Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Writing the Research Paper

Writing in a formal, academic, and technical manner can prove a difficult transition for clinicians turned researchers; however, there are several ways to improve your professional writing skills. This chapter should be considered a collection of tools to consider as you work to articulate and disseminate your research.

Chapter 7: Learning Objectives

This is it! You’re ready to tell the world of the work you’ve done. As you prepare to write your research paper, you’ll be able to

- Discuss the most general components of a research paper

- Articulate the importance of framing your work for the reader using a template based on the research approach

- Identify the major components of a manuscript describing original research

- Identify the major components of a manuscript describing quality improvement projects

- Contrast the specifications of guidelines and protocols

- Identify the major components of a narrative review

Guiding Principles

Although it is wise to identify a potential journal or like avenue as you begin to write up you research, this is not always feasible. For this reason, it is a good idea to have an adequate understanding of the general expectations of what is required of written research articles and manuscripts. Here are some things to keep in mind:

Consider the articles you read

As you begin to research potential research interests, pay close attention to the style of writing found in peer-reviewed and academic journals. You will notice that the ‘tone’ of ‘voice’ is often formal and rarely uses the first-person narrative. You will be expected to develop writing of this caliber in order to be published in a reputable peer-reviewed forum. One of the most difficult concepts for novice researchers to understand is that professional or technical writing is very different from casual or conversational writing. There is little room for anecdotes, opinions, or overly descriptive narratives. Keep your writing succinct and focused.

Keep it simple, silly! (KISS)

Recall when you were first introduced to writing a paper in an early English Composition course. It is likely that you were told that the key components of a paper are the introduction, body, and conclusion. This is truly the foundational structure of any good paper. Consider the following outline for your writing assignments:

Introduction

- Brief overview of the topic which identifies the gap of understanding about a particular topic that you hope to address (why is it important?)

- Statement of problem (what issue are you going to address?)

- Purpose statement/thesis statement (what is the objective of this paper?)

Typically the body of the paper will be broken down into themes or elements outlined in the introduction. Occasionally rather than themes or topics to be addressed, the ‘body’ of the paper will have specific components such as a literature review, methodology, data analysis, discussion, and/or recommendation section. Each of these sections may have specific requirements within that section. Later in this chapter, you will be introduced to specific requirements of different types of research papers.

The body of any paper is the ‘meat and potatoes’ of the work. That is, this is the section wherein you both present and explain your ideas in support of the purpose of the paper (described in the introduction). The body of your paper, regardless of specific structure, is where the majority of your evidentiary base should be included. That is, many of the statements you make in these sections will require substantiation from outside resources. It is vital to include appropriate citations of all references used. To save yourself time, cite and reference correctly as you write. Doing so will help ensure that you stay organized as your work evolves.

Sections such as methods or data analyses, will not require as much substantiation and should be considered very ‘cut and dry’. That is, there will be little to no discussion or interpretation of the evidence here. Results sections, similarly, should be focused on the presentation of results specific to your investigation, including statistical analyses. When reporting results of your work consider the format and whether it makes sense to summarize results in a table, figure, or appendix. The appropriate method will depend on both the type and amount of information that you are trying to convey.

The discussion section is the point at which you should frame your results in the context of your interpretation of the existing literature and how your work addresses the gap in knowledge. You’ll work to substantiate your interpretation by utilizing references to present evidence to support your rational. Pay close attention to your approach as you discuss your results and the impact of your work. Be careful not to make declarative statements if your data does not support a cause-and-effect relationship. Additionally, be careful not to draw inference as a result of bias. That is, use caution in skewing the evidence to support your hypothesis.

The conclusion is exactly that. This is your opportunity to wrap your thoughts up succinctly. A good conclusion will remind the reader of the point or focus of the paper, reiterate the arguments outlined in the body as well as summarize any discussion or recommendations posed in those respective sections, and articulate what the content of the paper added to the knowledge base of the subject. This is not a time to introduce new arguments, concepts, or evidence. The reader should be able to finish the paper understanding the purpose of the paper, the main arguments, and the impact of the work on the subject.

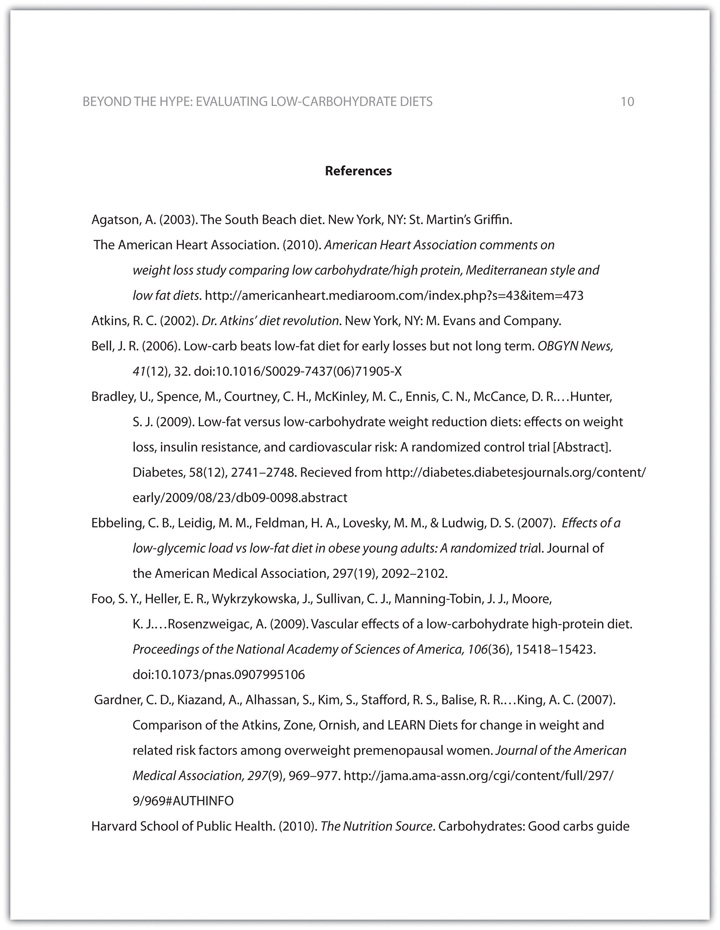

References should be cited correctly in text as well as appropriately formatted at the end of each body of work. The format of your references will depend on the guidelines required of the intended journal or forum you’re submitting to. For example, papers written utilizing the American Psychological Association (APA) formatting standards will include reference pages which are organized on a separate page, titled ‘References’, and organized alphabetically by author surname. If you’re not quite sure of where you’ll be submitting your paper for publication, it may be best to write using APA format; because the references are listed in ascending alphabetical order, adding or removing references during the revision process will be minimally impactful on the designation of subsequent references. Altering your references can then be done once you identify a method of dissemination and review specific guidelines.

Understanding how to present your work can be difficult. It’s one thing to plan and do the research; it’s quite another to put it down on paper in a logical and articulate way. As we discussed in chapters 1 and 2, planning is essential to the success of your research. Similarly, planning the layout of your manuscript will help ensure that you stay both organized and focused. Although most articles can be generalized as having an introduction, body, and conclusion; the specific components within each of those sections varies depending on the approach to research.

Original Research

Although many journals may outline specific requirements for how your manuscript or research paper is to be formatted, there are some generally acceptable formats. One of the most generalizable formats is referred to as IMRaD. IMRaD is an acronym and includes the following elements:

- Introduction- 25%

- Methods- 25%

- Results- 35%

- Discussion/conclusion- 15%

- Clearly state the focus for the work. Provide a brief overview of the issue and the gap in knowledge identified; including both a problem and purpose statement in the context of what is currently understood about the topic. This is where you ‘reel’ the reader in and also highlight the important themes which are consistently addressed in the existing literature.

- General and specific approaches

- Participant selection/randomization

- Instrumentation/measurements utilized

- Here is where you report specific findings and outcomes of your work. There should be very little discussion in this section. Rather, you should present your results and comment, briefly, on how this may relate to the existing literature and state the bottom line. That is, what do these findings suggest. These succinct comments should frame the lens of the discussion section.

- In the discussion section you can further elaborate on your interpretation, based in the evidence, of how your findings relate to what other researchers have found. You can discuss flaws in your work as well as suggestions for direction of future research. You should address each of the main points you presented in your introduction section(s).

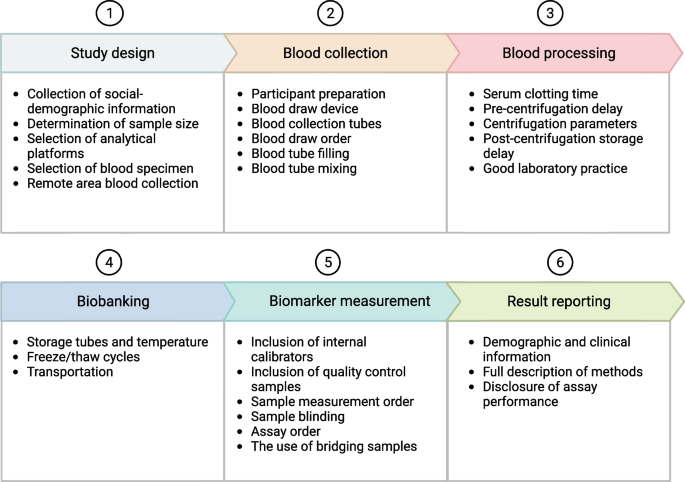

QI Projects

When presenting your QI project; a systematic reporting tool, such as the SQUIRE method , is helpful to ensure that you appropriately present the information in a way that both adds to the understanding of the problem as well as a descriptive approach to solving the issue.

SQUIRE Method

Titling your QI project

- Your title should indicate that the project addresses a specific initiative to improve healthcare.

Example of QI Project title

Quality Improvement Initiative to Standardize High Flow Nasal Cannula for Bronchiolitis: Decreases Hospital and Intensive Care Stay

- Addresses specific initiative to improve healthcare

- Directly identifies the bounds and focus of the project

- Provide enough information to help with searching and indexing of your work

- Summarize all key findings in the format required by the publication. Typical sections include background (including statement of the problem), methods, intervention, results, and conclusion

- Include a description on the nature and significance of the problem

- Summary of what is currently understood about the problem

- Overview of framework, model, concepts and/or theory used to explain the problem. Include an assumptions, delimitations, or definitions used to both describe the problem as well as develop the intervention and why the intervention was intended to work.

- Describe the purpose of the project

- Describe the contextual elements relevant to both the problem and intervention (e.g. environmental factors contributing to the problem)

- Include team-based approach, if applicable

- Describe the approach used to assess the impact of the intervention as well as what approach was used to evaluate/assess the intervention

- What tools did you use to study both the process and intervention and why?

- What tools are in place for ongoing assessment of efficacy of the project?

- How is completeness and accuracy of the data measured?

- Describe the quantitative/qualitative methods used to draw inference from the data collected

- Describe how ethical considerations were addressed and whether the project was overseen by an Institutional Review Board (IRB)

- Initial steps of intervention and evolution over time; including modifications to the intervention or project

- Details of the process measures and outcome

- Key findings including relevance to the rational and specific aims

- Strengths of the projects

- Nature of the association between intervention and outcome

- Comparison of the findings with those of other publications

- Impact of the project

- Reasons for differences between observed and anticipated outcomes; include contextual rationale

- Costs and strategic implications

- Limits to the generalizability of the work

- Factors that may have limited internal validity (e.g. confounding variables, bias, design)

- Efforts made to minimize or adjust for limitations

- Usefulness of the work

- Sustainability

- Potential for application to other contexts

- Implications for practice and further study

- Suggested next steps

- This section would be included if you received funding for the projects.

Narrative Reviews

As mentioned in chapter 2, development of either guidelines or protocols is an intensive process which often requires a systematic team approach to ensure that the scope and purpose of the work is as generalizable as possible. The best approach for the development of guidelines can be found by reviewing the World Health Organization handbook for guideline development .

Presenting a narrative review of a topic is an excellent way to contribute to the knowledge base on a particular subject as well as to provide framework for development of a protocol or guideline. The elements included in presentation of a narrative review are not all that different from those of traditional research studies; however, there are some notable differences. Here is a brief outline of what should be included in a quality narrative review, adapted from Green, Johnson, and Adams (2006) and Ferarri (2015):

- Objective: State the purpose of the paper

- Background: Describe why the paper is being written; include problem statement and/or research question

- Methods: Include methods used to conduct the review; including those used to evaluate articles for inclusion into your work

- Discussion: Frame the findings of the review in the context of the problem

- Conclusion: State what new information your work contributes as a result of your review and synthesis

- Key words: List MeSH terms and words that may help organize and/or locate your work

- Clearly state the focus for the work. Provide a brief overview of the issue and the gap in knowledge identified; including both a problem and purpose statement

- Provide an overview of how information related to the review was located. This includes what terms were searched and where as well as why studies were included in your review. Delimiting your search is important to describe the scope of the review

- Themes or constructs should be identified throughout the review of the literature and arranged in a way such that the discussion of the theme and the link to the evidence should directly address the purpose of your inquiry

- What sets a review apart from an annotated bibliography is synthesis of the evidence around major points identified consistently throughout the research (i.e. themes). Both consensus and diverging approaches should be included in the discussion of the evidence. This should not be considered simply a comparison of the existing evidence, but should be framed through the lens of the author’s interpretation of that evidence.

- Tie back to the purpose as well as the major conclusions identified in the review. No new information should be discussed here, apart from suggestions for future research opportunities

An extremely important part of disseminating your work is ensuring that you have correctly attributed thoughts and content that you did not create. Depending on the nature of your research, discipline, or intended publication, the format by which you list your references or outline resources utilized may differ. Regardless of referencing formatting guidelines, it is imperative to keep your references organized as you draft different iterations of your work. For example, it may be easier to draft your work utilizing American Psychological Association (APA) formatting guidelines, which arrange references by author’s last name, in ascending alphabetical order, than in other formats which require that references be numbered in order of appearance in the text. As you add, delete, or rearrange references within the text of your manuscript, it may be both difficult and time consuming to constantly re-number each of your references. Note : Depending on the reference guidelines for your intended journal, you may be required to list the abbreviated names of journals. Finding this information can be difficult. Consider this resource for locating and identifying how best to list journal titles within a reference.

Key Takeaways

- Identifying an appropriate outline for the research approach you selected is essential to developing a publishable manuscript

- Academic writing is formal in both voice and tone

- Academic writing is technical

- Refrain from the use of the first person narratives, including anecdotes, or interjecting your unsubstantiated opinion

- All research papers have an introduction, body, and conclusion

- Specific components of the introduction and body will vary depending on the approach

- Proper citation, referencing, or attributing must be included in all work

Green, B.N., Johnson, C.D., & Adams, A. (2006). Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 3 (5), 101-117.

Ferrari, R. (2015). Writing narrative style literature reviews. The European Medical Writers Association, 2 4(4), 230-235. doi: 10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329

SQUIRE. (2017). Explanation and elaboration of SQUIRE 2.0 guidelines . SQUIRE. http://www.squire-statement.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=Page.ViewPage&pageId=504

World Health Organization. (2020). WHO handbook for guideline development, 2nd Ed . World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/145714

Practical Research: A Basic Guide to Planning, Doing, and Writing Copyright © by megankoster. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications . If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Yale J Biol Med

- v.84(3); 2011 Sep

Focus: Education — Career Advice

How to write your first research paper.

Writing a research manuscript is an intimidating process for many novice writers in the sciences. One of the stumbling blocks is the beginning of the process and creating the first draft. This paper presents guidelines on how to initiate the writing process and draft each section of a research manuscript. The paper discusses seven rules that allow the writer to prepare a well-structured and comprehensive manuscript for a publication submission. In addition, the author lists different strategies for successful revision. Each of those strategies represents a step in the revision process and should help the writer improve the quality of the manuscript. The paper could be considered a brief manual for publication.

It is late at night. You have been struggling with your project for a year. You generated an enormous amount of interesting data. Your pipette feels like an extension of your hand, and running western blots has become part of your daily routine, similar to brushing your teeth. Your colleagues think you are ready to write a paper, and your lab mates tease you about your “slow” writing progress. Yet days pass, and you cannot force yourself to sit down to write. You have not written anything for a while (lab reports do not count), and you feel you have lost your stamina. How does the writing process work? How can you fit your writing into a daily schedule packed with experiments? What section should you start with? What distinguishes a good research paper from a bad one? How should you revise your paper? These and many other questions buzz in your head and keep you stressed. As a result, you procrastinate. In this paper, I will discuss the issues related to the writing process of a scientific paper. Specifically, I will focus on the best approaches to start a scientific paper, tips for writing each section, and the best revision strategies.

1. Schedule your writing time in Outlook

Whether you have written 100 papers or you are struggling with your first, starting the process is the most difficult part unless you have a rigid writing schedule. Writing is hard. It is a very difficult process of intense concentration and brain work. As stated in Hayes’ framework for the study of writing: “It is a generative activity requiring motivation, and it is an intellectual activity requiring cognitive processes and memory” [ 1 ]. In his book How to Write a Lot: A Practical Guide to Productive Academic Writing , Paul Silvia says that for some, “it’s easier to embalm the dead than to write an article about it” [ 2 ]. Just as with any type of hard work, you will not succeed unless you practice regularly. If you have not done physical exercises for a year, only regular workouts can get you into good shape again. The same kind of regular exercises, or I call them “writing sessions,” are required to be a productive author. Choose from 1- to 2-hour blocks in your daily work schedule and consider them as non-cancellable appointments. When figuring out which blocks of time will be set for writing, you should select the time that works best for this type of work. For many people, mornings are more productive. One Yale University graduate student spent a semester writing from 8 a.m. to 9 a.m. when her lab was empty. At the end of the semester, she was amazed at how much she accomplished without even interrupting her regular lab hours. In addition, doing the hardest task first thing in the morning contributes to the sense of accomplishment during the rest of the day. This positive feeling spills over into our work and life and has a very positive effect on our overall attitude.

Rule 1: Create regular time blocks for writing as appointments in your calendar and keep these appointments.

2. start with an outline.

Now that you have scheduled time, you need to decide how to start writing. The best strategy is to start with an outline. This will not be an outline that you are used to, with Roman numerals for each section and neat parallel listing of topic sentences and supporting points. This outline will be similar to a template for your paper. Initially, the outline will form a structure for your paper; it will help generate ideas and formulate hypotheses. Following the advice of George M. Whitesides, “. . . start with a blank piece of paper, and write down, in any order, all important ideas that occur to you concerning the paper” [ 3 ]. Use Table 1 as a starting point for your outline. Include your visuals (figures, tables, formulas, equations, and algorithms), and list your findings. These will constitute the first level of your outline, which will eventually expand as you elaborate.

The next stage is to add context and structure. Here you will group all your ideas into sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion/Conclusion ( Table 2 ). This step will help add coherence to your work and sift your ideas.

Now that you have expanded your outline, you are ready for the next step: discussing the ideas for your paper with your colleagues and mentor. Many universities have a writing center where graduate students can schedule individual consultations and receive assistance with their paper drafts. Getting feedback during early stages of your draft can save a lot of time. Talking through ideas allows people to conceptualize and organize thoughts to find their direction without wasting time on unnecessary writing. Outlining is the most effective way of communicating your ideas and exchanging thoughts. Moreover, it is also the best stage to decide to which publication you will submit the paper. Many people come up with three choices and discuss them with their mentors and colleagues. Having a list of journal priorities can help you quickly resubmit your paper if your paper is rejected.

Rule 2: Create a detailed outline and discuss it with your mentor and peers.

3. continue with drafts.

After you get enough feedback and decide on the journal you will submit to, the process of real writing begins. Copy your outline into a separate file and expand on each of the points, adding data and elaborating on the details. When you create the first draft, do not succumb to the temptation of editing. Do not slow down to choose a better word or better phrase; do not halt to improve your sentence structure. Pour your ideas into the paper and leave revision and editing for later. As Paul Silvia explains, “Revising while you generate text is like drinking decaffeinated coffee in the early morning: noble idea, wrong time” [ 2 ].

Many students complain that they are not productive writers because they experience writer’s block. Staring at an empty screen is frustrating, but your screen is not really empty: You have a template of your article, and all you need to do is fill in the blanks. Indeed, writer’s block is a logical fallacy for a scientist ― it is just an excuse to procrastinate. When scientists start writing a research paper, they already have their files with data, lab notes with materials and experimental designs, some visuals, and tables with results. All they need to do is scrutinize these pieces and put them together into a comprehensive paper.

3.1. Starting with Materials and Methods

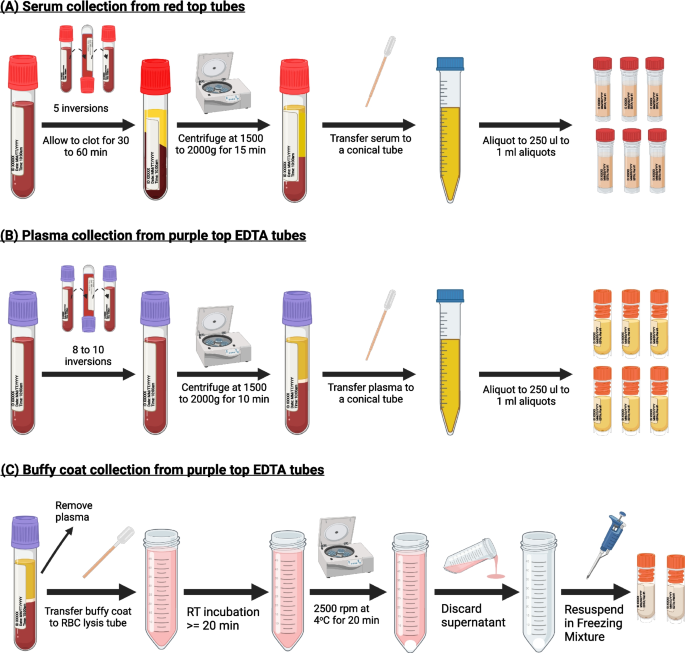

If you still struggle with starting a paper, then write the Materials and Methods section first. Since you have all your notes, it should not be problematic for you to describe the experimental design and procedures. Your most important goal in this section is to be as explicit as possible by providing enough detail and references. In the end, the purpose of this section is to allow other researchers to evaluate and repeat your work. So do not run into the same problems as the writers of the sentences in (1):

1a. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation. 1b. To isolate T cells, lymph nodes were collected.

As you can see, crucial pieces of information are missing: the speed of centrifuging your bacteria, the time, and the temperature in (1a); the source of lymph nodes for collection in (b). The sentences can be improved when information is added, as in (2a) and (2b), respectfully:

2a. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation at 3000g for 15 min at 25°C. 2b. To isolate T cells, mediastinal and mesenteric lymph nodes from Balb/c mice were collected at day 7 after immunization with ovabumin.

If your method has previously been published and is well-known, then you should provide only the literature reference, as in (3a). If your method is unpublished, then you need to make sure you provide all essential details, as in (3b).

3a. Stem cells were isolated, according to Johnson [23]. 3b. Stem cells were isolated using biotinylated carbon nanotubes coated with anti-CD34 antibodies.

Furthermore, cohesion and fluency are crucial in this section. One of the malpractices resulting in disrupted fluency is switching from passive voice to active and vice versa within the same paragraph, as shown in (4). This switching misleads and distracts the reader.

4. Behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 were programmed by using E-Prime. We took ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods). The preferred and unpreferred status of the music was operationalized along a continuum of pleasantness [ 4 ].

The problem with (4) is that the reader has to switch from the point of view of the experiment (passive voice) to the point of view of the experimenter (active voice). This switch causes confusion about the performer of the actions in the first and the third sentences. To improve the coherence and fluency of the paragraph above, you should be consistent in choosing the point of view: first person “we” or passive voice [ 5 ]. Let’s consider two revised examples in (5).

5a. We programmed behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 by using E-Prime. We took ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods) as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music. We operationalized the preferred and unpreferred status of the music along a continuum of pleasantness. 5b. Behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 were programmed by using E-Prime. Ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal were taken as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods). The preferred and unpreferred status of the music was operationalized along a continuum of pleasantness.

If you choose the point of view of the experimenter, then you may end up with repetitive “we did this” sentences. For many readers, paragraphs with sentences all beginning with “we” may also sound disruptive. So if you choose active sentences, you need to keep the number of “we” subjects to a minimum and vary the beginnings of the sentences [ 6 ].

Interestingly, recent studies have reported that the Materials and Methods section is the only section in research papers in which passive voice predominantly overrides the use of the active voice [ 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. For example, Martínez shows a significant drop in active voice use in the Methods sections based on the corpus of 1 million words of experimental full text research articles in the biological sciences [ 7 ]. According to the author, the active voice patterned with “we” is used only as a tool to reveal personal responsibility for the procedural decisions in designing and performing experimental work. This means that while all other sections of the research paper use active voice, passive voice is still the most predominant in Materials and Methods sections.

Writing Materials and Methods sections is a meticulous and time consuming task requiring extreme accuracy and clarity. This is why when you complete your draft, you should ask for as much feedback from your colleagues as possible. Numerous readers of this section will help you identify the missing links and improve the technical style of this section.

Rule 3: Be meticulous and accurate in describing the Materials and Methods. Do not change the point of view within one paragraph.

3.2. writing results section.

For many authors, writing the Results section is more intimidating than writing the Materials and Methods section . If people are interested in your paper, they are interested in your results. That is why it is vital to use all your writing skills to objectively present your key findings in an orderly and logical sequence using illustrative materials and text.

Your Results should be organized into different segments or subsections where each one presents the purpose of the experiment, your experimental approach, data including text and visuals (tables, figures, schematics, algorithms, and formulas), and data commentary. For most journals, your data commentary will include a meaningful summary of the data presented in the visuals and an explanation of the most significant findings. This data presentation should not repeat the data in the visuals, but rather highlight the most important points. In the “standard” research paper approach, your Results section should exclude data interpretation, leaving it for the Discussion section. However, interpretations gradually and secretly creep into research papers: “Reducing the data, generalizing from the data, and highlighting scientific cases are all highly interpretive processes. It should be clear by now that we do not let the data speak for themselves in research reports; in summarizing our results, we interpret them for the reader” [ 10 ]. As a result, many journals including the Journal of Experimental Medicine and the Journal of Clinical Investigation use joint Results/Discussion sections, where results are immediately followed by interpretations.

Another important aspect of this section is to create a comprehensive and supported argument or a well-researched case. This means that you should be selective in presenting data and choose only those experimental details that are essential for your reader to understand your findings. You might have conducted an experiment 20 times and collected numerous records, but this does not mean that you should present all those records in your paper. You need to distinguish your results from your data and be able to discard excessive experimental details that could distract and confuse the reader. However, creating a picture or an argument should not be confused with data manipulation or falsification, which is a willful distortion of data and results. If some of your findings contradict your ideas, you have to mention this and find a plausible explanation for the contradiction.

In addition, your text should not include irrelevant and peripheral information, including overview sentences, as in (6).

6. To show our results, we first introduce all components of experimental system and then describe the outcome of infections.

Indeed, wordiness convolutes your sentences and conceals your ideas from readers. One common source of wordiness is unnecessary intensifiers. Adverbial intensifiers such as “clearly,” “essential,” “quite,” “basically,” “rather,” “fairly,” “really,” and “virtually” not only add verbosity to your sentences, but also lower your results’ credibility. They appeal to the reader’s emotions but lower objectivity, as in the common examples in (7):

7a. Table 3 clearly shows that … 7b. It is obvious from figure 4 that …

Another source of wordiness is nominalizations, i.e., nouns derived from verbs and adjectives paired with weak verbs including “be,” “have,” “do,” “make,” “cause,” “provide,” and “get” and constructions such as “there is/are.”

8a. We tested the hypothesis that there is a disruption of membrane asymmetry. 8b. In this paper we provide an argument that stem cells repopulate injured organs.

In the sentences above, the abstract nominalizations “disruption” and “argument” do not contribute to the clarity of the sentences, but rather clutter them with useless vocabulary that distracts from the meaning. To improve your sentences, avoid unnecessary nominalizations and change passive verbs and constructions into active and direct sentences.

9a. We tested the hypothesis that the membrane asymmetry is disrupted. 9b. In this paper we argue that stem cells repopulate injured organs.

Your Results section is the heart of your paper, representing a year or more of your daily research. So lead your reader through your story by writing direct, concise, and clear sentences.

Rule 4: Be clear, concise, and objective in describing your Results.

3.3. now it is time for your introduction.

Now that you are almost half through drafting your research paper, it is time to update your outline. While describing your Methods and Results, many of you diverged from the original outline and re-focused your ideas. So before you move on to create your Introduction, re-read your Methods and Results sections and change your outline to match your research focus. The updated outline will help you review the general picture of your paper, the topic, the main idea, and the purpose, which are all important for writing your introduction.

The best way to structure your introduction is to follow the three-move approach shown in Table 3 .

Adapted from Swales and Feak [ 11 ].

The moves and information from your outline can help to create your Introduction efficiently and without missing steps. These moves are traffic signs that lead the reader through the road of your ideas. Each move plays an important role in your paper and should be presented with deep thought and care. When you establish the territory, you place your research in context and highlight the importance of your research topic. By finding the niche, you outline the scope of your research problem and enter the scientific dialogue. The final move, “occupying the niche,” is where you explain your research in a nutshell and highlight your paper’s significance. The three moves allow your readers to evaluate their interest in your paper and play a significant role in the paper review process, determining your paper reviewers.

Some academic writers assume that the reader “should follow the paper” to find the answers about your methodology and your findings. As a result, many novice writers do not present their experimental approach and the major findings, wrongly believing that the reader will locate the necessary information later while reading the subsequent sections [ 5 ]. However, this “suspense” approach is not appropriate for scientific writing. To interest the reader, scientific authors should be direct and straightforward and present informative one-sentence summaries of the results and the approach.

Another problem is that writers understate the significance of the Introduction. Many new researchers mistakenly think that all their readers understand the importance of the research question and omit this part. However, this assumption is faulty because the purpose of the section is not to evaluate the importance of the research question in general. The goal is to present the importance of your research contribution and your findings. Therefore, you should be explicit and clear in describing the benefit of the paper.

The Introduction should not be long. Indeed, for most journals, this is a very brief section of about 250 to 600 words, but it might be the most difficult section due to its importance.

Rule 5: Interest your reader in the Introduction section by signalling all its elements and stating the novelty of the work.

3.4. discussion of the results.

For many scientists, writing a Discussion section is as scary as starting a paper. Most of the fear comes from the variation in the section. Since every paper has its unique results and findings, the Discussion section differs in its length, shape, and structure. However, some general principles of writing this section still exist. Knowing these rules, or “moves,” can change your attitude about this section and help you create a comprehensive interpretation of your results.

The purpose of the Discussion section is to place your findings in the research context and “to explain the meaning of the findings and why they are important, without appearing arrogant, condescending, or patronizing” [ 11 ]. The structure of the first two moves is almost a mirror reflection of the one in the Introduction. In the Introduction, you zoom in from general to specific and from the background to your research question; in the Discussion section, you zoom out from the summary of your findings to the research context, as shown in Table 4 .

Adapted from Swales and Feak and Hess [ 11 , 12 ].

The biggest challenge for many writers is the opening paragraph of the Discussion section. Following the moves in Table 1 , the best choice is to start with the study’s major findings that provide the answer to the research question in your Introduction. The most common starting phrases are “Our findings demonstrate . . .,” or “In this study, we have shown that . . .,” or “Our results suggest . . .” In some cases, however, reminding the reader about the research question or even providing a brief context and then stating the answer would make more sense. This is important in those cases where the researcher presents a number of findings or where more than one research question was presented. Your summary of the study’s major findings should be followed by your presentation of the importance of these findings. One of the most frequent mistakes of the novice writer is to assume the importance of his findings. Even if the importance is clear to you, it may not be obvious to your reader. Digesting the findings and their importance to your reader is as crucial as stating your research question.

Another useful strategy is to be proactive in the first move by predicting and commenting on the alternative explanations of the results. Addressing potential doubts will save you from painful comments about the wrong interpretation of your results and will present you as a thoughtful and considerate researcher. Moreover, the evaluation of the alternative explanations might help you create a logical step to the next move of the discussion section: the research context.

The goal of the research context move is to show how your findings fit into the general picture of the current research and how you contribute to the existing knowledge on the topic. This is also the place to discuss any discrepancies and unexpected findings that may otherwise distort the general picture of your paper. Moreover, outlining the scope of your research by showing the limitations, weaknesses, and assumptions is essential and adds modesty to your image as a scientist. However, make sure that you do not end your paper with the problems that override your findings. Try to suggest feasible explanations and solutions.

If your submission does not require a separate Conclusion section, then adding another paragraph about the “take-home message” is a must. This should be a general statement reiterating your answer to the research question and adding its scientific implications, practical application, or advice.

Just as in all other sections of your paper, the clear and precise language and concise comprehensive sentences are vital. However, in addition to that, your writing should convey confidence and authority. The easiest way to illustrate your tone is to use the active voice and the first person pronouns. Accompanied by clarity and succinctness, these tools are the best to convince your readers of your point and your ideas.

Rule 6: Present the principles, relationships, and generalizations in a concise and convincing tone.

4. choosing the best working revision strategies.

Now that you have created the first draft, your attitude toward your writing should have improved. Moreover, you should feel more confident that you are able to accomplish your project and submit your paper within a reasonable timeframe. You also have worked out your writing schedule and followed it precisely. Do not stop ― you are only at the midpoint from your destination. Just as the best and most precious diamond is no more than an unattractive stone recognized only by trained professionals, your ideas and your results may go unnoticed if they are not polished and brushed. Despite your attempts to present your ideas in a logical and comprehensive way, first drafts are frequently a mess. Use the advice of Paul Silvia: “Your first drafts should sound like they were hastily translated from Icelandic by a non-native speaker” [ 2 ]. The degree of your success will depend on how you are able to revise and edit your paper.

The revision can be done at the macrostructure and the microstructure levels [ 13 ]. The macrostructure revision includes the revision of the organization, content, and flow. The microstructure level includes individual words, sentence structure, grammar, punctuation, and spelling.

The best way to approach the macrostructure revision is through the outline of the ideas in your paper. The last time you updated your outline was before writing the Introduction and the Discussion. Now that you have the beginning and the conclusion, you can take a bird’s-eye view of the whole paper. The outline will allow you to see if the ideas of your paper are coherently structured, if your results are logically built, and if the discussion is linked to the research question in the Introduction. You will be able to see if something is missing in any of the sections or if you need to rearrange your information to make your point.

The next step is to revise each of the sections starting from the beginning. Ideally, you should limit yourself to working on small sections of about five pages at a time [ 14 ]. After these short sections, your eyes get used to your writing and your efficiency in spotting problems decreases. When reading for content and organization, you should control your urge to edit your paper for sentence structure and grammar and focus only on the flow of your ideas and logic of your presentation. Experienced researchers tend to make almost three times the number of changes to meaning than novice writers [ 15 , 16 ]. Revising is a difficult but useful skill, which academic writers obtain with years of practice.

In contrast to the macrostructure revision, which is a linear process and is done usually through a detailed outline and by sections, microstructure revision is a non-linear process. While the goal of the macrostructure revision is to analyze your ideas and their logic, the goal of the microstructure editing is to scrutinize the form of your ideas: your paragraphs, sentences, and words. You do not need and are not recommended to follow the order of the paper to perform this type of revision. You can start from the end or from different sections. You can even revise by reading sentences backward, sentence by sentence and word by word.

One of the microstructure revision strategies frequently used during writing center consultations is to read the paper aloud [ 17 ]. You may read aloud to yourself, to a tape recorder, or to a colleague or friend. When reading and listening to your paper, you are more likely to notice the places where the fluency is disrupted and where you stumble because of a very long and unclear sentence or a wrong connector.

Another revision strategy is to learn your common errors and to do a targeted search for them [ 13 ]. All writers have a set of problems that are specific to them, i.e., their writing idiosyncrasies. Remembering these problems is as important for an academic writer as remembering your friends’ birthdays. Create a list of these idiosyncrasies and run a search for these problems using your word processor. If your problem is demonstrative pronouns without summary words, then search for “this/these/those” in your text and check if you used the word appropriately. If you have a problem with intensifiers, then search for “really” or “very” and delete them from the text. The same targeted search can be done to eliminate wordiness. Searching for “there is/are” or “and” can help you avoid the bulky sentences.

The final strategy is working with a hard copy and a pencil. Print a double space copy with font size 14 and re-read your paper in several steps. Try reading your paper line by line with the rest of the text covered with a piece of paper. When you are forced to see only a small portion of your writing, you are less likely to get distracted and are more likely to notice problems. You will end up spotting more unnecessary words, wrongly worded phrases, or unparallel constructions.

After you apply all these strategies, you are ready to share your writing with your friends, colleagues, and a writing advisor in the writing center. Get as much feedback as you can, especially from non-specialists in your field. Patiently listen to what others say to you ― you are not expected to defend your writing or explain what you wanted to say. You may decide what you want to change and how after you receive the feedback and sort it in your head. Even though some researchers make the revision an endless process and can hardly stop after a 14th draft; having from five to seven drafts of your paper is a norm in the sciences. If you can’t stop revising, then set a deadline for yourself and stick to it. Deadlines always help.

Rule 7: Revise your paper at the macrostructure and the microstructure level using different strategies and techniques. Receive feedback and revise again.

5. it is time to submit.

It is late at night again. You are still in your lab finishing revisions and getting ready to submit your paper. You feel happy ― you have finally finished a year’s worth of work. You will submit your paper tomorrow, and regardless of the outcome, you know that you can do it. If one journal does not take your paper, you will take advantage of the feedback and resubmit again. You will have a publication, and this is the most important achievement.

What is even more important is that you have your scheduled writing time that you are going to keep for your future publications, for reading and taking notes, for writing grants, and for reviewing papers. You are not going to lose stamina this time, and you will become a productive scientist. But for now, let’s celebrate the end of the paper.

- Hayes JR. In: The Science of Writing: Theories, Methods, Individual Differences, and Applications. Levy CM, Ransdell SE, editors. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1996. A new framework for understanding cognition and affect in writing; pp. 1–28. [ Google Scholar ]

- Silvia PJ. How to Write a Lot. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Whitesides GM. Whitesides’ Group: Writing a Paper. Adv Mater. 2004; 16 (15):1375–1377. [ Google Scholar ]

- Soto D, Funes MJ, Guzmán-García A, Warbrick T, Rotshtein T, Humphreys GW. Pleasant music overcomes the loss of awareness in patients with visual neglect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009; 106 (14):6011–6016. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hofmann AH. Scientific Writing and Communication. Papers, Proposals, and Presentations. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zeiger M. Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers. 2nd edition. San Francisco, CA: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martínez I. Native and non-native writers’ use of first person pronouns in the different sections of biology research articles in English. Journal of Second Language Writing. 2005; 14 (3):174–190. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodman L. The Active Voice In Scientific Articles: Frequency And Discourse Functions. Journal Of Technical Writing And Communication. 1994; 24 (3):309–331. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tarone LE, Dwyer S, Gillette S, Icke V. On the use of the passive in two astrophysics journal papers with extensions to other languages and other fields. English for Specific Purposes. 1998; 17 :113–132. [ Google Scholar ]

- Penrose AM, Katz SB. Writing in the sciences: Exploring conventions of scientific discourse. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Swales JM, Feak CB. Academic Writing for Graduate Students. 2nd edition. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hess DR. How to Write an Effective Discussion. Respiratory Care. 2004; 29 (10):1238–1241. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Belcher WL. Writing Your Journal Article in 12 Weeks: a guide to academic publishing success. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Single PB. Demystifying Dissertation Writing: A Streamlined Process of Choice of Topic to Final Text. Virginia: Stylus Publishing LLC; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Faigley L, Witte SP. Analyzing revision. Composition and Communication. 1981; 32 :400–414. [ Google Scholar ]

- Flower LS, Hayes JR, Carey L, Schriver KS, Stratman J. Detection, diagnosis, and the strategies of revision. College Composition and Communication. 1986; 37 (1):16–55. [ Google Scholar ]

- Young BR. In: A Tutor’s Guide: Helping Writers One to One. Rafoth B, editor. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook Publishers; 2005. Can You Proofread This? pp. 140–158. [ Google Scholar ]

Research Paper Examples

Research paper examples are of great value for students who want to complete their assignments timely and efficiently. If you are a student in the university, your first stop in the quest for research paper examples will be the campus library where you can get to view the research sample papers of lecturers and other professionals in diverse fields plus those of fellow students who preceded you in the campus. Many college departments maintain libraries of previous student work, including large research papers, which current students can examine.

Embark on a journey of academic excellence with iResearchNet, your premier destination for research paper examples that illuminate the path to scholarly success. In the realm of academia, where the pursuit of knowledge is both a challenge and a privilege, the significance of having access to high-quality research paper examples cannot be overstated. These exemplars are not merely papers; they are beacons of insight, guiding students and scholars through the complex maze of academic writing and research methodologies.

At iResearchNet, we understand that the foundation of academic achievement lies in the quality of resources at one’s disposal. This is why we are dedicated to offering a comprehensive collection of research paper examples across a multitude of disciplines. Each example stands as a testament to rigorous research, clear writing, and the deep understanding necessary to advance in one’s academic and professional journey.

Access to superior research paper examples equips learners with the tools to develop their own ideas, arguments, and hypotheses, fostering a cycle of learning and discovery that transcends traditional boundaries. It is with this vision that iResearchNet commits to empowering students and researchers, providing them with the resources to not only meet but exceed the highest standards of academic excellence. Join us on this journey, and let iResearchNet be your guide to unlocking the full potential of your academic endeavors.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code, what is a research paper.

- Anthropology

- Communication

- Criminal Justice

- Criminal Law

- Criminology

- Mental Health

- Political Science

Importance of Research Paper Examples

- Research Paper Writing Services

A Sample Research Paper on Child Abuse

A research paper represents the pinnacle of academic investigation, a scholarly manuscript that encapsulates a detailed study, analysis, or argument based on extensive independent research. It is an embodiment of the researcher’s ability to synthesize a wealth of information, draw insightful conclusions, and contribute novel perspectives to the existing body of knowledge within a specific field. At its core, a research paper strives to push the boundaries of what is known, challenging existing theories and proposing new insights that could potentially reshape the understanding of a particular subject area.

The objective of writing a research paper is manifold, serving both educational and intellectual pursuits. Primarily, it aims to educate the author, providing a rigorous framework through which they engage deeply with a topic, hone their research and analytical skills, and learn the art of academic writing. Beyond personal growth, the research paper serves the broader academic community by contributing to the collective pool of knowledge, offering fresh perspectives, and stimulating further research. It is a medium through which scholars communicate ideas, findings, and theories, thereby fostering an ongoing dialogue that propels the advancement of science, humanities, and other fields of study.

Research papers can be categorized into various types, each with distinct objectives and methodologies. The most common types include:

- Analytical Research Paper: This type focuses on analyzing different viewpoints represented in the scholarly literature or data. The author critically evaluates and interprets the information, aiming to provide a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

- Argumentative or Persuasive Research Paper: Here, the author adopts a stance on a contentious issue and argues in favor of their position. The objective is to persuade the reader through evidence and logic that the author’s viewpoint is valid or preferable.

- Experimental Research Paper: Often used in the sciences, this type documents the process, results, and implications of an experiment conducted by the author. It provides a detailed account of the methodology, data collected, analysis performed, and conclusions drawn.

- Survey Research Paper: This involves collecting data from a set of respondents about their opinions, behaviors, or characteristics. The paper analyzes this data to draw conclusions about the population from which the sample was drawn.

- Comparative Research Paper: This type involves comparing and contrasting different theories, policies, or phenomena. The aim is to highlight similarities and differences, thereby gaining a deeper understanding of the subjects under review.

- Cause and Effect Research Paper: It explores the reasons behind specific actions, events, or conditions and the consequences that follow. The goal is to establish a causal relationship between variables.

- Review Research Paper: This paper synthesizes existing research on a particular topic, offering a comprehensive analysis of the literature to identify trends, gaps, and consensus in the field.

Understanding the nuances and objectives of these various types of research papers is crucial for scholars and students alike, as it guides their approach to conducting and writing up their research. Each type demands a unique set of skills and perspectives, pushing the author to think critically and creatively about their subject matter. As the academic landscape continues to evolve, the research paper remains a fundamental tool for disseminating knowledge, encouraging innovation, and fostering a culture of inquiry and exploration.

Browse Sample Research Papers

iResearchNet prides itself on offering a wide array of research paper examples across various disciplines, meticulously curated to support students, educators, and researchers in their academic endeavors. Each example embodies the hallmarks of scholarly excellence—rigorous research, analytical depth, and clear, precise writing. Below, we explore the diverse range of research paper examples available through iResearchNet, designed to inspire and guide users in their quest for academic achievement.

Anthropology Research Paper Examples

Our anthropology research paper examples delve into the study of humanity, exploring cultural, social, biological, and linguistic variations among human populations. These papers offer insights into human behavior, traditions, and evolution, providing a comprehensive overview of anthropological research methods and theories.

- Archaeology Research Paper

- Forensic Anthropology Research Paper

- Linguistics Research Paper

- Medical Anthropology Research Paper

- Social Problems Research Paper

Art Research Paper Examples

The art research paper examples feature analyses of artistic expressions across different cultures and historical periods. These papers cover a variety of topics, including art history, criticism, and theory, as well as the examination of specific artworks or movements.

- Performing Arts Research Paper

- Music Research Paper

- Architecture Research Paper

- Theater Research Paper

- Visual Arts Research Paper

Cancer Research Paper Examples

Our cancer research paper examples focus on the latest findings in the field of oncology, discussing the biological mechanisms of cancer, advancements in diagnostic techniques, and innovative treatment strategies. These papers aim to contribute to the ongoing battle against cancer by sharing cutting-edge research.

- Breast Cancer Research Paper

- Leukemia Research Paper

- Lung Cancer Research Paper

- Ovarian Cancer Research Paper

- Prostate Cancer Research Paper

Communication Research Paper Examples

These examples explore the complexities of human communication, covering topics such as media studies, interpersonal communication, and public relations. The papers examine how communication processes affect individuals, societies, and cultures.

- Advertising Research Paper

- Journalism Research Paper

- Media Research Paper

- Public Relations Research Paper

- Public Speaking Research Paper

Crime Research Paper Examples

The crime research paper examples provided by iResearchNet investigate various aspects of criminal behavior and the factors contributing to crime. These papers cover a range of topics, from theoretical analyses of criminality to empirical studies on crime prevention strategies.

- Computer Crime Research Paper

- Domestic Violence Research Paper

- Hate Crimes Research Paper

- Organized Crime Research Paper

- White-Collar Crime Research Paper

Criminal Justice Research Paper Examples

Our criminal justice research paper examples delve into the functioning of the criminal justice system, exploring issues related to law enforcement, the judiciary, and corrections. These papers critically examine policies, practices, and reforms within the criminal justice system.

- Capital Punishment Research Paper

- Community Policing Research Paper

- Corporal Punishment Research Paper

- Criminal Investigation Research Paper

- Criminal Justice System Research Paper

- Plea Bargaining Research Paper

- Restorative Justice Research Paper

Criminal Law Research Paper Examples

These examples focus on the legal aspects of criminal behavior, discussing laws, regulations, and case law that govern criminal proceedings. The papers provide an in-depth analysis of criminal law principles, legal defenses, and the implications of legal decisions.

- Actus Reus Research Paper

- Gun Control Research Paper

- Insanity Defense Research Paper

- International Criminal Law Research Paper

- Self-Defense Research Paper

Criminology Research Paper Examples

iResearchNet’s criminology research paper examples study the causes, prevention, and societal impacts of crime. These papers employ various theoretical frameworks to analyze crime trends and propose effective crime reduction strategies.

- Cultural Criminology Research Paper

- Education and Crime Research Paper

- Marxist Criminology Research Paper

- School Crime Research Paper

- Urban Crime Research Paper

Culture Research Paper Examples

The culture research paper examples examine the beliefs, practices, and artifacts that define different societies. These papers explore how culture shapes identities, influences behaviors, and impacts social interactions.

- Advertising and Culture Research Paper

- Material Culture Research Paper

- Popular Culture Research Paper

- Cross-Cultural Studies Research Paper

- Culture Change Research Paper

Economics Research Paper Examples

Our economics research paper examples offer insights into the functioning of economies at both the micro and macro levels. Topics include economic theory, policy analysis, and the examination of economic indicators and trends.

- Budget Research Paper

- Cost-Benefit Analysis Research Paper

- Fiscal Policy Research Paper

- Labor Market Research Paper

Education Research Paper Examples

These examples address a wide range of issues in education, from teaching methods and curriculum design to educational policy and reform. The papers aim to enhance understanding and improve outcomes in educational settings.

- Early Childhood Education Research Paper

- Information Processing Research Paper

- Multicultural Education Research Paper

- Special Education Research Paper

- Standardized Tests Research Paper

Health Research Paper Examples

The health research paper examples focus on public health issues, healthcare systems, and medical interventions. These papers contribute to the discourse on health promotion, disease prevention, and healthcare management.

- AIDS Research Paper

- Alcoholism Research Paper

- Disease Research Paper

- Health Economics Research Paper

- Health Insurance Research Paper

- Nursing Research Paper

History Research Paper Examples

Our history research paper examples cover significant events, figures, and periods, offering critical analyses of historical narratives and their impact on present-day society.

- Adolf Hitler Research Paper

- American Revolution Research Paper

- Ancient Greece Research Paper

- Apartheid Research Paper

- Christopher Columbus Research Paper

- Climate Change Research Paper

- Cold War Research Paper

- Columbian Exchange Research Paper

- Deforestation Research Paper

- Diseases Research Paper

- Earthquakes Research Paper

- Egypt Research Paper

Leadership Research Paper Examples

These examples explore the theories and practices of effective leadership, examining the qualities, behaviors, and strategies that distinguish successful leaders in various contexts.

- Implicit Leadership Theories Research Paper

- Judicial Leadership Research Paper

- Leadership Styles Research Paper

- Police Leadership Research Paper

- Political Leadership Research Paper

- Remote Leadership Research Paper

Mental Health Research Paper Examples

The mental health research paper examples provided by iResearchNet discuss psychological disorders, therapeutic interventions, and mental health advocacy. These papers aim to raise awareness and improve mental health care practices.

- ADHD Research Paper

- Anxiety Research Paper

- Autism Research Paper

- Depression Research Paper

- Eating Disorders Research Paper

- PTSD Research Paper

- Schizophrenia Research Paper

- Stress Research Paper

Political Science Research Paper Examples

Our political science research paper examples analyze political systems, behaviors, and ideologies. Topics include governance, policy analysis, and the study of political movements and institutions.

- American Government Research Paper

- Civil War Research Paper

- Communism Research Paper

- Democracy Research Paper