124 Gender Stereotypes Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Whether you are writing an argumentative paper or an essay about your personal experience, you’ll find something useful on this page. Check out this list of 120 gender stereotypes research titles put together by our experts .

💭 Top 10 Gender Bias Essay Topics

🏆 best gender stereotypes essay topics, 🎓 simple & easy gender stereotypes research titles, 📌 most interesting ideas for a gender stereotypes essay, ❓ research questions about gender stereotypes.

- Gender roles and how they influence the society.

- The gender pay gap in white collar occupations.

- The harms of gender stereotyping in school.

- Inequality between men and women in politics.

- Differences in gender stereotypes in the East and West.

- Gender representation in children’s media.

- Breaking gender stereotypes through education.

- Sexism and gender bias.

- Traditional gender roles in Western society.

- Gender discrimination in healthcare.

- Gender Stereotypes in the “Frozen” and “Shrek” Movies The motivations of female characters in Disney movies are directly tied to the development of goals and ambitions because it is the source of these notions.

- The Smurfette Principle: Gender Stereotypes and Pop-Culture After watching “The Little Mermaid”, and reading “The Cat in the Hat”, Sophie is left disgusted by the peripheral role that female characters play in the media.

- Gender Stereotypes in “Million Dollar Baby” Movie In order to enter the world of boxing, Maggie, the main heroine of Million Dollars Baby, had to overcome the adversities connected with gender stereotypes.

- “The Blue Castle” by Lucy Maud Montgomery: Social Construction and Gender Stereotypes In the past decades, a female child in society had to be prepared for the roles of a mother and a wife to help her take care of the family when she gets married in […]

- Little Red Riding Hood: Breaking Gender Stereotypes On refusing marriage to the Roman prefect of the province, she was fed to Satan who came in the form of a dragon. By the time the wolf arrives, he cannot of course convince the […]

- Gender Stereotypes Found in Media The chosen image represents one of the most common gender biases women are obliged to do the chores because it is not men’s responsibility.

- Gender Stereotypes in Advertisement In addition, I think that this example has a negative contribution and can become harmful for limiting gender stereotypes due to the downplaying of the importance of women.

- Gender Stereotypes and Sexual Discrimination In this Ted Talk, Sandberg also raises a question regarding the changes that are needed to alter the current disbalance in the number of men and women that achieve professional excellence.

- Gender Stereotypes About Women Still Exist Given the fact that this is a whole intellectual sphere, the capabilities of males and females are equilibrated to the greatest extent.

- Media and Gender Stereotypes Against Females in Professional Roles Within the Criminal Justice The first and a half of the second episode were chosen as the pilot episode often reflects the essence of the entire show.

- Disney Princesses as Factors of Gender Stereotypes This research focused on determining the impact of Disney Princesses on of preschool age girls in the context of the transmission of gender stereotypes.

- Gender Stereotypes in Modern Society However, in this case, the problem is that because of such advertisements, men tend to achieve the shown kind of appearance and way of thinking.

- Femininity and Masculinity: Gender Stereotypes In conclusion, it is necessary to admit that femininity and masculinity are two sides of the same medal, and neither should be neglected.

- Sex and Gender Stereotypes: Similar and Different Points To conclude, the works by Devor and Rudacille touch upon the controversial topic of gender identification in the modern society. Nevertheless, both works are similar in their focus on the issues of sex, gender, sexuality, […]

- Problem of Gender Stereotypes in Weightlifting The Change paper is a combination of all the recommendations that can be useful in dealing with the problem of gender stereotypes in weightlifting.

- How Gender Stereotypes Affect Performance in Female Weightlifting One can therefore see that this decision reflected common perceptions among several stakeholders in the weightlifting industry and that the same is likely to occur in the future.

- “Bimbos and Rambos: The Cognitive Basis of Gender Stereotypes” by Matlin W.M. According to this theory, there exists a relationship between the cognitive processes of the brain and the beliefs that the individual leans and takes up according to his or her upbringing. The media tends to […]

- Gender Stereotypes and Human Emotions One of the easiest ways to check the connection between gender and emotions is to ask a person who prefers to demonstrate their emotions in public, a man or a woman.

- Gender Stereotypes and Influence on People’s Lives However, the overall development in human thought enhances the advancement in the framework of people’s understanding of the world around them.

- Gender Stereotyping Rates in the USA I do not feel that gender stereotypes in America are still strong because many women make more money than their husbands do nowadays, whereas men like to do housework and cook for their families.

- Gender Stereotypes: Interview with Dalal Al Rabah Women need a passion to succeed, to be of influence, and to make a difference in the daily living of their loved ones.

- Toxic Relationships and Gender Stereotypes According to the patient, they believe that a woman is responsible for the psychological climate and the psychological well-being of her husband.

- Confronting Gender Stereotypes It is imperative to confront the careless use of male and female stereotypes in order to preserve decency, community, and the lives of children and teenagers.

- Gender Stereotypes in Disney Princesses The evolvement of the princess image in the films of the studio represents the developing position of strong independent women in the society, but the princess stereotypes can harm the mentality of children.

- Gender Stereotypes in the Classroom Matthews notes that the teacher provides the opportunity for his students to control the situation by shaping the two groups. To reinforce the existing gender stereotypes in the given classroom, Mr.

- Dr. Stacy Smith’ View on Women Gender Stereotypes Stacy Smith, the author is unfortunate that despite the fact that population of men and women is equal, the womenfolk, the society is not really to accept this equality in assigning roles, even when a […]

- Influence of activating implicit gender stereotypes in females The results revealed that the participants who were subjected to the gender based prime performed relatively poorly compared to their counterparts on the nature prime.

- Towards Evaluating the Relationship Between Gender Stereotypes & Culture It is therefore the object of this paper to examine the relationship between gender stereotypes and culture with a view to elucidating how gender stereotypes, reinforced by our diverse cultural beliefs, continue to allocate roles […]

- How contemporary toys enforce gender stereotypes in the UK Children defined some of the physical attributes of the toys.”Baby Annabell Function Doll” is a likeness of a baby in that it that it has the size and physical features of a baby.

- Gender Studies: Gender Stereotypes From what is portrayed in the media, it is possible for people to dismiss others on the basis of whether they have masculinity or are feminine.

- Gender stereotypes of superheroes The analysis is based on the number of male versus female characters, the physical characteristic of each individual character, the ability to solve a problem individually as either male or female and both males and […]

- Gender Stereotypes on Television Gender stereotyping in television commercials is a topic that has generated a huge debate and it is an important topic to explore to find out how gender roles in voice-overs TV commercials and the type […]

- How Gender Stereotypes Are Portrayed On The Television Series

- Hollywood is a Vessel for Enforcing Gender Stereotypes

- Gender Stereotypes Of Early Childhood Education

- Gender Stereotypes Among Children’s Toys

- Color and Female Gender Stereotypes: What They Are, How They Came About and What They Mean

- An Analysis of Gender Stereotypes in Boys Don’t Cry, a Film by Kimberly Peirce

- The Role Media Plays In Relation To Gender Stereotypes

- Gender Stereotypes Of Media And Its Effect On Society

- English Postcolonial Animal Tales and Gender Stereotypes

- Gender Stereotypes : The Ugly Truth

- Gender Stereotypes and Discrimination in Sports and the Lack of Women in Leadership Position in Professional Sports

- Female Development and the Impact of Gender Stereotypes

- The Hidden Gender Stereotypes in the Animations the Little Mermaid and Tangled

- Gender Stereotypes In The Ordeal Of Gilbert Pinfold

- Gender Stereotypes And The Gender Of A Baby

- Gender Stereotypes in Advertising and the Media

- An Overview of Gender Stereotypes in the United States

- An Overview of Gender Stereotypes During Childhood

- The Issue of Gender Stereotypes and Its Contribution to Gender Inequality in the Second Presidential Debate

- The Impact of Gender Stereotypes in Commercial Advertisements on Family Dynamics

- How Does Gender Stereotypes Affect Today ‘s Society

- Gender Stereotypes on Television, Advertisements and Childrens Television Programs

- Gender Stereotypes in Non-Traditional Sports

- The Importance Of Gender Stereotypes

- How Do Gender Stereotypes Affect The Decisions Our Youth

- Gender Stereotypes in Movies and Their Influence on Gender Nonconforming Movies

- Stereotypes And Stereotypes Of Gender Stereotypes

- The Effects of Advertising in Reinforcing Gender Stereotypes

- Gender Differences and Gender Stereotypes from a Psychological Perspective

- An Analysis of Gender Differences and Gender Stereotypes

- Female Discourse and Gender Stereotypes in Eliot’s Novel

- As You Like It and Gender Stereotypes Based On Rosalind

- Gender Stereotypes Of Harry Potter And The Sorcerer ‘s Stone

- Gender Stereotypes in Achebe’s Dead Men’s Path

- Gender Stereotypes And Stereotypes Of A Child ‘s Play Sets

- Advertising and Gender Stereotypes: How Culture is Made

- Gender Stereotypes Are Challenged By Children And Adolescence

- Gender Stereotypes Of Advertising And Marketing Campaigns

- Does Mainstream Media Have a Duty to Challenge Gender Stereotypes

- A Social Constructivist Approach on the Heterosexual Matrix and Gender Stereotypes

- Gender Stereotypes of Women in Society, Sports, and Workforce

- The Factors That Influence Gender Roles, Gender Identity and Gender Stereotypes

- Gender Stereotypes And Its Effect On Society

- Are Gender Stereotypes Perpetuated In Children’s Magazines

- Gender Stereotypes And Gender Discrimination

- An Explanation of Gender Stereotypes from a Scene in the Movie, Tootsie

- An Analysis of Gender Stereotypes in Today’s Society

- Gender Stereotypes And The Credibility Of Newspaper Articles Associated

- Gender Stereotypes And Behaviors Of Men And Women

- Gender Stereotypes In Boys And Girls By Alice Munro

- Media Affects How We View Gender Stereotypes

- Media and Its Effects on Gender Stereotypes

- How Does Advertising Reinforce Gender Stereotypes?

- Are Gender Stereotypes Perpetuated in Children’s Magazines?

- How Do Contemporary Toys Enforce Gender Stereotypes in the UK?

- Can Gender Quotas Break Down Negative Stereotypes?

- How Do Gender Stereotypes Affect Today’s Society?

- Are Sexist Attitudes and Gender Stereotypes Linked?

- How Does Ridley Scott Create and Destroy Gender Stereotypes in Thelma and Louise?

- Does Mainstream Media Have a Duty to Challenge Gender Stereotypes?

- How Does the Proliferation of Gender Stereotypes Affect Modern Society?

- Why Do Children Learn Gender Stereotypes?

- How Do Gender Roles and Stereotypes Affect Children?

- Do Men and Women Differ in Their Gender Stereotypes?

- How Are Gender Stereotypes Depicted in “A Farewell to Arms” by Hemingway?

- What Are the Problems of Gender Stereotyping?

- How Have Gender Stereotypes Always Been a Part of Society?

- What Are the Factors That Determine Gender Stereotypes?

- How Do Gender Stereotypes Warp Our View of Depression?

- What Influences Gender Roles in Today’s Society?

- How Do Jane Eyre and the Works of Robert Browning Subvert Gender Stereotypes?

- What Is the Difference Between Gender Roles and Gender Stereotypes?

- How Do Magazines Create Gender Stereotypes?

- Where Did Gender Stereotypes Originate?

- How Does the Society Shape and Stereotypes Gender Roles?

- Why Do Gender Roles Change Over Time?

- How Do Gender Stereotypes Affect Students?

- What Is the Role of Family in Gender Stereotyping?

- How Can Gender Stereotypes Be Overcome?

- Can Stereotypes Be Changed?

- How Does Culture Influence Gender Stereotypes?

- How Can We Prevent Gender Stereotypes in Schools?

- Sociological Perspectives Titles

- Gender Roles Paper Topics

- Ethics Ideas

- Human Behavior Research Topics

- Motherhood Ideas

- Relationship Research Ideas

- Oppression Research Topics

- Parenting Research Topics

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 26). 124 Gender Stereotypes Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/gender-stereotypes-essay-examples/

"124 Gender Stereotypes Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 26 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/gender-stereotypes-essay-examples/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '124 Gender Stereotypes Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 26 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "124 Gender Stereotypes Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/gender-stereotypes-essay-examples/.

1. IvyPanda . "124 Gender Stereotypes Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/gender-stereotypes-essay-examples/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "124 Gender Stereotypes Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/gender-stereotypes-essay-examples/.

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

125 Gender Stereotypes Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Gender stereotypes are pervasive in society, shaping our beliefs and perceptions about what it means to be a man or a woman. These stereotypes can have harmful effects on individuals, reinforcing harmful gender norms and limiting opportunities for personal growth and self-expression. In order to challenge these stereotypes and promote gender equality, it is important to critically examine and deconstruct them.

To help spark discussion and reflection on the topic of gender stereotypes, here are 125 essay topic ideas and examples to consider:

- The impact of traditional gender roles on individuals' sense of self-worth

- How media representations of gender contribute to stereotypes

- The role of education in perpetuating or challenging gender stereotypes

- Gender stereotypes in the workplace and their effects on career advancement

- The intersection of race and gender stereotypes

- How gender stereotypes affect mental health and well-being

- Stereotypes about masculinity and femininity in different cultures

- The impact of gender stereotypes on children's development

- Gender stereotypes in sports and athletics

- The portrayal of gender in literature and popular culture

- Stereotypes about LGBTQ+ individuals and non-binary genders

- The link between gender stereotypes and violence against women

- How stereotypes about beauty and appearance affect individuals' self-esteem

- Gender stereotypes in parenting and caregiving roles

- The representation of gender in advertising and marketing

- Stereotypes about intelligence and abilities based on gender

- The connection between gender stereotypes and sexual harassment

- How gender stereotypes shape relationships and dating norms

- Gender stereotypes in STEM fields and other male-dominated industries

- The impact of social media on perpetuating gender stereotypes

- Stereotypes about emotional expression and vulnerability based on gender

- The role of religion in shaping gender norms and expectations

- Gender stereotypes in political leadership and representation

- How stereotypes about masculinity harm men's mental health

- The impact of gender stereotypes on body image and eating disorders

- Stereotypes about parenting and work-life balance based on gender

- Gender stereotypes in healthcare and medical treatment

- The representation of gender in video games and other forms of media

- Stereotypes about aging and gender

- The impact of gender stereotypes on individuals' career choices and aspirations

- Gender stereotypes in the criminal justice system

- Stereotypes about sexual orientation and gender identity

- How gender stereotypes affect individuals' access to healthcare and social services

- The portrayal of gender in children's toys and media

- Stereotypes about leadership and assertiveness based on gender

- The impact of gender stereotypes on individuals' relationships with their bodies

- Gender stereotypes in the fashion and beauty industries

- Stereotypes about intelligence and academic abilities based on gender

- The representation of gender in art and literature

- How gender stereotypes affect individuals' experiences of discrimination and prejudice

- Stereotypes about physical strength and athleticism based on gender

- The impact of gender stereotypes on individuals' experiences of bullying and harassment

- Gender stereotypes in the music and entertainment industries

- Stereotypes about domestic violence and abuse based on gender

- The portrayal of gender in historical and contemporary narratives

- How gender stereotypes affect individuals' experiences of trauma and recovery

- Gender stereotypes in the legal system and criminal justice

- Stereotypes about caregiving and emotional labor based on gender

- The impact of gender stereotypes on individuals' access to education and resources

- Gender stereotypes in the healthcare and medical fields

- The representation of gender in politics and government

- Stereotypes about physical appearance and attractiveness based on gender

- Gender stereotypes in the workplace and professional settings

- The impact of gender stereotypes on individuals' access to healthcare and social services

- How gender stereotypes affect individuals' relationships with their bodies

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

70 Argumentative Essay Topics About Gender Equality

Gender equality is an extremely debatable topic. Sooner or later, every group of friends, colleagues, or classmates will touch on this subject. Discussions never stop, and this topic is always relevant.

This is not surprising, as our society hasn’t reached 100% equality yet. Pay gaps, victimization, abortion laws, and other aspects remain painful for millions of women. You should always be ready to structure your thoughts and defend your point of view on this subject. Why not practice with our list of essay topics about gender equality?

Our cheap essay writing service authors prepared 70 original ideas for you. Besides, at the end of our article, you’ll find a list of inspirational sources for your essay.

Argumentative Essay Topics About Gender Equality

- Does society or a person define gender?

- Can culturally sanctioned gender roles hurt adolescents’ mental health?

- Who or what defines the concepts of “masculinity” and “femininity” in modern society?

- Should the rules of etiquette be changed because they’ve been created in the epoch of total patriarchy?

- Why is gender equality higher in developed countries? Is equality the cause or the result of the development?

- Are gender stereotypes based on the difference between men’s and women’s brains justified?

- Would humanity be more developed today if gender stereotypes never exited?

- Can a woman be a good politician? Why or why not?

- What are the main arguments of antifeminists? Are they justified?

- Would our society be better if more women were in power?

Analytical Gender Equality Topics

- How do gender stereotypes in the sports industry influence the careers of athletes?

- Social and psychological foundations of feminism in modern Iranian society: Describe women’s rights movements in Iran and changes in women’s rights.

- Describe the place of women in today’s sports and how this situation looked a hundred years ago.

- What changes have American women made in the social and economic sphere? Describe the creation of a legislative framework for women’s empowerment.

- How can young people fix gender equality issues?

- Why do marketing specialists keep taking advantage of gender stereotypes in advertising?

- How does gender inequality hinder our society from progress?

- What social problems does gender inequality cause?

- How does gender inequality influence the self-image of male adolescents?

- Why is the concept of feminism frequently interpreted negatively?

Argumentative Essay Topics About Gender Equality in Art and Literature

- Theory of gender in literature: do male and female authors see the world differently? Pick one book and analyze it in the context of gender.

- Compare and contrast how gender inequality is described in L. Tolstoy’s novel “Anna Karenina” and G. Flaubert’s novel “Madame Bovary.” Read and analyze the mentioned books, distinguish how gender inequality is described, and how the main characters manage this inequality.

- The artificial gender equality and class inequality in the novel “Brave New World” by Aldous Huxley.

- Do modern romance novels for teenagers help to break gender stereotypes, or do they enforce them?

- Gender equality changes through Disney animation films. Analyze the scenarios of Disney animation films from the very beginning. Describe how the overall mood in relation to female characters and their roles has changed.

- Henrik Ibsen touched on the topic of gender inequality in his play “A Doll’s House.” Why was it shocking for a 19th century audience?

- Concepts of gender inequality through examples of fairy tales. Analyze several fairy tales that contain female characters. What image do they have? Do these fairy tales misrepresent the nature of women? How do fairy tales spoil the world view of young girls?

- Why do female heroes rarely appear in superhero movies?

- Heroines of the movie “Hidden Figures” face both gender and racial inequalities. In your opinion, has the American society solved these issues entirely?

- The problem of gender inequality in the novel “The Color Purple” by Alice Walker.

Gender Equality Essay Ideas: Workplace and Employment

- Dress code in the workplace: Does it help to solve the problem of gender inequality, or is it a detriment?

- What kind of jobs are traditionally associated with men and women? How have these associations changed in the last 50 years?

- The pay gap between men and women: is it real?

- How can HR managers overcome gender stereotypes while hiring a new specialist?

- Analyze the concepts of “glass ceiling” and “glass elevator.” Do these phenomena still exist in our society?

Essay Topics About Gender Equality: Religion

- Gender aspects of Christian virtue and purity in the Bible.

- What does the equality of men and women look like from the perspective of Christianity? Can a woman be a pastor?

- Orthodox Judaism: Women and the transformation of their roles in a religious institute. Describe the change in women’s roles in modern Judaism.

- How can secularism help solve the problem of gender inequality in religious societies?

- Is the problem of gender inequality more serious in religious societies?

Compare and Contrast Essay Topics About Gender Equality

- Compare and contrast the problems men and women experience in managerial positions.

- Compare and contrast what progress has been made on gender equality in the USA and Sweden.

- Compare and contrast the social status of women in ancient Athens and Sparta.

- Conduct a sociological analysis of gender asymmetry in various languages. Compare and contrast the ways of assigning gender in two different languages.

- Compare and contrast the portrayal of female characters in 1960s Hollywood films and in modern cinematography (pick two movies). What has changed?

Gender Equality Topics: Definitions

- Define the term “misandry.” What is the difference between feminism and misandry?

- Define the term “feminology.” How do feminologists help to break down prejudice about the gender role of women?

- Define the term “catcalling.” How is catcalling related to the issue of gender inequality?

- Define the term “femvertising.” How does this advertising phenomenon contribute to the resolution of the gender inequality issue?

- Define the term “misogyny.” What is the difference between “misogyny” and “sexism”?

Gender Equality Essay Ideas: History

- The roles of the mother and father through history.

- Define the most influential event in the history of the feminist movement.

- What ancient societies preached matriarchy?

- How did World War II change the attitude toward women in society?

- Woman and society in the philosophy of feminism of the second wave. Think on works of Simone de Beauvoir and Betty Friedan and define what ideas provoked the second wave.

Essay Topics About Gender Equality in Education

- How do gender stereotypes influence the choice of major among high school students?

- Discuss the problems of female education in the interpretation of Mary Wollstonecraft. Reflect on the thoughts of Mary Wollstonecraft on gender equality and why women should be treated equally to men.

- Self-determination of women in professions: Modern contradictions. Describe the character of a woman’s self-determination as a professional in today’s society.

- Should gender and racial equality be taught in elementary school?

- Will sex education at schools contribute to the development of gender equality?

Gender Equality Topics: Sex and Childbirth

- Sexual violence in conflict situations: The problem of victimization of women.

- The portrayal of menstruation and childbirth in media: Now versus twenty years ago.

- How will the resolution of the gender inequality issue decrease the rate of sexual abuse toward women?

- The attitude toward menstruation in different societies and how it influences the issue of gender equality.

- How does the advertising of sexual character aggravate the problem of gender inequality?

- Should advertising that uses sexual allusion be regulated by the government?

- How has the appearance of various affordable birth control methods contributed to the establishment of gender equality in modern society?

- Do men have the right to give up their parental duties if women refuse to have an abortion?

- Can the child be raised without the influence of gender stereotypes in modern society?

- Did the sexual revolution in the 1960s help the feminist movement?

How do you like our gender equality topics? We’ve tried to make them special for you. When you pick one of these topics, you should start your research. We recommend you to check the books we’ve listed below.

Non-Fiction Books and Articles on Gender Equality Topics

- Beecher, C. “The Peculiar Responsibilities of American Women.”

- Connell, R. (2011). “Confronting Equality: Gender, Knowledge and Global Change.”

- Doris H. Gray. (2013). “Beyond Feminism and Islamism: Gender and Equality in North Africa.”

- Inglehart Ronald, Norris Pippa. (2003). “Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change Around the World.”

- Mary Ann Danowitz Sagaria. (2007). “Women, Universities, and Change: Gender Equality in the European Union and the United States (Issues in Higher Education).”

- Merrill, R. (1997). “Good News for Women: A Biblical Picture of Gender Equality.”

- Mir-Hosseini, Z. (2013). “Gender and Equality in Muslim Family Law: Justice and Ethics in the Islamic Legal Process.”

- Raymond F. Gregory. (2003). “Women and Workplace Discrimination: Overcoming Barriers to Gender Equality.”

- Rubery, J., & Koukiadaki, A. (2016). “Closing the Gender Pay Gap: A Review of the Issues, Policy Mechanisms and International Evidence.”

- Sharma, A. (2016). “Managing Diversity and Equality in the Workplace.”

- Sika, N. (2011). “The Millennium Development Goals: Prospects for Gender Equality in the Arab World.”

- Stamarski, C. S., & Son Hing, L. S. (2015). “Gender Inequalities in the Workplace: The Effects of Organizational Structures, Processes, Practices, and Decision Makers’ Sexism.”

- Verniers, C., & Vala, J. (2018). “Justifying Gender Discrimination in the Workplace: The Mediating Role of Motherhood Myths.”

- Williams, C. L., & Dellinger, K. (2010). “Gender and Sexuality in the Workplace.”

Literary Works for Your Gender Equality Essay Ideas

- “A Doll’s House” by Henrik Ibsen

- “A Room of One’s Own” by Virginia Woolf

- “Anna Karenina” by Leo Tolstoy

- “Brave New World” by Aldous Huxley

- “ The Awakening” by Kate Chopin

- “The Color Purple” by Alice Walker

- “The Handmaid’s Tale” by Margaret Atwood

- “The Help” by Kathryn Stockett

- “The Scarlet Letter” by Nathaniel Hawthorne

- “The Second Sex” by Simone de Beauvoir

We’re sure that with all of these argumentative essay topics about gender equality and useful sources, you’ll get a good grade without much effort! If you have any difficulties with your homework, request “ write my essay for cheap ” help and our expert writers are always ready to help you.

Our cheap essay writing service has one of the lowest pricing policies on the market. Fill in the ordering form, and we guarantee that you’ll get a cheap, plagiarism-free sample as soon as possible!

~ out of 10 - average quality score

~ writers active

- Dissertation

- PowerPoint Presentation

- Book Report/Review

- Research Proposal

- Math Problems

- Proofreading

- Movie Review

- Cover Letter Writing

- Personal Statement

- Nursing Paper

- Argumentative Essay

- Research Paper

- Discussion Board Post

TOP 100 Gender Equality Essay Topics

Table of Contents

Need ideas for argumentative essay on gender inequality? We’ve got a bunch!

… But let’s start off with a brief intro.

What is gender equality?

Equality between the sexes is a huge part of basic human rights. It means that men and women have the same opportunities to fulfil their potential in all spheres of life.

Today, we still face inequality issues as there is a persistent gap in access to opportunities for men and women.

Women have less access to decision-making and higher education. They constantly face obstacles at the workplace and have greater safety risks. Maintaining equal rights for both sexes is critical for meeting a wide range of goals in global development.

Inequality between the sexes is an interesting area to study so high school, college, and university students are often assigned to write essays on gender topics.

In this article, we are going to discuss the key peculiarities of gender equality essay. Besides, we have created a list of the best essay topic ideas.

What is the specifics of gender equality essay?

Equality and inequality between the sexes are important historical and current social issues which impact the way students and their families live. They are common topics for college papers in psychology, sociology, gender studies.

When writing an essay on equality between the sexes, you need to argue for a strong point of view and support your argument with relevant evidence gathered from multiple sources.

But first, you’d need to choose a good topic which is neither too broad nor too narrow to research.

Research is crucial for the success of your essay because you should develop a strong argument based on an in-depth study of various scholarly sources.

Equality between sexes is a complex problem. You have to consider different aspects and controversial points of view on specific issues, show your ability to think critically, develop a strong thesis statement, and build a logical argument, which can make a great impression on your audience.

If you are looking for interesting gender equality essay topics, here you will find a great list of 100 topic ideas for writing essays and research papers on gender issues in contemporary society.

Should you find that some topics are too broad, feel free to narrow them down.

Powerful gender equality essay topics

Here are the top 25 hottest topics for your argumentative opinion paper on gender issues.

Whether you are searching for original creative ideas for gender equality in sports essay or need inspiration for gender equality in education essay, we’ve got you covered.

Use imagination and creativity to demonstrate your approach.

- Analyze gender-based violence in different countries

- Compare wage gap between the sexes in different countries

- Explain the purpose of gender mainstreaming

- Implications of sex differences in the human brain

- How can we teach boys and girls that they have equal rights?

- Discuss gender-neutral management practices

- Promotion of equal opportunities for men and women in sports

- What does it mean to be transgender?

- Discuss the empowerment of women

- Why is gender-blindness a problem for women?

- Why are girls at greater risk of sexual violence and exploitation?

- Women as victims of human trafficking

- Analyze the glass ceiling in management

- Impact of ideology in determining relations between sexes

- Obstacles that prevent girls from getting quality education in African countries

- Why are so few women in STEM?

- Major challenges women face at the workplace

- How do women in sport fight for equality?

- Women, sports, and media institutions

- Contribution of women in the development of the world economy

- Role of gender diversity in innovation and scientific discovery

- What can be done to make cities safer for women and girls?

- International trends in women’s empowerment

- Role of schools in teaching children behaviours considered appropriate for their sex

- Feminism on social relations uniting women and men as groups

Gender roles essay topics

We can measure the equality of men and women by looking at how both sexes are represented in a range of different roles. You don’t have to do extensive and tiresome research to come up with gender roles essay topics, as we have already done it for you.

Have a look at this short list of top-notch topic ideas .

- Are paternity and maternity leaves equally important for babies?

- Imagine women-dominated society and describe it

- Sex roles in contemporary western societies

- Compare theories of gender development

- Adoption of sex-role stereotyped behaviours

- What steps should be taken to achieve gender-parity in parenting?

- What is gender identity?

- Emotional differences between men and women

- Issues modern feminism faces

- Sexual orientation and gender identity

- Benefits of investing in girls’ education

- Patriarchal attitudes and stereotypes in family relationships

- Toys and games of girls and boys

- Roles of men and women in politics

- Compare career opportunities for both sexes in the military

- Women in the US military

- Academic careers and sex equity

- Should men play larger roles in childcare?

- Impact of an ageing population on women’s economic welfare

- Historical determinants of contemporary differences in sex roles

- Gender-related issues in gaming

- Culture and sex-role stereotypes in advertisements

- What are feminine traits?

- Sex role theory in sociology

- Causes of sex differences and similarities in behaviour

Gender inequality research paper topics

Examples of inequality can be found in the everyday life of different women in many countries across the globe. Our gender inequality research paper topics are devoted to different issues that display discrimination of women throughout the world.

Choose any topic you like, research it, brainstorm ideas, and create a detailed gender inequality essay outline before you start working on your first draft.

Start off with making a debatable thesis, then write an engaging introduction, convincing main body, and strong conclusion for gender inequality essay .

- Aspects of sex discrimination

- Main indications of inequality between the sexes

- Causes of sex discrimination

- Inferior role of women in the relationships

- Sex differences in education

- Can education solve issues of inequality between the sexes?

- Impact of discrimination on early childhood development

- Why do women have limited professional opportunities in sports?

- Gender discrimination in sports

- Lack of women having leadership roles

- Inequality between the sexes in work-family balance

- Top factors that impact inequality at a workplace

- What can governments do to close the gender gap at work?

- Sex discrimination in human resource processes and practices

- Gender inequality in work organizations

- Factors causing inequality between men and women in developing countries

- Work-home conflict as a symptom of inequality between men and women

- Why are mothers less wealthy than women without children?

- Forms of sex discrimination in a contemporary society

- Sex discrimination in the classroom

- Justification of inequality in American history

- Origins of sex discrimination

- Motherhood and segregation in labour markets

- Sex discrimination in marriage

- Can technology reduce sex discrimination?

Most controversial gender topics

Need a good controversial topic for gender stereotypes essay? Here are some popular debatable topics concerning various gender problems people face nowadays.

They are discussed in scientific studies, newspaper articles, and social media posts. If you choose any of them, you will need to perform in-depth research to prepare an impressive piece of writing.

- How do gender misconceptions impact behaviour?

- Most common outdated sex-role stereotypes

- How does gay marriage influence straight marriage?

- Explain the role of sexuality in sex-role stereotyping

- Role of media in breaking sex-role stereotypes

- Discuss the dual approach to equality between men and women

- Are women better than men or are they equal?

- Sex-role stereotypes at a workplace

- Racial variations in gender-related attitudes

- Role of feminism in creating the alternative culture for women

- Feminism and transgender theory

- Gender stereotypes in science and education

- Are sex roles important for society?

- Future of gender norms

- How can we make a better world for women?

- Are men the weaker sex?

- Beauty pageants and women’s empowerment

- Are women better communicators?

- What are the origins of sexual orientation?

- Should prostitution be legal?

- Pros and cons of being a feminist

- Advantages and disadvantages of being a woman

- Can movies defy gender stereotypes?

- Sexuality and politics

Feel free to use these powerful topic ideas for writing a good college-level gender equality essay or as a starting point for your study.

No time to do decent research and write your top-notch paper? No big deal! Choose any topic from our list and let a pro write the essay for you!

How to Write Winning Essays on Honor

Simple Tips On Writing The George Washington Essay

Pro tips on how to write money cant buy happiness essay.

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Gender Stereotypes — Gender Stereotypes Of Women

Gender Stereotypes of Women

- Categories: Discrimination Gender Stereotypes

About this sample

Words: 476 |

Published: Mar 14, 2024

Words: 476 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 978 words

2 pages / 911 words

2 pages / 799 words

5 pages / 2303 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Gender Stereotypes

Kimmel, Michael S. (2000). The Gendered Society. Oxford University Press.Ward, L. M., & Friedman, K. (2006). Using TV as a guide: Associations between television viewing and adolescents' sexual attitudes and behavior. Journal of [...]

Hip hop music has undeniably become a dominant force in the music industry, shaping cultural trends and influencing the lives of millions worldwide. While many praise the genre for its creativity, authenticity, and ability to [...]

Imagine walking into a fast-food restaurant and being greeted by a commercial on a television screen. The camera zooms in on a juicy burger, as an attractive woman takes a seductive bite. The message is clear: eating at this [...]

Zootopia, a widely popular animated film released by Disney in 2016, is not only a fun and entertaining movie for children, but also a thought-provoking film that addresses important social issues. One of the key themes explored [...]

How can a simple color such as pink or blue change people’s perspectives on your sexuality? This is a common example of a gender stereotype that is showed by many people from adolescents to adults. This is an unfair issue in [...]

‘Feuding families leads to senseless violence and the tragic death of six young people’, this could easily be the headline for a story in today’s newspaper but it is the plot for a play written over four hundred years ago. Romeo [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Stereotypes and Gender Roles

Many of our gender stereotypes are strong because we emphasize gender so much in culture (Bigler & Liben, 2007). For example, children learn at a young age that there are distinct expectations for boys and girls. Gender roles refer to the role or behaviors learned by a person as appropriate to their gender and are determined by the dominant cultural norms. Cross-cultural studies reveal that children are aware of gender roles by age two or three and can label others’ gender and sort objects into gender categories. At four or five, most children are firmly entrenched in culturally appropriate gender roles (Kane, 1996). When children do not conform to the appropriate gender role for their culture, they may face negative sanctions such as being criticized, bullied, marginalized or rejected by their peers. A girl who wishes to take karate class instead of dance lessons may be called a “tomboy” and face difficulty gaining acceptance from both male and female peer groups (Ready, 2001). Boys, especially, are subject to intense ridicule for gender nonconformity (Coltrane and Adams, 2008; Kimmel, 2000)

By the time we are adults, our gender roles are a stable part of our personalities, and we usually hold many gender stereotypes. Men tend to outnumber women in professions such as law enforcement, the military, and politics. Women tend to outnumber men in care-related occupations such as child care, health care, and social work. These occupational roles are examples of typical Western male and female behavior, derived from our culture’s traditions. Adherence to these occupational gender roles demonstrates fulfillment of social expectations but may not necessarily reflect personal preference (Diamond, 2002).

Gender stereotypes are not unique to American culture. Williams and Best (1982) conducted several cross-cultural explorations of gender stereotypes using data collected from 30 cultures. There was a high degree of agreement on stereotypes across all cultures which led the researchers to conclude that gender stereotypes may be universal. Additional research found that males tend to be associated with stronger and more active characteristics than females (Best, 2001); however recent research argues that culture shapes how some gender stereotypes are perceived. Researchers found that across cultures, individualistic traits were viewed as more masculine; however, collectivist cultures rated masculine traits as collectivist and not individualist (Cuddy et al., 2015). These findings provide support that gender stereotypes may be moderated by cultural values.

There are two major psychological theories that partially explain how children form their own gender roles after they learn to differentiate based on gender. Gender schema theory argues that children are active learners who essentially socialize themselves and actively organize others’ behavior, activities, and attributes into gender categories, which are known as schemas . These schemas then affect what children notice and remember later. People of all ages are more likely to remember schema-consistent behaviors and attributes than schema-inconsistent behaviors and attributes. So, people are more likely to remember men, and forget women, who are firefighters. They also misremember schema-inconsistent information. If research participants are shown pictures of someone standing at the stove, they are more likely to remember the person to be cooking if depicted as a woman, and the person to be repairing the stove if depicted as a man. By only remembering schema-consistent information, gender schemas strengthen more and more over time.

A second theory that attempts to explain the formation of gender roles in children is social learning theory which argues that gender roles are learned through reinforcement, punishment, and modeling. Children are rewarded and reinforced for behaving in concordance with gender roles and punished for breaking gender roles. In addition, social learning theory argues that children learn many of their gender roles by modeling the behavior of adults and older children and, in doing so, develop ideas about what behaviors are appropriate for each gender. Social learning theory has less support than gender schema theory but research shows that parents do reinforce gender-appropriate play and often reinforce cultural gender norms.

Gender Roles and Culture

Hofstede’s (2001) research revealed that on the Masculinity and Femininity dimension (MAS), cultures with high masculinity reported distinct gender roles, moralistic views of sexuality and encouraged passive roles for women. Additionally, these cultures discourage premarital sex for women but have no such restrictions for men. The cultures with the highest masculinity scores were: Japan, Italy, Austria and Venezuela. Cultures low in masculinity (high femininity) had gender roles that were more likely to overlap and encouraged more active roles for women. Sex before marriage was seen as acceptable for both women and men in these cultures. Four countries scoring lowest in masculinity were Norway, Denmark, Netherlands and Sweden. The United States is slightly more masculine than feminine on this dimension; however, these aspects of high masculinity are balanced by a need for individuality.

Culture and Psychology Copyright © 2020 by L D Worthy; T Lavigne; and F Romero is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Essay on Gender Stereotypes

Students are often asked to write an essay on Gender Stereotypes in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Gender Stereotypes

Introduction.

Gender stereotypes are general beliefs about behaviors, characteristics, and roles of men and women in society. They can limit individuals’ potential and opportunities.

Common Stereotypes

Men are often seen as strong and decisive, while women are considered nurturing and emotional. These stereotypes can limit personal growth and career choices.

Consequences

Stereotypes can lead to discrimination and unequal treatment. They can also affect self-esteem and mental health.

Breaking Stereotypes

Education and awareness are key to breaking gender stereotypes. Encouraging individuality and respect for everyone’s abilities can help create a more equal society.

250 Words Essay on Gender Stereotypes

Gender stereotypes are preconceived notions about the roles and behaviors appropriate for men and women. They are deeply ingrained in society and influence our behavior, expectations, and perceptions.

The Origin of Gender Stereotypes

The roots of gender stereotypes can be traced back to traditional societal structures. Historically, men were hunters and protectors, while women were gatherers and caregivers. These roles have been passed down generations, evolving into modern stereotypes.

Implications of Gender Stereotypes

These stereotypes limit individual growth and societal progress. They force individuals into predefined boxes, stifling their true potential. For instance, the stereotype that women are not good at math discourages them from pursuing STEM fields, while the belief that men should not show emotions hinders their mental health.

Breaking Down Stereotypes

It’s crucial to challenge these stereotypes to achieve gender equality. This can be done through education, promoting representation, and encouraging open dialogue. It’s also essential to challenge our own biases and question the stereotypes we unconsciously uphold.

Gender stereotypes are not only unfair but also counterproductive. They limit individuals and society as a whole. By actively challenging these stereotypes, we can work towards a more equitable and inclusive society.

500 Words Essay on Gender Stereotypes

Gender stereotypes are preconceived notions about the roles, characteristics, and behaviors of men and women. These stereotypes are deeply ingrained in our society and have significant implications on individual and societal levels. They are often perpetuated by media, educational systems, and social interactions, and can limit the potential and freedom of individuals, as well as perpetuate inequality and discrimination.

The origins of gender stereotypes can be traced back to traditional societal structures. Historically, men were seen as the providers, hunters, and protectors, while women were perceived as caregivers and homemakers. These roles were often dictated by physical attributes and the need for survival. However, as societies evolved, these roles became less relevant but remained ingrained in societal consciousness, leading to the perpetuation of gender stereotypes.

Gender stereotypes have far-reaching implications. They can limit opportunities and possibilities for individuals, leading to unequal outcomes in education, employment, and leadership roles. For instance, women are often stereotyped as being less capable in STEM fields, which can discourage them from pursuing careers in these areas. Similarly, men may face societal pressure to avoid careers perceived as feminine, such as nursing or teaching.

Furthermore, gender stereotypes can perpetuate harmful norms and behaviors. For example, the stereotype that men should be emotionally strong can deter them from seeking help for mental health issues, leading to adverse health outcomes. On the other hand, women are often objectified and sexualized due to prevalent stereotypes, contributing to issues such as body shaming and sexual harassment.

Challenging Gender Stereotypes

Challenging gender stereotypes requires collective efforts at various levels. Education plays a crucial role in breaking down these stereotypes. Schools and universities should promote a curriculum that encourages critical thinking about gender roles and stereotypes.

Media also plays a significant role in shaping societal perceptions. Hence, it is essential for media outlets to portray diverse and non-stereotypical images of men and women. This includes showcasing women in leadership roles and men in caregiving roles.

Moreover, individuals can challenge gender stereotypes in their everyday lives. This can be achieved by questioning traditional gender roles, promoting gender equality in personal and professional spaces, and encouraging open conversations about gender stereotypes.

In conclusion, gender stereotypes are deeply entrenched in our society and have significant implications. While they are rooted in historical societal structures, they are perpetuated by modern institutions and interactions. Therefore, challenging these stereotypes requires concerted efforts at individual, societal, and institutional levels. By promoting gender equality and challenging traditional notions of gender roles, we can create a more inclusive and equitable society.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Gender Equality in India

- Essay on Gender Equality

- Essay on Life Below Water

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Improve your English. Speak with confidence!

- Free Mini Course

- Posted in in ESL Conversation Questions

40 discussion questions about gender and gender roles

- Posted by by Learn English Every Day

- January 30, 2023

- Updated April 17, 2023

Practice your English speaking skills and engage in lively conversations with these discussion questions about gender and gender roles .

When actress Emma Watson addressed the UN , she famously said “It is time that we all see gender as a spectrum instead of two sets of opposing ideas.” It will be fascinating to see how you and your speaking partners feel about this important topic.

40 discussion questions about gender

- What are some differences between men and women?

- What are some similarities between men and women?

- Do you identify as one gender?

- What are your pronouns?

- Do you believe that gender is a construct? Why or why not?

- What are some gender stereotypes that men deal with?

- What are some gender stereotypes that women deal with?

- Do you think that single-sex or co-ed schools are better for students?

- What obligations does a father have to his family, if any?

- What obligations does a mother have to her family, if any?

- Can a mother fulfill a father’s obligations?

- Can father fulfill a mother’s obligations?

- Were gender roles traditional in your childhood home?

- Are women better than men at certain things?

- Are men better than women at certain things?

- Would you prefer to have a female boss, or a male boss? Why?

- Do you prefer to have female or male colleagues? Why?

- List as many male-dominated industries as you can.

- List as many female-dominated industries as you can.

- Do you agree with women fighting in the military? Why or why not?

- Do you think that women should be able to

- Do you relate to male or female friends more easily? Why?

- Are all genders treated equally or differently in your country?

- Do you think men or women make better leaders?

- Does a leader’s gender make a difference?

- Has your country ever had a female leader?

- Does your country have a “macho” culture?

- Does your country have different laws based on gender?

- Is it legal for people to change their gender in your country?

- Do you think gender roles are changing in your country?

- Is it okay for clubs and societies to exclude people based on their gender?

- What barriers do men and women face in the workplace?

- What challenges do men and women face in society?

- What challenges do non-binary persons face in society?

- What challenges do transgender persons face in society?

- Should parents raise children differently, based on each child’s gender?

- Do you think society treats boys and girls differently?

- Is it okay for a girl to be a tomboy ?

- Is it okay for a boy to play with dolls?

- How are you expected to behave because of your gender?

- Have you ever seen or experienced sexism? What happened?

- Have you ever seen or experienced chauvinism? What happened?

- Why does humanity typically depict gods and deities as men?

What other ESL conversation questions and ESL discussion topics would you like us to write about next?

Post your suggestions in the comments below!

Get free English lessons via email

Subscribe to my newsletter and get English lessons & helpful resources once a week!

Unsubscribe anytime. For more details, review our Privacy Policy .

I agree to receive updates & promotions.

You have successfully joined our subscriber list.

Learn English Every Day

Follow us on YouTube for fun English lessons and helpful learning resources!

Post navigation

- Posted in in Quizzes

5 fun quizzes to test your English vocabulary

40 conversation questions about colors

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The multiple dimensions of gender stereotypes: a current look at men’s and women’s characterizations of others and themselves.

- 1 TUM School of Management, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany

- 2 Amsterdam Business School, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 3 Department of Psychology, New York University, New York, NY, United States

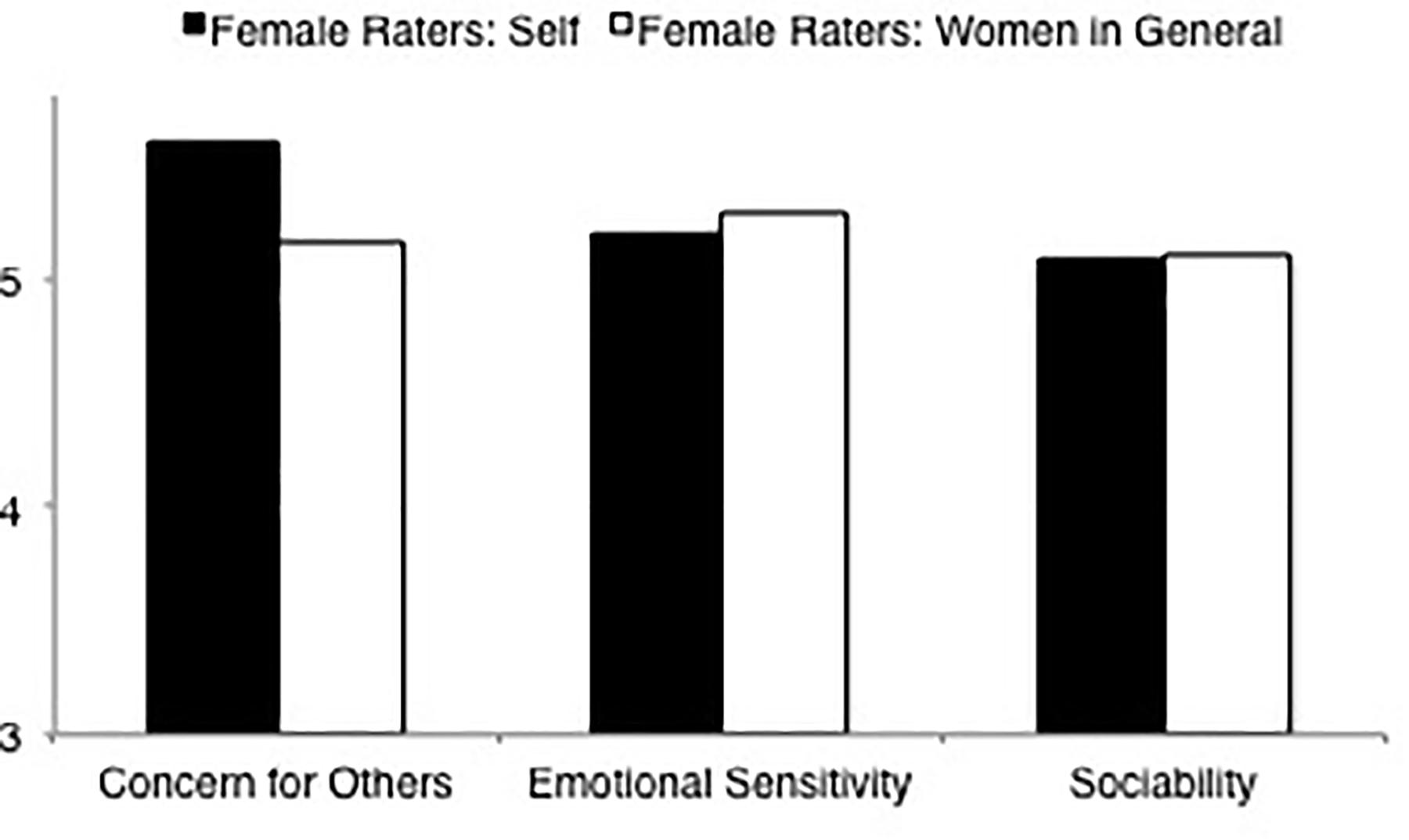

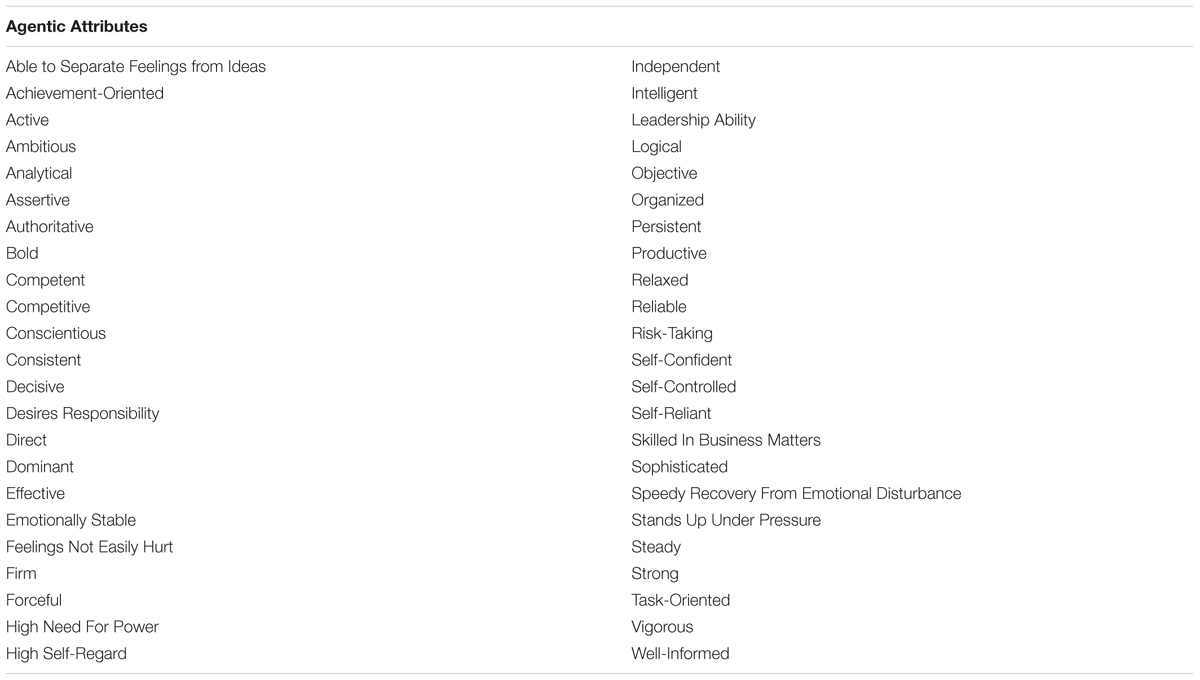

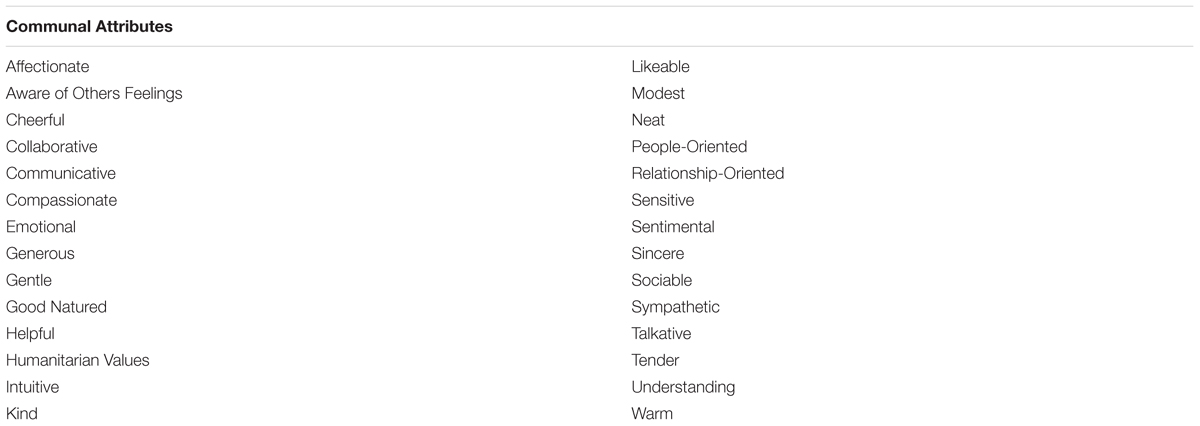

We used a multi-dimensional framework to assess current stereotypes of men and women. Specifically, we sought to determine (1) how men and women are characterized by male and female raters, (2) how men and women characterize themselves, and (3) the degree of convergence between self-characterizations and charcterizations of one’s gender group. In an experimental study, 628 U.S. male and female raters described men, women, or themselves on scales representing multiple dimensions of the two defining features of gender stereotypes, agency and communality: assertiveness, independence, instrumental competence, leadership competence (agency dimensions), and concern for others, sociability and emotional sensitivity (communality dimensions). Results indicated that stereotypes about communality persist and were equally prevalent for male and female raters, but agency characterizations were more complex. Male raters generally descibed women as being less agentic than men and as less agentic than female raters described them. However, female raters differentiated among agency dimensions and described women as less assertive than men but as equally independent and leadership competent. Both male and female raters rated men and women equally high on instrumental competence. Gender stereotypes were also evident in self-characterizations, with female raters rating themselves as less agentic than male raters and male raters rating themselves as less communal than female raters, although there were exceptions (no differences in instrumental competence, independence, and sociability self-ratings for men and women). Comparisons of self-ratings and ratings of men and women in general indicated that women tended to characterize themselves in more stereotypic terms – as less assertive and less competent in leadership – than they characterized others in their gender group. Men, in contrast, characterized themselves in less stereotypic terms – as more communal. Overall, our results show that a focus on facets of agency and communality can provide deeper insights about stereotype content than a focus on overall agency and communality.

Introduction

There is no question that a great deal of progress has been made toward gender equality, and this progress is particularly evident in the workplace. There also is no question that the goal of full gender equality has not yet been achieved – not in pay ( AAUW, 2016 ) or position level ( Catalyst, 2016 ). In a recent interview study with female managers the majority of barriers for women’s advancement that were identified were consequences of gender stereotypes ( Peus et al., 2015 ). There is a long history of research in psychology that corroborates this finding (for reviews see Eagly and Sczesny, 2009 ; Heilman, 2012 ). These investigations support the idea that gender stereotypes can be impediments to women’s career advancement, promoting both gender bias in employment decisions and women’s self-limiting behavior ( Heilman, 1983 ).

This study is designed to investigate the current state of gender stereotypes about men and women using a multi-dimensional framework. Much of the original research on the content of gender stereotypes was conducted several decades ago (e.g., Rosenkrantz et al., 1968 ), and more recent research findings are inconsistent, some suggesting that there has been a change in traditional gender stereotypes (e.g., Duehr and Bono, 2006 ) and others suggesting there has not (e.g., Haines et al., 2016 ). Measures of stereotyping in these studies tend to differ, all operationalizing the constructs of agency and communality, the two defining features of gender stereotypes ( Abele et al., 2008 ), but in different ways. We propose that the conflict in findings may derive in part from the focus on different facets of these constructs in different studies. Thus, we seek to obtain a more complete picture of the specific content of today’s gender stereotypes by treating agency and communality, as multi-dimensioned constructs.

Gender stereotypes often are internalized by men and women, and we therefore focus both on how men and women are seen by others and how they see themselves with respect to stereotyped attributes. We also plan to compare and contrast charcterizations of men or women as a group with charcterizations of self, something not typically possible because these two types of characterizations are rarely measured in the same study. In sum, we have multiple objectives: We aim to develop a multi-dimensional framework for assessing current conceptions of men’s and women’s characteristics and then use it to consider how men and women are seen by male and female others, how men and women see themselves, and how these perceptions of self and others in their gender group coincide or differ. In doing so, we hope to demonstrate the benefits of viewing agency and communality as multidimensional constructs in the study of gender stereotypes.

Gender Stereotypes

Gender stereotypes are generalizations about what men and women are like, and there typically is a great deal of consensus about them. According to social role theory, gender stereotypes derive from the discrepant distribution of men and women into social roles both in the home and at work ( Eagly, 1987 , 1997 ; Koenig and Eagly, 2014 ). There has long been a gendered division of labor, and it has existed both in foraging societies and in more socioeconomically complex societies ( Wood and Eagly, 2012 ). In the domestic sphere women have performed the majority of routine domestic work and played the major caretaker role. In the workplace, women have tended to be employed in people-oriented, service occupations rather than things-oriented, competitive occupations, which have traditionally been occupied by men (e.g., Lippa et al., 2014 ). This contrasting distribution of men and women into social roles, and the inferences it prompts about what women and men are like, give rise to gender stereotypical conceptions ( Koenig and Eagly, 2014 ).

Accordingly, men are characterized as more agentic than women, taking charge and being in control, and women are characterized as more communal than men, being attuned to others and building relationships (e.g., Broverman et al., 1972 ; Eagly and Steffen, 1984 ). These two concepts were first introduced by Bakan (1966) as fundamental motivators of human behavior. During the last decades, agency (also referred to as “masculinity,” “instrumentality” or “competence”) and communality (also referred to as “communion,” “femininity,” “expressiveness,” or “warmth”) have consistently been the focus of research (e.g., Spence and Buckner, 2000 ; Fiske et al., 2007 ; Cuddy et al., 2008 ; Abele and Wojciszke, 2014 ). These dual tenets of social perception have been considered fundamental to gender stereotypes.

Stereotypes can serve an adaptive function allowing people to categorize and simplify what they observe and to make predictions about others (e.g., Devine and Sharp, 2009 ; Fiske and Taylor, 2013 ). However, stereotypes also can induce faulty assessments of people – i.e., assessments based on generalization from beliefs about a group that do not correspond to a person’s unique qualities. These faulty assessments can negatively or positively affect expectations about performance, and bias consequent decisions that impact opportunities and work outcomes for both men and women (e.g., Heilman, 2012 ; Heilman et al., 2015 ; Hentschel et al., 2018 ). Stereotypes about gender are especially influential because gender is an aspect of a person that is readily noticed and remembered ( Fiske et al., 1991 ). In other words, gender is a commonly occurring cue for stereotypic thinking ( Blair and Banaji, 1996 ).

Gender stereotypes are used not only to characterize others but also to characterize oneself ( Bem, 1974 ). The process of self-stereotyping can influence people’s identities in stereotype-congruent directions. Stereotyped characteristics can thereby be internalized and become part of a person’s gender identity – a critical aspect of the self-concept ( Ruble and Martin, 1998 ; Wood and Eagly, 2015 ). Young boys and girls learn about gender stereotypes from their immediate environment and the media, and they learn how to behave in gender-appropriate ways ( Deaux and LaFrance, 1998 ). These socialization experiences no doubt continue to exert influence later in life and, indeed, research has shown that men’s and women’s self-characterizations differ in ways that are stereotype-consistent ( Bem, 1974 ; Spence and Buckner, 2000 ).

Measurement of Gender Stereotypes

Gender stereotypes, and their defining features of agency and communality, have been measured in a variety of ways ( Kite et al., 2008 ). Researchers have investigated people’s stereotypical assumptions about how men and women differ in terms of, for example, ascribed traits (e.g., Williams and Best, 1990 ), role behaviors (e.g., Haines et al., 2016 ), occupations (e.g., Deaux and Lewis, 1984 ), or emotions (e.g., Plant et al., 2000 ). Researchers also have distinguished personality, physical, and cognitive components of gender stereotypes ( Diekman and Eagly, 2000 ). In addition, they have investigated how men’ and women’s self-characterizations differ in stereotype-consistent ways ( Spence and Buckner, 2000 ).

Today, the most common measures of gender stereotypes involve traits and attributes. Explicit measures of stereotyping entail responses to questionnaires asking for descriptions of men or women using Likert or bi-polar adjective scales (e.g., Kite et al., 2008 ; Haines et al., 2016 ), or asking for beliefs about the percentage of men and women possessing certain traits and attributes (e.g., McCauley and Stitt, 1978 ). Gender stereotypes have also been studied using implicit measures, using reaction time to measure associations between a gender group and a stereotyped trait or attribute (e.g., Greenwald and Banaji, 1995 ). Although implicit measures are used widely in some areas of research, our focus in the research reported here builds on the longstanding tradition of measuring gender stereotypes directly through the use of explicit measures.

Contemporary Gender Stereotypes

Researchers often argue that stereotypes are tenacious; they tend to have a self-perpetuating quality that is sustained by cognitive distortion ( Hilton and von Hippel, 1996 ; Heilman, 2012 ). However, stereotype maintenance is not only a product of the inflexibility of people’s beliefs but also a consequence of the societal roles women and men enact ( Eagly and Steffen, 1984 ; Koenig and Eagly, 2014 ). Therefore, the persistence of traditional gender stereotypes is fueled by skewed gender distribution into social roles. If there have been recent advances toward gender equality in workforce participation and the rigid representation of women and men in long-established gender roles has eased, then might the content of gender stereotypes have evolved to reflect this change?

The answer to this question is not straightforward; the degree to which there has been a true shift in social roles is unclear. On the one hand, there are more women in the workforce than ever before. In 1967, 36% of U.S. households with married couples were made up of a male provider working outside the home and a female caregiver working inside the home, but now only 19% of U.S. households concur with this division ( Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017 ). Moreover, women increasingly pursue traditionally male careers, and there are more women in roles of power and authority. For example, today women hold almost 40% of management positions in the United States ( Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017 ). In addition, more men are taking on a family’s main caretaker role ( Ladge et al., 2015 ). Though families with only the mother working are still rare (5% in 2016 compared to 2% in 1970), the average number of hours fathers spent on child care per week increased from 2.5 to 8 h in the last 40 years ( Pew Research Center, 2018 ). In addition, the majority of fathers perceive parenting as extremely important to their identity ( Pew Research Center, 2018 ).

On the other hand, role segregation, while somewhat abated, has by no means been eliminated. Despite their increased numbers in the labor force, women still are concentrated in occupations that are perceived to require communal, but not agentic attributes. For example, the three most common occupations for women in the U.S. involve care for others (elementary and middle school teacher, registered nurse, and secretary and administrative assistant; U.S. Department of Labor, 2015 ), while men more than women tend to work in occupations requiring agentic attributes (e.g., senior management positions, construction, or engineering; Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016b ). Sociological research shows that women are underrepresented in occupations that are highly competitive, inflexible, and require high levels of physical skill, while they are overrepresented in occupations that place emphasis on social contributions and require interpersonal skills ( Cortes and Pan, 2017 ). Moreover, though men’s home and family responsibilities have increased, women continue to perform a disproportionate amount of domestic work ( Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016a ), have greater childcare responsibilities ( Craig and Mullan, 2010 ; Kan et al., 2011 ), and continue to be expected to do so ( Park et al., 2008 ).

Thus, there is reason both to expect traditional gender stereotypes to dominate current conceptions of women and men, and to expect them to not. Relevant research findings are conflicting. For example, a large investigation found that over time managers have come to perceive women as more agentic ( Duehr and Bono, 2006 ). However, other investigations have found gender stereotypes to have changed little over time ( Heilman et al., 1989 ) or even to have intensified ( Lueptow et al., 2001 ). A recent study replicating work done more than 30 years ago found minimal change, with men and women still described very differently from one another and in line with traditional stereotyped conceptions ( Haines et al., 2016 ).

There also have been conflicting findings concerning self-charcterizations, especially in women’s self-views of their agency. Findings by Abele (2003) suggest that self-perceived agency increases with career success. Indeed, there has been indication that women’s self-perceived deficit in agency has abated over time ( Twenge, 1997 ) or that it has abated in some respects but not others ( Spence and Buckner, 2000 ). However, a recent meta-analysis has found that whereas women’s self-perceptions of communality have decreased over time, their self-perceptions of agency have remained stable since the 1990s ( Donnelly and Twenge, 2017 ). Yet another study found almost no change in men’s and women’s self-characterizations of their agency and communality since the 1970s ( Powell and Butterfield, 2015 ).

There are many possible explanations for these conflicting results. A compelling one concerns the conceptualization of the agency and communality constructs and the resulting difference in the traits and behaviors used to measure them. In much of the gender stereotypes literature, agency and communality have been loosely used to denote a set of varied attributes, and different studies have operationalized agency and communality in different ways. We propose that agency and communality are not unitary constructs but rather are comprised of multiple dimensions, each distinguishable from one another. We also propose that considering these dimensions separately will enhance the clarity of our understanding of current differences in the characterization of women and men, and provide a more definitive picture of gender stereotypes today.

Dimensions of Communality and Agency

There has been great variety in how the agency construct has been operationalized, and the specific terms used to measure agency often differ from study to study (e.g., McAdams et al., 1996 ; Rudman and Glick, 2001 ; Abele et al., 2008 ; Schaumberg and Flynn, 2017 ). Furthermore, distinctions between elements of agency have been identified: In a number of studies competence has been shown to be distinct from agency as a separate factor ( Carrier et al., 2014 ; Koenig and Eagly, 2014 ; Abele et al., 2016 ; Rosette et al., 2016 ), and in others, the agency construct has been subdivided into self-reliance and dominance ( Schaumberg and Flynn, 2017 ). There also has been great variety in how the communality construct has been operationalized ( Hoffman and Hurst, 1990 ; Fiske et al., 2007 ; Abele et al., 2008 ; Brosi et al., 2016 ; Hentschel et al., 2018 ). Although there have been few efforts to pinpoint specific components of communality, recent work focused on self-judgments in cross-cultural contexts has subdivided it into facets of warmth and morality ( Abele et al., 2016 ).

The multiplicity of items used to represent agency and communality in research studies involving stereotyping is highly suggestive that agentic and communal content can be decomposed into different facets. In this research we seek to distinguish dimensions underlying both the agency and the communality constructs. Our aim is to lend further credence to the idea that the fundamental constructs of agency and communality are multifaceted, and to supply researchers with dimensions of each that may be useful for study of stereotype evaluation and change.