What is the i+1 Principle?

Posted by: Phil Western at 10:00 am, July 21, 2020

“i+1” (Input Hypothesis) was originally a theory of learning developed by the linguist Stephen Krashen in the 1970s. It basically says that learning is most effective when you meet the learners’ current level and add one level of difficulty, like the next rung on a ladder. As a language teacher I always found this defined the whole process. The language of the classroom is kept just above the learners’ level, rather than hitting them with the whole dictionary straight away. But we’re talking about more than just language here, this applies to anything you decide to do.

How do I use the i+1 Principle?

I have started using the term in relation to motivation for literally anything. Another term, “comfort zone”, has been much overused, but it definitely applies here. With a language, if you keep on using basic parrot phrases for years, you’ll never get anywhere. You need to push out a bit, make a few mistakes, see some confused faces, get the wrong food order a couple of times – and then you get it. People who don’t like leaving that comfort zone don’t tend to learn. With motivation, as with language, people who don’t push out a bit don’t tend to succeed.

If you want to learn more about determination and the will to succeed, check out my article on Angela Duckworth’s fantastic book, Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance, here: https://www.philwestern.blog/2020/07/16/grit-do-you-have-it/

The Problems

It’s really hygge in the comfort zone. If you feel like life is boring, ask yourself when the last time you were actually uncomfortable was. Without discomfort, there is no true success. The i+1 principle will get you that.

We tend to look at people doing something really well and see it as a fait accompli, or an innate gift, and not an expression of years of tireless work. Hendrix was just talented, right? Mozart was simply a genius. But what about the 8 hours of practice a day that Jimi did? And don’t believe what you saw in the film Amadeus . Putting it all down to talent takes the credit away a bit, doesn’t it? Raw talent definitely helps, but hard work wins out, every time.

Not Looking at the Whole Challenge

So, don’t focus too much on absolute mastery of a given challenge. Rather, break it down into bitesize chunks. Look at where you are as honestly as you can, and just add 1 difficulty point. For the beginner linguist, this means not messing up the restaurant order again, for the guitarist it’s getting that B diminished barre chord nailed. Maybe for you it’s just trying the challenge you’re a little uncomfortable with (without breaking a leg, or setting yourself on fire).

Perhaps Muhammad Ali said it best: I have learned to live my life one step, one breath, and one moment at a time, but it was a long road. I set out on a journey of love, seeking truth, peace and understanding. I am still learning.

See more by Phil Western

Hi, my name's Phil. I am a Content Writer and Producer. My background is a mixture of education, social media and management. I've spent a lot of my career working in Latin America and Spain, and I have a love for languages and education. I also have my own blogsite: http://www.philwestern.blog/

- Heritage Sites Worth A Visit July 21, 2020

- What Is The God Particle? July 21, 2020

- What Is VARK? July 21, 2020

Stay Connected

Introduction The Acquisition-Learning Hypothesis The Natural Order Hypothesis The Monitor Hypothesis The Input Hypothesis The Affective Filter Hypothesis Curriculum Design Conclusions Bibliography

Introduction The influence of Stephen Krashen on language education research and practice is undeniable. First introduced over 20 years ago, his theories are still debated today. In 1983, he published The Natural Approach with Tracy Terrell, which combined a comprehensive second language acquisition theory with a curriculum for language classrooms. The influence of Natural Approach can be seen especially in current EFL textbooks and teachers resource books such as The Lexical Approach (Lewis, 1993). Krashens theories on second language acquisition have also had a huge impact on education in the state of California, starting in 1981 with his contribution to Schooling and language minority students: A theoretical framework by the California State Department of Education (Krashen 1981). Today his influence can be seen most prominently in the debate about bilingual education and perhaps less explicitly in language education policy: The BCLAD/CLAD teacher assessment tests define the pedagogical factors affecting first and second language development in exactly the same terms used in Krashens Monitor Model (California Commission on Teacher Credentialing, 1998). As advertised, The Natural Approach is very appealing who wouldnt want to learn a language the natural way, and what language teacher doesnt think about what kind of input to provide for students. However, upon closer examination of Krashens hypotheses and Terrells methods, they fail to provide the goods for a workable system. In fact, within the covers of The Natural Approach, the weaknesses that other authors criticize can be seen playing themselves out into proof of the failure of Krashens model. In addition to reviewing what other authors have written about Krashens hypotheses, I will attempt to directly address what I consider to be some of the implications for ES/FL teaching today by drawing on my own experience in the classroom as a teacher and a student of language. Rather than use Krashens own label, which is to call his ideas simply second language acquisition theory, I will adopt McLaughlins terminology (1987) and refer to them collectively as the Monitor Model. This is distinct from the Monitor Hypothesis, which is the fourth of Krashens five hypotheses. The Acquisition-Learning Hypothesis First is the Acquisition-Learning Hypothesis, which makes a distinction between acquisition, which he defines as developing competence by using language for real communication and learning. which he defines as knowing about or formal knowledge of a language (p.26). This hypothesis is presented largely as common sense: Krashen only draws on only one set of references from Roger Brown in the early 1970s. He claims that Browns research on first language acquisition showed that parents tend to correct the content of childrens speech rather than their grammar. He compares it with several other authors distinction of implicit and explicit learning but simply informs the reader that evidence will be presented later. Gregg (1984) first notes that Krashens use of the Language Acquisition Device (LAD) gives it a much wider scope of operation than even Chomsky himself. He intended it simply as a construct to describe the childs initial state, which would therefore mean that it cannot apply to adult learners. Drawing on his own experience of learning Japanese, Gregg contends that Krashens dogmatic insistence that learning can never become acquisition is quickly refuted by the experience of anyone who has internalized some of the grammar they have consciously memorized. However, although it is not explicitly stated, Krashens emphasis seems to be that classroom learning does not lead to fluent, native-like speech. Greggs account that his memorization of a verb conjugation chart was error-free after a couple of days(p.81) seems to go against this spirit. The reader is left to speculate whether his proficiency in Japanese at the time was sufficient enough for him to engage in error-free conversations with the verbs from his chart. McLaughlin (1987) begins his critique by pointing out that Krashen never adequately defines acquisition, learning, conscious and subconscious, and that without such clarification, it is very difficult to independently determine whether subjects are learning or acquiring language. This is perhaps the first area that needs to be explained in attempting to utilize the Natural Approach. If the classroom situation is hopeless for attaining proficiency, then it is probably best not to start. As we will see in an analysis of the specific methods in the book, any attempt to recreate an environment suitable for acquisition is bound to be problematic. Krashens conscious/unconscious learning distinction appeals to students and teachers in monolingual countries immediately. In societies where there are few bilinguals, like the United States, many people have struggled to learn a foreign language at school, often unsuccessfully. They see people who live in other countries as just having picked up their second language naturally in childhood. The effort spent in studying and doing homework seems pointless when contrasted with the apparent ease that natural acquisition presents. This feeling is not lost on teachers: without a theoretical basis for the methods, given any perceived slow progress of their students, they would feel that they have no choice but to be open to any new ideas Taking a broad interpretation of this hypothesis, the main intent seems to be to convey how grammar study (learning) is less effective than simple exposure (acquisition). This is something that very few researchers seem to doubt, and recent findings in the analysis of right hemisphere trauma indicate a clear separation of the facilities for interpreting context-independent sentences from context-dependent utterances (Paradis, 1998). However, when called upon to clarify, Krashen takes the somewhat less defensible position that the two are completely unrelated and that grammar study has no place in language learning (Krashen 1993a, 1993b). As several authors have shown (Gregg 1984, McLaughlin 1987, and Lightbown & Pienemann 1993, for a direct counter-argument to Krashen 1993a) there are countless examples of how grammar study can be of great benefit to students learning by some sort of communicative method. The Natural Order Hypothesis The second hypothesis is simply that grammatical structures are learned in a predictable order. Once again this is based on first language acquisition research done by Roger Brown, as well as that of Jill and Peter de Villiers. These studies found striking similarities in the order in which children acquired certain grammatical morphemes. Krashen cites a series of studies by Dulay and Burt which show that a group of Spanish speaking and a group of Chinese speaking children learning English as a second language also exhibited a natural order for grammatical morphemes which did not differ between the two groups. A rather lengthy end-note directs readers to further research in first and second language acquisition, but somewhat undercuts the basic hypothesis by showing limitations to the concept of an order of acquisition. Gregg argues that Krashen has no basis for separating grammatical morphemes from, for example, phonology. Although Krashen only briefly mentions the existence of other parallel streams of acquisition in The Natural Approach, their very existence rules out any order that might be used in instruction. The basic idea of a simple linear order of acquisition is extremely unlikely, Gregg reminds us. In addition, if there are individual differences then the hypothesis is not provable, falsifiable, and in the end, not useful. McLaughlin points out the methodological problems with Dulay and Burts 1974 study, and cites a study by Hakuta and Cancino (1977, cited in McLaughlin, 1987, p.32) which found that the complexity of a morpheme depended on the learners native language. The difference between the experience of a speaker of a Germanic language studying English with that of an Asian language studying English is a clear indication of the relevance of this finding. The contradictions for planning curriculum are immediately evident. Having just discredited grammar study in the Acquisition-Learning Hypothesis, Krashen suddenly proposes that second language learners should follow the natural order of acquisition for grammatical morphemes. The teacher is first instructed to create a natural environment for the learner but then, in trying to create a curriculum, they are instructed to base it on grammar. As described below in an analysis of the actual classroom methods presented in the Natural Approach, attempting to put these conflicting theories into practice is very problematic. When one examines this hypothesis in terms of comprehension and production, its insufficiencies become even more apparent. Many of the studies of order of acquisition, especially those in first language acquisition, are based on production. McLaughlin also points out that correct usage is not monolithic even for grammatical morphemes, correct usage in one situation does not guarantee as correct usage in another (p.33). In this sense, the term acquisition becomes very unclear, even when not applying Krashens definition. Is a structure acquired when there are no mistakes in comprehension? Or is it acquired when there is a certain level of accuracy in production? First language acquisition is very closely linked to the cognitive development of infants, but second language learners have most of these facilities present, even as children. Further, even if some weak form of natural order exists for any learners who are speakers of a given language, learning in a given environment, it is not clear that the order is the same for comprehension and production. If these two orders differ, it is not clear how they would interact. The Monitor Hypothesis The role of conscious learning is defined in this somewhat negative hypothesis: The only role that such learned competence can have is an editor on what is produced. Output is checked and repaired, after it has been produced, by the explicit knowledge the learner has gained through grammar study. The implication is that the use of this Monitor should be discouraged and that production should be left up to some instinct that has been formed by acquisition. Using the Monitor, speech is halting since it only can check what has been produced, but Monitor-free speech is much more instinctive and less contrived. However, he later describes cases of using the Monitor efficiently (p. 32) to eliminate errors on easy rules. This hypothesis presents very little in the way of supportive evidence: Krashen cites several studies by Bialystok alone and with Frohlich as confirming evidence (p.31) and several of his own studies on the difficulty of confirming acquisition of grammar. Perhaps Krashens recognition of this factor was indeed a step forward language learners and teachers everywhere know the feeling that the harder they try to make a correct sentence, the worse it comes out. However, he seems to draw the lines around it a bit too closely. Gregg points (p.84) out that by restricting monitor use to learned grammar and only in production, Krashen in effect makes the Acquisition-Learning Hypothesis and the Monitor Hypothesis contradictory. Gregg also points out that the restricting learning to the role of editing production completely ignores comprehension (p.82). Explicitly learned grammar can obviously play a crucial role in understanding speech. McLaughlin gives a thorough dissection of the hypothesis, showing that Krashen has never demonstrated the operation of the Monitor in his own or any other research. Even the further qualification that it only works on discrete-point tests on one grammar rule at a time failed to produce evidence of operation. Only one study (Seliger, cited on p.26) was able to find narrow conditions for its operation, and even there the conclusion was that it was not representative of the conscious knowledge of grammar. He goes on to point out how difficult it is to determine if one is consciously employing a rule, and that such conscious editing actually interferes with performance. But his most convincing argument is the existence of learners who have taught themselves a language with very little contact with native speakers. These people are perhaps rare on the campuses of U.S. universities, but it is quite undeniable that they exist. The role that explicitly learned grammar and incidentally acquired exposure have in forming sentences is far from clear. Watching intermediate students practice using recasts is certainly convincing evidence that something like the Monitor is at work: even without outside correction, they can eliminate the errors in a target sentence or expression of their own ideas after several tries. However, psycholinguists have yet to determine just what goes into sentence processing and bilingual memory. In a later paper (Krashen 1991), he tried to show that high school students, despite applying spelling rules they knew explicitly, performed worse than college students who did not remember such rules. He failed to address not only the relevance of this study to the ability to communicate in a language, but also the possibility that whether they remembered the rules or not, the college students probably did know the rules consciously at some point, which again violates the Learning-Acquisition Hypothesis. The Input Hypothesis Here Krashen explains how successful acquisition occurs: by simply understanding input that is a little beyond the learners present level he defined that present level as i and the ideal level of input as i +1. In the development of oral fluency, unknown words and grammar are deduced through the use of context (both situational and discursive), rather than through direct instruction. Krashen has several areas which he draws on for proof of the Input Hypothesis. One is the speech that parents use when talking to children (caretaker speech), which he says is vital in first language acquisition (p.34). He also illustrates how good teachers tune their speech to their students level, and how when talking to each other, second language learners adjust their speech in order to communicate. This hypothesis is also supported by the fact that often the first second language utterances of adult learners are very similar to those of infants in their first language. However it is the results of methods such as Ashers Total Physical Response that provide the most convincing evidence. This method was shown to be far superior to audiolingual, grammar-translation or other approaches, producing what Krashen calls nearly five times the [normal] acquisition rate. Gregg spends substantial time on this particular hypothesis, because, while it seems to be the core of the model, it is simply an uncontroversial observation with no process described and no proof provided. He brings up the very salient point that perhaps practice does indeed also have something to do with second language acquisition, pointing out that monitoring could be used as a source of correct utterances (p. 87). He also cites several studies that shed some doubt on the connection between caretaker speech in first language acquisition and simplified input in second language acquisition. McLaughlin also gives careful and thorough consideration to this part of Krashens model. He addresses each of the ten lines of evidence that Krashen presents, arguing that it is not sufficient to simply say that certain phenomenon can be viewed from the perspective of the Input Hypothesis. The concept of a learners level is extremely difficult to define, just as the idea of i +1 is (p.37). Further, there are many structures such as passives and yes/no questions that cannot be learned through context. Also, there is no evidence that a learner has to fully comprehend an utterance for it to aid in acquisition. Some of the first words that children and second language learners produce are formulaic expressions that are not fully understood initially. Finally McLaughlin points out that Krashen simply ignores other internal factors such as motivation and the importance of producing language for interaction. This hypothesis is perhaps the most appealing part of Krashens model for the language learner as well as the teacher. He makes use of the gap between comprehension and production that everyone feels, enticing us with the hope of instant benefits if we just get the input tuned to the right level. One of Krashens cleverest catch-alls is that other methods of teaching appear to work at times because they inadvertently provide this input. But the disappointment is that he never gives any convincing idea as to how it works. In the classroom a teacher can see when the students dont understand and can simplify his or her speech to the point where they do. Krashen would have the teacher think that this was all that is necessary, and it is just a matter of time before the students are able to express themselves freely. However, Ellis (1992) points out that even as of his 1985 work (Krashen 1985), he still had not provided a single study that demonstrated the Input Hypothesis. Over extended periods of time students do learn to understand more and even how to speak, but it often seems to take much longer than Krashen implies, indicating that there are perhaps many more factors involved. More importantly, even given this beginning of i, and the goal of i + 1, indefinable as they are, the reader is given no indication of how to proceed. As shown above the Natural Order Hypothesis holds no answers, especially as to how comprehension progresses. In an indication of a direction that should be explored, Elliss exploratory study (ibid.) showed that it is the effort involved in attempting to understand input rather than simple comprehension that fuels acquisition. The Affective Filter Hypothesis This concept receives the briefest treatment in The Natural Approach. Krashen simply states that attitudinal variables relate directly to language acquisition but not language learning. He cites several studies that examine the link between motivation and self-image, arguing that an integrative motivation (the learner want to be like the native speakers of a language) is necessary. He postulates an affective filter that acts before the Language Acquisition Device and restricts the desire to seek input if the learner does not have such motivation. Krashen also says that at puberty, this filter increases dramatically in strength. Gregg notes several problems with this hypothesis as well. Among others, Krashen seems to indicate that perhaps the affective filter is associated with the emotional upheaval and hypersensitivity of puberty, but Gregg notes that this would indicate that the filter would slowly disappear in adulthood, which Krashen does not allow for (p.92). He also remarks on several operational details, such as the fact that simply not being unmotivated would be the same as being highly motivated in this hypothesis neither is the negative state of being unmotivated. Also, he questions how this filter would selectively choose certain parts of a language to reject (p.94). McLaughlin argues much along the same lines as Gregg and points out that adolescents often acquire languages faster than younger, monitor-free children (p.29). He concludes that while affective variables certainly play a critical role in acquisition, there is no need to theorize a filter like Krashens. Again, the teacher in the classroom is enticed by this hypothesis because of the obvious effects of self-confidence and motivation. However, Krashen seems to imply that teaching children, who dont have this filter, is somehow easier, since given sufficient exposure, most children reach native-like levels of competence in second languages (p.47). This obviously completely ignores the demanding situations that face language minority children in the U.S. every day. A simplification into a one page hypothesis gives teachers the idea that these problems are easily solved and fluency is just a matter of following this path. As Gregg and McLaughlin point out, however, trying to put these ideas into practice, one quickly runs into problems. Curriculum Design The educational implications of Krashens theories become more apparent in the remainder of the book, where he and Terrell lay out the specific methods that make use of the Monitor Model. These ideas are based on Terrells earlier work (Terrell, 1977) but have been expanded into a full curriculum. The authors qualify this collection somewhat by saying that teachers can use all or part of the Natural Approach, depending on how it fits into their classroom. This freedom, combined with the thoroughness of their curriculum, make the Natural Approach very attractive. In fact, the guidelines they set out at the beginning communication is the primary goal, comprehension preceding production, production simply emerge, acquisition activities are central, and the affective filter should be lowered (p. 58-60) are without question, excellent guidelines for any language classroom. The compilation of topics and situations (p.67-70) which make up their curriculum are a good, broad overview of many of the things that students who study by grammar translation or audiolingual methods do not get. The list of suggested rules (p.74) is notable in its departure from previous methods with its insistence on target language input but its allowance for partial, non-grammatical or even L1 responses. Outside of these areas, application of the suggestions run into some difficulty. Three general communicative goals of being able to express personal identification, experiences and opinions (p.73) are presented, but there is no theoretical background. The Natural Approach contains ample guidance and resources for the beginner levels, with methods for introducing basic vocabulary and situations in a way that keeps students involved. It also has very viable techniques for more advanced and self-confident classes who will be stimulated by the imaginative situational practice (starting on p.101). However, teachers of the broad middle range of students who have gotten a grip on basic vocabulary but are still struggling with sentence and question production are left with conflicting advice. Once beyond one-word answers to questions, the Natural Approach ventures out onto thin ice by suggesting elicited productions. These take the form of open-ended sentences, open dialogs and even prefabricated patterns (p.84). These formats necessarily involve explicit use of grammar, which violates every hypothesis of the Monitor Model. The authors write this off as training for optimal Monitor use (p.71, 142), despite Krashens promotion of Monitor-free production. Even if a teacher were to set off in this direction and begin to introduce a structure of the day (p. 72), once again there is no theoretical basis for what to choose. Perhaps the most glaring omission is the lack of any reference to the Natural Order Hypothesis, which as noted previously, contained no realistically usable information for designing curriculum. Judging from the emphasis on exposure in the Natural Approach and the pattern of Krashens later publications, which focused on the Input Hypothesis, the solution to curriculum problems seems to be massive listening. However, as noted before, other than i + 1, there is no theoretical basis for overall curriculum design regarding comprehension. Once again, the teacher is forced to rely on a somewhat dubious order of acquisition, which is based on production anyway. Further, the link from exposure to production targets is tenuous at best. Consider the dialog presented on p.87: . . . to the question What is the man doing in this picture? the students may reply run. The instructor expands the answer. Yes, thats right, hes running.

The Input Hypothesis: Definition and Criticism

January 22, 2018, 9:00 am

Stephen Krashen is a linguist and educator who proposed the Monitor Model, a theory of second language acquisition, in Principles and practice in second language acquisition as published in 1982. According to the Monitor Model, five hypotheses account for the acquisition of a second language:

- Acquisition-learning hypothesis

- Natural order hypothesis

- Monitor hypothesis

- Input hypothesis

- Affective filter hypothesis

However, despite the popularity and influence of the Monitor Model, the five hypotheses are not without criticism. The following sections offer a description of the fourth hypothesis of the theory, the input hypothesis, as well as the major criticism by other linguistics and educators surrounding the hypothesis.

Definition of the Input Hypothesis

The fourth hypothesis, the input hypothesis, which applies only to language acquisition and not to language learning, posits the process that allows second language learners to move through the predictable sequence of the acquisition of grammatical structures predicted by the natural order hypothesis. According to the input hypothesis, second language learners require comprehensible input, represented by i+1 , to move from the current level of acquisition, represented by i , to the next level of acquisition. Comprehensible input is input that contains a structure that is “a little beyond” the current understanding—with understanding defined as understanding of meaning rather than understanding of form—of the language learner.

Second language acquisition, therefore, occurs through exposure to comprehensible input, a hypothesis which further negates the need for explicit instruction learning. The input hypothesis also presupposes an innate language acquisition device, the part of the brain responsible for language acquisition, that allows for the exposure to comprehensible input to result in language acquisition, the same language acquisition device posited by the acquisition-learning hypothesis. However, as Krashen cautions, like the time, focus, and knowledge required by the Monitor, comprehensible input is necessary but not sufficient for second language acquisition.

Criticism of the Input Hypothesis

Like for the acquisition-learning hypothesis, the first critique of the input hypothesis surrounds the lack of a clear definition of comprehensible input; Krashen never sufficiently explains the values of i or i+1 . As Gass et al. argue, the vagueness of the term means that i+1 could equal “one token, two tokens, 777 tokens”; in other words, sufficient comprehensible input could embody any quantity.

More importantly, the input hypothesis focuses solely on comprehensible input as necessary, although not sufficient, for second language acquisition to the neglect of any possible importance of output. The output hypothesis as proposed by Merrill Swain seeks to rectify the assumed inadequacies of the input hypothesis by positing that language acquisition and learning may also occur through the production of language. According to Swain who attempts to hypothesize a loop between input and output, output allows second language learners to identify gaps in their linguistic knowledge and subsequently attend to relevant input. Therefore, without minimizing the importance of input, the output hypothesis complements and addresses the insufficiencies of the input hypothesis by addressing the importance of the production of language for second language acquisition.

Thus, despite the influence of the Monitor Model in the field of second language learning and acquisition, the input hypothesis, the fourth hypothesis of the theory, has not been without criticism as evidenced by the critiques offered by other linguists and educators in the field.

Gass, Susan M. & Larry Selinker. 2008. Second language acquisition: An introductory course , 3rd edn. New York: Routledge. Krashen, Stephen D. 1982. Principles and practice in second language acquisition . Oxford: Pergamon. http://www.sdkrashen.com/Principles_and_Practice/Principles_and_Practice.pdf. Swain, Merrill. 1993. The output hypothesis: Just speaking and writing aren’t enough. The Canadian Modern Language Review 50(1). 158-164. Zafar, Manmay. 2009. Monitoring the ‘monitor’: A critique of Krashen’s five hypotheses. Dhaka University Journal of Linguistics 2(4). 139-146.

input hypothesis language acquisition language learning monitor model

The Monitor Hypothesis: Definition and Criticism

The Affective Filter Hypothesis: Definition and Criticism

Humanities Technology

Input hypothesis.

By Benjamin Niedzielski on January 14, 2020

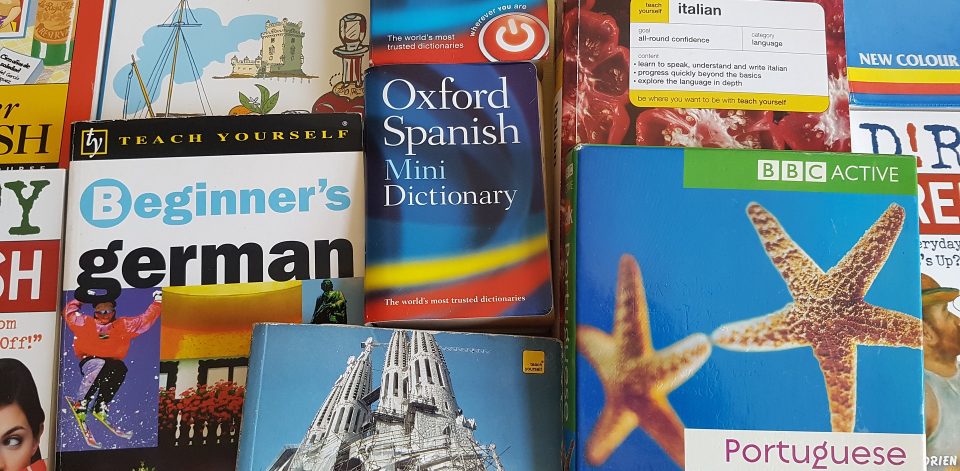

The idea that language learners need exposure to the language (or “input”) to make progress in the target language is neither surprising nor new. What is surprising is what the best type of input might be.

Linguist Stephen Krashen (a UCLA graduate) has written about this in his “Input Hypothesis”. Krashen supports an i+1 input approach for second language learners, meaning the best input is only one level above the learner’s level to maximize comprehension . This allows students to make use of context to understand unknown words or phrases, as native speakers do.

Krashen’s hypothesis is not accepted by everyone (see Zafar 2009 and Liu 2015 ), as it is difficult or impossible to test. In addition, it is unclear what exactly i+1 input looks like, as it varies from case to case. Still, the general idea is attractive even if the details are disputed.

Most modern language classes that I have taken across the United States have followed the Input Hypothesis (at least partially). Classes teach grammar and vocabulary step by step. Listening and reading activities contain mostly words that are already known. This lets students focus on new concepts without being overwhelmed, and build on what they have mastered.

However, no two students are at the same level in a language. Some will have more exposure outside of the classroom. Others may have competencies in a related language that puts them above their peers (knowing French helps learn Italian for instance). In larger classes, providing i+1 input to each student individually may be impossible to achieve.

Technology, however, can allow teachers and students to bridge this gap. For many languages, there are large amounts of “input” at different levels available online. An instructor can find (or create) sites at different levels and ask students to choose something to read or listen to for a certain amount of time, allowing students to find their own i+1 input from an approved list. Instructors can guide students by saying that what students choose must contain new words but be understandable without a dictionary.

Examples of these kind of resources are NHK News Web Easy or Wasabi’s Fairy Tales and Short Stories with Easy Japanese , with reading practice at different levels. One of my personal favorites was a German class where we used iPods to find and listen to German music or podcasts, such as like Deutsche Welle’s Langsam gesprochene Nachrichten (Slowly Spoken News), that we students liked and could easily understand.

Activities such as these allow students the flexibility to seek out their own i+1 input in an instructor curated fashion. They get more practice with a language outside of the classroom, and can find materials that meet their own needs and interests.

Whether or not the Input Hypothesis is correct, giving students these opportunities is a great way to engage them effectively with a language and culture.

Image: language-2345801_1920.jpg . Image is used under the Pixabay License .( https://pixabay.com/photos/language-learning-books-education-2345801/ )

- Deutsche Welle. “Langsam gesprochene Nachrichten“. https://www.dw.com/de/21102019-langsam-gesprochene-nachrichten/a-50911528

- Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Krashen, S. (1985). The Input Hypothesis: Issues and Implications. Harlow: Longman.

- NHK News Web Easy: https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/easy/

- Liu 2015: http://jehdnet.com/journals/jehd/Vol_4_No_4_December_2015/16.pdf

- Teaching English. “Comprehensible Input”. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/comprehensible-input . Accessed Nov. 5, 2019.

- Wasabi’s Fairy Tales and Short Stories with Easy Japanese: https://www.wasabi-jpn.com/japanese-lessons/fairy-tales-and-short-stories-with-easy-japanese/

- Zafar 2009: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/39ee/7d69dae91b26dcffd84d718eb93f6d7795a4.pdf

Blog Categories

- Best Practices

- How To’s

- Instruction

- Opportunities

Recent Posts

- Job Openings for Humanities Graduate Students

- The New Faces of Humtech!

- RITC Call 2023-2024

- Small Bytes Workshops return for Spring!

- Humanities Technology Brief 002

- Contact Info

- Careers and Opportunities

- Project Overview

- Current Projects

- Past Projects

- Project Support FAQ

- Scholarly Web Design Best Practices

- Computing Support

- Web Support

- Teaching Resources

- Submit a Ticket

- Education and Teaching Space (ENT)

- Experimental Learning Facility (ELF)

- Learning Lab @ Rolfe

- Mobile Laptop Cart

- Online Resource Classroom (ORC)

- Podcasting Cart

- Teaching Resource Center

- Upcoming Events

- DH Infrastructure Symposium

- Digital Humanities

Search Our Store:

The input hypothesis (krashen’s hypotheses series, #5 of 9).

(Previous post in this series: The Natural Order of Acquisition)

The next post in this series, The Affective Filter Hypothesis (#6/9) is found here .

Focus like a MAN I AC

I: the i nput hypothesis.

This is the big one

“Comprehensible input is the cause of language acquisition.”

The term ‘comprehensible input’ (C.I.) means messages in the target language that the learner can understand. C.I. is the “Goldilocks” level of input—not too hard, not too easy. It is input at the student’s current level of acquisition and just slightly above it, what Krashen calls the “ i + 1 ” level, where “ i ” is the level of acquisition of the student and “ +1 ” is a wee bit above it. Input that is too simple (already acquired) or too complex (out of reach at the moment) is not useful for second language acquisition.

Even input that is perceived by the student as very simple can have value, as the brain needs time to sort out the complex rules of grammar. Rules that are imperceptible to the conscious mind can be refined with seemingly simple input.

Comprehensible Input Can Be :

• Understanding messages in the language at your level, and just a bit above it. Krashen calls this i + 1 . The “ i ” in this formula is the student’s current level of acquisition, plus just a little bit more.

The i + 2/3/4… levels would be language that is not understandable to the student for some reason, be it unknown vocabulary, grammar the student has not heard before, unfamiliar topics, or subjects that are familiar but too deep for the current language level of the student.

• Independent reading in the TL at the 95% or better comprehension level.

• Listening to and understanding almost everything said in the TL. This understanding can be with the aid of gestures, body language, context and pictures.

• But, there is a problem… The idea of comprehensible input has become widespread in the last few years, which is a double-edged sword. It is being used so often in educational circles that the original meaning has become diluted by so many pouring their own meanings into it. Many seem to think it means teachers are using language that they (the teachers) understand, or that students get the general gist of. An alternate term that keeps the original meaning fresh is one coined by Terry Waltz: comprehended input . The input must be comprehended by the student. If what you say is not understood it is virtually worthless for acquisition.

APPLYING THE INPUT HYPOTHESIS IN THE CLASSROOM :

• Discard listen and repeat. Remember that for acquisition there is little-to-no place for the traditional “Listen and Repeat” strategy. Listening with understanding is often enough. Students sometimes do enjoy “practicing” sounds, but this does not help them to acquire the language or help them to hear it.

• Limit forced output. Since language is acquired by input, there is little role for forced output above the level of acquisition. Give students tools to respond in the form of rejoinders. Allow students to respond but, in general, do not force them to speak until they are ready.

• Allow and encourage output–but do not force it. There is a balance. Students feel like they are part of the club when they can speak. They want to express themselves. So provide them with tools and set up situations where they can express themselves simply and often, just do not force spontaneous discourse when they are neither ready nor able. Rejoinders are one way to encourage output, awareness of levels of questioning is another.

• Be sure it is “Comprehended Input” This is a genius term originated by Terry Waltz and it makes the meaning of what is valuable input clearer. The teacher speaking in the TL alone is not enough. Sometimes teachers think that if they are speaking the language slowly, clearly and accurately, it MUST be comprehensible input to the students. But students need to understand what is being said. Even if the teacher is speaking the target language perfectly, it does not count if students do not understand. Language only counts as helpful for acquisition when it is comprehended by the students.

Lack of understanding = It is not Comprehensible Input.

Only input that is comprehended by students counts for acquisition.

• Use clear language with interesting topics. Teacher and students have an equal part in the dance of acquisition: the teacher’s job is to speak clearly in the target language about interesting topics. The students’ job is to show you when you are not using language they can understand. If students do not demonstrate when they are understanding, you may not be doing your job and not even know it.

• Check often to be sure it is actually comprehensible. The language we speak in class must be comprehensible to all students, not just the top students that are responding all the time. The above average students may well be giving you a false reading on your degree of clarity.

Tell your students this often:

“My job is to give you clear, interesting language.

Your job is to let me know when I am not doing my job.”

They need to let me know when I am not being clear (speaking TL that they understand). If we are not checking in with students to be sure they understand, we may be busy, but not actually doing our jobs.

• Make sure all students understand. Discard the traditional practice of asking questions and plaintively waiting for the occasional hand to go up by the the boldest and brainiest. The Ferris Bueller model (‘Anyone? Anyone?’) was out of date and mocked in the movie 30 years ago. Don’t revive it.

Ask a variety of questions, and ask often.

Assign a student the task of counting how many questions you ask during the class period. Asking one question per minute of class is not too much.

• Use differentiated comprehension checks questions to be sure individual students understand at different levels. Know who your slower language processors are, who your medium language processors are, and who your faster processors are (this week). Ask them questions that are appropriate for their level. Throw each student the right pitch, the right level of question, for their level.

• Create a classroom culture where NOT understanding is OK. Avoid putting students in situations in class where they have only limited comprehension of the language—this can be extremely frustrating. Reward those that let you know when they do NOT understand. This is the opposite of a traditional classroom where students raise their hands to give an answer and show they know the answer.

Share This Article:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Original article

- Open access

- Published: 11 December 2019

Comparing the impacts of various inputs(I + 1 & I-1) on pre-intermediate EFL learners’ Reading comprehension and Reading motivation: the case of Ahvazi learners

- Ehsan Namaziandost 1 ,

- Mehdi Nasri 1 &

- Meisam Ziafar 2

Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education volume 4 , Article number: 13 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

8512 Accesses

7 Citations

Metrics details

Considering the vital role of comprehensible input, this study attempted to compare the effects of input with various difficulty levels on Iranian EFL learners’ reading comprehension and reading motivation. To fulfil this objective, 54 Iranian pre-intermediate EFL learners were selected from two intact classes ( n = 27 each). The selected participants were randomly assigned to two equal groups, namely “i + 1″ (n = 27) and “i-1″ group (n = 27). Then, the groups were pretested by a researcher-made reading comprehension test. After carrying out the pre-test, the treatment (i.e., extensive reading at different levels of difficulty) was practiced on the both groups. The participants in “i + 1″ group received reading passages beyond the current level, on the other hand, the “i-1″ group received those reading passages which were below their current level. After the instruction ended, a modified version of pre-test was conducted as posttest to determine the impacts of the treatment on the students’ reading comprehension. The obtained results indicated that there was a significant difference between the post-tests of “i + 1″ and “i-1″ groups. The findings showed that the “i + 1″ group significantly outperformed the “i-1″ group ( p < .05) on the post-test. Moreover, the findings indicated that “i + 1″ group’s motivation increased after the treatment. The implications of the study suggest that interactive type of input is beneficial to develop students’ language skills.

Introduction

There is a consensus of agreement among the researchers that input is vital for language learning to come about but they may not have analogous opinions about the way it is utilized bylearners (Gass and Selinker 2008 ). Input may be operationally described as “oral and/or written corpus of target language to which second language (L2) learners are subjected via different sources, and is perceived by them as language input” (Kumaravadivelu 2006 , p. 26). According to Ellis ( 2012 ), input-based instruction “includes the utilization of the input that learners are presented to or are needed to process” (p. 285). In this procedure, through presentation to language input, if students discover the way language works or the way language is rehearsed in workplace, or handicraft target condition, learning will be occurred (Basturkmen 2006 ; Tahmasbi et al. 2019 ). Thus, it can be deduced that input is of fundamental significance for language learning abilities particularly reading.

Reading is seen as “an essential expertise for EFL learners to enhance their language ability” (Chiang 2015 , p. 11). Reading is characterized as “a fluent process of readers joining information from a text and their own background knowledge to fabricate meaning” (Nunan 2003 , p. 68). It gives chances to foreign language learners to be presented to English in circumstances that language input is entirely restricted (Lao and Krashen 2000 ; Namaziandost et al. 2019c ; Wu 2012 ).

In recent years, extensive reading (ER) has gained particular consideration as an impressive and undertaking way of expanding foreign language skills (Yamashita 2013 ). ER aims “to progress good reading habits to form knowledge of vocabulary and grammar and to encourage a liking for reading” (Richards and Schmidt 2010 , p. 194). The major purpose in ER is to reach at a general understanding of what is read (Richards and Schmidt 2010 ). ER is for general comprehending in which “the minimum 95% comprehension figure” (Meng 2009 , p. 134) is admissible and the reading velocity is below 100 to 150 words per minute (Mikeladze 2014 ; Shakibaei et al. 2019 ). Truly, some studies (e.g., Bell 2001 ; Chiang 2015 ; Hitosugi and Day 2004 ; Iwahori 2008 ; Leung 2002 ; Tanaka 2007 ) have presented that ER significantly enhanced foreign language reading comprehension and general proficiency.

One of the best bountiful sources for providing language input for EFL learners is through extensive reading (ER) (Day and Bamford 1998 ; Krashen 1982 ). As indicated by Krashen ( 1982 ), the input to which learners are presented ought to be a little above their current level of competence, ‘i + 1,’ in which ‘i’ alludes to the present language capacity of learner, though ‘1’ alludes to the input that is somewhat above the learners’ present language ability. On the other hand, Day and Bamford ( 1998 ) suggested a diverse model on the hardness level of the input. Based on this hypothesis, “ER is efficacious if it furnishes students with input which is marginally beneath their current level of competence (i.e., ‘i-1’)” (Day and Bamford 1998 , p. 36). This way language learners can swiftly develop their reading certainty, reading fluency and construct sight words and high-frequency words.

However, a glance to the prior literature divulges that there are rare studies on the impacts of these two viewpoints (i.e., ‘i + 1’ and ‘i - 1’) on EFL learners’ reading comprehension and reading motivation. To cover the extant gap, the current study tried to focus on this theme by inspecting how Krashen’s input hypothesis through ‘i + 1′ and ‘i - 1’ materials may impress EFL students’ reading comprehension and reading motivation.

Literature review

Second language (L2) reading is a multifaceted, complex process in that it involves the interplay of a wide range of components. As a result, although most of the reviews on L2 reading research start with an attempt to answer the question ‘What is reading?’, nearly all of them go on to state that it is such a complex concept that no definition of reading, which is clearly stated, empirically supported, and theoretically unassailable, has been offered to date (e.g., Aebersold and Field 1997 ; Grabe and Stoller 2002 ; Namaziandost and Shafiee 2018 ; Urquhart and Weir 1998 ).

Grabe ( 2009 ) notes that a proper definition of reading will need to account for what fluent readers do when they read, what processes are used by them, and how these processes work together to build a general notion of reading. Granting that no single statement can capture the complexity of reading, Grabe ( 2009 ) states that reading can be conjured as a complex combination of processes – processes that are rapid, efficient, interactive, strategic, flexible, evaluative, purposeful, comprehending, learning, and linguistic (p. 14). In the most general terms, it can be stated that reading is a process that involves the reader, the text, and the interaction between the reader and the text (Grabe 2009 ; Grabe and Stoller 2002 ; Koda 2005 ; Mirshekaran et al. 2018 ). Reading researchers’ continuous attempts to explain how the reader and the text components interact, and how this interaction results in reading comprehension have paved the way to the conceptualization of a number of reading models, each focusing on different aspects of reading.

Generally, reading comprehension has been defined by researchers as “a critical part of the multifarious interplay of mechanisms involved in L2 reading” (Brantmeier 2005 , p. 52). For many students, reading is presumed as the beneficial dexterity that they can utilize inside and outside the classroom. It is additionally the skill that can preserve the lengthy time. According to Allen and Valette ( 1999 ), “reading is not only allotting foreign language sounds to the written words, but also the comprehension of what is written” (p. 249). Miller ( 2008 ) characterized “Reading comprehension as the ability to comprehend or to get meaning from any kind of written materials” (p. 8).

In Reading comprehension, readers get information from written texts and need to decode these data into meaningful messages so that they can understand the reading materials and achieve the purposes of reading. According to Wade and Trathen ( 1990 ) reading comprehension contains four key concepts: transmission translation, interaction, and transaction. It is a psycholinguistic process which starts with a linguistic surface representation encoded by a writer and ends with meaning which the reader constructs. There is thus an essential interaction between language and thought in reading. The writer encodes thought as language and the reader decodes language to thought (Carrell 2000 ; Ziafar and Namaziandost 2019 ). Existing research has shown that professional readers make choices as to what to read. When readers encounter comprehension problems, they use strategies to overcome their difficulties. Different learners seem to approach reading tasks in different ways and some of these ways appear to lead to better comprehension. It has been noted that the paths to success are numerous and that some routes seldom lead to success.

Regarding the mentioned points, reading widely is an individual movement which depends on the students’ fondness (Nation 1997 ). Extensive reading (ER) boosts reader’s reading aptitudes and it is shortsighted to urge EFL students to peruse better through ER which is enchanting to them (Nuttal 2000 ). The principle objective of an Extensive reading plan is to give a circumstance to students to appreciate reading a foreign language and new real messages quietly at their own velocity and with satisfactory comprehension (Day and Bamford 1998 ; Nasri and Biria 2017 ). “ER is bolstered by Krashen’s ( 1982 , 1994 ) input hypothesis, affective filter hypothesis, and delight hypothesis” (Bahmani and Farvardin 2017 , p. 6).

Reading extensively is an individual activity which is based on the learners’ interest (Nation 1997 ). ER enhances reader’s reading skills and it is easy to teach EFL learners to read better through ER which is enjoyable to them (Namaziandost et al. 2019a ; Nuttal 2000 ). The fundamental objective of an ER program is to provide a situation for learners to enjoy reading a foreign language and unfamiliar authentic texts silently at their own pace and with sufficient understanding (Day and Bamford 1998 ). ER is supported by Krashen’s ( 1982 , 1994 ) input hypothesis, affective filter hypothesis, and pleasure hypothesis.

According to Krashen’s ( 1982 ) input hypothesis, adequate exposure to comprehensible input is essential for language learners to learn the language. According to this hypothesis, the input to which learners are exposed should be a little beyond their current level of language competence, i.e., ‘i + 1.’ Based on this hypothesis, when learners frequently and repeatedly meet and concentrate on a large number of messages (input) which is a little beyond their level of competence, they gradually acquire the forms. Furthermore, based on Krashen’s affective filter hypothesis ( 1982 ), language acquisition occurs in low-anxiety situations. Foreign language learners with a low affective filter (e.g., anxiety) will attain the language acquisition or comprehension more easily (Hashemifardnia et al. 2018 ; Huang 2001 ). In the same vein, Krashen ( 1994 ) proposed the pleasure hypothesis, arguing that the pleasurable activities are effective and facilitating for language and literacy development. Based on this hypothesis, ER provides a low-anxiety situation for learners to learn a foreign language. Krashen’s hypotheses have encouraged different universities and institutions to do research in ER and utilize ER programs in foreign language teaching (Chiang 2015 ).

The Input Hypothesis directs the question of how we get language. This speculation expresses that we obtain (not learn) language by comprehending input that is a little past our current level of procured capability (Krashen and Terrell 1983 ; Nasri et al. 2019 ). This has been lately declared perspicuously by Krashen ( 2003 ): “we procure language in just one way: when we comprehend messages; that is, when we acquire “comprehensible input”” (p. 4). This potent allegation is rehashed in different spots where Krashen expresses that ‘comprehending inputs is the main way language is obtained’ and that ‘there is no individual variety in the key procedure of language procurement’ (Krashen 2003 , p. 4). Consequently, Krashen frequently utilizes the term ‘comprehension hypothesis’ ( 2003 ) to allude to the Input Hypothesis, contending that ‘perception’ is a superior depiction as only input is not sufficient; it must be comprehended.

Thus, based on Krashen’s ( 1982 ) input hypothesis, adequate presentation to understandable input is essential for language students to learn language. In light of this speculation, the input to which students are uncovered ought to be a little past their current level of language ability, i.e., ‘i + 1’. Considering Krashen’s perspective, when learners constantly and repeatedly confront and concentrate on an expansive quantity of input which is a little higher than their level of capability, they inchmeal obtain the structures. Krashen’s input hypotheses have motivated different universities and institutions to accomplish researches and studies in ER and utilize ER programs in teaching TEFL (Bahmani and Farvardin 2017 ; Chiang 2015 ).

Day and Bamford ( 1998 ), in particular, suggested a modern scheme which is diverse from Krashen’s ( 1982 ) input hypothesis. Based on this scheme, “ER is advantageous if it furnishes the students with input which is somewhat beneath their current level of competence (i.e., ‘i-1’)” (Bahmani and Farvardin 2017 , p. 4). Moreover, “‘i-1’ creates a condition for automaticity educating and extending a huge sight vocabulary rather than learning new target structures” (Mikeladze 2014 , p. 5). Truth to be told, ‘i-1’ is considered as the learners’ tranquility zone where they can rapidly construct their reading certainty and reading fluency (Abedi et al. 2019a ; Chiang 2015 ).

All of researchers and teachers accepted that motivation is a basic factor to enhance reading comprehension. As indicated by Dornyei ( 2001 ), the meaning of motivation is very intricate and obscurant because it is t is made out of various models and hypotheses. As discussed by Protacio ( 2012 ), “reading problems occur partly due to the fact that people are not motivated to read in the first place” (p. 11). Moley Bandré, and George ( 2011 ) explain that, motivation happens when “students develop an interest in and form a bond with a topic that lasts beyond the short term” (p. 251). Furthermore, Guthrie and Wigfield ( 2000 , p. 405) propound that “reading motivation is the individual’s personal objectives, values, and beliefs regarding the topics, processes, and outcomes of reading”. Considering this delineation, one would come to two principle consequences: The first is that reading motivation refers to putting together of various dimensions of motivation in an intricate route. The second is the type of agency people have over it since they can manipulate, unify and divert their motivation to read in terms of their credence, worthiness and objectives (Namaziandost et al. 2018b ; Wigfield and Tonks 2004 ). “Not only does reading motivation relate to reading comprehension, but it also relates to both the amount of reading and students’ reading achievement” (Guthrie and Wigfield 2005 , p. 76). Guthrie et al. ( 2006 , p. 232) elucidate that “reading motivation correlates with students’ amount of reading”. For this purpose, Guthrie and Wigfield ( 2005 ) emphasize the perspective that “reading motivation is domain-specific as it belongs to a status that necessitates an emotional reaction particular to a reading material, and that would metamorphose based on the diversity of activities inaugurating it” (p. 89).

Pachtman and Wilson ( 2006 ) expressed that it is crucial to propel students to read by giving them chances to choose their interest materials. In other words, readers need to read more when they are allowed to choose their reading materials since they should find out that reading is a pleasurable action. As indicated by Hairul, Ahmadi, and Pourhosein ( 2012 ), reading motivation is the substantial measure of motivation that learners need to focus their positive or negative feelings about reading. For example, students who read for joy and utilizing ways to help their understanding are amazingly roused readers. Students of this sort regularly view reading as a vital factor in their daily exercises, acknowledge difficulties in the reading procedure and are probably going to be effective readers.

Hairul, Ahmadi, and Pourhosein ( 2012 ) believed that reading motivation greatly affects reading appreciation. The researchers proceeded with that reading motivation impacts all parts of motivation and reading appreciation procedures in various conditions. They additionally accentuated that learners’ inspiration totally influences their understanding; it implies that learners with more stronger reading inspiration can be relied upon to read more in more extensive territory. As indicated by Hairul, Ahmadi, and Pourhosein ( 2012 ), a standout amongst the most essential components which help students read more is reading inspiration and it importantly affects reading perception. In this manner, numerous researchers have been very much aware of the noteworthiness of inspiration in the objective language learning and how inspiration expands appreciation among language students.

Prior researches have checked the impacts of ER on EFL reading comprehension and vocabulary learning. Bell ( 2001 ) carried out a two-semester study on young adult students at the elementary level in Yemen to compare the impacts of ER and intensive reading on reading speed and reading comprehension. This study was run over two semesters. The researcher divided students into two groups: an experimental group ( n = 14) and a control group ( n = 12). The experimental group received an ER program and read graded readers; these students had access to 2000 graded readers in the British Council library. On the other hand, the control group received the intensive reading program, read short passages and filled the tasks. The researcher measured students’ reading speed by utilizing two reading tests, and for measuring their reading comprehension he utilized three various texts with three types of questions (cloze, multiple-choice, and true-false). The two groups enhanced both in speed and reading comprehension, but the ER program based on graded readers was much more effective to the enhancement of reading speed than the intensive reading program. The outcomes of the reading comprehension test also indicated that the learners in the extensive group got higher scores than students in the intensive group.

Chiang ( 2015 ) researched the impacts of different text difficulty on L2 reading perceptions and reading comprehension. To give the ideal test to L2 reading, comprehensible input hypothesis hypothesizes that selecting text somewhat more difficult than the student’s present level will improve reading perception. Fifty-four freshman from one college in central Taiwan were arbitrarily separated into two groups. Level 3 and level 4 Oxford Graded Readers were given to the learners in the ‘i − 1’ group while students in the ‘i + 1’ group were equipped with level 5 and level 6. Quantitative data were collected through the English Placement Test and the Reading Attitudes Survey. Findings from the pretest and posttest of the Reading Attitudes Survey propose that the i-1 group has achieved significantly in reading attitudes, while no difference in reading attitude was recognized with the i + 1 group. The outcomes additionally indicated that diverse hardness levels of reading text did not significantly influence participants’ reading comprehension.

Bayat and Pomplun ( 2016 ) aimed to indicate how several eye-tracking features within reading are influenced by different primary agents, as individual discrepancies, the hardness level of the text, and the topic of the text. To this end, they directed an eye-following experiment with 21 participants who read six sections with various points. For each topic, metamorphosis in three factors were assessed: the mediocre obsession term, the student estimate, and the normal rapidity of reading. The Flesch reading ease score was utilized as a measurement for the hardness level of the content. Examination of difference is utilized as a part of request to break down determinant factors related with content attributes, containing the difficulty level and the point of the content. The findings showed that during the reading of entries with comparable difficulty levels, the point of the content has no noteworthy impact on mediocre obsession span and mediocre understudy estimate, though a critical effect overall speed of reading is watched. Additionally, individual properties have a primary effect on eye-movement demeanor.

Ahmadi ( 2017 ) attempted to consider the effect of reading motivation on reading comprehension. In his paper, he explained the terms reading motivation, different types of motivation, reading comprehension, and different models of reading comprehension. The review of this study showed that reading motivation had a considerably positive effect on reading comprehension activities.

Recently, Bahmani and Farvardin ( 2017 ) examined the impacts of various text difficultylevels on foreign language reading anxiety (FLRA) and reading comprehension of English as aForeign Language (EFL) learners. To fulfil this objective, 50 elementary EFL learners were chosen from two intact classes ( n = 25 each). One class was considered as ‘ i + 1’ and another as ‘ i -1’. The participants in each class practiced extensive reading at diverse levels of difficulty for two semesters. A reading comprehension test and the FLRA Scale were administered before and after the treatment. The outcomes indicated that both text difficulty levels significantly enhanced the participants’ reading comprehension. Moreover, the results revealed that, the ‘ i + 1′ group’s FLRA augmented, while that of the ‘ i - 1’ group diminished.

However, to the best of the researchers’ knowledge, rare studies, if any, have been carried out on the impacts of Krashen’s Input Hypothesis (i.e., ‘ i + 1’ and ‘ i - 1’) on EFL learners’ reading comprehension and reading motivation. To reach the purposes of the study, this study attempted to response the following research questions:

RQ1: Are there any significant differences between and within the ‘ i + 1’ and the ‘ i - 1’ groups’ reading comprehension after implementing the treatment? If so, which group has higher reading comprehension in English?

RQ2: Are there any significant differences between and within the ‘ i + 1’ and the ‘ i - 1’ groups’ reading motivation after implementing the treatment? If so, which group has higher motivation towards reading in English?

Methodology

A quasi-experimental approach was utilized in this study gather data from 54 EFL learners to check the potentially various impacts of using ‘i + 1’ versus ‘i - 1’ readers on reading motivation and reading comprehension. To this end, the reading motivation and reading comprehension of the participants were quantitatively measured prior to and after the intervention of ER through the Foreign Language Reading Motivation and the FCE (First Certificate in English).

Participants

Fifty-four EFL learners (25 males and 29 females) were selected from two intact classes in a private language institute in Iran. The participants’ ages ranged from 16 to 21. American Headway 1 (Soars and Soars 2010 ) was the textbook taught to the participants. According to the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) classification, American Headway 2 is appropriate for the B1 level. To ensure the participants’ proficiency level, CEFR Headway placement test ( 2012 ) was performed to all participants, and their score ranged between 66 and 74, which is equal to B1 level. The participants were chosen from two intact classes. Each class was assigned to a group (i.e., ‘i + 1’ or ‘i - 1’). The ‘i + 1′ group ( n = 27) read graded readers stories which were beyond their level of proficiency, whereas the ‘i - 1’ group (n = 27) read graded readers stories which were below their level of proficiency. The participants read graded readers along with their classroom materials. Per week, 35 min of class time was devoted to the participants’ narration of the novels they had already read.

Instruments

Cefr headway placement test.

CEFR Headway placement test is designed to provide a useful tool to estimate the participants’ level at which they should begin or continue their English language studies (Bahmani and Farvardin 2017 ). This test was selected because the participants were studying American Headway. Moreover, the American Headway book, CEFR Headway placement test ( 2012 ) and Oxford Bookworm Series (the graded readers in this study) were classified based on CEFR. It could be a big help to determine the probable ‘i’ of participants (Bahmani and Farvardin 2017 ). CEFR Headway placement test ( 2012 ) comprised of 100 multiple-choice items with three sections, including 50 vocabulary, 25 grammar and 25 reading comprehension items. The findings were compared with the band score of CEFR Headway placement test (see Table 1 ).

Graded readers

The reading materials in this study were the Oxford Bookworms Series published by Oxford University Press. The Oxford Bookworms Series classifies books into seven levels. Table 2 indicates the word counts and CEFR levels in the Oxford Bookworms series.

To make sure what level is appropriate, nine EFL learners at the pre-intermediate level and four EFL teachers were asked to read the Oxford Bookworms Series at various levels. After studying the books, all teachers agreed that for the pre-intermediate level learners, Starter, Level, and Level 2 were really easy, and Levels 4, 5 and 6 were both grammatically and lexically difficult. According to the teachers, Level 3 was considered suitable for the pre-intermediate level. The learners also reported that Level 3 was comprehensible for them. Level 3 equals to levels B1 in CEFR. Therefore, Level 3 was determined as the appropriate level for the participants. Accordingly, the ‘i - 1’ group was proposed to read Levels 1 and 2 and the ‘i + 1’ group was suggested to read Levels 4 and 5. The participants were required to read two books at each level throughout the study.

Reading comprehension test

The reading comprehension part of the Cambridge First Certificate in English (FCE 2008 ) was used to measure the participants’ reading comprehension ability. It included four parts: Part one was actually included 8 items. Part One consisted of a modified cloze test containing eight gaps. There were 4-option multiple-choice items for each gap. The main focus in this part one was on vocabulary, e.g. idioms, collocations, fixed phrases, complementation, phrasal verbs, and semantic precision.

Part Two comprised of 7 questions. It consisted of one text from which seven sentences have been removed and placed in jumbled order after the text, together with a seventh sentence which does not fit in any of the gaps. Candidates must decide from which part of the text the sentences have been removed. In part two, the main focus was on cohesion, coherence, and text structure.

The Third Part included 8 questions and consisted of a text containing eight gaps (plus one gap as an example). Each gap corresponded to a word. The stem of the missing word was given beside the text and must be changed to form the missing word. Candidates needed to form an appropriate word from given stem words to fill each gap. This part concentrated on vocabulary, in particular the use of affixation, internal changes, and compounding in word formation.

In the last part, i.e., Part Four, which included 7 items, one long text preceded by seven multiple-matching questions. Candidates were required to locate the specific information which matches the questions. Some of the options might be correct for more than one question. The primary focus in this part was one detail, opinion, specific information, and implication.

In general, the reading section of the FCE used in this study included 30 items which should be answered in 30 min. Two forms of this test were available, as equivalent forms. Hence, one form was used as the pretest, the other as posttest. It should be mentioned that the test was a mixture of both about and beneath the students’ current level. A Parson correlation coefficient between the two equivalent forms of the FCE was calculated as 0.899 which indicated a high reliability between the two versions of the test.

The motivation for reading questionnaire (MRQ)

Another instrument utilized in the present study was a modified sample of Motivation forReading Questionnaire (MRQ). MRQ was expanded by Dr. Allan Wigfield and Dr. John Guthrie from University of Maryland in 1997 (Wigfield and Guthrie 1997 ). Wigfield and Guthrie utilized the MRQ on a group of students at one mid-Atlantic state school during implementation of Concept-Oriented Reading teaching. Factor analyses carried out by Wigfield and Guthrie affirmed the essence of construct validity which backups eleven factors for the total 53 -item in this MRQ. There was an affirmative relevance of maximum segments of reading motivation with low - to high levels. They additionally asserted that their questionnaire has a reliability range from .43 to .81. In this research, the researchers had selected 30 items of the entire 53 items in the questionnaire because solely eight aspects of total eleven aspects of reading motivation were identified to measure. They are: reading efficacy, reading challenge, reading curiosity, reading involvement, importance of reading, reading word avoidance, social reasons for reading, and reading for grades. MRQ was a five-point Likert scale questionnaire made up of five options: 1 for ‘I strongly agree’, 2 for ‘I agree’, 3 for ‘I don’t know’, 4 for ‘I disagree’, and 5 for ‘I strongly disagree’. The MRQ was given to participants twice, one before the treatment and once after the treatment.

Data collection procedure

Fifty-four pre-intermediate EFL learners were participated in this study. In the first week, the CEFR Headway placement test was performed to specify the participants’ proficiency levels. This test additionally helped the researchers detemine the probable participants’ ‘i.’ In the second week, the MRQ and the reading comprehension test were carried out in 80 min. Based on the outcomes of the CEFR Headway placement test ( 2012 ), the ‘i + 1’ group were assigned to read graded readers at Levels 4 and 5, and the ‘i - 1’ group were assigned to read Level 1 and Level 2 graded stories. There was a small library and bookstore in the language institute to provide the participants with the graded readers. It was also proposed that if they would not find the book of their interest, they could find them from other libraries and bookstores outside.

The number of pages the participants required to read was specified at the outset of each week. At the end of each week, 20 min of the class was allocated for their reports. The participants were given time to talk about various parts and the characters of the novels, their ideas about the end of the novels, and even provided some comments regarding the novels. In the first semester, the ‘i + 1’ group read two graded readers at Level 4 which were one level beyond their ‘i’, and in the second semester, they read two graded readers at Level 5. On the other hand, in the first semester, the ‘i - 1’ group read two graded readers at the Level 1 which was two levels below their ‘i’ and in the second semester, they read two graded readers at Level 2 which was one level below their ‘i.’ Finally, after a three-month involvement in this study, the findings of these two various ways were compared with each other. In the last week of, the participants received an immediate posttest. They responded the MRQ and an equivalent version of the reading comprehension test in one session. The procedure was like the pretest.

Data analysis

Collected data through the aforesaid procedures were analyzed by using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) software version 25. Firstly, Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test was run to check the normality of the data. Then, two independent samples t-tests were done to figure out if there was any significant difference between the ‘i + 1’ and the ‘i - 1’ groups in terms of reading comprehension and MRQ. At the end, two 2 × 2 mixed analysis of variance (ANOVAs) were run to discover significant interaction impacts between time and group from the reading comprehension test and the MRQ. Furthermore, independent samples t-tests were run to test the simple main impacts of group on the pretests and the posttests. Paired samples t-tests were also done to further follow up on the simple main impacts of time on MRQ and reading comprehension for both groups. To indicate the practical significance, for all of the t-tests, effect sizes (Cohen’s ds) were computed.

Results and discussion

The previous section included a delineation of the methodology which was utilized to respond the research questions of this study, which are rewritten here for reasons of convenience: (a) Are there any significant differences between and within the ‘ i + 1’ and the ‘ i - 1’ groups’ reading comprehension after implementing the treatment? If so, which group has higher reading comprehension in English? and (b) Are there any significant differences between and within the ‘ i + 1′ and the ‘ i - 1′ groups’ reading motivation after implementing the treatment? If so, which group has higher motivation towards reading in English?

Results of normality tests

Before conducting any analyses on the pretest and posttest, it was indispensable to peruse the normality of the distributions. Thus, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality was run on the data acquired from the above-mentioned tests. The consequences are presented in Table 1 :

The p values under the Sig. column in Table 3 determine whether the distributions were normal or not. A p value greater than .05 shows a normal distribution, while a p value lower than .05 demonstrates that the distribution has not been normal. Since all the p values in Table 1 were larger than .05, it could be concluded that the distributions of scores for the pretest, posttest, and MRQ obtained from both groups had been normal. It is thus safe to proceed with parametric test (i.e. Independent and Paired samples t-tests and mixed-ANOVA in this case) and make further comparisons between the participating groups. Table 4 displays the means and standard deviations of the participants’ scores on the reading comprehension tests and the MR questionnaire before and after the study.