Maryland. Dan's current areas of expertise and interest include children and children's literature, theological education and formation, and the relationship between church practice and doctrine.

Read more by Daniel McClain

Reading Children's Literature After the Tragedy of School Shootings

June 27, 2022 | LuElla D’Amico

Newsletter Sign up

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

‘Star Trek’ actor George Takei is determined to keep telling his Japanese American story

“Star Trek” icon George Takei has a new picture book out for children ages called “My Lost Freedom,” tackling the incarceration of 120,000 Japanese Americans, including children, labeled enemies during World War II. (May 30)

FILE - Members of the “Star Trek” crew, from left, James Doohan, DeForest Kelley, Walter Koenig, William Shatner, George Takei, Leonard Nimoy and Nichelle Nichols, toast the newest “Star Trek” film during a news conference at Paramount Studios in Los Angeles, Dec. 28, 1988. (AP Photo/Bob Galbraith, File)

- Copy Link copied

FILE - Actor George Takei, who played the role of helm officer Sulu in the original television series, “Star Trek,” gives a “live long and prosper” gesture in front of a model of the U.S.S. Enterprise space ship at an exhibit at the Tech Museum in San Jose, Calif., on Oct. 20, 2009. (AP Photo/Paul Sakuma, File)

FILE - George Takei arrives at the 75th annual Tony Awards on June 12, 2022, at Radio City Music Hall in New York. (Photo by Evan Agostini/Invision/AP, File)

FILE - George Takei arrives at the Star Trek Day celebration in Los Angeles on Sept. 8, 2021. (Photo by Richard Shotwell/Invision/AP, File)

A copy of “My Lost Freedom,” a children’s book by George Takei, is displayed at the section featuring in the “Being Asian in America” at a Kinokuniya bookstore specializing in selling books and magazines written in foreign languages in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo, Wednesday, May 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Hiro Komae)

TOKYO (AP) — The incarceration of 120,000 Japanese Americans , including children, labeled enemies during World War II is an historical experience that has traumatized, and galvanized, the Japanese American community over the decades.

For George Takei, who portrayed Hikaru Sulu aboard the USS Enterprise in the “Star Trek” franchise, it’s a story he is determined to keep telling every opportunity he has.

“I consider it my mission in life to educate Americans on this chapter of American history,” he said in a recent interview with The Associated Press.

He fears the lesson about the failure of U.S. democracy hasn’t really been learned, even today, including among Japanese Americans.

“The shame of internment is the government’s. They’re the ones that did something unjust, cruel and inhuman. But so often the victims of the government actions take on the shame themselves,” he said.

Takei, 87, has a new picture book out for children ages 6 to 9 and their parents, called “My Lost Freedom.” It’s illustrated in soft watercolors by Michelle Lee.

Takei was 4 years old when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942, two months after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor , declaring anyone of Japanese descent an enemy of the United States and forcibly removing them from their West Coast homes.

Takei spent the next three years behind barbed wires, guarded by soldiers with guns, in three camps: the Santa Anita racetrack, which stunk of manure; Camp Rohwer in a marshland; and, from 1943, Tule Lake, a high-security segregation center for the “disloyal.”

“We were seen as different from other Americans. This was unfair. We were Americans, who had nothing to do with Pearl Harbor. Yet we were imprisoned behind barbed wires,” Takei writes in the book.

Throughout it all, his parents are portrayed as enduring the hardships with a quiet dignity. His mother sewed clothes for the children. They made chairs out of scrap lumber. They played baseball. They danced to Benny Goodman. For Christmas, they got a Santa who looked Japanese.

Takei’s is a remarkable story of resilience and a pursuit of justice, repeated throughout the Japanese American experience.

It’s a story that’s been told and retold, in books like the 1973 “Farewell to Manzanar” by Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston; “Only What We Could Carry,” edited by Lawson Fusao Inada more than 20 years ago; and “The Literature of Japanese American Incarceration,” which just came out, compiled by Frank Abe and Floyd Cheung.

David Inoue, executive director of the Japanese American Citizens League, headquartered in Washington, D.C., believes the message of Takei’s book remains relevant.

He said discrimination persists today, as seen in the anti-Asian attacks that flared with the COVID-19 pandemic . Inoue said his son has been taunted in school in the same way he was growing up.

“One of the important things about having books like this is that it humanizes us. It tells stories about us that show we’re just like any other family. We like to play baseball. We have pets,” Inoue said.

Takei and his family were sent to Tule Lake in northern California because his parents answered “No” to key questions in a so-called loyalty questionnaire.

Question No. 27 asked if they were willing to serve in the U.S. armed forces. Question No. 28 asked whether they swore allegiance to the U.S. and would forswear allegiance to the Japanese emperor. Both were controversial questions for people who had been stripped of their basic civil rights and labeled enemies.

“Daddy and Mama both thought that the two questions were stupid,” Takei writes in “My Lost Freedom.”

“The only honest answers were No and No.”

Takei said the questions did not explain what would become of families with young children. The second question was also a no-win, he said, because his parents felt there was no loyalty to Japan to denounce.

Tule Lake was the largest of the 10 camps, holding 18,000 people.

Young men who answered “Yes” became part of the all-Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which fought in Europe while their families remained incarcerated. The 442, with their famous “Go for Broke” motto, is the most decorated unit of its size and length of service in U.S. military history.

“They were determined to prove themselves and get their families out of barbed wires,” Takei said. “They are our heroes. I know I owe so much to them.”

After Japan surrendered, Takei and his family, like all Japanese Americans freed from the camps , were each given $25 and a one-way ticket to anywhere in the U.S. Takei’s family chose to start all over again in Los Angeles.

In 1988, the Civil Liberties Act — after years of effort and testimonies by Japanese Americans, including Takei — granted redress of $20,000 and a formal presidential apology to every surviving U.S. citizen or legal resident immigrant of Japanese ancestry incarcerated during World War II.

Takei’s voice became choked when he recalled how his father did not live to see it.