Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 13 September 2023

The relation between football clubs and economic growth: the case of developed countries

- Murat Aygün ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7636-8325 1 ,

- Yunus Savaş 2 &

- Dilek Alma Savaş 3

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 566 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

6885 Accesses

1 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

A Correction to this article was published on 05 October 2023

This article has been updated

It is believed that societies use sports as a tool for their social and cultural development. In particular, developed countries have embraced sports as part of their lives and have ranked it as a source of economic growth. The increase in sports consumption and industries can contribute to economic growth, and economic growth can have a positive impact on sports industries vice versa. The wavelet methodology is a way to discover the relationship between sports and economic growth by examining frequency and time domain aspects and identifying shorter to longer-term relationships continuously. The industrial production of different countries has experienced short and medium-term cycles around the year 2020. In contrast, the values of football clubs in these countries have shown minimal fluctuations, despite the emergence of some areas with slight significance. The cross wavelet analysis asserted the significance relation revealed after the covid 19 restrictions, both in shorter and longer periods. The wavelet coherence analysis showed that co-movement was observed in short-term cycles in countries across the periods while long-term co-movements are observed only in only in small areas or generally out of cone of influence.

Similar content being viewed by others

The impact of climate change and economic development on fisheries in South Africa: a wavelet-based spectral analysis

Relationship between Macroeconomic Indicators and Economic Cycles in U.S.

Multi-fractal detrended cross-correlation heatmaps for time series analysis

Introduction.

While the field of economics emphasizes the efficient allocation of scarce resources for profit and benefit (Cypher and Dietz 1997 ; Todara and Smith 2012 ), the concept of economic growth is closely linked to social welfare and services (Dumciuviene 2015 ). In the context of developing countries, adopting an international perspective is essential, rather than relying solely on traditional economic approaches (Todara and Smith 2012 ). The acquisition of an international perspective is a crucial requirement for achieving economic growth.

Studies on economic growth and development consistently address contemporary issues such as global poverty, unemployment, and sustainability, necessitating a comprehensive examination of the economy (Nunn 2020 ). Research reveals a clear interrelationship between economic growth and various sectors, including tourism, industry, environment, entertainment, health, and sports. Among these fields, sports exemplify the pronounced effects of economic growth, contributing not only to economic aspects but also to individual personal growth and societal development.

In contemporary society, both ordinary individuals and influential figures in politics and culture recognize the value of sports as a phenomenon with unique functions in personal improvement and its socio-economic consequences (Razvan et al. 2020 ). While modern sports help address certain social issues (Savizn et al. 2017 ), they are also recognized as an important economic sector that establishes new standards (Gratton 1998 ). Initially seen as a means to boost sales, the sports industry is intimately connected to economic growth (Kellett and Russell 2009 ; Kokolakakisn et al. 2019 ), particularly in developed countries (He 2018 ). Remarkable developments have occurred in the sports industry over the past two decades due to the increased affinity for sports (Gratton and Solbery 2007 ). In 2015, the sports industry accounted for approximately 3% of global economic activities (Manoli 2018 ). The industry encompasses mega sports events (e.g., the Olympic Games, world championships, and special international tournaments), media, sponsorship, volunteering, sports equipment, and sports tourism. Sports events, in particular, play a significant role in economic development and sustainability.

While economic growth can influence the sports industry, the growth of sports consumption can also become a new source of economic growth (Kharchenko and Ziming 2021 ). There are various reasons for the rise of economic growth, and the expansion of industries due to increased sports consumption can contribute to this growth (Qiun et al. 2013 ). Although Kobierecki and Pierzgalski ( 2022 ) found no significant effect of mega sports events on economic growth, many countries still desire to host such events due to their potential contribution to the economy.

Football has become a significant investment for many countries worldwide, with the aim of increasing their domestic sports market volume and enhancing international connections (Zhang et al. 2018 ). As a result, sporting events have gained more attention than ever before, and investments have increased alongside this growing interest. While high-level events like the FIFA World Cup and the Olympic Games require billions of dollars for infrastructure, small-level events require national support (Giampiccolin et al. 2015 ; Nauright, 2004 ). Investments in sports infrastructure, including technical, architectural, and superstructure works, are necessary for sports development in cities.

Economic growth is a fundamental prerequisite for combating sportive underdevelopment (Andreff 2001 ). Professional football clubs focus on two goals: success in business performance and success on the field (Guzman 2006 ). In this regard, economic growth is also a crucial consideration for these clubs.

Sports consumption encompasses a range of aspects, from facility construction to sports equipment and sports tourism. Additionally, sports management and sports industry are deeply connected to sports philosophy and activities (Savizn et al. 2017 ). Football, in particular, has gained increasing interest worldwide (Amador et al. 2017 ). Thus, while providing necessary support for football’s economic development, stadiums have become important in maintaining revenue at maximum levels (Ginesta 2017 ). Since the 1980s, events like the Olympic Games and the FIFA World Cup have been driving forces in the global sports market, and this market has emerged as a new area for economic growth (Nauright 2015 ). While the general sports environment may have no effect on the local economy, the Olympic Games (Coates and Humphreys 2003 ), sports franchises (Islam 2019 ; Coates and Humphreys 1999 ), sports tourism (Kurtzman 2005 ; Chersulich Tomino et al. 2020 ), media (Lewis and Gantz, 2019 ), sponsorship (Santomier 2008 ), ticket sales (Gratton and Solberg 2007 ), and sports volunteering (Doherty 2006 ) can all play a significant role in economic growth. Additionally, the general sports environment can also contribute to the formation of social awareness (Pujadas 2012 ).

The recent spread of the economic cycle to various markets (Andreff 2019 ) will lead to a noticeable increase in economic demand in the future (Ahlert 2001 ). Economists have been studying the field of sports since it underwent significant structural changes over the past century, particularly in terms of sponsorship and media. For instance, while television revenues for the 1948 Olympics amounted to £27,000, it is projected to reach $3.6 billion in 2008. Additionally, BSkyB Premier League association football clubs paid over £600 million between 1997 and 2001 (Downward and Dawson 2000 ). Milan AC, one of the wealthiest sports clubs in Italy, saw its revenues grow from 29.3 million euros in 1990 to 177.1 million euros in 2002 (Boroncelli and Lago 2006 ). Moreover, the top four professional sports leagues in North America experienced an annual growth rate of 5.62% between 2006 and 2015 (Bradbury 2019 ). These examples serve as strong evidence of the sustainability of sports in contributing to the growth of the gross national product, from the micro-economic level to the macro-economic level (He 2018 ).

In the contemporary era, it is crucial to examine the correlation between economic growth and developing nations (Akamatsu 1962 ). Research conducted in the field of sports economics, an increasingly popular area of study, encompasses not only the products associated with sports but also the institutions and activities that support the entire process (He 2018 ). Consequently, sports economics has emerged as a noteworthy source of economic growth for governments in the 21st century. Despite the predominant focus on the economic impacts of football, which occupies a prominent position within the realm of sports economics, there has been persistent exploration of the following factors pertaining to football and economic growth: (i) the economic status of the country, (ii) the extent of the economic influence, (iii) political elements, and (iv) the relation between the economy and football. As a result, a significant body of literature exists, aiming to elucidate the origins and significance of the relationship between football and the economy.

Numerous research studies have been conducted employing various analytical methods to investigate different aspects of the economic development and growth of football. These methods include the employment of linear regression models to examine transfers, ticketing, and football club stocks (Dobson and Goddard 2001 ; Grix et al. 2021 ), economic modeling to explore the generation of visitor and television revenue for football clubs (Robertsn et al. 2016 ), empirical analysis to examine the influence of the sports industry on economic growth through revenue (Rohde and Breuer 2016 ; He 2018 ), and regional input-output models to study the involvement of spectators, stadium services, catering, accommodation, and player expenses in the economic growth of football clubs (Robertsn et al. 2016 ). These comprehensive studies significantly contribute to our understanding of the economic dynamics and progress within the realm of football.

However, to gain a more comprehensive understanding, it is necessary to investigate the club values in conjunction with the industrial production growth and subsequent economic expansion. Such an investigation would not only shed light on the direct impact of economic sustainability on football but also introduce a fresh approach and perspective to the existing literature. The present study aims to provide novel insights within a theoretical and practical framework. Specifically, it aims to (i) unveil the relationship between the total club values of G7 countries and their respective economic growth, (ii) determine the influence of football clubs on economic growth and identify the factors that contribute to this growth during the period from November 2010 to December 2021, (iii) conduct a comparative analysis among G7 countries, and (iv) employ wavelet analysis to assess the current state of the relationship between economic growth and propose the most suitable model.

The following section provides detailed information regarding the data structure employed to investigate the relationship between club values and industrial production of G7 countries from November 2010 to December 2021, along with the sources from which the data were obtained. The evolution of industrial production and club values over time is demonstrated through the use of graphs. Subsequently, a comprehensive research approach is employed to thoroughly elucidate the scope and framework of the wavelet methodology, which serves to analyze the effects under consideration. Within the subsequent section, the outcomes derived from the wavelet methodology are presented, specifically focusing on the continuous wavelet spectrum, cross wavelet spectrum, and wavelet coherence results. In the study, the significance of the variables and the relationship between industrial production and club values were examined within the context of the wavelet methodology. The results obtained from the continuous wavelet spectrum, cross wavelet spectrum, and wavelet coherence analysis are presented, highlighting the significance of these variables and their interrelationships. In the final section, the main contributions and findings of the research are summarized and presented.

Data collection

For this analysis, data was gathered from two different sources. The OECD database was used as the first source to obtain information on industrial production. The transfermarkt served as the second source to collect data on club values. The study focused on the G-7 countries to explore the connection between economic growth and club values, and the time period under investigation ranged from November 2010 to December 2021.

With the exception of Canada, which was excluded due to data availability constraints, this research includes an analysis of the United States of America, United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy, and Japan. Per mensem data is separately wielded in this study.

Economic growth is commonly assessed by examining the growth of gross domestic product (GDP). However, due to the unavailability of monthly GDP data, the industrial production index is employed as a substitute for GDP. This choice is supported by the widespread use of industrial production as a proxy for economic growth in economic literature, given its extensive representation of economic activity. it is designated by OECD (oecd.org) that the industrial production as the output of industrial facilities which holding mining, manufacturing, electricity, gas and steam and air-conditioning. Furthermore, the total industrial production index, based on the 2015 reference year, was obtained from the OECD database for each country.

The data for club values were extracted from transfermarkt website. Total club values for each country were taken monthly into consideration so as to obtain longer time series. The data for club values was extracted from the transfermarkt website. Monthly club values for each country were considered to obtain a longer time series. In other words, the starting date was set as November 2010 based on the availability of club value data, and data collection concluded in December 2021. The total club values of countries were measured by selecting the first-tier leagues. Specifically, the first-tier leagues were selected to measure the total club values of countries. The chosen major leagues are Soccer league for US, J1 league for Japan, Bundesliga for Germany, Ligue 1 for France, Seria A for Italy. In order to ensure methodological consistency with the industrial production data, the total club values of the UK were derived by aggregating the values of the following four leagues: Premier League, Scottish Premiership, SSE Airtricity League Premier Division, and Cymru Premier. The natural logarithm of club value series is taken because it provides a relative change in club values over time.

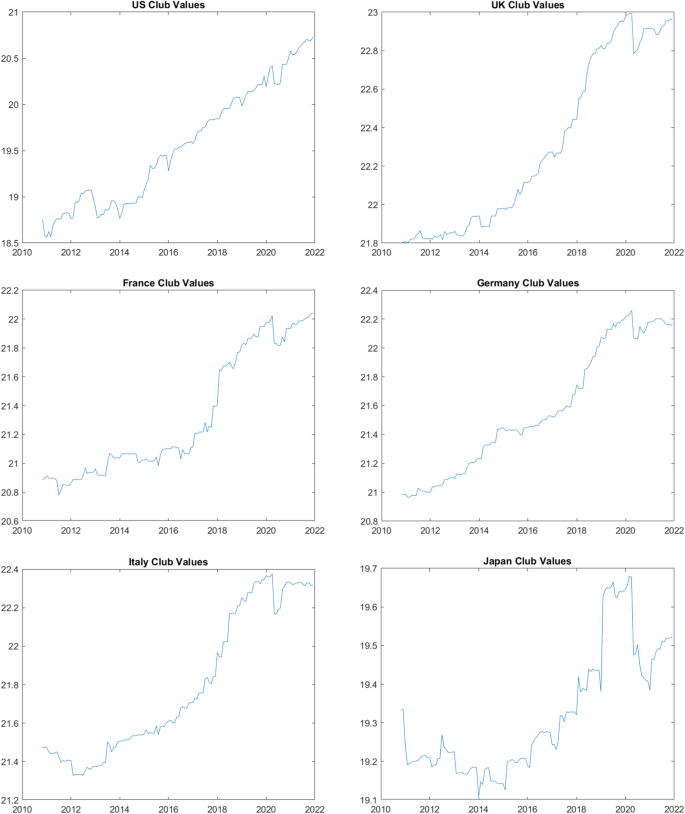

The evolution of club values in the mentioned countries from November 2010 to December 2021 is illustrated in Fig. 1 . The graph shows a noticeable upward trend in club values, although fluctuations can be observed over time. Except for the United States, all countries reached their highest club values in 2020, which were then followed by a sudden decline. Afterward, there was a subsequent increase, but the values did not reach the peak of 2020 within the timeframe depicted in the figures.

The illustration furnished visually encapsulates the progressive transformation of club values within the nations of reference.

Furthermore, Fig. 2 depicts the industrial production index for the aforementioned countries, exhibiting distinct patterns. The United States exhibited an initial upward trend until 2015, followed by a period of decline until 2016, and subsequently experienced a steady increase until 2019. However, a sharp decline occurred thereafter due to the implementation of Covid-19 restrictions, followed by a rapid rebound. In the case of the United Kingdom, there was an upward trend characterized by numerous fluctuations, reaching its peak in 2019. However, this trend transformed into a steady decrease, which abruptly turned into a sharp increase. Similarly, for France, Germany, Italy, and Japan, the industrial production index remained relatively stable with minor fluctuations, although the fluctuations in Japan were somewhat more pronounced. It is worth noting that all countries faced a similar situation, whereby the pandemic-induced restrictions had a significant impact, resulting in a drastic decline in industrial production.

The evolution of the industrial production index in the competing countries is shown visually in the figure.

Methodology

The wavelet methodology is employed to analyze the relationship among variables in both the time and frequency domains. The analysis involves investigating the relations using techniques such as the continuous wavelet spectrum, cross wavelet spectrum, and wavelet coherence analysis. The generation of co-movements continuously with distinguishing time and frequency areas has scaled up the ability to investigate more deeply for the relation of variables, both in short term to medium term and long term. Thanks to these advantages, wavelet coherence approach become highly popular both in natural and social sciences which utilize statistical approaches for empirical researches. In the case of this study, the wavelet methodology enables us to capture the relation amongst cycles of each variable from shorter to longer ones.

The wavelet coherence methodology developed by Goupillaud et al. ( 1984 ) empowers researchers for analyzing non-stationary variables with different time frequencies from short to long cycles. The usage of non-stationary variables without any smoothing technique also stimulate the correctness of the research consequences this is because smoothing variables causes the loss of information in the data.

The formal representation of the wavelet coherence approach is provided by Torrence and Webster ( 1999 ) that X and Y variables interacts with each other in terms of the cross-wavelet spectrum is;

\(W_n^x\left( s \right)\) Illustrates the wavelet transformed X variable and \(W_n^y\left( s \right)\) represents the transformed Y variable and n refers to the time index, s for scale and * is for complex conjugate representation.

Over plus the cross wavelet spectrum, the squared wavelet is;

S stands for time and smoothing operator and s represent the wavelet scale. The value of coefficient varies between 0 and 1, 0 ≤ \(R_n^2\) ≤ 1. The values close to 1 indicates high correlation, 0 indicates low correlation. In graphical representation, the magnitude of correlation is represented by color bar. Furthermore, Monte Carlo simulation with 1000 replication is wielded for the estimation and the routine proposed by Grinsted et al. ( 2004 ) is used with modifications.

Main results and implications

The wavelet results were indicated below so as to display the significance and co-movements amongst variables. Antecedently, the continuous wavelet spectrum of variables signified the fact that industrial productions of countries have more significant areas than club values of countries.

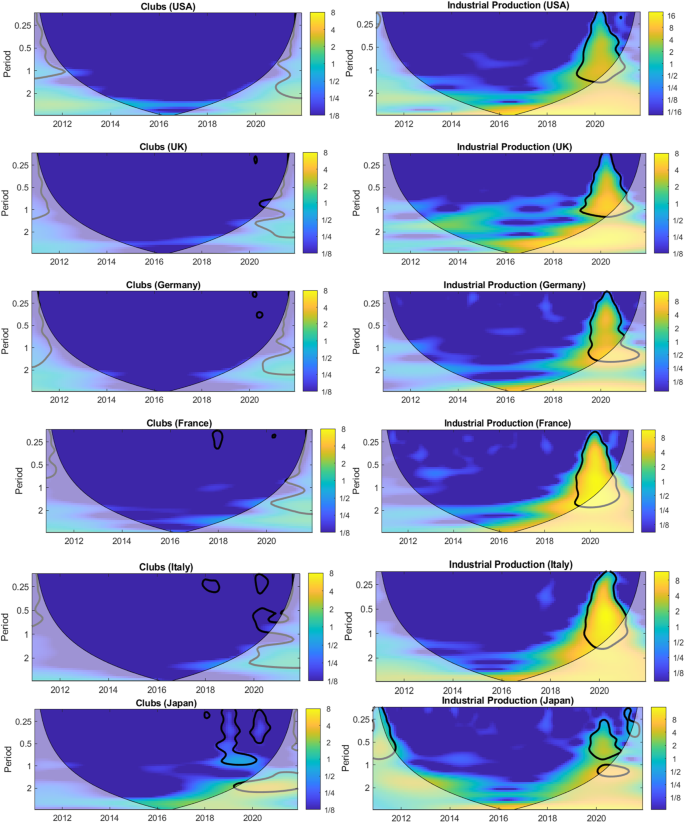

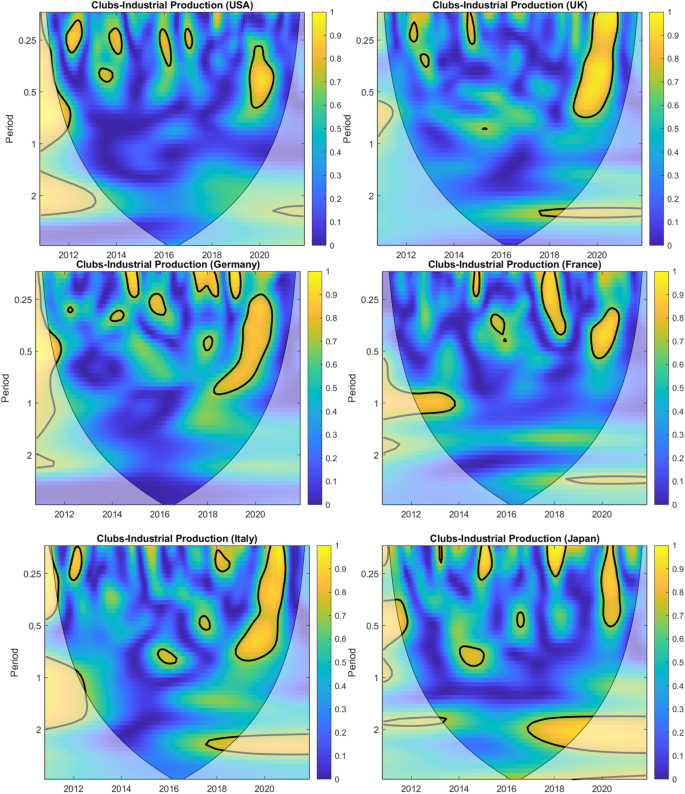

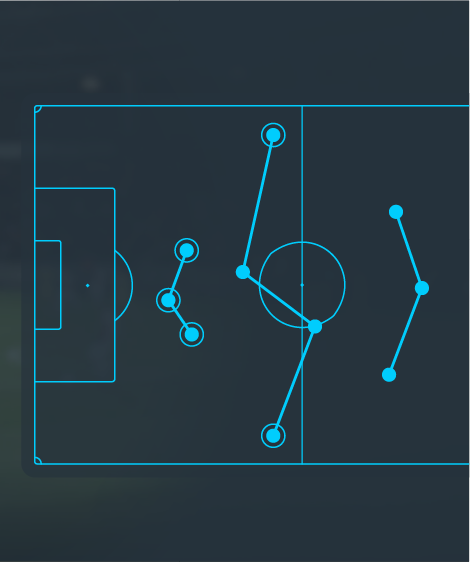

The Fig. 3 demonstrates continuous wavelet spectrum of the club values on the left-hand side and industrial production on the right-hand side. The industrial production of each country has fluctuated around 2020 for short- and medium-term cycles. However, the club values of countries have not significantly fluctuated even though thin significance areas are emerged. Clubs value in USA had not exerted any significance areas in the cone of influence, on the other hand, club values in Italy fluctuated after 2018 with three different significance areas. For the case of UK, France and Germany, thin significance areas are monitored while these areas are not wide.

The frequency is denoted on the vertical axis, while the time period is represented along the horizontal axis. The thin black curve pertains to the cone of influence (COI), signifying the region affected by edge effects. On the spectrum, the color bar to the right transitions from blue to yellow, indicating a shift from low to high power levels.

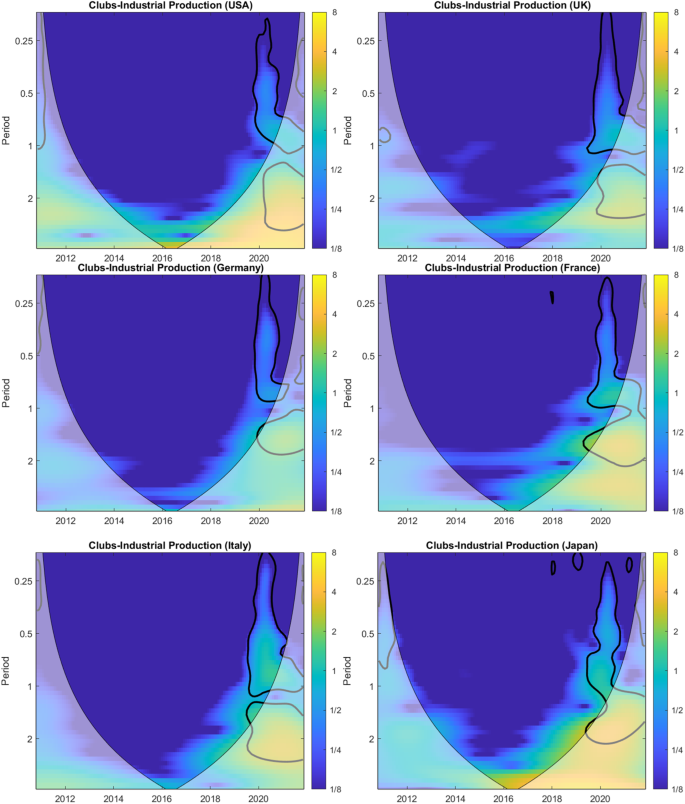

Moreover, the cross wavelet transform of variables asserts that the remarkable relationship between variables is established only from 2019 onwards. This actuality is valid in all countries with slightly difference of significance areas or the degree of significance. Nevertheless, this relationship was not observed in any time or frequency periods before the 2019. The significance areas are exerted after 2020 with expanding frequency periods and time periods. Thicker significance areas are observed in longer frequency periods compare to shorter frequency periods and the same situation is valid for the case of time periods in all country cases.

Figure 4 consist of six different figures for each country in the analysis. The wavelet coherence between football clubs’ value and industrial production indicates that co-movements are often appeared in short-term periods. Country by country analysis unveils different results for each country case, though, the co-movement are tending to unclose in shorter cycle periods with different time periods.

Wavelet coherence analysis applied to the relationship between the value of football clubs and industrial production reveals frequent occurrences of co-movements within short time intervals, even though the time periods are different.

The first figure of the Fig. 5 is the case of USA which indicates that the club values and industrial production co-moves only in shorter cycles with thin areas throughout periods. The only thicker co-movement area compare to other ones in the case of USA is overwatched from 2019 to 2020 between 0, 25 and 0, 50 frequency bands. Neither in medium term nor longer terms cycles are asserted co-movements. There are more co-movement areas out of the cone of influence; however, the only interpretable spaces are where co-movements are in the cone of influence.

The 5% significance level, as determined through Monte Carlo simulations, is depicted by the thick black contour. This contour indicates notable co-movements between club values and industrial production index.

The second case is the case of Italy which exerted small co-movement areas around 2012 and from 2016 to 2018 with three lands for shorter- and medium-term cycles. The co-movement area is around 2019 continues from shorter cycles to medium term cycles with thicker co-movement area. The co-movement exerted in longer cycles is initiated from mid-2017 to end of time period while it was at the out of cone of influence after mid-2018. The case of Italy exerted co-movements from shorter to longer cycle frequencies while it was lesser before 2018.

The third one is the case of United Kingdom which had three different lands from 2012 to 2015 in shorter cycles. Then, the co-movement areas are vanished up to mid-2017. The thicker co-movement area is pursued from mid-2018 to 2020 which ascended in frequency domain from 0 to 0.75 cycle band. The thin co-movement in longer cycles is monitored from mid-2017 to end of time periods while it was at the out of cone of influence after 2018.

The fourth one is the case of France which varies from other cases by the fact that the medium-term cycles revealed in the case of France for the beginning of time period to 2014. Hardly, the co-movements stuck into the shorter cycles after 2014 with existence of three different land from 2014 to 2020. No co-movement is disclosed n higher cycles as it is in the case of Italy and UK.

The Fig. 5 illustrates the wavelet coherence analysis for the case of Japan which included co-movements amongst variables in both shorter and longer cycles. From 0 to 0.5 frequency bands, there is five different co-movement lands throughout time periods and one in the 0.75 frequency band from 2014 to 2015. The co-movement in longer cycles is explored from 2017 to end of time periods which is at out of the cone of influence after 2019 for the 1.75–2.5 frequency band.

The last analysis is for the case of Germany which applied many co-movement lands from 2014 to 2020. The relation amongst variables in Germany is sighted in shorter cycles before 2018 from 0 to 0.5 frequency band with six different lands. The largest co-movement area is from 2018 to 2020 with 0.25–1 frequency bands.

By and large, there is co-movements in shorter cycle periods, nonetheless, the co-movements in longer cycle bands are discovered in many cases. The concentration of co-movements in shorter cycles can indicate that the relation amongst club values and industrial production is exhibited in shorter periods and longer cyclical relations are either limited or none.

Conclusions and research limitations

In consideration of the relationship between football clubs and economic growth of countries, its contribution to the country’s economy is incontrovertible in Europe and America (Yongfeng 2013 ). For this reason, there is an appreciable connection between the sports industry and economic development (Ziming 2021 ). In the 21st century, it is obvious that individuals do sports not only for competition, but also to stay healthy and socialize. All activities carried out for the purpose of sports promote to the economic development of sports. While different sports branches manifest development to the extent the region due to the geographical features of the countries, it is undeniable that the football branch is pivotal throughout the world.

While examining the relationship between football and economic growth from 2010 to 2022, the sports sector has been among the industries affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, which emerged in the final quarter of 2019. With numerous precautionary measures and recommendations implemented during the normalization process by the World Health Organization, the cancellation or postponement of sports events during the initial phase of the pandemic had a negative impact on the football sector. Bond et al. ( 2022 ) used the expression “Football without fans is nothing” due to concerns that the continuation of football without spectators could lead to sustainability and financial issues. This process signifies the beginning of a new economic model in the football world (Parnel et al. 2021 ), prompting sports institutions to embark on new quests (Aygün 2021 ). The International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) attempted to fill this gap through e-sports competitions (Grix et al. 2021 ; Kim et al. 2020 ). Although the void could not be completely filled, allowing football matches to continue without spectators and behind closed doors (Drewes et al. 2021 ) resulted in negative economic consequences for clubs, while the market and player values of clubs remained unaffected (Fig. 1 ).

Sports activities can play a pivotal role in stimulating economic growth by various activities such as ticket sales, tourism, product and service marketing, sponsorships, and media revenues wield substantial economic influence. Moreover, the construction of new facilities and the expansion of their quantity present prospects for managerial and employment opportunities. Simultaneously, prioritizing the enhancement of athlete development infrastructure holds great significance from a policy standpoint, as it fosters the potential to attain national or international success and enhance the caliber of clubs. Consequently, evaluating and interpreting the interplay between football clubs and economic development solely from a singular perspective would be an inadequate approach.

Based on this paper’s findings, there is evidence suggesting a potential short-term correlation between the economy and sports, indicating economic consequences. It is advisable for policymakers in both sports and economics to acknowledge and incorporate this relationship when formulating policies.

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted an interesting observation regarding football clubs. Despite the imposed restrictions and a notable decrease in industrial production, these clubs managed to recover their economic value over time. This resilience displayed by sports institutions indicates their ability to withstand shocks stemming from real-world events. Moreover, they can play a temporary role in mitigating the economic ramifications of such events on the overall economy.

In our research, the relationship between the changes in the values of football clubs and industrial production as a proxy for economic growth has been analyzed using the wavelet methodology. Following the searches, the relationship between our variables initiated after 2019 according to the cross wavelet analysis and the relationship that emerged in a narrower area in the context of the time domain in short cycles propounded an expansion in the context of time-domain since it had a progression towards longer cycles, and this is pertinent for all countries. When considered wavelet coherence analysis, which presents the common movement of the variables, common movements are observed more frequently in short cycles, albeit they have been included in a narrow area in countries such as Italy, France and the United Kingdom in longer cycles.

Additionally, this paper has several limitations, outlined as follows: Firstly, due to the unavailability of monthly GDP data, economic growth was measured using the industrial production index. Secondly, the time period of analysis was limited to November 2010 to December 2021, which represents the only available period with club value data during the research conducted. Thirdly, the study does not include the case of Canada due to a lack of available club value data for analysis. Another limitation is that the wavelet methodology is typically conducted with time series analysis, which restricts the inclusion of countries to only a select few. However, incorporating a wide range of countries using panel data models could yield valuable insights for future research endeavor.

This study makes an incredibly valuable contribution by exploring the relationship between economic growth and sport, which is a well-known but under-researched area. Furthermore, football stands as the largest sports industry worldwide, making it the primary focus of this research. The study aims to examine the economic changes of football clubs over time as an indicator of the growth of the sports industry. Moreover, the evaluation centers on the biggest football clubs in developed countries, which have achieved significant economic and sporting success. The technique employed in this study allows for the identification of the frequency and duration of these relationships, whether they are short-term, medium-term, or long-term. This novel approach not only provides fresh insights but also opens up new avenues for research in sports economics. It highlights that football and economic growth establish connections that vary across different time periods, ranging from short to long term. To sum up, it can be concluded that the relationship between football club values and economic growth has been highlighted after 2019 and that their joint movements are mostly short-term across all periods.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

05 october 2023.

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02202-y

Ahlert G (2001) The economic effects of the soccer world cup 2006 in Germany with regard to different financing. Econ Syst Res 13(1):109–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/09535310120026274

Article Google Scholar

Akamatsu K (1962) A historical pattern of economic growth in developing countries. Dev Econ 1:3–25

Amador L, Campoy-Munoz P, Cardenete MA, Delgado MC (2017) Economic impact assessment of small-scale sporting events using social accounting matrices: an application to the Spanish Football League. J Policy Res Tourism Leisure Events 9(3):230–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2016.1269114

Andreff W (2001) The correlation between economic underdevelopment and sport. Eur Sport Manag Q 1(4):251–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740108721902

Andreff W (2019) Sport events, Economic Impact and Regulation. International sport marketing. (Desbordes B, Richelieu A Ed). Routledge, London

Google Scholar

Aygün M (2021) Covid-19 effect in sports organizations. J Youth Res 9(23):49–52

Bond AJ, Cockayne D, Ludvigsen JAL, Maguire K, Parnell D, Plumley D, Widdop P, Wilson R (2022) Covid-19: the return of football fans. Manag Sport Leisure 27(1-2):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1841449

Boroncelli A, Lago U (2006) Italian football. J Sports Econ 7(1):13–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002505282863

Bradbury JC (2019) Determinants of revenue in sports leagues: an empirical assessment. Econ Inq 57(1):121–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12710

Chersulich Tomino A, Peric M, Wise N (2020) Assessing and considering the wider impacts of sport-tourism events: a research agenda review of sustainability and strategic planning elements. Sustainability 12(11):4473. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114473

Coates D, Humphreys BR (1999) The growth effects of sports franchises, stadia, and arenas. J Policy Anal Manag 18(4):601–624

Coates D, Humphreys BR (2003) Professional sport facilities: franchise and urban economic development. Public Finance Manag 3(3):335–357

Cypher JM, Dietz JL (1997) The process of economic development. Routledge, London

Dobson S, Goddard J (2001) The economics of football. Cambridge, United Kingdom

Book Google Scholar

Doherty A (2006) Sport volunteerism: an introduction to the special issue. Sport Manag Rev 9(2):105–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1441-3523(06)70021-3

Downward P, Dawson A (2000) The economics of professional team sports. Routledge, London and New York

Drewes M, Daumann F, Follert F (2021) Exploring the sports economic impact of Covid-19 on professional soccer. Soccer Soc 22(1-2):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2020.1802256

Dumciuviene D (2015) The impact of education policy to country economic development. Proc Soc Behav Sci 191:2427–2436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.302

Giampiccoli A, Lee SS, Nauright J (2015) Destination South Africa: Comparing global sports mega-events and recurring localised sports events in South Africa for tourism and economic development. Curr Issues Tourism 18(3):229–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.787050

Ginesta X (2017) The business of stadia: maximizing the use of Spanish football venues. Tourism Hosp Res 17(4):411–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358416646608

Goupillaud P, Grossmann A, Morlet J (1984) Cycle-Octave and related transforms in seismic signal analysis. Geoexploration 23(1):85–102

Gratton C (1998) The economic importance of modern sport. Cult Sport Soc 1(1):101–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/14610989808721803

Gratton C, Solberg HA (2007) The economics of professional sport and the media. Eur Sport Manag Q 7(4):307–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740701717030

Grinsted A, Moore JC, Jevrejeva S (2004) Application of the cross wavelet transform and wavelet coherence to geophysical time series. Nonlinear Process Geophys 11(5-6):561–566. https://doi.org/10.5194/npg-11-561-2004

Article ADS Google Scholar

Grix J, Brannagan PM, Grimes H, Neville R (2021) The impact of Covid-19 on sport. Int J Sport Policy Polit 13(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2020.1851285

Guzman I (2006) Measuring efficiency and sustainable growth in Spanish football teams. Eur Sport Manag Q 6(3):267–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740601095040

He Y (2018) A study on the impact of sport industry on economic growth: an investigation from China. J Sport Appl Sci 2(2):1–10. https://doi.org/10.13106/jsas.2018.Vol2.no2.1

Islam MQ (2019) Local development effect of sports facilities and sports teams: case studies using synthetic control method. J Sports Econ 20(2):242–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002517731874

Kellett P, Russell R (2009) A comparison between mainstream and action sport industries in Australia: a case study of the skateboarding cluster. Sport Manag Rev 12(2):66–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2008.12.003

Kharchenko T, Ziming L (2021) The relationship between sports industry development and economic growth in China. Oblik i finansi. Inst Account Finance 1(91):136–140. https://doi.org/10.33146/2307-9878-2021-1(91)-136-140

Kim YH, Nauright J, Suveatwatanakul C(2020) The rise of E-Sports and potential for Post-Covid continued growth. Sport Soc 3(11):1861–1871. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1819695

Kobierecki MM, Pierzgalski M (2022) Sports mega-events and economic growth: a synthetic control approach. J Sports Econ 23(5):567–597. https://doi.org/10.1177/15270025211071029

Kokolakakis T, Gratton C, Grohall G (2019) The economic value of sport. Sports Economic. (Downward P, Frick B, Humphreys B R, Pawlowski T, Ruseski J E, Soebbing B P. Ed.). SAGE Publications, UK

Kurtzman J (2005) Economic impact: sport tourism and the city. J Sport Tourism 10(1):47–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775080500101551

Lewis N, Gantz W (2019) An online dimension of sports fanship: fan activity on nfl team-sponsored websites. J Global Sport Manag 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2018.1441739

Manoli AE (2018) Sport marketing’s past, present and future; an introduction to the special issue on contemporary issues in sports marketing. J Strateg Mark 26(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2018.1389492

Nauright J (2004) Global games: Culture, political economy and sport in the globalised world of the 21st century. Third World Q 25(7):1325–1336. https://doi.org/10.1080/014365904200281302

Nauright J (2015) Beyond the sport-media-tourism complex: an agenda for transforming sport. J Int Council Sport Sci Phys Educ 68(5):13–19

Nunn N (2020) The historical roots of economic development. Science 367(6485):eaaz9986. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz9986

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Parnel D, Bond AJ, Widdop P, Cockayne D (2021) Football Worlds: business and networks during COVID-19. Soccer Soc 22(1-2):19–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2020.1782719

Pujadas X (2012) Sport, space and the social construction of the modern city: the urban impact of sports involvement in Barcelona (1870-1923). Int J History Sport 29(14):1963–1980. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2012.696348

Qiu YH, Luo XJ, Liu YQ (2013) The influences of sports consumption on expanding domestic needs and its function of promoting economic growth. In: Qi E, Shen J, Dou R Ed The 19th international conference on industrial engineering and engineering management. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-38433-2_34

Chapter Google Scholar

Razvan BMC, Bogdan BG, Roxana D, Catalin PM (2020) The contribution of sport to economic and social development. Educatio Artis Gymnasticae 1:27–38. https://doi.org/10.24193/subbeag.65(1).03

Roberts A, Roche N, Jones C, Munday M (2016) What is the value of a Premier League football club to a regional economy? Eur Sport Manag Q 16(5):575–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2016.1188840

Rohde M, Breuer C(2016) Europe’s elite football: financial growth, sporting success, transfer investment, and private majority investors. Int J Financial Stud 4(2):1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs4020012

Santomier J (2008) New media, branding and global sports sponsorship. Int J Sports Market Spons 10(1):9–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijsms-10-01-2008-b005

Saviz Z, Randelovic N, Stajanovic N, Stankovic V, Siljak V (2017) The sports industry and achieving top sports results. Facta Univ Phys Educ Sport 15(3):513–522. https://doi.org/10.22190/FUPES1703513S

Todara MP, Smith SC (2012) Economic development, 11th ed. Addison-Wesley, Harlow

Torrence C, Webster P, Torrence C, Webster P (1999) Interdecadal changes in the esnomonsoon system. J Clim 12(8):2679–2690

Yongfeng HE (2013) A comparative study of sports industry between China and developed countries. Cross Cult Commun 9(6):117–120. https://doi.org/10.3968/j.ccc.1923670020130906.2919

Zhang JJ, Kim E, Marstromartino B, Qian TY (2018) The sport industry in owing economies: critical issues and challenges. Int J Sports Market Spons 19(2):110–126. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-03-2018-0023

Ziming L (2021) Management of sports industry: moving to economic development. Marketi Manag Innov 4:230–236. https://doi.org/10.21272/mmi.2021.4-18

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Physical Education and Sports, Department of Sport Management, Ardahan University, Ardahan, Turkey

Murat Aygün

Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Department of Economics, Bitlis Eren University, Bitlis, Turkey

Yunus Savaş

Department of Finance and Banking, Ahlat Vocational School, Bitlis Eren University, Bitlis, Turkey

Dilek Alma Savaş

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the manuscript’s conceptualization, editing, and finalization and are worthy of their inclusion as authors. The aspects of the study handled by each author are given below: (a) M.A.: conceptualized the overall study scope, design; (b) Y.S.: prepared methodology and conducted the analyses and extracted the results; (c) D.A.S.: supervise the study and reviewed the manuscript. The manuscript has been revised by all authors in accordance with the feedback from the reviewers. All authors participated in drafting the manuscript and endorsed the final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Murat Aygün .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Additional information.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Dataset all, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Aygün, M., Savaş, Y. & Alma Savaş, D. The relation between football clubs and economic growth: the case of developed countries. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 566 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02074-2

Download citation

Received : 02 February 2023

Accepted : 05 September 2023

Published : 13 September 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02074-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Manchester United: A Strategic Analysis of Football Business

- Published: November 15, 2023

- By: Yellowbrick

Manchester United: Business Case Study in Football

Football is not only a sport but also a multi-billion-dollar industry that encompasses various aspects of business management. One of the most successful and globally recognized football clubs is Manchester United. With a rich history and a massive fan base, Manchester United serves as an intriguing case study for those interested in the business side of football. In this article, we will delve into the key elements that contribute to Manchester United’s success and explore the various business strategies employed by the club.

1. Branding and Global Reach

Manchester United has successfully established itself as a powerful brand worldwide. The club’s iconic red jersey, the Manchester United logo, and the famous “Red Devils” nickname have become synonymous with success, passion, and tradition. The club’s global reach is remarkable, with a massive fan base spread across different continents. This extensive fan base allows Manchester United to tap into various revenue streams, such as merchandise sales, sponsorships, and broadcasting rights.

2. Sponsorship Deals and Partnerships

Sponsorship deals play a crucial role in the financial success of modern football clubs, and Manchester United is no exception. The club has managed to secure lucrative partnerships with global brands such as Adidas, Chevrolet, and Aon. These sponsorship deals not only provide significant financial support but also enhance the club’s brand image and visibility. Manchester United’s ability to attract such high-profile sponsors is a testament to its global appeal and marketability.

3. Stadium and Matchday Revenue

Old Trafford, Manchester United’s home stadium, is one of the most iconic football grounds in the world. With a seating capacity of over 74,000, the stadium generates substantial matchday revenue through ticket sales, hospitality packages, and concessions. Manchester United’s ability to consistently fill the stadium showcases the unwavering support of its passionate fan base and adds to the club’s financial stability.

4. Broadcasting Rights

Television broadcasting rights are a significant source of revenue for football clubs, and Manchester United has secured lucrative deals with various broadcasters. The club’s success on the pitch, combined with its global fan base, makes it an attractive proposition for broadcasters looking to capture a massive audience. These broadcasting deals not only provide financial rewards but also help increase the club’s exposure and maintain its global reach.

5. Youth Academy and Player Development

Manchester United’s success is not solely reliant on financial strategies but also on its commitment to nurturing young talent. The club’s renowned youth academy has produced numerous world-class players over the years, including the likes of Ryan Giggs, Paul Scholes, and David Beckham. This emphasis on player development not only strengthens the team but also provides Manchester United with a valuable asset in terms of player transfers and potential revenue generation.

6. Digital Engagement and Social Media

In today’s digital age, football clubs need to engage with fans beyond the traditional matchday experience. Manchester United has embraced digital platforms and has a strong presence on social media channels. The club’s official website, mobile applications, and social media accounts provide fans with exclusive content, merchandise, and opportunities to interact with the club. This digital engagement helps foster a sense of community and loyalty among Manchester United’s global fan base.

7. Commercial Partnerships and Merchandising

Manchester United’s commercial partnerships extend beyond traditional sponsorships. The club has collaborated with various brands to create exclusive merchandise and fashion collections. These collaborations not only generate additional revenue but also help the club tap into different markets and demographics. Manchester United’s ability to consistently innovate and expand its merchandise offerings keeps the brand fresh and appealing to fans worldwide.

Manchester United serves as an excellent business case study in the football industry. The club’s success can be attributed to a combination of strategic branding, global reach, sponsorship deals, stadium revenue, broadcasting rights, player development, digital engagement, and commercial partnerships. By analyzing Manchester United’s business strategies, aspiring professionals in the football industry can gain valuable insights into the key factors that contribute to sustained success in this competitive field.

Key Takeaways:

- Manchester United’s success is driven by strategic branding, global reach, and extensive sponsorship deals with high-profile brands.

- The club’s matchday revenue, generated through ticket sales and hospitality packages, contributes to its financial stability.

- Securing lucrative broadcasting rights helps Manchester United maintain its global exposure and reach a massive audience.

- The club’s commitment to player development through its renowned youth academy strengthens the team and provides valuable assets for player transfers.

- Digital engagement and social media play a vital role in fostering a sense of community and loyalty among Manchester United’s global fan base.

- Commercial partnerships and innovative merchandising efforts allow the club to tap into different markets and demographics.

To excel in the football industry, it is essential to have a solid understanding of the business side of the sport. Consider enrolling in the NYU Fundamentals of Global Sports Management offered by Yellowbrick. This online course and certificate program provide valuable knowledge and insights into the intricacies of the football business, equipping you with the skills needed for a successful career in this dynamic field.

Enter your email to learn more and get a full course catalog!

- Hidden hide names

- Hidden First Name

- Hidden Last Name

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

More from Yellowbrick

Yellowbrick Recognized as Top EdTech Company in North America by TIME and Statista

We are thrilled to announce that Yellowbrick has been named the leading EdTech company in North America and sixth globally in the prestigious “World’s Top

How to Become a Film Festival Programmer: Tips and Insights

Discover how to become a film festival programmer. Learn the essential skills, networking tips, and steps to break into this exciting cinema industry.

Fashion & Architecture: Exploring the Influence in Design

Explore how architecture shapes fashion from structural designs to materials, colors, and sustainability. Immerse in the intersection of these creative realms.

ABOUT YELLOWBRICK

- Work at Yellowbrick

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

STUDENT RESOURCES

- Scholarships

- Student Login

- Beauty Business Essentials

- Beauty Industry Essentials

- Ecommerce Essentials

- Fashion Business Essentials

- Fashion Industry Essentials

- Footwear Business Essentials

- Gaming & Esports Industry Essentials

- Global Sports Management

- Hospitality Industry Essentials

- Music Industry Essentials

- Performing Arts Industry Essentials

- Product Design Essentials

- Sneaker Essentials

- Streetwear Essentials

- TV/Film Industry Essentials

- UX Design Essentials

©2024 Yellowbrick · All Rights Reserved · All Logos & Trademarks Belong to Their Respective Owners

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- 16 May 2022

“What Can Data Do for a Football Club?” A Case Study of Brentford F.C.

Brentford F.C. are regularly described as a Moneyball club. Like Oakland Athletics, the baseball team featured in Martin Lewis’s book Moneyball which became a film starring Brad Pitt, the West London club has used data analysis to overcome the limitations of a small budget, doing things differently from other clubs. As Rasmus Ankersen, Co-Director of Football at Brentford, puts it: ‘ For David to beat Goliath, he needed to use a different weapon. If David had used the same weapon, he would have lost the battle. You’ve got to find your weapons. That’s what Brentford is about. ’

Such success is a welcome change for Brentford fans. Back in the 2013-14 season, the club were playing in League One, the third tier of English football. Back in 2008, they finished in the bottom half of the fourth tier. They have not played in the top flight since 1947, the first season after the end of the Second World War, and have never won a major cup.

Their recent rise has been remarkable, but to simply say it is down to their use of spreadsheets and statistics would be an oversimplification. Data analysis has been an important tool for Brentford, one of the weapons they have used to fight football’s Goliaths, but just as important has been the intelligent and pragmatic way they have used it.

Matthew Benham’s Ownership

Things started to change at Brentford in June 2012, when current owner Matthew Benham became the majority shareholder. For Benham, a lifelong fan of the club, the appeal of buying the club was partly sentimental. He attended his first Brentford match as an 11-year-old in 1979, watching the Bees beat Colchester United in the old Division Three and had supported them ever since. In the years before he bought a controlling stake in the club, he had invested significant sums to help keep the club afloat.

The season before he bought the club, they finished ninth in League One. It did not take long for their fortunes to change. In the 2013-14 season they won promotion after finishing second and the next season they finished fifth in the Championship . Since then the club has consistently finished in the top half of the division and reached the semi-final of the EFL Cup in 2020-21.

Benham made his millions with sports betting companies, including the company Smartodds which he founded in 2004. Smartodds uses statistical research to help its clients better understand the gambling market and increase their chances of beating the bookies. Their research team provides detailed analysis of the data from various football leagues around the globe in order to predict future outcomes.

Benham has brought a similar emphasis on data and statistical research to football, although he has always been keen to emphasise that the club combines the use of data with more traditional approaches. Behind the scenes he has brought in people with an expertise in data and performance analysis, including the two Co-Directors of Football, Rasmus Ankersen and Phil Giles. Giles worked for Smartodds as Head of Quantitative Research and has a PhD in statistics. Ankersen briefly played in Denmark for FC Midtjylland before injury ended his career prematurely. He is a published author, public speaker and the source of the most memorable soundbites about how the club is run. Robert Rowan, who has also been crucial behind the scenes in his role as the club’s Technical Director, tragically died in 2018 at the age of 28.

Data has been important, but it is certainly not the case that since Benham has taken over every decision made at Brentford has been simply a matter of statistics. Back in 2014, Benham told fans, ‘ We use some elements of Smartodds’ models at Brentford. But it’s only a small part of the process .’ The club has undergone a flexible and gradual change, rather than an overnight revolution. Benham has invested over £100 million in the club, but rather than using such money to fund extravagant transfers, he has tried to make the club sustainable and self-sufficient. The club has tried to find ways to use data to do things differently off the pitch in order to gain an advantage on it. One of the key ways the club has done this is by altering the way players are recruited.

Closing the Academy

One way smaller clubs can aim to be self-sufficient is to invest in youth development. Norwich City have had success in recent years by bringing players through their academy and then selling them on.

In the early years of Benham’s ownership, the club was keen on this route, with Benham considering upgrading the academy. However, the club came to realise that for them this approach was not effective. In 2016, the club lost two of their best academy prospects. Ian Carlo Poveda was snapped up by Manchester City and Josh Bohui left for Manchester United. Because the players were both under 16, and therefore too young to have signed professional contracts, the Manchester clubs only had to pay a very small amount of compensation for the players—about £30,000 each.

Brentford were spending £1.5 million a year on the academy, but most of the players coming through the academy did not make the grade. Those who did show a lot of potential were leaving for bigger clubs before Brentford could develop them into first team players or sell them for a significant profit.

So the club ditched their academy. Instead, the club decided to focus on recruiting from overseas, where transfer fees are generally smaller, and picking up young talented players who have been overlooked in the English game.

The club’s youth teams were replaced with a B team, which exists to develop the club’s younger signings and prepare them for the first team, including players from Germany and Denmark as well as players let go from the academies of bigger clubs. Ankersen has explained that ‘ If you look at the number of players released by Premier League academies, that’s a massive number. They make mistakes .’ The B team system allows Brentford to recruit and nurture that talent. The club closely scout the youth teams of the top clubs, gathering detailed information on each player, meaning that if a player with potential becomes available to sign they can swoop in.

As the club has moved up the football ladder, their transfer policy has been remarkably profitable. Brentford have shown a remarkable talent for finding undervalued players to sign at a cheap price, improving their skills on the training pitch and then selling them on for big fees.

Since 2016, Brentford have spent about £75 million on transfer fees, but recouped over £190 million in sales. Neal Maupay was signed from French side Saint-Étienne for about £1.6 million in 2017 and sold to Brighton and Hove Albion two years later for a fee in the region of £20 million. Ollie Watkins, signed from Exeter City for about £6.5 million in the same year the club signed Maupay, was sold to Aston Villa for just over £30 million in 2020. The club has also made a very healthy profit on players such as Saïd Benrahma and Andre Gray.

The profits from this transfer policy have allowed the club to build a new stadium, which they moved into in 2020, and compete for promotion to the top flight against clubs with much bigger revenue bases. With each sale, they seem able to find the next talent to fill the vacated position in the side. After losing Ollie Watkins, they bought in Ivan Toney from Peterborough. Toney finished the 2020-21 season as the top goalscorer in the Championship .

The players the club has sold for the biggest profits have been those they have found abroad, such as Maupay and Benrahma, both from French football, and those who were playing a lower league clubs in England, such as Watkins at Exeter, Andre Gray at Luton and Scott Hogan at Rochdale.

One way they have used data to find such players, is by creating models to compare the strength of teams from different leagues. This allows Brentford to find sides doing well in leagues which are less high profile and in which players are more cheaply available. They can then scout these players in more detail. As Ankersen has said, when describing the club’s transfer policy, ‘ It’s not that data tells you who to pick, data can tell you where to look .’

Once the club knows where to look, they then use more conventional scouting methods. Ankersen has said that, “ There’s no player I’ve ever recruited at Brentford without data having its say, but also no player recruited without the traditional method having had a say .”

This way of doing things does not always work out. In January 2017 the club signed Henrik Johansson, an 18-year-old from Sweden after discussing the player with Smartodd’s own Swedish football analyst as well as doing their own scouting. The player failed to develop into a first-team regular. Making the right signing is not an exact science.

Evaluating Success

As well as talking about the club’s transfer policy, Ankersen has also spoken about the way the club uses analytics to judge success, revealing that, ‘ We don’t look so much at the league table position when we evaluate performance. What we look at are the underlying metrics, which we believe are a better indication of where we are going and how we’ve done .’

This is based on the idea that because football is a low-scoring sport, temporary swings of luck can impact results and give a false picture of whether a team is performing well or not. One fluke goal can turn a win into a drawer. This contrasts with higher scoring sports, such as basketball, where one moment of good or bad luck is less likely to influence the overall outcome.

The way the club evaluates performance means that it is not always easy for outsiders to predict whether a manager will stay or be let go. In 2015, Brentford made the surprise decision not to offer a new contract to manager Mark Warburton. Warburton had achieved promotion the previous season and the team were looking good to finish in the play offs in the Championship. Normally, such a manager would be seen as performing well in the job, but it has been suggested that the club’s data showed that the team had overachieved due to luck and that the success on the pitch did not truly reflect their performances.

For those outside a club, knowing exactly why a manager has been let go is often partly guesswork and in the case of Warburton there was also speculation of a row about transfer policy between the manager and the rest of the recruitment team. Whatever the precise reason, the manager exited the club at the end of the season despite seeming to have achieved success on the pitch.

The early days of Thomas Frank’s spell in charge were another occasion when the club’s evaluation of a manager’s performance did not match the team’s performances in the league. After the Danish manager took charge following the departure of Dean Smith, he lost eight of his first ten matches. Such a terrible start at a different club could well have resulted in the manager being swiftly sacked and his appointment written off as a mistake. But Brentford must have seen enough in their underlying metrics to keep faith in the manager. They have been duly rewarded, with Frank twice guiding the club to the play-offs.

Other Clubs Following Suit

As well as owning Brentford, Benham also owns the Danish side FC Midtjylland, becoming their major shareholder in 2014, two years after acquiring Brentford. Brentford’s Co-Director of Football, Rasmus Ankersen, serves as part-time chairman to the Danish club and data specialist Ted Knutson worked as Head of Player Analytics for both clubs before going on to co-found sports data company StatsBomb. As the overlapping personnel would suggest, data has been just as important to the Danish club as it has been to Brentford, although with even greater success. The club won its first ever Danish Superliga title in 2015 and has won it twice more since then.

After the success achieved by Brentford and FC Midtjylland, and the resulting publicity about the methods used, it is no surprise that other clubs are attempting similar methods.

Of course, Brentford were not the first club to use data in sport. Their ‘Moneyball’ tag is a reminder that such methods were pioneered in American sports. But, alongside Liverpool, they have been one of the first to apply it to football. They have also shown how it can be made to work without the kind of large budget that Liverpool have available. This pioneering work has seen other clubs in English football start to adapt a similar approach.

Barnsley are one example. In December 2017 the Yorkshire club were bought by a consortium led by Chinese-American businessman Chien Lee. The consortium included Billy Beane, who had been manager of the Oakland Athletics baseball team when they achieved their data-driven success, and Paul Conway of the Pacific Media Group, a group which has bought clubs all over the world including AS Nancy in France, Esbjerg fB in Denmark and Belgian side KV Oostende.

Like Brentford, Barnsley are a team without much top flight pedigree. They finished 19 th in the Premier League in the 1997-98 season, their only season in the top tier of English football. But at the end of the 2020-21 season they qualified for the Championship play-offs despite having one of the smallest budgets in the division, and at the time of writing they could face Brentford at Wembley in the play-off final.

Like Brentford, Barnsley aim to recruit from unexpected places to keep costs down and unearth hidden talent using data analysis. Their player of the season in 2021, Michał Helik was signed from Polish football and they currently have striker Daryl Dike on load from American side Orlando City. The involvement of the Pacific Media Group mean that Barnsley are part of a wider football family that share an ethos on signing young players and developing them to sell on for a profit. Paul Conway has explained that whereas most clubs target one or two players, the Pacific Media Group work so that they ‘ always have a long list of targets (often as many as 20 for a given position .’ If one target is too expensive to sign, they move on to a different player on the database.

Ipswich Town, who play in League One, have recently been bought by the American investment group Gamachanger 20 Limited. Since the takeover, the club have announced that they plan to follow a data driven approach to player recruitment. The club’s General Manager of Football Operations, Lee O’Neill, has specifically mentioned the example of Brentford as part of the reason the club is adapting this approach, saying, ‘ We have looked at what clubs like Leicester and Brentford have done for a few years . . . The days of just going off someone’s opinion are going. It’s about identifying a player and breaking down the analysis to find out how you get the best out of that player and whether he will fit into the way you want to play. ’[8]

But if Ipswich are to follow in Brentford’s footsteps, the way they make use of the data will be more important than the data itself. Robert Rowan has joked about how people perceive Brentford’s approach: ‘ A lot of people seem to think this place is full of robots providing the recipe for success but there is no secret formula .’ What the club has done is find practical ways to use data to complement their strategy and make the most of their limited resources. The success of Brentford in recent seasons has shown that, when used well, data is a powerful tool which can allow the Davids of football to compete against the Goliaths.

Share this article

Related Articles

Our team provides news and insights from the cutting edge of football analysis.

- March 12, 2024

What Is a Hat Trick in Football and Its Significance as a Dream Achievement!

- March 8, 2024

Unlocking Victory: Why Football Clubs Must Teach Players About Data

- February 5, 2024

What is The IFAB – The International Football Association Board

- February 2, 2024

Who is Charles Reep?

News Letter Sign Up

Useful Links

Privacy overview.

Simple view

Full metadata view

CSR and tax planning : case study of football club

corporate social responsibility

tax planning

corporate finance

Purpose: Based on a review of recent literature, this paper presents the association between tax planning and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Four dimensions of CSR were applied for this study: managerial, economic, social, and environmental. The study verifies the relation between CSR and tax planning in the aforementioned dimensions. Design/Methodology/Approach: Research is based on the case studies of the Legia Warszawa Football Club Limited Company - one of the best Polish football clubs - during the period between 2011 and 2014 and the Legia Warszawa Football Academy Foundation during the same period. The football club was chosen due to strong relations between sports and CSR. The case study is based on a comparative dynamical and structural analysis of financial data. The fundamental for the case study was the review of previous literature and legal analysis. Findings: This study shows how the company is committed to both social responsibility and tax planning. The case study confirms that CSR was performed in four dimensions. The confirmation was provided, described and analysed based on the business model of the chosen entity. Furthermore, it is possible to observe that performance of CSR is noticed mainly in the managerial and economic dimensions. Research/practical implications: Due to the CSR activities performed and planned by the foundation, the company gained a wide range of benefits. Positive effects of CSR management and tax planning in the current case can be seen mainly due to the use of legal opportunities. Originality/Value: The study proposes how the business model of the football club and foundation can achieve their common goals. It presents how economically important the cooperation between the foundation, which materializes the CSR activities, and the football club, a profit-making company, can be. The study also describes how it is possible to observe the relation between CSR and tax planning in case of the sports club.

* The migration of download and view statistics prior to the date of April 8, 2024 is in progress.

Views per month, views per city, collections.

Manchester United Football Club Report

Introduction.

This paper discusses football as a business and more so, focuses on Manchester United as one of the most recognized football clubs in England. The paper analyses the clubs business strategy, its competitive position as compared to other clubs, its resources and capabilities and finally how it can improve on its management strategies to ensure survival.

Currently, Football is considered as one of the business industry that is growing tremendously. The business strategy used in football can easily be retrieved since the competition in the football arena has been found to be highly structured and the results easily and clearly measured. The outcomes are measured in the line of success in financial management, performance at the pitch, the number of games won and lost, the number of trophies won within certain duration of time and also the league positions (Szymanski, 1998, pp 47-54).

The wage costs that were recorded in the English Premier League clubs in 2005/2006 increased to above EUR 850 million. The clubs that attained the first five positions recorded wage costs as follows; Chelsea 114 million, Manchester United 85 million, Arsenal 83 million and Newcastle United 52 million. The wage cost is however expected to hit more than 1 billion Euros in the Premier league in the near future (Waltersdorf, 2007). Manchester United and arsenal were recorded to have spent more than 250 million euro in the process of expanding their stadia.

Manchester United has been considered as one of the most successful English football club within the last two decades. It has won the premier league eight times since 1992, the FA cup it has won more than five times since 1970. The club has also performed so well financially generating an income of £249 of which 66m of this was reported as profit and this was between the years 1992 and 1997 (Szymanski, 1998, pp 47-54).

Identify Manchester United’s strategy and explain its rationale.

Manchester United football club has been known currently as one of the best football clubs in the world. The top five current stakeholders of the club include; Malcolm and family, Magnier and McMarui, Fans (shareholders), Mount barrow investment limited and many others (Walker et al, 2004).

The management has tried so much with fruitful efforts to focus the team towards the perspective of making money while winning trophies. The club from its early stages was rescued when it was almost collapsing in 1902, by J.H. Davies who was a local brewer. He contributed heavily towards the development of the Old Trafford ground, which later after completion became one of the leading stadiums in the North England, hosting cup finals and Semi-finals of the Football Association (Szymanski, 1998, pp 47-54).

Manchester United has for many years become a team of expensive players, which have for the years played attractive football hence attracting more fans. This history has made the club to be one of the most sought out club in the recent history.

The brand image of the club which incorporates a range of activities, services and products has contributed to the clubs growth; this is so since consumers most of the times make choices based on the image. The club has strategized successfully by marketing the club beyond their local supporters hence has created massive support both nationally and internationally, this has helped them to convert more fans to customers (Szymanski, 1998, pp 47-54).

One of the shareholders Louis Edwards bought many shares of the club in 1964 when the club was undergoing financial turmoil. Later his son became the Chief Executive of the club in 1981 and tried to lift the club financially. After the sucking of the then manager of the club Atkinson, Ferguson took over in 1986 after which the club started realizing increase in income. This was realized from the commercial activities such as conferences held at club’s facilities.

The club currently has the idea of developing the value of its media rights (Szymanski, 1998, p53). The club has also incorporated some commercial plans by allowing their fans to be treated as customers. This they have achieved through the targeted key markets by providing membership to the fans. The club has resorted to working with the right partners and hence has restructured the rule of sponsorship.

The link that the club has with financial institutions like Bank of Scotland and Zurich Financial services helps in the marketing of the products that falls under the Manchester United finance brand. Also its link with the sports giants Nike in a £300m deal for all the footwear, apparel, equipment and other merchandise bearing the Manchester United’s trademark has created a big boost for the club (Walker et al, 2004).

Compare Manchester United’s resources and capabilities to those of Liverpool. What does your analysis imply for Manchester United’s potential to establish cost and differentiation advantage over Liverpool?

Resources and capabilities in a business entity are often considered to be the primary sources of profitability. The resources are tangible, intangible or human in nature, the tangible resources include; financial, land, buildings, plant and equipments, intangible include; technology, reputation and culture while human resources include; skills, capacity for communication and collaboration, motivation (Szymanski, 1998, pp 47-54).

The resources and capabilities are very vital in a business entity. For instance the tangible resources show the value of fixed assets of a business, the Debt/Equity ratio, credit rating and Net cash flow of the business. The intangible resources indicate the income and expenditure of the firm, brand equity and loyalty of the staff. While human resource helps in determining the employee credentials, pay rates and turnover (Szymanski, 1998, pp 47-54).

Manchester United has been listed as the biggest financially stable football club, generating revenue of £ 172 million and operating profit of £ 58.3 million in the year 2004 while earnings per share was 7.4 pence. Manchester has also emerged as one of the top performing team in the European league due to the quality players it has nurtured as a club, and also its financial ability to acquire star players.

This has been boosted by the fact that top players go for clubs that have got the financial ability to pay attractive salaries (Grant & Peck, 2008, pp 77-86).

In the year 2003/2004 Manchester United was ranked as the club that generated highest revenue standing at £ 259 million as compared with Liverpool’s revenue of £ 140 which was ranked ninth. Also the wages/revenues ratios of Manchester United appeared lower than that of most clubs including Liverpool; this made Manchester to be one of the clubs with the lowest wage bill.

The wage cost for 2005/2006 stood at Manchester United 85 million while Liverpool at 69 million (Grant & Peck, 2008, pp 77-86). Manchester United recorded an increased net profit in the year 2007/2008 to EUR 41 million followed by Liverpool which recorded an average of EUR 20 million (Waltersdorf, 2007).

Table 1: Competitive Analysis, Manchester United Vs Liverpool (Walker et al, 2004).

The above analysis clearly shows that better league performance is what makes a club to obtain higher revenue. The comparison also indicates that higher wage expenditure improves performance.

What threats to continue success does Manchester United’s face?