- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Humanistic Psychology?

A Psychology Perspective Influenced By Humanism

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

James Lacy, MLS, is a fact-checker and researcher.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/James-Lacy-1000-73de2239670146618c03f8b77f02f84e.jpg)

Other Types of Humanism

- How to Use It

Potential Pitfalls

Humanistic psychology is a perspective that emphasizes looking at the whole individual and stresses concepts such as free will, self-efficacy, and self-actualization. Rather than concentrating on dysfunction, humanistic psychology strives to help people fulfill their potential and maximize their well-being.

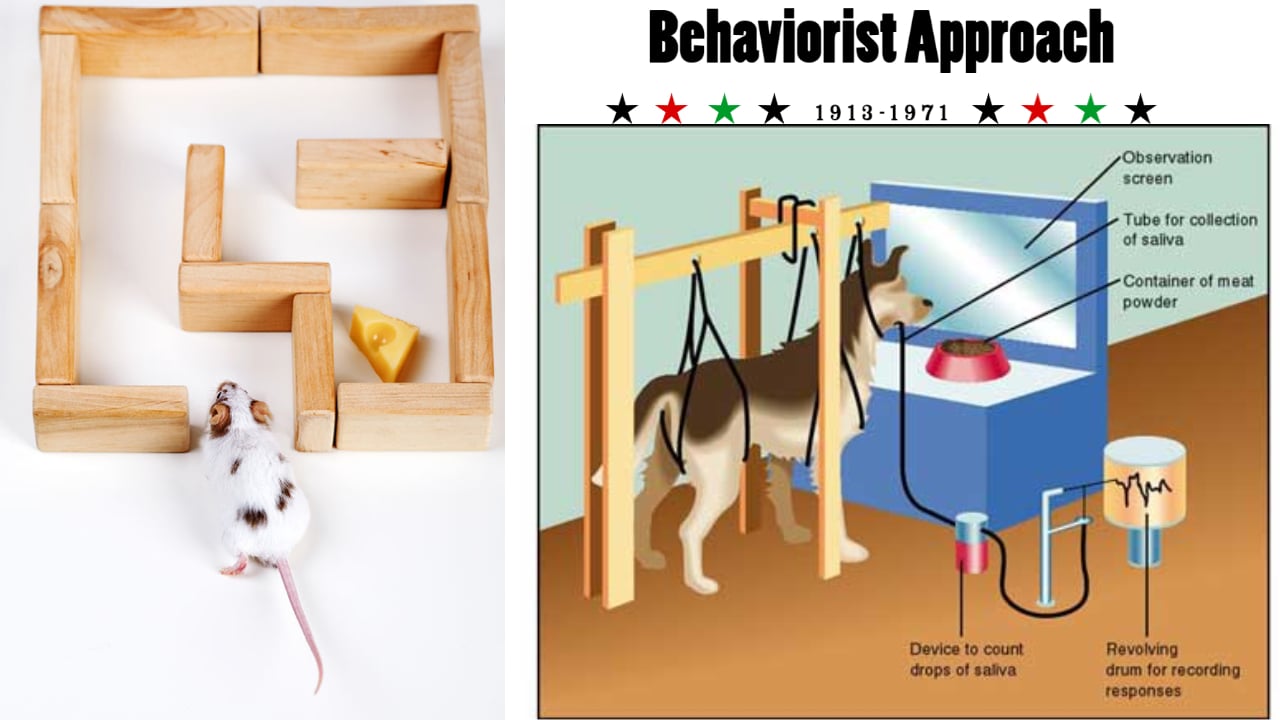

This area of psychology emerged during the 1950s as a reaction to psychoanalysis and behaviorism, which had dominated psychology during the first half of the century. Psychoanalysis was focused on understanding the unconscious motivations that drive behavior while behaviorism studied the conditioning processes that produce behavior.

Humanist thinkers felt that both psychoanalysis and behaviorism were too pessimistic, either focusing on the most tragic of emotions or failing to take into account the role of personal choice.

However, it is not necessary to think of these three schools of thought as competing elements. Each branch of psychology has contributed to our understanding of the human mind and behavior.

Humanistic psychology added yet another dimension that takes a more holistic view of the individual.

Humanism is a philosophy that stresses the importance of human factors rather than looking at religious, divine, or spiritual matters. Humanism is rooted in the idea that people have an ethical responsibility to lead lives that are personally fulfilling while at the same time contributing to the greater good of all people.

Humanism stresses the importance of human values and dignity. It proposes that people can resolve problems through science and reason. Rather than looking to religious traditions, humanism focuses on helping people live well, achieve personal growth, and make the world a better place.

The term "humanism" is often used more broadly, but it also has significance in a number of different fields, including psychology.

Religious Humanism

Some religious traditions incorporate elements of humanism as part of their belief systems. Examples of religious humanism include Quakers, Lutherans, and Unitarian Universalists.

Secular Humanism

Secular humanism rejects all religious beliefs, including the existence of the supernatural. This approach stresses the importance of logic, the scientific method, and rationality when it comes to understanding the world and solving human problems.

Uses for Humanistic Psychology

Humanistic psychology focuses on each individual's potential and stresses the importance of growth and self-actualization . The fundamental belief of humanistic psychology is that people are innately good and that mental and social problems result from deviations from this natural tendency.

Humanistic psychology also suggests that people possess personal agency and that they are motivated to use this free will to pursue things that will help them achieve their full potential as human beings.

The need for fulfillment and personal growth is a key motivator of all behavior. People are continually looking for new ways to grow, to become better, to learn new things, and to experience psychological growth and self-actualization.

Some of the ways that humanistic psychology is applied within the field of psychology include:

- Humanistic therapy : Several different types of psychotherapy have emerged that are rooted in the principles of humanism. These include client-centered therapy, existential therapy, and Gestalt therapy .

- Personal development : Because humanism stresses the importance of self-actualization and reaching one's full potential, it can be used as a tool of self-discovery and personal development.

- Social change : Another important aspect of humanism is improving communities and societies. For individuals to be healthy and whole, it is important to develop societies that foster personal well-being and provide social support.

Impact of Humanistic Psychology

The humanist movement had an enormous influence on the course of psychology and contributed new ways of thinking about mental health. It offered a new approach to understanding human behaviors and motivations and led to the development of new techniques and approaches to psychotherapy .

Some of the major ideas and concepts that emerged as a result of the humanistic psychology movement include an emphasis on things such as:

- Client-centered therapy

- Fully functioning person

- Hierarchy of needs

- Peak experiences

- Self-actualization

- Self-concept

- Unconditional positive regard

How to Apply Humanistic Psychology

Some tips from humanistic psychology that can help people pursue their own fulfillment and actualization include:

- Discover your own strengths

- Develop a vision for what you want to achieve

- Consider your own beliefs and values

- Pursue experiences that bring you joy and develop your skills

- Learn to accept yourself and others

- Focus on enjoying experiences rather than just achieving goals

- Keep learning new things

- Pursue things that you are passionate about

- Maintain an optimistic outlook

One of the major strengths of humanistic psychology is that it emphasizes the role of the individual. This school of psychology gives people more credit for controlling and determining their state of mental health.

It also takes environmental influences into account. Rather than focusing solely on our internal thoughts and desires, humanistic psychology also credits the environment's influence on our experiences.

Humanistic psychology helped remove some of the stigma attached to therapy and made it more acceptable for normal, healthy individuals to explore their abilities and potential through therapy.

While humanistic psychology continues to influence therapy, education, healthcare, and other areas, it has not been without some criticism.

For example, the humanist approach is often seen as too subjective. The importance of individual experience makes it difficult to objectively study and measure humanistic phenomena. How can we objectively tell if someone is self-actualized? The answer, of course, is that we cannot. We can only rely upon the individual's assessment of their experience.

Another major criticism is that observations are unverifiable; there is no accurate way to measure or quantify these qualities. This can make it more difficult to conduct research and design assessments to measure hard-to-measure concepts.

History of Humanistic Psychology

The early development of humanistic psychology was heavily influenced by the works of a few key theorists, especially Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers. Other prominent humanist thinkers included Rollo May and Erich Fromm.

In 1943, Abraham Maslow described his hierarchy of needs in "A Theory of Human Motivation" published in Psychological Review. Later during the late 1950s, Abraham Maslow and other psychologists held meetings to discuss developing a professional organization devoted to a more humanist approach to psychology.

They agreed that topics such as self-actualization, creativity, individuality, and related topics were the central themes of this new approach. In 1951, Carl Rogers published "Client-Centered Therapy," which described his humanistic, client-directed approach to therapy. In 1961, the Journal of Humanistic Psychology was established.

It was also in 1961 that the American Association for Humanistic Psychology was formed and by 1971, humanistic psychology become an APA division. In 1962, Maslow published "Toward a Psychology of Being," in which he described humanistic psychology as the "third force" in psychology. The first and second forces were behaviorism and psychoanalysis respectively.

A Word From Verywell

Today, the concepts central to humanistic psychology can be seen in many disciplines including other branches of psychology, education, therapy, political movements, and other areas. For example, transpersonal psychology and positive psychology both draw heavily on humanist influences.

The goals of humanism remain as relevant today as they were in the 1940s and 1950s and humanistic psychology continues to empower individuals, enhance well-being, push people toward fulfilling their potential, and improve communities all over the world.

Maslow AH. A theory of human motivation . Psychological Review. 1943;50(4):370-396. doi:10.1037/h0054346

Greening T. Five basic postulates of humanistic psychology . Journal of Humanistic Psychology . 2006;46(3): 239-239. doi:10.1177/002216780604600301

Schneider KJ, Pierson JF, Bugental JFT. The Handbook of Humanistic Psychology: Theory, Research, and Practice. Thousand Oaks: CA: SAGE Publications; 2015.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

A Humanistic Approach to Mental Health Assessment, Evaluation, and Measurement-Based Care

- First Online: 13 July 2022

Cite this chapter

- William E. Hanson 7 ,

- Hansen Zhou 8 ,

- Diana L. Armstrong 9 &

- Noëlle T. Liwski 10

Part of the book series: The Springer Series on Human Exceptionality ((SSHE))

1008 Accesses

Mental health assessment and evaluation models have waxed and waned over the years. However, a contemporary humanistic approach, Collaborative/Therapeutic Assessment (C/TA), holds considerable promise and staying power. When combined with Measurement-Based Care (MBC), therapeutic processes and outcomes are enhanced. This chapter focuses on the integration of C/TA and MBC into clinical practice. It includes relevant theory and research, real-life applications and examples, and answers fundamental questions, like “Can mental health assessment and testing actually be collaborative and humanistic in nature?” and “As clinicians, why should we care about measuring clients’ treatment progress?” At the end of the chapter, illustrative graphs and verbatim scripts are provided for clinical use.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Psychometrically sound measures also exist regarding clinicians’ attitudes toward MBC, including the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale-Routine Outcome Monitoring (Rye et al., 2019 ) and the Monitoring Feedback Attitude Scale (Jensen-Doss et al., 2018 ).

“Alex” is a pseudonym. Although she is an actual former client—and all process-outcome data are real—potentially identifying information was changed significantly to preserve anonymity and client confidentiality. Alex gave permission to be included in this case study for illustrative purposes.

The authors thank Aida Javaheri, a doctoral student in Concordia University of Edmonton’s PsyD program, for helping reconcile references and in-text citations

Ackerman, S. J., Hilsenroth, M. J., Baity, M. R., & Blagys, M. D. (2000). Interaction of therapeutic process and alliance during psychological assessment. PsycEXTRA Dataset . https://doi.org/10.1037/e323122004-009

Amble, I., Gude, T., Stubdal, S., Andersen, B. J., & Wampold, B. E. (2015). The effect of implementing the Outcome Questionnaire-45.2 feedback system in Norway: A multisite randomized clinical trial in a naturalistic setting. Psychotherapy Research, 25 (6), 669–677. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2014.928756

Article PubMed Google Scholar

American Psychological Association (2017). Therapeutic assessment with adults [DVD] . Available from http://www.apa.org/pubs/videos/4310960.aspx

Anastasi, A. (1992). What counselors should know about the use and interpretation of psychological tests. Journal of Counseling & Development, 70 , 610–615.

Article Google Scholar

Andersson, E. (2018, April). Rethinking therapy: How 45 questions can revolutionize mental health care in Canada. Globe and mail. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-rethinking-therapy-how-45-questions-can-revolutionize-mental-health/

Anker, M. G., Duncan, B. L., & Sparks, J. A. (2009). Using client feedback to improve couple therapy outcomes: A randomized clinical trial in a naturalistic setting. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77 (4), 693–704. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016062

APA Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice. (2006). Evidence-based practice in psychology. American Psychologist, 61 (4), 271–285.

Aschieri, F., Fantini, F., & Finn, S. E. (2018). Incorporation of therapeutic assessment into treatment with clients in mental health programming. APA Handbook of Psychopathology: Psychopathology: Understanding, Assessing, and Treating Adult Mental Disorders, 1 , 631–642. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000064-025

Aschieri, F., Fantini, F., & Smith, J. D. (2016). Collaborative/therapeutic assessment: Procedures to enhance client outcomes. In S. F. Maltzman (Ed.), Oxford handbook of treatment processes and outcomes in counseling psychology (pp. 241–269). Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Aschieri, F., & Smith, J. D. (2012). The effectiveness of therapeutic assessment with an adult client: A single-case study using a time-series design. Journal of Personality Assessment, 94 (1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2011.627964

Bargmann, S. & Robinson, B. (2012). Manual 2: Feedback-informed clinical work: The basics. International Center for Clinical Excellence.

Beatch, R., Bedi, R. P., Cave, D., Domene, J. F., Harris, G. E., Haverkamp, B. E., & Mikhail, A. M. (2009). Counselling psychology in a Canadian context: Report from the executive committee for a Canadian understanding of counselling psychology. Report commissioned by the Counselling Psychology Section 24 of the Canadian Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://cpa.ca/docs/File/Sections/Counselling/CPA-CNPSY-Report-Final%20nov%2009.pdf

Bedi, R. P., Haverkamp, B. E., Beatch, R., Cave, D., Domene, J. F., Harris, G. E., & Mikhail, A.-M. (2011). Counselling psychology in a Canadian context: Definition and description. Canadian Psychology, 52 (2), 128–138. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023186

Bedi, R. P., Klubben, L. M., & Barker, G. T. (2012). Counselling vs. CLINICAL: A comparison of psychology doctoral programs in Canada. Canadian Psychology, 53 (3), 238–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028558

Bickman, L., Riemer, M., Breda, C., & Kelley, S. D. (2006). CFIT: A system to provide a continuous quality improvement infrastructure through organizational responsiveness, measurement, training, and feedback. Report on Emotional & Behavioral Disorders in Youth, 6, 86–87, 93–94. Retrieved from http://www.civicresearchinstitute.com/online/article_abstract.php?pid=5&iid=113&aid=721

Bordin, E. S., & Bixler, R. H. (1946). Test selection: A process of counseling. Readings in Modern Methods of Counseling. , 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/10841-016

Brattland, H., Koksvik, J. M., Burkeland, O., Klöckner, C. A., Lara-Cabrera, M. L., Miller, S. D., Wampold, B., Ryum, T., & Iversen, V. C. (2019). Does the working alliance mediate the effect of routine outcome monitoring (rom) and alliance feedback on psychotherapy outcomes? A secondary analysis from a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66 (2), 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000320

Brown, J. D., & Morey, L. C. (2016). Therapeutic assessment in psychological triage using the PAI. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98 (4), 374–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2015.1123160

Canadian Psychological Association (2012). Evidence-based practice of psychological treatments: A Canadian perspective – Report of the CPA Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice of Psychological Treatments . Retrieved from https://cpa.ca/docs/File/Practice/Report_of_the_EBP_Task_Force_FINAL_Board_Approved_2012.pdf

Claiborn, C. D., & Hanson, W. E. (1999). Test interpretation: A social influence perspective. In J. W. Lichtenbeg & R. K. Goodyear (Eds.), Scientist-practitioner perspectives on test interpretation (pp. 1–14). Allyn & Bacon.

Curry, K. T., & Hanson, W. E. (2010). National survey of psychologists’ test feedback training, supervision, and practice: A mixed methods study. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92 ( 4 ), 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2010.482006

Dana, R. H. (1985). A service-delivery paradigm for personality assessment. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49 (6), 598–604. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4906_6

de Jong, K., Segaar, J., Ingenhoven, T., van Busschbach, J., & Timman, R. (2018). Adverse effects of outcome monitoring feedback in patients with personality disorders: A randomized controlled trial in day treatment and inpatient settings. Journal of Personality Disorders, 32 (3), 393–413. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2017_31_297

de Jong, K., van Sluis, P., Nugter, M. A., Heiser, W. J., & Spinhoven, P. (2012). Understanding the differential impact of outcome monitoring: Therapist variables that moderate feedback effects in a randomized clinical trial. Psychotherapy Research, 22 (4), 464–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2012.673023

De Saeger, H., Kamphuis, J. H., Finn, S. E., Smith, J. D., Verheul, R., van Busschbach, J. J., Feenstra, D. J., & Horn, E. K. (2014). Therapeutic assessment promotes treatment readiness but does not affect symptom change in patients with personality disorders: Findings from a randomized clinical trial. Psychological Assessment, 26 (2), 474–483. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035667

Dressel, P. L., & Matteson, R. W. (1950). The effect of CLIENT participation in test interpretation. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 10 (4), 693–706. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316445001000407

Duckworth, J. (1990). The counseling approach to the use of testing. The Counseling Psychologist, 18 (2), 198–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000090182002

Durosini, I., Tarocchi, A., & Aschieri, F. (2017). Therapeutic assessment with a client with persistent complex bereavement disorder: A single-case time-series design. Clinical Case Studies, 16 (4), 295–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650117693942

Ellis, T. E., Green, K. L., Allen, J. G., Jobes, D. A., & Nadorff, M. R. (2012). Collaborative assessment and management of suicidality in an inpatient setting: Results of a pilot study. Psychotherapy, 49 (1), 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026746

Ellis, T. E., Rufino, K. A., & Allen, J. G. (2017). A controlled comparison trial of the collaborative assessment and management of suicidality (CAMS) in an inpatient setting: Outcomes at discharge and six-month follow-up. Psychiatry Research, 249 , 252–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.032

Errazuriz, P., & Zilcha-Mano, S. (2018). In psychotherapy with severe patients discouraging news may be worse than no news: The impact of providing feedback to therapists on psychotherapy outcome, session attendance, and the alliance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86 (2), 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000277

Finn, S. E. (1996). Manual for using the MMPI-2 as a therapeutic intervention . University of Minnesota Press.

Finn, S. E. (2003). Therapeutic assessment of a man with “ADD”. Journal of Personality Assessment, 80 (2), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8002_01

Finn, S. E. (2009). Therapeutic assessment . Retrieved from http://www.therapeuticassessment.com

Finn, S. E. (2007). In our clients’ shoes: Theory and techniques of therapeutic assessment . Psychology Press.

Finn, S. E., Fischer, C. T., & Handler, L. (2012). Collaborative/therapeutic assessment: A casebook and guide . Wiley & Sons.

Finn, S. E., & Kamphuis, J. H. (2006). Therapeutic Assessment With the MMPI-2. In J. N. Butcher (Ed.), MMPI-2: A practitioner's guide (pp. 165–191). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11287-008

Finn, S. E., & Tonsager, M. E. (1992). Therapeutic effects of providing MMPI-2 test feedback to college students awaiting therapy. Psychological Assessment, 4 (3), 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.4.3.278

Finn, S. E., & Tonsager, M. E. (1997). Information-gathering and therapeutic models of assessment: Complementary paradigms. Psychological Assessment, 9 (4), 374–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.9.4.374

Finn, S. E., & Tonsager, M. E. (2002). How therapeutic assessment became humanistic. The Humanistic Psychologist, 30 (1-2), 10–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873267.2002.9977019

Fischer, C. (2000). Collaborative, individualized assessment. Journal of Personality Assessment, 74 (1), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa740102

Fischer, C. T. (1970). The testee as co-evaluator. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 17 (1), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0028630

Fischer, C. T. (1972). Paradigm changes which allow sharing of results. Professional Psychology, 3 (4), 364–369. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0033991

Fischer, C. T. (1978). Collaborative psychological assessment. In C. T. Fischer & S. L. Brodsky (Eds.), Client participation in human services (pp. 41–61). Transaction Books.

Fischer, C. T. (1985/1994). Individualizing psychological assessment . Erlbaum.

Fischer, C. T. (1994). Rorschach scoring questions as access to dynamics. Journal of Personality Assessment, 62 , 515–525.

Fischer, R. A. (1979). The inductive-deductive controversy revisited. The Modern Language Journal, 63 (3), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1979.tb02433.x

Fonagy, P., Luyten, P., & Allison, E. (2015). Epistemic petrification and the restoration of epistemic trust: A new conceptualization of borderline personality disorder and ITS psychosocial treatment. Journal of Personality Disorders, 29 (5), 575–609. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2015.29.5.575

Gelso, C. J., Nutt Williams, E., & Fretz, B. R. (2014). Counseling psychology (3rd ed.). American Psychological Association.

Goldfried, M. R. (1980). Toward the delineation of therapeutic change principles. American Psychologist, 35 , 991–999. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.35.11.991

Goldman, L. (1961). Using tests in counseling . Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Goldman, L. (1971). Using tests in counseling (2nd ed.). Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Gorske, T. T., & Smith, S. R. (2009). Collaborative therapeutic neuropsychological assessment . Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Gorske, T. T., & Smith, S. R. (2012). Case studies in collaborative neuropsychology: A man with brain injury and a child with learning problems. In S. E. Finn, C. T. Fischer, & L. Handler (Eds.), Collaborative therapeutic assessment: A casebook and guide (pp. 401–417). John Wiley & Sons.

Green, D., & Latchford, G. (2012). Maximising the benefits of psychotherapy . John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119967590

Hannan, C., Lambert, M. J., Harmon, C., Nielsen, S. L., Smart, D. W., Shimokawa, K., & Sutton, S. W. (2005). A lab test and algorithms for identifying clients at risk for treatment failure. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61 (2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20108

Hanson, W. E. (1999, August). Using psychological assessment instruments (effectively) with clients. In W. E. Hanson & C. E. Watkins, Jr. (Co-Chairs), Psychological assessment training and practice: Considerations for the 21st century. Symposium conducted at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, Boston, MA.

Hanson, W. E. (2013). Teaching therapeutic assessment practicum. Therapeutic Assessment, 1 (2), 7–12.

Hanson, W. E., Leighton, J. P., Donaldson, S. I., Oakland, T., Terjesen, M., & Shealy, C. N. (in press). Assessment: The power and potential of psychological testing, educational measurement, and program evaluation around the world. In C. N. Shealy, M. Bullock, S. Kapadia (Eds.), Going global: How psychology and psychologists can meet a world in need . American Psychological Association Books.

Hanson, W. E., & Poston, J. M. (2011). Building confidence in psychological assessment as a therapeutic intervention: An empirically based reply to Lilienfeld, garb, and wood (2011). Psychological Assessment, 23 (4), 1056–1062. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025656

Harmon, S. C., Lambert, M. J., Smart, D. M., Hawkins, E., Nielsen, S. L., Slade, K., & Lutz, W. (2007). Enhancing outcome for potential treatment failures: Therapist–client feedback and clinical support tools. Psychotherapy Research, 17 (4), 379–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300600702331

Harrower, M. (1956). Projective counseling—A psychotherapeutic technique. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 10 (1), 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1956.10.1.74

Haverkamp, B. E. (2012). The counseling relationship . Oxford Handbooks Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195342314.013.0003

Haverkamp, B. E. (2013). Education and training in assessment for professional psychology: Engaging the reluctant student. In K. F. Geisinger (Ed.), APA handbook on testing and assessment in psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 63–82). Testing and assessment in clinical and counseling psychology. American Psychological Association.

Haynes, S. N., Smith, G. T., & Hunsley, J. D. (2011). Scientific foundations of clinical assessment . Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203829172

Hilsenroth, M. J., Peters, E. J., & Ackerman, S. J. (2004). The development of therapeutic alliance during psychological assessment: Patient and therapist perspectives across treatment. Journal of Personality Assessment, 83 (3), 332–344. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa830314

Hinrichs, J. (2016). Inpatient therapeutic assessment with narcissistic personality disorder. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98 (2), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2015.1075997

Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1986). The development of the working alliance inventory. In L. S. Greenberg & W. M. Pinsoff (Eds.), The psychotherapeutic process: A research handbook (pp. 529–556). Guilford Press.

Hovland, R. T., Ytrehus, S., Mellor-Clark, J., & Moltu, C. (2020). How patients and clinicians experience the utility of a personalized clinical feedback system in routine practice. Journal of Clinical Psychology . https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22992

Howard, K. I., Moras, K., Brill, P. L., Martinovich, Z., & Lutz, W. (1996). Evaluation of psychotherapy: Efficacy, effectiveness, and patient progress. American Psychologist, 51 (10), 1059–1064. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.51.10.1059

Jacobson, R. M., Hanson, W. E., & Zhou, H. (2015). Canadian psychologists’ test feedback training and practice: A national survey. Canadian Psychology, 56 (4), 394–404. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000037

Jensen-Doss, A., Haimes, E. M. B., Smith, A. M., Lyon, A. R., Lewis, C. C., Stanick, C. F., & Hawley, K. M. (2018). Monitoring treatment progress and providing feedback is viewed favorably but rarely used in practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45 (1), 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0763-0

Jobes, D. A. (2012). The collaborative assessment and management of suicidality (CAMS): An evolving evidenced-based clinical approach to suicidal risk. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 42 (6), 640–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278x.2012.00119.x

Jobes, D. A., Wong, S. A., Conrad, A. K., Drozd, J. F., & Neal-Walden, T. (2005). The collaborative assessment and management of suicidality versus treatment as usual: A retrospective study with suicidal outpatients. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 35 (5), 483–497. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2005.35.5.483

Kamphuis, J. H., & Finn, S. E. (2018). Therapeutic assessment in personality disorders: Toward the restoration of epistemic trust. Journal of Personality Assessment, 101 (6), 662–674. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2018.1476360

Kendrick, T., El-Gohary, M., Stuart, B., Gilbody, S., Churchill, R., Aiken, L., Bhattacharya, A., Gimson, A., Brütt, A. L., de Jong, K., & Moore, M. (2016). Routine use of patient reported outcome measures (proms) for improving treatment of common mental health disorders in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd011119.pub2

Kohut, H. (1977). The restoration of the self . International Universities Press.

La Guardia, J. G., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79 , 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.79.3.367

Lambert, M. J. (2013). Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (6th ed.). Wiley & Sons.

Lambert, M. J. (2017). Maximizing psychotherapy outcome beyond evidence-based practice. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 86 , 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1159/000455170

Lambert, M. J., Hansen, N. B., & Finch, A. E. (2001b). Patient-focused research: Using patient outcome data to enhance treatment effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69 (2), 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.69.2.159

Lambert, M. J., Whipple, J. L., & Kleinstäuber, M. (2018). Collecting and delivering progress feedback: A meta-analysis of routine outcome monitoring. Psychotherapy, 55 (4), 520–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000167

Lambert, M. J., Whipple, J. L., Smart, D. W., Vermeersch, D. A., Nielsen, S. L., & Hawkins, E. J. (2001a). The effects of providing therapists with feedback on patient progress during psychotherapy: Are outcomes enhanced? Psychotherapy Research, 11 (1), 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/713663852

Lambert, M. J., Whipple, J. L., Vermeersch, D. A., Smart, D. W., Hawkins, E. J., Nielsen, S. L., & Goates, M. (2002). Enhancing psychotherapy outcomes via providing feedback on client progress: A replication. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 9 (2), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.324

Lichtenberg, J. W., & Goodyear, R. K. (1999). A scientist-practitioner perspective on test interpretation. In J. W. Lichtenbeg & R. K. Goodyear (Eds.), Scientist-practitioner perspectives on test interpretation (pp. 1–14). Allyn & Bacon.

Little, J. A. (2009). Collaborative assessment, supportive psychotherapy, or treatment as usual: An analysis of ultra -brief individualized intervention for psychiatric inpatients (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Quest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order No. 3375557). http://login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/docview/304853926?accountid=14474

Luborsky, L. (1953). Intraindividual repetitive measurements (p technique) in understanding psychotherapeutic change. Psychotherapy: Theory and Research. , 389–413. https://doi.org/10.1037/10572-015

Lutz, W., Rubel, J., Schiefele, A.-K., Zimmermann, D., Böhnke, J. R., & Wittmann, W. W. (2015). Feedback and therapist effects in the context of treatment outcome and treatment length. Psychotherapy Research, 25 (6), 647–660. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1053553

Meyer, G. J., Finn, S. E., Eyde, L. D., Kay, G. G., Moreland, K. L., Dies, R. R., Eisman, E. J., Kubiszyn, T. W., & Reed, G. M. (2001). Psychological testing and psychological assessment: A review of evidence and issues. American Psychologist, 56 (2), 128–165. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.56.2.128

Mikeal, C. W., Gillaspy, J. A., Scoles, M. T., & Murphy, J. J. (2016). A dismantling study of the partners for change outcome management system. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63 (6), 704–709. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000168

Morey, L. C., Lowmaster, S. E., & Hopwood, C. J. (2010). A pilot study OF manual-assisted cognitive therapy with a therapeutic assessment augmentation for borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Research, 178 (3), 531–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2010.04.055

Newman, M. L., & Greenway, P. (1997). Therapeutic effects of providing MMPI-2 test feedback to clients at a university counseling service: A collaborative approach. Psychological Assessment, 9 (2), 122–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.4.3.278

Pascual-Leone, A., & Andreescu, C. (2013). Repurposing process measures to train psychotherapists: Training outcomes using a new approach. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 13 (3), 210–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2012.739633

Pascual-Leone, A., Singh, T., Harrington, S., & Yeryomenko, N. (2014). Psychotherapy progress and process assessment. In C. J. Hopwood & R. F. Bornstein (Eds.), Multimethod clinical assessment of personality and psychopathology (pp. 319–344). Guilford Press.

Pinner, D. H., & Kivlighan, D. M., III. (2018). The ethical implications and utility of routine outcome monitoring in determining boundaries of competence in practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 49 (4), 247–254. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000203

Poston, J. M., & Hanson, W. E. (2010). Meta-analysis of psychological assessment as a therapeutic intervention. Psychological Assessment, 22 (2), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018679

Prescott, D. S., Maeschalck, C. L., & Miller, S. D. (Eds.). (2017). Feedback informed treatment in clinical practice—Reaching for excellence . American Psychological Association.

Probst, T., Lambert, M. J., Dahlbender, R. W., Loew, T. H., & Tritt, K. (2014). Providing patient progress feedback and clinical support tools to therapists: Is the therapeutic process of patients on-track to recovery enhanced in psychosomatic in-patient therapy under the conditions of routine practice? Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 76 (6), 477–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.03.010

Purves, C. (2002). Collaborative assessment with involuntary populations: Foster children and their mothers. The Humanistic Psychologist, 30 , 164–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873267.2002.9977031

Rousmaniere, T. (2017, April). What your therapist doesn’t know. The Atlantic . Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/04/what-your-therapist-doesnt-know/517797/

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55 , 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/003-066X.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2008). A self-determination theory approach to psychotherapy: The motivational basis for effective change. Canadian Psychology, 49 , 186–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012753

Rye, M., Rognmo, K., Aarons, G. A., & Skre, I. (2019). Attitudes towards the use of routine outcome monitoring of psychological therapies among mental health providers: The EBPAS-ROM. Administration and Policy Mental Health and Health Service Delivery, 46 (6), 833–846. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00968-5

Sagan, C. (1995). Wonder and skepticism. Skeptical Inquirer. Retrieved from https://www.e-reading-lib.com/bookreader.php/148586/Sagan_-_Wonder_and_Skepticism.pdf

Schuman, D. L., Slone, N. C., Reese, R. J., & Duncan, B. (2015). Efficacy of client feedback in group psychotherapy with soldiers referred for substance abuse treatment. Psychotherapy Research, 25 (4), 396–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2014.900875

She, Z., Duncan, B. L., Reese, R. J., Sun, Q., Shi, Y., Jiang, G., Wu, C., & Clements, A. L. (2018). Client feedback in China: A randomized clinical trial in a college counseling center. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65 (6), 727–737. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000300

Smith, M. L., Glass, G. V., & Miller, T. I. (1980). The benefits of psychotherapy . Johns Hopkins University Press.

Smith, J. D., Handler, L., & Nash, M. R. (2010). Therapeutic assessment for preadolescent boys with oppositional defiant disorder: A replicated single-case timeseries design. Psychological Assessment, 22 (3), 593–602. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019697

Snyder, C. R., Sympson, S. C., Ybasco, F. C., Borders, T. F., Babyak, M. A., & Higgins, R. L. (1996). Development and validation of the state Hope scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70 (2), 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.321

Solstad, S. M., Castonguay, L. G., & Moltu, C. (2019). Patients’ experiences with routine outcome monitoring and clinical feedback systems: A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative empirical literature. Psychotherapy Research, 29 (2), 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1326645

Stewart-Brown, S., & Janmohamed, K. (2008). Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): User guide (Version 1). Retrieved from http://www.mentalhealthpromotion.net/resources/user-guide.pdf

Stiles, W. B. (1980). Measurement of the impact of psychotherapy sessions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 48 (2), 176–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.48.2.176

Stiles, W. B., Gordan, L. E., & Lani, J. A. (2002). Session evaluation and the session evaluation questionnaire. In G. S. Tryon (Ed.), Counseling based on process research—Applying what we know (pp. 325–343). Allyn & Bacon.

Stiles, W. B., & Snow, J. S. (1984a). Counseling session impact as viewed by novice counselors and their clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31 (1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.31.1.3

Stiles, W. B., & Snow, J. S. (1984b). Dimensions of psychotherapy session impact across sessions and across clients. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 23 (1), 59–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1984.tb00627.x

Stolorow, R. D., & Atwood, G. E. (1984). Psychoanalytic phenomenology: Toward a science of human experience. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 4 (1), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/07351698409533532

Stolorow, R. D., Brandchaft, B., & Atwood, G. E. (1987). Psychoanalytic treatment: An intersubjective approach . Analytic Pr.

Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry . Norton.

Sullivan, H. S. (1954). The psychiatric interview . Norton.

Sundet, R. (2012). Therapist perspectives on the use of feedback on process and outcome: Patient-focused research in practice. Canadian Psychology, 53 (2), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027776

Sundet, R. (2014). Patient-focused research supported practices in an intensive family therapy unit. Journal of Family Therapy, 36 (2), 195–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2012.00613.x

Swann, W. B. (1997). The trouble with change: Self-verification and allegiance to the self. Psychological Science, 8 (3), 177–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00407.x

Tasca, G. A., Angus, L., Bonli, R., Drapeau, M., Fitzpatrick, M., Hunsley, J., & Knoll, M. (2019). Outcome and progress monitoring in psychotherapy: Report of a Canadian psychological association task force. Canadian Psychology, 60 (3), 165–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000181

Tasca, G. A., Town, J. M., Abbass, A., & Clarke, J. (2018). Will publicly funded psychotherapy in Canada be evidence based? A review of what makes psychotherapy work and a proposal. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Cannadienne, 59 (4), 293–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000151

Tharinger, D. J., Christopher, G., & Matson, M. (2011). Play, playfulness, and creative expression in therapeutic assessment with children. In S. W. Russ & L. N. Niec (Eds.), An evidence-based approach to play in intervention and prevention: Integrating developmental and clinical science (pp. 109–148). Guilford Press.

Tharinger, D. J., Finn, S. E., Arora, P., Judd-Glossy, L., Ihorn, S. M., & Wan, J. T. (2012). Therapeutic assessment with children: Intervening with parents “behind the mirror”. Journal of Personality Assessment, 94 (2), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2011.645932

Tharinger, D. J., Finn, S. E., Austin, C. A., Gentry, L. B., Bailey, K. E., Parton, V. T., & Fisher, M. E. (2008). Family sessions as part of child psychological assessment: Goals, techniques, clinical utility, and therapeutic value. Journal of Personality Assessment, 90 (6), 547–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802388400

Tiegreen, J. A., Braxton, L. E., Elbogen, E. B., & Bradford, D. (2012). Building a bridge of trust: Collaborative assessment with a person with serious mental illness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 94 (5), 513–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2012.666596

Tracey, T. J., Glidden, C. E., & Kokotovic, A. M. (1988). Factor structure of the counselor rating form-short. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 35 (3), 330–335. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.35.3.330

Truscott, D. (2019). Every breath you take: Ethical considerations regarding health care metrics. Health Ethics Today, 27 (1), 14–19.

Unsworth, G., Cowie, H., & Green, A. (2012). Therapists’ and clients’ perceptions of routine outcome measurement in the NHS: A qualitative study. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 12 (1), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2011.565125

van Oenen, F. J., Schipper, S., Van, R., Shoevers, R., Visch, I., Peen, J., & Dekker, J. (2016). Feedback-informed treatment in emergency psychiatry: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 16 , 110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0811-z

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Walfish, S., McAlister, B., O’Donnell, P., & Lambert, M. J. (2012). An investigation of self-assessment bias in mental health providers. Psychological Reports, 110 (2), 639–644. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.07.17.pr0.110.2.639-644

Wampold, B. E. (2015). Routine outcome monitoring: Coming of age—With the usual developmental challenges. Psychotherapy, 52 (4), 458–462. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000037

Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2015). The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work . Routledge.

Whipple, J. L., Lambert, M. J., Vermeersch, D. A., Smart, D. W., Nielsen, S. L., & Hawkins, E. J. (2003). Improving the effects of psychotherapy: The use of early identification of treatment and problem-solving strategies in routine practice. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50 (1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.50.1.59

Wolf, N. J. (2010). Evaluating the effectiveness of therapeutic assessment with depressed adult clients using case-based time-series design. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Tennessee. Retrieved from https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/925

Zhou, H. (2021). Therapists’ use of routine outcome monitoring in clinical practice: A qualitative multiple case study. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB.

Zhou, H., Hanson, W. E., Jacobson, R., Allan, A., Armstrong, D., Dykshoorn, K. L., & Pott, T. (2020). Psychological test feedback: Canadian clinicians’ perceptions and practices. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 54 (4), 691–714. https://doi.org/10.47634/cjcp.v54i4.61217

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1998). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52 (1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Concordia University of Edmonton, Edmonton, AB, Canada

William E. Hanson

University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

Hansen Zhou

Alberta Health Services and University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

Diana L. Armstrong

Blue Sky Psychology Group, and University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

Noëlle T. Liwski

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to William E. Hanson .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Werklund School of Education, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

Jac J.W. Andrews

Department of Educational and Counselling Psychology, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

Steven R. Shaw

José F. Domene

Carly McMorris

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Hanson, W.E., Zhou, H., Armstrong, D.L., Liwski, N.T. (2022). A Humanistic Approach to Mental Health Assessment, Evaluation, and Measurement-Based Care. In: Andrews, J.J., Shaw, S.R., Domene, J.F., McMorris, C. (eds) Mental Health Assessment, Prevention, and Intervention. The Springer Series on Human Exceptionality. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97208-0_17

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97208-0_17

Published : 13 July 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-97207-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-97208-0

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Humanistic Psychology’s Approach to Wellbeing: 3 Theories

That sounds quite nice, doesn’t it? Let’s repeat that again.

Humans are innately good.

Driving forces, such as morality, ethical values, and good intentions, influence behavior, while deviations from natural tendencies may result from adverse social or psychological experiences, according to the premise of humanistic psychology.

What does it mean to flourish as a human being? Why is it important to achieve self-actualization? And what is humanistic psychology, anyway?

Humanistic psychology has the power to provide individuals with self-actualization, dignity, and worth. Let’s see how that works in this article.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Meaning and Valued Living Exercises for free . These creative, science-based exercises will help you learn more about your values, motivations, and goals and will give you the tools to inspire a sense of meaning in the lives of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

What is the humanistic psychology approach, brief history of humanistic psychology, 10 real-life examples in therapy & education, popular humanistic theories of wellbeing, humanistic psychology and positive psychology, 4 techniques for humanistic therapists, 4 common criticisms of humanistic psychology, fascinating books on the topic, more resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message.

Humanistic psychology is a holistic approach in psychology that focuses on the whole person. Humanists believe that a person is “in the process of becoming,” which places the conscious human experience as the nucleus of psychological establishment.

Humanistic psychology was developed to address the deficiencies of psychoanalysis , psychodynamic theory , and behaviorism . The foundation for this movement is understanding behavior by means of human experience.

This entity of psychology takes a phenomenological stance, where personality is studied from an individual’s subjective point of view.

Key focus of humanistic psychology

The tenets of humanistic psychology, which are also shared at their most basic level with transpersonal and existential psychology, include:

- Humans cannot be viewed as the sum of their parts or reduced to functions/parts.

- Humans exist in a unique human context and cosmic ecology.

- Human beings are conscious and are aware of their awareness.

- Humans have a responsibility because of their ability to choose.

- Humans search for meaning, value, and creativity besides aiming for goals and being intentional in causing future events (Aanstoos et al., 2000).

In sum, the focus of humanistic psychology is on the person and their search for self-actualization .

At this time, humanistic psychology was considered the third force in academic psychology and viewed as the guide for the human potential movement (Taylor, 1999).

The separation of humanistic psychology as its own category was known as Division 32. Division 32 was led by Amedeo Giorgi, who “criticized experimental psychology’s reductionism, and argued for a phenomenologically based methodology that could support a more authentically human science of psychology” (Aanstoos et al., 2000, p. 6).

The Humanistic Psychology Division (32) of the American Psychological Association was founded in September 1971 (Khan & Jahan, 2012). Humanistic psychology had not fully emerged until after the radical behaviorism era; however, we can trace its roots back to the philosophies of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger.

Husserl spurred the phenomenological movement and suggested that theoretical assumptions be set aside, and philosophers and scientists should instead describe immediate experiences of phenomena (Schneider et al., 2015).

Who founded humanistic psychology?

The first phase of humanistic psychology, which covered the period between 1960 to 1980, was largely driven by Maslow’s agenda for positive psychology . It articulated a view of the human being as irreducible to parts, needing connection, meaning, and creativity (Khan & Jahan, 2012).

The original theorists of humanistic theories included Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, and Rollo May, who postulated that behaviorism and psychoanalysis were inadequate in explaining human nature (Schneider et al., 2015).

Prior to these researchers, Allport, Murray, and Murphy had protested the reductionist movement, including the white laboratory rat as a method for comparing human behavior (Schneider et al., 2015). Influential women in the development of this branch of psychology included Frieden and Criswell (Serlin & Criswell, 2014).

Carl Rogers’s work

Carl Rogers developed the concept of client-centered therapy , which has been widely used for over 40 years (Carter, 2013). This type of therapy encourages the patient toward self-actualization through acceptance and empathetic listening by the therapist. This perspective asserts that a person is fully developed if their self is aligned with their organism (Robbins, 2008).

In other words, a fully functioning person is someone who is self-actualized. This concept is important, as it presents the need for therapy as a total experience.

Rogers’s contribution assisted the effectiveness of person-centered therapy through his facilitation of clients reaching self-actualization and fully functional living. In doing so, Rogers focused on presence, congruence, and acceptance by the therapist (Aanstoos et al., 2000).

The Humanistic Theory by Carl Rogers – Mister Simplify

The human mind is not just reactive; it is reflective, creative, generative, and proactive (Bandura, 2001). With this being said, humanistic psychology has made major impacts in therapeutic and educational settings.

Humanistic psychology in therapy

The humanistic, holistic perspective on psychological development and self-actualization provides the foundation for individual and family counseling (Khan & Jahan, 2012). Humanistic therapies are beneficial because they are longer, place more focus on the client, and focus on the present (Waterman, 2013).

Maslow and Rogers were at the forefront of delivering client-centered therapy as they differentiated between self-concept as understanding oneself, society’s perception of themselves, and actual self. This humanistic psychological approach provides another method for psychological healing and is viewed as a more positive form of psychology. Rogers “emphasized the personality’s innate drive toward achieving its full potential” (McDonald & Wearing, 2013, p. 42–43).

Other types of humanistic-based therapies include:

- Logotherapy is a therapeutic approach aimed at helping individuals find the meaning of life. This technique was created by Victor Frankl, who posited that to live a meaningful life, humans need a reason to live (Melton & Schulenberg, 2008).

- Gestalt Therapy’s primary aim is to restore the wholeness of the experience of the person, which may include bodily feelings, movements, emotions, and the ability to creatively adjust to environmental conditions. This type of therapy is tasked with providing the client with awareness and awareness tools (Yontef & Jacobs, 2005). This includes the use of re-enactments and role-play by empowering awareness in the present moment.

- Existential Therapy aims to aid clients in accepting and overcoming the existential fears inherent in being human. Clients are guided in learning to take responsibility for their own choices. Rather than explaining the human predicament, existential therapy techniques involve exploring and describing the conflict.

- Narrative Therapy is goal directed, with change being achieved by exploring how language is used to construct and maintain problems. The method involves the client’s narrative interpretation of their experience in the world (Etchison & Kleist, 2000).

Humanistic psychology has developed a variety of research methodologies and practice models focused on facilitating the development and transformation of individuals, groups, and organizations (Resnick et al., 2001).

The methodologies include narrative, imaginal, and somatic approaches. The practices range from personal coaching and organizational consulting through creative art therapies to philosophy (Resnick et al., 2001).

Humanistic approach in education

The thoughts of Dewey and Bruner regarding the humanistic movement and education greatly affect education today. Dewey proclaimed that schools should influence social outcomes by teaching life skills in a meaningful way (Starcher & Allen, 2016).

Bruner was an enthusiast of constructivist learning and believed in making learners autonomous by using methods such as scaffolding and discovery learning (Starcher & Allen, 2016).

Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences (Resnick et al., 2001) asserts that there are eight different types of intelligence: linguistic, logical/mathematical, spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and naturalist. In education, it is important for educators to address as many of these areas as possible.

These psychologists soon set the tone for a more intense focus on humanistic skills, such as self-awareness, communication, leadership ability, and professionalism. Humanistic psychology impacts the educational system with its perspectives on self-esteem and self-help (Khan & Jahan, 2012; Resnick et al., 2001).

Maslow extended this outlook with his character learning (Starcher & Allen, 2016). Character learning is a means for obtaining good habits and creating a moral compass. Teaching young children morality is paramount in life (Birhan et al., 2021).

In concentrating on these aspects, the focus is placed on the future, self-improvement, and positive change. Humanistic psychology rightfully provides individuals with self-actualization, dignity, and worth.

Silvan Tomkins theorized the script theory, which led to the advancement of personality psychology and opened the door to many narrative-based theories involving myths, plots, episodes, character, voices, dialogue, and life stories (McAdams, 2001).

Tomkins’s affect theory followed this theory and explains human behavior as falling into scripts or patterns. It appears as though this theory’s acceptance led to many more elements of experience being considered (McAdams, 2001).

Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs has contributed much to humanistic psychology and impacts mental and physical health . This pyramid is frequently used within the educational system, specifically for classroom management purposes. In the 1960s and 1970s, this model was expanded to include cognitive, aesthetic, and transcendence needs (McLeod, 2017).

Maslow’s focus on what goes right with people as opposed to what goes wrong with them and his positive accounts of human behavior benefit all areas of psychology.

Download 3 Meaning & Valued Living Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to find meaning in life help and pursue directions that are in alignment with values.

Download 3 Free Meaning Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Although humanistic psychology and positive psychology share the basic ideas of psychological wellbeing – the intent to achieve individual human potential and a humanistic framework – their origins are quite different (Medlock, 2012). Humanistic psychology adds two important elements to the establishment of positive psychology: epistemology and its audience (Taylor, 2001).

Humanistic psychology and positive psychology share many overlapping thematic contents and theoretical presuppositions (Robbins, 2008).

Much of the work in positive psychology was developed from the work in humanistic psychology (Medlock, 2012). Positive psychology was also first conceived by Maslow in 1954 and then further discussed in an article by Martin Seligman (Shourie & Kaur, 2016).

Seligman’s purpose for positive psychology was to focus on the characteristics that make life worth living as opposed to only studying the negatives, such as mental illness (Shrestha, 2016).

Congruence refers to both the intra- and interpersonal characteristics of the therapist (Kolden et al., 2011).

This requires the therapist to bring a mindful genuineness and conscientiously share their experience with the client.

Active listening

Active listening helps to foster a supportive environment. For example, response tokens such as “uh-huh” and “mm-hmm” are effective ways to prompt the client to continue their dialogue (Fitzgerald & Leudar, 2010).

Looking at the client, nodding occasionally, using facial expressions, being aware of posture, paraphrasing, and asking questions are also ways to maintain active listening.

Reflective understanding

Similar to active listening, reflective understanding includes restating and clarifying what the client is saying. This technique is important, as it draws the client’s awareness to their emotions, allowing them to label. Employing Socratic questioning would ensure a reflective understanding in your practice (Bennett-Levy et al., 2009).

Unconditional positive regard

Unconditional positive regard considers the therapist’s attitude toward the patient. The therapist’s enduring warmth and consistent acceptance shows their value for humanity and, more specifically, their client.

Some may assert that humanistic psychology is not exclusively defined by the senses or intellect (Taylor, 2001).

Humanistic psychology was also once thought of as a touchy-feely type of psychology. Instead, internal dimensions such as self-knowledge, intuition, insight, interpreting one’s dreams, and the use of guided mental imagery are considered narcissistic by critics of humanistic psychology (Robbins, 2008; Taylor, 2001).

Further, studying internal conditions, such as motives or traits, was frowned upon at one time (Polkinghorne, 1992).

Aanstoos et al. (2000) note Skinner’s thoughts concerning humanistic psychology as being the number one barrier in psychology’s stray from a purely behavioral science. Religious fundamentalists were also opposed to this new division and referred to people of humanistic psychology as secular humanists.

Humanistic psychology is sometimes difficult to assess and has even been charged as being poor empirical science (DeRobertis, 2021). That is because of the uncommon belief that the outcome should be driven more by the participants rather than the researchers (DeRobertis & Bland, 2021).

If you find this topic intriguing and want to find out even more, then take a look at the following books.

1. Becoming an Existential-Humanistic Therapist: Narratives From the Journey – Julia Falk and Louis Hoffman

If you’re interested in becoming an existential-humanistic psychologist or counselor, you may want to refer to this collection of therapists and counselors who have already made this journey.

Perhaps you are a student who is considering pursuing this direction in psychology.

Regardless, this book contains reflective exercises for individuals considering pursuing a career as an existential-humanistic counselor or therapist, as well as exercises for current therapists to reflect on their own journey.

Find the book on Amazon .

2. On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy – Carl Rogers

If your intent is to explore client-centered therapy more in depth, you may want to pick up this book by one of humanistic psychology’s founders.

In this text, Rogers sheds light on this important therapeutic encounter and human potential.

3. Man’s Search for Meaning – Viktor Frankl

Also by one of humanistic psychology’s founders, Man’s Search for Meaning provides an explanation of Logotherapy.

With his actual horrific experiences in Nazi concentration camps, Frankl declares that humans’ primary drive in life is not pleasure, but the discovery and pursuit of what they personally find meaningful.

If you’re interested in learning more about the history of humanistic psychology, our article The Five Founding Fathers and a History of Positive Psychology would be an excellent reference, as the roots of humanistic and positive psychology are entangled.

In humanistic psychology, self-awareness and introspection are important. Try using our Self-Awareness Worksheet for Adults to learn more about yourself and increase your self-knowledge.

Journaling is an effective way to boost your internal self-awareness. Try using this Gratitude Journal and Who Am I? worksheet as starting points.

Perhaps you would benefit from our science and research-driven 17 Meaning & Valued Living Exercises . Use them to help others choose directions for their lives in alignment with what is truly important to them.

17 Tools To Encourage Meaningful, Value-Aligned Living

This 17 Meaning & Valued Living Exercises [PDF] pack contains our best exercises for helping others discover their purpose and live more fulfilling, value-aligned lives.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Humanistic psychology is a total package because it encompasses legends of the field, empirical research, strong philosophical foundations, and arts and literature connections (Bargdill, 2011).

Some may refute this statement, but prior to humanistic psychology, there was not an effective method for truly understanding humanistic issues without deviating from traditional psychological science (Kriz & Langle, 2012).

Humanistic psychology offers a different approach that can be used to positively impact your therapeutic practice or enhance your classroom practice. We hope you find these theories and techniques helpful in facilitating self-actualization, dignity, and worth in your clients and students.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Meaning and Valued Living Exercises for free .

- Aanstoos, C. M., Serlin, I., & Greening, T. (2000). A history of division 32: Humanistic psychology. In D. A. Dewsbury (Ed.). History of the divisions of APA (pp. 85–112). APA Books.

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology , 52 , 1–26.

- Bargdill, R. (2011). The youth movement in humanistic psychology. Humanistic Psychologist , 39 (3), 283–287.

- Bennett-Levy, J., Thwaites, R., Chaddock, A., & Davis, M. (2009). Reflective practice in cognitive behavioural therapy: the engine of lifelong learning. In R. Dallos & J. Stedmon (Eds.), Reflective practice in psychotherapy and counselling (pp. 115–135). Open University Press.

- Birhan, W., Shiferaw, G., Amsalu, A., Tamiru, M., & Tiruye, H. (2021). Exploring the context of teaching character education to children in preprimary and primary schools. Social Sciences & Humanities Open , 4 (1), 100171.

- Carter, S. (2013). Humanism . Research Starters: Education.

- Corbett, L., & Milton, M. (2011). Existential therapy: A useful approach to trauma? Counselling Psychology Review , 26 (1), 62–74.

- DeRobertis, E. M. (2021). Epistemological foundations of humanistic psychology’s approach to the empirical. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology . Advance online publication.

- DeRobertis, E. M., & Bland, A. M. (2021). Humanistic and positive psychologies: The continuing narrative after two decades. Journal of Humanistic Psychology .

- Etchison, M., & Kleist, D. M. (2000). Review of narrative therapy: Research and utility. The Family Journal , 8 (1), 61–66.

- Falk, J., & Hoffman, L. (2022). Becoming an existential-humanistic therapist: Narratives from the journey. University Professors Press.

- Fitzgerald, P., & Leudar, I. (2010). On active listening in person-centred, solution-focused psychotherapy. Journal of Pragmatics , 42 (12), 3188–3198.

- Frankl, V. (2006). Man’s search for meaning. Beacon Press.

- Khan, S., & Jahan, M. (2012). Humanistic psychology: A rise for positive psychology. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology , 3 (2), 207–211.

- Kolden, G. G., Klein, M. H., Wang, C. C., & Austin, S. B. (2011). Congruence/genuineness. Psychotherapy , 48 (1), 65–71.

- Kriz, J., & Langle, A. (2012). A European perspective on the position papers. Psychotherapy , 49 (4), 475–479.

- McAdams, D. P. (2001). The psychology of life stories. Review of General Psychology , 5 (2), 100–122.

- McDonald, M., & Wearing, S. (2013). A reconceptualization of the self in humanistic psychology: Heidegger, Foucault and the sociocultural turn. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology , 44 (1), 37–59.

- McLeod, S. A. (2017). Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs . SimplyPsychology. Retrieved February 22, 2022, from www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html

- Medlock, G. (2012). The evolving ethic of authenticity: From humanistic to positive psychology. Humanistic Psychologist , 40 (1), 38–57.

- Melton, A. M., & Schulenberg, S. E. (2008). On the measurement of meaning: Logotherapy’s empirical contributions to humanistic psychology. The Humanistic Psychologist , 36 (1), 31–44.

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (1992). Research methodology in humanistic psychology. Humanistic Psychologist , 20 (2–3), 218–242.

- Resnick, S., Warmoth, A., & Serlin, I. A. (2001). The humanistic psychology and positive psychology connection: Implications for psychotherapy. Journal of Humanistic Psychology , 41 (1), 73–101.

- Robbins, B. D. (2008). What is the good life? Positive psychology and the renaissance of humanistic psychology. The Humanistic Psychologist , 36 (2), 96–112.

- Rogers, C. (1995). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. HarperOne.

- Schneider, K. J., Pierson, J. F., & Bugental, J. F. T. (Eds.). (2015). The handbook of humanistic psychology: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Serlin, I. A., & Criswell, E. (2014). Humanistic psychology and women. In K. J. Schneider, J. F. Pierson, & J. F. T. Bugental (Eds.), The handbook of humanistic psychology: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 27–40). SAGE.

- Shourie, S., & Kaur, H. (2016). Gratitude and forgiveness as correlates of well-being among adolescents. Indian Journal of Health & Wellbeing , 7 (8), 827–833.

- Shrestha, A. K. (2016). Positive psychology: Evolution, philosophical foundations, and present growth. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology , 7 (4), 460–465.

- Starcher, D., & Allen, S. L. (2016). A global human potential movement and a rebirth of humanistic psychology. Humanistic Psychologist , 44 (3), 227–241.

- Taylor, E. (1999). An intellectual renaissance of humanistic psychology? Journal of Humanistic Psychology , 39 (2), 7–25.

- Taylor, E. (2001). Positive psychology and humanistic psychology: A reply to Seligman. Journal of Humanistic Psychology , 41 (1), 13–29.

- Waterman, A. S. (2013). The humanistic psychology–positive psychology divide: Contrasts in philosophical foundations. American Psychologist , 68 (3), 124–133.

- Yontef, G., & Jacobs, L. (2005). Gestalt therapy. In R. J. Corsini & D. Wedding (Eds.), Current psychotherapies (pp. 299–336).

Share this article:

Article feedback

Let us know your thoughts cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Hierarchy of Needs: A 2024 Take on Maslow’s Findings

One of the most influential theories in human psychology that addresses our quest for wellbeing is Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. While Maslow’s theory of [...]

Emotional Development in Childhood: 3 Theories Explained

We have all witnessed a sweet smile from a baby. That cute little gummy grin that makes us smile in return. Are babies born with [...]

Using Classical Conditioning for Treating Phobias & Disorders

Does the name Pavlov ring a bell? Classical conditioning, a psychological phenomenon first discovered by Ivan Pavlov in the late 19th century, has proven to [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (15)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (43)

- Resilience & Coping (37)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (63)

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

3 Positive Psychology Tools (PDF)

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

How Humanistic Is Positive Psychology? Lessons in Positive Psychology From Carl Rogers' Person-Centered Approach—It's the Social Environment That Must Change

Associated data.

The original contributions generated for the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Both positive psychology and the person-centered approach share a common aim to promote human flourishing. In this article I will discuss how the person-centered approach is a form of positive psychology, but positive psychology is not necessarily person-centered. I will show how the person-centered approach offers a distinctive view of human nature that leads the person-centered psychologist to understand that if people are to change, it is not the person that we must try to change but their social environment. Centrally, the paper suggests that respecting the humanistic image of the human being and, consequently, influencing people's social environment to facilitate personal growth would mean a step forward for positive psychology and would promote cross-fertilization between positive psychology and the person-centered approach instead of widening their gap.

Introduction

It was in the late 1980's that I first became interested in what later became known as positive psychology. I was completing my doctorate research in the psychology of trauma. An unexpected finding was that many survivors reported positive changes in outlook. But there was little written in the mainstream literature about this. I wanted to find a language with which to frame my observations. Like many, I had studied humanistic psychology briefly in my undergraduate studies, but not in a way that I understood its depth and richness, so it came as a revelation to me when I discovered that the same intellectual challenges I was now grappling with, had been tackled decades ago.

Specifically, I began to see how Carl Rogers' person-centered theory of personality development could be applied to understanding how people grow following adversity. Throughout the 1990's, I studied Rogers' ideas coming to realize that what he and his colleagues had achieved from the 1950's onwards had offered a new paradigm for the psychological sciences, one that focused on how to promote human flourishing. As a result, when I first encountered positive psychology in the early 2000's, my initial reaction was to dismiss it as it seemed to offer nothing new, but I also saw the enthusiasm of my students for positive psychology, and that positive psychology was succeeding in bringing ideas about well-being back into mainstream awareness when person-centered psychology seemed to be struggling to do so. I could see that person-centered psychology was not incompatible with being interested in positive psychology, so I began to think of myself as a person-centered positive psychologist. For the past two decades I have sought to build bridges between humanistic and positive psychology, to bring the person-centered approach to my work on posttraumatic growth and authenticity, and to make the case that the person-centered approach is a form of positive psychology.

In this article I want to elaborate on what I mean when I say that the person-centered approach is a form of positive psychology. My aim is to position the person-centered approach as part of contemporary positive psychology, as well as it being part of the humanistic psychology tradition. Carl Rogers, the founder of the person-centered approach, was one of the pioneers of humanistic psychology. As such, the person-centered approach is often associated with humanistic psychology. While the relationship between humanistic and positive psychology has been contentious in the past, it is now widely accepted that positive psychology has largely followed in the footsteps of humanistic psychology. In this way, person-centered psychology can be seen as a historical antecedent to positive psychology, but what I want to show is that it is not just a branch of research, scholarship, and practice from the past; it is one that has continued and developed over the past 70 years, that now sits comfortably under the wider umbrella of positive psychology.

I would like to invite readers of this special issue to become more fully acquainted with person-centered psychology and to consider its perspective on what it means to be a positive psychologist. I will provide a brief overview of positive psychology in the context of humanistic psychology, followed by a discussion of the person-centered approach and how it offers a distinctive view of human nature, and finally, reflections on my vision for a more person-centered positive psychology. In short, the person-centered positive psychologist would look not at ways to change people but at how to change their social environment. I will show that considering the influence of the social environment as the means to facilitate personal growth would mean a step forward for positive psychology in a direction away from its individualistic and medicalized focus and would promote cross-fertilization between positive psychology and humanistic psychology. In making this argument I am reiterating and developing Linley and Joseph's ( 2004b ) conclusion in their book Positive Psychology in Practice that there is a need to develop a theoretical foundation for positive psychology that offers a clear, coherent, and consistent vision of human nature, and how the agenda for the practice of positive psychology inevitably arises out of its vision. Speaking personally, my vision would be for a more person-centered positive psychology.

Positive Psychology in the Context of Humanistic Psychology